Abstract

The ultrasonographic examination is currently increasingly used in imaging peripheral nerves, serving to supplement the physical examination, electromyography and magnetic resonance imaging. As in the case of other USG imaging studies, the examination of peripheral nerves is non-invasive and well-tolerated by patients. The typical ultrasonographic picture of peripheral nerves as well as the examination technique have been discussed in part I of this article series, following the example of the median nerve. Part II of the series presented the normal anatomy and the technique for examining the peripheral nerves of the upper limb. This part of the article series focuses on the anatomy and technique for examining twelve normal peripheral nerves of the lower extremity: the iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves, the lateral cutaneous nerve of the thigh, the pudendal, sciatic, tibial, sural, medial plantar, lateral plantar, common peroneal, deep peroneal and superficial peroneal nerves. It includes diagrams showing the proper positioning of the sonographic probe, plus USG images of the successively discussed nerves and their surrounding structures. The ultrasonographic appearance of the peripheral nerves in the lower limb is identical to the nerves in the upper limb. However, when imaging the lower extremity, convex probes are more often utilized, to capture deeply-seated nerves. The examination technique, similarly to that used in visualizing the nerves of upper extremity, consists of locating the nerve at a characteristic anatomic reference point and tracking it using the “elevator technique”. All 3 parts of the article series should serve as an introduction to a discussion of peripheral nerve pathologies, which will be presented in subsequent issues of the “Journal of Ultrasonography”.

Keywords: peripheral nerves of the lower extremity, ultrasonography, proper anatomy, ultrasonographic anatomy, examination technique

Abstract

Badanie ultrasonograficzne jest obecnie coraz chętniej stosowaną metodą obrazowania nerwów obwodowych, gdyż stanowi doskonałe uzupełnienie badania klinicznego, elektromiografii czy badania metodą rezonansu magnetycznego. Podobnie jak w przypadku innych rodzajów badań ultrasonograficznych, diagnostyka nerwów obwodowych jest nieinwazyjna i dobrze tolerowana przez pacjentów. Charakterystyczny obraz ultrasonograficzny nerwów obwodowych oraz technika badania ultrasonograficznego zostały omówione w pierwszej części pracy na przykładzie nerwu pośrodkowego. W drugiej części przedstawiono anatomię i technikę badania nerwów obwodowych kończyny górnej. W trzeciej zostanie omówiona anatomia i technika badania ultrasonograficznego dwunastu prawidłowych nerwów obwodowych kończyny dolnej: nerwu biodrowo-podbrzusznego, biodrowo-pachwinowego, skórnego bocznego uda, sromowego, kulszowego, piszczelowego, łydkowego, podeszwowego przyśrodkowego, podeszwowego bocznego, strzałkowego wspólnego, strzałkowego głębokiego, strzałkowego powierzchownego. Na załączonych schematach przedstawiono sposoby przyłożenia głowicy, skany z aparatu ultrasonograficznego obrazujące kolejno omawiane nerwy wraz z otaczającymi je strukturami. Obraz ultrasonograficzny nerwów obwodowych w kończynie dolnej jest identyczny jak w kończynie górnej. Częściej niż w kończynie górnej istnieje potrzeba wykorzystania głowic konweksowych, umożliwiających obrazowanie nerwów zlokalizowanych głęboko. Technika badania jest analogiczna jak w kończynie górnej i polega na odnalezieniu nerwu w charakterystycznym punkcie referencyjnym i śledzeniu go „techniką windy”. Niniejsze trzy części artykułu są wstępem do omówienia patologii nerwów obwodowych, która zostanie przedstawiona w kolejnych numerach „Journal of Ultrasonography”.

Introduction

An important break-through in the ultrasound diagnostics of peripheral nerves occurred with the introduction of USG probes with high frequencies (greater than 12–15 MHz). The general examination technique and the ultrasonographic structure of normal peripheral nerves were discussed in the first part of the article. As for the nerves of the lower limb, the subject of this part, the use of convex probes is mentioned, as it allows for the imaging of deeply-localized nerves, as the pudendal nerve or the sciatic nerve upon leaving the piriform muscle, especially in obese persons or those with a well-built muscle mass(1–7).

For the imaging of fine nerves of the lower limb, in the foot similarly to the hand, distancing adaptors may be used. These allow for the repositioning of the ultrasound wave focus to the depth of the studied nerve and to level the surface of contact between the probe and bony irregularities.

The USG image of peripheral nerves in the lower limb is identical to that of the upper limb, except that the phenomenon of anisotropy (a difference in echogenicity related to a change of the incidence angle of the ultrasound cluster) is more often encountered. It is seen in the case of large-diameter nerves, especially the sciatic nerve(2) (fig. 1).

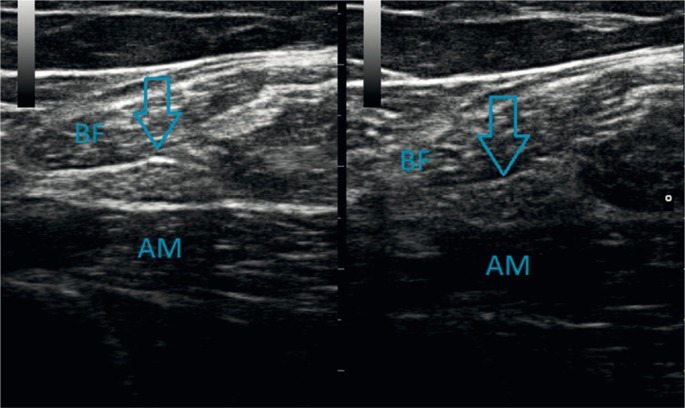

Fig. 1.

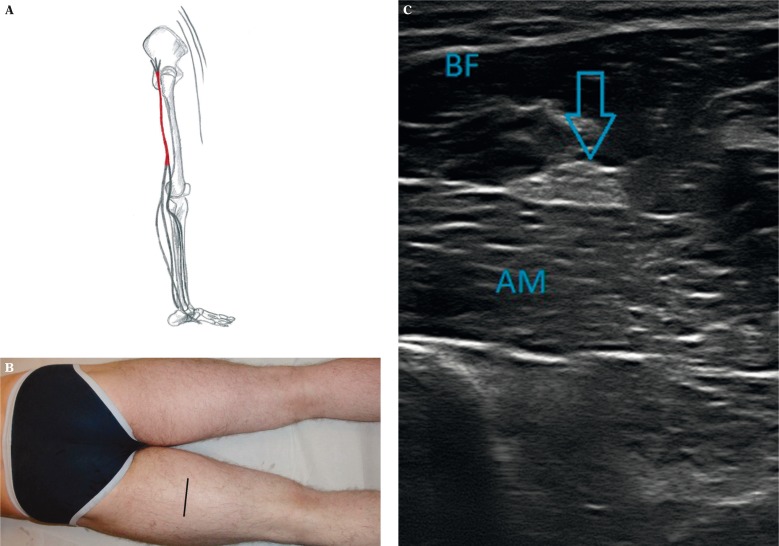

Ainisotropy of the sciatic nerve (arrow): the nerve is both hyperechogenic (left side) and hypoechogenic (right side); the biceps femoris (BF) and adductor magnus (AM) muscles

For the purpose of localizing fine and deep nerves, as in the upper limb, reference anatomical structures, usually arteries accompanying the nerves, are taken advantage of(2, 3). For example, the deep peroneal nerve may be found by locating the anterior tibial artery which follows a similar course (fig. 2).

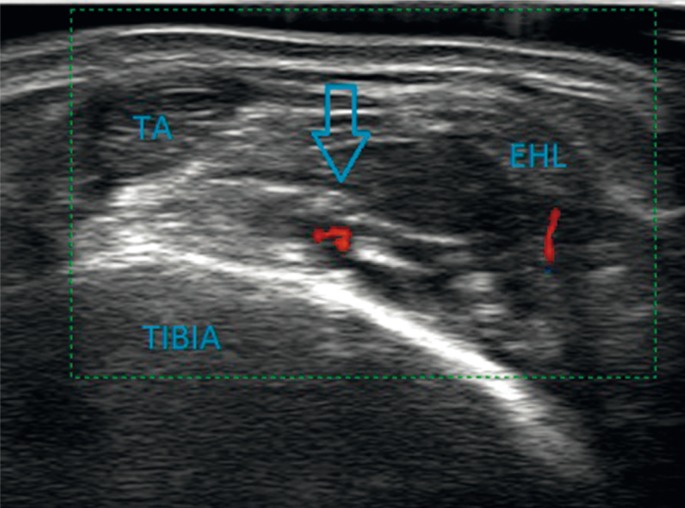

Fig. 2.

Transverse positioning of the probe at the level of the distal end of the lower leg: the anterior tibial nerve (arrow) is seen directly above the anterior tibial artery, the tendon of the tibialis anterior muscle (TA) and the extensor hallucis longus (EHL); tibial bone (Tibia)

In the elderly, it is important to be aware of the additional difficulties in imaging peripheral nerves, due to generalized and progressive atrophic changes in muscle tissue. This complicated both the localization and assessment of nerve trunks and their branches (figs. 3 A, B).

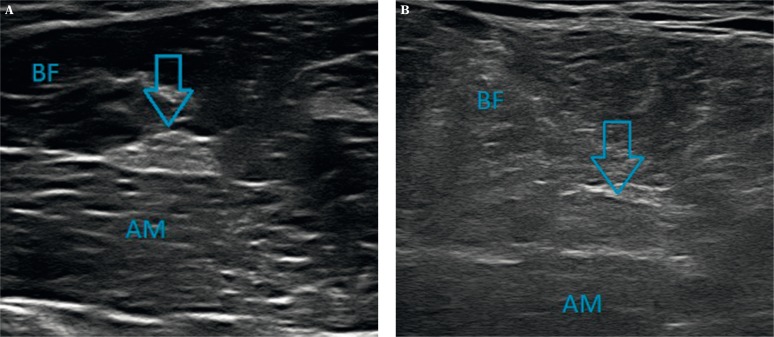

Fig. 3.

A. The hypoechogenic appearance of muscle bellies in a young person, with the fibrillary structure being visible. B. Their hyperechogenic appearance in an elderly person, with blurring of the echostructure; the sciatic nerve (arrow), the biceps femoris (BF) and adductor magnus (AM) muscles

Anatomy and ultrasonographic imaging of selected peripheral nerves of the lower limb

Iliohypogastric nerve (nervus iliohypogastricus)

The iliohypogastric nerve emerges from the lumbar plexus. Its course may be divided into two segments: the more proximal lumbar one and the more distal intermuscular segment. This article only deals with the USG assessment of the latter part, beginning 3–4 cm lateral to the edge of the quadratus lumborum muscle and approximately 2–3 cm above the iliac crest (figs. 4 A, B). From this point, the nerve courses anteriorly between the transversus abdominis and internal oblique muscles, parallel to but above the iliac crest. At the level of the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS), the iliohypogastric nerve pierces the internal oblique muscle. Then, as a terminal branch, it runs along the inguinal ligament, reaching the edge of the rectus abdominis muscle, to pierce the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle above the superficial inguinal ring and finishes its course(2–6, 8–11).

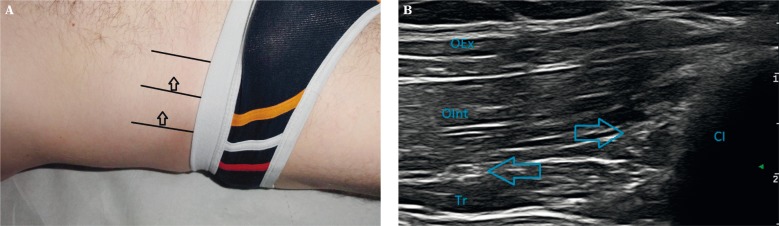

Fig. 4.

A. Application of the probe over the edge of the iliac crest of the ilium, anterior to the quadratus lumborum muscle; direction for moving the probe (arrow). B. The ilioinguinal nerve (rightward arrow), the iliohypogastric nerve (leftward arrow); the iliac crest (CI), the external oblique (OEx) and internal oblique (OInt) abdominal muscles, the transverse abdominis muscle (Tr)

The indications for examining this nerve are rare, yet in spite of its small diameter, it is not difficult to find with USG. The probe should be applied longitudinally, perpendicular to the iliac crest and slightly lateral to the quadratus lumbarum muscle, then moved anteriorly along the nerve's course(2, 3).

Ilioinguinal nerve (nervus ilioinguinalis)

The ilioinguinal nerve is also divided into two: the lumbar and intermuscular parts, and just as with the case of the iliohypogastric nerve, this article will only deal with the intermuscular segment. The ilioinguinal nerve is slightly thinner than the iliohypogastric, and runs parallel to it although approximately 1 cm lower down. It pierces the lateral wall of the abdominal cavity, specifically the transversus abdominis muscle at a variable point. Similarly to the iliohypogastric nerve, the ilioinguinal nerve runs anteromedially in the layer between the transverse abdominal and internal oblique muscles, then between the internal and external oblique muscles, towards the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS), and then along the inguinal ligament. It joins the spermatic cord or the round ligament of the uterus to pass through the superficial inguinal ring, where it gives off sensory end-branches(2–6, 8–11).

The technique of examining this nerve with USG is analogous to the case of the iliohypogastric nerve, described above(2, 3).

Lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (nervus cutaneus femoris lateralis)

The lateral cutaneous nerve of the thigh has a diameter of around 2 mm. It leaves the lesser pelvis medial to the anterior superior iliac spine and reaches the anterior surface of the thigh through the inguinal ligament or slightly inferior to it. Initially it courses between the layers of the fascia lata, which it pierces approximately 2–3 cm below the ASIS, and runs along its surface(2–6, 8–11).

This course of the lateral cutaneous nerve of the thigh is not difficult to follow in the USG examination. The ASIS should be located via palpation. The probe is applied inferior and medial to this point, perpendicular to the long axis of the limb, and then moved distally and slightly laterally to observe the full course of this nerve (figs. 5 A, B)(2, 3).

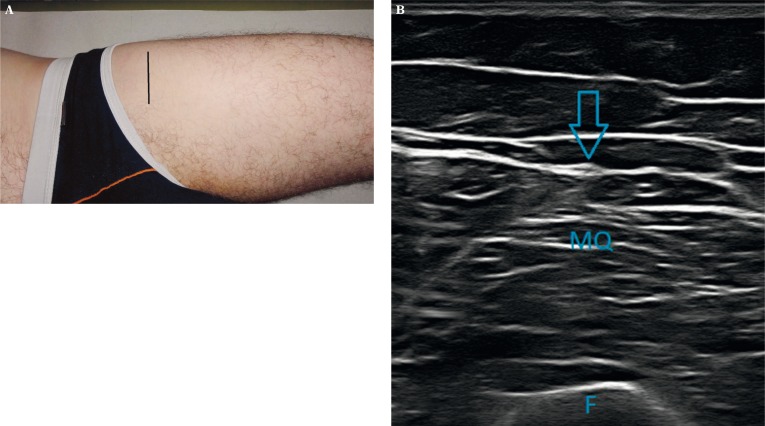

Fig. 5.

A. Application of the probe transversely to the long axis of the limb, below and slightly lateral to the anterior superior iliac spine. B. The lateral cutaneous nerve of the thigh (arrow) on the fascia covering the quadriceps femoris muscle (MQ); the femur (F)

Pudendal nerve (nervus pudendus)

The pudendal nerve has a diameter of around 3 mm. After leaving the lesser pelvis through the greater sciatic foramen between the piriformis and coccygeus muscles, it runs beneath the sacrospinous ligament, and then between this ligament and the sacrotuberous ligament. It is at this segment that the pudendal nerve is most easily identified with USG. Laterally it is accompanied by the internal pudendal artery, whose visualization with Doppler USG helps to identify the nerve. The pudendal nerve reenters the pelvis through the lesser sciatic foramen, adhering to the internal surface of the spine of the ischium(2–6, 8–11).

Due to the nerve's deep position, its USG examination may require the use of a convex probe, particularly in obese patients. The probe is applied in the lower quadrant of the buttocks, perpendicular to the limb's long axis, and moved distally, slightly medially, observing the ischium changing shape from round to flat. At that point, two parallel ligaments (the sagrzbiecrospinous and sacrotuberous ligaments) should be located, along with the pulsating vessel in between them, at whose medial side the pudendal nerve runs (figs. 6 A, B). The sacrospinous ligament is visible as a thin hyperechogenic band laying at the level of and as a continuation of the ischial spine, while the sacrotuberous ligament is found on the anterior surface of the gluteus maximus muscle(2, 3).

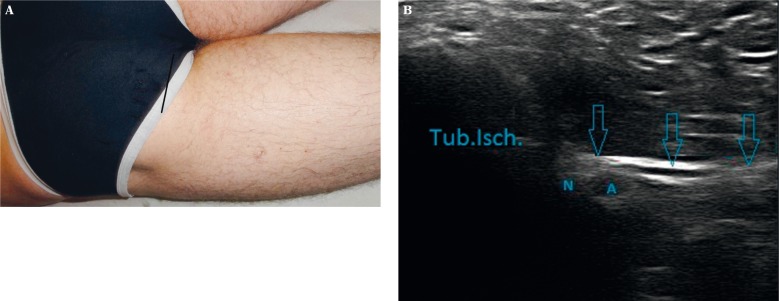

Fig. 6.

A. Application of the probe at the lower part of the buttocks, medial to the ischial tuberosity. B. The pudendal nerve (N) in the vicinity of the pudendal artery (T), below the sacrotuberous ligament, attached to the ischial tuberosity

Sciatic nerve (nervus ischiadicus)

The sciatic nerve is the longest and thickest peripheral nerve (fig. 7 A). It reaches a diameter of up to 2 cm. It leaves the lesser pelvis through the greater sciatic foramen, emerging from beneath the piriformis muscle (in 85% of cases). The sciatic nerve may also pierce this muscle or pass over it. Moreover, there exist anatomical variants of the nerve with high bifurcation points, in which one part runs below the piriformis muscle, while the other through or above the muscle. Below the piriformis muscle, the sciatic nerve towards the dorsal surface of the gemelli muscles, then the obturator internus and quadratus femoris muscles, and beneath the gluteus maximus muscle. The belly of the quadratus femoris muscle separates the nerve from the articular capsule of the hip joint. The inferior gluteal artery accompanies the nerve on its medial side(2, 4–6, 8–11). The sciatic nerve is surrounded by a large amount of connective and adipose tissue. It runs distally along the posterior surface of the adductor magnus muscle (figs. 7 B, C), where it is crossed by the long head of the biceps femoris muscle. Midway down the thigh, it is visible through USG in the groove between the semimembranosus and biceps femoris muscles. The level at which the sciatic nerve divides into the peroneal and tibial nerves varies. Although there are cases of high bifurcation, even within the pelvis, usually it occurs in the distal 1/3 of the thigh, where the hamstring muscles split medially (semimembranosus) and laterally (biceps femoris), forming the superior angle of the popliteal fossa(2, 4, 5).

Fig. 7.

A. Diagram of the sciatic nerve's course. B. Application of the probe perpendicular to the long axis of the thigh, slightly lateral to the midline. C. Transverse cross-section of the nerve (arrow) laying in between the biceps femoris and adductor magnus muscles

The sciatic nerve is easily identified in the USG study, especially at the level of the buttocks, due to the anatomical reference structures, which are easily palpated bony eminences: the greater trochanter of the femur, ischial tuberosity, and posterior superior iliac spine. A study of the nerve may also be begun by applying the probe at 1/3 of the distance between the ischial tuberosity and the greater trochanter of the femur (closer to the spine of the ischium), or midway between the posterior superior iliac spine and the spine of the ischium.

Tibial nerve (nervus tibialis)

The tibial nerve is the thicker terminal branch of the sciatic nerve (fig. 8 A). It runs through the middle of the popliteal fossa, along the dorsal surface of the popliteus muscle, lateral to the venous vessels and medial to the popliteal artery (figs. 8 B, C). At this point it is surrounded by a large amount of connective and adipose tissue, and runs superficially, covered only by the popliteal fascia. In the inferior part of the popliteal fossa, it descends below the merging heads of the gastrocnemius muscle, then below the characteristic arch of the soleus muscle and runs in the layer between it and the FDL, FHL and the TP muscles (figs. 9 A, B). It is accompanied by the posterior tibial artery and vein, initially on its anterior side but more distally more medial. Further in its course, the nerve moves towards the medial malleolar canal, formed from the medial malleolus, the medial aspects of the trochlea tali and calcaneus, and the flexor retinaculum. It passes through the canal along with the tendons of the aforementioned muscles (TP, FDL, FPL) and the posterior tibial artery and vein. The tibial nerve lies posterior to these blood vessels, and anterior to the FHL. Beneath to the retinaculum the nerve divides into end branches: medial plantar and lateral plantar nerves (more below) (2, 4–6, 8–11).

Fig. 8.

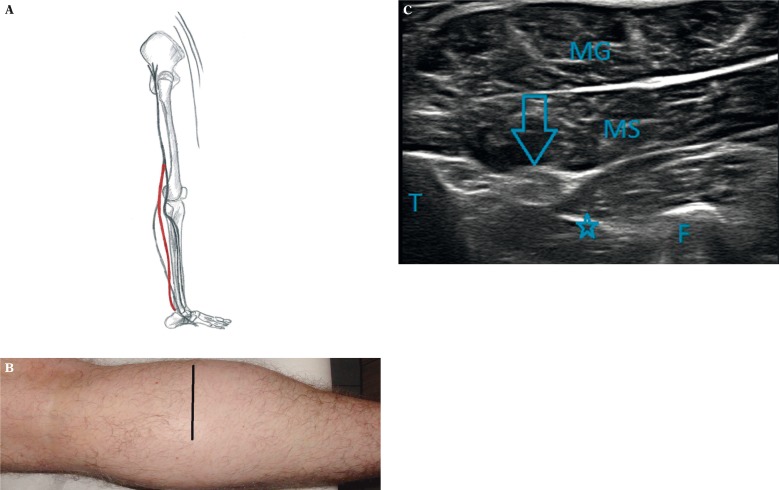

A. Diagram of the course of the tibial nerve. B. Application of the probe transversely to the long axis of the lower leg, slightly medial to the midline. C. The tibial nerve (arrow), the gastrocnemius muscle (MG), the soleus muscle (MS), the tibia (T), fibula (F), and the interosseous membrane (asterisk)

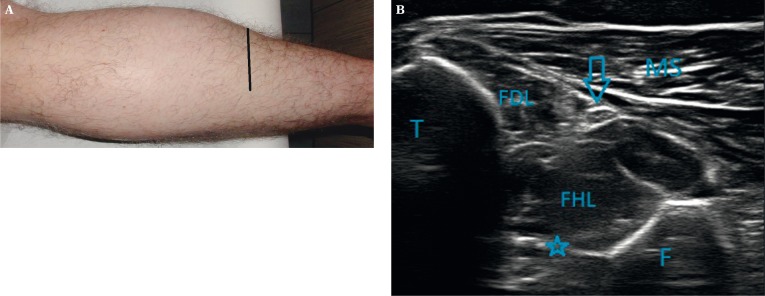

Fig. 9.

A. Application of the probe transverse to the limb's long axis, at the distal end of the lower leg, on its posteromedial aspect. B. The tibial nerve (arrow) running on the belly of the FHL muscle, separated from the tibia (T) by the FDL muscle; the interosseous membrane (asterisk), the fibula (F), the soleus muscle (MS)

Due to its large diameter, linear course and accompanying neurovascular bundle, the tibial nerve is an easy target for an USG assessment. The probe should be applied transversely, slightly medial to the long axis of the fibula, and scan for a large arterial vessel, which serves as the reference point. After identifying the nerve, it can be tracked along its entire length.

Sural nerve (nervus suralis)

Within the popliteal fossa, the tibial nerve gives off the sensory medial sural cutaneous nerve, which runs superficially along the midline between the heads of the gastrocnemius muscle and pierces the fascia around the midpoint of the leg. Medial and more superficial to it runs the lesser saphenous vein. At the distal 1/3 of the leg, the nerve receives a communicating branch from the lateral sural cutaneous nerve and henceforth is called the sural nerve (short saphenous nerve). It then runs on the lateral side of the Achilles tendon, in the direction of the lesser saphenous vein, running between the lateral malleolus and the tuber calcanei, and is continued as the lateral dorsal cutaneous nerve along the lateral side of the foot towards the 5th toe(2, 4–6, 8–11).

Owing to its superficial course, the sural nerve is well-visualized in USG. The study should begin midway down the thigh at the midline, by searching for the nerve in the subcutaneous tissue layer right above the fascia (figs. 9 A, B). In addition, using the probe in a compression test, the nerve may be found by the lumen of the small saphenous vein, which accompanies it from the level of the lateral malleolus(2).

Fig. 10.

A. Transverse application of the probe at the distal 1/3 of the leg in the midline. B. The sural nerve coursing over the fascia of the leg (arrow), in the midline, above the soleus muscle (S), between the heads of the gastrocnemius muscle; the medial (CM) and lateral (CL) heads of the gastrocnemius

Medial plantar nerve (nervus plantaris medialis)

This nerve represents the larger branch of the tibial nerve, running anteriorly along with the medial plantar artery, lateral to the venous vessels. The nerve is visible with USG on the medial surface of the tuber calcanei beneath the abductor hallucis muscle, while from the plantar side it runs between this muscle and the FDB muscle (figs. 11 A, B). At this point it gives off a small branch to the medial side of the great toe, and then at the level of the metatarsal bases it divides into three branches: common plantar digital nerve (digits 1–3), which divide at the metatarsal heads into the proper plantar digital nerves (analogous to the divisions of the median nerve)(2, 4–6, 8–11). Tracking this nerve's initial course with USG is not difficult, given its adequate diameter and its accompanying artery. Problems appear when the nerve passes onto a calloused sole and becomes thinner(2).

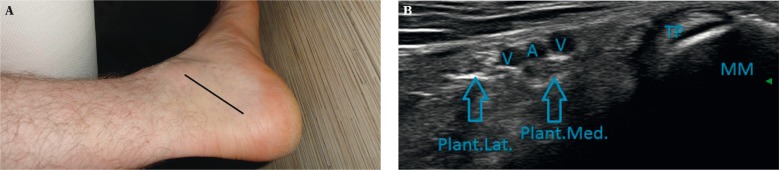

Fig. 11.

A. Application of the probe at the level of the medial malleolar canal. B. The medial malleolar canal with the branches of the tibial nerve – the lateral plantar (Plant.Lat.) and medial plantar (Plant.Med) nerves – both indicated by arrows; the medial malleolus (MM), the tendon of the tibialis posterior muscle (TP), the posterior tibial artery (A) and 2 accompanying veins (V)

Lateral plantar nerve (nervus plantaris lateralis)

The lateral planter nerve is the smaller branch of the tibial nerve, and for this reason is more difficult to visualize in the USG examination, particularly its distal segment(2, 4–6, 8–11) (figs. 11 A, B). It runs obliquely on the lateral surface of the foot, beneath the abductor muscle, along with the artery of the same name at its lateral side. On the plantar surface of the foot, the nerve courses between the quadratus plantae and the FDB muscles, and reaches the lateral border of the foot at the level of the tuberosity of the 5th metatarsal bone. There it divides into superficial and deep branches. Its further divisions into end-branches is identical to the ulnar nerve; the superficial branch gives off, among others, the common digital plantar nerve to the 4th digit.

Common peroneal nerve (nervus fibularis communis)

The common fibular nerve forms at the bifurcation of the tibial nerve at the level of the thigh (fig. 12 A). It is half the diameter of the tibial nerve. Its initial segment descends diagonally along the lateral side of the popliteal fossa, and on the medial side of the biceps femoris muscle. Then it courses in the groove between the tendons of the biceps femoris and the lateral head of the gastrocnemius muscles, until reaching the posterior surface of the head of the fibula. It then wraps around the neck of the fibula to cross to the anterior surface of the leg. Around the peroneus longus muscle, the common fibular nerve splits in two: the superficial fibular nerve and the deep fibular nerve (figs. 12 B, C)(2, 4–6, 8–11).

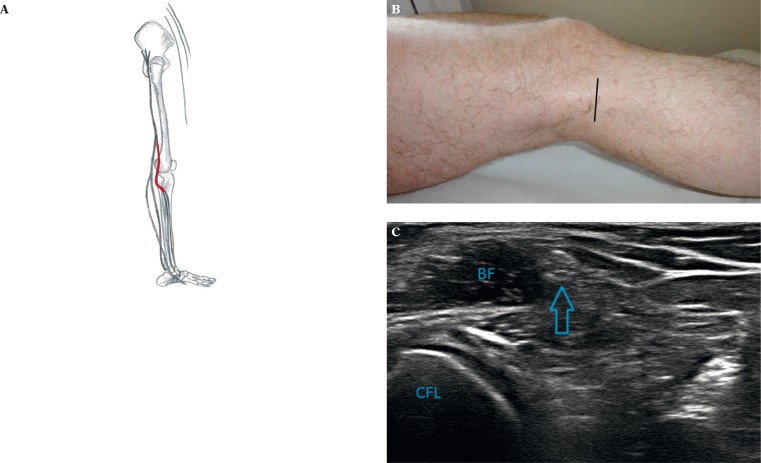

Fig. 12.

A. Diagram of the course of the common fibular nerve. B. Application of the probe on the posterolateral surface of the proximal thigh. C. The common fibular nerve (arrow) at the level of the distal femur, on the left side are visible the outline of the lateral femoral condyle (CFL), next to the biceps femoris (BF) muscle

The USG examination of this relatively short nerve should not be problematic. It can be begun at the level of the sciatic nerve's division and the nerve can be observed by moving the probe along the length of the biceps femoris tendon. Another option is starting at the lateral surface of the neck of the fibula, where the common fibular nerve runs directly along the bone surface, crossing from the posterior onto the anterior surface of the leg(2).

Superficial peroneal nerve (nervus fibularis superficialis)

The superficial fibular nerve begins between two parts of the origin of the peroneus longus muscle. Initially it runs along the surface of the peroneus brevis muscle, underneath the peroneus longus. In the distal part of the leg it goes beneath the fascia of the calf and descends between the peroneus muscles and the EDL (figs. 13 A, B). It pierces the (deep) fascia in the lower 1/3 of the leg and divides into two cutaneous end-branches: the medial and the intermediate dorsal cutaneous nerves. The medial dorsal cutaneous nerve undergoes further divisions, and its branches run towards the medial border of the foot and great toe as well as the dorsal surface of the 2nd and 3rd toes as the dorsal digital branches. Whereas the intermediate dorsal cutaneous nerve gives off the dorsal digital branches to the 3rd, 4th, and 5th toes(2, 4–6, 8–11).

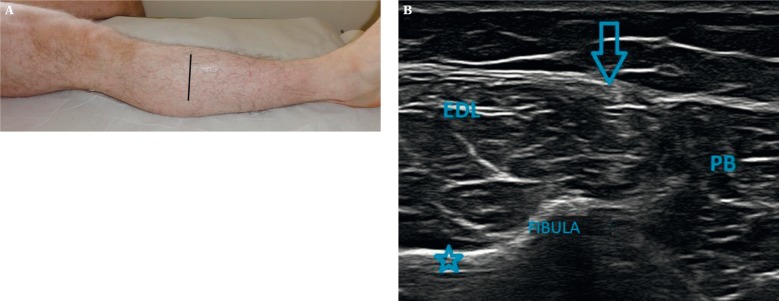

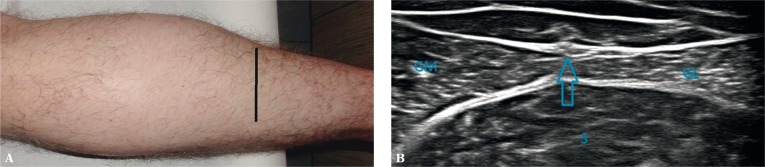

Fig. 13.

A. Positioning of the probe perpendicular to the long axis of the leg, on its anterolateral aspect. B. The superificial peroneal nerve (arrow), the peroneus brevis (PB) and the extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscles; in the background, the contour of the fibula (Fibula) is visible, as well as the interosseous membrane (asterisk)

Tracking the superficial fibular nerve with USG requires particular attention, due to its small diameter, deep location of the initial segment, and changing relationship with respect to neighboring tendons. Distancing adaptors may be used on the dorsal surface of the foot to facilitate the imaging of this nerve and its branches. By tracking the nerve with the “elevator technique”, even the dorsal digital branches may be identified(2).

Deep peroneal nerve/anterior tibial nerve (nervus fibularis profundus/nervus tibialis anterior)

Like the superficial fibular nerve, the deep fibular nerve begins between the bellies of the peroneus longs muscle. Then it courses between this muscle and the bony surface of the fibula, passing through the anterior intermuscular septum into the extensor compartment (figs. 14 A, B). Further on it runs medially to the EDL muscle and in the upper 1/3 of the leg it joins the anterior tibial vessels on the anterior surface of the interosseous membrane. Alongside these vessels, the deep fibular nerve runs between the EDL and TA muscles, and then between the EHL and TA. At the level of the ankle joint (talocrural joint) it passes beneath the extensor retinaculum, crossing behind the tendon of the EHL, and moves onto the dorsum of the foot between the EHL and EDL tendons. Here it passes from the lateral side to the medial side of the dorsalis pedis artery (figs. 15 A–D).

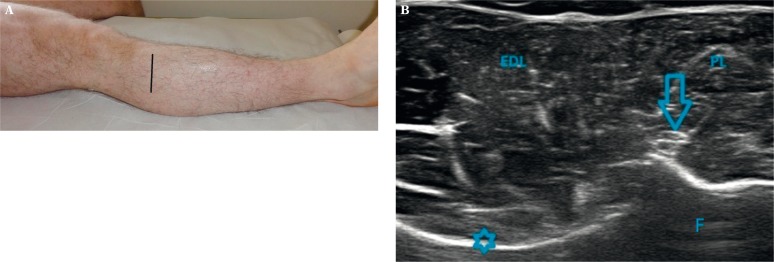

Fig. 14.

A. Application of the probe perpendicular to the long axis of the leg, on the anterolateral surface of the lower leg's distal end. B. The deep peroneal nerve (arrow), the fibula (F), the interosseous membrane (asterisk), the extensor digitorum longus (EDL) and peroneus longus (PL) muscles

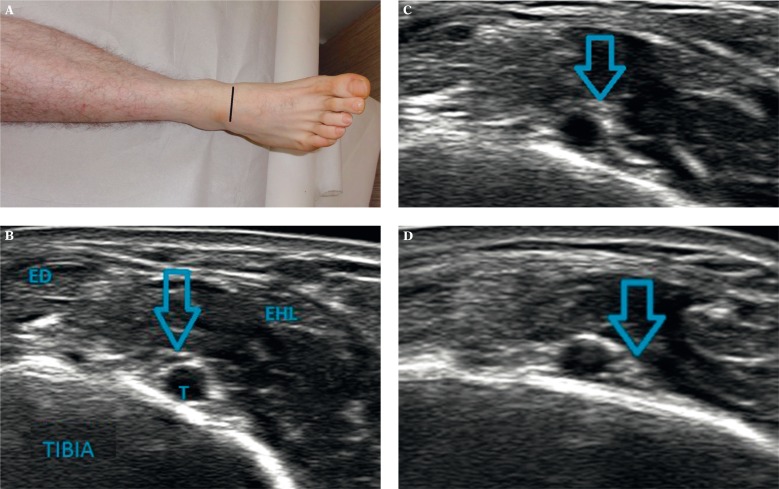

Fig. 15.

A. Transverse application of the probe at the level of the ankle, in the midline. B–D. The changed position of the deep peroneal nerve (arrow) with respect to the anterior tibial artery (T) at the level of the tarsus; the tibia (Tibia), EHL – extensor hallucis longus, ED – extensor digitorum

The nerve divides into two end-branches between the EHL and the EHB. Its lateral terminal branch passes below the EDB, while the medial one runs laterally along the dorsalis pedis artery towards the 1st interosseous space, where it divides into dorsal digital nerves(2, 4–6, 8–11).

The USG examination of this nerve, as the superficial fibular nerve, requires thoroughness due to its small diameter and complex course. Nonetheless, the deep fibular nerve may be tracked from the level of the trunk (it is easiest to start from the level of the common fibular nerve) to the end branches(2).

Summation

An USG examination of peripheral nerves is not routinely performed even by specialized in the USG imaging of the musculoskeletal system. This task requires a detailed knowledge of the normal anatomy and is often time-consuming. A great advantage at the hands of the person performing this study is information about the clinical picture, which allows the correlation of the reported symptoms to a concrete neuropathy. This article, with its two parts presenting the twenty most commonly evaluated peripheral nerves of the extremities, shows how the ultrasound examination is a sensitive diagnostic tool.

In the majority of cases, the image of nerve pathology is straightforward, yet there are situations in which USG is unreliable. The benefits and limitations of this method in the diagnosis of various neuropathies, including traumatic, compression, postoperative, inflammatory and congenital ones, will be discussed by the authors in further articles.

Abbreviations

- ASIS

anterior superior iliac spine

- EDL

extensor digitorum longus

- EHB

extensor hallucis brevis

- EHL

extensor hallucis longus

- FDB

flexor digitorum brevis

- FDL

flexor digitorum longus

- FPL

flexor hallucis longus

- PB

peroneus brevis

- PL

peroneus longus

- TA

tibialis anterior

- TP

tibialis posterior

- USG

ultrasonography

References

- 1.Martinoli C. Imaging of the peripheral nerves. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol. 2010;14:461–462. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1268395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bianchi S, Martinoli C. Ultrasonografia układu mięśniowo-szkieletowego. Vol. 2. Warszawa: Medipage; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peng P, Tumber P. Ultrasound-guided interventional procedures for patients with chronic pelvic pain – a description of techniques and review of literature. Pain Physician. 2008;11:215–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hadzic A, Vloka JD. Zasady i praktyka. Warszawa: Medipage; 2008. Blokady nerwów obwodowych. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marhofer P. Zasady i praktyka. Warszawa: Medipage; 2010. Zastosowanie ultrasonografii w blokadach nerwów obwodowych. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Felten DL, Józefowicz R, Netter FH. Atlas neuroanatomii i neurofizjologii Nettera. Wrocław: Elsevier Urban and Partner; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiou HJ, Chou YH, Chiou SY, Liu JB, Chang CY. Peripheral nerve lesions: role of high-resolution US. RadioGraphics. 2003;23:15. doi: 10.1148/rg.e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schunke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U, Voll M, Wesker K. Prometeusz. Atlas anatomii człowieka. Wrocław: MedPharm; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bochenek A, Reicher M. Anatomia człowieka. Vol. 5. Warszawa: PZWL; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abrahams P, Marks S, Hutchings R. McMinn's Color Atlas of Human Anatomy. London: Mosby; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gray H. Anatomy Descriptive and Applied. London: Longman's, Green and CO; 1935. [Google Scholar]