Abstract

Ultrasound imaging of the musculoskeletal system is superior to other imaging methods in many aspects, such as multidimensional character of imaging, possibility of dynamic evaluation and precise assessment of soft tissues. Moreover, it is a safe and relatively inexpensive method, broadly available and well-tolerated by patients. A correctly conducted ultrasound examination of the wrist delivers detailed information concerning the condition of tendons, muscles, ligaments, nerves and vessels. However, the knowledge of anatomy is crucial to establish a correct ultrasound diagnosis, also in wrist assessment. An ultrasound examination of the wrist is one of the most common US examinations conducted in patients with rheumatological diseases. Ultrasonographic signs depend on the advancement of the disease. The examination is equally frequently conducted in patients with pain or swelling of the wrist due to non-rheumatological causes. The aim of this publication was to present ultrasound images and anatomic schemes corresponding to them. The correct scanning technique of the dorsal part of the wrist was discussed and some practical tips, thanks to which highly diagnostic images can be obtained, were presented. The following anatomical structures should be visualized in an ultrasound examination of the dorsal wrist: distal radio-ulnar joint, radiocarpal joint, midcarpal joint, carpometacarpal joints, dorsal radiocarpal ligament, compartments of extensor tendons, radial artery, cephalic vein, two small branches of the radial nerve: superficial and deep, as well as certain midcarpal ligaments, particularly the scapholunate ligament and lunotriquetral ligament. The paper was distinguished in 2014 as the “poster of the month” (poster number C-1896) during the poster session of the European Congress of Radiology in Vienna.

Keywords: ultrasound, tendons, wrist, peripheral nerves, hand

Abstract

Badanie ultrasonograficzne układu mięśniowo-szkieletowego w wielu aspektach przewyższa inne metody obrazowania, tj. w zakresie wielopłaszczyznowości obrazowania, możliwości oceny dynamicznej, precyzyjnej oceny tkanek miękkich. Ponadto jest metodą bezpieczną, stosunkowo tanią, szeroko dostępną oraz dobrze tolerowaną przez pacjentów. Poprawnie wykonane badanie ultrasonograficzne nadgarstka dostarcza szczegółowych informacji o stanie ścięgien mięśni, więzadeł, nerwów i naczyń. Jednak warunek dobrej diagnozy ultrasonograficznej, w tym nadgarstka, stanowi znajomość anatomii. Badanie USG nadgarstka jest jednym z najczęstszych badań USG wykonywanych w diagnostyce pacjentów z chorobami reumatologicznymi. Objawy ultrasonograficzne zależą od stopnia zaawansowania choroby. Równie często badanie przeprowadza się u pacjentów z bólem lub obrzękiem nadgarstka z przyczyn niereumatologicznych. Celem tej publikacji jest zaprezentowanie obrazów ultrasonograficznych oraz korespondujących z nimi schematów anatomicznych. Omówiono prawidłową technikę badania ultrasonograficznego grzbietowej części nadgarstka wraz z praktycznymi wskazówkami ułatwiającymi uzyskanie wysoce diagnostycznych obrazów. W trakcie badania grzbietowej strony nadgarstka należy uwidocznić nas tępujące struktury anatomiczne: staw promieniowo-łokciowy dalszy, staw promieniowo-nadgarstkowy, staw śródnadgarstkowy, stawy śródręczno-nadgarstkowe, więzadło promieniowo-nadgarstkowe grzbietowe, przedziały ścięgien mięśni prostowników, tętnica promieniowa, żyła odpromieniowa oraz dwie małe gałązki nerwu promieniowego: powierzchowna i głęboka, niektóre więzadła śródnadgarstkowe, zwłaszcza więzadło łódeczkowato-księżycowate oraz więzadło księżycowato-trójgraniaste. Praca została wyróżniona w 2014 roku jako „plakat miesiąca” (numer plakatu C-1896) podczas sesji plakatowej Europejskiego Kongresu Radiologicznego w Wiedniu.

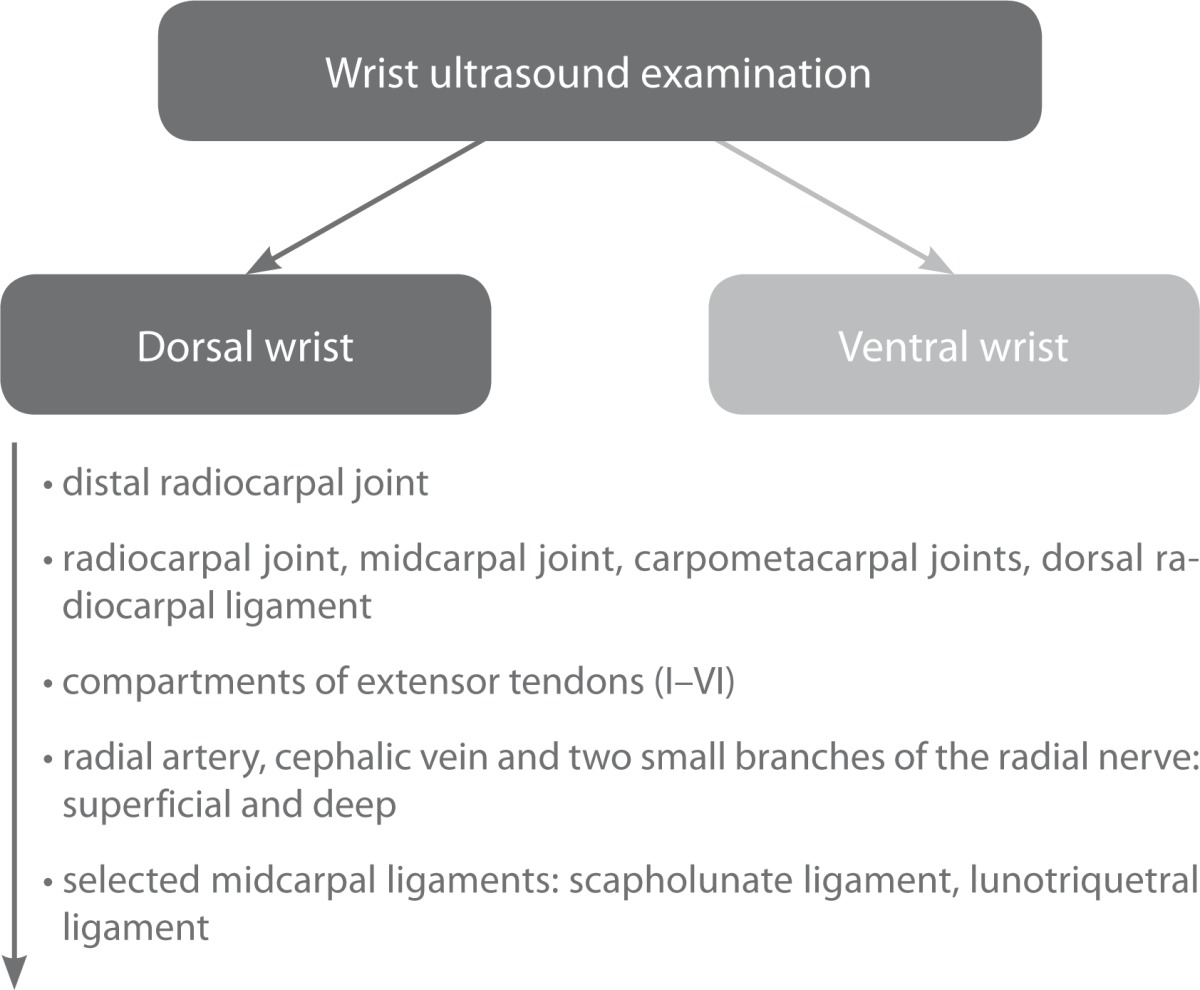

An ultrasound (US) examination of the hand, including the wrist, should be conducted with the use of a linear transducer of a high frequency (>12 MHz). The patient should sit down opposite the examiner with the hand resting on a table or on the patient's knee. The examination involves the evaluation of its dorsal and palmar (ventral) side. The dorsal wrist assessment should include imaging of the following anatomical structures (Tab. 1)(1–5):

distal radioulnar joint;

radiocarpal joint, midcarpal joint, carpometacarpal joints, dorsal radiocarpal ligament;

compartments of extensor tendons;

additionally, the following structures are also visible: radial artery, cephalic vein and two small branches of the radial nerve: superficial and deep;

certain midcarpal ligaments are also visible, in particular the scapholunate ligament and lunotriquetral ligament.

Tab. 1.

Anatomical structures evaluated during ultrasound examination of the dorsal wrist

Tab. 2.

First compartment. Anatomy review

| First compartment | |

|---|---|

| Anatomy review | |

|

EPB – extensor pollicis brevis

Origin: proximal radius and interosseous membrane Insertion: proximal phalanx of the thumb Blood supply: posterior interosseous artery Nerve: posterior interosseous nerve Actions: extension and abduction of thumb at metacarpopharyngeal joint Tips and tricks: Anatomical variant – absence of EPB. Then fusion with tendon of extensor pollicis longus (third compartment) can be observed. |

APL – abductor pollicis longus

Origin: ulna, radius and interosseous membrane Insertion: a) distal, superficial part: radial side of the base of metacarpal bone b) proximal, deep part: variable – trapezium, joint capsule or belly of abductor pollicis brevis Blood supply: posterior interosseous artery Nerve: posterior interosseous nerve Actions: abduction and extension of thumb Tips and tricks: In about 80% of people accessory abductor pollicis longus tendon is present (in some of them even accessory belly of this muscle can be identified). |

Tab. 3.

Second compartment. Anatomy review

| Second compartment | |

|---|---|

| Anatomy review | |

|

ECRL – extensor carpi radialis longus

Origin: lateral supracondylar ridge of humerus Insertion: radial side of the base of 2nd metacarpal Blood supply: radial artery Nerve: radial nerve Actions: extensions of the wrist, abduction of the hand at the wrist Tips and tricks: A very long tendon of ECRL, starting at proximal third of the forearm. |

ECRB – extensor carpi radialis brevis

Origin: lateral epicondyle of the humerus, radial collateral ligament of elbow joint Insertion: base of the 3rd metacarpal Blood supply: radial artery Nerve: deep branch of the radial nerve Actions: extension of the wrist, abduction of the hand at the wrist Tips and tricks: Few fibres can be inserted into middle part of the dorsal surface of the second metacarpal bone. |

Tab. 4.

Third compartment. Anatomy review

| Third compartment |

|---|

| Anatomy review |

|

EPL – extensor pollicis longus

Origin: interosseous membrane, middle third of ulna (posterior surface) Insertion: the base of the distal phalanx of the thumb Blood supply: mostly posterior interosseous artery Nerve: posterior interosseous nerve (deep branch of the radial nerve) Actions: extension of the thumb in metacarpophalangeal and interphalangeal joints Tips and tricks: 1. Easy to identify on transverse view: single tendon on the ulnar side of the Lister tubercle of the radius which is perfect bony landmark. 2. Rupture of the EPL tendon is more commonly associated with undisplaced fractures of the distal radius rather than with displaced fractures. Reason: ischaemic rupture. Rupture usually occurs 3 weeks to 3 months after injury (in less than 3% cases of distal radius fractures). |

Tab. 5.

Fourth Compartment. Anatomy review

| Fourth compartment |

|---|

| Anatomy review |

|

ED – extensor digitorum (extensor digitorum communis and extensor indicis proprius)

Origin: lateral epicondyle of humerus, common extensor tendon Insertion: extensor expansion of middle and distal phalanges of 2nd, 3rd, 4th and 5th fingers Blood supply: posterior interosseous artery Nerve: radial nerve Actions: extension of the phalanges (mainly the proximal phalanges), then the wrist, and finally the elbow. ED tends to separate the fingers as it extends them. Tips and tricks: 1. The middle and terminal phalanges are extended mainly by the interossei and lumbricales. 2. Mallet finger – injury of ED tendon at the distal interpharyngeal joint DIP. Mallet finger usually is caused by an object (e.g., a ball) striking the finger, creating a forceful flexion of the extended DIP. The extensor tendon may be stretched, partially torn, or completely ruptured or separated by a distal phalanx avulsion fracture. |

Tab. 6.

Fifth compartment. Anatomy review

| Fifth compartment |

|---|

| Anatomy review |

|

EDQ – extensor digiti quinti propius (extensor digiti minimi)

Origin: lateral epicondyle of humerus, common extensor tendon Insertion: extensor expansion at the dorsal side of the base of the proximal phalanx of 5th finger Blood supply: posterior interosseous artery Nerve: radial nerve Actions: extension of the wrist and of the little finger (at all joints) Tips and tricks: Anatomy details: common extensor tendon – attaches to the lateral epicondyle of the humerus and serves as the origin for following muscles (some of them partially): 1. Extensor carpi radialis brevis (II) 2. Extensor digitorum (IV) 3. Extensor digiti quinti propius (V) 4. Extensor carpi ulnaris (VI) |

Tab. 7.

Sixth compartment. Anatomy review

| Sixth compartment |

|---|

| Anatomy review |

|

ECU – extensor carpi ulnaris

Origin: lateral epicondyle of humerus, common extensor tendon, ulna Insertion: the base of the 5th metacarpal Blood supply: ulnar artery Nerve: radial nerve Actions: extension of the wrist, slight ulnar flexion of the hand Tips and tricks: Images of this tendon should be obtained in short and in long axis. Follow the tendon towards its insertion at the base of the 5th metacarpal. |

Distal radioulnar joint

The distal radioulnar joint is assessed by positioning the transducer transversely and longitudinally at the level of the radioulnar joint space. The aim of the test is to find signs of inflammation in the joint, such as effusion or synovial pathology.

Radiocarpal joint, midcarpal joint, carpometacarpal joints, dorsal radiocarpal ligament

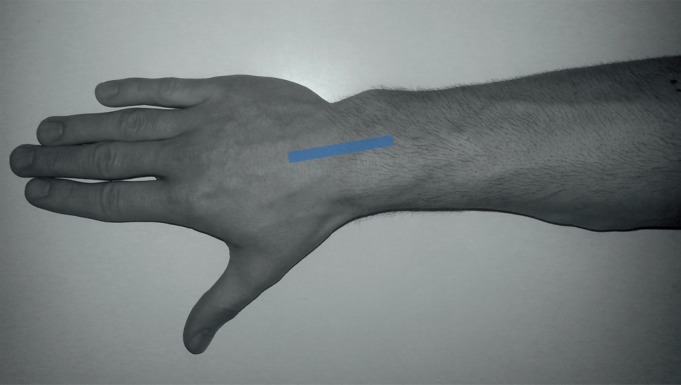

The joint cavity of the radiocarpal joint consists of the carpal surface of the radial bone and the articular disk (that separates the wrist from the distal ulnar bone). The head is composed of three out of four bones of the proximal row of the wrist: scaphoid, lunate and triquetral bones. During the examination, the transducer should be placed longitudinally in the long axis of the limb (Fig. 1; a US image obtained at this localization is presented in Fig. 2). Subsequently, the transducer is moved towards the elbow and radial bone, above the subsequent carpal bones.

Fig. 1.

Probe position to evaluate the radiocarpal and midcarpal joints. Ultrasound image obtained in this position is presented in Fig. 2

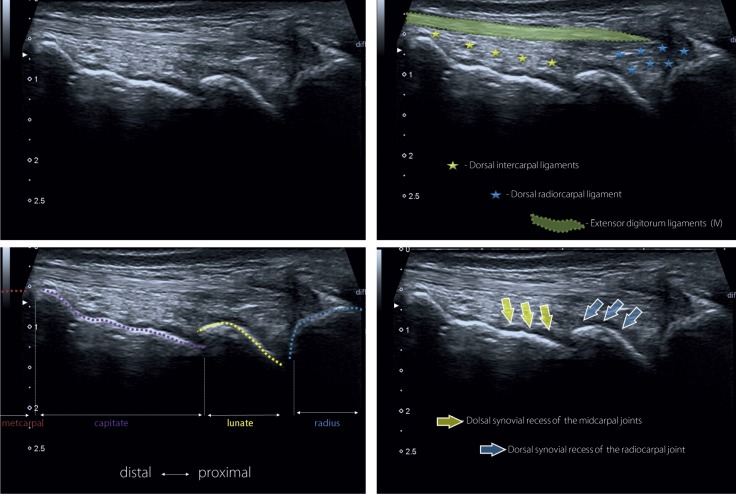

Fig. 2.

Radiocarpal and midcarpal joints (dorsal wrist). The manner of probe position is presented in Fig. 1

The midcarpal joint is composed of the proximal and distal rows of carpal bones. It has an extensive capsule and its shape resembles a horizontal letter “S.” It permits flexion and extension movements of the wrist.

The carpometacarpal joints are localized between the articular surfaces of the distal row bones and articular surfaces of the proximal bases of the metacarpal bones. Apart from the carpometacarpal joint of the first metacarpal bone, the joints are of limited mobility.

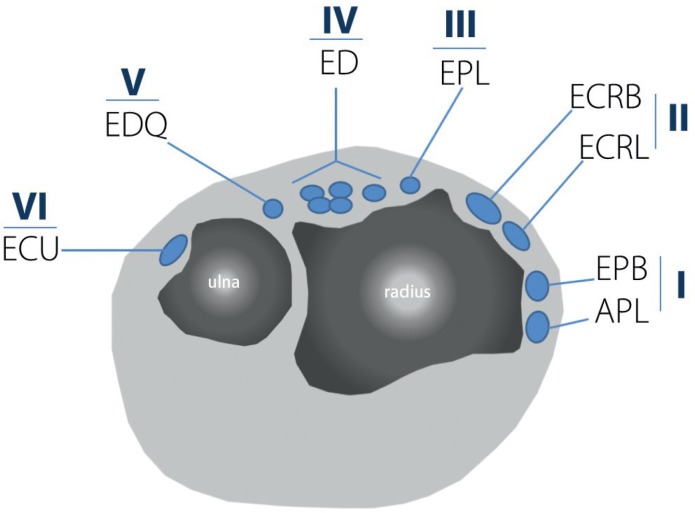

Compartments of extensor tendons

During the examination, one should assess the compartments of extensor tendons, including the content of the sheaths and the condition of the tendons (Fig. 3). Each compartment has its own retinaculum. It is important to visualize and identify individual tendons on the transverse view, and then follow them distally, up to their insertion, and proximally, to observe the structure of the muscle belly.

Fig. 3.

Compartments of extensor tendons: I) abductor pollicis longus tendon, APL; extensor pollicis brevis tendon, EPB; II) extensor carpi radialis longus tendon, ECRL; extensor carpi radialis brevis tendon, ECRB; III) extensor pollicis longus tendon, EPL; IV) extensor digitorum communis tendon, ED; extensor indicis proprius tendon, EPI; V) extensor digiti quinti proprius tendon, EDQ; VI) extensor carpi ulnaris tendon, ECU

First compartment

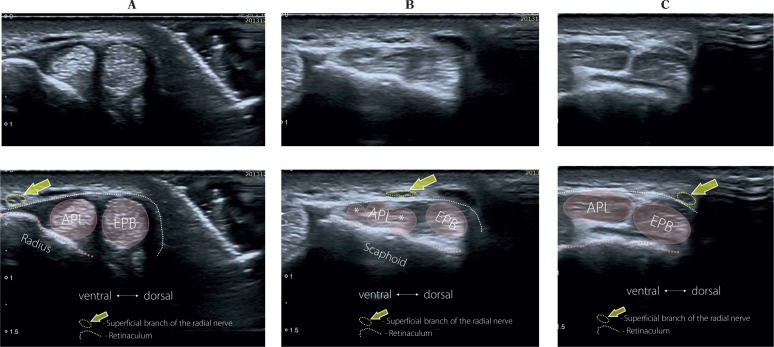

The first compartment of extensor tendons is localized on the radial, dorsal surface of the wrist and includes the tendons of: the abductor pollicis longus (APL) and extensor pollicis brevis (EPB). During its examination, the patient's hand should rest freely or, if a good access cannot be obtained, it should be raised from the radial side. The transducer positions and their corresponding ultrasound images are presented in Fig. 4 and 5.

Fig. 4.

First compartment. Scanning technique. Images obtained in these positions of the probe are shown in Fig. 5

Fig. 5.

First compartment (dorsal wrist). The image shows the abductor pollicis longus (APL) and extensor pollicis brevis tendons (EPB). The superficial branch of the radial nerve (yellow arrow) crosses above the tendons of the APL and EPL as the probe is moved distally

Attention should be paid to the presence of a possible septum between the EBP and APL tendons that divides the compartment into two smaller ones. Its presence predisposes to De Quervain syndrome. Moreover, multiple tendons of the first compartment are also observed quite frequently, which favors compression and irritation.

The factor initiating De Quervain syndrome is overuse of the first compartment tendons that enter into a conflict with the retinaculum due to repetitive movements of the wrist. This initially leads to tenosynovitis of the first compartment tendons and to microinjuries with subsequent inflammatory-repair processes of the retinaculum. It can also cause secondary inflammation of the sheath and even sheath and tendon of the EBP and APL. Fibrosis and thickening of the retinaculum of the first compartment result from the inflammatory-repair reaction. These conditions exacerbate the conflict between the tendons/sheaths and the pulley that move beneath it, and can ultimately lead to the blockage of tendon movement(6).

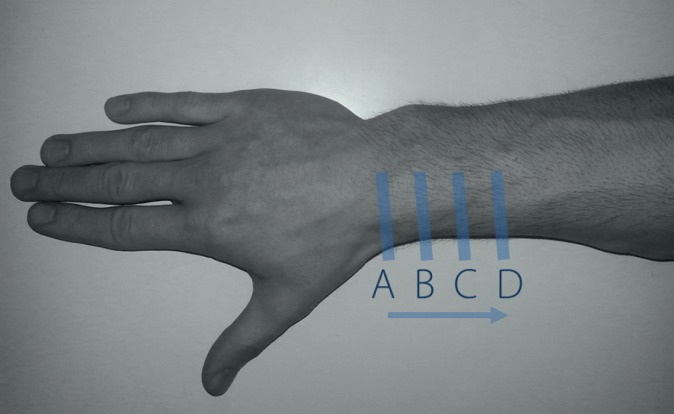

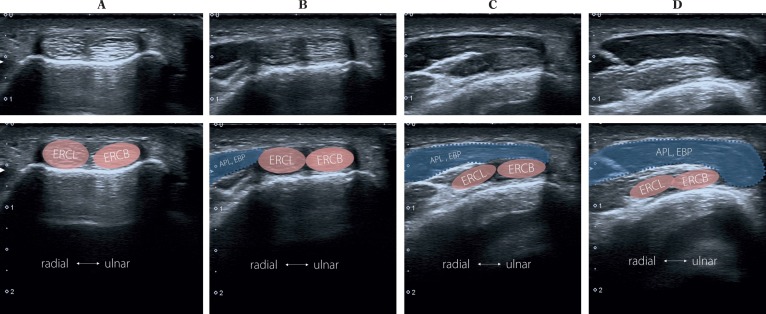

Second compartment

The second compartment of extensor tendons, localized on the ulnar side of the first compartment, includes: the tendon of the extensor carpi radialis longus (ECRL) and extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB). The transducer positions and their corresponding ultrasound images are presented in Fig. 6 and 7. The scanning technique of the second compartment involves detailed assessment of the site in which it intersects with the muscles of the first compartment. It is localized about 4 cm proximally from the dorsal tubercle of the radial bone (Fig. 7). Specific, repetitive wrist movements may lead to a conflict in this localization between the intersecting first and second compartments, and thus bursitis can develop. This is so-called “intersection syndrome” which can develop in canoeists, weight lifters, skiers and people who perform repetitive activity, continuously flexing and extending the wrist during professional work(7).

Fig. 6.

Second compartment. Scanning technique. Images obtained in these positions of the probe are shown in Fig. 7

Fig. 7.

Second compartment. The probe is placed transversally as it is shown in Fig. 6. The tendons of the second compartment can be identified (tendon of extensor carpi radialis longus; ECRL, tendon of extensor carpi radialis brevis, ECRB). As the probe is moved proximally along the tendons of the second compartment (from position A to position D in Fig. 4), the muscles of the first compartment can be seen (abductor pillicis longus, APL; extensor pollicis brevis; EPB). Note how the muscles of the first compartment encroach superficially to the ECRL and ECRB (II)

Bursitis in further stages of an untreated conflict leads to secondary tenosynovitis in both compartments.

In such a situation, a US image of intersection syndrome reveals effusion and thickening of the synovial sheaths. In advanced stages, a US image shows changes within the tendons themselves, i.e. thickening, blurred fibrillar structure or vascularized scars(6). The presence of anechoic zones within the tendons, without increased vascularity in patients with a long history, probably indicates hypocellular scarring(6).

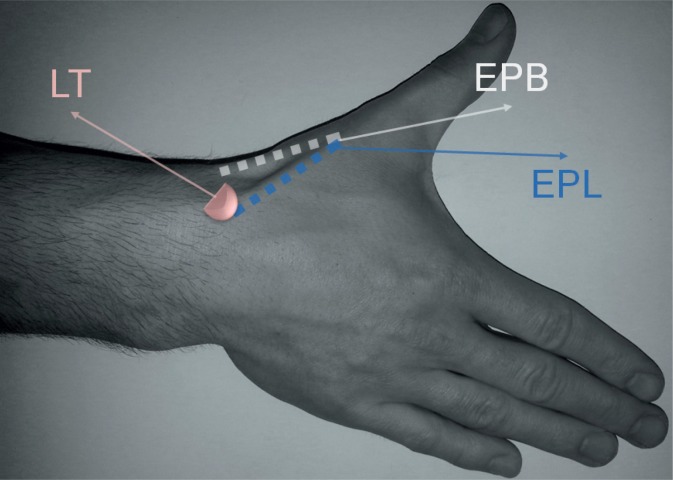

Third compartment

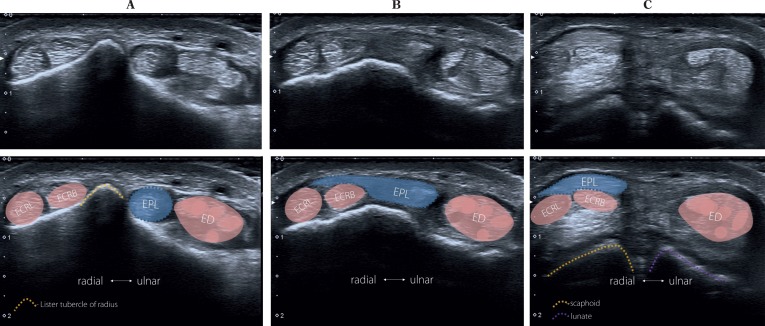

The third compartment of extensor tendons includes the extensor pollicis longus tendon (EPL). When the probe is placed transversally (Fig. 8 A), the EPL tendon is visible on the ulnar side of the dorsal tubercle of the radial bone (Lister tubercle), which serves as a bony landmark due to its simple localization both in a US examination and on palpation (Fig. 10). It separates the extensor tendons of the second and third compartments. The transducer positions and their corresponding ultrasound images are presented in Fig. 8 and 9. Particular attention should be paid to the site in which the EPL crosses with the extensor tendons of the second compartment. In patients with a history of undisplaced distal radius fractures, delayed EPL tendon rupture can occur more frequently than in patients with displaced bone fragments. The phenomenon described is associated with compression on the tendon and its consequent ischemia and friction against bony structures. EPL rupture occurs after several weeks of distal radius fracture(8, 9).

Fig. 8.

Third compartment. Scanning technique. Images obtained in these positions of the probe are shown in Fig. 9

Fig. 10.

Anatomical snuff-box. LT – Lister tubercle, EPL – extensor pollicis longus (compartment III), EPB – extensor pollicis brevis (compartment I)

Fig. 9.

Third compartment (dorsal wrist) with the extensor pollicis longus tendon (EPL). The probe is placed transversally as it is shown in Fig. 8, point A. It is subsequently moved distally up to the EPL insertion. A – the “starting position”: the EPL tendon is situated on the ulnar side of the Lister tubercle. B and C show the EPL tendon encroaching superficially from the tendons of the second compartment (tendon of the extensor carpi radialis longus; ECRL, tendon of the extensor carpi radialis brevis, ECRB) to the tendon of the extensor digitorum communis which belongs to the fourth compartment

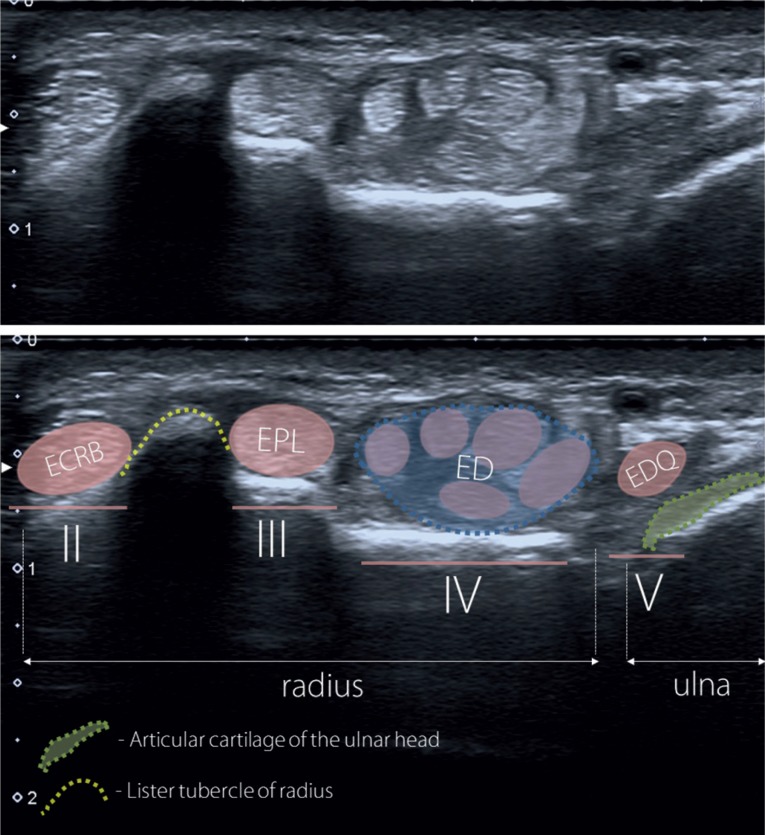

Fourth compartment

The fourth compartment of extensor tendons includes the tendons of extensor digitorum (ED) of the 2nd–5th fingers and the tendon of extensor indicis proprius (EIP). Note that the index finger has two extensor tendons. The fourth compartment includes two tendon sheaths: one that is common for all extensor tendons of the 2nd–5th fingers, and the other for the tendon of the index finger. This compartment contains the greatest number of tendons and therefore its retinaculum is the thickest. In the radial part of this compartment, a deep branch of the radial nerve (posterior interosseous nerve, PIN), together with the posterior interosseous artery, can be seen under the tendons. The place of transducer application and the images are presented in Fig. 11 and 12.

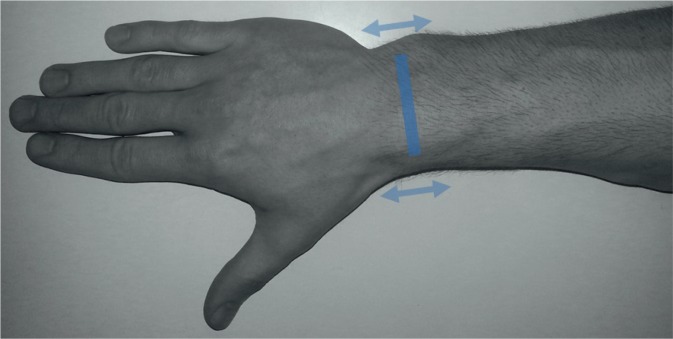

Fig. 11.

Fourth and fifth compartments (dorsal wrist). Scanning technique. Images obtained in these positions of the probe are shown in Fig. 12

Fig. 12.

Fourth and fifth compartments: II) extensor carpi radialis longus tendon, ECRL; extensor carpi radialis brevis tendon, ECRB; III) extensor pollicis longus tendon, EPL; IV) extensor digitorum communis tendon, ED and extensor indicis proprius tendon, EIP; V) extensor digiti quinti proprius tendon, EDQ

Fifth compartment

The fifth compartment includes a small tendon of the extensor digiti quinti proprius (EDQ). It usually quickly divides into two separate tendons. The site of transducer application and the image obtained is presented in Fig. 11 and 12. Finger movements in a dynamic examination allow the extensor tendons of individual fingers to be identified.

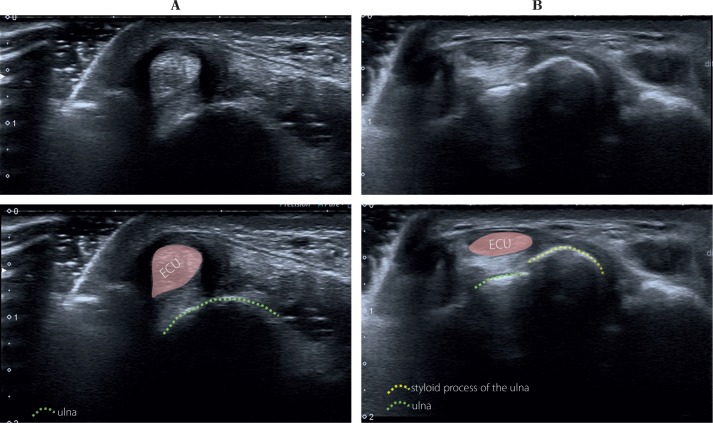

Sixth compartment

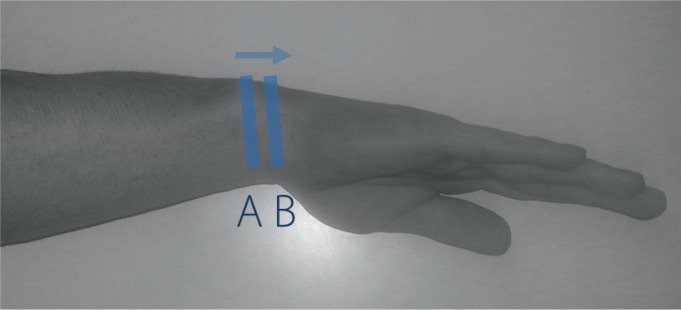

The sixth compartment of extensor tendons includes the extensor carpi ulnaris tendon (ECU). The site of transducer application and the image obtained is presented in Fig. 13 and 14. During the examination, attention should be paid to the osseofibrous ring created by the groove of the ulna and sixth compartment retinaculum (subsheath), which maintain the correct position of the ECU tendon. A dynamic examination upon a change of the hand position enables the visualization of the instability and ECU tendon slipping from its groove as a result of stretching (e.g. in an inflammatory or rheumatic process) or rupture of the retinaculum. This takes place due to repetitive microinjuries or a single trauma during supination or flexion of the ulnar wrist. In this position, the greatest load is placed upon the pulley(10). The greatest number of sixth compartment retinaculum injuries is noted in tennis and golf players(11–13).

Fig. 13.

Sixth compartment (dorsal wrist). Scanning technique. Images obtained in this position of the probe are shown in Fig. 14

Fig. 14.

Sixth compartment (extensor carpi ulnaris tendon, ECU)

Radial nerve, radial artery and cephalic vein

The radial nerve at the level of the lateral epicondyle of the humerus divides into two terminal branches: the superficial branch of the radial nerve and the posterior interosseous nerve (PIN). At the level of the wrist, the deep branch of the radial nerve (PIN) is situated under the tendons of the fourth compartment, and the superficial branch is visible at the level of the anatomical snuff box, above the first compartment of extensor tendons. The radial artery runs together with this branch but under the tendons of the first compartment.

The nerve and appropriate probe placement can be seen in Fig. 4 and 5. In the case of irritation or injury of this nerve, so-called Wartenberg's disease can develop, the symptoms of which include pain, numbness and paresthesia of the distal radial forearm as well as wrist and thumb. In patients with these symptoms, the nerve echostructure must be assessed along its entire length on transverse and longitudinal views, with particular attention paid to edema, rupture or significant changes in adjacent tissues (e.g. thrombosis in the cephalic vein)(6). The identification of the radial nerve branches and vessels is important before each intervention, e.g. decompression of a ganglion cyst arising from the carpal joint or for a precise puncture, without irritating or damaging these structures.

Scapholunate ligament and lunotriquetral Ligament

Internal carpal ligaments, which stabilize the connection between individual bones of the proximal and distal rows, are: scapholunate ligament, lunotriquetral ligament, trapezio-trapezoid ligament (between the trapezium and trapezoid bone), trapezocapitate ligament (between the trapezoid and the capitate bone) and capitohamate ligament (between the hamate and capitate bone). During a standard US examination of the wrist, the scapholunate and lunotriquetral ligaments are assessed(14).

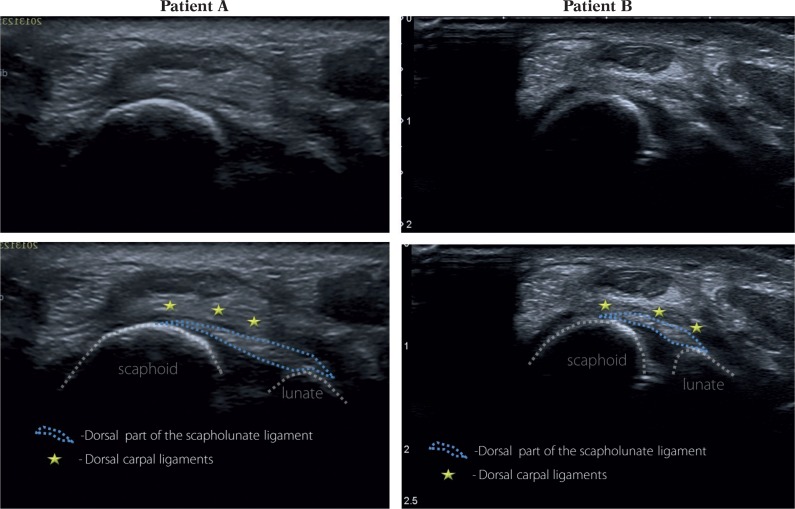

The scapholunate ligament consists of three parts: dorsal (the strongest one) as well as proximal and ventral, which are assessed in MR arthrography. The US examination enables good visualization of the dorsal part of the scapholunate ligament and the ventral part of the lunotriquetral ligament(15).

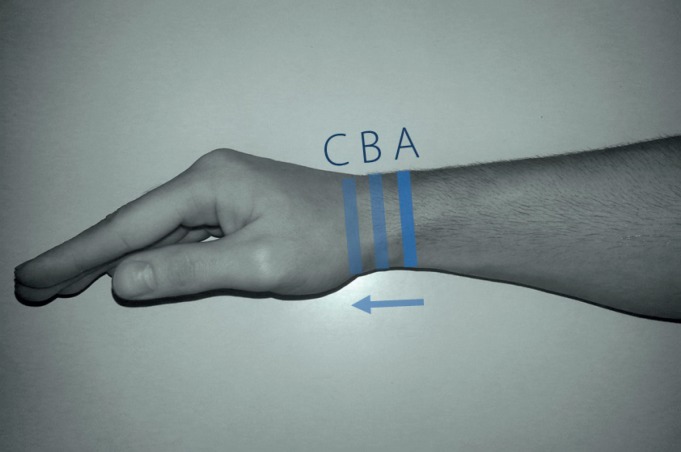

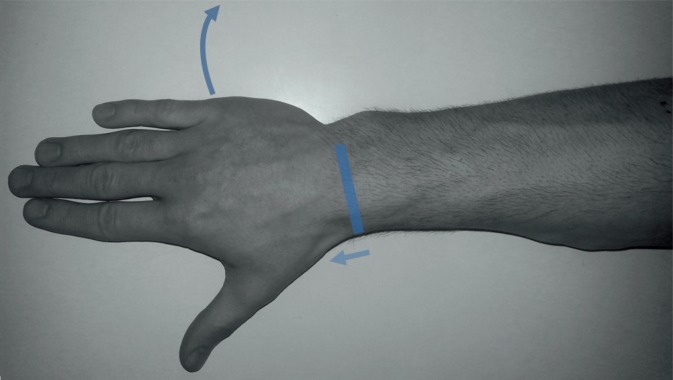

The transducer should be placed transversely to visualize the Lister's tubercle. Subsequently, it is moved distally until the scapholunate ligament is seen (Fig. 15 and 16). In order to visualize the lunotriquetral ligament, the probe should be moved towards the ulna. The US assessment involves the fibrillar echostructure of these ligaments in the long axis, which does not differ in normal conditions and in cases of partial or complete injuries from the image of other ligaments(16).

Fig. 15.

Scapholunate ligament (dorsal portion) – scanning technique. The probe should be placed transversally on the level of the Lister tubercle and then swept distally. The curved arrow demonstrates the ulnar deviation of the wrist – it is useful in the evaluation of the echostructure and integrity of the dorsal part of the scapholunate ligament

Fig. 16.

Scapholunate ligament (dorsal portion). Hand and probe position is presented in Fig. 15

In asymptomatic individuals the dorsal part of the scapholunate ligament can be fully visualized in 97% of patients, but the dorsal part of the lunotriquetral ligament can be seen in 61% of patients(17).

An ultrasound examination of the wrist is one of the most common US examinations conducted in patients with rheumatological diseases. Ultrasonographic signs depend on the advancement of the disease. Initially, only effusion and synovial thickening of the cavities, sheaths and bursae are observed. In the subsequent stage, enhanced vascularity of the synovial membrane can be seen. The stage and duration of a rheumatic condition can be determined by the presence of geodes and erosions(18). The examination is equally frequently conducted in patients with pain or swelling of the wrist due to non-rheumatological causes. The symptoms can result from the presence of ganglion cysts, posttraumatic lesions of tendons and joints or the ligament complex, neuropathies of various nature and even tumors(19–22).

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Beggs I, Bianchi S, Bueno A, Cohen M, Court-Payen M, Grainger A, et al. Musculoskeletal Ultrasound Technical Guidelines. European Society of MusculoSkeletal Radiology [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bianchi S, Martinoli C. Ultrasound of the Musculoskeletal System. Berlin – Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Holsbeeck M, Introcaso J, editors. Musculoskeletal Ultrasound. St Louis: Mosby; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 4.McNally E. Practical Musculoskeletal Ultrasound. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradley M, O'Donnell P. Atlas of Musculoskeletal Ultrasound Anatomy. Cambridge University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dębek A, Czyrny Z, Nowicki P. Sonography of pathologicalchanges in the hand. J Ultrason. 2014;14:74–88. doi: 10.15557/JoU.2014.0007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Lima JE, Kim HJ, Albertotti F, Resnick D. Intersection syndrome: MR imaging with anatomic comparison of the distal forearm. Skeletal Radiol. 2004;33:627–631. doi: 10.1007/s00256-004-0832-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Helal B, Chen SC, Iwegbu G. Rupture of the extensor pollicis longus tendon in undisplaced Colles’ type of fracture. The Hand. 1982;14:41–47. doi: 10.1016/s0072-968x(82)80038-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roth KM, Blazar PE, Earp BE, Han R, Leung A. Incidence of extensor pollicis longus tendon rupture after nondisplaced distal radius fractures. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37:942–947. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Inoue G, Tamura Y. Recurrent dislocation of the extensor carpi ulnaris tendon. Br J Sports Med. 1998;32:172–174. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.32.2.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rettig AC, Patel DV. Epidemiology of elbow, forearm, and wrist injuries in the athlete. Clin Sports Med. 1995;14:289–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Montalvan B, Parier J, Brasseur JL, Le Viet D, Drape JL. Extensor carpi ulnaris injuries in tennis players: a study of 28 cases. Br J Sports Med. 2006;40:424–429. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2005.023275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campbell D, Campbell R, O'Connor P, Hawkes R. Sports-related extensor carpi ulnaris pathology: a review of functional anatomy, sports injury and management. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47:1105–1111. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2013-092835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taljanovic MS, Goldberg MR, Sheppard JE, Rogers LF. US of the intrinsic and extrinsic wrist ligaments and triangular fibrocartilage complex – normal anatomy and imaging technique. Radiographics. 2011;31:e44. doi: 10.1148/rg.e44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berger RA. The ligaments of the wrist: a current overview of anatomy with considerations of their potential functions. Hand Clin. 1997;13:63–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taljanovic MS, Sheppard JE, Jones MD, Switlick DN, Hunter TB, Rogers LF. Sonography and sonoarthrography of the scapholunate and lunotriquetral ligaments and triangular fibrocartilage disk: initial experience and correlation with arthrography and magnetic resonance arthrography. J Ultrasound Med. 2008;27:179–191. doi: 10.7863/jum.2008.27.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boutry N, Lapegue F, Masi L, Claret A, Demondion X, Cotten A. Ultrasonographic evaluation of normal extrinsic and intrinsic carpal ligaments: preliminary experience. Skeletal Radiol. 2005;34:513–521. doi: 10.1007/s00256-005-0929-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zaniewicz-Kaniewska K, Sudoł-Szopińska I. Usefulness of sonography in the diagnosis of rheumatoid hand. J Ultrason. 2013;13:329–336. doi: 10.15557/JoU.2013.0033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Teh J, Whiteley G. MRI of soft tissue masses of the hand and wrist. Br J Radiol. 2007;80:47–63. doi: 10.1259/bjr/53596176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Teh J. Ultrasound of soft tissue masses of the hand. J Ultrason. 2012;12:381–401. doi: 10.15557/JoU.2012.0028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kowalska B, Sudoł-Szopińska I. Ultrasound assessment on selected peripheral nerve pathologies. Part I: Entrapment neuropathies of the upper limb – excluding carpal tunnel syndrome. J Ultrason. 2012;12:307–318. doi: 10.15557/JoU.2012.0016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kowalska B, Sudoł-Szopińska I. Ultrasound assessment on selected peripheral nerve pathologies. Part III: Injuries and postoperative evaluation. J Ultrason. 2013;13:82–92. doi: 10.15557/JoU.2013.0007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]