Abstract

Background

Congenital long QT syndrome type 2 (abnormal hERG potassium channel) patients can develop flat, asymmetric, and notched T waves. Similar observations have been made with a limited number of hERG‐blocking drugs. However, it is not known how additional calcium or late sodium block, that can decrease torsade risk, affects T wave morphology.

Methods and Results

Twenty‐two healthy subjects received a single dose of a pure hERG blocker (dofetilide) and 3 drugs that also block calcium or sodium (quinidine, ranolazine, and verapamil) as part of a 5‐period, placebo‐controlled cross‐over trial. At pre‐dose and 15 time‐points post‐dose, ECGs and plasma drug concentration were assessed. Patch clamp experiments were performed to assess block of hERG, calcium (L‐type) and late sodium currents for each drug. Pure hERG block (dofetilide) and strong hERG block with lesser calcium and late sodium block (quinidine) caused substantial T wave morphology changes (P<0.001). Strong late sodium current and hERG block (ranolazine) still caused T wave morphology changes (P<0.01). Strong calcium and hERG block (verapamil) did not cause T wave morphology changes. At equivalent QTc prolongation, multichannel blockers (quinidine and ranolazine) caused equal or greater T wave morphology changes compared with pure hERG block (dofetilide).

Conclusions

T wave morphology changes are directly related to amount of hERG block; however, with quinidine and ranolazine, multichannel block did not prevent T wave morphology changes. A combined approach of assessing multiple ion channels, along with ECG intervals and T wave morphology may provide the greatest insight into drug‐ion channel interactions and torsade de pointes risk.

Clinical Trial Registration

URL: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ Unique identifier: NCT01873950.

Keywords: electrocardiography, ion channels, long‐QT syndrome, pharmacology, torsade de pointes

Introduction

Long QT syndrome can be caused by congenital or acquired (eg, drug‐induced or electrolyte) abnormalities in cardiac ion channel currents regulating ventricular repolarization.1 Long QT syndrome patients are at increased risk for torsade de pointes, a potentially fatal ventricular arrhythmia.2 Conventionally, physicians and drug regulators have focused solely on the QT interval in assessing risk for torsade; however, more information may be present in the electrocardiogram (ECG). Moss and colleagues3 identified different T wave patterns associated with the 3 major congenital long QT syndrome types. LQT1 patients (decreased IKs current) have early onset broad‐based T waves, LQT2 patients (decreased hERG potassium current, IKr) have low amplitude, bifid or notched T waves, and LQT3 patients (increased late sodium current, INalate) have long isoelectric ST segments with late‐appearing, normal morphology T waves.

In the 1990s, there was recognition of an epidemic of drug‐induced QT prolongation and torsade de pointes resulting in many drugs being withdrawn from the market.4 It was also recognized that nearly all drugs that increased torsade risk blocked the hERG potassium channel.5 This resulted in all new drugs being required to be screened for their ability to block the hERG potassium channel and prolong QT in Thorough QT studies.6–7 However, the extreme focus on hERG and QT has resulted in drugs being dropped from development, sometimes inappropriately, as not all drugs with hERG block or QT prolongation cause torsade.4

There are multiple examples of drugs on the market that block the hERG channel (an outward potassium current), but have minimal‐to‐no risk for torsade due to their concurrent block of either L‐type calcium or late sodium (inward currents).8–9 Nonclinical studies have suggested that inward current block can lessen torsade risk from hERG block by decreasing dispersion of repolarization (eg, shortening action potential duration) and preventing early after depolarizations, which are the trigger for torsade.10–11 In order to understand whether drug‐induced multi‐ion channel block can be detected and differentiated on the electrocardiogram as in congenital long QT syndrome, we conducted a prospective, placebo‐controlled clinical study of dofetilide, quinidine, ranolazine, and verapamil. Dofetilide is a pure strong hERG potassium channel blocker12 with a high risk of torsade.5 Quinidine is a strong hERG potassium channel blocker that has additional weaker block of calcium and late sodium.12 Torsade has been observed to occur more frequently at lower quinidine concentrations13–14 where hERG block is present, but there is lesser calcium and sodium block. Ranolazine blocks the late sodium current and hERG approximately equally and has not been associated with torsade, and may be anti‐arrhythmic.15 Verapamil blocks calcium stronger than hERG and has low torsade risk.5,12

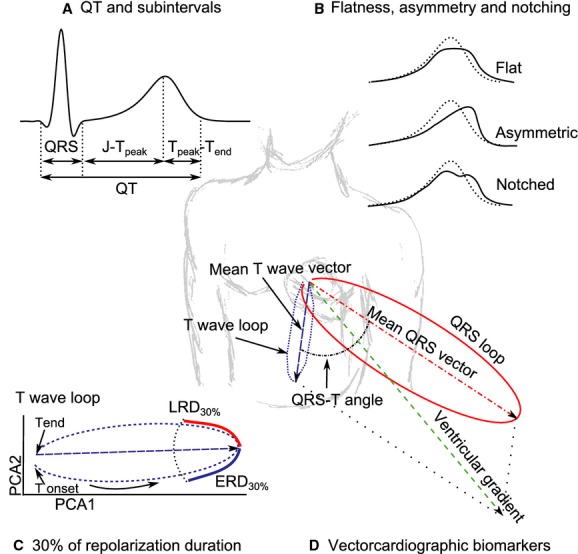

A separate study16 analyzed the J‐Tpeak and Tpeak‐Tend intervals and demonstrated that pure hERG block prolonged both J‐Tpeak and Tpeak‐Tend, while additional inward current block preferentially shortened J‐Tpeak. The objective of the current study was to evaluate the effect of pure hERG block versus multichannel block on multiple previously developed T wave morphology metrics (Figure 1). This included quantitative measures of T wave flatness, asymmetry, and notching, which were developed to detect the ECG signature of LQT2 (abnormal hERG current).17 In addition, we studied the 30% early and late repolarization duration (ERD30% and LRD30%) of the T wave loop,18–19 previously shown to detect hERG block, and other vectorcardiographic measures of the relation between depolarization and repolarization vectors (QRS‐T angle, ventricular gradient, and total cosine R‐to‐T [TCRT]), which have been shown to predict arrhythmic risk in some patient populations.20–22

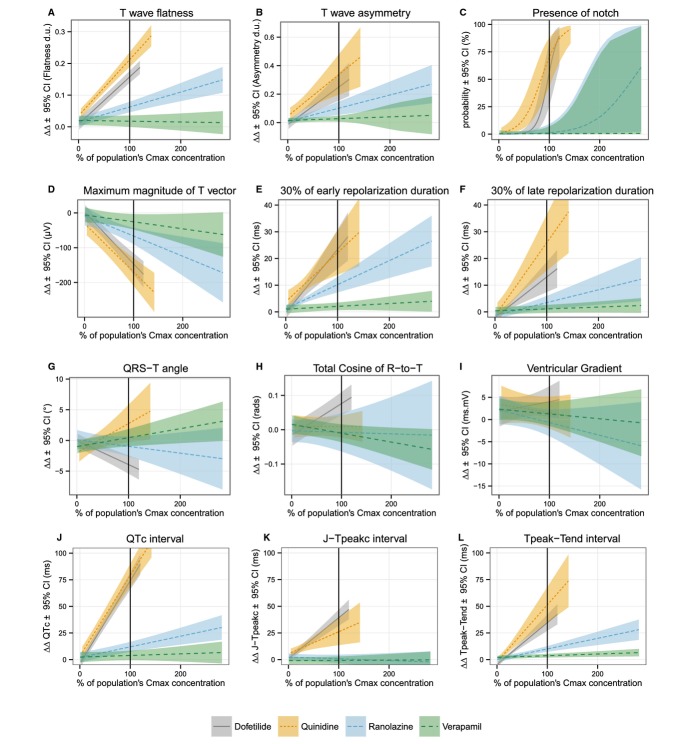

Figure 1.

Illustration showing ECG biomarkers assessed in this study: (A) QT and subintervals (QRS, J‐Tpeak and Tpeak‐Tend); (B) flat, asymmetric and notched T waves (solid lines) vs. normal T waves (dotted lines); (C) 30% of early (ERD30%) and late (LRD30%) repolarization duration in the preferential plane formed by the two‐first Eigen leads from principal component analysis (PCA1 and PCA2); (D) other vectorcardiographic biomarkers (QRS‐T angle, ventricular gradient and maximum magnitude of the T vector). See methods for further details.

Methods

Clinical Study Design

The design of this clinical study has been previously described.16 The study's inclusion and exclusion criteria were similar to those used in dedicated QT studies.6 Briefly, healthy subjects between 18 and 35 years old, weighing between 50 and 85 kg and without a family history of cardiovascular disease or unexplained sudden cardiac death were eligible for participation in the study. In addition, the subjects had to have fewer than 12 ventricular ectopic beats during a 3‐hour continuous recording at screening, as well as a baseline heart rate corrected QT (QTc) of <450 ms for men (470 ms for women), using Fridericia's correction.23 The study was designed as a randomized, double‐blind, 5‐period crossover clinical trial at a phase 1 clinical research unit (Spaulding Clinical, West Bend, WI). Williams Latin square design balanced for first‐order carryover effects24 was used for randomization.

In the morning of each period, subjects received a single dose of 500 μg dofetilide (Tikosyn, Pfizer, New York, NY), 400 mg quinidine sulfate (Watson Pharma, Corona, CA), 1500 mg ranolazine (Ranexa, Gilead, Foster City, CA), 120 mg verapamil hydrochloride (Heritage Pharmaceuticals, Edison, NJ) or placebo under fasting conditions. For dofetilide and quinidine, the selected dose was the maximum single dose allowed in the label25–26 to ensure substantial ECG changes after a single dose. The ranolazine dose was selected to achieve plasma levels close to the chronic/steady state levels, but with a single dose. This resulted in a dose higher than the clinical dose but lower than the maximum daily dose in the label.27 For verapamil, the highest initial single dose in the label was selected, and not pushed further due to concern for extreme PR prolongation and heart block in healthy subjects.28

There was a 7‐day washout period between each 24‐hour treatment period. During each period, continuous ECGs were recorded at 500 Hz and with an amplitude resolution of 2.5 μV. From the continuous recording, triplicate 10‐second ECGs were extracted at predose and 15 predefined time‐points post‐dose (0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 2.5, 3, 3.5, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 12, 14, and 24 h) during which the subjects were resting in a supine position for 10 minutes. A blood sample was drawn for pharmacokinetic analysis after each ECG extraction time‐point period and plasma drug concentration was measured using a validated liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectroscopy method by Frontage Laboratories (Exton, Philadelphia, PA). The study was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration Research Involving Human Subjects Committee and the local institutional review board. All subjects gave written informed consent.

ECG analysis

At each of the 16 time‐points, 3 optimal 10‐second 12‐lead ECGs were extracted with stable heart rates and maximum signal quality using Antares software (AMPS‐LLC, New York City, NY).29 The resulting 5232 ECGs were up‐sampled from 500 to 1000 Hz. The semi‐automatic evaluation, which included computerized interval annotations (Figure 1A) by ECG readers blinded to treatment and time, has been described elsewhere.16 T wave flatness, asymmetry, and the presence of notch were automatically assessed with QTGuard+ (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI). All the other T wave morphology and vectorcardiographic biomarkers described below were automatically assessed with ECGlib.30

T wave flatness, asymmetry, and notching

The computation of T wave flatness, asymmetry and the presence of notch (Figure 1B) has been described elsewhere.17 Briefly, a median beat was derived from the independent leads (I‐II, V1 to V6) of the 10‐second 12‐lead ECG, and morphology measures were assessed in the first Eigen lead (PCA1) after applying principal component analysis (PCA). T wave flatness is based on the inverse kurtosis (1—kurtosis) of the unit area of the T wave, thus increasing values reflect increasing flatness of the T wave (dimensionless units [d.u.]). Asymmetry score (d.u.) evaluates differences in the slope profile and duration of the ascending and descending parts of the T wave, where low values correspond with symmetric T waves and higher values with more asymmetric T waves. The presence of notch was obtained from the inverse, signed radius of curvature of the T wave, where values different from 0 correspond with the presence of notch. Notch was labeled as present if at least 1 out of the 3 ECGs of the triplicate in the corresponding time point had a notch score >0.

Percentage of early and late repolarization duration

Vectorcardiographic measurements 30% of early (ERD30%) and late (LRD30%) repolarization duration were based on the PCA transform from the ST‐T segment of the independent leads (I‐II, V1 to V6) of the 12‐lead ECG median beat. The maximum amplitude of the T vector in the preferential plane formed by the two‐first Eigen leads (PCA1 and PCA2) was selected as reference, and ERD30% and LRD30% were then measured at the time at which the amplitude decreased by 30% (Figure 1C).18

Other vectorcardiographic biomarkers

For each 12‐lead ECG median beat, we derived the Frank vectorcardiogram using Guldenring's transformation matrix.31 The QRS‐T angle was defined as the angle between the QRS and T vectors, which were defined as the summation in the X, Y, and Z leads from the QRS onset to QRS offset and QRS offset to T offset, respectively. The ventricular gradient was defined as the magnitude of the sum of the QRS and T vectors.32 The vector with the maximum magnitude between QRS offset and T offset (maximum T vector) was also computed (Figure 1D).

In addition to the QRS‐T angle described above, we also assessed the concordance between ventricular depolarization and repolarization sequences computing the total cosine R‐to‐T (TCRT).22 This descriptor is defined as the average of the cosines of the angles between a subset of QRS and T vectors in the 3 first Eigen leads (PCA1 to PCA3) derived from the PCA transform of the independent leads (I to II, V1 to V6) of the 12‐lead ECG median beat.

Analysis and removal of heart rate dependency

We determined if the T wave morphology biomarkers were dependent on heart rate, by considering if there was a statistically significant heart rate relationship as well as a meaningful change.33 For biomarkers with dependency on heart rate, we developed a study‐specific correction factor using an exponential model and allowed the relationship to be sex dependent. The heart rate correction was performed using PROC MIXED in SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), wherein a significance level of 0.05 was used to determine if there was a difference by sex.

Patch clamp experiments

Patch clamp experiments were conducted to assess the relative block of hERG, late sodium (Nav1.5) and calcium (Cav1.2) currents caused by each drug. Stably transfected hERG, Nav1.5 cells (HEK‐293), or Cav1.2 cells (CHO) were obtained from Cytocentrics Biosciences (Rostock, Germany). Cells were maintained in minimum essential medium with Earle's salts supplemented with nonessential amino acids, sodium pyruvate, penicillin, streptomycin, and fetal bovine serum.

Drugs were dissolved in either dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or deionized H2O to make stock solutions. Dilutions of stock solutions were made immediately before the experiment to create the desired concentrations. The external solution (solution bathing the cell) had an ionic composition of (in mmol/L): 137 NaCl, 4 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 1.2 MgCl2, 11 dextrose, 10 HEPES, adjusted to a pH of 7.4 with NaOH. The internal (pipette) solution had an ionic composition of (in mmol/L): 130 KCl; 1 MgCl2, 5 NaATP, 7 NaCl, 5 EGTA, 5 HEPES, pH=7.2 using KOH. Experiments were performed at 36±1°C. Drugs were obtained from Tocris Bioscience (Minneapolis, MN).

Currents were measured using the whole‐cell variant of the patch clamp method as previously described.34 After rupture of the cell membrane (entering whole‐cell mode), current amplitude and kinetics were allowed to stabilize (3 to 5 minutes) before experiments were begun. All 3 currents (hERG, Nav1.5, Cav1.2) were elicited using a ventricular action potential waveform paced at 0.1 Hz.

Statistical Analysis

The placebo‐corrected change from baseline was computed using PROC MIXED in SAS 9.3 (SAS institute, Cary, NC), where the change from baseline for each T wave morphology biomarker by time‐point was the dependent variable. Sequence, period, time, drug, and an interaction between treatment and time were included as fixed effects, and subject was included as a random effect. Afterwards, a linear‐mixed effects model was used to evaluate the relationship between each of the T wave morphology biomarkers (except notch) and plasma concentrations. This was done using PROC MIXED in SAS 9.3 using a random effect on both intercept and slope (ie, allowing each subject to have his or her own drug concentration‐biomarker relationship). A logistic regression model was used to evaluate the relationship between presence of notch and drug concentration including a random effect on intercept in SAS (PROC GLIMMIX). P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Patch clamp results are given as percentage of reduction of current amplitude, which was measured as current reduction after a steady‐state effect had been reached in the presence of drug relative to current amplitude before drug was introduced (control). Each cell served as its own control. Log‐linear plots were created from the mean percentage block±SEM at the concentrations that were tested. A nonlinear least square fitting routine was used to fit a 3‐parameter Hill equation to the results in R 3.0.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). The equation is of the following form:

where B(%) is the percentage of current blockage at drug concentration D, IC50 is the concentration of drug that causes 50% block, and n is the Hill coefficient.

Results

Twenty‐two healthy subjects (11 females) participated in this randomized controlled clinical trial; see Table 1 for baseline characteristics. All subjects completed the study except for one subject who withdrew prior to the last treatment period (quinidine period for that subject). There were no unexpected treatment related adverse events (Figure S1). Placebo changes from baseline are shown in Figure S2.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| All Subjects (N=22) | |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Age, y | 26.9±5.5 |

| Female | 11 (50%) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 23.1±2.7 |

| ECG | |

| Heart rate, beats per minute | 56.8±6.4 |

| QTc, milliseconds | 395.9±17.1 |

| JTpeakc, milliseconds | 225.6±19.8 |

| Tpeak‐Tend, milliseconds | 73.1±6.4 |

| T wave morphology | |

| Flatness, d.u. | 0.41±0.04 |

| Asymmetry, d.u. | 0.16±0.05 |

| Presence of notch, % | 0 |

| Repolarization duration | |

| ERD30%, milliseconds | 44.5±5.1 |

| LRD30%, milliseconds | 27.5±4.1 |

| Vectorcardiographic | |

| QRS‐T angle, ° | 34.5±9.9 |

| TCRT, radians | 0.67±0.24 |

| Tmagmax, μV | 578.5±173.0 |

| Ventricular gradient, mV·ms | 111.4±29.5 |

Continuous variables are represented as mean±SD of each subject's 5‐day baseline average. d.u. indicates dimensionless units; ECG, electrocardiogram; ERD30%, 30% of early repolarization duration; LRD30%, 30% of late repolarization duration; QRS‐T, angle between the mean QRS and T vectors; QTc, Fridericia's heart rate corrected QT; TCRT, total cosine R‐to‐T; Tmagmax, maximum magnitude of the T vector.

Analysis and Correction of Heart Rate Dependency

Substantial heart rate dependent change was observed for T wave flatness, maximum magnitude of the T vector and ventricular gradient. No sex‐specific differences in the heart rate dependency were found. The heart rate dependent biomarkers were corrected for heart rate in all subsequent analysis using an exponential model (biomarkerc=biomarker/RRα), where the values of α coefficient were 0.58 for T wave flatness, 0.96 for maximum magnitude of the T vector and 0.85 for ventricular gradient.

Dofetilide: Pure hERG Potassium Channel Block

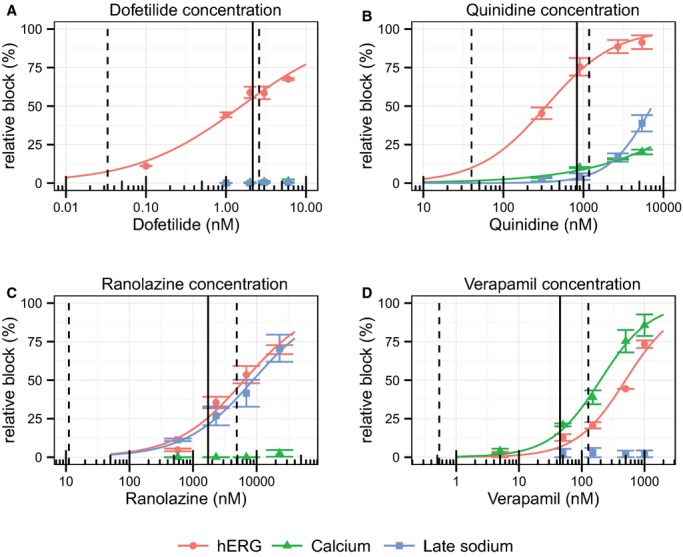

From our ion channel patch clamp experiments, dofetilide was associated with ≈55% hERG potassium channel block at the population's mean maximum concentration (Cmax); see Table 2. Dofetilide did not block calcium or late sodium currents (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Predicted Relative Channel Block and Changes in ECG Biomarkers at Cmax

| Dofetilide | Quinidine | Ranolazine | Verapamil | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population's Cmax | 2.7±0.3 ng/mL | 1.8±0.4 μg/mL | 2.3±1.4 μg/mL | 130.4±75.8 ng/mL |

| Relative block | ||||

| hERG, % | ∼55 | ∼71 | ∼26 | ∼7 |

| Calcium, % | No block | ∼8 | No block | ∼17 |

| Late sodium, % | No block | ∼3 | ∼21 | No block |

| ECG intervals | ||||

| QTc, milliseconds | 73.6‡ (65.8 to 81.5) | 78.9‡ (68.2 to 89.7) | 12.0† (7.3 to 16.7) | — |

| JTpeakc, milliseconds | 39.1‡ (31.6 to 46.6) | 26.1† (13.5 to 38.7) | — | — |

| Tpeak‐Tend, milliseconds | 34.4‡ (26.9 to 42.0) | 51.2‡ (34.6 to 67.8) | 10.0‡ (7.3 to 12.7) | 3.6* (1.9 to 5.4) |

| T wave morphology | ||||

| Flatness, d.u. | 0.16‡ (0.14 to 0.18) | 0.21‡ (0.19 to 0.23) | 0.06‡ (0.05 to 0.08) | — |

| Asymmetry, d.u. | 0.25‡ (0.16 to 0.34) | 0.34† (0.20 to 0.48) | 0.10† (0.05 to 0.15) | — |

| Notch, % | 55.0‡ (25.2 to 81.6) | 69.7‡ (43.2 to 87.5) | 1.4† (0.2 to 9.4) | — |

| Repolarization duration | ||||

| ERD30%, milliseconds | 23.3‡ (16.0 to 30.6) | 22.1† (13.9 to 30.3) | 10.2‡ (7.3 to 13.2) | — |

| LRD30%, milliseconds | 13.0‡ (7.4 to 18.6) | 25.8‡ (15.4 to 36.3) | 3.5† (0.9 to 6.0) | — |

| Vectorcardiographic | ||||

| QRS‐T angle, ° | −3.9‡ (−5.4 to −2.4) | 2.7* (−0.3 to 5.8) | — | 0.4* (−1.0 to 1.9) |

| TCRT, radians | 0.08‡ (0.04 to 0.11) | — | — | −0.01* (−0.04 to 0.02) |

| Tmagmax, μV | −145.9‡ (−176.5 to −115.2) | −169.5‡ (−209.3 to −129.7) | −66.6† (−90.3 to −42.9) | — |

| Ventricular gradient, mV ms | — | — | — | — |

Drug concentrations mean ± SD. Relative ion channel block is from the Hill equation curve shown in Figure 2 at Cmax. ECG biomarker changes reported as mean values and 95% confident intervals. d.u. indicates dimensionless units; ECG, electrocardiogram; ERD30%, 30% of early repolarization duration; hERG, hERG potassium channel; LRD30%, 30% of late repolarization duration; QRS‐T, angle between the mean QRS and T vectors; QTc, Fridericia's heart rate corrected QT; TCRT, total cosine R‐to‐T; Tmagmax, maximum magnitude of the T vector.

*P<0.05; †P<0.01; ‡P<0.001; (—) means there was no relationship between drug concentration and the ECG biomarker.

Figure 2.

Patch clamp experiment results for (A) dofetilide, (B) quinidine, (C) ranolazine, and (D) verapamil for hERG (red dots), calcium (green triangles), and late sodium (blue squares). The lines in each plot correspond to a fit between the observed means per concentration and data (see text). The error bars denote±SEM. The dashed lines in each panel correspond to the range of observed clinical concentrations and the solid line is the population average maximum concentration (Cmax). hERG indicates hERG potassium channel; Calcium, L‐type calcium current; Late sodium, late sodium current.

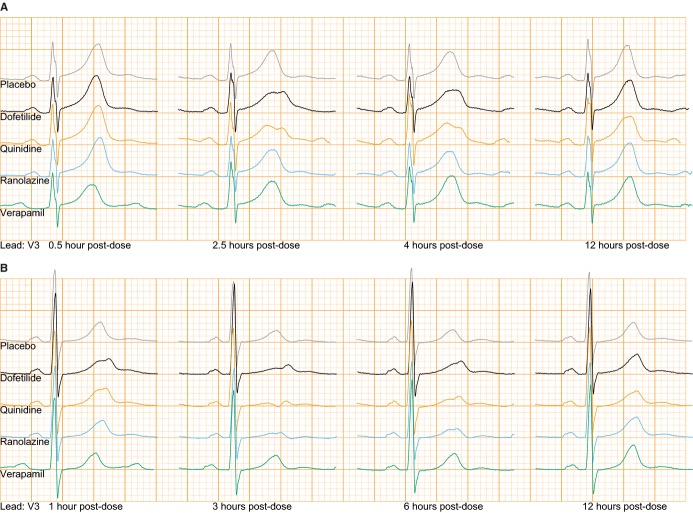

Figure 3 shows the relationships between plasma drug concentration and each T wave morphology biomarker, where the plasma concentration for each drug is normalized to the population Cmax. The actual drug concentration ranges are shown in Table 3. In addition to causing significant concentration‐dependent QTc prolongation, pure hERG potassium channel block (dofetilide) caused concentration‐dependent T wave flatness, asymmetry, and notching (see Figure 4 for ECG examples), consistent with ECG findings from LQT2 patients (abnormal hERG potassium channel).35 T wave flatness had a more consistent response than asymmetry, illustrated by the smaller confidence intervals (Figure 3), and 14 of 22 subjects developed notched T waves (Table 2). There was also a strong decrease in the maximum magnitude of the T vector (Figure 3), which is consistent with the observed T wave flatness (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Mean baseline‐ and placebo‐corrected plasma drug concentration‐dependent changes (lines) and 95% confidence intervals (shaded areas) for T wave (A) flatness, (B) asymmetry, (C) probability of presence of notch, (D) maximum magnitude of T vector, (E) 30% of early repolarization duration, (F) 30% of late repolarization duration, (G) angle between the mean QRS and T vectors (QRS‐T angle), (H) total cosine of R to T, (I) spatial ventricular gradient, (J) Fridericia's heart rate corrected QT (QTc) interval, (K) early repolarization interval (J‐Tpeakc), and (L) late repolarization interval (Tpeak‐Tend). x axis shows % of population Cmax for each drug (mean±SD): dofetilide (2.7±0.3 ng/mL, solid gray), quinidine (1.8±0.4 μg/mL, dotted orange line), ranolazine (2.3±1.4 μg/mL, blue dashed line) and verapamil (130.4±75.8 ng/mL, dashed green line). See Table 3 for detailed drug concentration ranges. Mean slopes together with 95% confidence interval values are reported in Table S1. Figures S3 through S5 show similar information in a drug‐by‐drug basis together with relative block of hERG, calcium, and late sodium currents from the patch clamp experiments. Corresponding time profile plots of drug plasma concentration and time‐matched drug‐induced changes are shown in Figures S6 through S8.

Table 3.

Drug Concentration Ranges

| Minimum (Individual) | Mean (Population's Cmax) | Maximum (Individual) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dofetilide | |||

| Plasma, ng/mL | 0.16 | 2.72 | 3.27 |

| Estimated unbound free fraction, nmol/L | 0.1 | 2.2 | 2.6 |

| Relative to population Cmax, % | 6 | 100 | 120 |

| Quinidine | |||

| Plasma, μg/mL | 0.09 | 1.79 | 2.55 |

| Estimated unbound free fraction, nmol/L | 40.0 | 829.4 | 1179.1 |

| Relative to population Cmax, % | 5 | 100 | 142 |

| Ranolazine | |||

| Plasma, μg/mL | 0.01 | 2.30 | 6.49 |

| Estimated unbound free fraction, nmol/L | 11.1 | 1726.7 | 4867.5 |

| Relative to population Cmax, % | 1 | 100 | 282 |

| Verapamil | |||

| Plasma, ng/mL | 1.55 | 130.35 | 368.00 |

| Estimated unbound free fraction, nmol/L | 0.5 | 45.1 | 127.4 |

| Relative to population Cmax, % | 1 | 100 | 282 |

Individual minimums were observed at 24 hours postdose for all drugs. See Figures S6 through S8 for concentration time profiles.

Figure 4.

Lead V3 of median beats of time‐matched placebo (gray), dofetilide (black), quinidine (orange), ranolazine (blue), and verapamil (green). Top panel (A): ECGs at 0.5, 2.5, 4, and 12 hours post‐dose from a woman with notches present in dofetilide and quinidine but not in ranolazine. Bottom panel (B): ECGs at 1, 3, 6, and 12 hours post‐dose from a woman with notches induced by ranolazine. See Table S2 for heart rate and QT/QTc measurements. ECG indicates electrocardiogram.

As with prior pure hERG blockers,18–19 dofetilide caused an increase in both ERD30% and LRD30% (Figure 3). While prior literature has suggested that a wider QRS‐T angle is associated with increased arrhythmic risk, pure hERG block caused a small decrease in the QRS‐T angle (Figure 3). A similar finding was observed for TCRT, while there was no concentration‐dependent change in the ventricular gradient (Figure 3).

Quinidine: Strong hERG Block With Additional Calcium and Sodium Block

Our patch clamp experiments (Figure 2) showed that at Cmax quinidine was associated with ≈71% hERG potassium channel block, ≈8% calcium current block and ≈3% of late sodium current block (Table 2). Thus, quinidine had stronger hERG potassium channel block than dofetilide, however quinidine had additional calcium and sodium channel block, but resulted in a similar amount of concentration‐dependent QTc prolongation for the 2 drugs (Figure 3). Quinidine was associated with similar to greater amounts of T wave flatness, asymmetry, notching (see Figure 4 for ECG examples) and a decrease in the maximum magnitude of the T vector (P<0.001 for all) compared to dofetilide (Figure 3). Notched T waves developed in 18 of 21 subjects (Table 2).

Similar to dofetilide, quinidine increased ERD30% and LRD30% (Figure 3). In contrast to the small decrease in QRS‐T angle with dofetilide, quinidine caused a small increase in the QRS‐T angle, while it had no change in TCRT or the ventricular gradient (Figure 3).

Ranolazine: Similar hERG and Late Sodium Block

From our ion channel patch clamp experiments (Figure 2), at Cmax ranolazine was associated with ≈26% hERG potassium channel block and ≈21% late sodium current block (Table 2). Ranolazine produced modest concentration‐dependent QTc prolongation of ≈13 ms at Cmax (Table 2); however it still produced significant amounts of T wave flatness and asymmetry (P<0.001) (Figure 3), along with a decrease in the maximum magnitude of the T vector (P<0.01). Furthermore, while ranolazine produced statistically significant notching for the population overall (Figure 3, Table S1), only 2 of 22 subjects developed notching (Table 2). Figure 4B shows the ECG traces of one of the subjects who developed notching with ranolazine. Of note, this woman had the second highest plasma concentration of ranolazine (6.14 μg/mL) of all subjects in this study, and notches in the T wave were observed at concentrations exceeding 2.45 μg/mL. This subject had even more severe T wave morphology changes with dofetilide and quinidine (Figure 4B). Like dofetilide and quinidine, ranolazine caused an increase in both ERD30% and LRD30% (Figure 3). Ranolazine did not cause a change in the QRS‐T angle, TCRT or ventricular gradient (Figure 3).

Verapamil: Calcium Block Stronger Than hERG Block

From our ion channel patch clamp experiments (Figure 2), at Cmax verapamil was associated with ≈17% of calcium current block and ≈7% hERG potassium channel block (Table 2). Verapamil did not cause a meaningful change in QTc (Figure 3) or any of the T wave morphology markers (Figure 3) at the plasma concentrations observed in this study. Of note, as described previously,16 verapamil did cause a substantial 32.1 [95% confidence interval: 26.7 to 37.4] ms (P<0.001) increase in the PR interval, demonstrating that the plasma concentrations in this study were sufficient to elicit an electrophysiological effect. The lack of T wave morphology changes observed in this study suggests that competing effects of inward current block from calcium and outward current block from hERG potassium during ventricular repolarization are very well balanced with verapamil.

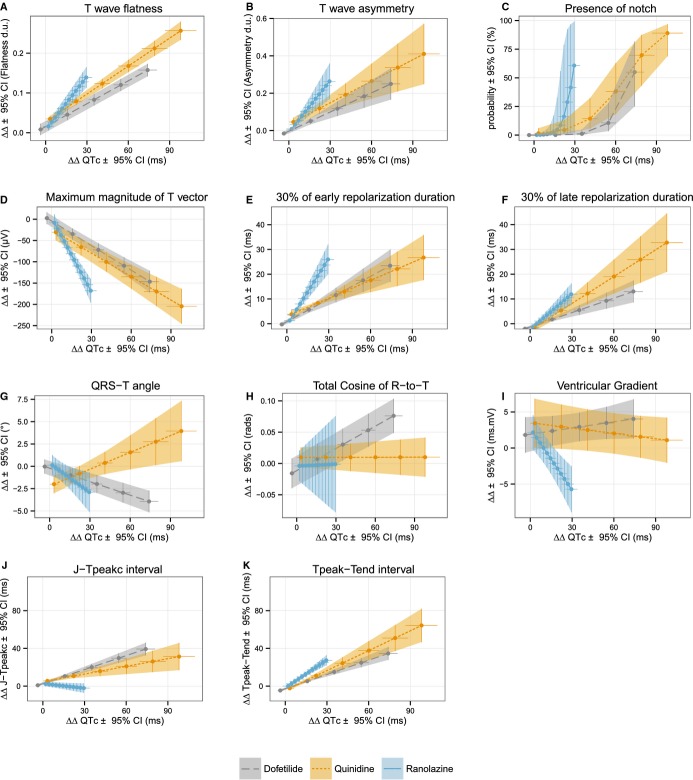

Relation Between QTc and T Wave Morphology Metrics

We used the concentration‐response models to predict the individual drug‐induced changes for QTc and each T wave morphology biomarker at 25% increments of the population's Cmax of each drug. Figure 5 shows the relationship between changes in QTc and changes in T wave morphology biomarkers for dofetilide, quinidine, and ranolazine. At equivalent drug‐induced QTc prolongation, quinidine and ranolazine (multichannel blockers) induced similar to or slightly greater T wave morphology changes than did dofetilide (pure hERG potassium channel blocker).

Figure 5.

Relationship between predicted drug‐induced baseline‐ and placebo‐corrected changes in QTc (x axis) and T wave (A) flatness, (B) asymmetry, (C) probability of presence of notch, (D) maximum magnitude of T vector, (E) 30% of early repolarization duration, (F) 30% of late repolarization duration, (G) angle between the mean QRS and T vectors (QRS‐T angle), (H) total cosine of R to T, (I) spatial ventricular gradient, (J) early repolarization interval (J‐Tpeakc), and (K) late repolarization interval (Tpeak‐Tend) (y axis). Average predictions (dots) and 95% confidence intervals (horizontal and vertical lines) from concentration dependent models for QTc (x axis) and the different T wave morphology biomarkers (y axis) at baseline and 25% increments of population's Cmax for dofetilide (dashed gray line) quinidine (dotted orange line) and ranolazine (solid blue line). QTc, Fridericia's heart rate corrected QT.

Discussion

This study observed that pure hERG potassium channel block with dofetilide causes substantial concentration‐dependent T wave flatness, asymmetry, and notching, along with a decrease in the maximum magnitude of the T vector. These quantitative T wave biomarkers were originally developed to detect the ECG signature of congenital LQT2 (decreased hERG potassium channel current), and this study strongly supports that these biomarkers capture that ECG phenotype. This study was novel and unique in that the same subjects received 3 additional hERG potassium channel blockers (quinidine, ranolazine, and verapamil) that also block inward currents (calcium or late sodium) during repolarization. hERG blocking drugs that also block inward currents have been observed to have a lower torsade risk, either because they decrease dispersion of repolarization (the substrate for re‐entry)10 or they prevent early afterdepolarizations (the trigger for torsade).11 We observed that quinidine and ranolazine both still caused T wave morphology changes, despite inward current block.

This raises the question of how T wave morphology changes relate to risk for drug‐induced torsade de pointes. While quinidine, ranolazine, and verapamil are multichannel blockers, only quinidine is associated with a significant torsade risk. This is likely due to quinidine's substantially greater hERG block (≈71%) than calcium and late sodium block (≈8% and 3%, respectively) at Cmax. Furthermore, at lower concentrations (see Figure 2) quinidine is a relatively pure hERG blocker, and torsade de pointes events with quinidine have been observed to occur more frequently at lower concentrations.13 Compared with quinidine, ranolazine was associated with less hERG block (≈26%) and more late sodium current block (≈21%), while verapamil was associated with only ≈7% hERG block and ≈17% calcium block. Moreover, there was no increase in QTc or change in T wave morphology associated with verapamil in this study, suggesting that verapamil has almost perfectly balanced inward (calcium) and outward (hERG) current block. Thus, it is likely not just the presence of calcium or late sodium current block that can prevent torsade, but rather the balance between inward and outward current block that is most important.

Taken together with our prior observations that calcium and late sodium block primarily affect early repolarization by shortening the J‐Tpeakc interval,16,33 results suggest that the strongest effect of calcium and late sodium block may be to shift the T wave to the left (shorter ST segment duration), with a lesser effect on T wave morphology. The opposite effect is seen with LQT3, where the abnormally increased late sodium current results in a long ST segment duration, with a late appearing T wave of unchanged morphology.3 Overall, while flat, asymmetric, and notched T waves appear to be biomarkers of hERG block, these T wave morphology markers likely do not always correlate with torsade de pointes risk, as has also been observed for QTc. The relationship between events of torsade de pointes and the relative amount of hERG block compared to additional calcium or late sodium block deserves further investigation with a large number of drugs, as has been proposed under the Comprehensive in vitro Proarrhythmia Assay (CiPA) initiative.36

T Wave Loop Biomarkers

In addition to assessing T wave flatness, asymmetry, and notching, we assessed a series of T wave loop biomarkers. ERD30% and LRD30% measure the time from the peak of the T wave loop to 30% of the baseline toward the beginning of the T wave (ERD30%) and end of the T wave (LRD30%), respectively. These markers were developed to be sensitive detectors of hERG potassium channel block and were previously assessed with moxifloxacin18 and d,l‐sotalol.37 The results of the present study confirm that ERD30% and LRD30% are indeed sensitive markers of hERG block from dofetilide, quinidine, and ranolazine. When assessing the relative changes of these biomarkers compared with the amount of QTc change (Figure 5), there was a similar amount of change in LRD30% for dofetilide, quinidine, and ranolazine. For ERD30%, dofetilide and quinidine were similar, while ranolazine induced a greater relative change in ERD30%; how this relates to cardiac safety is unknown.

Prior research has suggested that patients with a wide QRS‐T angle are at increased risk for ventricular arrhythmias and sudden death.20–21 Similar observations have been reported with the TCRT in other patient populations (hypertrophic cardiomyopathy22 and post‐myocardial infarction38), where a decrease in TCRT is equivalent to a wider QRS‐T angle. However, in this study pure hERG potassium channel block (dofetilide) did not cause an increase in the QRS‐T angle, but rather caused a small decrease. In contrast, quinidine caused a small increase in the QRS‐T angle. The small magnitude of the changes (≈5° at Cmax) suggests that these changes are likely not clinically meaningful and these indices do not appear to have value for detecting hERG potassium channel block. There was also no change in the ventricular gradient with any drug, which has been proposed as a global marker of action potential morphology heterogeneity.32

Our results show heart rate dependency for the maximum magnitude of the T vector, which is in concordance with previous studies.39–40 Andersen et al40 reported T wave flatness as heart rate independent, but our results show T wave flatness being heart rate dependent. The present study had a larger range of heart rates, and thus T wave flatness likely is heart rate dependent.

Limitations

This study involved only a single dose of each drug and it is possible that different doses or chronic dosing would have different effects on T wave morphology. We partially addressed this limitation by administering large doses of dofetilide, quinidine, and ranolazine and performing concentration‐dependent analysis with 15 matched ECG and plasma samples for each subject with each drug. This resulted in a large range of plasma concentrations representative of chronic/steady state dosing levels for all drugs, although the population Cmax values for quinidine and verapamil were at the low end of the clinical range. All 4 drugs included in this study block the hERG potassium channel, thus late sodium or calcium effects on T wave morphology could not be assessed independently. To address this limitation, we assessed each of the drugs in a standardized patch clamp protocol on hERG, calcium, and late sodium currents.

All T wave morphology biomarkers were computed automatically, so incorrect determination of the peak of the T wave could affect the results. However, the large number of pharmacokinetic samples (15) after each drug administration coupled with triplicate ECG measurements minimizes this limitation. Although ECGs were extracted during periods of 10 minutes of supine resting, quinidine and verapamil induced heart rate changes. This effect was minimized by assessing the heart rate dependency for each biomarker and developing correction formulas when indicated.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that there is a strong dose‐response relationship between hERG potassium channel block and T wave morphology changes. While nonclinical studies have suggested that late sodium current block can reduce dispersion of repolarization from hERG block, we observed that ranolazine still had a dose dependent relationship with T wave morphology, in some cases having greater T wave morphology changes at equivalent amounts of QTc prolongation compa‐red with the pure hERG blocker dofetilide. Thus, the presence of T wave morphology changes is not a perfect predictor of torsade de pointes risk. However, this study supports that T wave morphology biomarkers (eg, flatness, asymmetry, and notching, along with a decrease in the maximum magnitude of the T vector) likely have value in determining if QT prolongation is due to hERG block. Subsequently, analysis of J‐Tpeak and Tpeak‐Tend intervals may be able to inform whether a hERG‐blocking drug has additional late sodium or calcium current block that can mitigate torsade risk, as with ranolazine. Overall, the ECG signatures of drug‐induced ion channel block closely parallel the ECG signatures seen with congenital long QT syndromes and a combined approach of assessing multiple ion channels, subintervals of the QT (eg, J‐Tpeak and Tpeak‐Tend) and T wave morphology can provide the greatest insight into drug‐ion channel interactions and torsade de pointes risk.

Acknowledgments

QTGuard+ was provided by GE Healthcare through a material transfer agreement. The mention of commercial products, their sources, or their use in connection with material reported herein is not to be construed as either an actual or implied endorsement of such products by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Supplementary Material

Table S1. Relationship between plasma drug concentrations and ECG measurements that correlate with graphs in Figure 2.

Table S2. Global measurements of ECGs shown in Figure 3.

Figure S1. Placebo changes from baseline for (a) T wave flatness, (b) asymmetry, (c) probability of notch, (d) maximum magnitude of the T vector, (e) 30% of early repolarization duration, (f) 30% of late repolarization duration, (g) QRS-T angle, (h) total cosine R-to-T, (i) ventricular gradient, (j) QTc, (k) J-Tpeakc and (l) Tpeak-Tend-.

Figure S2. Patch clamp experiments results for (a) dofetilide, (b) quinidine, (c) ranolazine and (d) verapamil for hERG (red), calcium (green) and late sodium (blue).

Figure S3. Patch clamp experiments results for (a) dofetilide, (b) quinidine, (c) ranolazine and (d) verapamil for hERG (red), calcium (green) and late sodium (blue).

Figure S4. Patch clamp experiments results for (a) dofetilide, (b) quinidine, (c) ranolazine and (d) verapamil for hERG (red), calcium (green) and late sodium (blue).

Figure S5. Patch clamp experiments results for (a) dofetilide, (b) quinidine, (c) ranolazine and (d) verapamil for hERG (red), calcium (green) and late sodium (blue).

Figure S6. Time profiles of average plasma drug concentration for (a) dofetilide, (b) quinidine, (c) ranolazine and (d) verapamil for hERG (red), calcium (green) and late sodium (blue).

Figure S7. Time profiles of average plasma drug concentration for (a) dofetilide, (b) quinidine, (c) ranolazine and (d) verapamil for hERG (red), calcium (green) and late sodium (blue).

Figure S8. Time profiles of average plasma drug concentration for (a) dofetilide, (b) quinidine, (c) ranolazine and (d) verapamil for hERG (red), calcium (green) and late sodium (blue).

Sources of Funding

This study was supported by U.S. Food and Drug Administration's Critical Path Initiative, U.S. Food and Drug Administration's Office of Women's Health, and appointments to the Research Participation Program at the Center for Devices and Radiological Health administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education through an interagency agreement between the U.S. Department of Energy and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Pueyo is funded by Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (MINECO), Spain, under project TIN2013‐41998‐R and by Grupo Consolidado BSICoS from DGA (Aragón) and European Social Fund (EU).

Disclosures

None.

References

- Antzelevitch C, Shimizu W. Cellular mechanisms underlying the long QT syndrome. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2002; 17:43-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauer AJ, Newton‐Cheh C. Clinical and genetic determinants of torsade de pointes risk. Circulation. 2012; 125:1684-1694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss AJ, Zareba W, Benhorin J, Locati EH, Hall WJ, Robinson JL, Schwartz PJ, Towbin JA, Vincent GM, Lehmann MH. ECG T‐wave patterns in genetically distinct forms of the hereditary long QT syndrome. Circulation. 1995; 92:2929-2934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockbridge N, Morganroth J, Shah R, Garnett C. Dealing with global safety issues: was the response to QT‐liability of non‐cardiac drugs well coordinated? Drug Saf. 2013; 36:167-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redfern WS, Carlsson L, Davis AS, Lynch WG, MacKenzie I, Palethorpe S, Siegl PKS, Strang I, Sullivan AT, Wallis R, Camm AJ, Hammond TGB. Relationships between preclinical cardiac electrophysiology, clinical QT interval prolongation and torsade de pointes for a broad range of drugs: evidence for a provisional safety margin in drug development. Cardiovasc Res. 2003; 58:32-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry E14 Clinical Evaluation of QT/QTc Interval Prolongation and Proarrhythmic Potential for Non‐Antiarrhythmic Drugs. 2005. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidancecomplianceregulatoryinformation/guidances/ucm073153.pdf. Accessed March 26, 2015.

- International Conference on Harmonisation. ICH Topic S7B The nonclinical Evaluation of the Potential for Delayed Ventricular Repolarization (QT Interval Prolongation) by Human Pharmaceuticals. 2005. Available at: http://www.ich.org/fileadmin/Public_Web_Site/ICH_Products/Guidelines/Safety/S7B/Step4/S7B_Guideline.pdf. Accessed March 26, 2015. [PubMed]

- Hohnloser SH, Klingenheben T, Singh BN. Amiodarone‐associated proarrhythmic effects. A review with special reference to torsade de pointes tachycardia. Ann Intern Med. 1994; 121:529-535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiba T, Shimizu W, Inagaki M, Noda T, Miyoshi S, Ding WG, Zankov DP, Toyoda F, Matsuura H, Horie M, Sunagawa K. Cellular and ionic mechanism for drug‐induced long QT syndrome and effectiveness of verapamil. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005; 45:300-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antzelevitch C. Role of transmural dispersion of repolarization in the genesis of drug‐induced torsades de pointes. Heart Rhythm. 2005; 2:S9-S15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- January CT, Riddle JM. Early afterdepolarizations: mechanism of induction and block. A role for L‐type Ca2+ current. Circ Res. 1989; 64:977-990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer J, Obejero‐Paz CA, Myatt G, Kuryshev YA, Bruening‐Wright A, Verducci JS, Brown AM. MICE models: superior to the HERG model in predicting Torsade de Pointes. Sci Rep. 2013; 3:2100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roden D, Woosley R, Primm R. Incidence and clinical features of the quinidine‐associated long QT syndrome: implications for patient care. Am Heart J. 1986; 111:1088-1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L, Guo D, Li H, Hackett J, Yan GX, Jiao Z, Antzelevitch C, Shryock JC, Belardinelli L. Role of late sodium current in modulating the proarrhythmic and antiarrhythmic effects of quinidine. Heart Rhythm. 2008; 5:1726-1734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antzelevitch C, Belardinelli L, Zygmunt AC, Burashnikov A, Di Diego JM, Fish JM, Cordeiro JM, Thomas G. Electrophysiological effects of ranolazine, a novel antianginal agent with antiarrhythmic properties. Circulation. 2004; 110:904-910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannesen L, Vicente J, Mason JW, Sanabria C, Waite‐Labott K, Hong M, Guo P, Lin J, Sorensen JS, Galeotti L, Florian J, Ugander M, Stockbridge N, Strauss DG. Differentiating drug‐induced multichannel block on the electrocardiogram: randomized study of dofetilide, quinidine, ranolazine, and verapamil. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2014; 96:549-558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen MP, Xue J, Graff C, Hardahl TB, Toft E, Kanters JK, Christiansen M, Jensen HK, Struijk JJ. A robust method for quantification of IKr‐related T‐wave morphology abnormalities. Comput Cardiol. 2007; 34:341-344. [Google Scholar]

- Couderc JP, Vaglio M, Xia X, McNitt S, Hyrien O. Electrocardiographic method for identifying drug‐induced repolarization abnormalities associated with a reduction of the rapidly activating delayed rectifier potassium current. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2006; 1:4010-4015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couderc JP, McNitt S, Hyrien O, Vaglio M, Xia X, Polonsky S, Moss A, Zareba W. Improving the detection of subtle I(Kr)‐inhibition: assessing electrocardiographic abnormalities of repolarization induced by moxifloxacin. Drug Saf. 2008; 31:249-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kardys I, Kors JA, van der Meer IM, Hofman A, van der Kuip DA, Witteman JC. Spatial QRS‐T angle predicts cardiac death in a general population. Eur Heart J. 2003; 24:1357-1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whang W, Shimbo D, Leviatan E, Newman J, Rautaharju P, Muntner P. Relations between QRS|T angle, cardiac risk factors, and mortality in the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). Am J Cardiol. 2012; 109:981-987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acar B, Yi G, Hnatkova K, Malik M. Spatial, temporal and wavefront direction characteristics of 12‐lead T‐wave morphology. Med Biol Eng Comput. 1999; 37:574-584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fridericia LS. Die Systolendauer im Elektrokardiogramm bei normalen Menschen und bei Herzkranken. Acta Med Scand. 1920; 53:469-486. [Google Scholar]

- Williams E. Experimental designs balanced for the estimation of residual effects of treatments. Aust J Chem. 1949; 2:149-168. [Google Scholar]

- Drugs@FDA. Dofetilide label. 2013. Available at: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2013/020931s007lbl.pdf Accessed March 26, 2015.

- DailyMed. Quinidine sulfate label. 2012. Available at: http://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=a90a03b0-ffbe-4cf6-90b5-bfb0412a1cb2. Accessed March 26, 2015.

- Drugs@FDA. Ranolazine label. 2013. Available at: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2013/021526s026lbl.pdf. Accessed March 26, 2015.

- DailyMed. Verapamil label. 2014. Available at: http://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=10881745-3a16-44c3-9b94-60433218f1d6. Accessed March 26, 2015.

- Badilini F, Vaglio M, Sarapa N. Automatic extraction of ECG strips from continuous 12‐lead holter recordings for QT analysis at prescheduled versus optimized time points. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2009; 14:S22-S29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannesen L, Vicente J, Galeotti L, Strauss DG. EGClib: library for processing electrocardiograms. Comput Cardiol. 2013; 40:951-954. [Google Scholar]

- Guldenring D, Finaly D, Strauss D, Galeotti L, Nugent C, Donnelly M, Bond R. Transformation of the Mason‐Likar 12‐lead electrocardiogram to the Frank vectorcardiogram. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2012; 000:677-680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draisma HH, Schalij MJ, Wall E, Swenne CA. Elucidation of the spatial ventricular gradient and its link with dispersion of repolarization. Heart Rhythm. 2006; 3:1092-1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannesen L, Vicente J, Gray RA, Galeotti L, Loring Z, Garnett CE, Florian JA, Ugander M, Stockbridge N, Strauss DG. Improving the assessment of heart toxicity for all new drugs through translational regulatory science. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2014; 95:501-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crumb WJ, Pigott JD, Clarkson CW. Description of a nonselective cation current in human atrium. Circ Res. 1995; 77:950-956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupoglazoff JM, Denjoy I, Berthet M, Neyroud N, Demay L, Richard P, Hainque B, Vaksmann G, Klug D, Leenhardt A, Maillard G, Coumel P, Guicheney P. Notched T waves on Holter recordings enhance detection of patients with LQT2 (HERG) mutations. Circulation. 2001; 103:1095-1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sager PT, Gintant G, Turner JR, Pettit S, Stockbridge N. Rechanneling the cardiac proarrhythmia safety paradigm: a meeting report from the Cardiac Safety Research Consortium. Am Heart J. 2014; 167:292-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couderc JP, Zhou M, Sarapa N, Zareba W. Investigating the effect of sotalol on the repolarization intervals in healthy young individuals. J Electrocardiol. 2008; 41:595-602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabel M, Acar B, Klingenheben T, Franz MR, Hohnloser SH, Malik M. Analysis of 12‐lead T‐wave morphology for risk stratification after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2000; 102:1252-1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couderc JP, Vaglio M, Xia X, Mcnitt S, Wicker P, Sarapa N, Moss AJ, Zareba W. Impaired T‐amplitude adaptation to heart rate characterizes IKr inhibition in the congenital and acquired forms of the long QT syndrome. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2007; 18:1299-1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen MP, Xue JQ, Graff C, Kanters JK, Toft E, Struijk JJ. New descriptors of T‐wave morphology are independent of heart rate. J Electrocardiol. 2008; 41:557-561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Relationship between plasma drug concentrations and ECG measurements that correlate with graphs in Figure 2.

Table S2. Global measurements of ECGs shown in Figure 3.

Figure S1. Placebo changes from baseline for (a) T wave flatness, (b) asymmetry, (c) probability of notch, (d) maximum magnitude of the T vector, (e) 30% of early repolarization duration, (f) 30% of late repolarization duration, (g) QRS-T angle, (h) total cosine R-to-T, (i) ventricular gradient, (j) QTc, (k) J-Tpeakc and (l) Tpeak-Tend-.

Figure S2. Patch clamp experiments results for (a) dofetilide, (b) quinidine, (c) ranolazine and (d) verapamil for hERG (red), calcium (green) and late sodium (blue).

Figure S3. Patch clamp experiments results for (a) dofetilide, (b) quinidine, (c) ranolazine and (d) verapamil for hERG (red), calcium (green) and late sodium (blue).

Figure S4. Patch clamp experiments results for (a) dofetilide, (b) quinidine, (c) ranolazine and (d) verapamil for hERG (red), calcium (green) and late sodium (blue).

Figure S5. Patch clamp experiments results for (a) dofetilide, (b) quinidine, (c) ranolazine and (d) verapamil for hERG (red), calcium (green) and late sodium (blue).

Figure S6. Time profiles of average plasma drug concentration for (a) dofetilide, (b) quinidine, (c) ranolazine and (d) verapamil for hERG (red), calcium (green) and late sodium (blue).

Figure S7. Time profiles of average plasma drug concentration for (a) dofetilide, (b) quinidine, (c) ranolazine and (d) verapamil for hERG (red), calcium (green) and late sodium (blue).

Figure S8. Time profiles of average plasma drug concentration for (a) dofetilide, (b) quinidine, (c) ranolazine and (d) verapamil for hERG (red), calcium (green) and late sodium (blue).