Abstract

An accessory spleen is a congenital malformation, which is defined as ectopic splenic parenchyma. Here, an extremely rare case of a right retroperitoneal accessory spleen, mimicking a retroperitoneal neoplasm, is reported. A 40-year-old woman was referred following the incidental detection of a retroperitoneal neoplasm. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging scans confirmed the presence of a retroperitoneal neoplasm at the hepatorenal recess. Retroperitoneoscopic excision was conducted, with excellent results. Pathological examination of the resected specimen revealed splenic tissue. In conjunction with a review of the literature and a discussion of the salient radiological features, the present case highlights the requirement for accurate preoperative diagnosis of an accessory spleen in the right retroperitoneal space, in order to avoid unnecessary surgical intervention.

Keywords: accessory spleen, retroperitoneal, ectopic

Introduction

An accessory spleen is a congenital defect, defined as ectopic splenic parenchyma separated from the main body of the spleen. Although the majority are benign and do not usually require treatment, they may be mistaken for enlarged lymph nodes or neoplasms. Primary retroperitoneal neoplasms are a group of rare but diverse neoplasms that arise within the retroperitoneal space, which account for 0.1–0.2% of all malignancies in the body. Notably, 80–90% of all primary retroperitoneal tumors are malignant (1,2). Primary retroperitoneal neoplasms are classified as solid or cystic masses. Solid neoplasms are divided into three main categories according to the tissue of origin: Mesodermal tumors, neurogenic tumors and extragonadal germ cell tumors (3). Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are essential for the characterization of primary retroperitoneal neoplasms, evaluating the extent of local invasion, identification of metastases, and determination of the optimal treatment response for such neoplasms (4). Therefore accurate preoperative diagnosis is important in order to avoid unnecessary surgical intervention. The current report discusses the case of a patient with a right retroperitoneal accessory spleen, mimicking a retroperitoneal neoplasm. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient's family.

Case report

A 40-year-old woman without any abdominal discomfort was referred to Zhejiang Hospital (Zhejiang, China) for surgical excision, following the incidental detection by B ultrasound of a right retroperitoneal neoplasm at Zhejiang Hospital. Routine physical examination and laboratory data, including full blood count, blood glucose, C-reactive protein, tumor markers and liver function tests, were all unremarkable. Her medical history was notable for a splenectomy performed in 2002, for splenic rupture as a result of upper abdominal trauma.

Ultrasonography demonstrated a space-occupying neoplasm, with a less abundant vascular supply than the surrounding normal tissue, located in the right retroperitoneal space (Fig. 1). CT imaging revealed a well-marginated ovoid neoplasm, of ~38.0×25.0 mm, in the right retroperitoneal space. An MRI scan further confirmed the presence of a neoplasm, with low signal intensity on T1-weighted images, high signal intensity on T2-weighted images and slightly enhanced signal intensity on the contrast-enhanced phases of dynamic MRI (Fig. 2). As a retroperitoneal neoplasm of unknown origin had been identified, a retroperitoneoscopic excision was conducted in order to remove the neoplasm with minimal invasiveness. Pathological examination of the resected specimen demonstrated splenic tissue (Fig. 3). The patient recovered well post-operatively.

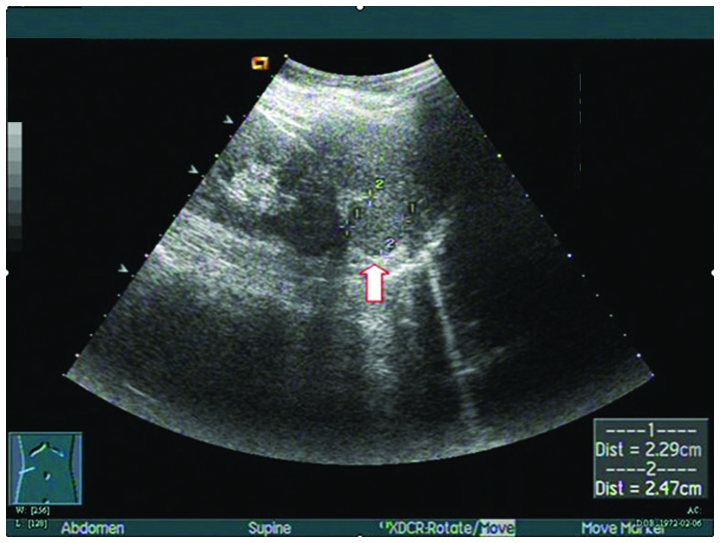

Figure 1.

Ultrasonography demonstrated a space-occupying neoplasm (arrow), with a less abundant vascular supply than surrounding normal tissue, in the right retroperitoneal space.

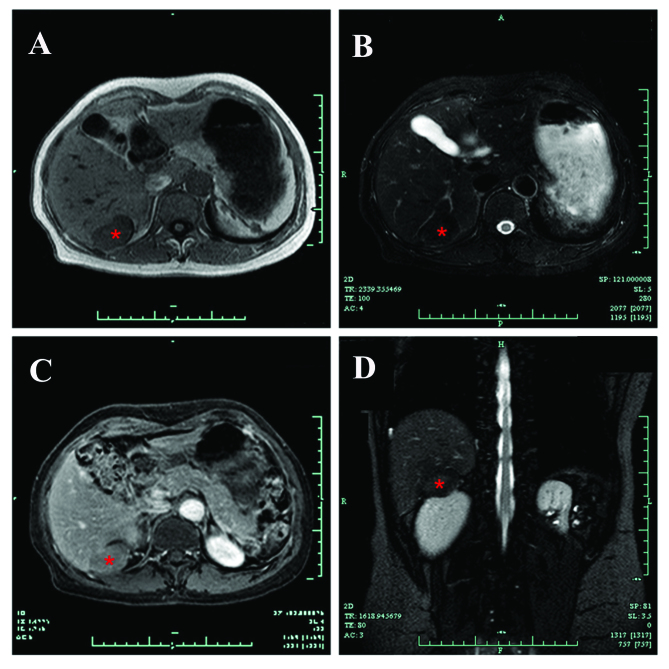

Figure 2.

MRI confirmed the presence of a solid neoplasm (asterisk), with (A) low signal intensity on T1-weighted images and (B) high signal intensity on T2-weighted images. (C) The signal intensity of the neoplasm was slightly enhanced on the contrast-enhanced phases of dynamic MRI. (D) Coronal T2-weighted images.

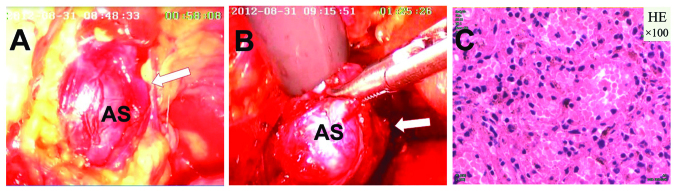

Figure 3.

(A and B) Retroperitoneoscopic photograph demonstrating the accessory spleen (arrow). (C) Pathological examination of the resected specimen revealed splenic tissue (HE stain; magnification, x100). AS, accessory spleen; HE, hematoxylin and eosin.

Discussion

Primary retroperitoneal neoplasms are relatively rare. Malignant primary retroperitoneal neoplasms, which are more common than benign neoplasms in the retroperitoneal neoplasm, account for ~0.1% of all malignancies (5). When a retroperitoneal neoplasm of unknown origin is detected, surgical removal may be conducted and a definitive diagnosis may be made following pathological examination of the surgical specimen (2).

An accessory spleen is a common congenital defect that affects 10–30% of the population (6). They are generally small (15.0–20.0 mm) and are primarily located in the splenic hilum (75%) or in the tail of the pancreas (20%) (7). Occasionally they may be located in the splenorenal ligament, greater omentum, mesentery, presacral area, adnexal region, scrotum, pelvic cavity, liver or the thorax (8–12). Although an accessory spleen usually presents as an isolated asymptomatic abnormality, it may have clinical significance as it may be mistaken for an enlarged lymph node or a neoplasm. Therefore, the accurate preoperative diagnosis of an accessory spleen is important in order to avoid unnecessary surgery. CT/MRI and scintigraphy with Tc-99 m are helpful in marking the diagnosis of an accessory spleen (4).

In conclusion, the presence of an accessory spleen in the right retroperitoneal space is extremely rare (2). When a retroperitoneal neoplasm is detected, surgeons should be aware of the possibility of an accessory spleen in this location, in order to make precise preoperative diagnoses.

References

- 1.Osman S, Lehnert BE, Elojeimy S, Cruite I, Mannelli L, Bhargava P, Moshiri M. A comprehensive review of the retroperitoneal anatomy, neoplasms, and pattern of disease spread. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2013;42:191–208. doi: 10.1067/j.cpradiol.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tambo M, Fujimoto K, Miyake M, Hoshiyama F, Matsushita C, Hirao Y. Clinicopathological review of 46 primary retroperitoneal tumors. Int J Urol. 2007;14:785–788. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2007.01839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shah JD, Kirshenbaum M, Shah KD. CT characteristics of primary retroperitoneal tumors and the importance of differentiation from secondary retroperitoneal tumors. Contemp Diagn Radiol. 2008;31:1–5. doi: 10.1097/01.CDR.0000330318.45238.55. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang C, Zhang XF. Accessory spleen in the greater omentum. Am J Surg. 2011;202:e28–e30. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2010.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim MK, Im CM, Oh SH, Kwon DD, Park K, Ryu SB. Unusual presentation of right-side accessory spleen mimicking a retroperitoneal tumor. Int J Urol. 2008;15:739–740. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2008.02078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gardikis S, Pitiakoudis M, Sigalas I, Theocharous E, Simopoulos C. Infarction of an accessory spleen presenting as acute abdomen in a neonate. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2005;15:203–205. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-837605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang KR, Jia HM. Symptomatic accessory spleen. Surgery. 2008;144:476–477. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2007.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cowles RA, Lazar EL. Symptomatic pelvic accessory spleen. Am J Surg. 2007;194:225–226. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee HJ, Kim YT, Kang CH, Kim JH. An accessory spleen misrecognized as an intrathoracic mass. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2005;28:640. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2005.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lhuaire M, Sommacale D, Piardi T, Grenier P, Diebold MD, Avisse C, Kianmanesh R. A rare cause of chronic abdominal pain: Recurrent sub-torsions of an accessory spleen. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:1893–1896. doi: 10.1007/s11605-013-2239-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodriguez E, Netto G, Li QK. Intrapancreatic accessory spleen: A case report and review of literature. Diagn Cytopathol. 2013;41:466–469. doi: 10.1002/dc.22813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Izzo L, Caputo M, Galati G. Intrahepatic accessory spleen: Imaging features. Liver Int. 2004;24:216–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2004.00915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]