Abstract

Education scholarship on race using quantitative data analysis consists largely of studies on the black-white dichotomy, and more recently, on the experiences of student within conventional racial/ethnic categories (white, Hispanic/Latina/o, Asian, black). Despite substantial shifts in the racial and ethnic composition of American children, studies continue to overlook the diverse racialized experiences for students of Asian and Latina/o descent, the racialization of immigration status, and the educational experiences of Native American students. This study provides one possible strategy for developing multidimensional measures of race using large-scale datasets and demonstrates the utility of multidimensional measures for examining educational inequality, using teacher perceptions of student behavior as a case in point. With data from the first grade wave of the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Kindergarten Cohort of 1998–1999, I examine differences in teacher ratings of Externalizing Problem Behaviors and Approaches to Learning across fourteen racialized subgroups at the intersections of race, ethnicity, and immigrant status. Results show substantial subgroup variation in teacher perceptions of problem and learning behaviors, while also highlighting key points of divergence and convergence within conventional racial/ethnic categories.

Keywords: race and ethnicity, immigration status, teacher perceptions, inequality, multidimensional measure of race

Scholars interested in educational inequality often focus on racial/ethnic differences in schooling experiences and outcomes. While quantitative scholars have historically centered on black-white differences, many now rely on conventional racial/ethnic categories (e.g., white, black, Asian, Hispanic/Latina/o), as outlined by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) (Snipp 2003). Largely absent from this literature are discussions around the complexities of race and racialization, generally considered within the purview of qualitative scholarship. Consequently, many quantitative studies lack conceptual and operational definitions for the measures of race they employ. Moreover, there continue to be huge gaps, especially concerning heterogeneity within the Asian and Latina/o panethnicities, the racialization of nativity, and the experiences of Native American students (Baker, Keller-Wolff, and Wolf-Wendel 2000; Demmert, Grissmer, and Towner 2006; Ladson-Billings and Tate 1995; Lee 2003; Pollock 2004).

Using teacher perceptions as a case in point, this article demonstrates how multidimensional measures of race further our understanding of how race shapes students’ schooling experiences. The multidimensional measure of race I utilize includes fourteen racialized subgroups: white American, white immigrant, Native American, East Asian American, East Asian immigrant, South Asian, Southeast Asian and Pacific Islander American, Southeast Asian and Pacific Islander immigrant, white Latina/o American, white Latina/o immigrant, nonwhite Latina/o American, nonwhite Latina/o immigrant, black American, and black immigrant. Here, multidimensionality vis-à-vis race refers to the complex nature of race and racialization (the process of categorizing and assigning racial meaning or value to physical, cultural, and social status markers) (Barot and Bird 2001; Omi and Winant 2015) and the between- and within-category distinctions that inform racial classification and category-based racial bias (Maddox and Gray 2002; Maddox 2006).1 As such, I do not consider this measure as representative of three distinct social constructs—race as a social hierarchy or classification system based on phenotype and perceived heritage, ethnicity as an identity that emerges out of cultural identification, and immigrant/generational status as an indicator of whether a person or a person’s parent(s) were foreign born (Bashi and McDaniel 1997; Bonilla-Silva 1997; Moya and Marcus 2010; U.S. Census Bureau 2013). Rather, I regard it as indicative of a more complex racialized classification system that accounts for the ways that various panethnic, ethnic, and immigrant status markers are incorporated into the process of racial categorization and ascription (Brown and Jones 2015; Grosfoguel 2004; Saenz and Douglas 2015; Omi and Winant 2015).

The outcomes addressed include teachers’ assessments of positive learning behaviors (Approaches to Learning) and negative acting out behaviors (Externalizing Problem Behaviors) using a nationally representative sample of first grade students. The central goals are to identify racialized subgroup differences in teacher perceptions and to examine the role of student and teacher/classroom level factors for understanding these differences. The secondary goals are to identify some of the challenges associated with measuring race using quantitative education data and to describe one possible strategy for constructing more accurate and valid racial categories. Multidimensional measures of race offer a number of advantages for quantitative scholars interested in educational disparities, including the ability to map patterns of within conventional group variation in students’ schooling experiences and in the reasons for these experiences, to examine how various racial markers mitigate or exacerbate racial gaps, evaluate how racial subgroups are differentially impacted by stereotype content, and identify subgroups that are most likely to be associated with and impacted by racially-motivated stereotypes and biases.

I begin by providing an overview of the literature on race and teacher perceptions, followed by a brief discussion highlighting several limitations related to the way race is currently measured in education research. Next, I describe the data and methods. Here I provide a detailed strategy for constructing a multidimensional measure of race using data on racial, ethnic, and immigration status characteristics of students and their biological parents, as well as a rationale for each category. In subsequent sections, I examine racialized subgroup differences in teacher perceptions. Results address three questions:

Do teacher perceptions of learning and problem behaviors vary across racialized subgroups? If so, in what ways and to what extent?

How much of this variation is a function of teacher/classroom level factors and student background/ academic skills?

To what extent do racialized subgroup variation in teacher perceptions and the explanatory factors for this variation reflect within conventional racial/ethnic group heterogeneity?

BACKGROUND

Race and Teacher Perceptions

Scholars have identified schools as important places to study race relations because they exist within a broader social context that both actively and passively supports racial inequality (Bonilla-Silva 2001; Forman 2004; Lewis 2006). Although some identify schools as equalizers, because of the ways they assist in closing educational gaps between students from various sociodemographic backgrounds (Downey, Hippel, and Broh 2004), many scholars have documented how schools and their agents also reproduce racial hierarchies, often to the detriment of minority students (Condron 2007; Farkas 2003; Ford 1998; Morris 2005; Pianta, Steinberg, and Rollins 1995).

One area where these hierarchies manifest is in teacher perceptions of students, which are associated with a number of important schooling experiences and outcomes, including the quality of teacher-student interaction (Brophy and Good 1970; Davis 2003; Hallinan 2008; Rist 1970; Rosenthal and Jacobson 1968), academic placement and performance (Alvidrez and Weinstein 1999; Faulkner et al. 2014; Hamre and Pianta 2001; McCall, Evahn, and Kratzer 1992) and socioemotional development (Birch and Ladd 1997; Hughes, Cavell, and Wilson 2001; Ladd, Birch, and Buhs 1999; Pianta et al. 1995). While most quantitative studies of race and teacher perceptions have focused on the black-white divide, a number of recent studies have extended this discourse to Asian and Latina/o students (Bates and Glick 2013; Jennings and DiPrete 2010; McGrady and Reynolds 2011; McKown and Weinstein 2008; Ready and Wright 2011). However, the racial comparisons emanating from these studies tend to treat Asian and Latina/o students as homogenous racial/ethnic groups2.

Studies show that black students tend to receive more negative evaluations from teachers than their white counterparts, including for academic ability (McKown and Weinstein 2008; Ready and Wright 2011), as well as for more subjective social behaviors, such as being attentive, impulsive, or disruptive (Downey and Pribesh 2004; McGrady and Reynolds 2013). In contrast, Asian students are regarded as less disruptive and more academically engaged (Bates and Glick 2013; McGrady and Reynolds 2013; Wong 1980). Findings for Latina/o students, however, are mixed. For example, Ready and Wright (2011) find that Latina/o students are rated more poorly than white students, while in other studies, white-Latina/o differences are negligible (Bates and Gick 2013; McGrady and Reynolds 2013).

For perceptions of academic ability, ratings gaps are often attributed to differences in academic performance, with scholars suggesting that much of the racial/ethnic variation in teacher ratings is likely a function of actual differences between racial/ethnic groups (Ferguson 2003; Jussim and Harbor 2005). There are, however, instances when racial/ethnic gaps in teacher ratings are not entirely a product of differences in academic performance. In these cases, scholars also focus on how teachers’ race/ethnicity and the sociodemographic make-up of the classroom context influence racial/ethnic gaps (McKown and Weinstein 2008; Oates 2003; Ready and Wright 2011).

Identifying and understanding racial/ethnic variation in teacher perceptions of social behaviors has proved much more difficult for two reasons: (1) ideas regarding what actions constitute good or bad behavior are often subjective and (2) sociodemographic characteristics of the beholden can influence how individuals perceive otherwise similar actions. This subjectivity was evident in Tyson’s (2003) ethnographic account of one afternoon in a fourth grade classroom, where the teacher, Ms. Clifton, described her students’ behavior with a guest teacher as “embarrassing” even though neither the guest teacher nor Tyson (according to her field notes) noticed anything wrong. Furthermore, Morris (2005) documents how race/ethnicity shape teachers’ responses to students, with the title of his article, “Tuck In That Shirt!” deriving from teachers’ efforts to police certain forms of dress and behavior among black and Latina/o students but not white and Asian students.

One way education scholars have dealt with this subjectivity in quantitative analysis is through race matching, which is when scholars identify potential bias by comparing the extent of racial/ethnic variation in teacher perceptions either between white and nonwhite teachers or between students with same race teachers and those with different race teachers. For example, both Downey and Pribesh (2004) and Bates and Glick (2013) find that the black-white gap in teacher assessments is larger when the teacher is white than when the teacher is nonwhite. Although McGrady and Reynolds (2013) also find some evidence of race matching effects, these effects did not extend to blacks, who faced similarly negative perceptions regardless of their teacher’s race. That Ms. Clifton, who Tyson’s describes as embarrassed by her students’ behavior, was black, but the guest teacher, who saw no issue with their behavior, was white further highlights this point.

To summarize, research points to black students as the recipients of more negative perceptions, and Asian students as the beneficiaries of more positive perceptions, with mixed results for Latina/o students. For academic skill ratings in particular, these differences generally, though not entirely, correspond with actual differences in student performance; however, it is much more difficult to tell the extent to which differences in teacher perceptions reflect actual differences in student behavior. To address this limitation, many scholars have applied race matching techniques, pointing to magnified racial gaps among white teachers relative to their nonwhite counterparts as evidence of racial bias. Although this technique is especially effective at identifying white teacher bias (in relative terms), positioning the perceptions of nonwhite teachers as a reference point could lead researchers to overlook possible bias among nonwhite teachers. This is especially important in cases where white and nonwhite teachers do not differ significantly, because a claim of no bias assumes that the perceptions of nonwhite teachers are immune to racial ideology and stereotypes. Rather than focus on white teacher bias, this study highlights variation in teacher perceptions for students in similar classroom contexts who have similar backgrounds and academic skills.

Measuring Race in Education Research

One of the biggest challenges for scholars interested in educational inequality is the increasing complexity of race and the racial hierarchy (Bonilla-Silva 2004; Lee and Bean 2007). Besides ongoing debates about how to measure race and ethnicity (e.g., Hitlin, Brown, and Elder 2007; Khanna 2010; Lee and Bean 2007; Yancey 2003), scholars are also contending with how to quantitatively account for the increasing racial, ethnic and generational status diversity of nonwhite racial and panethnic groups (Bashi and McDaniel 1997; Hoeffel et al. 2012; Kent 2007; Prewitt 2013; Rong and Preissle 2009; Suarez-Orozco, Suarez-Orozco, and Todorova 2008; U.S. Census Bureau 2007). One example is the most recent in a series of debates over how to measure race on the U.S. Census (Hirschman, Alba, and Farley 2000; Rodriguez 2000; Snipp 2003), where some scholars are applauding the possible inclusion of Hispanic/Latina/o as a racial category on the 2020 Census, while others continue to express grave concerns (Ayala 2013; Ayala and Huet 2013; Gratereaux 2013; Nasser 2013).3

Despite calls for more complex examinations of race in education research, few quantitative scholars have taken on this challenge. As a result, what little we know about the schooling experiences of Latina/o and Asian students are generally presented as singular ethno-racial trends, which overlook important within conventional group heterogenity at the intersections of race, ethnicity, and generational status (Frank, Akresh, and Lu. 2010; Goyette and Xie 1999; Harris, Jamison, and Trujillo 2008; Kao 1995; Lee 1994; Reardon and Galindo 2009; Umana-Taylor and Fine 2001). These issues also relate to research focusing on black students, which by and large, does not differentiate between the experiences of black immigrants and African Americans (O’Connor, Lewis, and Mueller 2007). Moreover, Native American students are generally absent in education research, especially in quantitative studies that employ comparative analysis of various minority groups (Demmert, Grissmer, and Towner 2006).

The association between race and teacher perceptions is not merely a matter of whether different groups possess varying levels of skill or exhibit varying social behaviors. Given that Americans tend to view the world, both consciously and unconsciously, through a racial lens, students’ racialized classifications and the stereotypes and ideologies associated with these classifications also matter for how teachers understand various social behaviors and the extent to which they interpret these behaviors as positive or problematic. Although recent studies have made efforts to include Latina/o and Asian students in this discourse, their use of conventional racial/ethnic categories reflects a broader trend in quantitative education research of treating Asians and Latinas/os as ethno-racially homogenous groups. I expand on previous research by utilizing a multidimensional measure of race to examine racialized subgroup variation in teacher perceptions.

DATA AND METHOD

Data are drawn from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study- Kindergarten Cohort of 1998–99 (ECLS-K), a nationally representative longitudinal study conducted by the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). The ECLS-K is ideal for exploring racial variation in teachers’ ratings of students because it includes surveys from school administrators, teachers, and parents, as well as direct assessments of the child, providing multiple layers of information on children’s educational experiences and academic knowledge. I focus on teacher ratings obtained during the spring of first grade (wave 4). Analyses are limited to first grade students who fall into one of the fourteen racialized subgroups and whose teachers provided ratings for the social behaviors examined, resulting in an analytical sample of approximately 12,850 students.4 Missing data for other independent variables were replaced using multivariate imputations with chained equations (Royston 2005).

Multidimensional Measure of Race

Like most large-scale education datasets, the selection of race-related measures in the ECLS-K are limited. As a results, scholars lack key information on a number of important racialized markers, including skin tone (e.g., Maddox and Gray 2002), external appraisals of race (e.g., Vargas Forthcoming), migration history and citizenship status (Aranda and Vaquera 2015; Ladson-Billings 2004), and religion and religious expression, especially markers related to Islam, Hinduism, or Sikhism post 9/11 (Joshi 2006; Selod and Embrick 2013). These limitations notwithstanding, scholars can still develop more comprehensive and representative measures of race by leveraging variables more commonly found in quantitative education data, such as conventional racial and ethnic labels, ethnic group affiliation, country of origin, and generational status indicators, which in many cases, are available for students and their parents.

I construct a multidimensional measure of race that includes fourteen racialized subgroups: white Americans, white immigrants, Native Americans, East Asian Americans, East Asian Immigrants, South Asians, Southeast Asian and Pacific Islander Americans (from here on referred to as Southeast Asian Americans), Southeast Asian and Pacific Islander immigrants (from here on referred to as Southeast Asian Immigrants), white Latina/o Americans, white Latina/o immigrants, nonwhite Latina/o Americans, nonwhite Latina/o immigrants, black Americans, and black immigrants. Decisions were informed by race-related scholarship, as well as by the methodological opportunities and challenges presented in the ECLS-K. As such, the subgroups presented here are not meant to reflect the ideal or universal multidimensional measure of race, but instead represent one possible alternative for capturing the intracategorical complexity of race (McCall 2005).

Recent discourse on America’s shifting racial hierarchy has identified the increasing number of color lines and the role of nativity as two of the biggest issues (Bonilla-Silva 2004; Frank, Akresh and Lu 2010; Golash-Boza and Darity 2008; Lee and Bean 2004; Lippard and Gallagher 2011; Prewitt 2013). For example, scholars note substantial racial heterogeneity within the Latina/o panethnicity. Bonilla-Silva (2002) posits that while some Latinas/os have become honorary whites, Latinas/os with substantial African heritage are generally perceived as part of a black collective. Other scholars have questioned studies treating Latinas/os as a monolithic racial/ethnic group for masking racial disparities (Reardon and Galindo 2008; Umana-Taylor and Fine 2001). Studies show that Latinas/os with substantial African heritage face greater residential segregation (Denton and Massey 1989), higher infant mortality rates (Williams and Collins 1995), greater wage discrimination (Darity, Hamilton and Dietrich 2002; Frank, Akresh and Lu 2010), and lower levels of education (Gomez 2000) compared to their lighter skin counterparts. Unfortunately, few education datasets include measures of skin color or ascribed race. These limitations are further compounded the large proportion of Latinas/os who opt out of selecting a racial category (Compton et al. 2013; Rodriguez 2000), which is the case for nearly half of the student identified as Latina/o in the ECLS-K.

Furthermore, the measurement of Latinas/os in quantitative research has largely been guided by OMB and Census questions on Hispanic/Latina/o ancestry, which include groups traditionally perceived as Hispanic/Latina/o (e.g., Mexican, Puerto Rican, South American), as well as those from other Spanish cultures or origins who choose to self-identify as Hispanic/Latina/o (Passel and Taylor 2009), but may not be racialized at Latina/o. Most Latina/o students in the ECLS-K had origins in Latin American or the Spanish Caribbean; however, I also noted some with origins through Spain or the Philippines. Although Ocampo (2013) finds that many Filipinos view themselves as more culturally similar to Latinas/os than to other Asian groups, these cultural similarities did not disqualify Filipino students from experiencing the benefits (e.g., receiving preferential treatment from school officials) and the perils (e.g., feeling pressured to excel academically) of the Model Minority stereotype that come with being racialized as Asian.

Because I focus on racialized, as opposed to cultural, ethnicities, from here on, the term Latina/o is used to describe students with Latin American or Spanish Caribbean ancestry, as they are most likely to be perceived as Latina/o by others. Thus, Hispanic/Latina/o students who traced their ancestry through Spain or the Philippines (based on ethnic identity and nativity), were not included in the Latina/o categories. Additionally, because of the difficulties distinguishing among various nonwhite Latina/o subgroups, I focus instead on the white-nonwhite divide. Latina/o students needed to meet two main criteria to be identified as white: (1) they must have been identified as white; and (2) neither they nor their biological parents could have a nonwhite racial/ethnic identity. Remaining Latina/o students were placed in one of the two nonwhite categories.

Scholars have also identified several important divisions within the Asian panethnicity, particularly between Asian Americans and recent waves of immigrants, and between East Asians, Southeast Asians, and Pacific Islanders (Byun and Park 2012; Goyette and Xie 1999; Lee 1994; Kao 1995). The regional divisions noted above capture not only ethnic differences, but also important phenotype variation in skin pigmentation and facial features that may aid in racial classification (Jablonski and Chaplin 2000). To capture some of this heterogeneity, I divide Asian students into three distinct categories based on parents’ report of their child’s ethnic ancestry: East Asia (e.g., China, Japan, Korea), South Asia (e.g., India, Nepal, Pakistan), and Southeast Asia, including the Pacific Islands (e.g., Philippines, Thailand, Fiji, Indonesia). In the few cases where ethnic subgroup data were not provided, students’ ethnic origin was identified based on the country of origin reported for students and their biological mother (and father when available), and on the primary language spoken at home.

Although the white, Native American/ American Indian and black/African American categories have a much longer history in U.S. race measurement (Prewitt 2013), these categories also present some difficulties that deserve attention. As with Latinas/os, I also excluded students with nonwhite racial identities or ancestry from the white, non-Latina/o categories, with one notable exception: white-Native American multiracial students. This decision to group students identified as both white and Native American with other non-Latina/o whites is motivated in part by research suggesting that whites tend to treat Native American identity is a symbolic or optional ethnicity. For example, using Add-Health data, Doyle and Kao (2007) find that the majority of students who identified as white-Native American had white or very light skin tone (compared to the more diverse skin tones of monoracial Native Americans) and shifted to monoracial white identities in later waves. Native American identification among individuals with little or no heritage has also been noted among nonwhites, with some suggesting that many cases are a result of confusion about who is American Indian (Liebler 2004; Snipp 2003). To avoid issues related to symbolic identity and misinterpretation, the Native American category is restricted to students whose only racial/ethnic identity is Native American.

In contrast, the black racial category is operationalized as a collective category that includes any non-Latina/o student with black heritage. This decision acknowledges the staying power of notions such as the one-drop rule—the assumption that anyone with black ancestry or black “blood” is black—which not only shapes how individuals with black ancestry are identified by others, but also influences how they tend to identify themselves (Campbell 2007; Doyle and Kao 2007; Khanna 2010; Qian 2004; Snipp 2010). Thus any non-Latina/o student identified as black or who had at least one biological parent identified as black was placed in a black subgroup.

Lastly, in recognition of the growing import of nativity, I use data on country of birth to identify students either who were born abroad and arrived to the U.S. as children (1.5 generation) or who have at least one parent who was born abroad (second generation).5 Because of the young age of 1.5 generation students, and the fact that both 1.5 and second generation students come from immigrant households, I combine these students into immigrant subgroups, and place students who are third generation and beyond into American subgroups for each racialized subgroup with two exceptions: (1) Native American, which is an exclusively American category and (2) South Asian, because a large majority were 1.5 or second generation.

Teacher Perceptions of Social Behaviors

This study focuses on two measures of teacher perceptions, Externalizing Problem Behaviors and Approaches to Learning, which are based on social rating scales adapted for the ECLS-K. Externalizing Problem Behaviors are negative behaviors that students direct toward their outside environment. This subscale consists of five questions that measure the frequency with which the student argued, fought, got angry, acted impulsively, and disturbed ongoing activities. In contrast, Approaches to Learning are positive behaviors related to how students approach and engage knowledge and skill acquisition. This subscale includes six questions that measure student attentiveness, task persistence, eagerness to learn, learning independence, flexibility, and organization. Both measures range from 1 (low) to 4 (high).6

Student Characteristics

To account for other student background factors, I include indicators for students’ gender, socioeconomic status (constructed by ECLS-K using information on parental education, income, and occupation), and age (measured in months). Since my focus is not on white teacher bias and because of the sheer number, complexity, and sample sizes of subgroups being compared, I do not employ race-matching methods. Instead, I include two measures of students’ academic ability, which are based on teachers’ assessments of various literacy and math skills. The Math and Literacy ARS scores, which were constructed using Rasch Rating Scale models, range from 1 (low) to 5 (high) and have high levels of reliability. The goal of including these ARS ratings is to ensure that subgroup comparisons are made for students with similar backgrounds and academic skill sets (as perceived by the teacher).

Analytic Strategy

I begin by estimating bivariate regression models to examine subgroup differences in teacher ratings. Next, I estimate two-level models with fixed effects at the student-level and random intercepts at the teacher-level. The first set are bivariate multilevel models used to examine the extent to which classroom level characteristics explain these gaps. In the second set of models, I include student-level characteristics. Post-estimation t-tests are used to examine significant differences between subgroup pairs, allowing me to focus on within conventional group variation and within subgroup nativity differences in teacher perceptions. To account for the complex survey structure of ECLS-K data, regression models include survey weights and Huber-White robust standard errors based on clustering at the school-level.7

RESULTS

Externalizing Problem Behaviors

Table 2 present coefficients from single and multilevel regression models of Externalizing Problem Behaviors. Bivariate results from Model 1 show that Native American and black American students are viewed more negatively than white American students (b = −.21, p < .001 and b = −.26, p < .001, respectively), indicating that teachers perceive both Native American and black American students as expressing more problem behaviors on average. Conversely, ratings for East and South Asian students are significantly more positive than white Americans, indicating that on average, teachers perceive East and South Asian students as having less problem behaviors. Although average ratings for Southeast Asian immigrants are also more positive than ratings for white Americans (albeit to a lesser extent than East and South Asian students), for Southeast Asian American students the reverse is true, making Southeast Asian Americans the only Asian subgroup to be rated more poorly than white American students on Externalizing Problem Behaviors.

Table 2.

Single and Multilevel Linear Regression Models of Teacher Ratings of Externalizing Problem Behaviors (ECLS-K: Spring First Grade, 1×1=12,850)

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | |

| White Immigrant | −0.05 | (0.04) | −0.04 | (0.05) | −0.05 | (0.04) |

| Native American | 0.21** | (0.07) | 0.03 | (0.09) | 0.02 | (0.10) |

| East Asian American | −0.14*** | (0.04) | −0.17** | (0.05) | −0.16** | (0.05) |

| East Asian Immigrant | −0.14*** | (0.04) | −0.18** | (0.06) | −0.10+ | (0.06) |

| South Asian | −0.20* | (0.08) | −0.16** | (0.06) | −0.12* | (0.05) |

| Southeast Asian American | 0.12* | (0.06) | 0.02 | (0.10) | 0.01 | (0.10) |

| Southeast Asian Immigrant | −0.09+ | (0.05) | −0.20*** | (0.05) | −0 19*** | (0.05) |

| White Latina/o American | 0.06+ | (0.04) | 0.01 | (0.03) | −0.02 | (0.03) |

| White Latina/o Immigrant | −0.10** | (0.04) | −0.17*** | (0.05) | −0.23*** | (0.05) |

| Nonwhite Latina/o American | 0.05 | (0.04) | 0.00 | (0.05) | −0.05 | (0.04) |

| Nonwhite Latina/o Immigrant | −0.01 | (0.04) | −0.08 | (0.06) | −0.15** | (0.05) |

| Black American | 0.26*** | (0.02) | 0.25*** | (0.04) | 0.18*** | (0.03) |

| Black Immigrant | 0.12 | (0.10) | 0.27 * | (0.13) | 0.21 + | (0.12) |

| Male | 0.25*** | (0.01) | ||||

| SES | −0.05*** | (0.01) | ||||

| Age | 0.00 | (0.00) | ||||

| Literacy ARS | −0.03 | (0.02) | ||||

| Math ARS | −0.13*** | (0.02) | ||||

| Constant | 1.62*** | (0.01) | 1.65*** | (0.01) | 2.20*** | (0.16) |

| Variance Component | ||||||

| Classroom Level (τ00) | 0.49 | (0.01) | 0.47 | (0.01) | ||

Note: All models include survey weights and robust standard errors for clustering at the school level. White American subgroup serves as reference category for MMR.

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p <.001 (two-tailed)

Among white Latina/o students, subgroup differences compared to white Americans follow a similar pattern to that of Southeast Asian students, with white Latina/o immigrant students receiving more positive ratings (less problem behaviors) on average than white American students, while white Latina/o American students are rated more negatively (more problem behaviors). However, I find no significant difference between nonwhite Latina/o students and white American students. For black students, coefficients for both American and immigrant subgroups suggest more negative ratings by teachers relative to white American students. Unlike for black Americans, however, the gap between black immigrant and white American students is statistically insignificant. Post-estimation t-test also show that the average rating for black American students is significantly more negative (more problem behaviors) than for black immigrant students (p < .05).

Next, I examine the extent to which classroom and select student-level factors influence racialized subgroup variation in teacher perceptions, focusing on Model 2, which includes a random intercept to account for variation at the classroom/teacher level, and Model 3, which adds select student level controls. Results reveal variation in the extent to which classroom and student-level factors explain racialized subgroup differences in teacher perceptions of problem behaviors, both generally and within conventional racial/ethnic groups. For example, accounting for classroom/teacher level sorting essentially closes the gap between Native American and white American students, but also opens a significant gap between black immigrant and white American students, thus placing teacher perceptions of black immigrants more in line with that of black Americans.

Among Asian students, accounting for classroom/teacher level sorting results in a small increase for South Asian students and a small decrease in average ratings of Externalizing Problem Behaviors for East Asian students relative to white Americans. For Southeast Asians, however, I find a much larger change. Thus accounting for classroom/teacher level sorting in Model 2 not only closes the gap between Southeast Asian Americans and white Americans, but also places average perceptions of Southeast Asian immigrant students in line with those of East and South Asian subgroups. In contrast, only two Asian subgroups demonstrate substantive changes relative to white Americans when student characteristics are accounted for, with the East Asian immigrant-white American gap closing by 40%, and the South Asian-white American gap by 25%.

Across all three models, I find no significant differences in teacher perceptions of Externalizing Problem Behaviors for Latina/o American students relative to white Americans, but do find evidence of suppression effects for both Latina/o immigrant subgroups. For example, results demonstrate a decrease in perceptions of problem behaviors for white Latina/o immigrants once classroom/teacher sorting effects are accounted for, as well as a decrease for nonwhite Latina/o immigrants and additional decrease for white Latina/o immigrants when student-level characteristics are accounted for. Lastly, results across all three models reveal no significant differences in teachers’ ratings of white immigrant students compared to their white American peers.

Approaches to Learning

Table 3 presents regression coefficients from analyses of teacher ratings of Approaches to Learning. Based on the bivariate results in Model 1, Native American and black American students are once again the most negatively perceived subgroups. Likewise, East Asian and South Asian students once again receive the highest average ratings from teachers. Unlike with perceptions of Externalizing Problem Behaviors, I find no significant differences in the average ratings of Southeast Asian students or white Latina/o students relative to white American students. I do, however, note significant differences in teacher ratings for nonwhite Latina/o students compared to white Americans students, with both nonwhite Latina/o American students and, to lesser extent, nonwhite Latina/o immigrant students being rated more negatively for Approaches to Learning. Results also show that both black immigrant and black American students receive significantly lower ratings for Approaches to Learning relative to white Americans. Once again, I find no significant differences in teachers’ ratings of white immigrant students compared to their white American counterparts.

Table 3.

Single and Multilevel Linear Regression Models of Teacher Ratings of Approaches to Learning (ECLS-K: Spring First Grade, N=12,850)

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | |

| White Immigrant | 0.01 | (0.05) | 0.01 | (0.05) | 0.03 | (0.03) |

| Native American | −0.33*** | (0.07) | −0.28** | (0.09) | −0.16* | (0.07) |

| East Asian American | 0.18** | (0.07) | 0.14* | (0.07) | 0.09+ | (0.05) |

| East Asian Immigrant | 0.23*** | (0.06) | 0.25*** | (0.07) | 0.04 | (0.06) |

| South Asian | 0.21** | (0.08) | 0.17* | (0.08) | 0.11 * | (0.06) |

| Southeast Asian American | −0.10 | (0.08) | −0.02 | (0.09) | 0.00 | (0.07) |

| Southeast Asian Immigrant | 0.09 | (0.05) | 0.22*** | (0.05) | 0.18*** | (0.04) |

| White Latina/o American | −0.04 | (0.04) | −0.07+ | (0.04) | 0.01 | (0.03) |

| White Latina/o Immigrant | −0.06 | (0.05) | 0.07 | (0.07) | 0.22*** | (0.04) |

| Nonwhite Latina/o American | 0.17*** | (0.05) | −0.14** | (0.05) | 0.02 | (0.03) |

| Nonwhite Latina/o Immigrant | −0.09** | (0.04) | −0.07 | (0.05) | 0.16*** | (0.04) |

| Black American | −0.30*** | (0.03) | 0.27*** | (0.04) | −0.08* | (0.03) |

| Black Immigrant | −0.19* | (0.09) | −0.27** | (0.10) | −0.10 | (0.07) |

| Male | −0.25*** | (0.01) | ||||

| SES | 0.03*** | (0.01) | ||||

| Age | 0.01*** | (0.00) | ||||

| Literacy ARS | 0.31*** | (0.02) | ||||

| Math ARS | 0.28*** | (0.02) | ||||

| Constant | 3.09*** | (0.01) | 3.07*** | (0.02) | 0.50** | (0.20) |

| Variance Component | ||||||

| Classroom Level (τ00) | 0.54 | (0.01) | 0.44 | (0.01) | ||

Note: All models include survey weights and robust standard errors for clustering at the school level. White American subgroup serves as reference category for MMR.

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p <.001 (two-tailed)

In Table 3, Models 2 and 3,1 turn again to possible explanations for racialized subgroup variation in teacher perceptions of Approaches to Learning. In this case, accounting for classroom/teacher level factors in Model 2 explains only a small portion of the gaps for Native American and black American students relative to white Americans. Among black immigrants, however, I find a suppression effect that widens the gap between black immigrants and white Americans and closes the gap between black immigrants and black Americans. Although classroom/teacher level sorting also renders the gap between nonwhite Latina/o immigrants and white Americans insignificant, teachers’ more negative perceptions of nonwhite Latina/o American students persists. Accounting for classroom/teacher variation also results in a dramatic increase in teacher perceptions of Southeast Asian immigrant students, placing them on par with East Asian immigrant students.

Model 3 results show that student level characteristics explain a little over 40% of the gap for Native American students, and around two-thirds of the gaps for black American and immigrant students relative to white Americans. But coefficients also suggest that teachers rate some students from these subgroups more poorly than white Americans students, even when they have similar backgrounds and academic abilities. Furthermore, Native American students received the poorest ratings on average, with gaps that remained nearly twice as large as black students. Among Latina/o students, accounting for student level characteristics closes the gaps for nonwhite Latina/o American and white Latina/o Americans relative to white Americans, but also open huge gaps for both Latina/o immigrant subgroups, placing white and nonwhite Latina/o immigrants among the most highly rated subgroups. Additionally, accounting for student characteristics explained the entire gap for East Asian immigrant students, but had much smaller effects on the gaps for other Asian subgroups8.

Before discussing within conventional group variation in teacher perceptions, I review the statistical fit of my multidimensional measure of race based on the analysis presented above. Table 4 presents model fit statistics for models regressing teacher perceptions of Externalizing Problem Behaviors and Approaches to Learning on conventional racial/ethnic categories (e.g., white, Native American, Asian, Latina/o, black) and on multidimensional racialized subgroups. In almost every case, model fit statistics point to my multidimensional measure of race as providing a better model fit than when the conventional measure of race is used.9

Table 4.

Fit Statistics for Single and Multilevel Linear Models of Teacher Perceptions Regressed on Conventional and Multidimensional Measure of Race (ECLS-K: Spring First Grade)

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MMR | CMR | MMR | CMR | MMR | CMR | |

| Externalizing Problem Behaviors | ||||||

| AIC | 24,856 | 24,882 | 3,721,291 | 3,727,475 | 3,397,732 | 3,405,722 |

| BIC | 24,960 | 24,920 | 3,721,411 | 3,727,527 | 3,397,888 | 3,405,811 |

| Approaches to Learning | ||||||

| AIC | 27,125 | 27,134 | 4,152,532 | 4,158,452 | 2,265,538 | 2,279,919 |

| BIC | 27,229 | 27,171 | 4,152,652 | 4,158,504 | 2,265,694 | 2,280,008 |

Note: Based on analysis of unimputed data (N = 12,600).

Within Conventional Group Variation

Lastly, I examine within conventional group variation and differential effects of generational status, net student background and academic skills and teacher/classroom characteristics. Based on Model 3 results and post estimation t-tests (see Appendix A and B), several within racial/ethnic group hierarchies emerge. For teacher perceptions of Externalizing Problem Behaviors, Southeast Asian students are the most highly rated Asian subgroup, followed by East Asian American students, and then South Asian students. Although East Asian immigrants have a slightly higher average rating than Southeast Asian Americans, the difference is not statistically significant. Southeast Asian immigrant students are the only Asian subgroup with significantly higher ratings for Approaches to Learning compared to other Asian subgroups. I also find no significant differences between the two Latina/o American subgroups for either Externalizing Problem Behaviors or Approaches to Learning; however, Latina/o American students are rated more negatively by teachers than Latina/o immigrants, with white Latina/o immigrants receiving the highest ratings.

Appendix A.

Racialized Subgroup Differences in Teacher Perceptions of Externalizing Problem Behaviors (ECLS-K: Spring First Grade, N=12,850)

| White American |

White Immigrant |

Native American |

East Asian American |

East Asian Immigrant |

South Asian |

Southeast Asian American |

Southeast Asian Immigrant |

White Latina/o American |

White Latina/o Immigrant |

Nonwhite Latina/o American |

Nonwhite Latina/o Immigrant |

Black American |

Black Immigrant |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White American | N.S. | N.S. | − | − | − | N.S. | − | N.S. | − | N.S. | − | + | + | |

| White Immigrant | N.S. | N.S. | − | − | − | N.S. | − | N.S. | − | N.S. | − | + | + | |

| Native American | N.S. | − | − | N.S. | − | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | − | N.S. | − | + | N.S. | |

| East Asian American | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | |

| East Asian Immigrant | + | + | N.S. | − | − | N.S. | − | N.S. | − | N.S. | − | + | + | |

| South Asian | + | + | + | − | + | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | |

| Southeast Asian American | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | − | N.S. | − | − | N.S. | − | N.S. | − | + | N.S. | |

| Southeast Asian Immigrant | + | + | N.S. | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | |

| White Latina/o American | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | − | N.S. | − | N.S. | − | − | N.S. | − | + | N.S. | |

| White Latina/o Immigrant | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Nonwhite Latina/o American | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | − | N.S. | − | N.S. | − | N.S. | − | − | + | + | |

| Nonwhite Latina/o Immigrant | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | |

| Black American | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | |

| Black Immigrant | − | − | N.S. | − | − | − | N.S. | − | N.S. | − | − | − | 1 |

Note: A plus sign (+) denotes that the row subgroup is rated more positively (less problem behaviors) than the column subgroup, and a minus sign (−) denotes the reverse. Differences in average ratings stem from multilevel model with a random component at the classroom/teacher level and controls for gender, socioeconomic status, age, and teacher ratings of students’ literacy and math skills. Only differences atp<.10are presented.

Appendix B.

Racialized Subgroup Differences in Teacher Perceptions of Approaches to Learning (ECLS-K: Spring First Grade, N=12,850)

| White American |

White Immigrant |

Native American |

East Asian American |

East Asian Immigrant |

South Asian |

Southeast Asian American |

Southeast Asian Immigrant |

White Latina/o American |

White Latina/o Immigrant |

Nonwhite Latina/o American |

Nonwhite Latina/o Immigrant |

Black American |

Black Immigrant |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White American | N.S. | + | − | N.S. | − | N.S. | − | N.S. | − | N.S. | − | + | N.S. | |

| White Immigrant | N.S. | + | N.S. | N.S. | − | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | − | N.S. | − | + | N.S. | |

| Native American | − | − | − | − | − | N.S. | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| East | + | N.S. | + | N.S. | − | N.S. | − | N.S. | − | N.S. | − | + | + | |

| East Asian Immigrant | N.S. | N.S. | + | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | − | N.S. | − | N.S. | − | + | N.S. | |

| South Asian | + | + | + | + | N.S. | N.S. | − | N.S. | − | N.S. | − | + | + | |

| Southeast Asian American | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | − | N.S. | − | N.S. | − | + | N.S. | |

| Southeast Asian Immigrant | + | N.S. | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | + | + | |

| White Latina/o American | N.S. | N.S. | + | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | − | − | N.S. | − | + | N.S. | |

| White Latina/o Immigrant | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Nonwhite Latina/o American | N.S. | N.S. | + | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | − | N.S. | − | − | + | N.S. | |

| Nonwhite Latina/o Immigrant | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | |

| Black American | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | |

| Black Immigrant | N.S. | N.S. | + | − | N.S. | − | N.S. | − | N.S. | − | N.S. | − | − |

Note: A plus sign (+) denotes that the row subgroup is rated more positively than the column subgroup, and a minus sign (−) denotes the reverse. Differences in average ratings stem from multilevel model with a random component at the classroom/teacher level and controls for gender, socioeconomic status, age, and teacher ratings of students’ literacy and math skills. Only differences at p <.10are presented.

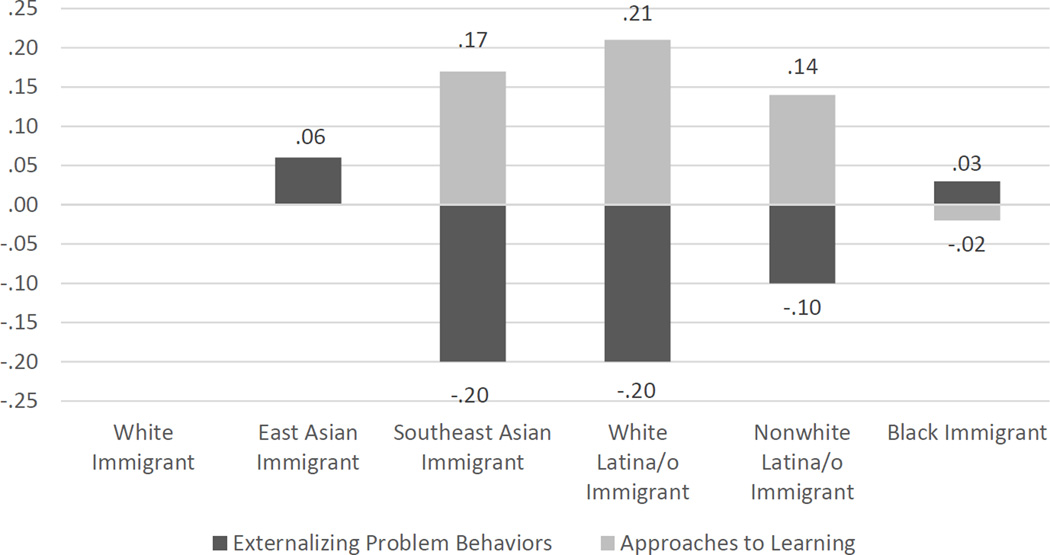

Figure 1 presents significant generational status differences (at p < . 10) for both Externalizing Problem Behaviors and Approaches to Learning. The largest generational status differences in teacher perceptions occurred within the white Latina/o and Southeast Asian subgroups, with 1.5 and second generation students receiving significantly more positive ratings than their non-immigrant peers. Although I also found fairly large generational status differences in teacher perceptions of nonwhite Latina/o students, these differences were between 33 and 50% smaller than the differences for white Latina/o students. In contrast, I find no significant differences in teacher perceptions of white American and white immigrant students. Additionally, although I do find some significant generational status differences among black and East Asian students, these differences were fairly small, substantively speaking, when compared to differences for Southeast Asian and Latina/o students and were in the reverse direction such that non-immigrant students received more positive ratings.

Figure 1.

Generational Status Differences in Teacher Perceptions (ECLS-K: Spring First Grade, N=12,850)

Note: Bars represent difference between 1.5 and second generation students (immigrant subgroup) and students third generation and beyond (American subgroup), with American students serving as the baseline in each subgroup comparison. Differences in average ratings stem from multilevel models with a random component at the classroom/teacher level and controls for gender, socioeconomic status, age, and teacher ratings of students’ literacy and math skills (Table 2, Model 3 and Table 3, Model 3). All differences are significant at p < .10 (two tailed).

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

There is a dearth of quantitative research that incorporates the complexities of race and racialization into examinations of educational inequality. While recent studies on teacher perceptions have expanded beyond the white-black divide, most primarily depend on conventional measures of race, which cast Asians and Latinas/os as racial monoliths. Absent from this discourse are considerations of racial and ethnic heterogeneity within the Asian and Latina/o panethnicities, the racialization of nativity, and the experiences of Native American students. The aim of this research was twofold: (1) to present a possible strategy for constructing multidimensional measures of race using quantitative education data and (2) to use this multidimensional measure of race to examine racialized subgroup variation in teacher perceptions. By utilizing a multidimensional measure of race that accounts for the racialization of ethnicity and generational status and includes Native American students, this study offers a more detailed and inclusive picture of the relationship between race and teacher perceptions. In addition, I uncover within conventional groups heterogeneity in how teachers rate student behavior and in the factors that explain these differences.

Results from this study advance our understanding race and teacher perceptions in several ways. First, I find that not all Asian students are equal beneficiaries of teachers’ positive perceptions. Specifically, East and South Asian students received significantly higher ratings for Externalizing Problem Behaviors and Approaches to Learning relative to white American students, whereas Southeast Asian students were rated substantially lower. Just as interesting is the huge improvement in teacher ratings I find for Southeast Asian immigrants, but not their American counterparts, once I adjust for classroom/teacher level factors, which results in Southeast Asian immigrant students being more positively perceived than similarly situated peers from other Asian subgroups.

Second, results show that within group differences in teacher ratings of Latina/o students are defined by both generational status and the white-nonwhite divide, although patterns varied depending on the behavior examined. Teachers rated white Latina/o immigrants, but no other Latina/o subgroup, significantly higher than white Americans for Externalizing Problem Behaviors. In contrast, for Approaches to Learning, nonwhite Latina/o students received significantly more negative ratings, with the lowest average ratings directed at students third generation and beyond. Subsequent models, however, identify nativity as the primary point of division among Latina/o students. Specifically, white Latina/o immigrants, and less so nonwhite Latina/o immigrants, are rated more positively than similarly positioned white and Latina/o American students. Among Latina/o immigrants, however, race also served as a dividing line, with white Latina/o immigrants garnering significantly more positive perceptions than their nonwhite Latina/o immigrant peers.

Third, in contrast to students from Asian and Latina/o subgroups, I found no evidence of an immigrant status boost among black students. In particular, results demonstrated how classroom/teacher level placements not only promoted more positive perceptions of black immigrants relative to black Americans, but also gave the appearance that black immigrants received ratings that were statistically indistinguishable from white American students. After accounting for classroom level variation, however, the patterns for black immigrant and black American students became nearly indistinguishable, such that both groups were now rated more poorly than their white American peers. I also found no significant nativity differences among white students. Considering the degree of immigrant status variation in teacher perceptions for Asian and Latina/o students, these results were especially striking.

My last key findings relate to teacher perceptions of Native American students. In bivariate models, teachers’ average ratings of Native Americans mirrored ratings for black Americans. While negative ratings of Externalizing Problem Behaviors for Native Americans relative to white Americans are primarily a function of classroom/teacher level factors, the same is not true for ratings received by Native American students for Approaches to Learning. Notably, Native American students end up with the lowest average ratings for Approaches to Learning once I account for student background and academic skills.

Despite its many benefits, this study is not without limitations. The first limitation is related to the difficulties of constructing valid multidimensional measures of race using large-scale datasets. The lack of data on phenotype (e.g., skin color) and ascribed racial classification (e.g., respondent’s race as perceived by others) in large-scale education datasets limit the extent to which scholars can construct racialized subgroups that accurately reflect racial categorization in everyday interaction. Because Latinas/os are more likely to select racial identities that conflict with external appraisals, to report Hispanic/Latina/o, their ethnicity (e.g., Mexican, Puerto Rican, Peruvian), or other as their race, and to opt out of the race question altogether, having other measures of race is especially important for identifying heterogeneity among Latina/o youth. These concerns also extend to other racialized cultural markers. For example, despite the considerable upsurge in the racialization of religion post 9/11, especially of Islam and other religions perceived as synonymous with Islam (e.g., Hinduism, Sikhism), the lack of detailed measures of religion and religious expression limit the extent to which quantitative education scholars can examine these issues. Moreover, concerns about subgroup sample sizes also limit the number, scope, and complexity of racialized subgroups.

Another limitation is related to the difficulties accounting for students’ actual behavior. Studies on perceptions of academic ability often include academic assessment measures, such as test scores, to examine differences in teacher ratings across students with similar skill sets. Because perceptions of social behaviors lack equivalent proxies, it is difficult to flesh out the extent to which differences in teacher perceptions are rooted in teacher bias, as opposed to actual differences in student behavior. One consequence of this limitation is that I cannot say with certainty that remaining subgroup differences are a result of inaccurate or biased assessments.

Despite its limitations, this study clearly shows the value of using a multidimensional measure of race that incorporates markers of race, ethnicity, and immigrant status to examine the role of race and racialization in students’ schooling experiences. By focusing on racialized subgroup comparisons, I was able to identify important points of divergence both within and between conventional racial/ethnic groups. I was also able to document the persistence of certain racialized subgroup gaps, and the emergence of others when comparing students with similar backgrounds and academic skill sets. These patterns are largely consistent with the qualitative studies on race and teacher perceptions, including accounts of how teachers’ perceptions of and reactions to seemingly similar situations and behaviors vary depending on the race of the student (see for example, Lee 1995; Morris 2005; Yates and Marcelo 2014). Moreover, results for teacher perceptions of Approaches to Learning extends Nunn’s (2014) research on how social context shapes teachers’ perceptions of what matters for academic success by demonstrating how teachers’ assessments of how students with similar math and literacy skills approach learning also vary across complex combinations of race, ethnicity, and immigrant status. These findings offer one example of how multidimensional measures of race can help to further untangle the various ways that race and racialization influence how educators make sense of student behavior and performance.

As a reminder, these differences are for students in the first grade. Yet, even at this early age, racial differences in teacher perceptions appear to reinforce dominant racial ideology, which may in turn fuel disparities in access to educational resources, academic placement decisions, and student discipline. Because teacher perceptions are more consequential for the educational experiences and outcomes of blacks (Faulkner et al. 2014; Oates 2003), more negative perceptions directed toward black students (relative to white American students with similar social circumstances and academic skills sets) are likely to exacerbate black-white achievement gaps (McKnown and Weinstein 2008). These findings may also help scholars understand ethnic subgroup differences in attitudes toward schooling, academic performance, and persistence among Asian students (Goyette and Xie 1999; Kao 1995; Kao and Thompson 2003; Ngo and Lee 2007; Lee 2012; Lee 1994) and generational status differences in academic growth among Latinas/os (Reardon and Galindo 2009).

This study also reveals some of the limitations scholars face when using broader racial/ethnic categories. The recent growth of immigrant and minority populations has increased the diversity among American children (Kent 2007; Rong and Preissle 2009; U.S. Census Bureau 2007). These demographic shifts have altered American race relations, particularly in relation to how Americans view race and the racial hierarchy (Bonilla-Silva 2004). Certainly, there are times when data limitations constrain the level of racial complexity scholars can achieve. There are also instances when the black-white dichotomy and broader racial/ethnic groups are adequate for understanding inequality. However, this should not preclude scholars from employing the same theoretical and methodological rigor for measures of race that they do for other measures commonly used in education research. In this case, employing a multidimensional measure to capture variation in teachers’ perceptions not only demonstrates the persistence of racial inequality in American schools but also reveals within racial/ethnic group variation in teachers’ perceptions. Incorporating multidimensional measure of race into examinations on educational inequality is one way scholars can improve the validity and generalizability of their research findings in the context of a multiethnic, multiracial, multigenerational 21st century America.

Table 1.

Distribution of Subgroups from Multidimensional Measure of Race (ECLS-K 1998–99: First Grade, 1×1=12,850)

|

Conventional Racial/Ethnic Group Racialized Subgroup |

Percent |

|---|---|

| White | |

| White American | 57.7 |

| White Immigrant | 2.2 |

| Native American | 1.7 |

| Asian | |

| East Asian American | 1.0 |

| East Asian Immigrant | 1.4 |

| South Asian | .9 |

| Southeast Asian/ Pacific Islander American | 1.3 |

| Southeast Asian/ Pacific Islander Immigrant | 2.6 |

| Hispanic/Latina/o | |

| White Latina/o American | 4.4 |

| White Latina/o Immigrant | 3.4 |

| Nonwhite Latina/o American | 4.1 |

| Nonwhite Latina/o Immigrant | 4.7 |

| Black | |

| Black American | 13.5 |

| Black Immigrant | 1.1 |

Note: Immigrant subgroups restricted to 1.5 and second generation students. American subgroups restricted to students third generation and beyond.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Brian Powell, Sibyl Kleiner, Abigail Sewell, Matthew Hughey, Rebecca Schewe, and David Pedulla for their constructive feedback on previous drafts of this manuscript.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported by a Ford Foundation Fellowship through The National Academies; by a grant from the American Educational Research Association, which receives funds for its grants program from the National Science Foundation under NSF Grant DRL-0941014; and by grant 5 R24 HD042849, Population Research Center, awarded to the Population Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Opinions reflect those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the granting agencies.

Footnotes

The concept of multidimensionality has been used by scholars to represent the different ways of measuring race (racial identity, self-classifications, external appraisals) (e.g., Lopez 2013; Vargas 2015), the various components or factors encompassed in racial/ethnic identity (e.g., Phinney and Ong 2007), and variation in the influence of race on the pathway to an outcome (e.g., Saporito and Lareau 1999).

Bates and Glick (2013) make an effort to account for within pan-ethnic differences in their measures, namely by including black Latinas/os in a collective black category and creating a “Hispanic white” category for the remaining Latina/o students. It is not clear, however, whether Latina/o students are categorized as “Hispanic white” because they identify as white or because they do not identify as black.

The Alternative Questionnaire Experiment (AQE) report details some of the changes to the race question being proposed for the 2020 Census (Compton, Bentley, Ennis, and Rastogi 2013). A memorandum submitted to the U.S. Census Bureau on July 19, 2013, by the Sociology Working Group on Race and Hispanic Origin Question Revisions for Census 2020 describes some of the difficulties scholars of race and ethnicity faced that made it impossible to come to a consensus regarding the types of race question(s) the Census should use (see http://healthpolicy.unm.edu/sites/default/files/SociologyRace2020CensusWorkingGroup%207%2019%2013%2012pmEST.pdf).

Due to NCES regulations for restricted-use data, all sample sizes are rounded to the nearest tenth.

The term “1.5 generation” describes individuals who were born abroad but arrived to the U.S. as children (usually before age 14) (Rumbaut and Ima 1988).

Although scholars often use teachers’ ratings of Externalizing Problem Behaviors and Approaches to Learning as proxies of students’ actual behavior, these measures may also reflect some level of racialized sense-making in teachers’ observations and judgments of students’ behaviors.

This study focuses on overall patterns of subgroup differences in teacher perceptions. Although additional analyses show that these gaps hold when teacher and school characteristics are included as model controls, because these findings are based on average differences at the national level, it is possible that these racial gaps could be stronger or weaker depending on the region, whether it is an urban, suburban, or rural setting, or the racial composition of the school.

Fit statistics were estimated for models estimated using unimputed data (N = 12,600).

Lower AIC and BIC suggest improved model fit. For the bivariate models (Models 1), the BIC points to the models with the conventional measures of race as providing a better model fit. This is likely because the BIC tends to prefer models with fewer covariates, whereas the AIC favors models with more covariates. Once I shift to multilevel models, both the AIC and BIC suggest that the multidimensional measure of race improves model fit.

REFERENCES

- Alvidrez Jennifer, Weinstein Rhona S. Early Teacher Perceptions and Later Student Academic Achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1999;91(4):731–746. [Google Scholar]

- Aranda Elizabeth, Vaquera Elizabeth. Racism, the Immigration Enforcement Regime, and the Implications for Racial Inequality in the Lives of Undocumented Young Adults. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity. 2015;1:88–104. [Google Scholar]

- Ayala Elaine. Census Bureau Studies to Classify ‘Hispanics’ as a Race. [September 25, 2014];San Antonio Express. 2013 Feb 3; Retrieved( http://www.mysanantonio.com/news/local_news/article/Census-Bureau-studies-idea-to-classify-4247921.php.

- Ayala Elaine, Huet Ellen. Hispanic May Be a Race on 2020 Census. [September 25, 2014];SF Gate. 2013 Feb 4; Retrieved( http://www.sfgate.com/nation/article/Hispanic-may-be-a-race-on-2020-census-4250866.php#page-2).

- Baker Bruce D, Keller-Wolff Christine, Wolf-Wendel Lisa. Two Steps Forward, One Step Back: Race/Ethnicity and Student Achievement in Education Policy Research. Educational Policy. 2000;14(4):511–529. [Google Scholar]

- Barot Rohit, Bird John. Racialization: The Genealogy and Critique of a Concept. Ethnic and Racial Studies. 2001;24(4):601–618. doi: 10.1080/01419870120049806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashi Vilna, McDaniel Antonio. A Theory of Immigration and Racial Stratification. Journal of Black Studies. 1997;27(5):668–682. [Google Scholar]

- Bates Littisha A, Glick Jennifer E. Does It Matter if Teachers and Schools Match the Student? Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Problem Behaviors. Social Science Research. 2013;42(5):1180–1190. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch Sondra H, Ladd Gary W. The Teacher-Child Relationship and Children’s Early School Adjustment. Journal of School Psychology. 1997;35(1):61–79. [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla-Silva Eduardo. Rethinking Racism: Toward a Structural Interpretation. American Sociological Review. 1997;62(3):465–480. [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla-Silva Eduardo. White Supremacy and Racism in the Post-Civil Rights Era. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla-Silva Eduardo. We Are All Americans! The Latina/o Americanization of Racial Stratification in the USA. Race and Society. 2002;5:3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla-Silva Eduardo. “From Bi-Racial to Tri-Racial: Towards a New System of Racial Stratification in the USA. Ethnic and Racial Studies. 2004;27(6):931–950. [Google Scholar]

- Brophy Jere E, Good Thomas L. Teachers’ Communication of Differential Expectations for Children’s Classroom Performance: Some Behavioral Data. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1970;61(5):365–374. [Google Scholar]

- Brown Hana, Jones Jennifer A. Rethinking Panethnicity and the Race-immigration Divide: An Ethnoracialization Model of Group Formation. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity. 2015;1:181–191. [Google Scholar]

- Byun Soo-yong, Park Hyunjoon. The Academic Success of East Asian American Youth: The Role of Shadow Education. Sociology of Education. 2012;85(1):40–60. doi: 10.1177/0038040711417009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell Mary E. Thinking Outside the (Black) Box: Measuring Black and Multiracial Identification on Surveys. Social Science Research. 2007;36(3):921–944. [Google Scholar]

- Compton Elizabeth, Bentley Michael, Ennis Sharon, Rastogi. Sonya. 201) Census Race and Hispanic Origin Alternative Questionnaire Experiment. [September 25, 2014];US Census Bureau. Retrieved( http://www.census.gov/2010census/pdf/2010_Census_Race_HO_AQE.pdf).

- Condron Dennis J. Stratification and Educational Sorting: Explaining Ascriptive Inequalities in Early Childhood Reading Group Placement. Social Problems. 2007;54(1):139–160. [Google Scholar]

- Darity William, Jr, Hamilton Darrick, Dietrich Jason. Passing on Blackness: Latinas/os, Race, and Earnings in the USA. Applied Economics Letters. 2002;9(13):847–853. [Google Scholar]

- Davis Heather A. Conceptualizing the Role and Influence of Student-Teacher Relationships on Children’s Social and Cognitive Development. Educational Psychologist. 2003;38(40):207–234. [Google Scholar]

- Demmert William G, Grissmer David, Towner John. A Review and Analysis of the Research on Native American Students. Journal of American Indian Education. 2006;45(3):5–23. [Google Scholar]

- Downey Douglas B, Von Hippel Paul T, Broh Beckett A. Are Schools the Great Equalizer? Cognitive Inequality during the Summer Months and the School Year. American Sociological Review. 2004;69(5):613–635. [Google Scholar]

- Downey Douglas B, Pribesh Shana. When Race Matters: Teachers’ Evaluations of Students’ Classroom Behavior. Sociology of Education. 2004;77(4):267–282. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle Jamie Mihoko, Kao Grace. Are Racial Identities of Multiracial Stable? Changing Self-Identification Among Single and Multiple Race Individuals. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2007;70(4):405–423. doi: 10.1177/019027250707000409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farkas George. Racial Disparities and Discrimination in Education: What Do We Know, How Do We Know It, and What Do We Need To Know? The Teachers College Record. 2003;105(6):1119–1146. [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner Valerie N, Stiff Lee V, Marshall Patricia L, Nietfeld John, Crossland Cathy L. Race and Teacher Evaluations as Predictors of Algebra Placement. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education. 2014;45(3):288–311. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson Ronald F. Teachers’ Perceptions and Expectations and the Black-White Test Score Gap. Urban Education. 2003;38(4):460–507. [Google Scholar]

- Ford Donna Y. The Underrepresentation of Minority Students in Gifted Education: Problems and Promises in Recruitment and Retention. The Journal of Special Education. 1998;32(1):4–14. [Google Scholar]

- Forman Tyrone A. Color-Blind Racism and Racial Indifference: The Role of Racial Apathy in Facilitating Enduring Inequalities. In: Krysan M, Lewis A, editors. The Changing Terrain of Race and Ethnicity. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2004. pp. 43–66. [Google Scholar]

- Frank Reanne, Akresh liana R, Lu Bo. Latina/o Immigrants and the US Racial Order How and Where Do They Fit In? American Sociological Review. 2010;75(3):378–401. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez Christina. The Continual Significance of Skin Color: An Exploratory Study of Latinas/os in the Northeast. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2000;22(1):94–103. [Google Scholar]

- Goyette Kim, Xie Yu. Educational Expectations of Asian American Youths: Determinants and Ethnic Differences. Sociology of Education. 1999;72(1):22–36. [Google Scholar]

- Gratereaux Alexandra J. ldquo;Latinas/os a Race? Census, Groups Try to Figure Out How to Classify Hispanics.”. [September 25, 2014];Fox News Latina/o. 2013 Jan 11; Retrieved on( http://latina/o.foxnews.com/latina/o/news/2013/01/ll/latinas/os-race-census-groups-try-to-figure-out-how-to-classify-hispanics/).

- Grosfoguel Raman. Race and Ethnicity or Racialized Ethnicities? Identities within Global Coloniality. Ethnicities. 2004;4(3):315–336. [Google Scholar]

- Hallinan Maureen T. Teacher Influences on Students’ Attachment to School. Sociology of Education. 2008;81(3):271–283. [Google Scholar]

- Hamre Bridget K, Pianta Robert C. Early Teacher-Child Relationships and the Trajectory of Children’s School Outcomes through Eighth Grade. Child Development. 2001;72(2):625–638. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris Angel L, Jamison Kenneth M, Trujillo Monica H. Disparities in the Educational Success of Immigrants: An Assessment of the Immigrant Effect for Asians and Latinas/os. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2008;620(1):90–114. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschman Charles, Alba Richard, Farley Reynolds. The Meaning and Measurement of Race in the US Census: Glimpses into the Future. Demography. 2000;37(3):381–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hitlin Steve, Brown JScott, Elder Glen H., Jr Measuring Latinas/os: Racial vs. Ethnic Classification and Self-Understandings. Social Forces. 2007;86(2):587–612. [Google Scholar]

- Hoeffel Elizabeth M, Rastogi Sonya, Kim Myoung Ouk, Shahid Hasan. [August 28, 2012];The Asian Population: 2010. U.S. Census Bureau. 2012 Retrieved( http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-11.pdf)

- Hughes Jan N, Cavell Timothy A, Wilson Victor. Further Support for the Developmental Significance of the Quality of the Teacher-Student Relationship. Journal of School Psychology. 2001;39(4):289–301. [Google Scholar]

- Jablonski Nina G, Chaplin George. The Evolution of Human Skin Coloration. Journal of Human Evolution. 39(1):57–106. doi: 10.1006/jhev.2000.0403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings Jennifer L, DiPrete Thomas A. Teacher Effects on Social and Behavioral Skills in Early Elementary School. Sociology of Education. 2010;83(2):135–159. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi Khyati Y. The Racialization of Hinduism, Islam, and Sikhism in the United States. Equity and Excellence in Education. 2006;39:211–226. [Google Scholar]

- Kao Grace. Asian Americans as Model Minorities? A Look at Their Academic Performance. American Journal of Education. 1995;103(2):121–159. [Google Scholar]

- Kao Grace, Thompson Jennifer S. Racial and Ethnic Stratification in Educational Achievement and Attainment. Annual Review of Sociology. 2003;29:417–442. [Google Scholar]

- Kent Mary M. Immigration and America’s black population. [September 25, 2014];Population Bulletin. 2007 62(4) Population Reference Bureau. Retrieved on( http://www.prb.org/pdf07/62.4immigration.pdf). [Google Scholar]

- Khanna Nikki. “If You’re Half Black, You’re Just Black’: Reflected Appraisals and the Persistence of the One-Drop Rule. The Sociological Quarterly. 2010;51(1):96–121. [Google Scholar]

- Ladd Gary W, Birch Sondra H, Buhs Eric S. Children’s Social and Scholastic Lives in Kindergarten: Related Spheres of Influence? Child Development. 1999;70(6):1373–1400. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladson-Billings Gloria. Culture versus Citizenship: The Challenge of Racialized Citizenship in the United States. In: Banks JA, editor. Diversity and Citizenship Education: Global Perspectives. San Francisco: CA: Jossey-Bass; 2004. pp. 99–126. [Google Scholar]

- Ladson-Billings Gloria, Tate IV William F. Toward a Critical Race Theory of Education. Teachers College Record. 1995;97(1):47–68. [Google Scholar]

- Lee Carol D. Why We Need to Re-Think Race and Ethnicity in Educational Research. Educational Researcher. 2003;32(5):3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Lee Jennifer. Asian American Exceptionalism and ‘Stereotype Promise. [May 4, 2012];The Society Pages. 2012 Retrieved( http://thesocietypages.org/papers/asian-american-exceptionalism-and-stereotype-promise/). [Google Scholar]

- Lee Jennifer, Bean Frank D. Reinventing the Color Line: Immigration and America’s New Racial/Ethnic Divide. Social Forces. 2007;86(2):561–586. [Google Scholar]

- Lee Stacy J. Behind the Model-Minority Stereotype: Voices of High- and Low-Achieving Asian American Students. Anthropology and Education Quarterly. 1994;25(4):413–429. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis Amanda E. Whiteness in Schools: How Race Shapes Blacks’ Opportunities. In: Horvat EM, O’Connor C, editors. Beyond Acting White: Reframing the Debate on Black Student Achievement. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, Inc; 2006. pp. 176–200. [Google Scholar]

- Liebler Carolyn A. American Indian Ethnic Identity: Tribal Nonresponse in the 1990 Census. Social Science Quarterly. 2004;85(2):310–323. [Google Scholar]

- Lippard Cameron D, Gallagher Charles A. Being Brown in Dixie: Race, Ethnicity, andLatina/o Immigration in the New South. Boulder, CO: First Forum Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez Nancy. Contextualizing Lived Race-Gender and the Racialized-Gendered Social Determinants of Health. In: Gomez LE, Lopez N, editors. inMapping ‘Race”: Critical Approaches to Health Disparities Research. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 2013. pp. 179–212. [Google Scholar]

- Maddox Keith B. Rethinking Racial Stereotyping, Prejudice, and Discrimination. [January 28, 2015];Psychological Science Agenda, A Publication of the American Psychological Association Science Directorate. 2006 29(1) Retrieved http://www.apa.org/science/about/psa/2006/04/maddox.aspx). [Google Scholar]

- Maddox Keith B, Gray Stephanie A. Cognitive Representations of Black Americans: Reexploring the Role of Skin Tone. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2002;28(2):250–259. [Google Scholar]

- McCall Leslie. The Complexity of Intersectionality. Signs. 2005;30(3):1771–1800. [Google Scholar]

- McCall Robert. B, Evahn. Cynthia, Kratzer Lynn. High School Underachievers: What Do They Achieve as Adults? Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- McGrady Patrick B, Reynolds John R. “Racial Mismatch in the classroom: Beyond Black-white differences. Sociology of Education. 2012;86:3–17. [Google Scholar]

- McKown Clark, Weinstein andRhona S. Teacher Expectations, Classroom Context, and the Achievement Gap. Journal of School Psychology. 2008;46(3):235–261. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris Edward W. Tuck In That Shirt!” Race, Class, Gender, and Discipline in an Urban School. Sociological Perspectives. 2005;48(1):25–48. [Google Scholar]

- Moya Paula ML, Markus Hazel Rose. Doing Race: An Introduction. In: Markus HR, Moya PML, editors. Doing Race: 21 Essays for the 21st Century. New York: W.W. Norton and Company, Inc; 2010. pp. 1–102. [Google Scholar]

- Nasser Haya E. Census Rethinks Hispanic on Questionnaire. [September 25, 2014];USA Today. 2013 Jan 4; Retrieved on http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2013/01/03/hispanics-may-be-added-to-census-race-category/1808087/