Abstract

Focusing on adults from the Los Angeles Family and Neighborhood Survey, we investigated whether mental health was a mediator in the association between obesity (body mass index ≥ 30 kg/m2) and participation in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). The analyses included 1776 SNAP participants and eligible nonparticipants. SNAP participants had higher odds of obesity (odds ratio [OR] =2.6; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.52–4.36) and of reporting a mental health problem (OR = 3.8; 95% CI, 1.68–8.44) than eligible nonparticipants; however, mental health was not a mediator in the association between SNAP participation and obesity. We recommend changes in SNAP to promote healthier food habits among participants and reduce the stress associated with participation.

Keywords: SNAP, mental health, obesity, Los Angeles County

INTRODUCTION

Participation in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) has been associated with obesity.1,2 SNAP is a means-tested entitlement program that provides financial assistance for food purchases to low-income households; it is the largest food assistance program in the United States, serving ~14% of all Americans.3 Given the high costs associated with obesity4 and the large reach of SNAP, it is important to understand the role that SNAP may play in obesity development among the poor.

It has been suggested that SNAP participation may negatively affect mental health and that poor mental health may lead to obesity due to disrupted eating patterns and/or reduced physical activity.5 The stress of needing SNAP benefits and not being able to independently support one’s family may detrimentally impact mental health.6,7 SNAP participation has been associated with poorer mental health among the food insufficient6 and receiving means-tested benefits (which includes SNAP) has been associated with increased depression among unemployed women.8 Previous research also shows that ~40% of SNAP participants report feelings of embarrassment or stigma for having to use SNAP benefits or having other people find out that they use SNAP benefits9; however, the adoption of the Electronic Benefit Transfer system seems to have reduced stigma levels.10,11

The association between poor mental health and obesity is clearly established.12,13 However, questions regarding causality and the role of mental health in mediating the relationship between SNAP participation and obesity remain. For example, the relationship between poor mental health and obesity could be bidirectional.14,15 In addition, having poor mental health may impair one’s ability to work, resulting in SNAP participation.

The objectives of this study were to (1) confirm that SNAP participation is associated with obesity among adults from a representative sample of households in Los Angeles County and (2) determine whether the association between SNAP participation and obesity is mediated by mental health. To our knowledge, this hypothesis has not been empirically tested before.

METHODS

This study is based on data from the Los Angeles Family and Neighborhood Survey (L.A.FANS), wave 1. L.A.FANS used a multistage stratified sampling design, with 65 census tracts in Los Angeles County randomly selected from each of 3 strata (very poor, poor, and not poor, based on poverty tract distributions) and ~50 households randomly selected from each census tract.16 Households with children were oversampled to represent 70% of the sample.16 For this study we used the adult sample, focusing on a subpopulation of SNAP participants and eligible nonparticipants (n = 1176). L.A.FANS questionnaires were administered through computer-assisted personal interview in both English and Spanish between April 2000 and January 2002.16

Our dependent variable was obesity, defined as having a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30 kg/m2. BMI was estimated from self-reported weights and heights. Our independent variable was SNAP participation, which was dichotomized into yes/no (with the “no” group including only eligible nonparticipants). SNAP eligibility was assessed following California SNAP rules; people considered eligible had to pass the gross and net income determination tests (<130% and <100% of the Federal Poverty Level, respectively) and not exceed the maximum value of assets allowed ($3000 and $2000 for households with and without seniors or disabled members, respectively).17,18 Assets included cash, checking or savings account balances, savings certificates, stocks, bonds, buildings or land other than one’s home, and car(s).15 Only US citizens, nationals, or documented immigrants who met the criteria above were considered SNAP eligible. Lastly, in California people receiving Supplemental Security Income (SSI) receive SNAP benefits in cash form, added to their SSI.18 Given that we wanted to study the effects of receiving noncash SNAP benefits (ie, with the restriction of purchasing food items only), we excluded SSI participants from the study.

Mental health status (mediator) was defined as a dichotomous variable; respondents were classified as having a mental health problem if they responded yes to at least one of the following questions: “Has a doctor ever told you that you have (1) any emotional, nervous, or psychiatric problems? or (2) major depression?” Other demographic variables used for sample description included gender, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, or other), marital status (married, living with a partner, or single), educational attainment (less than high school, high school graduate or above), nativity status and years in the United States (US born, foreign born with ≥ 10 years in the United States, foreign born with <10 years in the United States), preferred language (English, Spanish), working status (currently employed yes/no), annual income per family member, and food insufficiency (assessed by the single question: “In the past 12 months, was there ever a time when anyone in your household didn’t get enough to eat because there wasn’t enough money for food?” with response options yes/no).

Statistical Analyses

We used SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, 2010) for data analyses, with a P value < .05 denoting statistical significance. All analyses were weighted with L.A.FANS–provided sample weights and specific SAS commands for survey data were used. We first carried out descriptive statistics to characterize the sample. Then, we conducted bivariate logistic regression analyses to examine the relationship of individual characteristics with SNAP participation and obesity and estimated the unadjusted associations of obesity, SNAP participation, and mental health.

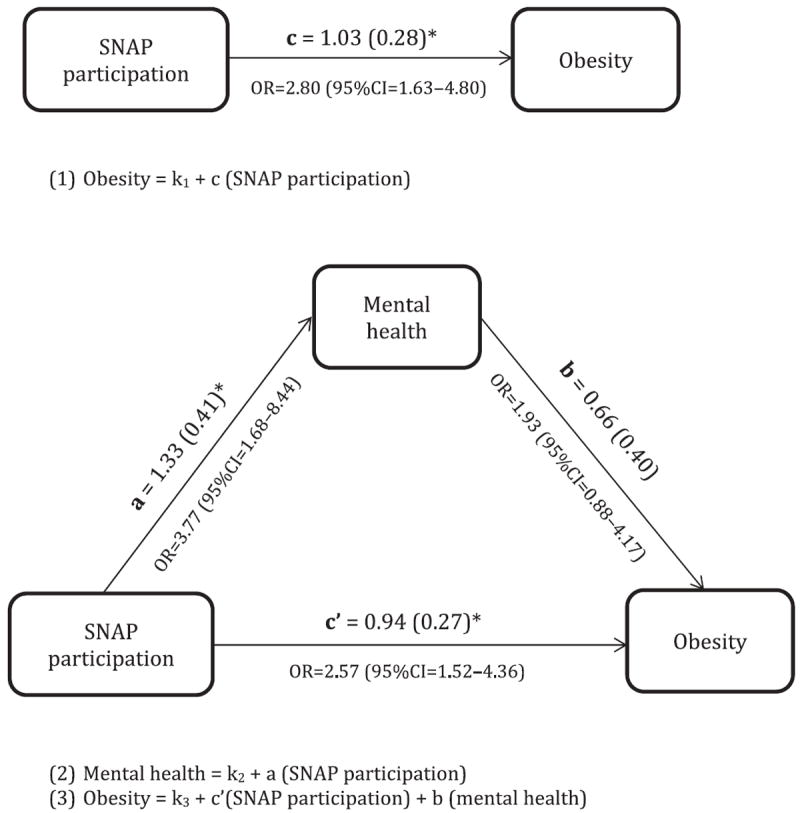

Because our dependent variable, independent variable, and mediator variables are categorical, we applied an adaptation19 of the classical mediation test proposed by Baron and Kenny.20 Figure 1 shows the operationalization of this analysis. We fitted Eqs. (1), (2), and (3) in Figure 1 with 3 separate logistic regressions, all adjusted by age, race/ethnicity, and marital status because a previous study with the same population found these variables to predict SNAP participation.21 In addition, gender and working status were associated with obesity in the current analyses and were also included as possible confounders. We obtained a and the standard error of a (SEa) from Eq. (2) and b and the standard error of b (SEb) from Eq. (3). Using these, we then calculated Za = a/SEa and Zb = b/SEb, their product Za * Zb, and their collected standard error . Finally, we calculated: and compared it to the normal Z distribution to estimate significance (i.e., if Zmediation > |1.96| then the test is significant at α = .05).19

FIGURE 1.

Operationalization and results of the mediation analyses between participation in the Special Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), obesity, and mental health.

*Statistically significant at p < 0.05; estimate (standard error)

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

In bivariate analyses, SNAP participants and eligible nonparticipants were different in terms of race/ethnicity, marital status, education, income, working status, nativity and years in the United States, and food insufficiency (Table 1). Obesity prevalence among SNAP participants was almost double (30% vs 17%) and the prevalence of having a mental health problem more than triple (20% vs 6%) when compared to eligible nonparticipants. Mental health did not mediate the association between SNAP participation and obesity (Figure 1): The Zmediation value was 1.42, which is < |1.96| and, therefore, not significant. Results from multivariate mediation analyses show that SNAP participants had almost three times the odds of being obese when compared with eligible nonparticipants (odds ratio [OR] = 2.8, 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.6–4.8; Figure 1); this association was only slightly attenuated when mental health was incorporated into the model (OR = 2.6, 95% CI, 1.52–4.4; Figure 1). Those who participated in SNAP had ~4 times the odds of reporting a mental health problem compared to eligible nonparticipants.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the Analytical Sample of SNAP Participants and Eligible Nonparticipants and Prevalence of Obesity by Demographic Characteristics (n = 1176)a

| SNAP participants (n = 412) (%) | SNAP eligible, nonparticipants (n = 764) (%) | P valueb | Obese (n = 248) (%) | Not obese (n = 798) (%) | P valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (SE) | 35.9 (1.1) | 45.4 (1.3) | <.0001 | 43.9 (2.2) | 42.6 (1.3) | .6042 |

| Gender (% female) | 62.0 | 55.2 | .2352 | 78.0 | 48.9 | <.0001 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 34.1 | 32.3 | Ref. | 29.5 | 34.5 | Ref. |

| Non-Hispanic black | 22.7 | 9.3 | <.0001 | 14.0 | 12.2 | .7566 |

| Hispanic | 41.5 | 46.2 | .3874 | 46.1 | 43.9 | .9384 |

| Other | 1.9 | 12.2 | <.0001 | 10.3 | 9.3 | .8750 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 35.2 | 48.1 | Ref. | 43.4 | 45.7 | Ref. |

| Living with partner (not married) | 20.7 | 4.9 | <.0001 | 8.9 | 9.1 | .9345 |

| Single | 44.0 | 46.9 | .0093 | 47.7 | 45.2 | .7326 |

| Educational attainment | .0139 | .4055 | ||||

| Less than high school | 46.4 | 33.6 | 40.9 | 35.8 | ||

| High school or more | 53.6 | 66.4 | 59.1 | 64.2 | ||

| Gross annual earned income per family member, $, mean (SE) | 4108 (361) | 1880 (170) | <.0001 | 3068 (488) | 2329 (186) | .1023 |

| Currently working (% yes) | 35.0 | 48.6 | .0128 | 34.5 | 48.4 | .0276 |

| Nativity and years in the United States | ||||||

| US born | 60.7 | 54.3 | Ref. | 49.7 | 57.2 | Ref. |

| Foreign born, ≥10 years in the United States | 29.1 | 37.8 | .0490 | 45.1 | 34.3 | .1023 |

| Foreign born, <10 years in the United States | 10.2 | 7.9 | .2787 | 5.2 | 8.4 | .3515 |

| Language preference | .8304 | .4990 | ||||

| English | 72.6 | 73.4 | 70.8 | 74.2 | ||

| Spanish | 27.4 | 26.6 | 29.2 | 25.8 | ||

| Food insufficiency (% yes) | 14.0 | 5.7 | .0102 | 7.2 | 7.9 | .8263 |

| Mental health problem (% yes) | 19.9 | 6.4 | .0005 | 16.3 | 8.1 | .0483 |

| Obesity (% yes) | 30.4 | 16.5 | .0035 | NA | NA |

SNAP indicates Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program; NA, not available.

P values obtained from weighted bivariate logistic regressions.

Multiple studies have now shown that SNAP participation is associated with increased obesity risk. Most of these studies have found this association to be true only for women; only a few have also observed this association in men.1,5,22 Unfortunately, we did not have the power to stratify our analyses by gender, given the small number of men included in our analytical sample (n = 278). Our results, however, remain the same if the sample is limited to women only (not shown).

Despite the observed positive association between SNAP participation and both mental health and obesity, mental health was not a mediator in the SNAP participation–obesity relationship. This finding may have a few possible explanations:

Mental health is a mediator in SNAP participation–obesity relationship but our mental health indicator was not sensitive enough to detect existing mediating effects. We used a doctor’s diagnosis of major depression and/or any emotional, nervous, or psychiatric problem as a measure of mental health. This self-reported measure may not be an adequate measure of mental health status. It does not measure chronic stress, which has been more clearly linked to obesity,12,13 and it does not include undiagnosed mental health issues. Moreover, this measure may underestimate the true prevalence of mental health problems given that people may choose not to disclose their diagnoses in a questionnaire.

Having poor mental health is not a mediator in the SNAP participation–obesity link. It is plausible that mental health, SNAP participation, and obesity are linked through alternative pathways. For example, poor mental health can lead to both SNAP participation and obesity. Further, the association may be even more complex, and poor mental health may lead to SNAP participation, with SNAP participation further compromising mental health. Alternatively, SNAP participation may have a positive impact on mental health among certain subpopulations because it may alleviate food insecurity,23,24 while leading to a poorer mental health among others.5-9 More research is needed with detailed validated mental health indicators to disentangle the associations between SNAP participation, mental health, and obesity.

There may be other mediators that better explain the association between SNAP participation and obesity. Previous research shows that SNAP participants consume more energy25 and more meat, added sugar, and fats26 than eligible nonparticipants. Further, receiving SNAP benefits once a month seems to lead to a period of binge eating followed by a period of food restriction once the SNAP benefits ran out (called the food stamp cycle); this could presumably lead to obesity.27,28 It is possible that both dietary patterns and poor mental health mediate the relationship between SNAP participation and obesity. Future studies should attempt to test the effect of these factors simultaneously.

Strengths and Limitations

One strength of this study includes the extensive amount of income-related information collected on L.A.FANS, which allowed us to more accurately assess SNAP eligibility, getting one step closer to the true eligible nonparticipant group to use as a control. Based on a previous study with the same population,21 we determined factors that predicted SNAP participation and included them as confounders in our analyses. Still, we cannot fully account for self-selection into SNAP and it is possible that some unmeasured characteristics that drive people to participate in SNAP also increase people’s risk for obesity. Because this study took place in Los Angeles County, our results apply only to its population. However, focusing only in Los Angeles may have reduced the “noise” inherently present when making cross-county (or state) comparisons given differences in eligibility clauses and generosity of benefits observed in different states. This is a cross-sectional study, which makes it difficult to ascertain the direction of the associations found. Moreover, all of our measures (BMI, SNAP participation, mental health) are based on self-reports and therefore subject to bias. Even though there is evidence that self-reported and measured weights and heights are highly correlated among a subsample of L.A.FANS respondents,29 the potential for misreporting remains. Self-reported mental health may also be problematic because people not diagnosed by a doctor, or those diagnosed but who chose not to disclose their diagnoses in the L.A.FANS questionnaire, would have been excluded from our measure.

CONCLUSIONS

To date there is mounting evidence that SNAP participation is associated with obesity, but the causal mechanisms have yet to be established. Regardless of the causal pathways linking SNAP participation and obesity, researchers recognize the potential of SNAP to help prevent obesity because it reaches low-income populations who have high rates of obesity and chronic diseases. Although the US Department of Agriculture has not officially proposed any changes to SNAP,30 some suggested modifications with broad public support31 include targeted price manipulation through bonuses or coupons for fruit and vegetable purchases,32 requiring SNAP vendors to carry healthier options,33 and restricting the purchase of sodas and other unhealthy foods.33-37 A recent study has shown that banning the purchase of sugar-sweetened beverages with SNAP dollars would lead to a reduction in obesity prevalence among SNAP participants of 0.9 percentage points in 10 years, which translates into approximately 422 000 fewer people suffering from obesity.37 Our results support the idea that a realignment of SNAP goals with public health objectives and incentivizing healthier food habits among participants is needed. Further, we encourage the promotion of alternative ways to enroll in SNAP, such as online and by phone,38 in order to reduce the stress associated with the SNAP application. Further research should also focus on disentangling the association between SNAP participation, mental health, and obesity.

References

- 1.ver Ploeg M, Ralston K. Food Stamps and Obesity: What Do We Know? Washington, DC: US Deparment of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeBono NL, Ross NA, Berrang-Ford L. Does the food stamp program cause obesity? A realist review and a call for place-based research. Health Place. 2012;18:747–756. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Department of Agriculture, Food & Nutrition Service, Office of Research and Analysis. [June 30, 2014];Building a Healthy America: A Profile of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. 2012 doi: 10.3945/an.112.002949. Available at: http://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/BuildingHealthyAmerica.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Cawley J, Meyerhoefer C. The medical care costs of obesity: an instrumental variables approach. J Health Econ. 2012;31:219–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zagorsky JL, Smith PK. Does the US Food Stamp Program contribute to adult weight gain? Econ Hum Biol. 2009;7:246–258. doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heflin CM, Ziliak JP. Food insufficiency, food stamp participation, and mental health. Soc Sci Q. 2008;89:706–727. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Purtell KM, Gershoff ET, Aber JL. Low income families’ utilization of the federal “safety net”: individual and state-level predictors of TANF and Food Stamp receipt. Children Youth Serv Rev. 2012;34:713–724. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rodriguez E, Frongillo EA, Chandra P. Do social programmes contribute to mental well-being? The long-term impact of unemployment on depression in the United States. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30:163–170. doi: 10.1093/ije/30.1.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ponza M, Ohls J, Moreno L, et al. Customer Service in the Food Stamp Program: Final Report. Prepared by Mathematica Policy Research, Inc, for the US Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, Office of Analysis and Evaluation; Washington, DC: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manchester CF, Mumford KJ. Welfare Stigma Due to Public Disapproval. Minneapolis, MN: Department of Applied Economics, University of Minnesota; 2010. [June 30, 2014]. Available at: http://documents.apec.umn.edu/ApEcSemSp2010Manchester%20paper.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Food Research and Action Center. [June 30, 2014];Access and Access Barriers to Getting Food Stamps: A Review of the Literature. 2008 Available at: http://frac.org/wp-content/uploads/2009/09/fspaccess.pdf.

- 12.Scott K, Melhorn S, Sakai R. Effects of chronic social stress on obesity. Curr Obes Rep. 2012;1:16–25. doi: 10.1007/s13679-011-0006-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moore CJ, Cunningham SA. Social position, psychological stress, and obesity: a systematic review. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112:518–526. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faith MS, Butryn M, Wadden TA, et al. Evidence for prospectives associations among depression and obesity in population-based studies. Obes Rev. 2011;12:e438–e453. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pan A, Sun Q, Czernichow S, et al. Bidirectional association between depression and obesity in middle-aged and older women. Int J Obes. 2012;36:595–602. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peterson CE, Sastry N, Pebley AR, et al. The Los Angeles Family and Neighborhood Survey Codebook. Los Angeles, CA: RAND; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 17.California Department of Social Services CalFresh. [June 30, 2014];Eligibility and Issuance Requirements. 2007 Available at: http://www.calfresh.ca.gov/PG841.htm.

- 18.Legal Services of Northern California, California Food Policy Advocates, Neighborhood Legal Services of Los Angeles County, Western Center on Law and Poverty. [June 30, 2014];The California guide to the Food Stamp Program, 2001–2011. Available at: http://foodstampguide.org.

- 19.Iacobucci D. Mediation analysis and categorical variables: the final frontier. J Consum Psychol. 2012;22:582–594. doi: 10.1016/j.jcps.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chaparro MP, Harrison G, Pebley A. Individual and neighborhood predictors of participation in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) in Los Angeles County. J Hunger Environ Nutr. doi: 10.1080/19320248.2014.962768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leung CW, Villamor E. Is participation in food and income assistance programmes associated with obesity in California adults? Results from a state-wide survey. Public Health Nutr. 2011;14:645–652. doi: 10.1017/S1368980010002090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim K, Frongillo EA. Participation in food assistance programs modifies the relation of food insecurity with weight and depression in elders. J Nutr. 2007;137:1005–1010. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.4.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mabli J, Worthington J. Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program participation and child food security. Pediatrics. 2014;1334(4):610–619. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-2823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Currie J. US Food and Nutrition Programs. Los Angeles, CA: National Bureau of Economic Research, UCLA Department of Economics; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilde P, McNamara PE, Ranney C. The Effect on Dietary Quality of Participation in the Food Stamp and WIC Programs. Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shapiro JM. Is there a daily discount rate? Evidence from the food stamp nutrition cycle. J Public Econ. 2005;89:303–325. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilde P, Ranney C. The monthly food stamp cycle: shopping frequency and food intake decisions in an endogenous switching regression framework. Am J Agric Econ. 2000;82:200–213. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones M. Self-assessing weight status: a comparison of self-assessment and measurement of weight among Los Angeles County adults. Paper presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Public Health Association; October 29–November 2, 2011; Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alston JM, Mullally CC, Sumner DA, et al. Likely effects on obesity from proposed changes to the US food stamp program. Food Policy. 2009;34:176–184. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Long MW, Leung CW, Cheung LWY, et al. Public support for policies to improve the nutritional impact of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Public Health Nutr. 2012;17:219–224. doi: 10.1017/S136898001200506X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guthrie JF, Andrews M, Frazao E, et al. Can Food Stamps Do More to Improve Food Choices? An Economic Perspective. Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ohri-Vachaspati P, Wharton C, DeWeese R, et al. Policy Considerations for Improving the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program: Making a Case for Decreasing the Burden of Obesity. Phoenix, AZ: School of Nutrition and Health Promotion, Arizona State University; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Andreyeva T, Luedicke J, Henderson KE, et al. Grocery store beverage choices by participants in federal food assistance and nutrition programs. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43:411–418. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hernandez DC. Soda consumption among food insecure households with children: a call to restructure food assistance policy. J Appl Res Child. 2012;3(1) Article16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leung CW, Hoffnagle EE, Lindsay AC, et al. A qualitative study of diverse experts’ views about barriers and strategies to improve the diets and health of Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) beneficiaries. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013;113:70–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2012.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Basu S, Seligman HK, Gardner C, Bhattacharya J. Ending SNAP subsidies for sugar-sweetened beverages could reduce obesity and type 2 diabetes. Health Aff. 2014;33:1032–1039. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.California Food Policy Advocates. [June 30, 2014];Improving the CalFresh Enrollment Process for Applicants: CFPA Recommendations. 2012 Available at: http://cfpa.net/CalFresh/CFPAPublications/CalFresh-ApplicantExperienceRecs-2012.pdf.