Abstract

Risk-related liabilities associated with the development of cannabis use disorders (CUDs) during adolescence and early adulthood are thought to be established well before the emergence of the index episode. In this study, internalizing and externalizing psychopathology from earlier developmental periods were evaluated as risk factors for CUDs during adolescence and early adulthood. Participants (N = 816) completed four diagnostic assessments between the ages 16 and 30, during which current and past CUDs were assessed as well as a full range of psychiatric disorders associated with internalizing and externalizing psychopathology domains. In unadjusted and adjusted time-to-event analyses, externalizing but not internalizing psychopathology from proximal developmental periods predicted subsequent CUD onset. A large proportion of adolescent and early adult cases, however, did not manifest any externalizing or internalizing psychopathology during developmental periods prior to CUD onset. Findings are consistent with the emerging view that externalizing disorders from proximal developmental periods are robust risk factors for CUDs. Although the identification of externalizing liabilities may aid in the identification of individuals at risk for embarking on developmental pathways that culminate in CUDs, such liabilities are an incomplete indication of overall risk.

Keywords: Cannabis use disorders, predictors, psychopathology, externalizing, internalizing, gender

Although adolescent and early adult developmental periods are associated with the greatest risk for cannabis experimentation and the subsequent progression to abuse or dependence (Dengenhardt et al., 2013; Fergusson & Horwood, 2000; Johnston, O’ Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2013), risk factors that influence these events are often evident earlier in development. A contemporary view on the epidemiology of substance use disorders among adolescents and young adults suggests that multiple factors related to processes that increase vulnerabilities to externalizing and internalizing psychiatric disorders contribute to overall risk (Vanyukov et al., 2012; Zucker, Donovan, Masten, Mattson, & Moss, 2008). The internalizing externalizing-organizational model of psychopathology (Achenbach, 1966; Krueger, 1999) has received considerable support for describing patterns of psychiatric symptom and disorder covariation among children and adults in cross-sectional and longitudinal studies (e.g., Achenbach, 1966; Farmer, Seeley, Kosty, Olino, & Lewinsohn 2013b; Kessler et al., 2011; Krueger & Markon, 2006; Lahey et al., 2008), and has been suggested as a viable model for guiding research on common causal pathways that account for disorder comorbidity (Kessler et al., 2011; Krueger, 1999).

Externalizing tendencies and their precursors constitute a broad liability for disruptive behavior and substance use disorders inclusive of cannabis abuse or dependence disorders (collectively, cannabis use disorders or CUDs; Farmer, Seeley, Kosty, & Lewinsohn, 2009; Iacono, Malone, & McGue, 2008; Krueger & Markon, 2006). Prospective studies, for example, have documented that externalizing tendencies and associated attributes frequently precede the onset of cannabis initiation (Agrawal, Lynskey, Bucholz, Madden, & Heath, 2007; Griffith-Lendering, Huijbregts, Mooijaart, Vollebergh, & Swaab, 2011b; Kandel & Yamaguchi, 1993; King, Iacono, & McGue, 2004; van den Bree & Pickworth, 2005) and CUDs (Blanco et al., 2014; Brook, Lee, Finch, Koppel, & Brook, 2011; Fergusson, Horwood, & Ridder, 2007; Hayatbakhsh et al., 2008; Tarter, Kirisci, Ridenour, & Vanyukov, 2008; although see Wittchen et al., 2007, who did not find a significant prospective association with externalizing disorders).

The contributions of internalizing tendencies and their precursors to the risk for cannabis initiation and CUDs are less clear. Although CUDs and internalizing disorders are highly comorbid and share common risk factors (Grant et al., 2004), prospective studies have been equivocal as to whether internalizing symptoms or disorders afford a significant risk for later cannabis use or CUDs. Some studies have found that internalizing symptoms or disorders predict later cannabis use (Henry et al., 1993; Paton, Kessler, & Kandel, 1977) or CUDs (Wittchen et al., 2007), whereas findings reported by Colder et al. (2013) imply that internalizing features in the absence of externalizing features may act as a protective factor against cannabis use. Other researchers found no prospective association between internalizing features or disorders and subsequent cannabis use (Griffith-Lendering et al., 2011b; Miller-Johnson, Lochman, Coie, Terry, & Hyman, 1998) or CUDs (Tarter et al., 2008). Mixed findings concerning internalizing features may be related to differences in statistical control of psychopathology-related confounders across studies. An earlier prospective analysis based on Oregon Adolescent Depression Project (OADP) data (Buckner et al., 2008), which constitutes the parent study for the present investigation, found that a diagnosis of social phobia at baseline was associated with an increased risk for cannabis dependence (but not cannabis abuse) at a fourteen-year follow-up. This study, however, exercised limited control over concurrent or lifetime externalizing psychopathology that might account for longitudinal associations between social phobia and cannabis dependence.

Although there is ample research on internalizing and externalizing predictors of cannabis initiation and use, there is considerably less research on these domains as predictors of CUD onset. The distinction between cannabis initiation or use and CUDs is an important one when investigating the developmental pathways that constitute a heightened risk for hazardous cannabis use. Contemporary views suggest that CUD risk is related to underlying biologically based mechanisms, whereas cannabis initiation and occasional use are largely the product of shared and non-shared environmental factors (Vanyukov et al., 2012; Verweij et al., 2010). The biological underpinnings of CUDs likely arise from a common liability shared with other substance use disorders, externalizing behavioral disorders, and possibly internalizing disorders (Vanyukov et al., 2012; Zucker et al., 2008). To the extent that such risk liabilities are shared among families of related lifetime disorders that are initially expressed during childhood, their existence should be evident well before the onset of CUDs. Correspondingly, a primary objective of this research was to evaluate whether earlier manifestations of internalizing and externalizing psychopathology predict CUD onset.

Prior research on predictors of cannabis initiation and CUD onset has generally not considered the possibility of the developmental specificity of predictors. In one exception, van den Bree and Pickworth (2005) found both common and developmental period-specific risk factors were associated with the progression from cannabis initiation to regular use. Blanco et al. (2014) further reported that proximal externalizing tendencies, or those that are manifest closer to the onset of problematic cannabis use, are generally more salient predictors of risk than similar distal (e.g., childhood) tendencies. Maslowsky, Schulenberg, and Zucker (2014), however, reported that conduct problems in the 8th grade (distal) assessed via a short self-report questionnaire were better predictors of cannabis use in the 12th grade than comparable problems reported during the 10th grade (proximal). Given the mixed pattern of findings concerning the temporal specificity of predictors, this study investigated the relative salience of adolescent versus childhood internalizing and externalizing tendencies in the prediction of CUD onsets in early adulthood.

As noted earlier, research on internalizing and externalizing predictors of cannabis initiation or CUD onset has generally not considered either domain following the control of the other. Given that internalizing and externalizing psychopathology covary (Farmer et al., 2013b; Krueger, 1999; Lahey et al., 2008), erroneous conclusions about the relative contributions of either domain as risk factors for CUDs might be reached when the other domain is not simultaneously considered and controlled. Consequently, in the present research, we evaluated unadjusted and adjusted prediction models, with the latter controlling for demographic and psychosocial variables as well as the psychopathology domain that was not the predictor variable modeled in the analysis.

Finally, we evaluated whether gender moderates associations between internalizing and externalizing psychopathology and subsequent CUD onsets. Although reliable gender differences in cannabis use often begin to emerge during late adolescence and early adulthood, with males tending to use more frequently or at a higher rate than females (Agrawal & Lynskey, 2007; Kandel & Chen, 2000; Perkonigg et al., 2008), there has been little investigation of, or evidence for, systematic gender moderation of psychopathology-related risk factors associated with the onset of CUDs (Blanco et al., 2014; Costello, Erkanli, Federman & Angold, 1999). Our tests of gender moderation of psychopathology domain effects were, therefore, exploratory.

Method

Participants

This study is based on the OADP (Lewinsohn, Hops, Roberts, Seeley, & Andrews, 1993), a longitudinal study of an adolescent cohort from the community. At the first wave of data collection (T1; ~ age 16), the sample consisted of 1,709 adolescents randomly selected from 9 high schools that were representative of urban and rural districts in western Oregon. About one year later (T2), 1,507 (88%) of these persons were reassessed. At T3 (~ age 24), a sampling stratification procedure was introduced whereby eligible participants included all individuals self-identified as non-White to enhance ethnic diversity, all persons with a positive history of a psychiatric diagnosis by T2(n = 644), and a randomly selected subset of participants with no history of a psychiatric or substance use disorder by T2(n = 457 of 863 persons). Of these 1,101 eligible persons, 941 (85%) completed T3. The T4 assessment (~ age 30) included 816 T3 participants (87%) and was conducted approximately 6 years after T3.

We previously reported period and lifetime prevalence rates for CUDs in the OADP sample (Lewinsohn et al., 1993; Farmer et al., 2015, respectively). Briefly, by age 30.0, 19.1% of the weighted T4 panel had a lifetime CUD diagnosis (22.5% male, 16.4% female, p < .05). For those with a lifetime CUD episode by age 30.0, the mean age at time of first CUD onset was 18.6 years (SD = 4.1; Mdn = 18.2). Analyses of participant attrition revealed only minimal sample bias related to study discontinuation (Farmer et al., 2015; Farmer, Kosty, Seeley, Olino, & Lewinsohn, 2013a; Lewinsohn et al., 1993).

The reference sample for this study varied in accordance with the research question. Demographic predictors of CUD onset were evaluated using data from the complete T4panel (n = 816). Psychiatric predictors of adolescent CUD onset (between ages 13.0 and 17.9) were evaluated using data from participants without an incidence of CUD between ages 0 and 12.9 (n = 804), in which CUD episodes occurring at or after age 18 were right-censored.1 Psychiatric predictors of early adult CUD onset (between ages 18.0 and 30.0) were evaluated using data from participants without an incidence of CUD before age 17.9 (n = 727).

Diagnostic Assessments

During T1, T2, and T3, participants were interviewed with the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children (K-SADS) that combined features of the Epidemiologic and Present Episode versions (Chambers et al., 1985; Orvaschel, Puig-Antich, Chambers, Tabrizi, & Johnson, 1982). Follow-up assessments at T2and T3 also involved the administration of the Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation (LIFE; Keller et al., 1987) that, in conjunction with the K-SADS, provided detailed information related to the presence and course of disorders since participation in the previous interview. The T4 assessment included administration of the LIFE and the Structured Clinical Interview for Axis I DSM-IV Disorders – Non-Patient Edition (SCID-NP; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1994). Diagnostic agreement was good to excellent across assessment waves (kappa = .56 to .84 for diagnostic categories other than CUD; median = .77; see Farmer et al., 2013a, for more details).

Diagnostic interviews included the assessment of current episodes (i.e., within the last 12 months) and since the last interview (or, in the case of the T1assessment, ever in the past), and disorder onsets and offsets were recorded as age in months. The presence versus absence of specific diagnostic categories, including cannabis abuse and cannabis dependence, was therefore represented continuously in one-month increments between childhood and age 30.0. For this study, cannabis abuse and dependence diagnoses were combined into a single category (CUDs) to indicate syndromal cannabis use that resulted in significant impairment in functioning or distress, with the timing of the episode onset denoted by age in months. Hazard rates (described below) were estimated for recovery in 1-month intervals commencing with the onset of the first CUD episode. Diagnostic agreement among raters for CUD diagnoses since the previous interview was good to excellent at each wave (kappas: T1 = .72, T2 = .93, T3 = .83, T4 = .82).

Childhood and Adolescent Predictors of CUD Onset

In a set of prospective analyses described below, we evaluated the degree to which internalizing and externalizing psychopathology were predictors of CUD onset, further differentiated into adolescent onset (ages 13 to 17.9) and early adult onset (ages 18.0 to 30.0). In models predicting adolescent CUD onset, we evaluated psychopathology occurring between ages 8.0 to 12.9 as childhood predictors. In models predicting early adult CUD onset, we evaluated psychopathology occurring from ages 8.0 to 12.9 and from 13.0 to 17.9 as childhood and adolescent predictors, respectively.

Internalizing and externalizing disorder domain scores were categorically modeled, whereby a value of 0 was assigned if no disorder associated with a given domain was diagnosed and a value of 1 assigned if one or more domain-related disorders was diagnosed within the timeframe specified. Diagnostic criteria and disorder threshold cut-offs are related to clinical impressions about the severity of a disorder that, in turn, warrants treatment when the diagnosis is reached (Fergusson, Horwood, & Lynskey, 1994). Based on our earlier research in explicating domains of lifetime psychopathology with the OADP sample (Farmer et al., 2009; Farmer et al., 2013b; Seeley, Kosty, Farmer, & Lewinsohn, 2011), DSM-defined disorders that contributed to the internalizing domain, further distinguished by DSM-defined subdomains, were: mood disorders (major depressive; dysthymia; bipolar spectrum inclusive of bipolar I, bipolar II, and cyclothymic disorders), anxiety disorders (separation anxiety, simple/specific phobia, generalized anxiety, obsessive–compulsive, panic, agoraphobia without panic, post-traumatic stress, social phobia), and bulimia nervosa. Disorders that contributed to the definition of the externalizing domain, further distinguished by DSM-defined subdomains, were: disruptive behavior disorders (attention deficit/hyperactivity, oppositional defiant, conduct) and non-cannabis-related substance use disorders (alcohol use disorders, which includes alcohol abuse or dependence diagnoses; hard drug use disorders, which includes the abuse or dependence of substances other than cannabis and alcohol).

Statistical Analyses

Most of the earlier predictive studies of cannabis initiation or CUD onset have utilized logistic regression methods. Cox proportional hazards (PH) regression methods, however, take into account time until an outcome event, and generally have more associated statistical power and yield more precise effect estimates than logistic regression models (Callas, Pastides, & Hosmer, 1998; van der Net et al., 2008). To fully exploit longitudinal information available from our data set, primary analyses utilized Cox PH models. Hazard ratios (HR) and the 95% confidence intervals produced from these analyses are based on the ratio of CUD onset probabilities, specifically differences in hazard rates as a linear function of the predictor variables. They are, therefore, relative indicators of risk, reflect any differences in hazard functions, and specify the increased likelihood of developing a CUD within a unit of time (months) as a function of the presence versus absence of a psychopathology-domain related diagnosis.

The developmental period analyses presented below adhered to the following data analytic sequence, separately for those with initial adolescent and early adult CUD onsets: (a) descriptive data on the course of CUDs; (b) non-parametric tests of rate differences of individuals who had either internalizing and externalizing disorders (i.e., any psychopathology) in the preceding developmental period(s) as a function of the presence versus absence of an initial CUD diagnosis in the reference developmental period; (c) separate non-parametric tests of rate differences in internalizing and externalizing disorder occurrences within the preceding developmental period(s) as a function of the presence versus absence of an initial CUD diagnosis in the reference developmental period; and, (d) unadjusted and adjusted time-to-event analyses that predicted CUD onset as a function of internalizing and externalizing psychopathology in the preceding developmental period(s). Time-to-event analyses were further distinguished at three levels: (a) unadjusted omnibus bivariate analyses, whereby psychiatric disorder domain variables (i.e., internalizing and externalizing) were individually evaluated as predictors of CUD onset without concurrent consideration of the possible influence of putative confounders; (b) adjusted omnibus multivariate analyses, whereby internalizing and externalizing domains were individually evaluated as predictors of CUD onset following control of putative confounders, including the superordinate psychopathology domain that was not the target variable of the analysis; and, (c) separate unadjusted and adjusted time-to-event analyses that evaluated DSM- defined disorder subgroupings within the internalizing and externalizing superordinate domains to better isolate whether subgroups of related disorders evidenced different predictive associations with CUD onset. Internalizing subdomains were mood disorders and anxiety disorders. Externalizing subdomains were disruptive behavior disorders and non-cannabis-related substance use disorders (“other SUDs”). Time to CUD onset was expressed in month increments beginning with the start of the developmental period.

As a result of the unequal stratified sampling strategy implemented at T3, Caucasian participants without a psychiatric diagnosis by T2 were under-sampled at T3 and T4. To adjust for this sampling procedure, Caucasian participants with no lifetime diagnosis by T2 were assigned a weight that reflected the probability of this subgroup being sampled during T3 and T4 assessments. The Taylor series linearization method (Wolter, 1985) was implemented in SUDAAN version 11.0.0 (Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina) to appropriately adjust standard errors and confidence intervals for the parameter estimates. To avoid artificially inflating our sample size, we computed normalized sampling weights. Unless otherwise specified, all findings subsequently presented (e.g., rates, ratios) were based on weighted data, and references to the numbers of cases were based on unweighted data.

Results

Demographic Predictors of CUD Onset

By T4, 77 and 84 participants had initial CUD onsets during the adolescent and early adult developmental periods, respectively. Demographic variables were individually evaluated as predictors of CUD onset with Cox PH regression methods.2 Findings from these analyses, which were conducted with the entire participant sample, are presented in Table 1. Male participants and those who resided in a single parent household at T1 were significantly more likely to experience a CUD episode at any time interval through age 30 (Hazard ratios [HR] = 1.42 and 1.82, respectively). All demographic variables, regardless of their individual significance, were included among the covariates in adjusted analyses reported below.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Demographic Variables and Bivariate Associations with CUD Onset through Age 30 (n = 816)

|

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | No CUD (n = 643) | CUD (n = 173) | Test Statistica | p-value | Hazard ratio |

| Participant Characteristics | |||||

| Male, % [CI95] | 42.0 [38.3, 45.8] | 51.7 [43.8, 59.5] | 4.77 | .030 | 1.42 [1.03, 1.95] |

| Non-white, % [CI95] | 7.4 [5.5, 9.5] | 9.2 [5.3, 14.4] | 0.57 | .449 | 1.29 [0.79, 2.08] |

| Pubertal timing, % [CI95] | |||||

| Early (n = 153) vs. on-time (n = 567), % [CI95] | 19.0 [15.9, 22.3] | 24.8 [18.0, 32.5] | 2.22 | .136 | 1.40 [0.94, 2.07] |

| Late (n = 96) vs. on-time (n = 567), % [CI95] | 13.6 [10.9, 16.7] | 17.8 [11.7, 25.2] | 1.34 | .248 | 1.33 [0.82, 2.14] |

| Early (n = 153) vs. late (n = 96), % [CI95] | 59.7 [52.6, 66.6] | 60.4 [47.2, 72.6] | 0.01 | .928 | 1.06 [0.61, 1.82] |

| Repeat grade before age 12, % [CI95] | 10.1 [8.0, 12.6] | 13.9 [9.1, 19.9] | 1.75 | .186 | 1.38 [0.89, 2.15] |

| Family Demographic Variables | |||||

| Single versus dual parent household, % [CI95] | 60.6 [56.8, 64.3] | 44.2 [36.6, 52.1] | 13.66 | < .001 | 1.82 [1.33, 2.50] |

| At least one parent completed college, % [CI95] | 44.9 [41.1, 48.7] | 41.0 [33.5, 48.8] | 0.78 | .376 | 0.87 [0.63, 1.20] |

| Mean parent age at T1, M (SD) | 42.4 (5.9) | 41.5 (5.6) | 1.85 | .065 | 0.97 [0.94, 1.00] |

| Number of older siblings, M (SD) | 0.9 (1.1) | 0.9 (1.1) | 0.19 | .851 | 0.98 [0.85, 1.14] |

Note. CI95 = 95% confidence interval. Statistically significant hazard ratios are bolded.

Likelihood ratio chi-square and independent observation t-tests were conducted on categorical (as indicated by the % designation) and continuous variables (as indicated by the M designation), respectively.

Psychiatric Predictors of Adolescent CUD Onset

For those with initial CUD episode onsets during adolescence, the mean onset age of the first episode was 15.5 years (SD = 1.4; Mdn = 15.6). The mean duration of the index episode was 32.2 months (SD = 44.4; Mdn = 13.0).

Period prevalence rates of internalizing and externalizing disorders during childhood as a function of initial CUD onsets during adolescence

The proportions of participants with either internalizing or externalizing disorders during childhood were comparable among those without and with initial CUD onsets during adolescence (13.3% and 18.3%, respectively; Likelihood Ratio [LR] χ2 = 1.13, p = .288). The left half of Table 2 presents the period prevalence rates of internalizing and externalizing psychopathology within the childhood developmental period among participants without and with an initial CUD onset during adolescence. The only statistically significant difference in childhood psychopathology between these two groups was found in the rates of disorders from the superordinate externalizing domain (3.1% and 9.1%, respectively; LR χ2 = 4.54, p = .033).

Table 2.

Period Prevalence Rates of Internalizing and Externalizing Psychopathology and Associations with Initial CUD Onset during Adolescence

| Predictor | Period Prevalence % [CI95] |

Hazard Ratio [CI95] |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No CUD (n = 727) | CUD (n = 77) | Likelihood Ratio χ2 |

p-value | Unadjusted | Adjusted | |

| Childhood Psychopathology | ||||||

| Internalizing domain | 11.0 [8.9, 13.4] | 11.4 [5.1, 20.8] | 0.01 | .915 | 1.05 [0.53, 2.06] | 0.90 [0.45, 1.80] |

| Mood disorders | 5.8 [4.3, 7.6] | 8.0 [3.0, 16.4] | 0.47 | .494 | 1.39 [0.64, 3.04] | 1.17 [0.50, 2.73] |

| Anxiety disorders | 6.9 [5.3, 8.9] | 5.7 [1.7, 13.3] | 0.14 | .705 | 0.83 [0.33, 2.08] | 0.78 [0.31, 1.93] |

| Bulimia nervosa | 0.0 | 0.0 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Externalizing domain | 3.1 [2.0, 4.5] | 9.1 [3.6, 17.9] | 4.54 | .033 | 3.02 [1.42, 6.43] | 2.44 [1.13, 5.29] |

| Disruptive behavior disorders | 2.8 [1.8, 4.1] | 8.0 [3.0, 16.4] | 3.74 | .053 | 2.90 [1.30, 6.47] | 2.40 [1.03, 5.57] |

| Other substance use disorders | 0.3 [0.1, 0.9] | 1.1 [0.0, 6.0] | 0.79 | .374 | NA | NA |

| Either internalizing or externalizing | 13.3 [11.0, 15.9] | 18.3 [10.1, 29.0] | 1.13 | .288 | 1.24 [0.70, 2.22] | 1.45 [0.83, 2.54] |

Note. CUD = cannabis use disorder; CI95 = 95% confidence interval; NA = not analyzed as predictors due to insufficient period prevalence rates. A value of 0.0 indicates the absence of diagnosed cases within the referenced developmental period. Statistically significant hazard ratios are bolded. Adjusted analyses control for variables in Table 1 and other psychopathology. Childhood was defined as ages 8.0 to 12.9 and adolescence was defined as ages 13.0 to 17.9.

Childhood internalizing and externalizing disorders as predictors of CUD onset during adolescence

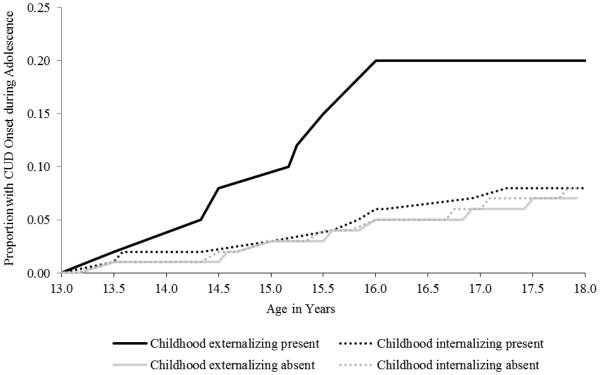

Table 2 also presents unadjusted and adjusted analyses that evaluated internalizing and externalizing domains as predictors of initial CUD onset during adolescence. Reported under the unadjusted analysis heading of the table are the total effects of psychiatric disorder domains in the prediction of CUD onset. As indicated in the right half of Table 2, childhood externalizing domain disorders significantly predicted initial CUD episodes in the adolescent onset group (HR [CI95] = 3.02 [1.42, 6.43]).3 This finding indicates that those with externalizing disorder histories during childhood had a three times greater odds of being diagnosed with a CUD during any month-length interval within the adolescent developmental period when compared to those without such histories. Cumulative hazard functions for CUD onset during adolescence by psychopathology domain during childhood are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Cumulative hazard functions for CUD onset during adolescence (ages 13.0 to 17.9) by psychopathology domain during childhood (ages 8.0 to 12.9).

We also evaluated the relative contributions of childhood internalizing and externalizing subdomains in the prediction of CUD onset during adolescence. Only subdomains with a sufficient number of observed cases within the preceding developmental period (n ≥ 20) were analyzed as predictors, resulting in the omission of other SUDs and bulimia nervosa in tests of predictors in time-to-event analyses. In unadjusted analyses, the disruptive behavior disorder subdomain emerged as a significant predictor (HR [CI95] = 2.90 [1.30, 6.47]) of adolescent CUD.

Under the adjusted analysis heading of Table 2, we report the additive effects of individual disorder domains after variance associated with putative confounders and the non-targeted psychiatric disorder superordinate domain was controlled.4 When compared to unadjusted findings, adjusted effects were generally smaller, although the effects associated with the externalizing superordinate domain (HR [CI95] = 2.90 [1.30, 6.47]) and disruptive behavior disorders subdomain (HR [CI95] = 2.40 [1.03, 5.57]) remained significant.

Childhood and Adolescent Psychiatric Predictors of Early Adult CUD Onset

For those with an initial CUD episode onset during early adulthood, the mean age of first CUD onset was 21.7 years (SD = 2.8; Mdn = 21.2). The mean duration of the index episode was 44.4 months (SD = 40.1; Mdn = 31.5).

Period prevalence rates of internalizing and externalizing disorders during childhood and adolescence as a function of initial CUD onsets during early adulthood

Period prevalence rates for either internalizing or externalizing disorders during adolescence were compared among participants without and with initial CUD onsets during early adulthood. When compared to those who did not experience an index CUD episode within this developmental period, participants with an initial CUD onset during early adulthood experienced a significantly higher rate of disorders from either of these superordinate domains during adolescence (28.0% and 44.0%, respectively; LR χ2 = 8.47, p = .004). The left half of Table 3 presents rates of internalizing and externalizing disorder occurrences for the early adult onset group, separately for adolescence and childhood. Rates of adolescent internalizing disorders at both the superordinate domain and subdomain levels, when examined separately from externalizing disorders, did not significantly differ between those without and with initial CUD onsets during early adulthood. Rates of adolescent externalizing domain disorders, however, significantly differed between those without and with initial CUD onsets during early adulthood (7.2% vs. 24.2%, respectively; LR χ2 = 19.68, p < .001). Similarly, when analyzed separately, both subdomains of externalizing disorders significantly differed between those without and with CUD onsets during early adulthood (for disruptive behavior disorders: 3.5% and 13.0%, respectively; LR χ2 = 11.14, p < .001; for other SUDs: 4.2% and 15.6%, respectively; LR χ2 = 13.34, p < .001).

Table 3.

Period Prevalence Rates of Internalizing and Externalizing Psychopathology and Associations with Initial CUD Onset during Early Adulthood

| Predictor | Period Prevalence % [CI95] |

Hazard ratio [CI95] |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No CUD (n = 643) | CUD (n = 84) | Likelihood Ratio χ2 |

p-value | Unadjusted | Adjusted | |

| Adolescent Psychopathology | ||||||

| Internalizing domain | 23.3 [20.2, 26.7] | 31.8 [22.5, 42.2] | 2.73 | .099 | 1.48 [0.95, 2.30] | 1.36 [0.86, 2.16] |

| Mood disorders | 19.6 [16.7, 22.8] | 25.7 [17.2, 35.8] | 1.62 | .203 | 1.38 [0.88, 2.18] | 1.22 [0.75, 1.97] |

| Anxiety disorders | 6.2 [4.5, 8.2] | 8.6 [3.9, 15.9] | 0.66 | .416 | 1.37 [0.68, 2.78] | 1.30 [0.63, 2.68] |

| Bulimia nervosa | 1.0 [0.4, 1.9] | 1.7 [0.2, 6.1] | 0.33 | .567 | NA | NA |

| Externalizing domain | 7.2 [5.4, 9.3] | 24.2 [15.9, 34.1] | 19.68 | < .001 | 3.60 [2.20, 5.88] | 3.15 [1.87, 5.30] |

| Disruptive behavior disorders | 3.5 [2.3, 5.1] | 13.0 [6.9, 21.2] | 11.14 | < .001 | 3.47 [1.91, 6.31] | 2.32 [1.22, 4.43] |

| Other substance use disorders | 4.2 [2.9, 6.0] | 15.6 [8.9, 24.3] | 13.34 | < .001 | 3.68 [2.04, 6.62] | 2.89 [1.53, 5.47] |

| Either internalizing or externalizing | 28.0 [24.7, 31.5] | 44.0 [33.6, 54.7] | 8.47 | .004 | 1.91 [1.22, 2.98] | 1.98 [1.24, 3.16] |

| Childhood Psychopathology | ||||||

| Internalizing domain | 10.9 [8.6, 13.4] | 12.1 [6.2, 20.2] | 0.11 | .743 | 1.11 [0.61, 2.04] | 1.08 [0.59, 1.99] |

| Mood disorders | 6.0 [4.3, 7.9] | 4.3 [1.2, 10.1] | 0.41 | .521 | 0.72 [0.29, 1.79] | 0.56 [0.21, 1.49] |

| Anxiety disorders | 6.7 [5.0, 8.8] | 8.6 [3.9, 15.9] | 0.39 | .533 | 1.27 [0.63, 2.58] | 1.46 [0.68, 3.16] |

| Bulimia nervosa | 0.0 | 0.0 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Externalizing domain | 2.7 [1.7, 4.1] | 6.0 [2.2, 12.5] | 2.20 | .138 | 2.16 [0.99, 4.71] | 1.97 [0.90, 4.33] |

| Disruptive behavior disorders | 2.4 [1.4, 3.7] | 6.0 [2.2, 12.5] | 2.83 | .093 | 2.42 [1.11, 5.29] | 2.23 [1.01, 4.96] |

| Other substance use disorders | 0.3 [0.1, 1.0] | 0.0 | 0.51 | .474 | NA | NA |

| Either internalizing or externalizing | 13.0 [10.6, 15.7] | 15.5 [8.8, 24.2] | 0.38 | .539 | 1.20 [0.70, 2.07] | 1.18 [0.68, 2.05] |

Note. CUD = carnnabis use disorder. CI95 = 95% confidence interval; NA = not analyzed as predictors due to insufficient period prevalence rates. A value of 0.0 indicates the absence of diagnosed cases within the referenced developmental period. Statistically significant hazard ratios are bolded. Adjusted analyses control for variables in Table 1 and other psychopathology within the same developmental period. Childhood was defined as ages 8.0 to 12.9, adolescence was defined as ages 13.0 to 17.9, and early adulthood was defined as ages 18.0 to 30.0.

The proportions of participants with either internalizing or externalizing disorders during childhood were comparable among those without and with initial CUD onsets during early adulthood (13.0% and 15.5%, respectively; LR χ2 = 0.38, p = .539). Rates of childhood internalizing and externalizing disorders, at both the superordinate domain and subdomain levels, similarly did not significantly differ between those without and with initial CUD onsets during early adulthood in any analysis (Table 3).

Adolescent internalizing and externalizing disorders as predictors of CUD onset during early adulthood

The upper right half of Table 3 presents unadjusted and adjusted analyses that evaluated the utility of internalizing and externalizing domains as proximal and distal predictors of early adult CUD onset. Reported under the unadjusted analysis heading of Table 3 are the total effects associated with adolescent psychiatric disorder domains. As indicated in the table, a diagnosis of either internalizing or externalizing domain psychopathology during adolescence significantly predicted CUD onset during early adulthood (HR [CI95] = 1.91 [1.22, 2.98]).

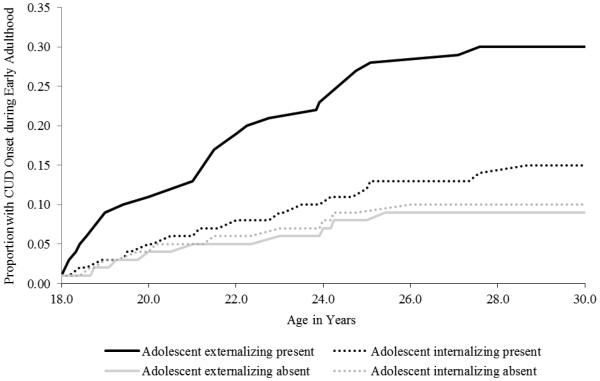

When analyzed separately from externalizing disorders, the internalizing superordinate domain and associated subdomains did not significantly predict CUD onset. Externalizing domain disorders between ages 13.0 and 17.9, however, were significant predictors of early adult CUD onset (HR [CI95] = 3.60 [2.20, 5.88]). This finding indicates that those with externalizing disorder histories during adolescence had a 3.6 times greater odds of being diagnosed with a CUD during any month-length interval within the early adult developmental period when compared to those without such histories. Cumulative hazard functions for CUD onset during early adulthood by psychopathology domain during adolescence are presented in Figure 2. When the two subdomains of externalizing psychopathology during adolescence were separately modeled, each emerged as a significant predictor of index CUD episodes during early adulthood (for disruptive behavior disorders: HR [CI95] = 3.47 [1.91, 6.31]; for other SUDs: HR [CI95] = 3.68 [2.04, 6.62]).

Figure 2.

Cumulative hazard functions for CUD onset during early adulthood (ages 18.0 to 29.9) by psychopathology domain during adolescence (ages 13.0 to 17.9).

Under the adjusted analysis heading of Table 3, we reported the additive effects of individual psychiatric disorder domains after variance associated with putative confounders and other domain psychopathology was controlled. When compared to unadjusted findings, adjusted effects were similar or smaller, but the pattern of statistical significance remained the same as that observed for unadjusted analyses.

Childhood internalizing and externalizing disorders as predictors of CUD onset during early adulthood

The lower right portion of Table 3 reports data on the association of childhood psychopathology and time to initial CUD onset during early adulthood. Reported under the unadjusted analysis heading of Table 3 are the total effects of childhood disorder domains in predicting early adult CUD onset. As indicated in Table 3, the predictive utility of internalizing and externalizing superordinate domains between ages 8.0 and 12.9, separately or in combination, did not achieve statistical significance, although externalizing domain disorders alone between ages 8.0 and 12.9 approached statistical significance (HR [CI95] = 2.16 [0.99, 4.71], p = .054). The disruptive behavior disorders subdomain of externalizing disorders, however, significantly predicted CUD onsets during early adulthood (HR [CI95] = 2.42 [1.11, 5.29], p< .05).

Under the adjusted analysis heading of Table 3, we reported the additive effects of individual childhood psychiatric disorder domains after variance associated with putative confounders and other domain psychopathology within the same developmental period was controlled. The adjusted effects were comparable to the unadjusted findings. When the significant adjusted effect for childhood disruptive behavior disorders was reevaluated following the additional control of internalizing and externalizing domain psychopathology during the adolescent developmental period, disorders from this subdomain were no longer significant unique predictors of early adult CUD onset (HR [CI95] = 1.22 [0.53, 2.83]).

Gender Moderation

Gender was evaluated as a moderator of the association between, separately, internalizing and externalizing psychopathology during childhood in predicting CUD onset during adolescence. Gender was similarly evaluated as a moderator of the association between internalizing and externalizing psychopathology during childhood and adolescence and CUD onset in the early adult onset group. Gender did not emerge as a significant moderator in any analysis (all ps ≥ .150).

Discussion

We investigated the developmental pathways that constitute a heighted risk for future CUDs during two adjoining developmental periods when the risk for cannabis initiation and initial CUD onset is greatest: adolescence and early adulthood. Our research emphasized the predictive utility of indicants of internalizing and externalizing liabilities that, when observed, are thought to not only signal a heighted risk for future CUDs but also suggest common core processes that underlie sets of related disorders (Kessler et al., 2011; Krueger, 1999; Vanyukov et al., 2012; Zucker et al., 2008).

Findings from the present research indicate that the externalizing domain is as relevant to the prediction of index CUD episode rates within units of time during early adulthood as it is for episodes that emerge during adolescence. Furthermore, externalizing psychopathology remained a robust prospective predictor of time to index CUD episode onset after demographic variables, participant family characteristics, and internalizing psychopathology were statistically controlled. Consistent with earlier studies which demonstrated that effects due to early life risk factors (distal influences) are often attenuated or eliminated once later life risk factors (proximal influences) are taken into account (Blanco et al., 2014; van den Bree and Pickworth, 2005), we found in adjusted analyses that adolescent but not childhood externalizing psychopathology were significant and moderately strong predictors of time to CUD onset within the early adulthood developmental period.

We found no evidence that internalizing psychopathology was a significant risk or protective factor related to the development of CUDs during adolescence or early adulthood. Rather, our observations are consistent with other findings (Tarter et al., 2008) that internalizing features are unrelated to CUD onset risk through age 30 regardless of the developmental period within which the index episode occurs. We similarly found no evidence of gender moderation in any of the primary analyses, which suggests that the internalizing and externalizing risk factors operate similarly for male and female participants.

Homotypic comorbidity between the externalizing disorders is substantial (Farmer et al., 2013b; Krueger & Markon, 2006; Lahey et al., 2008), and can be attributed to a shared liability that is manifested as impulsivity or behavioral disinhibition (Beauchaine & McNulty, 2013; Iacono, Malone, & McGue, 2006). Common core processes likely include those associated with deficiencies in the functioning of mesolimbic dopamine networks (Beauchaine & McNulty, 2013). Low basal dopamine activity is associated with an increased risk for use and abuse of dopamine agonist drugs (Laine et al., 2001; Martin-Soelch et al., 2001), with cannabis being among those that facilitates dopamine release (Bussong et al., 2009). When viewed from this context, cannabis abuse could be regarded as an “attribute” or manifestation of the externalizing liability (Vanyukov et al., 2012) that, in turn, enhances or amplifies existing externalizing propensities, partially as a result of cannabis’ compromising effects on dopamine-related functions over time (Koob & LeMoal, 2008).

Although the present study has several strengths, there are also limitations that suggest caution in the interpretation of study findings. Study strengths include OADP’s longitudinal study design. Longitudinal studies allow for more accurate investigations of temporal relations between various psychiatric antecedents and later CUDs. Childhood and early adolescent diagnostic data in the present research, however, were based on retrospective assessments collected at T1. Retrospective assessments are known to introduce recall-related biases that generally favor the under-reporting of psychopathology (Moffitt et al., 2010). The low base rates of certain disorders also precluded an examination of disorder-specific predictive association with CUD onset. This study was also limited by its emphasis on predictors of index CUD episodes during adolescent and early adult developmental periods. To our knowledge, internalizing and externalizing psychopathology have not been evaluated as predictors of index CUD episodes with onsets after age 30. With respect to alcohol use disorders, genetic pathways associated with adolescent and early adult onset of alcohol dependence disorder appear to differ from alcohol dependence episodes that occur after age 30 (Kendler, Garner, & Dick, 2011). The extent to which the present findings generalize to cases with CUD onsets after age 30 is uncertain. Finally, this study did not consider disorder severity or duration in the prediction models. These features of psychiatric disorders might further contribute to the prediction of CUD onsets within the developmental periods examined.

Future Directions

The common liability model (e.g., Vanyukov et al., 2012) suggests that environmental risk factors or underlying mechanisms are largely overlapping among highly comorbid substance use disorders and other psychiatric disorders. Indicators of the externalizing liability emerged as robust proximal predictors of CUD onset during adolescence and early adulthood in the present research. From a prevention perspective, findings presented here suggest that altering malleable environmental factors that contribute to or maintain externalizing tendencies (Bayer et al., 2011; Deater-Deckard, Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, 1998; Zucker et al., 2008) may substantially reduce the risk of subsequent CUDs. The externalizing liability, however, is a complex trait that encompasses a broad range of psychiatric disorders, personality features, and behavioral tendencies (Farmer et al., 2009; Krueger et al., 2002; Lahey et al., 2008) that are, in turn, predicted by common sets of environmental and biological risk factors (Kilpatrick et al., 2000; Shelton et al., 2007). Future research might seek to establish which mechanisms or core processes associated with the externalizing liability are most strongly associated with the progression of cannabis initiation to CUDs, and from time-limited CUD episodes to more chronic or enduring forms of CUD.

Although findings from the present research are generally supportive of the externalizing liability as a moderate risk factor, not all instances of CUD were explained by externalizing psychopathology. The significant proportion of disorder-free individuals in earlier developmental periods who subsequently developed CUDs suggests that psychopathology or externalizing liability theoretical frameworks, as organizing or explanatory models of the progression of cannabis experimentation to CUD, have limited predictive utility for identifying at-risk individuals. Additional work is clearly needed on the identification of mechanisms involved in the development of CUDs among those without significant externalizing histories. The identification of subgroups of persons with CUD histories may, in turn, suggest tailored interventions that better address the needs and characteristics of subgroup members.

Because of the apparent limited explanatory power of internalizing and externalizing liability models for predicting CUD onset, multiple developmental pathways are suggested, and comprehensive models of CUD development must therefore consider a broader range of variables than were investigated here. Variables that have been shown to be associated with an elevated risk for cannabis use or CUD are parent (Andrews, Hops, & Duncan, 1997), sibling (Brook, Zhang, Koppel, & Brook, 2008) and peer (Creemers et al., 2010) cannabis use, as well as lower community cohesiveness (Lin, Witten, Casswell, & You, 2012). In addition to social context, personal factors such as deficits in social skills are known risk factors for early onset cannabis use (Griffith-Lendering et al., 2011a; Hampson, Tildesley, Andrews, Luyckx, & Mroczek, 2010). Explanatory models and interventions that take into account the social environment and the individual’s ability to effectively interact with its members may therefore be especially beneficial for informing theory and reducing future risk.

Acknowledgements

National Institutes of Health grants MH40501, MH50522, and DA12951 to Peter M. Lewinsohn and R01DA032659 to Richard F. Farmer and John R. Seeley supported this research. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Initial CUD onsets before age 13 are rare (Boden, Fergusson, & Horwood, 2006; Chen & Kandel, 1995; Wittchen et al., 2007). To evaluate prospective associations between childhood psychopathology and later CUD onset, 12 cases with initial CUD onsets before age 13 were excluded from analyses involving predictors of onset (Tables 2 and 3). These participants, however, were included in analyses of demographic factors related to CUD onset (Table 1), as these data were analyzed without reference to any specific developmental period.

An assumption of Cox PH models is the absence of a significant time–by–predictor interaction. We initially included time-by-predictor interaction terms in each Cox model evaluated, and observed no instance where the interaction term was statistically significant. Interaction terms were consequently removed and the models rerun, with data from these latter analyses reported. Significant predictor effects, when observed, should therefore be regarded as consistent across the full developmental period examined rather than limited to a discrete portion of the interval.

In a series of additional analyses involving these data as well as those associated with index CUD onsets during early adulthood, we examined whether comorbidity within and across domains added significant information to the prediction of time to CUD onset beyond the consideration of “any externalizing” or “any internalizing.” These analyses, available from the first author, indicated that the consideration of disorder comorbidity did not account for significant additional variance in the prediction of CUD onset with the exception of models where internalizing disorders were the target predictor and externalizing disorders were included among the comorbid conditions considered. Extending prediction models to include consideration of comorbidity, therefore, does not change or otherwise modify our findings presented in Tables 2 and 3 or our conclusions about the data.

The homogeneity of regression assumption was tested prior to performing each adjusted time-to-event analysis. In each instance, the effect of the interaction term was non-significant, and the term was subsequently removed from the final model.

References

- Achenbach TM. The classification of children's psychiatric symptoms: A factor-analytic study. Psychological Monographs. 1966;80 doi: 10.1037/h0093906. Whole No. 615. doi: 10.1037/h0093906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal A, Lynskey MT. Does gender contribute to heterogeneity in criteria for cannabis abuse and dependence? Results from the national epidemiological survey on alcohol and related conditions. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;88:300–307. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.10.003. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal A, Lynskey MT, Bucholz KK, Madden PA, Heath AC. Correlates of cannabis initiation in a longitudinal sample of young women: The importance of peer influences. Preventive Medicine. 2007;45:31–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.04.012. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews JA, Hops H, Duncan SC. Adolescent modeling of parent substance use: The moderating effect of the relationship with the parent. Journal of Family Psychology. 1997;11:259–270. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.11.3.259. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.11.3.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer JK, Ukoumunne OC, Lucas N, Wake M, Scalzo K, Nicholson JM. Risk factors for childhood mental health symptoms: national longitudinal study of Australian children. Pediatrics. 2011;128:e865–79. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0491. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-0491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchaine TP, McNulty T. Comorbidities and continuities as ontogenic processes: Toward a developmental spectrum model of externalizing psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology. 2013;25:1505–1528. doi: 10.1017/S0954579413000746. doi: 10.1017/S0954579413000746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco C, Rafful C, Wall MM, Ridenour TA, Wang S, Kendler KS. Towards a comprehensive developmental model of cannabis use disorders. Addiction. 2014;109:284–294. doi: 10.1111/add.12382. doi: 10.1111/add.12382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boden JM, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Illicit drug use and dependence in a New Zealand birth cohort. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;40:156–163. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01763.x. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossong MG, van Berckel BN, Boellaard R, Zuurman L, Schuit RC, Windhorst AD, Kahn RS. Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol induces dopamine release in the human striatum. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;34(3):759–766. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.138. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Lee JY, Finch SJ, Koppel J, Brook DW. Psychosocial factors related to cannabis use disorders. Substance Abuse. 2011;32:242–251. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2011.605696. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2011.605696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Zhang C, Koppel J, Brook DW. Pathways from earlier marijuana use in the familial and non-familial environments to self-marijuana use in the fourth decade of life. American Journal on Addictions. 2008;17:497–503. doi: 10.1080/10550490802408373. doi: 10.1080/10550490802408373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Schmidt NB, Lang AR, Small JW, Schlauch RC, Lewinsohn PM. Specificity of social anxiety disorder as a risk factor for alcohol and cannabis dependence. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2008;42:230–239. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2007.01.002. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callas P, Pastides H, Hosmer D. Empirical comparisons of proportional hazards, poisson, and logistic regression modeling of occupational cohort data. American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 1998;33:33–47. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0274(199801)33:1<33::aid-ajim5>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers WJ, Puig-Antich J, Hirsch M, Paez P, Ambrosini PJ, Tabrizi MA, Davies M. The assessment of affective disorders in children and adolescents by semistructured interview: Test-retest reliability of the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children, Present Episode version. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1985;42:696–702. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790300064008. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790300064008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, Kandel DB. The natural history of drug use from adolescence to the mid-thirties in a general population sample. American Journal of Public Health. 1995;85:41–47. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.1.41. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.85.1.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colder CR, Scalco M, Trucco EM, Read JP, Lengua LJ, Wieczorek WF, Hawk LW., Jr Prospective associations of internalizing and externalizing problems and their co-occurrence with early adolescent substance use. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2013;41:667–677. doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9701-0. doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9701-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Erkanli A, Federman E, Angold A. Development of psychiatric comorbidity with substance abuse in adolescents: Effects of timing and sex. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1999;28:298–311. doi: 10.1207/S15374424jccp280302. doi: 10.1207/S15374424jccp280302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creemers HE, Dijkstra JK, Vollebergh WA, Ormel J, Verhulst FC, Huizink AC. Predicting life-time and regular cannabis use during adolescence; the roles of temperament and peer substance use: the TRAILS study. Addiction. 2010;105:699–708. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02819.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02819.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS. Multiple risk factors in the development of externalizing behavior problems: Group and individual differences. Development and Psychopathology. 1998;10(03):469–493. doi: 10.1017/s0954579498001709. doi: 10.1017/S0954579498001709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L, Coffey C, Romaniuk H, Swift W, Carlin JB, Hall WD, Patton GC. The persistence of the association between adolescent cannabis use and common mental disorders into young adulthood. Addiction. 2013;108:124–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.04015.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.04015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer RF, Kosty DB, Seeley JR, Duncan SC, Lynskey MT, Rohde P, Lewinsohn PM. Natural course of cannabis use disorders. Psychological Medicine. 2015;45:63–72. doi: 10.1017/S003329171400107X. doi: 10.1017/S003329171400107X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer RF, Kosty DB, Seeley JR, Olino TM, Lewinsohn PM. Aggregation of lifetime axis I psychiatric disorders through age 30: Incidence, predictors, and associated psychosocial outcomes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2013a;122:573–586. doi: 10.1037/a0031429. doi: 10.1037/a0031429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer RF, Seeley JR, Kosty DB, Lewinsohn PM. Refinements in the hierarchical structure of externalizing psychiatric disorders: Patterns of lifetime liability from mid-adolescence through early adulthood. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118:699–710. doi: 10.1037/a0017205. doi: 10.1037/a0017205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer RF, Seeley JR, Kosty DB, Olino TM, Lewinsohn PM. Hierarchical organization of axis I psychiatric disorder comorbidity through age 30. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2013b;54:523–532. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2012.12.007. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Does cannabis use encourage other forms of illicit drug use? Addiction. 2000;95:505–520. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.9545053.x. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.9545053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Lynskey MT. Structure of DSM-III-R criteria for disruptive behaviors: Confirmatory factor models. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1994;33:1145–1155. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199410000-00010. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199410000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Ridder EM. Conduct and attentional problems in childhood and adolescence and later substance use, abuse and dependence: Results of a 25-year longitudinal study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;88:S14–S26. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.011. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Swain-Campbell N. Cannabis use and psychosocial adjustment in adolescence and young adulthood. Addiction. 2002;97:1123–1135. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00103.x. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured clinical interview for Axis I DSM-IV disorders, Non-patient edition. New York: Biometrics Research Department. 1994 [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Compton W, Kaplan K. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: Results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61:807–816. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.8.807. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.8.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith-Lendering MF, Huijbregts SC, Huizink AC, Ormel H, Verhulst FC, Vollebergh WA, Swaab H. Social skills as precursors of cannabis use in young adolescents: a TRAILS study. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2011a;40:706–714. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2011.597085. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2011.597085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith-Lendering MFH, Huijbregts SCJ, Mooijaart A, Vollebergh WAM, Swaab H. Cannabis use and development of externalizing and internalizing behaviour problems in early adolescence: A TRAILS study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011b;116:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.11.024. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampson SE, Tildesley E, Andrews JA, Luyckx K, Mroczek DK. The relation of change in hostility and sociability during childhood to substance use in mid adolescence. Journal of Research in Personality. 2010;44:103–114. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2009.12.006. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayatbakhsh MR, McGee TR, Bor W, Najman JM, Jamrozik K, Mamun AA. Child and adolescent externalizing behavior and cannabis use disorders in early adulthood: an Australian prospective birth cohort study. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33:422–438. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.10.004. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry B, Feehan M, McGee R, Stanton W, Moffitt TE, Silva P. The importance of conduct problems and depressive symptoms in predicting adolescent substance use. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1993;21:469–480. doi: 10.1007/BF00916314. doi: 10.1007/BF00916314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacono WG, Malone SM, McGue M. Behavioral disinhibition and the development of early-onset addiction: Common and specific influences. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2008;4:325–348. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.4.022007.141157. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.4.022007.141157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use (1975–2012): Volume I. Secondary school students. Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan; Ann Arbor: 2013. doi: [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, Chen K. Types of marijuana users by longitudinal course. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2000;61:367–378. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel D, Yamaguchi K. From beer to crack: Developmental patterns of drug involvement. American Journal of Public Health. 1993;83:851–855. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.6.851. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.83.6.851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller MB, Lavori PW, Friedman B, Nielsen E, Endicott J, McDonald-Scott PA. The Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation: A comprehensive method for assessing outcome in prospective longitudinal studies. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1987;44:540–548. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800180050009. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800180050009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Gardner C, Dick DM. Predicting alcohol consumption in adolescence from alcohol-specific and general externalizing genetic risk factors, key environmental exposures and their interaction. Psychological Medicine. 2011;41:1507–1516. doi: 10.1017/S003329171000190X. doi: 10.1017/S003329171000190X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Ormel J, Petukhova M, McLaughlin KA, Green JG, Russo LJ, Üstün TB. Development of lifetime comorbidity in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2011;68:90–100. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.180. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Acierno R, Saunders B, Resnick HS, Best CL, Schnurr PP. Risk factors for adolescent substance abuse and dependence: data from a national sample. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:19–30. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.1.19. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.68.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King SM, Iacono WG, McGue M. Childhood externalizing and internalizing psychopathology in the prediction of early substance use. Addiction. 2004;99:1548–1559. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00893.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Le Moal M. Addiction and the brain antireward system. Annual Review of Psycholology. 2008;59:29–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093548. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF. The structure of common mental disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1999;56:921–926. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.10.921. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.10.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Hicks BM, Patrick CJ, Carlson SR, Iacono WG, McGue M. Etiologic connections among substance dependence, antisocial behavior and personality: Modeling the externalizing spectrum. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:411–434. doi: 10.1037//0021-843X.111.3.411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Markon KE. Reinterpreting comorbidity: A model-based approach to understanding and classifying psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2006;2:111–133. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.2.022305.095213. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.2.022305.095213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Rathouz PJ, Van Hulle C, Urbano RC, Krueger RF, Applegate B, Waldman ID. Testing structural models of DSM-IV symptoms of common forms of child and adolescent psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:187–206. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9169-5. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9169-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laine TPJ, Ahonen A, Räsänen P, Tiihonen J. Dopamine transporter density and novelty seeking among alcoholics. Journal of Addictive Diseases. 2001;20(4):95–100. doi: 10.1300/j069v20n04_08. doi: 10.1300/J069v20n04_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Hops H, Roberts RE, Seeley JR, Andrews JA. Adolescent psychopathology: I. Prevalence and incidence of depression and other DSM-III-R disorders in high school students. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1993;102:133–144. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.102.1.133. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.102.1.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin EY, Witten K, Casswell S, You RQ. Neighbourhood matters: Perceptions of neighbourhood cohesiveness and associations with alcohol, cannabis and tobacco use. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2012;31:402–412. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2011.00385.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2011.00385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Soelch C, Leenders KL, Chevalley AF, Missimer J, Künig G, Magyar S, Schultz W. Reward mechanisms in the brain and their role in dependence: evidence from neurophysiological and neuroimaging studies. Brain Research Reviews. 2001;36(2):139–149. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(01)00089-3. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0173(01)00089-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslowsky J, Schulenberg JE, Zucker RA. Influence of conduct problems and depressive symptomatology on adolescent substance use: Developmentally proximal versus distal effects. Developmental Psychology. 2014;50:1179–1189. doi: 10.1037/a0035085. doi: 10.1037/a0035085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller-Johnson S, Lochman JE, Coie JD, Terry R, Hyman C. Comorbidity of conduct and depressive problems at sixth grade: Substance use outcomes across adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1998;26:221–232. doi: 10.1023/a:1022676302865. doi: 10.1023/A:1022676302865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Kokaua J, Milne BJ, Polanczyk G, Poulton R. How common are common mental disorders? Evidence that lifetime prevalence rates are doubled by prospective versus retrospective ascertainment. Psychological Medicine. 2010;40:899–909. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709991036. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709991036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orvaschel H, Puig-Antich J, Chambers WJ, Tabrizi MA, Johnson R. Retrospective assessment of prepubertal major depression with the Kiddie-SADS-E. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry. 1982;21:392–397. doi: 10.1016/s0002-7138(09)60944-4. doi: 10.1016/S0002-7138(09)60944-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paton S, Kessler R, Kandel D. Depressive mood and adolescent illicit drug use: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Genetic Psychology. 1977;131:267–289. doi: 10.1080/00221325.1977.10533299. doi: 10.1080/00221325.1977.10533299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkonigg A, Goodwin RD, Fiedler A, Behrendt S, Beesdo K, Lieb R, Wittchen H-U. The natural course of cannabis use, abuse, and dependence during the first decades of life. Addiction. 2008;103:439–449. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02064.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeley JR, Kosty DB, Farmer RF, Lewinsohn PM. The modeling of internalizing disorders on the basis of patterns of lifetime comorbidity: Associations with psychosocial impairment and psychiatric disorders among first–degree relatives. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2011;120:308–321. doi: 10.1037/a0022621. doi: 10.1037/a0022621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton K, Lifford K, Fowler T, Rice F, Neale M, Harold G, van den Bree M. The association between conduct problems and the initiation and progression of marijuana use during adolescence: a genetic analysis across time. Behavior Genetics. 2007;37:314–325. doi: 10.1007/s10519-006-9124-1. doi: 10.1007/s10519-006-9124-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarter RE, Kirisci L, Ridenour T, Vanyukov M. Prediction of cannabis use disorder between childhood and young adulthood using the Child Behavior Checklist. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2008;30:272–278. doi: 10.1007/s10862-008-9083-3. [Google Scholar]

- van den Bree MB, Pickworth WB. Risk factors predicting changes in marijuana involvement in teenagers. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:311–319. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.3.311. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.3.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Net JB, Janssens AW, Eijkemans MC, Kastelein JP, Sijbrands EG, Steyerberg EW. Cox proportional hazards models have more statistical power than logistic regression models in cross-sectional genetic association studies. European Journal of Human Genetics. 2008;16:1111–1116. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2008.59. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2008.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanyukov MM, Tarter RE, Kirillova GP, Kirisci L, Reynolds MD, Kreek MJ, Ridenour TA. Common liability to addiction and “gateway hypothesis”: Theoretical, empirical and evolutionary perspective. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2012;123:S3–S17. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.12.018. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verweij KJ, Zietsch BP, Lynskey MT, Medland SE, Neale MC, Martin NG, Vink JM. Genetic and environmental influences on cannabis use initiation and problematic use: A meta- analysis of twin studies. Addiction. 2010;105:417–430. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02831.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02831.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen HU, Fröhlich C, Behrendt S, Günther A, Rehm J, Zimmermann P, Perkonigg A. Cannabis use and cannabis use disorders and their relationship to mental disorders: a 10-year prospective-longitudinal community study in adolescents. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;88:S60–S70. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.013. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolter KM. Introduction to variance estimation. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RA, Donovan JE, Masten AS, Mattson ME, Moss HB. Early developmental processes and the continuity of risk for underage drinking and problem drinking. Pediatrics. 2008;121(Suppl. 4):S252–S272. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2243B. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2243B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]