Abstract

Research and theory suggest that romantic couple members are motivated to drink to cope with interpersonal distress. Additionally, this behavior and its consequences appear to be differentially associated with insecure attachment styles. However, no research has directly examined drinking to cope that is specific to relationship problems, or with relationship-specific drinking outcomes. Based on alcohol motivation and attachment theories, the current study examines relationship-specific drinking-to-cope processes over the early years of marriage. Specifically, it was hypothesized that drinking to cope with a relationship problem would mediate the associations between insecure attachment styles (i.e., anxious and avoidant) and frequencies of drinking with and apart from one’s partner and marital alcohol problems in married couples. Multilevel models were tested via the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model using reports of both members of 470 couples over the first 9 years of marriage. As expected, relationship-specific drinking-to-cope motives mediated the effects of actor anxious attachment on drinking apart from one’s partner and on marital alcohol problems, but, unexpectedly, not on drinking with the partner. No mediated effects were found for attachment avoidance. Results suggest that anxious (but not avoidant) individuals are motivated to use alcohol to cope specifically with relationship problems in certain contexts, which may exacerbate relationship difficulties associated with attachment anxiety. Implications for theory and future research on relationship-motivated drinking are discussed.

Keywords: alcohol, drinking motives, marriage, romantic relationships, attachment styles

Alcohol use is an integral part of many romantic couples’ everyday lives. However, the motivational processes underlying relationship drinking are still unclear. Research suggests that at least one reason why individuals use alcohol in their relationship is to cope with and manage interpersonal distress (e.g., Rodriguez, Knee, & Neighbors, 2014), which is considered maladaptive (Cooper, Frone, Russell, & Mudar, 1995). Associated with this behavior are individuals’ attachment styles, which reflect characteristic ways of managing interpersonal distress in relationships (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2003). Insecurely attached (i.e., anxious and avoidant) individuals are more likely than secure individuals to drink to cope (e.g., Brennan & Shaver, 1995). Anxiously attached individuals in particular may experience greater alcohol-related problems as a result of drinking-to-cope compared to their avoidant counterparts, and that is not attributable to their quantity consumed (Molnar, Sadava, DeCourville, & Perrier, 2010). However, no research has yet examined relationship-specific drinking-to-cope (i.e., drinking to assuage negative emotions in response to a stressful or upsetting relationship problem), or examined this factor as a mediating mechanism of insecure attachment styles in relationship-specific alcohol use processes. This is an important distinction given that alcohol motivation theory (Cooper, Kuntsche, Levitt, Barber, & Wolf, in press; Cox & Klinger, 1988; Leonard & Mudar, 2004) emphasizes examining drinking motivations that are situated in specific domains (e.g., romantic relationships). Therefore, guided by alcohol motivation and attachment theories, the current study examined relationship-specific drinking-to-cope as a mediator of insecure attachment styles to predict the frequency of relationship-drinking contexts (i.e., drinking with compared to apart from one’s partner) and rates of marital alcohol problems (i.e., relationship problems perceived by oneself or one’s partner as a result of one’s drinking) over time in the early years of marriage.

Drinking to Cope with Interpersonal Distress and the Role of Attachment Styles

One reason that individuals are motivated to use alcohol is to cope with negative emotions associated with interpersonal distress (Cooper et al., 1995). A natural, yet understudied, extension of this behavior is drinking to cope with interpersonal distress associated with one’s partner in the domain of romantic relationships. Research demonstrates that daily drinking behaviors in relationships increase following relationship problems and distress (DeHart, Tennen, Armeli, Todd, & Affleck, 2008; Levitt & Cooper, 2010; Mohr et al., 2001). All of these studies, although not assessing drinking-to-cope explicitly, are consistent in suggesting that individuals are motivated to drink to regulate negative emotions associated with relationship distress. They are also consistent in suggesting that some individuals may view drinking-to-cope as an adaptive mechanism that can help improve the quality of their relationship. However, drinking-to-cope is considered to be a maladaptive motive in that it is associated with higher rates of alcohol problems relative to other drinking motives after accounting for rates of consumption (Cooper et al., 1995; Mickelson, Kessler, & Shaver, 1997; Sher & Grekin, 2007). In one of the few studies to directly examine this phenomenon in relationships, Rodriguez et al. (2014) recently showed that drinking-to-cope mediated the association between relationship distress and alcohol problems, and that these associations may be stronger among those low in relationship-contingent self-esteem. However, it is still unclear how these processes might differ when examining drinking-to-cope and drinking outcome variables that are specific to the relationship, or for whom these processes might differ.

Attachment theory provides a foundation from which to examine emotion regulation strategies in romantic relationships, including drinking-to-cope. Individuals in romantic relationships hold mental representations, or working models, of themselves and of their partner as an attachment figure (Bowlby, 1969/1982). Differences in these cognitions, and corresponding, strategic behaviors used to manage distress, closeness, and felt security in relationships, constitute individuals’ attachment styles (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2003). These styles are commonly thought of as dimensions of anxiety (i.e., one’s model of self) and avoidance (i.e., one’s model of others). Attachment anxiety is associated with hyperactivation of the attachment system, including strong desires for closeness and reassurance, whereas attachment avoidance is associated with hypoactivation of the attachment system, including a desire to maintain independence and emotional distance (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2003). Mikulincer and Shaver (2007) highlight that a key component of the attachment system is the ongoing assessment of the utility of context-specific behaviors that are used in the pursuit of relationship goals. We posit that drinking-to-cope with relationship problems is one such context-specific behavior that insecure individuals may use to manage distress and restore feelings of security in relationships.

Previous research shows that attachment anxiety is positively associated with drinking-to-cope in general outside of relationship contexts after accounting for average levels of alcohol consumption (Brennan & Shaver, 1995; Kassell, Wardle, & Roberts, 2007; McNally, Palfai, Levine, & Moore, 2003; Molnar, Sadava, DeCourville, & Perrier, 2010). However, Molnar et al. (2010) found that general drinking-to-cope mediated the association between attachment anxiety and greater alcohol problems above and beyond the effects of average consumption. This result suggests that drinking-to-cope among anxiously attached individuals might not have the anticipated or desired outcomes they expect (Leonard & Mudar, 2004), and that they might experience relationship-specific alcohol problems as a function of drinking to cope with relationship problems. In the context of romantic relationships, attachment anxiety is also positively associated with expectancies for alcohol’s relationship-enhancing effects (Leonard & Mudar, 2004). By extension, anxious individuals may view drinking to cope with their partner as a relationship-enhancing strategy (despite its maladaptive nature), and in turn be motivated to drink to cope with relationship problems in a strategic effort to reduce distress and restore felt security in their relationship.

In contrast, research findings are not as consistent for attachment avoidance compared to attachment anxiety. Some studies show positive associations between attachment avoidance and drinking-to-cope (Brennan & Shaver, 1995; Molnar et al., 2010), whereas others do not (Kassel et al., 2007; McNally et al., 2003). Although none of these studies were in relationship contexts, attachment avoidance has been associated with increased alcohol consumption in married couples (Senchak & Leonard, 1992). Thus, there is reason to believe that avoidant individuals may also drink to cope with relationship distress, but that they will likely drink apart from their partner to regulate their emotions considering their tendencies toward distance and independence..

Relationship-Motivated Alcohol Use

In order to understand relationship-motivated alcohol use processes, it is crucial to examine the factors in these processes as they pertain specifically to one’s relationship. A growing body of literature suggests that there are unique antecedents and consequences surrounding drinking in relationships (e.g., Levitt & Cooper, 2010; Levitt & Leonard, 2013; Levitt, Derrick, & Testa, 2014). Key among these variables is the context in which drinking occurs and expectancies for relationship effects of alcohol. Research indicates that the relationship-drinking context is important, in that drinking with one’s partner appears to be adaptive, whereas drinking apart appears to be maladaptive (Homish & Leonard, 2005; Levitt & Cooper, 2010; Levitt et al., 2014). Furthermore, research demonstrates that drinking behaviors in relationships are associated with relationship-specific expectancies for alcohol’s effects. These expectancies, such as intimacy enhancement and power/assertiveness, are also differentially associated with patterns of drinking in relationships, relationship-drinking contexts, and relationship functioning outcomes (Derrick et al., 2010; Levitt & Leonard, 2013; Levitt et al., 2014). Considering that drinking motives are believed to be the final causal pathway between alcohol expectancies and drinking behaviors (Cooper et al., in press; Cox & Klinger, 1988), these findings as a whole consistently suggest relationship-motivated alcohol use processes despite not directly measuring drinking motives. Relationship-specific drinking motives have yet to be directly tested. Nevertheless, it is plausible to infer (based on attachment and alcohol motivation theories) that insecurely attached individuals will expect alcohol to assuage negative emotions associated with a relationship problem, and will be motivated to drink to cope as a result. In turn, insecurely attached individuals will differentially engage in drinking with versus apart from their partner, and may experience marital alcohol problems as a result.

The Current Study

The current study examined relationship-specific drinking-to-cope as a mediator of insecure attachment styles on the frequency of drinking in specific relationship contexts and on relationship-specific alcohol problems. Based on previous literature and theory, we hypothesized that attachment anxiety would be directly associated with greater frequency of drinking with one’s partner, whereas it would be directly associated with less frequent drinking apart from one’s partner. In contrast, we hypothesized that attachment avoidance would be directly associated with greater frequency of drinking apart from one’s partner, and less frequent drinking-with-partner. Both attachment anxiety and avoidance were hypothesized to be associated with greater drinking to cope with relationship problems, and that drinking-to-cope would mediate the hypothesized effects of attachment anxiety and avoidance, respectively. Additionally, we hypothesized that insecure attachment styles, particularly attachment anxiety, would predict greater marital alcohol problems as mediated by relationship-specific drinking-to-cope. Although specific hypotheses are not offered, we also examine effects of partner attachment styles, interactions among attachment styles within and between partners, and gender differences in these effects. To our knowledge, the current study is the first to examine this mediational process in both members of romantic couples, and to directly assess a domain of relationship-specific drinking motives.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Participants were both members of 634 couples in the Adult Development Study, which independently assessed alcohol involvement and marital functioning for each couple member over 6 waves across the first 9 years of marriage. Couples were initially recruited from the Buffalo, NY, community from 1996-1999 while applying for their marriage licenses. Additional information on the original sample, sampling procedure, and differences between eligible and ineligible couples is presented elsewhere (Leonard & Mudar, 2004). The current study analyzes data from a subsample of 470 couples in which both members had consumed alcohol in the past year at the time of marriage. Individuals in this subsample were 27.53 (SD = 5.59) years old on average, and 70% Caucasian at baseline. Couple retention rates in this subsample were adequate over time: wave 2, N = 430 couples (91.5% of wave 1 subsample); wave 3, N = 406 (86.4%); wave 4, N = 382 (81.3%); wave 5, N = 369 (78.5%); wave 6, N = 311 (66.2%). Additionally, no mean differences were found in key study variables (i.e., attachment styles, relationship-specific drinking-to-cope, extents of relationship-drinking contexts, and marital alcohol problems) between couples who remained in the study throughout vs. couples who dropped out of the study by wave 6.

Measures

All assessments at each wave were conducted separately for husbands and wives.

Attachment styles

Adult romantic attachment styles were assessed at each wave using Bartholomew and Horowitz’s (1991) 4-part categorical measure. Participants read four descriptive paragraphs of each attachment style (i.e., Secure, Preoccupied, Dismissing, Fearful) and rated on a 7-point scale (1 = “Not at all like me,” 7 = “Very much like me”) the extent to which they agreed with each style. Scores were then dimensionalized according to procedures outlined by Griffin and Bartholomew (1994) to make two continuous dimensions of attachment: Anxiety (reflecting one’s model of self) and Avoidance (reflecting one’s model of other), respectively, with higher scores representing greater insecure attachment. Average reports of attachment anxiety across all waves were M = 2.73 (SD = 1.00) for husbands and M = 3.04 (1.15) for wives. Average attachment avoidance across all waves was M = 3.24 (SD = 1.07) for husbands and M = 3.25 (SD = 1.09) for wives.

Alcohol consumption

Average quantity of alcohol consumed was used as a covariate to control for effects of heavy drinking. Couple members reported the typical quantity consumed of their most frequently consumed drink type (i.e., beer, wine, liquor) per drinking occasion over the past year at each wave. Responses were on a 10-point scale ranging from 1 drink to 18 or more drinks. Husbands reported consuming M = 3.92 (SD = 3.03) drinks per drinking occasion on average across all waves, whereas wives reported M = 2.79 (SD = 2.43) drinks.

Relationship-specific drinking-to-cope motives

At each interview, participants were instructed to “think about the MOST STRESSFUL OR UPSETTING problem or event that happened or was on your mind during the past 12 months that involved some aspect of your relationship with your partner” (emphases in original instructions). Participants were then asked a series of 38 items revised from common coping measures concerning how they coped with this relationship-specific problem. Participants were reminded to “respond in terms of what you actually did in response to this relationship-specific stressful situation, not in terms of how you generally behave (or would like to behave) when experiencing stress” (emphases in original instructions). Among these items were 3 items that indicated that the participant used alcohol to cope: “I used alcohol to make myself feel better,” “I drank alcohol in order to think about it less,” and “I used alcohol to help me get through it.” Items were rated on a 4-point Likert scale from 1 = “I didn’t do this at all” to 4 = “I did this a lot.” These items demonstrated excellent reliability in the current sample (average αs collapsed across all waves = .95 for husbands and .96 for wives). Reports of relationship-specific drinking-to-cope on average across all waves were M = 1.30 (SD = 0.62) for husbands and M = 1.18 (SD = 0.52) for wives.

Relationship drinking contexts

Single-item measures were used to assess the past year frequency of drinking-with-partner when both partners were drinking, and drinking when the partner was not present, respectively. Each item was scored on an 8-point Likert scale where 0 = “Not at all during the past year,” 1 = “1-4 times in the year,” 2 = “5-10 times in the year,” 3 = “About once a month,” 4 = “2-3 times a month,” 5 = “1-2 times a week,” 6 = “3-4 times a week,” and 7 = “Every day or nearly every day.” Reports of drinking-with-partner on average across all waves were M = 2.30 (SD = 1.73) for husbands and M = 2.25 (SD = 1.77) for wives, whereas reports of drinking apart from one’s partner were M = 2.27 (SD = 1.77) for husbands and M = 1.25 (SD = 1.43) for wives.

Alcohol problems

Using a 25-item measure that was created for this study based on previous measures and research (see Homish, Leonard, & Kearns-Bodkin, 2006, for more details), alcohol problems experienced in the past year were assessed at each wave. The measure assessed two subscales of marital (7 items) and non-marital (18 items) alcohol problems. The marital alcohol problems included: “hit or got into a physical fight with your partner while you were drinking,” “said harsh or cruel things to your partner while you were drinking,” and how often the spouse “complained or expressed concern about your drinking,” “hit or started a physical fight with you while you were drinking,” “got angry about your drinking or the way you behaved while you were drinking,” “avoided being around you because of your drinking,” or “excluded you from activities because of your drinking.” Examples of the non-marital alcohol problems included: “driven a car after drinking enough to be in trouble if a police officer had stopped you,” and “had the quality of your work (at home, school, or on the job) suffer because of drinking.” All items were answered on a 5-point scale with 0 = “Never happened in the past year,” to 4 = “Four or more times in the past year.” Average reliabilities collapsed across all waves were good for both subscales (marital: αs = .84 for husbands and .81 for wives; non-marital: αs = .87 for husbands and .86 for wives). Average responses across all waves for marital problems were M = 1.43 (SD = 3.57) for husbands and M = 0.68 (SD = 2.39) for wives, whereas non-marital problems were M = 2.45 (SD = 5.68) for husbands and M = 1.10 (SD = 3.59) for wives. Marital and non-marital alcohol problems were correlated across all waves (r = .76, p < .001 for husbands; r = .74, p < .001 for wives).

Data Analyses

Multilevel analyses were conducted using the Mixed procedure in SPSS (Version 22; IBM Corp., 2014) guided by the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006). Repeated measures (Level 1) were crossed between partners and nested within couple (Level 2) (Kashy & Donnellan, 2012; Laurenceau & Bolger, 2005). This method allows for missing data at Level 1. Both concurrent and lagged reports of attachment styles and relationship-specific drinking-to-cope, controlling for the lagged report of the outcome as well as continuous time (centered at baseline, and reflecting 1-year units) were used to predict each of the drinking-related outcomes. Although only within-wave associations were expected given the temporal associations among the variables (i.e., drinking-to-cope with a relationship problem at Wave 1 would only be expected to predict drinking outcomes at that wave, and not drinking outcomes at Wave 2), lagged reports of independent variables and time were controlled to rule out alternative temporal explanations of the current data (Bolger & Laurenceau, 2013).

Following guidelines by Kashy & Donnellan 2012; (see also Kenny et al., 2006), preliminary models were run to test whether men and women were empirically distinguishable in the means, variances, and covariances of the current set of variables. Data were empirically distinguishable by gender for models predicting relationship-specific drinking-to-cope (χ2diff [6] = 12.82, p = .046), drinking apart from one’s partner (χ2diff [6] = 68.35, p < .001), and marital alcohol problems (χ2diff [6] = 126.41, p < .001). However, data were not distinguishable by gender for models predicting drinking-with-partner (χ2diff [6] = 8.76, p = .188). Therefore, gender was controlled in all models except those predicting drinking-with-partner.

For each outcome, a parallel series of multilevel models were used to test the hypothesized mediational processes (Krull & MacKinnon, 2001). First, actor and partner effects of both anxious and avoidant attachment styles were estimated to predict actor reports of relationship-specific drinking-to-cope (i.e., the hypothesized mediator). Second, direct effects of actor and partner attachment styles were simultaneously estimated to predict actor reports of drinking-related outcomes in separate models for each outcome. Finally, these models were then repeated including the estimation of actor reports of relationship-specific drinking-to-cope (i.e., the mediator). All models controlled for main effects of average alcohol consumption for both actors and partners. Additionally, in the models predicting marital alcohol problems, the effects of non-marital alcohol problems were controlled. All variables were grand-mean centered, except for gender, which was dichotomous and uncentered. All terms were estimated as fixed effects with random intercept and error components.

Results

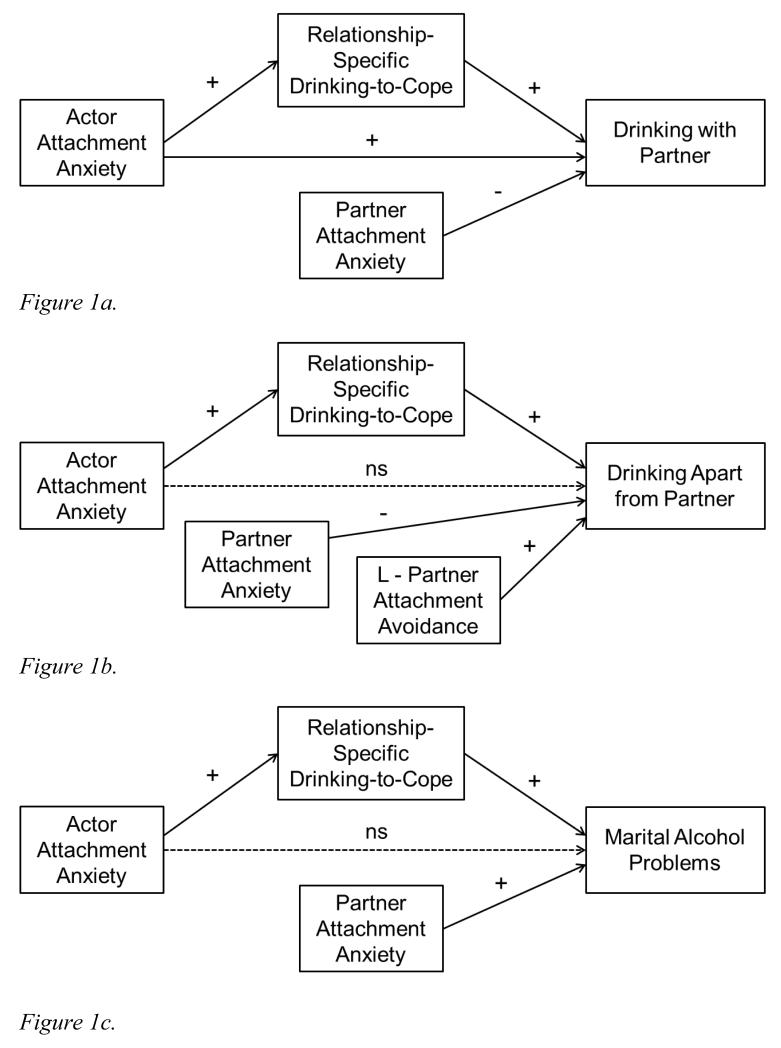

Results from all models can be seen in Table 1. Schematic summaries of results from final models are presented in Figure 1.

Table 1. Tests of Relationship-Specific Drinking-to-Cope Mediation of Attachment Styles on Drinking Outcomes.

| Relationship-Specific Drinking-to-Cope |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 |

||||||

| 95% CI |

||||||

| Predictors | b | (SE) | t | p | Lower | Upper |

| Intercept | 1.211 | (.020) | 60.407 | .000 | 1.172 | 1.251 |

| Time | .009 | (.004) | 2.490 | .013 | .002 | .016 |

| L - Prior Outcome Control | .478 | (.018) | 25.886 | .000 | .442 | .515 |

| Gender | .004 | (.021) | .194 | .846 | −.037 | .045 |

| A - Average Consumption | .036 | (.004) | 8.272 | .000 | .027 | .044 |

| P - Average Consumption | −.000 | (.004) | −.106 | .916 | −.009 | .008 |

| L - A - Anxiety | .008 | (.011) | .706 | .480 | −.013 | .029 |

| L - P - Anxiety | −.001 | (.011) | −.092 | .927 | −.022 | .020 |

| L - A - Avoidance | .003 | (.011) | .241 | .809 | −.019 | .024 |

| L - P - Avoidance | −.011 | (.011) | −1.031 | .303 | −.033 | .010 |

| A - Anxiety | .034 | (.011) | 3.088 | .002 | .012 | .055 |

| P - Anxiety | .034 | (.011) | 3.083 | .002 | .012 | .055 |

| A - Avoidance | −.007 | (.011) | −.676 | .499 | −.029 | .014 |

| P - Avoidance | −.006 | (.011) | −.555 | .579 | −.028 | .015 |

| Drinking-with-Partner, Both Partners Drinking |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 2a: Direct |

Model 3 a: Drinking-to-Cope |

|||||||||||

| 95% CI |

95% CI |

|||||||||||

| Predictors | b | (SE) | t | P | Lower | Upper | b | (SE) | t | p | Lower | Upper |

| Intercept | 2.228 | (.056) | 39.902 | .000 | 2.118 | 2.337 | 2.237 | (.056) | 40.307 | .000 | 2.128 | 2.346 |

| Time | .010 | (.012) | .902 | .367 | −.012 | .033 | .008 | (.012) | .670 | .503 | −.015 | .030 |

| L — Drinking-with-Partner | .507 | (.018) | 28.638 | .000 | .472 | .541 | .496 | (.018) | 27.872 | .000 | .461 | .531 |

| A - Average Consumption | .037 | (.011) | 3.390 | .001 | .016 | .058 | .023 | (.011) | 2.064 | .039 | .001 | .045 |

| P - Average Consumption | .032 | (.011) | 2.940 | .003 | .011 | .053 | .032 | (.011) | 2.975 | .003 | .011 | .053 |

| L - A - Anxiety | −.036 | (.029) | −1.231 | .219 | −.093 | .021 | −.042 | (.029) | −1.437 | .151 | −.099 | .015 |

| L - P - Anxiety | .012 | (.029) | .425 | .671 | −.045 | .070 | .007 | (.029) | .243 | .808 | −.050 | .064 |

| L - A - Avoidance | −.016 | (.030) | −.543 | .587 | −.074 | .042 | −.016 | (.029) | −.537 | .591 | −.074 | .042 |

| L - P - Avoidance | −.007 | (.030) | −.249 | .803 | −.066 | .051 | −.004 | (.030) | −.144 | .886 | −.062 | .054 |

| A - Anxiety | .075 | (.030) | 2.538 | .011 | .017 | .134 | .064 | (.030) | 2.154 | .031 | .006 | .122 |

| P - Anxiety | −.052 | (.030) | −1.767 | .077 | −.111 | .006 | −.063 | (.030) | −2.127 | .033 | −.121 | −.005 |

| A - Avoidance | −.048 | (.030) | −1.611 | .107 | −.107 | .010 | −.050 | (.030) | −1.664 | .096 | −.108 | .009 |

| P - Avoidance | .016 | (.030) | .523 | .601 | −.043 | .075 | .016 | (.030) | .530 | .596 | −.043 | .075 |

| L — A - Cope | n/a | .072 | (.053) | 1.361 | .174 | −.032 | .176 | |||||

| A - Cope | n/a | .175 | (.052) | 3.397 | .001 | .074 | .276 | |||||

| Drinking Apart from Partner |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 2b: Direct |

Model 3b: Drinking-to-Cope |

|||||||||||

| 95% CI |

95% CI |

|||||||||||

| Predictors | b | (SE) | t | p | Lower | Upper | b | (SE) | t | p | Lower | Upper |

| Intercept | 1.480 | (.054) | 27.160 | .000 | 1.373 | 1.587 | 1.480 | (.052) | 28.383 | .000 | 1.378 | 1.582 |

| Time | .028 | (.010) | 2.793 | .005 | .008 | .047 | .021 | (.010) | 2.223 | .026 | .002 | .040 |

| L - Drinking Apart | .471 | (.018) | 26.159 | .000 | .436 | .506 | .399 | (.019) | 21.202 | .000 | .362 | .435 |

| Gender | .435 | (.060) | 7.310 | .000 | .318 | .552 | .482 | (.058) | 8.318 | .000 | .368 | .596 |

| A - Average Consumption | .102 | (.012) | 8.638 | .000 | .079 | .126 | .074 | (.012) | 6.324 | .000 | .051 | .097 |

| P - Average Consumption | .030 | (.011) | 2.638 | .008 | .008 | .052 | .029 | (.011) | 2.647 | .008 | .007 | .050 |

| L - A - Anxiety | −.011 | (.029) | −.386 | .700 | −.068 | .046 | −.028 | (.028) | −.989 | .323 | −.082 | .027 |

| L - P - Anxiety | −.013 | (.029) | −.438 | .662 | −.070 | .045 | −.026 | (.028) | −.925 | .355 | −.082 | .029 |

| L - A - Avoidance | −.030 | (.030) | −1.003 | .316 | −.087 | .028 | −.027 | (.028) | −.933 | .351 | −.082 | .029 |

| L - P - Avoidance | .055 | (.030) | 1.825 | .068 | −.004 | .114 | .066 | (.029) | 2.293 | .022 | .010 | .123 |

| A - Anxiety | .072 | (.029) | 2.464 | .014 | .015 | .130 | .039 | (.028) | 1.360 | .174 | −.017 | .094 |

| P - Anxiety | −.031 | (.030) | −1.041 | .298 | −.089 | .027 | −.059 | (.029) | −2.050 | .040 | −.115 | −.003 |

| A - Avoidance | −.010 | (.030) | −.330 | .741 | −.068 | .049 | −.009 | (.029) | −.330 | .741 | −.066 | .047 |

| P - Avoidance | −.011 | (.030) | −.361 | .718 | −.071 | .049 | −.005 | (.029) | −.184 | .854 | −.063 | .052 |

| L — A - Cope | n/a | .044 | (.057) | .771 | .441 | −.068 | .156 | |||||

| A - Cope | n/a | .637 | (.054) | 11.849 | .000 | .531 | .742 | |||||

| Marital Alcohol Problems |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 2c: Direct |

Model 3c: Drinking-to-Cope |

|||||||||||

| 95% CI |

95% CI |

|||||||||||

| Predictors | b | (SE) | t | p | Lower | Upper | b | (SE) | t | p | Lower | Upper |

| Intercept | 1.085 | (.063) | 17.245 | .000 | .962 | 1.208 | 1.095 | (.063) | 17.527 | .000 | .973 | 1.218 |

| Time | .010 | (.012) | .830 | .407 | −.014 | .034 | .006 | (.012) | .462 | .644 | −.018 | .029 |

| L - Marital Problems | .389 | (.019) | 21.020 | .000 | .353 | .426 | .378 | (.019) | 20.435 | .000 | .342 | .415 |

| Gender | −.021 | (.068) | −.305 | .760 | −.153 | .112 | −.016 | (.067) | −.234 | .815 | −.147 | .115 |

| A - Average Consumption | .076 | (.015) | 5.125 | .000 | .047 | .105 | .068 | (.015) | 4.642 | .000 | .040 | .097 |

| P - Average Consumption | .030 | (.013) | 2.327 | .020 | .005 | .055 | .030 | (.013) | 2.381 | .017 | .005 | .055 |

| L - A — General Problems | −.092 | (.012) | −7.495 | .000 | −.116 | −.068 | −.094 | (.012) | −7.573 | .000 | −.118 | −.070 |

| A - General Problems | .404 | (.010) | 38.554 | .000 | .383 | .425 | .385 | (.011) | 35.561 | .000 | .364 | .406 |

| L - A - Anxiety | .010 | (.034) | .306 | .760 | −.056 | .077 | .001 | (.034) | .025 | .980 | −.065 | .067 |

| L - P - Anxiety | .003 | (.035) | .072 | .942 | −.066 | .071 | .005 | (.035) | .156 | .876 | −.062 | .073 |

| L - A - Avoidance | −.013 | (.035) | −.377 | .706 | −.081 | .055 | −.008 | (.034) | −.238 | .812 | −.076 | .059 |

| L - P - Avoidance | .049 | (.036) | 1.370 | .171 | −.021 | .118 | .051 | (.035) | 1.445 | .149 | −.018 | .120 |

| A - Anxiety | .065 | (.034) | 1.875 | .061 | −.003 | .132 | .050 | (.034) | 1.468 | .142 | −.017 | .117 |

| P - Anxiety | .097 | (.035) | 2.745 | .006 | .028 | .166 | .082 | (.035) | 2.352 | .019 | .014 | .151 |

| A - Avoidance | .021 | (.035) | .594 | .552 | −.048 | .089 | .023 | (.035) | .670 | .503 | −.045 | .091 |

| P - Avoidance | −.023 | (.036) | −.644 | .520 | −.094 | .048 | −.023 | (.036) | −.638 | .524 | −.093 | .047 |

| L — A - Cope | n/a | .020 | (.072) | .276 | .783 | −.121 | .161 | |||||

| A - Cope | n/a | .386 | (.068) | 5.677 | .000 | .253 | .519 | |||||

Note. Coefficients are unstandardized. L = Lagged Prior Wave Report. A = Actor Report. P = Partner Report. Gender was coded Male = 1; Female = 0. n/a indicates the term was not tested in the model. Model 1 shows the direct effects of the hypothesized predictors on the hypothesized mediator. Models 2a-2c show the direct effects of the hypothesized predictors on the hypothesized outcomes. Models 3a-3c show the full models in which the hypothesized mediator was added to Models 2a-2c, respectively.

Figure 1.

Summary figure for the three models predicting associations between actor attachment anxiety, relationship-specific drinking-to-cope, and the frequency of drinking with one’s partner (Figure 1a), the frequency of drinking apart from one’s partner (Figure 1b), and marital alcohol problems (Figure 1c), respectively. “+” or “−” indicates that the effect was positive or negative, respectively, and significant. “ns” and a dashed line indicate that the direct path was not significant. “L” indicates the effect was lagged.

Do insecure attachment styles predict relationship-specific drinking-to-cope?

We first examined effects of attachment styles on the hypothesized mediator: relationship-specific drinking-to-cope. As shown in Table 1, Model 1, and as expected, both concurrent actor and partner attachment anxiety significantly predicted greater reports of drinking to cope with a relationship problem at each wave, controlling for lagged effects of attachment styles and drinking-to-cope, time, and average rates of drinking. However, unexpectedly, no significant effects were found for attachment avoidance on relationship-specific drinking-to-cope, indicating that drinking-to-cope does not mediate effects of attachment avoidance on drinking-with-partner, drinking-apart-from-partner, or marital alcohol problems.

Do insecure attachment styles predict drinking with one’s partner?

We next examined direct effects of insecure attachment styles on the frequency of drinking with one’s partner. As shown in Table 1, Model 2a, and as expected, concurrent actor attachment anxiety was associated with significantly greater frequency of drinking-with-partner on average at each wave, controlling for lagged actor anxiety, time, and average rates of drinking. In contrast, concurrent partner attachment anxiety was marginally negatively associated with the frequency of drinking-with-partner at each wave. No effects were found for actor or partner attachment avoidance, or for lagged effects of attachment styles.

Are effects of attachment anxiety on drinking-with-partner mediated by relationship-specific drinking-to-cope motives?

To satisfy the final step of mediation, both concurrent and lagged actor reports of drinking-to-cope with relationship problems (i.e., the mediator) were added to the above model (see Table 1, Model 3a). As expected, concurrent drinking-to-cope was significantly associated with greater frequency of drinking-with-partner at each wave. However, the direct effects of both concurrent actor and partner attachment anxiety remained significant, suggesting that drinking-to-cope does not mediate these effects. A schematic summary of this final model is presented in Figure 1a.

Do insecure attachment styles predict drinking apart from one’s partner?

A parallel set of models tested the frequency of drinking apart from one’s partner as the outcome. As shown in Table 1, Model 2b, concurrent actor attachment anxiety similarly predicted significantly greater frequency of drinking apart at each wave, controlling for lagged reports of attachment anxiety and drinking apart, time, gender, and average rates of drinking. Additionally, there was a marginal effect (p = .068) of lagged partner avoidance, suggesting that partners’ avoidance at one wave predicts marginally greater actors’ reports of frequency of drinking apart at the following wave. Unexpectedly, no direct effects of partner attachment anxiety or actor attachment avoidance were found predicting drinking apart.

Are effects of actor attachment anxiety on drinking apart mediated by relationship-specific drinking-to-cope motives?

As shown in Table 1, Model 3b, concurrent drinking-to-cope also significantly predicted greater frequency of drinking apart at each wave. In the presence of drinking-to-cope, the effect of concurrent actor attachment anxiety reduced to nonsignificance, suggesting mediation of this effect. A Sobel test of the indirect effect was significant (Estimate = 2.990, SE = .007, p = .003) further supporting evidence of mediation. Additionally, two direct effects of partner attachment styles became significant in the presence of drinking-to-cope. There was a significant direct negative effect of concurrent partner attachment anxiety, suggesting that the more anxious one’s partner is, the less frequently the actor drinks apart from them at a given wave. There was also a significant lagged direct effect of partner attachment avoidance, indicating that the more avoidant one’s partner is at a given wave, the more likely one is to drink apart from them at the following wave, on average. A schematic summary of this final model is presented in Figure 1b. As shown in Figure 1b, this model reflects full mediation by relationship-specific drinking-to-cope compared to the model predicting drinking-with-partner (Figure 1a).

Do insecure attachment styles predict marital alcohol problems?

Finally, a parallel set of models tested the rates of marital alcohol problems as the outcome. As shown in Table 1, Model 2c, and in line with expectation, concurrent actor attachment anxiety predicted marginally (p = .061) greater marital alcohol problems at each wave controlling for lagged reports of actor attachment anxiety and marital alcohol problems, time, gender, average rates of drinking, and rates of non-marital alcohol problems. Similarly, concurrent partner attachment anxiety significantly predicted greater actor reports of marital alcohol problems at each wave. No direct effects were found for concurrent or lagged attachment avoidance on marital alcohol problems.

Are effects of attachment anxiety on marital alcohol problems mediated by relationship-specific drinking-to-cope motives?

As shown in Table 1, Model 3c, concurrent actor drinking-to-cope was associated with significantly greater rates of marital alcohol problems at each wave. In the presence of drinking-to-cope, the marginal effect of actor attachment anxiety was reduced to nonsignificance, suggesting mediation of this effect, which was further supported by a significant Sobel test of the indirect effect (Estimate = 2.715, SE = .005, p = .007). However, the direct effect of partner attachment anxiety again remained significant in the presence of drinking-to-cope, suggesting no mediation of this effect. A schematic summary of this final model is presented in Figure 1c. As shown in Figure 1c, this model was similar to the model predicting drinking apart (Figure 1b) in that it also represented full mediation by relationship-specific drinking-to-cope, both of which stand in contrast to the model predicting drinking-with-partner (Figure 1a).

Supplementary Analyses

Supplementary analyses were conducted to explore whether the mediated associations of actor attachment anxiety on drinking-apart-from-partner and on marital alcohol problems via relationship-specific drinking-to-cope were moderated by gender. Gender did not moderate the association between attachment anxiety and relationship-specific drinking-to-cope. Thus, there is not evidence in the current data that this mediational process as a whole differs between husbands and wives. Supplementary analyses were also conducted exploring whether anxious and avoidant attachment styles interacted within partners, and whether partner attachment styles moderated the effects of actor attachment styles. Attachment styles, either within or between partners, did not interact in the current analyses.

Discussion

The current study examined relationship-specific drinking-to-cope as a mediator of the effects of insecure attachment styles on relationship-drinking contexts and marital alcohol problems. A consistent pattern of effects was found for attachment anxiety and drinking-to-cope on marital drinking outcomes that were largely in line with expectation. However, the role of attachment avoidance in the examined processes was comparatively minimal. These results as a whole have important implications for research and theory on how attachment dynamics are associated with relationship-motivated drinking processes in the early years of marriage.

The current results suggest that one’s own level of attachment anxiety is an important variable in understanding relationship-motivated alcohol use processes in marriage. However, the role, and potential relationship implications, of attachment anxiety in relationship-motivated alcohol use processes also appears to depend in part on the relationship-drinking context. That is, drinking-to-cope processes operated differently for anxious individuals when predicting drinking-with-partner compared to other outcomes (see Figure 1). Although drinking-to-cope did not mediate the effects of attachment anxiety on drinking-with-partner, the direct effect in this model is nevertheless consistent with attachment theory. It is likely that anxious individuals perceive drinking with their partner as an adaptive process that is promotive of closeness and intimacy in the relationship. As such, they may hold relationship-drinking motives in other domains (e.g., intimacy enhancement) beyond drinking-to-cope that could mediate this association. Future research is needed to examine this and related questions.

In contrast, the effects of actor attachment anxiety on both the frequency of drinking apart from one’s partner (see Figure 1b) and marital alcohol problems (see Figure 1c) were mediated by relationship-specific drinking-to-cope. Both of these processes are consistent with prior research and theory as well as with each other. Specifically, the process predicting drinking apart is consistent with prior research showing increased demand-withdraw behaviors in anxiously attached individuals (Campbell, Simpson, Boldry, & Kashy, 2005; Shaver, Schachner, & Mikulincer, 2005). One possible interpretation is that anxious individuals withdraw from their partner by drinking apart as a means of coping with a relationship problem, especially if the excessive demand for their partner’s attention on the problem, which is characteristic of anxious attachment, was not fulfilled, or perceived to be more conflictual than it actually was (e.g., Campbell et al., 2005). The negative direct effects of partner attachment anxiety on both drinking-with-partner and drinking apart also support this notion that ambivalent demand-withdraw characteristics exist in relationship-drinking contexts with an anxiously attached partner. Taken together, from an attachment theoretical perspective, such behavior could reinforce anxious individuals’ insecure beliefs that their partner is not available or not willing to engage with them, which may also exacerbate negative emotions and feelings of insecurity among anxious individuals who drink apart from their partner to cope with a relationship problem. Future research is needed to examine perceptions of felt security and objective or invisible support among anxious individuals and their partners in the moments surrounding drinking apart to cope with a relationship problem.

The process predicting marital alcohol problems is also consistent with previous research and theory. This process, particularly for anxious compared to avoidant individuals, provides additional evidence that anxious individuals experience greater alcohol problems as a function of drinking-to-cope that are not accounted for by their levels of consumption (Molnar et al., 2010), and extends it by placing this process in the theoretically meaningful context of relationship drinking. Taken together, these results suggest that drinking-to-cope among anxious individuals could have strong, negative consequences for them and their relationships, considering that even small effects can be additive over time (Abelson, 1985; Cohen, 1988), thus becoming increasingly problematic as the relationship develops. It should be noted that our measure includes items assessing physical aggression. Therefore, our results may have implications for future research and theory on the associations between alcohol use and interpersonal violence in relationships, particularly among anxiously attached individuals and their partners. However, because the majority of our marital alcohol problems items assessed non-violent problems, and given the relatively distal assessment of our study, we are cautious to make any conclusions about the nature of violent vs. non-violent problems in the examined processes. Future research is necessary to tease apart the roles and prevalence of violent vs. non-violent marital alcohol problems in the drinking processes of anxious individuals. This is particularly true for future research using daily diary or laboratory methodologies where the process effects of alcohol and related problems can be more proximally examined (e.g., Crane, Testa, Derrick, & Leonard, 2014) relative to the current longitudinal study. Nevertheless, the current findings suggest targets for couples prevention and intervention efforts involving anxious individuals and their partners.

The role of attachment avoidance was minimal in the relationship-drinking processes examined compared to attachment anxiety. Avoidance was not associated with relationship-specific drinking-to-cope, and was largely not associated with the current set of relationship-drinking outcomes. Only one direct effect was found, which was in line with expectation, for lagged partner avoidance on subsequent actor reports of drinking apart. Nevertheless, these results as a whole for avoidance are not altogether unexpected given that the literature shows mixed effects for avoidance and alcohol use associations compared to relatively more consistent effects for attachment anxiety. It is also possible that avoidant individuals are motivated by other relationship-specific factors beyond coping with a relationship problem. Future research is needed to examine these possibilities.

Our findings provide support for a Relationship-Motivation Model of Alcohol Use (Leonard & Mudar, 2004). The current study is the first to demonstrate evidence that certain couple members are motivated to drink for relationship-specific reasons, and that these processes differ depending on their attachment styles and the context in which drinking occurs in the relationship. These results support and extend prior theoretical work on drinking motivation (Cooper et al., in press; Cox & Klinger, 1988) and adult romantic attachment (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2003), and bridges those foundations to address relationship-motivated drinking. However, it is likely that couple members are motivated to drink in their relationship for other reasons beyond drinking-to-cope, including intimacy and power reasons (Levitt & Leonard, 2013; Levitt et al., 2014), to which the current study’s assessment was limited. Future research is needed to examine more domains of relationship-specific drinking motives, and how those motives relate to relationship-specific alcohol expectancies, behaviors, and outcomes.

Despite its many strengths, however, the current study was not without limitations. First, it is unknown whether the motivational processes found in the current study generalize to couples beyond the early years of marriage. Future research is needed to examine these associations in couples over various stages of relationship development. Additionally, the processes examined in the current study are likely subject to situational and contextual differences at a more micro level (i.e., daily or momentary). Therefore, it is unknown how the current approximation of these processes in our longitudinal data manifests in couples’ daily lives. Future research using daily diary or ecological momentary assessment methodologies could better assess the temporal processes and other variables associated with relationship-specific drinking motives. Future research also needs to directly compare relationship-specific drinking motives to general drinking motives (e.g., Cooper, 1994) to determine the unique effects of relationship-specific motives. The current study was limited in that it did not assess general drinking motives, or relationship-specific drinking motives beyond drinking-to-cope. Finally, it may be viewed as a limitation that our endorsement rates of drinking-to-cope were relatively low. However, these items were assessed distally in the aggregate (i.e., about a particular problem over the past year), and may be underreported due to relative proximity to the event in question. Future research using more proximal designs are needed to better understand rates of endorsement for relationship-specific drinking-to-cope, particularly following certain momentary relationship problems.

In conclusion, the current study was the first to directly test relationship-specific drinking motives as a mediator of insecure attachment styles on relationship-drinking outcomes in the early years of marriage. The role of attachment anxiety in relationship-specific drinking-to-cope processes in marriage appears to be much more prominent and consistent relative to attachment avoidance, and highlights variables of concern for relationship researchers and clinicians. The current study supports and extends previous research on relationship alcohol use, and provides theoretically consistent support for a Relationship-Motivation Model of Alcohol Use.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grant R37-AA09922 awarded to Kenneth E. Leonard. Preparation of this manuscript was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grant K01-AA021769 awarded to Ash Levitt.

Footnotes

Author Note: Ash Levitt, Research Institute on Addictions, University at Buffalo, SUNY; Kenneth E. Leonard, Research Institute on Addictions, University at Buffalo, SUNY.

References

- Abelson RP. A variance explanation paradox: When a little is a lot. Psychological Bulletin. 1985;97:129–133. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.97.1.129. [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew K, Horowitz LM. Attachment styles among young adults: A test of the four-category model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;61:226–244. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.2.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, Laurenceau J-P. Intensive longitudinal methods: An introduction to diary and experience sampling research. Guilford; New York: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment. Basic Books; New York: 1969/1982. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan KA, Shaver PR. Dimensions of adult attachment, affect regulation, and romantic relationship functioning. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1995;21:267–283. doi: 10.1177/0146167295213008. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell L, Simpson JA, Boldry J, Kashy DA. Perceptions of conflict and support in romantic relationships: The role of attachment anxiety. Journal of Peronality and Social Psychology. 2005;88:510–531. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.3.510. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.3.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd Ed. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; New York: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Frone MR, Russell M, Mudar P. Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:990–105. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Kuntsche E, Levitt A, Barber LL, Wolf S. Motivational models of substance use: A review of theory and research on motives for using alcohol, marijuana, and tobacco. In: Sher KJ, editor. The Oxford handbook of substance use disorders. Oxford University Press; New York: in press. [Google Scholar]

- Cox M, Klinger E. A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1988;97:168–180. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.97.2.168. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.97.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane CA, Testa M, Derrick JL, Leonard KE. Daily associations among self-control, heavy episodic drinking, and relationship functioning: An examination of actor and partner effects. Aggressive Behavior. 2014;40:440–450. doi: 10.1002/ab.21533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeHart T, Tennen H, Armeli S, Todd M, Affleck G. Drinking to regulate negative romantic relationship interactions: The moderating role of self-esteem. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2008;44:527–538. [Google Scholar]

- Derrick JL, Leonard KE, Quigley BM, Houston RJ, Testa M, Kubiak A. Relationship-specific alcohol expectancies in couples with concordant and discrepant drinking patterns. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2010;71:761–768. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin D, Bartholomew K. Models of the self and other: Fundamental dimensions underlying measures of adult attachment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67:430–445. [Google Scholar]

- Homish GG, Leonard KE. Marital quality and congruent drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:488–496. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homish GG, Leonard KE, Kearns-Bodkin JN. Alcohol use, alcohol problems, and depressive symptomatology among newly married couples. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;83:185–192. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp . IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22. IBM Corp; Armonk, NY: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kashy DA, Donnellan MB. Conceptual and methodological issues in the analysis of data from dyads and groups. In: Deaux K, Snyder M, editors. The Oxford Handbook of Personality and Social Psychology. Oxford University Press; New York: 2012. pp. 209–238. [Google Scholar]

- Kassel JD, Wardle MW, Roberts JE. Adult attachment security and college student substance use. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:1164–1176. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.08.005. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Cook WL. Dyadic data analysis. Guilford Press; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Krull JL, MacKinnon DP. Multilevel modeling of individual and group level mediated effects. Multilevel Behavioral Research. 2001;36:249–277. doi: 10.1207/S15327906MBR3602_06. doi: 10.1207/S15327906MBR3602_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurenceau JP, Bolger N. Using diary methods to study marital and family processes. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19:86–97. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.1.86. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Mudar P. Husbands’ influence on wives’ drinking: Testing a relationship motivation model in the early years of marriage. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18:340–349. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.4.340. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.4.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt A, Cooper ML. Daily alcohol use and romantic relationship functioning: Evidence of bidirectional, gender-, and context-specific effects. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2010;36:1706–1722. doi: 10.1177/0146167210388420. doi: 10.1177/0146167210388420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt A, Derrick JL, Testa M. Relationship-specific alcohol expectancies moderate the effects of relationship-drinking contexts on daily relationship functioning. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2014;75:269–278. PMCID: PMC3965681. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt A, Leonard KE. Relationship-specific alcohol expectancies and relationship-drinking contexts: Reciprocal influence and gender-specific effects over the first 9 years of marriage. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2013;27:986–996. doi: 10.1037/a0030821. doi: 10.1037/a0030821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally AM, Palfai TP, Levine RV, Moore BM. Attachment dimensions and drinking-related problems among young adults: The mediational role of coping motives. Addictive Behaviors. 2003;28:1115–1127. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(02)00224-1. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4603(02)00224-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mickelson KD, Kessler RC, Shaver PR. Adult attachment in a nationally representative sample. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;73:1092–1106. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.73.5.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M, Shaver PR, editors. Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change. Guilford; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M, Shaver PR. The attachment behavioral system in adulthood: Activation, psychodynamics, and interpersonal processes. Advanced in Experimental Social Psychology. 2003;35:53–152. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2601(03)01002-5. [Google Scholar]

- Mohr CD, Armeli S, Tennen H, Carney MA, Affleck G, Hromi A. Daily interpersonal experiences, context, and alcohol consumption: Crying in your beer and toasting good times. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;80:489–500. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.80.3.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molnar DS, Sadava SW, DeCourville NH, Perrier CPK. Attachment, motivations, and alcohol: Testing a dual-path model of high-risk drinking and adverse consequences in transitional clinical and student samples. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science. 2010;42:1–13. doi: 10.1037/a0016759. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez LM, Knee CR, Neighbors C. Relationships can drive some to drink: Relationship-contingent self-esteem and drinking problems. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2014;31:270–290. [Google Scholar]

- Senchak M, Leonard KE. Attachment styles and marital adjustment among newlywed couples. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1992;9:51–64. doi: 10.1177/0265407592091003. [Google Scholar]

- Shaver PR, Schachner DA, Mikulincer M. Attachment style, excessive reassurance seeking, relationship processes, and depression. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2005;31:343–359. doi: 10.1177/0146167204271709. doi: 10.1177/0146167204271709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Grekin ER. Alcohol and affect regulation. In: Gross JJ, editor. Handbook of emotion regulation. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2007. pp. 560–580. [Google Scholar]