Abstract

Objective

To examine the association between expanded access to collaborative midwifery and laborist services and cesarean delivery rates.

Methods

This was a prospective cohort study at a community hospital between 2005 and 2014. In 2011, privately insured women changed from a private practice model to one that included 24-hour midwifery and laborist coverage. Primary cesarean delivery rates among nulliparous, term, singleton, vertex women and vaginal birth after cesarean delivery (VBAC) rates among women with prior cesarean were compared before and after the change. Multivariable logistic regression models estimated the effects of the change on the odds of primary cesarean and VBAC; an interrupted time series analysis estimated the annual rates before and after the expansion.

Results

There were 3,560 nulliparous term singleton vertex deliveries and 1,324 deliveries with prior cesarean during the study period; 45% were among privately insured women whose care model changed The primary cesarean rate among these privately insured women decreased after the change, from 31.7% to 25.0% (p=0.005, adjusted odds ratio (aOR) 0.56 (95% CI 0.39 – 0.81). The interrupted time series analysis estimated a 7% drop in the primary cesarean rate in the year after the expansion, and a decrease of 1.7% per year thereafter. The VBAC rate increased from 13.3% before to 22.4% afterward; aOR 2.03 (95%CI 1.08 – 3.80).

Conclusion

The change from a private practice to a collaborative midwifery–laborist model was associated with a decrease in primary cesarean rates and an increase in VBAC rates.

Introduction

Obstetric practice in the US currently faces a number of challenges. Cesarean delivery rates have been increasing and vaginal birth after cesarean delivery (VBAC) rates are decreasing, without concomitant improvement in maternal or neonatal outcomes (1–3). Because of the inherent difficulties associated with balancing outpatient, surgical, and personal responsibilities with the unpredictable nature of labor and delivery, the laborist model, has seen rapid growth in recent years and is estimated to be used in up to approximately 40% of US hospitals(6, 7). The term “laborist” has many definitions, but generally designates an obstetrician who provides in-house labor and delivery coverage without competing clinical duties (7). Recent studies suggest that the presence of laborists is associated with decreased rates of cesarean delivery; hypothesized reasons for these decreases include increased tolerance with equivocal fetal heart rate tracings and decreased competition between a physician’s desire to patiently await a vaginal delivery and outside clinical and personal responsibilities. (8–10). Access to midwifery care has also been shown to be associated with lower cesarean delivery rates, although data are sparse. (13–15)

We previously reported that primary cesarean delivery rates at a single institution in Northern California were lower among publically insured women who delivered under a laborist model that includes 24-hour in-hospital midwifery coverage than among privately insured patients who delivered under a traditional private practice model (16). In this report we present results of an analysis of the expansion of this laborist-midwifery model to privately insured patients.

Materials and Methods

We conducted a cohort study of all liveborn deliveries at Marin General Hospital between April 2005 and March 2014. All publicly insured women at this institution, which is the only obstetric hospital in the county, are covered under the Medi-Cal program (California’s state Medicaid program) and most receive prenatal care from midwives working at a public clinic, while the overwhelming majority of privately insured women receive their prenatal care from a private practice physician in a variety of group or solo practice settings. Prior to April 2011, these two groups also experienced two different models of labor and delivery care. Specifically, publicly insured women were cared for primarily by midwives, with 24-hour in-house laborist back-up. Privately insured women were managed under the more conventional private practice model, in which their labor and delivery care was provided by the private physician or a covering partner who took call while at home or in the office and, in general, managed labor remotely

In April 2011, a large change was instituted in the way that labor and delivery coverage was organized. This change occurred because of concerns about the economic feasibility of maintaining 24-hour in-house obstetrician and midwifery coverage for only half of the patients (i.e., the publicly insured), the desire to expand access to midwifery services to all patients, and the difficulties faced by the private practitioners integrating labor and delivery coverage with other responsibilities (17). Coverage was changed so that the midwifery and laborist services would be available to the privately as well as the publicly insured women. A group of 10 private practice physicians began to take labor and delivery call as laborists, joining the obstetricians who had been caring for the publicly insured (those providing prenatal care to the publicly insured women as well as per-diem laborists). After the change, one midwife and one laborist were in-house, 24 hours a day, working collaboratively to provide primary labor management for all private and public patients of the newly formed group. For the private patients, this new model introduced two significant changes: the option of midwifery care, and having their managing clinician in house at all times. While privately insured women who opted for physician care could request to be delivered by a member of the private practice group if the in-house obstetrician was not a member, their labor was always managed by the in-house laborist. A small group of private physicians did not participate in this change and maintained the private practice model; the patients cared for by these providers were not included in this analysis. Our primary hypotheses were that this expansion would be associated with 1) decreased primary cesarean delivery rates and 2) increased vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC) rates among the privately insured patients.

Maternal and neonatal data were collected prospectively by delivering clinicians and nurses, as well as three dedicated chart abstractors These data were used for state reporting and birth certificate reporting as well as research, ensuring complete records.

The primary predictor for this analysis was the change in practice occurring in 2011 that expanded access to 24-hour in-house midwifery and laborist services to the privately insured women whose providers participated in the laborist system. Our two primary outcomes were primary cesarean rates among nulliparous women carrying term, singleton pregnancies in the vertex position and VBAC rates among women with a history of prior cesarean. To examine the possibility of secular trends in primary cesarean and VBAC rates over time, we also examined these outcomes in the publicly insured women whose care model did not change, and who thus served as a non-equivalent control group (18, 19). As a secondary outcome, we examined a composite of short-term adverse neonatal outcomes including 5 min Apgar <7, umbilical artery pH<7.0 and umbilical artery base excess < −12.

Demographic and clinical characteristics were compared before and after the practice change using chi-square or t-tests; this was done separately for the privately insured and publicly insured patient groups.

We analyzed changes in the outcomes three ways: 1) a simple pre-post analysis comparing rates before and after the practice change, stratified by insurance status and using chi-square tests; 2) a multivariable logistic regression model comparing rates before and after the change, controlling for maternal clinical and demographic covariates and including an interaction term with insurance status; and 3) an interrupted time series analysis that allowed us to examine the possibility of concurrent secular trends in cesarean delivery rates which could influence the results. Interrupted time series models estimate the slope of each outcome over time before and after the intervention, compare the slope of outcome rates before and after the practice change, and examine the model-predicted change in outcome level at the time of the expansion. For each outcome, interrupted time series models were fit as linear models of annual rates expressed as percentages with an autoregressive residual correlation structure. Statistical significance was considered with p-values < 0.05; interactions with p-values <0.1 were examined more closely. All analyses were performed with SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) We excluded privately insured women who delivered with the few remaining private physicians who did not join the laborist call pool.

Deliveries included in these analyses occurred between April 2005 and March 2014 (six years before and three years after the expansion) and were among women who were either covered by public insurance and received prenatal care at the publicly-funded clinic or who had private insurance and were cared for by the private practice physicians who joined the laborist system. Approval for the study was granted by the UCSF Committee on Human Research and the Marin General Hospital Institutional Review Board.

Results

Between April 2005 and March 2014, there were a total of 13,194 births for a mean annual delivery volume of 1466. Of these, 4,884 deliveries met criteria for inclusion in the analysis, 3,413 before the practice change and 1,471 afterward. 3,560 women were nulliparous, and delivered term, singletons in the vertex position, and 1,324 had a prior cesarean. About half (49%) of these women (N=2406) were privately insured and, as a group, were exposed to the practice change. There were 10 private obstetricians who changed their practice model and began providing 24-hour in-house laborist coverage, without any change in reimbursement scheme; as they were salaried and were paid the same for a shift whether or not they performed any deliveries. Before the change, laborist coverage was provided by three obstetricians who provided prenatal care to the publicly insured women covering 25% of the shifts, a laborist program director who covered 15% of the shifts, and 10–12 per-diem laborists who covered the remaining 60% of the shifts. After the change, the 10 private practice physicians who joined the laborist call pool covered 30% of the shifts, and the number of shifts covered by 6–8 per-diem laborists went down to 30%. Twenty-four hour in-house midwifery coverage was provided by an annual average of 14 midwives before and 12 midwives after the expansion, with the decrease in staff due to an increase in full-time rather than part-time workers. The midwifery service attended to 21% of the privately insured vaginal births in the first year of the new program, and increased to 42% by the third year. In contrast, the midwifery service attended 80–90% of the vaginal births among the publicly insured before and after the change.

There were several differences in the demographic and clinical characteristics of the privately insured women who delivered after the practice change compared to those who delivered before, including a higher percentage with diabetes and hypertension, and a lower percentage who underwent induction of labor (Table 1). Among publicly insured women, we observed increases in the percentage who had college degrees, the percentage who used epidurals, and maternal age.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics before and after Expansion of Laborist and Midwifery Services to Privately Insured Women

| PRIVATELY INSURED WOMEN (change to a 24-hour laborist/midwifery model in 2011) |

PUBLICLY INSURED WOMEN (24 hour laborist/midwifery model during all years of observation) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before Expansion N=1653 |

After Expansion N=753 |

p value | Before Expansion N=1760 |

After Expansion N=718 |

p value | |

| Mean annual delivery volume (range) | 276 (233–315) | 251 (249–253) | 293 (273–323) | 239 (229–259) | ||

| Mean maternal age in years (±SD) | 33.5 (±4.8) | 33.6 (±5.2) | .73 | 25.0 (±5.8) | 26.6 (±6.3) | <.001 |

| Mean gestational age in weeks (±SD) | 39.7 (±1.1) | 39.6 (±1.2) | .55 | 39.7 (±1.3) | 39.6 (±1.2) | .01 |

| Race/Ethnicity | .15 | .003 | ||||

| White | 1355 (82.0%) | 593 (78.8%) | 160 (9.1%) | 78 (10.9%) | ||

| Latino/Hispanic | 117 (7.1%) | 61 (8.1%) | 1465 (83.2%) | 556 (77.4%) | ||

| Asian | 117 (7.1%) | 55 (7.3%) | 35 (2.0%) | 29 (4.0%) | ||

| African American/Black | 18 (1.1%) | 9 (1.2%) | 36 (2.0%) | 16 (2.2%) | ||

| Other/unknown | 46 (2.8%) | 35 (4.6%) | 64 (3.6%) | 39 (5.4%) | ||

| College degree | 1475 (90.6%) | 619 (92.0%) | .29 | 242 (13.9%) | 144 (23.4%) | <.001 |

| Maternal diabetes | 60 (3.6%) | 52 (6.9%) | <.001 | 138 (7.8%) | 74 (10.3%) | .05 |

| Maternal hypertension | 70 (4.2%) | 55 (7.3%) | .002 | 77 (4.4%) | 37 (5.2%) | .40 |

| Induction of labor | 299 (18.1%) | 105 (13.9%) | .01 | 238 (13.5%) | 89 (12.4%) | .45 |

| Epidural usage | 992 (60.0%) | 467 (62.0%) | .35 | 706 (40.1%) | 358 (49.9%) | <.001 |

| Neonatal birth weight | 3464.7 (±438.3) | 3409.8 (±469.9) | .007 | 3369.8 (±464.5) | 3362.6 (±445.1) | .73 |

The privately insured nulliparous women whose providers participated in expansion of midwifery and laborist services had a decrease in the rate of primary cesarean delivery from 31.7% to 25.0%, (p=0.005,Table 2) During the same time period, the primary cesarean rate did not significantly change among the publicly insured women (15.5% vs. 16.1%, p=0.78).

Table 2.

Nulliparous term singleton vertex cesarean delivery rates before and after expansion of midwifery and laborist services

| PRIVATELY INSURED WOMEN (change to a 24-hour laborist/midwifery model in 2011) |

PUBLICLY INSURED WOMEN (24 hour laborist/midwifery model during all years of observation) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before Expansion N=1201 |

After Expansion N=521 |

p value | Before Expansion N=1340 |

After Expansion N=498 |

p value | |

| Primary Cesarean Delivery Rate |

31.7% (n=381) |

25.0% (n=130) |

0.005 | 15.5% (n=208) |

16.1% (n=80) |

0.78 |

| Adjusted OR* (95% CI) |

0.56 (0.39 – 0.81) | 0.002 | 0.80 (0.54 – 1.17) | 0.25 | ||

Adjusted for: maternal age, race/ethnicity, education, gestational age, epidural, induction of labor, maternal medical complication, birth weight, delivery year, and with an interaction term for insurance type.

A multivariable logistic regression model (controlling for maternal age, race/ethnicity, education, gestational age, epidural, induction of labor, maternal medical complication, birth weight, delivery year, and with an interaction term for insurance type) revealed a clinically and statistically significant reduction in primary cesarean rates after the practice change among the privately insured women (aOR 0.56, 95% CI 0.39 – 0.81, p=0.002), but not among the publicly insured women (aOR 0.80, 95% CI 0.54 – 1.17, p=0.25). The p value for the interaction term was 0.092.

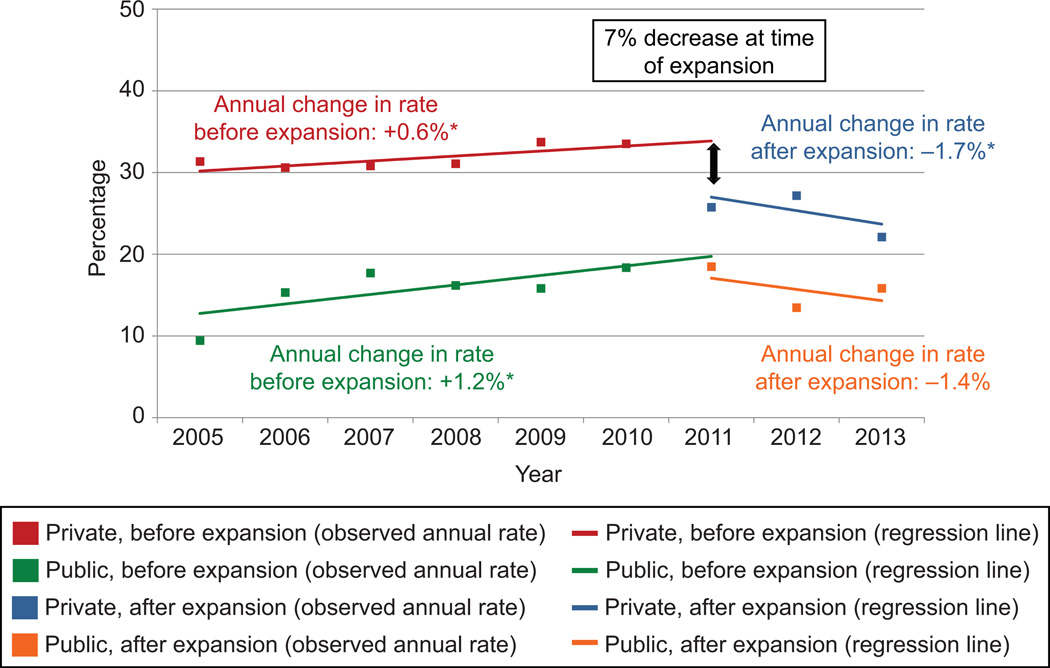

Similar to national trends, the primary cesarean rate among the privately insured increased by 0.6% per year before the practice change (Figure 1). During the first year of the expansion the primary cesarean rate dropped by an estimated 6.9% (p=0.009) and thereafter this rate continued to decrease by nearly 2% per year. The slopes of the estimated annual change in primary cesarean rates both before and after the practice change significantly differed from zero, and the two slopes significantly differed from one another (Appendix 1, available online at http://links.lww.com/xxx).

Figure 1.

Nulliparous term singleton vertex primary cesarean delivery rate among privately and publicly insured women before and after expansion of midwifery and laborist services. This graph shows the rates of nulliparous term singleton vertex cesarean delivery plotted over time and the model-predicted rates before and after the practice change as predicted by the interrupted-time series analysis. *The slope is statistically different from zero.

The primary cesarean rates among the publicly insured women followed a similar trend, but while the regression slope prior to the expansion was significantly different from zero, the slope after the expansion was not, and the rates of change before and after were not significantly different from each other (Appendix 1, http://links.lww.com/xxx). There was no significant drop at the time of expansion among the publicly insured. We performed a sensitivity analysis including induction of labor as a covariate because the rates of induction changed during the study period and found results similar to the primary analysis among the privately insured women: the decrease at the time of the practice change was estimated at 3% (p=0.029) and the annual primary cesarean rate was 3% lower after the expansion than before (p=0.004).

We also observed a substantial increase in the VBAC rate among the privately insured women who had a prior cesarean, from 13.3% to 22.4% (p=0.002,Table 3) Whereas the VBAC rate decreased among the publicly insured women, this change was not statistically significant (33.8% vs. 26.8% p=0.07). When we adjusted for confounders, the increase in VBAC rate remained statistically significant in the privately insured group (aOR 2.03, 95% CI 1.08–3.80, p=0.03). The p-values for the interaction between the pre-post practice change indicator and insurance status were 0.0005 and 0.0016, for the unadjusted and adjusted models, respectively.

Table 3.

Vaginal birth after cesarean delivery rates before and after expansion of midwifery and laborist services

| PRIVATELY INSURED WOMEN (change to a 24-hour laborist/midwifery model in 2011) |

PUBLICLY INSURED WOMEN (24 hour laborist/midwifery model during all years of observation) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before Expansion N=452 |

After Expansion N=232 |

p value | Before Expansion N=420 |

After Expansion N=220 |

p value | |

| VBAC Rate | 13.3% (n=60) |

22.4% (n=52) |

0.002 | 33.8% (n=142) |

26.8% (n=59) |

0.07 |

| Adjusted OR* (95% CI) |

2.03 (1.08 – 3.80) | 0.03 | 0.74 (0.41–1.36) | 0.34 | ||

Adjusted for: maternal age, race/ethnicity, education, gestational age, epidural, induction of labor, maternal medical complication, birth weight, delivery year, and with an interaction term for insurance type.

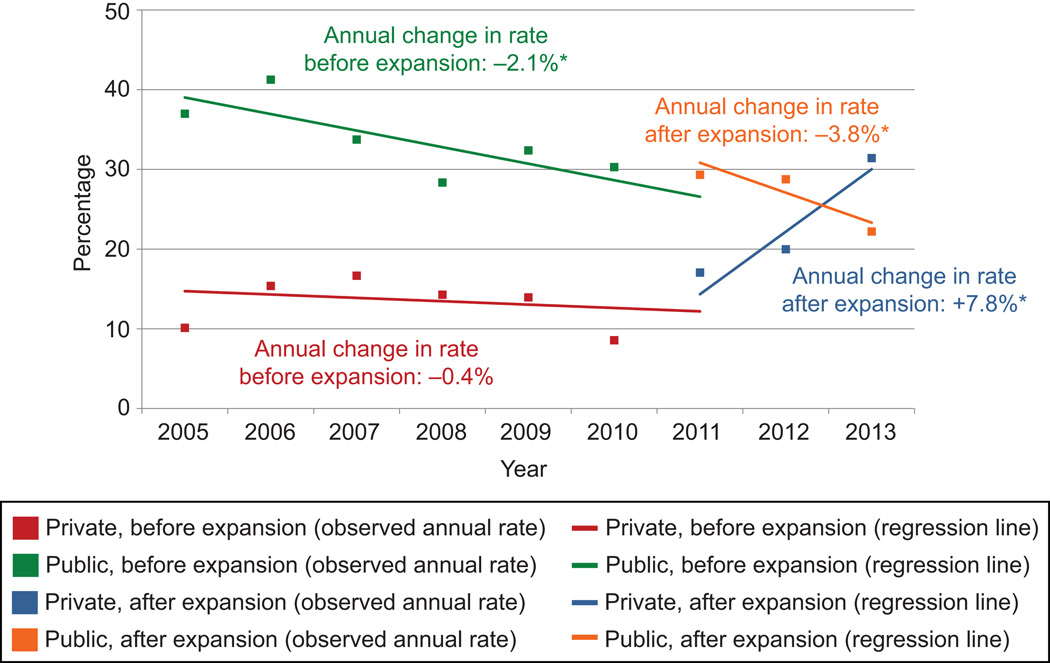

Results of the interrupted time series analysis of trends in VBAC rate over time before and after the practice change are shown in Figure 2. Prior to the change, there was no significant effect of calendar year on the VBAC rate among the privately insured women (0.4% annual decrease, p=0.38). Following the practice change, privately insured women had an 8% annual increase in VBAC rate (p=0.004); the difference between pre- and post-practice change slopes was statistically significant (p=0.004). (Appendix 2, available online at http://links.lww.com/xxx) Among the publically insured women the difference in model-predicted VBAC rates in the year following the practice change was not significant, and no difference emerged in the decreasing rate of VBAC before and after the practice change (−2% vs. −4%, p=0.3 for difference pre- vs. post-practice change slopes). In other words, while the simple pre-post analysis of publically insured women suggested a lower rate of VBAC after the expansion, the interrupted time series analysis revealed that this change in rate represented a persistent trend rather than a change that might be attributable to the intervention itself.

Figure 2.

Vaginal birth after cesarean delivery (VBAC) rate among privately and publicly insured women before and after expansion of midwifery and laborist services. This graph shows the rates of VBAC plotted over time and the model-predicted rates before and after the practice change as predicted by the interrupted-time series analysis. *The slope is statistically different from zero.

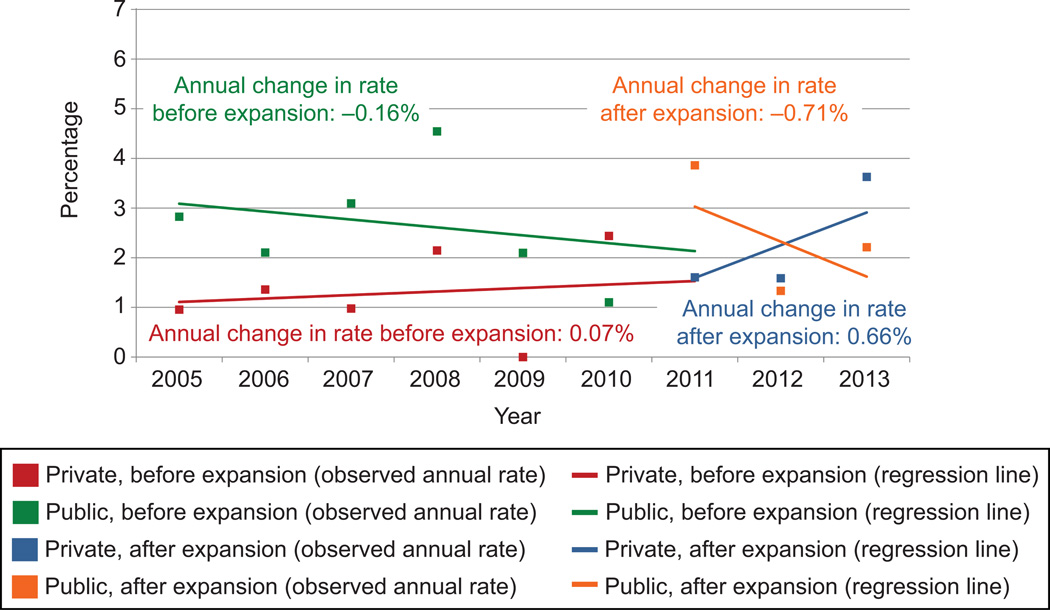

There were no statistically significant differences among rates of the composite of adverse short-term neonatal outcomes (incidence of Apgar < 7, umbilical artery pH <7.0 or umbilical artery base excess >12) before or after the expansion among the privately insured women exposed to the practice change (21/1649, 1.3% vs. 14/748, 2.3%, p=0.07) (Table 4). As seen in Figure 3, adverse neonatal outcomes among the privately insured patients were increasing before the practice change and maintained a similar rate of increase afterward, without any statistically significant change after the expansion (0.07% vs. 0.66%, p=0.11 for differences in rates of change) (Appendix 3, available online at http://links.lww.com/xxx). The interaction between the pre-post practice change indicator and insurance status was not statistically significant in neither the adjusted or unadjusted model (p= 0.14 for both models).

Table 4.

Short-term adverse neonatal outcomes before and after expansion of midwifery and laborist services

| PRIVATELY INSURED WOMEN (change to a 24-hour laborist/midwifery model in 2011) |

PUBLICLY INSURED WOMEN (24 hour laborist/midwifery model during all years of observation) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before Expansion N=1649 |

After Expansion N=749 |

p value | Before Expansion N=420 |

After Expansion N=220 |

p value | |

| Composite adverse neonatal outcome* |

1.3% (n=21) |

2.3% (n=17) |

0.07 | 2.7% (n=47) |

2.5% (n=18) |

0.84 |

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) |

1.80 (0.94 – 3.43) | 0.07 | 0.95 (0.55 – 1.64) | 0.84 | ||

| Adjusted OR** (95% CI) |

1.47 (0.57 – 3.75) | 0.42 | 0.72 (0.30 – 1.71) | 0.45 | ||

Composite neonatal outcome includes 5 minute APGAR <7, umbilical artery pH<7.0, umbilical artery base excess >12.

Adjusted for: maternal age, race/ethnicity, parity, education, gestational age, epidural, induction of labor, maternal medical complication, birth weight, delivery year, and with an interaction term for group.

Figure 3.

Composite adverse neonatal complication rate among privately and publicly insured women before and after expansion of midwifery and laborist services. This graph shows the rates of composite short term adverse neonatal outcomes (5 minute APGAR <7, umbilical artery pH<7.0, umbilical artery base excess <–12) plotted over time and the model-predicted rates before and after the practice change as predicted by the interrupted-time series analysis. None of the slopes were statistically different from zero.

Discussion

In this study, we found that the expansion of midwifery and laborist services in a collaborative practice model at a single community hospital was associated with a decreased primary cesarean delivery rate and an increased rate of VBAC

Our study has two methodological strengths that bolster the validity of our findings. First, unlike many pre–post analyses of practice changes at the hospital level, we had a control group at the same hospital that would have experienced any other hospital-wide interventions that may have had an impact on cesarean delivery rates. Also, we performed an interrupted time series analysis in addition to the simple pre-post analysis. While a pre–post analysis is easier to understand, it can lead to misleading results. For example, if the primary cesarean rates were steadily decreasing in this hospital due to other factors, a simple pre–post analysis would estimate a lower rate after the expansion, but this would not be attributable to the practice change. In our study, we graphically demonstrated the converse: primary cesarean rates were increasing slightly before the expansion and decreased afterward. This pattern of change in the primary cesarean rates was similar in both groups, although the magnitude of the change was only clinically and statistically significant among the privately insured women.

Another important finding is the substantial increase in VBAC rates among the privately insured women. Only the group of women whose providers participated in this expansion saw a reversal of the trend of decreasing VBAC rates with an increase in VBAC rate, both at the time of the expansion and for each year thereafter. The presence of 24-hour in-house providers who were directly involved in the care of privately insured women may explain this increase; private prenatal care providers may have been more likely to recommend trial of labor after cesarean because they no longer had to contend with the difficulties of managing these high-risk patients remotely or being called in to attend to an emergency while on call from the office or home.

A similar decrease in primary cesarean rates associated with implementation of a laborist program in Nevada has been reported; however, the Nevada study only demonstrated decreased rates with dedicated laborists without any outpatient duties. (9) The program described in our analysis differed from the Nevada program in two ways: midwifery services were also included, and the in-house laborists cared for all laboring patients regardless of insurance status, which may explain why we observed a decrease in cesarean rates using “community laborists” while they did not.

While our results point to a clear decrease in primary cesarean delivery and increase in VBAC rates associated with the midwifery–laborist expansion, we are unable to identify whether this change was due to the increased availability of in-house obstetricians and midwives, the collaborative practice model that developed as a result of the expansion, or another unidentified factor. We cannot be certain whether other factors could have led to the decrease in rates, although there were no other official hospital policies that took effect during this time. It is possible that the decreased induction rate was due to fewer elective inductions for provider convenience, but the sensitivity analysis that included induction status suggests that any change in induction rates was not the primary driver of the decrease in cesarean delivery seen in our study.

Several limitations deserve comment. This is an analysis of a practice change at a single institution; whether similar changes would happen with the implementation of this model at other hospitals is not known. Due to the rarity of adverse events and a high degree of missing cord gas collection (40%), we were underpowered to detect small changes in the rates of adverse neonatal outcomes. Based on our sample size and the low frequency of adverse events, our study was powered to detect a post-intervention rate in the privately insured of 3.0%, and the 95% CI calculated from the interrupted time series suggests that the true difference in slopes before and after the intervention may range from −0.02% to 1.20%. We therefore cannot rule out a true small increase in adverse neonatal outcomes, and future studies should focus efforts on complete data collection of adverse neonatal outcomes including NICU admission, birth trauma, and routine cord gas assessment.

Our study adds to the growing literature on the association between laborists and midwives and decreasing primary cesarean rates and increasing VBAC rates. As other maternity hospitals consider changing their staffing paradigms, similar analyses should be conducted to evaluate the association of expanding laborist and midwifery services with maternal and neonatal outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Dr. Rosenstein is supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Grant # HD01262, as a Women’s Reproductive Health Research Scholar. The work was also funded in part by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Grant # UCSF-CTSI UL1 TR000004 and the non-profit Prima Medical Foundation.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

Presented at the 35th Annual Meeting of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine in San Diego, Feb 5–7, 2015.

References

- 1.Podulka J, Stranges E, Steiner C. Hospitalizations Related to Childbirth, 2008. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2011. Apr, [cited February 18, 2013]. HCUP Statistical Brief #110. HCUP Statistical Brief #110. ed. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.March of Dimes Peristats. March of Dimes. [cited May 31, 2013];2013 [Internet] Available from: www.marchofdimes.com/peristats. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Callaghan WM, Creanga AA, Kuklina EV. Severe maternal morbidity among delivery and postpartum hospitalizations in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Nov;120(5):1029–1036. doi: 10.1097/aog.0b013e31826d60c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clark SL, Belfort MA, Dildy GA, Meyers JA. Reducing obstetric litigation through alterations in practice patterns. Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Dec;112(6):1279–1283. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31818da2c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olson R, Garite TJ, Fishman A, Andress IF. Obstetrician/gynecologist hospitalists: can we improve safety and outcomes for patients and hospitals and improve lifestyle for physicians? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Aug;207(2):81–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Srinivas SK, Shocksnider J, Caldwell D, Lorch S. Laborist model of care: who is using it? J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012 Mar;25(3):257–260. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2011.572206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weinstein L. The laborist: a new focus of practice for the obstetrician. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003 Feb;188(2):310–312. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Committee opinion no. 459: the obstetric-gynecologic hospitalist. Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Jul;116(1):237–239. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181e8b087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iriye BK, Huang WH, Condon J, Hancock L, Hancock JK, Ghamsary M, et al. Implementation of a laborist program and evaluation of the effect upon cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Sep;209(3):251.e1–251.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Srinivas SK, Lorch SA. The laborist model of obstetric care: we need more evidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Jul;207(1):30–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Declercq E. Births attended by certified nurse-midwives in the United States in 2005. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2009 Jan-Feb;54(1):95–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Renfrew MJ, McFadden A, Bastos MH, Campbell J, Channon AA, Cheung NF, et al. Midwifery and quality care: findings from a new evidence-informed framework for maternal and newborn care. Lancet. 2014 Sep 20;384(9948):1129–1145. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60789-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johantgen M, Fountain L, Zangaro G, Newhouse R, Stanik-Hutt J, White K. Comparison of Labor and Delivery Care Provided by Certified Nurse-Midwives and Physicians: A Systematic Review, 1990 to 2008. Womens Health Issues. 2014 Sep;22(1):e73–e81. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davis LG, Riedmann GL, Sapiro M, Minogue JP, Kazer RR. Cesarean section rates in low-risk private patients managed by certified nurse-midwives and obstetricians. J Nurse Midwifery. 1994 Mar-Apr;39(2):91–97. doi: 10.1016/0091-2182(94)90016-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harvey S, Jarrell J, Brant R, Stainton C, Rach D. A randomized, controlled trial of nurse-midwifery care. Birth. 1996 Sep;23(3):128–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536x.1996.tb00473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nijagal MA, Kuppermann M, Nakagawa S, Cheng Y. Two practice models in one labor and delivery unit: association with cesarean delivery rates. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Nov 13; doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nijagal MA, Wice M. Expanding access to midwifery care: using one practice's success to create community change. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2012 Jul-Aug;57(4):376–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-2011.2011.00153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cook TD, Campbell DT. Quasi-experimentation: Design and analysis issues for field settings. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shadish WR, Cook TD, Campbell DT. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sacramento, CA: Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development; 2013. [cited April 1, 2014]. Hospital Annual Utilization Data. [Internet] [updated November 8, 2013 9:39 AM; Available from: http://www.oshpd.ca.gov/hid/Products/Hospitals/Utilization/Hospital_Utilization.html. [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacDorman M, Declercq E, Menacker F. Recent trends and patterns in cesarean and vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC) deliveries in the United States. Clin Perinatol. 2011 Jun;38(2):179–192. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kozhimannil KB, Law MR, Virnig BA. Cesarean delivery rates vary tenfold among US hospitals; reducing variation may address quality and cost issues. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013 Mar;32(3):527–535. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.