Abstract

Background

Pediatric contrast-enhanced MR angiography is often limited by respiration, other patient motion and compromised spatiotemporal resolution.

Objective

To determine the reliability of a free-breathing spatiotemporally accelerated 3-D time-resolved contrast enhanced MR angiography method for depicting abdominal arterial anatomy in young children.

Materials and methods

With IRB approval and informed consent, we retrospectively identified 27 consecutive children (16 males and 11 females; mean age: 3.8 years, range: 14 days to 8.4 years) referred for contrast enhanced MR angiography at our institution, who had undergone free-breathing spatiotemporally accelerated time-resolved contrast enhanced MR angiography studies. An radio-frequency-spoiled gradient echo sequence with Cartesian variable density k-space sampling and radial view ordering, intrinsic motion navigation and intermittent fat suppression was developed. Images were reconstructed with soft-gated parallel imaging locally low-rank method to achieve both motion correction and high spatiotemporal resolution. Quality of delineation of 13 abdominal arteries in the reconstructed images was assessed independently by two radiologists on a five-point scale. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals of the proportion of diagnostically adequate cases were calculated. Interobserver agreements were also analyzed.

Results

Eleven out of 13 arteries achieved acceptable image quality (mean score range: 3.9–5.0) for both readers. Fair to substantial interobserver agreement was reached on nine arteries.

Conclusion

Free-breathing spatiotemporally accelerated 3-D time-resolved contrast enhanced MR angiography frequently yields diagnostic image quality for most abdominal arteries for pediatric contrast enhanced MR angiography.

Keywords: Children, Compressed sensing, Magnetic resonance angiography, Parallel imaging, Spatiotemporal acceleration

Introduction

Contrast-enhanced MR angiography is ideal for pediatric abdominal vascular imaging due to the lack of ionizing radiation [1–5]. However, pediatric abdominal contrast enhanced MR angiography is often limited by motion and compromised spatiotemporal resolution. Not only are anatomical structures smaller than those in adults, but also circulatory dynamics are faster. Precise timing is required to synchronize image acquisition with the arrival of contrast agents. To reduce patient motion, general anesthesia that is sufficiently deep to obtain periods of suspended respiration is often necessary [6]. However, general anesthesia introduces associated risks of complications that may defer the use of MRI despite the benefits. In many practices, CT is utilized instead of MR angiography in young children to avoid general anesthesia.

To achieve desired spatiotemporal resolution, contrast enhanced MR angiography data acquisition needs to be accelerated. Parallel imaging (SENSE [sensitivity encoding], GRAPPA [generalized autocalibrating partial parallel acquisition], etc.) can reduce the scan time significantly by using coil arrays to acquire data simultaneously [7–9]. Compressed sensing can also accelerate data acquisition by exploiting intrinsic sparsity of the acquired images [10]. Both parallel imaging and compressed sensing can be used to accelerate contrast enhanced MR angiography at each time point. Since a series of images with the same anatomy but different image contrast is acquired in contrast enhanced MR angiography, methods that exploit the spatiotemporal correlation of the dynamic image series, such as keyhole, various k-t (K-space domain and time doman) methods, and low-rank methods, can also be applied [11–19]. Promising results in contrast enhanced MR angiography have been achieved using parallel imaging, compressed sensing and low-rank methods or the combination of these methods [20–29].

To limit respiratory motion, breath-holding acquisition can be applied, but deep general anesthesia with suspended respiration is often required. To reduce the depth of general anesthesia, a free-breathing acquisition is preferred. Respiratory triggering/gating can achieve good image quality, but the spatiotemporal resolution is usually reduced by at least three-fold compared to breath-holding acquisition [30]. Free-breathing acquisition with advanced retrospective motion compensation, including respiratory binning and soft gating, can achieve higher scan efficiency and image quality comparable to respiratory-triggered acquisition [31–37]. Acquisition trajectory can also be modified to mitigate motion artifacts [38–41]. This modification often requires sampling the center of k-space more than once during the data acquisition and view ordering strategies (e.g., radial view ordering [41]) insensitive to motion artifacts. Variable density sampling patterns are also desirable for compressed sensing and low-rank reconstructions [10, 20].

Recently, a fast free-breathing time-resolved contrast enhanced MR angiography technique with high spatiotemporal resolution has been developed [42]. This method exploits the spatiotemporal correlation in the contrast enhanced MR angiography image series and combines parallel imaging for acceleration and soft gating for motion compensation. Feasibility of pediatric abdominal dynamic contrast enhanced MRI with reduced general anesthesia has been validated [42]. In this work, we aim to determine the reliability of this method of free-breathing abdominal time-resolved contrast enhanced MR angiography to depict various abdominal arteries with adequate diagnostic image quality in young children.

Materials and methods

Patient recruitment

With institutional review board approval, 27 consecutive patients (16 males and 11 females) referred for abdominal contrast enhanced MR angiography at 3 T at our institution from November 2013 to January 2014 were retrospectively identified. Patient demographics and clinical indications are summarized in Table 1. The patient ages ranged from 14 days to 8.4 years (mean: 3.8 years). Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Table 1.

Demographics of patients, acquisition parameters, respiratory support and clinical indications

| Subject number | Age (years) | Gender | Slice thickness (mm) | FOV (cm) | Matrix size | Temporal resolution (s) | Respiratory support* | Clinical indication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6.9 | M | 2.4 | 38×30 | 320×180×80 | 8.6 | LMA | Metastatic neuroblastoma |

| 2 | 6.3 | F | 2.0 | 32×26 | 320×180×80 | 8.8 | NC | Tuberous sclerosis |

| 3 | 4.1 | M | 2.4 | 30×24 | 320×180×66 | 7.9 | ETT | Hepatoblastoma |

| 4 | 3.7 | M | 2.4 | 38×30 | 320×180×80 | 8.6 | ETT | B- Thalassemia |

| 5 | 6.0 | F | 2.4 | 32×26 | 320×180×64 | 7.6 | None | Vaginal rhabdomyosarcoma |

| 6 | 3.8 | M | 2.4 | 32×26 | 320×180×68 | 7.7 | LMA | Hepatoblastoma |

| 7 | 0.5 | F | 2.0 | 26×18 | 320×156×60 | 7.0 | ETT | Patent ductus arteriosus |

| 8 | 2.8 | M | 2.4 | 30×21 | 320×156×56 | 6.1 | NC | Neuroblastoma |

| 9 | 2.4 | F | 2.0 | 38×30 | 320×180×80 | 5.5 | LMA | End-stage renal disease |

| 10 | 0.5 | M | 1.8 | 26×21 | 320×180×80 | 9.3 | NC | Liver transplant |

| 11 | 1.7 | M | 2.0 | 28×22 | 320×180×80 | 9.2 | ETT | Rhabdoid tumor |

| 12 | 3.3 | M | 2.4 | 32×26 | 320×180×68 | 7.7 | LMA | Abdominal mass |

| 13 | 2.8 | M | 2.4 | 32×24 | 320×168×64 | 7.4 | NC | Wilms tumor |

| 14 | 1.0 | F | 2.0 | 30×24 | 320×180×74 | 8.3 | LMA | Neuroblastoma |

| 15 | 2.6 | F | 2.4 | 30×24 | 320×180×68 | 8.1 | ETT | Hepatoblastoma |

| 16 | 0.0 | M | 1.0 | 26×26 | 320×192×110 | 13.5 | ETT | Neuroblastoma |

| 17 | 6.9 | M | 2.4 | 32×24 | 320×168×72 | 7.9 | NC | Neuroblastoma |

| 18 | 2.2 | F | 1.4 | 32×26 | 320×180×120 | 14.1 | ETT | Langerhans cell histiocytosis |

| 19 | 8.4 | F | 2.4 | 34×27 | 320×180×60 | 6.7 | None | Medulloblastoma |

| 20 | 7.3 | F | 2.0 | 32×26 | 320×180×80 | 8.8 | NC | Wilms tumor |

| 21 | 4.2 | F | 2.4 | 32×26 | 320×180×70 | 8.3 | LMA | Wilms tumor |

| 22 | 2.7 | M | 2.0 | 30×24 | 320×180×80 | 9.2 | LMA | Mature teratoma |

| 23 | 7.1 | M | 2.0 | 38×30 | 320×180×80 | 8.1 | NC | Rhabdomyosarcoma |

| 24 | 3.2 | M | 2.4 | 34×26 | 320×168×82 | 9.4 | ETT | Pancreaticoblastoma |

| 25 | 7.2 | M | 2.4 | 34×27 | 320×180×76 | 8.9 | NC | Neuroblastoma |

| 26 | 1.9 | F | 2.4 | 30×24 | 320×180×66 | 7.9 | NC | Sacrococcygeal teratoma |

| 27 | 4.0 | M | 2.4 | 38×30 | 320×180×80 | 8.6 | NC | Sickle cell disease |

ETT endotracheal tube, F female, FOV field of view, LMA laryngeal mask, M male, NC nasal cannula

Image acquisition

All imaging was performed on a 3-T MR750 scanner (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI, USA) with a commercially available 32-channel cardiac coil or torso coil, depending on patient size. A multiphase 3-D SPGR (spoiled gradient recalled acquisition in the steady state) sequence with intermittent spectrally selective fat-inversion pulses and variable density sampling patterns with radial view ordering [41] was used during the contrast injection. Motion was estimated using a Butterfly modification of the pulse sequence for self-navigation [34]. Prescribed acquisition parameters were minimum echo time (TE) 1.2–1.4 ms, repetition time (TR) 3.0–3.4 ms, fat inversion time 9.0 ms, bandwidth ±100 kHz, slice thickness 1.0–2.4 mm with non-overlapping slices, S/I field of view 26–38 cm (coverage from diaphragm to ischial tuberosities), and average total acceleration factor (per phase) 6.2 (range: 4.9–10.3). The average acquisition time for each temporal phase was 8.5 s (range: 5.5–14.1 s) and 18 temporal phases in total were acquired for all cases (average scan time: 2:33). All imaging was performed free-breathing and in the coronal plane. Different types of respiratory support (nasal cannula: NC; laryngeal mask: LMA; endotracheal tube: ETT) were applied depending on the depth of general anesthesia decided by anesthesiologists. No respiratory support was used when the patient was not sedated (awake). The details of acquisition parameters and respiratory support are shown in Table 1. Single dose gadobutrol, gadobenate or ferumoxytol was diluted as necessary in saline to ensure a total volume of 10 mL and power injected intravenously at 1mL/s rate when possible and hand injected at approximately 1 mL/s when not. Contrast injection was initiated after the acquisition of the first temporal phase.

Image reconstruction

Because variable density sampling patterns with radial view ordering were applied during data acquisition, the center of k-space was sampled multiple times and motion artifacts were already mitigated. To reduce residual motion artifacts, respiratory motion was first estimated. For each free-breathing MR angiography dataset, respiratory motion in the superior/inferior direction was calculated and assumed to be the dominant motion. Soft-gating weights were calculated based on the estimated motion and applied to the acquired data for motion compensation [37]. Soft gating effectively reduces motion artifacts by assigning a motion-weighted data consistency in the reconstruction: k-space data with very little motion corruption were assumed to be motion-free and assigned to a weighting of 1; k-space data with significant motion corruption were assigned to a weighting close to zero. Data points with weightings less than 1 or have not been acquired would rely on the reconstruction to estimate the corresponding values without motion corruption. Locally low-rank parallel imaging method can recover highly undersampled contrast enhanced MR angiography datasets by exploiting the spatiotemporal correlation and incorporating the different coil sensitivities of the coil arrays [16]. Combined soft-gated locally low-rank parallel imaging was performed to reconstruct the undersampled dataset in this study [42]. Coil compression from 32 coils to 6 virtual coils was performed prior to image reconstruction to shorten the reconstruction time [43]. The reconstruction was implemented online with an average reconstruction time of approximately 5 min on a dedicated workstation (2 Intel Xeon 2.3GHz 12-core processors and 256 GB RAM). We also implemented another online parallel imaging compressed sensing reconstruction that produces images at approximately one-third of the final temporal resolution (less than 30 s reconstruction time per temporal phase) before releasing the patients [27]. This permits assessment of anatomical coverage, adequacy of contrast and quality of fat suppressions.

Image evaluation

Two pediatric radiologists (S.S.V. and A.H. with 9 and 5 years of clinical experience with MR imaging. respectively), who were blinded to patient history/diagnoses, contrast agent and the depth of general anesthesia (respiratory support), independently assessed the reconstructions qualitatively. The overall image quality of 13 abdominal arteries were assessed on a five-point scale: celiac artery; left gastric artery; common, proper and right hepatic arteries; splenic artery; right phrenic artery; superior and inferior mesenteric arteries; renal artery, and right common, internal and external iliac arteries. Right renal artery was graded when present; otherwise, left renal artery was graded instead. These arteries were selected to assess the delineation of the arterial anatomy by the presented method within the entire imaging volume, including arteries of varying size and those that were expected to have varying degrees of motion. Some of the selected arteries may not have significant clinical relevance. The scoring criteria are shown in Table 2. Only the contrast enhanced MR angiography images were reviewed by the radiologists.

Table 2.

Scoring criteria for image assessment of abdominal arteries

| Score | Overall image quality |

|---|---|

| 1 (Non-diagnostic) | Not seen |

| 2 (Limited) | Blurred; cannot judge presence of stenosis |

| 3 (Diagnostic) | Stenosis can be graded |

| 4 (Good) | Most of the borders sharply delineated |

| 5 (Excellent) | All of the borders sharply delineated |

Mean scores and the proportions of cases with acceptable image quality (score no less than three) of both readers were calculated for all abdominal arteries. The 95% confidence intervals of the proportions were also calculated using the Wilson score method with continuity correction [44].

Interobserver agreement between the two readers for all assessments was analyzed using weighted kappa coefficients. The weighted kappa coefficients were interpreted as almost perfect (0.8–1), substantial (0.6–0.8), moderate (0.4–0.6), fair (0.2–0.4), slight (0–0.2) and poor (<0).

Results

Depending on the level of general anesthesia administrated, different respiratory support was applied for the recruited patients: 8 ETT, 7 LMA, 10 NC, and 2 none (awake). Representative MR angiography maximum intensity projection (MIP) images from a 4-year-old girl with LMA are shown in Fig. 1. Excellent image quality was achieved in this example. Small arteries, such as second-order branches of hepatic arteries, were sharply delineated in the reconstructed images. High temporal resolution was reflected by the rapid contrast dynamics captured in the liver and kidney on the time-resolved MR angiography images series. To demonstrate the evaluation of different abdominal arteries, representative images from a 3-year-old boy with ETT are shown in Fig. 2. MR angiography images of four patients with different respiratory support are shown in Fig. 3. Though the depth of general anesthesia varied, comparable image quality was observed in all these example cases. One patient in this study had metallic implants, which created an imaging artifact that limited the delineation of most arteries. The MR angiography image of this patient is shown in Fig. 3.

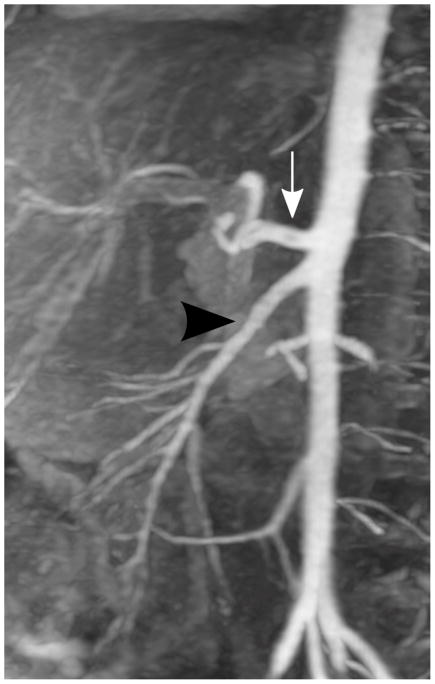

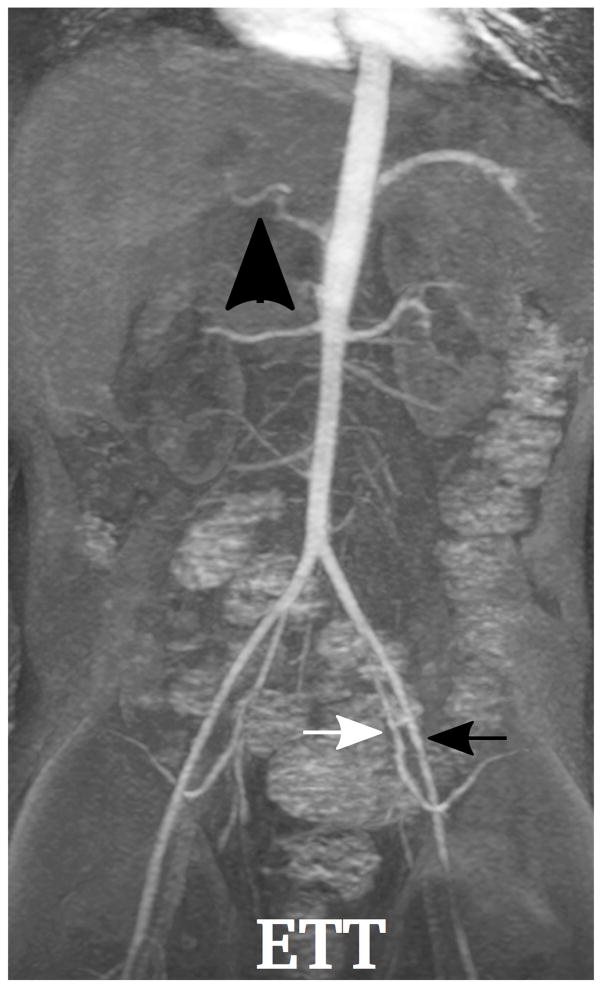

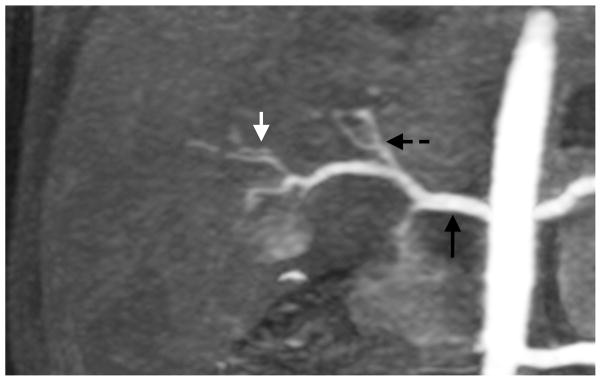

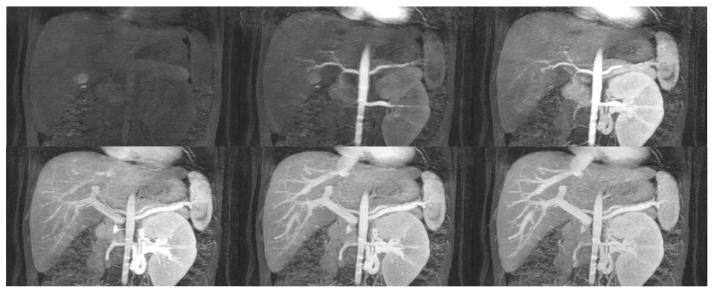

Fig. 1.

Representative images of a 4-year-old girl with laryngeal mask. (a) MIP image of the entire field of view in the arterial phase; (b) cropped and zoomed image: up to second-order hepatic arteries (white, black and dashed arrows) are sharply delineated, and (c) pre-contrast and five sequential MIP images after contrast injection reflect high temporal resolution. The scores of the common hepatic artery, proper hepatic artery and right hepatic artery were 5, 4 and 4, respectively, by reader 1, and 5, 5 and 5 by reader 2

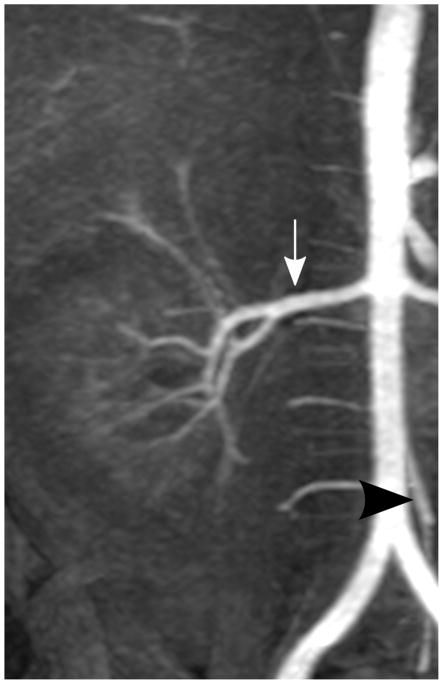

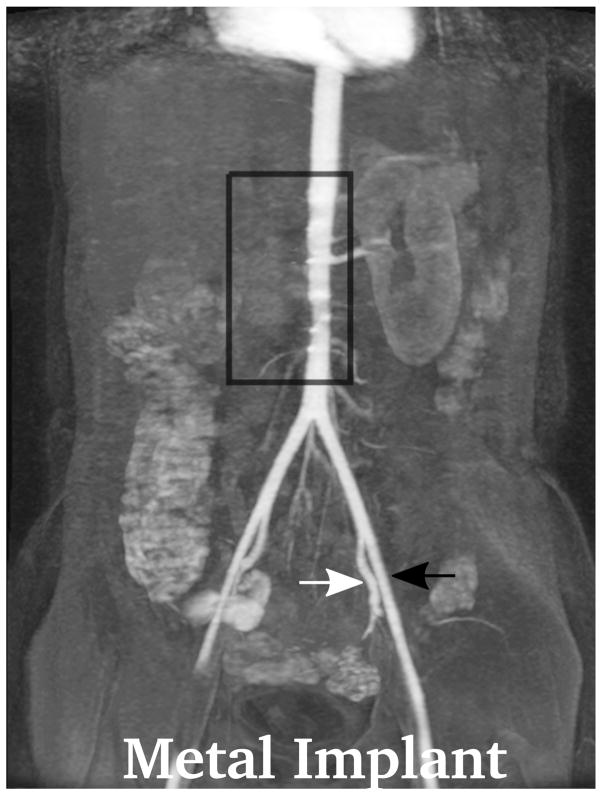

Fig. 2.

Representative MIP images of different abdominal arteries in the evaluation of a 3-year-old boy with endotracheal tube: (a) celiac artery (white arrow, scored 5 and 5 by readers 1 and 2, respectively) and superior mesenteric artery (black arrowhead, scored 5 and 5 by readers 1 and 2, respectively); (b) right renal artery (white arrow, scored 5 and 5 by readers 1 and 2, respectively) and inferior mesenteric artery (black arrowhead, scored 5 and 5 by readers 1 and 2, respectively); (c) splenic artery (white arrow, scored 5 and 4 by readers 1 and 2, respectively); (d) right phrenic artery (white arrowhead, scored 2 and 1 by readers 1 and 2, respectively)

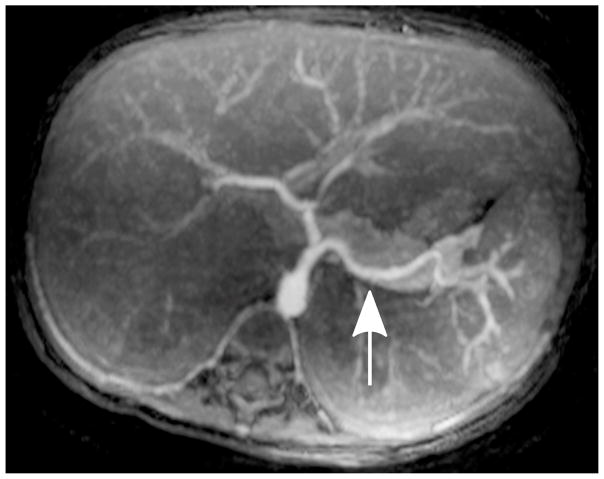

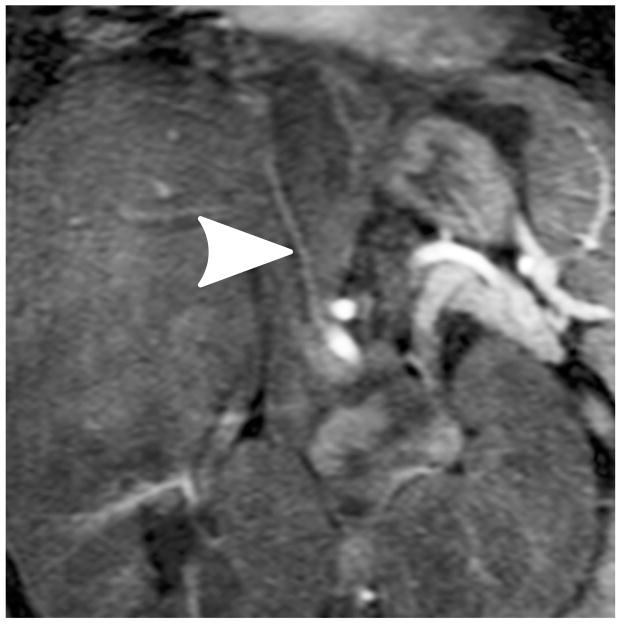

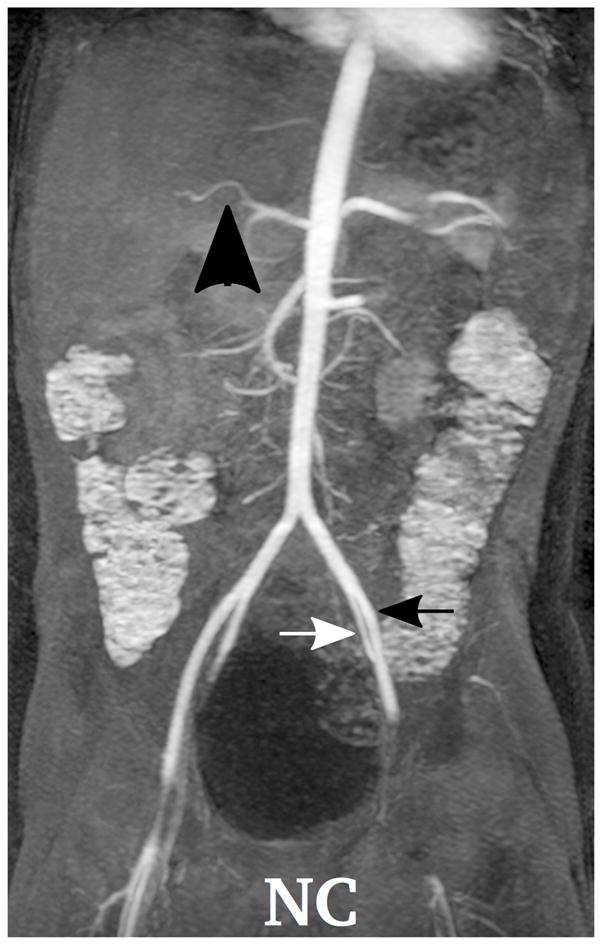

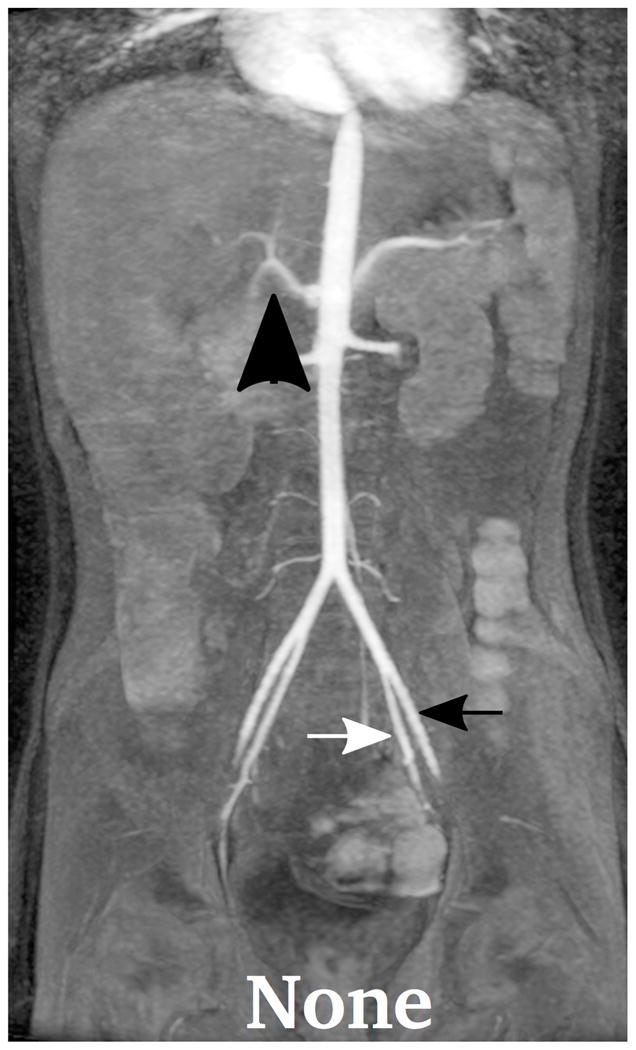

Fig. 3.

Demonstration of the MR angiography images under different respiratory support: (a) a 4-year-old boy with endotrachial tube, (b) a 2-year-old girl with laryngeal mask, (c) a 2-year-old boy with nasal cannula, and (d) a 8-year-old girl without any respiratory support (awake). Excellent image quality was observed for all these cases, e.g., common hepatic arteries (a-d: black arrowhead, scored 5, 5, 5 and 4, respectively, by reader 1, and 4, 3, 5 and 5 by reader 2). The MR angiography image of a 6-year-old boy with metallic implant is shown in (e). Due to the metal artifacts, some of the arteries near the metallic implants (highlighted region) cannot be visualized well. Arteries that are far from the metallic implants, e.g., left external (a-e: black arrows) and internal (a-e: white arrows) iliac arteries, were not significantly affected

The mean scores, proportions of acceptable cases and 95% confidence interval for the proportion with acceptable image quality are shown in Table 3. Both readers gave high scores for the majority of the arteries evaluated. Except for the left gastric artery for reader 1 and the right hepatic artery for both readers, the mean score of all the other arteries is no less than 3.9 for both readers. The percentage of cases with different scores is shown as bar graphs in Fig. 4.

Table 3.

Mean scores of image assessments and proportions with diagnostically acceptable image quality for each abdominal artery

| Structures | Mean score | Number of cases (acceptable proportions, 95% confidence interval of acceptable proportions) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reader 1 | Reader 2 | Reader 1 | Reader 2 | |

| Celiac artery | 4.9 | 4.8 | 26 (96%, 79–100%) | 27 (100%, 85–100%) |

| Left gastric artery | 2.9 | 3.7 | 20 (74%, 54–90%) | 24 (89%, 70–100%) |

| Common hepatic artery | 4.5 | 4.1 | 26 (96%, 79–100%) | 26 (96%, 79–100%) |

| Proper hepatic artery | 3.7 | 4.0 | 22 (81%, 61–95%) | 24 (89%, 70–100%) |

| Right hepatic artery | 3.9 | 3.9 | 24 (89%, 70–100%) | 23 (85%, 65–97%) |

| Splenic artery | 4.5 | 4.0 | 25 (92%, 74–100%) | 26 (96%, 79–100%) |

| Right phrenic artery | 2.0 | 2.1 | 7 (26%, 12–47%) | 9 (33%, 17–54%) |

| Superior mesenteric artery | 4.8 | 4.6 | 26 (96%, 79–100%) | 27 (100%, 85–100%) |

| Renal artery* | 4.9 | 4.6 | 26 (96%, 79–100%) | 26 (96%, 79–100%) |

| Inferior mesenteric artery | 4.0 | 4.4 | 24 (89%, 70–100%) | 26 (96%, 79–100%) |

| Right common iliac artery | 5.0 | 4.9 | 27 (100%, 85–100%) | 27 (100%, 85–100%) |

| Right internal iliac artery | 5.0 | 4.5 | 27 (100%, 85–100%) | 27 (100%, 85–100%) |

| Right external iliac artery | 5.0 | 4.9 | 27 (100%, 85–100%) | 27 (100%, 85–100%) |

Right renal artery was scored when present; otherwise, left renal artery was scored instead.

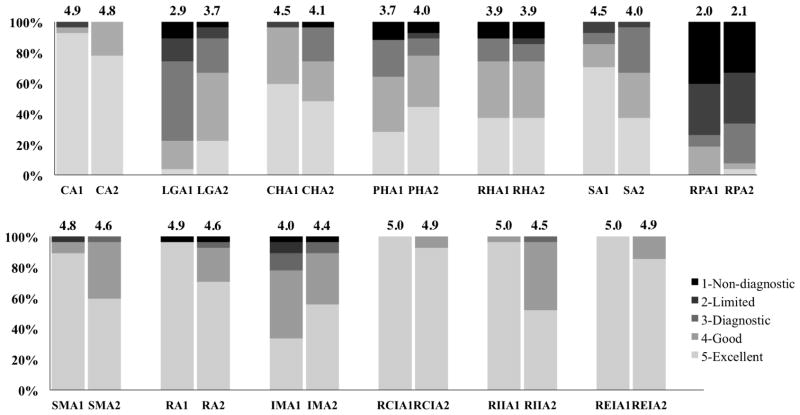

Fig. 4.

Proportions of cases with different scores for all arteries evaluated. The results of the assessment from both readers are shown side-by-side for each artery, with the average scores shown on top of the bar graphs. For example, CA1 represents the score for celiac artery from reader 1. Based on the assessment results, diagnostic image quality for most abdominal arteries (except left gastric artery and right phrenic artery) was achieved. CA celiac artery, CHA common hepatic artery, IMA inferior mesenteric artery, LGA left gastric artery, PHA proper hepatic artery, RA renal artery, RHA right hepatic artery, RCIA right common iliac artery, REIA right external iliac artery, RIIA right internal iliac artery, RPA right phrenic artery, SA splenic artery, SMA superior mesenteric artery

Interobserver agreement results are shown in Table 4. Fair to substantial interobserver agreement was reached for most of the evaluated arteries except for the superior mesenteric artery, right common iliac artery, right internal iliac artery and right external iliac artery.

Table 4.

Interobserver agreement results using weighted kappa coefficients between reader 1 and reader 2 for overall image quality assessment of abdominal arteries

| Abdominal arteries | Result |

|---|---|

| Celiac artery | Fair |

| Left gastric artery | Fair |

| Common hepatic artery | Moderate |

| Proper hepatic artery | Moderate |

| Right hepatic artery | Substantial |

| Splenic artery | Moderate |

| Right phrenic artery | Substantial |

| Superior mesenteric artery | Slight |

| Renal artery | Substantial |

| Inferior mesenteric artery | Fair |

| Right common iliac artery | Poor |

| Right internal iliac artery | Poor |

| Right external iliac artery | Poor |

Discussion

This study evaluated the clinical performance of a free-breathing spatiotemporally accelerated 3-D time-resolved MR angiography method in young children. Locally low-rank parallel imaging method was used to reconstruct highly accelerated contrast enhanced MR angiography datasets. Cartesian acquisition with variable density sampling and radial view ordering was applied to mitigate motion artifacts. Soft gating was also applied to further reduce residual motion artifacts. With combined soft-gated parallel imaging locally low-rank reconstruction, diagnostic image quality was observed for most cases in the study. The high temporal resolution of the method also removed the need for precise timing of contrast arrival. Methods like keyhole acquire data at different spatial frequencies with different frame rates and use a view sharing strategy to reconstruct the missing data in contrast enhanced MR angiography. These methods may yield similar or better temporal resolution, but breath-holding is usually required during the data acquisition to reduce motion artifacts. The actual temporal solution is also not clearly defined because of the view sharing nature in keyhole methods.

The delineation of the majority of abdominal arteries that are routinely assessed in contrast enhanced MR angiography study was clinically acceptable in this study. The average image quality of the right phrenic artery and left gastric artery was limited. However, these arteries in our experience are not reliably well delineated in small children even when respiration is suspended, likely due to their small size. Image quality was also limited for patients with metallic implants, which also is problematic regardless of whether images are obtained with suspended respiration.

Fair to substantial interobserver agreement was achieved in nine out of the 13 arteries evaluated. For the right common iliac artery, right internal iliac artery and right external iliac artery, reader 1 gave the highest score 5 to almost all cases. This resulted in a probability of reader 1 giving a score of 5 to these arteries very close to 1. Even if the other reader agreed with reader 1 and gave the same score for the majority of cases and only gave different scores for one case, the corresponding kappa coefficient would still be very low, which was interpreted as poor interobserver agreement. The different subjective interpretation of the scoring criteria by two readers could also contribute to the fair or worse interobserver agreement.

There were several limitations of this study. Since the contrast can only be administrated once, the comparison with other acquisition methods was not possible. Previous studies have shown that combined soft-gated parallel imaging locally low-rank reconstruction can achieve image quality comparable to respiratory-triggered acquisition for abdominal viscera [42]. Therefore, we only evaluated the reconstruction using this method in this study. Motion often results in blurred delineation. Thus, the scoring criteria focused on the delineation of the arterial anatomy provided indirect assessment of residual motion artifacts. Time-resolved contrast dynamics and sharp delineation of the arterial anatomy are, in general, more difficult to achieve than the venous anatomy in contrast enhanced MR angiography. This is in part because the temporal dynamics of the arterial anatomy are faster and the structures are often smaller. Therefore, we focused on the arterial anatomy evaluation in this study. Our experience is that the venous anatomy is consistently visualized with sharp delineation, but a formal evaluation is beyond the scope of this work.

Another limitation of this study was that children with diverse clinical indications were recruited. The study was not focused on a specific disease. Since the aim of the study was to determine the reliability of the fast free-breathing time-resolved contrast enhanced MR angiography technique, the heterogeneous patient population can potentially represent different clinical circumstances. Patients with different contrast agents and respiratory support (depth of general anesthesia ) were recruited in this study, which may have confounded the results. However, they also provided a diverse dataset to show the robustness of the presented method. The sample size of cases with different respiratory support in this study was too small to analyze statistically whether comparable image quality was achieved for different respiratory support. This will be the subject of future work.

Conclusion

Pediatric free-breathing time-resolved contrast enhanced MR angiography using spatiotemporal acceleration and motion correction frequently yields diagnostic image quality for most abdominal arteries. Further studies will be pursued to determine if this method is able to significantly reduce the depth of general anesthesia needed for pediatric contrast enhanced MR angiography.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants R01 EB009690, R01 EB019241, P41 EB015891, the Tashia and John Morgridge Faculty Scholars Fund, and GE Healthcare.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest T. Zhang, J. Y. Cheng, M. T. Alley, M. Lustig, J. M. Pauly and S. S. Vasanawala collaborate on research with GE Healthcare.

References

- 1.Olsen ØE. Imaging of abdominal tumours: CT or MRI? Pediatr Radiol. 2008;38 (Suppl 3):452–458. doi: 10.1007/s00247-008-0846-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Darge K, Anupindi SA, Jaramillo D. MR imaging of the abdomen and pelvis in infants, children, and adolescents. Radiology. 2011;261:12–29. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11101922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chung T. Magnetic resonance angiography of the body in pediatric patients: experience with a contrast-enhanced time-resolved technique. Pediatr Radiol. 2005;35:3–10. doi: 10.1007/s00247-004-1219-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grist TM, Thornton FJ. Magnetic resonance angiography in children: technique, indications, and imaging findings. Pediatr Radiol. 2005;35:26–39. doi: 10.1007/s00247-004-1350-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vasanawala SS, Lustig M. Advances in pediatric body MRI. Pediatr Radiol. 2011;41 (Suppl 2):549–554. doi: 10.1007/s00247-011-2103-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sury MR, Smith JH. Deep sedation and minimal anesthesia. Paediatr Anaesth. 2008;18:18–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2007.02379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pruessmann KP, Weiger M, Scheidegger MB, Boesiger P. SENSE: sensitivity encoding for fast MRI. Magn Reson Med. 1999;42:952–962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Griswold MA, Jakob PM, Heidemann RM, et al. Generalized autocalibrating partially parallel acquisitions (GRAPPA) Magn Reson Med. 2002;47:1202–1210. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lustig M, Pauly JM. SPIRiT: iterative self-consistent parallel imaging reconstruction from arbitrary k-space. Magn Reson Med. 2010;64:457–471. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lustig M, Donoho D, Pauly JM. Sparse MRI: The application of compressed sensing for rapid MR imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2007;58:1182–1195. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pedersen H, Kozerke S, Ringgaard S, et al. k-t PCA: temporally constrained k-t BLAST reconstruction using principal component analysis. Magn Reson Med. 2009;62:706–716. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liang ZP. Spatiotemporal imaging with partially separable functions. Proceedings of IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging; Arlington, VA. 2007. pp. 988–991. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lingala SG, Hu Y, DiBella E, Jacob M. Accelerated dynamic MRI exploiting sparsity and low-rank structure: k-t SLR. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2011;30:1042–1054. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2010.2100850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haldar JP, Liang ZP. Low-rank approximations for dynamic imaging. Proceedings of IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging; Chicago. 2011. pp. 1052–1055. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trzasko J, Manduca A. Local versus global low-rank promotion in dynamic MRI series reconstruction. Proceedings of the 19th Annual Meeting of ISMRM; Montréal. 2011. p. 4371. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang T, Alley MT, Lustig M, et al. Fast 3D DCE-MRI with sparsity and low-rank enhanced SPIRiT (SLR-SPIRiT). Proceedings of the 21st Annual Meeting of ISMRM; Salt Lake City. 2013. p. 2624. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao B, Haldar JP, Christodoulou AG, Liang ZP. Image reconstruction from highly undersampled (k, t)-space data with joint partial separability and sparsity constraints. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2012;31:1809–1820. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2012.2203921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Vaals JJ, Brummer ME, Dixon WT, et al. “Keyhole” method for accelerating imaging of contrast agent uptake. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1993;3:671–675. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880030419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsao J, Boesiger P, Pruessmann KP. k-t BLAST and k-t SENSE: dynamic MRI with high frame rate exploiting spatiotemporal correlations. Magn Reson Med. 2003;50:1031–1042. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jung H, Sung K, Nayak KS, et al. k-t FOCUSS: a general compressed sensing framework for high resolution dynamic MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2009;61:103–116. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang F, Lin W, Duensing GR, Reykowski A. k-t sparse GROWL: sequential combination of partially parallel imaging and compressed sensing in k-t space using flexible virtual coil. Magn Reson Med. 2012;68:772–782. doi: 10.1002/mrm.23293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feng L, Srichai MB, Lim RP, et al. Highly accelerated real-time cardiac cine MRI using k-t SPARSE-SENSE. Magn Reson Med. 2013;70:64–74. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trzasko JD, Haider CR, Borisch EA, et al. Sparse-CAPR: Highly accelerated 4D CE-MRA with parallel imaging and nonconvex compressive sensing. Magn Reson Med. 2011;66:1019–1032. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang K, Busse RF, Holmes JH, et al. Interleaved variable density sampling with a constrained parallel imaging reconstruction for dynamic contrast-enhanced MR angiography. Magn Reson Med. 2011;66:428–436. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muthupillai R, Vick GW, III, Flamm SD, Chung T. Time-resolved contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance angiography in pediatric patients using sensitivity encoding. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2003;17:559–564. doi: 10.1002/jmri.10292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vasanawala SS, Alley MT, Hargreaves BA, et al. Improved pediatric MR imaging with compressed sensing. Radiology. 2010;256:607–616. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10091218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang T, Chowdhury S, Lustig M, et al. Clinical performance of contrast enhanced abdominal pediatric MRI with fast combined parallel imaging compressed sensing reconstruction. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2014;40:13–25. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hong TS, Greer ML, Grosse-Wortmann L, et al. Whole-body MR angiography: initial experience in imaging pediatric vasculopathy. Pediatr Radiol. 2011;41:769–778. doi: 10.1007/s00247-010-1958-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haldar JP. Low-rank modeling of local k-space neighborhoods (LORAKS) for constrained MRI. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2014;33:668–681. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2013.2293974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ehman RL, McNamara MT, Pallack M, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging with respiratory gating: techniques and advantages. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1984;143:1175–1182. doi: 10.2214/ajr.143.6.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Batchelor PG, Atkinson D, Irarrazaval P, et al. Matrix description of general motion correction applied to multishot images. Magn Reson Med. 2005;54:1273–1280. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Odille F, Vuissoz PA, Marie PY, Felblinger J. Generalized reconstruction by inversion of coupled systems (GRICS) applied to free-breathing MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2008;60:146–157. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buerger C, Schaeffter T, King AP. Hierarchical adaptive local affine registration for fast and robust respiratory motion estimation. Med Image Anal. 2011;15:551–564. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2011.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cheng JY, Alley MT, Cunningham CH, et al. Nonrigid motion correction in 3D using autofocusing with localized linear translation. Magn Reson Med. 2012;68:1785–1797. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnson KM, Block WF, Reeder SB, Samsonov A. Improved least squares MR image reconstruction using estimates of k-space data consistency. Magn Reson Med. 2012;67:1600–1608. doi: 10.1002/mrm.23144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Forman C, Piccini D, Grimm R, et al. Reduction of respiratory motion artifacts for free-breathing whole-heart coronary MRA by weighted iterative reconstruction. Magn Reson Med. 2015;73:1885–1895. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheng JY, Zhang T, Ruangwattanapaisarn N, et al. Free-breathing pediatric MRI with nonrigid motion correction and acceleration. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2014 doi: 10.1002/jmri.24785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jhooti P, Wiesmann F, Taylor AM, et al. Hybrid ordered phase encoding (HOPE): an improved approach for respiratory artifact reduction. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1998;8:968–980. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880080428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Doneva M, Stehning C, Nehrke K, Börnert P. Improving scan efficiency of respiratory gated imaging using compressed sensing with 3D Cartesian golden angle sampling. Proceedings of the 19th Annual Meeting of ISMRM; Montréal. 2011. p. 641. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gdaniec N, Eggers H, Börnert P, et al. Robust abdominal imaging with incomplete breath-holds. Magn Reson Med. 2014;71:1733–1742. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cheng JY, Zhang T, Alley MT, et al. Variable-density radial view-ordering and sampling for time-optimized 3D Cartesian imaging. Proceedings of the ISMRM Workshop on Data Sampling and Image Reconstruction; Sedona. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang T, Cheng JY, Potnick AG, et al. Fast pediatric 3D free-breathing abdominal dynamic contrast enhanced MRI with high spatiotemporal resolution. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2015;41:460–473. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang T, Pauly JM, Vasanawala SS, Lustig M. Coil compression for accelerated imaging with Cartesian sampling. Magn Reson Med. 2013;69:571–582. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Newcombe RG. Two-sided confidence intervals for the single proportion: comparison of seven methods. Statist Med. 1998;17:857–872. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19980430)17:8<857::aid-sim777>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]