Abstract

Commercial sweet orange cultivars lack resistance to Huanglongbing (HLB), a serious phloem limited bacterial disease that is usually fatal. In order to develop sustained disease resistance to HLB, transgenic sweet orange cultivars ‘Hamlin’ and ‘Valencia’ expressing an Arabidopsis thaliana NPR1 gene under the control of a constitutive CaMV 35S promoter or a phloem specific Arabidopsis SUC2 (AtSUC2) promoter were produced. Overexpression of AtNPR1 resulted in trees with normal phenotypes that exhibited enhanced resistance to HLB. Phloem specific expression of NPR1 was equally effective for enhancing disease resistance. Transgenic trees exhibited reduced diseased severity and a few lines remained disease-free even after 36 months of planting in a high-disease pressure field site. Expression of the NPR1 gene induced expression of several native genes involved in the plant defense signaling pathways. The AtNPR1 gene being plant derived can serve as a component for the development of an all plant T-DNA derived consumer friendly GM tree.

Introduction

In the United States, Huanglongbing (HLB) is a serious disease of citrus associated with the phloem limited bacterium Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus (CLas) [1]. This disease is spread by the Asian citrus psyllid (ACP) vector, Diaphorina citri (Kuwayama) [2]. HLB was first detected in the United States in August 2005 and since then has rapidly moved into several citrus producing areas [3, 4]. Tree decline is usually preceded by a decline in the quality of the fruit and fruit drop. Fruit from infected trees are smaller, yield less juice, have higher acidity and lower sugar and peel color than fruits from uninfected trees [5]. Infected citrus trees will irrevocably decline. Currently, HLB management consists of preventing trees from becoming infected [4]. Prevention includes protection of the young flush from the psyllid vector [6] or destruction of infected plant material to prevent further spread of the disease. Due to the lack of rapid curative methods to control HLB, prevention of new infections is essential in HLB management [7]. New infections could be prevented and the disease could be managed by planting trees that are tolerant or resistant to the disease [6].

Utilization of resistant germplasm to slow the spread of HLB in citrus is difficult due to the lack of commercially available resistant rootstock/scion combinations that can provide a robust protection and prevent infection. Identification and incorporation of resistance traits from tolerant Citrus spp. and Citrus relatives is a potential disease management strategy [8]. However, citrus crop improvement using conventional breeding methods is difficult and time consuming due to the long juvenile phase in citrus, which can vary from 4 to 12 years [9]. Genetic improvement of citrus through genetic engineering remains the fastest method for improvement of an existing citrus cultivars and has been a key component in the University of Florida’s genetic improvement strategy [10].

Genetic improvement of citrus using genes that allow plants to defend themselves against pathogens utilizing systemic acquired resistance (SAR) has resulted in the production of transgenic canker resistant trees [11]. SAR is a plant defense response resulting in the expression of specific defense genes that enhances innate resistance to further infection by pathogens [12]. Utilization of SAR is a novel method to employ the plant’s inherent immune system to reduce disease development and spread (Fig 1). SAR provides protection against a broad spectrum of microorganisms and is associated with the production of pathogenesis-related (PR) proteins [13]. This defense response is induced by salicylic acid (SA) [14], since plants that fail to produce salicylic acid also fail to develop SAR, nor do they express pathogenesis-related (PR) genes in the uninoculated leaves [15]. These plants are also more susceptible to pathogen infection [16]. For example transgenic Arabidopsis plants overexpressing the nahG gene encoding the SA hydroxylase enzyme are unable to accumulate SA due to its degradation by the SA hydroxylase enzyme into catechol. Such plants are very susceptible to infection by Pseudomonas syringae and Peronospora parasitica. Several Arabidopsis mutants which are salicylic acid induction-deficient are unable to accumulate SA after pathogen inoculation and are very susceptible to pathogens [17].

Fig 1. The process of systemic acquired resistance (SAR) induction in citrus.

Non-expressor of Pathogenesis Related genes 1 (NPR1) gene is a key regulator in the signal transduction pathway that leads to SAR since the npr1 mutant in Arabidopsis fails to respond to various SAR-inducing agents and exhibits very low expression of several PR genes. The NPR1 gene may act as a regulator of the transcription factor/s that controls PR gene expression [18] and mediates the salicylic acid induced expression of PR genes and SAR [19]. Plants over expressing NPR1 exhibit enhanced resistance to several pathogens [20].

We have produced and evaluated several transgenic sweet orange trees overexpressing AtNPR1 either in the phloem tissues (where HLB resides) via utilization of a phloem specific Arabidopsis sucrose-proton symporter 2 (AtSUC2) promoter or a constitutive CaMV 35S promoter for HLB resistance. Evaluation of these transgenic plants demonstrates that overexpressing the AtNPR1 can result in effective HLB resistance in citrus.

Materials and Methods

Development of plant transformation vectors

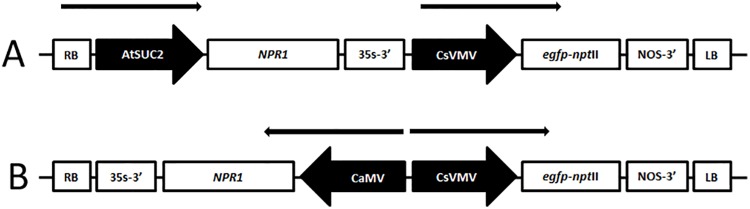

The cDNA sequence of AtNPR1 (U76707) is available in the NCBI database. Primers to amplify the AtNPR1 were designed using the bioinformatics software Vector NTI® (Life Technologies, NY, USA) to incorporate a BamHI restriction site at the 5’ end and a NotI site at the 3’ end. Total RNA was isolated from 100 mg of tissue from young, fully expanded leaves of Arabidopsis thaliana cv. Columbia using a RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA). cDNA was synthesized from 500 ng total RNA using Oligo (dT) primer and a RETROscript® RT-PCR kit as described by the manufacturer (Applied Biosystems, Austin, TX). The cDNA product was used as a template for PCR using primers as described above. The gene was excised as a BamHI/NotI fragment and inserted between a double enhanced CaMV 35S promoter (d35S) and a CaMV 35S terminator (3’CaMV) of a pUC18-derived plasmid pDR. Variations of this cloning vector containing the phloem specific Arabidopsis SUC2 promoter (NCBI accession: JQ733913) were also produced. A HindIII DNA fragment containing the expression cassette d35S (or AtSUC2)–NPR1 gene—3’CaMV were isolated and cloned into the unique HindIII site of a pBIN19-derived binary vector. This vector, containing a bifunctional nptII/egfp fusion gene has been described earlier [21]. All constructions were verified first by restriction analysis and then by DNA sequencing (Fig 2). Each vector was introduced into A. tumefaciens strain EHA105 [22] by the freeze-thaw method [23].

Fig 2. Schematic representation of T-DNA region of the binary vectors used in this study.

A) Phloem targeted gene construct B) Constitutive expression gene construct. CaMV, double enhanced (2 x -343 to -90) CaMV 35S promoter; dCsVMV, double enhanced (2 x -443 to -123) CsVMV promoter; AtSUC2, The Arabidopsis sucrose synthase promoter, egfp/nptII, bifunctional enhanced green fluorescent protein and neomycin phosphotransferase II fusion gene; NOS-3’, termination site and polyadenylation signal of the NOS transcript; 35S-3’, termination site and polyadenylation signal of the CaMV 35S transcript; RB, right border; LB, left border. The arrow represents the direction of transcription.

Transformation, selection and propagation of regenerants

Agrobacterium mediated transformation of etiolated sweet orange epicotyl segments from the cultivars ‘Hamlin’ and ‘Valencia’ were carried out as described previously [24]. EGFP-specific fluorescence in putative transgenic lines was evaluated using a Zeiss SV11 epi-fluorescence stereomicroscope equipped with a light source consisting of a 100W mercury bulb and a FITC/GFP filter set with a 480 nm excitation filter and a 515 nm longpass emission filter producing a blue light (Chroma Technology Corp., VT, USA). Transgenic ‘Hamlin’ and ‘Valencia’ sweet orange shoots are very difficult to root in vitro [24] and in this study no attempt was made to root any of our EGFP expressing transgenic lines. Instead, EGFP positive transgenic shoots were micrografted in vitro onto 1 month old Carrizo citrange (Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck × Poncirus trifoliata (L.) Raf.) nucellar rootstock seedlings. After a month of growth in vitro, the grafted shoots were potted into a peat based commercial potting medium (Metromix 500, Sun Gro Horticulture, Bellevue, WA) and acclimated under greenhouse conditions. An ex vitro micrografting technique was subsequently used to rapidly propagate transgenic plants onto 6 month old Carrizo rootstocks [25]. Plants were grown for an additional 9 to 12 months before evaluation of disease resistance. Transgenic lines with the AtSUC2-NPR1 construct had an ‘A’ added in as a suffix.

Molecular analysis of transformants

Citrus genomic DNA, was isolated from 100 mg of young transgenic leaf tissues using the GenElute™ Plant Genomic DNA Miniprep Kit (Sigma-Aldrich Corp., St. Louis, MO). Duplex PCR was carried out in a thermal cycler (MJ Research, Watertown, MA) using GoTaq® Green Master PCR Mix (Promega Corp, Madison WI) and appropriate primers (NP51, 5’ ATG GAC ACC ACC ATT GAT GGA TTC 3’ and NP32, 5’ ACG ACG ATG AGA GAG TTT ACG GTT AG 3’) and (EG-51, 5’ATG GTG AGC AAG GGC GAG GAG CTG T3’ and EG-32, 5’CTT GTA CAG CTC GTC CAT GCC GAG A3’) to confirm the presence of the AtNPR1 and egfp transgenes respectively in the genome of transgenic citrus plants. Amplified DNA fragments were electrophoresed on a 1% agarose gel and visualized under UV light. All images were recorded and digitized. All samples for the detection of Clas in transgenic citrus were analyzed by qPCR at the diagnostic laboratory of Southern Gardens Citrus in Clewiston, FL, USA. Four to five fully expanded and hardened leaves were collected from dark green colored branches. Leaves were placed in a zip lock plastic bag, kept cool and out of direct sunlight and subsequently shipped by overnight mail and processed the following day. DNA was isolated from 100 mg of leaf petiole tissue using BioSprint DNA Plant kits (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) on a BioSprint 96 instrument (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). DNA was dissolved in 100 μl of TE buffer and 2 μl were used for qPCR. qPCR was performed in a 25ul volume on an ABI7300 (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) using TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) using the Li primers [26].

Southern blot analysis was carried out for confirmation of copy number in selected transgenic citrus plants. Fifteen μg of EcoRI digested genomic DNA immobilized on a positively-charged nylon membrane was probed with a DIG-labeled AtNPR1 probe. Following hybridization to the probe, the chemiluminescence substrate CDP-Star was used for immunological detection of hybridization signals using X-ray film autography. Validation of transgene copy number was carried out using qPCR essentially as described previously [27].

RNA was isolated from 100 mg of leaf tissue using an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen Inc. Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) was performed as outlined before with minor modifications [28]. The RT-qPCR reactions were performed with a final volume of 25 μl using the TaqMan® RNA-to-CtTM one-step kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The one-step kit parameters consisted of 20 min incubation at 48°C followed by 10 min incubation at 95°C and 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min. Each qPCR contained negative and non-template/water controls in addition to the sample being tested. Experiments were repeated at least twice with three replicates and the data was analyzed using Applied Biosystems software version 2.0.6. Relative quantitation was measured using the comparative Cq method (2-ΔΔCt). The fold change in the relative expression was then determined by calculating 2-ΔΔCt [29]. The sequences of the primers and probes including the reporter fluorescent dye and dark quencher dye used in the RT-qPCR are shown in Table 1. The 18S rRNA housekeeping gene was used as an endogenous control. A set of reaction mixtures composed of one to five copies of AtNPR1 gene equivalences, was used to establish a standard curve for the evaluation of transgene copy number. The method as outlined earlier was used to prepare the set of reaction mixtures [30].

Table 1. Primers used in real-time PCR assay of transgenic citrus plants.

| Target gene | Amplicon length (bp) | Primer/probe sequence 5’→ 3’ A |

|---|---|---|

| AtNPR1 | 113 bp | TGCATCAGAAGCAACTTTGG |

| 6FAM-CGCAAAACAAGCCACTATG | ||

| GGCCTTTGAGAGAATGCTTG | ||

| CsPR1 | 88 bp | AACTCGCCTCAAGACTACCT |

| 6FAM-TCACAATTCAGCTCGAGCAGCAGTC | ||

| TGCAACTGTGTCGTTCCATA | ||

| CsPR2 | 92 bp | ACTTCGCTCAGTACCTTGTTC |

| 6FAM-ATCAACAGAGCCGGCCTTGGAAA | ||

| GGCAGTGGAAACCTTGATTTG | ||

| CsWRKY70 | 106 bp | CTGTGCTCGGTACTACTGTTAC |

| 6FAM-TGAGAAGTATCAGCAGCAGCAGGC | ||

| CGGCGATAGTCATCGGAATTA | ||

| 18S rRNA | 112 bp | TCGGGTGTTTTCACGTCTCA |

| HEX-TGGAACTCTTGGATTTTGCC | ||

| CGCCGTAGGTGAGGTAGC |

A Primer/probe sequences listed in the column include the forward primer in the first line, followed by the probe sequence in the second and the reverse primer sequence in the third line.

HLB resistance studies

Disease resistance to HLB in this study was evaluated in two ways. First, in a no-choice greenhouse evaluation study, 3 replicated clones of independent transgenic plant lines were exposed to free flying CLas positive ACP continuously for two years. Trees were routinely pruned and fertilized with both 9 month slow release and liquid fertilizer to stimulate new flush production. These trees were evaluated every 6 months for two years for the presence of HLB by qPCR as outlined before. ACP were also randomly evaluated during this study for the presence of the CLas. In the second concurrent study, selected transgenic trees and controls (consisting of 10% of the total tree population) were planted in a high disease pressure (over 90% infection rate) field site in a randomized block design experiment. In our test site, trees were planted at a narrow spacing of 2 feet to maximize land utilization (Fig 3D). These trees were similarly evaluated every 6 months for three years by qPCR for the presence of HLB. Data were analyzed to calculate standard error using MS Excel.

Fig 3. A) A set of transgenic trees with the AtNPR1 construct, B) Close-up of an HLB positive transgenic tree with the AtNPR1 construct, C) A heavily infected HLB positive control tree, D) 2 feet spacing between two adjacent trees in our field plot. Normal citrus trees are usually planted at an 8 feet spacing or more, E) Close-up of a healthy flush, F) Close-up of an HLB infected leaf.

Results

Production of genetically modified citrus plants

A total of 36 transgenic ‘Hamlin’ and ‘Valencia’ sweet orange lines expressing the 35S-NPR1 construct and 22 lines with the AtSUC2-NPR1 construct were regenerated. Transgenic plants were selected based on visual selection using EGFP fluorescence. A 20% transformation efficiency was observed using ‘Hamlin’ epicotyl segments while the transformation efficiency using ‘Valencia’ epicotyl segments were significantly lower (3%). These shoots were micrografted onto Carrizo seedlings to expedite plant growth. In vitro micro grafted shoots were hardened after 4–6 weeks of grafting and transferred to a greenhouse, After 4 months of growth, plants were analyzed for the presence of the AtNPR1 gene before being micro grafted ex vitro [25]. We did not observe major phenotypic abnormalities in a majority of the transgenic plants regenerated in this study. Two lines obtained with the 35S-NPR1 construct exhibited abnormally slow growth and were deemed unsuitable and discarded.

Verification of transgene integration, transcript accumulation and transgene copy

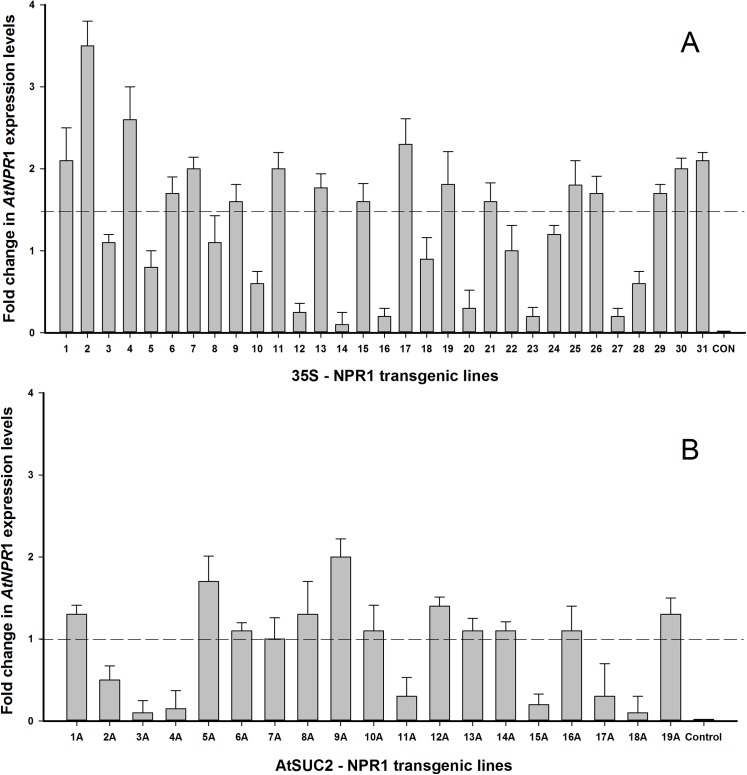

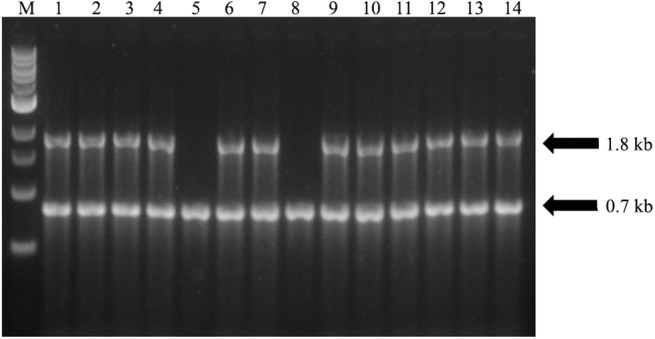

Thirty one transgenic Hamlin’ and ‘Valencia’ sweet orange lines expressing the 35S-NPR1 construct had both the egfp as well as the AtNPR1 genes incorporated into the genome as confirmed by PCR. Nineteen lines with the AtSUC2-NPR1 construct behaved similarly. Results from 14 arbitrarily selected samples are shown in Fig 4. Lines without the AtNPR1 gene were discarded and the rest analyzed for mRNA production through qRT-PCR (Fig 5). Transgenic lines with the 35S-NPR1 construct that had a 1.5 fold higher level of expression were considered to exhibit a relative high level of expression of AtNPR1. In a similar manner, transgenic lines with the weaker phloem specific AtSUC2-NPR1 construct that had a 1 fold higher level of expression were considered to exhibit a relative high level of expression of AtNPR1. We obtained 17 constitutively expressing lines (35S-NPR1) and 12 phloem specific lines (AtSUC2-NPR1) that were considered to have a relative high level of expression of AtNPR1 (Fig 5; dotted line). The transgenic lines were subsequently micrografted ex vitro to produce a population of trees for disease resistance analyses. Based on our greenhouse and field results, transgenic lines could be categorized as asymptomatic and resistant, symptomatic but tolerant or susceptible to HLB. We selected the lines 2, 4, 9A, 11A and 18 as representatives of our transgenic population for detailed molecular analyses.

Fig 4. Duplex PCR amplification products of the AtNPR1and egfp genes from genomic DNA of transgenic sweet orange citrus plants.

Transgenic lines 1 to 7 are 35S-NPR1 lines while lines 8 to 14 are AtSUC2-NPR1 lines. Amplification was carried out using gene specific primers which gave the expected 1.8 kb AtNPR1 fragment and 0.7 egfp fragment (arrows). M, 1kb DNA ladder; 1–14 are 14 randomly selected individual transgenic lines.

Fig 5. Quantification of AtNPR1 activity using qPCR.

Total RNA extracted from entire sweet orange leaf (A) or specifically midrib and petioles (B) was used as template. Sequence of primers used to amplify the AtNPR1 gene is detailed in Table 1. Transgenic lines 1 to 16 containing the 35S-NPR1 cassette are ‘Hamlin’ while lines 17 to 31 are ‘Valencia’. Transgenic lines 1 to 12 containing the AtSUC2-NPR1 cassette are ‘Hamlin’ while lines 13 to 19 are ‘Valencia’. Three independent clones were tested from each transgenic line. Total RNA from a non-transgenic plant was also included to verify the accuracy of the amplification process. Transgenic plants that had a level of expression greater than indicated by the dotted line were considered to exhibit a relative high level of expression of AtNPR1.

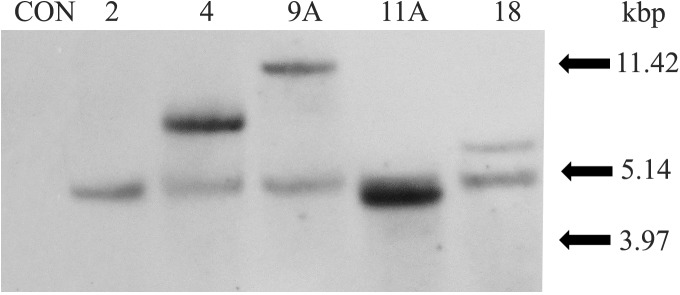

Southern blot hybridization was used to determine the number of inserted AtNPR1 copies in the genomes of the selected transgenic lines. All transgenic lines demonstrated AtNPR1 integration profiles whereas none was detected from the control plant (Fig 6). The transgenic line, 2, had one gene copy integrated into the genome. Transgenic lines 2, 4, 9A and 11A are ‘Hamlin’ while the line 18 is a ‘Valencia’ sweet orange. Transgenic plant lines No. 4, 9A and 18 had 2 copies while based on the intensity of the band we predicted that 11A line had 2 to 3 copies. These results were confirmed by q-PCR (Table 2). No amplification was detected from a non-transformed control plant (data not shown).

Fig 6. Southern hybridization analysis of total DNA from leaf tissue of five AtNPR1 transformed sweet orange lines (2, 4, 9A, 11A, 18) and a non-transgenic control plant.

Lines denoted with a number are constitutively expressing lines while lines with the suffix ‘A’ are phloem specific lines.

Table 2. Transgene copy number determination using quantitative real-time PCR by comparison of transgenic lines with external plasmid controls.

| Transgenic Line | Cultivar | Mean Cp A | STD Cp B | Mean Conc. C , D |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NPR1-2 | Hamlin | 25.550 | 0.115 | 1.101 |

| NPR1-4 | Hamlin | 25.160 | 1.378 | 1.605 |

| NPR1-9A | Hamlin | 25.064 | 0.639 | 1.738 |

| NPR1-11A | Hamlin | 24.412 | 0.867 | 2.643 |

| NPR1-18 | Valencia | 24.738 | 0.184 | 2.190 |

| Plasmid-1C E | - | 25.727 | 0.132 | 0.818 |

| Plasmid-2C | - | 24.746 | 0.079 | 2.180 |

| Plasmid-3C | - | 24.022 | 0.149 | 3.185 |

| Plasmid-4C | - | 23.567 | 0.115 | 3.816 |

| Plasmid-5C | - | 23.107 | 0.232 | 4.753 |

A Average values of crossing point from three sample replicates.

B Standard deviations.

C Average values of extrapolated concentration relative to a single transgene copy.

D Copy number.

E Plasmid DNA used for copy number calculations

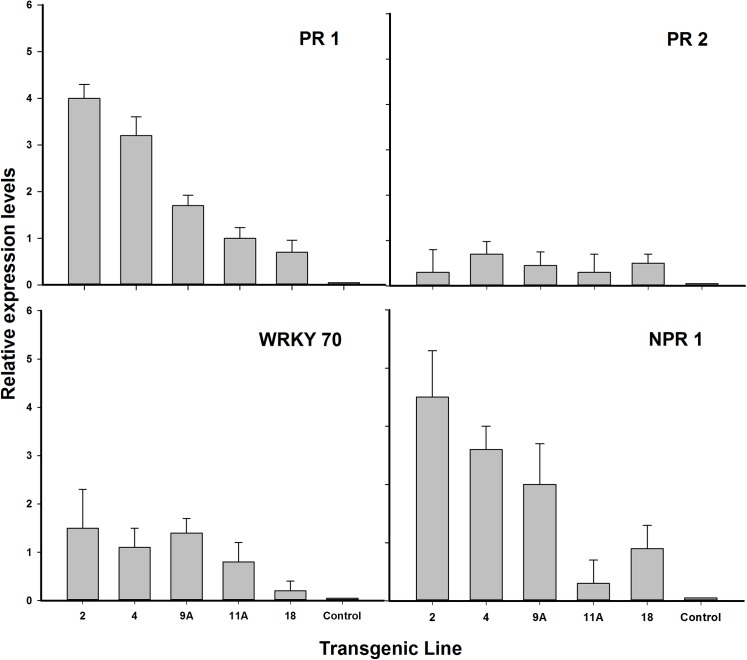

PR gene expression

The selected transgenic lines that were analyzed for copy number by Southern blot hybridization were also evaluated for PR gene expression using qRT-PCR. The pathogenesis-related PR1 gene is induced by NPR1 [31] and significant variation in PR1 gene expression was observed in these transgenic lines (Fig 7). All tested lines had enhanced PR1 gene expression. Transgenic line 2 exhibited a fourfold level in PR1 gene expression compared to the control. Lower expression levels were observed in the other lines. Expression levels of the PR2 gene, a SAR marker gene in citrus were also higher in all transgenic lines evaluated. However gene expression was less than 1 fold higher in all lines analyzed and there was no statistical significance between the evaluated transgenic lines. WRKY70 is a direct target for NPR1 and plays a role as a positive regulator of SA-mediated gene expression and resistance [32]. WRKY70 expression was not observed to be significantly different in any NPR1 overexpressing transgenic line except in line 18. The AtNPR1 expression levels in the transgenic lines were many fold higher than that observed in the non-transformed control plant, except for transgenic line 11A (Figs 5 and 7).

Fig 7. Quantification of gene activity using qPCR.

Sequence of primers used in the qPCR process is detailed in Table 1. Three independent clones were tested from each transgenic line. Total RNA from a non-transgenic plant was also included to verify the accuracy of the amplification process. Selected data from Fig 4 (AtNPR1) is included here for comparison.

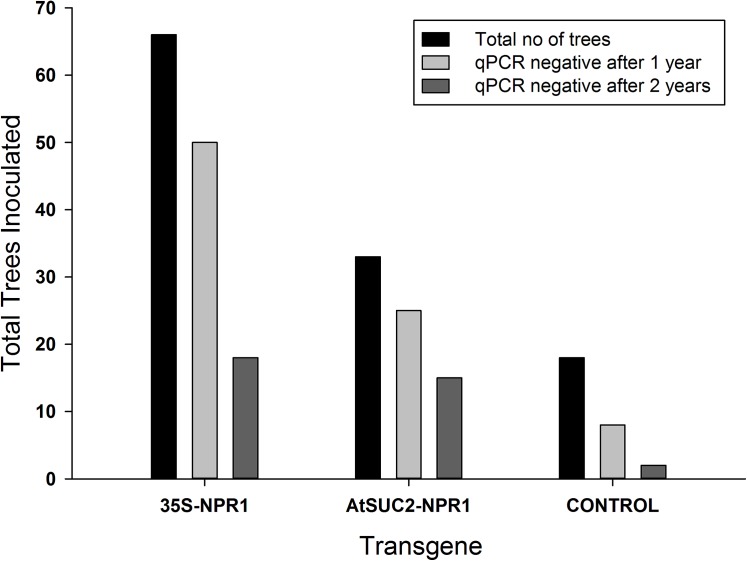

Susceptibility of transformed lines to Huanglongbing

Huanglongbing is caused by the phloem-limited, fastidious α-proteobacteria CLas spp. A majority of the trees tested positive for the bacterium in the second year of evaluation. Approximately 45% of the trees expressing AtNPR1 under the control of the phloem specific promoter were HLB negative while 27% of the trees expressing AtNPR1 under the control of the constitutive 35S promoter remained HLB negative (Fig 8). We did not detect the bacterium in transgenic lines 2, 4 and 9A for the duration of this study. Transgenic line 11A tested positive within 6 month and the severely infected trees were discarded after 18 months of infection (Table 3). Control trees tested positive for the presence of the CLas within 6 months after infection and remained positive for the entire duration of the study. In the second study, trees were planted in a high disease pressure field site. The results from that study are presented in Table 4. Transgenic line 2 remained CLas free for the duration of the study except for the 24 month sampling period when it tested positive. Line 4 tested positive at the 30 month sampling period while line 9A tested positive at 30 months but was CLas free at 36 months. Both of these lines did not decline in health and showed continued growth with periodic flushes. Line 11A tested positive after 18 months in the field and remained CLas + for the duration of the test period. The tolerant lines 2 and 9A also did not demonstrate any visual symptoms for the duration of the study while line 4 developed symptoms, tested positive for CLas but continued growth at a similar rate to the lines 2 and 9A. Transgenic line 18 was the most susceptible line and tested positive for CLas within 6 months after planting. Trees from this line began dying after 30 months in the field and were all dead within 36 months of planting in the field. Similar results were observed in the non-transgenic control trees (Fig 3).

Fig 8. Survival of transgenic plants and control after 1 and 2 years in a no-choice greenhouse evaluation study and exposed to free flying potentially CLas containing psyllids.

Table 3. Quantification of CLas bacterial titers following qPCR from leaf petiole and midribs of the transgenic plants and controls grown under greenhouse conditions and exposed to free flying, potentially CLas positive psyllids.

The mean threshold cycle values (Ct) at specified time intervals are demonstrated.

| Transgenic line #2 | Transgenic line #4 | Transgenic line #9A | Transgenic line #11A | Transgenic line #18 | Control | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 months | - | - | - | 29.29± 2.3 | NT | 23.48±1 |

| 12 months | - | - | - | 23.63±1.4 | NT | 22.04±2.2 |

| 18 months | - | - | - | 21.19±3.1 | NT | 20.78±4.5 |

| 24 months | - | - | - | * | NT | * |

*; dead trees, NT; not tested, Standard errors were calculated from three replicates.

Table 4. Quantification of CLas bacterial titers following qPCR from leaf petiole and midribs of the transgenic plants and controls grown under field conditions in a high disease pressure test site.

The mean threshold cycle values (Ct) at specified time intervals are demonstrated.

| Transgenic line #2 | Transgenic line #4 | Transgenic line #9A | Transgenic line #11A | Transgenic line #18 | Control | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 months | - | - | - | - | 37.42±3.1 | 38.39±3.3 |

| 12 months | - | - | - | - | 30.13±2.5 | 26.20±1.8 |

| 18 months | - | - | - | 33.81±4.1 | 23.81±4.1 | 27.69±1.5 |

| 24 months | 36.00 a | - | - | 27.72±2.3 | 29.02±1.6 | 22.87±1.6 |

| 30 months | - | 33.02±2.4 | 38.98 a | 24.45±2.2 | 21.52±3.1 | 23.14± 2.3 |

| 36 Months | - | 29.69±5.1 | - | 26.16±4.6 | * | * |

*; dead trees

a; only one replicate was PCR positive. Standard errors were calculated from three replicates.

Discussion

HLB, a phloem restricted bacterial disease of citrus has been present in the United States since 2005 [33]. This disease has resulted in a severe decline in fruit production in Florida, where it has become endemic [34]. Florida produces sweet oranges, predominantly for juice production and all commercial cultivars are susceptible to HLB [35]. Development of new cultivars through conventional hybridization is very difficult due to the high level of nuclear embryony in these cultivars. All major commercial sweet orange cultivars have arisen through the development of mutations and have been subsequently selected over hundreds of years [36]. In such cases, genetic improvement of existing cultivars without otherwise changing its characteristics through the incorporation of an additional advantageous trait remains the fastest method of improvement. Genetic engineering of sweet oranges is a viable alternative to conventional breeding as it is a relatively rapid process and it allows for the insertion of a single trait without the modifying existing traits. In this study, ‘Hamlin’ and ‘Valencia’ sweet oranges were transformed with the AtNPR1 transgene via Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation to produce transgenic plants tolerant to HLB.

NPR1 is a key regulator of gene expression following infection [37] and controls the onset of the immune response known as SAR [38]. AtNPR1 has been directly implicated for fungal disease resistance in wheat [39], cotton [40], broad spectrum disease resistance in strawberry [41], tomato [42], carrot [43] and bacterial disease resistance in citrus [11]. In addition, AtNPR1 homologs have been identified in many economically important plants such as citrus [44], gladiolus [45], grapevine [46], rice [47], phalaenopsis orchid [48] and sugarbeet [49] among others. Development of HLB resistant citrus by exploiting the plants own immune system is a potentially attractive approach to develop a genetically modified consumer-acceptable plant. This strategy utilizes a transgene whose homolog is available in many of our food crops, including citrus.

Regenerated trees exhibited normal phenotypes and did not demonstrate the abnormalities that were observed in strawberry plants constitutively expressing AtNPR1 [41] or the rice AtNPR1 homolog (NH1) in rice [47]. Homology dependent gene silencing can be an issue when endogenous genes are overexpressed in the same system [50, 51], which led us to overexpress the AtNPR1 in these citrus plants instead of the citrus homolog. Our results indicate overexpression of the AtNPR1 gene can induce resistance to HLB with a reduced disease severity phenotype in many lines. Resistance could not be directly co-related to AtNPR1 gene expression levels as several transgenic lines with good AtNPR1 expression levels were susceptible to HLB. This could be due to differential insertion of the transgene cassette in the individual lines. AtNPR1 produced either constitutively or in the phloem was observed to be sufficient in combatting HLB. Since NPR1 regulates the signal transduction pathway that results in SAR [18], gene expression in the phloem cells was sufficient to induce the PR genes resulting in disease resistance. Molecular analyses revealed the presence of the coding sequence of the introduced AtNPR1 and the expression of the gene in transgenic sweet orange plants. Analyzed lines had less than 3 copies of the transgene stably incorporated into the genome. We had previously observed that increase in copy number negatively affected the gene expression in citrus [52] and current results support that observation. Three genes involved in the plant defense signaling pathways, PR1 [37, 53], PR2 [11, 54] and WRKY70 [55, 56] were evaluated in this study based on their ability to be differentially regulated by AtNPR1. AtNPR1 induces PR1 gene expression [31] and the single copy insert (transgenic line 2) had both the highest NPR1 expression and PR1 expression. In fact, levels of PR1 gene expression could be directly co-related to the transgene mediated resistance to HLB. PR2, which has been observed to be directly responsible for the SAR process [11, 57] was also overexpressed in all the transgenic lines, though not at the levels observed for PR1 expression. The WRKY70 transcription factor influences the defense pathways [58] and specifically the salicylate-mediated signaling pathways in plant defense [56]. Apart from line 18, all the other lines behaved similarly demonstrating the activation of the SAR pathways. The observed results are contradictory to that observed before in citrus [11] where constitutive defense responses were not observed following overexpression of AtNPR1. A few of the transformed lines did not exhibit enhanced gene expression indicating post-transcriptional gene silencing or inefficient nicking of T-DNA borders and co-transfer of non-T-DNA sequences into the citrus genome[59,60]. The basic mechanism behind SAR is generally conserved across species, but based on our results, it becomes apparent that there is a differential gene expression pattern following SAR between citrus and other crop plants.

Conclusions

In addition to inducing resistance to HLB, the SAR response observed could potentially protect our trees from other important citrus fungal and bacterial diseases such as citrus canker and black spot. Both constitutive expression and phloem expression of AtNPR1 would lead to a genetically modified commercial scion and in addition, phloem expression could lead to the development of a transposable transgene effect that could possibly induce HLB resistance in non-transgenic citrus. Phloem specific expression of the transgene and the observed resistance could allow the movement of the SAR response across the graft union. This transfer may induce a SAR response that could potentially protect the non-transgenic scion from HLB. In this model any existing non-transgenic scion could be budded onto a transgenic rootstock in order to impart HLB resistance. A non-transgenic scion grafted onto a transgenic rootstock could potentially be acceptable to the consumer than transgenic citrus scions. In addition, this transgene can also serve as a component for the development of an all plant T-DNA derived consumer friendly GM tree.

Acknowledgments

MD and JG would like to thank Sadanand Dhekney for helpful discussions and providing valuable comments. Ed Stover is thanked for his support in the field evaluation of our transgenic plants.

Data Availability

All relevant data can be found within the paper.

Funding Statement

Citrus Research & Development Foundation (www.citrusrdf.org/). Funding Statement: The Citrus Research & Development Foundation provided support in the form of salaries for author MD, but did not have any additional role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. Southern Gardens Citrus did not provide any financial assistance but assisted in evaluating the authors' transgenic lines in a no-choice greenhouse evaluation study containing free flying potentially CLas containing psyllids. In addition, they provided assistance in qPCR analyses of transgenic leaf samples.

References

- 1. Duan Y, Zhou L, Hall DG, Li W, Doddapaneni H, Lin H, et al. Complete genome sequence of citrus huanglongbing bacterium, 'Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus' obtained through metagenomics. Molecular plant-microbe interactions: MPMI. 2009;22(8):1011–20. Epub 2009/07/11. 10.1094/mpmi-22-8-1011 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Alves GR, Diniz AJ, Parra JR. Biology of the Huanglongbing vector Diaphorina citri (Hemiptera: Liviidae) on different host plants. Journal of economic entomology. 2014;107(2):691–6. Epub 2014/04/30. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Manjunath KL, Halbert SE, Ramadugu C, Webb S, Lee RF. Detection of ‘Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus’ in Diaphorina citri and Its Importance in the Management of Citrus Huanglongbing in Florida. Phytopathology. 2008;98(4):387–96. 10.1094/PHYTO-98-4-0387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wang N, Trivedi P. Citrus Huanglongbing: A Newly Relevant Disease Presents Unprecedented Challenges. Phytopathology. 2013;103(7):652–65. 10.1094/PHYTO-12-12-0331-RVW [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Massenti R, Lo Bianco R, Sandhu AK, Liwei G, Sims C. Huanglongbing modifies quality components and flavonoid content of 'Valencia' oranges. Journal of the science of food and agriculture. 2014. Epub 2014/12/30. 10.1002/jsfa.7061 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Qureshi JA, Kostyk BC, Stansly PA. Insecticidal Suppression of Asian Citrus Psyllid Diaphorina citri (Hemiptera: Liviidae) Vector of Huanglongbing Pathogens. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(12):e112331 10.1371/journal.pone.0112331 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Belasque Júnior J, Yamamoto PT, Miranda MPd, Bassanezi RB, Ayres AJ, Bové JM. Huanglongbing control in São Paulo State, Brazil. Citrus Research and Technology. 2010;31(1):53–64. 10.5935/2236-3122.20100005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Westbrook CJ, Hall DG, Stover E, Duan YP, Lee RF. Colonization of Citrus and Citrus-related germplasm by Diaphorina citri (Hemiptera: Psyllidae). HortScience. 2011;46(7):997–1005. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Furr J, Cooper W, Reece P. An investigation of flower formation in adult and juvenile citrus trees. American Journal of Botany. 1947:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gmitter J, F. G., Grosser JW, Castle WS, Moore GA. A comprehensive Citrus genetic improvement program In: Khan IA, editor. Citrus Genetics, Breeding and Biotechnology. Oxfordshire, UK: CAB International; 2007. p. 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhang X, Francis MI, Dawson WO, Graham JH, Orbović V, Triplett EW, et al. Over-expression of the Arabidopsis NPR1 gene in citrus increases resistance to citrus canker. Eur J Plant Pathol. 2010;128(1):91–100. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kuć J. Induced Immunity to Plant Disease. BioScience. 1982;32(11):854–60. 10.2307/1309008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ward ER, Uknes SJ, Williams SC, Dincher SS, Wiederhold DL, Alexander DC, et al. Coordinate Gene Activity in Response to Agents That Induce Systemic Acquired Resistance. The Plant Cell. 1991;3(10):1085–94. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Malamy J, Carr JP, Klessig DF, Raskin I. Salicylic Acid: a likely endogenous signal in the resistance response of tobacco to viral infection. Science (New York, NY). 1990;250(4983):1002–4. Epub 1990/11/16. 10.1126/science.250.4983.1002 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Durrant WE, Dong X. Systemic acquired resistance. Annual review of phytopathology. 2004;42:185–209. Epub 2004/07/31. 10.1146/annurev.phyto.42.040803.140421 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Forouhar F, Yang Y, Kumar D, Chen Y, Fridman E, Park SW, et al. Structural and biochemical studies identify tobacco SABP2 as a methyl salicylate esterase and implicate it in plant innate immunity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102(5):1773–8. Epub 2005/01/26. 10.1073/pnas.0409227102 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPmc547883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nawrath C, Metraux JP. Salicylic acid induction-deficient mutants of Arabidopsis express PR-2 and PR-5 and accumulate high levels of camalexin after pathogen inoculation. Plant Cell. 1999;11(8):1393–404. Epub 1999/08/17. ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPmc144293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kinkema M, Fan W, Dong X. Nuclear Localization of NPR1 Is Required for Activation of PR Gene Expression. The Plant Cell. 2000;12(12):2339–50. 10.1105/tpc.12.12.2339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Clarke JD, Liu Y, Klessig DF, Dong X. Uncoupling PR gene expression from NPR1 and bacterial resistance: characterization of the dominant Arabidopsis cpr6-1 mutant. Plant Cell. 1998;10(4):557–69. Epub 1998/06/13. ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPmc144011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cao H, Li X, Dong X. Generation of broad-spectrum disease resistance by overexpression of an essential regulatory gene in systemic acquired resistance. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95(11):6531–6. Epub 1998/05/30. ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPmc34547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Li Z, Jayasankar S, Gray DJ. Expression of a bifunctional green fluorescent protein (GFP) fusion marker under the control of three constitutive promoters and enhanced derivatives in transgenic grape (Vitis vinifera). Plant science: an international journal of experimental plant biology. 2001;160(5):877–87. Epub 2001/04/12. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hood E, Gelvin S, Melchers L, Hoekema A. New Agrobacterium helper plasmids for gene transfer to plants. Transgenic Research. 1993;2(4):208–18. 10.1007/BF01977351 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Burow M, Chlan C, Sen P, Lisca A, Murai N. High-frequency generation of transgenic tobacco plants after modified leaf disk cocultivation withAgrobacterium tumefaciens. Plant Mol Biol Rep. 1990;8(2):124–39. 10.1007/BF02669766 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dutt M, Grosser JW. Evaluation of parameters affecting Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of citrus. Plant Cell Tiss Organ Cult. 2009;98(3):331–40. 10.1007/s11240-009-9567-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dutt M, Grosser J. An embryogenic suspension cell culture system for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of citrus. Plant cell reports. 2010;29(11):1251–60. 10.1007/s00299-010-0910-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Li W, Hartung JS, Levy L. Quantitative real-time PCR for detection and identification of Candidatus Liberibacter species associated with citrus huanglongbing. Journal of microbiological methods. 2006;66(1):104–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dutt M, Li Z, Dhekney S, Gray D. A co-transformation system to produce transgenic grapevines free of marker genes. Plant Science. 2008;175(3):423–30. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dutt M, Ananthakrishnan G, Jaromin M, Brlansky R, Grosser J. Evaluation of four phloem-specific promoters in vegetative tissues of transgenic citrus plants. Tree physiology. 2012;32(1):83–93. 10.1093/treephys/tpr130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2ΔΔCT Method. methods. 2001;25(4):402–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Song P, Cai C, Skokut M, Kosegi B, Petolino J. Quantitative real-time PCR as a screening tool for estimating transgene copy number in WHISKERS™-derived transgenic maize. Plant Cell Reports. 2002;20(10):948–54. 10.1007/s00299-001-0432-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhou J-M, Trifa Y, Silva H, Pontier D, Lam E, Shah J, et al. NPR1 Differentially Interacts with Members of the TGA/OBF Family of Transcription Factors That Bind an Element of the PR-1 Gene Required for Induction by Salicylic Acid. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions. 2000;13(2):191–202. 10.1094/MPMI.2000.13.2.191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wang D, Amornsiripanitch N, Dong X. A genomic approach to identify regulatory nodes in the transcriptional network of systemic acquired resistance in plants. PLoS pathogens. 2006;2(11):e123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bové J. Huanglongbing or yellow shoot, a disease of Gondwanan origin: Will it destroy citrus worldwide? Phytoparasitica. 2014;42(5):579–83. 10.1007/s12600-014-0415-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Morris A, Muraro RP, Castle WS. Optimal grove replanting to mitigate endemic HLB. Citrus Ind. 2011;92(4):12–6. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kim JS, Sagaram US, Burns JK, Li JL, Wang N. Response of sweet orange (Citrus sinensis) to 'Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus' infection: microscopy and microarray analyses. Phytopathology. 2009;99(1):50–7. Epub 2008/12/06. 10.1094/phyto-99-1-0050 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fang D, Roose M. Identification of closely related citrus cultivars with inter-simple sequence repeat markers. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 1997;95(3):408–17. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zhang Y, Fan W, Kinkema M, Li X, Dong X. Interaction of NPR1 with basic leucine zipper protein transcription factors that bind sequences required for salicylic acid induction of the PR-1 gene. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1999;96(11):6523–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cao H, Glazebrook J, Clarke JD, Volko S, Dong X. The Arabidopsis NPR1 gene that controls systemic acquired resistance encodes a novel protein containing ankyrin repeats. Cell. 1997;88(1):57–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Makandar R, Essig JS, Schapaugh MA, Trick HN, Shah J. Genetically Engineered Resistance to Fusarium Head Blight in Wheat by Expression of Arabidopsis NPR1. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions. 2006;19(2):123–9. 10.1094/MPMI-19-0123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kumar V, Joshi S, Bell A, Rathore K. Enhanced resistance against Thielaviopsis basicola in transgenic cotton plants expressing Arabidopsis NPR1 gene. Transgenic Research. 2013;22(2):359–68. 10.1007/s11248-012-9652-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Silva KJP, Brunings A, Peres NA, Mou Z, Folta KM. The Arabidopsis NPR1 gene confers broad-spectrum disease resistance in strawberry. Transgenic research. 2015:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lin WC, Lu CF, Wu JW, Cheng ML, Lin YM, Yang NS, et al. Transgenic tomato plants expressing the Arabidopsis NPR1 gene display enhanced resistance to a spectrum of fungal and bacterial diseases. Transgenic Research. 2004;13(6):567–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wally O, Jayaraj J, Punja ZK. Broad-spectrum disease resistance to necrotrophic and biotrophic pathogens in transgenic carrots (Daucus carota L.) expressing an Arabidopsis NPR1 gene. Planta. 2009;231(1):131–41. 10.1007/s00425-009-1031-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chen X, Barnaby JY, Sreedharan A, Huang X, Orbović V, Grosser JW, et al. Over-expression of the citrus gene CtNH1 confers resistance to bacterial canker disease. Physiological and Molecular Plant Pathology. 2013;84:115–22. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zhong X, Xi L, Lian Q, Luo X, Wu Z, Seng S, et al. The NPR1 homolog GhNPR1 plays an important role in the defense response of Gladiolus hybridus. Plant Cell Rep. 2015;34(6):1063–74. Epub 2015/02/25. 10.1007/s00299-015-1765-1 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Le Henanff G, Heitz T, Mestre P, Mutterer J, Walter B, Chong J. Characterization of Vitis vinifera NPR1 homologs involved in the regulation of pathogenesis-related gene expression. BMC Plant Biology. 2009;9(1):54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chern M, Fitzgerald HA, Canlas PE, Navarre DA, Ronald PC. Overexpression of a rice NPR1 homolog leads to constitutive activation of defense response and hypersensitivity to light. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2005;18(6):511–20. Epub 2005/07/01. 10.1094/mpmi-18-0511 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Chen JC, Lu HC, Chen CE, Hsu HF, Chen HH, Yeh HH. The NPR1 ortholog PhaNPR1 is required for the induction of PhaPR1 in Phalaenopsis aphrodite. Botanical Studies. 2013;54(1):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kuykendall LD, Murphy TS, Shao J, McGrath JM. Nucleotide sequence analyses of a sugarbeet genomic NPR1-class disease resistance gene. Journal of Sugar Beet Research. 2007;44(1/2):35. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Meyer P, Saedler H. Homology-dependent gene silencing in plants. Annual review of plant biology. 1996;47(1):23–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kooter JM, Matzke MA, Meyer P. Listening to the silent genes: transgene silencing, gene regulation and pathogen control. Trends in plant science. 1999;4(9):340–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Dutt M, Vasconcellos M, Grosser J. Effects of antioxidants on Agrobacterium-mediated transformation and accelerated production of transgenic plants of Mexican lime (Citrus aurantifolia Swingle). Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture (PCTOC). 2011;107(1):79–89. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Mou Z, Fan W, Dong X. Inducers of plant systemic acquired resistance regulate NPR1 function through redox changes. Cell. 2003;113(7):935–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Maleck K, Dietrich RA. Defense on multiple fronts: how do plants cope with diverse enemies? Trends in plant science. 1999;4(6):215–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Yu D, Chen C, Chen Z. Evidence for an Important Role of WRKY DNA Binding Proteins in the Regulation of NPR1 Gene Expression. The Plant Cell. 2001;13(7):1527–40. 10.1105/tpc.010115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Li J, Brader G, Palva ET. The WRKY70 transcription factor: a node of convergence for jasmonate-mediated and salicylate-mediated signals in plant defense. The Plant Cell Online. 2004;16(2):319–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Llorens E, Vicedo B, López MM, Lapeña L, Graham JH, García-Agustín P. Induced resistance in sweet orange against Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri by hexanoic acid. Crop Protection. 2015;74:77–84. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ülker B, Mukhtar MS, Somssich IE. The WRKY70 transcription factor of Arabidopsis influences both the plant senescence and defense signaling pathways. Planta. 2007;226(1):125–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Matzke AJ, Matzke MA. Position effects and epigenetic silencing of plant transgenes. Current opinion in plant biology. 1998;1(2):142–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kooter JM, Matzke MA, Meyer P. Listening to the silent genes: transgene silencing, gene regulation and pathogen control. Trends in plant science. 1999;4(9):340–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data can be found within the paper.