Abstract

Objective To examine differences between families of youth with spina bifida (SB) and families of typically developing (TD) youth on family-, parent-, and youth-level variables across preadolescence and adolescence. Methods Participants were 68 families of youth with SB and 68 families of TD youth. Ratings of observed family interactions were collected every 2 years at 5 time points (Time 1: ages 8–9 years; Time 5: ages 16–17 years). Results For families of youth with SB: families displayed less cohesion and more maternal psychological control during preadolescence (ages 8–9 years); parents presented as more united and displayed less dyadic conflict, and youth displayed less conflict behavior during the transition to adolescence (ages 10–13 years); mothers displayed more behavioral control during middle (ages 14–15 years) and late (ages 16–17 years) adolescence; youth displayed less engagement and more dependent behavior at every time point. Conclusions Findings highlight areas of resilience and disruption in families of youth with SB across adolescence.

Keywords: adolescence, family, observational data, parenting, preadolescence, resilience, spina bifida.

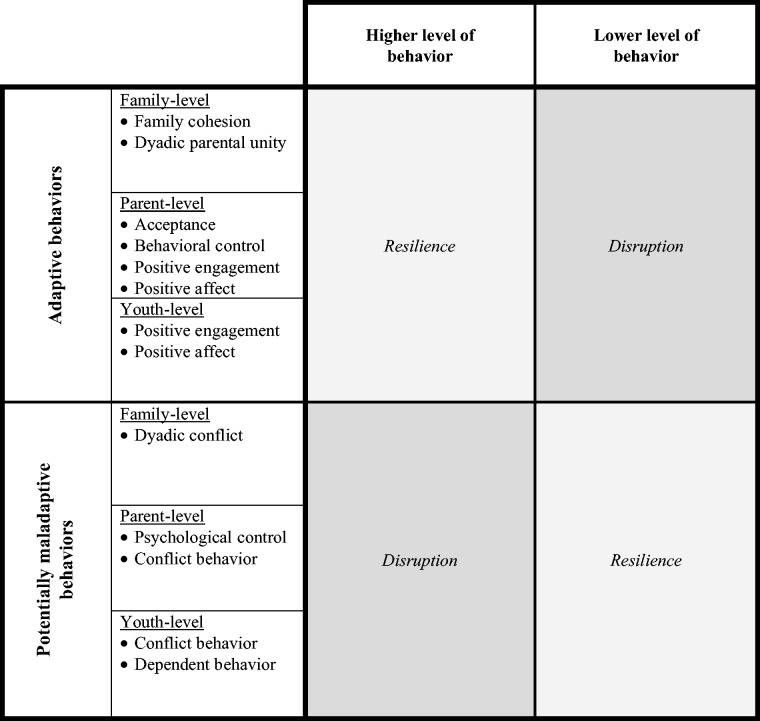

Pediatric chronic illness presents families with numerous challenges, and each family responds to these challenges differently. Despite the negative impact or disruption that the presence of a chronic illness may have on a child and his/her family, research has revealed that many families demonstrate significant resilience. In this context, resilience refers to the attainment of desirable social and emotional adjustment, despite adversity due to the presence of a chronic illness (Rutter, 1985), and can be expressed at the family, dyadic, and individual levels. Research on certain pediatric populations has supported a resilience–disruption model, in which families of children with chronic illness display both disruption and resilience as compared with families of healthy children (Costigan, Floyd, Harter, & McClintock, 1997; Holmbeck, Coakley, Hommeyer, Shapera, & Westhoven, 2002). These studies (e.g., Holmbeck, Coakley, et al., 2002) have defined “disruption” as occurring when families of youth with chronic illness display significantly more potentially maladaptive behaviors (e.g., more family conflict, parental psychological control, and child dependent behavior) or significantly less adaptive behaviors (e.g., less family cohesion, parental acceptance, and child positive engagement) than families of typically developing (TD) youth. These studies have defined “resilience” as occurring when affected families display significantly more adaptive behaviors (e.g., more parental acceptance), or fewer significant differences as compared to families of TD youth (e.g., families display similar levels of family conflict). Thus, resilience can occur in two ways, namely, when certain behaviors exceed or are not dissimilar from normative developmental functioning despite the added stressors associated with the presence of chronic illness.

Spina bifida (SB) is a congenital birth defect caused by incomplete closure of the neural tube during the early weeks of gestation. In addition to serious health complications, such as paralyzed lower extremities, bladder and bowel incontinence, and seizures, many individuals with SB develop hydrocephalus, which is commonly treated with a shunt at birth. The complex medical presentation of SB can place numerous physical, psychological, and social demands on the children, parents, and family units of individuals with SB (Holmbeck et al., 2003). Despite the potential demands of SB, families of children with SB have been observed to display family-, parent-, and youth-level resilience at different stages of adolescence.

Areas of resilience and disruption that emerge in response to the presence of a chronic illness such as SB are best understood from a developmental perspective that recognizes the normative milestones of child and adolescent development. Adolescence is a transitional period of human development marked by significant changes in biological, cognitive, social, and emotional functioning (Susman & Rogel, 2004); the presence of a serious medical condition may alter the typical experience of these changes. Specifically, the entire adolescent period, considered here to range from preadolescence (ages 8–9 years) to late adolescence (ages 16–17 years), may be experienced differently for families of youth with SB.

Previous research on families of youth with SB during preadolescence (i.e., ages 8–9 years) has documented areas of resilience and disruption in terms of family, parent, and youth behaviors. For example, families of youth with SB have been observed to be less cohesive during the preadolescence stage, but to demonstrate similar levels of conflict compared with families of TD youth (Holmbeck, Coakley, et al., 2002). In addition, parents of preadolescents with SB have been observed to exhibit more psychological control (Holmbeck, Shapera, & Hommeyer, 2002) and overprotectiveness (Holmbeck, Johnson, et al., 2002). Parents who are caring for children with SB may be more controlling or overprotective due to their perception that their chronically ill child is vulnerable (Thomasgard, Shonkoff, Metz, & Edelbrock, 1995), the child’s lack of maturity, and/or because they are attempting to gain control of a complex and often unpredictable medical situation (Anderson & Coyne, 1993). Lastly, preadolescents with SB have been observed to be less involved during family discussions and display more passive and dependent behavior (Holmbeck, Coakley, et al., 2002). However, these youth also display less conflict behavior and display similar positive affect compared with TD preadolescents (Holmbeck, Coakley, et al., 2002; Holmbeck et al., 2003). Thus, during preadolescence, the presence of SB may disrupt some aspects of functioning, yet these families still appear to demonstrate considerable resilience in other adjustment domains.

However, it is unclear whether preadolescent patterns of resilience and disruption persist at different points during adolescence for families of youth with SB, including the transition to adolescence (i.e., ages 10–13 years), middle adolescence (i.e., ages 14–15 years), and late adolescence (i.e., ages 16–17 years; Steinberg, 2005). As TD youth transition through the stages of adolescence, they are likely to experience increases in independence and autonomy, leading to role changes in the family (Steinberg, 2005). However, the management of a chronic illness, such as SB, may be at odds with these typical developmental changes of adolescence.

Previous longitudinal research examining trajectories in family, parent, and youth behaviors has found that youth with SB negotiate the adolescent developmental period differently as compared with TD youth. Specifically, these past studies, that are based on the same data set used here, have examined changes in growth over time from ages 8 to 15 years and have found, for example, that as youth with SB progress through adolescence, their families are less likely to display developmentally normative decreases in family cohesion and increases in parent–child conflict (Jandasek, Holmbeck, DeLucia, Zebracki, & Friedman, 2009). In addition, when examining engagement in the family, the developmental trajectory of youth with SB converges with that of TD youth, in that youth with SB initially display less engagement but “catch-up” overtime (Holmbeck et al., 2010). Further, although dependent behavior declines across adolescence for youth with SB, it also declines for TD youth at a similar rate (Friedman, Holmbeck, DeLucia, Jandasek, & Zebracki, 2009). Lastly, while youth with SB show increases in independent behavior and emotional autonomy (Friedman et al., 2009), their behavioral autonomy and decision-making autonomy appear to lag behind that of TD youth by about 2 years (Devine, Wasserman, Gershenson, Holmbeck, & Essner, 2011).

There is reason to believe that differences may emerge at different points during adolescence, given that parenting adolescents with SB may be complicated by factors such as adherence to medical care tasks (e.g., intermittent catheterization, bowel programs). Indeed, families of youth with SB experience the unique stressor of transferring these medical care responsibilities from parent(s) to child during the adolescent period (Psihogios & Holmbeck, 2013). As youth with SB enter middle and late adolescence, parents may transfer more medical responsibility to their child, which may result in increased familial conflict and decreased medical adherence (Stepansky, Roache, Holmbeck, & Shultz, 2009). This process is complex, however, as increased parental behavioral control may improve adherence to medical regimens, but simultaneously negatively impact levels of adolescent behavioral autonomy.

In summary, previous cross-sectional work has revealed specific areas of disruption and resilience for families of youth with SB during preadolescence. In addition, longitudinal studies have indicated that differences in growth across several of these domains may occur during adolescence; such analyses have been conducted by comparing statistical slopes of change between youth with SB and TD peers. However, group comparisons on trajectory slopes address different research questions than an examination of mean group differences at different time points. In other words, a more comprehensive yet nuanced understanding is needed on how families of youth with SB differ from TD families in terms of family-, parent-, and youth-level functioning at the four developmental points of adolescence described above. By examining differences at specific time points, we may be able to identify the exact ages at which these areas of resilience and disruption emerge, allowing for direct investigation into the causes of these developmentally relevant differences as well as more targeted intervention efforts for specific age groups.

Thus, the purpose of this study was to identify and compare specific areas of resilience and disruption during preadolescence (Time 1, ages 8–9 years), the transition to adolescence (Times 2 and 3, ages 10–11 and 12–13 years), middle adolescence (Time 4, ages 14–15 years), and late adolescence (Time 5, ages 16–17 years) using observed family interaction data from both families of youth with SB and families of TD youth.1 Observed family interactions were examined in terms of family- (family cohesion, dyadic parental unity, dyadic conflict), parent- (acceptance, behavioral control, psychological control, positive engagement, positive affect, conflict behavior), and youth-level variables (positive engagement, positive affect, conflict behavior, dependent behavior). Consistent with previous research, disruption was defined as the occurrence of significantly more maladaptive behaviors (i.e., dyadic conflict, parental psychological control, parental and youth conflict behavior, youth dependent behavior) or significantly less adaptive behaviors (i.e., family cohesion, dyadic parental unity, parental acceptance and behavioral control, parental and youth positive engagement and positive affect). Resilience was defined as the occurrence of equivalent or higher levels of adaptive behaviors or the absence of significant differences in maladaptive behaviors (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study constructs as areas of resilience or disruption, depending on the degree of presence of the behavior.

Broadly, it was hypothesized that areas of both resilience and disruption would emerge at different points across adolescence. More specifically, it was expected that, during preadolescence (i.e., ages 8–9 years), families of youth with SB would demonstrate significant disruption in areas of family cohesion, dyadic parental unity, parenting behaviors, and youth behaviors. However, it was expected that families of youth with SB would be less impacted by difficulties associated with the transition to adolescence (i.e., ages 10–13 years) as would be expected in families of TD youth and, thus, would demonstrate significant resilience in areas of dyadic parental unity, dyadic conflict, and parenting behavior. Lastly, during middle (i.e., ages 14–15 years) and late (i.e., ages 16–17 years) adolescence, as youth with SB begin “catching up” in terms of autonomy, and as the sharing of medical responsibilities increases, it was expected that families of youth with SB would demonstrate areas of disruption in terms of parenting and youth behaviors.

Methods

Participants

Participants were part of a larger, longitudinal investigation examining family functioning and psychosocial functioning among youth with SB and TD youth (see Holmbeck et al., 2003). Families of youth with SB were recruited from three Midwest hospitals and a statewide SB association. This study included a matched comparison sample of TD children and their families recruited from schools where participating children with SB were enrolled. TD children and youth with SB were matched on 10 demographic variables, including age, gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic status (SES), and parental marital status and age. Groups did not differ significantly on any of these matching variables at Time 1 (p values > .05; see Holmbeck et al., 2003 for details on the matching process). The present study examined five waves of data that were collected every 2 years (ages 8–9 years at Time 1, 10–11 years at Time 2, 12–13 years at Time 3, 14–15 years at Time 4, 16–17 years at Time 5). At Time 1, participants included 68 families with a child with SB and 68 families with a TD child. At Time 2, 67 (99% of original sample) SB and 66 (97% of original sample) TD families participated; at Time 3, 64 (94%) SB and 66 (97%) TD families participated; at Time 4, 60 (88%) SB and 65 (96%) TD families participated; and at Time 5, 52 (76%) SB and 61 (90%) TD families participated. Families of youth with SB had higher attrition rates across the five time points, χ2(1) = 4.24, p < .05. See Table I for descriptive information for the participants at Time 1.

Table I.

Demographics at Time 1: Comparisons Across Samples

| Demographic characteristic | Spina bifida M (SD) or N (%) | Typically developing M (SD) or N (%) | Statistical test |

|---|---|---|---|

| Child age | 8.34 (.48) | 8.49 (.50) | t (134) = –1.75 |

| Maternal age | 37.74 (5.19) | 37.74 (4.84) | t (134) = .00 |

| Paternal age | 41.02 (5.45) | 40.63 (6.50) | t (105) = .33 |

| Child gender: male | 37 (54.41%) | 37 (54.41%) | χ2(1) = .00 |

| Child birth order | 2.12 (1.38) | 2.06 (1.29) | t (129) = .27 |

| Child ethnicity | |||

| White | 56 (82.35%) | 62 (91.18%) | χ2(1) = 2.30 |

| Other | 12 (17.65%) | 6 (8.82%) | |

| Marital status | |||

| Two-parent intact | 55 (80.88%) | 47 (69.12%) | χ2(1) = 2.51 |

| Not intact | 13 (19.2%) | 21 (30.88%) | |

| Family SES | 43.12 (10.57) | 46.46 (10.89) | t (131) = −1.80 |

Note. n = 68 for both samples. SES = socioeconomic status measured by Hollingshead Four Factor Index. All statistics were nonsignificant.

Information on several physical status variables for the SB group was collected from mother report on a questionnaire (i.e., method of ambulation, shunt status) and review of medical charts (i.e., type of SB, lesion level, number of shunt surgeries). The majority of participating youth had myelomeningocele (82% myelomeningocele, 12% lipomeningocele, 6% other), lumbar-level lesions (54% lumbar level, 32% sacral level, 13% thoracic), and required assistance for ambulation (63% used braces, 18% used a wheelchair, 19% unassisted). In addition, the majority of youth had a shunt (71%), and the average number of surgeries among those with shunts was 2.50 (SD = 2.91) at Time 1.

Procedure

This study was approved by university and hospital institutional review boards. Trained research assistants collected data during a 3-hr home visit at each time point. In addition to informed consent from parents, a release of information form to obtain data from medical records was collected during each visit. Children also provided written assent. During home visits, families participated in semistructured videotaped family interaction tasks. While both parents were encouraged to participate in the interaction tasks, sometimes only one parent was available; this was determined based on the individual circumstances of each family (e.g., some parents were not able to participate due to work schedule conflicts). Tasks were presented in a counterbalanced order and consisted of a warm-up task, an unfamiliar board game task, a structured family interaction task (Ferreira, 1963), and a conflict task (Smetana, Yau, Restrepo, & Braeges, 1991). The present study examined coded observational data obtained from all tasks except for the warm-up task (see Holmbeck et al., 2003 for a more detailed description of these tasks). Family members completed counterbalanced questionnaires separately. Families received monetary compensation for completion of each visit ($50 for Time 1 and $75 for Times 2–5).

Measures

Demographic Information

Parents completed a demographic questionnaire to report on youth age, gender, and race/ethnicity. Parents also reported on their education and employment, which were used to compute the Hollingshead Index of SES, with higher scores indicating higher SES (Hollingshead, 1975). For two-parent families in which both caregivers were employed, scores were averaged to calculate SES. For single-parent families or for two-parent households in which only one parent was employed, the employed individual’s information was used to calculate Time 1 SES.

Videotaped Family Interaction Tasks

Three family interaction tasks were coded using a global coding system developed by Johnson and Holmbeck (1995) that is based on a methodology devised by Smetana and colleagues (1991), and has been shown to have adequate reliability and validity (Kaugars et al., 2011).2 As is typical of global rating systems, coders viewed individual family tasks and then provided ratings on a variety of dimensions. Undergraduate and graduate research assistants coded videos. Coders were trained for roughly 8–10 hr until they had achieved 90% agreement with an expert graduate student coder (during training, agreement was assumed when two codes were within one Likert scale point of each other). All coders were blind to the specific hypotheses of this study; however, due to the nature of SB (e.g., wheelchair use due to physical disability), they were not necessarily blind to the group status of the youth participant. Two coders separately viewed each of the three interaction tasks and rated items on a 5-point Likert scale. The anchors for this Likert scale varied depending on the specific code, but generally it ranged from almost never/almost not at all to almost always/very much. The manual for this coding system includes behavioral descriptions for each point along the Likert scale. The coding system assesses several levels of family interactions, including systemic (i.e., the family as a whole), dyadic (i.e., mother–child, father–child, mother–father), as well as individual mother, father, and youth behaviors. For data analyses, item-level means for the two raters for each task were averaged across the three tasks to yield a single score for each coding item for each family.

Intraclass correlations (ICCs) that assessed interrater reliabilities (Suen & Ary, 1989) were computed across coders and tasks for all items at each time point for the SB sample and TD sample separately. To assess scale reliability at each time point, Cronbach’s αs were computed for scales with three or more items and Pearson correlation coefficients were computed for scales with two items. Specific interrater and scale reliability values are provided in Table II.

Table II.

Ranges and Means of Interrater Reliability and Scale Reliability for Study Variables for Times 1–5

| Variable | Interrater reliabilities ICCs (M) |

Scale reliabilities α or r (M) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spina bifida | Typically developing | Spina bifida | Typically developing | |

| Family behaviors | .48–.92 (M = .70) | .59–.96 (M = .69) | ||

| Family cohesion (αs) | 91–.92 (M = .92) | .89–.96 (M = .92) | ||

| Dyadic parental unity | N/A | N/A | ||

| Family conflict | N/A | N/A | ||

| Parenting behaviors | ||||

| Maternal | .54–.89 (M = .77) | .72–.87 (M = .81) | ||

| Acceptance (αs) | .75–.86 (M = .80) | .74–.85 (M = .79) | ||

| Behavioral control (rs) | .44–.64 (M = .54) | .56–.74 (M = .68) | ||

| Psychological control (αs) | .62–.76 (M = .70) | .71–.83 (M = .76) | ||

| Paternal | .71–.91 (M = .83) | .67–.86 (M = .80) | ||

| Acceptance (αs) | .75–.88 (M = .82) | .68–.80 (M = .76) | ||

| Behavioral control (rs) | .48–.72 (M = .72) | .60–.85 (M = .72) | ||

| Psychological control (αs) | .67–.76 (M = .72) | .58–.82 (M = .71) | ||

| General parent behaviors | ||||

| Maternal | .57–.91 (M = .81) | .75–.89 (M = .82) | ||

| Positive engagement (αs) | .87–.89 (M = .88) | .77–.87 (M = .84) | ||

| Positive affect (αs) | .75–.86 (M = .80) | .73–.85 (M = .78) | ||

| Conflict behavior (rs) | .42–.79 (M = .61) | .53–.79 (M = .67) | ||

| Paternal | .69–.93 (M = .84) | .53–.90 (M = .80) | ||

| Positive engagement (αs) | .86–.92 (M = .89) | .80–.90 (M = .86) | ||

| Positive affect (αs) | .76–.88 (M = .83) | .70–.76 (M = .74) | ||

| Conflict behavior (rs) | .39–.87 (M = .66) | .43–.75 (M = .66) | ||

| Youth behaviors | .72–.92 (M = .84) | .77–.92 (M = .85) | ||

| Positive engagement (αs) | .87–.90 (M = .88) | .87–.91 (M = .89) | ||

| Positive affect (αs) | .68–.81 (M = .73) | .75–.88 (M = .83) | ||

| Conflict behavior (rs) | .58–.87 (M = .73) | .74–.84 (M = .77) | ||

| Dependent behavior (rs) | .59–.81 (M = .74) | .51–.75 (M = .61) | ||

Note. To assess interrater reliabilities, intraclass correlations (ICCs) were computed across coders and tasks for all items at each time point. To assess scale reliability at each time point, Cronbach’s αs were computed for scales with three or more items and Pearson correlation coefficients were computed for scales with two items.

Family-Level Behaviors

Family systemic and dyadic behaviors included family cohesion, dyadic parental unity, and family conflict. Family cohesion was measured by averaging ratings across the following four codes: (1) impaired (reverse-coded; when reversed, this item assesses how well the family is able to respond to the task and how well they can communicate and discuss differences), (2) disengaged (reverse-coded), (3) open or warm, and (4) able to reach a resolution or agreement. Dyadic parental unity was measured using one code: the degree to which parents present as a united front (i.e., agree on issues, support each other, present clear expectations to their child). Finally, dyadic conflict was measured with one code for each dyadic pair: the level of conflict between the mother and child, father and child, and mother and father. In accordance with past recommendations (Landis & Koch, 1977), variables that had ICCs < .40 were dropped. Based on this criterion, dyadic parental unity at Time 4 for the TD group and mother–father dyadic conflict at Time 5 for the TD group were not included in subsequent analyses. All other interrater and scale reliability values were deemed acceptable (Hartmann & Wood, 1990; Landis & Koch, 1977; see Table II).

Parent-Level Behaviors

This study measured specific parenting behaviors directed toward the child as well as non-specific parent behaviors that were more generalized in nature and not necessarily directed toward the child. Maternal and paternal behaviors were analyzed separately.

Parenting behaviors included acceptance, behavioral control, and psychological control. Acceptance was measured by averaging the ratings across the following five codes: (1) listens to others, (2) humor and laughter, (3) open or warm, (4) anger (reverse-coded), and (5) supportiveness. Behavioral control included the following two codes: (1) overt power and (2) parental structuring of the task. Psychological control included the following five codes: (1) pressures others to agree, (2) the nature of parental control—democratic (reverse-coded), (3) tolerates differences and disagreements (reverse-coded), (4) receptive to statements made by others (reverse-coded), and (5) nature of parental control—overprotective.

General parent behaviors included positive engagement, positive affect, and conflict behavior. Positive engagement included five codes: (1) clarity, (2) listens, (3) confidence, (4) involvement, and (5) explains. Positive affect included five codes: (1) intensity, (2) warmth, (3) supportive, (4) anger (reversed-coded), and (5) humor. Finally, conflict behavior included two codes: (1) disagrees and (2) tolerates disagreements (reversed-coded). In accordance with past recommendations (Landis & Koch, 1977), variables that had ICCs < .40 were dropped, which included paternal conflict behavior at Time 3 for the SB group. All other interrater and scale reliability values were deemed acceptable (Hartmann & Wood, 1990; Landis & Koch, 1977; see Table II).

Youth-Level Behaviors

Youth behaviors included positive engagement, positive affect, conflict behavior, and dependent behavior. Positive engagement, positive affect, and conflict behavior were measured using the same codes as listed previously. Child dependent behavior included two codes: (1) child engages in exploratory behavior (reverse-coded) and (2) child expresses individual views/opinions (reverse-coded).

Statistical Analysis

All data analyses were conducted using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS version 22). Group differences (SB vs. TD) were conducted at each time point via either analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs) or multivariate analyses of covariance (MANCOVAs) with univariate follow-up. Specifically, family variables (i.e., family cohesion, dyadic parental unity, dyadic conflict) were examined using ANCOVAs because the MANCOVA algorithm uses listwise deletion for missing values; use of MANCOVA when observed father behaviors were included (i.e., dyadic parental unity, mother–father conflict, father–child conflict) would have reduced the n of all analyses to only those families with both mother and father participants, thus excluding all single-parent families or families where fathers did not participate. Separate MANCOVAs, with univariate follow-up, were conducted for maternal parenting behaviors (i.e., acceptance, behavioral control, psychological control), paternal parenting behaviors, general maternal behaviors (i.e., positive engagement, positive affect, conflict behavior), general paternal behaviors, and youth behaviors (i.e., positive engagement, positive affect, conflict behavior, dependent behavior).

Although the SB and TD groups did not differ on SES at Time 1 (see Table I), the TD group (M = 47.94, SD = 10.7) had higher SES compared with the SB group (M = 43.57, SD = 10.4) at Time 5 (t(92) = −1.99, p < .05), due to differential attrition of families of TD youth with lower SES. Therefore, SES was controlled for in all analyses. Assuming a power of .80, and an α of .05, a sample of 26 is required to detect large effect sizes (partial η2 = .14) and a sample size of 64 is required to detect medium effect sizes (partial η2 = .06) for analyses with two groups (Cohen, 1992; Richardson, 2011). Thus, the current study had enough power to detect medium to large effect sizes.

Results

Tables III–V display all adjusted means and test statistics, including effect sizes. Thus, they are not repeated here in the text. Adjusted means for each variable represent the mean after inclusion of covariates. As stated previously, some of the codes included in each family, parent, and youth construct included slightly different anchors for the 5-point Likert scale. For example, the code for dyadic parental unity used a Likert scale where 1 indicated “almost not at all” and 5 indicated “very much,” while the code for supportive used a Likert scale where 1 indicated “very rejecting” and 5 indicated “very supportive.” Despite such differences, we used the following general scale to facilitate “clinical” interpretations of the findings: 1 = almost never, 2 = rarely, 3 = sometimes, 4 = often, 5 = almost always. In other words, the following sections provide information on the group differences that reached statistical significance across family, parent, and youth behaviors, as well as a description of the average frequency/intensity that these behaviors were demonstrated.

Table III.

ANCOVA Findings With Group Means and Standard Deviations for Family Behavior Variables

| Variable | Time 1 (ages 8–9 years) | Time 2 (ages 10–11 years) | Time 3 (ages 12–13 years) | Time 4 (ages 14–15 years) | Time 5 (ages 16–17 years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family cohesion | F(1, 129) = 4.66* | F(1, 119) = 0.01ns | F(1, 115) = 0.24ns | F(1, 106) = 0.22ns | F(1, 95) = 0.12ns |

| SB: 4.11 (.52) | SB: 4.20 (.40) | SB: 4.03 (.49) | SB: 3.89 (.48) | SB: 3.81 (.50) | |

| TD: 4.32 (.42) | TD: 4.23 (.39) | TD: 4.03 (.48) | TD: 3.92 (.63) | TD: 3.83 (.59) | |

| η2 = .04 | η2 = .00 | η2 = .00 | η2 = .00 | η2 = .00 | |

| Dyadic parental unity | F(1, 102) = 0.24ns | F(1, 82) = 11.78** | F(1, 74) = 6.80* | Not tested1 | F(1, 64) = 0.68ns |

| SB: 3.77 (.63) | SB: 3.78 (.38) | SB: 3.66 (.39) | SB: 3.42 (.80) | SB: 3.44 (.49) | |

| TD: 3.75 (.54) | TD: 3.49 (.40) | TD: 3.43 (.44) | TD: 3.28 (.55) | TD: 3.45 (.43) | |

| η2 = .00 | η2 = .13 | η2 = .08 | η2 = .01 | ||

| Dyadic conflict | |||||

| Mother–father | F(1, 102) = 1.17ns | F(1, 85) = 4.24* | F(1, 79) = 1.85ns | F(1, 69) = 0.06ns | Not tested1 |

| SB: 1.31 (.36) | SB: 1.42 (.32) | SB: 1.39 (.30) | SB: 1.44 (.35) | SB: 1.54 (.42) | |

| TD: 1.37 (.41) | TD: 1.59 (.44) | TD: 1.51 (.42) | TD: 1.41 (.32) | TD: 1.64 (.34) | |

| η2 = .01 | η2 = .05 | η2 = .02 | η2 = .00 | ||

| Mother–youth | F(1,129) = 0.26ns | F(1, 118) = 3.44ns | F(1, 113) = 3.94ns | F(1, 102) = 1.21ns | F(1, 91) = 2.69ns |

| SB: 1.59 (.44) | SB: 1.70 (.43) | SB: 1.76 (.44) | SB: 1.74 (.40) | SB: 1.82 (.51) | |

| TD: 1.53 (.42) | TD: 1.83 (.48) | TD: 1.91 (.49) | TD: 1.81 (.59) | TD: 1.99 (.45) | |

| η2 = .00 | η2 = .03 | η2 = .03 | η2 = .01 | η2 = .03 | |

| Father–youth | F(1, 102) = 0.35ns | F(1,83) = 1.96ns | F(1,76) = 1.02ns | F(1,72) = 0.09ns | F(1,65) = 0.08ns |

| SB: 1.53 (.48) | SB: 1.61 (.45) | SB: 1.69 (.35) | SB: 1.68 (.44) | SB: 1.79 (.57) | |

| TD: 1.48 (.37) | TD: 1.75 (.50) | TD: 1.76 (.36) | TD: 1.70 (.51) | TD: 1.77 (.41) | |

| η2 = .00 | η2 = .02 | η2 = .01 | η2 = .00 | η2 = .00 |

Note. 1Group differences were not examined for this variable at this time point because interrater reliability was below .40 for the TD group (Landis & Koch, 1977). SB = spina bifida group; TD = typically developing group. η2 = partial eta-squared. Analyses controlled for socioeconomic status at Time 1, measured by Hollingshead Four Factor Index. Significant results are in bold print.

*p < .05, **p < .01, ns = not significant.

Family Behaviors

Compared with families of TD youth, families of youth with SB displayed significantly less cohesion at Time 1, although family cohesion was displayed “often” by both groups. Compared with parents of TD youth, parents of youth with SB displayed significantly more dyadic unity at Time 2 and Time 3, and demonstrated less mother–father conflict at Time 2; such unity was demonstrated “often” by parents in the SB group and “sometimes” by parents of the TD group, and mother–father conflict was demonstrated “almost never” for the SB group and “rarely” for the TD group (see Table III).

Parent Behaviors

Results revealed a significant difference in maternal parenting behaviors between the groups at Time 1, Time 3, Time 4, and Time 5. Specifically, mothers of youth with SB displayed significantly more psychological control compared with mothers of TD youth at Time 1; psychological control was displayed “rarely” by mothers of both groups. In addition, mothers of youth with SB displayed more behavioral control at Time 3, Time 4, and Time 5; generally, behavioral control was displayed “often” by mothers of both groups. No differences in paternal parenting behaviors were found. Moreover, no differences in general parent behaviors were found for either mothers or fathers (see Table IV).

Table IV.

MANCOVA Findings With Group Means and Standard Deviations for Parenting and General Parent Variables

| Variable | Time 1 (ages 8–9 years) | Time 2 (ages 10–11 years) | Time 3 (ages 12–13 years) | Time 4 (ages 14–15 years) | Time 5 (ages 16–17 years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parenting—maternal | F(3, 127) = 3.39* | F(3, 116) = 1.85ns | F(3, 111) = 3.14* | F(3, 100) = 3.30* | F(3,89) = 3.43* |

| η2 = .07 | η2 = .08 | η2 = .09 | η2 = .10 | ||

| Acceptance | ns | ns | ns | ns | |

| Behavioral control | ns | F(1, 113) = 7.12** | F(1,102) = 7.10** | F(1,91) = 8.34* | |

| SB: 4.06(.43) | SB: 3.81(.35) | SB: 3.70(.24) | |||

| TD: 3.85(.40) | TD: 3.61(.40) | TD: 3.53(.34) | |||

| η2 = .06 | η2 = .07 | η2 = .08 | |||

| Psychological control | F(3, 127) = 3.39* | ns | ns | ns | |

| SB: 2.05(.35) | |||||

| TD: 1.90(.30) | |||||

| η2 = .04 | |||||

| Parenting—paternal | F(3, 100) = 1.34ns | F(3, 81) = 1.79ns | F(3, 74) = 0.89ns | F(3, 70) = 1.25ns | F(3, 63) = 1.13ns |

| Acceptance | |||||

| Behavioral control | |||||

| Psychological control | |||||

| General behavior—maternal | F(3, 127) = 1.17ns | F(3, 116) = 1.57ns | F(3, 111) = 1.36ns | F(3, 100) = 0.29ns | F(3, 89) = 0.78ns |

| Positive engagement | |||||

| Positive affect | |||||

| Conflict behavior | |||||

| General behavior—paternal | F(3, 100) = 0.92ns | F(3, 181) = 1.39ns | F(2, 75) = 0.92ns,1 | F(3, 70) = 0.71ns | F(3, 63) = 0.16ns |

| Positive engagement | |||||

| Positive affect | |||||

| Conflict behavior |

Note. The top lines for parenting and general behaviors display MANCOVA results, with univariate follow-up analyses presented underneath; no univariate analyses were conducted if the omnibus MANCOVA was nonsignificant. 1Analysis did not include the conflict behavior variable at this time point because interrater reliability was below .40 for the SB group (Landis & Koch, 1977). SB = spina bifida group; TD = typically developing group. η2 = partial eta-squared. Analyses controlled for socioeconomic status at Time 1, measured by Hollingshead Four Factor Index. Significant results are in bold print.

*p < .05, **p < .01, ns = not significant.

Youth Behaviors

Compared with TD youth, youth with SB displayed significantly less positive engagement and more dependent behavior at all five time points. Positive engagement was displayed “sometimes” by youth with SB at almost all time points, but was displayed “often” by TD youth at all time points. While TD youth displayed dependent behavior “almost never,” youth with SB displayed this behavior “rarely.” In addition, youth with SB displayed significantly less conflict behavior at Time 2 and Time 3; both groups displayed conflict behavior “rarely.” Lastly, youth with SB displayed significantly more positive affect at Time 4; youth from both groups displayed positive affect “sometimes” at this time point (see Table V).3

Table V.

MANCOVA Findings With Group Means and Standard Deviations for Youth Behavior Variables

| Variable | Time 1 (ages 8–9 years) | Time 2 (ages 10–11 years) | Time 3 (ages 12–13 years) | Time 4 (ages 14–15 years) | Time 5 (ages 16–17 years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Youth behavior | F(4,126) = 15.55*** | F(4,116) = 8.45*** | F(4,112) = 10.47*** | F(4,103) = 9.60*** | F(4,92) = 6.89*** |

| η2 = .33 | η2 = .23 | η2 = .27 | η2 = .27 | η2 = .23 | |

| Positive engagement | F(1,129) = 40.98*** | F(1,119) = 24.50*** | F(1,115) = 4.60* | F(1,106) = 9.16** | F(1, 95) = 5.93* |

| SB: 3.26 (.54) | SB: 3.46 (.42) | SB: 3.58 (.43) | SB: 3.45 (.44) | SB: 3.45 (.35) | |

| TD: 3.80 (.36) | TD: 3.88 (.39) | TD: 3.79 (.44) | TD: 3.74 (.39) | TD: 3.68 (.39) | |

| η2 = .24 | η2 = .17 | η2 = .04 | η2 = .08 | η2 = .06 | |

| Positive affect | ns | ns | ns | F(1,106) = 6.13* | ns |

| SB: 3.40 (.29) | |||||

| TD: 3.25 (.48) | |||||

| η2 = .06 | |||||

| Conflict behavior | ns | F(1,119) = 7.88** | F(1,115) = 7.18** | ns | ns |

| SB: 1.82 (.44) | SB: 1.98 (.42) | ||||

| TD: 2.08 (.54) | TD: 2.19 (.49) | ||||

| η2 = .06 | η2 = .06 | ||||

| Dependent behavior | F(1,129) = 24.59*** | F(1,119) = 27.60*** | F(1,115) = 31.87*** | F(1,106) = 5.94* | F(1,95) = 17.80*** |

| SB: 2.40 (.74) | SB: 2.14 (.66) | SB: 2.27 (.67) | SB: 2.47 (.71) | SB: 2.22 (.58) | |

| TD: 1.82 (.53) | TD: 1.56 (.48) | TD: 1.66 (.45) | TD: 2.10 (.61) | TD: 1.71 (.50) | |

| η2 = .16 | η2 = .19 | η2 = .22 | η2 = .05 | η2 = .16 |

Note. The top line displays MANCOVA results, with univariate follow-up analyses presented underneath. SB = spina bifida group; TD = typically developing group. η2 = partial eta-squared. Analyses controlled for socioeconomic status at Time 1, measured by Hollingshead Four Factor Index. Significant results are in bold print.

*p < .05, ** p < .01, ***p < .001, ns = not significant.

Discussion

The purpose of this five-wave longitudinal study was to examine areas of resilience and disruption with respect to family, parent, and child functioning in families of youth with SB at different points from preadolescence to late adolescence. Consistent with previous cross-sectional research on this sample that examined observed family interactions during preadolescence (Holmbeck, Coakley, et al., 2002), results from this longitudinal study are consistent with a resilience–disruption model of family functioning (Costigan et al., 1997), such that these families demonstrate disruption in some domains but resilience in others.

While differences in functioning were found between families of youth with SB and families of TD youth, it is important to emphasize that there were many dimensions on which families consistently did not differ significantly, including: mother–child and father–child dyadic conflict, maternal acceptance, paternal parenting behaviors, and maternal and paternal general behaviors (i.e., positive engagement, positive affect, and conflict behavior). The lack of differences in these domains may suggest that these are areas in which the presence of having a child with SB does not alter or disrupt normative family functioning. Put another way, these null findings may reflect that, despite the significant physical, psychological, and social demands that are placed on children with SB and their families, they are able to adapt to adversity and maintain normative developmental functioning, thus demonstrating resilience.

As was expected, the differences observed between groups during preadolescence (i.e., Holmbeck, Coakley, et al., 2002; Holmbeck, Shapera, et al., 2002) did not always hold at later points during adolescence. Based on past developmental research on TD youth, it is well-established that the transition to adolescence is characterized by a variety of changes for children and their families (e.g., pubertal changes, increased demand of autonomy), which may lead to disruption (Steinberg, 2005). However, previous research suggests that families of youth with SB are not as responsive to developmental change (e.g., they do not experience increases in conflict related to pubertal change, the youth lag behind in autonomy development; Friedman et al., 2009; Holmbeck & Devine, 2010). Consistent with this pattern of findings, the current study found that families of youth with SB demonstrated considerable resilience compared with families of TD youth during the transition to adolescence (i.e., ages 10–13 years). Specifically, within families of youth with SB, parents presented as more united and displayed less dyadic conflict, and youth displayed less conflict behavior. Taken together, while TD youth experience a variety of changes as they transition to adolescence that may have a significant impact on the youth, parents, and the family unit, families of youth with SB do not appear to experience such disruptions.

The current study also found that mothers of youth with SB displayed more behavioral control during middle to late adolescence. This suggests there is a shift in the group differences for maternal parenting behaviors from preadolescence to late adolescence. Although mothers of youth with SB displayed more psychological control in parenting during preadolescence (i.e., disruption), mothers adapt during the transition to adolescence and display more behavioral control in parenting (i.e., resilience) that appears to continue through the later stages of adolescence. In general, behavioral control is conceptualized as an adaptive parenting behavior, and may reflect behaviors such as limit- and rule-setting that provide youth with structure and guidance as they begin making their own decisions (Baumrind, 1991). As suggested previously, if mothers view their children as more vulnerable because of their complex medical presentation, they may exert more control to establish structure and set rules in an effort to protect their children. This may especially be the case during adolescence when youth are simultaneously beginning to demand more independence. Considering that youth with SB lag behind their peers in autonomy development by roughly 2 years (Davis, Shurtleff, Walker, Seidel, & Duguay, 2006; Devine, et al., 2011; Friedman et al., 2009), middle adolescence is likely the stage when such youth will exert more independence, begin to take charge of their medical care responsibilities, and “catch up” with their peers in terms of individual decision making (Friedman et al., 2009). Such increases in autonomy during middle adolescence may also help to explain why youth displayed more positive affect during this period. On the other hand, given that adherence rates are poorer for adolescents when children have more medically related responsibilities (Psihogios & Holmbeck, 2013), mothers may adaptively exert more behavioral control in an effort to facilitate the smooth transfer of medical care responsibilities, as well as ensure that proper attention is given to these important tasks.

Lastly, at each time point from preadolescence to late adolescence (i.e., Times 1–5, ages 8–9 to 16–17 years), youth were observed to demonstrate consistent disruption in terms of less positive engagement (i.e., less clarity and elaboration of expressed ideas, poorer listening skills, less confidence, less overall involvement) and more dependent behavior (i.e., less exploratory behavior, less expression of individual views/opinions) during family discussions. This builds on previous research that found similar differences during preadolescence (Holmbeck, Coakley, et al., 2002), and suggests that youths’ interaction styles with their parents are consistent, regardless of age or whether or not there are changes in other family or parenting behaviors. These results also suggest that although youth with SB may “catch up” to TD peers in some ways (e.g., individual decision making; Friedman et al., 2009), there are several ways in which they do not. However, our results cannot clarify whether the disruption in engagement and independent behavior is due to certain aspects of the child’s neuropsychological functioning (e.g., impairments in executive function and attention, Rose & Holmbeck, 2007), learned passivity that may result from higher levels of parental control (Holmbeck, Shapera, et al., 2002), or a general lack of interest or motivation during family discussions.

This study was strengthened by the use of longitudinal data that spanned 8 years, which grounded the results within a developmental framework through the consideration of how the management of a chronic illness may be at odds with the typical developmental changes of childhood and adolescence (Holmbeck, Greenly, Coakley, Greco, & Hagstrom, 2006; Kelly, Zebracki, Holmbeck, & Gershenson, 2008). In addition, the use of observational data offers a unique perspective on families, and avoids self-report bias that may be present with the use of questionnaire data. Lastly, this study highlights the importance of studying mothers and fathers separately, as no differences were found between fathers of youth with SB and fathers of TD youth. More differences may have emerged between the groups for mothers because mothers are typically the primary caregivers, or because more mothers participated, yielding more statistical power.

Still, this study is not without limitations. First, families of adolescents with SB showed greater attrition during the course of the study. It is possible that families who did not participate at later time points were those experiencing more overall disruption; thus, the areas of resilience found in our study may be an overestimate of the functioning in the general population of families of youth with SB. Second, the results of this study are primarily generalizable to English-speaking White families. Future studies should include a more representative sample based on race/ethnicity, with a particular focus on Latino families, given that the highest rates of SB are found in the Latino population (CDC, 2009; Devine, Holbein, Psihogios, Amaro, & Holmbeck, 2012). Third, although the coders of the observational data were blind to the specific hypotheses of this study, they were not blind to the group status of children (SB vs. TD). While they were instructed not to base their ratings on their knowledge of the child’s group status, it is still possible that some coders may have been biased in their ratings. Fourth, the observational tasks used in this study represent novel and structured interactive family tasks (vs. everyday activities or medical tasks). Thus, results are based on non-naturalistic conditions that may not generalize to actual family discussions and interactions. Fifth, although scales were only analyzed if deemed to meet acceptable levels of rater and scale reliability (Hartmann & Wood, 1990; Landis & Koch, 1977), there was a wide range of scale reliabilities presented. Finally, while several group differences in family, parent, and youth behaviors reached statistical significance, we are unable to determine to any degree of precision the extent to which these differences are clinically meaningful.

Future studies should examine which constructs explain the group differences in family, parent, and youth behaviors over time. Similarly, it is important for future studies to examine how family and parenting behaviors may predict youths’ interaction behaviors, medical outcomes, and psychosocial adjustment across adolescence. Youth with SB are at risk for higher rates of adjustment problems that often extend into adulthood, specifically internalizing problems and social problems (Bellin et al., 2010; Holmbeck et al., 2003). Future studies may also examine whether the identified areas of resilience and disruption continue through adulthood and differ according to salient child and family characteristics, including cognitive functioning, illness severity, gender, and SES. It is possible that parents tailor their behavior according to the severity of their child’s cognitive and physical delays, and special attention should be given to disease characteristics that may affect family, parent, and youth interaction behaviors. Lastly, using a pediatric (rather than TD) comparison group would highlight areas of resilience and disruption that are unique to SB versus areas of resilience and disruption that are generalizable to other pediatric chronic illnesses.

The present findings have several implications for working with youth with SB and their parents in a clinical setting. For example, professionals can target the interpersonal passivity and dependent behavior of children with SB to promote more adaptive social functioning with peers. Relatedly, youth with SB would benefit from interventions that facilitate their independent functioning and self-reliance. Interventions that target these domains would be most beneficial early on, before adolescence, and should build on resiliency factors already present within the family system. For example, the maintenance of positive parent behaviors that already exist within the family system, including parental behavioral control and a unified parental presence, may be helpful in informing clinical practice and may foster child and family adjustment in this special population. Because families of youth with SB appear to be resilient to the stresses of managing a child’s chronic illness across a variety of domains, these resilience skills may help to buffer against the disruptions to the family system that occur with the presence of a child with a chronic physical condition.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Illinois Spina Bifida Association as well as staff of the spina bifida clinics at Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, Shriners Hospital for Children-Chicago, and Loyola University Medical Center. We also thank the numerous undergraduate and graduate research assistants who helped with data collection and data entry. Finally, and most importantly, we thank the parents and children who participated in this study.

Funding

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01HD048629) and the March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation (FY13-0271). This study is part of an ongoing, longitudinal study.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

Footnotes

1 Some of the results during preadolescence have been reported previously for some of the variables (Holmbeck, Coakley, et al., 2002; Holmbeck, Shapera, et al., 2002), but they are included here because the variable set has been expanded and because the findings of these earlier studies can be compared directly to those at the future time points included in this article. We have also added an additional time point beyond what was included in our previous manuscripts that examined growth trajectories (Friedman et al., 2009; Holmbeck et al., 2010; Jandasek et al., 2009).

2 A copy of this coding system is available on request from Grayson N. Holmbeck.

3 To address potential familywise error rate, multiple correction procedures were conducted (e.g., the one-step Bonferroni adjustment). With each of these correction procedures, the following differences were no longer significant: dyadic parental unity at Time 3, maternal psychological control at Time 1, and maternal behavioral control at Times 4 and 5. However, unadjusted results are reported in the tables, given the potential inappropriateness of such procedures (e.g., they decrease the rate of Type 1 error but increase the rate of Type II error; Perneger, 1998). In addition, effect sizes are provided in the tables, as these are appropriate indicators of statistical significance.

References

- Anderson B. J., Coyne J. C. (1993). Family context and compliance behavior in chronically ill children. In Krasnegor N. A., Epstein L., Johnson S. B., Yaffe S. J. (Eds.), Developmental Aspects of Health Compliance Behavior (pp. 77–89). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D. (1991). Effective parenting during the early adolescent transition. In Cowan P. A., Hetherington M. (Eds.), Family transitions (pp. 111–163). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Bellin M. H., Zabel T. A., Dicianno B. E., Levey E., Garver K., Linroth R., Braun P. (2010). Correlates of depressive and anxiety symptoms in young adults with spina bifida. Journal of Pediatric Psychology , 35, 778–789. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] (2009). Racial/ethnic differences in the birth prevalence of spina bifida-United States, 1995–2005. MMWR , 57, 1409–1413. Retrieved from: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5753a2.htm [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. (1992). A power primer. Quantitative Methods in Psychology , 112(1), 155–159. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costigan C. L., Floyd F. J., Harter K. S. M., McClintock J. C. (1997). Family process and adaptation to children with mental retardation: Disruption and resilience in family problem-solving interactions. Journal of Family Psychology , 11, 515–529. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.11.4.515 [Google Scholar]

- Davis B. E., Shurtleff D. B., Walker W. O., Seidel K. D., Duguay S. (2006). Acquisition of autonomy skills in adolescents with myelomeningocele. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology , 48, 253–258. doi:10.1017/ S0012162206000569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devine K. A., Holbein C. E., Psihogios A. M., Amaro C. M., Holmbeck G. N. (2012). Individual adjustment, parental functioning, and perceived social support in Hispanic and non-Hispanic white mothers and fathers of children with spina bifida. Journal of Pediatric Psychology , 37, 769–778. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsr083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devine K. A., Wasserman R. M., Gerschensen L. S., Holmbeck G. N., Essner B. S. (2011). Mother-adolescent agreement regarding decision-making autonomy: A longitudinal comparison of families of adolescents with and without spina bifida . Journal of Pediatric Psychology , 36, 277–288. doi:10.1093/ jpepsy/jsq093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira A. J. (1963). Decision making in normal and pathological families. Archived of General Psychiatry , 8, 68–73. doi:10.1001/ jama.1963.03700010125049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman D., Holmbeck G. N., DeLucia C., Jandasek B., Zebracki K. (2009). Trajectories of autonomy development across the adolescent transition in children with spina bifida. Rehabilitation Psychology , 54, 16–27. doi:10.1037/a0014279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann D. P., Wood D. D. (1990). Observational methods. In Bellack A. S., Hersen M., Kazdin A. E. (Eds.), International handbook of behavior modification and therapy (2nd ed., pp. 107–138). New York, NY: Plenum. [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead A. B. (1975). Four factor index of social status. New Haven, CT: Yale University. [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck G. N., Coakley R. M., Hommeyer J., Shapera W. E., Westhoven V. (2002). Observed and perceived dyadic and systemic functioning in families of preadolescents with spina bifida. Journal of Pediatric Psychology , 27, 177–189. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.2.177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck G. N., DeLucia C., Essner B., Kelly L., Zebracki K., Friedman D., Jandasek B. (2010). Trajectories of psychosocial adjustment in adolescents with spina bifida: A 6-year, four-wave longitudinal follow-up. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology , 78, 511–525. doi: 10.1037/a0019599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck G. N., Devine K. A. (2010). Psychological and family functioning in spina bifida. Developmental Disabilities , 16(1), 40–46. doi: 10.1002/ddrr.90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck G. N., Greenley R. N., Coakley R. M., Greco J., Hagstrom J. (2006). Family functioning in children and adolescents with spina bifida: An evidence-based review of research and interventions. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics , 27(3), 249–277. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200606000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck G. N., Johnson S. Z., Wills K., McKernon W., Rolewick S., Skubic T. (2002). Observed and perceived parental overprotection in relation to psychosocial adjustment in pre-adolescents with a physical disability: The mediational role of behavioral autonomy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology , 70(1), 96–110. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.70.1.96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck G. N., Shapera W. E., Hommeyer J. S. (2002). Observed and perceived parenting behaviors and psychosocial adjustment in preadolescents with spina bifida. In Barber B. K. (Ed.), Intrusive parenting: How psychological control affects children and adolescents (pp. 191–234). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck G. N., Westhoven V. C., Phillips W. S., Bowers R., Gruse C., Nikolopoulos T., Tortura C. M., Davison K. (2003). A multimethod, multi-informant, and multidimensional perspective on psychosocial adjustment in preadolescents with spina bifida. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology , 71, 782–796. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.4.782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jandasek B., Holmbeck G. N., DeLucia C., Zebracki K., Friedman D. (2009). Trajectories of family processes across the adolescent transition in youth with spina bifida. Journal of Family Psychology , 23, 726–738. doi: 10.1037/a0016116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson S. Z., Holmbeck G. N. (1995). Manual for OP coding system. Unpublished manual. [Google Scholar]

- Kaugars A. S., Zebracki K., Kichler J. C., Fitzgerald C. J., Greenley R. N., Alemzadeh R., Holmbeck G. N. (2011). Use of the Family Interaction Macro-coding System with families of adolescents: Psychometric properties among pediatric and healthy populations. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 36, 539–551. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsq106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly L. M., Zebracki K., Holmbeck G. N., Gershenson L. (2008). Adolescent development and family functioning in youth with spina bifida. Journal of Pediatric Rehabilitation Medicine, 1, 291–302. Retrieved from: http://iospress.metapress.com/content/1523m6xh616h1083/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis J. R., Koch G. G. (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics , 33, 159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perneger T. V. (1998). What’s wrong with Bonferroni adjustments. British Medical Journal , 316, 1236–1238. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7139.1236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psihogios A. M., Holmbeck G. N. (2013). Discrepancies in mother and child perceptions of spina bifida medical responsibilities during the transition to adolescence: Associations with family conflict and medical adherence. Journal of Pediatric Psychology , 38, 859–870. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jst047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson J. T. E. (2011). Eta squared and partial eta squared as measures of effect size in educational research. Educational Research Review , 6, 135–147. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2010.12.001 [Google Scholar]

- Rose B. M., Holmbeck G. N. (2007). Attention and executive functions in adolescents with spina bifida. Journal of Pediatric Psychology , 32, 983–994. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. (1985). Resilience in the face of adversity: Protective factors and resistance to psychiatric disorder. The British Journal of Psychiatry , 147, 598–611. doi: 10.1192/bjp.147.6.598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smetana J. G., Yau J., Restrepo A., Braegas J. L. (1991). Adolescent-parent conflict in married and divorced families. Developmental Psychology , 27, 1000–1010. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.27.6.1000 [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. (2005). Adolescence (7th ed.) New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Stepansky M. A., Roache C. R., Holmbeck G. N., Shultz K. (2009). Medical adherence in young adolescents with spina bifida: Longitudinal associations with family functioning. Journal of Pediatric Psychology , 35, 167–176. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suen H. K., Ary D. (1989). Analyzing quantitative behavioral observation data. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Susman E. J., Rogel A. (2004). Puberty and psychological development. In Lerner R. M., Steinberg’s L. (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology (2nd ed., pp. 15–44). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Thomasgard M., Shonkoff J. P., Metz W. P., Edelbrock C. (1995). Parent–child relationship disorders. Part II: The vulnerable child syndrome and its relation to parental overprotection. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics , 16, 251–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]