Abstract

Objective Identified patterns of connectedness in youth with cancer and demographically similar healthy peers. Method Participants included 153 youth with a history of cancer and 101 youth without a history of serious illness (8–19 years). Children completed measures of connectedness, posttraumatic stress symptoms (PTSS), and benefit-finding. Parents also reported on children’s PTSS. Results Latent profile analysis revealed four profiles: high connectedness (45%), low connectedness (6%), connectedness primarily to parents (40%), and connectedness primarily to peers (9%). These profiles did not differ by history of cancer. However, profiles differed on PTSS and benefit-finding. Children highly connected across domains displayed the lowest PTSS and highest benefit-finding, while those with the lowest connectedness had the highest PTSS, with moderate PTSS and benefit-finding for the parent and peer profiles. Conclusion Children with cancer demonstrate patterns of connectedness similar to their healthy peers. Findings support connectedness as a possible mechanism facilitating resilience and growth.

Keywords: adjustment, cancer, children, connectedness, resilience

Children with cancer face a myriad of treatment and illness-related stressors; however, rates of psychopathology tend to be comparable with those seen in typically developing youth (Eiser, Hill & Vance, 2000; Noll et al., 1999; Patenaude & Kupst, 2005). More specifically, children with a history of cancer display relatively low levels of posttraumatic stress (PTSS), anxiety, and depressive symptoms (Gerhardt et al., 2007; Phipps et al., 2014; Phipps, Larsen, Long, & Rai, 2006). Children with cancer also tend to report perceptions of positive change and growth as a result of their disease (Barakat, Alderfer, & Kazak, 2006; Currier, Hermes, & Phipps, 2009), with higher perceived benefit, or challenge-related growth compared with their healthy counterparts (Phipps et al., 2014; Zebrack et al., 2012). Thus, children with a history of cancer seem to be generally well-adjusted and resilient. However, variability remains and a subset of children experience adjustment problems. Identifying processes that facilitate growth and resilience may provide insight into how best to promote positive adjustment for the children who display adjustment difficulties.

Survivors of childhood cancer often identify their supportive relationships with surrounding people (e.g., parents, medical team members) as an integral and positive aspect of the cancer experience (Phillips & Jones, 2014; Trask et al., 2003). Indeed, experiencing a positive and satisfying sense of connection to others—a sense of attachment, active involvement, and engagement with family, peers, school, and neighborhood—has been found to play a strong role in youth’s psychological adjustment (e.g., Barber & Schluterman, 2008). In contrast with social support, which generally refers to assistance from surrounding people, connectedness connotes a reciprocal relationship such that children value, enjoy, and seek to actively contribute to relationships and systems where they feel a sense of belonging and support (Karcher, Holcomb, & Zambrano, 2008). Although children likely experience social support from their connections (e.g., family, neighbors, school), children’s active engagement and the comfort they derive from their involvement are key components of connectedness. Importantly, connectedness has been identified as a process that facilitates resilience (Fergus & Zimmerman, 2013). Specifically, connectedness with parents and family has been found to play a protective function among at-risk youth (Aronowitz & Morrison-Beedy, 2004; DeVet, 1997). Furthermore, a sense of connectedness with school appears to play a protective role for students after significant stressful events, including exposure to natural disasters, terrorism (McDermott, Berry, & Cobham, 2012), and bullying (Moscardino, Scrimin, Capello, & Gianmarco, 2014), whereas low levels of connectedness predict children’s development of PTSS (McDermott et al., 2012; Moscardino et al., 2014).

Although social support has previously been demonstrated to be a protective factor for children with cancer (e.g., Trask et al., 2003), connectedness has not been studied in the pediatric oncology population. However, the extant literature does suggest that children with chronic illness display lower connectedness in some domains, such as to their school (Svavarsdottir, 2008), an effect that is likely compounded by frequent absences. Among survivors of childhood cancer, a positive relationship with parents has been found to predict better psychological functioning (Orbuch, Parry, Chesler, Fritz, & Repetto, 2005). A sense of connectedness to peers has also been found to relate to positive outcomes (Yugo & Davidson, 2007), with such support buffering the effect of low connectedness to ones parents in children with chronic illness (Herzer, Umfress, Aljadeff, Ghai, & Zakowski, 2009). Moreover, interventions designed to increase a sense of connectedness with peers for children with chronic illness have resulted in decreases in loneliness (e.g., Battles & Wiener, 2002). This research suggests that although children with chronic illness may experience decreased connectedness with peers and school as a result of their illness, variations in connectedness may be a mechanism that accounts for variability in psychological adjustment and resilience.

Connectedness has primarily been studied from the perspective of isolated domains (e.g., associations between connectedness at school and children’s psychological functioning); however, because children develop within interdependent systems (e.g., peers, school, community; Bernat & Resnick, 2009), it is important to understand connectedness in relation to multiple, interdependent systems, and to determine patterns of connection across domains (Shin & Yu, 2012; Witherspoon, Schotland, Way, & Hughes, 2009). When this has been done, findings suggest that although some children are highly connected across domains, other children are connected to only one or two domains (e.g., peers and neighborhood) while being low in others (e.g., family; Shin & Yu, 2012; Witherspoon et al., 2009). In other words, when a person-centered approach has been taken, a different, more complex picture emerged of children’s connectedness. These findings indicate that connectedness may be best understood from a person-centered rather than a variable-centered perspective.

Connectedness has been examined primarily in relation to such outcomes as internalizing and externalizing difficulties, risky behaviors, and physical health. In contrast, limited literature has considered the impact connectedness may have on positive outcomes such as posttraumatic growth (PTG), or the perceived benefit from experiencing a stressful or traumatic event. There is a broad literature linking social support and PTG in adults (Prati & Pietrantoni, 2009; Swickert & Hittner, 2009), including adults with cancer (Morris & Shakespeare-Finch, 2011). These links have yet to be established in youth with cancer. Given the protective function connectedness plays in typically developing youth, it is certainly reasonable to expect that connectedness may promote growth in addition to resilience in children with cancer.

In the present study, we sought to examine connectedness in children with cancer and a demographically similar comparison group of children without history of serious illness. Given our aim to examine connectedness within multiple, interdependent systems, our first objective was to identify patterns of connectedness across social and familial domains (e.g., peers, school, family, neighborhood). We sought to identify such patterns using a person-centered approach to empirically identify whether subgroups exist with shared, characteristic profiles of connectedness across domains. Although differences may exist in connectedness across different types of chronic illness, it is first important to understand patterns of connectedness in children with cancer and to evaluate whether such patterns are different from children without history of serious illness. Thus, we sought to examine whether youth’s profile membership significantly differed according to their health status (cancer vs. healthy comparison group), as well as according to their cumulative experience of stressful life events and demographic characteristics (age, gender, socioeconomic status [SES]). Given previous findings regarding decreased school connectedness for children with chronic illness (Svavarsdottir, 2008), it was predicted that children with cancer would be less likely to present with profiles characterized by higher school and peer connectedness. We also hypothesized that these profiles of connectedness would significantly relate to PTSS (assessed via child and parent report) and PTG.

Method

Procedure

This project was part of a larger longitudinal study of coping and adjustment in children with cancer. Data for this project were obtained during the second phase of data collection, approximately 12 months after initial recruitment. This study was approved by the institutional review board and informed consent/assent was obtained at each assessment time point. Participants were provided with a small monetary compensation for their time.

Participants

Patient Group

At baseline, eligibility criteria for children with cancer included (a) a primary diagnosis of malignancy; (b) at least 1 month from diagnosis; (c) able to read and speak English; and (d) have no significant cognitive or sensory deficits that would impede completion of measures. Children were recruited from four strata based on time since diagnosis (1–6 months, 6 months to 2 years, 2–5 years, and ≥5 years). At baseline, 70% of patients recruited agreed to participate, and of those invited to participate at time-2 (data collection is ongoing), 98% (n = 153) agreed and completed measures. Patients who agreed to participate at baseline did not differ from those who declined with regard to age, gender, race/ethnicity, or diagnostic category. Demographic and diagnostic information for children in the cancer group is presented in Table I.

Table I.

Demographic Information Across Study Groups

| Percent |

||

|---|---|---|

| Cancer group | Control group | |

| N = 153 | N = 101 | |

| Age (years) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 13.96 (2.97) | 13.21 (3.06) |

| Range | 8–19 | 8–19 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 50.3 | 53.5 |

| Female | 49.7 | 46.5 |

| Race | ||

| White | 71.2 | 75.2 |

| Black | 24.2 | 19.8 |

| Hispanic | 1.3 | 2.0 |

| Asian | 1.3 | 1.0 |

| Multiple race | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Socioeconomic statusa | ||

| Group I | 15.7 | 14.9 |

| Group II | 14.4 | 29.7 |

| Group III | 27.5 | 30.7 |

| Group IV | 25.5 | 17.8 |

| Group V | 17.0 | 6.9 |

| Diagnostic category | ||

| Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | 22.2 | |

| Acute myeloid leukemia | 7.2 | |

| Hodgkin’s and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | 12.4 | |

| Solid tumor | 41.8 | |

| Brain tumor | 16.3 | |

| Time since diagnosis | ||

| <18 months | 30.7 | |

| 18 months to 3 years | 17.3 | |

| 3–6 years | 21.3 | |

| >6 years | 30.7 | |

| On treatment | 16.3 | |

| Relapsed | 11.1 | |

aSocioeconomic status (SES) was calculated using Barratt Simplified Measure of Social Status (Barratt, 2006). Group I reflects higher SES while Group V indicates lower SES.

Comparison Group

Typically developing children were initially recruited from the community via a two-step process. First, permission slips were distributed at area schools describing the study and asking parents for permission to be contacted for possible study enrollment. At that time, parents were also asked to provide demographic information (child age, gender, race/ethnicity, parent education/occupation), and this information was used to create a pool of potential participants. Using frequency matching, children in the control group were matched to participants in the cancer group based on age, gender, race/ethnicity, and SES. Parents were then contacted by a member of the research team, given an overview of the study, and invited to participate. Eligibility criteria included ability to read and speak English, no known cognitive deficits, and no history of chronic or life-threatening illness. The majority (86%) of potential control participants contacted based on demographic match agreed to participate and completed baseline measures; 91% (n = 101; two declined, eight lost to follow-up) agreed to return for Time 2. Participant demographics at Time 2 are presented in Table I.

Children in the two groups did not significantly differ based on age, gender, or ethnicity; however, the groups significantly differed in SES (χ2(4, N = 254) = 13.56, p = .009). SES was calculated using Barratt Simplified Measure of Social Status (Barratt, 2006), and fewer children from the control group were from the lower SES strata.

Measures

Hemingway Measure of Adolescent Connectedness

The Hemingway Measure of Adolescent Connectedness (HMAC; Karcher, 2005; Karcher & Sass, 2010) is a 57-item self-report measure that assesses a child’s positive connections to their social environment using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very true). The measure consists of 10 subscales assessing five broader domains of connectedness: (1) school (school and teacher); (2) family (parents and siblings); (3) peers (friends and peers); (4) neighborhood; and (5) self (present self, future self, reading). For the present study, the school, teacher, parents, siblings, friends, peers, and neighborhood subscales were used. Sample items include “My friends and I talk openly with each other about personal things,” “I enjoy spending time with my parents,” and “I always try hard to earn my teachers’ trust.” Although the HMAC was created and validated with adolescents (Karcher, 2005; Karcher & Sass, 2010), it has also been used with children as young as 9 years old with adequate reliability (Karcher, 2008; Karcher, Davidson, Rhodes, & Herrera, 2010). Psychometric properties are strong, with reliabilities ranging from .77 to .86 across subscales. Cronbach’s αs for the present study were as follows: School = .89; Teacher = .73; Parents = .81; Siblings = .89; Friends = .79; Peers = .76; Neighbors = .88.

UCLA PTSD Reaction Index for DSM-IV

The UCLA PTSD Reaction Index for DSM-IV (PTSDI; Pynoos, Rodriguez, Steinberg, Stuber, & Frederick, 1998) is a 22-item measure assessing the frequency of DSM-IV PTSD symptoms in the past month in reference to a self-identified stressful or traumatic life event. Importantly, to avoid potential focusing effects that would imply that the cancer experience is traumatic, the cancer group was not oriented to cancer but was asked to spontaneously identify their most stressful or traumatic event. This measure was used to assess frequency of symptoms as a metric of continued distress from the event, rather than as a means of diagnosing PTSD; therefore, scores were obtained regardless of whether the event met DSM-IV A1 criterion (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). For the current study, this measure was completed by participants (self-report) and a parent (proxy-report), and the total scores from both were used for analyses. The PTSDI has excellent psychometric properties. Cronbach’s α was .92 for child report and .91 for parent report.

Benefit Finding/Burden Scale for Children

The Benefit Finding/Burden Scale for Children (BBSC; Currier, Hermes, & Phipps, 2009; Phipps, Long, & Ogden, 2007) is a 20-item self-report measure designed to assess potential benefits or burdens of stressful life events. Participants were asked to complete the measure with regard to the most difficult or stressful event that they had identified for the PTSDI. Domains assessed include affect, relationships with peers, and family, with items rated on a 5-point Likert scale. Although three items relating to positive changes in relationship closeness with friends or family (“This event has helped me learn who my real friends are,” “This event has helped me to make some new best friends,” and “This event has brought my family closer together”) might overlap with youth’s feeling of connectedness with friends and family, items from this measure are specific to relationship changes resulting from the youth’s most difficult or stressful event. The BBSC has been shown to be reliable and valid in children with cancer, with benefit and burden emerging as independent constructs. The Benefit Finding subscale, which assesses a child’s perception of personal growth as a result of a self-identified significant life event, was used for the current study. Cronbach’s α for cancer-related events was .91 and .88 for noncancer events.

Life Events Scale

Children completed a modified version of the Life Events Scale (LES; Johnston, Steele, Herrera, & Phipps, 2003). The LES consists of 30 stressful life events of a wide range of severity (e.g., death of a parent, breakup of a romantic relationship, birth of a sibling). The total number of self-reported events across the child's lifetime was used for analyses. This scale has been found to have good reliability (Johnston et al., 2003).

Statistical Analysis

Latent profiles of connectedness were empirically derived using latent profile analysis (LPA). Mplus version 7.3 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2014) was used for all analyses, with missing data estimated using full information maximum likelihood (>90% coverage). LPA is a latent variable mixture modeling approach used to identify homogeneous subgroups (latent classes) of individuals that exist within a heterogeneous population based on profiles of the variable (indicator) means (Berlin, Williams, & Parra, 2014). In other words, rather than examining the relation among variables, which aggregates data across individuals and thus does not allow for individual differences in profiles or patterns of indicator means, LPA allows for identification and comparison of clusters of individuals who share a similar profile of indicator means. Children are probabilistically assigned to subgroups based on their most likely class membership, with fractional membership allowed. In the present study, LPA was used to identify latent classes of children with different profiles of connectedness based on the HMAC measure.

To identify the optimal model, models with different numbers of latent classes are run and compared for model fit and interpretability. Model fit was compared using the Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC; Schwarz, 1978), entropy, the Lo-Mendell-Rubin test (LMR; Lo, Mendell, & Rubin, 2001), and the Bootstrap Likelihood Ratio Difference Test (BLRT; McLachlan & Peel, 2000). To determine how cancer status (cancer vs. healthy control), age, SES, and gender relate to the identified latent profiles of connectedness as covariates, the three-step approach was implemented (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2012; Vermunt, 2010). The three-step approach allows covariates to be tested as predictors of latent classes in a multinomial logistic regression while maintaining the probabilistic nature of the latent class variable. To compare differences in children’s PTSS and benefit-finding across latent profiles, the equality of means in child PTSS and benefit-finding across classes was tested using the modified Bolck-Croon-Hagenaars (BCH) method (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2014; Bakk & Vermunt, 2014), which permits comparison of classes while taking into account participants’ partial membership in classes.

Results

Data Description

Means, standard deviations, and correlations for all variables are presented in Table II. The mean scores demonstrate that, on average, children were reporting moderate to moderate/high levels of connectedness across domains. Children with and without cancer did not differ on any of the connectedness subscales, stressful life events, or PTSS. However, children with cancer reported higher levels of benefit finding (M = 30.75, SD = 10.92), compared with healthy controls (M = 26.61, SD = 9.64), t(251) = 3.09, p = .002. Child-report PTSS differed across SES, F(4, 248) = 4.26, p = .002, such that children in the lowest strata reported higher PTSS than children in higher strata. Correlations suggested that children reporting a greater number of stressful life events tended to report lower connectedness in most domains, as well as higher PTSS. There was consistency in the child's connectedness across domains, as connectedness was positively correlated across domains. Older children reported higher benefit-finding, more stressful life events, and lower connectedness. Connectedness was associated with more benefit-finding and lower PTSS. For children with cancer, time since diagnosis did not significantly correlate with any of the connectedness subscales (all p > .05).

Table II.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations Between all Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | – | |||||||||||

| 2. SLE | .21** | – | ||||||||||

| 3. C. Neighborhood | −.32*** | −.12 | – | |||||||||

| 4. C. Friend | .10 | .04 | .19** | – | ||||||||

| 5. C. Parent | −.19** | −.28*** | .33*** | .21** | – | |||||||

| 6. C. Sibling | <−.01 | −.15* | .27*** | .21** | .47*** | – | ||||||

| 7. C. School | −.17** | −.38*** | .20** | .24*** | .52*** | .40*** | – | |||||

| 8. C. Peer | −.11 | −.27*** | .31*** | .33*** | .46*** | .28*** | .61*** | – | ||||

| 9. C. Teacher | −.08 | −.24*** | .26*** | .28*** | .55*** | .35*** | .56*** | .51*** | – | |||

| 10. Child-report PTSS | −.01 | .38*** | −.17** | −.17** | −.27*** | −.14* | −.30*** | −.35*** | −.25*** | – | ||

| 11. Parent-report PTSS | .07 | .21** | −.14* | −.14* | −.25*** | −.11 | −.25*** | −.21** | −.23*** | .34*** | – | |

| 12. Benefit-Finding | .28*** | .10 | .08 | .21** | .19** | .20** | .12* | .09 | .19** | .15* | .08 | – |

| M | 13.68 | 7.81 | 3.20 | 4.00 | 4.11 | 3.97 | 3.83 | 3.77 | 4.10 | 19.07 | 14.80 | 29.10 |

| SD | 3.02 | 3.66 | 1.07 | 0.78 | 0.71 | 0.94 | 0.72 | 0.75 | 0.66 | 15.24 | 11.60 | 10.60 |

Note. C = connectedness; SLE = stressful life events; PTSS = posttraumatic stress symptoms. N = 254.

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Empirically Derived Profiles of Connectedness

Four LPA models were fit to the data, specifying a varying number of classes (two to five classes). The BIC, Entropy, LMR, and BLRT for the models are presented in Table III. The four-class solution resulted in the lowest BIC, and the LMR suggested that the four-class model had a marginally better fit to the data than the three-class model. The BLRT supported a model with five or more classes; however, as the BLRT has been found to overestimate the number of classes (Nylund, Asparouhov, & Muthén, 2007), these results were used to verify that our chosen model provided appropriate fit to the data relative to a model with one fewer class, rather than to identify the best-fitting model. Although the LMR suggested that a two-class solution was superior to the one-class solution, the two-class solution was not as strongly supported by the other indicators of model fit (e.g., BIC). The four-class model was further supported by relatively high entropy, high mean class assignment probabilities for the most likely class (88.8–95.3%), and low rates of misclassification ( < 0.1–5.5%), suggesting that participants have been classified into their most likely subgroup with relatively high certainty and accuracy (Rost, 2006). In addition, the four-class model provided the most interpretable results. Thus, a four-class model was selected as the final model.

Table III.

Comparison of Model Fit for Latent Profile Analysesa

| Classes per model | Bayesian information criteria | Entropy | Lo-Mendell-Rubin test p-value | Bootstrap likelihood ratio test p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 3908.42 | .82 | .0000 | .0000 (1 vs. 2 classes) |

| 3 | 3849.38 | .83 | .3558 | .0000 (2 vs. 3 classes) |

| 4 | 3845.85 | .88 | .0513 | .0000 (3 vs. 4 classes) |

| 5 | 3850.75 | .87 | .5312 | .0000 (4 vs. 5 classes) |

aValues in bold indicate the fit indices for the selected model.

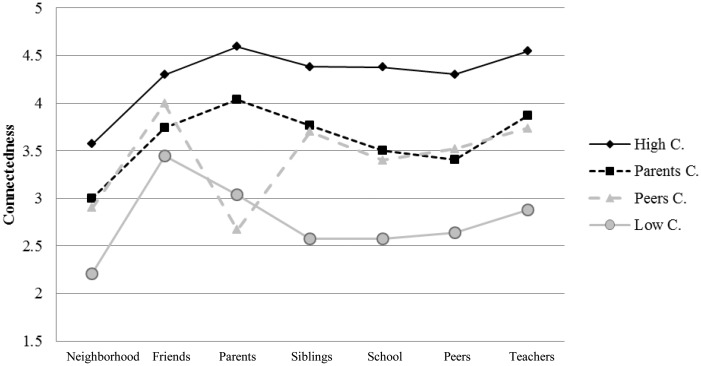

The four profiles that emerged (Figure 1) were labeled as follows: “High Connectedness” (n = 115, 45%), characterized by the highest levels of connectedness across all indicators; “Low Connectedness” (n = 14, 6%), characterized by low levels of connectedness in all domains; “Connectedness to Parents” (n = 101, 40%) characterized by higher connectedness to parents; and “Connectedness to Peers” (n = 24, 9%) characterized primarily by higher connectedness to friends. Although the latter two groups were relatively similar across domains, they were distinguished primarily by participants’ report of connectedness to parents or friends, respectively.

Figure 1.

Latent profiles of children’s perceived connectedness across domains.

Demographic Covariates for the Connectedness Profiles

Given prior research finding significant demographic differences in youth connectedness (Witherspoon et al., 2009), and a dearth of research examining differences in connectedness for children with and without chronic illness, demographic differences across profiles were examined using multinomial logistic regressions. No significant differences were found across profiles for cancer status, gender, or SES (all p > .05). However, profiles differed significantly by age and cumulative stressful life events. Specifically, older participants were more likely to be in the low (odds ratio [OR] = 1.24, p = .02) or peer connectedness (OR = 1.27, p = .007) profiles compared with the parent or high connectedness profiles. Participants reporting more cumulative stressful life events had greater likelihood of membership in the low connectedness profile (ORs = 1.24–1.41; all p < .05) compared with the other profiles, as well as greater likelihood of membership in the parent profile compared with the high connectedness profile (OR = 1.13, p = .01).

Relation Between Connectedness Profiles and Children’s Adjustment

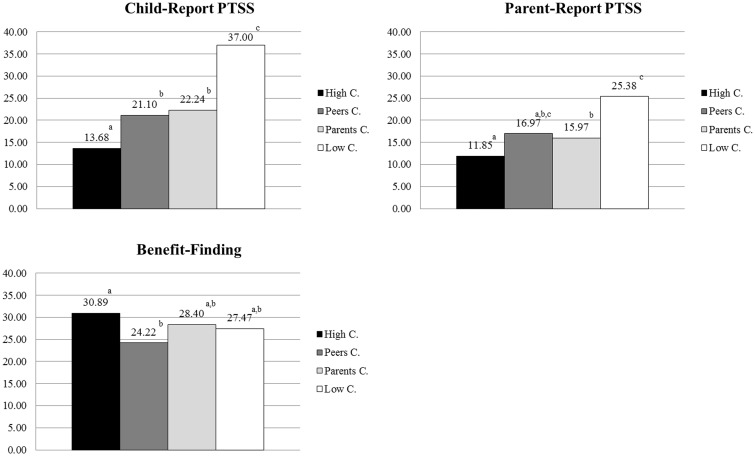

To examine the relation between connectedness profiles and children’s adjustment, equality of means in child PTSS and benefit-finding across latent classes were tested using the modified BCH method (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2014; Bakk & Vermunt, 2014) and the chi-square statistic. These results are presented in Figure 2. For each outcome, significant differences were found across the four profiles: Child-Report PTSS: χ2 (3, N = 254) = 29.45, p < .001; Parent-Report PTSS: χ2 (3, N = 254) = 16.47, p = .001; and Benefit-Finding: χ2 (3, N = 254) = 8.38, p = .039. As shown in Figure 2, the more connected children were, the lower their reported PTSS. Parent-reported child PTSS mirrored these findings, with the exception that the Peer Connectedness group did not significantly differ from the other three profiles. Interestingly, the Parent and Peer Connectedness profiles did not significantly differ on any outcome. Highly connected children reported the most benefit-finding; however, the Peer Connectedness class was the only class to report significantly lower benefit-finding in comparison with the Highly Connected group.

Figure 2.

Comparisons of adjustment across classes. Categories with different letters in the superscript were significantly different at p < .05.

Discussion

The present study examined profiles of connectedness in children with and without cancer in relation to children’s adjustment (PTSS and benefit-finding). Findings both support and extend prior research, suggesting that children with cancer are resilient to this potentially challenging event, and provide evidence suggesting that connectedness to social and familial domains (e.g., friends, parents, school, neighborhood) may support their development of resilience. More specifically, the majority of children (cancer and control) reported being highly connected across all social domains (45%), with relatively few children being disconnected from all domains (6%). Interestingly, profiles of connectedness also emerged that were distinguished primarily by children’s connectedness to parents versus peers.

Presence or absence of cancer history did not predict profile membership, suggesting that children with a cancer history are experiencing neither diminished nor enhanced connectedness relative to healthy peers. This contrasts with prior findings, suggesting that children with chronic illness become more isolated (Battles & Wiener, 2002; Svavarsdottir, 2008). Although this suggests that children with cancer may differ from those with other chronic illnesses, it may also be attributable to differences in analytic approach. Moreover, the findings suggest that, in addition to resilience in psychological adjustment (Eiser et al., 2000; Patenaude & Kupst, 2005), children with cancer also appear to be resilient in their social and familial functioning. This is consistent with findings regarding the lack of significant differences between children with and without chronic illness in their social functioning (Noll et al., 1999) and emotional support from parents (Kazak & Meadows, 1989), as well as the existing literature pointing to parents and friends as some of the key sources of support for children with cancer (Trask et al., 2003). It is important to note that children in this study were 18 months to >6 years postdiagnosis, and the majority had completed treatment; therefore, children in the cancer group may be less likely to be experiencing the type of heightened support or isolation that accompany their initial diagnosis. Nonetheless, these findings, together with the findings that children generally reported a high sense of connection to at least one if not multiple social domains, paint a hopeful picture that children with a history of cancer experience resilience with regard to their connectedness. In contrast, cumulative stressful life events predicted a more disconnected profile. Thus, in comparison with other life events, the cancer experience may be less likely to result in social isolation, perhaps owing to its inherent demand for the family, medical staff, and others to mobilize in service of the child’s treatment (Decker, 2007; McCubbin, Balling, Possin, Frierdich, & Bryne, 2002).

Children who are highly connected across all seven domains reported the lowest PTSS and highest benefit-finding, with moderate PTSS/benefit-finding for the parent and peer profiles. Parental report of children’s PTSS replicated these findings. Thus, connectedness appears to show a dose-response effect in promoting resilience and growth such that greater connectedness across domains predicts more resilience and growth than connectedness in just one or two domains, though any connectedness is better than low or no connectedness across domains. Findings are consistent with the literature, suggesting that school connectedness facilitates children’s adjustment to traumatic events (McDermott et al., 2012; Moscardino et al., 2014) and suggesting that connectedness across other domains could also play a protective role. Longitudinal research is needed to further elucidate the possible mediating role of connectedness in promoting resilience as well as to clarify the likely complex relation between connectedness, stressful life events, and PTSS.

Although profiles of high connectedness and disconnectedness across domains are consistent with prior findings (Shin & Yu, 2012; Witherspoon et al., 2009), profiles distinguished primarily according to connectedness with parents versus peers are novel. The age differences across these profiles, together with the larger age range of this study compared with Shin and Yu (2012) and Witherspoon and colleagues (2009), suggest developmental changes in connectedness. Specifically, as expected from a developmental standpoint, adolescents were more likely to experience connectedness with and reliance on the peer group, with increased autonomy from family (Helsen, Vollerbergh, & Meeus, 2000). As parent and peer profiles did not differentially predict PTSS/benefit-finding, it appears that children experience the benefits of connectedness regardless of domain. In other words, it appears that youth benefit from a sense of connection to either parents or peers, without a differential impact on their PTSS or benefit-finding. This is consistent with findings that peer support can compensate for nonsupportive parents (Herzer et al., 2009).

Given the apparent link between profiles of connectedness and children’s PTSS, it may be valuable to screen for connectedness across domains as a means of identifying children who may be at greater risk for developing PTSS. Children reporting low levels of connectedness across domains or connectedness in only one or two domains may benefit from targeted intervention. These findings also support connectedness as a potential intervention target that could promote resilience and protect against development of adjustment concerns, particularly loneliness (Battles & Wiener, 2002). Indeed, connectedness has been a target of many school-based prevention and positive youth development programs (Roth & Brooks-Gunn, 2003), with systemic interventions that simultaneously target the children and their school, family, and community systems, often facilitated by school counselors (Karcher et al., 2008). Given that children’s health status did not predict their profile membership, it is reasonable to expect that children with cancer might similarly benefit from such systemic interventions to facilitate increased connectedness across social and familial domains. Questions of who implements such interventions and how they can be adapted when children are physically removed from their family, peer, school, and neighborhood systems remain to be answered; however, present findings suggest the value in considering how facilitating connectedness could promote resilience and growth in children with cancer.

When considering our findings, it should be noted that the present study is correlational, cross-sectional, and single-site, thus limiting the ability to draw causal conclusions and to generalize these findings. Nonetheless, given the limited literature examining connectedness in children with cancer, the present findings warrant further examination of social and familial connectedness as possible facilitators of growth and resilience. More specifically, future research may wish to examine connectedness longitudinally to determine potential changes in connectedness from diagnosis to survivorship. The present findings are also specific to the pediatric oncology population. Although cancer is often thought to elicit support in a different way than other chronic illnesses (e.g., diabetes), it is unclear if and how these findings might differ in the context of other types of chronic illness, necessitating further research to generalize to other medical populations. Lastly, it should be noted that connectedness with the medical team—a relationship that is likely relevant for children being treated for a chronic illness but not applicable for typically developing children—was not assessed. It will be important for future research to explore how this unique domain of connectedness fits into these patterns, and potentially changes over time.

This study provides further support for the resilience of children with cancer. Children with cancer did not differ from healthy children in their membership to profiles of connectedness to social and familial domains. Moreover, patterns of higher connectedness appeared to be associated with lower rates of PTSS and greater reports of benefit-finding. As such, findings suggest that connectedness may be a possible mechanism that facilitates growth and resilience in children with cancer, and thus may be a domain that is amenable to intervention. In considering attempts to promote children’s resilience, children may benefit from the facilitation of a continued sense of connection with family, peers, and school.

Acknowledgments

Funding

National Institutes of Health (NIH) R01 CA136782. The American Lebanese-Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC).

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Text Revision (4th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Aronowitz T., Morrison-Beedy D. (2004). Resilience to risk-taking behaviors in impoverished African American girls: The role of mother-daughter connectedness. Research in Nursing and Health, 27, 29–39. doi: 10.1002/nur.20004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asparouhov T., Muthén B. (2012). Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: A 3-step approach using Mplus. Mplus Web Note 15. Retrieved from https://www.statmodel.com/download/webnotes/webnote15.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Asparouhov T., Muthén B. (2014). Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: Using the BCH method in Mplus to estimate a distal outcome model and an arbitrary second model. Mplus Web Notes: No. 21 Retrieved from https://www.statmodel.com/download/asparouhov_muthen_2014.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Bakk Z., Vermunt J. K. (2014). Robustness of stepwise latent class modeling with continuous distal outcomes. Forthcoming in Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. Retrieved from http://members.home.nl/jeroenvermunt/bakk2014.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Barakat L. P., Alderfer M. A., Kazak A. E. (2006). Posttraumatic growth in adolescent survivors of cancer and their mothers and fathers. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 31, 413–419. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber B. K., Schluterman J. M. (2008). Connectedness in the lives of children and adolescents: A call for greater conceptual clarity. Journal of Adolescent Health, 43, 209–216. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barratt W. (2006). The Barratt simplified measure of social status (BSMSS). Indiana State University; Retrieved from http://www2.uncp.edu/home/marson/syllabi/1020BSMSS.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Battles H. B., Wiener L. S. (2002). Starbright World: Effects of an electronic network on the social environment of children with life-threatening illnesses. Children's Health Care, 31, 47–68. doi: 10.1207/S15326888CHC3101_4 [Google Scholar]

- Berlin K. S., Williams N. A., Parra G. R. (2014). An introduction to latent variable mixture modeling (part 1): Overview and cross-sectional latent class and latent profile analyses. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 39, 174–187. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jst084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernat D. H., Resnick M. D. (2009). Connectedness in the lives of adolescents. In DiClemente R. J., Santelli J. S., Crosby R. A. (Eds.), Adolescent health: Understanding and preventing risk behaviors (pp. 375–389). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Currier J. M., Hermes S., Phipps S. (2009). Brief report: Children’s response to serious illness: Perceptions of benefit and burden in a pediatric cancer population. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 34, 1129–1134. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker C. L. (2007). Social support and adolescent cancer survivors: A review of the literature. Psycho-Oncology, 16, 1–11. doi: 10.1002/pon.1073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVet, K. A. (1997). Parent-adolescent relationships, physical disciplinary history, and adjustment in adolescents. Family Process, 36(3), 311–322. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1997.00311.x. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Eiser C., Hill J. J., Vance Y. H. (2000). Examining the psychological consequences of surviving childhood cancer: Systematic review as a research method in pediatric psychology. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 25, 449–460. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/25.6.449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergus S., Zimmerman M. A. (2013). Adolescent resilience: A framework for understanding healthy development in the face of risk. Annual Review of Public Health, 26, 399–419. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhardt C. A., Yopp J. M., Leininger L., Valerius K. S., Correll J., Vannatta K., Noll R. B. (2007). Post-traumatic stress during emerging adulthood in survivors of pediatric cancer. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 32, 1018–1023. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helsen M., Vollebergh W., Meeus W. (2000). Social support from parents and friends and emotional problems in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 29, 319–335. doi: 10.1023/a:1005147708827 [Google Scholar]

- Herzer M., Umfress K., Aljadeff G., Ghai K., Zakowski S. G. (2009). Interactions with parents and friends among chronically ill children: Examining social networks. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 30, 499–508. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181c21c82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston C. A., Steele R. G., Herrera E. A., Phipps S. (2003). Parent and child reporting of negative life events: Discrepancy and agreement across pediatric samples. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 28, 579–588. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsg048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karcher M. J. (2005). The Hemingway: Measure of Adolescent Connectedness: A manual for scoring and interpretation. Unpublished manuscript, University of Texas at San Antonio. Retrieved from http://adolescentconnectedness.com/media/HemManual2006.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Karcher M. J. (2008). The study of mentoring in the learning environment (SMILE): A randomized evaluation of the effectiveness of school-based mentoring. Prevention Science, 9, 99–113. doi: 10.1007/s11121-008-0083-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karcher M. J., Davidson A. J., Rhodes J. E., Herrera C. (2010). Pygmalion in the program: The role of teenage peer mentors' attitudes in shaping their mentees' outcomes. Applied Developmental Science, 14, 212–227. doi: 10.1080/10888691.2010.516188 [Google Scholar]

- Karcher M. J., Holcomb M., Zambrano E. (2008). Measuring adolescent connectedness: A guide for school-based assessment and program evaluation. In Coleman H. L. K., Yeh C. (Eds.), Handbook of school counseling (pp. 649–669). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Karcher M. J., Sass D. (2010). A multicultural assessment of adolescent connectedness: Testing measurement invariance across gender and ethnicity. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 57, 274–289. doi: 10.1037/a0019357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazak A. E., Meadows A. T. (1989). Families of young adolescents who have survived cancer: Social-emotional adjustment, adaptability, and social support. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 14, 175–191. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/14.2.175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Y., Mendell N. R., Rubin D. B. (2001). Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika, 88, 767–778. doi: 10.1093/biomet/88.3.767 [Google Scholar]

- McCubbin M., Balling K., Possin P., Frierdich S., Bryne B. (2002). Family resiliency in childhood cancer. Family Relations, 51, 103–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2002.00103.x [Google Scholar]

- McDermott B., Berry H., Cobham V. (2012). Social connectedness: A potential aetiological factor in the development of child post-traumatic stress disorder. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 46, 109–117. doi: 10.1177/0004867411433950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan G., Peel D. (2000). Finite mixture models. New York, NY: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Morris B. A., Shakespeare-Finch J. (2011). Rumination, post-traumatic growth, and distress: Structural equation modelling with cancer survivors. Psychooncology, 20, 1176–1183. doi: 10.1002/pon.1827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moscardino U., Scrimin S., Capello F., Gianmarco A. (2014). Well-being, school climate, and the social identity process: A latent growth model study of bullying perpetration and peer victimization. School Psychology Quarterly, 29, 320–335. doi: 10.1037/spq0000074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L., Muthén B. (1998–2014). Mplus user’s guide (5th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen. [Google Scholar]

- Noll R. B., Gartstein M. A., Vannatta K., Correll J., Bukowski W. M., Davies W. H. (1999). Social, emotional, and behavioral functioning of children with cancer. Pediatrics, 103, 71–78. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.1.71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nylund K. L., Asparouhov T., Muthén B. O. (2007). Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling, 14, 535–569. doi: 10.1080/10705510701575396 [Google Scholar]

- Orbuch T. L., Parry C., Chesler M., Fritz J., Repetto P. (2005). Parent-child relationships and quality of life: Resilience among childhood cancer survivors. Family Relations, 54, 171–183. doi: 10.1111/j.0197-6664.2005.00014.x [Google Scholar]

- Patenaude A. F., Kupst M. J. (2005). Psychosocial functioning in pediatric cancer. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 30, 9–27. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsi012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips F., Jones B. L. (2014). Understanding the lived experience of Latino adolescent and young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 8, 39–48. doi: 10.1007/s11764-013-0310-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phipps S., Klosky J. L., Long A., Hudson M. M., Huang Q., Zhang H., Noll R. B. (2014). Posttraumatic stress and psychological growth in children with cancer: Has the traumatic impact of cancer been overestimated? Journal of Clinical Oncology, 32, 641–646. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.8212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phipps S., Larson S., Long A., Rai S. N. (2006). Adaptive style and symptoms of posttraumatic stress in children with cancer and their parents. Journal of Pediatric Psychology , 31, 298–309. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phipps S., Long A. M., Ogden J. (2007). Benefit finding scale for children: Preliminary findings from a childhood cancer population. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 32, 1264–1271. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsl052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prati G., Pietrantoni L. (2009). Optimism, social support, and coping strategies as factors contributing to posttraumatic growth: A meta-analysis. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 14, 364–388. doi: 10.1080/15325020902724271 [Google Scholar]

- Pynoos R., Rodriguez N., Steinberg A., Stuber M., Frederick C. (1998). The University of California at Los Angeles Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Reaction Index (UCLA-PTSD RI) for DSM-IV (Revision 1). Los Angeles, CA: UCLA Trauma Psychiatry Program. [Google Scholar]

- Rost J. (2006). Latent-class-analyse [Latent Class Analysis]. In Petermann F., Eid M. (Eds.), Handbuch der psychologischen diagnostik [Handbook of psychological assessment] (pp. 275–287). Göttingen, Germany: Hogrefe. [Google Scholar]

- Roth J. L., Brooks-Gunn J. (2003). Youth development programs: Risk, prevention, and policy. Journal of Adolescent Health, 32, 170–182. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(02)00421-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz G. (1978). Estimating the dimension of a model. The Annals of Statistics, 6, 461–464. [Google Scholar]

- Shin H., Yu K. (2012). Connectedness of Korean adolescents: Profiles and influencing factors. Asia Pacific Education Review, 13, 593–605. doi: 10.1007/s12564-012-9222-0 [Google Scholar]

- Svavarsdottir E. K. (2008). Connectedness, belonging and feelings about school among healthy and chronically ill Icelandic schoolchildren. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 22, 463–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2007.00553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swickert R., Hittner J. (2009). Social support coping mediates the relationship between gender and posttraumatic growth. Journal of Health Psychology, 14, 387–393. doi: 10.1177/1359105308101677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trask P. C., Paterson A. G., Trask C. L., Bares C. B., Birt J., Maan C. (2003). Parent and adolescent adjustment to pediatric cancer: Associations with coping, social support, and family function. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 20, 36–47. doi: 10.1053/jpon.2003.5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermunt J. K. (2010). Latent class modeling with covariates: Two improved three-step approaches. Political Analysis, 18, 450–469. doi: 10.1093/pan/mpq025 [Google Scholar]

- Witherspoon D., Schotland M., Way N., Hughes D. (2009). Connecting the dots: How connectedness to multiple contexts influences the psychological and academic adjustment of urban youth. Applied Developmental Science, 13, 199–216. doi: 10.1080/10888690903288755 [Google Scholar]

- Yugo M., Davidson M. J. (2007). Connectedness within social contexts: The relation to adolescent health. Healthcare Policy, 2, 47–55. doi: 10.12927/hcpol.2007.18701 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zebrack B. J., Stuber M. L., Meeske K. A., Phipps S., Krull K. R., Liu Q., Yasui Y., Parry C., Hamilton R., Robison L. L., Zeltzer L. K. (2012). Perceived positive impact of cancer among long-term survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Psychooncology, 21, 630–639. doi: 10.1002/pon.1959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]