Abstract

In the mammalian testis such as in rats, a unique actin-rich cell-cell adherens junction (AJ) known as ectoplasmic specialization (ES) is found in the seminiferous epithelium. ES is conspicuously found between Sertoli cells near the basement membrane known as the basal ES, which together with tight junction (TJ), gap junction, and desmosome constitute the blood-testis barrier (BTB). The BTB, in turn, anatomically divides the seminiferous epithelium into the basal and the adluminal (apical) compartment. On the other hand, ES is also found at the Sertoli-spermatid interface known as apical ES which is the only anchoring device for developing step 8–19 spermatids during spermiogenesis. One of the most typical features of the ES is the array of actin microfilament bundles that lie perpendicular to the Sertoli cell plasma membrane and are sandwiched in-between the cisternae of endoplasmic reticulum and the Sertoli cell plasma membrane. While these actin filament bundles confer the adhesive strength of Sertoli cells at the BTB and also spermatids in the adluminal compartment, they must be rapidly re-organized from their bundled to unbundled/branched configuration and vice versa to provide plasticity to the ES so that preleptotene spermatocytes and spermatids can be transported across the immunological barrier and the adluminal compartment, respectively, during the epithelial cycle of spermatogenesis. Fascin is a family of actin microfilament cross-linking and bundling proteins that is known to confer bundling of parallel actin microfilaments in mammalian cells. A recent report has illustrated the significance of a fascin protein called fascin 1 in actin microfilaments at the ES, pertinent to its role in spermatogenesis (Gungor-Ordueri et al. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 307, E738-753, 2004 (DOI:10.1152/ajpendo.00113.2014). In this Commentary, we critically evaluate these findings in light of the role of fascin in other mammalian cells, providing some insightful information for future investigations.

Keywords: blood-testis barrier, ectoplasmic specialization, F-actin, fascin, testis, seminiferous epithelial cycle, spermatogenesis

Introduction

Fascin, an 54–56 kDa protein, is an actin binding and bundling protein by cross-linking filamentous actin into tightly packed parallel bundles in mammalian cells.1,2 Fascin 1 was first identified in sea urchin oocytes and coelomocytes and has since been shown to be evolutionally conserved, and found in multiple cell types in Drosophila, rodents, and humans.3,4 Fascin 1 is highly expressed in mammalian cells, in particular neuronal cells, fibroblasts and dendritic cells, associated with cellular structures constituted by actin filament bundles, such as stress fibers, and the assembly of filopodia (also known as microspikes), and lamellipodia,5 including filopodia of neuronal cells 6 and dendritic cells.7 To date, at least 3 fascins, namely fascin 1, 2 and 3, are found in mammalian cells. Fascin 1 is expressed in multiple mammalian cells, known to be involved in inducing actin bundling 6 including Sertoli and germ cells.8 Fascin 2 is mostly expressed in retina restricted to photoreceptors for the assembly of lamellipodial extension of photoreceptor disks, known as retinal fascin,9-11 but it is also expressed in the testis by Sertoli and germ cells.8 In contrast, fascin 3 is highly expressed in the testis, mostly in spermatids and spermatozoa, but not in Sertoli cells,12 and it is called testis fascin. Based on these findings, it is likely that fascin 3 is used for the assembly of actin filament-rich ultrastructures surrounding the spermatid nucleus 13 and the acrosome-acroplaxome-manchette complex 14,15 during spermiogenesis 12 since these ultrastructures require rapid but precise organization of actin filaments for their assembly during spermatogenesis. In short, due to its intrinsic actin binding and bundling activity since each fascin polypeptide chain contains 2 actin-binding sites located at its N- and C-terminus 2 (Fig. 1), fascin is involved in the assembly of cell protrusion, including microvilli, filopodia, lamellipodia 2 and possibly intercellular bridges in epithelial cells.16 Interestingly, fascin 1-deficient mice are viable, and fertile, without major developmental defects17 (Table 1). It must be noted that unlike humans, rodents remain fertile, such as in fascin KO mice, even though sperm outputs are at ∼10% capacity of the wild-type normal control mice,17 illustrating that the deletion of fascin 1 might cause subfertility or infertility in humans. Furthermore, embryonic fibroblasts from fascin 1−/− mice are capable of assembling filopodia even though filopodia are fewer, shorter and short-lived.18 A careful examination of these fascin 1−/− mice have shown that they possess smaller olfactory bulb due to defects in the migration of neuroblasts in the brain during postnatal development.19 These findings using a genetic model in the mouse suggest that while the function of fascin 1 can be superseded by other actin bundling proteins, such as fascin 2 and others (e.g., palladin, Eps8, ezrin), fascin 1 is important to confer mobility to neuroblasts that migrate along the rostral migratory stream to become interneurons in the olfactory bulb in developing brain,19 and its deletion in humans could still lead to infertility or subfertility. Other studies in non-neuronal cells have shown that fascin is associated with a number of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins such as thrombospondin-1 and fibronectin, and cell adhesion molecules such as integrins and syndecan-1.1-3 It is of interest to note that thrombospondin/syndecan promotes fascin-mediated actin bundling and protrusion stabilization; however, signal functions elicited by integrin and fibronectin inhibit fascin-mediated actin bundling and destabilize protrusions which is caused by PKC-dependent phosphorylation of fascin on Ser39.2,4 This phosphorylation of Ser-39 in the N-terminal actin-binding domain leads to a loss of actin bundling activity by fascin. In this Commentary, we focus our discussion on fascin 1 and its functional relationship with spermatogenesis based on recent findings20 since fascin 2 is mostly expressed in retinal cells and fascin 3 is limited to metabolically quiescent spermatids but not Sertoli cells,12 whereas fascin 1 is robustly expressed by Sertoli and germ cells in adult rat testes.20

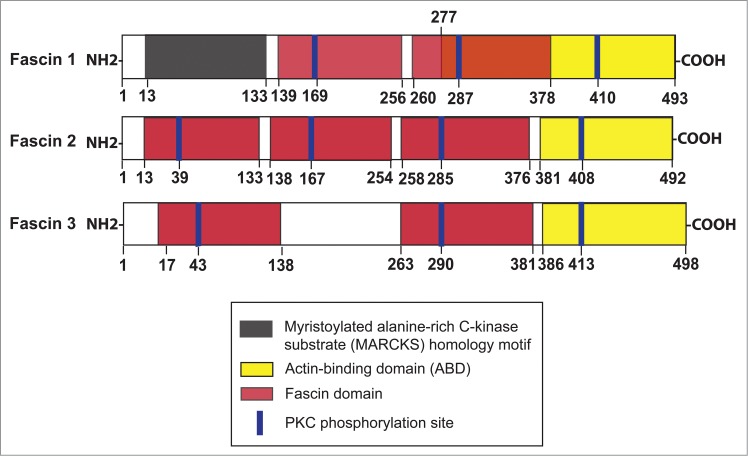

Figure 1.

Functional domains of different fascins. Fascin 1, 2 and 3 display specific organ/tissue distribution in mammalian body in which fascin 1 is found in many mammalian cells including Sertoli and germ cells in the testis. Fascin 2, also known as retinal fascin, is predominantly expressed by photoreceptors in retina, but is also expressed by Sertoli and germ cells. Fascin 3, however, is restricted to germ cells, mostly expressed by elongating/elongated spermatids and spermatozoa, but not Sertoli or Leydig cells. The actin binding domain is found near the N- (within the myristoylated alanine-rich C-kinase substrate (MARCKS) homology motif at amino acid residues 33–47 from the N-terminus) and also the C-terminus (residues 277–493 from the N-terminus) in fascin 1, which are crucial to confer fascin 1 its intrinsic activity to induce tight and stable bundles of actin microfilaments at the ES. This figure was prepared based on findings summarized in several recent reviews.1,2,4

Table 1.

Function and localization of different fascins

| Fascin | Molecular weight (Mr) | Function | Localization | Phenotype in knockout mice or mutation in humans | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fascin 1 | 54–56 kDa | Involved in the assembly of flipodia, and lamellipodia in migrating cells, such as fibroblasts; organization of actin microfilaments into parallel bundles; assembly of intercellular bridges (tunneling nanotubes) in Sertoli cells | Skin, neuronal and glial cells, endothelial cells, antigen-presenting cells and dendritic cells, Sertoli cells, elongated spermatids, Leydig cells | Viable, fertile, reduced neonatal survival. | 2,8,17,42,43 |

| Fascin 2 | 55 kDa | Involved in lamellipodia extension of photoreceptor disks, regulation of actin cross-linking in stereocilia, involved in filopodia formation, assembly of actin filament bundles in photoreceptors in retina | Retinal photoreceptors, Sertoli cells, germ cells | Mutation in humans leads to macular degeneration | 44-47 |

| Fascin 3 | 56 kDa | Involved in the terminal elongation of spermatid heads, microfilament rearrangement of sperm head during fertilization | Testis, epididymis, spermatozoa, germ cells in particular elongating and elongated spermatids, but not Sertoli cells | Not known | 8,12,48 |

Ectoplasmic Specialization – an F-Actin-Rich Adherens Junction (AJ) in the Testis

In the mammalian testis, a unique anchoring junction known as ectoplasmic specialization (ES) is found at the Sertoli-spermatid (step 8–19 or 8–16 spermatids in the rat or mouse testis, respectively) interface or Sertoli cell-cell interface at the BTB known as the apical or basal ES, respectively.21-24 The ES, unlike other actin-based anchoring junctions such as cell-cell adherens junction (AJ) and cell-matrix focal adhesion (also called focal contact); and intermediate filament-based anchoring junctions, such as cell-cell desmosome and cell-matrix hemidesmosome, are uniquely characterized by the presence of an extensive array of tightly packed actin filament bundles that lie perpendicular to the Sertoli cell plasma membrane and are sandwiched in-between the cisternae of endoplasmic reticulum and the opposing Sertoli-spermatid and Sertoli cell-cell plasma membranes at the apical and the basal ES, respectively. It is also this extensive network of actin filament bundles at the ES that confers its unusual adhesive strength, almost twice as strong as desmosome when the force that requires to tear apart apical ES vs. desmosome was quantified.25 This is rather unusual since desmosome is considered to be one of the strongest adhesive junctions that maintains the integrity of the skin.26,27 While ES is a strong adhesion junction, it undergoes extensive remodeling and/or restructuring during spermatogenesis pertinent to the transport of preleptotene spermatocytes at the BTB at stage VIII of the epithelial cycle at the basal ES, or the transport of spermatids across the adluminal compartment during spermiogenesis. Thus, it is conceivable that fascin, being an actin-binding and bundling protein, will play a crucial role in maintaining the organization of actin filament bundles at the ES, such that actin microfilaments can be rapidly converted between their bundled and unbundled/branched configuration to confer plasticity to the ES. An earlier report based on studies using in situ hybridization and immunofluorescence microscopy suggest that fascin 3 is a spermatid-specific actin bundling protein in the mouse testis and it is also associated with epididymal and ejaculated spermatozoa,12 perhaps being used in the assembly of actin filament bundles that are involved in the shaping of the spermatid head and also the acrosome-acroplaxome-manchette complex during spermiogenesis.12 However, fascin 3 is not expressed by Sertoli cells 8,12 and spermatids and sperms are metabolically quiescent cells versus Sertoli cells. Also, apical ES is a dynamic ultrastructure at the Sertoli-spermatid interface but the actin microfilament bundles are limited to the Sertoli cell, and as such, the Sertoli cell is considered to be the major contributor of apical ES function during spermatogenesis. We thus focus our discussion on fascin 1 since a recent report 20 has illustrated that fascin 1 is robustly expressed by Sertoli and germ cells in the adult rat testis, unlike fascin 3 which is restrictively expressed by germ cells, but not Sertoli cells, and fascin 1 is physiologically involved in ES dynamics during spermatogenesis.

Fascin 1 – Its Role on Ectoplasmic Specialization (ES) and Spermatogenesis

As noted in Table 1, the functions of different fascins that serve as an organizer of actin microfilaments pertinent to cell movement and anchoring junction in multiple mammalian cell types are summarized. It is increasingly clear that fascin is involved in the assembly of filopodia and lamellipodia of rapidly migrating cells such as fibroblasts, macrophages and dendritic cells since these ultrastructures rely on the rapid organization of actin microfilaments. While Sertoli cells cultured in vitro are highly motile cells, for instance, Sertoli cells cultured on bicameral units can rapidly move to the underside of an apical chamber, traversing the “pores” in the bicameral unit,28-30 analogous to metastatic tumor cells. However, Sertoli cells in vivo are polarized cells which remain in place in the seminiferous epithelium in order to foster germ cell development. For instance, each Sertoli cell nurture ∼30–50 different germ cells by sending out cytoplasmic processes to maintain close contacts via apical ES, desmosome and gap junction and to support germ cell development via chemical signals, nutrients (e.g., lactate, ions), and providing structural support.31,32 Thus, even though ultrastructures of filopodia and lamellipodia are not detectable in either germ or Sertoli cells in the seminiferous epithelium of both rodent and human testes during the epithelial cycle, preleptotene spermatocytes and developing spermatids are actively being transported across the immunological barrier and the adluminal compartment by Sertoli cells during spermatogenesis. Studies in the literature have implicated the transport of germ cells (“cargoes”) relies on the polarized actin microfilaments that serve as the “vehicle” with the “engines” provided by actin-associated motor proteins (e.g., myosin VIIa) along the “tracks” provide by the polarized microtubules (MTs) and the “track” is maintained (such as its activation) by MT-associated motor proteins (e.g.,, kinesin, dynein).21,33-35 Thus, it is envisioned that actin microfilaments undergo extensive re-organization to facilitate germ cell transport in which actin microfilaments rapidly convert between their bundled and unbundled/branched configuration so that preleptotene spermatocytes and spermatids connected in clones via intercellular bridges can be transported across the BTB and adluminal compartment, respectively.

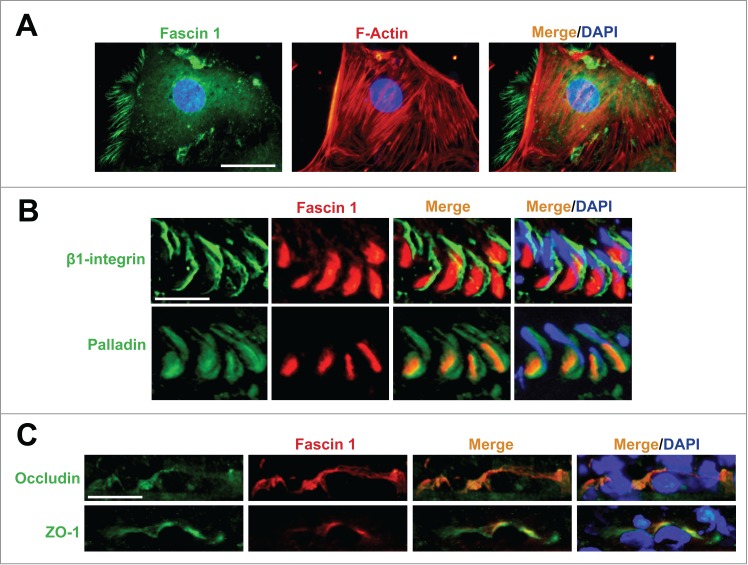

To support the role of fascin in germ cell transport, fascin 1 is shown to be highly expressed at the Sertoli-step 19 spermatid interface in stage VII tubules (Fig. 2), but it is considerably diminished in stage VIII and virtually non-detectable thereafter.8 Fascin 1 is also expressed at the BTB in stage VII-VIII tubules (Fig. 2), but considerably diminished in IX tubules.8 This tightly regulated spatiotemporal expression at the apical and basal ES during the epithelial cycle suggests the likely involvement of fascin 1 in regulating actin bundling activity at the ES. This postulate is supported by findings that fascin 1 is associated (and also co-localized) with actin cross-linking and bundling protein palladin (Fig. 2) and also branched actin polymerization protein Arp3 (actin-related protein 3, which together with Arp2 forms the Arp2/3 complex that is known to induce barbed end nucleation, effectively convert an actin microfilament to a branched configuration),8 both of which are also found in the testis, displaying similar spatiotemporal expression as of fascin 1.36,37 In short, the concerted efforts of actin bundling proteins fascin 1 and palladin, as well as branched actin-inducing protein Arp3, thus re-organize actin filalment bundles at the ES in response the transition of epithelial cycle from VII-IX, facilitating the transport of preleptotene spermatocytes (at stage VIII) and elongated spermatids (from stage VII to early VIII) as well as the release of sperm at spermiation (at late stage VIII). To further support the actin bundling activity of fascin 1, a knockdown of fascin 1 by RNAi was found to induce actin microfilament disorganization in Sertoli cell cytosol using an in vitro Sertoli cell BTB model that mimics the BTB in vivo, causing mis-localization of BTB integral membrane protein occludin, thereby perturbing the Sertoli cell tight junction-permeability function.8 The notion of fascin 1 is crucial to F-actin organization at the BTB is also supported by an in vivo experiment since the knockdown of fascin 1 in vivo was shown to associate with a mis-organization of BTB adhesion protein complex occludin and ZO-1 in which these proteins were found to be diffusively localized at the BTB accompanied by a mis-organization of F-actin at the site.8 Furthermore, a knockdown of fascin 1 in the testis in vivo also impeded F-actin organization at the apical ES, causing mis-localization of β1-integrin and laminin-γ3 chain which are the major adhesion complex at the Sertoli-spermatid interface, thereby leading to defects in spermatid polarity in which spermatid heads no longer were pointing toward the basement membrane, but became mis-aligned in the seminiferous epithelium.8 Collectively, these findings illustrate fascin 1 is a physiologically important regulator of actin microfilaments at the ES during the epithelial cycle, and it is likely working alongside with other actin bundling (e.g., palladin) and branched actin inducing proteins (e.g., Arp2/3 complex).

Figure 2.

Fascin 1 is expressed at the F-actin-rich ectoplasmic specialization in the rat testis. (A) Sertoli cells isolated from 20-day-old rat testes were cultured in vitro in serum-free chemically defined medium F12/DMEM for 4 d and stained for fascin 1, which was localized in part with actin microfilaments in the cell cytosol. Scale bar, 25 μm. (B) Fascin 1 is only partially but well co-localized with apical ES protein β1-integrin (an integral membrane protein in Sertoli cells) and palladin (an actin bundling protein), respectively, in stage VII tubules in adult rat testes. Scale bar, 35 μm. (C) Fascin 1 is also co-localized with TJ proteins occludin (an integral membrane protein) and ZO-1 (an adaptor protein) at the BTB in stage VII-VIII tubules. Scale bar, 35 μm. This experiment was performed using specific antibodies against fascin 1, β1-integrin, palladin, occludin and ZO-1 as described.8 F-actin in Sertoli cells was visualized by rhodamine phalloidin as described.8

Concluding Remarks and Future Perspectives

As briefly discussed above which are based on studies in the testis and other epithelia, fascin is a crucial regulator of actin microfilament bundles at the ES. However, the precise molecular mechanism(s) by which fascin exerts its effects on actin microfilament organization remains unclear. For instance, what triggers the robust spatiotemporal expression of fascin 1 at the concave side of spermatid head and also the basal ES/BTB at stage VII of the epithelial cycle, which is also the same site wherein palladin37 and Arp336 are robustly expressed in stage VII tubules? Is this mediated by changes in the levels of cytokines (e.g., TGF-βs, TNFα), testosterone, or their receptors in the ES microenvironment since these biomolecules 22,38-41 are shown to regulate ES dynamics or it is mediated by a yet-to-be identified biomolecules released from elongated spermatids? More important, since both actin bundling and branched microfilament-inducing proteins are co-expressed at the same site, namely the concave side of spermatid heads, what is the mechanism(s) by which the intrinsic activities of these diverse functional molecules exert their effects so that actin microfilaments at the site can be properly re-organized via a precise cascade of events? In short, this requires tightly regulated logistic sequence of expressions of these actin regulatory proteins.

*This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NICHD, U54 HD029990, Project 5 to C.Y.C; R01 HD056034 to C.Y.C.) and a fellowship from The International Research Fellowship Program 2214/A of The Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey (TUBITAK to N.E.G.O.).

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1. Hashimoto Y, Kim DJ , Adams JC. The roles of fascins in health and disease. J Pathol 2011; 224:289-300; PMID:21618240; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/path.2894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Adams JC. Roles of fascin in cell adhesion and motility. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2004; 16:590-6; PMID:15363811; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jayo A, Parsons M. Fascin: a key regulator of cytoskeletal dynamics. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2010; 42:1614-7; PMID:20601080; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.biocel.2010.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kureishy N, Sapountzi V, Prag S, Anilkumar N, Adams JC. Fascins, and their roles in cell structure and function. Bioessays 2002; 24:350-61; PMID:11948621; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/bies.10070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yamashiro-Matsumura S, Matsumura F. Intracellular localization of the 55-kDa actin-bundling protein in cultured cells: Spatial relationships with actin, alpha-actinin, tropomyosin, and fimbrin. J Cell Biol 1986; 103:631-40; PMID:3525578; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.103.2.631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Edwards RA., Bryan J. Fascins, a family of actin bundling proteins. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton 1995; 32:1-9; PMID:8674129; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/cm.970320102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ross R, Ross XL, Schwing J, Langin T, Reske-Kunz AB. The actin-bundling protein fascin is involved in the formation of dendritc processes in maturing epidermal Langerhans cells. J Immunol 1998; 160:3776-82; PMID:9558080 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gungor-Ordueri NE, Celik-Ozenci C, Cheng CY. Fascin 1 is an actin filament-bundling protein that regulates ectoplasmic specialization dynamics in the rat testis. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2014; 307:E738-53; PMID:25159326; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/ajpendo.00113.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Saishin Y., Shimada S, Morimura H, Sato K, Ishimoto I, Tano Y, Tohyama M. Isolation of a cDNA encoding a photoreceptor cell-specific actin-bundling protein: retinal fascin. FEBS Lett 1997; 414:381-6; PMID:9315724; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0014-5793(97)01021-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tubb BE., Bardien-Kruger S, Kashork CD, Shaffer LG, Ramagli LS, Xu J, Siciliano MJ, Bryan J. Characterization of human retinal fascin gene (FSCN2) at 17q25: close physical linkage of fascin and cytoplasmic actin genes. Genomics 2000; 65:146-56; PMID:10783262; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1006/geno.2000.6156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Saishin Y, Ishikawa R, Ugawa S, Guo W, Ueda T, Morimura H, Kohama K, Shimizu H, Tano Y, Shimada S. Retinal fascin: Functional nature, subcellular distribution, and chromosomal localization. Invest Ohpthalmol Vis Sci 2000; 41:2087-95; PMID:10892848 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tubb B, Mulholland DJ, Vogl W, Lan ZJ, Niederberger C, Cooney A, Bryan J. Testis fascin (FSCN3): a novel paralog of the actin-bundling protein fascin expressed specifically in the elongate spermatid head. Exp Cell Res 2002; 275:92-109; PMID:11925108; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1006/excr.2002.5486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vogl A. Distribution and function of organized concentrations of actin filaments in mammalian spermatogenic cells and Sertoli cells. Int Rev Cytol 1989; 119:1-56; PMID:2695482; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0074-7696(08)60648-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kierszenbaum AL, Tres LL. The acrosome-acroplaxome-manchette complex and the shaping of the spermatid head. Arch Histol Cytol 2004; 67:271-284; PMID:15700535; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1679/aohc.67.271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kierszenbaum AL, Rivkin E, Tres LL. Molecular biology of sperm head shaping. Soc Reprod Fertil Suppl 2007; 65:33-43; PMID:17644953 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lou E, Fujisawa S, Morozov A, Barlas A, Romin Y, Dogan Y, Gholami S, Moreira AL, Manova-Todorova K, Moore MA. Tunneling nanotubes provide a unique conduit for intercellular transfer of cellular contents in human malignant pleural mesothelioma. PLoS One 2012; 7:e33093; PMID:22427958; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0033093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Robaire B. Advancing towards a male contraceptive: A novel approach from an unexpected direction. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2003; 24:326–328; PMID:1287166; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0165-6147(03)00141-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yamakita Y, Matsumura F, Yamashiro S. Fascin 1 is dispensable for mouse development but is favorable for neonatal survival. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton 2009; 66:524-34; PMID:19343791; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/cm.20356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sonego M, Gajendra S, Parsons M, Ma Y, Hobbs C, Zentar MP, Williams G, Machesky LM, Doherty P, Lalli G. Fascin regulates the migration of subventricular zone-derived neuroblasts in the postnatal brain. J Neurosci 2013; 33:12171-85; PMID:23884926; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0653-13.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gungor-Ordueri NE, Tang EI, Celik-Ozenci C, Cheng CY. Ezrin is an actin binding protein that regulates Sertoli cell and spermatid adhesion during spermatogenesis. Endocrinology 2014; 155:3981-95; PMID:25051438; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1210/en.2014-1163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Vogl AW, Vaid KS, Guttman JA. The Sertoli cell cytoskeleton. Adv Exp Med Biol 2008; 636:186-211; PMID:19856169; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/978-0-387-09597-4_11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cheng CY, Mruk DD. A local autocrine axis in the testes that regulates spermatogenesis. Nature Rev Endocrinol 2010; 6:380-95; PMID:20571538; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrendo.2010.71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cheng CY, Mruk DD. The blood-testis barrier and its implication in male contraception. Pharmacol Rev 2012; 64:16-64; PMID:22039149; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1124/pr.110.002790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mruk DD., Silvestrini B, Cheng CY. Anchoring junctions as drug targets: Role in contraceptive development. Pharmacol Rev 2008; 60:146-80; PMID:18483144; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1124/pr.107.07105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wolski KM, Perrault C, Tran-Son-Tay R, Cameron DF. Strength measurement of the Sertoli-spermatid junctional complex. J Androl 2005; 26:354-9; PMID:15867003; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2164/jandrol.04142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Green KJ, Simpson CL. Desmosomes: new perspectives on a classic. J Invest Dermatol 2007; 127:2499-515; PMID:17934502; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.jid.5701015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Brooke MA, Nitoiu D, Kelsell DP. Cell-cell connectivity: desmosomes and disease. J Pathol 2012; 226:158-71; PMID:21989576; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/path.3027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mruk DD, Zhu LJ, Silvestrini B, Lee WM, Cheng CY. Interactions of proteases and protease inhibitors in Sertoli-germ cell cocultures preceding the formation of specialized Sertoli-germ cell junctions in vitro. J Androl 1997; 18:612-22; PMID:9432134 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Janecki A, Steinberger A. Polarized Sertoli cell functions in a new two-compartment culture system. J Androl 1986; 7:69-71; PMID:3080395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Byers S, Hadley MA, Djakiew D, Dym M. Growth and characterization of epididymal epithelial cells and Sertoli cells in dual environment culture chambers. J Androl 1986; 7:59-68; PMID:3944021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mruk DD, Cheng CY. Sertoli-Sertoli and Sertoli-germ cell interactions and their significance in germ cell movement in the seminiferous epithelium during spermatogenesis. Endocr Rev 2004; 25:747-806; PMID:15466940; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1210/er.2003-0022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cheng CY, Mruk DD. Cell junction dynamics in the testis: Sertoli-germ cell interactions and male contraceptive development. Physiol Rev 2002; 82:825-74; PMID:12270945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lee NPY, Cheng CY. Ectoplasmic specialization, a testis-specific cell-cell actin-based adherens junction type: is this a potential target for male contraceptive development. Human Reprod Update 2004; 10:349-69; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/humupd/dmh026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tang EI, Mruk DD, Cheng CY. MAP/microtubule affinity-regulating kinases, microtubule dynamics, and spermatogenesis. J Endocrinol 2013; 217:R13-R23; PMID:23449618; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1530/JOE-12-0586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Vogl AW, Young JS., Du M. New insights into roles of tubulobulbar complexes in sperm release and turnover of blood-testis barrier. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol 2013; 303:319-55; PMID:23445814; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/B978-0-12-407697-6.00008-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lie PPY, Chan AYN, Mruk DD, Lee WM, Cheng CY. Restricted Arp3 expression in the testis prevents blood-testis barrier disruption during junction restructuring at spermatogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010; 107:11411-6; PMID:20534520; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1001823107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Qian X, Mruk DD, Wong EWP, Lie PPY, Cheng CY. Palladin is a regulator of actin filament bundles at the ectoplasmic specialization in the rat testis. Endocrinology 2013; 154:1907-20; PMID:23546604; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1210/en.2012-2269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lui WY, Cheng CY. Regulation of cell junction dynamics by cytokines in the testis - a molecular and biochemical perspective. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2007; 18:299-311; PMID:17521954; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2007.04.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Xia W, Mruk DD, Lee WM, Cheng CY. Cytokines and junction restructuring during spermatogenesis - a lesson to learn from the testis. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2005; 16:469-93; PMID:16023885; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wang RS, Yeh S, Tzeng CR, Chang C. Androgen receptor roles in spermatogenesis and fertility: lessons from testicular cell-specific androgen receptor knockout mice. Endocr Rev 2009; 30:119-32; PMID:19176467; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1210/er.2008-0025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Smith LB, Walker WH. The regulation of spermatogenesis by androgens. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2014; 30:2-13; PMID:24598768; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.02.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pinkus GS, Pinkus JL, Langhoff E, Matsumura F, Yamashiro S, Mosialos G, Said JW. Fascin, a sensitive new marker for Reed-]Sternberg cells of Hodgkin's disease. Evidence for a dendritic or B cell derivation? Am J Pathol 1997; 150:543-62; PMID:9033270 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zhang FR, Tao LH, Shen ZY, Lv Z, Xu LY, Li EM. Fascin expression in human embryonic, fetal, and normal adult tissue. J Histochem Cytochem 2008; 56:193-9; PMID:17998567; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1369/jhc.7A7353.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lin-Jones J, Burnside B. Retina-specific protein fascin 2 is an cross-linker associated with actin bundles in photoreceptor innter segments and calycal processes. Invest Ohpthalmol Vis Sci 2007; 48:1380-8; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1167/iovs.06-0763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ma Y. Fascin 1 is transiently expressed in mouse melanoblasts during development and promotes migration and proliferation. Development 2013; 140:2203-11; PMID:23633513; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/dev.089789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Perrin BJ., Strandjord DM, Narayanan P, Henderson DM, Johnson KR, Ervasti JM. b-Actin and fascin-2 cooperate to maintain stereocilia length. J Neurosci 2013; 33:8114-21; PMID:23658152; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0238-13.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Jaiswal R., Breitsprecher D, Collins A, Corrêa IR, Jr, Xu MQ, Goode BL. The formin Daam1 and fascin directly collaborate to promote filopodia formation. Curr Biol 2013; 23:1373-9; PMID:23850281; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cub.2013.06.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kollers S., Day A., Rocha D. Characterization of the porcine FSCN3 gene: cDNA cloning, genomic structure, mapping and polymorphisms. Cytogenet Genome Res 2006; 115:189-92; PMID:17065803; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1159/000095242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]