Abstract

Zinc (Zn) and iron (Fe) are essential but are sometimes deficient in humans, while cadmium (Cd) is toxic if it accumulates in the liver and kidneys at high levels. All three are contained in the grains of rice, a staple cereal. Zn and Fe concentrations in rice grains harvested under different levels of soil/hydroponic metals are known to change only within a small range, while Cd concentrations show greater changes. To clarify the mechanisms underlying such different metal contents, we synthesized information on the routes of metal transport and accumulation in rice plants by examining metal speciation, metal transporters, and the xylem-to-phloem transport system. At grain-filling, Zn and Cd ascending in xylem sap are transferred to the phloem by the xylem-to-phloem transport system operating at stem nodes. Grain Fe is largely derived from the leaves by remobilization. Zn and Fe concentrations in phloem-sap and grains are regulated within a small range, while Cd concentrations vary depending on xylem supply. Transgenic techniques to increase concentrations of the metal chelators (nicotianamine, 2′-deoxymugineic acid) are useful in increasing grain Zn and Fe concentrations. The elimination of OsNRAMP5 Cd-uptake transporter and the enhancement of root cell vacuolar Cd sequestration reduce uptake and root-to-shoot transport, respectively, resulting in a reduction of grain Cd accumulation.

Keywords: cadmium, iron, metals in grains, metal speciation, metal transporter, rice (Oryza sativa L.), xylem-to-phloem transport, zinc

1. Introduction

Zinc (Zn) and iron (Fe) are required by plants in response to demands for plant growth, which is underlined by cellular metabolisms [1,2], while cadmium (Cd) is not essential for plants and is toxic at high levels. Likewise, Zn and Fe are essential in the human metabolism and their deficiency may lead to various diseases, while Cd is toxic and at high doses may even cause severe diseases like Itai-Itai disease (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demands and toxicity of Zn, Cd, and Fe for plants and impacts of their dietary deficiency or excess on humans.

| Metal | Demands/Toxicity for Plants | Deficiency Diseases/Excess Toxicity for Humans |

|---|---|---|

| Zn | Demand: Cofactor of over 300 enzymes including DNA- and RNA-polymerases; Excess toxicity: Unregulated binding of Zn to S-, N- and O-containing molecules | Deficiency: Stunting, diarrhea, pneumonia; Excess toxicity: Interference of Fe and Cu uptake in the intestines |

| Cd | Toxicity: Binding to protein SH-residues, exchanges with divalent cations such as Zn2+ and Ca2+, and excessive production of reactive oxygen species | Excess toxicity: Itai-itai disease (spinal and leg bone pain) caused by Cd accumulation in the liver and kidneys resulting in tubular renal dysfunction, osteoporosis, cancer, and cardiovascular diseases |

| Fe | Demand: Proteins involved in redox and electron transport. Leaf pigment formation; Toxicity: Free Fe can generate toxic levels of oxygen and hydroxyl free radicals through the Fenton reaction | Deficiency: Anemia, impaired mental development; Iron overload: Excessive accumulation of Fe in the liver, heart, and pancreas. Hemosiderosis; Hemochromatosis |

Zinc and Fe in the grains of cereals such as rice are essential elements for humans. However, humans’ intake of Zn and Fe is generally not sufficient [3,6,7]. In contrast, Cd, which is sometimes contained at high levels in the rice grains grown in Cd-contaminated soils, is toxic for humans [8]. Therefore, it is necessary to enrich rice grains with Zn and Fe and to decrease their Cd content [9].

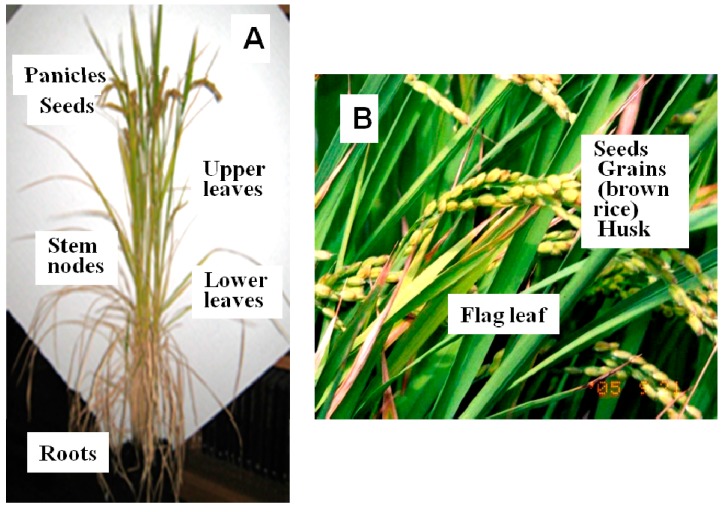

Fukushima et al. [8] reported that, in the district where “Itai-Itai disease” was endemic, soil Cd levels ranged from 0.4 to 8 mg·kg−1 (dry soil) and those of brown rice were correlated, varying between 0.2 to 2 mg·kg−1 (dry weight), while in the case of Zn levels, although soil Zn levels varied greatly from 50 to 1200 mg·kg−1, those of brown rice had a much smaller range from 20 to 30 mg·kg−1. (Names of rice plant parts are shown in Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Rice plants (cv. Koshihikari) grown in potted soil (A) and in a field (B) at maturity.

Recent field studies in Thailand by Simmons et al. [10] on Cd, Zn, and Fe accumulation in rice grains (unpolished rice) under Cd/Zn contaminated soils, containing 2.9‒284 mg·kg−1 Cd, 254‒8036 mg·kg−1 Zn, and 0.5‒25 mg·kg−1 Fe, indicated that the harvested grains contained variable concentrations of Cd ranging from 0.02 to 5.0 mg·kg−1, but relatively constant concentrations of Zn (from 15 to 25 mg·kg−1) and Fe (from 7.5 to 12.7 mg·kg−1), although the concentrations of all three metals varied greatly in the stems and leaves. Thus, Zn and Fe levels in rice grains are little affected by the availability of Zn and Fe in the soil, while grain Cd levels vary greatly. Grain Zn concentrations in rice plants grown in the Philippines were unchanged by Zn fertilization (15 kg Zn·ha−1), while this Zn fertilization increased straw Zn concentrations by 43%‒95% [11].

When a rice cultivar (Todorokiwase) was grown in a culture solution at 0.01 to 3.0 mg·L−1 Cd, the Cd concentrations in the leaf blades greatly increased from 3 to 100 mg·kg−1 and those in the grains also increased from 0.5 to 10 mg·kg−1[12]. In contrast, when Zn concentrations in the culture solution were increased from 0.05 to 20 mg·L−1, Zn concentrations in the leaf blades greatly increased from 50 to 2500 mg·kg−1, but those in the grains increased only slightly from 33 to 80 mg·kg−1[13]. Recently, Jiang et al. [14] reported that when a rice cultivar (Handao297) grown in a nutrient solution containing Zn at 0.15 to 2250 µM, Zn concentrations in the shoots greatly changed from 53 to 1540 mg·kg−1, while those in brown rice changed only slightly from 52 to 106 mg·kg−1.

These results suggest that specific regulatory mechanisms for each of the three metals may exist between the xylem delivery to stems and leaves and the allocation of the metals to grains. In this review, to determine the regulation of the transport on Zn, Cd, and Fe via the xylem and phloem, we synthesized information of Zn, Cd, and Fe concentrations and their chemical forms in xylem and phloem saps, the localizations of metal transporters, and finally the routes of transport of these metals to the grains.

2. Uptake at Root-Surface Membranes and Radial Transport to the Xylem

Plant availability of metals from soils is controlled by three steps: (1) soil conditions (upland or flooded soil, soil solution pH); (2) mineralization (ionization and complex formation); and (3) uptake transporters.

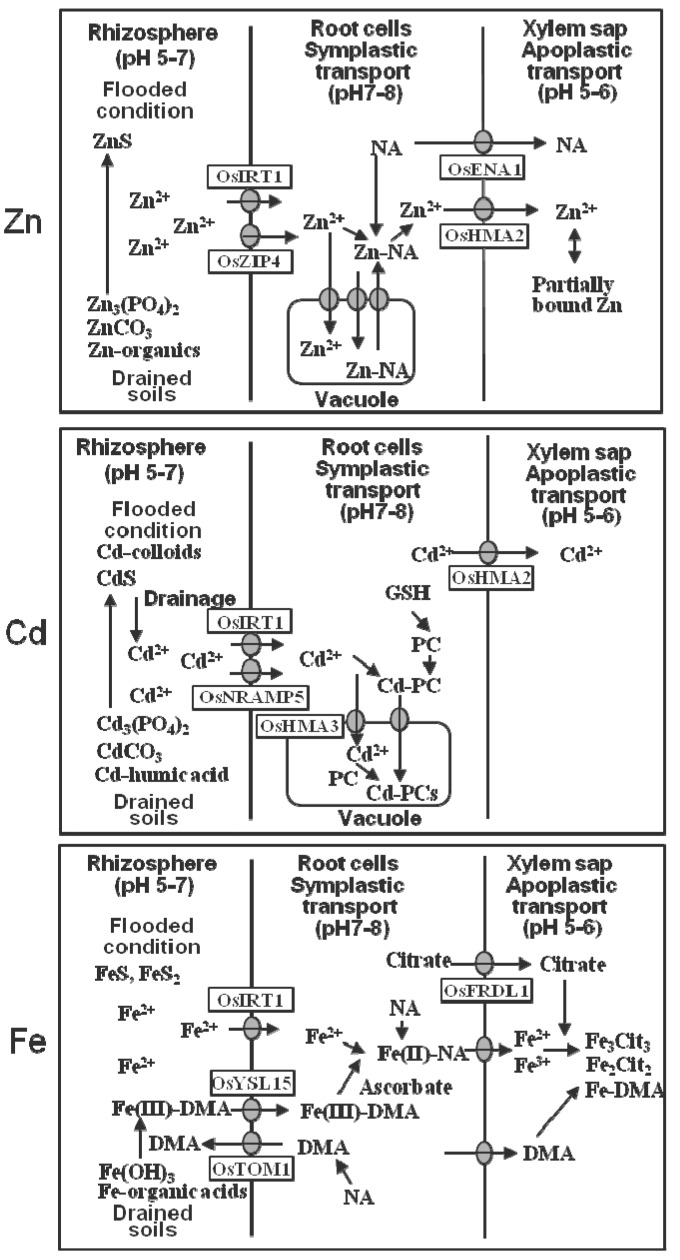

As shown in Figure 2, Zn in both drained and flooded soils is largely ions (Zn2+), although some Zn may be bound to organic substances, and immobilized as Zn–sulfide (ZnS) in the anaerobic layer [15]. Cadmium in drained acidic soils is ionized as Cd2+, while Cd in paddy alkaline soils is present in the forms of CdCO3 and humic acid-bound Cd [16]. Cd is immobilized as Cd-sulfide (CdS) and colloids-bound Cd by flooding of soils [17]. Drainage converts CdS to Cd2+ and dramatically increases its availability to plants. Fe in acidic soils is ionized as Fe2+/Fe3+, while in aerobic alkaline soils Fe is immobilized as Fe(OH)3.

Figure 2.

Models of uptake and transport of Zn, Cd, and Fe in rice roots. DMA, 2′-deoxymugineic acid; GSH, glutathione; NA, nicotianamine; PC, phytochelatin. Arrows indicate flows of substances and grey ellipses indicates transporters.

As shown in Table 2, the uptake of these metals at root-surface membranes is driven by specific uptake transporters, Zn2+, Cd2+, and Fe2+ commonly by OsIRT1 (rice iron-regulated transporter1) [18,21,23] and Cd2+ predominantly by OsNRAMP5 (rice natural resistance-associated macrophage protein5) [19]. The possible uptake of some Zn–phytosiderophores together with the uptake of Zn2+ by a Zn-deficiency-tolerant line of rice has been suggested under lowland conditions [32]. Iron (Fe3+) in neutral and alkaline soils binds to mineral crystals and organic substances so strongly that such soil ions are barely available to plants and the iron is solubilized by forming a complex with a phytosiderophore, 2′-deoxymugineic acid (DMA) [33], which is excreted by rice roots by OsTOM1 (rice DMA effluxer) [34]. Fe(III)–DMA complexes in the soil solution are taken up by OsYSL15 (rice yellow stripe-like15) [22]. Under flooded conditions, rice plants may absorb both Fe(III)–DMA and Fe2+ [23].

Table 2.

Transporters involved in the acquisition and inter-organ transport of Zn, Cd, and Fe in rice plants.

| Site | Zn | Cd | Fe |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acquisition at root cell membranes | OsIRT1 1; OsZIP4,5 2 | OsNRAMP5 3; OsIRT1/OsIRT2 4 | OsYSL15 5; OsIRT1/OsIRT2 6 |

| Vacuolar import through the tonoplast in root cells | (ZIF1) 7 | OsHMA3 8 | |

| Xylem loading at root pericycle cells | OsHMA2 9 | OsHMA2 5,9 | |

| Xylem-to-phloem transport at nodes | OsHMA2 10 | OsHMA2 10 | OsYSL16 11 |

| Phloem loading after mobilization in leaves | ZIP and YSL families | OYSL15 12 | |

| Phloem unloading at reproductive organs | OsYSL18 13 |

1 Lee and An [18]; 2 White and Broadley [4]; 3 Ishikawa et al. [19], Sasaki et al. [20]; 4 Nakanishi et al. [21]; 5 Inoue et al. [22]; 6 Ishimaru et al. [23]; 7 Haydon et al. [24]; 8 Ueno et al. [25]; 9 Nocito et al. [26], Takahashi et al. [27]; 10 Yamaji et al. [28]; 11 Kakei et al. [29]; 12 Lee et al. [30]; 13 Aoyama et al. [31].

Zinc (Zn2+) and Fe2+ in root cell cytosols form complexes with nicotianamine (NA) in the forms of Zn–NA and Fe(II)–NA (Figure 2). Cadmium in the root cell cytosols may be Cd2+ ions or complexes with phytochelatins (PCs). Fe(III)–DMA absorbed in the root cell cytosols can be reduced by ascorbate, transforming to Fe(II)-NA [35]. Fe of cytosolic Fe(II)–NA may be excreted to the xylem and makes complexes predominantly with citrate (Fe2Cit2, Fe3Cit3) and some with DMA (Fe–DMA) [36].

Root cell vacuoles can function as a storage compartment for metals. Zn–NA in the root cell cytosols is transferred to the vacuoles by the ZIF1 (zinc induced facilitor1) transporter [24]. Cadmium in the cell cytosols may be partly sequestered through the tonoplast as Cd2+ by OsHMA3 (rice heavy metal ATPase3) [25] and as Cd-PC complex, presumably by ABCC-type transporters in Arabidopsis [37], and both are stored as Cd-PCs in the vacuoles. Enhancement of OsHMA3 activity has been found to increase storage in roots and decrease the transport of Cd to the shoot and the final accumulation of Cd in rice grains [25]. A high rate of root-to-shoot transport and subsequent accumulation in the grains of 107Cd, which was administered from a culture solution, was observed in OsHMA3-depleted rice lines [38].

OsHMA2, which localizes at the root pericycle, is a major transporter of Zn and Cd for xylem loading [26,27]. The excretion of citrate from the root cells to the xylem is partly operated by OsFRDL1 (rice ferric reductase defective1-like) to enhance Fe-transport in the xylem as Fe(III)–citrate complex [39].

3. Xylem and Phloem Transport

The concentrations of Zn, Cd, and Fe and their chemical forms in rice xylem and phloem saps from 28- to 33-day-old vegetative plants were analyzed. The phloem sap was collected by a unique and excellent technique using the insect-laser method as described by Kawabe et al. [40]. Briefly, the insects used were Nilaparvata lugens Stål (brown planthopper). Rice plants at the 8th to 9th leaf-age were transferred to 500 mL plastic bottles, one plant per bottle, and placed in an artificially lit chamber (130 µmol·m−2·s−1 photosynthetically active irradiation, 12 h light and 12 h dark cycle). After the plants’ adaptation to the environment over 1 or 2 days, overhead projector film sheet cylinders (3 cm high, 1 cm in diameter) with cotton stoppers on both sides were set on the sheaths of the fully developed leaves, and female insects, that had been forced to fast overnight, were transferred into the cylinders to allow the insects to suck the phloem sap. After 1–3 h, the insects’ stylets were cut by a YAG laser (SL129Nd; NEC, Tokyo, Japan) beam. After the phloem sap was collected, shoots were cut with a knife at 2 cm from the root-shoot interface and the exudates (xylem sap) from the cut surfaces were collected.

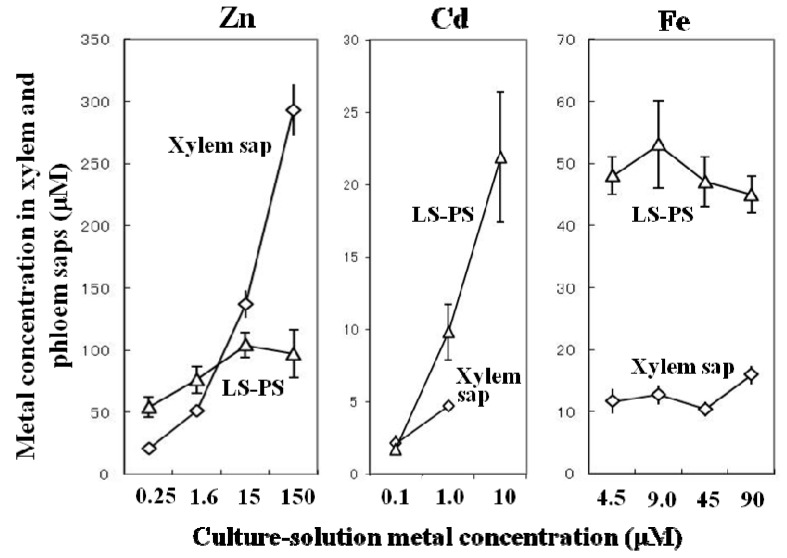

The Zn concentrations in the xylem and phloem saps under four different Zn concentrations in the culture solution are shown in Figure 3. The Zn concentrations in the xylem sap increased with those in the culture solution, while the Zn concentrations in the phloem sap varied only slightly between 55 and 100 μM. With 0.1 µM culture-solution Cd, the xylem and phloem Cd concentrations were around 20-fold higher than the culture-solution Cd concentrations. Under treatment with 10 µM Cd, xylem sap was not exuded due to wilting. Cd concentrations in the collected phloem sap increased with the medium Cd concentrations (Figure 3). Although the Fe concentrations in the culture solution ranged greatly at 4.5, 9.0, 45 and 90 µM, xylem Fe concentrations remained nearly constant at 12 µM under the lower three culture-solution Fe treatments and 16 µM under the 90 µM treatment (Figure 3). Phloem-sap Fe concentrations, around 50 µM Fe, were not affected by the different Fe treatments.

Figure 3.

Metal concentrations in the xylem and phloem saps of vegetative rice plants under various culture-solution metal concentrations. Phloem sap was collected from the leaf sheaths (LS-PS) of the 7th leaves. Data for Zn and Fe are from Nishiyama [41], and data for Cd are from Mariyo Kato [42].

The chemical forms in xylem and phloem saps from young rice plants are shown in Table 3. Using the phloem and xylem saps collected as described above, chemical forms (speciation) of Zn, Cd, and Fe in such saps were investigated using size-exclusion high performance liquid chromatography (SE-HPLC, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan), inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (ICP-MS, Yokogawa, Tokyo, Japan), capillary electrophoresis coupled to mass spectrometry (CE-MS, Agilent Technologies, Walbronn, Germany), and electrospray ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (ESI-TOF MS, JOC, Tokyo, Japan).

Table 3.

Chemical forms of Zn, Cd. Fe, and Cu in xylem and phloem saps from rice plants. Metal speciation analyses in xylem and phloem saps were conducted by using SE-HPLC, ICP-MS, CE-MS, and ESI-TOF MS.

| Metal | Chemical Forms in Xylem Sap (pH 6) | Chemical Forms in Phloem Sap (pH 8) |

|---|---|---|

| Zn | Free ions and partially bound 1 | Bound dominantly to NA 2 |

| Cd | Primarily in free ions 3 | Bound largely to specific proteins and slightly to thiol-compounds 4 |

| Fe | Bound largely to citrate (around 65%) and slightly to DMA (around 5%)and some in free ions 5 | Bound to DMA, citrate, and proteins 2 |

| Cu | Bound dominantly to DMA 6 | Bound to NA, histidine and proteins 6 |

The Zn chemical forms in xylem sap are free ions and Zn partially bound to unidentified chelators [39], while the Zn in phloem sap was dominantly bound to NA [43]. The Cd chemical form in the xylem sap is primarily in free ions (Mariyo Kato [42]), while the Cd in the phloem sap was largely bound to specific proteins although some Cd was bound to low-molecular thiol compounds [44]. The Fe chemical forms in xylem sap were found to be bound largely to citrate (around 65%) and slightly to DMA (around 5%) [36], while the Fe in phloem sap bound to DMA, citric acid, and proteins [43]. Recently, metal species in the xylem and phloem saps from various plants including rice were summarized by Álvarez-Fernández et al. [45].

Changes in copper (Cu) concentrations in xylem and phloem saps and the chemical forms of Cu in rice xylem and phloem saps were investigated by Ando et al. [46]. Xylem Cu concentrations were found to range slightly between 5 and 8 µM when culture-solution Cu concentrations ranged from 0.16 to 1.28 µM and the Cu in xylem sap was dominantly bound to DMA. Phloem sap Cu concentrations ranged between 21 and 43 µM and the Cu in phloem sap was bound to NA, histidine and proteins.

Based on the results on variation in metal concentrations (Figure 3) and their chemical forms in xylem and phloem saps (Table 3), the following interesting relationship regarding the regulatory mechanisms that underlie the different changes in the Zn, Cd, Fe, and Cu concentrations in both saps is suggested; if xylem sap contains substantial free metal ions as in the cases of Zn and Cd, its metal concentration increases with increasing culture-solution metal concentration, while if xylem sap contains metal–ligand complexes as in the cases of Fe and Cu, its metal concentration remains nearly constant. If the metals in the phloem saps are definitely bound to ligands as in the cases of Zn–NA, Fe–DMA, and Cu–NA, the metal concentration remains quite constant. The concentration of NA, which may bind Zn and Cu in rice phloem sap, was around 70 µM [43,45], and that of DMA, which may bind Fe in rice phloem sap, was around 150 µM [43]. However, phloem Cd is apparently an exception; phloem concentrations changed with culture-solution and xylem-sap Cd concentrations (Figure 3). The major form of Cd in the phloem saps is protein-bound and the Cd-binding capacity of the proteins may be sufficient to load all Cd in the phloem sap [44].

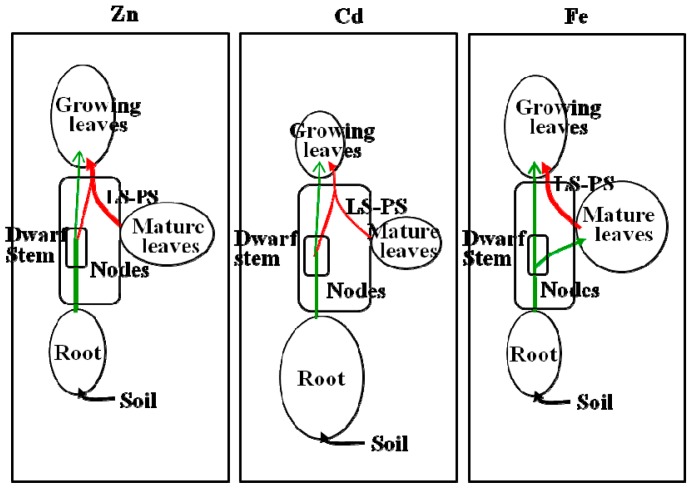

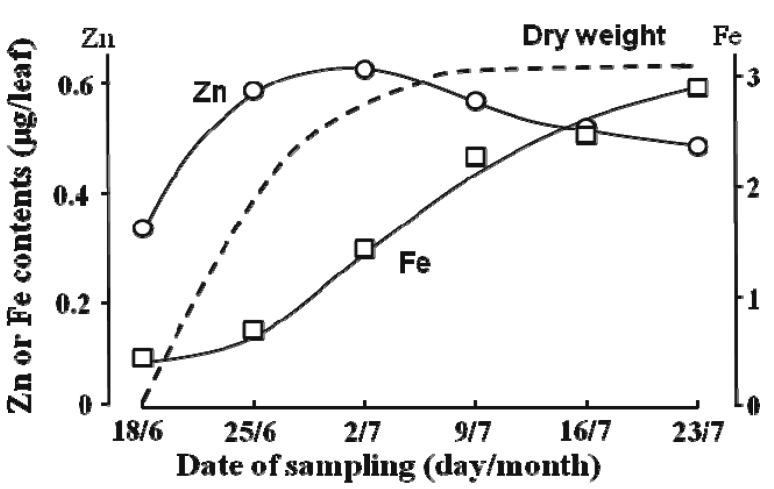

With respect to the transport of Zn in xylem sap to rapidly growing leaves, Obata and Kitagishi [47] indicate that some Zn ascending via the xylem (transpiration stream) is transferred to the phloem at the vegetative nodes in addition to the Zn which is mobilized from mature leaves (Figure 4). Together this Zn with different origins is terminated to the intercalary meristem to synthesize ribosomes [48]. Such active transport through both routes supports the high Zn accumulation at the meristem, which has been reported to reach 300 mg Zn·kg−1 dry weight (DW) in the rapidly growing leaf part as compared to 30 mg Zn·kg−1 DW in the mature leaves [49]. Figure 5 shows this unique and quick accumulation of Zn in the early stage of leaves compared to the slow accumulation of Fe and also the early initiation of the decrease after the peak of Zn content, which was one week before reaching the DW peak [49]. The amount of Zn transferred to the phloem via the xylem-to-phloem transfer system seems to be regulated and constant: the transfer rate of Zn from xylem sap is relatively high when the xylem sap Zn concentration is low, and low when the xylem sap Zn concentration is high [50]. The ratio of the Zn deprived by the xylem-to-phloem transfer to that remobilized from the leaves is estimated to be around 3:7 [49]. Partitioning of Cd to the top may be similar to that of Zn and the vegetative nodes may also be the site of the xylem-to-phloem transfer of Cd [51]. 115mCd absorbed by roots is partitioned to the dwarf stem and leaves by the pattern of accumulation in the nodal part of the stem, and transport is then predominant to the rapidly growing leaves with little to the mature leaves [52], similar to that of 65Zn [50]. Recently, preferential movement of 109Cd and 45Ca, which were administered to a root–bathing solution as 109CdCl2 and 45CaCl2, to the newest leaf by transfer to the phloem at the stem, was confirmed by radioisotope imaging [53]. The rate of Fe involved in xylem-to-phloem transfer could be smaller than that of Zn, since the demand-time of Fe is late compared to that of Zn (Figure 5, [49]). It is interesting to note that Fe in rice xylem sap has been found to contain small amounts of Fe–DMA and large amounts of Fe–citrate while the Fe in the xylem sap of barley plants includes a considerable fraction of Fe–mugineic acid (MA) [36]. Barley plants can transfer such xylem sap Fe–MA to the young leaves through the xylem-to-phloem system at nodes as revealed by 52Fe tracing [54].

Figure 4.

Models of the transport of Zn, Cd, and Fe via xylem and phloem in rice plants at the vegetative stage. “Leaves” are leaf blades. “Stem” includes the dwarf culm and leaf sheaths. The green line shows xylem transport. The red line shows phloem transport. Phloem sap was collected from the leaf sheaths (LS-PS). Information is from Yoneyama et al. [55]. Important note: At the vegetative nodes of the dwarf stem, Zn and Cd ascending xylem (green line) are transferred to the phloem (red line) via the xylem-to-phloem transfer system at the nodes, while Fe in the xylem (in the form of Fe–citrate) does not pass through this system.

Figure 5.

Changes in Zn and Fe amounts in the blade of the 10th leaf along with dry weight growth. (Adapted from Obata and Kitagishi [49]). The dry weight of the leaf was drawn arbitrarily as the dry weight at 23/7 had reached the maximum. ○: change in the content of Zn; □: change in the content of Fe. (Adapted from Obata and Kitagishi [49]).

Xylem transfer cells found in vegetative nodes [56,57,58] and localized metal transporters (Table 2) may support the active xylem-to-phloem transfer of xylem sap Zn and Cd.

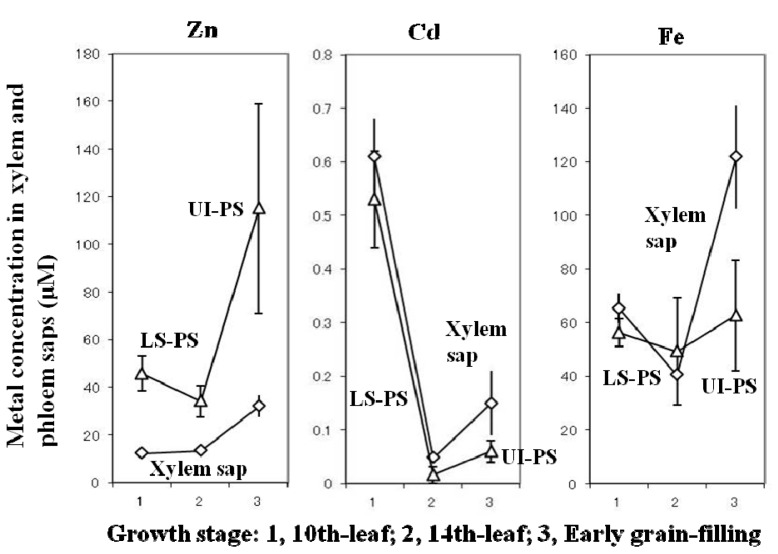

4. Accumulation of Zn, Cd, and Fe in Rice Grains

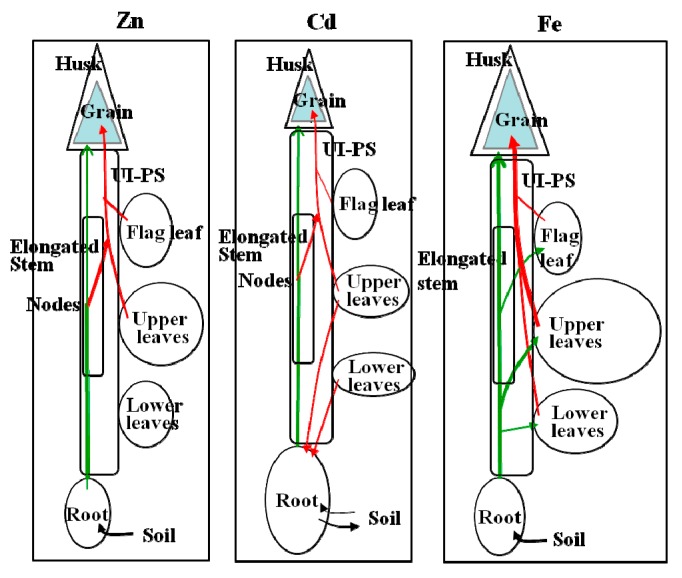

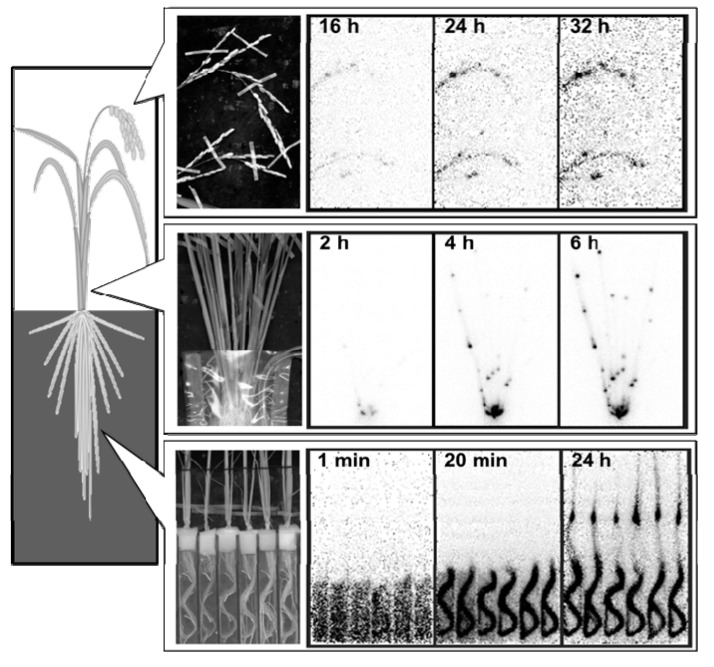

Phloem and xylem saps were collected from rice plants grown in Cd-contaminated flooded soil. Phloem sap was obtained from leaf sheaths at the 10th and 14th leaf ages and from the uppermost internodes at the grain-filling stage (Figure 6 [55]). Phloem loading after both remobilization from the leaves and stems and xylem-to-phloem transfer at stem and panicle nodes of the currently ascending fluids may be the source of grain Zn [55,59,60] and Cd [55,61,62], but for Fe the route of remobilization from other organs may be dominant as shown in Figure 7. The contribution of the xylem-to-phloem transfer rate of Zn and probably also of Cd is evident from the high and increased Zn concentration in phloem sap collected at the uppermost internode as compared to that collected from leaf sheaths at the 14th-leaf stage; in contrast, no such increase was observed for Fe (Figure 6). A positron-emitting 107Cd imaging study of hydroponically grown rice plants at the panicle-initiation stage suggests the highly preferential transport of currently absorbed Cd to the panicles through the presumed xylem-to-phloem transfer at the nodes (Figure 8) [63]. The presence of xylem transfer cells in the nodes [56] and in the spikelet nodes at the region of the rachilla and pedicle [64,65] and metal transporters, OsHMA2 for Zn and Cd [28] and OsYSL16 (rice yellow stripe-like16) for Fe–DMA [29] although the fraction of Fe–DNA is small [36], may be involved in the active xylem-to-phloem transfer of minerals (at the nodes) currently ascending via the xylem from the roots. The amount of transfer of Zn via the xylem-to-phloem system may be highly regulated at a certain level where there is a large supply of Zn through the xylem, as shown in wheat detached panicles [66]. In contrast, such a restriction may not work in the transport of Cd, since the Cd concentration ascending the xylem is much smaller than that of Zn. Jiang et al. [67] demonstrated the efficient transport to the grains and little partitioning to the leaves of 65Zn applied to rice plants from a culture solution during the flowering period. Rodda et al. [62] estimated that 60% of the final grain Cd could be attributed to remobilization from other tissues and the rest (40%) from uptake during grain maturation. Importantly, mineral transporters for xylem-to-phloem transport at the nodes (OsHMA2, OsYSL16), for the phloem loading at leaves (OsYSL15), and for unloading at panicles (OsYSL18) may play important functions in the regulation of metal transport (Table 2).

Figure 6.

Metal concentrations in the xylem and phloem saps obtained from rice plants grown in a flooded Cd-contaminated soil. Phloem sap was collected from the leaf sheaths (LS-PS) of the 9th leaves at 10th-leaf stage and the 13th leaves at 14th-leaf stage, and from the uppermost internodes (UI-PS) at early grain-filling. Data are from Yoneyama et al. [55]. ◊: metal concentrations in the xylem sap, Δ: metal concentrations in the phloem sap.

Figure 7.

Models of the transport of Zn, Cd, and Fe via xylem and phloem in rice plants at grain filling. “Leaves” are Leaf blades. “Stem” includes elongated culm, leaf sheaths, and panicles except husk and grain. Green line shows xylem transport. Red line shows phloem transport. Phloem sap was collected from the uppermost internode (UI-PS). Information is from Yoneyama et al. [55]. Important note: At the nodes in the elongated stem, Zn and Cd ascending xylem (green line) are transferred to phloem (red line) via the xylem-to-phloem transfer system, while Fe in the xylem (in the form of Fe–citrate) does not pass through this system.

Figure 8.

Movement of 107Cd in rice plants administered from the root–bathing solution visualized with a positron-emitting tracer imaging system (PETIS). Regenerated from the original data of Ishikawa et al. [38] and Fujimaki et al. [62]. Important note: The images show the uptake and accumulation of 107Cd by roots, transport to the shoots accompanying accumulation at the nodes (probably occurring during xylem-to-phloem transport), and final destination in the grains.

The deposition of metals in grains is revealed as metal partitioning: Zn and Fe, which combine with phytic acid, are largely accumulated in the aleurone cell layer [4,68] but their concentrations are reduced in white rice by polishing, while a large proportion of Cd is localized at the storage protein (glutelin) in the endosperm [69] and the Cd concentration in white rice is unchanged by polishing.

As stated in the Introduction section above, the Zn concentration in rice grains is affected only slightly by the availability of culture-solution metals, as compared to the great changes in Zn concentrations in the leaves and stems [13,14]; grain Cd concentrations are easily affected [12]. This observation is strongly related to the regulated and small changes in phloem concentrations of Zn, which may be in the form of Zn–NA complexes. In contrast, Cd loaded into phloem fluids may quickly bind to specific Cd-binding proteins, and those are unsaturated with Cd and sufficiently present relative to Cd, as described by Kato et al. [44]. Therefore, there are fewer limitations in the phloem transport of Cd than in Zn phloem transport.

The Fe in phloem sap may be derived largely from remobilization at the leaves (Figure 7, [55]) and probably bind to DMA and some citrate and proteins [43]. Therefore, the amount of Fe transport to the grains may be regulated by ligands and chelators. Schuler et al. [70] reported that in Arabidopsis thaliana, Fe–citrate in xylem sap may be delivered to the mature leaves and then Fe may be carried to the reproductive organs via the phloem as Fe–NA from the mature leaves. In the case of rice plants, Fe in the xylem is largely bound to citrate with slight binding to DMA [36]. Therefore, a large fraction of xylem Fe may be delivered first to the leaves as Fe–citrate and then to the seeds via the phloem, probably as Fe–DMA. It is possible that small amounts of Fe–DMA in rice xylem sap [36] travel through the xylem-to-phloem transport system at nodes by the OsYSL16 transporter [29]. Foliar application of a solution containing NA in addition to Fe and amino acids to a field-grown rice plant was found to increase the Fe and Zn concentrations in brown rice over those under a treatment with a solution containing Fe and amino acids [71].

5. Molecular Technologies to Increase Grain Fe and Zn and to Reduce Grain Cd

Recent attempts at the biofortification of Fe and Zn in rice grains using transgenic techniques have produced interesting results. The introduction of a yeast ferric chelate reductase gene to rice plants induced the enhancement of Fe uptake and an increase in grain yields but had no effect on Fe and Zn concentrations in the grains [72]. In contrast, the over-expression of the barley NA synthase gene HvNAS1 in rice plants caused an increase in DMA and NA concentrations in roots, shoots, and seeds as well as of Fe, Zn, and Cu concentrations in grains [73]. These results are consistent with the proposed principle that the phloem-sap and grain concentrations of metals may be regulated by making use of the nature of metal-chelating compounds. It is valuable to note that high-NA grain may increase iron-bioavailability to mammals and humans [74,75].

There are three possible ways to reduce Cd content in rice grains: (1) the selection of lines/varieties with low Cd in phloem sap [44]; (2) more sequestration of Cd in the root–cell vacuoles by overexpression of OsHMA3 [25]; and (3) elimination of a Cd-uptake transporter (OsNRAMP5) in the root membranes [19]. Ishikawa et al. [19] report that carbon ion beam irradiation produced Cd-deficient rice mutants (Koshihikari-Kan1) with <0.05 mg Cd·kg−1 in the grains compared with a mean of 1.1 mg Cd·kg−1 in the parent, cultivar Koshihikari (a high eating-quality rice) when plants were grown in Cd-contaminated fields, whereas their Zn and Fe concentrations were less affected (Table 4), and they also developed DNA markers to select cultivars carrying osnramp5. In terms of human intake of Cd from Cd-contaminated foods such as rice, its bioavailability and retention in the liver and kidneys are dramatically increased due to the deficiency of Zn, Fe, and Ca in foods [76]. Therefore, biofortification of Zn, Fe and Ca in the grains is highly essential to reduce human Cd intake.

Table 4.

Concentrations of Zn, Cd and Fe of grains of cultivar Koshihikari (Koshi) and its OsNRAMP5-depleted mutant Koshihikari-Kan1 (Kan1) grown on three Cd-contaminated soils whose irrigation was treated with prolonged drainage after the early-period flooding. Data are means of 5 samples. ND, not detected. Data are from Ishikawa et al. [19].

| Field (Soil Cd mg·kg−1) | Grain Zn (mg·kg−1) | Grain Cd (mg·kg−1) | Grain Fe (mg·kg−1) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Koshi | Kan1 | Koshi | Kan1 | Koshi | Kan1 | |

| A (1.35) | 48.8 | 36.9 | 0.57 | ND | 21.5 | 16.4 |

| B (1.21) | 34.4 | 31.4 | 1.86 | 0.02 | 14.2 | 15.8 |

| C (0.35) | 50.4 | 37.5 | 0.97 | 0.03 | 15.1 | 14.3 |

6. Conclusions

Zn and Fe are essential nutrients for both plants and humans but Cd is non-essential and toxic if it accumulates at high levels for plants and, more severely, for humans. All three metals are contained in the grains of rice, a staple cereal worldwide. Several studies have reported that Zn and Fe concentrations in rice grains harvested under different levels of soil or hydroponic metals are known to change only within a small range, while grain Cd concentrations show greater changes and easily reach the allowable maximum in polished rice (0.4 mg·kg−1) [77]. To gain insight into the mechanisms underlying such different metal contents, we synthesized information about the routes of metal transport and accumulation in rice plants, finding novel regulations involving metal speciation in xylem and phloem saps, metal transporters, and the xylem-to-phloem transport system. Specific metal transporters are involved in uptake in the roots, delivery to the shoots via the xylem-to-phloem transport system, and final transport to the grains via the phloem. Xylem sap Zn is in free ions and partially bound to unidentified chelators and has a highly variable concentration, while phloem sap Zn is dominantly Zn–NA complex with a highly regulated concentration. Xylem sap Cd is primarily in free ions with a variable concentration, while phloem sap Cd is bound to proteins and thiol compounds, and its concentration is dependent on xylem sap Cd. Cd loaded into phloem fluids may quickly bind to specific Cd-binding proteins, those are unsaturated with Cd and sufficiently present relative to Cd. Xylem sap Fe (largely as Fe–citrate) is allocated to all leaves, while phloem Fe is bound to DMA, citrate, and proteins. At grain-filling, Zn and Cd ascending in xylem sap are transferred to the phloem by the xylem-to-phloem transport system operating at stem and panicle nodes, where xylem transfer cells and specific metal transporters are recognized. Grain Fe is largely derived from the leaves by remobilization. Thus, the concentrations of grain Zn and Fe are highly regulated within a small range, while that of grain Cd varies depending on xylem supply. Transgenic techniques to increase tissue and phloem-sap concentrations of NA and DMA are useful to increase grain Zn and Fe concentrations. The elimination of OsNRAMP5 Cd-uptake transporter and the enhancement of root cell vacuolar Cd sequestration reduce uptake and root–to-shoot transport, respectively, resulting in a great reduction of Cd accumulation in grains.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Reiko Nishiyama for her kind supply of information of Zn and Fe concentrations in rice xylem and phloem saps from her Master’s thesis [39] and Mariyo Kato for providing her unpublished data of Cd concentrations in xylem and phloem saps as shown in Figure 3.

Author Contributions

Tadakatsu Yoneyama wrote the first draft of the manuscript and organized the tables and figures; Satoru Ishikawa and Shu Fujimaki reviewed the manuscript and added Table 4 and Figure 8, respectively.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Nouet C., Motte P., Hanikenne M. Chloroplastic and mitochondrial metal homeostasis. Trends Plant Sci. 2011;16:395–404. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palmer C.M., Guerinot M.L. Facing the challenges of Cu, Fe and Zn homeostasis in plants. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2009;5:333–340. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palmgren M.G., Clemens S., Williams L.E., Krämer U., Borg S., Schjørring J.K., Sanders D. Zinc biofortification of cereals: Problems and solutions. Trends Plant Sci. 2008;13:464–473. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.White P.J., Broadley M.R. Physiological limits to zinc biofortification of edible crops. Front. Plant Sci. 2011;2:80. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2011.00080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clemens S., Aarts M.G.M., Thomine S., Verbruggen N. Plant science: The key to preventing slow cadmium poisoning. Trends Plant Sci. 2012;18:92–99. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zimmermann M.B., Hurrell R.F. Improving iron, zinc, vitamin A nutrition through plant biotechnology. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2002;13:142–145. doi: 10.1016/S0958-1669(02)00304-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dijkhuizen M.A., Wieringa F.T., West C.E. Zinc plus β-carotene supplementation of pregnant women is superior to β-carotene supplementation alone in improving vitamin A status in both mothers and infants. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004;80:1299–1307. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.5.1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fukushima M., Ishizaki A., Sakamoto M., Kobayashi E. Cadmium concentration in rice eaten by famers in the Jinzu River Basin. Jpn. J. Hyg. 1973;28:406–415. doi: 10.1265/jjh.28.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khoshgoftarmanesh A.H., Schulin R., Chaney R.L., Daneshbakhsh B., Afyuni M. Micronutrient-efficient genotypes for crop yield and nutritional quality in sustainable agriculture. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2010;30:83–107. doi: 10.1051/agro/2009017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simmons R.W., Pongsakul P., Chaney R.L., Saiyasitpanich D., Klinphoklap S., Nobuntou W. The relative exclusion of zinc and iron from rice grain in relation to rice grain cadmium as compared to soybean: Implications for human health. Plant Soil. 2003;257:163–170. doi: 10.1023/A:1026242811667. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wissuwa M., Ismail A.M., Graham R.D. Rice grain zinc concentrations as affected by genotype, native soil-zinc availability, and zinc fertilization. Plant Soil. 2008;306:37–48. doi: 10.1007/s11104-007-9368-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ito H., Iimura K. Absorption of zinc and cadmium by rice plants and their influence on its growth. II. Effect of cadmium. Jpn. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 1976;47:44–48. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ito H., Iimura K. Absorption of zinc and cadmium by rice plants and their influence on its growth. I. Effect of zinc. Jpn. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 1976;47:39–43. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang W., Struik P.C., van Keulen H., Zhao M., Jin L.N., Stomph T.J. Does increased zinc uptake enhance grain zinc mass concentration in rice? Ann. Appl. Biol. 2008;153:135–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7348.2008.00243.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shiratori K., Suzuki T., Miyoshi H. Chemical forms of soil zinc in the salt-rich reclaimed fields, where zinc-deficiency symptoms were observed in rice plants. Jpn. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 1972;43:291–296. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khaokaew S., Chaney R.L., Landrot G., Ginder-Vogel M., Sparks D.L. Speciation and release kinetics of cadmium in an alkaline paddy soil under various flooding periods and draining conditions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011;45:4249–4255. doi: 10.1021/es103971y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hashimoto Y., Yamaguchi N. Chemical speciation of cadmium and sulfur K-edge XANES spectroscopy in flooded paddy soils amended with zerovalent iron. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2013;77:1189–1198. doi: 10.2136/sssaj2013.01.0038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee S., An G. Over-expression of OsIRT1 leads to iron and zinc accumulations in rice. Plant Cell Environ. 2009;32:408–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.01935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ishikawa S., Ishimaru Y., Igura M., Kuramata M., Abe T., Senoura T., Hase Y., Arao T., Nishizawa N.K., Nakanishi H. Ion-beam irradiation, gene identification, and marker-assisted breeding in the development of low-cadmium rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:19166–19171. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211132109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sasaki A., Yamaji N., Yokosho K., Ma J.F. Nramp5 is a major transporter responsible for manganese and cadmium uptake in rice. Plant Cell. 2012;24:2155–2167. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.096925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakanishi H., Ogawa I., Ishimaru Y., Mori S., Nishizawa N.K. Iron deficiency enhances cadmium uptake and translocation mediated by the Fe2+ transporters OsIRT1 and OsIRT2 in rice. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2006;52:464–469. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0765.2006.00055.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Inoue H., Kobayashi T., Nozoye T., Takahashi M., Kakei Y., Suzuki K., Nakazono M., Nakanishi H., Mori S., Nishizawa N.K. Rice OsYSL15 is an iron-regulated iron(III)-deoxymugineic acid transporter expressed in the roots and is essential for iron uptake in early growth of the seedlings. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:3470–3479. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806042200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ishimaru Y., Suzuki M., Tsukamoto T., Suzuki K., Nakazono M., Kobayashi T., Wada Y., Watanabe S., Matsuhashi S., Takahashi M., et al. Rice plants take up iron as an Fe3+-phytosiderophore and as Fe2+ Plant J. 2006;45:335–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haydon M.J., Kawachi M., Wirtz M., Hillmer S., Hell R., Krämer U. Vacuolar nicotianamine has critical and distinct roles under iron deficiency and for zinc sequestration in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2012;24:724–737. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.095042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ueno D., Yamaji N., Kono I., Huang C.F., Ando T., Yano M., Ma J.F. Gene limiting cadmium accumulation in rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:16500–16505. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005396107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nocito F.F., Lancilli C., Dendena B., Lucchini G., Sacchi G.A. Cadmium retention in rice roots is influenced by cadmium availability, chelation and translocation. Plant Cell Environ. 2011;34:994–1008. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2011.02299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takahashi R., Ishimaru Y., Shimo H., Ogo Y., Senoura T., Nishizawa N.K., Nakanishi H. The OsHMA2 transporter is involved in root–to-shoot translocation of Zn and Cd in rice. Plant Cell Environ. 2012;35:1948–1957. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2012.02527.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamaji N., Xia J., Mitani-Ueno N., Yokosho K., Ma J.F. Preferential delivery of zinc to developing tissues in rice is mediated by P-type heavy metal ATPase OsHMA2. Plant Physiol. 2013;162:927–939. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.216564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kakei Y., Ishimaru Y., Kobayashi T., Yamakawa T., Nakanshi H., Nishizawa N.K. OsYSL16 plays a role in the allocation of iron. Plant Mol. Biol. 2012;79:583–594. doi: 10.1007/s11103-012-9930-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee S., Chiecko J.C., Kim S.A., Walker E.L., Lee Y., Guerinot M.L., An G. Disruption of OsYSL15 leads to inefficiency in rice plants. Plant Physiol. 2009;150:786–800. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.135418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aoyama T., Kobayashi T., Takahashi M., Nagasaka S., Usuda K., Kakei Y., Ishimaru Y., Nakanishi H., Mori S., Nishizawa N.K. OsYSL18 is a rice iron(III)-deoxymugineic acid transporter specifically expressed in reproductive organs and phloem of lamina joints. Plant Mol. Biol. 2009;70:681–692. doi: 10.1007/s11103-009-9500-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Widodo, Broadley M.R., Rose T., Frei M., Pariasca-Tanaka J., Yoshihashi T., Thomson M., Hammond J.P., Aprile A., Close T.J., et al. Response to zinc deficiency of two rice lines with contrasting tolerance is determined by root growth maintenance and organic acid exudation rate, and not by zinc-transport activity. New Phytol. 2010;186:400–414. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.03177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takagi S., Nomoto K., Takemoto S. Physiological aspect of mugineic acid, a possible phytosiderophore of graminaceous plants. J. Plant Nutr. 1984;7:469–477. doi: 10.1080/01904168409363213. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nozoye T., Nagasaka S., Kobayashi T., Takahashi M., Sato Y., Uozumi N., Nakanishi H., Nishizawa N.K. Phytosiderophore efflux transporters are crucial for iron acquisition in graminaceous plants. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:5446–5454. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.180026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weber G., von Wiren N., Hayen H. Investigation of ascorbate-mediated iron release from ferric phytosiderophores in the presence of nicotianamine. Biometals. 2008;21:503–513. doi: 10.1007/s10534-008-9137-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ariga T., Hazama K., Yanagisawa S., Yoneyama T. Chemical forms of iron in xylem sap from graminaceous and non-graminaceous plants. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2014;60:460–469. doi: 10.1080/00380768.2014.922406. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Park J., Song W.-Y., Ko D., Eom Y., Hansen T.H., Schiller M., Lee T.G., Martinoia E., Lee Y. The phytochelatin transporters AtABCC1 and AtABCC2 mediate tolerance to cadmium and mercury. Plant J. 2012;69:278–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ishikawa S., Suzui N., Ito-Tanabata S., Ishii S., Igura M., Abe T., Kuramata M., Kawachi N., Fujimaki S. Real-time imaging and analysis of differences in cadmium dynamics in rice cultivars (Oryza sativa) using positron-emitting 107Cd trace. BMC Plant Biol. 2011;11:172. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-11-172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yokosho K., Yamaji N., Ueno D., Mitani N., Ma J.F. OsFRDL1 is a citrate transporter required for efficient transformation of iron in rice. Plant Physiol. 2009;149:297–305. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.128132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kawabe S., Fukumorita T., Chino M. Collection of rice phloem sap from stylets of homopterous insects severed by YAG laser. Plant Cell Physiol. 1980;21:1319–1327. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nishiyama R. Master thesis. Graduate School of Agricultural and Life Sciences, the University of Tokyo; Tokyo, Japan: 2006. Zinc Transport via Phloem in Rice Plants. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kato M. The University of Tokyo; Tokyo: 2006. Unpublished work. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nishiyama R., Kato M., Nagata S., Yanagisawa S., Yoneyama T. Identification of Zn-nicotianamine and Fe-2′-deoxymugineic acid in the phloem sap from rice plants (Oryza sativa L.) Plant Cell Physiol. 2012;53:381–390. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcr188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kato M., Ishikawa S., Inagaki K., Chiba K., Hayashi H., Yanagisawa S., Yoneyama T. 2010: Possible chemical forms of cadmium and varietal differences in cadmium concentrations in the phloem sap of rice plants (Oryza sativa L.) Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2010;56:839–847. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0765.2010.00514.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Álvarez-Fernández A., Díaz-Benito P., Abadía A., Lopez-Millán A.-F., Abadía J. 2014: Metal species involved in long distance metal transport in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2014;5:105. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ando Y., Nagata S., Yanagisawa S., Yoneyama T. Copper in xylem and phloem from rice (Oryza sativa): The effect of moderate copper concentrations in the growth medium on the accumulation of five essential metals and a speciation analysis of copper-containing compounds. Funct. Plant Biol. 2013;40:89–100. doi: 10.1071/FP12158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Obata H., Kitagishi K. Longitudinal distribution pattern of zinc and manganese in leaf with special reference to aging. Jpn. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 1980;51:285–291. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kitagishi K., Obata H., Kondo T. Effect of zinc deficiency on 80S ribosome content of meristematic tissues of rice plant. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 1987;33:423–429. doi: 10.1080/00380768.1987.10557588. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Obata H., Kitagishi K. Accumulation and retranslocation of zinc in a leaf of rice plant with reference to aging. Jpn. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 1982;53:235–240. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kitagishi K., Obata H. Retrieval of zinc from transpiration stream in the nodes of rice plants as affected by the concentration of zinc in culture solution. Rep. Environ. Sci. Mie Univ. 1982;7:91–97. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yamaguchi N., Ishikawa S., Abe T., Baba K., Arao T., Terada Y. Role of the node in controlling traffic of cadmium, zinc, and manganese in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 2012;63:2729–2737. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kitagishi K., Obata H. Distribution of 115mCd in rice plants absorbed by roots at vegetative stage. Rep. Environ. Sci. Mie Univ. 1979;4:59–65. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kobayashi N.I., Tanoi K., Hirose A., Nakanishi T.M. Characterization of rapid intervascular transport of cadmium in rice stem by radioisotope imaging. J. Exp. Bot. 2013;64:507–517. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ers344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tsukamoto T., Nakanishi H., Uchida H., Watanabe S., Matsuhashi S., Mori S., Nishizawa N.K. 2009: 52Fe translocation in barley as monitored by a positron emitting tracer imaging system (PETIS): Evidence for the direct translocation of Fe from roots to young leaves via phloem. Plant Cell Physiol. 2009;50:48–57. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcn192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yoneyama T., Gosho T., Kato M., Goto S., Hayashi H. Xylem and phloem transport of Cd, Zn and Fe into the grains of rice plants (Oryza sativa L.) grown in continuously flooded Cd-contaminated soil. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2010;56:445–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0765.2010.00481.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zee S.-Y. Transfer cells and vascular tissue distribution in the vegetative nodes of rice. Aust. J. Bot. 1972;20:41–48. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kawahara H., Chonan N., Matsuda T. Studies on morphogenesis in rice plants. 7. The morphology of vascular bundles in the vegetative nodes of the culm. Proc. Crop Sci. Soc. Jpn. 1974;43:389–401. doi: 10.1626/jcs.43.389. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chonan N., Kawahara H., Matsuda T. Ultrastructure of elliptical and diffuse bundles in the vegetative nodes of rice. Jpn. J. Crop Sci. 1984;54:393–402. doi: 10.1626/jcs.54.393. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wu C.-Y., Lu L.-L., Yang X.-E., Feng Y., Wei Y.-Y., Hao H.-L., Stoffella P.J., He Z.-L. Uptake, translocation, and remobilization of zinc absorbed at different growth stages by rice genotypes of different Zn densities. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010;58:6767–6773. doi: 10.1021/jf100017e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nishiyama R., Tanoi K., Yanagisawa S., Yoneyama T. 2013: Quantification of zinc transport to the grain in rice plants (Oryza sativa L.) at early grain-filling by a combination of mathematical modeling and 65Zn tracing. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2013;59:750–755. doi: 10.1080/00380768.2013.819774. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tanaka K., Fujimaki S., Fujiwara T., Yoneyama T., Hayashi H. Quantitative estimation of the contribution of the phloem in cadmium transport to grains in rice plants (Oryza sativa L.) Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2007;53:72–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0765.2007.00116.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rodda M.S., Li G., Reid R.J. The timing of grain Cd accumulation in rice plants: The relative importance of remobilization within the plant and root Cd uptake post-flowering. Plant Soil. 2011;347:105–114. doi: 10.1007/s11104-011-0829-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fujimaki S., Suzui N., Ishioka N.S., Kawachi N., Ito S., Chino M., Nakamura S. Tracing cadmium from culture to spikelet: Noninvasive imaging and quantitative characterization of absorption, transport, and accumulation of cadmium in an intact rice plant. Plant Physiol. 2010;152:1796–1806. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.151035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zee S.-Y. Vascular tissue and transfer cell distribution in the rice spikelet. Aust. J. Biol. Sci. 1972;25:411–414. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kawahara H., Matsuda T., Chonan N. Studies on morphogenesis in rice plants. 9. On the structure of vascular bundles and phloem transport in the spikelet. Proc. Crop Sci. Soc. Jpn. 1977;46:82–90. doi: 10.1626/jcs.46.82. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Herren T., Feller U. Transfer of zinc from xylem to phloem in the peduncle of wheat. J. Plant Nutr. 1994;17:1587–1598. doi: 10.1080/01904169409364831. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jiang W., Struik P.C., Lingna J., van Keulen H., Ming Z., Stomph T.J. Uptake and distribution of root-applied or foliar-applied 65Zn after flowering in aerobic rice. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2007;150:383–391. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7348.2007.00138.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sperotto P.A., Ricachenevsky F.K., Waldow V.A., Fett J.P. Iron biofortification in rice: It’s a long way to the top. Plant Sci. 2012;190:24–39. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2012.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Moritsugu M. A study on combination of glutelin with cadmium in rice grain. Ber. Obara Inst. Landwirtsch. Biol. 1964;12:251–260. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schuler M., Rellán-Álvarez R., Fink-Straube C., Abadía J., Bauer P. Nicotianamine functions in the phloem-based transport of iron to sink organs in pollen development and pollen tube growth in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2012;24:2380–2400. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.099077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yuan L., Wu L., Yang C., Lv Q. Effects of iron and zinc foliar applications on rice plants and their grain accumulation and grain quality. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2012;93:254–261. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.5749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ishimaru Y., Kim S., Tsukamoto T., Oki H., Kobayashi T., Watanabe S., Matsuhashi S., Takahashi M., Nakanishi H., Mori S., et al. Mutational reconstructed ferric chelate reductase confers enhanced tolerance in rice to iron deficiency in calcareous soil. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:7373–7378. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610555104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Masuda H., Usuda K., Kobayashi T., Ishimaru Y., Kakei Y., Takahashi M., Higuchi K., Nakanishi H., Mori S., Nishizawa K.N. Overexpression of the barley nicotianamine synthase gene HvHAS1 increases iron and zinc concentrations in rice grains. Rice. 2009;2:155–166. doi: 10.1007/s12284-009-9031-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lee S., Jeon U.S., Lee S.J., Kim Y.-K., Persson D.P., Husted S., Schjørring J.K., Kakei Y., Masuda H., Nishizawa N.K., et al. Iron fortification of rice seeds through activation of the nicotianamine synthase gene. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:22014–22019. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910950106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zheng L., Cheng Z., Ai C., Jiang X., Bei X., Zheng Y., Glahn R.P., Welch R.M., Miller D.D., Lei X.G., et al. Nicotianamine, a novel enhancer of rice iron bioavailability to humans. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e10190. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Reeves P.G., Chaney R.L. Bioavailability as an issue in risk assessment and management of food cadmium: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2008;398:13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Codex Alimentarius (2014) CODEX STAN 193–1995, General Standard for Contaminants and Toxins in Food and Feed. 1995. [(accessed on 31 March 2015)]. Available online: http://www.codexalimentarius.org/download/standards/17/CXS_193e2015.pdf.