Abstract

Racial/ethnic disparities in healthcare are widespread in the United States and are prevalent across healthcare organizations, including the “equal access” Veterans’ Affairs (VA) integrated healthcare system. Despite substantial attention to these disparities over the last decade, there has been limited progress in reducing them. Based on a review of evidence commissioned by the VA to guide its efforts to address racial and ethnic disparities, the conceptual framework describes the root causes of disparities in healthcare quality and outcomes, demonstrating why improvements in the quality of medical care have had limited influence over healthcare disparities that depend largely on social determinants of health. The recommended interventions—including care coordination, culturally-tailored health education, and community health workers—extend the reach of health systems beyond clinics and hospitals and into the communities and social and cultural contexts in which patients live, and in which most health promotion activities occur. To make inroads into addressing disparities, healthcare systems will need to move beyond conceptualizing care delivery as constrained to the clinical encounter and instead, incorporate an understanding of the social determinants of health.

Keywords: Race/ethnicity, Disparities, Interventions, Veterans

Racial and ethnic disparities in healthcare are widespread in the United States (1,2) and are prevalent even in the “equal access” Veterans Affairs (VA) integrated healthcare system.(3) As an organization committed to providing high-quality, equitable care, the VA has implemented programs expected to reduce disparities in care delivery and has made significant advances. However, some disparities have proven resistant to the VA’s quality improvement efforts. A recent study examining trends during the last decade found that although the VA achieved equity in certain quality metrics – particularly process measures such as obtaining appropriate blood tests –significant differences persisted between Black and non-Hispanic white Veterans, in outcomes that depended more on patient engagement. Rates of mammography for women and eye exams for patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus were similar by race. But disparities were observed for Veterans in rates of colonoscopy for colon cancer screening, and in clinical outcome measures such as lipid level declines in heart disease, glycemic control in diabetes, and blood pressure control in hypertension.(4) These findings suggest that the VA has been somewhat successful in improving quality of care and reducing disparities in service delivery by healthcare providers, but that these successes have not necessarily resulted in significant improvements in health equity for patients.

To investigate how best to tackle these persistent disparities, the VA commissioned a review of interventions conducted both within and outside of VA settings designed to improve the health of minority adult patients and reduce racial and ethnic disparities.(5) The review involved synthesizing findings from 34 systematic reviews of interventions to improve minority health in areas germane to VA patient populations (e.g., adults with chronic disease), with the potential for reducing disparities in health and healthcare. The quality of the included studies was variable, but a theme emerged suggesting that certain types of interventions – care coordination, culturally-tailored health education, and community health workers – demonstrated positive effects in improving health outcomes and equity.

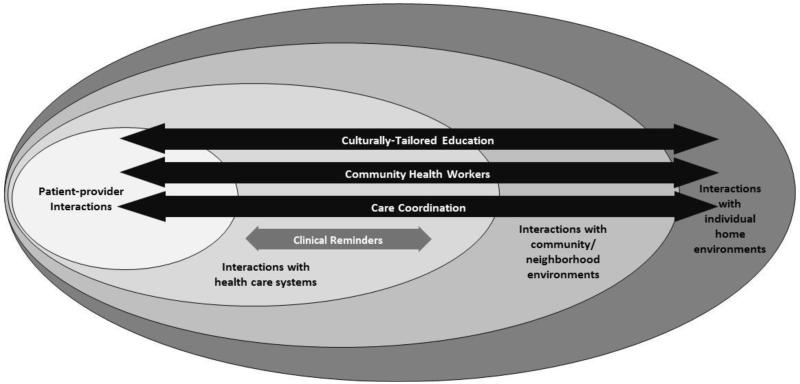

An important characteristic of each of these types of interventions is that they have the potential to go beyond the traditional purview of clinical care and reach into the social and cultural context in which patients live and experience illness and health. In this way, these interventions serve as bridges between the biomedically-oriented world of healthcare institutions and the community and home environments in which patients live. The review findings were consistent with those of similar inquiries assessing the effectiveness of disparities interventions.(6,7) For instance, a review commissioned by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation pointed toward interventions that are culturally tailored, use team-based approaches to providing care, and engage family and community members to improve healthcare outcomes for minority patients.(6)

Elements of promising interventions

Care coordination interventions involve system-level efforts to actively assign patients a healthcare system “point person” (often a registered nurse care manager) who is the conduit for patient interactions with the healthcare system. Care coordination programs involve management of treatment plans across primary and specialty care clinics, and can include various activities such as medication assistance programs, and work with patients to develop strategies for improved chronic disease self-management. Care coordination programs not only engage with patients, but also incorporate families, friends or caregivers into healthcare communications. Effective care managers attend not only to patients’ clinical needs but also to the social context in which patients live, enabling them to better support patients in monitoring and managing illness, particularly chronic illness.

Culturally-tailored educational programs attempt to enhance the comprehensibility and acceptability of healthcare services for patients, particularly those from non-Western cultures, who may have non-traditional perspectives and beliefs about health, illness, and medical care. The intent of these programs is to communicate with patients using a cultural lens, integrating cultural references to better relate and convey health information. For instance, efforts to present health education materials in relatable ways—such as nutritional information that considers staple foods with cultural significance—may have more meaning when communicating important health messages. These programs translate traditional healthcare interventions to make them more culturally aligned with the patient’s own context, increasing the chance that the intervention will be comprehensible, acceptable, and adhered to.

Community health workers—typically members of the patients’ own communities—provide a personal link between healthcare systems and patients who often have difficulty navigating these systems and are more receptive to individuals whom they perceive to be part of their peer group. They provide a bridge to compensate for scarce community resources, help patients navigate their care, ensure the cultural appropriateness of healthcare interventions, and tailor treatment plans to accommodate extenuating personal, family or social circumstances. In this way, community health workers combine the benefits of care managers and culturally-tailored education, by simultaneously attending to patients’ social and cultural contexts. In various models of healthcare systems change, community health workers are also integrated as part of coordinated and managed care programs to form multi-faceted and multi-pronged interventions.

A conceptual model of intervention reach

To illustrate that interventions with more extended reach had greater impact in addressing disparities, a social ecological model was developed (Figure 1) to map these evidence-based interventions onto areas that influence individual health and healthcare. Racial/ethnic disparities in healthcare are conceptualized in this model as being driven by a broad array of social factors, ranging from education and personal means to community infrastructure and resources. These social factors represent the context in which the vast majority of actual healthcare – as prescribed in very brief interactions between patients and providers – occurs. Accordingly, interventions demonstrating the most promise for reducing disparities are those that reach beyond traditional clinical encounters and into patients’ social and cultural contexts. In contrast, interventions targeting processes within healthcare systems, such as the implementation of more frequent or specialized clinical reminders, often do not reap far-reaching health benefits.

Figure 1. Reach of Interventions to Reduce Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Care and Outcomes.

The model reflects the fact that race and ethnicity are social constructs whose influences on health status are mediated largely by the effects of segregation, marginalization, discrimination, and deprivation on the social position of different groups of people. Accordingly, as noted by others,(8,9) many racial and ethnic disparities likely arise from fundamental social determinants of health—the resources individuals have access to and the environments they reside in have powerful and lasting effects on the development and maintenance of good health across the lifespan. From this perspective, it is unsurprising that interventions that bridge clinical and community environments have more detectable effects.

Although tackling social determinants might fall, strictly speaking, outside the traditional purview of medical care, connecting the multiple areas depicted in Figure 1 should fall within the purview of patient-centered healthcare.(10) Healthcare providers and organizations may not be able to remedy the societal inequities that give rise to health disparities, but if their goal is to improve the health of all the people they serve, they can and should extend the scope of issues they address beyond the clinical and into the social and cultural realms.

Future directions to achieve greater health equity

Reducing disparities in healthcare delivery and outcomes poses challenges that will require integrating medical care and public health interventions, as well as linking health systems to communities. To make inroads into addressing disparities, healthcare systems will need to move beyond conceptualizing care delivery as constrained to the clinical encounter and instead, incorporate an understanding of the social determinants of health. In this view, actions taken to safeguard health extend beyond work conducted in medical facilities but also incorporate resources available in patient communities, neighborhoods, and consider the existing challenges faced at home.(10-12) Transforming healthcare systems to take on a public health orientation will require a major shift in focus. Such an approach, however, is in line with current efforts to make the delivery of healthcare more patient-centered, responsive, and comprehensive.

Incentives for Healthcare Systems

The impetus to make these transformative changes will, in large part, be determined by the alignment of incentives specific to healthcare systems as they adopt and integrate these interventions into the healthcare they deliver. Some of the identified interventions might be better- or less-well suited to the financial structures of specific healthcare organizations. For example, whereas large integrated healthcare systems—such as the VA and large closed panel HMOs—may have incentives aligned to ease the adoption of the structural changes necessary for the rollout of coordinated care interventions, smaller fee-for-service organizations operating on limited budgets—such as federally-qualified health centers (FQHCs) and community clinics—could find large-scale rollouts cost-prohibitive. Large integrated healthcare systems may be better poised and capacitated to experiment with innovative and far-reaching interventions by benefitting from large economies of scale, lower transaction costs, and a greater ability to bear risk. Nevertheless, over the past year new legislative provisions allow state federal agencies to experiment with innovative healthcare delivery models, including reimbursing preventive services delivered by CHWs. Effective January 1, 2014* the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services allow state agencies to reimburse preventive care provided by professionals that may fall outside of a state clinical licensure systems— such as CHWs—provided services are recommended by a licensed practitioner. The added flexibility in health care delivery strategies could further incentivize and enable FQHCs to adopt CHW models of care.

The changing healthcare landscape led by the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) involves heavy investments ($11 billion) in FQHC expansion.(13) In turn, FQHCs are engaging in strategies to reduce health disparities for the most vulnerable populations.(14) The PPACA also supports the community-based Collaborative Care Network Program to enable local health care providers to coordinate and integrate health care services. The effectiveness of these reforms will rest, in part, on the ability of local partnerships to create sustainable models of primary care delivery that effectively leverage community resources and align with patient needs.(13) The Collaborative Care Network Program also provides an outlet for the diffusion of successes achieved by community clinics at the forefront of testing and adopting reforms whose best-practices can be communicated to later-adopting clinics.

It is also the case that both, healthcare organizations and patient communities must foster a readiness for change to sustain population health improvements for patients from diverse backgrounds.(15-17) In building community health worker programs, workers must be acceptable and trustworthy to patients in order to achieve the desired results of activating patients, facilitate their ability to manage health conditions, and encourage long-term health improvements. Trust is particularly salient when deploying a new workforce into communities where adults from underrepresented race/ethnic backgrounds live and work. Similarly, educational interventions that are culturally-aligned to patient values and norms ensure that health messaging is delivered in a manner in which patients are more apt to adhere to.

Large Integrated Healthcare Systems—VA Experience

The VA provides an example of how healthcare systems can extend their reach. First, the VA has built networks of community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs). The CBOCs, which extend the VA’s regionalized healthcare system into smaller communities, make care more accessible for Veterans in less-populated areas and address potential disparities based on rural residence. Located in greater proximity to Veterans’ communities and homes than larger VA Medical Centers, CBOC clinicians and staff are more able to understand Veterans’ social contexts and incorporate them into care plans. CBOCs can extend the VA’s reach even further by forming partnerships with local community-based organizations, to better address Veterans’ social needs.

The VA’s adoption of the medical home model, through Patient Aligned Care Teams (PACTs), also enhances its ability to extend its reach. By integrating clinicians with care managers and social workers, and providing team-based care for all Veterans, the PACT transformation holds promise for clinical care teams to better attend to social issues. As PACTs evolve, their impact on disparities may be optimized by ensuring that members of the team are trained and equipped to address social and cultural dimensions of health.

Finally, as an organization that cares for a defined group of patients – i.e., Veterans – the VA has begun to utilize peer health educators and counselors, who effectively function as community health workers. Veterans trained to support and counsel other Veterans serve the same bridging function that traditional community health workers do. Initiatives to tap into this rich resource have already begun to show promise. In a recent study of African American Veterans with diabetes, those who were assigned peer mentors achieve improved glucose control compared to usual care.(18) The peer mentors were also more effective than giving patients financial reimbursement for better diabetes control, suggesting the added importance of providing support and addressing social and cultural barriers.

To improve health and reduce health disparities in the 21st century, healthcare organizations will need to extend the reach of their services to address social and cultural influences on health and health behavior. This shift will require healthcare delivery systems to break down the walls between medicine and public health and go beyond the traditional purview of clinical care to address the social determinants that underlie health disparities. As a health system committed to elevating patient-centered care and eliminating inequities, the VA has put structures in place that extend its reach into Veterans’ communities. These structures can be further leveraged to address the social and cultural domains of health and, in so doing, achieve the elusive goal of reducing disparities in health and healthcare.

Acknowledgement of funding

This article is based in part on research conducted by the Evidence-based Synthesis Program (ESP) Center located at the Portland VA Medical Center, Portland OR and funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Health Services Research and Development. Dr. Quiñones is also supported by the American Diabetes Association (ADA 7-13-CD-08, Quiñones PI) and the Programs to Increase Diversity among Individuals Engaged in Health Related-Research (NIH/NHLBI, R25HL105430).

Footnotes

Medicaid and children’s health insurance programs: essential health benefits in alternative benefit plans, eligibility notices, fair hearing and appeal processes, premiums and cost sharing, exchanges: eligibility and enrollment; final rule. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 78 Fed Reg 42160 (July 15, 2013). Under section, “a. Diagnostic, Screening, Preventive, and Rehabilitative Services (Preventive Services) (§ 440.130)” (paragraph citation: 78 FR 42226). Source: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2013-07-15/pdf/2013-16271.pdf

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs, the American Diabetes Association, or the National Institutes of Health.

Conflicts of interest: Authors Quiñones, Talavera, Castañeda, and Saha report no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Standards Statement: No animal or human studies were carried out by the authors for this article.

References

- (1).Hayward MD, Miles TP, Crimmins EM, Yang Y. The significance of socioeconomic status in explaining the racial gap in chronic health conditions. Am Sociol Rev. 2000:910–930. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Wong MD, Shapiro MF, Boscardin WJ, Ettner SL. Contribution of major diseases to disparities in mortality. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(20):1585–1592. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa012979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Saha S, Freeman M, Toure J, Weeks C, Said I. Racial and ethnic disparities in the VA health care system: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(5):654–671. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0521-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Trivedi AN, Grebla RC, Wright SM, Washington DL. Despite improved quality of care in the Veterans Affairs health system, racial disparity persists for important clinical outcomes. Health Aff. 2011;30(4):707–715. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Quiñones A, O’Neil M, Saha S, Freeman M, Henry S, Kansagara D. Interventions to improve minority health care and reduce racial and ethnic disparities. Department of Veterans Affairs: VA Evidence-based Synthesis Program Reports; Washington DC: 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Chin MH, Clarke AR, Nocon RS, Casey AA, Keesecker NM. A roadmap and best practices for organizations to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(8):992–1000. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2082-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Clarke AR, Goddu AP, Nocon RS, Stock NW, Chyr LC, Akuoko J, et al. Thirty years of disparities intervention research: what are we doing to close racial and ethnic gaps in health care? Med Care. 2013;51(11):1020–1026. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182a97ba3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Link BG, Phelan J. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. J Health Soc Behav. 1995:80–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Williams DR, Collins C. Racial residential segregation: a fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Rep. 2001;116(5):404. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.5.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Gruen RL, Pearson SD, Brennan TA. Physician-citizens—public roles and professional obligations. JAMA. 2004;291(1):94–98. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.1.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Thomas SB, Quinn SC, Butler J, Fryer CS, Garza MA. Toward a fourth generation of disparities research to achieve health equity. Annu Rev Public Health. 2011;32:399. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Gehlert S, Sohmer D, Sacks T, Mininger C, McClintock M, Olopade O. Targeting health disparities: A model linking upstream determinants to downstream interventions. Health Aff. 2008;27(2):339–349. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.2.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Fiscella K. Health care reform and equity: promise, pitfalls, and prescriptions. Ann Fam Med. 2011 Jan-Feb;9(1):78–84. doi: 10.1370/afm.1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Gold R, DeVoe J, Shah A, Chauvie S. Insurance continuity and receipt of diabetes preventive care in a network of federally qualified health centers. Med Care. 2009 Apr;47(4):431–439. doi: 10.1097/mlr.0b013e318190ccac. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Castañeda SF, Holscher J, Mumman MK, Salgado H, Keir KB, Foster-Fishman PG, et al. Dimensions of community and organizational readiness for change. Progress in community health partnerships: research, education, and action. 2012;6(2):219–226. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2012.0016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Lukas CV, Holmes SK, Cohen AB, Restuccia J, Cramer IE, Shwartz M, et al. Transformational change in health care systems: an organizational model. Health Care Manage Rev. 2007 Oct-Dec;32(4):309–320. doi: 10.1097/01.HMR.0000296785.29718.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Wagner EH, Austin BT, Davis C, Hindmarsh M, Schaefer J, Bonomi A. Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action. Health Aff (Millwood) 2001 Nov-Dec;20(6):64–78. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.6.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Long JA, Jahnle EC, Richardson DM, Loewenstein G, Volpp KG. Peer Mentoring and Financial Incentives to Improve Glucose Control in African American Veterans: A Randomized Trial. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(6):416–424. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-156-6-201203200-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]