Abstract

The hybrid between Brassica napus and B. rapa displays obvious heterosis in both growth performance and stress tolerances. A comparative transcriptome analysis for B. napus (AnAnCC genome), B. rapa (ArAr genome), and its hybrid F1 (AnArC genome) was carried out to reveal the possible molecular mechanisms of heterosis at the gene expression level. A total of 40,320 nonredundant unigenes were identified using B. rapa (AA genome) and B. oleracea (CC genome) as reference genomes. A total of 6,816 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were mapped in the A and C genomes with 4,946 DEGs displayed nonadditively by comparing the gene expression patterns among the three samples. The coexistence of nonadditive DEGs including high-parent dominance, low-parent dominance, overdominance, and underdominance was observed in the gene action modes of F1 hybrid, which were potentially related to the heterosis. The coexistence of multiple gene actions in the hybrid was observed and provided a list of candidate genes and pathways for heterosis. The expression bias of transposable element-associated genes was also observed in the hybrid compared to their parents. The present study could be helpful for the better understanding of the determination and regulation of mechanisms of heterosis to aid Brassica improvement.

1. Introduction

Brassica napus (rapeseed, AACC, 2n = 38) is one of the main oil crops used for human consumption and is widely grown in China, Canada, Europe, and Australia and increasingly grown in South America [1]. B. napus is likely derived from the natural hybridization and genome doubling from its two diploid parents, B. rapa (genome AA, 2n = 20) and B. oleracea (genome CC, 2n = 18) along the Mediterranean coastline in Southern Europe approximately 10,000 years ago [2]. However, there is evidence that the genetic diversity in rapeseed has been continuously reduced by extensive breeding efforts [3]. Approaches to increase the genetic variation of rapeseed have been made by introducing the genetic components from related species as B. napus can easily cross with one of its ancestral parents, B. rapa, to produce viable interspecies hybrids [4]. Due to the high crossability between B. napus and B. rapa, and low aneuploidy of their interspecific hybrids, different B. rapa accessions have been widely hybridized to rapeseed breeding program and novel agronomic traits from B. rapa have been successfully transmitted into commercial B. napus varieties [5]. Strong heteroses affecting both biomass and seed yield have been observed in hybrids derived from these interspecific crosses [6]. However, the genetic and molecular mechanism of heterosis in the interspecific hybrids has not been investigated.

Heterosis is a prevalent phenomenon in evolution and breeding process of plants [7]. The hybrid offspring obtains the advantages in many agricultural and developmental traits including biomass yield, plant height, vigor, and stress tolerances from their parents, thereby improving the adaptation of the crop and subsequently increasing the global area sown [8]. Although heterosis has been widely utilized, the genetic and molecular basis of heterotic improvements remains unclear. Various genetic models have been proposed for explaining heterosis and include dominance, overdominance, and pseudo overdominance [9]. Heterotic interactions in the tetraploid B. napus can be derived from two types of allelic interactions, namely, those between the genomes of the two diploid progenitors as well as those between the two parental genomes making up a hybrid. Gene expression is potentially altered not only due to a dosage effect but also with gene functional divergence [8]. Epigenetic modification in hybrids genomes can also account for heterosis [10]. Emerging new technologies make it possible to investigate the DNA sequence, RNA transcripts, proteins, and metabolism products genome-wide, allowing for new insights into benefits of heterotic recombinations [7, 9]. Next generation sequencing technology utilizing RNA-seq has emerged as a powerful tool for investigating gene expression data at the whole genome level. Both the gene transcript and expression levels can be detected in RNA-seq which could provide new insights into the molecular mechanisms of heterosis [11].

Chinese cabbage, Brassica rapa (syn. B. campestris), contains two subspecies named pekinensis and chinensis. These two distinct groups are used as leafy vegetables widely across eastern Asia and have much genetic variation. In particular, B. rapa ssp. chinensis has wide morphological variation and is found in China, Korea, and Japan [12]. Recently, a number of genes responsible for developmental and stress tolerances were isolated [13–15], showing that B. rapa ssp. chinensis could be a novel resource for B. napus improvement.

In this study, the transcriptomes of B. rapa ssp. chinensis Makino, B. napus, and their interspecific hybrid were sequenced to investigate the molecular basis of heterosis. Gene expression profiles were used to identify the number of differentially expressed genes, and gene expression levels were analyzed and compared among two parents and their hybrid. This data was used to give a better understanding of additive and nonadditive effects of genes and how these contribute to heterosis, thus providing new insights into the genetic and epigenetic mechanism of subgenomic heterosis in B. napus.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Preparation and RNA Isolation

Three lines were grown in a green house at 22°C under 12 hours of light and 12 hours of darkness. Leaves of the seedling were harvested after 4 weeks by cutting off the sixth leaf of each seedling. The leaves of four plants were combined for RNA extraction. Samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until RNA was extracted. Total RNA of each sample was isolated using RNAprep Pure Plant Kit (Tiangen, Shanghai, China). RNA quality was characterized initially by NanoDrop ND1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA) and then further assessed by RIN (RNA Integrity Number) value (>9.5) using Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Santa Clara, CA, USA). Equal quantities of high-quality RNA from each sample were pooled for cDNA synthesis. Cytological observation of the F1 hybrid was performed as described by Zhan et al. [16].

2.2. cDNA Library Construction for Illumina Sequencing

The cDNA library was constructed following the manufacturer's instructions of mRNA-Seq Sample Preparation Kit (cat. number RS-930-1001, Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA). Briefly, the poly(A) mRNA was isolated from total RNA samples with Magnetic Oligo (dT) Beads. The mRNA was then fragmented into small pieces using RNA fragmentation kit (Ambion). Using these short fragments as the templates, the first cDNA strand was synthesized using random hexamer primers and reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen), and the second-strand cDNA was synthesized using DNA polymerase I and RNase H. The cDNA fragments were purified using the QiaQuick PCR extraction kit (Qiagen) and resolved with EB buffer for end reparation and poly(A) addition. The short fragments were then connected with sequencing adapters, and the products were subsequently purified and amplified via PCR. Libraries were prepared from a 400–500 bp size-selected fraction following adapter ligation and agarose gel separation. The quality control analysis on the sample library was performed to quantify the DNA concentration and validate the library. After validation with an Eppendorf Mastercycler Real-Time PCR System, the cDNA libraries were sequenced on the Illumina Hiseq 2000 platform with read length of 2 × 100 bp. The sequencing-derived raw image data were transformed by base calling into sequence data using Illumina Pipeline Software v1.6. The raw sequencing reads have been submitted to NCBI Short Read Archive under the accession number of SRR2131203, SRR2134440, and SRR2134444.

2.3. Sequence Data Analysis and Expression Analysis

The raw reads were cleaned by removing adapter sequences, low-quality sequences (reads with ambiguous bases “N”), and reads with more than 10% Q < 20 bases. To analyze transcript abundance levels, the uniquely mapped reads for a specific gene were counted by mapping reads to de novo assembled distinct sequences using SOAP2 software [17], and the RPKM (Reads Per Kb per Million reads) values were computed as proposed by Mortazavi et al. [18]. Gene transcript abundance differences were obtained from RPKM values using a method modified from Audic's proposal [19]. Gene expression levels were calculated with the RPKM method which is able to eliminate the influence of different gene lengths and sequencing discrepancy within the calculation of gene expression.

2.4. Statistics

Statistical analysis of the phenotypic data was performed with a Welch two-sample t-test in R (R Development Core Team 2005) [20]. Midparent heterosis (MPH) values were calculated using the formula MPH = (h − (P1 + P2)/2)/((P1 + P2)/2)∗100 + 100 (whereas h is the value of the hybrid and P1 and P2 are the values of the one and the other parental line). To test for significance of MPH values the contrast h − (P1 + P2)/2 was used [21].

2.5. Quantitative RT-PCR Validation of Differentiation Gene Expression

RNA-seq data were further validated using quantitative real-time PCR analysis (qRT-PCR) for a selected number of genes using gene-specific primer sets. The plant leaves and growth condition for total RNA extraction used for qRT-PCR were the same as these for RNA-seq experiments. Three independent RNA extractions per sample were performed for biological replicates. The reverse transcribed into cDNA using PrimeScritH RT reagent kit with gDNA Eraser (Takara, Dalian, China). Primer pairs of 10 unigenes were designed using Invitrogen's (Carlsbad, CA, USA) OligoPerfect Designer software [22]. Specificity of the primer sets and their product length was verified by agarose gel electrophoresis. The qRT-PCR reaction mixture consisted of the SYBR Premix EX-Taq II Kit (TakaRa, Japan) on iCycler iQ (BIO-RAD) for three repeats of each sample. The thermal cycling conditions were as follows: 95 uC 2 min and 40 cycles at 95°C for 10 s for denaturation and 65°C 20 s and 72°C 30 s for annealing and extension. The expression of TIPS-41 with primer sequences 5′-TGAAGAGCAGATTGATTTGGCT-3′ and 5′-ACACTCCATTGTC AGCCAGTT-3′ was used as an internal control for normalization to compare the gene expression level between the accessions. The relative levels of gene expression were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Preparation, Sequencing, and Data Filtering

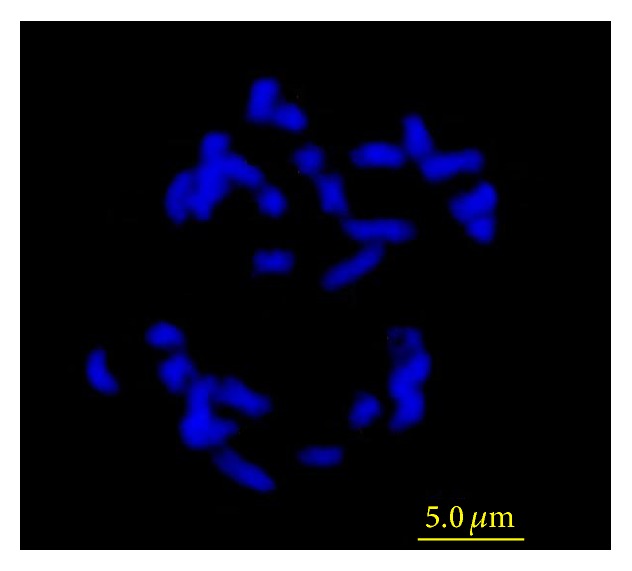

The hybridization of B. napus cv. CWH-2 (P1) and B. rapa ssp. chinensis cv. Qianjin (P2) was made in 2010-2011 oilseed growing season. Root-tip chromosome assessments of F1 showed that all F1 plants had a chromosome number of 29 (Figure 1), suggesting that they were hybrids. The seeds' sizes of F1 hybrids were intermediate to those of the parents, but the seed color resembled that of B. napus (Figure 2(a)). Root growth of the F1 over the first 24 h was similar to P1. Leaf morphology of the F1 was more similar to B. rapa than to B. napus (Figure 2). In 4-week-old seedlings, the F1 plant displayed stronger roots than either of the parents (Figure 2(b)) while adult F1 plants displayed the similar heading time to B. napus.

Figure 1.

Root tip squash showing chromosomes from the F1 hybrid (chromosome number of 29).

Figure 2.

Seed germination (a) and 2-week-old seedlings (b) of P1, P2, and F1 germplasm.

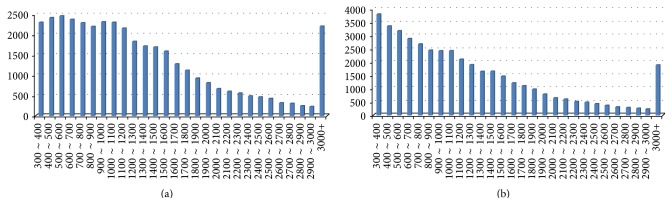

To identify transcripts of P1, P2, and F1, three cDNA libraries were constructed from their leaves and sequenced by Illumina paired-end sequencing. Sequence data from each of the libraries consisted of 6.0 Gb from B. rapa (AA genome), 5.2 Gb from B. napus (AACC genome), and 6.7 Gb from the hybrid (AAC genome). High-quality cleaned raw reads from all of those data were aligned to reference sequences. In total, 67,951,208 reads and 46,207,184 reads were mapped in the B. rapa and B. oleracea reference genomes, respectively. In the B. rapa genome, 38,522 unigenes were assembled with a minimum scaffold size of 200 bp and a total length of 51,995,312 bp, with an average length of 1,349 bp (Figure 3(a)). The B. oleracea genome had a total of 42,009 unigenes with a minimum scaffold size of 300 bp, a total length of 51,691,329 bp, and an average length of 1,230 bp (Figure 3(b)).

Figure 3.

The size distribution of transcriptomic unigenes assembled by the B. rapa (a) and B. oleracea (b).

3.2. Heterosis of Differential Gene Expression in B. rapa, B. napus, and Their Hybrid

The numbers of expressed gene in each genome varied slightly. There were 29,579 (71.8%), 27,939 (67.9%), and 29,447 (71.7%) from B. rapa, B. napus, and the hybrid genome, respectively. The unique mapping rates were similar among three Brassica samples, suggesting that their genomes were quite alike. Some genes had expression that was germplasm specific. The B. rapa genome had approximately about 6% (1,639) of genes that were unique, whilst B. napus and the hybrid had only 2% (420) and 3% (951) unique sequences, respectively. There were 25,985 genes expressed in all three lines. A total of 489 genes were expressed in both B. rapa and B. napus but silenced in the hybrid. Gene expression profiles of the three lines revealed that the number of expressed genes did not show obvious difference in the three sets of material. The mode of gene action for the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) was analyzed. About 27.00% genes (1840 of 6816) exhibited an expression pattern that was not distinguishable from additivity, while the other 72.56% (4946 of 6816) of genes showed nonadditive expression patterns (Table 1). The nonadditive number of DEGs from the cross was further classified into five distinct classes: high-parent dominance (HPD), low-parent dominance (LPD), overdominance (ODO), underdominance (UDO), and partial-dominance. There were 7% of transcripts (545) that were absent in their parents, indicating that there was transcriptional activation of new genes in hybrid F1. There was also transcriptional silencing with 3.2% (218) of parentally expressed gene not being expressed in the hybrid.

Table 1.

Summary of dominance patterns of differentially expressed genes.

| DGs | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Additivity | 1840 | 27 |

| Nonadditivity | 4946 | 72.56 |

| Others | 30 | 0.44 |

| High-parent dominance (HPD) | 353 | 7.14 |

| Low-parent dominance (LPD) | 191 | 3.86 |

| Overdominance (ODO) | 593 | 11.99 |

| Underdominance (UDO) | 193 | 3.9 |

| Positive partial-dominance (PPD) | 1635 | 33.06 |

| Negative partial-dominance (NPD) | 1981 | 40.5 |

| Total | 6816 |

Additivity: F1 ≈ 1/2(P1 + P2); nonadditivity: F1 > 1/2(P1 + P2) or F1 < 1/2(P1 + P2). High-parent dominance (HPD): F1 ≈ P1 > P2 or F1 ≈ P2 < P1; low-parent dominance (LPD): F1 ≈ P1 < P2 or F1 ≈ P2 < P1; overdominance (ODO): F1 > P1 and F1 > P2; underdominance (UDO): F1 < P1 and F1 < P2.

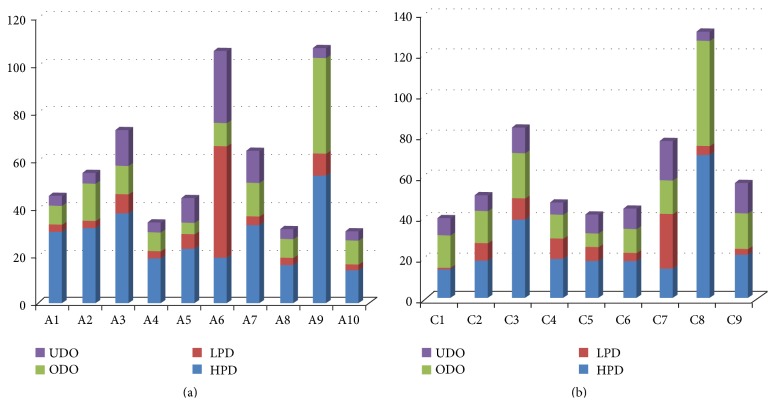

There were 2894 unigenes that mapped to the A genome, 2107 that mapped to the C genome (Figure 4), and 593 that were not assigned to either genome. Chromosomal distribution of DEG numbers in hybrids showed that low-parent domiance (LPD) genes were significantly accumulated on chromosomes A06 and C07 (P < 0.001), while high-parent dominance (HPD) genes were on chromosomes A09 and C08 (P < 0.01). Gene expression variation caused by interspecific hybridization was not randomly distributed along the chromosomes. Therefore, different B. napus-B. rapa chromosome introgression lines can be developed to the further study of heterosis pertaining to specific chromosomes.

Figure 4.

Chromosomal distribution of nonadditive differentially expressed genes with high-parent dominance (HPD), low-parent dominance (LPD), overdominance (ODO), and underdominance (UDO) on the A genome (a) and C genome (b).

3.3. Contribution of A and C Subgenomes to Gene Differential Expression in the Hybrid

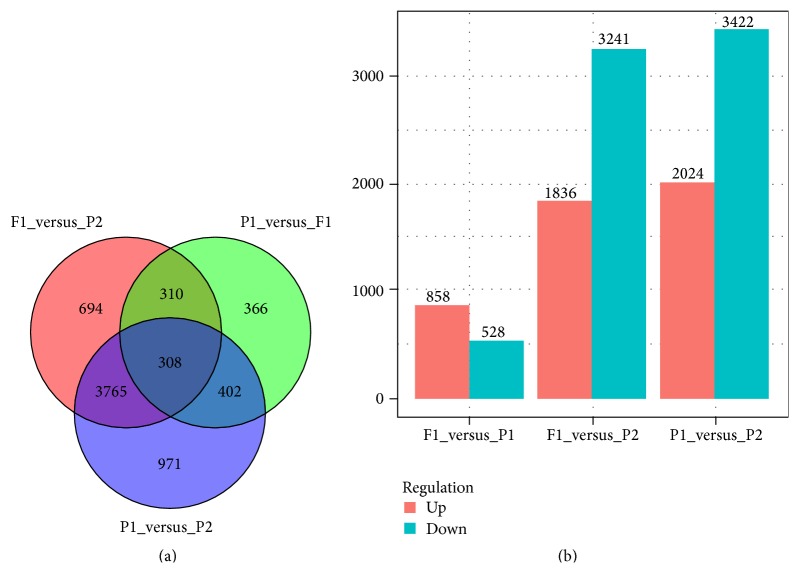

There were 1386 significant differentially expressed genes between P1 and F1 samples, 858 genes had increased expression in the F1, and 528 genes had decreased expression. There were 5077 significant differentially expressed genes between P2 and F1 samples, with 3241 genes having increased expression in the F1 and 1836 genes being decreased in expression (Figure 5). Changes to expression from P2 were approximately three times the number of genes compared to from P1. There were more genes with increased expression in the F1 (4098) than with decreased expression (2464) when compared to expression levels in the respective parents. We performed gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis to test the functional categories for DEGs among P1, P2, and F1 (Figure 6) by AgriGO online tool [23] and R statistical software [20]. There were 10, 12, and 18 functional categories of these transcripts that belonged to the cell component (CC), molecular function (MF), and biological process (BP), respectively. The GO analysis showed that the composition of functional pathways associated with genes showing differential expression was similar when comparing changes from either P1 or P2 with F1.

Figure 5.

Total numbers of differentially expressed genes between P1, P2, and F1 by Venn diagram analyses (a) and statistics of up- or downregulated genes (b).

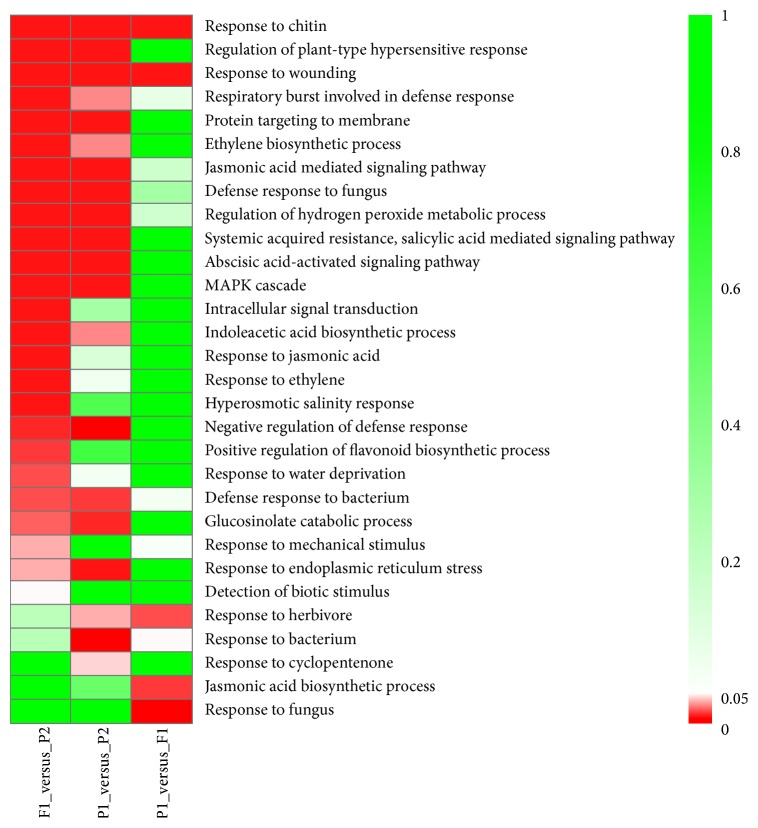

Figure 6.

The heat map from GO enrichment analysis of DEGs between the P1, P2, and F1 combinations. Color scale represents P values of enrichment test.

The biological process category was further subdivided into functional classes in those DEGs with high-parent dominance (HPD, P < 0.5) based on gene ontology. Table 2 highlights the 18 gene ontology classes that were differentially expressed in the F1. Combined with the results in Figure 6, we found that the GOs such as regulation of transcription, metabolic process, defense response, multicellular organismal development, and transporters were enriched in A genomes transcripts. The genes responsible for stress were striking enriched in the differential expressed genes from C genome. It possibly implied that the hybrid expressed protein-coding genes from A genomes of both B. rapa and B. napus potentially participated in metabolism and development, while those from C genome of B. napus were largely involved in stress resistance.

Table 2.

Significant gene ontology terms of high-parent dominance (HPD) in the biological process category from A and C genomes.

| Gene ID | Gene O terms |

|---|---|

| Bra028791 | Regulation of transcription (GO:0006355) |

| Bra005111 | Metabolic process (GO:0008152) |

| Bra032185 | Defense response (GO:0002679) |

| Bra010724 | Multicellular organismal development (GO:0007275) |

| Bra007111 | Metabolic process (GO:0010408) |

| Bra031515 | Single-organism transport (GO:0044765) |

| Bra031678 | Transport (GO:0006810) |

| Bra027171 | Transmembrane transport (GO:0006855) |

| Bra024033 | Peroxidase activity (GO:0004601) |

| Bra002550 | Chromosome segregation (GO:0007059) |

| Bol015697 | Response to molecule of bacterial origin (GO:0002237) |

| Bol032712 | Defense response to insect (GO:0002213) |

| Bol014351 | Defense response to bacterium (GO:0042742) |

| Bol045822 | Defense response (GO:0002679) |

| Bol034224 | Response to wounding (GO:0009611) |

| Bol038369 | Single-organism process (GO:0044699) |

| Bol045822 | Regulation of transcription (GO:0006355) |

| Bol015697 | Response to molecule of bacterial origin (GO:0002237) |

3.4. Transposon Active or Inactive in Hybrid

Compared to the B. rapa genome, there were 25 transposable elements (TE) like genes expressed in P1 and P2, while the 11 (44%) genes displayed differential expression in F1 (Table 3). The En/Spm type of transposon, and the retrotransposon-like transcript were significantly enriched. It is likely that the interspecific hybrids significantly modify the transcription of transposon-like genes, which may directly or indirectly influence gene expression of other genes in the heterotic material.

Table 3.

The differential expressed transposon-like genes in hybrid F1.

| Gene ID | Regulation | Chromosome | Similar to transposon |

|---|---|---|---|

| B.rapa.newgene.1068 | Inactive | A09 | Retrotransposon-like protein (Arabidopsis thaliana) |

| B.rapa.newgene.871 | Inactive | A07 | Putative transposon protein (Arabidopsis thaliana) |

| B.rapa.newgene.1142 | Inactive | A09 | Retrotransposon-like protein (Arabidopsis thaliana) |

| B.rapa.newgene.957 | Inactive | A08 | Retrotransposon (Arabidopsis thaliana) |

| Bra040302 | Up | A08 | Putative transposon protein (Arabidopsis thaliana) |

| B.rapa.newgene.307 | Up | A03 | En/Spm transposon protein (Arabidopsis thaliana) |

| B.rapa.newgene.726 | Up | A06 | En/Spm-like transposon protein (Arabidopsis thaliana) |

| Bra034711 | Active | A05 | hAT transposon superfamily protein (Arabidopsis thaliana) |

| Bra027867 | Active | A09 | Pol polyprotein transposon element Bs1 (Zea mays) |

| B.rapa.newgene.8 | Active | A01 | Tam1 transposon protein (Arabidopsis thaliana) |

| Bra035011 | Active | A07 | Putative transposon protein (Arabidopsis thaliana) |

| Bol019342 | Inactive | C09 | Retrotransposon Tto1 DNA (Nicotiana tabacum) |

| Bol041429 | Up | C07 | Putative Tam3-like transposon protein (Zea mays) |

| Bol035479 | Down | C03 | En/Spm-related transposon protein (Brassica oleracea) |

| Bol005562 | Down | C03 | En/Spm-related transposon protein (Brassica oleracea) |

| Bol019765 | Down | C09 | En/Spm-related transposon protein (Brassica oleracea) |

| Bol006373 | Down | C07 | Transposon protein-like (Arabidopsis thaliana) |

| Bol035958 | Up | C02 | Transposon-like ORF (Brassica oleracea) |

| Bol030703 | Active | C03 | Retrotransposon Tto1 DNA (Nicotiana tabacum) |

| Bol030374 | Active | C09 | En/Spm-related transposon protein (Brassica oleracea) |

| Bol004880 | Active | C04 | Retrotransposon Tto1 DNA (Nicotiana tabacum) |

| Bol043208 | Active | C07 | Similar to retrotransposon (Arabidopsis thaliana) |

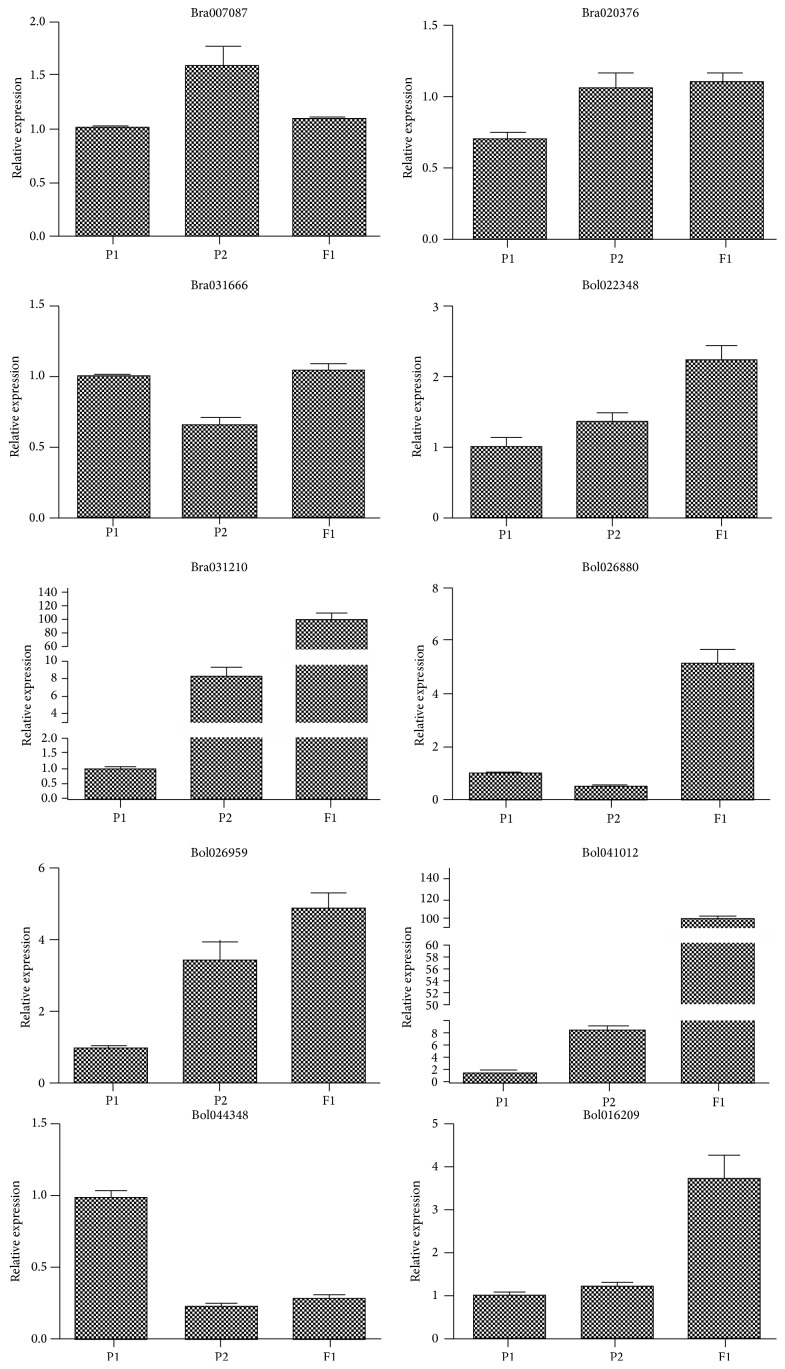

3.5. Validation of Transcriptome Data by qRT-PCR

To assess the accuracy of RNA-seq data, ten differentially expressed unigenes including stress responsive genes, secondary metabolism biosynthesis genes, and epigenetic modifying genes were selected. Three genes belong to underdominance (UDO) and seven genes are belonging to overdominance (ODO) types, which are represented for heterosis analysis. Primer pairs of 10 unigenes for qRT-PCR were designed and listed in Table 4. We tested the similarity between differential gene expression identified by transcriptome and those identified by qRT-PCR. As shown in Figure 7, the qRT-PCR revealed that 8 of 10 genes (except Bol022348 and Bol026880) that showed the differential gene expression level agreed well with the expression patterns of DGE data. Hence, the qRT-PCR results showed general agreement with their transcript abundance changes determined by RNA-seq, which suggested the reliability of the transcriptomic profiling data among the three samples.

Table 4.

The qPCR primers for selected genes.

| Unigenes | Primers | Biological process | Nonadditivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bra007087 F | TGCAGCGCTTGATTTACCT | Oxidation-reduction process |

HPD |

| Bra007087 R | GCAAACTCCAGAGCTATGT | ||

| Bra020376 F | AGGTCATTCTGGTGAGCCACA | Chaperones | HPD |

| Bra020376 R | TGGAGACTTTGGAAGGATACT | ||

| Bra031210 F | ACGAGGCTCAGTCTCGTGGT | Response to water deprivation |

ODO |

| Bra031210 R | TCCGCTGCGGTATCCACCA | ||

| Bra031666 F | TGCCAAGGACAACAACTTGGACT | Lignin biosynthetic process |

HPD |

| Bra031666 R | AGTTGGTTGTAGGACTGGTCCA | ||

| Bol016209 F | TAACCTACCAGAAGCACGGT | Response to abscisic acid |

ODO |

| Bol016209 R | ACAACTTCAACGGTGCACGACT | ||

| Bol022348 F | AGGTACCTTACGAGTCTCGT | Response to karrikin | HPD |

| Bol022348 R | CACGAACCTGATAGAAGCTCGT | ||

| Bol026880 F | TGTAAGGCTACGAAGGGACAT | Defense response to fungus |

HPD |

| Bol026880 R | TCCAACATATCCATATGTCCGT | ||

| Bol026959 F | TAGCTCTTCCTCTTCAAGCGAT | Defense response to fungus |

ODO |

| Bol026959 R | TCCTTCTTCCTCTTCTCACCA | ||

| Bol041012 F | TGACACATTGTGGATGGAACT | Cellular hyperosmotic response |

ODO |

| Bol041012 R | GGCATACCAATCATTGGAACT | ||

| Bol044348 F | TACTACTGGACCTTTGGTGCT | Calcium ion transport |

HPD |

| Bol044348 R | GATCTTCATCTGAAGGTCACT |

Figure 7.

Genes with expression levels validated by qRT-PCR.

4. Discussion

Interspecific hybridization is an important approach to obtaining and utilizing novel agronomic traits from related species for crop improvement. Previous researches revealed strong heterosis between B. napus and B. rapa on biomass and seed yield [5–7]. Recently, Li et al. [24] reported that B. napus-like individuals in the F3 and F4 generations, from interspecific hybridization between B. napus and B. oleracea, showed diverse genetic variation relative to current B. napus and strong heterotic potential. We selected a number of backcrossed offspring derived from the F1 by being crossed with P1 (B. napus) and new traits such as wrinkle leaves, six sepals which different from their parents were observed in the progenies. In particular, we identified several lines which displayed high yield up to 4,500 kg per hectare in BC1F2 population. It suggested that the novel lines from interspecific hybridization between B. napus and B. rapa with high yield good quality can be potentially useful for oilseeds production in the near future.

Intraspecific hybrids of Arabidopsis thaliana [25, 26], rice [27–29], and maize [30, 31] revealed that there are both additive and nonadditive effects of gene expression in hybrids, and heterosis is strongly influenced by genetic differences between two parents. A transcriptome approach has been utilized to investigate the heterosis of intraspecific hybrids of A. thaliana, rice, maize [29, 30]. Our research of the transcriptomes from B. napus and B. rapa demonstrated the genetic effect of interspecies heterosis at the gene expression level. More genes specific to certain pathways in further experiments are needed to fully validate the heterotic association between the gene expression patterns and the target agronomic traits. In the present study, we found that both additive and dominance effects contributed to interspecies heterosis between B. napus and B. rapa. Analysis of the number of DEGs in hybrid and parental germplasm revealed that the nonadditive effect contributed more than the additive effect. Previous research reveals interspecies heterosis between B. napus and B. rapa through genetic analysis but the main focus was on phenotypic variation [6, 32]. Our study provided evidence of differential gene expression and shed new insights on the molecular mechanism for this heterosis in the interspecific hybrids.

Brassica species constitute an elite system for investigating the changes in genomic structure and functional divergence of duplicate genes in the process of hybridization and polyploidization among the diploid species and their amphidiploids [32, 33]. Subgenomes in Brassica species are designated with superscripts with An and Ar representing A genomes from B. napus and B. rapa, respectively [33]. We have shown intersubgenomic heterosis between Ar and An genomes, supporting work by others that show that such heterosis can be useful in creating genetic diversity and be used in breeding. Studies indicated that the midparent heterosis contributes intersubgenomic heterosis [8, 34, 35]. Therefore, the utilization of intersubgenomic heterosis can be creating genetic diversity and breeding. In the present study, we found that the nonadditive DEGs from the A genome in the hybrids mainly participated in metabolism and development, while those from the C genome were largely involved in stress resistance. It is likely that the neofunctionalization of subgenome contributes the heterosis or the genomic adaptation in hybrid. Recently, Li et al. [36] investigated the total homoeolog expression level of hexaploid wheat (AABBDD) and compared it to its ancestral parents T. turgidum (AABB) and Ae. tauschii (DD), finding that genes expressed from the AABB potentially participated in development and those from Ae. tauschii (DD) were more likely involved in adaptation. Differential contributions from the parental sources may also be occurring in the Brassica hybrids, and this may hint at the molecular mechanisms behind heterosis. Transposable elements (TEs) have major effects on different plant genomes and can significantly contribute differences in genome size of over 1,000-fold [37]. Recent sequencing of the B. rapa and B. oleracea genomes revealed that the amplification of TEs is one of the main factors inducing the difference in genome size [37]. The overall TEs in either Brassica genomes are expressed at very low levels, and the expression levels of different TE categories and families vary among different organs [38]. Recently, the variations in TE-associated sequences during the process of allopolyploidisation were detected between Brassica rapa (AA) and B. oleracea (CC), as well as in successive generations of self-pollinated progeny [39]. Our study revealed that the expression activities of TE categories or families were clearly modified in the hybrids between the two Brassica species, and different types of TEs showed different patterns of variation during the process of hybridization. Therefore, the association of activation and inactivation of TEs and of TE related genes expression in relation to heterotic gene expression needs to be further investigated.

5. Conclusions

Development of interspecific hybrids has been widely exploited for the heterosis breeding of Brassica crops. The interspecific hybrid between Brassica napus and B. rapa displayed obvious heterosis. In the present study, the comparative transcriptome analysis for the parents B. napus and B. rapa and its hybrid F1 was sequenced using the platform of Illumina/Solexa with de novo assemblage. The nonredundant unigenes were identified using B. rapa (A genome) and B. oleracea (C genome) as reference genomes. The nonadditively differentially expressed genes were potentially related to the heterosis. The results indicated that the differentially expressed genes in hybrids from the A genome mainly participated in metabolism and development, while those from the C genome were largely involved in stress resistance. The coexistence of multiple gene actions and transposable element-associated genes regulations in the hybrid were observed. The present study could be helpful for the better understanding of the mechanisms of heterosis, and a list of candidate genes will be used for future Brassica breeding.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Earmarked Fund for Modern Agro-industry Technology Research System of China, the National High Technology Research and Development Program “863” of China (2011AA10A104), and National Science and Technology Supporting Plan of China (2011BAD35B04), The Ministry of agriculture experimental observation of the upper reaches of the Yangtze River Oil Crop Science Station (09203020), and Sichuan Crop Breeding Community (2011NZ0098-5, 2011NZ0098-16, and 2011JYGC04-013) for the financial support.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Foley J. A., Ramankutty N., Brauman K. A., et al. Solutions for a cultivated planet. Nature. 2011;478(7369):337–342. doi: 10.1038/nature10452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nagaharu U. Genome analysis in Brassica with special reference to the experimental formation of B. napus and peculiar mode of fertilization. Japanese Journal of Botany. 1935;7:389–452. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abbadi A., Leckband G. Rapeseed breeding for oil content, quality, and sustainability. European Journal of Lipid Science and Technology. 2011;113(10):1198–1206. doi: 10.1002/ejlt.201100063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jesske T., Olberg B., Schierholt A., Becker H. C. Resynthesized lines from domesticated and wild Brassica taxa and their hybrids with B. napus L.: genetic diversity and hybrid yield. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2013;126(4):1053–1065. doi: 10.1007/s00122-012-2036-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu H. L. Genetics and Breeding in Rapeseed. Beijing, China: Chinese Agricultural Universities Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu R., Qian W., Meng J. Association of RFLP markers and biomass heterosis in trigenomic hybrids of oilseed rape (Brassica napus × B. campestris) Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2002;105(6-7):1050–1057. doi: 10.1007/s00122-002-1050-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fu D., Xiao M., Hayward A., et al. What is crop heterosis: new insights into an old topic. Journal of Applied Genetics. 2014;56(1):1–13. doi: 10.1007/s13353-014-0231-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Birchler J. A., Auger D. L., Riddle N. C. In search of the molecular basis of heterosis. Plant Cell. 2003;15(10):2236–2239. doi: 10.1105/tpc.151030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen Z. J. Genomic and epigenetic insights into the molecular bases of heterosis. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2013;14(7):471–482. doi: 10.1038/nrg3503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hofmann N. R. A global view of hybrid vigor: DNA methylation, small RNAs, and gene expression. Plant Cell. 2012;24(3, article 841) doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.240312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhai R., Feng Y., Wang H., et al. Transcriptome analysis of rice root heterosis by RNA-Seq. BMC Genomics. 2013;14, article 19 doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu S., Zhang F., Wang X., et al. Genetic diversity and marker-trait associations in a collection of Pak-choi (Brassica rapa L. ssp. chinensis Makino) Accessions. Genes and Genomics. 2014;32(5):419–428. doi: 10.1007/s13258-010-0033-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang X. L., Zhang L. G. Molecular cloning and expression of the male sterility-related CtYABBY1 gene in flowering Chinese cabbage (Brassica campestris L. ssp chinensis var. parachinensis) Genetics and Molecular Research. 2014;13(2):4336–4347. doi: 10.4238/2014.june.10.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang N., Li F., Chen B., et al. Genome-wide investigation of genetic changes during modern breeding of Brassica napus . Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2014;127(8):1817–1829. doi: 10.1007/s00122-014-2343-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin S., Dong H., Zhang F., et al. BcMF8, a putative arabinogalactan protein-encoding gene, contributes to pollen wall development, aperture formation and pollen tube growth in Brassica campestris . Annals of Botany. 2014;113(5):777–788. doi: 10.1093/aob/mct315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhan H., Zhang X., Li G., et al. Molecular characterization of a new wheat-Thinopyrum intermedium translocation line with resistance to powdery mildew and stripe rust. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2015;16(1):2162–2173. doi: 10.3390/ijms16012162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li R., Yu C., Li Y., et al. SOAP2: an improved ultrafast tool for short read alignment. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(15):1966–1967. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mortazavi A., Williams B. A., McCue K., Schaeffer L., Wold B. Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nature Methods. 2008;5(7):621–628. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Audic S., Claverie J.-M. The significance of digital gene expression profiles. Genome Research. 1997;7(10):986–995. doi: 10.1101/gr.7.10.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.RC Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ding H., Qin C., Luo X., et al. Heterosis in early maize ear inflorescence development: a genome-wide transcription analysis for two maize inbred lines and their hybrid. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2014;15(8):13892–13915. doi: 10.3390/ijms150813892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Custom Primers-OligoPerfect Designer. Carlsbad, Calif, USA: Invitrogen; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Du Z., Zhou X., Ling Y., Zhang Z., Su Z. AgriGO: a GO analysis toolkit for the agricultural community. Nucleic Acids Research. 2010;38(2):W64–W70. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li Q., Zhou Q., Mei J., et al. Improvement of Brassica napus via interspecific hybridization between B. napus and B. oleracea . Molecular Breeding. 2014;34(4):1955–1963. doi: 10.1007/s11032-014-0153-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang J., Tian L., Lee H.-S., et al. Genome-wide non-additive gene regulation in Arabidopsis allotetraploids. Genetics. 2006;172(1):507–517. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.047894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fujimoto R., Taylor J. M., Shirasawa S., Peacock W. J., Dennis E. S. Heterosis of Arabidopsis hybrids between C24 and Col is associated with increased photosynthesis capacity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109(18):7109–7114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204464109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ge X., Chen W., Song S., Wang W., Hu S., Yu J. Transcriptomic profiling of mature embryo from an elite super-hybrid rice LYP9 and its parental lines. BMC Plant Biology. 2008;8, article 114 doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-8-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wei G., Tao Y., Liu G., et al. A transcriptomic analysis of superhybrid rice LYP9 and its parents. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106(19):7695–7701. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902340106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Song G.-S., Zhai H.-L., Peng Y.-G., et al. Comparative transcriptional profiling and preliminary study on heterosis mechanism of super-hybrid rice. Molecular Plant. 2010;3(6):1012–1025. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssq046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoecker N., Keller B., Piepho H.-P., Hochholdinger F. Manifestation of heterosis during early maize (Zea mays L.) root development. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2006;112(3):421–429. doi: 10.1007/s00122-005-0139-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thiemann A., Fu J., Schrag T. A., Melchinger A. E., Frisch M., Scholten S. Correlation between parental transcriptome and field data for the characterization of heterosis in Zea mays L. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2010;120(2):401–413. doi: 10.1007/s00122-009-1189-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qian W., Liu R., Meng J. Genetic effects on biomass yield in interspecific hybrids between Brassica napus and B. rapa . Euphytica. 2003;134(1):9–15. doi: 10.1023/a:1026180823401. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cheng F., Mandáková T., Wu J., Xie Q., Lysak M. A., Wang X. Deciphering the diploid ancestral genome of the mesohexaploid Brassica rapa . Plant Cell. 2013;25(5):1541–1554. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.110486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zou J., Zhu J., Huang S., et al. Broadening the avenue of intersubgenomic heterosis in oilseed Brassica . Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2010;120(2):283–290. doi: 10.1007/s00122-009-1201-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Qian W., Chen X., Fu D., Zou J., Meng J. Intersubgenomic heterosis in seed yield potential observed in a new type of Brassica napus introgressed with partial Brassica rapa genome. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2005;110(7):1187–1194. doi: 10.1007/s00122-005-1932-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li A., Liu D., Wu J., et al. mRNA and small RNA transcriptomes reveal insights into dynamic homoeolog regulation of allopolyploid heterosis in nascent hexaploid wheat. Plant Cell. 2014;26(5):1878–1900. doi: 10.1105/tpc.114.124388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang X., Wang H., Wang J., et al. The genome of the mesopolyploid crop species Brassica rapa . Nature Genetics. 2011;43(10):1035–1039. doi: 10.1038/ng.919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhao M. X., Zhang B., Liu S. L., Ma J. Transposon expression and potential effects on gene regulation of Brassica rapa and B. oleracea genomes. Hereditas. 2013;35(8):1014–1022. doi: 10.3724/sp.j.1005.2013.01014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.An Z., Tang Z., Ma B., et al. Transposon variation by order during allopolyploidisation between Brassica oleracea and Brassica rapa . Plant Biology. 2014;16(4):825–835. doi: 10.1111/plb.12121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]