Abstract

The ultimate goal of muscular dystrophy gene therapy is to treat all muscles in the body. Global gene delivery was demonstrated in dystrophic mice more than a decade ago using adeno-associated virus (AAV). However, translation to affected large mammals has been challenging. The only reported attempt was performed in newborn Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) dogs. Unfortunately, AAV injection resulted in growth delay, muscle atrophy and contracture. Here we report safe and bodywide AAV delivery in juvenile DMD dogs. Three ∼2-m-old affected dogs received intravenous injection of a tyrosine-engineered AAV-9 reporter or micro-dystrophin (μDys) vector at the doses of 1.92–6.24 × 1014 viral genome particles/kg under transient or sustained immune suppression. DMD dogs tolerated injection well and their growth was not altered. Hematology and blood biochemistry were unremarkable. No adverse reactions were observed. Widespread muscle transduction was seen in skeletal muscle, the diaphragm and heart for at least 4 months (the end of the study). Nominal expression was detected in internal organs. Improvement in muscle histology was observed in μDys-treated dogs. In summary, systemic AAV gene transfer is safe and efficient in young adult dystrophic large mammals. This may translate to bodywide gene therapy in pediatric patients in the future.

Introduction

Localized gene transfer has resulted in miraculous improvements for diseases that affect a single organ (1,2). However, such therapies will unlikely change the disease course when afflicted tissues are distributed throughout the body as in the case of Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), a lethal X-linked muscle disease caused by dystrophin deficiency (3). The ultimate cure for DMD requires bodywide gene therapy. Vascular delivery has the potential of global muscle transduction. However, infusion of trillions of viral particles may lead to unexpected responses and even fatal complications (4,5).

The first successful whole body gene transfer was conducted in rodent models of muscular dystrophy more than a decade ago using adeno-associated virus (AAV). Investigators from several laboratories demonstrated that a single intravascular injection of AAV-6, 8 or 9 reached every muscle in the body (6–8). More recently, systemic AAV delivery was achieved in skeletal and cardiac muscle of aged dystrophic mice (9–11). Despite marvelous results in rodents, bodywide gene transfer has been problematic in diseased large mammals (12).

Systemic gene transfer in a large mammal was initially tested in normal neonatal dogs (13,14). Intravenous injection of 2 × 1014 viral genome (vg) particles/kg of AAV-9 resulted in broad skeletal muscle transduction in puppies (13). The same technique was subsequently found to be effective for other AAV serotypes (15–17). In these studies, persistent expression was achieved for up to 1 year (the end of the study) at a dose as high as 9.7 × 1014 vg particles/kg without any toxicity. Unfortunately, translation to the canine DMD model has met with great difficulties (18). Kornegay et al. delivered 1.5 × 1014 vg particles/kg of AAV-9 to two 4-day-old affected puppies through the jugular vein. Surprisingly, treated dogs developed massive inflammatory myopathy, contracture and growth retardation (5). The results of Kornegay et al. question the feasibility of systemic AAV gene therapy in dystrophic large mammals.

Recent studies suggest that replacing surface exposed tyrosine residue on AAV capsid may reduce immunogenicity and enhance transduction (19,20). We tested Y731F AAV-9, a surface tyrosine mutated AAV-9 variant in adult DMD dogs and observed robust expression following direct muscle injection (21). Here we tested the hypothesis that Y731F AAV-9 can result in whole body muscle transduction in juvenile DMD dogs. A human placental alkaline phosphatase (AP) reporter vector or a potentially therapeutic μDys vector were injected intravenously at a dose up to 6.24 × 1014 vg particles/kg under transient or sustained immune suppression. All three dogs tolerated injection and immune suppression well. No adverse reactions were observed. Necropsy at the age of 5.5–6 months revealed robust skeletal muscles transduction throughout the body and widespread gene transfer in the heart. Our results demonstrated for the first time that systemic AAV delivery in a diseased large mammal is safe and effective. Similar approaches may be used to treat pediatric muscular dystrophy patients in the future.

Results

A single intravenous injection of Y731F AAV-9 resulted in efficient skeletal muscle transduction throughout the body and widespread gene transfer in the heart

Dog Bouchelle was injected with 1.92 × 1014 vg particles/kg (7.09 × 1014 vg particles total) of a Rous sarcoma virus (RSV) promoter-driving AP reporter AAV vector (Table 1). This dog also received 5-week transient immune suppression (Fig. 1A) (21,22).

Table 1.

Experimental dog summary

| Dog name | Bouchelle | Stephan | Brooke |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dystrophin gene mutation | Intron 19 insertion | Intron 6 point mutation | Intron 13 insertion |

| Gender | Male | Female | Male |

| Body weight at injection (kg) | 3.7 | 3.5 | 3.2 |

| Body weight at necropsy (kg) | 10.6 | 10.6 | 11.3 |

| Promoter | RSV | CMV | CMV |

| Transgene | Human AP reporter gene | Canine µ-dystrophin | Canine µ-dystrophin |

| Total AAV injected (vg particles) | 7.09 × 1014 | 1.77 × 1015 | 2.0 × 1015 |

| Vector dose (vg particles/kg BW) | 1.92 × 1014 | 5.04 × 1014 | 6.24 × 1014 |

| Vector volume (ml/kg BW) | 4.9 | 5.7 | 6.2 |

| Age at AAV injection (month) | 2.0 | 1.8 | 1.8 |

| Age at biopsy (month) | 3.0 | 2.8 | 2.8 |

| Age at necropsy (month) | 5.5 | 5.3 | 5.8 |

Figure 1.

Experimental protocol, growth curve, blood biochemistry and biopsy results. (A) Schematic overview of the study. Arrow, AAV injection; open arrowhead, biopsy; filled arrowhead, necropsy; filled box, the dog is under immune suppression. (B) The growth curve of individual dogs. The colony average is shown in gray (N ≥ 70). (C) Selected blood biochemistry results. Complete data can be found in Supplementary Material, Table S1. Dotted gray lines, the maximal and minimal values for age-matched untreated DMD dogs in our colony (N = 31). Solid gray line, the average value of age-matched untreated DMD dogs in our colony (N = 31). (D) Representative AP histochemical staining photomicrographs and dystrophin immunofluorescence staining photomicrographs from the CT and BF muscles obtained at biopsy. (E) Vector genome copy number quantification from biopsied muscle samples.

The injection procedure went smoothly. The dog tolerated immune suppression and large-dose AAV well. No change was noted in the activity, behavior, food/water consumption and vital signs of the dog throughout the entire experiment. The body weight also showed stable growth (Table 1 and Fig. 1B). Compared with that of the baseline (before the start of immune suppression), post-injection blood chemistry was in general unremarkable (Fig. 1C, and Supplementary Material, Table S1). There was a slight increase in blood urine nitrogen (but still within the normal range), a trend of higher creatine (but still within the normal range), and transient elevation of blood AP (Fig. 1C). However, we did not detect any clinically meaningful events. One-month muscle biopsy showed strong AP expression and abundant vector genomes (Fig. 1D and E). Bouchelle was euthanized at 3.5 months after gene transfer. AAV transduction was evaluated by histochemical staining, enzymatic activity assay and vector genome quantification (Figs 2 and 3). We observed widespread AP expression and vector genome in every muscle (Fig. 2). On average, ∼25% (range, 5–80%) myofibers were transduced. The extensor carpi ulnaris (ECU) muscle had the lowest expression (AP positive myofiber, 5%; AP activity, 0.84 μM/μg). The highest transduction was seen in the extraocular muscle (EOM) (AP positive myofiber, 80%; AP activity, 215 μM/μg; AAV genome copy number, 26.2 copies/diploid genome). Respiratory failure and heart failure are the leading causes of death in DMD. Encouragingly, high-level AP expression was detected in the diaphragm, intercostal muscle and heart (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

A single intravenous injection of an AP reporter AAV vector leads to global muscle transduction in a juvenile dystrophic dog. (A) Representative full-view AP staining photographs of the indicated muscle. (B) Representative AP histochemical staining photomicrographs of the heart and skeletal muscles. (C) AP activity. (D) AAV vector genome quantification. Abbreviations for the heart: LA, left atrium; LVa, left ventricle anterior; LVp, left ventricle posterior; LVx, left ventricle apex; Pap, papillary muscle; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle; Sep, interventricular septum. Abbreviations for the diaphragm: Dia-c, diaphragm costal part; Dia-l, diaphragm lumbar part; Dia-s, diaphragm sternal part. Abbreviations for skeletal muscles: BB, biceps brachii; BF, biceps femoris; Bra, brachialis; CT, cranial tibialis; Del, deltoideus; ECU, extensor carpi ulnaris; FCR, flexor carpi radialis; FCU, flexor carpi ulnaris; FD, flexor digitorum; Gas, gastrocnemius; Gra, gracilis; Ics, intercostalis; Lat, latissimus; Pec, pectoralis; Pro, pronator; Ssp, supraspinatus; TB, triceps brachii; Ter, Teres; Ton, tongue; VL, vastus lateralis; VM, vastus medialis.

Figure 3.

Systemic Y731F AAV-9 injection results in minimal transgene expression in internal organs despite robust expression in peripheral nerve, spinal cord and microvasculature. (A) Representative HE and AP histochemical staining photomicrographs of the liver, testis and kidney. (B) Representative HE and AP histochemical staining photomicrographs of the pancreas and lung. Asterisk, smooth muscle. (C) Representative AP histochemical staining photomicrographs of muscle revealing strong staining in the microvasculuture (red arrows). All arrow bars stand for 100 μm. (D) Representative AP histochemical staining photomicrographs of the sciatic never. Left panel, full-view image; right panel, high magnification image. (E) Representative HE and AP histochemical staining photomicrographs of a small never branch (arrow) inside muscle, spinal cord (gray matter and white matter), hippocampus, cerebrum and cerebellum. (F) AP activity and AAV vector genome quantification in the indicated tissues.

Systemic Y731F AAV-9 injection resulted in minimal expression in internal organs

On histochemical staining, we did not detect AP expression in the liver and testis (Fig. 3A). In the kidney, we found very few AP positive cells in the glomerulus (Fig. 3A). In the lung, AP positive cells were seen in alveolar cells. In the pancreas, we noticed strong AP expression in smooth muscle and some expression in acini (Fig. 3B). However, minimal expression was observed in islets of Langerhans (Supplementary Material, Fig. S1). Robust transduction was observed in the microvasculature in muscles (Fig. 3C). The peripheral nerves (including large nerves such as sciatic nerve and small nerve branches inside muscle) showed very high AP expression (Fig. 3D and E). The spinal cord was also transduced at high efficiency (Fig. 3E). Some AP expression was seen in the hippocampus, but minimal AP expression was detected in the cerebrum and cerebellum (Fig. 3E). Consistent with AP staining results, the AP activity assay in tissue lysate revealed minimal expression in internal organs except for the sciatic never and spinal cord (Fig. 3F). Despite the dramatic difference in AP expression, surprisingly, similar amount of the AAV genome was detected in internal organs (Fig. 3F). In fact, the AAV genome copy number in internal organs was quite comparable to that in muscles (Figs 2D and 3F).

Bodywide gene transfer was achieved with a μDys vector

Next, we delivered a μDys AAV vector to affected dogs Stephan (5.04 × 1014 vg particles/kg, 1.77 × 1015 vg particles total) and Brooke (6.24 × 1014 vg particles/kg, 2.00 × 1015 vg particles total) (Table 1). In this vector, a flag-tagged codon-optimized canine ΔR2–15/ΔR18-19/ΔR20-23/ΔC μDys gene was expressed from the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter (21). Immune suppression was extended until the end of study in these two dogs. Stephan and Brooke tolerated AAV administration and immune suppression well. Brooke showed normal growth as expected. Stephan showed a slower growth between weeks 8 and 10, but its growth curve returned to the levels of Bouchelle and Brooke by week 14. No clinically meaningful adverse reactions were noted. Post-injection blood examination showed a profile similar to that of Bouchelle (Fig. 1C, and Supplementary Material, Table S1). Essentially, all laboratory parameters were within the range of other affected dogs in our colony. One-month biopsy revealed robust μDys expression (Fig. 1D). Necropsy was performed at 3.5 (Stephan) and 4 (Brooke) months after injection. Consistent with the findings of Bouchelle, we observed efficient gene transfer in striated muscles all over the body in Stephan and Brooke at necropsy (Fig. 4). Interestingly, despite a 25% difference in the vector dose (5.04 × 1014 vg particles/kg in Stephan versus 6.24 × 1014 vg particles/kg in Brooke), we observed quite comparable levels of transduction in two dogs. Immunostaining with a flag antibody revealed correct sarcolemmal localization of μDys (Fig. 4A and B). Quantitatively, μDys-positive cells reached ∼25% (range, 5–60%) (Fig. 4E). Similar to Bouchelle (Fig. 2), the EOM showed the highest transduction (50–60%) while the ECU muscle had the least μDys expression (5%) (Fig. 4A, B and E). Respiratory muscles (diaphragm, intercostal muscle and abdominal muscle) were also highly transduced with 23–48% myofibers showed μDys expression. Western blot with a dystrophin antibody confirmed μDys expression at the expected size in striated muscles (Fig. 4F and G). The AAV vector genome was detected in every muscle (Fig. 3G and H). No μDys was detected in internal organs (Supplementary Material, Fig. S2).

Figure 4.

A single intravenous injection results in bodywide muscle expression of a flag-tagged μDys gene in young adult dystrophic dogs. (A) Representative flag immunostaining of skeletal muscles from dog Stephan. (B) Representative flag immunostaining of skeletal muscles from dog Brooke. (C) Representative flag immunostaining of the heart from dog Stephan. (D) Representative flag immunostaining of the heart from dog Brooke. (E) Percentage of μDys-positive myofibers. (F) Representative dystrophin western blot from dog Stephan. Positive and negative western blot controls are ECU muscles with and without μDys AAV injection, respectively. (G) Representative dystrophin western blot from dog Brooke. Positive and negative western blot controls are ECU muscles with and without μDys AAV injection, respectively. (H) AAV vector genome quantification. Abbreviations for skeletal muscles: Abd, abdominus; BB, biceps brachii; BF, biceps femoris; Bra, brachialis; CT, cranial tibialis; Del, deltoideus; Dia, diaphragm; ECU, extensor carpi ulnaris; EDL, extensor digitorum longus; EOM, extraocular muscle; FCR, flexor carpi radialis; FCU, flexor carpi ulnaris; fl-Dys, full-length dystrophin; Gas, gastrocnemius; Gra, gracilis; Ics, intercostalis; Pec, pectoralis; Pro, pronator; Sem, semitendinosus; Ssp, supraspinatus; TB, triceps brachii; Ter, Teres; Ton, tongue; VL, vastus lateralis; VM, vastus medialis. Abbreviations for the heart: LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; LVa, left ventricle anterior; LVp, left ventricle posterior; LVx, left ventricle apex; Pap, papillary muscle; Papa, anterior papillary muscle; Papp, posterior papillary muscle; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle; Rvca, caudal part of the right ventricle; RVcr, cranial part of the right ventricle; Sep, interventricular septum.

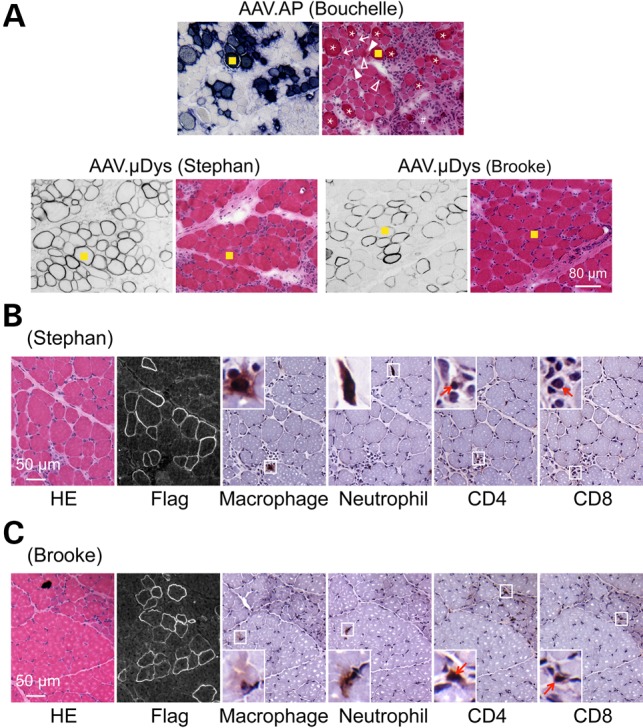

μDys expression reduced histopathology

In Bouchelle, the dog that received the AP reporter vector, all muscles showed classic dystrophic pathology such as abundant inflammatory cell infiltration, dark-stained hyalinized/hypercontracted myofibers, necrotic myofibers, angulated myofibers, large hypertrophic myofibers, excessively small myofibers and increased endomysial and perimysial connective tissue deposition (Fig. 5A, and Supplementary Material, Fig. S3). For dogs that received the μDys vector (Stephan and Brooke), two different profiles were observed. The majority of muscles had ≥25% μDys-positive cells (such as the abdominal muscle, biceps femoris (BF), cranial tibialis (CT) and triceps brachii (TB)). These muscles appeared to have relatively uniformed myofiber size and much less inflammation (Fig. 5). Hyalinized/hypercontracted myofibers were rarely detected in these muscles. On detailed immunohistochemical characterization, we observed very few macrophages, neutrophils, CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells (Fig. 5B and C). Further, these inflammatory cells were restricted to small loci (Fig. 5B and C). A different profile was seen in the ECU muscle. This muscle had the lowest expression (5%) (Fig. 4E). Its histology was identical to that of untreated or AAV.AP injected DMD dogs (data not shown). On in situ force measurement, we did not see any improvement (data not shown).

Figure 5.

μDys expression ameliorates muscle pathology in young adult dystrophic dogs. (A) Representative muscle serial sections stained for transgene expression (AP staining for AAV.AP injected dog Bouchelle and flag immunostaining for AAV.μDys injected dog Stephan and Brooke) and general morphology (HE staining). The yellow square marks the same myofiber in serial sections. Asterisk, heavily stained hylinated/hypercontracted myofiber; arrow, angular myofiber; solid arrowhead, necrotic myofiber; open arrowhead, degenerative myofiber; pound sign, fibrotic tissue deposition. An enlarged view of the HE stained photomicrography of the AAV.AP infected dog is shown in Supplementary Material, Figure S3. (B) Representative HE staining, Flag immunostaining and immune cell immunohistochemical staining on muscle serial sections from AAV μDys injected dog Stephan. Insets are the enlarged view of the boxed areas. Arrow, CD4+ or CD8+ T cell. (D) Representative HE staining, Flag immunostaining and immune cell immunohistochemical staining on muscle serial sections from AAV μDys injected dog Brooke. Insets are the enlarged view of the boxed areas. Arrow, CD4+ or CD8+ T cell.

To study overall improvement in μDys-treated dogs, we examined the serum CK level but did not see a consistent trend (Supplementary Material, Table S1, and Fig. S4).

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated for the first time that systemic AAV gene transfer is feasible in a young adult dystrophic large mammal. Bodywide delivery to skeletal and cardiac muscle was confirmed in three affected dogs using two different AAV vectors. Notably, efficient whole body muscle transduction was not associated with any serious complications. All treated dogs tolerated gene transfer well and maintained the expected body weight growth (Fig. 1B). This is encouraging considering the fact that up to 2 × 1015 vg AAV particles were delivered to dogs that have ongoing massive muscle degeneration, necrosis and inflammation.

Systemic gene delivery has been a long-standing barrier in the field of gene therapy. This barrier was partially broken a decade ago when a series of studies from several laboratories showed robust whole body gene transfer in rodents with AAV-6, 8 and 9 at the dose of ∼0.5–2 × 1014 vg particles/kg body weight (6–8,23). Yet, scaling-up systemic AAV delivery to large mammals remains a formidable challenge (18). There are several obstacles. First, the thick basement membrane in large mammals may significantly limit vector spread from the microvasculature. It is thus expected that systemic transduction efficiency in large mammals will be reduced compared with that of mice. In support of this notion, the vector dose (1 × 1014 vg/kg) that leads to bodywide gene transfer in adult mice yields much lower transduction in newborn dogs (8,13). The second obstacle is the large-scale AAV production. Besides the high cost and intense labor, negligible contaminants will become a significant safety concern when trillions of viral particles are administrated. A third obstacle is our body's response to the infused virus. Unexpected inflammatory and/or immune response may lead to fatal complications as demonstrated in the tragic death of Jesse Gelsinger in a 1998 clinical trial and in the premature termination of the study reported by Kornegay et al. (4,5). Lastly, although AAV is much less immunogenic than vectors based on some other viruses (such as adenovirus), affected dogs often mount a furious immune response to AAV. This may further worsen untoward immune rejection to the AAV vector and/or AAV transduced myofibers (1,24). Taken together, development of systemic AAV gene transfer in adult dystrophic dogs represents an unprecedented challenge.

In light of the clinical need for bodywide gene therapy for DMD, we explored the safety and feasibility of intravenous AAV injection in the canine model, the best large animal model for DMD (25). To gain a comprehensive view on both muscle and non-muscle gene transfer, we first tested an AP reporter vector at a dose close to the effective dose we have used in normal neonatal puppies (∼2 × 1014 vg/kg) (Table 1) (13,16). Consistent with the results of our newborn dog studies (13,16), single intravenous injection yielded bodywide skeletal muscle transduction in the juvenile DMD dog (Fig. 2). In newborn puppies, saturated transduction was observed in every skeletal muscle (13,16). However, in the young adult dystrophic dog, only the EOM showed near complete transduction (80%). We have previously found that myocardium expression from AAV-9 and Y731F AAV-9 was selectively blocked at some undefined post-entry steps in newborn dogs (13,16,17). In these published studies, we detected the AAV genome in the heart but AP positive cells were rarely observed. In striking contrast, efficient AP expression was seen in the heart of the young adult dystrophic dog suggesting that certain age and/or disease-related changes in the cardiomyocytes may have facilitated cardiac AAV-9 transduction in the juvenile DMD dog.

The cellular mechanism of systemic AAV muscle transduction is poorly understood. However, it is generally believed that viral particles have to cross the blood vessels to reach muscle. Consistent with this notion, we observed efficient microvasculature transduction in muscle (Fig. 3E). It has been shown that AAV-9 can cross the blood–brain barrier and transduce the central nerve system (26,27). We indeed observed a high-level transduction in the spinal cord. Intriguingly, there was nominal AP expression in the cerebrum and cerebellum (Fig. 3D). Nevertheless, the peripheral nerves (including large nerves such as the sciatic nerve and small nerve branches such as these inside muscle) were effectively transduced (Fig. 3C and D).

Following systemic gene transfer, a significant amount of viral particles is often sponged in the liver. Zincarelli et al. compared nine AAV serotypes (AAV-1 to AAV-9) in mice and found that AAV-9 yielded the highest expression in the liver. In sharp contrast, we did not see strong liver expression in either normal newborn puppies or adult dystrophic dogs (Fig. 3) (13,15–17). There was also minimal expression in the testis, kidney, pancreas and lung (Fig. 3). Interestingly, we detected a high abundance of the AAV genome in internal organs (Fig. 3). Our results suggest that there may exist important species differences in AAV transduction. The inconsistency between the AAV genome copy number and the level of transgene expression in the liver is somewhat unexpected. The exact mechanisms behind this peculiar finding remain to be dissected. We speculate that it may relate to promoter silencing or inefficient conversion of the single-stranded AAV genome to the double stranded transcription competent form in the dog liver.

To confirm and expand our findings with the reporter AAV vector, we next performed a dose escalation study with a μDys vector in two affected dogs. One dog received a total of 1.77 × 1015vg AAV particles (5.04 × 1014 vg/kg) and the other received 2 × 1015 vg AAV particles (6.24 × 1014 vg/kg) (Table 1). These doses are lower than the highest does we have delivered to newborn normal dogs (9.65 × 1014 vg/kg) (17). However, as to our knowledge, they are the highest AAV doses ever been delivered to a diseased large mammal. Considering the potential immunogenicity of dystrophin (24,28), we extended immune suppression to the end of the study (Fig. 1A). Despite prolonged immune suppression and the increased AAV dose, we did not see adverse reactions in either dog. Blood examination did not show any evidence of liver or kidney damage (Fig. 1C, and Supplementary Material, Table S1). Together with the results of the AP vector injected dog, we conclude that there is minimal risk for systemic AAV gene transfer in adolescent dystrophic dogs.

To verify bodywide muscle transduction in μDys vector injected dogs, we performed immunostaining and western blot (Fig. 4). These studies revealed the correct sarcolemmal localization and expected molecular size of μDys (Fig. 4). Consistent with what we saw in the AP vector injected dog, widespread μDys expression was detected in every muscle including the heart (Fig. 4). Although there were muscle-to-muscle differences, on average transduction efficiency reached ∼25%.

The dog Brooke was injected with a dose 25% greater than what was administrated to the dog Stephan (Table 1). We initially expected Brooke to have higher expression. However, this turned out not to be the case. On biopsy, Stephan seemed to have a slightly better expression and it also had more AAV genome copy (Fig. 1). The necropsy samples from Brooke's skeletal muscle, in general, had expression higher than those from Stephan's (Fig. 4). But Stephan appeared to have a better expression in the heart (Fig. 4). Interestingly, compared with Stephan, Brooke had a lower AAV genome copy number in most skeletal muscle and heart samples. We suspect that individual differences (such as gender, body weight at injection, vector dose, necropsy age and other yet unknown factors) may have contributed to these observations.

The EOM consistently showed the highest expression in all three treated dogs. The exact mechanism(s) underlying preferential EOM transduction is yet to be elucidated. But it should be pointed out that this muscle indeed carries some unique biological features. For example, it is the only muscle in the dog body with the type IIB myofiber (29) (Duan D, unpublished observation).

In the neonatal study conducted by Kornegay and colleagues, dogs were not administrated with immune suppressive drugs. We have previously shown that transient immune suppression is necessary to achieve efficient local AAV transduction in DMD dog muscles (21,22). Based on the same premise, we applied transient immune suppression in this study (Fig. 1A). Interestingly, two recent reports showed effective AAV-1 and AAV-8 delivery of an oligonucleotide via regional intravascular administration in dystrophic dogs without using immunosuppression (30,31). Future side-by-side comparison is needed to clarify the role of the AAV serotype (AAV-1 and AAV-8 versus AAV-9) and the transgene product (oligonucleotides versus proteins) in vascular delivery in DMD dogs.

Since our long-term goal is systemic DMD gene therapy, we examined muscle pathology in all three injected dogs. As expected, delivery of a reporter gene AAV vector yielded no protection (Fig. 5A). The muscle still displayed characteristic dystrophic features. Two dogs received μDys therapy (Fig. 4). Different levels of mosaic expression were observed in various muscles in these dogs. The extensor carp ulnaris muscle had 5% μDys-positive myofibers. Neither morphology nor function was improved in this muscle. However, we noticed an encouraging trend of pathology amelioration in muscles that had μDys expression in more than 25% myofibers (Fig. 5). This result is consistent with the reports from other groups (30–34). Collectively, these data suggest that threshold non-uniform dystrophin expression can protect muscle. Despite histology improvement in many muscles, we did not see consistent reduction in serum creatine kinase. This could either because not all muscles were protected at the current doses or because the sample size is too small in our study. Future large-scale high-dose studies are warranted to thoroughly evaluate whole body μDys therapy in dystrophic dogs. Alternatively, other AAV serotypes should be explored to identify capsids that are more potent. It should also be pointed out that we have only followed AAV injected dogs for 3–3.5 months. Future long-term studies are warranted to assess the extent and persistence of systemic delivery in affected dogs.

In summary, we have demonstrated for the first time that intravenous Y731F AAV-9 administration can lead to efficient bodywide muscle transduction in young adult dystrophic dogs. The procedure is safe at the dose as high as 6.24 × 1014 vg particles/kg body weight (2 × 1015 vg particles per dog). While our study has opened the door to the possibility of bodywide AAV μDys gene therapy in young DMD patients in the future, additional works are needed to assess long-term safety and efficacy. Nevertheless, preliminary reports from systemic AAV-9 delivery in spinal muscular atrophy patients have yielded encouraging safety data (trial # NCT02122952) supporting continuous development of systemic AAV gene therapy for human diseases.

Materials and Methods

Animals

All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committees of the University of Missouri and were in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines. Three dystrophin-deficient dogs were used in this study (Table 1). All three dogs were seronegative for AAV-9 before injection. Each dog carried a different null mutation in the dystrophin gene (18). Specifically, the dog Bouchelle had a repetitive element insertion in the intron 19 of the dystrophin gene. This insertion introduced a nonsense mutation, which abolished dystrophin expression (18). In the dog Stephan, a point mutation in intron 6 disrupted dystrophin RNA splicing and the resulting transcript contained frame-shift mutation and a premature stop codon (35). In the dog Brooke, the long interspersed repetitive element-1 was inserted in the intron 13 of the dystrophin gene. Insertion created a new exon containing an in-frame stop codon (36). All experimental dogs were generated by artificial insemination and were on a mixed genetic background of golden retriever, Labrador retriever, beagle and Welsh corgi. The genotyping was determined by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) as we previously described (36,37).

Recombinant Y731F tyrosine mutant AAV-9 production and gene delivery

The Y731F AAV-9 capsid-packaging construct has been published before (21,38). The AP reporter vector was published before (13,16). In this vector, the ubiquitous RSV promoter controls AP expression. This plasmid has been described previously. The canine micro-dystrophin AAV stock (CMV.μDys) was produced using our published construct pSJ46 (21). In the CMV.μDys vector, the codon-optimized canine ΔR2-15/ΔR18-19/ΔR20-23/ΔC microgene was expressed under the control of the CMV promoter (21). Recombinant endotoxin-free AAV vectors were generated using the triple plasmids transfection method we described before (39). Viral titer was determined using the Fast SYBR Green Master Mix kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) by real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) in an ABI 7900 HT qPCR machine (Applied Biosystems). For RSV.AP virus, the forward primer for viral titer quantification was 5′-GGTTGTACGCGGTTAGGAGT and the reverse primer was 5′-GGCATGTTGCTAACTCATCG. This primer set amplified a fragment in the RSV promoter. For CMV.μDys virus, the titer was determined by qPCR using primers that amplified exons 69 and 70 in the dystrophin CR domain. The forward primer is 5′-TTTTCTGGTCGAGTTGCAAAAG. The reverse primer is 5′-CCATGTTGTCCCCCTCTAAGAC.

Immune suppression

Immune suppression was applied to experimental dogs using cyclosporine (Neoral, 100 mg/ml; Novartis, East Hanover, NJ; NDC 0078-0274-22) and mycophenolate mofetil (CellCept, 200 mg/ml; Genentech, South San Francisco, CA; NDC 0004-0261-29) (21,22). Cyclosporine was administered orally at the dose of 10–20/mg/kg/day to achieve a whole blood trough level of 100–200 ng/ml. The cyclosporine level was measured at the Clinical Pathology Laboratory in the University of Missouri Hospital (Columbia, MO). The blood trough level was achieved at ∼6 days after starting cyclosporine. Mycophenolate mofetil was administered orally twice a day at the dose of 20 mg/kg (40 mg/kg/day). Immune suppression was started at 1 week prior to AAV injection. Immune suppression was continued for 4 weeks after AAV injection for Bouchelle and throughout the entire experiment for Stephan and Brooke (Fig. 1).

Gene delivery, muscle biopsy and dog necropsy

Systemic Y731F AAV-9 delivery was performed in conscious dogs by a single intravenous injection through the cephalic vein (Table 1). Biopsy was performed on the BF and CT at 1 month after AAV injection (14). Necropsy was performed at 3.5 months post-injection for Bouchelle and Stephan and 4 months post-injection for Brooke. During necropsy, major skeletal muscles from the head (EOM, temporalis, tongue), neck (sternocephalicus), shoulder (deltoideus, supraspinatus), thorax (intercostal muscle, pectoralis), back (latissimus, teres, trapezius), abdomen (abdominal rectus), forelimb (biceps brachii, brachialis, extensor carpi radialis, ECU, extensor digitorum communis, flexor carpi radialis, flexor carpi ulnaris, flexor digitorum, pronator, TB) and hind limb (BF, cranial sartorius, CT, extensor digitorum lateralis, extensor digitorum longus, gastrocnemius, gracilis, quadriceps, rectus femoris, semimembranosus, semitendinosus, vastus lateralis and vastus medialis) as well as the diaphragm (sternal, costal and lumbar part), heart (right and left atria, right and left ventricles, papillary muscles and interventricular septum) and internal organs (liver, pancreas, spleen, lung, kidney, gonad, spinal cord, brachial plexus, sciatic nerve, cerebrum, cerebellum and hippocampus) were harvested. Two pieces of samples were collected from each tissue. One piece was frozen in liquid nitrogen-cooled isopentane in optimal cutting temperature media for cryosection and histological examinations. The other piece was snap frozen in liquid nitrogen for genomic DNA and protein extraction.

Blood chemistry

Blood was drawn from experimental subjects before the start of immune suppression (baseline data) and periodically throughout the experiment (Supplementary Material, Table S1). The laboratory biochemical test was performed at the Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Laboratory in the University of Missouri Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital (Columbia, MO).

Histological examination of AP reporter gene expression

AP histochemical staining was carried out on 8-µm-thick cryosections as we described before (13,14,22). Briefly, tissue sections were fixed in 0.5% glutaraldehyde for 10 min. After washing with 1 mM MgCl2, slides were incubated at 65°C for 45 min to inactivate endogenous AP activity. Slides were subsequently washed in a pre-staining buffer containing 100 mM Tris–HCl, pH 9.5, 50 mM MgCl2, 100 mM NaCl. Finally, slides were stained in the freshly prepared AP staining solution (165 mg/mL 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate-p-toluidine, 330 mg/ml nitroblue tetrazolium chloride, 50 mM levamisole) for 5–20 min. Cryosections from an uninfected dog (Frank) were used as negative controls for AP staining (13).

Examination of AP activity assay in tissue lysate

Total protein lysate was extracted as we described before (14). Protein concentration was determined using the DC protein assay kit (Bio-Rad). AP activity was measured by a colorimetric method using the Stem TAGTM alkaline phosphatase activity assay kit (Cell Biolabs, San Diego, CA). Prior to the assay, endogenous AP activity was inactivated by incubating the lysate at 65°C for 1 h.

Examination of μDys expression by immunofluorescence staining

Codon-optimized flag-tagged canine ΔR2-15/ΔR18-19/ΔR20-23/ΔC μDys was revealed with an anti-FLAG M2 antibody (1:400; Sigma). μDys expression was also confirmed with a dystrophin C-terminal Dys-2 epitope specific antibody (1:20; Novocastra, Newcastle, UK).

Western blot

Whole muscle lysate was loaded on an 8% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel, and protein was transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. Dystrophin was detected with an antibody against the Dys2 epitope (1:100; Novocastra). The full-length dystrophin protein migrated at 427 kD. The canine ΔR2-15/ΔR18-19/ΔR20-23/ΔC μDys protein migrated at 140 kD.

Vector genome copy number determination

Genomic DNA was extracted from freshly frozen tissue samples. The AAV genome copy was determined using the Fast SYBR Green Master Mix kit (Applied Biosystems) by qPCR in an ABI 7900 HT qPCR machine. A set of primers located within the AP gene was employed to quantify the vg copy number in Bouchelle. The forward primer is 5′-GACTGAGCCCATGACACCAA. The reverse primer is 5′-CATCTGTCTCGACCCCACTG. For Stephan and Brooke, we used a set of primers that amplified a 119 bp fragment in the CMV early enhancer. The forward primer is 5′-TTACGGTAAACTGCCCACTTG. The reverse primer is 5′-CATAAGGTCATGTACTGGGCATAA.

In situ muscle force assay

Prior to necropsy, the contractility of the ECU muscle was measured according to our published protocol (21,40).

Supplementary Material

Authors’ Contributions

Conceived and designed study: D.D. Performed experiments: Y.Y., X.P., C.H.H., K.K., K.Z., J.S., H.T.Y. and T.M. Analyzed data: D.D., Y.Y., X.P., C.H.H.. Wrote the paper: D.D.

Conflict of Interest statement. D.D. is a member of the scientific advisory board for Solid GT, LLC, a venture company founded to advance gene therapy for DMD.

Funding

This work was supported by grants (to D.D.) from Department of Defense MD130014, Jessey's Journey-The Foundation for Cell and Gene Therapy, Hope for Javier, the National Institutes of Health HL-91883, the Gene Therapy Resource Program of the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute located at the University of Pennsylvania, Kansas City Area Life Sciences Institute and the University of Missouri.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr Arun Srivastava for providing experimental Y731F AAV-9 packaging construct and Dr Ronald Terjung for helpful discussion.

References

- 1.Mingozzi F., High K.A. (2011) Therapeutic in vivo gene transfer for genetic disease using AAV: progress and challenges. Nat. Rev. Genet., 12, 341–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lewis R. (2014) Gene therapy's second act. Sci. Am., 310, 52–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kunkel L.M. (2005) 2004 William Allan award address. Cloning of the DMD gene. Am. J. Hum. Genet., 76, 205–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson J.M. (2009) Lessons learned from the gene therapy trial for ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency. Mol. Genet. Metab., 96, 151–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kornegay J.N., Li J., Bogan J.R., Bogan D.J., Chen C., Zheng H., Wang B., Qiao C., Howard J.F. Jr., Xiao X. (2010) Widespread muscle expression of an AAV9 human mini-dystrophin vector after intravenous injection in neonatal dystrophin-deficient dogs. Mol. Ther., 18, 1501–1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gregorevic P., Blankinship M.J., Allen J.M., Crawford R.W., Meuse L., Miller D.G., Russell D.W., Chamberlain J.S. (2004) Systemic delivery of genes to striated muscles using adeno-associated viral vectors. Nat. Med., 10, 828–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Z., Zhu T., Qiao C., Zhou L., Wang B., Zhang J., Chen C., Li J., Xiao X. (2005) Adeno-associated virus serotype 8 efficiently delivers genes to muscle and heart. Nat. Biotechnol., 23, 321–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bostick B., Ghosh A., Yue Y., Long C., Duan D. (2007) Systemic AAV-9 transduction in mice is influenced by animal age but not by the route of administration. Gene Ther., 14, 1605–1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bostick B., Shin J.H., Yue Y., Wasala N.B., Lai Y., Duan D. (2012) AAV micro-dystrophin gene therapy alleviates stress-induced cardiac death but not myocardial fibrosis in >21-m-old mdx mice, an end-stage model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy cardiomyopathy. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol., 53, 217–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bostick B., Shin J.-H., Yue Y., Duan D. (2011) AAV-microdystrophin therapy improves cardiac performance in aged female mdx mice. Mol. Ther., 19, 1826–1832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gregorevic P., Blankinship M.J., Allen J.M., Chamberlain J.S. (2008) Systemic microdystrophin gene delivery improves skeletal muscle structure and function in old dystrophic mdx mice. Mol. Ther., 16, 657–664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duan D. (2015) Duchenne muscular dystrophy gene therapy in the canine model. Hum. Gene Ther. Clin. Dev., 26, 57–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yue Y., Ghosh A., Long C., Bostick B., Smith B.F., Kornegay J.N., Duan D. (2008) A single intravenous injection of adeno-associated virus serotype-9 leads to whole body skeletal muscle transduction in dogs. Mol. Ther., 16, 1944–1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yue Y., Shin J.H., Duan D. (2011) Whole body skeletal muscle transduction in neonatal dogs with AAV-9. Methods Mol. Biol., 709, 313–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pan X., Yue Y., Zhang K., Lostal W., Shin J.H., Duan D. (2013) Long-term robust myocardial transduction of the dog heart from a peripheral vein by adeno-associated virus serotype-8. Hum. Gene Ther., 24, 584–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hakim C.H., Yue Y., Shin J.H., Williams R.R., Zhang K., Smith B.F., Duan D. (2014) Systemic gene transfer reveals distinctive muscle transduction profile of tyrosine mutant AAV-1, -6, and -9 in neonatal dogs. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev., 1, 14002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pan X., Yue Y., Zhang K., Hakim C.H., Kodippili K., McDonald T., Duan D. (2015) AAV-8 is more efficient than AAV-9 in transducing neonatal dog heart. Hum. Gene Ther. Methods, 26, 54–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duan D. (2011) Duchenne muscular dystrophy gene therapy: lost in translation? Res. Rep. Biol., 2, 31–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhong L., Li B., Mah C.S., Govindasamy L., Agbandje-McKenna M., Cooper M., Herzog R.W., Zolotukhin I., Warrington K.H. Jr., Weigel-Van Aken K.A. et al. (2008) Next generation of adeno-associated virus 2 vectors: point mutations in tyrosines lead to high-efficiency transduction at lower doses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 105, 7827–7832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martino A.T., Basner-Tschakarjan E., Markusic D.M., Finn J.D., Hinderer C., Zhou S., Ostrov D.A., Srivastava A., Ertl H.C., Terhorst C. et al. (2013) Engineered AAV vector minimizes in vivo targeting of transduced hepatocytes by capsid-specific CD8+ T cells. Blood, 121, 2224–2233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shin J.H., Pan X., Hakim C.H., Yang H.T., Yue Y., Zhang K., Terjung R.L., Duan D. (2013) Microdystrophin ameliorates muscular dystrophy in the canine model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Mol. Ther., 21, 750–757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shin J.H., Yue Y., Srivastava A., Smith B., Lai Y., Duan D. (2012) A simplified immune suppression scheme leads to persistent micro-dystrophin expression in Duchenne muscular dystrophy dogs. Hum. Gene Ther., 23, 202–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pacak C.A., Mah C.S., Thattaliyath B.D., Conlon T.J., Lewis M.A., Cloutier D.E., Zolotukhin I., Tarantal A.F., Byrne B.J. (2006) Recombinant adeno-associated virus serotype 9 leads to preferential cardiac transduction in vivo. Circ. Res., 99, e3–e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mendell J.R., Campbell K., Rodino-Klapac L., Sahenk Z., Shilling C., Lewis S., Bowles D., Gray S., Li C., Galloway G. et al. (2010) Dystrophin immunity in Duchenne's muscular dystrophy. N. Engl. J. Med., 363, 1429–1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McGreevy J.W., Hakim C.H., McIntosh M.A., Duan D. (2015) Animal models of Duchenne muscular dystrophy: from basic mechanisms to gene therapy. Dis. Model. Mech., 8, 195–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Foust K.D., Nurre E., Montgomery C.L., Hernandez A., Chan C.M., Kaspar B.K. (2009) Intravascular AAV9 preferentially targets neonatal neurons and adult astrocytes. Nat. Biotechnol., 27, 59–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang H., Yang B., Mu X., Ahmed S.S., Su Q., He R., Wang H., Mueller C., Sena-Esteves M., Brown R. et al. (2011) Several rAAV vectors efficiently cross the blood–brain barrier and transduce neurons and astrocytes in the neonatal mouse central nervous system. Mol. Ther., 19, 1440–1448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Flanigan K., Campbell K., Viollet L., Wang W., Gomez A.M., Walker C., Mendell J.R. (2013) Anti-dystrophin T cell responses in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: prevalence and a glucocorticoid treatment effect. Hum. Gene Ther., 24, 797–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Toniolo L., Maccatrozzo L., Patruno M., Caliaro F., Mascarello F., Reggiani C. (2005) Expression of eight distinct MHC isoforms in bovine striated muscles: evidence for MHC-2B presence only in extraocular muscles. J. Exp. Biol., 208, 4243–4253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vulin A., Barthelemy I., Goyenvalle A., Thibaud J.L., Beley C., Griffith G., Benchaouir R., le Hir M., Unterfinger Y., Lorain S. et al. (2012) Muscle function recovery in golden retriever muscular dystrophy after AAV1-U7 exon skipping. Mol. Ther., 20, 2120–2133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Le Guiner C., Montus M., Servais L., Cherel Y., Francois V., Thibaud J.L., Wary C., Matot B., Larcher T., Guigand L. et al. (2014) Forelimb treatment in a large cohort of dystrophic dogs supports delivery of a recombinant AAV for exon skipping in Duchenne patients. Mol. Ther., 22, 1923–1935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bish L.T., Sleeper M.M., Forbes S.C., Wang B., Reynolds C., Singletary G.E., Trafny D., Morine K.J., Sanmiguel J., Cecchini S. et al. (2012) Long-term restoration of cardiac dystrophin expression in golden retriever muscular dystrophy following rAAV6-mediated exon skipping. Mol. Ther., 20, 580–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yoshimura M., Sakamoto M., Ikemoto M., Mochizuki Y., Yuasa K., Miyagoe-Suzuki Y., Takeda S. (2004) AAV vector-mediated microdystrophin expression in a relatively small percentage of mdx myofibers improved the mdx phenotype. Mol. Ther., 10, 821–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chamberlain J.S. (1997) Dystrophin levels required for correction of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Basic Appl. Myol., 7, 251–255. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cooper B.J., Winand N.J., Stedman H., Valentine B.A., Hoffman E.P., Kunkel L.M., Scott M.O., Fischbeck K.H., Kornegay J.N., Avery R.J. et al. (1988) The homologue of the Duchenne locus is defective in X-linked muscular dystrophy of dogs. Nature, 334, 154–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith B.F., Yue Y., Woods P.R., Kornegay J.N., Shin J.H., Williams R.R., Duan D. (2011) An intronic LINE-1 element insertion in the dystrophin gene aborts dystrophin expression and results in Duchenne-like muscular dystrophy in the corgi breed. Lab. Invest., 91, 216–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fine D.M., Shin J.H., Yue Y., Volkmann D., Leach S.B., Smith B.F., McIntosh M., Duan D. (2011) Age-matched comparison reveals early electrocardiography and echocardiography changes in dystrophin-deficient dogs. Neuromuscul. Disord., 21, 453–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Petrs-Silva H., Dinculescu A., Li Q., Min S.H., Chiodo V., Pang J.J., Zhong L., Zolotukhin S., Srivastava A., Lewin A.S. et al. (2009) High-efficiency transduction of the mouse retina by tyrosine-mutant AAV serotype vectors. Mol. Ther., 17, 463–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shin J.H., Yue Y., Duan D. (2012) Recombinant adeno-associated viral vector production and purification. Methods Mol. Biol., 798, 267–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang H.T., Shin J.H., Hakim C.H., Pan X., Terjung R.L., Duan D. (2012) Dystrophin deficiency compromises force production of the extensor carpi ulnaris muscle in the canine model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. PLoS One, 7, e44438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.