Abstract

Objective

To describe tools used for the assessment of maternal and child health issues in humanitarian emergency settings.

Methods

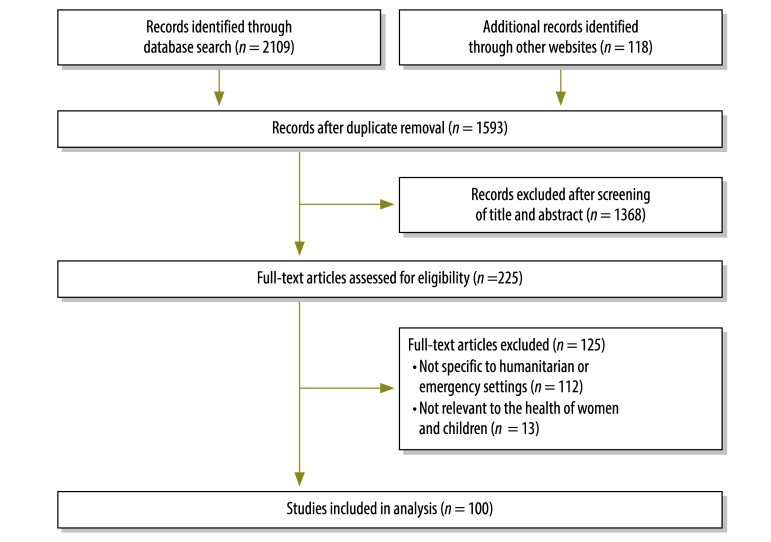

We systematically searched MEDLINE, Web of Knowledge and POPLINE databases for studies published between January 2000 and June 2014. We also searched the websites of organizations active in humanitarian emergencies. We included studies reporting the development or use of data collection tools concerning the health of women and children in humanitarian emergencies. We used narrative synthesis to summarize the studies.

Findings

We identified 100 studies: 80 reported on conflict situations and 20 followed natural disasters. Most studies (76/100) focused on the health status of the affected population while 24 focused on the availability and coverage of health services. Of 17 different data collection tools identified, 14 focused on sexual and reproductive health, nine concerned maternal, newborn and child health and four were used to collect information on sexual or gender-based violence. Sixty-nine studies were done for monitoring and evaluation purposes, 18 for advocacy, seven for operational research and six for needs assessment.

Conclusion

Practical and effective means of data collection are needed to inform life-saving actions in humanitarian emergencies. There are a wide variety of tools available, not all of which have been used in the field. A simplified, standardized tool should be developed for assessment of health issues in the early stages of humanitarian emergencies. A cluster approach is recommended, in partnership with operational researchers and humanitarian agencies, coordinated by the World Health Organization.

Résumé

Objectif

Décrire les outils utilisés pour évaluer les problèmes en matière de santé maternelle et infantile dans les situations d'urgence humanitaire.

Méthodes

Nous avons recherché de façon systémique, dans les bases de données Medline, Web of Knowledge et Popline, les études publiées entre janvier 2000 et juin 2014. Nous avons également fait des recherches sur les sites Internet d'organisations intervenant dans les situations d’urgence humanitaire. Nous avons inclus les études qui se rapportaient au développement ou à l'utilisation d'outils de collecte de données concernant la santé des femmes et des enfants dans des situations d'urgence humanitaire. Nous avons résumé ces études par une synthèse narrative.

Résultats

Nous avons retenu 100 études: 80 portaient sur des situations de conflit et 20 faisaient suite à des catastrophes naturelles. La plupart de ces études (76/100) s'intéressaient à la situation sanitaire des populations affectées tandis que 24 d'entre elles s'intéressaient à la disponibilité de services de santé et à leur couverture. Sur 17 outils de collecte de données identifiés, 14 concernaient la santé sexuelle et génésique, neuf la santé de la mère, du nouveau-né et de l'enfant, et quatre servaient à recueillir des informations sur la violence sexuelle ou exercée à l'égard des femmes. Soixante-neuf études avaient été réalisées à des fins de suivi et d'évaluation, dix-huit de sensibilisation, sept pour la recherche opérationnelle et six pour évaluer les besoins.

Conclusion

Des moyens pratiques et efficaces de collecte de données sont nécessaires pour orienter les actions permettant de préserver des vies humaines dans les situations d'urgence humanitaire. Il existe une grande variété d'outils disponibles, dont tous n'ont pas été employés sur le terrain. Il faudrait développer un outil simplifié et standardisé pour évaluer les problèmes sanitaires dès les premières phases des urgences humanitaires. Il est recommandé d'adopter une approche groupée, en partenariat avec les chercheurs opérationnels et les agences humanitaires, sous la coordination de l'Organisation mondiale de la Santé.

Resumen

Objetivo

Describir las herramientas utilizadas para evaluar los problemas de salud materna e infantil en entornos de emergencias humanitarias.

Método

Se realizaron búsquedas sistemáticas en las bases de datos de Medline, Web of Knowledge y Popline para encontrar estudios publicados entre enero de 2000 y junio de 2014. También se realizaron búsquedas en páginas web de organizaciones activas en emergencias humanitarias. Se incluyeron estudios que informaban sobre el desarrollo o el uso de herramientas de recopilación de datos relacionadas con la salud de las mujeres y los niños durante emergencias humanitarias. Se utilizó la síntesis narrativa para resumir los estudios.

Resultados

Se identificaron 100 estudios: 80 informaban sobre situaciones de conflicto y 20 sobre desastres naturales. La mayoría de los estudios (76/100) se centraban en el estado de la salud de la población afectada, mientras que 24 lo hacían en la disponibilidad y cobertura de los servicios de salud. De las 17 herramientas de recopilación de datos diferentes identificadas, 14 se centraban en la salud reproductiva y sexual, nueve trataban sobre salud maternal, neonatal e infantil y cuatro se utilizaban para recopilar información sobre violencia sexual o basada en el género. 69 estudios se habían realizado con fines de supervisión y evaluación, 18 para promoción, siete para investigaciones operacionales y seis para la evaluación de necesidades.

Conclusión

Se necesitan medios prácticos y efectivos de recopilación de datos para informar de acciones para salvar vidas en emergencias humanitarias. Existe una amplia variedad de herramientas disponibles, y no todas se han utilizado en este campo. Se debería desarrollar una herramienta simplificada estándar para evaluar los problemas de salud en las primeras etapas de emergencias humanitarias. Se recomienda un enfoque por grupos en cooperación con investigadores operacionales y agencias humanitarias, coordinados por la Organización Mundial de la Salud.

ملخص

الغرض

وصف الأدوات المستخدمة في تقييم مشكلات صحة الأمومة والطفولة في أماكن وقوع الحالات الإنسانية الطارئة.

الطريقة

قمنا بإجراء بحث منهجي في قواعد معطيات Medline، وWeb of Knowledge، وPopline للدراسات المنشورة في الفترة من يناير/كانون الثاني 2000 وحتى يونيو/حزيران 2014، كما بحثنا أيضًا في المواقع الإلكترونية للمؤسسات الفاعلة في مجال الحالات الإنسانية الطارئة. وقمنا بتضمين دراسات توضح إعداد أدوات جمع البيانات أو استخدامها فيما يتعلق بصحة النساء والأطفال في الحالات الإنسانية الطارئة. كما اتبعنا أسلوبًا تجميعيًا سرديًا لتلخيص الدراسات.

النتائج

لقد حددنا 100 دراسة، فوجدنا أن 80 دراسة منها أوردت بيانات عن حالات الصراع فيما تابعت 20 دراسة منها وقوع كوارث طبيعية. ركزت معظم الدراسات (76 من إجمالي 100) على الحالة الصحية للشريحة السكانية المتأثرة، في حين ركزت 24 دراسة على مدى توافر الخدمات الصحية ونطاق تغطيتها. ومن ضمن 17 أداة من أدوات جمع البيانات المختلفة التي تم تحديدها، ركزت 41 أداة على الصحة الجنسية والإنجابية، وكانت تسع أدوات معنية بصحة الأم والوليد والطفل، فيما تم استخدام أربع أدوات لجمع المعلومات عن العنف الجنسي أو العنف الجنساني. تم إجراء تسعة وستين دراسة لأغراض الرصد والتقييم، فيما تمت 18 دراسة للمناصرة، وسبع دراسات للبحوث الميدانية، وست دراسات لتقييم الاحتياجات.

الاستنتاج

هناك حاجة لاتباع وسائل عملية وفعالة لجمع البيانات اللازمة التي تقوم على أساسها الإجراءات الحاسمة لإنقاذ الأرواح في الحالات الإنسانية الطارئة. وتتوفر مجموعة متنوعة وواسعة من الأدوات، والتي لم يتم استخدامها جميعًا في الميدان. وينبغي إعداد أدوات مبسطة وموحدة لتقييم المشكلات الصحية في المراحل الأولى من الحالات الإنسانية الطارئة. يُوصى باتباع نهج قطاعي (Cluster approach)، بالاشتراك مع الباحثين التنفيذيين ووكالات المساعدة الإنسانية، وبالتنسيق من جانب منظمة الصحة العالمية.

摘要

目的

旨在描述在人道主义紧急情况中用于评估孕产妇和儿童健康问题的工具。

方法

我们在联机医学文献分析和检索系统 (Medline)、Web of Knowledge 和 Popline 数据库中系统搜索了于 2000 年 1 月至 2014 年 6 月之间发表的研究报告。我们还搜索了在人道主义紧急情况中表现积极的组织的网站。 我们涵盖的研究报告了对与人道主义紧急情况中的妇女和儿童有关的数据收集工具的开发和使用。 我们采用叙述性综合法对研究进行了总结概括。

结果

我们确定了 100 项研究: 其中 80 项报告了冲突局势,其余 20 项报告了自然灾害。 大部分研究 (76/100) 侧重于受灾人群的健康状态,而其他 24 项研究侧重于卫生服务的可用性和覆盖范围。 在确定的 17 种不同的数据收集工具中,14 种侧重于性与生殖健康,九种与孕产妇、新生儿和儿童健康有关,四种用于收集与性或性暴力行为有关的信息。 69 项研究是以监控和评估为目的而开展的,18 项以宣传倡导为目的,7 项以操作性研究为目的,6 项以需求评估为目的。

结论

我们需要采取实用、有效的数据收集方式,以了解人道主义紧急情况中的生命拯救行动。 可用工具各式各样,然而并非所有工具都曾用于该领域。 我们应开发出标准化的简易工具,用于评估在人道主义紧急情况早期出现的健康问题。 建议采用聚类的方法,并且在世界卫生组织的协调下与操作性研究人员及人道主义机构开展合作。

Резюме

Цель

Описать инструменты, используемые для оценки проблем материнского здоровья и здоровья детей в условиях чрезвычайной ситуации гуманитарного характера.

Методы

Был проведен систематический поиск исследований в базах данных Medline, Web of Knowledge и Popline, опубликованных с января 2000 года по июнь 2014 года. Поиск также осуществлялся на веб-сайтах организаций, работающих в условиях чрезвычайных ситуаций гуманитарного характера. В обзор были включены исследования, в которых сообщалось о разработке или использовании инструментов сбора данных о здоровье женщин и детей в условиях чрезвычайных ситуаций гуманитарного характера. Для получения сводных данных по этим исследованиям использовался нарративный синтез.

Результаты

Нами было выявлено 100 исследований: в 80 из них сообщалось о конфликтах, а в 20 речь шла о стихийных бедствиях. Большая часть исследований (76 из 100) была посвящена состоянию здоровья затронутого бедствием населения, а в 24 речь шла о доступности услуг здравоохранения об охвате населения такими услугами. Из 17 выявленных инструментов сбора данных 14 касались сексуального и репродуктивного здоровья, девять — здоровья матерей, новорожденных и детей, четыре опроса использовались для сбора информации о сексуальном насилии или насилии по половому признаку. Шестьдесят девять исследований были проведены с целью мониторинга и оценки ситуации, 18 — из соображений защиты прав человека, семь — в порядке операционных исследований, шесть — для оценки потребностей.

Вывод

Практичные и эффективные инструменты сбора данных оказываются необходимыми для мероприятий по спасению жизни, предпринимаемых в ходе чрезвычайных ситуаций гуманитарного характера. Доступно множество инструментов, однако не все они используются на практике. Следует разработать упрощенное стандартизированное средство оценки проблем со здоровьем на ранних этапах чрезвычайных ситуаций гуманитарного характера. Рекомендуется использовать кластерный подход и взаимодействовать с гуманитарными организациями и специалистами по операционным исследованиям при координации со стороны Всемирной организации здравоохранения.

Introduction

Humanitarian emergencies are natural disasters, man-made events or a combination of both that represent critical threats to the health, safety, security or wellbeing of a community.1 Humanitarian emergencies resulting from conflict, natural disasters, famine or communicable disease outbreaks have important health implications. Currently, there are approximately 39 million people displaced by conflict or violence.2 Every year, millions are displaced due to weather-related or geophysical disasters.3 Women and children are generally the worst affected – representing over three-quarters of the estimated 80 million people in need of humanitarian assistance in 2014.4,5 Moreover, many countries with high maternal, newborn and child mortality rates are affected by humanitarian emergencies.

Humanitarian emergencies are frequently characterized by the collapse of basic health services. For better decision-making, coordination and response in such emergencies, humanitarian actors need access to appropriate information.4,6,7 Studies have reported that during humanitarian emergencies, there can be either a shortage or, conversely, an overload of information. Both situations impair provision of effective humanitarian assistance.8

Sexual and reproductive health has historically been neglected in humanitarian emergency settings.9 Health services provided for women and children vary depending on location, climate, culture, existing infrastructure, population health and type of humanitarian crisis. The types of response also vary, with multiple governments and humanitarian agencies involved. Efficient, easy to use, comprehensive data collection tools are needed to aid situation analysis, decision-making and coordination of responses to humanitarian crises.10

We review tools for collection of data concerning the health of women and children in humanitarian emergencies. We identify which tools are available and where they have been used. For each study, we describe the setting and purpose of the study, the types of data collected and the tools used to collect the data.

Methods

Search strategy

We conducted a systematic review according to current guidelines.11 We searched MEDLINE, Web of Knowledge and POPLINE databases for studies in English published between 1 January 2000 and 30 June 2014. Searches incorporated medical subject heading terms, keywords and free text using the following search terms: “reproductive health”, “sexual”, “maternal”, “newborn”, “child/child health service*”, “pregnan*”, “neonat*” under one search string and “disaster”, “post conflict”, “war”, “humanitarian”, “refugee”, “internally displaced” under another string. The Boolean operator “OR” was used for the terms under each search string and “AND” was used to combine the two strings. The detailed search strategy is available from the authors.

Through a snowballing process, we identified organizations known for their work in humanitarian emergencies and searched the websites of these organizations – including CARE International, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Harvard Humanitarian Initiative, the Inter-Agency Standing Committee, the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC), the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome), Knowledge for Health (K4Health), Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Oxfam, the Reproductive Health Response in Crises Consortium, Save the Children, the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), the Women’s Refugee Commission, the World Health Organization (WHO) and World Vision. The snowballing process was carried out using the reference list of included studies and the organizations known for humanitarian emergencies. We also searched the references and authors of all included studies.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were included if they reported the development or use of data collection tools concerning the health of women and children in a humanitarian emergency. We included studies, even when tools for data collection were not specified or the method was not described (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart for the selection of studies: data collection tools for maternal and child health in humanitarian emergencies

Two authors independently searched databases and websites. The titles and abstracts of identified studies were screened and excluded if not meeting the inclusion criteria. Full texts of remaining studies were assessed for eligibility. When it was not clear if a study should be included or not, two reviewers discussed the study and if consensus was not reached, a third reviewer was consulted. The reviewers summarized information on tools used, type of data collected and the purpose of the study. Data were classified into four categories, based upon the continuum of care: (i) sexual and reproductive health including sexual/gender-based violence and family planning; (ii) maternal and neonatal health; (iii) infant and child health; and (iv) sexually transmitted infections, including HIV/AIDS.

Studies that met the inclusion criteria were summarized using textual narrative synthesis.10 First, we developed a commentary report on the type and characteristics of the included studies, context and findings using a standard matrix. The reviewers then looked for similarities and differences among studies to discuss and draw conclusion across the studies.

Results

We identified 2227 studies: 2109 publications from databases and 118 studies from websites. After removal of duplicates, the titles and abstract of 1593 studies were screened and of these, 225 studies were identified as eligible for full text review. Of these, 112 were not specific to humanitarian or emergency settings and 13 were not relevant (Fig. 1).

Of the 100 studies identified, 69 studies described the number of people affected. The population consisted of 677 568 individuals; 65 971 were identified as women and 57 427 children; 37 660 (57%) of children were younger than five years (Table 1, available at: http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/93/9/14-148429). Studies ranged in sample size from seven (in case studies of survivors of sexual violence)63 to 179 172 (in a rapid assessment of micronutrient deficiency following drought).71 Eighty studies reported on conflict situations, while 20 studies reported on situations following a natural disaster (tsunami, hurricane or drought). Nineteen studies reported on the timing of data collection: three studies collected data within one week,70,72,79 five within three months,7,19,49,51,52 and 11 studies collected data six months to one year after the onset of the humanitarian emergency.21,36,38,46,55,60,73,76,81,86,87

Table 1. Summary table of included studies by author.

| Author | Tools and methods | Type of data collected by category | Outcome (use of data collected) | Setting (country – type of emergency if information available) | Populations included | Publication type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdalla et al., 200812 | Cross-sectional survey; interviews and physical assessments | Maternal and neonatal health; Infant and child health Anthropometric measures including haemoglobin level, diarrhoea and ARI and the feeding practices of mothers |

Prevalence of malnutrition, cumulative incidence of diarrhoea and ARI and the feeding practices of mothers | Nepal – refugees from Bhutan | 413 women of reproductive age and 497 children younger than five years | Not peer reviewed |

| Abdeen et al., 200713 | Validated multistage clustered design using an interviewer-administered questionnaire and anthropometric measurements | Infant and child health Basic demography, feeding patterns, food availability, dietary intake and anthropometric measurements |

Assessment of nutritional status of children aged 6 month to 5 years following food assistance | West Bank and Gaza strip – uprising | 3089 children younger than five years | Peer reviewed |

| Abu Mourad et al., 200414 | Cross-sectional household survey | Infant and child health Data on socioeconomic, environmental health, hygiene, incidence of intestinal parasites and diarrhoea by age segregation |

Causes of gastrointestinal illness in refugee camp | West Bank and Gaza strip | 1625 women of reproductive age | Peer reviewed |

| Amowitz et al., 200215 | Cross-sectional randomized survey | SRH including GBV Physical and mental health perception, personal experiences on sexual assault and human rights abuse |

Estimate of war and non-war sexual violence against Internally Displace Person and non-Internally Displaced women | Sierra Leone – IDP | 991 women | Peer reviewed |

| Annan et al., 200816 | Household surveys | SRH including GBV Long-term effects of abduction, war violence, forced marriage and motherhood on young women and girls |

Basis for advocacy to recognize the importance of the problem | Uganda - protracted internal war | 619 young women and girls | Not peer reviewed |

| ARC International, 200317 | Baseline survey results compared with post-intervention survey | STI including HIV Knowledge, attitudes and behaviour regarding HIV/AIDS and other STIs before and after intervention |

To formulate policy recommendations | Sierra Leone | 956 individuals | Not peer reviewed |

| Armony-Sivan et al., 201318 | Cross-sectional survey, interview-based study using regression analysis | Maternal and neonatal health Maternal data on basic sociodemographics including ANC and PNC Maternal depression and anxiety |

To examine the relationship between maternal stress in early pregnancy and cord-blood ferritin concentration | Southern Israel – post-emergency (after rocket attack during the military operation) | 140 pregnant women | Peer reviewed |

| Arques et al., 201319 | Cross-sectional, secondary data from a hospital | Infant and child health Demographic, physical, microbiologic findings, treatment and outcomes of children |

To analyse the results of clinical and microbiological characteristics of children treated in the hospital | Haiti – earthquake 2010 | 118 individuals, 53 children | Peer reviewed |

| Assefa et al., 200120 | Two-stage cluster household survey, standardized data collection tool | Infant and child health Weight for age data of children younger than five years, food coping mechanisms |

Causes of crude and under 5 mortality rates and prevalence of malnutrition | Afghanistan – civil war and drought | 3165 individuals of which 41% (763) children younger than five years | Peer reviewed |

| Ayoya et al., 201321 | Daily data recording of attendees managed using standardized form | Maternal and neonatal health; Infant and child health Feeding practices and anthropometric measurements |

To evaluate methods and guidelines on implementation of baby tents to facilitate breast feeding following natural disasters | Haiti – earthquake | 180 499 mother-infant pairs, 52 503 pregnant women | Peer reviewed |

| Baines, 201422 | Cross-sectional, qualitative data using FGD | SRH including GBV Perceptions of former commanders and wives on historical evolution of forced marriage |

To highlight strategic use of sexual violence in political projects | Sudan – post-conflict | 18 participants of which 15 are women | Peer reviewed |

| Balsara et al., 201023 | Interviewer-administered questionnaire, physical examination and lab tests | SRH including GBV Knowledge on RTIs and behavioural factors contributing to RTIs |

Prevalence of RTI in Afghan refugee women | Pakistan – refugee camps | 634 women of reproductive age | Peer reviewed |

| Bartels et al., 201024 | Retrospective review of medical records using non-systematic convenience sample; semi-structured interviews with an open self-reporting interview | SRH including GBV Physical and psychological consequences of sexual violence |

To describe the demographics and define both physical and psychosocial consequences of sexual violence | Democratic Republic of the Congo – ongoing prolonged conflict | 1021 women of which 82.7% are women of reproductive age | Peer reviewed |

| Bartels et al., 201325 | Retrospective analysis of secondary data | SRH including GBV Perpetrator profiles; attack characteristics including type and location of sexual violence |

To describe the patterns of sexual violence described by the survived victims and analyse perpetrator profiles | Democratic Republic of the Congo – post conflict | NA | Peer reviewed |

| Bbaale, 201126 | Two–stage cluster using Uganda Demographic and Health Survey (2006) | Infant and child health Prevalence of diarrhoea and ARI |

Factors associated with occurrence of diarrhoea and incidence ofARI in children younger than five years | Uganda - IDP camps | NA | Peer reviewed |

| Bbaale & Guloba, 201127 | Two-stage cluster using Uganda Demographic and Health Survey (2006) | Maternal and neonatal health; Infant and child health Factors (maternal education, community infrastructure, occupation, location, wealth, religion and age) associated with utilization of professional childbirth care |

To improve uptake of skilled care at birth | Uganda - IDP camps | NA | Peer reviewed |

| Beatty et al., 200128 | Interviews with IDP and health staff; no specific tool described | SRH including GBV; Maternal and neonatal health; STI including HIV RH needs and services available |

To assess the RH needs and RH services available | Angola – IDP in civil war | NA | Not peer reviewed |

| Bilukha et al., 200729 | Victim data collection, demographics and standard international management system for mine action data collection form | Infant and child health Children are included as demographic indicators under landmine injuries |

Rates of injury from landmines in civilians | Chechnya, Russia – armed conflict | NA | Peer reviewed |

| Bisimwa et al., 200930 | Community based child nutritional monitoring, physical assessment | Infant and child health Weight for age measurement, incidence of childhood illnesses |

Assessment of effectiveness of monitoring the growth of pre-school children from a cohort of endemic malnutrition | Democratic Republic of the Congo – armed conflict | 5479 children younger than five years | Peer reviewed |

| Brown et al., 201031 | Population based study, laboratory tests and demographic data | Infant and child health Data on blood lead level and chelation |

Association between lead poisoning prevention activities and blood lead levels among children | Serbia – IDP camp | 145 children | Peer reviewed |

| Burns et al., 201232 | Clinical questionnaire based on the integrated management of childhood illness | Infant and child health Prevalence of malaria among children |

Development of a novel tool to control malaria in an emergency setting | Sierra Leone – refugee camp | 222 children aged 4–36 months | Peer reviewed |

| Callands et al., 201333 | Secondary data analysis of DHS data | SRH including GBV IPV experiences, attitude towards IPV, ability to negotiate safe sex and STIs incidence |

To identify the relationship between STIs and negotiation for sexual safety with intimate partners among young women | Liberia – post-conflict | NA | Peer reviewed |

| Casey et al., 200934 | Facility assessments, interviews, observation and clinical record review | Maternal and neonatal health Assessment of RH facilities |

To determine availability, utilization and quality of emergency obstetric care and family planning services to avert death and disability | Democratic Republic of the Congo – conflict | NA | Peer reviewed |

| Casey et al., 201335 | Population based baseline and end-line surveys; CDC’s Reproductive health assessment toolkit for conflict | SRH including GBV Family planning |

To evaluate the effectiveness of provision of long acting family planning methods both in mobile clinic and health centres | Northern Uganda | 1778 women of reproductive age | Peer reviewed |

| CDC, 200136 | Three-stage cluster sample design; interview and physical assessments | Infant and child health Anthropometric measures including haemoglobin level |

Determination of causes of malnutrition (acute and chronic) | Mongolia – severe winter weather | 937 children aged between 6–59 months | Not peer reviewed |

| D’Errico et al., 201337 | Semi-structured interviews from 16 locations from male and female respondents | SRH including GBV; Maternal and neonatal health Local perceptions of the determinants of maternal health; Women’s coping mechanisms regarding barriers to healthcare; existence of informal systems of social support |

Some understanding of social determinants of health | Four eastern provinces of Democratic Republic of the Congo | 121 respondents | Peer reviewed |

| Doocy et al., 200938 | Two-stage cluster design, survey instrument not specified | Maternal and neonatal health; Infant and child health |

Information on pre- and post-tsunami household composition, including deaths and injuries | Indonesia – tsunami | NA | Peer reviewed |

| Dossa et al., 201339 | Cross-sectional population-based study | SRH including GBV; STI including HIV Fistula , chronic pelvic pain, desire for sex and desire for children |

To investigate the relationship between sexual violence and serious RTIs including fistula | Democratic Republic of the Congo – post-conflict | 7935 individuals | Peer reviewed |

| Dua et al., 201340 | Retrospective analysis using data from military hospitals in Baghdad | Infant and child health Demographic and physiologic data on paediatric vascular injuries |

To describe the experience of paediatric vascular injuries in a military combat support hospital | Iraq – post conflict | 320 females | Peer reviewed |

| Edwards et al., 201341 | Cross-sectional analysis of hospitals admission databases | Infant and child health % of children required transfusion, location of injury, length of hospital stay and in-hospital mortality |

To define the scope of combat and noncombat-related inpatient paediatric humanitarian care provided by the military of the USA | Afghanistan and Iraq – post-conflicts | NA | Peer reviewed |

| Elhag et al., 201342 | Cross-sectional analysis using clinical data | Infant and child health Clinical history, sociodemographic characteristics, physical examination and laboratory tests of diarrhoea among children |

To determine prevalence of rotavirus and adenovirus associated diarrhoea | Sudan – IDP | NA | Peer reviewed |

| Falb et al., 201443 | Cross-sectional interview-based survey | SRH including GBV; Maternal and neonatal health Frequencies of pregnancy complications, violence, conflict victimization |

To guide maternal health programmatic efforts among refugee women | Border between Myanmar and Thailand – refugee camps | 710 individuals (330 children younger than five years) | Peer reviewed |

| Feseha et al., 201244 | Community-based cross-sectional study | SRH including GBV; Maternal and neonatal health Physical violence for two timeframes: 12 months preceding interview; any time during the woman’s life since she started relationship with the current partner. Data from pregnant women also included |

Prevalence of physical violence | Northern Ethiopia | 1223 women of reproductive age | Peer reviewed |

| Ghazi et al., 201345 | Cross-sectional self-administered questionnaire | Infant and child health Anthropometric measurements and family social factors |

Identified factors associated with child malnutrition | Iraq – conflict | 220 children aged between 3–5 years | Peer reviewed |

| Gitau et al., 200546 | Longitudinal cohort study, standardized questionnaire, physical examination and laboratory tests | Maternal and neonatal health; Infant and child health Vitamin A during pregnancy, Vitamin E post-partum, maternal weight and haemoglobin; infant length and weight |

Effects of drought on maternal and infant health | Zambia – drought and famine | 429 women of reproductive age | Peer reviewed |

| Gordon & Halileh, 201347 | Cross-sectional survey using WHO child growth standards | Infant and child health Anthropometric measurements; birth weight; breastfeeding practice, family and household social factors |

Identified factors associated with child stunting | West Bank and Gaza strip – conflict | 9051 children younger than five years | Peer reviewed |

| Guerrier et al., 200948 | Two stage cluster survey | Infant and child health Anthropometric indices and measles vaccination history |

Crude mortality rate, under-five mortality rate, prevalence of wasting and vaccination status among children aged between 6 months and 5 years | Eastern Chad – IDP | 80 300 individuals | Peer reviewed |

| Hapsari et al., 200949 | Community based surveys | SRH including GBV Access to contraception, change in contraceptive methods before and after the earthquake, prevalence of unplanned pregnancy |

To plan for effective family planning coverage | Indonesia – earthquake | 450 women of reproductive age | Peer reviewed |

| Helweg-Larsen et al., 200450 | Data collection from medical records using ICD-10 and International Classification of External Causes of Injuries | Infant and child health Intent, mechanism, means, context and place of intentional injuries among children, relationship with perpetrator |

To evaluate the combination of ICD– 10 and International Classification of External Causes of Injuries, to test the feasibility of a systematic documentation of public health consequences of such conflicts | West Bank and Gaza strip – uprising | NA | Peer reviewed |

| Hossain et al., 200951 | Cross-sectional household survey using clusters; No information provided for tool | Infant and child health Prevalence of acute malnutrition in children |

To identify the relationship between food aid and nutritional status | Pakistan – earthquake | 1114 children aged between 6 and 59 months | Peer reviewed |

| Hudson et al., 201052 | Semi-structured questionnaire containing quantitative and open-ended questions | SRH including GBV; Maternal and neonatal health; STI including HIV; Access to medical care, access to care during pregnancy and childbirth, access to food, water, and hygiene facilities, perception of personal safety |

Needs assessment | Haiti – post earthquake with long-term political instability, IDP camp | 64 women of reproductive age | Not peer reviewed |

| IRC et al., 200353 | Interview questionnaire | SRH including GBV Demographic characteristics of women |

To estimate the prevalence of GBV in women and the consequences of such violence on mental, sexual and RH | Colombia – IDP from internal conflict | NA | Not peer reviewed |

| Jayatissa et al., 20067 | Cross-sectional, two-stage cluster, rapid assessment nutrition survey, interviewer administered questionnaire, anthropometrics, FGDs and KIIs | Maternal and neonatal health; Infant and child health Prevalence of acute and chronic malnutrition in children and under-nutrition among pregnant and lactating women |

For policy recommendation regarding setting up of nutritional surveillance systems | Sri Lanka – 42 tsunami relief camps | 875 children younger than five years; 168 pregnant women, 97 lactating women | Peer reviewed |

| JSI Research & Training Institute, 200254 | Questions from reproductive health response in crises and refugee reproductive health needs assessment field tools used in group discussions | SRH including GBV; Maternal and neonatal health; STI including HIV Status and availability of services regarding safe motherhood, family planning, SGBV, adolescent sexual and reproductive health, STIs/HIV |

To assess the RH needs and RH services | Democratic Republic of the Congo – IDP population in civil war | NA | Not peer reviewed |

| JSI Research & Training Institute, 200955 | Interviews and in-depth discussions with snowball sampling; no specific tools described | SRH including GBV; Maternal and neonatal health; STI including HIV Accessibility and availability of services regarding safe motherhood, family planning, SGBV, STIs/HIV |

To identify gaps in the availability and accessibility of comprehensive RH services | Haiti – hurricanes | NA | Not peer reviewed |

| Kalter et al., 200856 | Standardized questionnaire based on verbal autopsy formats; prospective monitoring of pregnant women and newborns from randomly selected clusters | Maternal and neonatal health Causes of neonatal and perinatal deaths, neonatal and perinatal mortality rates, including still births |

To identify risk factors for perinatal deaths | West Bank and Gaza strip – uprising | 926 women of reproductive age | Peer reviewed |

| Khalidi et al., 200457 | Stratified random sampling of 301 households (2025 families); Person-to-person interviews, household questionnaires and individual questionnaires | SRH including GBV Knowledge, attitudes and practice of domestic violence recognition, management and prevention |

Recommendations for the next steps of the project aimed at better understanding factors related to the severity of the domestic violence problem | Lebanon – refugee camps | 2018 individuals | Not peer reviewed |

| Kottegoda et al., 200858 | Interviews and structured questionnaire | SRH including GBV; Maternal and neonatal health RH concerns (early marriage, early pregnancy, miscarriage, home births and GBV) |

To highlight the voices of women who were shadowed by conflict | Sri Lanka – conflict | 560 women aged 12–60 years | Peer reviewed |

| Krause et al., 200359 | Reproductive health response in crises Reproductive Health assessment toolkit | SRH including GBV; Maternal and neonatal health; STI including HIV MISP services availability (sexual and gender based violence, family planning, safe motherhood, STI/HIVs) |

Data used for formulating policy recommendations | Colombia | 363 individuals | Not peer reviewed |

| Krause et al., 201160 | MISP assessment using reproductive health response in crises toolkit | SRH including GBV; Maternal and neonatal health; STI including HIV awareness about the need for MISP among international organizations; effectiveness of early disaster response; coordination of anti-GBV effort; availability of HIV/AIDS management, family planning, ANC and emergency obstetric care |

Assessment on effectiveness of SRH service delivery | Haiti – post-earthquake with long-term political instability | Not peer reviewed | |

| Lederman et al., 200861 | Interview; material hardship scale | Maternal and neonatal health data on maternal medical, obstetrics; birth weight, heights, head circumference and gestational duration |

Relationship of perceived air pollution and modelled air pollution to maternal characteristics and birth outcomes | USA – 400 different locations | NA | Peer reviewed |

| Lee, 200862 | KII with health care professionals from NGO and government facilities | SRH including GBV; Maternal and neonatal health Type of reproductive health service provision, delivery pattern, security issues of the service providers |

To explore the availability of services provided in long-standing internal conflict | Maguindanao, Philippines | 8 individuals | Peer reviewed |

| Longombe et al., 200863 | Review of hospital records of victims of sexual violence | SRH including GBV; including HIV Prevalence of fistula, sexually transmitted diseases |

Basis for formulating policy recommendations to develop a coordinated efforts among key stakeholders | Democratic Republic of the Congo – armed conflict and post conflict | 7 survivors | Peer reviewed |

| Mason et al., 200564 | Child anthropometry and survey with two-stage cluster sampling | Maternal and neonatal health; Infant and child health Prevalence of underweight |

Results of child malnutrition in six countries in southern Africa | Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Swaziland, Zambia and Zimbabwe – severe drought | NA | Peer reviewed |

| Mateen et al., 201265 | Data collected from the United Nations refugee assistance information system, ICD-10 | Infant and child health Common neurological disorders |

Diagnosis of common neurological disorders in refugees (men and women) | Jordan –refugees from Iraq | 31 476 individuals | Peer reviewed |

| Mateen et al., 201266 | Data collected from the United Nations refugee assistance information system | Maternal and neonatal health; Infant and child health Communicable and noncommunicable diseases, health service utilizations |

Determining the range infections and burden of health services use among adults and children (0–17years) | Jordan – refugees from Iraq | 7642 individuals | Peer reviewed |

| McGinn et al., 200167 | Interviews and self-administered questionnaires | SRH including GBV Acceptance of contraceptive methods by women; FP policies and management systems from organizations |

Six specific recommendations were formulated | Pakistan – Afghan refugee camps | NA | Not peer reviewed |

| Minetti et al., 200968 | Medecins Sans Frontieres programme monitoring data (medical records), physical examination | Infant and child health Weight, height and length of children, presence of oedema |

Evaluation of the change from National Center for Health Statistics to WHO 2006 growth standards children (6m-5y). Led to identification of a larger number of malnourished children at an earlier stage | Niger – severe malnutrition | NA | Peer reviewed |

| Mullany et al., 200869 | Population-based, cluster-sample surveys, FGDs, pregnancy records | SRH including GBV; Maternal and neonatal health; Infant and child health Basic demographics, obstetric history, human right violations |

Monitoring and evaluation of MOM project in delivering maternal health services by qualitative and quantitative methods | Myanmar – IDP and conflict | 59,042 individuals | Peer reviewed |

| Murray et al., 200970 | Study specific rapid health assessment tool (included), interviews | Infant and child health Surveillance of infectious diseases in hurricane evacuees |

To identify potential disease outbreaks | USA – hurricane | 29 478 individuals | Peer reviewed |

| Nichols et al., 201371 | Rapid assessment, mass screening, and convenience sample | Infant and child health Biochemical analysis of riboflavin from children and adults |

To provide guidelines for monitoring micronutrient deficiency in adults and children receiving food assistance | Uganda – drought | 179 172 individuals | Peer reviewed |

| Noe et al., 201372 | Retrospective aggregate of routine data collection, including the disaster health services aggregate morbidity report form | Maternal and neonatal health, Infant and child health Data on immediate medical needs of evacuees following hurricanes |

To identify health care delivery needs during a relief operation | USA – hurricane | 3863 individuals | Peer reviewed |

| Nsuami et al., 201373 | Cross-sectional, survey | STI including HIV Urine screening for gonorrhoea and chlamydia in high schools |

Prevalence of gonorrhoea and chlamydia before and after hurricane with the suggestion for STI screening immediately after natural disasters | USA – hurricane | 679 individuals | Peer reviewed |

| Patel et al., 201474 | Cross-sectional demographic and behavioural survey | STI including HIV testing; sexual behaviour |

Identified risk factors for HIV infection | Uganda – post-conflict transit camp | 384 adolescents | Peer reviewed |

| Physicians for Human Rights, 200975 | Quantitative and qualitative data from a non-probability sample, questionnaire, physical and psychological evaluation, interviews with stakeholders | SRH including GBV Physical and psychological consequences of rape and exposure to extreme violence |

Provide insight into the experiences and suffering and provided a basis for recommendations | Border between Chad and Sudan – refugee camps | 88 women | Not peer reviewed |

| Ravindranath et al., 200576 | Household survey using cluster sampling, anthropometry and physical examination | Infant and child health Underweight in school children, chronic energy deficiency in adults assessed by body mass index |

Assessment of nutritional status of community during drought and also evaluation of coping mechanisms by the intake of food and nutrient intakes | India – severe drought | NA | Peer reviewed |

| RHRC, 2004 AMDD77 | Facility assessment; AMDD tool | Maternal and neonatal health Availability of emergency obstetric care services |

To establish and improve basic and comprehensive emergency obstetric care services at health centres and hospitals responding to emergency obstetric needs of refugees and others of reproductive age living within and around the refugee community | Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kenya, Liberia, Pakistan, Sierra Leone, Sudan, Tanzania, Thailand and Uganda | NA | Not peer reviewed |

| RHRC, 2006 AMDD Program78 | Facility assessment; AMDD tool | Maternal and neonatal health Availability of emergency obstetric care services |

Monitoring and evaluation of basic emergency obstetric care at the health centre level and comprehensive emergency obstetric care at the hospital level was carried out to review emergency obstetric service delivery protocols | Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kenya, Liberia, Pakistan, Sierra Leone, Sudan, Tanzania, Thailand and Uganda | NA | Not peer reviewed |

| Rodriguez et al., 200679 | Survey using study specific questionnaire modelled after previous post-disaster surveys (EpiInfo3.2.2) | Infant and child health Individual on pre-existing medical and household characteristics |

To determine medical and social needs to allocate resources | USA –post–hurricane | 371 individuals | Peer reviewed |

| Saile et al., 201380 | Survey; structured interviews, standardized questionnaires, composite abuse scale, violence, war and abduction exposure scale, posttraumatic diagnostic scale; depression – Hopkins symptom checklist, alcohol use disorder identification test | SRH including GBV Frequency and types of abuse experienced |

Described partner abuse and predictor variables | Uganda – post-conflict | 470 individuals | Peer reviewed |

| Salama et al., 200181 | Two-stage cluster survey, standardized questionnaire | Infant and child health Crude mortality and mortality of children younger than five years, causes of death and anthropometric measurements |

To estimate major causes of deaths and prevalence of malnutrition among children and adults | Ethiopia – famine | 4032 individuals | Peer reviewed |

| Sawalha et al., 201382 | Cross-sectional survey; sociodemographic questionnaire, laboratory test | Infant and child health Blood lead levels; sociodemographics; general health |

Assessed blood lead levels | West Bank and Gaza strip – refugee camp | 178 children aged 6–8 years | Peer reviewed |

| Sherrieb & Norris, 201283 | Review of birth outcomes pre- and post-event | Maternal and neonatal health Birth weight and preterm births |

Impact of terrorist attacks on population health | USA – terrorist attack | NA | Peer reviewed |

| Spiegel et al., 201484 | Surveillance survey; descriptive data analysis, multivariable logistic regression | Maternal and neonatal health Sexual history and behaviour, HIV knowledge and testing, refugee type and length, interaction between groups |

Identified factors independently associated with multiple sexual partnerships | Botswana, Kenya, Mozambique, Nepal, Rwanda, South Sudan, Sudan, Tanzania, Uganda – refugees | 24 219 individuals | Peer reviewed |

| Sullivan et al., 200485 | Adapted reproductive health response in crises Reproductive health needs assessment field tools | Maternal and neonatal health Data on catchment area, SRH service availability and coverage including staffing, equipment and supplies, client perception |

To improve RH and building clinic capacity in monitoring and evaluation | Border between Myanmar and Thailand – illegal immigrant workers and IDPs | 462 women | Peer reviewed |

| Talley & Boyd 201386 | Retrospective record review; standardized, study specific, data collection tool | Maternal and neonatal health Demographics, admission criteria, primary caretaker, infant feeding practices, anthropometrics |

Evaluation of infant feeding programme | Haiti – earthquake | 493 infants | Peer reviewed |

| Tan et al., 200987 | Analysis of birth records | Maternal and neonatal health Birth weight, APGAR score, pre- and post-event |

Effects of earthquake on birth outcomes | China – earthquake | 13 003 neonates | Peer reviewed |

| Tappis H et al., 201288 | Secondary data analysis of UNHCR Twine database | Infant and child health Growth and nutrition data on the refugee camp population |

Effectiveness of the coverage of UNHCR supplementary and therapeutic feeding programmes for the malnourished children | Kenya and Tanzania –refugees | 39 899 children younger than five years | Peer reviewed |

| Teela et al., 200989 | FGDs and detailed case studies with maternal health workers; no specific tools described | 11=SRH including GBV,2; 2=Maternal and neonatal health Characteristics of maternal health workers in conflict settings, their efforts on community mobilization, provision of emergency obstetric care and technical competence, security and logistical constraints, programme successes |

To complement project quantitative information and provide contextual information of the community maternal health workers’ challenges in implementation | Eastern Myanmar – conflict | 41 health workers | Peer reviewed |

| Tomczyk et al., 200790 | Population-based survey of a sample of 36 primary sampling units; CDC RH assessment toolkit | SRH including GBV; Maternal and neonatal health; STI including HIV Social background, maternal health, contraception, violence; HIV/AIDS knowledge, attitudes, and risk behaviours |

Policy recommendations regarding continuous funding when traditional humanitarian aid is limited or withdrawn | Liberia – post-protracted armed conflict and transitional years | 907 women of reproductive age | Not peer reviewed |

| Turner et al., 201391 | Informal staff interviews | Infant and child health Admission diagnosis and characteristics, treatment provided |

Impact of introduction of special care baby unit on refugee population | Myanmar – refugees | 952 infants | Peer reviewed |

| Turner et al., 201392 | Laboratory-enhanced, hospital-based surveillance; Patient interview, record review | Infant and child health Patient symptoms, nasopharyngeal aspirates, pyrexia, respiration rate |

Characterization of the epidemiology of respiratory virus infections in refugees | Border between Myanmar and Thailand – refugees | 635 children younger than five years and 68 children older than 5 years | Peer reviewed |

| UNHCR et al., 201193 | Health facility assessment, IDIs, FGDs and household surveys; CDC RH assessment tool | SRH including GBV Knowledge, beliefs, perceptions and practices surrounding family planning |

To improve programming and subsequently increase uptake of good quality family planning services | Kenya – refugees from Somalia | NA | Not peer reviewed |

| UNHCR et al., 201194 | Health facility assessment, IDIs, FGDs and household surveys; CDC RH assessment tool | SRH including GBV Knowledge, beliefs, perceptions and practices surrounding family planning |

To improve programming and subsequently increase uptake of good quality family planning services | Jordan – refugees from Iraq | NA | Not peer reviewed |

| UNHCR et al., 201195 | Health facility assessment, IDIs, FGDs and household surveys; CDC RH assessment tool | SRH including GBV Knowledge, beliefs, perceptions and practices surrounding family planning , the state of service provision |

To improve programming and subsequently increase uptake of good quality family planning services | Djibouti – refugees from Somalia | NA | Not peer reviewed |

| UNHCR et al., 201196 | Health facility assessment, in-depth interviews, focus group discussions and household survey; CDC RH assessment tool | SRH including GBV; Knowledge, beliefs, perceptions and practices surrounding family planning, the state of service provision |

To improve programming and subsequently increase uptake of good quality family planning services | Uganda – refugees from the Democratic Republic of Congo | NA | Not peer reviewed |

| UNHCR et al., 201197 | Health facility assessment, in-depth interviews, focus group discussions and household survey; CDC RH assessment tool | SRH including GBV Knowledge, beliefs, perceptions and practices surrounding family planning, the state of service provision |

To improve programming and subsequently increase uptake of good quality family planning services | Malaysia – refugees from Myanmar | NA | Not peer reviewed |

| Usta et al., 201098 | The international child abuse screening tool (International Society for the Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect (IPSCAN-2007) was translated from English into Arabic | SRH including GBV Child sexual abuse pre and post-conflict |

The prevalence, risk factors and consequences of child sexual abuse in Lebanese children | Lebanon | 1028 children aged between 8–17 years | Peer reviewed |

| Wainstock et al., 201399 | Retrospective cohort study; Interviews | Maternal and neonatal health sociodemographics, smoking, perceived stress, clinical data from hospital records |

Evaluation of the association between prenatal maternal stress and preterm birth and low-birth weight | Israel – conflict (rocket attacks) | 125 women | Peer reviewed |

| Ward, 2002100 | Interviews with IDP and actors; no specific tools described | SRH including GBV Overview of GBV findings globally |

To inform of services available and programming gaps relating to gender based violence in conflict-affected populations | Border between Afghanistan and Pakistan, Azerbaijan, Bosnia and Herzegovina Democratic Republic of the Congo, border between Myanmar and Thailand Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Timor Leste, – conflict affected populations | NA | Not peer reviewed |

| Wayte et al., 2008101 | IDI, service statistics and document review; No specific tool described | SRH including GBV; Maternal and neonatal health; STI including HIV RH service provision, coordination and priority setting; ANC; Maternity waiting home; Family planning; STIs, HIV/AIDS; Gender based violence, adolescent health |

To assess the health sector’s response to RH | Timor Leste | 35 individuals | Peer reviewed |

| Wilson et al., 2013102 | Retrospective review of paediatric registry records | Infant and child health Demographics, mechanism of injury, clinical and laboratory data, diagnostic and surgical procedures, complications and outcomes |

Review of paediatric trauma in a combat support hospital | Afghanistan – conflict | 41 children aged between 1–18 years | Peer reviewed |

| Wirtz et al., 2013103 | IDIs, FGDs | SRH including GBV; Prevalence of GBV, physical and psychological consequences of GBV |

To inform the development of a screening tool as a potential strategy for addressing GBV | Ethiopia – refugees from Somalia, post-conflict | 144 individuals | Peer reviewed |

| Women’s Commission, 2002104 | Reproductive health needs assessment field tools | SRH including GBV; Maternal and neonatal health; STI including HIV Status and availability of services regarding safe motherhood, family planning, SGBV, adolescent SRH, STIs/HIV |

To assess RH | Zambia – civil war refugees from Angola and Democratic Republic of Congo | NA | Not peer reviewed |

| Women’s Commission, 2003105 | Based upon RHRC toolkit | SRH including GBV; Maternal and neonatal health; STI including HIV Family planning, SGBV, Adolescent SRH, safe motherhood, STI, HIV; Availability of instructional resource materials |

Data for policy recommendations and to identify their problems in assessing the services | Pakistan – Refugees from Afghanistan | NA | Not peer reviewed |

| Women’s Commission, UNFPA, 2004106 | Semi-structured interview, FGD, and health facility assessment; MISP assessment tool kit | SRH including GBV; Maternal and neonatal health; STI including HIV Status and availability of services under MISP; Coordination among RH service providers |

To evaluate the implementation of the MISP and the use of RH kits | Chad – refugees from South Sudan | 108 individuals | Not peer reviewed |

| Women’s Commission, 2005107 | Cross sectional, interviews and FGD, No specific tools described | SRH including GBV, Maternal and neonatal health STI including HIV Status and availability of services under MISP; Coordination among RH service providers |

To assess the implementation of MISP activities, and the agency staffs’ understanding of MISP | Indonesia – tsunami | 77 individuals | Not peer reviewed |

| Women’s Commission, 2007108 | Structured interviews, meetings with representatives of local and international NGOs, 10 focus groups with displaced persons; visits to local facilities | SRH including GBV; Maternal and neonatal health; STI including HIV SRH service availability and use in family planning, SGBV, safe motherhood, STIs and HIV/AIDS |

Basis for formulating recommendations regarding: funding, coordination, staffing, training, RH equipment and supplies, safe motherhood, FM, STIs and GBV | Northern Uganda – protracted civil war | 140 females and youths | Not peer reviewed |

| Women’s Commission, 2008109 | Cross sectional, interviews, FGD and observations. MISP | SRH including GBV; Maternal and neonatal health; STI including HIV Sexual violence, HIV, maternal and newborn morbidity and mortality |

The purpose of the assessment was to examine the degree of implementation of the MISP for RH | Kenya | 139 individuals | Not peer reviewed |

| Women’s Wellness Centre & RHRC, 2006110 | Household survey of women of reproductive age | SRH including GBV; Estimates of sexual and physical violence prevalence |

Data obtained used for formulating policy recommendations | Nine villages in Peja region, Serbia – conflict, displacement and post-conflict setting | 332 women of reproductive age | Not peer reviewed |

AMDD: Averting Maternal Death and Disability, ANC: Antenatal Care, ARI: Acute Respiratory Infection, BMI: Body Mass Index, CDC: Centers for Disease Control, FGD: Focus Group Discussions, FP: Family Planning, GBV: Gender Based Violence, HIV: Human Immunodeficiency Virus, ICD-10: International Classification of Diseases 10th edition, IDI: In-depth Interview, IDP: Internally Displace People, IPV: Intimate Partner Violence, KII: Key Informant Interviews, M&E: Monitoring and Evaluation, MISP: Minimum Initial Service Package, NA: not available, NGO: Nongovernmental organizations, PNC: Postnatal care, RH: Reproductive Health, RHRC: Reproductive Health Response in Crises Consortium, RTI: Reproductive Tract Infections, SGBV: Sexual and Gender Based Violence, SRH: Sexual and Reproductive Health, STI: Sexually Transmitted Infection, U5: Under five years of age

Data were collected from refugee populations in the recovery phase. Our review did not identify any studies that collected data during the disaster preparedness phase, which is defined by UNFPA as, “the period preceding a humanitarian crisis – use of early warning signals to avert crises or prepare response”.111 Seventy-six studies examined the health status of the population affected, while 24 examined the availability and coverage of health services, usually measured using the minimum initial service package.60 A variety of indicators were collected with some studies using specific toolkits for field settings (Table 2).

Table 2. Data collection tools used and type of data collected for maternal and child health during humanitarian emergencies.

| Category | Type of data collected | Tool application described in the literature |

|---|---|---|

| Sexual and reproductive health | ||

| Family planning28,35,49,52,54,55,58–60,62,67,69,93–97,101,104–109 | SRH including MNCH, availability and accessibility of modern contraceptives, couple discussion on methods of choice, unplanned pregnancy, knowledge, attitude and practices of family planning, security of family planning. | CDC RH assessment toolkit for conflict-affected women, RHRC RH needs assessment field tools, MISP assessment |

| Sexual and gender-based violence 15,16,22,24,25,33,37,39,43,44,53–55,58–60,63,75,80,90,98,100,101,103–110,112 | Prevalence of child sexual abuse, risk factors of sexual and gender-based violence, patterns of sexual and gender-based violence, awareness among aid workers of sexual and gender-based violence, efficiency of response and coordination among agencies, availability and accessibility of services for sexual and gender-based violence victims, intimate partner violence and associated factors, physical consequences of sexual and gender-based violence (fistula and infections), mental consequences. | MISP assessment toolkit, AUDIT (The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for Use in Primary Care), Measuring Intimate Partner Violence Victimization and Perpetration: A Compendium of Assessment Tools (CDC, 2006). |

| Maternal and newborn health | ||

| Emergency Obstetric Care34,60,77–79 | Number of deliveries at health facilities, caesarean section rate, availability of blood transfusion, obstetric complications managed, manual vacuum aspiration procedures performed, maternal deaths. | Emergency obstetric and newborn care assessment toolkit from the Averting Maternal Death and Disability (AMDD) programme. |

| Newborn health46,56,83,87,91 | Birth outcomes, birth defects. | No description of specific tools used. |

| General maternal and newborn health 7,12,18,21,27,28,37,38,43,44,46,52–55,58–62,64,66,69,72,85–87,90,99,101,104–110 | Logistics and security issues, antenatal care, maternal height and weight, vitamin A during pregnancy, iron and folate supplementation, malaria during pregnancy, anaemia during pregnancy, human rights violations, barriers to receiving care. | RHRC RH needs assessment field tools, MISP assessment toolkit. |

| Infant and child health | ||

| Nutrition7,12,13,20,21,30,36,45–48,51,64,68,69,71,72,76,79,81,82,88 | Weight, height and mid upper arm circumference (MUAC) of children, vaccination status of children, presence of oedema, haemoglobin levels, other infections (acute respiratory infections, diarrhoea), other nutritional and micronutrient deficiency, feeding practices (exclusive breastfeeding, complementary feeding), food assistance and food security. | No description of specific tools used. |

| Infections12,14,19,26,30,32,42,66,70,92 | Socioeconomic factors, demographic factors, diarrhoea and waterborne infections, acute respiratory infections and diseases of adenoids, visual disturbances, urinary problems, malaria treatment and use of insecticide-treated nets. | No description of specific tools used. |

| Injuries29,38,40,41,50,102 | Types of injuries, care seeking behaviour, intentional injuries including context, when and how it occurred, weapon used, relationship with perpetrator, injuries by landmines and unexploded ordinances (time, place and how it happened, type and site of injury), need for blood transfusion | No description of specific tools used. |

| Miscellaneous31,46,47,65 | Lead poisoning (blood-lead level, chelation therapy), medical health conditions, mental child health conditions, neurological disorders including epilepsy, infantile cerebral palsy. | No description of specific tools used. |

| Sexually transmitted infections including human immunodeficiency virus infection (HIV) and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)17,23,28,33,39,52,54,55,59,60,63,73,74,90,101,104–109 | Availability and accessibility of HIV/AIDS management, knowledge and attitudes on HIV/AIDS, risk behaviour on HIV/AIDS, prevalence of sexually transmitted infections as consequence of sexual and gender based violence, availability of resource materials for sexually transmitted infections and HIV, prevalence of gonorrhoea and chlamydia. | MISP assessment toolkit. |

AIDS: acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; CDC RH: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Reproductive Health; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; MISP: minimum initial service package; MNCH: maternal, newborn and child health; RH: reproductive health; RHRC: reproductive health response in conflict; SRH: sexual and reproductive health

Data were collected for monitoring and evaluation purposes in 69 studies. In 18 studies, data were collected for the purpose of advocacy; seven studies were operational research and six studies described a needs assessment. No studies that we identified had the primary aim of collecting data to support a funding request.

Data collection tools

We identified a total of 17 different tools which were mainly structured questionnaires (Table 3). Among 100 included studies, 19 specified the use of any of the 17 identified tools. Eight studies used a rapid assessment field tool;55,59,60,85,104–106,109 seven used the assessment toolkit for conflict affected women35,90,93,94–97 and three used the emergency obstetric care assessment toolkit from the averting maternal disability and deaths programme.34,77,78 The alcohol use disorders identification test;112 the compendium for measuring intimate partner violence victimization and perpetration122 and Twine (a web-based toolkit developed by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees)4 were used in one study each. The remaining 79 studies did not specify which tools had been used to collect the data.

Table 3. Summary of data collection tools for maternal and child health in humanitarian emergencies, by year of publication .

| Existing tools for data collection identified from the literature review | Type of data that can be collected |

Suitable in acute phase of an emergency | Field application reported | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sexual & reproductive health including gender-based violence | Maternal and newborn health | Infant and child health | Sexually transmitted infections | |||

| Twine (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, 2014)4 |

Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Refugee health: an approach to emergency situationsa

(Médecins Sans Frontières, 1997)113 |

Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| Refugee RH needs assessment field tools (Reproductive Health Response in Crises Consortium, 1997)114–117 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| The alcohol use disorders identification test: guidelines for use in primary health care (Babor, 2001)112 |

Yes | Yes | ||||

| SGBV Tools for refugees, returnees and IDPs (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, 2003)118 |

Yes | Yes | ||||

| EmOC needs assessment tool (Women’s Commission and Averting Maternal Death and Disability, 2005)119 |

Yes | Yes | ||||

| GBV prevention and response tool in emergencies (Inter-Agency Standing Committee, 2005)120 | Yes | Yes | ||||

| Guidelines on public health promotion in emergencies (Oxfam, 2006)121 | Yes | Yes | ||||

| Measuring intimate partner violence victimization and perpetration: a compendium of assessment tools (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2006)122 | Yes | Yes | ||||

| Adolescent SRH toolkit for humanitarian settings (United Nations Population Fund and Save the Children Fund, 2010)123 | Yes | Yes | ||||

| GBV programme monitoring tool, (United Nations Population Fund, 2010)124 |

Yes | |||||

| Inter-agency field manual on RH in humanitarian settings (WHO Interagency Working Group on Reproductive Health in Crises, 2010)125 |

Yes | |||||

| MISP assessment toolkit (Interagency Working Group on Reproductive Health in Crises, 2010)126 |

Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| RH assessment toolkit for conflict-affected women, (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011)127 | Yes | Yes | ||||

| Sphere handbook (The Sphere Project, 2011)128 |

Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Guide to MNCH and nutrition in emergencies (World Vision, 2012)1 |

Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| GBV tools manual for assessment and program design, monitoring and evaluation in conflict-affected settings (Reproductive Health Response in Crises Consortium, 2005)129 |

Yes | |||||

EmOC: emergency obstetric care; GBV: gender-based violence; IDP: internally displaced persons; MISP: minimum initial service package; MNCH: maternal, newborn and child health; RH: reproductive health; RHRC: reproductive health response in crises consortium; SGBV: sexual and gender-based violence; SRH: sexual and reproductive health; WHO: World Health Organization.

a General toolkits that do not exclusively assess SRH or MNCH.

Of the 17 toolkits identified (Table 3), 14 could be used to collect data on sexual and reproductive health, eight on maternal and newborn health, four on child health and seven on sexually transmitted infections and HIV. Some of the tools were designed to collect more than one category of data (e.g. Twine). Of the 14 tools used for data collection on sexual and reproductive health, four were specifically designed for gender-based violence. A further 13 studies also collected data on gender-based violence, but no data collection tool was identified.

Similarly, there was no specific tool to collect child health data, but four toolkits had questionnaires that included the collection of some data on child health data. Twine contains a specific section for child health data collection, including nutrition.4 Refugee health: an approach to emergency situations113 is designed to collect data on children for diseases under surveillance, nutritional status and common communicable diseases. The Sphere handbook128 has rapid assessment tools to collect health service assessment data as well as sample surveillance reporting forms. These can be used to collect information on children younger than five years and provide outbreak alerts for this age group. These tools incorporate early warning and response network surveillance for early detection of epidemic-prone diseases in emergency settings. We did not identify specific tools for sexually transmitted infections and HIV, but relevant data are collected as part of seven of the more general sexual and reproductive health toolkits.130

Discussion

Our review provides an overview of the data collection tools available as well as the published experience of the use of these tools. We advocate the use and harmonization of existing tools rather than the development of new tools. As we could not identify any studies reporting on data collection for disaster preparedness or disaster response, there is a need to adapt existing tools or develop new tools to facilitate data collection specifically for these phases. We excluded tools used primarily in non-humanitarian settings and may not have captured all available tools or data collected in humanitarian emergency settings.

Most of the tools specify which methods are needed to collect the required data, including both quantitative and qualitative methods in specific contexts. The methods used depend upon the purpose of data collection, the available resources and the nature of the information sought. Table 4 summarizes commonly reported methods to collect data during an emergency.130

Table 4. Approaches and methods for the collection of data during humanitarian emergencies.

| Approach | Methods | Data sources |

|---|---|---|

| Qualitative | Key informant interviews | Key stakeholders (e.g. health service providers, policy- and decision-makers) |

| Focus group discussions | Affected population | |

| Mixed Method | Observational study | Affected population and area |

| Inventory or document review | Previous available data (e.g. surveys, health sector data, programme reports) | |

| Quantitative | Secondary data analysis | Previous available data (e.g. surveys, health sector data, programme reports) |

| Rapid counting | Affected population | |

| Aerial surveillance | Affected area | |

| Flow monitoring | Affected population | |

| Enumeration or profiling | Affected population |

Of the 100 studies included in this review, only 19 described the data collection tools used and only six commented on their applicability in field settings. Authors may not be aware of the existence of a wide range of toolkits, or the importance of documenting their experiences.

To improve the response to humanitarian emergencies, target groups need to be identified and their specific needs understood. For sexual, reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health the underlying contexts which prevent or enable access to services also need to be considered.130 The international humanitarian community continues to highlight the importance of documenting and addressing the problem of sexual and gender-based violence.37 A central repository of data collected during a humanitarian emergency, where a core set of indicators is agreed on, would be useful. The repository would allow any user to submit or explore data to inform decision-making and enable comparisons between and across settings.

Only eight studies were conducted within the first six months of a humanitarian emergency. The majority of studies (69/100) and data collected were used to monitor and evaluate ongoing interventions. This may reflect the necessity of providing immediate life saving measures during the early stages of humanitarian emergencies. Rapid assessments are vital in the early stages of humanitarian emergencies. Information is required to highlight changing needs to inform appropriate provision of relief and urgent medical assistance. Most importantly, rapid assessment tools need to be simple to use.131

It is encouraging to note that the tools developed so far seem to have used a cluster approach for data collection. Introduced in 2006 as part of the UN Humanitarian Response, a cluster is defined as:

“a group of agencies that gather to work together towards common objectives within a particular set of emergency response”.132

The approach aims to improve the effectiveness of humanitarian assistance by improving predictability and timeliness of a response process through a coordinated effort.111 The cluster approach can strengthen accountability among key actors and enhance the complementary nature of different organizations involved in providing humanitarian assistance. Although the health and nutrition clusters are critical for maternal, newborn and child health, the available tools consider other clusters as cross-cutting areas including protection, water and sanitation, camp coordination and management.132

Conclusion

There is a need to evaluate, standardize and harmonize existing data collection toolkits and to develop others that can be used in the response phase of humanitarian emergencies. Information is needed on the applicability of existing tools in relation to the types of populations and the emergency situations in which they are used. It would be useful to develop shortened versions of existing tools adapted specifically to use in the response phase, together with a more comprehensive version for the later phases of an emergency. Humanitarian assistance reports should include analyses of the lessons learnt when using data collection toolkits. This information can assist modification of existing tools and development of new tools. Whenever new toolkits are developed by interagency working groups, it is important to take the perspectives of field users into account. Wider dissemination of the availability of data collection tools among humanitarian workers can be achieved by educating staff at headquarters and country offices of humanitarian organizations, or by including the toolkits in disaster risk reduction training.

To plan and evaluate interventions and actions that will save lives in humanitarian emergencies, appropriate data are needed. To ensure that tools used to obtain such data are easy to use and comprehensive, it is essential that both individuals involved in field operations and in operations research continue to work together. New standardized tools should be developed and existing ones adapted based upon standards for data collection in emergencies with inputs from humanitarian agencies.111 This work could be coordinated by WHO.

Funding:

This work was funded by the World Health Organization, reference number 200833146.

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.Guide to maternal, newborn and child health and nutrition in Emergencies. Uxbridge, England: World Vision; 2012 Available from: http://wvi.org/child-health-now/publication/maternal-newborn-and-child-health-and-nutrition-emergencieshttp://[cited 2015 July 13].

- 2.Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre. Geneva: Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre; 2014. Available from: http://www.internal-displacement.org/ [cited 2015 May 14].

- 3.Using data to improve humanitarian decision making. Geneva: United Nations Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA); 2013. Available from: http://reliefweb.int/report/world/overview-global-humanitarian-response-2014-enfrsp [cited 2014 May 14].

- 4.Overview of global humanitarian response. Geneva: the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR); 2014. Available from: http://twine.unhcr.org/app/ [cited 2015 May 14].

- 5.Humanitarian action for children. New York: United Nations Children’s Fund; 2014. Available from: http://www.unicef.org/appeals/files/HAC_Overview_2014_WEB.pdf [cited 2015 May 14].

- 6.Toole MJ, Waldman RJ. The public health aspects of complex emergencies and refugee situations. Annu Rev Public Health. 1997;18(1):283–312. 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.18.1.283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jayatissa R, Bekele A, Piyasena CL, Mahamithawa S. Assessment of nutritional status of children under five years of age, pregnant women, and lactating women living in relief camps after the tsunami in Sri Lanka. Food Nutr Bull. 2006. June;27(2):144–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Altay N, Labonte M. Challenges in humanitarian information management and exchange: evidence from Haiti. Disasters. 2014. April;38(s1) Suppl 1:S50–72. 10.1111/disa.12052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Esscher AO. Reproductive health in humanitarian assistance: a literature review. Uppsala: Centre for Public Health in Humanitarian Assistance, Uppsala University; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lucas PJ, Baird J, Arai L, Law C, Roberts HM. Worked examples of alternative methods for the synthesis of qualitative and quantitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7(1):4. 10.1186/1471-2288-7-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The PRISMA Statement [Internet]. York, UK: Prospero; 2014. Available from: http://www.prisma-statement.org [cited 2015 July 13].

- 12.Abdalla F, Mutharia J, Rimal N, Bilukha O, Talley L, Handzel T, et al. ; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Malnutrition and micronutrient deficiencies among Bhutanese refugee children–Nepal, 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008. April 11;57(14):370–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abdeen Z, Greenough PG, Chandran A, Qasrawi R. Assessment of the nutritional status of preschool-age children during the second Intifada in Palestine. Food Nutr Bull. 2007. September;28(3):274–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abu Mourad TA. Palestinian refugee conditions associated with intestinal parasites and diarrhoea: Nuseirat refugee camp as a case study. Public Health. 2004. March;118(2):131–42. 10.1016/j.puhe.2003.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amowitz LL, Reis C, Lyons KH, Vann B, Mansaray B, Akinsulure-Smith AM, et al. Prevalence of war-related sexual violence and other human rights abuses among internally displaced persons in Sierra Leone. JAMA. 2002. January 23-30;287(4):513–21. 10.1001/jama.287.4.513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]