Abstract

Context

Community education may involve activities that seek to raise awareness and promote behavior change, using mass media, social media, and other media or interpersonal methods in community settings. This systematic review evaluated the evidence of the effects of community education on select short- and medium-term family planning outcomes.

Evidence acquisition

Using an analytic approach drawn from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, multiple databases were searched for articles published from January 1985 through February 2011 describing studies of community education related to family planning in the U.S. Included articles were reviewed and assessed for potential bias using a standardized process in 2011. An updated, targeted review for the 2011–2014 period was conducted in early 2015.

Evidence synthesis

Seventeen papers were identified. Most (nine) related to mass media interventions; three involved targeted print media, two involved text messaging or e-mail, two described outcome workers conducting community education, and one involved community theater. Study designs, strength of evidence, and levels of possible bias varied widely. Twelve of 15 studies that addressed outcomes such as increased awareness found positive associations with those outcomes, with six also reporting null findings. Seven of eight studies that addressed use of services reported positive associations, with two also reporting null findings. The targeted, additional review identified two other studies.

Conclusions

Evidence related to community education for family planning purposes is limited and highly variable. As goals of community education are usually limited to shorter-term outcomes, the evidence suggests that a range of approaches may be effective.

Context

In a family planning context, community education may include activities conducted outside the clinical setting, often with the aim of informing potential and current clients about the availability of services and promoting understanding and utilization of family planning. In this sense, community education relates to the concepts of both advertising and social marketing. Often considered a form of outreach, community education typically uses media channels and interpersonal approaches to achieve its aims. Media channels may include traditional mass media such as TV and radio and extends to “new” media such as e-mail, Internet, social networking sites, and text messaging. Print media can include the use of newspaper, magazines, and pamphlets. Interpersonal approaches may include small group education sessions and one-on-one outreach that occur through peer educators or other outreach workers.

Title X regulations specifically state that all funded family planning projects must “provide for informational and educational programs designed to achieve community understanding of the objectives of the program; inform the community of the availability of services; and promote continued participation in the project by persons to whom family planning services may be beneficial.”1 To better evaluate the value of community education within the U.S. family planning field, we undertook this systematic review to assess the evidence regarding whether and how community education on family planning affects those kinds of health outcomes.

Evidence Acquisition

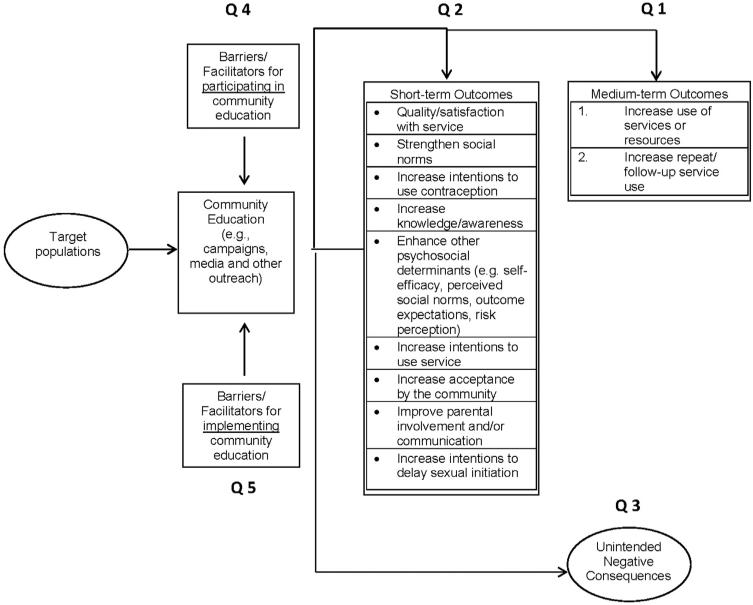

The review relied on a set of key questions and an analytic framework that also guided other reviews in this series (Table 1).2 The first two key questions relate to whether community education efforts are associated with specific outcomes, including those that were considered medium-term (Q1, in this case, reported outcomes focused on increased use of services only, though the broader analytic framework guiding this series of reviews included others such as contraceptive and condom use), and those that were considered shorter-term (Q2, e.g., knowledge of family planning methods). Three other key questions pertain to potential unintended consequences of community education (Q3), as well as barriers and facilitators that clients face with participation (Q4) and that health centers face in implementing community education activities (Q5). Based on analytic frameworks developed by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), Figure 1 shows the logical relationships among the population of interest, the interventions of interest, and the outcomes of interest.3 The numbered lines in the framework map to the key questions addressed in the review. All summary measures reporting relevant outcomes were considered for review.

Table 1.

Key Questions of the Systematic Review

| Key question no. | Question |

|---|---|

| 1 | Does community education result in improved, select medium-term outcomes of family planning services? |

| 2 | Does community education result in improved short-term outcomes of family planning services? |

| 3 | Are there unintended negative consequences of community education in family planning program development and review? |

| 4 | What are the barriers and facilitators facing clients in participating in community education activities? |

| 5 | What are the barriers and facilitators facing health centers in adopting and implementing community education activities? |

Figure 1.

Analytic framework and key questions guiding the community education systematic review.

Search terms unique to this review included Medical Subject Headings and free-text terms such as social marketing, health communication, public relations, health education, and outreach (full list in Appendix A). These were combined with the family planning–specific terms (e.g., family planning, contraception) and those related to the various outcomes of interest (e.g., health behavior, intention, contraceptive behavior, utilization, pregnancy) to search for appropriate studies. Appendix B lists several electronic databases used to identify potential articles to include in this systematic review.

To preserve the relevance of this review to national family planning efforts in the U.S., we chose not to review studies that pertained only to HIV or sexually transmitted disease (STD)–related community education. However, we did include studies that focused on condom use or sexual health promotion, when it was done not solely for HIV or STD prevention but also included pregnancy prevention messaging as a component. We also limited the geographic locations of studies to North America, Europe, Australia/New Zealand, or Japan. Finally, we opted not to review the evidence related to small-group, curriculum-based reproductive and sexual health education conducted in schools or related community settings, primarily because recent syntheses of that literature already exist.4,5

Information on the method of reviewing and abstracting data from studies, assessing study quality and risk of bias, and summarizing those are described elsewhere.2 Briefly, we used a system based primarily on the USPSTF to assess the level of evidence.3 We did not compute summary measures of association across studies because of diversity of interventions, study designs, populations, and outcomes. The primary analysis was conducted in 2011.

Evidence Synthesis

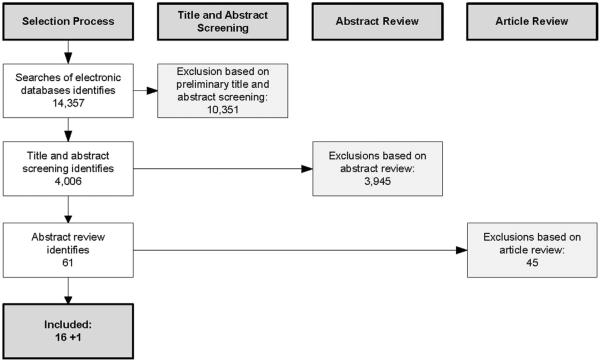

The initial search yielded 14,357 abstracts (Figure 2). This search included terms related to both community education and community engagement, the results for which are described elsewhere.6 After reviewing titles and abstracts, we excluded 10,351 papers. An additional 3,945 were excluded after reading abstracts more closely, for a total of 61 papers that we retrieved for this topic. Sixteen met our inclusion criteria. We added one study that came out shortly after the initial search was conducted, but prior to the presentation of the results to a technical panel convened to discuss this evidence and related issues.7

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of the systematic review process for community education.

Included studies were diverse in terms of their aims and the intervention being evaluated, as well as the evaluation approach. Five were focused on raising awareness about emergency contraception (EC),8–12 and four were focused on condom promotion.13–16 Two were focused on increasing parental communication with their children about sex,17,18 and two were focused on increasing reproductive health service use.19,20 One was aimed at delaying sexual debut,21 and three were aimed at increasing sexual health knowledge and related behaviors.7,22,23 Most of the included studies evaluated interventions that were primarily mass media-focused,8–12,16–18,21 whereas three had interventions involving largely targeted print media.13–15 Two studies had interventions involving a major component with outreach workers19,20; two involved largely text messaging or e-mail.7,22 One was about a community theater event.23 Many used time series cross-sectional study designs, some with comparison or control groups,9,10,16 and others without.8,12,13,19,21 Four used an RCT design,7,14,15,18 two were retrospective cohort studies,17,20 one was a longitudinal cohort study,11 and two used pre–post designs.22,23 Nine studies were classified as high risk of bias, because of aspects of their study design and data collection procedures, and seven were classified as moderate risk. One was classified as low risk.15 Appendix C provides detailed information on the study design, interventions, and results from each study, and Table 2 synthesizes the main results across studies by outcome and type of intervention.

Table 2.

Community Education Systematic Review: Synthesis of Findings

| Primary mode of community education |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mass media (TV/Radio/Billboards) | Targeted print media/mail | Outreach worker | Text messaging/email | Theatre | |

| Number of studies where mode of outreach was primary mode (n=17) | 9 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Impact on | |||||

| Awareness and knowledge | ++++ | +0 | ++ | + | |

| Intentions to use contraception/condoms | +++ | 0 | +/0 | ||

| Enhance other psychosocial determinants (e.g., attitudes, risk perceptions) | ++ | + | |||

| Parent-child communication |

0/+ 0/+ |

||||

| Select medium-term outcomes | |||||

| Use of family planning-related resources (website, hotlines, condom mail service) | ++0 | + | |||

| Use of family planning and/or STD services | ++ | + +/0 |

|||

Note: Each symbol = 1 study, except where there is a “/”, which indicates a single study that had mixed results for that outcome. + community education had a positive impact on this outcome; − community education had a negative impact on this outcome; 0 community education had neither positive nor negative impact on this outcome.

Use of Services or Resources

Four studies examined associations between interventions with community education components and the use of different kinds of family planning–related health services, and all identified positive associations. In a retrospective cohort study20 of an intervention that involved various levels of peer and community outreach support in California, those who received the full model (i.e., Group 4, which received peer-led telephone and community outreach services) were more likely to have returned to the clinic for an annual exam (AOR=2.19, p<0.01) and to have returned for three or more clinic visits (AOR=1.70, p<0.05), over the course of the observation period, compared with those who only received the peer-led clinic intake service. In a different study19 from the United Kingdom that examined the combined effect of outreach workers promoting service availability (particularly among youth-serving organizations) and a consolidation of services at a single clinic with more clinic hours on service utilization, the number of new clients rose from 1,091 at the four clinics in the 1 year prior to consolidation to 2,297 at the one clinic after consolidation. Also, the percentage of new clients aged <20 years increased at the consolidated clinic.

Two studies examining electronic messages promoting sexual health among adolescents and young adults reported that testing for STDs increased. In a study22 that involved a series of text messages and a pre–post study design, self-reported STD testing rose significantly for both men and women (from 18% to 23% among women; from 8% to 10% among men). In another study7 that involved a series of text and e-mail messages and an RCT design, self-reported STD testing in the prior 6 months rose significantly for women (from 9% to 18%), as did the percentage that reported having talked with a healthcare provider about contraceptive or sexual health in the previous year (37% to 60%). There was no evident effect of that intervention on men's behaviors.

Four other studies reported on interventions designed to increase uptake of family planning–related resources (vs. health service uptake), and all found positive associations. In a study that randomized parents to two groups (note that mothers were further randomized to two levels of intervention exposure), parents who had received information about a parenting website as part of the public service announcements (PSAs) they were exposed to reported higher use of that website.18 Similarly, in a multicity, mass media campaign promoting knowledge about EC and a related telephone hotline, calls to the hotline more than doubled over the course of the intervention, particularly in cities that had paid TV advertising (e.g., 5,247% increase in one paid advertising city during the campaign).12 Hall and Milner's9 study of an EC campaign also promoted use of a new hotline. They recorded 44 calls to the EC hotline during the main hours of operation as a result of the intervention, and an additional 233 calls that came after hours, for which callers received only a recorded message. Finally, an intervention involving a direct mailing about condom use for young men also included a coupon to order free condoms by mail. After the mailing, 7% of the intervention group reported ordering condoms by mail, versus 1% of the control group (p<0.01).15

Knowledge and Awareness

Six studies8,10–12,14,15 assessed community education's effects on knowledge and awareness of contraception. Four of these studies8,10–12 combined mass media with other forms of print media and demonstrated increased awareness of EC. For example, in one study,8 campaign materials and messages targeted women living in a Boston neighborhood; the cross-sectional survey completed after the intervention found significant increases in the percentage of women who had heard of EC (82%–91%, p<0.01); were knowledgeable about EC (39%–49%, p<0.01); and had discussed EC with a provider (25%–38%, p<0.01). In the two studies7,22 assessing the impact of text only and text and e-mail messages, knowledge of sexual health increased in both samples, for both men and women. For example, in the RCT by Lim et al.,7 the AOR for high knowledge was 2.36 (95% CI=1.27, 4.37) for the intervention group, compared with the control group, at 12 months. Finally, Hillman and colleagues23 described a study that was designed to assess the effects of viewing a theatrical performance addressing sexual and contraceptive issues on various short-term outcomes. This study described a comparison of pre- and post-performance surveys of 143 teen participants who viewed the theatre production. The authors reported that in surveys, teens demonstrated greater sexual health knowledge after the performance as compared with before (p<0.01).

Two additional studies14,15 that focused primarily on small print media added limited or no additional support for improvements in knowledge/awareness in the context of condom promotion. First, in the study15 of the direct mailing about condoms to young men, knowledge scores were slightly higher among the men who received the mailing, compared with those who did not (83% vs 80%, p<0.01), though 64% of those in the intervention group who read the pamphlet reported learning something from it. Bull et al.14 used a neighborhood-level randomized trial to test a campaign involving local print media (e.g., posters) and vouchers for free condoms and reported no evidence of improvement in knowledge following the campaign.

Intentions to Use Contraception

Seven studies8–11,13,15,16 described community education's effects on intentions to use contraception. Three8–10 of four studies reported that intentions to use EC were increased following efforts that used mass media as a primary outreach channel to increase women's awareness and knowledge of this form of contraception. The fourth study,11 of an EC campaign in Sweden, also reported increases in intentions to use EC among women in the community that received the multi-pronged community education campaign, but the increases were not significantly greater than those reported in a comparison community. Another study16 promoting condom use among young men observed significant increases in at-risk young adult's intentions to use condoms following a televised media campaign. However, the authors observed that the changes in intentions to use condoms returned to pre-campaign exposure levels after 2 months following the end of the televised PSAs.

Three other studies promoting safer sexual behavior demonstrated no, or limited, results on intentions to use condoms. Alstead and colleagues13 used local radio and posters/billboards to promote condom use in adolescents aged 15–17 years. Their results did not demonstrate increased intentions to use condoms following the campaign; however, the authors noted that self-reported condom use was high to begin with. Kirby et al.15 also reported limited impact of the direct-mail approach on young men's intentions to use condoms. When asked if they would be more likely to use condoms if they could get them by mail, 54% of all sexually active men said they would. Finally, in the study23 of the teen theater intervention, the authors reported that following the performance, teens demonstrated greater intention to use birth control (t[43] = 3.02, p<0.01). However, there were no changes in self-reported intention to protect oneself from STDs using condoms, or intentions to delay intercourse.

Other Psychosocial Mediators Related to Family Planning Use

Four studies15,16,21,23 addressed the relationship between community education efforts and other psychosocial determinants such as intentions to use or attitudes about family planning. Two studies found that predominantly mass media campaigns were effective in changing perceptions of the risks associated with pregnancy among middle school youth,21 and condom use self-efficacy or one's ability to use condoms in appropriate situations in young adults (aged 18–26 years).16 Kirby and colleagues15 found that direct-mail intervention had a modest impact on attitudes toward condom use. Specifically, those individuals who read the mail-distributed pamphlet on condom use were no more likely to believe that they could get an STD than the controls. However, the same individuals were slightly more likely to believe that they might get someone pregnant, and that there was a benefit from using a condom (p<0.05 and p<0.01, respectively). In the teen theater study,23 the authors reported that following the performance, teens demonstrated greater willingness to discuss sexual topics (t[80] = 10.01, p<0.001). There were no changes, however, in self-reported comfort level in discussing sexual issues.

Parent–Child Communication

Three studies17,18,21 examined interventions that aimed, at least in part, to increase communication between parents and their children about sex. The two that focused primarily on this outcome, and interviewed parents to assess effects, demonstrated that multiple channels of mass media outreach can successfully increase parents' talking to, or intentions to talk to, their children about sex. One was an RCT18 conducted among parents of children aged 10–14 years who were already a part of an online research cohort and involved viewing or listening to some PSAs promoting that they speak to their children about waiting to have sex. At 6 months following the PSAs, both mothers and fathers in the intervention group increased their recommendations to children to wait before becoming sexually active, and fathers (but not mothers) demonstrated an increase in the initiation of such conversations. The other study by DuRant and colleagues17 demonstrated similar success in a more natural, real-life setting. That intervention involved a mainly mass media campaign promoting parent–child communication about sex among parents of adolescents in various counties in North Carolina. In that study, for example, the frequency of exposure to radio and TV PSAs was positively associated with parents having talked with their adolescent children about sexual issues in the past 6 months.

Finally, in a study of a multifaceted, countywide abstinence campaign in New York state, the authors assessed the effectiveness of a media campaign in improving middle school–aged adolescents' communication with their parents about sex, as one of its secondary outcomes.21 This study did not find evidence of improved communication between youth and their parents, though it identified other positive outcomes (not described here).

Barriers and Facilitators of Community Education for Clients and Clinics/Implementers

None of the identified studies reported on unintended or negative consequences of family planning–related community education.

Two studies reported on facilitators for clients in being reached by community education efforts. First, Alstead and colleagues13 noted that use of a participatory approach to develop the condom promotion campaign was engaging of community members, facilitated the development and implementation of the project, and fostered a sense of goodwill toward the project. Second, in the text messaging study by Gold et al.,22 the authors noted that there was a preference for messages that were positive, relevant, short, and covered a variety of topics. Participants were more likely to remember and share messages that were funny, rhymed, or tied into particular annual events. If messages were deemed to be boring, too long, repetitive, used inappropriate language, or provided nothing new, they were ignored.

Eleven of the included studies reported on barriers or facilitators for clinics or implementers of family planning–related community education. Facilitators included, for example, having a nurse serve as the community outreach educator, which made clinical expertise more widely available and immediate, and having relationships with a wide variety of local organizations that serve young people.19 Other studies highlighted the importance of community advisory groups or other partners to help guide the intervention and even share the costs,9,12,14,21 as well as discounted or pro bono assistance for marketing from advertising agencies and media outlets.13,14,21 Three8,15,22 highlighted the relatively low cost of their interventions as advantages. A few studies noted that they faced restrictions on their interventions, for either political or legal reasons. For example, in one,9 they were unable to explicitly mention EC in their radio spots, and in others,12,13 some promotional material that might have been more influential was deemed too sensitive by many community groups to use.

Discussion

Twelve of 15 studies included in this review examined short-term outcomes and found some positive associations between community education and the assessed outcomes, with six of those also finding at least one null finding. As shown in Table 2, most of the included studies focused on campaign-style interventions and found positive associations across the assessed outcomes. The three targeted print media– or mail-based interventions collectively found mixed results, with two studies finding positive associations and two finding null findings. Two studies involved both clinic-based changes and community outreach workers, and both were associated with increases in the use of services. Two interventions using text messaging or e-mail found positive results, as well as one null effect. Finally, the one pre–post evaluation of a teen theater show found positive associations. As discussed above, these interventions varied widely, as did the strength of their respective evaluation study designs. A few studies indicated that the interventions could increase use of family planning–related resources that were promoted (e.g., contraceptive hotline), and others were associated with increased use of services, though some of those studies relied on self-reported measures of service use or had other intervention components that promoted service uptake (e.g., service consolidation). Overall, the evidence suggests that community education can be effective for improving some short- and medium-term outcomes, particularly those related to awareness and knowledge, and increasing use of resources or services.

A targeted search was run in PubMed for the period from March 1, 2011, through December 31, 2014, to search for newly published research in the area. Two additional studies24,25 have been published since this systematic review was completed. Both involved “new media” approaches and reported on short-term psychosocial outcomes. In one,24 researchers applied a unique RCT design to test an intervention that involved promotion of an interactive website about sexual health, with a focus on condom use, for 8 weeks through Facebook to engage the social networks of African American and Hispanic youth in two areas of the U.S. They found that both their study design and intervention approach were feasible and identified short-term positive effects of website use on self-reported condom use, but no effects for any of the psychosocial mediators they assessed. The other study25 was a process evaluation of instant messaging and text message services made available through Planned Parenthood that provided tailored, immediate responses on sexual and reproductive health queries (e.g., abortion, STD exposure). They assessed one psychosocial outcome, namely, changes in reported worry among callers about the issues they were reaching out about. They found that these services reached the intended audience (i.e., large portions of black and Latino/Hispanic youth) and, from multiple variable analysis, that callers' degree of worry decreased after the instant message or text communication for certain subgroups (e.g., users aged <17 years) and users asking about certain topics (e.g., EC).

A recent review of studies of family planning campaigns and interventions in developing country settings found that most studies identified were focused on short-term outcomes and reported positive effects. Results were fewer for medium-term outcomes such as contraceptive use but were generally positive, particularly for programs that combined mass media with other intervention components.26 That review also examined interventions that were primarily interpersonal (e.g., peer-led or community-based outreach to individuals or small groups). Those studies were of medium quality, and also identified largely positive effects on short-term outcomes, with more mixed results for medium- and long-term outcomes (e.g., unintended pregnancy).

Reviews of international research on HIV/AIDS-related campaigns also point in similar directions. In a recent update of a systematic review of mass media campaigns for HIV prevention internationally (including the U.S.), the authors found that among the studies with the strongest study designs, eight of ten found positive effects on various behaviors and behavioral intentions (i.e., medium- and short-term outcomes).27,28 The authors also commended the field for better use of the key principles of social marketing in their programs but lamented the generally weak evaluation study designs that were still being used. A separate meta-analysis29 of structural interventions for HIV prevention in the U.S. and internationally included social marketing and related campaigns within its scope and found positive effects on behavior change and HIV incidence (i.e., medium- and long-term outcomes). Effect sizes were stronger when such campaigns were combined with other intervention components such as condom distribution and when they were conducted in settings outside the U.S. Two Cochrane reviews,30,31 one related to mass media interventions for promoting HIV testing and another related to mass media for promoting utilization of health services, also found limited support for increases in desired outcomes such as service utilization and behavior change.

Limitations

This review is subject to important caveats. First, it is likely that publication bias against studies that showed no effects of community education skewed the results toward positive findings. However, the degree of bias is unknown. In addition, the studies that were identified ranged widely in study designs, strength of evidence, and degree of bias. Only one15 was evaluated as having a low risk for bias. The interventions ranged in method and intensity, from a series of text messages to a single teen theater event to relatively expensive, large-scale multimedia campaigns extending over months. Given variation in how the studies were described, it also was difficult to describe or assess the interventions in terms of their adherence to best practices in social marketing and community education, such as use of formative research and tailoring messages. The populations served varied too, including many interventions focused on adolescents and young adults, in addition to campaigns for adult women from the general population and parents. Five were based outside the U.S. Overall, this diversity of interventions, study populations, and study designs cautions against generalizing extensively across results.

This review identified few studies in some areas of community education that may be more prevalent in the U.S. family planning field today. For example, it will be important to track and conduct research on the value of using the Internet and social media strategies for promoting service utilization and related outcomes. Interpersonal outreach to special or underserved populations also was under-represented in this review, despite being an important activity for some family planning providers.32 Overall, additional evidence from well-designed studies on the effects of various approaches to community education is needed to inform programs and help with decision making about whether and how to best apply these approaches. Effective community education is one of the tools in the scope of activities of family planning programs that potentially may help improve understanding of the value of family planning, and use of family planning services, at the community level.

Conclusions

The results of this review were presented to a Technical Panel convened in May 2011 and to Title X Expert Work Group meetings in September 2011 and June 2012, all convened as part of the development of “Providing Quality Family Planning Services: Recommendations of CDC and the U.S. Office of Population Affairs.”33 At the final meeting, three of five experts agreed with the recommendation that family planning programs should conduct community education and service promotion when there is a need to make communities more aware and knowledgeable about those programs. The rationale for supporting this recommendation was that the benefits of increased use of services and reduced sexual risk behaviors outweighed the potential costs of conducting community education of this kind. Informing underserved communities about the availability of family planning services was viewed as a core aspect of improving access to services, and consistent with the Title X program's core mission. The evidence suggested that targeted outreach efforts can result in increased uptake of services among those not previously aware of services. However, experts also acknowledged that substantial resources are usually needed to conduct highly effective community education and service promotion. For this reason, one member felt that community education and service promotion, although potentially valuable and ideal, should not be recommended as a core component of quality family planning programs, given that many publicly funded family planning centers face considerable resource constraints. Instead, limited resources should be devoted toward maintaining and further improving the quality of services offered to existing clients. Nevertheless, all five members agreed with the recommendation that family planning programs should use evidence-based and evidence-informed approaches when conducting any type of outreach, in order to optimize the resources involved and potential outcomes. This would involve, for example, careful planning and drawing from the core principles of social marketing such as use of formative research, audience segmentation, tailored messages, and behavior change theory to guide that work.28,34 “Providing Quality Family Planning Services: Recommendations of CDC and the U.S. Office of Population Affairs” ultimately focused on clinical services and did not include any recommendations related to community education and service promotion.33 However, these recommendations were submitted to the Title X program for integration into their operations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Publication of this article was supported by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Office of Population Affairs (OPA).

The findings and conclusions of this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of CDC or the Office of Population Affairs.

Footnotes

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Appendix Supplementary data Supplementary data associated with this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2015.03.030.

References

- 1.Public Health Service: Grants for Family Planning Services. 10-1-00 ed DHHS; 2000. 42 CFR Part 59 Subpart A. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tregear SJ, Gavin LE, Williams JR. Systematic review evidence methodology: providing quality family planning services. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(2S1):S23–S30. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.03.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harris RP, Helfand M, Woolf SH, et al. Current methods of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force: a review of the process. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20(3 suppl):21–35. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00261-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(01)00261-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chin HB, Sipe TA, Elder R, et al. The effectiveness of group-based comprehensive risk-reduction and abstinence education interventions to prevent or reduce the risk of adolescent pregnancy, human immunodeficiency virus, and sexually transmitted infections: two systematic reviews for the Guide to Community Preventive Services. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(3):272–294. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.11.006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2011.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kirby D. Emerging Answers 2007: Research Findings on Programs to Reduce Teen Pregnancy and Sexually-Transmitted Diseases. National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy; Washington, DC: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carter MW, Tregear ML, Lachance CR. Community engagement in family planning in the U.S.: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(2S1):S116–S123. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lim MS, Hocking JS, Aitken CK, et al. Impact of text and email messaging on the sexual health of young people: a randomised controlled trial. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012;66(1):69–74. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.100396. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/jech.2009.100396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gee RE, Delli-Bovi LC, Chuang CH. Emergency contraception knowledge after a community education campaign. Contraception. 2007;76(5):366–371. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2007.07.007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hall C, Milner P. Advertising emergency contraception using local radio: an evaluation. Health Educ J. 1996;55(2):165–174. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/001789699605500204. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Larsson M, Aneblom G, Eurenius K, Westerling R, Tyden T. Limited impact of an intervention regarding emergency contraceptive pills in Sweden—repeated surveys among abortion applicants. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2006;11(4):270–276. doi: 10.1080/13625180600766347. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13625180600766347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Larsson M, Eurenius K, Westerling R, Tyden T. Emergency contraceptive pills in Sweden: evaluation of an information campaign. BJOG. 2004;111(8):820–827. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00206.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trussell J, Koenig J, Vaughan B, Stewart F. Evaluation of a media campaign to increase knowledge about emergency contraception. Contraception. 2001;63(2):81–87. doi: 10.1016/s0010-7824(01)00174-3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0010-7824(01)00174-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alstead M, Campsmith M, Halley CS, Hartfield K, Goldbaum G, Wood RW. Developing, implementing, and evaluating a condom promotion program targeting sexually active adolescents. AIDS Educ Prev. 1999;11(6):497–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bull SS, Posner SF, Ortiz C, Beaty B, Benton K. POWER for reproductive health: Results from a social marketing campaign promoting female and male condoms. J Adolesc Health. 2008;43(1):71–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.12.009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kirby D, Harvey PD, Claussenius D, Novar M. A direct mailing to teenage males about condom use: its impact on knowledge, attitudes and sexual behavior. Fam Plann Perspect. 1989;21(1):12–18. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2135413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zimmerman RS, Palmgreen PM, Noar SM, Lustria ML, Lu HY, Lee Horosewski M. Effects of a televised two-city safer sex mass media campaign targeting high-sensation-seeking and impulsive-decision-making young adults. Health Educ Behav. 2007;34(5):810–826. doi: 10.1177/1090198107299700. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1090198107299700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DuRant RH, Wolfson M, LaFrance B, Balkrishnan R, Altman D. An evaluation of a mass media campaign to encourage parents of adolescents to talk to their children about sex. J Adolesc Health. 2006;38(3):298.e1–298.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.11.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Evans WD, Davis KC, Ashley OS, Blitstein J, Koo H, Zhang Y. Efficacy of abstinence promotion media messages: findings from an online randomized trial. J Adolesc Health. 2009;45(4):409–416. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.02.014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baraitser P, Fettiplace R, Dolan F, Massil H, Cowley S. Quality, mainstream services with proactive and targeted outreach: a model of contraceptive service provision for young people. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2002;28(2):90–94. doi: 10.1783/147118902101196018. http://dx.doi.org/10.1783/147118902101196018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brindis CD, Geierstanger SP, Wilcox N, McCarter V, Hubbard A. Evaluation of a peer provider reproductive health service model for adolescents. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2005;37(2):85–91. doi: 10.1363/psrh.37.085.05. http://dx.doi.org/10.1363/3708505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Doniger AS, Adams E, Utter CA, Riley JS. Impact evaluation of the “not me, not now” abstinence-oriented, adolescent pregnancy prevention communications program, Monroe County, New York. J Health Commun. 2001;6(1):45–60. doi: 10.1080/10810730150501404. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10810730150501404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gold J, Lim MS, Hocking JS, Keogh LA, Spelman T, Hellard ME. Determining the impact of text messaging for sexual health promotion to young people. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;39(4):247–252. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181f68d7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hillman E, Hovell MF, Williams L, et al. Pregnancy, STDs, and AIDS prevention: evaluation of New Image Teen Theatre. AIDS Educ Prev. 1991;3(4):328–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bull SS, Levine DK, Black SR, Schmiege SJ, Santelli J. Social media-delivered sexual health intervention: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(5):467–474. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.07.022. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2012.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giorgio MM, Kantor LM, Levine DS, Arons W. Using chat and text technologies to answer sexual and reproductive health questions: Planned Parenthood pilot study. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(9):e203. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2619. http://dx.doi.org/10.2196/jmir.2619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mwaikambo L, Speizer IS, Schurmann A, Morgan G, Fikree F. What works in family planning interventions: a systematic review. Stud Fam Plann. 2011;42(2):67–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2011.00267.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4465.2011.00267.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bertrand JT, O'Reilly K, Denison J, Anhang R, Sweat M. Systematic review of the effectiveness of mass communication programs to change HIV/AIDS-related behaviors in developing countries. Health Educ Res. 2006;21(4):567–597. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl036. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/her/cyl036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Noar SM, Palmgreen P, Chabot M, Dobransky N, Zimmerman RS. A 10-year systematic review of HIV/AIDS mass communication campaigns: have we made progress? J Health Commun. 2009;14(1):15–42. doi: 10.1080/10810730802592239. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10810730802592239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Charania MR, Crepaz N, Guenther-Gray C, et al. Efficacy of structural-level condom distribution interventions: a meta-analysis of U.S. and international studies, 1998–2007. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(7):1283–1297. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9812-y. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10461-010-9812-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grilli R, Ramsay C, Minozzi S. Mass media interventions: effects on health services utilisation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(1):CD000389. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000389. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD000389. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Vidanapathirana J, Abramson MJ, Forbes A, Fairley C. Mass media interventions for promoting HIV testing. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;3:CD004775. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004775.pub2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004775.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Donovan P. Taking family planning services to hard-to-reach populations. Fam Plan Perspect. 1996;28(3):120–126. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2136225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gavin L, Moskosky S, Carter M, et al. Providing quality family planning services: recommendations of CDC and the U.S. Office of Population Affairs. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2014;63(RR-04):1–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grier S, Bryant CA. Social marketing in public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26:319–339. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144610. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.