Abstract

Previous research on stroke and traumatic brain injury (TBI) heavily emphasized pathological alterations in neuronal cells within gray matter. However, recent studies have highlighted the equal importance of white matter integrity in long-term recovery from these conditions. Demyelination is a major component of white matter injury and is characterized by loss of the myelin sheath and oligodendrocyte cell death. Demyelination contributes significantly to long-term sensorimotor and cognitive deficits because the adult brain only has limited capacity for oligodendrocyte regeneration and axonal remyelination. In the current review, we will provide an overview of the major causes of demyelination and oligodendrocyte cell death following acute brain injuries, and discuss the crosstalk between myelin, axons, microglia, and astrocytes during the process of demyelination. Recent discoveries of molecules that regulate the processes of remyelination may provide novel therapeutic targets to restore white matter integrity and improve long-term neurological recovery in stroke or TBI patients.

Keywords: demyelination, oligodendrocyte, remyelination, cerebral ischemia, traumatic brain injury

1. Introduction

Stroke and traumatic brain injury (TBI) are worldwide public health and socioeconomic problems (Gillum et al., 2011; Roozenbeek et al., 2013). With recent improvements in emergency care, greater numbers of patients are able to survive after stroke or TBI than before. Unfortunately, most of these survivors still develop physical disabilities due to the lack of effective therapies to restrict and/or repair brain damage. Understanding the mechanisms underlying progressive brain damage after stroke or TBI is therefore imperative for the development of novel therapies that successfully improve long-term neurological functions.

The human brain consists of both gray matter and white matter. Gray matter mainly contains neuronal cell bodies and unmyelinated axons. Gray matter serves as an information processor for the central nervous system (CNS). White matter, on the other hand, is mainly composed of bundles of myelin-ensheathed axons, myelin-producing oligodendrocytes, and other glial cells. White matter plays an essential role in signal transmission and communication between different brain regions. Although previous research on brain injuries emphasized the pathological alterations in neuronal cells within gray matter, recent studies also highlight the importance of white matter integrity in long-term recovery after stroke and TBI (Matute et al., 2013; Pham et al., 2012; Semple et al., 2013) White matter injury is an integral component of most human stroke or TBI events and usually accounts for at least half of the lesion volume (Ho et al., 2005; Hulkower et al., 2013). Unfortunately, the adult brain has very limited capacity for white matter repair. Thus, unrepaired white matter injury disrupts sensorimotor function and elicits profound neurobehavioral and cognitive impairments (Desmond, 2002)

Demyelination, or loss of the myelin sheath, is a major pathological component of white matter injury and contributes significantly to long-term sensorimotor and cognitive deficits (Pantoni et al., 1996). Oligodendrocytes are the primary cells responsible for generating and maintaining the myelin sheath under normal conditions and for remyelination after axonal damage (Nave, 2010a). However, myelinating oligodendrocytes are highly vulnerable to ischemic or traumatic insults (Back et al., 2007; Petito et al., 1998) and the loss of oligodendrocytes is known to be a significant factor underlying demyelination after injury (Caprariello et al., 2012).

Herein, we will describe the major causes of demyelination and oligodendrocyte death following acute injury in the adult brain, and discuss the crosstalk between myelin, axons, microglia, and astrocytes. We will also describe the toxic sequelae of demyelination, and highlight potential therapeutic strategies to target demyelination and improve long-term neurological function recovery in stroke or TBI patients.

2. Molecular mechanisms underlying oligodendrocyte death and demyelination

Oligodendrocytes are highly sensitive to various stimuli, including oxidative stress (Husain and Juurlink, 1995), excitotoxicity (McDonald et al., 1998; Salter and Fern, 2005), and inflammation, all of which induce oligodendrocyte cell death and contribute to demyelination after stroke or TBI. Below we discuss the molecular mechanisms underlying oligodendrocyte cell death and demyelination.

2.1 Glutamate excitotoxicity

Glutamate toxicity is a major cause of cell death in oligodendrocytes and their progenitor cells in diverse CNS injuries (McDonald et al., 1998; Salter and Fern, 2005). Under conditions of energy breakdown, reversal of excitatory amino acid transporters (EAATs) may lead to unchecked extracellular glutamate release, which induces glutamate excitotoxicity through glutamate receptors on the surface of oligodendrocytes (Fern et al., 2014). Intracellular calcium overload from glutamate excitotoxicity is a significant cause of oligodendrocyte and myelin damage (Benarroch, 2009). Glutamate receptor overstimulation opens Na+/Ca2+ channels on oligodendrocytes, not only allowing the influx of calcium but also depolarizing the cell membrane (Tong et al., 2009). This membrane depolarization activates voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels, which could further increase intracellular Ca2+ levels. In addition, the decreased Na+ gradient across the cell membrane caused by the glutamate surge may reduce the capacity of the Na+ gradient–dependent antiporter to remove intracellular Ca2+. In addition, Ca2+ can be released from its intracellular storage sites upon glutamate stimulation in oligodendrocytes. It has been reported that Ca2+ release from the endoplasmic reticulum through ryanodine receptors (RyRs) and from mitochondria through inositol triphosphate receptors (IP(3)Rs) is important for α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptor-mediated excitotoxicity in oligodendrocytes (Ruiz et al., 2010). All of these mechanisms might contribute to the accumulation of cytosolic Ca2+, which in turn can trigger oligodendrocyte toxicity (Benarroch, 2009).

There are three types of glutamate receptors on oligodendrocytes: AMPA, kainate, and N-methyl D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors (Butt, 2006; Salter and Fern, 2005). Glutamate receptors might be directly activated by glutamate released from damaged axons (Kukley et al., 2007; Ziskin et al., 2007). It has been shown that extracellular glutamate levels surge several hours after CNS injuries (Kolodziejczyk et al., 2010; Lai et al., 2014; Matute et al., 2006), leading to the over-activation of AMPA/kainate and NMDA receptors in the brain.

Previous studies have demonstrated that oligodendrocytes are highly vulnerable to AMPA/kainate receptor-mediated excitotoxicity (Alberdi et al., 2002). Blockade of this receptor reduces oligodendrocyte death in vivo (Tekkok and Goldberg, 2001) and in vitro (McDonald et al., 1998). Recent work further suggests that Zn2+ dysregulation is important in AMPA-induced excitotoxicity (Mato et al., 2013). The activation of AMPA receptors results in the cytosolic accumulation of Ca2+, which in turn induces Zn2+ mobilization and accumulation in the cytosol (Mato et al., 2013). Excessive Zn2+ is known to activate ERK1/2 signal transduction cascades and induce oligodendrocyte death in a poly[ADP]-ribose polymerase 1 (PARP-1)-dependent manner (Baxter et al., 2014; Domercq et al., 2013). NMDA receptors are expressed on the myelin sheath of oligodendrocyte processes and are similarly involved in oligodendrocyte cell death (Karadottir et al., 2005; Micu et al., 2006; Salter and Fern, 2005). Activation of these receptors leads to a drastic increase in ion concentrations (Benarroch, 2009; Butt, 2006; Salter and Fern, 2005; Song and Yu, 2014) and the disruption of myelin structure (Bakiri et al., 2008). Thus, excess glutamate released from damaged axons after CNS injuries may elicit calcium-induced excitotoxicity and zinc dysregulation in oligodendrocytes through AMPA and NMDA receptors.

2.2 Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress

Mitochondria are double membrane-bound organelles responsible for more than 80% of total ATP production within the cell. ATP production in mitochondria is achieved through the oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) complexes embedded in the inner mitochondrial membrane. NADH and FADH2 are produced through the tricarboxylic acid cycle in the matrix and are further oxidized by complexes I and II, respectively. The resulting electrons are passed through a series of electron carriers to the final electron acceptor, molecular oxygen. Furthermore, H+ ions are pumped into the intermembrane space to generate an electrochemical gradient across the inner membrane, thereby driving ATP synthesis (Newmeyer and Ferguson-Miller, 2003). In addition to serving as the power generator of the cell, mitochondria are intimately involved in apoptosis. Indeed, both anti-apoptotic and pro-apoptotic factors such as the Bcl-2 family members and caspases are closely associated with mitochondria (Chandra et al., 2004; Czabotar et al., 2014).

Mitochondrial dysfunction is implicated in the pathogenesis of various demyelinating disorders (Mahad et al., 2008; van Horssen et al., 2012). Damaged mitochondria have been shown accumulate in demyelinated axons and activated astrocytes after CNS insults. Under physiological conditions, the normal OXPHOS reaction produces reactive oxygen species (ROS) including superoxide (O2−), hydroxyl radicals (OH), and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) through complexes I and III. This ROS production is critical for redox signaling and integrating mitochondrial function with that of the whole cell (Murphy, 2009). The mitochondria-derived ROS can diffuse throughout the cell, thereby being reduced in concentration, and is usually removed by cytosolic antioxidant systems such as catalase, glutathione peroxidase, and thioredoxin peroxidase under normal, physiological conditions (Kong et al., 2014). However, excess ROS can be generated under stressful conditions, such as cyanide or rotenone poisoning, or during conditions of oxygen glucose deprivation (OGD), in which a lack of electron acceptors is especially harmful. Owing to their high energy demands, the abundance of iron, and low levels of molecular antioxidants, oligodendrocytes are highly sensitive to increased ROS (Juurlink, 1997; Shereen et al., 2011). Recent studies suggest that ischemia induces ROS production in vivo and in vitro, which leads to myelin loss and disruption of oligodendrocyte precursor cell (OPC) differentiation (Miyamoto et al., 2013). Furthermore, mitochondrial dysfunction may result in impaired Ca2+ regulation and axonal degeneration (Carvalho, 2013; Owens et al., 2013). When energy demands exceed the ATP-producing capacity of mitochondria, axons in injured regions become energy deficient, leading to intracellular Ca2+ influx and Ca2+ release from mitochondria (Kostic et al., 2013; Trapp and Stys, 2009). In addition, ATP signaling can directly trigger oligodendrocyte excitotoxicity by activation of Ca2+-permeable purinergic P2X7 receptors (Matute, 2011). Mitochondrial injury has also been demonstrated to be involved in microglial release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (Lisak et al., 2009), many of which can induce oligodendrocyte damage, as described in the next section (section 2.3). Thus, oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction are both critical players in the pathophysiology of demyelination.

2.3 Pro-inflammatory cytokines

Inflammatory cytokines are key mediators of pathological changes in demyelination disorders (Table 1). Cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-2, and interferon-γ (IFN-γ), have all been repeatedly demonstrated to induce oligodendrocyte death (An et al., 2014; Curatolo et al., 1997; Li et al., 2008). For example, TNF-α has robust effects on oligodendrocyte cell lines. TNF-α inhibits OPC proliferation and differentiation, and induces oligodendrocyte apoptosis (Hovelmeyer et al., 2005; Pang et al., 2005). IFN-γ also produces concentration-dependent effects on oligodendrocyte cell lines. High levels of IFN-γ lead to oligodendrocyte apoptosis and demyelination, whereas low levels protect mature oligodendrocytes by maintaining OPCs in the cell cycle and mildly stressing the endoplasmic reticulum (Chew et al., 2005; Corbin et al., 1996; Lin et al., 2005). Furthermore, IL-6 enhances OPC differentiation and survival even in the presence of glutamate excitotoxicity (Pizzi et al., 2004; Valerio et al., 2002). Recent studies demonstrate that IL-17A exposure stimulates OPCs to differentiate and mature and participate in the inflammatory response (Rodgers et al., 2014). An improved understanding of inflammatory mechanisms underlying oligodendrocyte death and demyelination might lead to novel neuroprotective therapeutic approaches for stroke or TBI patients.

Table 1.

Effect of pro-inflammatory cytokines on oligodendrocyte line cells

| Cytokine | Regulation | Function | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| TNF-α | TNFR1/JNK signaling, TIMP-3/caspase-3 | induce oligodendrocyte apoptosis; delay myelination | (Deng et al., 2008; Deng et al., 2010; Hovelmeyer et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2011; Pang et al., 2005; Su et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2011) |

| TNFR2/leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), AMPK, oxidative stress | inhibit OPC proliferation and differentiation | (Bonora et al., 2014; Fischer et al., 2014; Kleinsimlinghaus et al., 2013; Maier et al., 2013) | |

| IL-1β | ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF) | induces the survival of oligodendrocytes | (Herx et al., 2000) |

| glutamate excitotoxicity | promotes oligodendrocyte and OPC death | (Takahashi et al., 2003) | |

| MAPK signaling pathways | inhibit OPC proliferation, enhancing differentiation and survival | (Vela et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2006) | |

| IL-6 | IL-6R | enhances OPC differentiation and survival | (Lara-Ramirez et al., 2008; Pizzi et al., 2004; Valerio et al., 2002) |

| IL-11 | IL-11R | potentiates oligodendrocyte survival, maturation | (Zhang et al., 2006) |

| IL-17A | ERK1/2 signaling | promotes OPC differentiation | (Rodgers et al., 2014) |

| Interferon-γ | dendritic cell exosomes | maintain OPCs in the cell cycle, stress the endoplasmic reticulum, involved in remyelination | (Chew et al., 2005; Pusic et al., 2014) |

| endoplasmic reticulum kinase | induces oligodendrocyte apoptosis | (Chew et al., 2005; Corbin et al., 1996; Lin et al., 2005) |

3. Crosstalk between oligodendrocytes and other white matter components

White matter consists of axons, myelin, oligodendrocytes, astrocytes, microglia, and capillaries. Accumulating evidence indicates that metabolite exchanges (cholesterol, glycogen, lactate, and N-acetyl-aspartate) between these components are important for the normal function of white matter tracts (Amaral et al., 2013; Saab et al., 2013). Understanding the interdependence of white matter components might help explain how pathological alterations expand through the nervous system across gray and white matter boundaries.

3.1 Axonal injury

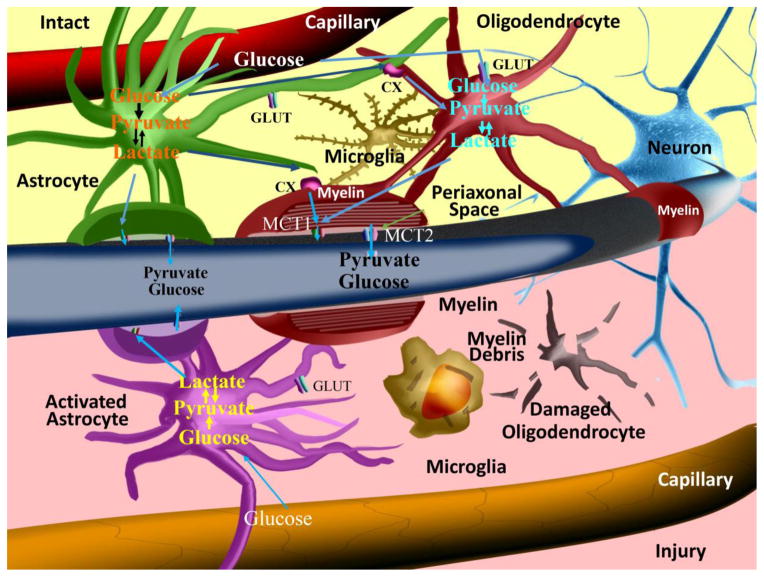

In white matter tracts, axons are encapsulated by oligodendrocyte-generated myelin. The proliferation, migration, survival, and differentiation of oligodendrocytes require axon-derived signals (Bremer et al., 2010; Nave and Trapp, 2008). However, oligodendrocytes are also actively involved in sensing axonal energy needs and maintaining axonal integrity (Lappe-Siefke et al., 2003; Nave, 2010a). Once an axon has been demyelinated, its ability to transmit action potentials and its energy supply are severely impaired, and the exposed nerve fiber is highly susceptible to degeneration. Oligodendrocytes may support axonal survival and function through mechanisms independent of myelination (Funfschilling et al., 2012; Morrison et al., 2013). For example, oligodendrocytes and their myelin processes deliver pyruvate or lactate to neurons, which is essential for normal axon integrity and function in vivo (Morrison et al., 2013; Nave, 2010b). Monocarboxylic acid transporters (MCTs), the most abundant lactate transporter in the CNS, are highly expressed on oligodendrocytes (Figure 1). The disruption of this transporter leads to blockade of the lactate shuttle from oligodendrocytes to axons and elicits axonal damage and neuron loss (Lee et al., 2012).

Figure 1. Astrocyte, oligodendrocyte, and axon interactions in white matter in normal or pathological settings.

Under normal conditions, astrocytes take up glucose from capillaries through glucose transporters (GLUTs) and the subsequent glycolysis metabolites can be transmitted to axons and oligodendrocytes as energy sources by monocarboxylic acid transporters (MCTs) and connexins (CXs). However, when astrocytes are activated under stressful conditions, the normal CX-mediated communication between astrocytes and oligodendrocytes is interrupted, resulting in oligodendrocyte cell death and subsequent demyelination.

It is tempting to speculate that, during pathological conditions, energy may be gained by the breakdown of myelin lipids in oligodendrocyte peroxisomes (Kassmann, 2014). However, disruption of oligodendrocyte proteins such as proteolipid protein (PLP) (Al-Saktawi et al., 2003; Edgar et al., 2010) and 2′,3′-cyclicnucleotide3′-phosphodiesterase (CNP) (Lappe-Siefke et al., 2003) may contribute to severe disruption of axonal function and integrity. In short, oligodendrocyte damage invariably produces some degree of axonal demyelination and degeneration, and contributes to permanent neurological disabilities after stroke or TBI.

3.2 Astrocyte activation

In addition to direct energy support from oligodendrocytes to neurons, astrocytes may also be involved in supplying energy to axons. Astrocytes contact capillaries with their end feet and take up many metabolites from blood (Daneman, 2012) (Figure 1). Under physiological conditions, astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and axons take up glucose from capillaries through glucose transporters (GLUTs). Damage to the axon or oligodendrocyte results in an increase in glutamate in the extracellular space, due to the reversal of glutamate transporters (Domercq et al., 2005) or the vesicular release of glutamate from unmyelinated axons (Ziskin et al., 2007). The excessive glutamate in white matter can, at least partly, be taken up by astrocytes. Glycolysis is known to occur within astrocytes, leading to the production of metabolites such as lactate. Lactate is then taken up as an energy substrate by axons and oligodendrocytes through MCTs and connexins (CXs) (Figure 1). This ‘pan-glial’ network of oligodendrocytes and astrocytes is the major regulator of glutamate homeostasis in the CNS (Matute et al., 2007) and also serves as a spatial potassium buffer, allowing water transport for the maintenance of ionic homeostasis (Menichella et al., 2006; Rash, 2010).

Oligodendrocyte death and axonal demyelination are invariably accompanied by the activation of astrocytes. Oligodendrocytes are interconnected not only with each other but also with astrocytes via gap junctions, allowing for intercellular transfer of small molecules (Orthmann-Murphy et al., 2007; Tress et al., 2012). Disruption of the coupling between astrocytes and oligodendrocytes has been shown to result in demyelination and motor impairments in vivo (Tress et al., 2012). When astrocytes are activated under stressful conditions, the use of astrocyte-released energy substrates may transiently support axon energy needs and partially compensate for loss of function. However, normal communication between astrocytes and oligodendrocytes through CXs is interrupted in pathological conditions, thereby resulting in oligodendrocyte death and subsequent demyelination. Activated astrocytes can also exacerbate oligodendrocyte cell death by reducing extracellular zinc concentrations, which then initiates NADPH oxidase activation within oligodendrocytes through stimulation of Ca2+-permeable AMPA receptors (Johnstone et al., 2013). These results show that activated astrocytes exert both positive and negative influences on oligodendrocyte pathophysiology, similar to the dual-faced nature of microglia discussed below.

3.3 Microglial activation

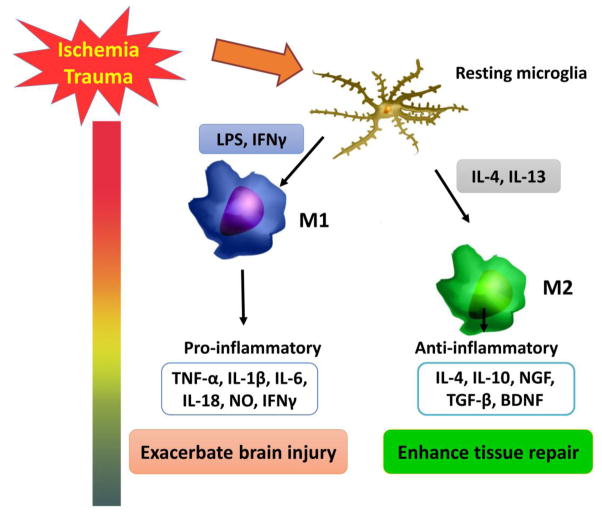

Microglia are resident immune cells within the CNS and play a central role in the initiation and propagation of inflammatory responses (Hu et al., 2014; Owens et al., 2013). They are present within all brain regions, including regions containing both gray and white matter. Microglia are rapidly activated and increase in numbers in response to CNS injuries. Activated microglia upregulate cell surface markers, which facilitates their migration to the site of the injury. Microglia demonstrate high levels of plasticity in their responses to CNS injuries (Kigerl et al., 2009; Perry et al., 2010). Remarkably, microglia play a dual-faced role in the progression of white matter injury after stroke or TBI (figure 2). On the one hand, microglia release ROS and pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α (Volpe, 2011), both of which are detrimental to neighboring oligodendrocytes. Activated microglia also produce glutamate (Takahashi et al., 2003), which exacerbates damage in oligodendrocytes and their progenitor cells following CNS insults (Kaur and Ling, 2009; Li et al., 2005; McTigue and Tripathi, 2008). On the other hand, activated microglia can also serve to resolve local inflammation, clear cellular debris, and provide protective factors to reduce oligodendrocyte injury or demyelination (Hanisch and Kettenmann, 2007; Wang et al., 2013). Recent studies have revealed that microglia assume different phenotypes with distinct destructive (M1-like phenotype) or protective (M2-like phenotype) functions at different stages after stroke or TBI (Figure 2) (Hu et al., 2015; Hu et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2013). Due to their pleiotropic functions, microglia may either accelerate or limit the spread of white matter pathology, depending on the context (Davalos et al., 2005; Miron et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2015). We have recently reviewed the differential roles of M1-like and M2-like microglia in oligodendrogenesis and white matter integrity (Hu et al., 2015). A deeper understanding of microglial activation will be critical for formulating effective therapeutic strategies for acute brain injuries.

Figure 2. Microglial activation after stroke or TBI.

After stroke or TBI, resting microglia are polarized toward the M1 or M2 phenotype. M1 microglia release multiple pro-inflammatory cytokines, leading to cell damage and exacerbate brain injury. However, M2 microglia secrete anti-inflammatory cytokines and growth factors, contributing to tissue repair.

4. The sequelae of demyelination

Myelination allows the rapid transfer of information that is needed for normal cognitive, emotional, and behavioral function (Deoni et al., 2011). Oligodendrocyte cell death and axonal demyelination lead to limited impulse propagation, and result in severe neurological dysfunction, including motor dysfunction, impaired cognitive abilities, psychiatric disorders, and neurodegeneration.

Motor dysfunction is the major neurological consequence of subcortical stroke and TBI and exhibits limited functional recovery. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has revealed dynamic changes in white matter during complex sensorimotor tasks such as playing the piano, juggling, and abacus use (Bengtsson et al., 2005; Hu et al., 2011; Scholz et al., 2009). Intriguingly, recent studies suggest that learning a complex motor skill requires the generation of new oligodendrocytes and active myelination processes (Long and Corfas, 2014; McKenzie et al., 2014). Therefore, demyelination after stroke or TBI might result in catastrophic motor dysfunction.

Microglia, oligodendrocytes, and astrocytes are major sources of extracellular matrix components in late stages of memory consolidation (Babayan et al., 2012). Growing evidence supports several forms of activity-dependent signaling between axons and myelin-forming oligodendrocytes (Wake et al., 2011). Furthermore, recognition and spatial memory are impaired after corpus callosal injury in vivo (Kouhsar et al., 2011; Shibata et al., 2007; Yoshizaki et al., 2008). There is growing awareness that TBI is an important risk factor for neurodegenerative diseases (Daneshvar et al., 2011; Masel and DeWitt, 2010). For example, individuals with a history of TBI show an increased incidence of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (Guo et al., 2000; Jellinger et al., 2001; Plassman et al., 2000). A higher incidence of neurodegeneration is related to impaired white matter integrity in a subset of white matter tracts such as the parahippocampal white matter, caudal portions of the cingulum, the inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus, and posterior portions of the corpus callosum, all of which are related to episodic memory impairments in early AD (Bendlin et al., 2010; Douaud et al., 2011; Gold et al., 2012; Gold et al., 2010; Smith et al., 2010).

5. Potential therapeutic targets related to demyelination

Although the adult brain has limited capacity for full remyelination and white matter repair, remyelination is known to occur to some extent after CNS injuries, with the goal of ensheathing demyelinated axons with new myelin, reinstating saltatory conduction, and reducing functional deficits. The white matter regenerative processes may be categorized into OPC proliferation, OPC migration towards the demyelinated axons, OPC differentiation, and final maturation into functional oligodendrocytes (Franklin and Ffrench-Constant, 2008; Zhang et al., 2013). OPCs are continuously present in the normal adult brain and proliferate actively soon after ischemic injury (Chu et al., 2012). It is also possible that without this active OPC proliferation, there would be even worse white matter injury and catastrophic tissue necrosis. Furthermore, replenishment of oligodendrocytes by OPCs can be observed in peri-infarct areas after ischemia (Mandai et al., 1997). Unfortunately, our recent studies show that, despite active OPC proliferation, ischemic white matter demyelination showed little improvement over time (Chu et al., 2012). This failure of remyelination despite robust regeneration of OPCs has also been reported in perinatal hypoxia/ischemia brain injury, and may be attributed to a persistent arrest in preoligodendrocyte maturation (Segovia et al., 2008). Furthermore, aging is known to interfere with oligodendrocyte regeneration and axonal remyelination (Sim et al., 2002). Multiple factors may cause regenerative failure in the adult CNS, including the weakness of intrinsic growth capacities and the inhibitory extrinsic environment. When remyelination fails after CNS insults, axons remain naked and vulnerable to degeneration, leading to the progressive irreversible disabilities (Duncan et al., 2009; Franklin and Ffrench-Constant, 2008; Irvine and Blakemore, 2008). Therefore, interventions that promote the remyelination of axons are potentially promising strategies to improve white matter integrity and functional recovery after CNS injuries (Chen et al., 2014; McLaughlin and Gidday, 2013; Plemel et al., 2014). Below we will discuss potential therapeutic strategies targeting remyelination after injury.

5.1 Increasing the proliferation of oligodendrocyte progenitor cells

OPCs persist in the adult CNS (~5% of all neural cells) and continue to divide and differentiate into myelinating oligodendrocytes throughout life (Richardson et al., 2011; Rivers et al., 2008; Young et al., 2013). After white matter injury, OPCs rapidly proliferate and migrate to fill the demyelinated area, differentiate into mature oligodendrocytes, and restore myelin sheaths. Studies have shown that subventricular zone-derived progenitors contribute to myelin repair (Menn et al., 2006). Exogenous OPC transplantation has proven effective in initiating myelin formation after demyelination (Windrem et al., 2002; Windrem et al., 2008). However, transplanted mature oligodendrocytes fail to form myelin (Blakemore and Keirstead, 1999). Fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2) and epidermal growth factor (EGF) both enhance OPC generation in pathological conditions (Scafidi et al., 2014; Whittaker et al., 2012). Furthermore, neurotrophins such as BDNF, PDGF-A, and NT3 specifically stimulate OPC proliferation (Girard et al., 2005; McTigue et al., 1998; Murtie et al., 2005; Woodruff et al., 2004). Thus, exogenous delivery of these factors to promote OPC proliferation may boost white matter recovery.

5.2 Enhancing oligodendrocyte progenitor cell migration

OPCs remain motile and can migrate within the CNS. A recent study has shown that vascular remodeling after acute demyelination lesions favors the migration of neuroblasts from their original niche to the newly lesioned site (Cayre et al., 2013). Exercise and enriched environments have been shown to increase subventricular zone mitotic activity and subventricular zone-derived progenitor mobilization toward demyelinated lesions, thereby improving long-term functional recovery (Magalon et al., 2007). Several factors can specifically regulate OPC migration. Guidance cues such as Sema3F (Piaton et al., 2011; Syed et al., 2011), reelin (Courtes et al., 2011), and netrin 1 (Cayre et al., 2013) are involved in progenitor migration in the early phases of the regenerative process. In addition, chondroitin sulphate proteoglycan (CSPG), an extracellular matrix protein, is a negative regulator of myelin repair that limits OPC migration toward the lesion site and inhibits axonal regeneration (Siebert and Osterhout, 2011; Siebert et al., 2011). Therefore, treatment with the enzyme chondroitinase ABC (cABC), which removes the glycosaminoglycan side chains of CSPG, might reverse the inhibitory effects of CSPGs on OPC migration and enhance remyelination (Siebert and Osterhout, 2011; Siebert et al., 2011).

5.3 Promoting oligodendrocyte progenitor cell differentiation

Although an increase in OPC number is essential for recovery after CNS injury, it is not sufficient to induce remyelination by itself (Barres and Raff, 1999). Accumulating evidence emphasizes that the differentiation of OPCs into mature myelinating oligodendrocytes is essential for effective remyelination and recovery (Emery, 2010; Fancy et al., 2011; Miron et al., 2011). Promoting oligodendrocyte differentiation has therefore been proposed as a therapeutic strategy to enhance white matter repair. To this end, the molecules regulating OPC differentiation have received considerable attention. Several molecules, including fibronectins (Stoffels et al., 2013), LINGO-1 (Jepson et al., 2012; Mi et al., 2009; Mi et al., 2013), PSA-NCAM (Koutsoudaki et al., 2010) and the Wnt/β-catenin/Tcf4 signaling pathway (See and Grinspan, 2009) have been shown to negatively regulate OPC differentiation. In contrast, EGF, bFGF and PDGFa have been reported to promote OPC differentiation (El Waly et al., 2014; Karimi-Abdolrezaee et al., 2012). Therefore, reducing the differentiation inhibitors and/or boosting the differentiation promoting factors may improve white matter repair after stroke or TBI.

6. Conclusions

The past few decades have witnessed a significant increase in our knowledge about demyelination after stroke and TBI. For example, we now know that white matter injury accounts for up to half of the lesion volume in patients and leads to devastating neurological impairments (Edlow and Wu, 2012; Ho et al., 2005; Hulkower et al., 2013). Increasing numbers of molecules critical for the initiation, progression, or repair of demyelination have been identified and may serve as therapeutic targets to promote recovery after brain injuries. However, there are still many obstacles that hinder the development of clinically feasible therapies for demyelination. First, several molecules may possess dual roles in demyelination/remyelination processes. For example, proteoglycan CSPG, a major component of scar tissue known to hinder OPC migration and axonal regeneration, can induce the switch to a beneficial microglial M2 phenotype during acute phases of CNS injury (Rolls et al., 2008). For any strategies targeting these molecules, the treatment regimens will therefore have to be carefully designed to avoid unwanted side effects. Second, most of the demyelination-regulating molecules are not tissue or cell type specific, and the development of cell specific drug delivery systems will be essential. As the central role of demyelination becomes increasingly clear, further studies on ways to improve myelin integrity and protect both gray and white matter are warranted so that long-lasting functional recovery can finally be achieved in stroke and TBI victims.

Highlights.

Demyelination contributes to long-term functional deficits after stroke or TBI

Mechanisms of demyelination and oligodendrocyte death in acute brain injury

Crosstalk between oligodendrocytes and other white matter components

Potential therapeutic targets related to demyelination and remyelination

Acknowledgments

This work was supported the Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai grant 14ZR1434600 (to H.S.), Natural Science Foundation of China grants 81171149 and 81371306 (to Y.G.), and 81228008 (to J.C.), The Shanghai Committee of Science and Technology Research Program 14431907002 (to Y.G.), American Heart Association Scientist Development Grant 13SDG14570025 (to X.H.), Doctoral Training Fund from Chinese Ministry of Education 20120071110042 (to J.C.), NIH/NINDS grants NS36736, NS43802, NS45048 and NS089534 (to J.C.), and the Department of Veterans Affairs Research Career Scientist Award and RR & D Merit Review (to J.C.).

List of abbreviations

- AMPA

α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid

- CNP

2′,3′-cyclicnucleotide 3′-phosphodiesterase

- CNS

central nervous system

- EAAT

excitatory amino acid transporters

- IFN

interferon

- IL

interleukin

- MCT

monocarboxylic acid transporter

- NMDA

N-methyl D-aspartate

- NO

nitric oxide

- OGD

oxygen glucose deprivation

- OPC

oligodendrocyte precursor cell

- OXPHOS

oxidative phosphorylation

- PARP

a poly[ADP]-ribose polymerase

- PLP

proteolipid protein

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- TBI

traumatic brain injury

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Al-Saktawi K, McLaughlin M, Klugmann M, Schneider A, Barrie JA, McCulloch MC, Montague P, Kirkham D, Nave KA, Griffiths IR. Genetic background determines phenotypic severity of the Plp rumpshaker mutation. J Neurosci Res. 2003;72:12–24. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alberdi E, Sanchez-Gomez MV, Marino A, Matute C. Ca(2+) influx through AMPA or kainate receptors alone is sufficient to initiate excitotoxicity in cultured oligodendrocytes. Neurobiol Dis. 2002;9:234–243. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2001.0457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaral AI, Meisingset TW, Kotter MR, Sonnewald U. Metabolic aspects of neuron-oligodendrocyte-astrocyte interactions. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2013;4:54. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2013.00054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An C, Shi Y, Li P, Hu X, Gan Y, Stetler RA, Leak RK, Gao Y, Sun BL, Zheng P, Chen J. Molecular dialogs between the ischemic brain and the peripheral immune system: dualistic roles in injury and repair. Prog Neurobiol. 2014;115:6–24. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babayan AH, Kramar EA, Barrett RM, Jafari M, Haettig J, Chen LY, Rex CS, Lauterborn JC, Wood MA, Gall CM, Lynch G. Integrin dynamics produce a delayed stage of long-term potentiation and memory consolidation. J Neurosci. 2012;32:12854–12861. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2024-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Back SA, Craig A, Kayton RJ, Luo NL, Meshul CK, Allcock N, Fern R. Hypoxia-ischemia preferentially triggers glutamate depletion from oligodendroglia and axons in perinatal cerebral white matter. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:334–347. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakiri Y, Hamilton NB, Karadottir R, Attwell D. Testing NMDA receptor block as a therapeutic strategy for reducing ischaemic damage to CNS white matter. Glia. 2008;56:233–240. doi: 10.1002/glia.20608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barres BA, Raff MC. Axonal control of oligodendrocyte development. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:1123–1128. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.6.1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter P, Chen Y, Xu Y, Swanson RA. Mitochondrial dysfunction induced by nuclear poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1: a treatable cause of cell death in stroke. Transl Stroke Res. 2014;5:136–144. doi: 10.1007/s12975-013-0283-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benarroch EE. Oligodendrocytes: Susceptibility to injury and involvement in neurologic disease. Neurology. 2009;72:1779–1785. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181a6b123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendlin BB, Ries ML, Canu E, Sodhi A, Lazar M, Alexander AL, Carlsson CM, Sager MA, Asthana S, Johnson SC. White matter is altered with parental family history of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2010;6:394–403. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bengtsson SL, Nagy Z, Skare S, Forsman L, Forssberg H, Ullen F. Extensive piano practicing has regionally specific effects on white matter development. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1148–1150. doi: 10.1038/nn1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakemore WF, Keirstead HS. The origin of remyelinating cells in the central nervous system. J Neuroimmunol. 1999;98:69–76. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(99)00083-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonora M, De Marchi E, Patergnani S, Suski JM, Celsi F, Bononi A, Giorgi C, Marchi S, Rimessi A, Duszynski J, Pozzan T, Wieckowski MR, Pinton P. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha impairs oligodendroglial differentiation through a mitochondria-dependent process. Cell Death Differ. 2014;21:1198–1208. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2014.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremer J, Baumann F, Tiberi C, Wessig C, Fischer H, Schwarz P, Steele AD, Toyka KV, Nave KA, Weis J, Aguzzi A. Axonal prion protein is required for peripheral myelin maintenance. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:310–318. doi: 10.1038/nn.2483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butt AM. Neurotransmitter-mediated calcium signalling in oligodendrocyte physiology and pathology. Glia. 2006;54:666–675. doi: 10.1002/glia.20424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caprariello AV, Mangla S, Miller RH, Selkirk SM. Apoptosis of oligodendrocytes in the central nervous system results in rapid focal demyelination. Ann Neurol. 2012;72:395–405. doi: 10.1002/ana.23606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho KS. Mitochondrial dysfunction in demyelinating diseases. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2013;20:194–201. doi: 10.1016/j.spen.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cayre M, Courtes S, Martineau F, Giordano M, Arnaud K, Zamaron A, Durbec P. Netrin 1 contributes to vascular remodeling in the subventricular zone and promotes progenitor emigration after demyelination. Development. 2013;140:3107–3117. doi: 10.1242/dev.092999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra D, Choy G, Deng X, Bhatia B, Daniel P, Tang DG. Association of active caspase 8 with the mitochondrial membrane during apoptosis: potential roles in cleaving BAP31 and caspase 3 and mediating mitochondrion-endoplasmic reticulum cross talk in etoposide-induced cell death. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:6592–6607. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.15.6592-6607.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D, Yu SP, Wei L. Ion channels in regulation of neuronal regenerative activities. Transl Stroke Res. 2014;5:156–162. doi: 10.1007/s12975-013-0320-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chew LJ, King WC, Kennedy A, Gallo V. Interferon-gamma inhibits cell cycle exit in differentiating oligodendrocyte progenitor cells. Glia. 2005;52:127–143. doi: 10.1002/glia.20232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu M, Hu X, Lu S, Gan Y, Li P, Guo Y, Zhang J, Chen J, Gao Y. Focal cerebral ischemia activates neurovascular restorative dynamics in mouse brain. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) 2012;4:1926–1936. doi: 10.2741/513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin JG, Kelly D, Rath EM, Baerwald KD, Suzuki K, Popko B. Targeted CNS expression of interferon-gamma in transgenic mice leads to hypomyelination, reactive gliosis, and abnormal cerebellar development. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1996;7:354–370. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1996.0026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtes S, Vernerey J, Pujadas L, Magalon K, Cremer H, Soriano E, Durbec P, Cayre M. Reelin controls progenitor cell migration in the healthy and pathological adult mouse brain. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20430. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curatolo L, Valsasina B, Caccia C, Raimondi GL, Orsini G, Bianchetti A. Recombinant human IL-2 is cytotoxic to oligodendrocytes after in vitro self aggregation. Cytokine. 1997;9:734–739. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1997.0228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czabotar PE, Lessene G, Strasser A, Adams JM. Control of apoptosis by the BCL-2 protein family: implications for physiology and therapy. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:49–63. doi: 10.1038/nrm3722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daneman R. The blood-brain barrier in health and disease. Ann Neurol. 2012;72:648–672. doi: 10.1002/ana.23648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daneshvar DH, Riley DO, Nowinski CJ, McKee AC, Stern RA, Cantu RC. Long-term consequences: effects on normal development profile after concussion. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2011;22:683–700. ix. doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2011.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davalos D, Grutzendler J, Yang G, Kim JV, Zuo Y, Jung S, Littman DR, Dustin ML, Gan WB. ATP mediates rapid microglial response to local brain injury in vivo. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:752–758. doi: 10.1038/nn1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Y, Lu J, Sivakumar V, Ling EA, Kaur C. Amoeboid microglia in the periventricular white matter induce oligodendrocyte damage through expression of proinflammatory cytokines via MAP kinase signaling pathway in hypoxic neonatal rats. Brain Pathol. 2008;18:387–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2008.00138.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng YY, Lu J, Ling EA, Kaur C. Microglia-derived macrophage colony stimulating factor promotes generation of proinflammatory cytokines by astrocytes in the periventricular white matter in the hypoxic neonatal brain. Brain Pathol. 2010;20:909–925. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2010.00387.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deoni SC, Mercure E, Blasi A, Gasston D, Thomson A, Johnson M, Williams SC, Murphy DG. Mapping infant brain myelination with magnetic resonance imaging. J Neurosci. 2011;31:784–791. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2106-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmond DW. Cognition and white matter lesions. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2002;13(Suppl 2):53–57. doi: 10.1159/000049151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domercq M, Etxebarria E, Perez-Samartin A, Matute C. Excitotoxic oligodendrocyte death and axonal damage induced by glutamate transporter inhibition. Glia. 2005;52:36–46. doi: 10.1002/glia.20221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domercq M, Mato S, Soria FN, Sanchez-gomez MV, Alberdi E, Matute C. Zn2+-induced ERK activation mediates PARP-1-dependent ischemic-reoxygenation damage to oligodendrocytes. Glia. 2013;61:383–393. doi: 10.1002/glia.22441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douaud G, Jbabdi S, Behrens TE, Menke RA, Gass A, Monsch AU, Rao A, Whitcher B, Kindlmann G, Matthews PM, Smith S. DTI measures in crossing-fibre areas: increased diffusion anisotropy reveals early white matter alteration in MCI and mild Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroimage. 2011;55:880–890. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan ID, Brower A, Kondo Y, Curlee JF, Jr, Schultz RD. Extensive remyelination of the CNS leads to functional recovery. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:6832–6836. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812500106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar JM, McCulloch MC, Montague P, Brown AM, Thilemann S, Pratola L, Gruenenfelder FI, Griffiths IR, Nave KA. Demyelination and axonal preservation in a transgenic mouse model of Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease. EMBO Mol Med. 2010;2:42–50. doi: 10.1002/emmm.200900057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edlow BL, Wu O. Advanced neuroimaging in traumatic brain injury. Semin Neurol. 2012;32:374–400. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1331810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Waly B, Macchi M, Cayre M, Durbec P. Oligodendrogenesis in the normal and pathological central nervous system. Front Neurosci. 2014;8:145. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2014.00145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery B. Regulation of oligodendrocyte differentiation and myelination. Science. 2010;330:779–782. doi: 10.1126/science.1190927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fancy SP, Chan JR, Baranzini SE, Franklin RJ, Rowitch DH. Myelin regeneration: a recapitulation of development? Annu Rev Neurosci. 2011;34:21–43. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-061010-113629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fern RF, Matute C, Stys PK. White matter injury: Ischemic and nonischemic. Glia. 2014;62:1780–1789. doi: 10.1002/glia.22722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer R, Wajant H, Kontermann R, Pfizenmaier K, Maier O. Astrocyte-specific activation of TNFR2 promotes oligodendrocyte maturation by secretion of leukemia inhibitory factor. Glia. 2014;62:272–283. doi: 10.1002/glia.22605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin RJ, Ffrench-Constant C. Remyelination in the CNS: from biology to therapy. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:839–855. doi: 10.1038/nrn2480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funfschilling U, Supplie LM, Mahad D, Boretius S, Saab AS, Edgar J, Brinkmann BG, Kassmann CM, Tzvetanova ID, Mobius W, Diaz F, Meijer D, Suter U, Hamprecht B, Sereda MW, Moraes CT, Frahm J, Goebbels S, Nave KA. Glycolytic oligodendrocytes maintain myelin and long-term axonal integrity. Nature. 2012;485:517–521. doi: 10.1038/nature11007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillum RF, Kwagyan J, Obisesan TO. Ethnic and geographic variation in stroke mortality trends. Stroke. 2011;42:3294–3296. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.625343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girard C, Bemelmans AP, Dufour N, Mallet J, Bachelin C, Nait-Oumesmar B, Baron-Van Evercooren A, Lachapelle F. Grafts of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and neurotrophin 3-transduced primate Schwann cells lead to functional recovery of the demyelinated mouse spinal cord. J Neurosci. 2005;25:7924–7933. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4890-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold BT, Johnson NF, Powell DK, Smith CD. White matter integrity and vulnerability to Alzheimer’s disease: preliminary findings and future directions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1822:416–422. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold BT, Powell DK, Andersen AH, Smith CD. Alterations in multiple measures of white matter integrity in normal women at high risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroimage. 2010;52:1487–1494. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.05.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Z, Cupples LA, Kurz A, Auerbach SH, Volicer L, Chui H, Green RC, Sadovnick AD, Duara R, DeCarli C, Johnson K, Go RC, Growdon JH, Haines JL, Kukull WA, Farrer LA. Head injury and the risk of AD in the MIRAGE study. Neurology. 2000;54:1316–1323. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.6.1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanisch UK, Kettenmann H. Microglia: active sensor and versatile effector cells in the normal and pathologic brain. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1387–1394. doi: 10.1038/nn1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herx LM, Rivest S, Yong VW. Central nervous system-initiated inflammation and neurotrophism in trauma: IL-1 beta is required for the production of ciliary neurotrophic factor. J Immunol. 2000;165:2232–2239. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.4.2232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho PW, Reutens DC, Phan TG, Wright PM, Markus R, Indra I, Young D, Donnan GA. Is white matter involved in patients entered into typical trials of neuroprotection? Stroke. 2005;36:2742–2744. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000189748.52500.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovelmeyer N, Hao Z, Kranidioti K, Kassiotis G, Buch T, Frommer F, von Hoch L, Kramer D, Minichiello L, Kollias G, Lassmann H, Waisman A. Apoptosis of oligodendrocytes via Fas and TNF-R1 is a key event in the induction of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2005;175:5875–5884. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.9.5875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X, Leak RK, Shi Y, Suenaga J, Gao Y, Zheng P, Chen J. Microglial and macrophage polarization-new prospects for brain repair. Nat Rev Neurol. 2015;11:56–64. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2014.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X, Li P, Guo Y, Wang H, Leak RK, Chen S, Gao Y, Chen J. Microglia/macrophage polarization dynamics reveal novel mechanism of injury expansion after focal cerebral ischemia. Stroke. 2012;43:3063–3070. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.659656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X, Liou AK, Leak RK, Xu M, An C, Suenaga J, Shi Y, Gao Y, Zheng P, Chen J. Neurobiology of microglial action in CNS injuries: receptor-mediated signaling mechanisms and functional roles. Prog Neurobiol. 2014;119–120:60–84. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Geng F, Tao L, Hu N, Du F, Fu K, Chen F. Enhanced white matter tracts integrity in children with abacus training. Hum Brain Mapp. 2011;32:10–21. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulkower MB, Poliak DB, Rosenbaum SB, Zimmerman ME, Lipton ML. A decade of DTI in traumatic brain injury: 10 years and 100 articles later. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2013;34:2064–2074. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husain J, Juurlink BH. Oligodendroglial precursor cell susceptibility to hypoxia is related to poor ability to cope with reactive oxygen species. Brain Res. 1995;698:86–94. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00832-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvine KA, Blakemore WF. Remyelination protects axons from demyelination-associated axon degeneration. Brain. 2008;131:1464–1477. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jellinger KA, Paulus W, Wrocklage C, Litvan I. Traumatic brain injury as a risk factor for Alzheimer disease. Comparison of two retrospective autopsy cohorts with evaluation of ApoE genotype. BMC Neurol. 2001;1:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-1-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jepson S, Vought B, Gross CH, Gan L, Austen D, Frantz JD, Zwahlen J, Lowe D, Markland W, Krauss R. LINGO-1, a transmembrane signaling protein, inhibits oligodendrocyte differentiation and myelination through intercellular self-interactions. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:22184–22195. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.366179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone JT, Morton PD, Jayakumar AR, Johnstone AL, Gao H, Bracchi-Ricard V, Pearse DD, Norenberg MD, Bethea JR. Inhibition of NADPH oxidase activation in oligodendrocytes reduces cytotoxicity following trauma. PLoS One. 2013;8:e80975. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juurlink BH. Response of glial cells to ischemia: roles of reactive oxygen species and glutathione. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1997;21:151–166. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(96)00005-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karadottir R, Cavelier P, Bergersen LH, Attwell D. NMDA receptors are expressed in oligodendrocytes and activated in ischaemia. Nature. 2005;438:1162–1166. doi: 10.1038/nature04302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimi-Abdolrezaee S, Schut D, Wang J, Fehlings MG. Chondroitinase and growth factors enhance activation and oligodendrocyte differentiation of endogenous neural precursor cells after spinal cord injury. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37589. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassmann CM. Myelin peroxisomes - essential organelles for the maintenance of white matter in the nervous system. Biochimie. 2014;98:111–118. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2013.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur C, Ling EA. Periventricular white matter damage in the hypoxic neonatal brain: role of microglial cells. Prog Neurobiol. 2009;87:264–280. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kigerl KA, Gensel JC, Ankeny DP, Alexander JK, Donnelly DJ, Popovich PG. Identification of two distinct macrophage subsets with divergent effects causing either neurotoxicity or regeneration in the injured mouse spinal cord. J Neurosci. 2009;29:13435–13444. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3257-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Steelman AJ, Koito H, Li J. Astrocytes promote TNF-mediated toxicity to oligodendrocyte precursors. J Neurochem. 2011;116:53–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07084.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinsimlinghaus K, Marx R, Serdar M, Bendix I, Dietzel ID. Strategies for repair of white matter: influence of osmolarity and microglia on proliferation and apoptosis of oligodendrocyte precursor cells in different basal culture media. Front Cell Neurosci. 2013;7:277. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2013.00277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolodziejczyk K, Saab AS, Nave KA, Attwell D. Why do oligodendrocyte lineage cells express glutamate receptors? F1000 Biol Rep. 2010;2:57. doi: 10.3410/B2-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong Y, Trabucco SE, Zhang H. Oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction and the mitochondria theory of aging. Interdiscip Top Gerontol. 2014;39:86–107. doi: 10.1159/000358901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostic M, Zivkovic N, Stojanovic I. Multiple sclerosis and glutamate excitotoxicity. Rev Neurosci. 2013;24:71–88. doi: 10.1515/revneuro-2012-0062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouhsar SS, Karami M, Tafreshi AP, Roghani M, Nadoushan MR. Microinjection of l-arginine into corpus callosum cause reduction in myelin concentration and neuroinflammation. Brain Res. 2011;1392:93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koutsoudaki PN, Hildebrandt H, Gudi V, Skripuletz T, Skuljec J, Stangel M. Remyelination after cuprizone induced demyelination is accelerated in mice deficient in the polysialic acid synthesizing enzyme St8siaIV. Neuroscience. 2010;171:235–244. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.08.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukley M, Capetillo-Zarate E, Dietrich D. Vesicular glutamate release from axons in white matter. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:311–320. doi: 10.1038/nn1850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai TW, Zhang S, Wang YT. Excitotoxicity and stroke: identifying novel targets for neuroprotection. Prog Neurobiol. 2014;115:157–188. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lappe-Siefke C, Goebbels S, Gravel M, Nicksch E, Lee J, Braun PE, Griffiths IR, Nave KA. Disruption of Cnp1 uncouples oligodendroglial functions in axonal support and myelination. Nat Genet. 2003;33:366–374. doi: 10.1038/ng1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara-Ramirez R, Segura-Anaya E, Martinez-Gomez A, Dent MA. Expression of interleukin-6 receptor alpha in normal and injured rat sciatic nerve. Neuroscience. 2008;152:601–608. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y, Morrison BM, Li Y, Lengacher S, Farah MH, Hoffman PN, Liu Y, Tsingalia A, Jin L, Zhang PW, Pellerin L, Magistretti PJ, Rothstein JD. Oligodendroglia metabolically support axons and contribute to neurodegeneration. Nature. 2012;487:443–448. doi: 10.1038/nature11314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Ramenaden ER, Peng J, Koito H, Volpe JJ, Rosenberg PA. Tumor necrosis factor alpha mediates lipopolysaccharide-induced microglial toxicity to developing oligodendrocytes when astrocytes are present. J Neurosci. 2008;28:5321–5330. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3995-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li WW, Setzu A, Zhao C, Franklin RJ. Minocycline-mediated inhibition of microglia activation impairs oligodendrocyte progenitor cell responses and remyelination in a non-immune model of demyelination. J Neuroimmunol. 2005;158:58–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin W, Harding HP, Ron D, Popko B. Endoplasmic reticulum stress modulates the response of myelinating oligodendrocytes to the immune cytokine interferon-gamma. J Cell Biol. 2005;169:603–612. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200502086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisak RP, Benjamins JA, Bealmear B, Nedelkoska L, Studzinski D, Retland E, Yao B, Land S. Differential effects of Th1, monocyte/macrophage and Th2 cytokine mixtures on early gene expression for molecules associated with metabolism, signaling and regulation in central nervous system mixed glial cell cultures. J Neuroinflammation. 2009;6:4. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-6-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long P, Corfas G. Neuroscience. To learn is to myelinate. Science. 2014;346:298–299. doi: 10.1126/science.1261127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magalon K, Cantarella C, Monti G, Cayre M, Durbec P. Enriched environment promotes adult neural progenitor cell mobilization in mouse demyelination models. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;25:761–771. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahad D, Lassmann H, Turnbull D. Review: Mitochondria and disease progression in multiple sclerosis. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2008;34:577–589. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2008.00987.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier O, Fischer R, Agresti C, Pfizenmaier K. TNF receptor 2 protects oligodendrocyte progenitor cells against oxidative stress. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;440:336–341. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.09.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandai K, Matsumoto M, Kitagawa K, Matsushita K, Ohtsuki T, Mabuchi T, Colman DR, Kamada T, Yanagihara T. Ischemic damage and subsequent proliferation of oligodendrocytes in focal cerebral ischemia. Neuroscience. 1997;77:849–861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masel BE, DeWitt DS. Traumatic brain injury: a disease process, not an event. J Neurotrauma. 2010;27:1529–1540. doi: 10.1089/neu.2010.1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mato S, Sanchez-Gomez MV, Bernal-Chico A, Matute C. Cytosolic zinc accumulation contributes to excitotoxic oligodendroglial death. Glia. 2013;61:750–764. doi: 10.1002/glia.22470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matute C. Glutamate and ATP signalling in white matter pathology. J Anat. 2011;219:53–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2010.01339.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matute C, Alberdi E, Domercq M, Sanchez-Gomez MV, Perez-Samartin A, Rodriguez-Antiguedad A, Perez-Cerda F. Excitotoxic damage to white matter. J Anat. 2007;210:693–702. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2007.00733.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matute C, Domercq M, Perez-Samartin A, Ransom BR. Protecting white matter from stroke injury. Stroke. 2013;44:1204–1211. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.658328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matute C, Domercq M, Sanchez-Gomez MV. Glutamate-mediated glial injury: mechanisms and clinical importance. Glia. 2006;53:212–224. doi: 10.1002/glia.20275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald JW, Althomsons SP, Hyrc KL, Choi DW, Goldberg MP. Oligodendrocytes from forebrain are highly vulnerable to AMPA/kainate receptor-mediated excitotoxicity. Nat Med. 1998;4:291–297. doi: 10.1038/nm0398-291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie IA, Ohayon D, Li H, de Faria JP, Emery B, Tohyama K, Richardson WD. Motor skill learning requires active central myelination. Science. 2014;346:318–322. doi: 10.1126/science.1254960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin B, Gidday JM. Poised for success: implementation of sound conditioning strategies to promote endogenous protective responses to stroke in patients. Transl Stroke Res. 2013;4:104–113. doi: 10.1007/s12975-012-0240-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McTigue DM, Horner PJ, Stokes BT, Gage FH. Neurotrophin-3 and brain-derived neurotrophic factor induce oligodendrocyte proliferation and myelination of regenerating axons in the contused adult rat spinal cord. J Neurosci. 1998;18:5354–5365. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-14-05354.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McTigue DM, Tripathi RB. The life, death, and replacement of oligodendrocytes in the adult CNS. J Neurochem. 2008;107:1–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menichella DM, Majdan M, Awatramani R, Goodenough DA, Sirkowski E, Scherer SS, Paul DL. Genetic and physiological evidence that oligodendrocyte gap junctions contribute to spatial buffering of potassium released during neuronal activity. J Neurosci. 2006;26:10984–10991. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0304-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menn B, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Yaschine C, Gonzalez-Perez O, Rowitch D, Alvarez-Buylla A. Origin of oligodendrocytes in the subventricular zone of the adult brain. J Neurosci. 2006;26:7907–7918. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1299-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mi S, Miller RH, Tang W, Lee X, Hu B, Wu W, Zhang Y, Shields CB, Zhang Y, Miklasz S, Shea D, Mason J, Franklin RJ, Ji B, Shao Z, Chedotal A, Bernard F, Roulois A, Xu J, Jung V, Pepinsky B. Promotion of central nervous system remyelination by induced differentiation of oligodendrocyte precursor cells. Ann Neurol. 2009;65:304–315. doi: 10.1002/ana.21581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mi S, Pepinsky RB, Cadavid D. Blocking LINGO-1 as a therapy to promote CNS repair: from concept to the clinic. CNS Drugs. 2013;27:493–503. doi: 10.1007/s40263-013-0068-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micu I, Jiang Q, Coderre E, Ridsdale A, Zhang L, Woulfe J, Yin X, Trapp BD, McRory JE, Rehak R, Zamponi GW, Wang W, Stys PK. NMDA receptors mediate calcium accumulation in myelin during chemical ischaemia. Nature. 2006;439:988–992. doi: 10.1038/nature04474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miron VE, Boyd A, Zhao JW, Yuen TJ, Ruckh JM, Shadrach JL, van Wijngaarden P, Wagers AJ, Williams A, Franklin RJ, ffrench-Constant C. M2 microglia and macrophages drive oligodendrocyte differentiation during CNS remyelination. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:1211–1218. doi: 10.1038/nn.3469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miron VE, Kuhlmann T, Antel JP. Cells of the oligodendroglial lineage, myelination, and remyelination. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1812:184–193. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2010.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto N, Maki T, Pham LD, Hayakawa K, Seo JH, Mandeville ET, Mandeville JB, Kim KW, Lo EH, Arai K. Oxidative stress interferes with white matter renewal after prolonged cerebral hypoperfusion in mice. Stroke. 2013;44:3516–3521. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.002813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison BM, Lee Y, Rothstein JD. Oligodendroglia: metabolic supporters of axons. Trends Cell Biol. 2013;23:644–651. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2013.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy MP. How mitochondria produce reactive oxygen species. Biochem J. 2009;417:1–13. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murtie JC, Zhou YX, Le TQ, Vana AC, Armstrong RC. PDGF and FGF2 pathways regulate distinct oligodendrocyte lineage responses in experimental demyelination with spontaneous remyelination. Neurobiol Dis. 2005;19:171–182. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nave KA. Myelination and support of axonal integrity by glia. Nature. 2010a;468:244–252. doi: 10.1038/nature09614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nave KA. Myelination and the trophic support of long axons. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010b;11:275–283. doi: 10.1038/nrn2797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nave KA, Trapp BD. Axon-glial signaling and the glial support of axon function. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2008;31:535–561. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.30.051606.094309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newmeyer DD, Ferguson-Miller S. Mitochondria: releasing power for life and unleashing the machineries of death. Cell. 2003;112:481–490. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00116-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orthmann-Murphy JL, Freidin M, Fischer E, Scherer SS, Abrams CK. Two distinct heterotypic channels mediate gap junction coupling between astrocyte and oligodendrocyte connexins. J Neurosci. 2007;27:13949–13957. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3395-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens K, Park JH, Schuh R, Kristian T. Mitochondrial dysfunction and NAD(+) metabolism alterations in the pathophysiology of acute brain injury. Transl Stroke Res. 2013;4:618–634. doi: 10.1007/s12975-013-0278-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang Y, Cai Z, Rhodes PG. Effect of tumor necrosis factor-alpha on developing optic nerve oligodendrocytes in culture. J Neurosci Res. 2005;80:226–234. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantoni L, Garcia JH, Gutierrez JA. Cerebral white matter is highly vulnerable to ischemia. Stroke. 1996;27:1641–1646. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.9.1641. discussion 1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry VH, Nicoll JA, Holmes C. Microglia in neurodegenerative disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2010;6:193–201. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2010.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petito CK, Olarte JP, Roberts B, Nowak TS, Jr, Pulsinelli WA. Selective glial vulnerability following transient global ischemia in rat brain. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1998;57:231–238. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199803000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham LD, Hayakawa K, Seo JH, Nguyen MN, Som AT, Lee BJ, Guo S, Kim KW, Lo EH, Arai K. Crosstalk between oligodendrocytes and cerebral endothelium contributes to vascular remodeling after white matter injury. Glia. 2012;60:875–881. doi: 10.1002/glia.22320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piaton G, Aigrot MS, Williams A, Moyon S, Tepavcevic V, Moutkine I, Gras J, Matho KS, Schmitt A, Soellner H, Huber AB, Ravassard P, Lubetzki C. Class 3 semaphorins influence oligodendrocyte precursor recruitment and remyelination in adult central nervous system. Brain. 2011;134:1156–1167. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzi M, Sarnico I, Boroni F, Benarese M, Dreano M, Garotta G, Valerio A, Spano P. Prevention of neuron and oligodendrocyte degeneration by interleukin-6 (IL-6) and IL-6 receptor/IL-6 fusion protein in organotypic hippocampal slices. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2004;25:301–311. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2003.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plassman BL, Havlik RJ, Steffens DC, Helms MJ, Newman TN, Drosdick D, Phillips C, Gau BA, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Burke JR, Guralnik JM, Breitner JC. Documented head injury in early adulthood and risk of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. Neurology. 2000;55:1158–1166. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.8.1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plemel JR, Keough MB, Duncan GJ, Sparling JS, Yong VW, Stys PK, Tetzlaff W. Remyelination after spinal cord injury: is it a target for repair? Prog Neurobiol. 2014;117:54–72. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pusic AD, Pusic KM, Clayton BL, Kraig RP. IFNgamma-stimulated dendritic cell exosomes as a potential therapeutic for remyelination. J Neuroimmunol. 2014;266:12–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2013.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rash JE. Molecular disruptions of the panglial syncytium block potassium siphoning and axonal saltatory conduction: pertinence to neuromyelitis optica and other demyelinating diseases of the central nervous system. Neuroscience. 2010;168:982–1008. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson WD, Young KM, Tripathi RB, McKenzie I. NG2-glia as multipotent neural stem cells: fact or fantasy? Neuron. 2011;70:661–673. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivers LE, Young KM, Rizzi M, Jamen F, Psachoulia K, Wade A, Kessaris N, Richardson WD. PDGFRA/NG2 glia generate myelinating oligodendrocytes and piriform projection neurons in adult mice. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:1392–1401. doi: 10.1038/nn.2220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers JM, Robinson AP, Rosler ES, Lariosa-Willingham K, Persons RE, Dugas JC, Miller SD. IL-17A activates ERK1/2 and enhances differentiation of oligodendrocyte progenitor cells. Glia. 2014 doi: 10.1002/glia.22783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolls A, Shechter R, London A, Segev Y, Jacob-Hirsch J, Amariglio N, Rechavi G, Schwartz M. Two faces of chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan in spinal cord repair: a role in microglia/macrophage activation. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e171. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roozenbeek B, Maas AI, Menon DK. Changing patterns in the epidemiology of traumatic brain injury. Nat Rev Neurol. 2013;9:231–236. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2013.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz A, Matute C, Alberdi E. Intracellular Ca2+ release through ryanodine receptors contributes to AMPA receptor-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction and ER stress in oligodendrocytes. Cell Death Dis. 2010;1:e54. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2010.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saab AS, Tzvetanova ID, Nave KA. The role of myelin and oligodendrocytes in axonal energy metabolism. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2013;23:1065–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salter MG, Fern R. NMDA receptors are expressed in developing oligodendrocyte processes and mediate injury. Nature. 2005;438:1167–1171. doi: 10.1038/nature04301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scafidi J, Hammond TR, Scafidi S, Ritter J, Jablonska B, Roncal M, Szigeti-Buck K, Coman D, Huang Y, McCarter RJ, Jr, Hyder F, Horvath TL, Gallo V. Intranasal epidermal growth factor treatment rescues neonatal brain injury. Nature. 2014;506:230–234. doi: 10.1038/nature12880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholz J, Klein MC, Behrens TE, Johansen-Berg H. Training induces changes in white-matter architecture. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:1370–1371. doi: 10.1038/nn.2412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- See JM, Grinspan JB. Sending mixed signals: bone morphogenetic protein in myelination and demyelination. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2009;68:595–604. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181a66ad9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segovia KN, McClure M, Moravec M, Luo NL, Wan Y, Gong X, Riddle A, Craig A, Struve J, Sherman LS, Back SA. Arrested oligodendrocyte lineage maturation in chronic perinatal white matter injury. Ann Neurol. 2008;63:520–530. doi: 10.1002/ana.21359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semple BD, Blomgren K, Gimlin K, Ferriero DM, Noble-Haeusslein LJ. Brain development in rodents and humans: Identifying benchmarks of maturation and vulnerability to injury across species. Prog Neurobiol. 2013;106–107:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shereen A, Nemkul N, Yang D, Adhami F, Dunn RS, Hazen ML, Nakafuku M, Ning G, Lindquist DM, Kuan CY. Ex vivo diffusion tensor imaging and neuropathological correlation in a murine model of hypoxia-ischemia-induced thrombotic stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2011;31:1155–1169. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata M, Yamasaki N, Miyakawa T, Kalaria RN, Fujita Y, Ohtani R, Ihara M, Takahashi R, Tomimoto H. Selective impairment of working memory in a mouse model of chronic cerebral hypoperfusion. Stroke. 2007;38:2826–2832. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.490151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siebert JR, Osterhout DJ. The inhibitory effects of chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans on oligodendrocytes. J Neurochem. 2011;119:176–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siebert JR, Stelzner DJ, Osterhout DJ. Chondroitinase treatment following spinal contusion injury increases migration of oligodendrocyte progenitor cells. Exp Neurol. 2011;231:19–29. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim FJ, Zhao C, Penderis J, Franklin RJ. The age-related decrease in CNS remyelination efficiency is attributable to an impairment of both oligodendrocyte progenitor recruitment and differentiation. J Neurosci. 2002;22:2451–2459. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-07-02451.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CD, Chebrolu H, Andersen AH, Powell DA, Lovell MA, Xiong S, Gold BT. White matter diffusion alterations in normal women at risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2010;31:1122–1131. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song M, Yu SP. Ionic regulation of cell volume changes and cell death after ischemic stroke. Transl Stroke Res. 2014;5:17–27. doi: 10.1007/s12975-013-0314-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoffels JM, de Jonge JC, Stancic M, Nomden A, van Strien ME, Ma D, Siskova Z, Maier O, Ffrench-Constant C, Franklin RJ, Hoekstra D, Zhao C, Baron W. Fibronectin aggregation in multiple sclerosis lesions impairs remyelination. Brain. 2013;136:116–131. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su Z, Yuan Y, Chen J, Zhu Y, Qiu Y, Zhu F, Huang A, He C. Reactive astrocytes inhibit the survival and differentiation of oligodendrocyte precursor cells by secreted TNF-alpha. J Neurotrauma. 2011;28:1089–1100. doi: 10.1089/neu.2010.1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syed YA, Hand E, Mobius W, Zhao C, Hofer M, Nave KA, Kotter MR. Inhibition of CNS remyelination by the presence of semaphorin 3A. J Neurosci. 2011;31:3719–3728. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4930-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi JL, Giuliani F, Power C, Imai Y, Yong VW. Interleukin-1beta promotes oligodendrocyte death through glutamate excitotoxicity. Ann Neurol. 2003;53:588–595. doi: 10.1002/ana.10519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tekkok SB, Goldberg MP. Ampa/kainate receptor activation mediates hypoxic oligodendrocyte death and axonal injury in cerebral white matter. J Neurosci. 2001;21:4237–4248. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-12-04237.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong XP, Li XY, Zhou B, Shen W, Zhang ZJ, Xu TL, Duan S. Ca(2+) signaling evoked by activation of Na(+) channels and Na(+)/Ca(2+) exchangers is required for GABA-induced NG2 cell migration. J Cell Biol. 2009;186:113–128. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200811071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapp BD, Stys PK. Virtual hypoxia and chronic necrosis of demyelinated axons in multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:280–291. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70043-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tress O, Maglione M, May D, Pivneva T, Richter N, Seyfarth J, Binder S, Zlomuzica A, Seifert G, Theis M, Dere E, Kettenmann H, Willecke K. Panglial gap junctional communication is essential for maintenance of myelin in the CNS. J Neurosci. 2012;32:7499–7518. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0392-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valerio A, Ferrario M, Dreano M, Garotta G, Spano P, Pizzi M. Soluble interleukin-6 (IL-6) receptor/IL-6 fusion protein enhances in vitro differentiation of purified rat oligodendroglial lineage cells. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2002;21:602–615. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2002.1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Horssen J, Witte ME, Ciccarelli O. The role of mitochondria in axonal degeneration and tissue repair in MS. Mult Scler. 2012;18:1058–1067. doi: 10.1177/1352458512452924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vela JM, Molina-Holgado E, Arevalo-Martin A, Almazan G, Guaza C. Interleukin-1 regulates proliferation and differentiation of oligodendrocyte progenitor cells. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2002;20:489–502. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2002.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpe JJ. Systemic inflammation, oligodendroglial maturation, and the encephalopathy of prematurity. Ann Neurol. 2011;70:525–529. doi: 10.1002/ana.22533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wake H, Lee PR, Fields RD. Control of local protein synthesis and initial events in myelination by action potentials. Science. 2011;333:1647–1651. doi: 10.1126/science.1206998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Shi Y, Jiang X, Leak RK, Hu X, Wu Y, Pu H, Li WW, Tang B, Wang Y, Gao Y, Zheng P, Bennett MV, Chen J. HDAC inhibition prevents white matter injury by modulating microglia/macrophage polarization through the GSK3beta/PTEN/Akt axis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:2853–2858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1501441112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]