Abstract

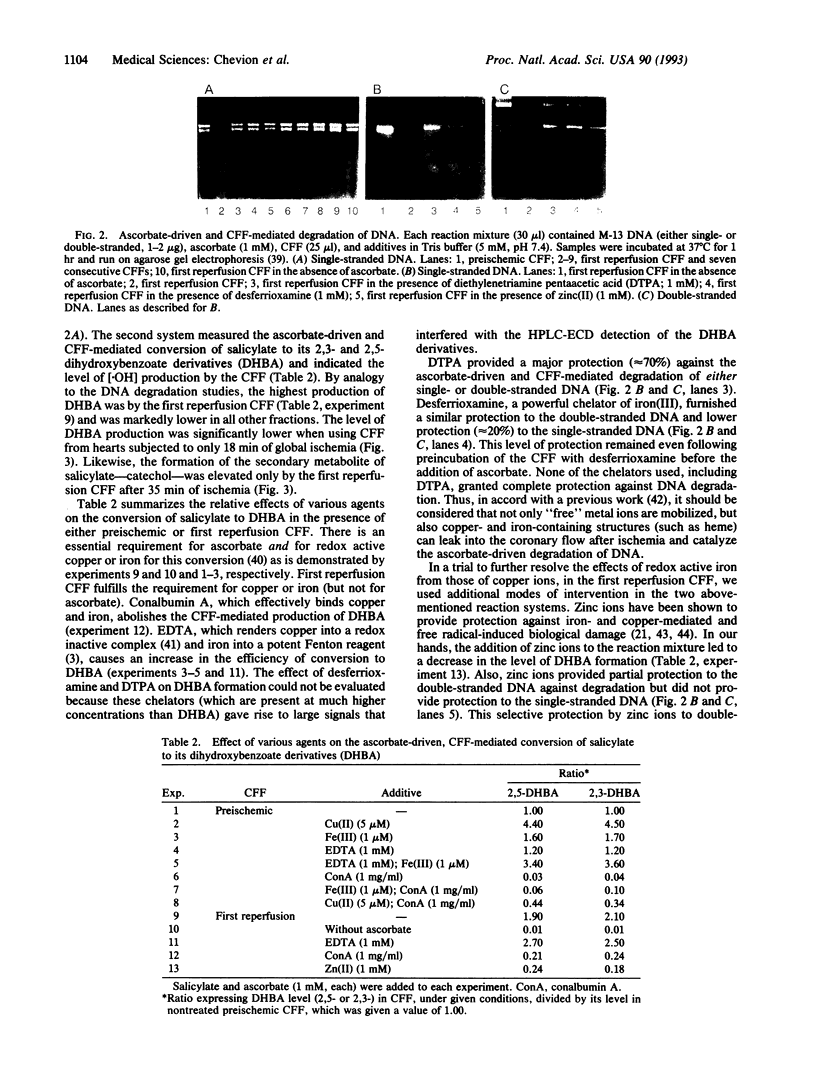

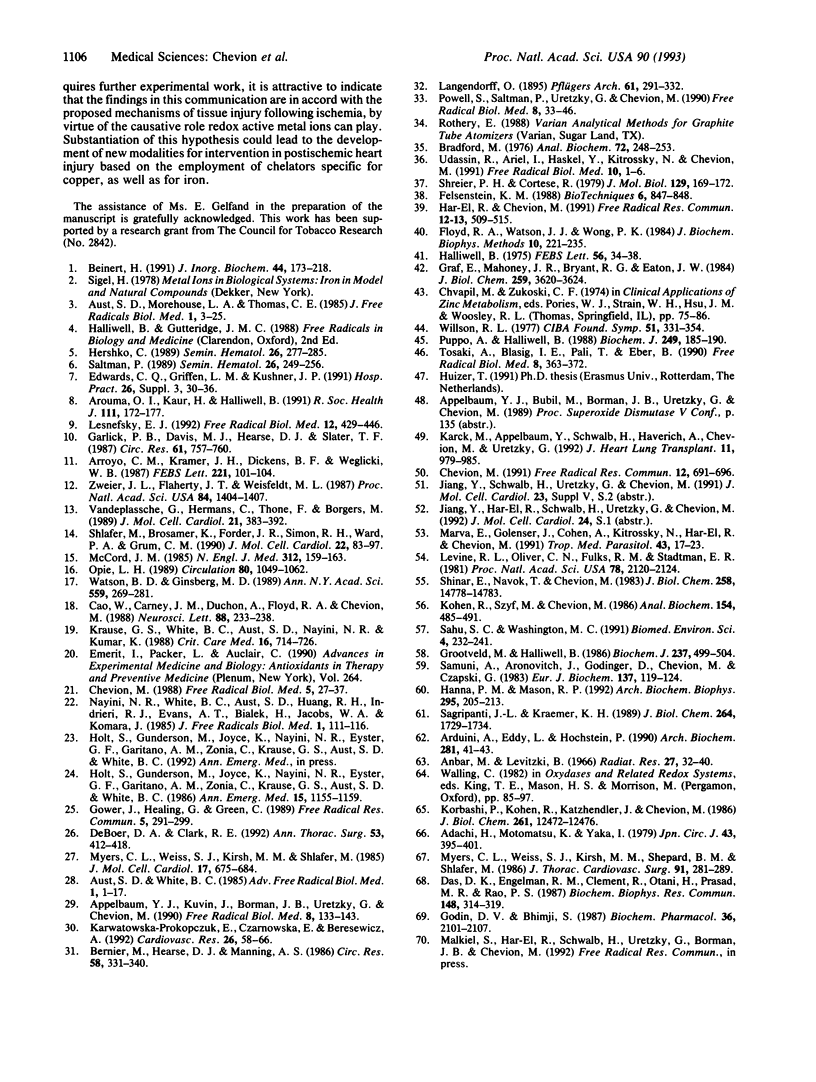

Direct evidence for substantial mobilization of copper in the coronary flow immediately following prolonged, but not short, cardiac ischemia is presented. In the first coronary flow fraction (CFF) of reperfusion (0.15 ml), after 35 min of ischemia, the level of copper (as well as of iron) was 8- to 9-fold higher than the preischemic value. The levels in subsequent CFFs decreased and reached the preischemic value, indicating that both metals appear in a burst at the resumption of coronary flow. When the first CFF was used in a reaction mixture containing ascorbate and salicylate, the latter underwent chemical hydroxylation and was converted to its dihydroxybenzoate derivatives. Likewise, this CFF promoted the ascorbate-driven DNA degradation. Subsequent 150 CFFs were serially collected and demonstrated low activities. Following 18 min of ischemia, the copper level in the first CFF of reperfusion was only 15% over the preischemic value. In contrast, the mobilization of iron into coronary flow was significant but markedly lower than after 35 min. The levels of copper and the redox activity of the first CFF correlated well with the degree of loss of cardiac function, after 18 and 35 min of ischemia, respectively. After 18 min of ischemia, cardiac function was about 50% and the damage is considered reversible, whereas after 35 min the functional loss exceeded 80% and is considered irreversible. These results are in accord with the causative role that copper and iron can play in heart injury following ischemia, by virtue of their capacity to catalyze the production of hydroxyl radicals, and could lead to the development of new modalities for intervention in tissue injury.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Adachi H., Motomatsu K., Yara I. Effect of allopurinol (zyloric) on patients undergoing open heart surgery. Jpn Circ J. 1979 May;43(5):395–401. doi: 10.1253/jcj.43.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Applebaum Y. J., Kuvin J., Borman J. B., Uretzky G., Chevion M. The protective role of neocuproine against cardiac damage in isolated perfused rat hearts. Free Radic Biol Med. 1990;8(2):133–143. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(90)90086-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arduini A., Eddy L., Hochstein P. The reduction of ferryl myoglobin by ergothioneine: a novel function for ergothioneine. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1990 Aug 15;281(1):41–43. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(90)90410-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo C. M., Kramer J. H., Dickens B. F., Weglicki W. B. Identification of free radicals in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion by spin trapping with nitrone DMPO. FEBS Lett. 1987 Aug 31;221(1):101–104. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)80360-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aruoma O. I., Kaur H., Halliwell B. Oxygen free radicals and human diseases. J R Soc Health. 1991 Oct;111(5):172–177. doi: 10.1177/146642409111100506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aust S. D., Morehouse L. A., Thomas C. E. Role of metals in oxygen radical reactions. J Free Radic Biol Med. 1985;1(1):3–25. doi: 10.1016/0748-5514(85)90025-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beinert H. Copper in biological systems. A report from the 6th Manziana Conference, September 23-27, 1990. J Inorg Biochem. 1991 Nov 15;44(3):173–218. doi: 10.1016/0162-0134(91)80054-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernier M., Hearse D. J., Manning A. S. Reperfusion-induced arrhythmias and oxygen-derived free radicals. Studies with "anti-free radical" interventions and a free radical-generating system in the isolated perfused rat heart. Circ Res. 1986 Mar;58(3):331–340. doi: 10.1161/01.res.58.3.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976 May 7;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao W., Carney J. M., Duchon A., Floyd R. A., Chevion M. Oxygen free radical involvement in ischemia and reperfusion injury to brain. Neurosci Lett. 1988 May 26;88(2):233–238. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(88)90132-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevion M. A site-specific mechanism for free radical induced biological damage: the essential role of redox-active transition metals. Free Radic Biol Med. 1988;5(1):27–37. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(88)90059-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevion M. Protection against free radical-induced and transition metal-mediated damage: the use of "pull" and "push" mechanisms. Free Radic Res Commun. 1991;12-13 Pt 2:691–696. doi: 10.3109/10715769109145848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das D. K., Engelman R. M., Clement R., Otani H., Prasad M. R., Rao P. S. Role of xanthine oxidase inhibitor as free radical scavenger: a novel mechanism of action of allopurinol and oxypurinol in myocardial salvage. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1987 Oct 14;148(1):314–319. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(87)91112-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBoer D. A., Clark R. E. Iron chelation in myocardial preservation after ischemia-reperfusion injury: the importance of pretreatment and toxicity. Ann Thorac Surg. 1992 Mar;53(3):412–418. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(92)90260-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards C. Q., Griffen L. M., Kushner J. P. Disorders of excess iron. Hosp Pract (Off Ed) 1991 Apr;26 (Suppl 3):30–36. doi: 10.1080/21548331.1991.11704282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein K. M. A modified protocol for the PZ523 spin columns: a legitimate purification alternative for plasmid DNA. Biotechniques. 1988 Oct;6(9):847–848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd R. A., Watson J. J., Wong P. K. Sensitive assay of hydroxyl free radical formation utilizing high pressure liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection of phenol and salicylate hydroxylation products. J Biochem Biophys Methods. 1984 Dec;10(3-4):221–235. doi: 10.1016/0165-022x(84)90042-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garlick P. B., Davies M. J., Hearse D. J., Slater T. F. Direct detection of free radicals in the reperfused rat heart using electron spin resonance spectroscopy. Circ Res. 1987 Nov;61(5):757–760. doi: 10.1161/01.res.61.5.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godin D. V., Bhimji S. Effects of allopurinol on myocardial ischemic injury induced by coronary artery ligation and reperfusion. Biochem Pharmacol. 1987 Jul 1;36(13):2101–2107. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(87)90137-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gower J., Healing G., Green C. Measurement by HPLC of desferrioxamine-available iron in rabbit kidneys to assess the effect of ischaemia on the distribution of iron within the total pool. Free Radic Res Commun. 1989;5(4-5):291–299. doi: 10.3109/10715768909074713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graf E., Mahoney J. R., Bryant R. G., Eaton J. W. Iron-catalyzed hydroxyl radical formation. Stringent requirement for free iron coordination site. J Biol Chem. 1984 Mar 25;259(6):3620–3624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grootveld M., Halliwell B. Aromatic hydroxylation as a potential measure of hydroxyl-radical formation in vivo. Identification of hydroxylated derivatives of salicylate in human body fluids. Biochem J. 1986 Jul 15;237(2):499–504. doi: 10.1042/bj2370499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell B. The superoxide dismutase activity of iron complexes. FEBS Lett. 1975 Aug 1;56(1):34–38. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(75)80105-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna P. M., Mason R. P. Direct evidence for inhibition of free radical formation from Cu(I) and hydrogen peroxide by glutathione and other potential ligands using the EPR spin-trapping technique. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1992 May 15;295(1):205–213. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(92)90507-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Har-El R., Chevion M. Zinc(II) protects against metal-mediated free radical induced damage: studies on single and double-strand DNA breakage. Free Radic Res Commun. 1991;12-13 Pt 2:509–515. doi: 10.3109/10715769109145824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershko C. Mechanism of iron toxicity and its possible role in red cell membrane damage. Semin Hematol. 1989 Oct;26(4):277–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt S., Gunderson M., Joyce K., Nayini N. R., Eyster G. F., Garitano A. M., Zonia C., Krause G. S., Aust S. D., White B. C. Myocardial tissue iron delocalization and evidence for lipid peroxidation after two hours of ischemia. Ann Emerg Med. 1986 Oct;15(10):1155–1159. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(86)80857-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karck M., Appelbaum Y., Schwalb H., Haverich A., Chevion M., Uretzky G. TPEN, a transition metal chelator, improves myocardial protection during prolonged ischemia. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1992 Sep-Oct;11(5):979–985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karwatowska-Prokopczuk E., Czarnowska E., Beresewicz A. Iron availability and free radical induced injury in the isolated ischaemic/reperfused rat heart. Cardiovasc Res. 1992 Jan;26(1):58–66. doi: 10.1093/cvr/26.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohen R., Szyf M., Chevion M. Quantitation of single- and double-strand DNA breaks in vitro and in vivo. Anal Biochem. 1986 May 1;154(2):485–491. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(86)90019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korbashi P., Kohen R., Katzhendler J., Chevion M. Iron mediates paraquat toxicity in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1986 Sep 25;261(27):12472–12476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause G. S., White B. C., Aust S. D., Nayini N. R., Kumar K. Brain cell death following ischemia and reperfusion: a proposed biochemical sequence. Crit Care Med. 1988 Jul;16(7):714–726. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198807000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesnefsky E. J. Reduction of infarct size by cell-permeable oxygen metabolite scavengers. Free Radic Biol Med. 1992;12(5):429–446. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(92)90092-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine R. L., Oliver C. N., Fulks R. M., Stadtman E. R. Turnover of bacterial glutamine synthetase: oxidative inactivation precedes proteolysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981 Apr;78(4):2120–2124. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.4.2120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marva E., Golenser J., Cohen A., Kitrossky N., Har-el R., Chevion M. The effects of ascorbate-induced free radicals on Plasmodium falciparum. Trop Med Parasitol. 1992 Mar;43(1):17–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCord J. M. Oxygen-derived free radicals in postischemic tissue injury. N Engl J Med. 1985 Jan 17;312(3):159–163. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198501173120305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers C. L., Weiss S. J., Kirsh M. M., Shepard B. M., Shlafer M. Effects of supplementing hypothermic crystalloid cardioplegic solution with catalase, superoxide dismutase, allopurinol, or deferoxamine on functional recovery of globally ischemic and reperfused isolated hearts. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1986 Feb;91(2):281–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers C. L., Weiss S. J., Kirsh M. M., Shlafer M. Involvement of hydrogen peroxide and hydroxyl radical in the 'oxygen paradox': reduction of creatine kinase release by catalase, allopurinol or deferoxamine, but not by superoxide dismutase. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1985 Jul;17(7):675–684. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(85)80067-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayini N. R., White B. C., Aust S. D., Huang R. R., Indrieri R. J., Evans A. T., Bialek H., Jacobs W. A., Komara J. Post resuscitation iron delocalization and malondialdehyde production in the brain following prolonged cardiac arrest. J Free Radic Biol Med. 1985;1(2):111–116. doi: 10.1016/0748-5514(85)90014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opie L. H. Reperfusion injury and its pharmacologic modification. Circulation. 1989 Oct;80(4):1049–1062. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.80.4.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell S., Saltman P., Uretzky G., Chevion M. The effect of zinc on reperfusion arrhythmias in the isolated perfused rat heart. Free Radic Biol Med. 1990;8(1):33–46. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(90)90142-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puppo A., Halliwell B. Formation of hydroxyl radicals from hydrogen peroxide in the presence of iron. Is haemoglobin a biological Fenton reagent? Biochem J. 1988 Jan 1;249(1):185–190. doi: 10.1042/bj2490185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagripanti J. L., Kraemer K. H. Site-specific oxidative DNA damage at polyguanosines produced by copper plus hydrogen peroxide. J Biol Chem. 1989 Jan 25;264(3):1729–1734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahu S. C., Washington M. C. Iron-mediated oxidative DNA damage detected by fluorometric analysis of DNA unwinding in isolated rat liver nuclei. Biomed Environ Sci. 1991 Sep;4(3):232–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saltman P. Oxidative stress: a radical view. Semin Hematol. 1989 Oct;26(4):249–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuni A., Aronovitch J., Godinger D., Chevion M., Czapski G. On the cytotoxicity of vitamin C and metal ions. A site-specific Fenton mechanism. Eur J Biochem. 1983 Dec 1;137(1-2):119–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1983.tb07804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreier P. H., Cortese R. A fast and simple method for sequencing DNA cloned in the single-stranded bacteriophage M13. J Mol Biol. 1979 Mar 25;129(1):169–172. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(79)90068-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinar E., Navok T., Chevion M. The analogous mechanisms of enzymatic inactivation induced by ascorbate and superoxide in the presence of copper. J Biol Chem. 1983 Dec 25;258(24):14778–14783. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shlafer M., Brosamer K., Forder J. R., Simon R. H., Ward P. A., Grum C. M. Cerium chloride as a histochemical marker of hydrogen peroxide in reperfused ischemic hearts. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1990 Jan;22(1):83–97. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(90)90974-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tosaki A., Blasig I. E., Pali T., Ebert B. Heart protection and radical trapping by DMPO during reperfusion in isolated working rat hearts. Free Radic Biol Med. 1990;8(4):363–372. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(90)90102-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udassin R., Ariel I., Haskel Y., Kitrossky N., Chevion M. Salicylate as an in vivo free radical trap: studies on ischemic insult to the rat intestine. Free Radic Biol Med. 1991;10(1):1–6. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(91)90014-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandeplassche G., Hermans C., Thoné F., Borgers M. Mitochondrial hydrogen peroxide generation by NADH-oxidase activity following regional myocardial ischemia in the dog. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1989 Apr;21(4):383–392. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(89)90649-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson B. D., Ginsberg M. D. Ischemic injury in the brain. Role of oxygen radical-mediated processes. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1989;559:269–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1989.tb22615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willson R. L. Iron, zinc, free radicals and oxygen in tissue disorders and cancer control. Ciba Found Symp. 1976 Dec 7;(51):331–354. doi: 10.1002/9780470720325.ch16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zweier J. L., Flaherty J. T., Weisfeldt M. L. Direct measurement of free radical generation following reperfusion of ischemic myocardium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987 Mar;84(5):1404–1407. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.5.1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]