Abstract

Background

The Mediterranean and DASH diets have been shown to slow cognitive decline, however, neither diet is specific to the nutrition literature on dementia prevention.

Methods

We devised the MIND diet score that specifically captures dietary components shown to be neuroprotective and related it to change in cognition over an average 4.7 years among 960 participants of the Memory and Aging Project.

Results

In adjusted mixed models, the MIND score was positively associated with slower decline in global cognitive score (β=0.0092; p<.0001) and with each of 5 cognitive domains. The difference in decline rates for being in the top tertile of MIND diet scores versus the lowest was equivalent to being 7.5 years younger in age.

Conclusion

The study findings suggest that the MIND diet substantially slows cognitive decline with age. Replication of these findings in a dietary intervention trial would be required to verify its relevance to brain health.

Keywords: cognition, cognitive decline, nutrition, diet, epidemiological study, aging

INTRODUCTION

Dementia is now the 6th leading cause of death in the U.S.1 and the prevention of cognitive decline, the hallmark feature of dementia, is a public health priority. It is estimated that delaying disease onset by just 5 years will reduce the cost and prevalence by half.2 Diet interventions have the potential to be effective preventive strategies. Two randomized trials of the cultural-based Mediterranean diet3 and of the blood pressure lowering DASH diet (Dietary Approach to Systolic Hypertension)4 observed protective effects on cognitive decline.5;6 We devised a new diet that is tailored to protection of the brain, called MIND (Mediterranean-DASH Diet Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay). The diet is styled after the Mediterranean and DASH diets but with modifications based on the most compelling findings in the diet-dementia field. For example, a number of prospective studies7–10 observed slower decline in cognitive abilities with high consumption of vegetables, and in the two U.S. studies, the greatest protection was from green leafy vegetables.7;8 Further, all of these studies found no association of overall fruit consumption with cognitive decline. However, animal models11 and one large prospective cohort study12 indicate that at least one particular type of fruit – berries - may protect the brain against cognitive loss. Thus, among the unique components of the MIND diet score are that it specifies consumption of green leafy vegetables and berries but does not score other types of fruit. In this study, we related the MIND diet score to cognitive decline in the Memory and Aging Project (MAP) and compared the estimated effects to those of the Mediterranean and DASH diets, dietary patterns that we previously reported were protective against cognitive decline among the MAP study participants.13

METHODS

Study Population

The analytic sample is drawn from the Rush Memory and Aging Project (MAP), a study of residents of more than 40 retirement communities and senior public housing units in the Chicago area. Details of the MAP study were published previously.14 Briefly, the ongoing open cohort study began in 1997 and includes annual clinical neurological examinations. At enrollment, participants are free of known dementia15;16 and agree to annual clinical evaluation and organ donation after death. We excluded persons with dementia based on accepted clinical criteria as previously described.15,16 Participants meeting criteria for mild cognitive impairment17 (n=220) were not excluded except in secondary analyses. From February 2004- 2013, the MAP study participants were invited to complete food frequency questionnaires at the time of their annual clinical evaluations. During that period, a total of 1,545 older persons had enrolled in the MAP study, 90 died and 149 withdrew before the diet study began, leaving 1306 participants eligible for these analyses. Of these, 1068 completed the dietary questionnaires of which 960 survived and had at least two cognitive assessments for the analyses of change. The analytic sample was 95% white and 98.5% non-Hispanic. The Institutional Review Board of Rush University Medical Center approved the study, and all participants gave written informed consent.

Cognitive Assessments

Each participant underwent annual structured clinical evaluations including cognitive testing. Technicians, trained and certified according to standardized neuropsychological testing methods, administered 21 tests, 19 of which summarized cognition in five cognitive domains (episodic memory, working memory, semantic memory, visuospatial ability, and perceptual speed) as described previously.18 Composite scores were computed for each cognitive domain and for a global measure of all 19 tests. Raw scores for each test were standardized using the mean and standard deviation from the baseline population scores, and the standardized scores averaged. The number of annual cognitive assessments analyzed for participants ranged from 2 to 10 with 52% of sample participants having 5 or more cognitive assessments.

Diet Assessment

FFQs were collected at each annual clinical evaluation. For these prospective analyses of the estimated dietary effects on cognitive change, we used the first obtained FFQ to relate dietary scores to cognitive change from that point forward. Longitudinal analyses of change in MIND diet score using all available FFQs in a linear mixed model indicated a very small but statistically significant decrease in MIND score of −0.026 (p=0.02) compared to the intercept MIND diet score of 7.37.

Diet scores were computed from responses to a modified Harvard semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) that was validated for use in older Chicago community residents.19 The FFQ ascertains usual frequency of intake over the previous 12 months of 144 food items. For some food items, natural portion sizes (e.g. 1 banana) were used to determine serving sizes and calorie and nutrient levels. Serving sizes for other food items were based on sex-specific mean portion sizes reported by the oldest men and women of national surveys.

MIND Diet Score

The MIND diet score was developed in three stages: 1) determination of dietary components of the Mediterranean and DASH diets including the foods and nutrients shown to be important to incident dementia and cognitive decline through detailed reviews of the literature,20–22 2) selection of FFQ items that were relevant to each MIND diet component, and 3) determination of daily servings to be assigned to component scores guided by published studies on diet and dementia. Among the MIND diet components are 10 brain healthy food groups (green leafy vegetables, other vegetables, nuts, berries, beans, whole grains, seafood, poultry, olive oil and wine) and 5 unhealthy food groups (red meats, butter and stick margarine, cheese, pastries and sweets, and fried/fast food). Olive oil consumption was scored 1 if identified by the participant as the primary oil usually used at home and 0 otherwise. For all other diet score components we summed the frequency of consumption of each food item portion associated with that component and then assigned a concordance score of 0, 0.5, or 1. (Table 1) The total MIND diet score was computed by summing over all 15 of the component scores.

Table 1.

MIND diet component servings and scoring

| 0 | 0.5 | 1 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Green Leafy Vegetablesa | ≤2 servings/wk | > 2 to <6/wk | ≥6 servings/wk |

| Other Vegetablesb | <5 serving/wk | 5 – <7 wk | ≥1 serving/day |

| Berriesc | <1 serving/wk | 1 /wk | ≥2 servings/wk |

| Nuts | <1/mo | 1/mo – <5/wk | ≥5 servings/wk |

| Olive Oil | Not primary oil | Primary oil used | |

| Butter, Margarine | >2 T/d | 1–2 /d | <1 T/d |

| Cheese | 7+ servings/wk | 1–6 /wk | < 1 serving/wk |

| Whole Grains | <1 serving/d | 1–2 /d | ≥3 servings/d |

| Fish (not fried)d | Rarely | 1–3 /mo | ≥1 meals/wk |

| Beanse | <1 meal/wk | 1–3/wk | >3 meals/wk |

| Poultry (not fried)f | <1 meal/wk | 1 /wk | ≥2 meals/wk |

| Red Meat and productsg | 7+ meals/wk | 4–6 /wk | < 4 meals/wk |

| Fast Fried Foodsh | 4+ times/wk | 1–3 /wk | <1 time/wk |

| Pastries & Sweetsi | 7+ servings/wk | 5 −6 /wk | <5 servings/wk |

| Wine | >1 glass/d or never | 1/mo – 6/wk | 1 glass/d |

| TOTAL SCORE | 15 | ||

kale, collards, greens; spinach; lettuce/tossed salad

green/red peppers, squash, cooked carrots, raw carrots, broccoli, celery, potatoes, peas or lima beans, potatoes, tomatoes, tomato sauce, string beans, beets, corn, zucchini/summer squash/eggplant, coleslaw, potato salad

strawberries

beans, lentils, soybeans)

tuna sandwich, fresh fish as main dish; not fried fish cakes, sticks, or sandwiches

chicken or turkey sandwich, chicken or turkey as main dish and never eat fried at home or away from home

cheeseburger, hamburger, beef tacos/burritos, hot dogs/sausages, roast beef or ham sandwich, salami, bologna, or other deli meat sandwich, beef (steak, roast) or lamb as main dish, pork or ham as main dish, meatballs or meatloaf

How often do you eat fried food away from home (like French fries, chicken nuggets)?

biscuit/roll, poptarts, cake, snack cakes/twinkies, Danish/sweetrolls/pastry, donuts, cookies, brownies, pie, candy bars, other candy, ice cream, pudding, milkshakes/frappes

DASH and Mediterranean Diet Scores

We used the DASH diet scoring of the ENCORE trial23 in which 10 dietary components were each scored 0, 0.5, or 1 and summed for a total score ranging from 0 (lowest) to 10 (highest) diet concordance. The Mediterranean Diet Score was that described by Panagiotakos et al.3 that includes 11 dietary components each scored 0 to 5 that are summed for a total score ranging from 0 to 55 (highest dietary concordance). We used serving quantities specific to the traditional Greek Mediterranean diet3 to score concordance in contrast to the use of sex-specific within population median servings employed by other studies so that the scoring metric aligned with the actual Mediterranean diet.

Covariates

Total energy intake was computed based on responses of frequency of consumption of the FFQ food items. Non-dietary variables were obtained from structured interview questions and measurements at the participants’ annual clinical evaluations. Age (in years) was computed from self-reported birth date and date of the first cognitive assessment in this analysis. Education was based on self-reported years of regular schooling. Apolipoprotein E genotyping was performed using high throughput sequencing as previously described.24 Smoking history was categorized as never, past and current smoker. All other covariates were based on data collected at the time of each cognitive assessment and were modeled as time-varying covariates to represent updated information from participants’ previous evaluations. A variable for frequency of participation in cognitively stimulating activities was computed as the average frequency rating, based on a 5-point scale, of different activities (e.g. reading, playing games, writing letters, visiting the library).25 Hours per week of physical activity was computed based on the sum of self-reported minutes spent over the previous two weeks on five activities (walking for exercise, yard work, calisthenics, biking, and water exercise).26 Number of depressive symptoms was assessed by a modified 10-item version of the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale27 that has been related to incident dementia. Body mass index (weight in kg/height in m2) was computed from measured weight and height and modeled as two indicator variables, BMI≤20 and BMI ≥30. Hypertension history was determined by self-reported medical diagnosis, measured blood pressure (average of 2 measurements ≥160 mmHg systolic or ≥90 mmHg diastolic) or current use of hypertensive medications. Myocardial infarction history was based on self-reported medical diagnosis or interviewer recorded use of cardiac glycosides (e.g. lanoxin, digitoxin). Diabetes history was determined by self-reported medical diagnosis or current use of medications. Medication use was based on interviewer inspection. Clinical diagnosis of stroke was based on clinician review of self-reported history, neurological examination and cognitive testing history.28

Statistical Methods

We used separate linear mixed models with random effects in SAS© to examine the relations of the MIND diet score to change in the global cognitive score and in each cognitive domain score. The basic-adjusted model included terms for age, sex, education, APOE-ε4, smoking history, physical activity, participation in cognitive activities, total energy intake, MIND diet score, a variable for time, and multiplicative terms between time and each model covariate, the latter providing the covariate effect on cognitive decline. For all analyses, we investigated both linear (MIND diet score modeled as a continuous term) and non-linear associations (MIND diet score modeled in tertiles) with the cognitive scores. Because the study results were identical for the two sets of models, we report the effect estimates for the continuous linear term in tables and text and the tertile estimates in Figure 1. Non-static covariates (e.g. cognitive and physical activities, BMI, depressive symptoms and cardiovascular conditions) were modeled as time-varying except when they were analyzed as potential effect modifiers in which case only the baseline measure for that covariate was modeled. Tests for statistical interaction by potential effect modifiers were computed in the basic-adjusted model by modeling 2-way and 3-way multiplicative terms between MIND diet score, time, and the effect modifier, with the 3-way multiplicative term test for interaction set at p≤0.05. We compared the relative effects of the MIND, Mediterranean and DASH diet scores on cognitive decline by computing standardized β coefficients ( β to 4 decimal places /standard error) for each diet score based on the parameter estimates of the basic model. We then performed formal statistical tests using Meng et al.’s 29 revision of Hotelling’s 30 procedure for comparing two non-independent correlation coefficients, in this case, the correlations between the diet scores and cognitive change from the basic model. To provide an estimate of the equivalent age difference in years to the difference in decline rates for tertiles 3 and 1 of the MIND diet score, we computed the ratio of the beta coefficients [β (time*age) / β (time*tertile 3 MIND score) in the basic-adjusted model.

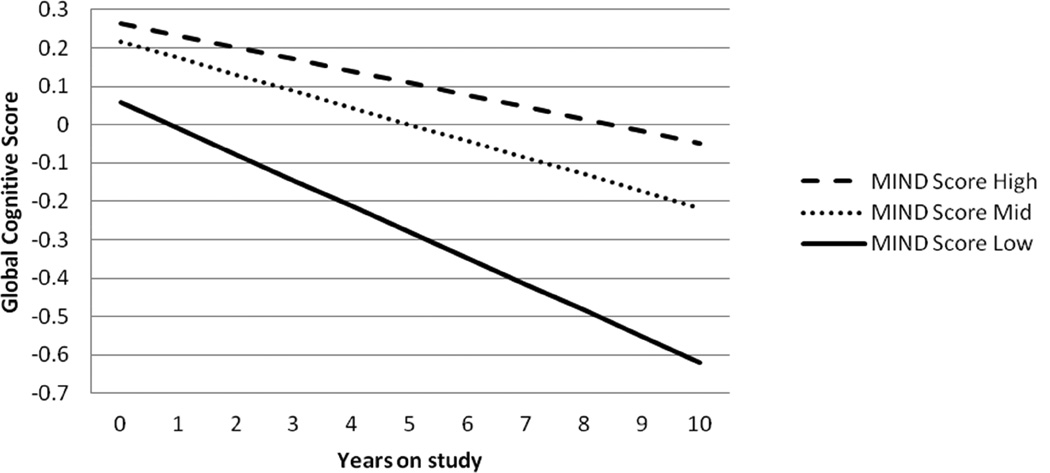

Figure 1.

Rates of change in global cognitive score over 10 years for MAP participants with MIND diet scores in the highest tertile of scores (- - -; median 9.5, range 8.5–12.5), the second tertile of scores (…; median 7.5, range 7.0–8.0), and the lowest tertile of scores ( ; median 6, range 2.5–6.5). The rates of change were based on the mixed model with MIND diet score modeled as two indicator variables for tertile 2 and tertile 3 (tertile 1, the referent) and adjusted for age, sex, education, smoking, physical activity, participation in cognitively stimulating activities, and total energy intake. For tertile 3: β=0.0366, standard error=0.0101, p=0.003 and for tertile 2: β=0.0243, standard error=0.0099, p=0.01.

; median 6, range 2.5–6.5). The rates of change were based on the mixed model with MIND diet score modeled as two indicator variables for tertile 2 and tertile 3 (tertile 1, the referent) and adjusted for age, sex, education, smoking, physical activity, participation in cognitively stimulating activities, and total energy intake. For tertile 3: β=0.0366, standard error=0.0101, p=0.003 and for tertile 2: β=0.0243, standard error=0.0099, p=0.01.

RESULTS

The analytic sample was on average 81.4 (± 7.2) years of age, primarily female (75%) and with a mean educational level of 14.9 (±2.9) years, and was demographically comparable to the entire MAP cohort of 1,545 participants (mean age, 80.1 years; 73% female; mean education, 14.4 years). Computed MIND scores from food frequency data on MAP study participants averaged 7.4 (range: 2.5–12.5). MIND diet scores were positively correlated with both the Mediterranean (r=0.62) and the DASH (r=0.50) diet scores. MAP participants with the highest MIND diet scores tended to have a more favorable risk profile for preserving cognitive abilities including higher education, greater participation in cognitive and physical activities and lower prevalence of cardiovascular conditions. (Table 2)

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics * of analyzed MAP participants according to tertile of MIND diet score

| Characteristic | MIND Diet Score Tertile | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Tertile 1 | Tertile 2 | Tertile 3 | |

| Age, mean years | 960 | 81.9 | 81.7 | 80.5 |

| Male, percent | 960 | 28 | 26 | 23 |

| APOE-ε4, percent | 823 | 22 | 26 | 21 |

| Education, mean years | 960 | 14.3 | 15.1 | 15.6 |

| Cognitive Activities, mean | 959 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 3.4 |

| Total Energy Intake, mean kcal | 960 | 1665 | 1788 | 1794 |

| Smoking, percent never | 960 | 40 | 38 | 42 |

| Physical Activity, mean hours/week | 958 | 2.5 | 3.4 | 4.3 |

| Depressive Symptoms, mean number | 959 | 1.4 | 0.9 | 0.9 |

| BMI, mean | 927 | 27.5 | 27.1 | 26.7 |

| Hypertension, percent | 954 | 79 | 76 | 72 |

| Diabetes, percent | 960 | 24 | 20 | 17 |

| Heart Disease History, percent | 959 | 18 | 12 | 18 |

| Clinical Stroke History, percent | 870 | 11 | 7 | 9 |

Characteristics were standardized by age in 5-year categories

The overall rate of change in cognitive score was a decline of 0.08 standardized score units (SU) per year. In mixed models adjusted for age, sex, education, total energy intake APOE-ε4, smoking history, physical activity and participation in cognitive activities, the MIND diet score was positively and statistically significantly associated with slower rate of cognitive decline. (Table 3) Compared to the decline rate of participants in the lowest tertile of scores, the rate for participants in the highest tertile was substantially slower. (Figure 1) The difference in rates was the equivalent of being 7.5 years younger in age. The MIND diet score was statistically significantly associated with each cognitive domain, particularly for episodic memory, semantic memory and perceptual speed. (Table 3)

Table 3.

Estimated effects (β)* of the MIND diet score on the rate of change in global cognitive score and change in five cognitive domains among MAP participants over an average 4.7 years of follow-up in adjusted* mixed models

| Global | Episodica | Semanticb | Perceptualc | Perceptuald | Workinge | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognition | Memory | Memory | Organization | Speed | Memory | ||

| Age-Adjusted | n** | 960 | 949 | 945 | 932 | 934 | 957 |

| β | 0.0090 | 0.0079 | 0.0069 | 0.0057 | 0.0088 | 0.0049 | |

| Standard Error | (0.0023) | (0.0027) | (0.0026) | (0.0025) | (0.0024) | (0.0024) | |

| P-Value | 0.0001 | 0.003 | 0.007 | 0.02 | 0.0002 | 0.04 | |

| Basic† | n** | 818 | 808 | 804 | 793 | 794 | 816 |

| β | 0.0095 | 0.0080 | 0.0105 | 0.0077 | 0.0084 | 0.0050 | |

| Standard Error | (0.0023) | (0.0028) | (0.0027) | (0.0025) | (0.0024) | (0.0024) | |

| P-Value | <0.0001 | 0.004 | 0.0001 | 0.002 | 0.0003 | 0.04 | |

| Basic + | |||||||

| Cardiovascular | |||||||

| Conditions ± | n** | 860 | 850 | 846 | 835 | 836 | 858 |

| β | 0.0106 | 0.0090 | 0.0113 | 0.0077 | 0.0097 | 0.0060 | |

| Standard Error | (0.0023) | (0.0028) | (0.0027) | (0.0025) | (0.0023) | (0.0024) | |

| P-Value | <0.0001 | 0.001 | <0.0001 | 0.002 | <0.0001 | 0.01 | |

β=beta coefficient from the model for the interaction term between MIND diet score and time

n=total number of participants with complete data for model

Basic model includes age at the first cognitive assessment, Mind diet score, sex, education, participation in cognitive activities, APOE-ε4 (any ε4 allele), smoking history (current, past, never), physical activity hours per week, total energy intake, time and interaction terms between time and each model covariate

Basic model plus history of stroke, myocardial infarction, diabetes, hypertension and interaction terms between each covariate and time

Composite score of the following 7 instruments: Immediate memory test and delayed memory test from Story A Logical Memory subset of the Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised; immediate word recall and delayed word recall of the CERAD Word List Recall; CERAD Word list Recognition; and immediate memory test and delayed memory test of the East Boston Story.

Composite score of the following 3 instruments: Verbal fluency from CERAD; 15 item version of the Boston Naming Test; and 15-item reading test

Composite score of the 15-item version of Judgment of Line Orientation and the 16-item version of Standard Progressive Matrice

Composite score of the following 4 measure: Oral version of the Symbol Digit Modalities Test; Number Comparison; and, 2 indices from a modified version of the Stroop Neuropsychological Screening test

Composite score of the following 3 instruments: Digit Span subtests-forward of the Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised; Digit Span subtests-backward of the Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised; and Digit Ordering

The Mediterranean and DASH diets have demonstrated effects on the reduction of cardiovascular conditions and risk factors31–34 which raises the possibility that the MIND diet association with cognitive decline may be through its effects on cardiovascular disease. To investigate potential mediation by these factors we reanalyzed the basic model for the global cognitive score and each cognitive domain score with the inclusion of terms for hypertension, stroke, myocardial infarction, and diabetes, however, the effect estimates did not change. (Table 3)

Depression and weight have complex relations with dementia; they are known both as risk factors (depression, obesity) and as outcomes of the disease (depressive symptoms, weight loss). Both factors are also affected by diet quality. Therefore, we examined in the basic model what impact additional control for these variables might have on the observed association between the MIND diet score and cognitive decline but these adjustments also did not change the results for any of the cognitive measures (e.g. for global cognitive function β=0.00922, SE=0.0022, p<0.0001).

We also investigated potential modifications in the estimated effect of the MIND diet score on cognitive decline by age, sex, APOE-ε4, education, physical activity, low weight (BMI≤20), obese (BMI≥30), and each of the cardiovascular-related conditions (hypertension, myocardial infarction, stroke, diabetes). However, there was no statistical evidence that the diet effect on the global or individual domain cognitive scores differed by level or presence of any of these risk factors. (Data not shown)

To examine whether the observed MIND diet –cognitive decline relation may be due to dementia effects on dietary behaviors or on reporting accuracy, we reanalyzed the data after eliminating 220 participants who had mild cognitive impairment at the baseline; the resulting decline rate for higher MIND diet score (β=0.0104, p<.00001) was even more protective, by 9.5%, compared to that of the entire sample (β=0.0095).

We also investigated the potential effects of dietary changes over time on the observed associations of baseline MIND diet score with cognitive change. We reanalyzed the data after excluding 144 participants whose MIND diet scores either improved (top 10%) or decreased (bottom 10%) over the study period. The protective estimates of effect of the MIND diet score on change in global cognitive score increased considerably (β=0.0120, p<0.00001) in the basic-adjusted model. The estimated effects of the MIND diet on the individual cognitive domains also increased by 30–78% with the exception of visuospatial ability, which had little change (β=0.0072, p=0.02).

In a previous study of the MAP participants, we observed protective relations of both the MedDiet and DASH diet scores to cognitive decline. A comparison of these diet components and scores is provided in eTable 1. We analyzed the data for these two diet scores in separate basic-adjusted models of the global cognitive scores and compared the standardized regression coefficients for all three diet scores. The MIND diet score was more predictive of cognitive decline than either of the other diet scores; the standardized β coefficients of the estimated diet effects were 4.39 for MIND, 2.46 for the MedDiet and 2.60 for DASH. The correlation between the MIND score with cognitive change was statistically significantly higher compared with that for either the MedDiet (p=0.02) or the DASH (p=0.03).

DISCUSSION

In this community-based study of older persons, we investigated the relation of diet to change in cognitive function using an á priori-defined diet composition score (MIND) based on the foods and nutrients shown to be protective for dementia. Higher MIND diet score was associated with slower decline in cognitive abilities. The rate reduction for persons in the highest tertile of diet scores compared with the lowest tertile was the equivalent of being 7.5 years younger in age. Strong associations of the MIND diet were observed with the global cognitive measure as well as with each of five cognitive domains. The strength of the estimated effect was virtually unchanged after statistical control for many of the important confounders, including physical activity and education as well as with the exclusion of individuals with the lowest baseline cognitive scores.

The MIND diet was based on the dietary components of the Mediterranean and DASH diets, including emphasis on natural plant-based foods and limited intake of animal and high saturated fat foods. However, the MIND diet uniquely specifies consumption of berries and green leafy vegetables, and does not specify high fruit consumption (both DASH and Mediterranean), high dairy (DASH), high potato consumption or greater than 1 fish meal per week (Mediterranean). The MIND modifications highlight the foods and nutrients shown through the scientific literature to be associated with dementia prevention.21;36;37 A number of prospective cohort studies found that higher consumption of vegetables was associated with slower cognitive decline7–10 with the strongest relations observed for green leafy vegetables.7;8 Green leafy vegetables are sources of folate, vitamin E, carotenoids and flavonoids, nutrients that have been related to lower risk of dementia and cognitive decline. There is a vast literature demonstrating neuroprotection of the brain by vitamin E, rich sources of which are vegetable oils, nuts, and whole grains.21 Dietary intakes of berries were demonstrated to improve memory and learning in animal models11 and to slow cognitive decline in the Nurses’ Health Study.12 However, the prospective epidemiological studies of cognitive decline or dementia do not observe protective benefit from the consumption of fruits in general.7–10 These dietary components have been demonstrated to protect the brain through their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties (vitamin E),38;39 and inhibition of β-amyloid deposition (vitamin E, folate, flavonoids, carotenoids)39–43 and neurotoxic death (vitamin E, flavonoids).44 Studies of fish consumption observed lower risk of dementia with just 1 fish meal a week with no additional benefit evident for higher servings per week.45–47 Thus, the highest possible score for this component of the MIND diet score is attributed to one or more servings per week. Mediterranean diet interventions supplemented with either nuts or extra-virgin olive oil were effective in maintaining higher cognitive scores compared to a low-fat diet in a sub-study of PREDIMED,6 a randomized trial designed to test diet effects on cardiovascular outcomes among Spaniards at high cardiovascular risk. The MIND diet components directed to limiting intake of unhealthy foods for the brain target foods that contribute to saturated and trans fat intakes, such as red meat and meat products, butter and stick margarine, whole fat cheese, pastries and sweets and fried/fast foods. Fat composition that is higher in saturated and trans fats and lower in polyunsaturated and monounsaturated fats lead to blood brain barrier dysfunction and increased Aβ aggregation.22 Fish are a rich source of long-chain n-3 fatty acids which have been shown to reduce Aβ formation and oxidative damage, and to increase synaptic proteins and dendritic spine density.48;49

The study findings are supported by a number of strengths including the prospective study design with up to 10 years of follow-up, annual assessment of cognitive function using a battery of standardized tests, comprehensive assessment of diet using a validated questionnaire, and statistical control of the important confounding factors. Another important strength is that the MIND diet score was devised based on expansive reviews of studies relating diet to brain function.20–22;36 None of the studies included in these reviews were conducted in the MAP study cohort. The fact that the food components were selected independently of the best statistical prediction of the outcome in the MAP study population lends validity to the MIND diet as a preventive measure for cognitive decline with aging.

A limitation of the study is that the dietary questionnaire had few questions to measure some of the dietary components and limited information on frequency of consumption. For example, a single item each provided information on consumption of nuts, berries (strawberries), beans, and olive oil. However, this imprecision in the measurement of the MIND score would tend to underestimate the diet effect on cognitive decline. Another limitation is the self-report of diet which some studies suggest can lead to biased reporting in overweight50 and cognitively impaired51 adults. Concern that biased diet reporting could explain the findings is mitigated by the fact that statistical control for factors like obesity, education, age, and physical activity had no impact on the estimated MIND diet effect and the association remained strong in analyses that omitted the participants with MCI and whose diet scores changed over the study period. Further we observed no modification in the effect by level of these potential confounders.

The primary limitation of the study is that it is observational and thus the findings cannot be interpreted as a cause and effect relation. Replication of the findings in other cohort studies is important for confirmation of the association, however, a diet intervention trial is required to establish a causal relation between diet and prevention of cognitive decline. Further, the findings were based on an old, largely non-Hispanic white study population and cannot be generalized to younger populations or different racial/ethnic groups.

The MIND diet is a refinement of the extensively studied cardiovascular diets, the Mediterranean and DASH diets, with modifications based on the scientific literature relevant to nutrition and the brain. This literature is underdeveloped and therefore, modifications to the MIND diet score would be expected as new scientific advances are made.

Supplementary Material

Systematic Review

We performed extensive reviews of the literature on nutrition and neurodegenerative diseases and cognitive decline to devise a brain healthy diet called MIND. The reviews included animal models, prospective epidemiological studies and randomized trials of nutrients, individual foods, and whole diets.

Interpretation

The MIND diet builds on previously tested diets, particularly the Mediterranean and DASH diets, for prevention of dementia outcomes by incorporating specific foods and intake levels that reflect the current state of knowledge in the field.

Future Directions

In the current study, the MIND diet was strongly associated with slower cognitive decline and had greater estimated effects than either the Mediterranean diet or the DASH diet. Future studies should evaluate and confirm the preventive relation of the MIND diet to cognitive change in other populations. As the field develops, the MIND dietary components should be modified to reflect new knowledge on nutrition and the brain.

Acknowledgements

The study was funded by grants (R01AG031553 and R01AG17917) from the National Institute on Aging.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no relevant disclosures of potential conflicts of interest.

Reference List

- 1.2013 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. 2. Vol. 9. Alzheimer’s Association; 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Changing the Trajectory of Alzheimer’s Disease: How a Treatment by 2025 Saves Lives and Dollars. Alzheimer’s Association; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Panagiotakos DB, Pitsavos C, Arvaniti F, Stefanadis C. Adherence to the Mediterranean food pattern predicts the prevalence of hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes and obesity, among healthy adults; the accuracy of the MedDietScore. Prev Med. 2007;44:335–340. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sacks FM, Appel LJ, Moore TJ, et al. A dietary approach to prevent hypertension: a review of the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) Study. Clin Cardiol. 1999;22:III6–III10. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960221503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith PJ, Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, et al. Effects of the dietary approaches to stop hypertension diet, exercise, and caloric restriction on neurocognition in overweight adults with high blood pressure. Hypertension. 2010;55:1331–1338. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.146795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martinez-Lapiscina EH, Clavero P, Toledo E, et al. Mediterranean diet improves cognition: the PREDIMED-NAVARRA randomised trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2013;84:1318–1325. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2012-304792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morris MC, Evans DA, Tangney CC, Bienias JL, Wilson RS. Associations of vegetable and fruit consumption with age-related cognitive change. Neurology. 2006;67:1370–1376. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000240224.38978.d8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kang JH, Ascherio A, Grodstein F. Fruit and vegetable consumption and cognitive decline in aging women. Ann Neurol. 2005;57:713–720. doi: 10.1002/ana.20476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nooyens AC, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, van Boxtel MP, van Gelder BM, Verhagen H, Verschuren WM. Fruit and vegetable intake and cognitive decline in middle-aged men and women: the Doetinchem Cohort Study. Br J Nutr. 2011;106:752–761. doi: 10.1017/S0007114511001024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen X, Huang Y, Cheng HG. Lower intake of vegetables and legumes associated with cognitive decline among illiterate elderly Chinese: a 3-year cohort study. J Nutr Health Aging. 2012;16:549–552. doi: 10.1007/s12603-012-0023-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Willis LM, Shukitt-Hale B, Joseph JA. Recent advances in berry supplementation and age-related cognitive decline. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2009;12:91–94. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e32831b9c6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Devore EE, Kang JH, Breteler MM, Grodstein F. Dietary intakes of berries and flavonoids in relation to cognitive decline. Ann Neurol. 2012;72:135–143. doi: 10.1002/ana.23594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tangney CC, Li H, Wang Y, et al. Relation of DASH- and Mediterranean-like dietary patterns on cognitive decline in older persons. Neurology. 2014;83:1410–1416. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Buchman AS, Barnes LL, Boyle PA, Wilson RS. Overview and findings from the rush memory and aging project. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2012;9:646–663. doi: 10.2174/156720512801322663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Aggarwal NT, et al. Decision rules guiding the clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease in two community-based cohort studies compared to standard practice in a clinic-based cohort study. Neuroepidemiology. 2006;27:169–176. doi: 10.1159/000096129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bennett DA, Wilson RS, Schneider JA, et al. Natural history of mild cognitive impairment in older persons. Neurology. 2002;59:198–205. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.2.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilson RS, Arnold SE, Tang Y, Bennett DA. Odor identification and decline in different cognitive domains in old age. Neuroepidemiology. 2006;26:61–67. doi: 10.1159/000090250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morris MC, Tangney CC, Bienias JL, Evans DA, Wilson RS. Validity and reproducibility of a food frequency questionnaire by cognition in an older biracial sample. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158:1213–1217. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barnes JL, Tian M, Edens NK, Morris MC. Consideration of Nutrient Levels in Studies of Cognitive Decline: A Review. Nutr Rev. 2014 doi: 10.1111/nure.12144. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morris MC. Nutritional determinants of cognitive aging and dementia. Proc Nutr Soc. 2012;71:1–13. doi: 10.1017/S0029665111003296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morris MC, Tangney CC. Dietary fat composition and dementia risk. Neurobiol Aging. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.03.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Epstein DE, Sherwood A, Smith PJ, et al. Determinants and consequences of adherence to the dietary approaches to stop hypertension diet in African-American and white adults with high blood pressure: results from the ENCORE trial. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112:1763–1773. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buchman AS, Boyle PA, Wilson RS, Beck TL, Kelly JF, Bennett DA. Apolipoprotein E e4 allele is associated with more rapid motor decline in older persons. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23:63–69. doi: 10.1097/wad.0b013e31818877b5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilson RS, Barnes LL, Krueger KR, Hoganson G, Bienias JL, Bennett DA. Early and late life cognitive activity and cognitive systems in old age. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2005;11:400–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buchman AS, Boyle PA, Wilson RS, Bienias JL, Bennett DA. Physical activity and motor decline in older persons. Muscle Nerve. 2007;35:354–362. doi: 10.1002/mus.20702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kohout FJ, Berkman LF, Evans DA, Cornoni-Huntley J. Two shorter forms of the CES-D depression symptoms index. J Aging Health. 1993;5:179–193. doi: 10.1177/089826439300500202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bennett DA. Secular trends in stroke incidence and survival, and the occurrence of dementia. Stroke. 2006;37:1144–1145. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000219643.43966.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meng XL, Rosenthal R, Rubin DB. Comparison of Correlated Correlation Coefficients. Psychol Bull. 1992;111:172–175. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hotelling H. The selection of variates for use in prediction, with some comments in the general problem of nuisance parameters. Ann Mathematical Statistics. 1940;11:271–283. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Appel LJ, Moore TJ, Obarzanek , et al. A clinical trial of the effects of dietary patterns on blood pressure. DASH Collaborative Research Group. New England Journal of Medicine. 1997;336:1117–1124. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704173361601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salas-Salvado J, Bullo M, Babio N, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with the Mediterranean diet: results of the PREDIMED-Reus nutrition intervention randomized trial. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:14–19. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvado J, et al. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1279–1290. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1806491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Toledo E, Hu FB, Estruch R, et al. Effect of the Mediterranean diet on blood pressure in the PREDIMED trial: results from a randomized controlled trial. BMC Med. 2013;11:207. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tangney CC, Li H, Barnes LL, Schneider JA, Bennett DA, Morris MC. Accordance to Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) is associated with slower cognitive decline. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2013;9:605–606. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gillette GS, bellan Van KG, Andrieu S, et al. IANA task force on nutrition and cognitive decline with aging. J Nutr Health Aging. 2007;11:132–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morris MC, Tangney CC. Dietary Fat Composition and Dementia Risk. Neurobiology of Aging. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.03.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yamada K, Tanaka T, Han D, Senzaki K, Kameyama T, Nabeshima T. Protective effects of idebenone and alpha-tocopherol on beta-amyloid-(1–42)-induced learning and memory deficits in rats: implication of oxidative stress in beta-amyloid-induced neurotoxicity in vivo. European Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;11:83–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jiang Q, Ames BN, Jiang Q, et al. Gamma-tocopherol, but not alpha-tocopherol, decreases proinflammatory eicosanoids and inflammation damage in rats. FASEB Journal. 2003;17:816–822. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0877com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chan A, Shea TB. Folate deprivation increases presenilin expression, gamma-secretase activity, and Abeta levels in murine brain: potentiation by ApoE deficiency and alleviation by dietary S-adenosyl methionine. J Neurochem. 2007;102:753–760. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nishida Y, Ito S, Ohtsuki S, et al. Depletion of vitamin E increases amyloid beta accumulation by decreasing its clearances from brain and blood in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:33400–33408. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.054056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Katayama S, Ogawa H, Nakamura S. Apricot carotenoids possess potent anti-amyloidogenic activity in vitro. J Agric Food Chem. 2011;59:12691–12696. doi: 10.1021/jf203654c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Obulesu M, Dowlathabad MR, Bramhachari PV. Carotenoids and Alzheimer’s disease: an insight into therapeutic role of retinoids in animal models. Neurochem Int. 2011;59:535–541. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jalsrai A, Numakawa T, Ooshima Y, Adachi N, Kunugi H. Phosphatase-mediated intracellular signaling contributes to neuroprotection by flavonoids of Iris tenuifolia. Am J Chin Med. 2014;42:119–130. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X14500086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morris MC, Evans DA, Tangney CC, Bienias JL, Wilson RS. Fish consumption and cognitive decline with age in a large community study. Arch Neurol. 2005;62:1849–1853. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.12.noc50161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Larrieu S, Letenneur L, Helmer C, Dartigues JF, Barberger-Gateau P. Nutritional factors and risk of incident dementia in the PAQUID longitudinal cohort. J Nutr Health Aging. 2004;8:150–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schaefer EJ, Bongard V, Beiser AS, et al. Plasma phosphatidylcholine docosahexaenoic acid content and risk of dementia and Alzheimer disease: the Framingham Heart Study. Arch Neurol. 2006;63:1545–1550. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.11.1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lim GP, Calon F, Morihara T, et al. A diet enriched with the omega-3 fatty acid docosahexaenoic acid reduces amyloid burden in an aged Alzheimer mouse model. J Neurosci. 2005;25:3032–3040. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4225-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Calon F, Lim GP, Yang F, et al. Docosahexaenoic acid protects from dendritic pathology in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Neuron. 2004;43:633–645. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Neuhouser ML, Tinker L, Shaw PA, et al. Use of recovery biomarkers to calibrate nutrient consumption self-reports in the Women’s Health Initiative. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167:1247–1259. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bowman GL, Shannon J, Ho E, et al. Reliability and validity of food frequency questionnaire and nutrient biomarkers in elders with and without mild cognitive impairment. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2011;25:49–57. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181f333d6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.