Abstract

Introduction:

Robotic-assisted simple prostatectomy (RASP) has been touted as an alternative to open simple prostatectomy (OSP) to treat large gland benign prostatic hyperplasia. Our study assesses our institution’s experience with RASP and reviews the literature.

Methods:

We performed a retrospective chart review from January 2011 to November 2013 of all patients undergoing RASP and OSP. Operative and 90-day outcomes, including operation time, intraoperative blood loss, length of hospital stay (LOS), transfusion requirements, and complication rates, were assessed.

Results:

Thirty-two patients were identified: 4 undergoing RASP and 28 undergoing OSP. There was no difference in mean age at surgery (69.3 vs. 75.2 years; p = 0.17), mean Charlson Comorbidity Index (2.5 vs. 3.5; p = 0.19), and mean prostate volume on TRUS (239 vs. 180 mL; p = 0.09) in the robotic and open groups, respectively. There was a significant difference in the mean length of operation, with RASP exceeding OSP (161 vs. 79 min; p = 0.008). The mean intraoperative blood loss was significantly higher in the open group (835.7 vs. 218.8 mL; p = 0.0001). Mean LOS was shorter in the RASP group (2.3 vs. 5.5 days; p = 0.0001). No significant differences were noted in the 90-day transfusion rate (p = 0.13), or overall complication rate at 0% with RASP vs. 57.1% with OSP (p = 0.10).

Conclusions:

Our data suggest RASP has a shorter LOS and lower intraoperative volume of blood loss, with the disadvantage of a longer operating time, compared to OSP. It is a feasible technique and deserves further investigation and consideration at Canadian centres performing robotic prostatectomies.

Introduction

The surgical management of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) continues to evolve, most recently with the introduction of laser treatments and robotic surgery.1 Despite this evolution in the treatment armamentarium, the open simple prostatectomy (OSP) remains a useful tool for addressing the unique challenge of a large volume prostate gland (>80 g).2

Though the robotic-assisted radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer has seen widespread adoption in the United States, there remains a paucity of literature addressing the role of the robotic-assisted simple prostatectomy (RASP) for prostatomegaly. Sotelo and colleagues first introduced the concept of RASP, the results of which have since been supported by a number of small case series.3,4 The literature suggests RASP is superior to OSP with respect to blood loss, complications, and length of hospital stay.4

This study presents our institution’s initial experience with RASP and examination of 90-day perioperative outcomes. We aim to demonstrate the feasibility of this technique at a Canadian academic centre and review the current literature for this relatively novel technique.

Methods

We performed a retrospective review of all OSP and RASP procedures performed between January 2011 and November 2013. We identified 4 patients who had RASP for varying indications and 28 patients who underwent an OSP in this same time period. All RASP procedures were completed by a single surgeon with fellowship training in minimally invasive surgery and extensive robotic surgery experience. OSP procedures were performed by 8 other urologists with extensive open surgical experience.

Preoperative evaluation included a full history and physical, cystoscopy, routine laboratory assessment with prostate specific antigen, and transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) with prostate volume measurement.

Literature review

A search of PubMed and MEDLINE (1946-Present) was completed using the search terms ‘robot’ and ‘prostatectomy’ or ‘simple prostatectomy.’ The references in electronically identified abstracts were also searched for relevance.

Surgical technique

Under general anesthetic, the patient was prepared and positioned in a Trendelenburg position. A Foley catheter was inserted. A non-cutting trocar was then used to gain direct access to the abdominal cavity, with the remaining ports placed under direct vision in the standard radical prostatectomy configuration with two 8-mm ports on the patient’s left and an 8-mm and 12-mm assistant port on the patient’s right.

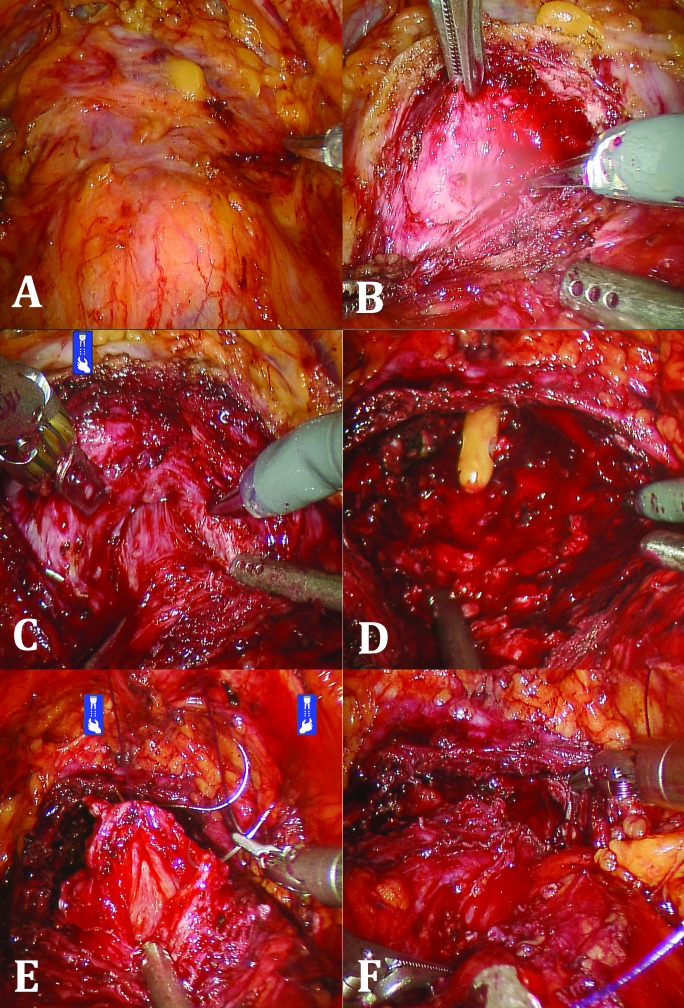

The bladder was then mobilized and the space of Retzius developed. The prostate was approached anteriorly and defatted laterally until the lateral boundaries were well-defined (Fig. 1, part A). A transverse capsulotomy just distal to the bladder neck was then performed (Fig. 1, part B). Dissection was carried out in the plane of the adenoma, with exposure of the urethral fibres at the bladder neck (Fig. 1, part C). The adenoma was liberated from the overlying capsule using a combination of electrocautery and blunt dissection. If a median lobe was present, this was mobilized and removed at its junction with the lateral lobes. A 24-French urethral catheter was then inserted through the penis and visualized prior to circumferential closure of the bladder neck mucosa to urethral mucosa (Fig. 1 parts D, E). Once the catheter was confirmed to pass smoothly, the prostatic capsule was closed with a running Monocryl suture (Fig. 1, part F). Irrigation was performed to reveal any leaks. A Jackson-Pratt drain was then left in situ and the specimen removed via a small suprapubic incision. Continuous bladder irrigation was initiated at the end of the operation. Postoperatively, the catheter was removed in 7 to 14 days.

Fig. 1.

A) Developed space of Retzius and prostate defatted anteriorly and laterally; B) Transverse capsulotomy; C) Exposure of urethral fibres at bladder neck; D) Completed dissection of prostate adenoma; E) Closure of bladder neck mucosa to urethral mucosal; F) Closure of the prostatic capsule with running suture.

Statistical analysis

We used both a Student’s t-test and Mann-Whitney non-parametric test to compare continuous variables, such as age, prostate volume, and length of operation, after assessing data distribution for normality. Categorical variables, such as the use of anticoagulants, were compared with a Fisher’s exact test. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant and all statistics were computed with GraphPad Prism v6.0 software.

Results

Of the 23 patients in our study, 4 underwent RASP (Table 1) and 28 OSP were identified. Of the 4 RASP patients, 2 had symptomatic BPH failing medical therapy, while the other 2 had acute urinary retention with and without an acute kidney injury. There was no difference in mean age at surgery (69.3 vs. 75.2 years; p = 0.17), mean Charlson Comorbidity Index (2.5 vs. 3.5; p = 0.19), use of preoperative anticoagulation (25 vs. 17.9%; p = 1.00), or mean prostate volume on TRUS (239 vs. 180 cc; p = 0.09) in the RASP and OSP groups, respectively (Table 2).

Table 1.

RASP cohort baseline patient characteristics and surgical indications

| Patient | Age (years) | BMI (kg/m2) | Comorbidities | Indication for surgery | Preoperative TRUS prostate volume (mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 69 | 35.7 | Osteoarthritis | Symptomatic BPH failing medical treatment | 218 |

| 2 | 73 | 26.4 | CAD | Symptomatic BPH failing medical treatment, recurrent UTI | 234 |

| 3 | 66 | 25.2 | Hypertension | AUR with acute kidney injury | 195 |

| 4 | 69 | 29 | Hypertension | AUR | 310 |

RASP: robotic-assisted simple prostatectomy; BMI: body mass index; CAD: coronary artery disease; BPH: benign prostatic hyperplasia; UTI: urinary tract infection; AUR: acute urinary retention; TRUS: transrectal ultrasound.

Table 2.

Comparison of RASP and OSP patient demographics

| Characteristic | RASP N (%) or Mean ± SD | OSP N (%) or Mean ± SD | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 69.3 ± 2.9 | 75.18 ± 6.4 | 0.17 |

| CCI | 2.5 ± 1 | 3.5 ± 1.5 | 0.19 |

| Median ASA Score | 2 | 2 | 1.00 |

| Preoperative anticoagulation | 1/4 (25%) | 5/28 (17.9%) | 1.00 |

| Prostate volume on TRUS (mL) | 239 ± 49.8 | 180 ± 54.7 | 0.09 |

RASP: robotic-assisted simple prostatectomy; SD: standard deviation; OSP: open simple prostatectomy; CCI: Charlson Comorbidity Index; TRUS: transrectal ultrasonography; ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists.

We noted a statistically significant difference in the mean length of operation, with the RASP longer than OSP (161.3 vs. 79 minutes; p = 0.008). Mean intraoperative blood loss was also significantly higher in the open group, with 835.7 mL versus a mean loss of 218.8 mL in the robotic group (p = 0.0001). Lastly, the mean length of hospital stay was significantly shorter in the RASP group at 2.3 days compared to 5.5 days in the open surgery cohort (p = 0.0001). No statistically significant differences were noted in the prostate volume on pathology (123.6 vs. 122.9 mL; p = 0.98), 90-day transfusion rate (0 vs. 46.4%; p = 0.13), or the mean number of packed red blood cell units transfused (0 vs. 1.5 units; p = 0.17) between RASP and OSP, respectively. Three patients required 6 or more units, while the rest required 3 or less units.

Regarding 90-day complications, overall rates were statistically similar at 0% with RASP vs. 57.1% with OSP (p = 0.10). When stratified by severity, a higher proportion of the OSP complications were Clavien II (0 vs. 68.8%; p = 0.03). All of these were blood transfusions, except one case of new onset atrial fibrillation. Of the more severe complications (Clavien III and IV), 4 patients required a second operation for a cystoscopy and clot evacuation ± fulguration, and 1 required 2 repeat operations for cystoscopy and clot evacuation, as well as an intensive care unit stay for severe hematuria.

Discussion

As robotic surgery continues to move to the forefront of how we manage many urologic oncologic conditions, it is only natural to consider the extension of robotic surgery to more benign conditions. Our results suggest that RASP is a feasible surgical option for BPH, with acceptable 90-day perioperative outcomes. In our study, robotic prostatectomy was associated with a lower volume of intraoperative blood loss, and a shorter length of stay compared to OSP. However, it had a significantly longer operation time compared to OSP.

OSP has long been considered the gold standard for the management of prostatomegaly. However, it has a number of disadvantages, including a high transfusion rate, long bladder irrigation time, and prolonged postoperative hospitalization – these have left urologists wanting for newer technologies.2,5 Matei and colleagues reviewed 14 studies reporting OSP outcomes (n = 3759) and showed a mean transfusion rate of 11.3%, mean length of operation time of 92.3 minutes, and mean hospital stay of 7.3 days.5 These values are comparable to our OSP mean length of operation time of 79 minutes and a mean length of stay of 5.5 days, though our transfusion rate is higher at 46.4%.

Transfusion rates vary based on surgeon and institutional specific triggers, as well as specific patient comorbidities, potentially explaining the high rate seen in our series. Furthermore, our study has a significantly smaller number of OSP cases. In the same review, the average transfusion rate from 7 RASP series (n = 97) was 2.1%, mean length of operation time was 187.5 minutes, mean blood loss was 303 mL, and the mean length of stay was 2.7 days. Our RASP results follow this trend, with a mean transfusion rate of 0%, operation length of 161.3 minutes, intraoperative blood loss of 218.8 mL, and mean length of stay of 2.25 days. The highest transfusion reported rate was 14.3% (for studies with >3 patients) (Table 3).3

Table 3.

Operative and 90-day outcomes for RASP and OSP cohorts

| Outcome | RASP N (%) or Mean ± SD | OSP N (%) or Mean ± SD | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prostate volume on pathology (mL) | 123.6 ± 40.8 | 122.9 ± 53.6 | 0.98 |

| Operation duration (min) | 161.3 ± 30.1 | 79 ± 27.4 | 0.008* |

| Intraoperative blood loss (mL) | 218.8 ± 181.9 | 835.7 ± 301.2 | 0.0001* |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | 2.25 ± 0.5 | 5.5 ± 1.7 | 0.0001* |

| 90-day transfusion rate | 0/4 (0%) | 13/28 (46.4%) | 0.13 |

| No. units of packed red blood cells transfused | 0 | 1.5 ± 2.3 | 0.17 |

| 90-day complication rate | 0/4 (0%) | 16/28 (57.1%) | 0.10 |

| Clavien I1 | 0/4 (0%) | 2/28 (7.1%) | 1.00 |

| Clavien II | 0/4 (0%) | 11/28(39.3%) | 0.27 |

| Clavien III | 0/4 (0%) | 4/28 (14.3%) | 1.00 |

| Clavien IV | 0/4 (0%) | 1/28 (3.6%) | 1.00 |

RASP: robotic-assisted simple prostatectomy; SD: standard deviation; OSP: open simple prostatectomy; CCI: Charlson Comorbidity Index; TRUS: transrectal ultrasonography; ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists.

Note: Some patients had multiple complications resulting in multiple Clavien grades assigned.

p < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Autorino and colleagues published the largest multi-institutional series to date with 487 RASP cases.6 This study noted a 154.5-minute median length of operation, median blood loss of 200 mL, postoperative complication rate of 16.6%, and median length of stay of 2 days. The two most common complications were acute urinary retention requiring catheterization (2.1%) and hematuria requiring catheter irrigation (2.7%). These values are all comparable with our small series, though our 0% 90-day complication rate likely reflects a small sample size and short follow-up (Table 4).

Table 4.

Literature review of outcomes for RASP

| Study | N | Operation duration (min) | Intraoperative blood loss (mL) | Transfusion rate (%) | LOS (days) | Complication rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sotelo et al.3 | 7 | 205 | 298 | 14.3 | 1.3 | 14 |

| Yuh et al.11 | 3 | 211 | 55 | 33 | 1.3 | 33 |

| John et al.12 | 13 | 210 | 500 | 0 | 6 | 8 |

| Uffort and Jensen13 | 15 | 128.8 | 139.3 | 0 | 2.6 | 7 |

| Sutherland et al.14 | 9 | 183 | 206 | 0 | 1.3 | 56 |

| Matei et al.5 | 35 | 187 | 118 | 0 | 3.2 | 0 |

| Clavijo et al.15 | 10 | 106 | 375 | 10 | 1 | 20 |

| Bonapour et al.4 | 16 | 228 | 197 | 0 | 1 | 13 |

| Leslie et al.16 | 25 | 214 | 143 | 4 | 4 | 16 |

| Patel and Hemal17 | 20 | – | – | 0 | 1.7 | 10 |

| Stolzenburg et al.18 | 10 | 122.5 | 230 | 0 | 8.4 | 10 |

| Autorino et al.6 | 487 | 154.5 | 200 | 1 | 2 | 11 |

| Present series | 4 | 161.3 | 219 | 0 | 2.3 | 0 |

LOS: length of stay; RASP: robotic-assisted simple prostatectomy.

RASP has many of the same advantages as robotic-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy for prostate cancer. Robotic surgery advocates often cite the 3D view, superior dexterity afforded by the Endowrist technology, ergonomic comfort, and improved view of the surgical field, as benefits of the technology over pure laparoscopy and open prostatectomy.7

Another consideration with robotic surgery is cost efficiency. Though beyond the scope of this study, this is an important factor, especially in the cost-conscious Canadian healthcare system. Matei and colleagues5 addressed this issue and determined that although the instrument costs and operating costs, secondary to longer operating times, of RASP exceeded OSP, RASP was ultimately more cost-effective (by about $850 CAD per patient).5 Savings were mainly secondary to a decreased length of hospitalization. The social impact of robotic surgery, including patients returning to work sooner, has yet to be quantified and could further support the cost-effective argument of RASP. A comprehensive cost analysis of robotic and open prostatectomy by Ahmed demonstrated that despite shorter hospitalizations and length of surgery, the cost of robotic surgery still exceeded open surgery.8 The initial start-up cost and maintenance costs were the main drivers of this difference. This suggests RASP should only be performed at centres with a robotic platform used for other indications, where increased robotic use can depreciate the cost-per-case of the robotic platform.

Some authors argue the true comparison for RASP, as a minimally invasive option for BPH, is laser enucleation.6 Laser enucleation benefits from a shorter operating time, shorter length of stay, and shorter length of catheterization compared to open and minimally invasive simple prostatectomy (including laparoscopic prostatectomy).6,9,10 However, there are no studies comparing laser enucleation to RASP and this remains an area for future research.10

We recognize the limitations of this study, notably its small sample size and retrospective design. There is a risk of selection bias without randomization. Though we compared outcomes between the robotic and open cohorts for discussion purposes, no definite conclusions can be drawn without the benefit of larger numbers and randomization. Length of follow-up is also limited to only 90 days. It would be interesting to look at clinical outcomes of the group (i.e., change in International Prostate Symptom Score score), but this was beyond the scope of the study. Generalizability of these results may be limited, as our robotic surgeon has extensive experience with robotic prostatectomies at a high-volume tertiary centre.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates the feasibility of RASP at a Canadian urologic centre. Our data suggest RASP is associated with a shorter hospital stay and a lower intraoperative volume of blood loss, compared to OSP, with the disadvantage of a significantly longer operation time. These results and the rapidly growing literature pave the way for future prospective studies comparing RASP to OSP, and potentially to laser enucleation, for the management of BPH. RASP deserves further investigation and consideration at Canadian centres performing robotic prostatectomies.

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors all declare no competing financial or personal interests.

This paper has been peer-reviewed.

References

- 1.Metcalfe C, Poon KS. Long-term results of surgical techniques and procedures in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Curr Urol Rep. 2011;12:265–73. doi: 10.1007/s11934-011-0193-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Serretta V, Morgia G, Fondacaro L, et al. Open prostatectomy for benign prostatic enlargement in southern Europe in the late 1990s: A contemporary series of 1800 interventions. Urology. 2002;60:623–7. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(02)01860-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sotelo R, Clavijo R, Carmona O, et al. Robotic simple prostatectomy. J Urol. 2008;179:513–5. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.09.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banapour P, Patel N, Kane CJ, et al. Robotic-assisted simple prostatectomy: A systematic review and report of a single institution case series. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2014;17:1–5. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2013.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matei DV, Brescia A, Mazzoleni F, et al. Robot-assisted simple prostatectomy (RASP): Does it make sense? BJU Int. 2012;110:E972–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Autorino R, Zargar H, Mariano MB, et al. Perioperative outcomes of robotic and laparoscopic simple prostatectomy: A european-american multi-institutional analysis. Eur Urol. 2015;68:86–94. doi: 10.1016/S1569-9056(14)50114-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumar R, Hemal AK. Emerging role of robotics in urology. J Minim Access Surg. 2005;1:202–10. doi: 10.4103/0972-9941.19268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahmed K, Ibrahim A, Wang TT, et al. Assessing the cost effectiveness of robotics in urological surgery - a systematic review. BJU Int. 2012;110:1544–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuntz R, Lehrich K, Ahyai S. Holmium laser enucleation of the prostate versus open prostatectomy for prostates greater than 100 grams: 5-year follow-up results of a randomized clinical trial. Eur Urol. 2008;53:160–6. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lucca I, Shariat SF, Hofbauer SL, et al. Outcomes of minimally invasive simple prostatectomy for benign prostatic hyperplasia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Urol. 2014;33:563–70. doi: 10.1007/s00345-014-1324-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yuh B, Laungani R, Perlmutter A, et al. Robot-assisted millin’s retropubic prostatectomy: Case series. Can J Urol. 2008;15:4101–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.John H, Bucher C, Engel N, et al. Preperitoneal robotic prostate adenomectomy. Urology. 2009;73:811–5. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uffort E, Jensen J. Robotic-assisted laparoscopic simple prostatectomy: An alternative minimal invasive approach for prostate adenoma. J Robot Surg. 2010;4:7–10. doi: 10.1007/s11701-010-0180-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sutherland DE, Perez DS, Weeks DC. Robot-assisted simple prostatectomy for severe benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Endourol. 2011;25:641–4. doi: 10.1089/end.2010.0528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clavijo R, Carmona O, De Andrade R, et al. Robot-assisted intrafascial simple prostatectomy: Novel technique. J Endourol. 2013;27:328–32. doi: 10.1089/end.2012.0212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leslie S, Abreu AL, Chopra S, et al. Transvesical robotic simple prostatectomy: Initial clinical experience. Eur Urol. 2014;66:321–9. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patel MN, Hemal AK. Robot-assisted laparoscopic simple anatomic prostatectomy. Urol Clin North Am. 2014;41:485–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stolzenburg JU, Kallidonis P, Qazi H, et al. Extraperitoneal approach for robotic-assisted simple prostatectomy. Urology. 2014;84:1099–105. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2014.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]