Abstract

Leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) is the most pleiotropic member of the interleukin-6 family of cytokines. It utilises a receptor that consists of the LIF receptor β and gp130 and this receptor complex is also used by ciliary neurotrophic growth factor (CNTF), oncostatin M, cardiotrophin1 (CT1) and cardiotrophin-like cytokine (CLC). Despite common signal transduction mechanisms (JAK/STAT, MAPK and PI3K) LIF can have paradoxically opposite effects in different cell types including stimulating or inhibiting each of cell proliferation, differentiation and survival. While LIF can act on a wide range of cell types, LIF knockout mice have revealed that many of these actions are not apparent during ordinary development and that they may be the result of induced LIF expression during tissue damage or injury. Nevertheless LIF does appear to have non-redundant actions in maternal receptivity to blastocyst implantation, placental formation and in the development of the nervous system. LIF has also found practical use in the maintenance of self-renewal and totipotency of embryonic stem cells and induced pluripotent stem cells.

Keywords: leukemia inhibitory factor, JAK/STAT/SOCS, LIF receptor, embryonic stem cells, pregnancy, nerve and muscle

Introduction

LIF was first cloned as an inducer of differentiation and inhibitor of proliferation of a myeloid leukemic cell line (M1) [1]. At the same time other groups were purifying activities that suppressed differentiation of embryonic stem cells (DIA) [2], stimulated proliferation of myeloid DA1 cells (HILDA) [3], induced an acute phase response in hepatocytes (HSF) [4], caused neurotransmitter switching in neurons (CNDF) [5] [6] and inhibited adipocyte lipoprotein lipase activity (MLPLI) [7]. Following purification each of these activities was shown to be identical to LIF. In this review we will summarize the molecular features of LIF/receptor interactions and intracellular signalling as well as the highly pleitropic biological activities of LIF with an emphasis on non-redundant actions.

The LIF glycoprotein

LIF is synthesised as a 202 amino acid precursor that is post-translationally processed into a 20 kDa form by removal of 22 amino acids from its N-terminus. LIF structures have been solved by both X-ray crystallography [8] and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) [9] and these studies have shown that, similarly to other IL-6 family cytokines, LIF exists as a compact four-helix bundle in an up-up-down-down configuration. The first helix (helix A) begins at residue Leu44 (residue 22 of the mature chain) and the region N-terminal to this is covalently linked to the C-terminal section of helix 3 via two disulphide bonds (Cys34-Cys156 and Cys40-Cys153). This N-terminal region is important for receptor binding [10]. In addition to the aforementioned disulphide bridges, there is a third disulphide bond that joins helix D to the linker between helices A-B. NMR analyses showed that LIF is an extremely stable molecule as evidenced by extremely slow amide-exchange rates and relaxation parameters.

The LIF Receptor consists of two signalling chains: gp130 and LIFRβ

LIF and IL-6 are closely related cytokines that both signal through the shared cytokine receptor gp130 [11]. Despite this, there are dramatic differences between the receptors of these two cytokines, in terms of stoichiometry, composition, architecture and thermodynamics. The signalling competent complex between IL-6 and its receptor is a hexamer that consists of two molecules each of IL-6, gp130 and IL-6 Receptor alpha (IL-6Rα) [12, 13]. Hexameric assembly is required because the intracellular domain of IL-6Rα does not bind JAK and so signal transduction can only be achieved by transactivation of two JAK molecules bound to the two copies of gp130. This architecture is also shared by IL-11 [14].

On the other hand, the signalling competent complex of LIF with its receptor is a trimer [15] that consists of LIF bound to one molecule of gp130 as well as a second receptor chain called LIFR (LIF receptor-which we will subsequently refer to as LIFRβ) [16] that is architecturally similar to gp130 [17]. Like gp130, LIFRβ binds JAK via its intracellular domain [18] and hence signal transduction can be initiated by transactivation of the gp130-bound and LIFRβ-bound JAK molecules without requiring higher-order association. Notably, there is no “alpha-chain” receptor required for LIF signalling (see Fig. 1).

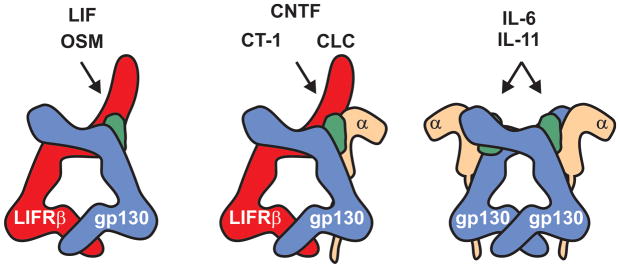

Fig. 1. LIF signals through a heterodimeric receptor.

Both chains of the LIF receptor (LIFRβ and gp130) are shared by other IL-6 family cytokines. LIF and OSM bind a gp130:LIFRβ heterodimer whilst CNTF, CT-1 and CLC bind to the same heterodimer with the help of a specific receptor alpha chain (CNTFα). IL-6 and IL-11 bind a receptor that consists of two gp130 chains and two specific alpha chains (IL-6Rα and IL-11Rα respectively). Unlike other cytokines represented here, two molecules of IL-6 or IL-11 are required to form the signalling-competent complex, resulting in a hexamer.

LIFRβ

LIFRβ is a single pass transmembrane domain-containing protein and is the tallest of the “tall” cytokine receptors, containing eight distinct domains in its extracellular segment [16]. These eight domains are all of β-sandwich architecture [19] and can be sub-classified as two cytokine binding modules (CBMs, themselves each composed of two individual β-sandwich domains) separated by an immunoglobin-like domain followed by three fibronectin type III (FnIII) domains at the membrane proximal end. The FnIII domains are sometimes referred to as the “legs” of the tall receptors and ensure the correct placement of the transmembrane and intracellular domains such that JAK activation, by cross-phosphorylation, can occur after cytokine binding. gp130, which will be more fully discussed elsewhere in this issue, is highly similar, lacking only the first CBM.

The structure of domains 1-5 of LIFRβ have been solved by X-ray crystallography, both with [19] and without [15] bound LIF. The two CBM’s are structurally similar; both adopt elbow-like structures bent at ~70° and overlay with significant similarity [10]. The Ig-like domain that separates these two modules is oriented perpendicular to the first CBM (forming a “T”-helped by a disulphide) and is roughly co-linear with the first β-sandwich domain of the second CBM. Overall, domains 1-5 of the receptor adopt a roughly co-linear “zig-zag”-like conformation, 160 angstroms long x 60 wide. To date there is no structural data on the “legs” of the LIF receptor.

Although termed the LIF-receptor, LIFRβ is actually shared between five cytokines: LIF, oncostatin M (OSM), cardiotrophin-1 (CT-1), ciliary neurotrophic growth factor (CNTF) and cardiotrophin-like cytokine (CLC). All of these cytokines signal via a gp130:LIFRβ heterodimer [20]. The latter three also require an alpha-chain receptor (CNTFRα) to form a quaternary complex in order to initiate signalling. OSM, like LIF, can signal through a simple gp130:LIFRβ dimer (Fig. 1).

Interaction between LIF and its receptor

Thermodynamically, LIF engages its receptor in a very different manner to the similar cytokine, IL-6. IL-6 binding to gp130 and IL-6Rα is an ordered and co-operative process [12]: IL-6 first recruits its specific alpha receptor chain (IL-6Rα) with high affinity (Kd = 9 nM) using a surface on one face of the 4-helix bundle known as site I. This IL-6/IL-6Rα complex then recruits gp130 using a surface composed of residues from both IL-6 (site II) and IL-6Rα. The resulting ternary complex dimerises cooperatively to form the signalling hexamer. Importantly, IL-6 on its own does not display measurable binding affinity for gp130.

LIF, on the other hand, binds with high affinity to both gp130 (via site II) [10] and LIFRβ (via site III at one end of the four helix bundle and the Ig-like domain of LIFRβ) [10]. Formation of the ternary complex is non-cooperative and is thus unlikely to be ordered. The interaction between LIF with both the receptor chains (gp130 and LIFRβ) is entropically driven and there is surprisingly little structural perturbation in either cytokine or receptor upon binding. The interaction of LIF with LIFRβ is 80-fold tighter than with gp130, which is perhaps unsurprising given that gp130 interacts with a slightly larger array of cytokines than LIFRβ. In vivo LIF binds to receptor with high affinity (Kd = 50–100pM affinity), consistent with two individual high affinity interactions with the two membrane bound receptor chains [21, 22]. A kinetic analysis showed that interaction of LIF with physiological receptor showed a near diffusion-limited on-rate and an extremely slow off-rate (4 × 10−4/min suggesting a half-life of more than 24 hours) at 4°C [22].

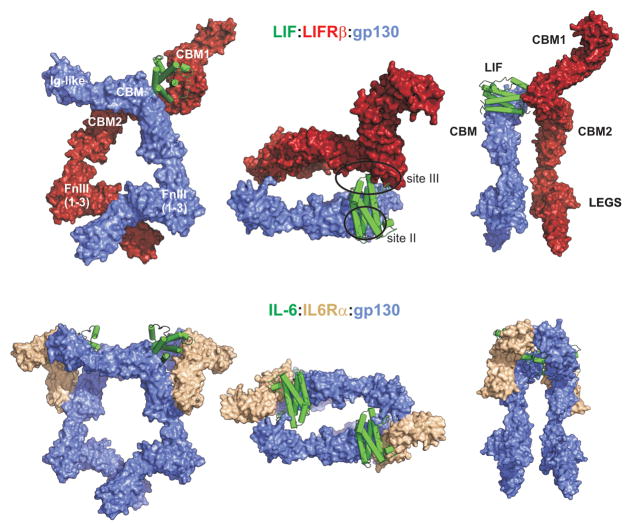

Using available structures, a model of the LIF:gp130:LIFRβ complex can be built (Fig. 2). The full ectodomain structure of gp130 was solved using X-ray crystallography in 2010 [17] and the structure of domains 1-5 of LIFRβ in 2007 [19]. Although there is no structural information regarding the legs of LIFRβ, the corresponding region of gp130 shows a pronounced kink between the first and second FnIII domains, which in the case of IL-6 and IL-11, can be modelled into existing cryo-EM data [14, 23]. By assuming the same kink in the FnIII legs of LIFRβ, models of the full LIF:LIFRβ:gp130 can be built. Interestingly, the models produced are very similar no matter whether the IL-6:gp130:IL-6Rα hexameric complex is used as a reference (and LIFRβ and LIF aligned to one copy of gp130 and IL-6 respectively) or whether the LIF:LIFRβ complex is used as a reference (and the LIF:gp130 structure aligned on LIF). Observation of this model suggests that LIF cross-links its two receptor chains in such a way that they enter the cell membrane in close proximity, potentially important for subsequent activation of intracellular JAKs and agree well with the cryo-EM data of a signalling competent complex of CNTF with its receptor (which also includes gp130 and LIFRβ) solved by the Garcia Laboratory [15]. Comparing this model with the well-characterised IL6:IL-6 Receptor system highlights two obvious differences (in addition to their different stoichiometry). The first is the cytokine-sized “gap” between gp130 (Ig-like domain) and LIFRβ (CBM2) that, in the IL-6 system, is occupied by a second cytokine molecule. The second is the large extension of CBM1 of LIFRβ which begs the obvious question-does it have a function in LIF signalling?

Fig. 2. A model of LIF bound to its receptor.

Upper panels: Three orthogonal views of LIF (green) bound to the gp130 (blue):LIFRβ (red) heterodimer. Left and right panels show orthogonal views of the complex as viewed parallel to the cell-membrane whereas the central panel is viewed looking down towards the cell-membrane. Similar representations of the signalling-competent IL-6:gp130:IL-6Rα hexamer structure are shown below. The LIF receptor consists of two cytokine-binding modules (CBMs) separated by an immunoglobulin-like (Ig-like) domain. Three Fibronectin domains (FnIII) make up the “legs” of both receptors. gp130 has a similar architecture to LIFRβ but lacks the first CBM. Note the absence of an alpha-receptor (beige) in the LIF system. The LIF:LIFRβ:gp130 model was constructed by overlaying the structure of the LIFRβ:LIF (PDB ID: 2Q7N) complex onto the gp130 molecule from the IL-6:gp130:IL-6Ra hexamer (PDB IDs: 3L5H, 1P9M) and modelling the “legs” of LIFRβ on gp130 (PDB ID: 3L5H).

LIF signalling

LIF is a pleiotropic cytokine with a wide range of activities so it is unsurprising that functional LIF receptors are found in a number of different organs including the liver [21], bone [24], uterus [25], kidney and the central nervous system [26]. Quantitative studies have shown that they are found on the surface of ES cells (approximately 100–400 receptors per cell) [22, 27], in particularly high numbers in the liver (several thousand per cell) whilst within the hematapoietic system, LIF receptors primarily exist on monocytes/macrophages (several hundred per cell) [21].

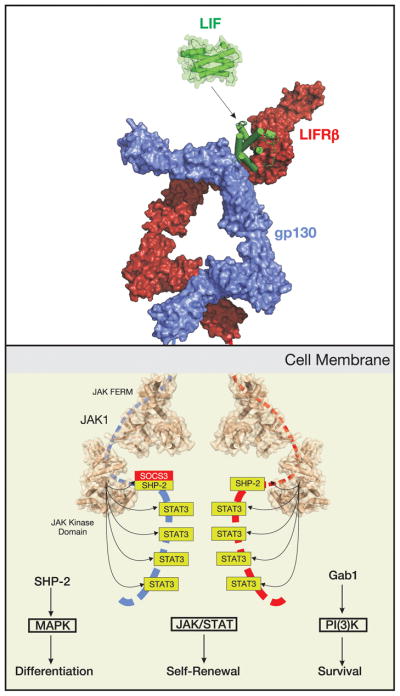

Unlike receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), the LIF receptor does not have any intrinsic tyrosine kinase activity within its intracellular domains. Instead both the gp130 and LIFRβ chains are constitutively associated with members of the JAK family of tyrosine kinases [28]. These kinases exist in an inactive state under basal conditions but are rapidly activated upon LIF engaging its receptor, via a molecular mechanism that is not yet understood. There are four members of the JAK family (JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, TYK2). Experiments using overexpressed components initially showed that the LIF receptor is capable of binding at least three of the four JAK family members (JAK1, JAK2 and TYK2) [18]. However knockout studies reveal that LIF signalling is highly abrogated in the absence of JAK1 but not JAK2 or TYK2, suggesting it is the dominant JAK family member under physiological conditions [29–31]. In support of this, Ernst and colleagues showed activation of JAK1, 2 and TYK2 following LIF exposure but significantly faster activation kinetics for JAK1, implying again that it is the kinase initially targeted by LIF [32]. Activation of JAK1 occurs by transphosphorylation, the JAK1 molecule on one receptor chain activating the other by phosphorylation of specific tyrosines, particularly Tyr1034. This tyrosine is located within the “activation loop” of the kinase domain and induces a conformational change in this loop such that it moves out of the active site of the kinase to allow substrate and Mg-ATP to dock [33]. Thus LIF engagement of its receptor results in JAK1 becoming catalytically competent, JAK1 then initiates a cascade of tyrosine phosphorylation that stimulates three distinct signalling pathways: the JAK/STAT [18], MAP-kinase [34] and PI(3) Kinase [35, 36] pathways. Collectively these pathways contribute to differentiation, survival and self-renewal. The contributions, both quantitatively and qualitatively, of the JAK/STAT, MAP-kinase and PI(3) Kinase [35–37] pathways following LIF stimulation are often cell-type specific. As an example, we will next discuss the effects of these pathways on murine Embryonic Stem Cell (ES cell) renewal (see Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. LIF signalling.

Extracellular LIF stimulates JAK/STAT, MAPK and PI(3)K signalling, forming a 1:1:1 ternary complex. Intracellularly, both chains of the LIF receptor (LIFRβ and gp130) are bound to JAK1, the tyrosine kinase that initiates the signalling cascade. JAK1 phosphorylates five tyrosines on each receptor chain, four of these are docking sites for the transcription factor STAT3 (allowing stimulation of the JAK/STAT signalling pathway) whilst the fifth is a docking site for SHP-2 (which stimulates the MAPK pathway) and SOCS3 (which negatively regulates both the JAK/STAT and MAPK pathways). LIF stimulates a mixture of differentiation, survival and renewal programs, the balance of which determines the cell’s fate. In embryonic stem (ES) cells, signalling is skewed towards survival and self-renewal.

LIF signalling in embryonic stem cells

Embryonic stem cells (ESCs) are derived from the inner cell mass of early blastocysts and retain the potential to contribute to all embryonic tissues but not the extra-embryonic structures such as the placenta. Following implantation of the blastocyst the inner cell mass develops into the epiblast from which epiblast stem cells arise with similar properties to ESCs though with somewhat reduced totipotency and capacity for self renewal.

LIF was identified as the differentiation inhibiting activity for mouse ESCs that maintained ESCs in a totipotent state and stimulated self-renewal [27]. In contrast human ESCs do not require LIF for maintenance but rather depend on fibroblast growth factor 2 and activin A. Mouse epiblast stem cells display similar colony morphology, behaviour and cytokine requirements to human ESCs suggesting that in the human, ‘ESCs’ behave more like the more mature epiblast stem cells [38].

(i) STAT3 signalling

Once activated by LIF, receptor-bound JAK1 initially targets tyrosines on the intracellular domains of the LIF receptor for phosphorylation. The phosphorylated receptor chains (both gp130 and LIFRβ) then act as scaffolds to recruit a number of signalling entities, perhaps the most important of which is STAT3.

The STAT proteins are a family of transcription factors that are usually present in an inactive state in the cytoplasm [39]. Within the STAT family, STAT-1,3 and 5 are activated by gp130 family cytokines. Within this subgroup STAT3 is seen to be the most important signal transducer following stimulation by LIF and the one which mediates most of the cellular effects [40, 41]. STAT3 docks to phosphorylated tyrosines in both the gp130 and LIFRβ chains of the LIF receptor at YxxM motifs (Y767, Y814, Y905 and Y915 in gp130 [42, 43]; Y981, Y1001, Y1028 in LIFRβ-human numbering) [44]. Once docked, STAT3 is then itself phosphorylated by JAK1, this activation step allowing it to form a signalling-competent dimer [45] that translocates into the nucleus and up-regulates the transcription of the appropriate cytokine responsive genes.

One direct target of STAT3 is the protein SOCS3 [46–48]. SOCS3 is highly up-regulated following exposure to LIF and it then acts to shut down the JAK/STAT signalling cascade, forming a negative feedback loop [49]. SOCS3 is able to achieve this by binding to both JAK1 and gp130 [50, 51] and both inducing their ubiquitination [52] as well as directly inhibiting JAK’s catalytic activity. Interestingly, the site on gp130 (and potentially LIFRβ) to which SOCS3 binds is the phosphotyrosine motif that usually recruits SHP2 (also known as PTNP11) to activate the MAP-kinase pathway (see below) [53]. Therefore, in addition to inhibition of STAT3 signalling, SOCS3 also inhibits MAPK signalling by competing with SHP2 for its binding site on the LIF receptor. SOCS3 knockout animals die in utero due to defects in placentation caused by overactive LIF signalling [54], a phenotype that can be rescued by knocking out LIFRβ[55]

STAT3 is required to maintain ES cells in an undifferentiated state. Overexpression of a dominant-negative STAT3 construct in ES cells leads to both differentiation and a loss of self-renewal [41]. Active STAT3 was in fact shown to be sufficient for maintaining ES cells in culture by Matsuda et al., who used a chimaera between STAT3 and the estrogen receptor to produce conditionally activated (phosphorylated) STAT3 using Tamoxifen [56]. A number of targets of STAT3-mediated transcription have been linked to its ability to maintain ES cells, most notably myc and nanog.

(ii) PI(3)-kinase signalling

PI(3)-kinase is an enzyme that catalyses the formation of the second messenger molecule, phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-triphosphate from phosphatidylinositol (4,5)-diphosphate which in turn activates a number of downstream effectors. Activation of the PI(3)-kinase pathway following LIF stimulation is driven by a cytokine-induced association between JAK1 and the p85 subunit of PI(3)-kinase22. It is unclear whether, like that seen for STAT and MAPK activation, this requires receptor phosphorylation to occur beforehand. Activation of p85 leads to activation of the serine/threonine kinase AKT (protein kinase B) at the cell membrane and stimulation of a number of pathways, such as mTOR, important for cell cycle regulation and metabolism as well as downregulation of wnt signalling by inhibition of GSK3β (Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3β).

The importance of PI(3)-kinase signalling in ES cells has been investigated by Paling and colleagues using both pharmacological inhibition and expression of a dominant-negative form of p85. These experiments showed that when the PI(3)-kinase pathway was inhibited, ES cells spontaneously differentiated, even in the presence of LIF [57]. In fact ES cells expressing an activated form of AKT can be maintained in an undifferentiated state in the absence of LIF [58]. Thus, similarly to STAT3, artificially enhanced PI(3)-kinase signalling is sufficient to maintain murine ES cells

(iii) MAPK signalling

Similarly to STAT activation, the MAPK pathway is activated by recruitment of signalling components to the activated LIF receptor [59]. Both chains of the receptor contain sites that, when phosphorylated, can recruit the phosphatase SHP2 [60]. These sites are Y759 in gp130 [44, 61] and Y974 in LIFRβ [62]. Activated SHP2 induces Ras/Raf signalling which leads to activation of MAPK and ultimately activation of transcriptional activators such as elk [63]. In many cases this leads to mitogenic and/or differentiation programs being induced. As stated above, SOCS3 also binds pY759 of gp130 and hence its induction by STAT3 leads to inhibition of the MAPK signalling cascade [64].

A comparison of the MAP-kinase pathway to the JAK/STAT and PI(3)K [35, 36] pathways in ES cell renewal highlights some interesting contrasts. Although LIF stimulates activation of all three, inhibition of the MAPK cascade, either pharmacologically or genetically (via deletion of MAPK2) leads to an increase in ES cell self-renewal [65, 66]. This implies that MAPK signalling is usually required for differentiation, rather than maintaining pluripotency and shows that even though MAPK signalling is induced by LIF, it is subservient to STAT3 and PI(3)K signalling in this system.

Indeed SOCS3−/− ESC differentiate to primitive endoderm in the presence of LIF [31, 55, 67], and this appears to be due to overactivity of the MAPK pathway (since the SHP2 pathway activating MAPK is hyperactive in these cells as a result of non-competition with SOCS3 for binding of SHP2 to the receptor, and MEK (MAPK kinase) inhibition restores pluripotency in these ES cells [67]). Thus LIF binding induces competing pathways that have to be balanced in order to achieve pluripotency and self-renewal. Indeed the requirement of ESCs for LIF to maintain totipotency can be overcome by the use of signalling pathway inhibitors. Specifically, these are (i) a MAPK pathway inhibitor (which may mimic the effect of LIF-induced SOCS3, (ii) a GSK3 inhibitor [68] (which may mimic LIF induced activation of the PI(3)K pathway) and (iii) an FGF (Fibroblast Growth Factor) receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor. In addition, the requirement for LIF can be overcome by the expression of pluripotency genes nanog, Klf2 and mutant myc [38]. However, the relationship of LIF signalling to the induction of the pluripotency genes is unclear since only myc appears to be a direct transcriptional target of LIF signalling.

Despite the apparent requirement of ESCs for LIF in vitro this does not seem to be essential in vivo because both LIF−/− and LIFRβ−/− blastocysts develop normally in wild-type pseudo-pregnant hosts. Gp130−/− blastocysts do however show a failure to develop after diapause (arrested development of the blastocyst prior to implantation) but it is unclear whether this is due to failed LIF signalling or other cytokines utilising this receptor [69]. These data suggest that while some LIF pathways are directly involved in maintaining pluripotency there may be other pathways that can compensate in the absence of LIF.

LIF also appears to be required during both the induction and maintenance phases of the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) from mature somatic cells. These cells can be induced by the forced expression of key transcriptional factors (including Oct3/4, SOX2, c-Myc and Klf4) [70] and both the induction of the pluripotency transcriptional network [71] and the survival/self-renewal of iPSCs [72] was dependent on LIF or or LIF-like signalling.

Like stem cell factor (SCF), LIF has been shown to stimulate the proliferation of embryonic primordial germ cells (the progenitors of the gametes) in primary cultures on feeder layers [73] and LIF can be used to direct these cells to self-renewing pluripotency (embryonic germ cells) [74]. Since LIF−/− male mice appear fertile and female blastocysts develop normally when transplanted into a normal host, LIF does not seem to play a critical or non-redundant role in the normal development of male or female gametes.

Reproduction

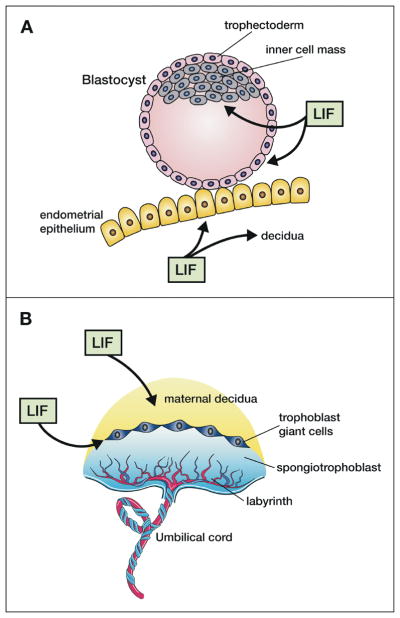

During normal human pregnancy the uterine endometrium is influenced by the altered sex steroid levels of the menstrual cycle to become receptive to the developing blastocyst. Receptivity peaks at day 7 post-fertilization at which time the blastocyst can attach to the uterine epithelial cells and at this time the uterine tissue begins remodelling (decidualisation) to allow the trophectoderm layer of the blastocyst to invade the uterine tissue to help form the placenta that juxtaposes the fetal and maternal blood systems. The trophoblasts form two layers of the developing placenta (the external syncytiotrophoblast and the inner cytotrophoblast layer) and induce remodeling of the uterine spiral arteries to increase maternal blood flow in apposition to developing blood vessels in the embryonic villi (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. LIF actions in reproduction.

A. LIF produced by the endometrial glands (and possibly by the blastocyst) acts on the endometrial epithelium to make it receptive to blastocyst attachment and on the stroma to decidualise it ready for implantation and placenta development. LIF also acts on the inner cell mass of the blastocyst to maintain totipotency during diapause and on the trophectoderm to induce trophoblast invasion into the endometrium. B. LIF is important for the formation of the maternal decidua and balanced LIF activity is essential for formation of trophoblast giant cells as well as the correct architecture of the labyrinth layer in which maternal and fetal blood vessels come into contact.

LIF −/− female mice are infertile due to a failure of blastocyst implantation [75]. LIF is highly expressed in the uterine endometrial glands at the time of blastocyst formation and prior to blastocyst implantation in both mice and humans [76] probably as a result of the rise in estrogen levels during the menstrual cycle [77]. LIF receptors are present on the blastocyst as well as the endometrium and trophoblasts but the failure in LIF−/− mice is on the maternal side since both LIF−/− and LIF receptor −/− embryos implant successfully in pseudopregnant wild-type hosts. In addition there is some evidence that LIF and LIF receptor expression may play a role in ectopic pregnancies in the fallopian tubes [78].

LIF secretion levels in uterine flushings and from ex-vivo explants have been reported to be significantly lower at the late proliferative and early secretory phases in women with proven infertility [79] and in rare cases mutations in the LIF gene itself (thought to alter LIF binding to its receptor or to alter LIF expression levels) have been reported in infertile women [80]. This has suggested that LIF might be used to treat infertility in women or conversely that LIF antagonists might be used as contraceptives. Indeed neutralizing antibodies to LIF or an engineered long-lasting LIF antagonist (a modified LIF molecule) have been shown to prevent pregnancies in mice and non-human primates [81, 82].

LIF has been shown to induce differentiation of trophoblast-like choriocarcinoma cell lines and invasiveness of immortalized first trimester trophoblasts [83, 84]. SOCS3 is a major negative regulator of LIF signalling and SOCS3−/− mice die in utero at E13 from a failure of placentation. The defect is a poorly formed labyrinthine and spongiotrophoblast layer as well as excessive numbers and size of trophoblast giant cells. The use of tetraploid aggregation embryos where the extra-embryonic trophoblast layer is wild type rescued the placentation defect in SOCS3 −/− mice as did crossing to a LIF−/− embryonic background. These data suggest that excessive embryonic LIF acts to differentiate trophoblasts to giant cells and disrupts placental architecture [55, 85].

LIF also appears to play a crucial role in mammary gland involution following weaning. In LIF−/− mice involution is delayed and reduced apoptosis is seen while mammary glands show precocious development during pregnancy and these effects are dependent on STAT3 [86].

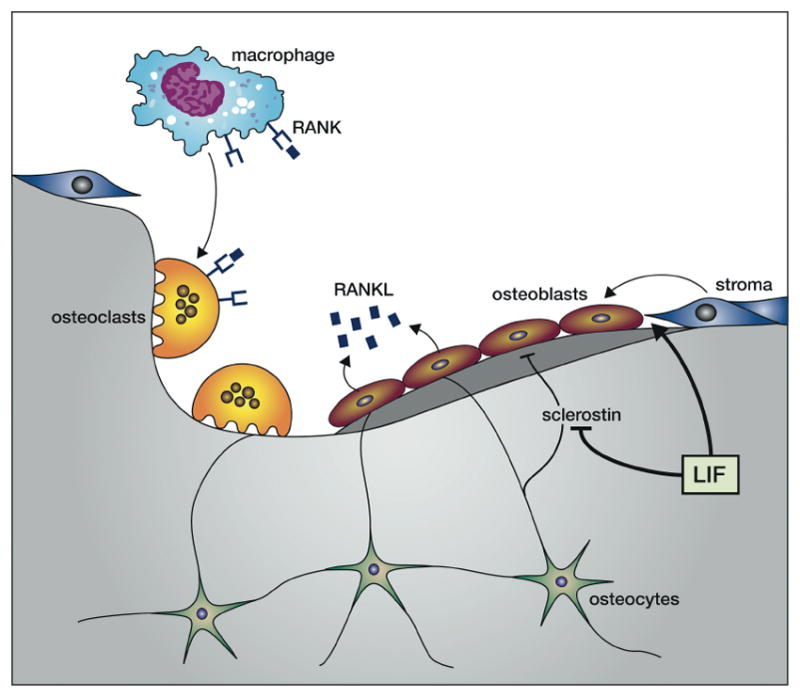

Bone Remodelling

Cortical and trabecular bone is continually remodelled to maintain blood calcium levels, restore damaged regions and respond to hormones and diet. Osteoclasts, derived from monocytic precursors, degrade bone while osteoblasts, derived from mesenchymal cells, form the extracellular matrix required for new bone deposition. Osteoblasts can differentiate into osteocytes that are embedded in the bone matrix and send long cellular processes to communicate with osteoblasts at the bone surface. Communication between osteoblasts and osteoclasts by the secretion of cytokine-like proteins serves as a feedback mechanism to regulate the balance of bone formation and destruction. For example osteoblasts secrete RANKL, a TNF-like cytokine that activates osteoclasts as well as its inhibitor osteoprotegerin, a decoy receptor for RANKL, and osteocytes produce the wnt antagonist sclerostin that is a major inhibitor of bone formation (Fig. 5). Chondrocytes are found at the growth plate of growing bones and in the joints where they produce articular cartilage required for joint movement.

Fig. 5. LIF actions in bone remodelling.

LIF acts on bone stromal cells to enhance differentiation into bone-forming osteoblasts and inhibits the production of osteoblast-inhibitory sclerostin by osteocytes. Osteoblasts produce the TNF-like cytokine RANKL that acts on receptors on macrophages to induce differentiation into multi-nucleate osteoclasts that resorb bone. These linked phenomema allow repair of damaged bone by first clearing the damaged bone and then inducing new bone formation.

Osteoblasts express high affinity receptors for LIF and LIF enhances the differentiation of bone marrow stromal cells to the osteoblast lineage while also inhibiting differentiation towards adipocytes [87]. While mice injected with a cell line over-expressing LIF showed pronounced sclerotic lesions and elevation of osteoblast numbers [88], mice injected with recombinant LIF or LIF−/− mice did not show dramatic changes in bone formation [89]. On the other hand LIF receptor −/− mice showed dramatic bone loss [90]. LIF inhibits the expression of sclerostin in osteocytes and sclerostin is a potent inhibitor of bone formation by osteoblasts [87]. Osteoclasts do not express LIF receptor or produce LIF suggesting that LIF effects on these cells at the growth plate are indirectly mediated through osteoblasts and osteocytes via induction of RANKL production [91]. In humans loss of function mutations in the LIF receptor lead to Stuve-Weidemann/Schwartz-Jampel type 2 syndrome exhibiting shortened, bowed bones consistent with decreased bone formation [92].

In human articular chondrocytes LIF expression and secretion was induced by pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL1, IL6, TNFa) and LIF administration itself induced the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and proteases involved in cartilage degradation. This suggests an important role for LIF in the progression of the inflammatory state and cartilage destruction seen in rheumatoid arthritis [90].

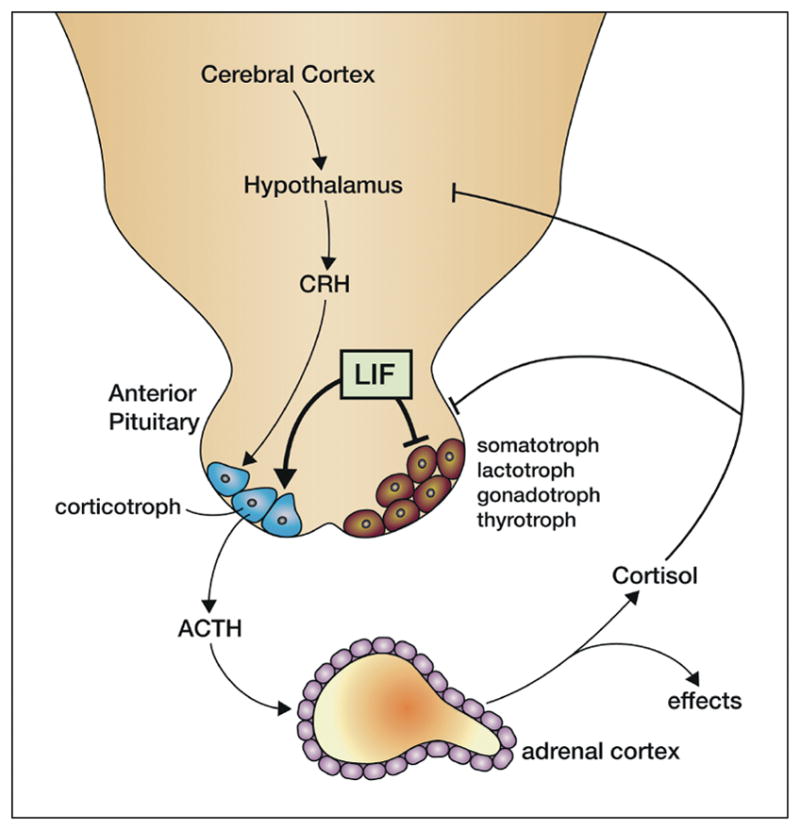

The hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis

This axis refers to the response to stress in which the hypothalamus secretes corticotropin –releasing hormone (CRH) that acts on the anterior pituitary to secrete adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) that in turn acts on the adrenal cortex to secrete glucocorticoids. The glucocorticoids have multiple effects on the immune system, digestion, energy storage/utilization and others and also feedback on the pituitary and hypothalamus to inhibit the cycle (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. LIF and the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis.

LIF acts on the anterior pituitary to enhance differentiation of precursors into corticotrophs rather than other cell fates and stimulates secretion of ACTH from corticotrophs synergistically with the cotricotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) produced by hypothalamic neurons. ACTH then acts on the adrenal cortex to secrete cortisol that has many effector actions in the stress response and also feeds back to inhibit the hypothalamic circuits and the anterior pituitary.

LIF is expressed in all species of pituitary, mostly in corticotrophs along with ACTH expression. Moreover LIF induces expression of the ACTH precursor (proopiomelanocortin) and secretion of ACTH in primary corticotrophs or cell lines, this effect being synergistic with CRH. This action is mediated by LIFRβ/gp130, requires STAT3 activation and is inhibited by SOCS3. Indeed antibodies to LIF or LIFRβ reduce the basal rate of ACTH secretion suggesting that autocrine or paracrine LIF production is required for constitutive ACTH secretion.

Other inflammatory cytokines (especially IL1β) and bacterial products (eg lipopolysaccharide, LPS) also stimulate ACTH secretion and there is some evidence that part of this response might be via induction of LIF expression. In addition the combination of LIF and IL1β leads to a synergistic increase in ACTH secretion.

LIF −/− mice do not show reduced basal ACTH levels but fail to increase ACTH in response to prolonged immobilization stress [93].

LIF inhibits cell cycle progression in a corticotroph cell line but increases ACTH secretion suggesting that LIF may act as a differentiation factor for corticotrophs. Indeed transgenic expression of LIF in the pituitary resulted in excess numbers of ACTH-positive cotricotroph cells and decreased numbers of somatotroph, lactotroph and gonadotroph cells in the pituitary and these mice suffered dwarfism and hypogonadotropism. These data suggest that LIF signalling may direct differentiation of precursor cells towards the corticotroph and away from other potential lineages [94, 95].

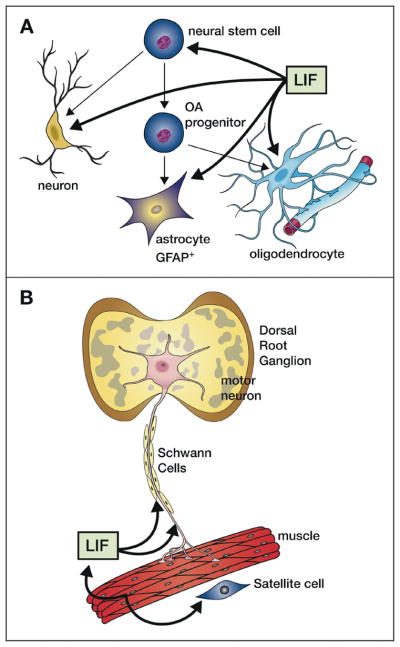

The neuromuscular system and heart

LIF was first described as a factor that could switch neurotransmitter production from catecholamine to acetylcholine in primary cultures of rat sympathetic neurons [6] and subsequently a switch from neuropeptide Y to vasoactive intestinal peptide, calcitonin gene-related peptide and substance P neuropeptides [96]. However LIF −/− mice did not show changes in sweat gland innervation profile but did reveal a failure of neurotransmitter switching after axotomy suggesting that LIF is not involved in regulating neurotransmitter plasticity during development but is involved in this process following neural trauma [97].

LIF also stimulated the development of sensory neurons in cultures of neural crest cells, a process that was augmented by co-treatment with fgf2 [98, 99] and in cultures of developing dorsal root ganglia (DRG), although the latter also required nerve growth factor (NGF) [99]. Similar results were found in nodose ganglion cultures and in all cases the requirement for different cytokines/growth factors depended on development age. It has been suggested that fgf2 may act on the earliest precursors that then become responsive to LIF for survival/differentiation and that differentiated cells then become dependent on NGF for survival. Like NGF, LIF has been shown to be retrograde transported (in a LIF receptor-dependent fashion) from the footpad and gastrocnemius muscle to the sensory neurons in the DRG and this process was dramatically increased after axotomy [100, 101]. An increase in LIF expression in injured nerve [101] again suggests that this action of LIF may not be important in development but rather in injury responses. Similarly LIF was found to promote differentiation of E10 spinal chord motor neurons [102], to be retrograde transported in motor neurons following nerve damage [101] and to reduce motor neuron loss following nerve transection [103]. An additional role of muscle-derived LIF is to control the timing of motor neuron sprouting with LIF −/− mice demonstrating premature withdrawal of synapses from neonatal muscles [104] suggesting a role for LIF in neuromuscular connectivity. Many of the effects of LIF on neural populations are also demonstrated by ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF) that shares receptor components with LIF. While there are few neurological defects in LIF−/− mice. there are synergistic losses in motor neuron function in double mutant (LIF−/−; CNTF −/−) mice [105] as well as in LIF receptor null or CNTFR null mice [106, 107].

In the brain adenoviral LIF delivery into the brains of mice has been shown to increase self-renewal of neural stem cells in the sub-ventricular zone and olfactory bulb at the expense of differentiation into neurons [108].

LIF has additional effects in neural support cells, the glia. It induces differentiation of an astrocyte progenitor cell line into mature GFAP+ astrocytes [109] and induces increased numbers of GFAP+ cells to develop from spinal cord cultures, although serum factors were also required [102]. LIF−/− mice displayed reduced numbers of GFAP+ astrocytes in the hippocampus and dentate gyrus [99] while LIF receptor null mice displayed marked reductions in GFAP+ astrocytes in the brainstem and spinal cord [110]. Similarly LIF induced production, maturation and survival of oligodendrocytes from precursor cell cultures and it has been suggested that glial cell maturation to astrocytes versus oligodendrocytes in the presence of LIF might depend on the presence of other factors such as the extracellular matrix [111]. In vivo LIF administration (via an adenovirus vector into the brain) stimulated the proliferation of oligodendrocyte precursor cells and enhanced oligodendrocyte remyelination of axons in the hippocampus after cuprizone-induced demyelination [112]. In LIF−/− mice there was reduced myelination in regions of the brain [113] and a delay in the generation of oligodendrocytes in the optic nerve [114].

LIF stimulates the proliferation of skeletal muscle precursors (myoblasts) in vitro but inhibits their differentiation into myotubes [115] and, following injury, skeletal muscle regeneration is enhanced by application of LIF in vivo [116]. LIF reduces the atrophy seen in denervated muscle and can stimulate muscle re-innervation in the rat [117]. LIF expression is increased in muscle upon exercise [118] and LIF−/− mice fail to show a hypertrophic response to muscle loading [119] and reduced muscle regeneration following injury [120]. On the other hand developmental muscle defects are not apparent in LIF−/− mice and, as for nerve cells, LIF expression is increased in damaged muscle. Thus, as for the nervous system, the major role of LIF in muscle may be in response to traumatic injury or muscle load rather than in developmental processes (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7. Neuromuscular effects of LIF.

A. LIF acts on neural stem cells to increase self-renewal and can also act to stimulate the production and survival of neurons, GFAP+ astrocytes and oligodendrocytes that sheath neural axons (glial cells). It also acts to switch neurotransmitter choice of sensory neurons (from noradrenalin to acetylcholine). B. LIF is produced by skeletal muscle under load or after damage and stimulates proliferation of satellite cells while inhibiting their fusion into myotubes. Increased LIF production in damaged muscle or in neurons can be retrograde transported along axons to the nerve body (shown for motor neurons in the dorsal root ganglion) leading to increased survival.

LIF has also been demonstrated to have effects on heart muscle, including stimulating the survival and growth of neonatal mouse cardiac ventricular myocytes [121], although it has been difficult to assess whether the effects are due to the use of a common receptor system to cardiotrophin-1. LIF pre-treatment reduced ischemia-reperfusion-induced loss of cardiomyocytes in rabbits [122] and LIF plasmid enhanced recovery in myocardial infarction in mice [123]. In both cases there was evidence that LIF induced protection against reactive oxygen species (eg by induction of superoxide dismutase) and survival pathways in cardiomyocytes (eg Akt/PI3K). It has also been proposed that LIF stimulates bone marrow–derived cardiac stem cells to home to damaged myocardium and stimulates their differentiation into endothelial cells and neovascularization [124].

The hemopoietic system

Despite its identification as a myeloid leukemia-differentiation-inducing factor, LIF has surprisingly few effects on hemopoietic cells. While it has no colony-stimulating activity on its own. it was shown to synergize with interleukin-3 (IL3) in stimulating the proliferation of human primitive blast cell colonies [125] and in the mouse it synergised with IL3 in stimulating megakaryocyte colony formation and with FLK ligand in stimulating blast colony formation. When injected into mice LIF induced elevated megakaryocyte and platelet numbers and it functionally activated platelets [126]. LIF−/− mice displayed reduced numbers of hemopoeitic stem cells (CFU-S) in the bone marrow and spleen but normal numbers of colony-forming cells in the bone marrow and a normal ability to reconstitute irradiated hosts, as well as normal numbers of circulating blood cells [127].

LIF is expressed in the thymic epithelium and is required for normal thymic architecture. LIF −/− mice show reduced responsiveness of their thymocytes (but not peripheral lymphocytes) to the mitogen concanavalin A and this appears dependent on microenvironmental production of LIF [127]. Regulatory T cells (T regs) in mouse and man were shown to produce high levels of LIF and LIF induced the production of T regs by enhancing the expression of the transcription factor Foxp3 and repressing expression of RORγt. In this way LIF appears to be tolerogenic by promoting T reg differentiation and inhibiting pro-inflammatory Th17 cell differentiation while the related cytokine IL6 has the opposite effect [128]. These effects of LIF have been suggested to be important in providing a tolerogenic environment during pregnancy and maintaining tolerance in allotransplantation. While LIF is often up-regulated in inflammatory conditions it again appears to play a protective role by inducing an acute phase response in liver and protecting against endotoxic shock by reducing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF and IL6) and increasing the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines like IL10 [129].

Cancer

Early experiments using an injected cell line over-expressing LIF showed a cachexia phenotype with loss of subcutaneous and abdominal fat [88]. Subsequently, Mori et al purified a lipoprotein lipase inhibiting activity from a melanoma cell line that caused cancer cachexia in mice and found that it was identical to LIF [7]. Other cytokines can also cause a cachexic phenotype so the role of LIF in particular tumors is unclear.

LIF (and LIFRβ) expression has been noted in many solid tumors including breast, skin colorectal and nasopharyngeal cancers. In the latter case, high circulating LIF levels correlated with tumor recurrence and radioresistance and LIF-induced radioresistance and inhibition of DNA repair was demonstrated on these cells in vitro [130]. Wu et al showed that LIF expression in colorectal cancer cells was induced by low oxygen levels and the transcription factor HIF-2α and that expression of both proteins was correlated in human specimens [131]. It was also shown that LIF negatively regulated p53 by activating the MDM2 proteolytic pathway in colorectal cancer cells thus providing a rationale for the effects of LIF on increased chemo- and radio-resistance [132]. LIF has been shown to stimulate the growth, inhibit the differentiation and induce metastasis of a variety of tumors in vitro (see eg ref [131]) but it has been difficult to prove a direct role in tumorigenesis.

Summary and outlook

As mentioned by others the name leukemia inhibitory factor is a misnomer because LIF has few effects on myeloid cells and inhibits the growth of few leukemias other than the M1 mouse myeloid leukemic cell line. In contrast LIF receptors are broadly distributed and in principle LIF has a very broad range of activities on almost all organ systems including the hemopoietic, bone remodelling, neural, muscular, endocrine and reproductive systems. Nevertheless LIF knockout mice have a rather restricted set of development defects including loss of female fertility and defects in some neurons and glial populations. Many of the effects of LIF on the other organs appear to be unrelated to development but instead represent a systemic or local response to tissue damage or injury particularly in nerves and muscles. Surprisingly LIF can also have opposite signalling outcomes depending on cell system and developmental stage. For example it is a differentiation inhibitor and maintainer of pluripotency in embryonic stem cells but an inducer of differentiation in M1 leukemia cells, osteoblasts and glia. Similarly it stimulates proliferation of DA1 cells but inhibits proliferation of corticotrophs and it can promote cell survival in some cell types while inducing apoptosis in others. The signalling pathways induced by LIF are similar in most cell types including activation of the JAK1/STAT3, PI3K/Akt and MAPK pathways. The differences in signalling outcome may in part arise from differential levels of activation of these three pathways (for example STAT3 and MAPK seem to have opposing effects on differentiation); different chromatin states that give differential gene activation to the same signal; and/or a different mileu of other cytokines and expression of cytokine receptors on different cells or at different developmental stages.

The biological effects of LIF mentioned above have prompted clinical trials for efficacy in chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy [133], platelet recovery following chemotherapy [134] and infertility in women [135] but none of these studies has produced results promising enough to pursue further. Despite the plethora of possible clinical applications (and potential unwanted effects) LIF remains to find a place in clinical practice. A more sophisticated understanding of biological redundancy, method and timing of delivery will be required to potentially improve on this situation.

Highlights.

Leukemia inhibitory factor is a highly pleiotropic cytokine

It belongs to the IL6 superfamily characterized by use of the receptor chain gp130

Despite common signalling pathways it has opposing effects on different cells

It has non-redundant effects on blastocyst implantation and pregnancy

It is involved in stress and tissue repair of bone, muscle and nerve

Acknowledgments

The authors’ original work was supported by grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council, Australia (Program Grants 461219,1016647; Fellowship Grants 637300,1078737 NAN, The Independent Research Institutes Infrastructure Scheme 361646) the Australian Research Council (Future Fellowship FT110100169 JJB), the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md (Grant RO1CA22556) and Operational Infrastructure Support grants from the State Government of Victoria. Peter Maltezos is thanked for help with the preparation of the figures.

Abbreviations

- LIF

leukemia inhibitory factor

- CNTF

ciliary neurotrophic growth factor

- CT1

cardiotrophin 1

- CLC

carditrophin-like cytokine

- JAK

Janus kinase

- STAT

Signal transducer and activator of transcription

- MAPK

Mitogen activated protein kinase

- PI(3)K

phosphatidyl inositol 3 kinase

- IL6

interleukin-6

- Gp130

glycoprotein 130

- OSM

oncostatin M

- CBM

cytokine-binding module

- ESC

embryonic stem cells

- EM

electron microscopy

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- SHP2

SH2-domain-containing phosphatase 2

- SOCS

suppressor of cytokine signaling

- PTPN11

protein tyrosine phosphatase, non-receptor type 11

- MLPLI

Melanoma-derived lipoprotein lipase inhibitor

- HILDA

Human interleukin for DA cells

- DIA

Differentiation inhibiting activity

- HSF

Hepatocyte-stimulating factor

- Kd

Equilibrium dissociation constant

- FnIII

Fibronectin III domain

- CNDF

Cholinergic neuronal differentiation factor

Biographies

Nicos Nicola obtained his PhD in protein chemistry under Sydney Leach in the Biochemistry Department at the University of Melbourne, Australia. After a short postdoctoral period at Brandeis University, USA with Gerald Fasman he returned to the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, Australia to work with Tony Burgess and Donald Metcalf on the purification of the colony-stimulating factors. He has remained at that institution for the last 38 years where he is currently co-head of the Division of Cancer and Haematology. His research interests have included cytokines, their receptors and their intracellular signalling pathways in health and disease.

Jeff Babon is a Laboratory Head at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research (Australia) and is a specialist in the field of structural biology and biochemistry. He is a graduate of Melbourne University and obtained his Ph.D at the Murdoch Institute. Jeff Babon undertook postdoctoral training at the National Institute of Medical Research (London, UK), 2000–2003, in the division of Molecular Structure and then returned to Australia in 2003 to take a position in the Structural Biology Division at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute. The group of Dr. Babon focusses on the regulation of Cytokine Signalling, in particular the inhibition of JAK/STAT signalling via the SOCS (Suppressor of Cytokine Signalling) family of proteins. He uses structural biology and biochemistry to study mechanism within these pathways to understand the role they play in haematological disease.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: NAN is an inventor on patents relating to LIF

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Gearing DP, Gough NM, King JA, Hilton DJ, Nicola NA, Simpson RJ, et al. Molecular cloning and expression of cDNA encoding a murine myeloid leukaemia inhibitory factor (LIF) The EMBO journal. 1987;6:3995–4002. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02742.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith AG, Heath JK, Donaldson DD, Wong GG, Moreau J, Stahl M, et al. Inhibition of pluripotential embryonic stem cell differentiation by purified polypeptides. Nature. 1988;336:688–90. doi: 10.1038/336688a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moreau JF, Bonneville M, Godard A, Gascan H, Gruart V, Moore MA, et al. Characterization of a factor produced by human T cell clones exhibiting eosinophil-activating and burst-promoting activities. Journal of immunology. 1987;138:3844–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baumann H, Onorato V, Gauldie J, Jahreis GP. Distinct sets of acute phase plasma proteins are stimulated by separate human hepatocyte-stimulating factors and monokines in rat hepatoma cells. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1987;262:9756–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patterson PH, Chun LL. The induction of acetylcholine synthesis in primary cultures of dissociated rat sympathetic neurons. I. Effects of conditioned medium. Developmental biology. 1977;56:263–80. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(77)90269-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patterson PH, Chun LL. The induction of acetylcholine synthesis in primary cultures of dissociated rat sympathetic neurons. II. Developmental aspects. Developmental biology. 1977;60:473–81. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(77)90144-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mori M, Yamaguchi K, Abe K. Purification of a lipoprotein lipase-inhibiting protein produced by a melanoma cell line associated with cancer cachexia. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 1989;160:1085–92. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(89)80114-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robinson RC, Grey LM, Staunton D, Vankelecom H, Vernallis AB, Moreau JF, et al. The crystal structure and biological function of leukemia inhibitory factor: implications for receptor binding. Cell. 1994;77:1101–16. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90449-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hinds MG, Maurer T, Zhang JG, Nicola NA, Norton RS. Solution structure of leukemia inhibitory factor. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1998;273:13738–45. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.22.13738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boulanger MJ, Bankovich AJ, Kortemme T, Baker D, Garcia KC. Convergent mechanisms for recognition of divergent cytokines by the shared signaling receptor gp130. Molecular cell. 2003;12:577–89. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00365-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gearing DP, Comeau MR, Friend DJ, Gimpel SD, Thut CJ, McGourty J, et al. The IL-6 signal transducer, gp130: an oncostatin M receptor and affinity converter for the LIF receptor. Science. 1992;255:1434–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1542794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boulanger MJ, Chow DC, Brevnova EE, Garcia KC. Hexameric structure and assembly of the interleukin-6/IL-6 alpha-receptor/gp130 complex. Science. 2003;300:2101–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1083901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chow D, Ho J, Nguyen Pham TL, Rose-John S, Garcia KC. In vitro reconstitution of recognition and activation complexes between interleukin-6 and gp130. Biochemistry. 2001;40:7593–603. doi: 10.1021/bi010192q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matadeen R, Hon WC, Heath JK, Jones EY, Fuller S. The dynamics of signal triggering in a gp130-receptor complex. Structure. 2007;15:441–8. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skiniotis G, Lupardus PJ, Martick M, Walz T, Garcia KC. Structural organization of a full-length gp130/LIF-R cytokine receptor transmembrane complex. Molecular cell. 2008;31:737–48. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gearing DP, Thut CJ, VandeBos T, Gimpel SD, Delaney PB, King J, et al. Leukemia inhibitory factor receptor is structurally related to the IL-6 signal transducer, gp130. The EMBO journal. 1991;10:2839–48. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07833.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu Y, Kershaw NJ, Luo CS, Soo P, Pocock MJ, Czabotar PE, et al. Crystal structure of the entire ectodomain of gp130: insights into the molecular assembly of the tall cytokine receptor complexes. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2010;285:21214–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C110.129502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stahl N, Boulton TG, Farruggella T, Ip NY, Davis S, Witthuhn BA, et al. Association and activation of Jak-Tyk kinases by CNTF-LIF-OSM-IL-6 beta receptor components. Science. 1994;263:92–5. doi: 10.1126/science.8272873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huyton T, Zhang JG, Luo CS, Lou MZ, Hilton DJ, Nicola NA, et al. An unusual cytokine:Ig-domain interaction revealed in the crystal structure of leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) in complex with the LIF receptor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:12737–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705577104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boulanger MJ, Garcia KC. Shared cytokine signaling receptors: structural insights from the gp130 system. Advances in protein chemistry. 2004;68:107–46. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3233(04)68004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hilton DJ, Nicola NA, Metcalf D. Distribution and comparison of receptors for leukemia inhibitory factor on murine hemopoietic and hepatic cells. Journal of cellular physiology. 1991;146:207–15. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041460204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hilton DJ, Nicola NA. Kinetic analyses of the binding of leukemia inhibitory factor to receptor on cells and membranes and in detergent solution. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1992;267:10238–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lupardus PJ, Skiniotis G, Rice AJ, Thomas C, Fischer S, Walz T, et al. Structural snapshots of full-length Jak1, a transmembrane gp130/IL-6/IL-6Ralpha cytokine receptor complex, and the receptor-Jak1 holocomplex. Structure. 2011;19:45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2010.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gouin F, Couillaud S, Cottrel M, Godard A, Passuti N, Heymann D. Presence of leukaemia inhibitory factor (LIF) and LIF-receptor chain (gp190) in osteoclast-like cells cultured from human giant cell tumour of bone. Ultrastructural distribution. Cytokine. 1999;11:282–9. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1998.0429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ni H, Ding NZ, Harper MJ, Yang ZM. Expression of leukemia inhibitory factor receptor and gp130 in mouse uterus during early pregnancy. Molecular reproduction and development. 2002;63:143–50. doi: 10.1002/mrd.10168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scott RL, Gurusinghe AD, Rudvosky AA, Kozlakivsky V, Murray SS, Satoh M, et al. Expression of leukemia inhibitory factor receptor mRNA in sensory dorsal root ganglion and spinal motor neurons of the neonatal rat. Neuroscience letters. 2000;295:49–53. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)01578-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams RL, Hilton DJ, Pease S, Willson TA, Stewart CL, Gearing DP, et al. Myeloid leukaemia inhibitory factor maintains the developmental potential of embryonic stem cells. Nature. 1988;336:684–7. doi: 10.1038/336684a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilks AF. Two putative protein-tyrosine kinases identified by application of the polymerase chain reaction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1989;86:1603–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.5.1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rodig SJ, Meraz MA, White JM, Lampe PA, Riley JK, Arthur CD, et al. Disruption of the Jak1 gene demonstrates obligatory and nonredundant roles of the Jaks in cytokine-induced biologic responses. Cell. 1998;93:373–83. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81166-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chung BM, Kang HC, Han SY, Heo HS, Lee JJ, Jeon J, et al. Jak2 and Tyk2 are necessary for lineage-specific differentiation, but not for the maintenance of self-renewal of mouse embryonic stem cells. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2006;351:682–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.10.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takahashi Y, Takahashi M, Carpino N, Jou ST, Chao JR, Tanaka S, et al. Leukemia inhibitory factor regulates trophoblast giant cell differentiation via Janus kinase 1-signal transducer and activator of transcription 3-suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 pathway. Molecular endocrinology. 2008;22:1673–81. doi: 10.1210/me.2008-0058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ernst M, Oates A, Dunn AR. Gp130-mediated signal transduction in embryonic stem cells involves activation of Jak and Ras/mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1996;271:30136–43. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.47.30136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Williams NK, Bamert RS, Patel O, Wang C, Walden PM, Wilks AF, et al. Dissecting specificity in the Janus kinases: the structures of JAK-specific inhibitors complexed to the JAK1 and JAK2 protein tyrosine kinase domains. Journal of molecular biology. 2009;387:219–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thoma B, Bird TA, Friend DJ, Gearing DP, Dower SK. Oncostatin M and leukemia inhibitory factor trigger overlapping and different signals through partially shared receptor complexes. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1994;269:6215–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oh H, Fujio Y, Kunisada K, Hirota H, Matsui H, Kishimoto T, et al. Activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase through glycoprotein 130 induces protein kinase B and p70 S6 kinase phosphorylation in cardiac myocytes. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1998;273:9703–10. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.16.9703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fahmi A, Smart N, Punn A, Jabr R, Marber M, Heads R. p42/p44-MAPK and PI3K are sufficient for IL-6 family cytokines/gp130 to signal to hypertrophy and survival in cardiomyocytes in the absence of JAK/STAT activation. Cellular signalling. 2013;25:898–909. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heinrich PC, Behrmann I, Haan S, Hermanns HM, Muller-Newen G, Schaper F. Principles of interleukin (IL)-6-type cytokine signalling and its regulation. Biochemical Journal. 2003;374:1–20. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hirai H, Karian P, Kikyo N. Regulation of embryonic stem cell self-renewal and pluripotency by leukaemia inhibitory factor. The Biochemical journal. 2011;438:11–23. doi: 10.1042/BJ20102152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Darnell JE, Jr, Kerr IM, Stark GR. Jak-STAT pathways and transcriptional activation in response to IFNs and other extracellular signaling proteins. Science. 1994;264:1415–21. doi: 10.1126/science.8197455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Raz R, Lee CK, Cannizzaro LA, d’Eustachio P, Levy DE. Essential role of STAT3 for embryonic stem cell pluripotency. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96:2846–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.2846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Niwa H, Burdon T, Chambers I, Smith A. Self-renewal of pluripotent embryonic stem cells is mediated via activation of STAT3. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2048–60. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.13.2048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schmitz J, Dahmen H, Grimm C, Gendo C, Muller-Newen G, Heinrich PC, et al. The cytoplasmic tyrosine motifs is full-length glycoprotein 130 have different roles in IL-6 signal transduction. Journal of Immunology. 2000;164:848–54. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.2.848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haan S, Hemmann U, Hassiepen U, Schaper F, Schneider-Mergener J, Wollmer A, et al. Characterization and binding specificity of the monomeric STAT3-SH2 domain. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:1342–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.3.1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stahl N, Farruggella TJ, Boulton TG, Zhong Z, Darnell JE, Jr, Yancopoulos GD. Choice of STATs and other substrates specified by modular tyrosine-based motifs in cytokine receptors. Science. 1995;267:1349–53. doi: 10.1126/science.7871433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Haan S, Kortylewski M, Behrmann I, Muller-Esterl W, Heinrich PC, Schaper F. Cytoplasmic STAT proteins associate prior to activation. Biochemical Journal. 2000;345:417–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Starr R, Willson TA, Viney EM, Murray LJL, Rayner JR, Jenkins BJ, et al. A family of cytokine-inducible inhibitors of signalling. Nature. 1997;387:917–21. doi: 10.1038/43206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Endo TA, Masuhara M, Yokouchi M, Suzuki R, Sakamoto H, Mitsui K, et al. A new protein containing an SH2 domain that inhibits JAK kinases. Nature. 1997;387:921–4. doi: 10.1038/43213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Naka T, Narazaki M, Hirata M, Matsumoto T, Minamoto S, Aono A, et al. Structure and function of a new STAT-induced STAT inhibitor. Nature. 1997;387:924–9. doi: 10.1038/43219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hilton DJ, Richardson RT, Alexander WS, Viney EM, Willson TA, Sprigg NS, et al. Twenty proteins containing a C-terminal SOCS box form five structural classes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95:114–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.1.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Babon JJ, Kershaw NJ, Murphy JM, Varghese LN, Laktyushin A, Young SN, et al. Suppression of cytokine signaling by SOCS3: characterization of the mode of inhibition and the basis of its specificity. Immunity. 2012;36:239–50. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kershaw NJ, Murphy JM, Liau NP, Varghese LN, Laktyushin A, Whitlock EL, et al. SOCS3 binds specific receptor-JAK complexes to control cytokine signaling by direct kinase inhibition. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20:469–76. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kershaw NJ, Laktyushin A, Nicola NA, Babon JJ. Reconstruction of an active SOCS3-based E3 ubiquitin ligase complex in vitro: identification of the active components and JAK2 and gp130 as substrates. Growth Factors. 2014;32:1–10. doi: 10.3109/08977194.2013.877005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schmitz J, Weissenbach M, Haan S, Heinrich PC, Schaper F. SOCS3 exerts its inhibitory function on interleukin-6 signal transduction through the SHP2 recruitment site of gp130. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275:12848–56. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.17.12848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Roberts AW, Robb L, Rakar S, Hartley L, Cluse L, Nicola NA, et al. Placental defects and embryonic lethality in mice lacking suppressor of cytokine signaling 3. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:9324–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161271798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Takahashi Y, Carpino N, Cross JC, Torres M, Parganas E, Ihle JN. SOCS3: an essential regulator of LIF receptor signaling in trophoblast giant cell differentiation. The EMBO journal. 2003;22:372–84. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Matsuda T, Nakamura T, Nakao K, Arai T, Katsuki M, Heike T, et al. STAT3 activation is sufficient to maintain an undifferentiated state of mouse embryonic stem cells. Embo Journal. 1999;18:4261–9. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.15.4261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Paling NRD, Wheadon H, Bone HK, Welham MJ. Regulation of embryonic stem cell self-renewal by phosphoinositide 3-kinase-dependent signaling. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279:48063–70. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406467200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Watanabe S, Umehara H, Murayama K, Okabe M, Kimura T, Nakano T. Activation of Akt signaling is sufficient to maintain pluripotency in mouse and primate embryonic stem cells. Oncogene. 2006;25:2697–707. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schaper F, Gendo C, Eck M, Schmitz J, Grimm C, Anhuf D, et al. Activation of the protein tyrosine phosphatase SHP2 via the interleukin-6 signal transducing receptor protein gp130 requires tyrosine kinase Jak1 and limits acute-phase protein expression. Biochemical Journal. 1998;335:557–65. doi: 10.1042/bj3350557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schiemann WP, Bartoe JL, Nathanson NM. Box 3-independent signaling mechanisms are involved in leukemia inhibitory factor receptor alpha- and gp130-mediated stimulation of mitogen-activated protein kinase. Evidence for participation of multiple signaling pathways which converge at Ras. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1997;272:16631–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.26.16631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Anhuf D, Weissenbach M, Schmitz J, Sobota R, Hermanns HM, Radtke S, et al. Signal transduction of IL-6, leukemia-inhibitory factor, and oncostatin M: Structural receptor requirements for signal attenuation. Journal of Immunology. 2000;165:2535–43. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.5.2535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bartoe JL, Nathanson NM. Differential regulation of leukemia inhibitory factor-stimulated neuronal gene expression by protein phosphatases SHP-1 and SHP-2 through mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent and -independent pathways. Journal of neurochemistry. 2000;74:2021–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0742021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Neel BG, Gu HH, Pao L. The ‘Shp’ing news: SH2 domain-containing tyrosine phosphatases in cell signaling. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 2003;28:284–93. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lehmann U, Schmitz J, Weissenbach M, Sobota RM, Hortner M, Friederichs K, et al. SHP2 and SOCS3 contribute to Tyr-759-dependent attenuation of interleukin-6 signaling through gp130. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278:661–71. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210552200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Burdon T, Stracey C, Chambers I, Nichols J, Smith A. Suppression of SHP-2 and ERK signalling promotes self-renewal of mouse embryonic stem cells. Developmental biology. 1999;210:30–43. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Meloche S, Vella FD, Voisin L, Ang SL, Saba-El-Leil M. Erk2 signaling and early embryo stem cell self-renewal. Cell cycle. 2004;3:241–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Forrai A, Boyle K, Hart AH, Hartley L, Rakar S, Willson TA, et al. Absence of suppressor of cytokine signalling 3 reduces self-renewal and promotes differentiation in murine embryonic stem cells. Stem cells. 2006;24:604–14. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ying QL, Wray J, Nichols J, Batlle-Morera L, Doble B, Woodgett J, et al. The ground state of embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Nature. 2008;453:519–23. doi: 10.1038/nature06968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nichols J, Chambers I, Taga T, Smith A. Physiological rationale for responsiveness of mouse embryonic stem cells to gp130 cytokines. Development. 2001;128:2333–9. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.12.2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yang J, van Oosten AL, Theunissen TW, Guo G, Silva JC, Smith A. Stat3 activation is limiting for reprogramming to ground state pluripotency. Cell stem cell. 2010;7:319–28. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Graf U, Casanova EA, Cinelli P. The Role of the Leukemia Inhibitory Factor (LIF) - Pathway in Derivation and Maintenance of Murine Pluripotent Stem Cells. Genes. 2011;2:280–97. doi: 10.3390/genes2010280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Matsui Y, Toksoz D, Nishikawa S, Nishikawa S, Williams D, Zsebo K, et al. Effect of Steel factor and leukaemia inhibitory factor on murine primordial germ cells in culture. Nature. 1991;353:750–2. doi: 10.1038/353750a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Leitch HG, Nichols J, Humphreys P, Mulas C, Martello G, Lee C, et al. Rebuilding pluripotency from primordial germ cells. Stem cell reports. 2013;1:66–78. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Stewart CL, Kaspar P, Brunet LJ, Bhatt H, Gadi I, Kontgen F, et al. Blastocyst implantation depends on maternal expression of leukaemia inhibitory factor. Nature. 1992;359:76–9. doi: 10.1038/359076a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Charnock-Jones DS, Sharkey AM, Fenwick P, Smith SK. Leukaemia inhibitory factor mRNA concentration peaks in human endometrium at the time of implantation and the blastocyst contains mRNA for the receptor at this time. Journal of reproduction and fertility. 1994;101:421–6. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.1010421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chen JR, Cheng JG, Shatzer T, Sewell L, Hernandez L, Stewart CL. Leukemia inhibitory factor can substitute for nidatory estrogen and is essential to inducing a receptive uterus for implantation but is not essential for subsequent embryogenesis. Endocrinology. 2000;141:4365–72. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.12.7855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Krishnan T, Winship A, Sonderegger S, Menkhorst E, Horne AW, Brown J, et al. The role of leukemia inhibitory factor in tubal ectopic pregnancy. Placenta. 2013;34:1014–9. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Laird SM, Tuckerman EM, Dalton CF, Dunphy BC, Li TC, Zhang X. The production of leukaemia inhibitory factor by human endometrium: presence in uterine flushings and production by cells in culture. Human reproduction. 1997;12:569–74. doi: 10.1093/humrep/12.3.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Giess R, Tanasescu I, Steck T, Sendtner M. Leukaemia inhibitory factor gene mutations in infertile women. Molecular human reproduction. 1999;5:581–6. doi: 10.1093/molehr/5.6.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.White CA, Zhang JG, Salamonsen LA, Baca M, Fairlie WD, Metcalf D, et al. Blocking LIF action in the uterus by using a PEGylated antagonist prevents implantation: a nonhormonal contraceptive strategy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:19357–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710110104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lemons AR, Naz RK. Birth control vaccine targeting leukemia inhibitory factor. Molecular reproduction and development. 2012;79:97–106. doi: 10.1002/mrd.22002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fitzgerald JS, Tsareva SA, Poehlmann TG, Berod L, Meissner A, Corvinus FM, et al. Leukemia inhibitory factor triggers activation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3, proliferation, invasiveness, and altered protease expression in choriocarcinoma cells. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology. 2005;37:2284–96. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Horita H, Kuroda E, Hachisuga T, Kashimura M, Yamashita U. Induction of prostaglandin E2 production by leukemia inhibitory factor promotes migration of first trimester extravillous trophoblast cell line, HTR-8/SVneo. Human reproduction. 2007;22:1801–9. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Robb L, Boyle K, Rakar S, Hartley L, Lochland J, Roberts AW, et al. Genetic reduction of embryonic leukemia-inhibitory factor production rescues placentation in SOCS3-null embryos but does not prevent inflammatory disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:16333–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508023102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kritikou EA, Sharkey A, Abell K, Came PJ, Anderson E, Clarkson RW, et al. A dual, non-redundant, role for LIF as a regulator of development and STAT3-mediated cell death in mammary gland. Development. 2003;130:3459–68. doi: 10.1242/dev.00578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Walker EC, McGregor NE, Poulton IJ, Solano M, Pompolo S, Fernandes TJ, et al. Oncostatin M promotes bone formation independently of resorption when signaling through leukemia inhibitory factor receptor in mice. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2010;120:582–92. doi: 10.1172/JCI40568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Metcalf D, Gearing DP. Fatal syndrome in mice engrafted with cells producing high levels of the leukemia inhibitory factor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1989;86:5948–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.15.5948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Metcalf D, Nicola NA, Gearing DP. Effects of injected leukemia inhibitory factor on hematopoietic and other tissues in mice. Blood. 1990;76:50–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sims NA, Johnson RW. Leukemia inhibitory factor: a paracrine mediator of bone metabolism. Growth factors. 2012;30:76–87. doi: 10.3109/08977194.2012.656760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Palmqvist P, Persson E, Conaway HH, Lerner UH. IL-6, leukemia inhibitory factor, and oncostatin M stimulate bone resorption and regulate the expression of receptor activator of NF-kappa B ligand, osteoprotegerin, and receptor activator of NF-kappa B in mouse calvariae. Journal of immunology. 2002;169:3353–62. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.6.3353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Dagoneau N, Scheffer D, Huber C, Al-Gazali LI, Di Rocco M, Godard A, et al. Null leukemia inhibitory factor receptor (LIFR) mutations in Stuve-Wiedemann/Schwartz-Jampel type 2 syndrome. American journal of human genetics. 2004;74:298–305. doi: 10.1086/381715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chesnokova V, Auernhammer CJ, Melmed S. Murine leukemia inhibitory factor gene disruption attenuates the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis stress response. Endocrinology. 1998;139:2209–16. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.5.6016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Akita S, Readhead C, Stefaneanu L, Fine J, Tampanaru-Sarmesiu A, Kovacs K, et al. Pituitary-directed leukemia inhibitory factor transgene forms Rathke’s cleft cysts and impairs adult pituitary function. A model for human pituitary Rathke’s cysts. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1997;99:2462–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI119430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yano H, Readhead C, Nakashima M, Ren SG, Melmed S. Pituitary-directed leukemia inhibitory factor transgene causes Cushing’s syndrome: neuro-immune-endocrine modulation of pituitary development. Molecular endocrinology. 1998;12:1708–20. doi: 10.1210/mend.12.11.0200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Patterson PH, Nawa H. Neuronal differentiation factors/cytokines and synaptic plasticity. Cell. 1993;72 (Suppl):123–37. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(05)80032-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Rao MS, Sun Y, Escary JL, Perreau J, Tresser S, Patterson PH, et al. Leukemia inhibitory factor mediates an injury response but not a target-directed developmental transmitter switch in sympathetic neurons. Neuron. 1993;11:1175–85. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90229-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Murphy M, Reid K, Hilton DJ, Bartlett PF. Generation of sensory neurons is stimulated by leukemia inhibitory factor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1991;88:3498–501. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.8.3498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Murphy M, Dutton R, Koblar S, Cheema S, Bartlett P. Cytokines which signal through the LIF receptor and their actions in the nervous system. Progress in neurobiology. 1997;52:355–78. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(97)00020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]