Abstract

The inferior colliculus (IC) receives ascending and descending information from several convergent neural sources. As such, exploring the neural pathways that converge in the IC is crucial to uncovering their multi-varied roles in the integration of auditory and other sensory information. Among these convergent pathways, the IC commissural connections represent an important route for the integration of bilateral information in the auditory system. Here, we describe the preparation and validation of a novel in vitro slice preparation for examining the functional topography and synaptic properties of the commissural and intrinsic projections in the IC of the mouse. This preparation, in combination with modern genetic approaches in the mouse, enables the specific examination of these pathways, which potentially can reveal cell-type specific processing channels in the auditory midbrain.

Keywords: inferior colliculus, commissural, GABA, inhibition, auditory, disinhibition

Introduction

The inferior colliculus (IC) is a crucial hub for auditory information processing, integrating inputs from brainstem, midbrain and cortical sources, among others (Casseday et al., 2002, Winer and Schreiner, 2005). Previous anatomical and physiological studies have identified the broad origins and synaptic properties of many of these inputs (Oliver, 1984, Winer et al., 1998, Reetz and Ehret, 1999, Malmierca et al., 2003). There is extensive convergence from intrinsic and contralateral IC sources to each of the separate IC subdivisions, the tonotopically organized central nucleus (CN) and the non-tonotopic shell nuclei: dorsal cortex (DC) and lateral nucleus (La) (Smith, 1992, Moore et al., 1998, Li et al., 1999, Saldaña and Marchán, 2005). However, many features of the functional topography of the diverse excitatory and inhibitory neural circuits in the IC remain undefined. Since the IC has unique and distinct roles in auditory processing and behavior (Torterolo et al., 1998, LeBeau et al., 2001, Malmierca et al., 2003, Malmierca et al., 2005, Bajo and King, 2012), we sought to develop an in vitro slice preparation in the mouse that maintained functional connectivity of the IC commissural and intrinsic pathways.

The assessment of the functional topography of the mouse auditory system has recently benefited from several in vitro slice preparations that maintain intact connectivity between nuclei at different levels of the auditory pathway (Cruikshank et al., 2002, Lee and Sherman, 2008, 2010, Theyel et al., 2010, Covic and Sherman, 2011, Imaizumi and Lee, 2014, Llano et al., 2014). Prior studies of the synaptic properties in the IC in vitro have generally maintained only the afferent fibers without a functional assessment of whether the afferent nuclei are also intact in the slice preparation (Smith, 1992, Moore et al., 1998, Li et al., 1999, Reetz and Ehret, 1999, Sivaramakrishnan and Oliver, 2001). Maintaining such intact connections between nuclei in a slice preparation enables the probing of the functional topography of pathways using laser-scanning photostimulation via uncaging of glutamate (Papageorgiou et al., 1999, Shepherd, 2012), yielding semi-quantitative evaluations of the functional convergence from multiple input sources (Llano and Sherman, 2009, Lee and Imaizumi, 2013, Sturm et al., 2014). In addition, the auditory slice preparations that maintain these intact connections enable assessment of the divergence of connections, using optical imaging methods that elucidate the functional divergence from their respective input sources (Llano et al., 2009, Broicher et al., 2010, Theyel et al., 2010, Hackett et al., 2011).

The functional organization of the commissural IC connections, in particular, would benefit greatly from such an in vitro slice preparation, in the same manner as recent studies of the development of functional IC intrinsic connections in the mouse have demonstrated (Sturm et al., 2014). Prior neuroanatomical studies of the commissural IC projections indicate highly topographic connections between IC nuclei in the mouse (González Hernández et al., 1986, Frisina et al., 1997, Frisina et al., 1998); however, due to the limitations of bulk IC tracer injections, precise cell-type specific determinations of commissural convergence and divergence remain unresolved (Saldaña and Marchán, 2005). Furthermore, the neurochemical identity and specificity of the commissural IC projections has only roughly been assigned by prior anatomical (Saldaña and Merchán, 1992, González-Hernández et al., 1996, Saint Marie, 1996) and electrophysiological (Smith, 1992, Chakravarty and Faingold, 1997, Moore et al., 1998, Li et al., 1999, Reetz and Ehret, 1999, Malmierca et al., 2003, Malmierca et al., 2005) studies, which indicate both excitatory and inhibitory components to the commissural pathway. Remaining to be determined are the cell-type specific origins and terminations of such commissural connections and their refinement with development (Sturm et al., 2014).

Consequently, in order to better understand the functional topography of these connections in the IC, we developed an in vitro slice preparation that maintains both commissural and intrinsic connectivity between the inferior (caudal) colliculi of the mouse. We validated the intact connectivity of this slice preparation using a combination of anatomical and physiological methods. Anatomical connectivity was assessed using anterograde tracing with DiI in the slice preparation (Lee and Imaizumi, 2013). In addition, flavoprotein autofluorescence imaging and whole-cell patch clamp to record evoked responses to laser-scanning photostimulation via uncaging of glutamate were used to physiologically assess intact connectivity in the slice (Papageorgiou et al., 1999, Llano et al., 2009, Shepherd, 2012). Furthermore, we sought to test whether this slice preparation could be utilized in conjunction with transgenic animals to identify specific cell-types for these functional measurements. Thus, we also validated this slice preparation in a transgenic mouse line with VGAT-positive neurons expressing the Venus fluorescent protein (Wang et al., 2009).

Methods

IC commissural slice preparation

To assess the functional topography of commissural and intrinsic inputs in the IC, acute slice preparations were made from juvenile mice (ages: P10–P12). Gross-anatomically, the terminology for these structures in mice and other rodents should be ‘caudal colliculus’ (de Lahunta et al., 2014), however here we will adhere to convention and utilize the term ‘inferior colliculus’, based on homology to the human structures and the widespread prevalence of this usage in the literature (Smith, 1992, Moore et al., 1998, Li et al., 1999, Reetz and Ehret, 1999). The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the Louisiana State University School of Veterinary Medicine approved these procedures. To visualize inhibitory neurons in the IC, we utilized transgenic mice that expressed the Venus fluorescent protein (developed by Dr. Atsushi Miyawaki at RIKEN, Wako, Japan) in vesicular gamma-aminobutryic acid transporter (VGAT) - positive neurons (mouse line developed and shared by permission from Dr. Yuchio Yanagawa at Gunma University and obtained from Dr. Janice R. Naegele at Wesleyan University) (Nagai et al., 2002, Wang et al., 2009).

To prepare the acute slice preparation containing both inferior colliculi and their commissural connections, animals were first deeply anesthetized using isoflurane inhalation until cessation of reflex responses. Animals were decapitated, the skull removed, and the brains quickly removed and submerged in ice cold, oxygenated, artificial cerebral spinal fluid (ACSF; in mm: 125 NaCl, 3 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 25 glucose) (Lee et al., 2013).

The brains were then blocked to preserve the commissural and intrinsic connections in the IC. This was done by first performing a parasagittal blocking cut lateral to the IC, ~3.5 mm away from the medial longitudinal fissure. During our preparation of this slice, we always performed this parasagittal block on the right hemisphere of the brain, since it resulted in an easier approach for making the subsequent blocking cut for right-handed individuals. However, we did not compare the efficiency of preserving these connections when this first blocking cut was made on the left hemisphere instead. But, based on the bilateral symmetry of these structures, we do not expect this to affect the preservation of the slice. Following the first blocking cut, the brain was then rested along the parasagittal-blocked surface.

A second blocking cut was made rostrally at a 30° dorsoventral angle (Fig. 1B), in order to set the sectioning angle for preserving the commissural connections between the inferior colliculi. In our preparation, we found that positioning the blade, such that its dorsal edge contacted the brain around bregma, resulted in a blocked surface that was sufficiently large enough to adhere to the cutting stage and sufficiently far from the inferior colliculi to not disturb their structural integrity. The rostrally-blocked surface was then affixed to a vibratome cutting stage using instant adhesive glue and sectioned at a thickness of 500 μm in ice cold ACSF. Slices containing intact connections between the inferior colliculi were then transferred to a holding chamber filled with ACSF and incubated at 32°C for 1 h. Selected slices were then transferred to a recording chamber on a modified microscope stage (Siskiyou Inc., Grants Pass, OR) that was perfused constantly with ACSF at 32°C.

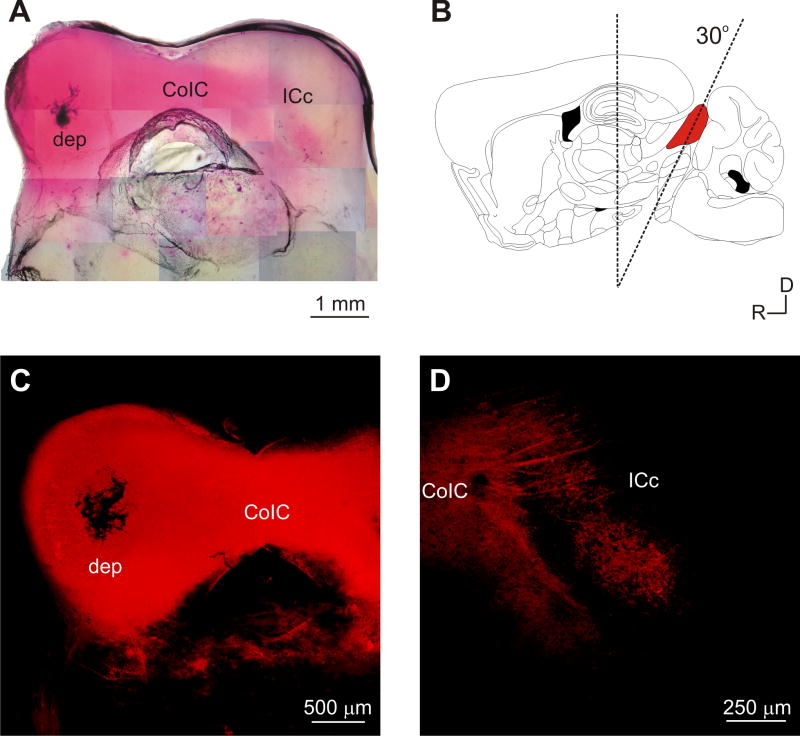

Figure 1.

The auditory inferior colliculus (IC) commissural slice. A: DiI crystal deposit (dep) in the left IC labels fibers traversing across the commissure of the inferior colliculus (CoIC) and terminating in the contralateral right IC. Photomontaged light microscope image. B: Rostral blocking angle following a parasagittal blocking cut, required for maintaining and preserving both the intrinsic and contralateral IC projections in vitro. C: Confocal image of the DiI deposit site and labeled fibers from the slice in A. D: Termination of labeled fibers in the contralateral right IC. Panel B modified from Franklin and Paxinos, 2001.

Electrophysiology and photostimulation

Whole-cell recordings were made using a Multiclamp 700B amplifier and digitized on a custom PC (ADEK Industrial Computers, Raymond, NH) using a Digidata 1440A acquisition system, pCLAMP10 software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) and the Ephus software package (Janelia Farms, Ashburn, VA).

The transferred IC slices were submerged in the recording chamber under constant bath perfusion of ACSF at 32°C and neurons were visually targeted for recording using an Olympus BX-51 microscope (Olympus America, Center Valley, PA) with a combination of DIC optics and epifluorescent illumination to visualize the VGAT-Venus expressing neurons. The microscope was equipped with a U-DPMC intermediate magnification changer (Olympus America) with 0.25x and 4x intermediate lenses, front-mounted with a Retiga-2000R camera (QImaging, Surrey, Canada) and rear-mounted with a Hitachi KP-M1AN camera (Hitachi, Tarrytown, NY). Recording pipettes with tip resistances of 4–8 MΩ were filled with either a normal intracellular solution (in mM: 135 KGluconate, 7 NaCl, 10 HEPES, 1–2 Na2ATP, 0.3 GTP, 2 MgCl2 at a pH of 7.3 obtained with KOH and osmolality of 290 mOsm obtained with distilled water) or a cesium intracellular solution (in mM: 17 Cs-gluconate, 13 CsCl, 2 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 2 Na2-ATP, 0.3 Na-GTP) was used to suppress the potassium leak current (Ik_leak) and hold the cell at depolarized potentials to facilitate detection of IPSPs. Recordings were made in current or voltage clamp modes, which were uncorrected for liquid junction potentials of ~10 mV.

Laser-scanning photostimulation (LSPS) with caged glutamate was used to map the intrinsic and contralateral IC regions eliciting EPSP/Cs in recorded IC neurons. Nitroindolinyl (NI)-caged glutamate (0.37 mM; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was added to the recirculating ACSF. Photolysis of the caged glutamate was done focally with a pulsed UV laser (DPSS Lasers, Inc., Santa Clara, CA) (Shepherd, 2012). Direct responses to LSPS glutamate uncaging were determined by latency of responses to photostimulation (<1ms). Custom software (Ephus) written in MATLAB (MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA) was used to control the photostimulation parameters and analyze the data (Suter et al., 2010). The mean EPSP/Cs elicited from three repetitions were averaged and the interpolated plots superimposed on DIC photomicrographs corresponding to the stimulation sites. Nuclear borders in the IC were determined from the DIC captured images (Lee and Sherman, 2010). The central nucleus of the IC (CN) is evident by its darker appearance relative to the surrounding lateral (La) and dorsal (DN) nuclei, appearing as a darkened, dorsoventrally tapering, teardrop shape (Lee and Sherman, 2010).

Autofluorescence Imaging

In order to assess functional connectivity in the IC commissural slice, autofluorescent imaging was used to measure metabolic activity in response to collicular stimulation by capturing green light (~510–540 nm) generated by mitochondrial flavoproteins in the presence of blue light (~450–490 nm) with a Retiga EX high-sensitivity camera (QImaging, Surrey, BC) (Theyel et al., 2010, Theyel et al., 2011). Optical recordings were taken over 12–15 sec runs and image exposure time ranged from 80 to 150 ms. All recordings were obtained at 4x magnification, acquired using Streampix 5.13 (Norpix Inc., Montreal, Quebec, Canada) and processed using custom software written to run on Matlab (Theyel et al., 2011). Baseline fluorescence was measured from the first 3 sec of the recording and changes in fluorescence measured relative to this baseline (Theyel et al., 2011). Signal profiles were analyzed using ImageJ (NIH). Defined regions of interest (ROIs) were used to measure the change in pixel intensity within or across the IC. For temporal analyses, ROIs in the center of maximal activation and the change in intensity (a slope between two consecutive frames) across image stacks (time) was plotted for each layer based on a single trial. Electrical stimulation was performed using a concentric bipolar electrode to deliver a repetitive stimulation train of 100 Hz lasting for 500 ms controlled by a Master-9 pulse generator (A.M.P.I., Jerusalem, Israel) at stimulation intensities of 50–200 μA adjusted using an A365R stimulus isolator (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL).

Anatomy

Following physiological recordings, selected slices were transferred for post-fixation to a 4% paraformaldehyde solution (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) in 10 mM phosphate buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.4). DiI crystals (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) were embedded in the left IC of connected slices under a dissecting microscope (AmScope, Irvine, CA) using a 30-gauge needle. In our experiments, the DiI placement was always in the side contralateral to the parasagittally blocked side (see above). These sections were returned to 4% paraformaldehyde/10mM PBS and incubated in the dark at room temperature for 2–3 months. Following adequate lipophilic diffusion of DiI into the commissural fibers, slices were mounted between two pieces of coverglass with Vectashield hard set mounting medium (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA). Imaging of DiI labeled fibers was obtained using a Leica TCS SP2 confocal laser-scanning microscope (Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL) housed in the microscopy center at the LSU School of Veterinary Medicine.

Immunohistochemistry

To assess the proportion of VGAT-Venus positive neurons that was GABAergic, we immunostained IC sections from the VGAT-Venus animals. Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane anesthesia followed by a lethal dose of sodium pentobarbital. Immediately following cessation of reflex responses, the mice were transcardially perfused with a fixative solution containing 4% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) in 10 mM PBS. The perfused animals were left for 1 h prior to dissection of brains, which were then post-fixed overnight in the 4% paraformaldehyde in 10 mM PBS. The following day, the brains were transferred to a 4% paraformaldehyde/30% sucrose solution in 10 mM PBS for 2–3 days for cryoprotection. The brains were blocked coronally using a clean razor blade at the rostral end of the cerebrum and were then sectioned at 50 μm using a cryostat (Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL).

The sections were then rinsed 2 times in 10 mM PBS, then placed in a solution containing 10% normal goat serum (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA)/ 0.5% Triton X-100 in 10 mM PBS for 1 h. Sections were then incubated in a 1:1000 dilution of rabbit anti-GABA antibody solution (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) at 4°C for 24 h. The next day, sections were rinsed four times in 10 mM PBS and then incubated with Alexa-Fluor 568 conjugate goat anti-rabbit IgG (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) for 2 h at 4°C. The sections were then rinsed four times in 10 mM PBS and incubated with 1–2 μM To-Pro-3 for counter staining for 15 min at room temperature. These sections were then rinsed in 10 mM PBS, mounted on gelatinized slides and coverslipped with Vectashield anti-fade medium (Vector Labs). Analysis was performed using ImageJ (NIH).

Results

To facilitate the examination of functional circuit topography in the IC of the mouse, we developed an in vitro slice preparation that maintains intact commissural and intrinsic projections between the IC of the mouse (Fig. 1). This preparation was based on an analysis of the gross anatomical organization of the IC and their commissural connections, which are dorsoventrally oriented away from the coronal slice plane in the mouse (Franklin and Paxinos, 2001) (Fig. 1B). As such, we were unable to maintain intact connectivity between hemispheres with a coronal slice, so we then systematically tested rostral dorsoventral blocking angles (in 5° increments) to determine the optimal angle for maintaining intact connectivity of the commissural projections, which was found at a 30° dorsoventral tilt (see Methods; Fig. 1B). This slice plane preserved commissural connections between the IC in our 500 μm thick preparation (Fig. 1A), with an estimated 80% success rate for obtaining connected slices, based on the ability to obtain LSPS responses in the contralateral hemisphere of the slice (see below). The ability to maintain intact connections appeared to decrease substantially (~33% success rate) with alterations to the dorsoventral tilt of just 5°.

We anatomically assessed commissural connectivity in this slice preparation using DiI to anterogradely label fibers in slices that were found to be functionally connected by autofluorescence imaging or laser-scanning photostimulation (Figs. 2, 3). Placement of DiI crystals in the IC labeled fibers that traversed the commissure of the IC (CoIC) and terminated in the contralateral IC of connected slices (Fig. 1A, C–D). The extent of contralateral IC fiber labeling from DiI crystal placement varied among individual slices, although the autofluorescence activity from contralateral IC stimulation was generally similar (Fig. 2). That is, in some instances, wider swaths of the contralateral IC would be labeled. The variable extent of such labeling may likely be due more to methodological issues associated with DiI incorporation in the fixed slice, rather than indicative of the actual extent of the anatomical terminations in each slice.

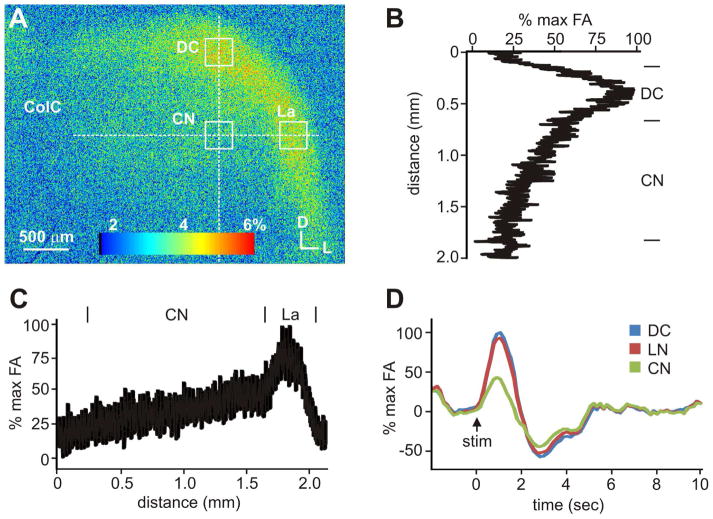

Figure 2.

Flavoprotein autofluorescence (FA) activation of the right IC following electrical stimulation of the contralateral left IC demonstrates intact functional connectivity of the commissural connections in vitro. A: Autofluorescence image of the right IC at maximal FA. B: Profile of FA responses along the dorsoventral axis as a vertical broken line in A. C: Spatial profile of FA responses across the mediolateral axis as a horizon broken line in A. D: Time course of FA response in the dorsal (DN), lateral (La) and central (CN) nuclei. Representative ROIs indicated by boxes in A. Traces depict results from single trials.

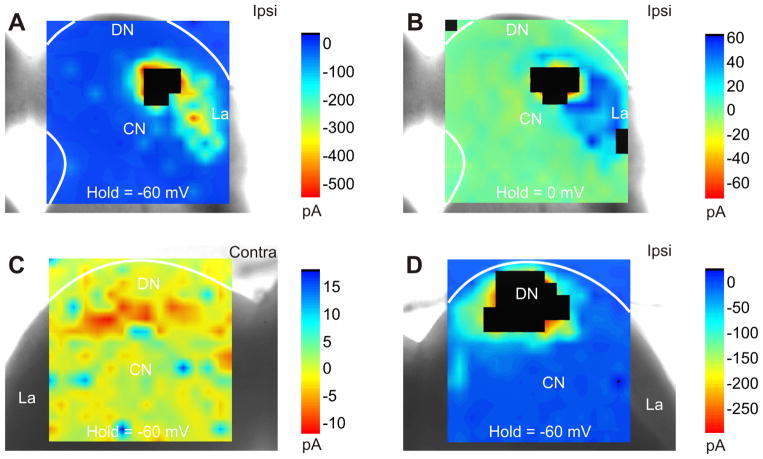

Figure 3.

Functional topography of IC neurons revealed using laser-scanning photostimulation with uncaging of glutamate of intrinsic and contralateral excitatory and inhibitory projections. A–B: Intrinsic excitatory (A) and inhibitory (B) projections originate from similar functional topographic domains. Voltage-clamp recordings using a Cs+-intracellular solution to hold neuron at −60 mV and 0 mV for isolating EPSCs and IPSCs, respectively. C–D: Excitatory intrinsic and contralateral inputs. Voltage clamp recordings using a K+-intracellular solution to hold cell at −60 mV. Commissural excitatory projections converge from a homotopic region in the contralateral IC.

We also assessed whether functionally intact connections were maintained in this slice preparation by imaging flavoprotein autofluorescence in response to stimulation of the contralateral IC (Fig. 2). A concentric bipolar stimulating electrode was placed in the central nucleus (CN) of the left IC and the evoked autofluorescence activity in the right IC imaged using a cooled CCD camera (Fig. 2A). Following electrical stimulation of the left IC, autofluorescence activity in the right IC increased, peaking ~1 s following stimulation, and subsequently returning to baseline after ~5 s following stimulation (Fig. 2D). Interestingly, in all connected cases, the observed elicited autofluorescence activity in the surrounding shell nuclei of the IC, i.e. the lateral (La) and dorsal (DN) nuclei, was nearly 2-fold greater than in the central nucleus (Fig. 2B–D). Functional connectivity assessed in this manner indicated that this slice angle was highly reliable in maintaining intact connectivity, with ~80% of prepared slices exhibiting autofluorescent activity in the connected slice. Overall, these results indicated that intact commissural connections were maintained in this slice preparation.

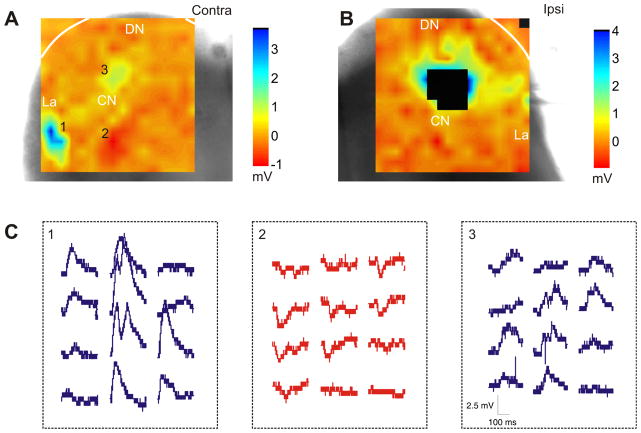

In order to further assess the connectivity of this slice, we recorded from neurons in each of the main subdivision of the IC using whole-cell patch clamp. We measured the elicited postsynaptic responses in recorded neurons to laser-scanning photostimulation via glutamate uncaging (LSPS) of either the ipsilateral or contralateral IC (Fig. 3). We have previously demonstrated that this method only activates neuronal cell bodies within (~50 μm) of the soma in the IC and the elicited postsynaptic responses only result from stimulation of intact neuronal connections (Lee and Sherman, 2010). By holding the neuron respectively at hyperpolarized (−70 mV) and depolarized (0 mV) potentials, we found that LSPS of the ipsilateral IC yields significant intrinsic excitatory (Figs. 3A,D, 4B) and inhibitory (Fig. 3B) responses that are generally overlapping, indicative of intact connectivity in the slice. Moreover, stimulation of the contralateral IC also yields significant excitatory (Figs. 3C, 4A,C) and inhibitory (Fig. 4A,C) inputs, although sometimes from different topographic loci (Fig. 4A), indicating that the slice preserves such connections.

Figure 4.

Distributed functional topography to a VGAT-positive neuron from intrinsic and commissural collicular projections. A–B: Laser-scanning photostimulation of contralateral (A) and ipsilateral (B) inputs. Current-clamp recording with a Cs+-intracellular solution. C: Representative PSP traces from the contralateral regions indicated in A.

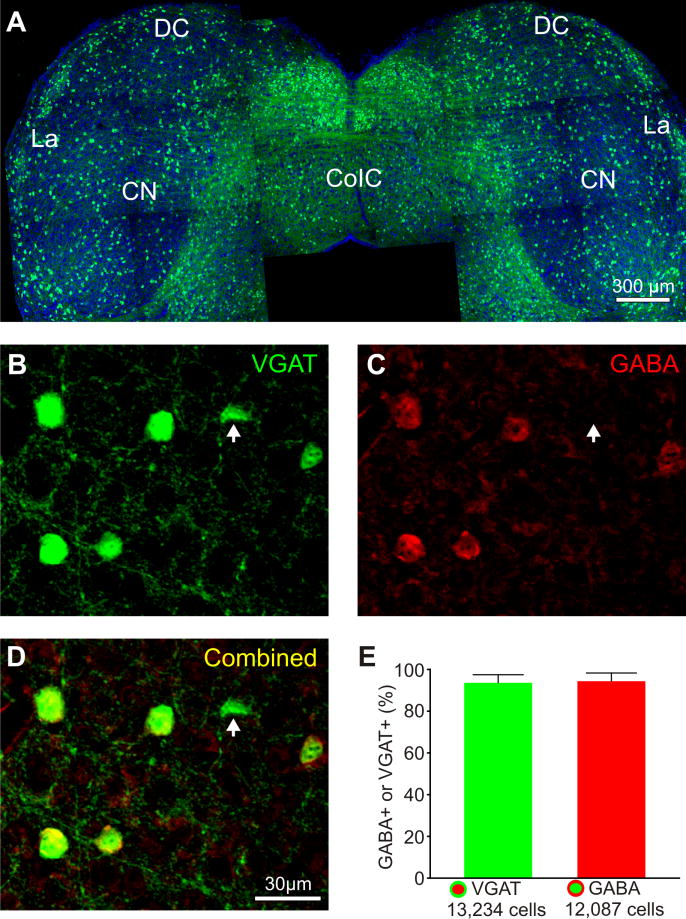

Moreover, in order to assess the utility of this slice preparation for examining the functional topography of IC connections to specific neuronal cell types, we sought to examine whether functional connections were preserved in the slice to the IC GABAergic inhibitory neurons (Fig. 5). To assess this, we employed a transgenic mouse line that expressed the Venus-fluorescent protein in VGAT-positive neurons (see Methods) (Nagai et al., 2002, Wang et al., 2009). This transgenic mouse line enabled the on-line visualization and targeting of GABAergic neurons for whole-cell recordings in the slice preparation (Fig. 4). In order to first assess the degree of Venus expression in GABAergic neurons, we immunostained sections from the IC for GABA and assessed the proportion of double-labeled neurons. Both Venus-positive and GABA-positive neurons were readily distinguished from one another (Fig. 5B,C), as were the double-labeled neurons (Fig. 5D). We found that nearly all VGAT-positive neurons were GABAergic, and, not surprisingly, that nearly all GABAergic neurons were also VGAT-positive (Fig. 5E). In addition, we also observed prominent VGAT-Venus labeled fibers traversing the CoIC (Fig. 5A), indicative of a prominent inhibitory projection crossing the CoIC, which was also observed physiologically (Fig. 4A). These results indicated that this transgenic strain accurately labels and identifies GABAergic inhibitory neurons for such cell-type specific assessments of functional topography in our slice preparation.

Figure 5.

Characterization of inhibitory neuronal populations in the IC of the VGAT-Venus transgenic mouse. A: VGAT positive neurons and commissural fibers. Blue is To-Pro-3 counter staining. B–D: Overlap of VGAT (green) and GABA (red) positive neurons. E: Percent overlap of VGAT or GABA positive cells.

As noted above, we physiologically assessed whether functional topographic projections were maintained to the VGAT-Venus positive neurons in the slice preparation (Fig. 4). We recorded using whole-cell patch clamp from VGAT-Venus positive neurons and then used LSPS to stimulate the contralateral and ipsilateral IC. We found that excitatory and inhibitory postsynaptic responses could be elicited by LSPS in both the ipsilateral and contralateral IC (Fig. 4C, E). The commissural and intrinsic IPSPs recorded from VGAT-positive neurons suggest the presence of both local and long-range disinhibitory circuitry in the IC, whose distribution and function remain to be elucidated. These results indicate that functional connectivity of IC circuitry to the VGAT-Venus positive neurons in the IC is maintained in the slice preparation using this transgenic mouse strain and the potential utility of this approach for examining cell-type specific functional topographies in the IC.

Discussion

We developed an in vitro slice preparation that maintains intact IC commissural and intrinsic neural pathways, as validated using anterograde tracing in the slice preparation and physiologically using autofluorescence imaging and laser-scanning photostimulation via uncaging of glutamate. This IC commissural slice preparation complements the growing number of preparations that maintain intact connectivity among central auditory structures in an acute in vitro slice (Cruikshank et al., 2002, Lee and Sherman, 2008, 2010, Theyel et al., 2010, Covic and Sherman, 2011, Llano et al., 2014). Our validation of the connectivity of this slice preparation used several complementary neuroanatomical and electrophysiological methods (Figs. 1–5). As such, aspects of the functional organization of synaptic connectivity across multiple levels of the central auditory pathway can now be elucidated using modern slice physiological approaches (Imaizumi and Lee, 2014).

Our slice preparation in the mouse complements prior studies that have investigated these pathways using in vitro physiological approaches in the rat (Smith, 1992, Li et al., 1999), mouse (Reetz and Ehret, 1999), and gerbil (Moore et al., 1998). Many of the synaptic properties of commissural IC fibers have been examined using electrical stimulation to demonstrate both excitatory and inhibitory commissural IC synapses (Smith, 1992, Moore et al., 1998, Li et al., 1999, Reetz and Ehret, 1999). By maintaining intact connections in the IC commissural pathway, our preparation now enables extended investigations of the functional topography of these excitatory and inhibitory inputs with laser-scanning photostimluation via glutamate uncaging. In this regard, our initial assessment of the functional topography of intrinsic collicular projections are in agreement with recent comprehensive studies of the development of the intrinsic IC connections in the mouse, which have shown overlapping excitatory and inhibitory domains (Sturm et al., 2014). The commissural collicular projections also appear to receive excitatory and inhibitory inputs, with at least one source of excitatory inputs originating from a homotopic contralateral collicular locus, in agreement with neuroanatomical studies (Schweizer, 1981, Ross et al., 1988, Malmierca et al., 1995, Cant, 2013).

Our results also demonstrated functional commissural connectivity of our slice preparation using the optical imaging method of flavoprotein autofluorescence activation (Shibuki et al., 2003, Theyel et al., 2011). Interestingly, we noted consistently stronger activation in the surrounding nuclei of the IC than in the central nucleus of the IC, which is unlikely to be a result of anatomical differences in proportional strength of the commissural pathways innervating these regions (Saldaña and Marchán, 2005). More likely, the varied nature of the autofluorescence signal, which results from different pre- and postsynaptic elements, as well as potentially glial sources, may underlie these nuclear signal differences (Husson and Issa, 2009). Regardless, the mechanistic underpinnings of these nuclear FA difference remains to be resolved.

A potential caveat with this slice preparation is that we have particularly focused on developing and validating it for juvenile mice that are developmentally around hearing onset, largely due to technical limitations of visibility for whole-cell recordings in slices from older animals and the somewhat smaller brain size of young animals, permitting intact connections to be maintained more readily (Lee and Sherman, 2008, 2010). Such limitations naturally gives rise to concerns of whether the functional organization assessed in juvenile mice are applicable to adults and whether similar conditions also preserve the IC commissural connections in the adult due to maturation of structural geometries. Indeed, analysis of intrinsic IC connections during development in the mouse demonstrate profound changes for excitatory and inhibitory circuits (Sturm et al., 2014), possibly due to developmental refinements of axonal arbors or alterations to synaptic properties. Consequently, potential modifications for preserving these connections in older animals may likely be required and suitable caveats for the interpretation of data obtained in juvenile animals must be adhered. Nevertheless, all of these concerns are not a unique problem endemic to this particular slice preparation, as most other slice preparations in the mouse have also been prepared primarily with juvenile animals (Cruikshank et al., 2002, Lee and Sherman, 2008, 2010, Theyel et al., 2010, Covic and Sherman, 2011, Lee and Imaizumi, 2013, Llano et al., 2014). Regardless, this intact slice preparation maintains some advantage over optogenetic methods for examining functional topography in vitro (Lee et al., 2013), among them the ability to map excitatory and inhibitory connections using laser-scanning photostimulation via glutamate uncaging (Shepherd, 2012), as demonstrated recently for the intrinsic connections of the mouse IC (Sturm et al., 2014).

Moreover, we also validated this slice preparation in the VGAT-Venus transgenic mouse line (Nagai et al., 2002, Wang et al., 2009). Our initial characterization of this preparation using this mouse line demonstrates that the VGAT-positive IC neurons over 95% overlap with GABA-positive IC neurons, indicating that they largely identify GABAergic inhibitory neurons in the IC. The general distribution of VGAT-positive labeling in the IC also matched that from related studies in the mouse (Ono et al., 2005, Choy Buentello et al., 2015). Our initial characterization of functional inputs to these VGAT-positive neurons suggests a combination of excitatory and inhibitory projections from both intrinsic and commissural sources. Further assessment of specific functional circuitry differences in specifically labeled cell-types using this slice preparation in transgenic animals may help unravel the varied physiological properties observed in vivo, which support the diverse IC roles in audition.

Highlights.

Auditory commissural connections are preserved in a novel in vitro slice preparation.

Functional topography can be assessed using laser-scanning photostimulation.

Inhibitory commissural circuitry can be analyzed using VGAT-Venus transgenic mice

Acknowledgments

We thank X. Wu for assistance with confocal microscopy and Sherry Ring for histology assistance. pCS2-Venus was developed by Dr. Atsushi Miyawaki at Brain Science Institute, Riken, Wako, Japan. This work was supported by NIH/NIDCD grant R03 DC 11361, SVM USDA CORP grant LAV3300 and 3487, Louisiana Board of Regents RCS grant RD-A-09, Action on Hearing Loss Grant (F42), and the American Hearing Research Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bajo VM, King AJ. Cortical modulation of auditory processing in the midbrain. Front Neural Circuits. 2012;6:114. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2012.00114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broicher T, Bidmon HJ, Kamuf B, Coulon P, Gorji A, Pape HC, Speckmann EJ, Budde T. Thalamic afferent activation of supragranular layers in auditory cortex in vitro: a voltage sensitive dye study. Neuroscience. 2010;165:371–385. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cant NB. Patterns of convergence in the central nucleus of the inferior colliculus of the Mongolian gerbil: organization of inputs from the superior olivary complex in the low frequency representation. Front Neural Circuits. 2013;7:29. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2013.00029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casseday JH, Fremouw T, Covey E. The inferior colliculus: A hub for the central auditory system. In: Oertel D, et al., editors. Springer Handbook of Auditory Research, Volume 15: Integrative Functions in the Mammalian Auditory Pathway. Vol. 15. New York: Springer; 2002. pp. 238–295. [Google Scholar]

- Chakravarty DN, Faingold CL. Aberrant neuronal responsiveness in the genetically epilepsy-prone rat: acoustic responses and influences of the central nucleus upon the external nucleus of inferior colliculus. Brain Res. 1997;761:263–270. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00331-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choy Buentello D, Bishop DC, Oliver DL. Differential distribution of GABA and glycine terminals in the inferior colliculus of rat and mouse. J Comp Neurol. 2015 doi: 10.1002/cne.23810. doi:10:1002/cne.23810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covic EN, Sherman SM. Synaptic properties of connections between the primary and secondary auditory cortices in mice. Cereb Cortex. 2011;21:2425–2441. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruikshank SJ, Rose HJ, Metherate R. Auditory thalamocortical synaptic transmission in vitro. J Neurophysiol. 2002;87:361–384. doi: 10.1152/jn.00549.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lahunta A, Glass E, Kent M. Veterinary neuroanatomy and clinical neurology. St. Louis: Elsevier; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin KBJ, Paxinos G. The mouse brain in stereotaxic coordinates. 2. New York: Academic Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Frisina RD, Walton JP, Lynch-Armour MA, Byrd JD. Inputs to a physiologically characterized region of the inferior colliculus of the young adult CBA mouse. Hear Res. 1998;115:61–81. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(97)00176-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisina RD, Walton JP, Lynch-Armour MA, Klotz DA. Efferent projections of a physiologically characterized region of the inferior colliculus of the young adult CBA mouse. J Acoust Soc Am. 1997;101:2741–2753. doi: 10.1121/1.418562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González Hernández TH, Meyer G, Ferres-Torres R. The commissural interconnections of the inferior colliculus in the albino mouse. Brain Res. 1986;368:268–276. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90571-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Hernández T, Mantolán-Sarmiento B, González-González B, Pérez-González H. Sources of GABAergic input to the inferior colliculus of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1996;372:309–326. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960819)372:2<309::AID-CNE11>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackett TA, Barkat TR, O’Brien BM, Hensch TK, Polley DB. Linking topography to tonotopy in the mouse auditory thalamocortical circuit. J Neurosci. 2011;31:2983–2995. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5333-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husson TR, Issa NP. Functional Imaging with Mitochondrial Flavoprotein Autofluorescence: Theory, Practice, and Applications. In: Frostig RD, editor. In Vivo Optical Imaging of Brain Function. 2. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imaizumi K, Lee CC. Frequency transformation in the auditory lemniscal thalamocortical system. Front Neural Circuits. 2014;8:75. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2014.00075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBeau FE, Malmierca MS, Rees A. Iontophoresis in vivo demonstrates a key role for GABA(A) and glycinergic inhibition in shaping frequency response areas in the inferior colliculus of guinea pig. J Neurosci. 2001;21:7303–7312. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-18-07303.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CC, Imaizumi K. Functional convergence of thalamic and intinsic inputs in cortical layers 4 and 6. Neurophysiol. 2013;45:396–406. doi: 10.1007/s11062-013-9385-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CC, Lam YW, Imaizumi K, Sherman SM. Laser-scanning photostimulation of optogenetically targeted forebrain circuits. J Vis Exp. 2013;82:e50915. doi: 10.3791/50915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CC, Sherman SM. Synaptic properties of thalamic and intracortical intputs to layer 4 of the first- and higher-order cortical areas in the auditory and somatosensory systems. J Neurophysiol. 2008;100:317–326. doi: 10.1152/jn.90391.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CC, Sherman SM. Topography and physiology of ascending streams in the auditory tectothalamic pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:372–377. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907873107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Evans MS, Faingold CL. Synaptic response patterns of neurons in the cortex of rat inferior colliculus. Hear Res. 1999;137:15–28. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(99)00129-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llano DA, Sherman SM. Differences in intrinsic properties and local network connectivity of identified layer 5 and layer 6 adult mouse auditory corticothalamic neurons support a dual corticothalamic projection hypothesis. Cereb Cortex. 2009;2009:2810–2826. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llano DA, Slater BJ, Lesicko AM, Stebbings KA. An auditory colliculothalamocortical brain slice preparation in mouse. J Neurophysiol. 2014;111:197–207. doi: 10.1152/jn.00605.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llano DA, Theyel BB, Mallik AK, Sherman SM, Issa NP. Rapid and sensitive mapping of long-range connections in vitro using flavoprotein autofluorescence imaging combined with laser photostimulation. J Neurophysiol. 2009;101:3325–3340. doi: 10.1152/jn.91291.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmierca MS, Hernández O, Falconi A, Lopez-Poveda EA, Merchán M, Rees A. The commissure of the inferior colliculus shapes frequency response areas in rat: an in vivo study using reversible blockade with microinjection of kynurenic acid. Exp Brain Res. 2003;153:522–529. doi: 10.1007/s00221-003-1615-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmierca MS, Hernández O, Rees A. Intercollicular commissural projections modulate neuronal responses in the inferior colliculus. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21:2701–2710. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmierca MS, Rees A, Le Beau FEN, Bjaalie JG. Laminar organization of frequency-defined local axons within and between the inferior colliculi of the guinea pig. J Comp Neurol. 1995;357:124–144. doi: 10.1002/cne.903570112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore DR, Kotak VC, Sanes DH. Commissural and lemniscal synaptic input to the gerbil inferior colliculus. J Neurophysiol. 1998;80:2229–2236. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.5.2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai T, Ibata K, Park ES, Kubota M, Mikoshiba K, Miyawaki A. A variant of yellow fluorescent protein with fast and efficient maturation for cell-biological applications. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:87–90. doi: 10.1038/nbt0102-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver DL. Dorsal cochlear nucleus projections to the inferior colliculus in the cat: a light and electron microscopic study. J Comp Neurol. 1984;224:155–172. doi: 10.1002/cne.902240202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono M, Yanagawa Y, Koyano K. GABAergic neurons in inferior colliculus of the GAD67-GFP knock-in mouse: Electrophysiological and morphological properties. Neurosci Res. 2005;51:475–492. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2004.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papageorgiou G, Odgen DC, Barth A, Corrie JET. Photorelease of carboxylic acids from 1-acyl-7-nitroindolines in aqeuous solution: rapid and efficient photorelease of L-glutamate. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:6503–6504. [Google Scholar]

- Reetz G, Ehret G. Inputs from three brainstem sources to identified neurons of the mouse inferior colliculus slice. Brain Res. 1999;816:527–543. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)01230-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross LS, Pollak GD, Zook JM. Origin of ascending projections to an isofrequency region of the mustache bat’s inferior colliculus. J Comp Neurol. 1988;270:488–505. doi: 10.1002/cne.902700403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saint Marie RL. Glutamatergic connections of the auditory midbrain: selective uptake and axonal transport of D-[3H]aspartate. J Comp Neurol. 1996;373:255–270. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960916)373:2<255::AID-CNE8>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña E, Marchán MA. Intrinsic and commissural connections of the inferior colliculus. In: Winer JA, Schreiner CE, editors. The inferior colliculus. New York: Springer; 2005. pp. 155–182. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña E, Merchán MA. Intrinsic and commissural connections of the rat inferior colliculus. J Comp Neurol. 1992;319:417–437. doi: 10.1002/cne.903190308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweizer H. The connections of the inferior colliculus and the organization of the brainstem auditory system in the greater horseshoe bat (Rhinolophus ferrumequinum) J Comp Neurol. 1981;201:25–49. doi: 10.1002/cne.902010104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd GM. Circuit mapping by ultraviolet uncaging of glutamate. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2012;2012:998–1004. doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot070664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibuki K, Hishida R, Murakami H, Kudoh M, Kawaguchi T, Watanabe M, Watanabe S, Kouuchi T, Tanaka R. Dynamic imaging of somatosensory cortical activity in the rat visualized by flavoprotein autofluorescence. J Physiol. 2003;549(Pt 3):919–927. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.040709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivaramakrishnan S, Oliver DL. Distinct K currents result in physiologically distinct cell types in the inferior colliculus of the rat. J Neurosci. 2001;21:2861–2877. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-08-02861.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PH. Anatomy and physiology of multipolar cells in the rat inferior collicular cortex using the in vitro brain slice technique. J Neurosci. 1992;12:3700–3715. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-09-03700.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturm J, Nguyen T, Kandler K. Development of intrinsic connectivity in the central nucleus of the mouse inferior colliculus. J Neurosci. 2014;34:15032–15046. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2276-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suter BA, O’Connor T, Iyer V, Petreanu LT, Hooks BM, Kiritani T, Svoboda K, Shepherd GM. Ephus: multipurpose data acquisition software for neuroscience experiments. Front Neural Circuits. 2010;4:100. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2010.00100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theyel BB, Lee CC, Sherman SM. Specific and nonspecific thalamocortical connectivity in the auditory and somatosensory thalamocortical slices. Neuroreport. 2010;21:861–864. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e32833d7cec. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theyel BB, Llano DA, Issa NP, Mallik AK, Sherman SM. In vitro imaging using laser photostimulation with flavoprotein autofluorescence. Nat Protoc. 2011;6:502–508. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torterolo P, Zurita P, Pedemonte M, Velluti RA. Auditory cortical efferent actions upon inferior colliculus unitary activity in the guinea pig. Neurosci Lett. 1998;249:172–176. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00367-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Kakizaki T, Sakagami H, Saito K, Ebihara S, Kato M, Hirabayashi M, Saito Y, Furuya N, Yanagawa Y. Fluorescent labeling of both GABAergic and glycinergic neurons in vesicular GABA transporter (VGAT)–Venus transgenic mouse. Neuroscience. 2009;164:1031–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winer JA, Larue DT, Diehl JJ, Hefti BJ. Auditory cortical projections to the cat inferior colliculus. J Comp Neurol. 1998;400:147–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winer JA, Schreiner CE, editors. The Inferior Colliculus. New York: Springer; 2005. [Google Scholar]