Abstract

Background

More effective approaches are needed to enhance drinking and other health behavior (e.g., smoking) outcomes of alcohol brief intervention (BI). Young adult heavy drinkers often engage in other health risk behaviors and show sensitivity to alcohol’s stimulating and rewarding effects, which predicts future alcohol-related problems. However, standard alcohol BIs do not address these issues. The current pilot study tested the utility of including feedback on alcohol response phenotype to improve BI outcomes among young adult heavy drinkers who smoke (HDS).

Methods

Thirty-three young adult (M ± SD age = 23.8 ± 2.1 years) HDS (8.7 ± 4.3 binge episodes/month; 23.6 ± 6.3 smoking days/month) were randomly assigned to standard alcohol BI (BI-S; n = 11), standard alcohol BI with personalized alcohol response feedback (BI-ARF; n = 10), or a health behavior attention control BI (AC; n = 11). Alcohol responses (stimulation, sedation, reward, and smoking urge) for the BI-ARF were recorded during a separate alcohol challenge session (0.8 g/kg). Outcomes were past-month drinking and smoking behavior assessed at 1- and 6-months post-intervention.

Results

At 6-month follow-up, the BI-ARF produced significant reductions in binge drinking, alcohol-smoking co-use, drinking quantity and frequency, and smoking frequency, but not maximum drinks per occasion, relative to baseline. Overall, the BI-ARF produced larger reductions in drinking/smoking behaviors at follow-up than did the BI-S or AC.

Conclusions

Including personalized feedback on alcohol response phenotype may improve BI outcomes for young adult HDS. Additional research is warranted to enhance and refine this approach in a broader sample.

Keywords: brief intervention, alcohol response, young adult, binge drinking, smoking

1. INTRODUCTION

In the United States, rates of binge drinking (i.e., consuming ≥5 drinks in an occasion for men or ≥4 for women) are highest among young adults age 18–29 years, placing this subgroup at increased risk for negative alcohol-related consequences including sexual misconduct, accidents, injury, and premature death (Abbey et al., 2001; Schoenborn et al., 2013). As young adults may not be interested in or appropriate for more intensive alcohol treatments, brief interventions (BIs) have been developed as time-limited (2–4 sessions) and cost-effective early interventions designed to mitigate future hazardous drinking and related consequences. Standard alcohol BIs, such as the Brief Alcohol Screening and Intervention for College Students protocol (BASICS; Dimeff et al., 1999), feature several main elements including comparison of one’s drinking to age-matched norms, feedback on alcohol harm and consequences, and education on practical techniques for drinking reduction. BASICS and other related alcohol BIs are modestly effective at reducing overall alcohol consumption compared to no treatment, alcohol education, or brief advice (ds = 0.18–0.43; Vasilaki et al., 2006) with similar effects for binge drinking (d = 0.25; Carey et al., 2006).

Given these relatively modest effect sizes, efforts are underway to improve and expand upon the scope of alcohol BI to reduce binge drinking and other risky health behaviors in young adults. These initiatives include providing additional educational materials, enhancing alternative non-drinking behaviors, and promoting other health behaviors, such as sleep quality and duration (Fucito et al., 2014; Murphy et al., 2012). Of note, smoking is not included in traditional alcohol BI despite data showing that approximately 50% of young adult heavy-drinkers also smoke (Weitzman and Chen, 2005), most often during drinking episodes (McKee et al., 2004). In laboratory-based studies, we have shown that heightened alcohol stimulation and reward in young binge drinkers prospectively predicted future alcohol-related problems in early middle adulthood (King et al., 2011, 2014). We and other investigators have also shown that alcohol acutely increases smoking urge (King and Epstein, 2005; Sayette et al., 2005), which may perpetuate comorbid use of these substances and increase health risks such as cancer, pulmonary, and cardiovascular disease (Negri et al., 1993; Pelucchi et al., 2006; Prabhu et al., 2014). However, feedback on smoking urge or alcohol response phenotype is not included in BASICS or other standard alcohol BIs. The potential importance of including alcohol response into BI has been recently highlighted by Schuckit and colleagues in their work showing that college students assessed for low sensitivity to alcohol’s intoxicating and impairing effects, compared with those students with high sensitivity to these alcohol effects, demonstrated lower maximum drinks per occasion after viewing a video-based educational prevention module geared to this response type (Schuckit et al., 2015). Given the prospective role of alcohol responses to future drinking problems, measuring and providing feedback on one’s response phenotype may improve outcomes of alcohol BI in young adults with hazardous drinking and smoking.

In sum, there is a need to enhance and improve outcomes with standard alcohol BI by incorporating novel intervention elements, and to reach drinkers who engage in other high-risk behaviors, such as smoking. In the present pilot study, we randomized non treatment-seeking young adult heavy (binge) drinkers who smoke (HDS) to one of three BI conditions: a standard alcohol BI, a standard alcohol BI with personalized feedback on alcohol response, and an attention control group. We hypothesized that adding personalized feedback on alcohol responses would produce greater reductions in drinking quantity, frequency, binge drinking, and alcohol-smoking co-use at 1- and 6-months after the intervention compared with the other two conditions.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.1 Participants

Young adult heavy drinkers who smoke (HDS) were recruited from online advertisements. Screening included online questionnaires assessing demographics and general health history, as well as the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (Babor et al., 2001), Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (Heatherton et al., 1991), and the Online Timeline Follow-back (O-TLFB; Rueger et al., 2012) for past month alcohol and cigarette use. Inclusion criteria were age between 21–29 years, having no major medical or psychiatric disorders, not seeking treatment for alcohol or tobacco use, and engaging in 1–5 binge alcohol drinking episodes weekly with 10–40 drinks consumed per week, consistent with prior investigations (King et al., 2011). We recruited light- or nondaily-smoking young adults (10–70 cigarettes/week) as these individuals smoke most often during drinking episodes (McKee et al., 2004).

2.2 Procedure

Eligible participants (N=33) were randomly assigned to one of three conditions: standard alcohol BI (BI-S; n = 11), standard alcohol BI with personalized alcohol response feedback (BI-ARF; n = 10), or an attention control group BI (AC; n = 11). Each group received two 20–30 minute BI sessions separated by at least 24 hours (M±SD = 5.6 ± 4.3 days). In the BI-S group, participants completed measures assessing current desire to change smoking and drinking behavior (anchored 0 = “no desire” and 10 = “strongest desire”) and alcohol-related consequences (Brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire; Kahler et al., 2005), and then attended BI sessions in which they received feedback on quantity/frequency of alcohol use and alcohol-related problems relative to age-matched norms, education on low-risk drinking and potential harms of continued binge drinking, and motivational enhancement to change drinking behavior and goal setting (Dimeff et al., 1999). In the BI-ARF group, measures and intervention sessions were identical to the BI-S group, but with the addition of an alcohol response session (see below) prior (M±SD = 4.1 ± 3.5 days) to the first BI session. Data acquired from that session were incorporated via graphical feedback and discussion of the associations between alcohol responses and future risk for alcohol problems (King et al., 2011, 2014). Specifically, participants received feedback with individual graphs of their responses to alcohol (stimulation, sedation, liking, and wanting) along the breath alcohol curve (BrAC) and whether this response pattern reflected how they typically respond to alcohol. This was then integrated in a discussion that not all drinkers are on the “same playing field” with prior research indicating that those who show more sensitivity to alcohol’s positive and rewarding effects and less sensitivity to sedative effects as young adults were more likely to experience future alcohol-related consequences (King et al., 2011; Schuckit and Smith, 1996). The discussion also included information on how alcohol, particularly at intoxicating levels, serves as a potent cue to increase smoking urge (Sayette et al., 2005) and behavior (King and Epstein, 2005). The AC group also underwent a pre-intervention alcohol response session but without feedback or discussion of the results. Instead, sessions focused on general health behaviors (e.g., nutrition, safety, exercise; ACHA, 2012) along with training on progressive muscle relaxation for stress reduction. The latter has been shown to have little effect on drinking outcomes (Miller and Wilbourne, 2002) and was used to increase the face validity of the AC intervention. The University of Chicago Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures.

2.3 Alcohol response session

The standard alcohol response protocol (King et al., 2011) was conducted several days prior to the first intervention session for the BI-ARF and AC groups. Briefly, participants consumed an alcoholic beverage (190-proof alcohol with water, flavored drink mix, and sucralose; target dose 0.08g/kg) in two drink portions over fifteen minutes with a five-minute break in between and completed questionnaires of alcohol response (Biphasic Alcohol Effects Scale, BAES; Martin et al., 1993; Drug Effects Questionnaire, DEQ; Morean et al., 2013), and smoking urge (Cox et al., 2001) at pre-drink baseline and at various intervals (15–120 minutes) after drinking.

2.4 Follow-up

At 1- and 6-months after the second intervention session, participants completed an O-TLFB for past month alcohol and smoking patterns and general health behaviors (e.g., nutrition, sleep).

2.5 Statistical analyses

The groups were compared on background characteristics using ANOVA and chi-square tests. Study outcomes included binge drinking and alcohol/smoking co-use frequency, overall drinking and smoking frequency, drinks/drinking day, and maximum number of drinks on one occasion. Outcomes were analyzed using generalized estimating equations (GEE) models (Sutker et al., 1983) with binomial distribution to examine the main effects of group and time (baseline, 1-month, and 6-month follow-ups), and their interaction. Post-estimation comparisons were used to clarify significant interaction terms. A Bonferroni correction was used to account for multiple tests of significance for the six outcomes with significance at p ≤ .008 (.05/6).

3. RESULTS

The groups did not differ on demographic and baseline characteristics (Table 1). Results from the alcohol laboratory session showed a mean peak breath alcohol concentration (BrAC) of 0.086 ± 0.013 SD g/210 L. For the BI-ARF group, during the ascending limb of the BrAC (baseline to peak), the majority of participants (90%) showed an increase in BAES stimulation, which was higher than sedation, and showed alcohol rewarding effects (80%) indicative of liking and wanting above neutral, positive effects. These effects are consistent with heavy drinkers’ alcohol response phenotype from our previous prospective study (King et al., 2011) that was replicated in an independent sample (Roche et al., 2014) and shown to predict future drinking-related problems and AUD symptoms over time (King et al., 2011, 2014). For the one female participant receiving BI-ARF who did not show this risky alcohol response profile, the feedback consisted of potential exteroceptive (e.g., environment, friends’ drinking, expectancies) rather than interoceptive factors that may factor into heavy drinking. Overall follow-up rates were excellent, with 97% and 94% of participants completing their 1- and 6-month follow-ups, respectively.

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline alcohol and smoking characteristics, by intervention group

| BI-ARF | BI-S | AC | Sig. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 22.9 (2.1) | 23.55 (1.8) | 24.73 (2.2) | .13 | |

| Education (yr) | 15.4 (1.0) | 14.5 (1.8) | 15.1 (2.2) | .52 | |

| Sex, n (%) | Male | 7 (70) | 5 (45) | 6 (55) | .52 |

| Race, n (%) | White | 8 (80) | 5 (45) | 4 (36) | .11 |

| Beck Depression Inventory | 5.3 (3.9) | 9.1 (6.5) | 10.6 (7.1) | .14 | |

| AUDIT | 14.3 (3.7) | 14.4 (4.9) | 15.0 (4.0) | .91 | |

| FTND | 0.6 (1.4) | 2.0 (1.8) | 1.8 (2.0) | .16 | |

| BYAACQ | 10.6 (3.8) | 9.9 (4.0) | -- | .69 | |

| Desire to change – drinkinga | 3.6 (2.9) | 3.7 (2.6) | 4.4 (2.6) | .78 | |

| Desire to change – smokinga | 4.8 (3.2) | 5.7 (2.9) | 5.5 (2.3) | .76 | |

| Baseline drinking/smoking (past month)b | |||||

| Binge drinking frequency (days) | 10.3 (4.9) | 8.4 (4.7) | 7.6 (3.3) | .34 | |

| Drinking and smoking co-use days | 14.5 (5.3) | 13.9 (6.0) | 14.7 (6.1) | .94 | |

| Drinking frequency (days) | 15.8 (6.0) | 14.0 (6.2) | 16.6 (7.1) | .64 | |

| Drinks/drinking day | 5.3 (1.4) | 4.9 (1.2) | 4.7 (0.8) | .51 | |

| Smoking days | 24.0 (4.4) | 23.7 (6.3) | 23.0 (8.1) | .94 | |

| Cigarettes/smoking day | 4.3 (2.49) | 7.2 (5.0) | 5.1 (2.5) | .18 | |

Note. Values are mean (SD) unless otherwise noted.

Rated 0–10, with 0 = “no desire” and 10 = “strongest desire.”

Data from the Online Timeline Follow-back assessing past month reported drinking and smoking behavior at study enrollment. BI-ARF = brief intervention with alcohol response feedback, BI-S = standard brief intervention, AC = attention control, AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test, FTND = Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence, BYAACQ = Brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire.

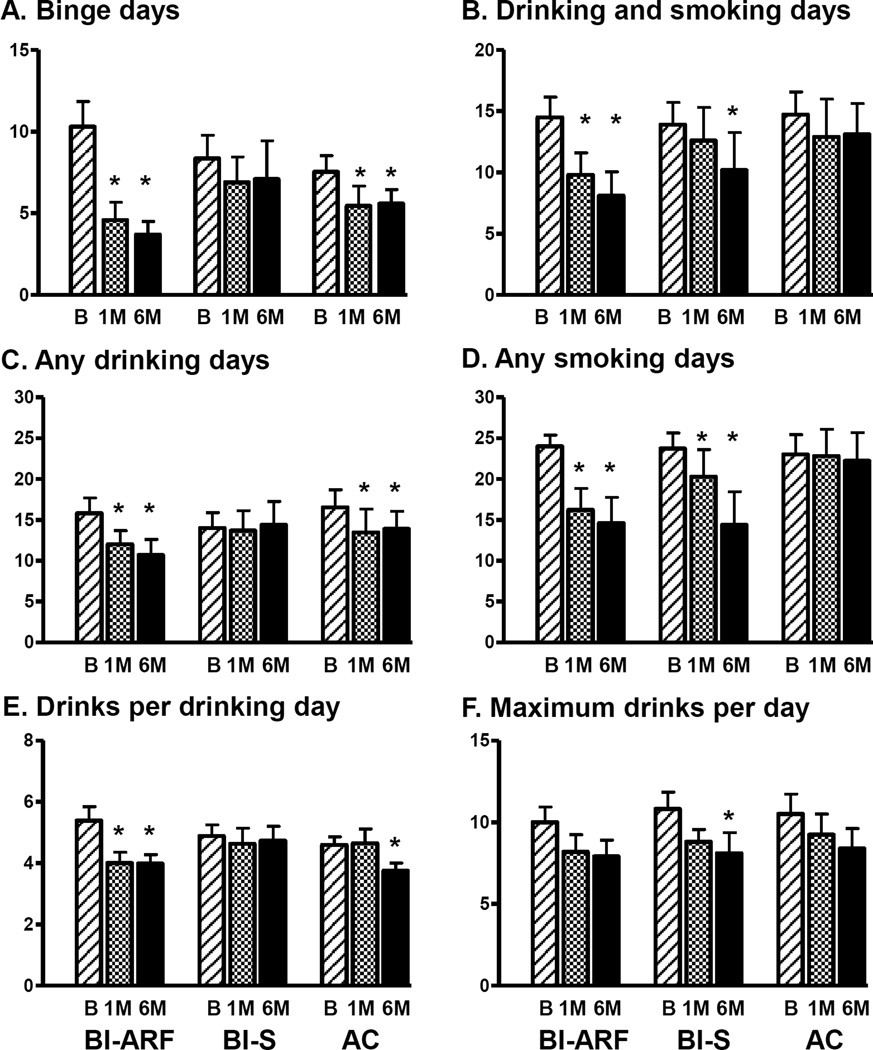

For post-intervention outcomes, the BI-ARF intervention produced larger reductions in binge drinking and alcohol-smoking co-use compared with the other two interventions (Group × Time ps < .001; Figure 1A, 1B). Specifically, the BI-ARF reduced binge drinking from 10.3 to 3.7 occasions per month at six-month follow-up (64% reduction), compared to reductions of 16% and 25% for the BI-S and AC groups, respectively. Similarly, co-use decreased 39% at six-month follow-up in the BI-ARF group versus 11% and 27% in the AC and BI-S groups, respectively. The BI-ARF also produced significantly larger reductions in drinking frequency (32%) (Group × Time p < .001) and drinks per drinking day (32% and 26% reductions, respectively; Group × Time p < .001) versus the BI-S (2% increase and 3% decrease), and fewer smoking days (39% reduction) relative to the AC (3%) (Group × Time p = .004) (Figure 1C–E). There Group × Time interaction for maximum drinks was not significant (p = .91; Figure 1F). Effect sizes for the outcomes for which the BI-ARF group produced significant reductions (Figure 1A–E) were in the medium to large range (Cohen fs = 0.35 – 0.78), whereas the effect size for the nonsignificant maximum drinks/day outcome (Figure 1F) was in the small-medium range (Cohen f = 0.26).

Figure 1. Drinking and smoking outcomes at baseline, 1-month, and 6-month follow-up for each group.

Data shown are Mean ±SEM. BI-ARF = brief intervention with alcohol response feedback, BI-S = standard brief intervention, AC = attention control, B= Baseline, 1M = 1-month follow-up, 6M = 6-month follow-up. *p < .008 for significant within-group comparisons relative to baseline. Significant post-estimation between-group comparisons were as follows: at 1-month follow-up, 1B) Drinking/smoking co-use days – BI-ARF < AC (p < .001); 1D) Smoking days - BI-ARF < AC (p < .001), BI-S < AC (p < .001); at 6-month follow-up, 1A) Binge drinking days - BI-ARF < BI-S (p < .001); 1B) Drinking/smoking co-use days - BI-ARF < AC (p < .001), BI-S < AC (p = .003); 1C) Drinking days - BI-ARF < BI-S (p = .007), BI-ARF < AC (p = .003); 1D) Smoking days - BI-ARF < AC (p < .001), BI-S < AC (p < .001).

4. DISCUSSION

The results of this pilot study were promising for enhancing outcomes with standard alcohol BI in young adult HDS by incorporating targeted, personalized feedback about alcohol response phenotype and its implications into the intervention. Six months after this intervention (BI-ARF), binge drinking rates decreased by 64%, drinking-smoking co-use by 39%, drinking smoking frequency by 32%, and smoking frequency by 39%, compared to lesser reductions produced by either the standard BI (BI-S) or the attention control (AC).

This is the first study to tailor alcohol BI in heavy-drinking young adults using personalized alcohol response feedback derived from a validated alcohol response laboratory paradigm. The present findings are consistent with those of a recent study showing that matching participants to a video-based BI based upon their level of response to alcohol’s intoxicating effects can improve outcomes (Schuckit et al., 2015). Indeed, greater response to alcohol’s stimulating and rewarding effects coupled with lower response to its sedating effects has been shown to predict increased binge drinking frequency and alcohol-related problems at 2- and 6-year follow-ups (King et al., 2011, 2014) and has been shown to remain elevated 5–6 years later in re-examination testing (King et al., in press). Therefore, for young adult binge drinkers, assessing and highlighting the potential prognostic significance of this response phenotype may increase motivation for behavior change and enhance the salience of standard alcohol BI materials.

The strengths of this study include the use of the laboratory alcohol response paradigm to assess the full range of alcohol responses in vivo that minimized environmental confounds and recall bias inherent in retrospective questionnaires (Quinn and Fromme, 2011), two active treatment comparison groups, and assessment of both drinking and smoking outcomes. A limitation is the small sample size precluding analyses of individual difference factors in response to the interventions. The present pilot study was not sufficiently powered to permit full exploration of potential moderators and mediators of the observed treatment effects, but this is an important topic for future research. Another limitation is the use of a time- and resource-intensive laboratory alcohol response session, which may limit generalizability of the current approach to real-world clinical settings. However, the medium-large effect sizes for most outcomes for the BI-ARF group increase confidence that including personalized alcohol response feedback in standard alcohol BI may produce meaningful behavior change across a variety of alcohol and smoking measures. Last, while this study provided an initial proof-of-concept demonstration for including alcohol response phenotype as a novel addition to standard alcohol BI approaches (Schuckit et al., 2015), ecologically-valid data collection with modern technology to acquire alcohol responses in participants’ natural environments (Kuntsche and Labhart, 2014; Piasecki et al., 2012) may be more time- and cost-effective than assessing these responses in the laboratory in in larger-scale future studies.

In sum, the present study results support the utility of incorporating individualized feedback on alcohol response phenotype to improve outcomes of standard alcohol BI in young adults with hazardous drinking and smoking. Future research in larger, diverse samples and using novel methods for collecting individual alcohol response data is warranted to further refine this intervention approach and improve BI outcomes in at-risk drinkers.

Highlights.

-

-

Current alcohol brief intervention (BI) is modestly effective at reducing drinking.

-

-

Feedback on alcohol response phenotype is not currently included in standard BI.

-

-

This pilot study examined the utility of adding alcohol response feedback to BI.

-

-

Including this information improved drinking and smoking outcomes in young adults.

-

-

Future research should refine this approach to enhance BI outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Source: This research was funded by R01-AA013746 (AK) and the University of Chicago Psychiatry Research Fund.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributors

Drs. Fridberg and King conceived of the study design and drafted the manuscript. Dr. Cao provided input on statistical analysis and data presentation. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest: Conflicts of interest: none.

REFERENCES

- Abbey A, Zawacki T, Buck PO, Clinton AM, McAuslan P. Alcohol and sexual assault. Alcohol Res. Health. 2001;25:43–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ACHA. Hanover, MD: American College Health Association; 2012. American College Health Association - National College Health Assessment II: Reference Group Executive Summary Spring 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines For Use In Primary Health Care. [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Carey MP, Maisto SA, Henson JM. Brief motivational interventions for heavy college drinkers: a randomized controlled trial. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2006;74:943–954. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox LS, Tiffany ST, Christen AG. Evaluation of the brief questionnaire of smoking urges (QSU-brief) in laboratory and clinical settings. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2001;3:7–16. doi: 10.1080/14622200020032051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimeff LA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Marlatt GA. Brief Alcohol Screening and Intervention for College Students: A Harm Reduction Approach. New York: The Guilford Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Fucito LM, DeMartini KS, Hanrahan TH, Whittemore R, Yaggi HK, Redeker NS. Perceptions of heavy-drinking college students about a sleep and alcohol health intervention. Behav. Sleep Med. 2014;13:395–411. doi: 10.1080/15402002.2014.919919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom K-O. The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Br. J. Addict. 1991;86:1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Strong DR, Read JP. Toward efficient and comprehensive measurement of the alcohol problems continuum in college students: the Brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2005;29:1180–1189. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000171940.95813.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AC, de Wit H, McNamara PJ, Cao D. Rewarding, stimulant, and sedative alcohol responses and relationship to future binge drinking. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2011;68:389–399. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AC, Epstein AM. Alcohol dose–dependent increases in smoking urge in light smokers. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2005;29:547–552. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000158839.65251.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AC, Hasin D, O’Connor SJ, McNamara PJ, Cao D. A prospective 5-year re-examination of alcohol response in heavy drinkers progressing in alcohol use disorder. Biol. Psychiatry. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.05.007. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AC, McNamara PJ, Hasin DS, Cao D. Alcohol challenge responses predict future alcohol use disorder symptoms: a 6-year prospective study. Biol. Psychiatry. 2014;75:798–806. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Labhart F. The future is now—using personal cellphones to gather data on substance use and related factors. Addiction. 2014;109:1052–1053. doi: 10.1111/add.12540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin CS, Earleywine M, Musty RE, Perrine M, Swift RM. Development and validation of the biphasic alcohol effects scale. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 1993;17:140–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1993.tb00739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee SA, Hinson R, Rounsaville D, Petrelli P. Survey of subjective effects of smoking while drinking among college students. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2004;6:111–117. doi: 10.1080/14622200310001656939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Wilbourne PL. Mesa Grande: a methodological analysis of clinical trials of treatments for alcohol use disorders. Addiction. 2002;97:265–277. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morean ME, de Wit H, King AC, Sofuoglu M, Rueger SY, O’Malley SS. The drug effects questionnaire: psychometric support across three drug types. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 2013;227:177–192. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2954-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, Dennhardt AA, Skidmore JR, Borsari B, Barnett NP, Colby SM, Martens MP. A randomized controlled trial of a behavioral economic supplement to brief motivational interventions for college drinking. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2012;80:876. doi: 10.1037/a0028763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negri E, La Vecchia C, Franceschi S, Tavani A. Attributable risk for oral cancer in northern Italy. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 1993;2:189–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelucchi C, Gallus S, Garavello W, Bosetti C, La Vecchia C. Cancer risk associated with alcohol and tobacco use: focus on upper aero-digestive tract and liver. Alcohol Res. Health. 2006;19:193–198. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piasecki TM, Wood PK, Shiffman S, Sher KJ, Heath AC. Responses to alcohol and cigarette use during ecologically assessed drinking episodes. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 2012;223:331–344. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2721-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabhu A, Obi KO, Rubenstein JH. The synergistic effects of alcohol and tobacco consumption on the risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2014;109:822–827. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn PD, Fromme K. Subjective response to alcohol challenge: a quantitative review. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2011;35:1759–1770. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01521.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche DJO, Palmeri MD, King AC. Acute alcohol response phenotype in heavy social drinkers is robust and reproducible. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2014;38:844–852. doi: 10.1111/acer.12280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rueger SY, Trela CJ, Palmeri M, King AC. Self-administered web-based timeline followback procedure for drinking and smoking behaviors in young adults. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs. 2012;73:829–833. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayette MA, Martin CS, Wertz JM, Perrott MA, Peters AR. The effects of alcohol on cigarette craving in heavy smokers and tobacco chippers. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2005;19:263–270. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.3.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenborn CA, Adams PF, Peregoy JA. Health behaviors of adults: United States, 2008–2010. Washington, D.C.: National Center for Health Statistics; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Smith TL. AN 8-year follow-up of 450 sons of alcoholic and control subjects. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1996;53:202–210. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830030020005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Smith TL, Kalmijn J, Skidmore J, Clausen P, Shafir A, Saunders G, Bystritsky H, Fromme K. The impact of focusing a program to prevent heavier drinking on a pre-existing phenotype, the low level of response to alcohol. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2015;39:308–316. doi: 10.1111/acer.12620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutker PB, Tabakoff B, Goist KC, Jr, Randall CL. Acute alcohol intoxication, mood states and alcohol metabolism in women and men. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1983;18(Suppl. 1):349–354. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(83)90198-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasilaki EI, Hosier SG, Cox WM. The efficacy of motivational interviewing as a brief intervention for excessive drinking: a meta-analytic review. Alcohol Alcohol. 2006;41:328–335. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agl016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitzman ER, Chen Y-Y. The co-occurrence of smoking and drinking among young adults in college: national survey results from the United States. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;80:377–386. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]