Abstract

We describe 12 subjects of ten unrelated families from the region of Campinas and the southern state of Minas Gerais, Brazil, who presented with juvenile (n = 4) and adult (n = 8) GM1 gangliosidosis. Data includes clinical history, physical examination, and ancillary exam findings. Six subjects presented initially with skeletal deformities, while the remaining six had neurological manifestations at onset. Over time, all exhibited a combination of osteoarticular and neurologic degeneration with varying degrees of severity. Corneal clouding, angiokeratomas, and inguinal hernia were seen in one individual each. Other features commonly described in lysosomal storage disorders were not found in this series, such as coarse faces, gingival hypertrophy, visceromegaly, and cherry red spot. All subjects presented with short stature, dysostosis multiplex, dysarthria, and impairment of activities of daily living, 10/12 had extrapyramidal signs, 8/12 had pyramidal signs, 8/12 had oculomotor abnormalities, 4/12 had behavioral alterations, and 2/12 had ataxia. None had seizures or Parkinsonism. All female subjects developed severe hip dysplasia and underwent arthroplasty due to chronic pain. A vertebral bone bar and os odontoideum, not previously described in this condition, were found in one patient each. There was no clear genotype–phenotype correlation regarding enzyme residual activity and clinical findings, since all subjects were compound heterozygous, but the p.T500A was the most frequent allele in eight families and was associated to Morquio B phenotype. Two sets of siblings allowed intrafamilial comparison revealing consistent features among the families. Interfamilial correlation among unrelated families presenting the same mutations was less consistent.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this chapter (doi:10.1007/8904_2015_451) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Introduction

GM1 gangliosidosis is a lysosomal storage disorder caused by deficiency in β-galactosidase (β-gal) activity due to various different mutations in the GLB1 gene (Suzuki et al. 2014). Patients of various ethnic origins have been reported with an overall incidence estimated in 1:100,000–200,000 live births, thus being considered a rare condition, except for a few ethnic groups (Suzuki et al. 2014). In southern Brazil, incidence has been estimated in 1:17,000 (Severini et al. 1999).

Three forms have been identified: type 1 (infantile, OMIM#230500), type 2 (late infantile or juvenile, OMIM#230600), and type 3 (adult or chronic, OMIM# 230650) (Brunetti-Pierri and Scaglia 2008). As in many other metabolic disorders, they represent a clinical continuum rather than separate entities. Many patients also present as Morquio B disease (OMIM#253010) which is allelic to the various forms of GM1 gangliosidosis (Giugliani et al. 1987; Paschke et al. 2001; Sperb et al. 2013).

Type 1 is characterized by facial dysmorphism, skeletal abnormalities, visceromegaly, cherry red spot, hypotonia, and psychomotor regression, with onset from birth to 7 months of age. Type 2 is characterized by mild skeletal changes, neurologic regression, seizures, muscle weakness, and onset between 7 months and 3 years of age. Type 3 starts between 3 and 30 years of age and is characterized by complex gait and speech abnormalities, florid extrapyramidal features, mild vertebral deformities, and short stature (Suzuki et al. 2014).

It has pan-ethnic distribution, and the infantile form of the disease is described more often than the others, but adult patients have been reported most often in Japan (Suzuki et al. 2014).

Patients and Methods

We describe 12 patients of ten unrelated families from the metropolitan region of Campinas and the southern state of Minas Gerais, Brazil. All were diagnosed with GM1 gangliosidosis confirmed by low enzyme activity of β-galactosidase (β-gal) measurement in leukocytes or fibroblasts using artificial 4-methylumbeliferyl β-galactosidase and by mutation analysis of GLB1 gene on DNA extracted from lymphocytes following PCR amplification and direct DNA sequencing (Baptista 2013).

Retrospective clinical data was collected from patient’s records, and prospective evaluations were performed by the same clinical geneticist and the same neurologist, with especial attention to natural history, somatic features, neurologic signs, and radiological changes.

Results

The sample was composed of seven males and five females. Consanguinity was denied by all families. In two families there was recurrence in the sibship (individuals 3–4 and 11–12). Based on the age of onset, four (subjects 2, 5, 6, and 8) were diagnosed with the juvenile and eight (subjects 1, 3, 4, 5, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12) with the adult form. Onset ranged from 1 to 12 years (mean 4.75 years). Six individuals presented with skeletal deformities, and the remaining six patients presented initially with neurological abnormalities. Over time, all 12 subjects exhibited a combination of neurological and skeletal disease (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical, biochemical, and molecular findings

| Patient | Gender | β-Gal activity (%) | GLB1 mutations | Symptom (age) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| 1 | Female | 15 (3.8)a | p.T384S/p.T500A | Skeletal deformities (3 years), learning difficulties (7 years), dysarthria and dystonia (17 years), hip dysplasia, wheelchair (19 years), dysphagia (20 years) |

| 31 years | ||||

| 2 | Male | 6 (7.7)b | p.R59H/p.T500A | Development delay (12 months), skeletal deformities (30 months), lumbar spondylolisthesis (14 years), dysarthria and dysphagia (22 years), wheelchair (23 years) |

| 32 years | IVS12nt + 8 t > C/- | |||

| 3 | Female | 3.3 (4.2)b | p.R59H/p.R201H | Neurologic regression, dysarthria (7 years), gait disorder, hip dysplasia (12 years), wheelchair (17 years), angiokeratomas (22 years) |

| 29 years | 28 (7.1)a | IVS12 + 8 t > C/- | ||

| 4 | Male | 4 (5.1)b | p.R59H/p.R201H | Neurologic regression, dysarthria (7 years), skeletal deformities (9 years), hip dysplasia (25 years), wheelchair (27 years) |

| 26 years | IVS12 + 8 t > C/- | |||

| 5 | Female | 7.8 (10)b | c.1722-1727AinsG/p.T500A | Skeletal deformities (14 months), gait disorder (2 years), dysarthria (13 years), hip dysplasia, wheelchair (14 years), dysphagia (21 years) |

| 27 years | ||||

| 6 | Male | 10 (12.8)b | p.T500A/? | Gait abnormalities (12 months), skeletal deformities (7 years), inguinal hernia (17 years), dysarthria, dysphagia (19 years) |

| 23 years | 21 (5.3)a | |||

| 7 | Female | 9 (11.5)b | p.G311R/p.T500A | Gait disorder, development delay (3.5 years), dysarthria (4 years), dystonia (11 years) wheelchair (12 years), dysphagia (18 years) |

| 23 years | 32 (8.1)a | |||

| 8 | Male | 10 (12.8)b | p.F107L/p.L173P | Gait abnormalities (12 months), neurologic regression (3 years), dysarthria (7 years), dysphagia (11 years), wheelchair (12 years) |

| 18 years | 11.7 (2.9)a | p.P152P/- | ||

| 9 | Female | 9.3 (11.9)b | p.I354S/p.T500A | Skeletal deformities (5 years), dysarthria, dysphagia (11 years), hip dysplasia, wheelchair (14 years) |

| 21 years | 16 (4.0)a | |||

| 10 | Male | 36 (9.1)b | c.1722-1727AinsG/p.T500A | Skeletal deformities (12 years), dysarthria, dysphagia (16 years) |

| 21 years | ||||

| 11 | Male | 11.7 (15)b | NA | Skeletal deformities (6 years), gait disorder (24 years), dysarthria (28 years), dysphagia (34 years), walking frame/wheelchair (34 years) |

| 35 years | ||||

| 12 | Male | NA | p.I354S/p.T500A | Short stature, gait disorder (5 years), dysarthria (20 years), dysphagia (36 years), walking frame/wheelchair (36 years) |

| 37 years |

aOn fibroblasts, reference value 394–1,440 nmol/h/mg protein

bOn leukocytes, reference value 78–280 nmol/h/mg protein

NA not available, ? unknown

All patients presented with short stature and variable findings of dysostosis multiplex. Unusual skeletal findings comprised congenital clubfeet and a vertebral bone bar in individual 1 and os odontoideum in individual 2. Other signs previously described in lysosomal storage diseases included angiokeratoma, inguinal hernia, and corneal clouding, in one individual each. Cholelithiasis, hydronephrosis, nephrolithiasis, horseshoe kidney, and cutis verticis gyrata were also seen in one individual each. No patients presented with coarse face, gingival hypertrophy, cherry red spot, visceromegaly, cardiomyopathy, or adrenal calcification (Table 2).

Table 2.

Skeletal, somatic, and visceral findings

| Patient | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short stature | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 12/12 |

| Hip dysplasia | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | NA | 10/11 |

| Epiphyseal dysplasia | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | NA | 10/11 |

| Platyspondyly | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | NA | + | + | NA | 10/10 |

| Anterior beaking of L1 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | NA | + | − | NA | 9/10 |

| Scoliosis | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | NA | + | + | NA | 9/10 |

| Kyphosis | + | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | NA | NA | + | NA | 4/9 |

| Vertebral bone bar | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | NA | − | − | NA | 1/10 |

| Os odontoideum | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | NA | NA | 1/10 |

| Congenital clubfoot | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | 1/12 |

| Cutis verticis gyrata | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | 1/12 |

| Angiokeratomas | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | 1/12 |

| Corneal clouding | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | 1/12 |

| Inguinal hernia | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | 1/12 |

| Cholelithiasis | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | 1/12 |

| Nephrolithiasis | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | 2/12 |

| Hydronephrosis | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | 1/12 |

| Horseshoe kidney | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | 1/12 |

+ present, − absent, NA not available

Clinical evaluation revealed impairment in activities of daily living in all subjects due to a mixture of neurological and osteoarticular disease, which was severe in all but one case. Limitations were mainly motor, although cognitive or behavioral abnormalities were seen in five patients and were severe in one pair of siblings. All patients had gait and speech difficulties, including some degree of dysarthria, which was accompanied by symptoms of dysphagia in 8/12. Extrapyramidal signs like facial and limb dystonia were seen in 10/12 patients, and 9/12 of them presented noticeable muscle atrophy. Pyramidal signs were present in 8/12 patients. Abnormal eye movement was seen in 8/12 patients. Signs of ataxia were documented in only one case. No patients presented with seizures or Parkinsonism (Table 3).

Table 3.

Neurological examination findings

| Patient | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Impact on ADL | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | M | S | S | 12/12 |

| Dysarthria | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 12/12 |

| Extrapyramidal signs | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | + | 10/12 |

| Facial dystonia | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | + | 10/12 |

| Limb dystonia | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | + | 10/12 |

| Grimacing face | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | + | 10/12 |

| Muscular atrophy | + | + | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | + | 9/12 |

| Pyramidal signs | − | + | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | − | + | 8/12 |

| Dysphagia | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | NA | + | − | + | 8/12 |

| Abnormal ocular movement | + | + | NA | NA | + | + | + | NA | + | + | NA | + | 8/12 |

| Behavioral alterations | − | − | + | + | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | 4/12 |

| Ataxia | − | − | − | ? | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | 2/12 |

| Parkinsonism | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | 0/12 |

| Seizures | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | 0/12 |

+ present, − absent, ? unknown, ADL activities of daily living, M mild, NA not available, S severe

Discussion

Large case series with detailed clinical descriptions of GM1 gangliosidosis are rare, and only a few focused on type 3 GM1 gangliosidosis. Muthane et al. (2004), described three patients from India and revised 40 other subjects previously reported, reinforcing that the most frequent clinical findings were generalized dystonia with prominent facial dystonia and severe speech disturbances. Roze et al. (2005) described four new patients and analyzed data from other 44 meticulously selected subjects from 16 Japanese and 15 non-Japanese families. Clinical manifestations occurred before age 20 years in most patients, typically presenting with gait disorders and/or speech disturbances, showing wide variations in severity and progression rate. Considering the ethnic background, both groups showed similar clinical manifestations, but Japanese individuals presented with an older median age at onset and greater frequency of short stature, corneal opacity, and putaminal hyperintensity when compared to non-Japanese subjects. On the other hand, non-Japanese patients had higher frequencies of mental retardation, Parkinsonism, dystonia, and scoliosis. Brunetti-Pierri and Scaglia (2008) revised clinical, molecular, and therapeutic aspects in 209 subjects with all types of GM1 gangliosidosis, comprising 130 infantile, 23 juvenile, and 56 adult patients. Signs and symptoms of the CNS involvement were invariably present in all cases, with a predominance of hypotonia and development delay in the infantile form in contrast with extrapyramidal, gait disturbances, speech difficulties, and dystonia in the adult form. A total of 102 mutations in GLB1 gene have been also revised showing extensive molecular heterogeneity and hindering a clear genotype–phenotype correlation. In the Brazilian population, Sperb et al. (2013) revised 32 patients with all types of GM1 gangliosidosis from different regions from Brazil who were diagnosed at their reference laboratory, including clinical and molecular analysis. The series included five subjects with the infantile, 15 with the juvenile, and nine with the adult form. Once more, a genotype–phenotype relationship could not be established for most patients. The most frequent mutation, c.1622–1627insG, was associated with cognitive delay and hypertonia in homozygous patients and ophthalmic findings in compound heterozygous patients. Enzyme activity was also highly variable, even for patients with the same genotype.

Our series adds 12 new patients to the literature and further highlights the phenotypic overlap between GM1 and Morquio B, which are allelic variants of various mutations of the GLB1 gene. Although all patients in our series eventually developed neurological signs, the initial presentation in half of them was skeletal (Table 1). Five subjects were initially diagnosed elsewhere as “Morquio disease” (patients 1, 5, 6, 9, and 10), three as “spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia” (patient 2 and brothers 11 and 12), and the remaining with nonspecific neurological degeneration (3, 4, 7, and 8).

Morquio was the most frequent initial diagnosis made by pediatricians and orthopedists who referred their patients for biochemical investigation. Although suggested that Morquio B disease presents with no primary central nervous system involvement (Bagshaw et al. 2002), previous studies showed that some patients develop progressive neurologic symptoms (Giugliani et al. 1987; Paschke et al. 2001). Corneal clouding is also frequent in Morquio B disease (Suzuki et al. 2014) and was diagnosed only in patient 9 who is a compound heterozygous for the p.T500A mutation.

Among other signs typically described in lysosomal storage diseases, angiokeratomas were seen in patient 3 and inguinal hernia in patient 6. None in this series presented with gingival hypertrophy, visceromegaly, cardiomyopathy, or cherry red spot, which are characteristic of patients with younger onset GM1 (Suzuki et al. 2014).

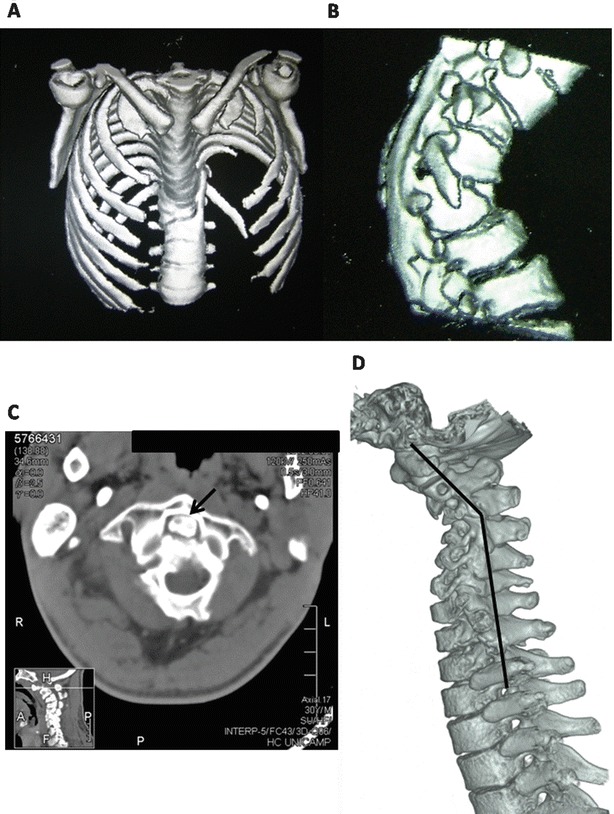

Short stature was seen in all patients, and signs of dysostosis multiplex were detected in all subjects who underwent complete radiologic evaluation (Table 2). Abnormalities of the craniocervical transition were noted in five out of six subjects submitted to head magnetic resonance imaging, two of them also presenting with cervical spine stenosis. This further shows how the skeletal and neurological also overlap in their pathophysiology: while dystonia is a known cause of chronic skeletal deformities and in particular spine deformities (Wong et al. 2005), the spine deformities caused symptomatic spine chord compression further worsening the neurologic phenotype in these patients. Atypical vertebral abnormalities were found in two individuals (Fig. 1). A vertebral bone bar was seen in patient 1, who also presented with congenital clubfeet, which might represent coincidental findings. Patient 2 presented with os odontoideum, a separation of the odontoid process from the body of the axis, which may result in dysfunctional and restraining atlantoaxial joint motion (Rozzelle et al. 2013). It was detected only at the age of 30 years and is not clear whether it is congenital or acquired, and previous reports have associated it with severe cervical dystonia (Amess et al. 1998).

Fig. 1.

CT scan showing spine deformity, anterior beaking of L1, and a bone bar in subject 1 (a, b). Stenosis of cervical spine between C1 and C2 vertebrae and os odontoideum; (c, arrow) and spondylolisthesis with narrowing and deformity of the spinal cord (d) seen in subject 2

All individuals in this series had impairment of the activities of daily living, mainly due to the severe motor difficulties. Four subjects presented with noticeable cognitive or behavioral abnormalities including intellectual deficiency in sibs 3 and 4, poor comprehension skills in patient 7, and depression in patient 8. Besides, patient 9 presented with a psychotic episode at age 16 which was considered a side effect of carbamazepine prescribed for chronic pain relief treatment, with complete remission after discontinuation of the drug. Cognitive and behavioral deficit has been rarely reported in adult GM1, but is possible that the severe motor impairment and the frequent finding of anarthria precluded a thorough cognitive evaluation in this and in previous series.

Dysarthria was diagnosed in all patients in our series and is a frequent symptom occurring in over 90% of the individuals with the adult form (Muthane et al. 2004). Dystonia of the face and limbs was described in 10/12 patients. Severe motor disability and significant complaints of dysphagia probably contributed to muscle wasting seen in 9/12 patients. This value is higher than the series of Japanese patients with the adult form where only 3/16 had muscular atrophy (Yoshida et al. 1992), but the socioeconomic conditions present in our sample might explain this discordance, rather than ethnic and genetic factors.

Pyramidal signs were described in 66% in one series of Japanese patients and 62% in non-Japanese patients (Roze et al. 2005). A similar value was seen in our series, where 8/12 subjects (66%) had pyramidal signs, although the neurologic evaluation was compromised because most patients had limitations due to pain or skeletal abnormalities. The same is valid for gait ataxia, which was confirmed only for patient 8, but could not be evaluated in the more severe patients who were wheelchair bound. Abnormal ocular movements were seen in 8/12 patients, who exhibited saccadic impairment. This has been reported previously by Muthane et al. (2004) in one adult GM1 patient. Further reports should endeavor to examine the eye movements and to confirm the frequency and characteristics of oculomotor abnormalities.

Parkinsonism has been reported in case series varying from 7.5% (Muthane et al. 2004) to 48% (Roze et al. 2005) of patients, but was not seen in our series. Epilepsy was also not reported by our patients.

The fact that all subjects were compound heterozygous poses a challenge to the study of genotype–phenotype correlations. The p.T500A was the most frequent allele, and all eight individuals presenting with this codon had an early and pronounced skeletal dysplasia, five of them being referred as having “Morquio disease.” In fact, p.T500A has been previously associated to Morquio B phenotype (Bagshaw et al. 2002; Santamaria et al. 2006; Santamaria et al. 2007; Hofer et al. 2010).

It is interesting to note that two sets of siblings allowed intrafamilial comparison revealing consistent features among the families. That is quite striking for sibs 3 and 4 who showed a very similar and unusual phenotype marked by severe cognitive impairment and also showed low values of residual β-gal activity, although the female exhibited a more pronounced hip dysplasia and the male presented more behavioral abnormalities with agitation and a hyperkinetic disorder with stereotypic movements. For sibs 11 and 12, β-gal activity was measured only in the former and molecular study only in the latter; thus, analysis of the biochemical phenotype was not possible. Concerning clinical features both presented early onset skeletal features (being initially diagnosed as X-linked SED tarda) followed by a slowly progressive neurologic disorder characterized by dysarthria, dysphagia, severe muscle wasting, and normal cognition. They are the eldest subjects in this series, and although one of the siblings became wheelchair bound during this study (he presented with spinal cord compression), the other remains still capable of short-distance walks with the aid of a walking frame, contrasting with other patients in our series that were confined to a wheelchair at a younger age.

An effort of interfamilial genotype–phenotype correlation was made among individuals presenting the same mutations, and we attempted to correlate residual enzyme activity with the phenotype. No clear relationship was visible, but some observations, if corroborated in future studies, might help understand the pleomorphic manifestations of this condition. Patients 5 and 10 present a similar residual enzyme activity, but based on the age of onset, the former was classified as having the juvenile and the latter the adult form, also being the one with the latest onset and the best clinical outcome to date in our sample. Patient 9 has the same genotype as sibs 11 and 12. All presented initially with skeletal features around the age of 5 years and developed dysarthria and dysphagia, but patient 9 had a more incapacitating hip dysplasia, as seen in the all other female subjects. Other details can be obtained from the tables and supplementary materials.

Finally, the frequency of GM1 gangliosidosis in our clinic is similar to another Brazilian case series from Rio Grande do Sul, where the juvenile phenotype was the most common (Sperb et al. 2013). However, there might be a bias in our records because the infantile form is probably underdiagnosed in our population. It is also important to note that consanguinity was denied in all families in this series and patients were in fact compound heterozygous, thus suggesting that gene frequency might be high in our region with a higher frequency of the p.T500A mutation in comparison with other mutations.

Conclusions

The adult form was the most frequent presentation of GM1 gangliosidosis in our service. This might be due to the infantile form being underdiagnosed in Brazil. The absence of consanguinity and the occurrence of compound heterozygous mutations in our series might indicate higher gene frequency in the local population, in line with previous findings from southern Brazil. Clinical presentation is very variable among the individuals, and skeletal deformities and neurologic symptoms occurred in similar frequencies as initial features, but a combination of both was seen in all individuals over time. Hip dysplasia was present in both genders and had a more severe presentation in females. Some considerations on genotype–phenotype correlation support interfamilial variation and intrafamilial homogeneity, but further studies are warranted to better understand the phenotypic pleiotropy in GLB1-related disorders.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Laboratory of Inborn Errors of Metabolism from Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre (LREIM/HCPA), Brazil, for the laboratory support.

Synopsis

Juvenile and adult GM1 gangliosidosis

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Conflict of Interest Statement

João Stein Kannebley, Laís Orrico Donnabella Bastos, Laura Silveira-Moriyama, and Carlos Eduardo Steiner declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Informed consent was obtained from all patients or their guardians for being included in the study. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee FCM/Unicamp under protocol no. 236/2011.

Animal Rights

This study did not include laboratory animals.

Details of Author Contributions

João Stein Kannebley planned the work, revised patient’s records, performed clinical evaluation, and wrote the manuscript.

Laís Orrico Donnabella Bastos performed neurological examination and revised the manuscript.

Laura Silveira-Moriyama performed neurological examination and revised the manuscript.

Carlos Eduardo Steiner planned the work, performed clinical diagnosis, provided clinical care and follow-up of the patients, and revised the manuscript.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared

Contributor Information

Carlos Eduardo Steiner, Email: steiner@fcm.unicamp.br.

Collaborators: Johannes Zschocke

References

- Amess P, Chong WK, Kirkham FJ. Acquired spinal cord lesion associated with os odontoideum causing deterioration in dystonic cerebral palsy: case report and review of the literature. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1998;40(3):195–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1998.tb15447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagshaw RD, Zhang S, Hinek A, et al. Novel mutations (Asn 484 Lys, Thr 500 Ala, Gly 438 Glu) in Morquio B disease. Biochim Byophy Acta. 2002;1588:247–253. doi: 10.1016/S0925-4439(02)00172-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baptista MB (2013) Mutation analysis in GLB1 gene in patients with GM1 Gangliosidosis, juvenile and chronic types [dissertation]. Campinas (BR): School of Medical Sciences, University of Campinas (Unicamp).

- Brunetti-Pierri N, Scaglia F. GM1 gangliosidosis: review of clinical, molecular and therapeutic aspects. Mol Genet Metab. 2008;94:391–396. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2008.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giugliani R, Jackson M, Skinner SJ, et al. Progressive mental regression in siblings with Morquio disease type B (mucopolysaccharidosis IV B) Clin Genet. 1987;32(5):313–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1987.tb03296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofer D, Paul K, Fantur K, et al. Phenotype determining alleles in GM1 gangliosidosis patients bearing novel GLB1 mutations. Clin Genet. 2010;78:236–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2010.01379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthane U, Kaneski C, Shankar SK, et al. Clinical features of adult GM1 Gangliosidosis: report of three Indian patients and review of 40 cases. Movement Disord. 2004;19(11):1334–1341. doi: 10.1002/mds.20193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paschke E, Milos I, Kreimer-Erlacher H, et al. Mutation analyses in 17 patients with deficiency in acid beta-galactosidase: three novel point mutations and high correlation of mutation W273L with Morquio disease type B. Hum Genet. 2001;109(2):159–166. doi: 10.1007/s004390100570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roze E, Paschke E, Lopez N, et al. Dystonia and Parkinsonism in GM1 type 3 gangliosidosis. Movement Disord. 2005;20(10):1366–1369. doi: 10.1002/mds.20593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozzelle CJ, Aarabi B, Dhall SS, et al. Os odontoideum. Neurosurgery. 2013;72(Suppl 2):159–169. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e318276ee69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santamaria A, Chabás A, Coll MJ, et al. Twenty-one novel mutations in the GLB1 gene identified in a large group of GM1-gangliosidosis and Morquio B patients: possible common origin for the prevalent p.R59H mutation among gypsies. Hum Mutat. 2006;922:1–11. doi: 10.1002/humu.9451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santamaria R, Chabas A, Callahan JW, et al. Expression and characterization of 14 GLB1 mutant alleles found in GM1-gangliosidosis and Morquio B patients. J Lipid Res. 2007;48:2275–2282. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M700308-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severini MH, Silva CD, Sopelsa A, et al. High frequency of type 1 GM1-gangliosidosis in southern Brazil. Clin Genet. 1999;56:168. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.1999.560215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperb F, Vairo F, Burin M. Genotypic and phenotypic characterization of Brazilian patients with GM1 gangliosidosis. Gene. 2013;512(1):113–116. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2012.09.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y, Nanba E, Matsuda J, et al. β-Galactosidase deficiency (β-galactosidosis): GM1 gangliosidosis and morquio B disease. In: Valle D, Beaudet AL, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW, Antonarakis SE, Ballabio A, Gibson K, Mitchell G, et al., editors. OMMBID-the online metabolic and molecular bases of inherited diseases. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wong AS, Massicotte EM, Fehlings MG. Surgical treatment of cervical myeloradiculopathy associated with movement disorders: indications, technique, and clinical outcome. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2005;18(Suppl S):107–114. doi: 10.1097/01.bsd.0000128693.44276.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida K, Oshima A, Sakubara H, et al. GM1 gangliosidosis in adults: clinical and molecular analysis of 16 Japanese patients. Ann Neurol. 1992;319(3):328–332. doi: 10.1002/ana.410310316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.