Abstract

Myoblasts from the pectoralis muscle of developing and adult chickens were cultured in various media and the number of differentiated myoblasts was monitored via indirect immunofluorescence using an antibody against sarcomeric myosin. Myoblasts from all age groups proliferated to a lesser extent in media lacking chicken embryo extract (CEE) when compared to myoblasts in standard medium containing 5% CEE. However, CEE influenced differentiation of myoblasts from 19-day-old embryos and adults but not that of myoblasts from 10-day-old embryos. Differentiation in cultures from 10-day embryos began at the same time and reached the same levels regardless of the presence or absence of the CEE in the medium. In contrast, differentiation of myoblasts from 19-day-old embryos and adult chickens was delayed by several days in cultures maintained with CEE compared to cultures in media lacking CEE. We do not know yet what is the active factor(s) in the CEE causing this delay of myogenic differentiation in cultures from older embryos and adults. Nevertheless, the present finding is in accordance with our previously published studies where we demonstrated that adult type chicken myoblasts, which differ from those dominant during mid-fetal development, emerge at late stages of embryogenesis and are the only one present during post-hatch and adult stages.

Keywords: chicken myogenesis, satellite cells, adult myoblasts, differentiation, chicken embryo extract

Histogenesis of skeletal muscle begins early in embryogenesis and continues through adulthood. Early in development, progenitor cells undergo myogenic determination, giving rise to myoblasts. These myoblasts proliferate, withdraw from the cell cycle, and eventually fuse into multinucleated fibers - a process which takes place throughout embryogenesis. Addition of nuclei into existing muscle fibers can still occur during the post-embryonic phase [25]. This process slows as the animal grows, so that little or no myoblast proliferation or fusion into myofibers occurs in the adult [35]. Myoblast proliferation and fusion into myofibers can still occur in the adult following injury or other more subtle stresses [14, 34, 36, 39, 44]. The primary source of myogenic cells during postnatal growth and regeneration of skeletal muscle are the satellite cells [7, 14, 24, 34]. These cells are situated adjacent to the myofiber underneath the basement membrane of the fiber [24]. Individual myofibers become encased by a basement membrane during late embryogenesis and it is at that stage that distinction of satellite cells by their morphology and location is first possible [reviewed in 14, 43]. Several growth factors which can affect activation, proliferation and differentiation of cultured satellite cells have been identified [1, 2, 6, 8, 12, 16, 28, 44–46; reviewed in 14 and 34]. These agents could be potentially involved in regulating myogenesis of satellite cells in vivo.

Evidence from different laboratories studying avian, rodent and human myoblasts has indicated that developing muscles consist of multiple myogenic populations [reviewed in 9, 18, 40, 41]. At first, this concept of multiple myogenic populations was primarily based on the observation that myoblasts from earlier and later stages of chicken development exhibit different characteristics in culture, such as media requirements for growth, and morphology of myotubes they form, but additional differences were identified at the biochemical level as well [33, 37, 40–42]. With correspondence to the embryonic (earlier) and fetal (later) phases of muscle embryogenesis, the early and late myoblasts were named by Stockdale and colleagues as embryonic and fetal myoblasts, respectively [40, 41]. Further discrete populations of myoblasts (which are often referred to as lineages) have been identified within these embryonic and fetal myoblasts by the type of myosins expressed within the myotubes formed in culture [reviewed in 40, 41]. In the chick limb, for example, the early (embryonic) period ends and the late (fetal) period begins near the first week of avian embryogenesis [40, 41]. Embryonic myoblasts are most abundant on day 5, while fetal myoblasts are most abundant between days 8–12 [40, 41]. Like myoblasts of the developing muscle, cells in the satellite cell position in postnatal muscle are derived from the somites [3]. However, cultured satellite cells isolated from postnatal and adult muscle can be distinguished from myoblasts isolated from fetal muscle [reviewed in 9, 18, 34, 40 43]. For example, compared to fetal myoblasts, cultured satellite cells have different sensitivities to phorbol esters [10] and to a voltage sensitive dye [26], differ in myosin isoform expression [13, 19, 20] and in the expression of acetylcholine receptors [11].

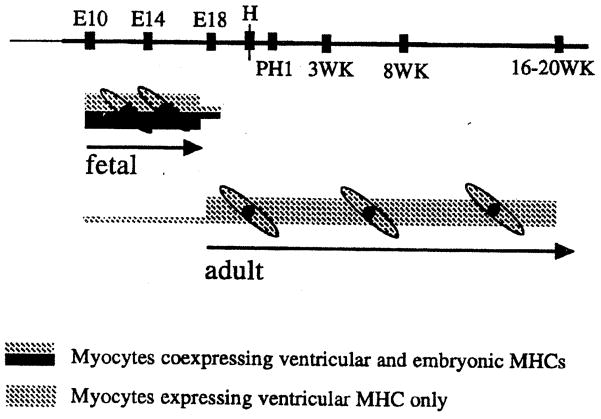

We have previously compared myosin isoform expression during myogenesis in cultures of fetal myoblasts from chicken embryos of mid-development (day 10 embryos) and myoblasts from adult chickens. We concluded that myoblasts from fetal and adult chicken skeletal muscle regulate myosin expression differently [19]. We further demonstrated that myoblasts with the ‘adult’ pattern of myosin heavy chain expression become dominant in late stages of chicken embryogenesis (embryonic day 18) [20]. A model describing the emergence of adult myoblasts, based on analysis of the various prehatch and posthatch stages is summarized in Figure 1. In accordance with the terms embryonic and fetal myoblasts used for the two myogenic populations which sequentially appear during chicken development, we and others have adapted the term adult myoblasts for the third myogenic population becoming dominant at the final days of embryogenesis [18, 40, 43]. Different from the term satellite cells, the term ‘adult myoblasts’ is independent of the position of the myogenic precursor cells in the animal and rather reflects the distinction of the cells compared to the fetal myoblasts. In addition to the differences between fetal and adult myoblasts demonstrated by the myosin isoform analyses, we also noted, throughout our cell culture studies on the mitogenic effect of platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) during myogenesis, that adult chicken myoblasts express many more receptors for PDGF than fetal myoblasts from 10-day old embryos [45]. Hence, in agreement with the myosin isoform studies, the PDGF receptor analysis have also suggested that myoblasts with the properties of those found in the adult become dominant in late stages of chicken development [45]. Furthermore, both approaches have suggested that as early as embryonic day 10, there is a small number of myogenic cells expressing the adult myoblast phenotype.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the presence of fetal and adult myoblasts during embryogenesis and posthatch stages of chicken development. E10, E14, E18 represent days of embryogenesis; PHI represents one day after hatching; 3WK, 8WK, and 16–20 WK represent weeks posthatching. H refers to hatching, which occurs on days 20–21. (Reproduced with permission of the publisher from Hartley Hartley and Yablonka-Reuveni, 1992 [18]; copyright Gordon and Breach; based on data published in Hartley et al., 1991; 1992 [19 and 20, respectively]).

During the course of the studies we consistently observed, when culturing chicken myoblasts in our routine medium containing 10% horse serum and 5% chicken embryo extract, that biochemical differentiation and fusion into myotubes in primary myogenic cultures derived from adult muscle was delayed by several days compared to cultures of myoblasts from mid-stages of development [19, 47]. This delayed differentiation was not related to the quiescence of the majority of the isolated satellite cells at the time of the initial culturing; similar lag was also demonstrated by myogenic cultures prepared from a regenerating adult muscle [19]. We further demonstrated that the delayed differentiation in culture was a common feature for all chicken myoblasts of the adult phenotype regardless the type of muscle (fast/slow) they were isolated from; we could detect it in cultures from 18-day old embryos as well as from posthatch chickens of various ages [20]. A delay in differentiation was also observed by Quinn and colleagues in myogenic cultures from 17-day old chicken embryos [32]. This delay in myogenic differentiation demonstrated by adult myoblasts could be related to intrinsic properties of the cells and could potentially be important for growth regulation during late stages of embryogenesis and during the postnatal phase.

Studies described in this paper demonstrate that the onset of differentiation of cultured adult myoblasts is strongly affected by chicken embryo extract. Adult cells cultured in the absence of chicken embryo extract differentiate rapidly. In contrast, the level of differentiation of fetal myoblasts is not affected upon removal of the embryonic extract. Although we do not yet know what factor(s) in the embryonic extract is involved in the delayed differentiation of adult myoblasts, the data suggests that myogenesis of adult and fetal chicken myoblasts is regulated differently.

Methods

Animals

Embryonated chicken eggs (White Leghorn) were purchased from H & N International (Redmond, WA). Eggs were maintained in a forced air incubator at 37.5°C. For adult chickens we used Hubbard chickens (8-week-old) kindly provided by Acme Poultry (Seattle, WA). In earlier experiments we could not detect differences in the results obtained with the two different strains [19].

Isolation and culture of primary myoblasts

Myogenic cells were isolated from the pectoralis muscle of 10- and 19-day embryonic chicks and adult chickens employing enzyme digestion and Percoll density centrifugation as previously described by us [19, 20, 45, 47]. Cells were further cultured on 35-mm culture plates that were precoated with 2% gelatin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) employing our standard chicken myoblast culture medium (85 parts Eagle’s minimal essential medium (MEM; GIBGO, Grand Island, NY; fortified with penicillin and streptomycin at 105 units per liter each), 10 parts horse serum preselected for myogenic clonal cultures (Sigma) and 5 parts chicken embryo extract). Cell density for the different experiments was as indicated under Results (Tables 1 and 2). Following 24 hours in the standard medium, cultures received 1.5 ml of fresh standard medium or an experimental medium as indicated in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Number and frequency of myosin-positive cells in myogenic cultures from chicken embryos.

| Source of cells | Additives in mediuma,b | Total cellsc | myosin + cellsd | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | No. | % | ||

| 10-day embryos | 10% HS/5% CEE | 1396 | 466 | 33.38 |

| 1297 | 356 | 28.09 | ||

| 10% HS/Tf/Fe | 626 | 190 | 30.35 | |

| 396 | 128 | 32.32 | ||

| 19-day embryos | 10% HS/5% CEE | 2649 | 94 | 3.54 |

| 10% HS/Tf/Fe | 701 | 243 | 34.66 | |

| 784 | 276 | 35.20 | ||

| 5% HS/5% CEE | 2142 | 52 | 2.42 | |

| 5% HS/Tf/Fe | 1374 | 384 | 27.94 | |

| 1229 | 398 | 32.38 | ||

HS, horse serum; CEE, chicken embryo extract; Tf, chicken transferrin at 20 μg/ml; Fe, FeSO4·7H2O at 0.834 μg/ml.

Cultures were initiated at 2 × 105 cells per 35 mm plates employing our standard medium for chicken myoblasts (10% HS/5% CEE in MEM). 24 hours later medium was changed as indicated in the Table. Cultures from 10-day embryos were mintained for 3 days prior to fixation. Cultures from 19-day embryos were maintained for 4 days. For each determination 11 fields were counted using 40 x objective.

Based on number of nuclei within mononucleated cells and myotubes.

Based on number of nuclei within myosin-positive cells and myotubes.

Table 2.

Number and frequency of myosin-positive cells in myogenic cultures from adult satellite cells.

| Additives in mediumc | Number of fields counted | Total cellsd | myosins + cellse | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | No | % | |||

| Exp 1a,b | 10% HS/5% CEE | 66 | 1107 | 5 | 0.45 |

| 2.5% FCS | 80 | 819 | 274 | 33.45 | |

| Exp 2 | 10% HS/5% CEE | 10 | 3543 | 118 | 3.33 |

| 2.5% FCS | 10 | 1000 | 335 | 33.5 | |

| 2.5% FCS/Tf/Fe | 10 | 1230 | 405 | 32.92 | |

For both experiments cultures were initiated employing our standard medium for chicken myoblasts and 24 hours later medium was changed as indicated in the Table.

Cultures for Experiment 1 were initiated at 5 × 104 cells per 35 mm plates and were fixed following 4 days in cultures. Cultures for Experiment 2 were initiated at 4 × 105 cells per 35 mm plates and were fixed following 3 days in culture.

HS, horse serum; CEE, chicken embryo extract; FCS, fetal calf serum; Tf, chicken transferrin at 20 μg/ml; Fe, FeSO4·7H2O at 0.834 μg/ml.

Based on number of nuclei within mononucleated cells and myotubes.

Based on number of nuclei within myosin-positive cells and myotubes.

Fetal calf serum (FCS) used in some medium combinations was from HyClone Laboratories (Logan, UT). In instances where transferrin was added to the medium we used the same formulation as previously described by us [43]. MEM was fortified with iron in the form of FeSO4·7H2O at 0.834 mg/liter to provide iron for transferrin. Iron formulation and concentration was based on F-10 medium from GIBCO. Highly purified chicken transferrin was from Organon Teknika Corporation, Cappel Research Products, Durham, NC and was added to MEM at 20 μg/ml. Chicken transferrin was used because species specificity was previously established for the mitogenic/trophic effect of transferrin during chicken myogenesis [5].

Preparation of chicken embryo extract

Chicken embryo extract (CEE) was prepared sterile from 10- and 11-day old embryos similar to a previously described procedure [29] but using the entire embryo. Embryos were removed from surrounding membranes, rinsed several times with MEM and forced through a 50-ml syringe. The resultant extract was diluted 1:1 with MEM and subjected to a gentle agitation for 2 hr at room temperature. The extract was then frozen at −70°C, thawed, centrifuged at 15,000xg for 10 minutes to remove particulate material and divided to smaller aliquots which were kept frozen at −20°C until used. Prior to its use, CEE was again centrifuged at about 700xg for 10 min to remove aggregates.

Quantitation of total cell numbers and of myosin-positive cells

Total cell numbers and the number of terminally differentiated cells were determined by a combination of indirect immunofluorescence to localize myosin positive cells and counter staining of all cell nuclei to facilitate analysis of cell numbers. Cultures were fixed with a cold solution of 70% ethanol:formalin:acetic acid (AFA, 20:2:1) and reacted with the monoclonal antibody MF20 followed by a secondary antibody exactly as previously described by us [19, 46]. The MF20 antibody originally prepared against chicken skeletal muscle myosin by Bader et al. [4], recognizes all isoforms of sarcomeric myosin heavy chain from numerous species and thus allows detection of differentiated myoblasts. MF20, obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, was used as an hybridoma supernatant diluted 1:5. The secondary antibody was fluorescein-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG (Organon Teknika-Cappel, Downington, PA). After the antibody reaction, nuclei were stained with ethidium bromide as previously described [17, 46]. Cultures were viewed with Zeiss microscope equipped for epifluorescence. The bright red fluorescence of the nuclei could be visualized alone using the rhodamine filters or simultaneously with the antibody stain, employing the fluorescein filters. The number of myosin-positive cells was determined by quantitating the nuclei within mononucleated and multinucleated cells reacting with the MF20 antibody. A minimum of 10 random fields per a 35-mm dish were analyzed using single or duplicate plates.

Results

Chicken embryo extract promotes mitogenesis but does not affect differentiation in myogenic cultures from 10-day embryos

Proliferation and differentiation were compared for myogenic cultures prepared from 10-day-old embryos when cultures were maintained in our standard medium containing 10% horse serum (HS) and 5% chicken embryo extract (CEE) versus medium containing 10% HS only. Transferrin (Tf) saturated with iron (Fe) was added to the latter medium since Tf was shown to be present in CEE and acts as a myotrophic agent when added to chicken myogenic cultures substituting for some of the mitogenic effect of CEE [21]. In this analysis of myoblasts from 10-day-old embryos, as in all other experiments described below, cells were initially plated in standard medium and received the experimental medium lacking CEE or fresh standard medium 24 hours later; thus the initial cell population for all parallel plates within a given experiment was identical. As shown in Table 1 cultures from 10-day embryos maintained for 3 days in the CEE medium had 2–3 times as many cells as parallel cultures maintained in the medium lacking CEE. However, the frequency of differentiated cells (MF20-positive) was similar in both media and reached a value of about 30% by day 3.

Chicken embryo extract promotes mitogenesis and suppresses differentiation in myogenic cultures from 19-day embryos

As shown in Table 1, both proliferation and differentiation of myogenic cultures from 19-day-old embryos were strongly affected by the presence of CEE. CEE enhanced proliferation in cultures maintained continuously in standard medium but % differentiation was still low (under 4%) following 4 days in culture. As previously shown, the level of differentiation in cultures from 19-day embryos maintained in standard medium eventually reaches, by culture day 5, a similar level to that described above for cultures from 10-day embryos [20]. Cultures from 19-day embryos maintained in media containing 10% HS (with Tf and Fe) had significantly fewer cells following 4 days in culture compared to parallel cultures in standard medium, but the total number and frequency of differentiated myoblasts were far higher, reaching a level of about 35%. We further demonstrated that the inhibitory effect of CEE on differentiation is consistent even in media containing lower concentrations of horse serum. As shown in Table 1 cultures from 19-day embryos maintained in medium containing 5% HS and 5% CEE had far lower numbers of MF20-positive cells compared to cultures maintained in medium containing 5% HS with Tf and Fe following 4 days in culture. Frequency of differentiated cells in the media consisting of 5% HS was under 3% when CEE was present in the medium and about 30% when absent.

Differentiation in myogenic cultures from adult chickens is accelerated in the absence of CEE

We further analyzed whether CEE contributes to the delayed differentiation previously seen by us in cultures of myoblasts isolated from adult chickens [19,47]. Cells were isolated from 8-week-old chickens and experiments were conducted as those described in Table 1 except that fetal calf serum (FCS) was used in the media lacking CEE. We concluded from preliminary experiments that it was possible to use lower FCS concentration than HS without reducing cell viability. Lower serum concentration was especially important for our studies focusing on the effect of growth factors during myogenesis of chicken adult myoblasts [45]. The total number of cells in cultures from adult muscle was far greater when cells were maintained in medium containing CEE (regardless if the medium contained in addition 10% HS as shown in Table 2 or 2.5% FCS (data not shown)), but the number and frequency of differentiated cells were far higher in cultures maintained in media lacking CEE. Differentiation in standard medium (shown in Table 2) or in medium containing 2.5% FCS and 5% CEE (data not shown) was significantly lower than in the media containing 2.5% FCS shown in Table 2 (+/− Tf/Fe). Myogenic cultures from adult muscle maintained in standard medium eventually demonstrated, following 5–6 days in culture, higher levels of differentiation as well ([19,47] and Figure 2 in the present study).

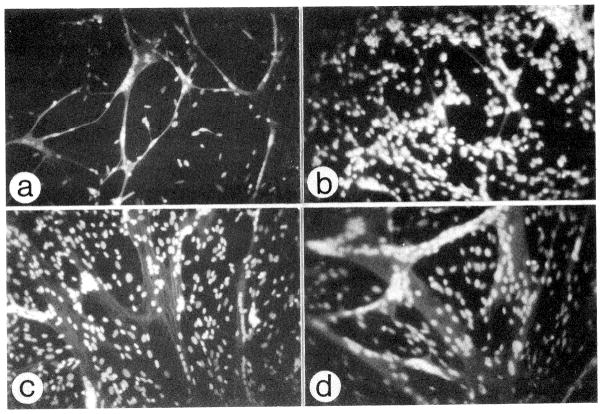

Figure 2.

Representative micrographs of myogenic cultures prepared from adult chicken and reacted via indirect immunofluorescence with an antibody against sarcomeric myosin. Nuclei were counter stained with ethidium bromide. Parallel cultures were initiated at a density of 4×105 cells per 35-mm plates using standard medium (MEM containing 10% horse serum and 5% CEE). Cultures were maintained for 24 hours in the initial standard medium then received fresh medium as follows: (a) MEM containing 2.5% FCS for 48 hours, (b) Standard medium for 72 hours, (c) Standard medium for 48 hours followed by MEM containing 2.5% FCS for 24 hours, (d) Standard medium for 5 days. 25X objective was used for all micrographs.

In addition to myoblasts, primary myogenic cultures contain cells which do not demonstrate myogenic characteristics [45,48]. One may argue that the effect of CEE on delaying differentiation of E19 and adult myoblasts is merely due to promoting proliferation of these ‘non-myogenic’ cells, leading to an apparent low frequency of differentiated myoblasts. It is important to note, however, that not only the frequency of differentiated cells, but also the actual number of differentiated cells is affected by CEE; the number of differentiated cells is far higher in E19 and adult cultures in the absence of CEE despite the fact that the total cell number is greatly reduced (see Tables 1 and 2). This indicates that the effect of CEE on decreasing the frequency of differentiated cells is not merely a result of increase in the number of non-myogenic cells. It is also important to note, that the contribution of the myogenic cells and the so-called non-myogenic cells is similar in the myogenic cultures from the different age groups studied, as determined by frequency of nuclei within myotubes under our routine culture conditions.

Figure 2 demonstrates the morphology of myogenic cultures isolated from 8-week-old chickens and maintained continuously in standard medium (10% HS/5% CEE, Figure 2b) or, following the initial day in standard medium shifted into medium lacking CEE (2.5% FCS, Figure 2a). Morphology in medium containing 2.5% FCS/Tf/Fe was similar to that in 2.5% FCS only. It is important to note that differentiated myoblasts could be detected in cultures maintained in media lacking CEE even following just 1 day in this medium (i.e., initial culturing for one day in standard medium and one additional day in the experimental medium). No differentiated myoblasts were detected in parallel cultures maintained in standard medium for two days. Also cultures maintained in standard medium during the initial 3 days than switched to a medium containing 2.5% FCS (lacking CEE) demonstrated a burst in differentiation following just one day in the 2.5% FCS medium (Figure 2c). The morphology of the culture in regard to the degree of differentiation and myotube size resembled that seen with myogenic cultures from adult chicken muscle maintained in standard medium for 5–6 days (Figure 2d).

Discussion

The present study was conducted as part of our characterization of chicken adult myoblasts. Results show that differentiation of chicken adult myoblasts (measured by the number of nuclei within sarcomeric myosin-positive cells and myotubes) is strongly affected by chicken embryo extract. The main phase of differentiation of adult myoblasts maintained continuously in media containing CEE is delayed by several days compared to parallel cultures in media lacking CEE. This delayed differentiation in the presence of CEE is demonstrated by myoblasts from both late stages of fetal development (day 19 embryos, E19 myoblasts) and from adult chickens but not by myoblasts from mid stages of development (day 10 embryos, E10 myoblasts). This transition by embryonic day 19 in myoblast phenotype from the fetal one to the adult one fits well with our previous conclusions on the emergence of the adult myogenic phenotype based on myosin isoform expression (shown in Figure 1) and PDGF receptor expression. It is important to note that the accelerated differentiation of adult myoblasts when cultured in medium lacking CEE does not affect the adult program of myosin isoform expression. As previously shown, adult myoblasts cultured in standard medium first express upon differentiation the ventricular isoform of myosin heavy chain, and after fusion into myotubes, express the embryonic isoform of fast myosin heavy chain. In contrast, fetal myoblasts cultured in standard medium coexpress the ventricular and embryonic myosin isoforms upon terminal differentiation and fusion into myotubes (as well as following fusion) [18, 20, 43]. Like adult myoblasts maintained in standard medium, adult myoblasts maintained in medium containing 2.5% FCS but lacking CEE first express ventricular myosin upon differentiation whereas expression of the embryonic myosin is delayed (Hartley and Yablonka-Reuveni, unpublished results). Fusion of rodent myoblasts is accelerated and highly synchronized when myoblasts are first maintained in media rich in serum and/or CEE followed by a transition to media poor in serum/CEE [49; see example in 46]. This approach, originally introduced by Yaffe [49] has become a routine method for culturing primary myoblasts and cell lines from rodents. The reason that this method has not been routinely applied to chicken myoblasts could potentially be due to the fact that myoblasts in most chick studies have been isolated from embryonic days 10–11. The serum/CEE reduction protocol does not necessarily lead to accelerated differentiation when studying myoblasts from this developmental age. An earlier study employed an approach of stepping down the concentration of the serum in the culture medium as a means to induce differentiation of myoblasts isolated from 5-day-old chickens; the ‘proliferation’ medium was rich in FCS and CEE was not present [12]. Only phase micrographs are provided to document the appearance of some narrow myotubes and no information is presented regarding the level of differentiation with or without serum reduction.

The delay in differentiation of adult myoblasts, but not of E10 myoblasts, when the cells are cultured in the presence of CEE, suggests that adult myoblasts regulate myogenesis differently than the fetal myoblasts. It is tempting to suggest that adult myoblasts may respond to a certain mitogens found in the CEE by extending proliferation and/or delaying differentiation whereas the fetal myoblasts may be incapable of responding to this agent. FGF which is present in chicken embryos [38] and is likely to be a major mitogenic component of CEE, can enhance proliferation of both fetal and adult myoblasts [16, 22, 23, 37]. It is still possible that the repertoire of FGF receptors present on the myoblasts from the two different age groups is different, and may underlie a delayed differentiation of adult myoblasts [see discussion in 16, 28]. We have shown that adult myoblasts express far higher levels of PDGF receptors compared to fetal myoblasts and that PDGF can enhance proliferation of adult myoblasts [45]. Furthermore, we demonstrated that PDGF can delay myogenic differentiation [46]. Although studies on the presence of PDGF in the developing chicken are not available, mRNA analysis of mouse embryos revealed abundance of PDGF transcripts in developing embryos of earlier and later stages [30, R Seifert and DF Bowen-Pope, personal communication]. Hence, it is possible that PDGF might be at least one of the agents in CEE that causes the delayed differentiation of adult myoblasts. Insulin-like growth factors were also shown to enhance proliferation of adult chicken myoblasts [12] but their effect on differentiation in this study of chicken satellite cells has not been investigated. Transferrin, a major contributor of the mitogenic effect of CEE, enhances proliferation of both fetal and adult myoblasts [5, 21, 22, 43, 45]. Transforming growth factor β (TGF) which is a potent inhibitor of myogenic differentiation [reviewed in 27] is another potential agent that could be present in the CEE and delays differentiation of the adult myoblasts. Finally, retinoic acid might be present in CEE, and was shown to induce differentiation of adult chicken myoblasts maintained in FCS-rich medium [15]. It is unclear whether retinoic acid could also enhance proliferation and delay differentiation of chicken myoblasts when, as in the present study, presented to the cells in CEE.

Work by Quinn and Nameroff has suggested that the majority of myoblasts from E10 chicks are in a compartment which is destined to divide several times before terminal differentiation (committed cells), whereas a smaller proportion of the E10 myoblasts are in a stem cell compartment and can divide multiple times before giving rise to differentiated cells [26, 31, 32]. These investigators further proposed that the number of stem cells increases in later stages of development. Possibly, the inability of CEE to delay differentiation of fetal myoblasts (isolated in the present study from E10) may be due to the committed nature of the cells. The ability to modulate differentiation of adult myoblasts by CEE might reflect the uncommitted (or stem cell) nature of these cells.

Myogenic differentiation was monitored in the present study by the appearance of sarcomeric myosin-positive cells which were visualized with an appropriate antibody. Earlier steps of myogenic differentiation can now be monitored with antibodies against the myogenic regulatory factor proteins [27, 44 and citations in these references]. Employing such antibodies we are now attempting to determine whether the effect of CEE on suppressing sarcomeric myosin expression in cultures of adult myoblasts is linked to an effect of CEE on the expression of myogenic regulatory factors.

In conclusion, although the nature of the agent(s) in CEE affecting differentiation of adult myoblasts is unresolved, the results provide further support to our proposal that adult myoblasts regulate myogenesis differently than fetal myoblasts. It is still unclear whether the differences between the adult and fetal myoblasts are acquired as the in vivo environment of the cells changes during later stages of development, or whether adult and fetal myoblasts acquire their distinctions during the early embryonic phase of muscle histogenesis.

Acknowledgments

The monoclonal antibody MF20 was obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank maintained by the Department of Pharmacology and Molecular Sciences, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, and the Department of Biology, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, under contract NO1-HD-6-2915 from the NICHD.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AR39677) and from the American Heart Association Washington Affiliate. While preparing this manuscript the author was also supported by the Cooperative State Research Service - U.S. Department of Agriculture (Agreement No. 93-37206-9301) and by the University of Washington Graduate Research Fund.

References

- 1.Allen RE, Boxhorn LK. Regulation of skeletal muscle satellite cell proliferation and differentiation by transforming growth factor-β, insulin-like growth factor I, and fibroblast growth factor. J Cell Physiol. 1989;138:311–315. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041380213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen RE, Dodson MV, Luiten LS. Regulation of skeletal muscle satellite cell proliferation by bovine pituitary fibroblast growth factor. Exp Cell Res. 1984;152:154–160. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(84)90239-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armand O, Boutineau A-M, Mauger A, Pautou M-P, Kieny M. Origin of satellite cells in avian skeletal muscle. Arch Anat. 1983;72:163–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bader D, Masaki T, Fischman DA. Immunohistochemical analysis of myosin heavy chain during avian myogenesis in vivo and in vitro. J Cell Biol. 1982;95:763–770. doi: 10.1083/jcb.95.3.763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beach RL, Popiela H, Festoff BW. Specificity of chicken and mammalian transferrins in myogenesis. Cell Differentiation. 1985;16:93–100. doi: 10.1016/0045-6039(85)90522-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bischoff R. Proliferation of muscle satellite cells in intact myofibers in culture. Dev Biol. 1986;115:129–139. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(86)90234-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campion DR. The muscle satellite cell: A review. Int Rev Cytol. 1984;87:225–251. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)62444-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clegg CH, Linkhart TA, Olwin BB, Hauschka SD. Growth factor control of skeletal muscle differentiation: Commitment to terminal differentiation occurs in G1 phase and is repressed by fibroblast growth factor. J Cell Biol. 1987;105:949–956. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.2.949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cossu G, Molinaro M. Cell heterogeneity in the myogenic lineage. Curr Top Dev Biol. 1987;23:185–208. doi: 10.1016/s0070-2153(08)60625-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cossu G, Cicinelli P, Fieri C, Coletta M, Molinaro M. Emergence of TPA-resistent “satellite” cells during muscle histogenesis of human limb. Exp Cell Res. 1985;160:403–411. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(85)90187-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cossu G, Eusebi F, Grassi F, Wanke E. Acetylcholine receptors are present in undifferentiated satellite cells but not in embryonic myoblasts in culture. Dev Biol. 1987;123:43–50. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(87)90425-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duclos MJ, Wilkie RS, Goddard C. Stimulation of DNA synthesis in chicken muscle satellite cells by insulin and insulin-like growth factors: Evidence for exclusive mediation by a type-I insulin-like growth factor. J Endocrinol. 1990;128:35–42. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1280035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feldman JL, Stockdale FE. Temporal appearance of satellite cells during myogenesis. Dev Biol. 1992;153:217–226. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(92)90107-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grounds MD, Yablonka-Reuveni Z. Molecular and cellular biology of muscle regeneration. In: Partridge T, editor. Molecular and Cell Biology of Muscular Dystrophy. London: Chapman & Hall; 1993. pp. 210–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Halevy O, Lerman O. Retinoic acid induces adult muscle cell differentiation mediated by the retinoic acid receptor-α. J Cell Physiol. 1993;154:566–572. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041540315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Halevy O, Monsonego E, Marcelle C, Hodik V, Mett A, Pines M. A new avian fibroblast growth factor receptor in myogenic and chondrogenic cell differentiation. Exp Cell Res. 1994;212:278–284. doi: 10.1006/excr.1994.1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hartley RS, Yablonka-Reuveni Z. Long-term maintenance of primary myogenic cultures on a reconstituted basement membrane. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol. 1990;26:955–961. doi: 10.1007/BF02624469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hartley RS, Yablonka-Reuveni Z. Evidence for a distinct adult myogenic lineage in skeletal muscle. Comments on Dev Neurobiol. 1992;1:391–404. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hartley RS, Bandman E, Yablonka-Reuveni Z. Myoblasts from embryonic and adult skeletal muscle regulate myosin expression differently. Dev Biol. 1991;148:249–260. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(91)90334-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hartley RS, Bandman E, Yablonka-Reuveni Z. Skeletal muscle satellite cells appear during late chicken embryogenesis. Dev Biol. 1992;153:206–216. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(92)90106-q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ii I, Kimura I, Ozawa E. A myotrophic protein from chick embryo extract: Its purification, identity to transferrin and indispensability for avian myogenesis. Dev Biol. 1982;94:366–377. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(82)90354-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kardami E, Spector D, Strohman RC. Selected muscle and nerve extracts contain an activity which stimulates myoblast proliferation and which is distinct from transferrin. Dev Biol. 1985;112:353–358. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(85)90406-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kardami E, Spector D, Strohman RC. Myogenic growth factor present in skeletal muscle is purified by heparin-affinity chromatography. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:8044–8047. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.23.8044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mauro A. Satellite cell of skeletal muscle fibers. J Biophys Biochem Cytol. 1991;9:493–495. doi: 10.1083/jcb.9.2.493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moss FP, Leblond CP. Satellite cells as a source of nuclei in muscles of growing rats. Anat Rec. 1971;170:421–436. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091700405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nameroff M, Rhodes LD. Differential response among cells in the chick embryo myogenic lineage to photosensitization by Merocyanine 540. J Cell Physiol. 1989;141:475–482. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041410305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olson EN. Signal transduction pathways that regulate skeletal muscle gene expression. Molec Endocrinol. 1993;7:1369–1378. doi: 10.1210/mend.7.11.8114752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Olwin BB, Rapraeger A. Repression of myogenic differentiation by aFGF, bFGF, and K-FGF is dependent on cellular heparan sulfate. J Cell Biol. 1991;118:631–639. doi: 10.1083/jcb.118.3.631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O’Neill MC, Stockdale FE. A kinetic analysis of myogenesis in vitro. J Cell Biol. 1972;52:52–65. doi: 10.1083/jcb.52.1.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Orr-Urtreger A, Lonai P. Platelet-derived growth factor-A and its receptor are expressed in separated, but adjacent cell layers of the mouse embryo. Development. 1992;115:1045–1058. doi: 10.1242/dev.115.4.1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quinn LS, Nameroff M, Holtzer H. Age-dependent change in myogenic precursor cell compartment sizes. Evidence for the existence of a stem cell. Exp Cell Res. 1984;154:65–82. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(84)90668-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Quinn LS, Rhodes LD, Nameroff M. Characterization of sequential myogenic cell lineage compartments. In: Kedes LH, Stockdale FE, editors. Cellular and Molecular Biology of Muscle Development. New York: Alan R Liss, Inc; 1989. pp. 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rutz R, Hauschka S. Clonal analysis of vertebrate myogenesis. VII. Heritability of muscle colony type through sequential subclonal passages in vitro. Dev Biol. 1982;91:103–110. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(82)90013-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schultz E, McCormick KM. Skeletal muscle satellite cells. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 1994;123:213–257. doi: 10.1007/BFb0030904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schultz E, Gibson MC, Champion T. Satellite cells are mitotically quiescent in mature mouse muscle: An EM and radioautographic study. J Exp Zool. 1978;206:451–456. doi: 10.1002/jez.1402060314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schultz E, Jaryszak DL, Valliere CR. Response of satellite cells to focal skeletal muscle injury. Muscle Nerve. 1985;8:217–222. doi: 10.1002/mus.880080307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seed J, Hauschka SD. Clonal analysis of vertebrate myogenesis. VIII. Fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-dependent and FGF-independent muscle colony types during chick wing development. Dev Biol. 1988;128:40–49. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(88)90264-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seed J, Olwin BB, Hauschka SD. Fibroblast growth factor levels in the whole embryo and limb bud during chick development. Dev Biol. 1988;128:50–57. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(88)90265-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Snow MH. Satellite cell response in rat soleus muscle undergoing hypertrophy due to surgical ablation of synergists. Anat Rec. 1990;227:437–446. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092270407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stockdale FE. Myogenic cell lineages. Dev Biol. 1992;154:284–298. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(92)90068-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stockdale FE, Miller JB. The cellular basis of myosin heavy chain isoform expression during developmental avian skeletal muscles. Dev Biol. 1987;123:1–9. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(87)90420-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.White NK, Bonner PH, Nelson DR, Hauschka SD. Clonal analysis of vertebrate myogenesis. IV. Medium dependent classification of colony-forming cells. Dev Biol. 1975;44:346–361. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(75)90405-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yablonka-Reuveni Z. Development and postnatal regulation of adult myoblasts. Microscopy Research and Techniques. 1994 doi: 10.1002/jemt.1070300504. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yablonka-Reuveni Z, Rivera AJ. Temporal expression of regulatory and structural muscle proteins during myogenesis of satellite cells on isolated adult rat fibers. Dev Biol. 1994;164:588–603. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yablonka-Reuveni Z, Seifert RA. Proliferation of chicken myoblasts is regulated by specific isoforms of platelet-derived growth factor: Evidence for differences between myoblasts from mid and late stages of embryogenesis. Dev Biol. 1993;156:307–318. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1993.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yablonka-Reuveni Z, Balestreri TM, Bowen-Pope DF. Regulation of proliferation and differentiation of myoblasts derived from adult mouse skeletal muscle by specific isoforms of PDGF. J Cell Biol. 1990;111:1623–1629. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.4.1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yablonka-Reuveni Z, Quinn LS, Nameroff M. Isolation and clonal analysis of satellite cells from chicken pectoralis muscle. Dev Biol. 1987;119:252–259. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(87)90226-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yablonka-Reuveni Z, Anderson SK, Bowen-Pope DF, Nameroff M. Biochemical and morphological differences between fibroblasts and myoblasts from embryonic chicken skeletal muscle. Cell Tissue Res. 1988:339–348. doi: 10.1007/BF00214376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yaffe D. Rat skeletal muscle cells. In: Kruse PF, Patterson MK Jr, editors. Tissue Culture: Methods and Application. New York: Academic Press; 1973. pp. 106–114. [Google Scholar]