Abstract

Calcaneal osteomyelitis presents a complicated situation. The specific anatomy of the os calcis and its surrounding soft tissues plays an important role in the planning and realization of the procedures needed in order to eradicate the osteomyelitic focus. The calcaneus represents a spongious bone; a fact that supports the developement of an osteomyelitis. It is the strongest bone of the foot and is highly important for the biomechanical features of physiological walking. The surrounding soft tissues are thin and contain various important anatomical structures. These might be damaged during the treatment of the osteomyelitis. In addition the vascularization of the os calcis is delicate and may be compromized during the surgical osteomyelitis treatment.

Calcaneus osteomyelitis may be classified based on the routes of infection into exogenous and endogenous forms. Additionally from the clinical point of view acute and chronic forms may be distinguished from an early and a late infection.

Exogenous calcaneal osteomyelitis mostly is the result of an infection with S. aureus.

The treatment is equal to the therapy in other locations and based on:

Eradication of the bone infection

Sanitation of the soft tissue infection

Reconstruction of bone and soft tissue

Especially the preservation and restoration of the soft tissue is important. Thus plastic surgical procedures play an essential role.

The main object of treatment is the preservation of a biomechanical functioning foot. This may be impossible due to the local situation. Calcanectomy or even below knee amputation may be needed in those cases.

Keywords: calcaneus, osteomyelitis, etiology, incidence, diagnostics, therapy

Zusammenfassung

Die Fersenbeinosteitis ist eine seltene Entität. Sie konfrontiert den behandelnden Arzt mit einer Reihe komplizierter Probleme. Eine wesentliche Rolle spielt dabei die spezielle Anatomie des Calcaneus und seiner umgebenden Weichteile. Der Calcaneus ist beim Gehen und der daraus folgenden Lastübertragung vom Körper biomechanisch hoch belastet. Das Fersenbein ist ein spongiöser Knochen und bietet demnach gute Voraussetzungen für eine Erregerausbreitung. Der umgebende Weichteilmantel ist dünn, enthält aber auf engem Raum eine große Zahl wesentlicher anatomischer Strukturen. Die möglichst ungestörte Durchblutung des Calcaneus ist eine Voraussetzung für die erfolgreiche Therapie. Gerade diese wird aber bei den z.T. ausgedehnten chirurgischen Revisionsoperationen im Rahmen der Infektsanierung häufig kompromittiert.

Unterteilt wird die Calcaneus-Osteitis in eine exogene (posttraumatische/postoperative) Form und in eine endogene (hämatogene) Form. Mit Blick auf die klinische Relevanz unterscheidet man die akute von der chronischen und die Früh- von der Spätinfektion.

Ursächlich für die Entstehung der in diesem Artikel betrachteten exogenen Calcaneus-Osteitis sind im wesentlichen Staphylokokken.

Die Therapie basiert wie die Behandlung der übrigen Osteitiden auf:

Infektsanierung am Knochen

Infektsanierung an den Weichteilen

Rekonstruktion von Knochen und Weichteilen

Gerade im Rückfußbereich muss eben diesem Erhalt bzw. der Rekonstruktion des Weichteilmantels wesentliche Aufmerksamkeit gezollt werden. Insofern haben die plastisch-rekonstruktiven Verfahren an dieser Stelle einen bedeutenden Stellenwert.

Oberstes Ziel der Behandlung ist initial der Erhalt eines funktionsfähigen, belastbaren Fußes. Ist dies nicht möglich kommen lokal ablative Verfahren (Calcanektomie) ebenso wie die Unterschenkelamputation in Betracht.

Introduction

The treatment of calcaneal osteitis (CO) represents a demanding challenge. Analog to the treatment of skeletal infections in other locations the objective is defined obviously [1]:

Calming of the infection

Reconstruction of the bone

Reconstruction of the soft tissue

Preservation or reconstruction of affected joints

For the patient: "Back to normal life as fast as possible".

Anatomy

The special anatomic configuration of the calcaneus leads to some special problems during the treatment of CO:

The calcaneus is one of the most stressed structures in terms of weight bearing and load transfer from the foot to the ground.

The special combination of highly elaborated anatomical shape, high load transfer capacity and thin surrounding soft tissue. In case of trauma and or infection this combination leads to an extreme local vulnerability.

In their article from 2010 Fukuda et al. summarize the main qualities of the calcaneus [2]:

The calcaneus is the most stable anatomical structure of the pedal skeleton. It is one vital part of the “lateral column” [3].

During walking the calcaneus transfers axial energy to fore and hind foot [4].

The special flexible calcaneal incorporation in the pedal skeleton allows the adjustment to the ground and thus walking on rough surfaces.

Tendons and ligaments stabilizing the pedal skeleton insert at the calcaneus, including the strongest human tendon (Achilles tendon).

Aa. tibialis anterior, posterior and peronea ensure the calcaneal vascularization. These vessels are connected to each other and thus form angiosoms. The successful treatment of any calcaneal trauma or infection is based on the knowledge of the location of these interconnections [5]. The interconnections between Aa. tibialis anterior and posterior are located [2]:

5 to 7 cm above the ankle

On ankle level

Next to the achilles tendon

The venous drainage is based on the minor saphenous vein. According to Zwipp 2005 the vulnerability of the hind foot originates from [6]:

Thin soft tissue layer at the medial and lateral calcaneal aspect.

Special anatomical structure of the planta pedis.

Classification

There is no specific classification for CO. It is based on the established classifications for osteitis/osteomyelitis [7]:

Type of infection (specific/non-specific)

Portal of entry (endogenous – hematogemous/exogenous – post traumatic)

Direction of expansion (centripetal/cetrifugal)

Acuteness (acute/primary chronical/secondary chronical)

Onset of symptoms (early infection/late infection)

According to Fukuda 2010 two special entities have to be differentiated [2]:

Posttraumatic CO

CO based on chronical pressure. In these cases CO is often accompanied by diabetes (“Charcot foot”) or appears in the course of Charcot Marie Struempels disease.

Incidence

Only a few articles deal with the incidence of CO. In 1992 Wang et al. put the number of CO to 7 to 8% of all bone infections based on studies of Feigin et al. in 1970 [8], [9]. In the literature often wound infection, soft tissue infection and bone infection will not be differentiated. Schildhauer et al. quantified the calcaneal rate of infections to 11% [10]. Aseptic necroses of the wound edge especially after extended lateral approaches to the calcaneus are described in the literature between 2 to 27.3% [11], [12], [13]. Delayed healing or postoperative infection may occur up to 25% [4], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18]. Postoperative hematoma may be detected between 2 to 5% [11], [19], [20]. In case of closed fractures deep wound infections or CO occurs in 1 to 4%, in case of open fractures up to 7% [11], [14], [16], [18], [20], [21]. Siebert et al. describe the ratio of infection up to 60% in case of open calcaneal fractures. Amputation may be proceeded in these cases up to 14% [22]. The rate of complications is raised 5 to 7 times in case of open calcaneal fracture [23].

Etiology

By analogy to bone infections in altero loco there exist various predispositioning factors for the establishement of CO [24]:

a. Local factors

Extent of the local bone damage

Extent of the local soft tissue damage

Localization of the fracture

Preexisting local problems (local circulatory disturbance etc.)

Virulence of the pathogen

b. Systemic factors

Diabetes mellitus

Vasculitis

Rheumatoid arthritis

General circulatory disturbance

Nicotine abuse

Obesity

Tumors

Immune suppression

Immune deficit

c. Iatrogene factors

-

Therapeutical performance

Time of intervention

Manipulation during fracture reposition

Intraoperative manipulation of bone and soft tissue

Surgical approach

Duration of the operation

Osteosynthesis material and configuration

Hygiene deficit

Pathogens

There is no specific CO pathogen. Staphylococci, especially S. aureus and epidermidis but even Streptococci remain the most frequent bacteria to be detected (80%) [24]. The rate of multi-resistant bacteria increases during the last years, a trend already decribed by Giske, Rice and Spellberg in 2008 [25], [26], [27]. Rice summarized these pathogens by the acronym ESCAPE (Enterococcus faecium, S. aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumanii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Enterobactes species) [26]. In their 2008 study Aragón-Sánchez et al. found S. aureus in pedal osteitis in 51.3%. Multiresistancy could be detected in 36.8% of those infections [28]. Sometimes atypical pathogenes may be detected like:

Symptoms

As well as in other cases of osteitis/osteomyelitis the typical clinical symtoms may not be detectable. It is important to think of this entity as an option whenever the following circumstances apply:

History of local hind foot injuries

Hind foot operations

Scars located at the hindfoot

Paraclinical signs of infection combined with secreting pedal wounds

According to Chen the following symptomy may occur in case of CO [24]:

Reddening of the skin

Hind foot pain

Edematous swelling

Toe walk (weight bearing on the fore foot)

Diagnostic investigations

Diagnostics of the CO is based on clinical and apparative findings and may be distinguished into the pre- and intraoperative phase.

a. Parameters analyzed in the preoperative phase:

Patients medical history

Symptoms

Laboratory findings (i.e. white blood count, C-reactive protein). Not only the absolute value of leucocytes and C-reactive protein have to be analysed but also the course of those parameters. The absence of a normalization of the above named parameters f.e. after trauma or postoperatively may be an early sign of infection.

-

Radiological examination (x-ray, CT, MRI, PET-CT)

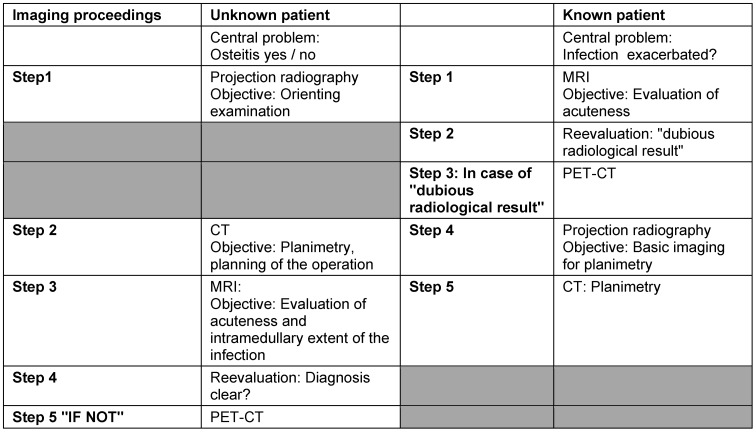

The diagnostic imaging should deliver the radio morphologic correlate to the clinical and laboratory findings [32], [33]. It supports the physician’s effort to create an exact map of the localization and extent of CO (“planimetry”). We created a special algorithm to coordinate the imaging methods in order to achieve the optimal result (Table 1 (Tab. 1)).

Table 1. Algorithm for the CO imaging diagnostics.

b. Parameters analyzed intraoperatively:

Microbiological samples

Histological samples

The collection of microbiological and histological samples from the infected bone and soft tissue is the “gold standard” of the intraoperative diagnostics for infectious bone diseases. Infectious bone diseases are known for their occasionally small number of pathogens [34]. Thus the microbiological proof of an infection somtimes may be missing. The histological analysis may lead to the proper diagnosis in these cases.

Therapy

According to Hofmann 2004 the therapy of CO is, in analogy to osteitis/osteomyelitis in general, divided into 3 phases [35]:

Phase I: Sanitation of bone and soft tissue (leads to calming of the infect)

Phase II: Soft tissue reconstruction

Phase III: Reconstruction of the bone.

Phase II and III may be processed parallel.

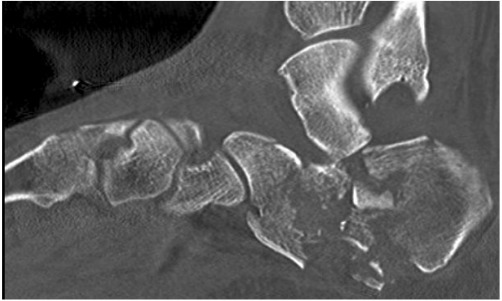

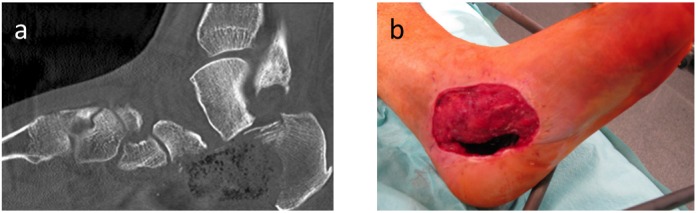

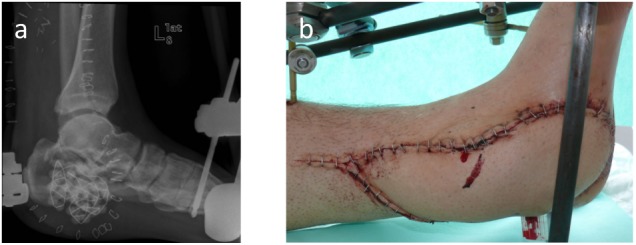

See Figure 1 (Fig. 1), Figure 2 (Fig. 2), Figure 3 (Fig. 3), Figure 4 (Fig. 4).

Figure 1. Initial lateral CT scan of 2o open calcaneal fracture (“Joint Depression” Type). March 2009. Initial conservative treatment. Early infection with the proof of Acinetobacter baumanii. After transferral achievement of biomechanical stability by an external fixator. Consequent local surgical debridement combined with local and systemical antibiotics led to infect calming and negative proof of bacteria in the former infection area. BUT: Remaining extended bone and soft tissue lesion.

Figure 2. a. Lateral calcaneal CT scan after local surgical infect eradication. Extended calcaneal bone defect with additional destruction of the subtalar joint.

b. Clinical presentation of the remaining local soft tissue lesion.

Due to the extent of the bone and soft tissue lesion decision to proceed in a two step therapy. First: Reconstruction of the soft tissue. Second: Reconstruction of the os calcis.

The waiver of using a composite flap in a one step procedure in our opinion leads to a more accurate positioning of the bone graft due to the fact, that we do not have to focus on the perforator vessels connecting soft tissue and bone in these composite flaps.

Figure 3. a. Projction radiographical lateral image of the os calcis. Antibiotic chain serves as a spacer for later implantation of bone graft.

b. Clinical presentation after closure of the soft tissue lesion by an ALT flap.

After a 3 months time period without any signs of recurrent infection a partial raise of the ALT flap was proceeded and a micro vascularized iliac crest bone graft was transplanted (anastomosed to the A. tibialis posterior). After bony assimilation of the graft complete weight bearing was achieved after furthes 4 weeks. Today’s situation: Full weight bearing, subtalar arthrodesis, no walking canes, back to work in october 2010

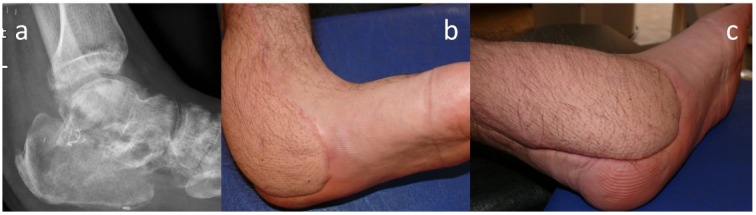

Figure 4. a. Lateral projection radiographical image after bony assimilation of the iliac crest graft and subtalar arthrodesis.

b. and c. Clinical healed up presentation

Phase I/surgery

Local surgical eradication of the infection site (bone in combination with the soft tissue) remains the basic therapeutical procedure. As mentioned above in contrast to infectious bone diseases in other locations the local layer of soft tissue is extremely thin at the hind foot. If this thin layer has to be resected in order to proceed radical local surgery the calcaneus is threatened vitally. Heier et al. postulated in 2003: “The extent of soft tissue damage determines the therapeutical result”. This thesis drafted for open calcaneal fractures applies for CO as well [36]. In this respect the early soft tissue coverage plays an important role. The preservation of the calcaneus and thus a functional pedal anatomy is the main target during the infect sanitation. This is not always feasible. Depending on the local situation the spectrum of surgical procedures includes partial calcaneal resection, calcanectomy and lower leg amputation (as an ultima ratio). According to Bollinger and Lehmann partial calcanectomy is a decent alternative to lower leg amputation in cases of strictly local infection [37], [38]. In their study of 2008 Bragdon et al. supported this thesis. The authors mentioned, that partial calcaneal resection may be performed if the inflammatory process does involve less than 50% of the heel [39]. In these circumstances the sufficient hind foot blood supply seems to be the central problem [40], [41]. Syme-Amputation may also be performed in special cases.

Phase I/adjuvant therapy

Surgery is supported by application of antibiotics (systemic and/or local antibiotics). The correct selection depends on the pathogens proven at the infection site. Analogous to bone infections in other locations early or acute infections will be treated immediately after harvesting samples for the microbiological analysis (calculated antibiotic therapy).

The additional administration of dietary minerals and vitamins may be discussed [42], [43], [44].

Phase II/III

Exact planning in advance is a must before doing any reconstructive surgery. The following factors have to be analyzed:

Extent of the calcaneal bone defect

Localization of the calcaneal bone defect

Extent of the soft tissue defect

Localization of the soft tissue defect

Additional involvement of the subtalar and calcaneocuboidal joint

Subtalar arthrosis

Calcaneocuboidal arthrosis

Depending on the size and localization of the calcaneal bone defect local cancellous bone plastic may be discussed as well as (microvacularized) bone grafts. Segment transportation by callotaxis plays a tangential role. Basic element of any reconstructive procedure is the biomechanical stability of the calcaneus (analogy to bone reconstructive procedures at another location). Stability may be achieved by using external fixators.

The status of the subtalar and calcaneocuboidal joint has to be analyzed critically. If those joints were involved and were damaged (by infection and/or resection) arthrodesis has to be discussed.

Phase II/III: Reconstruction of the calcaneus by micro vacularized bone graft

Though small calcaneal defects may be filled up by using cancellous bone grafts or corticospongious chips, this methods are not sufficient for defects bigger than 6 cm in diameter. In 2010 Schmidt et al. described the muscular and osteomuscular composite peroneus brevis flap for those defects [45]. Osteocutaneous free fibula transplantation as well as osteocutaneous flaps including the medial tibial condylus have been used successfully [46], [47].

Phase II/III: Reconstruction of the soft tissue

In case of small bone defects which could be filled up by using cancellous bone graft local pediculated muscular flaps may be proceeded. The soft tissue defects in these cases mostly originate from calcaneal osteosynthese and are located on the lateral face of the hind foot. Local flaps like mentioned above may solve these problems. Vacuum sealing of the wounds should only be a temporary bridging method, if the soft tissue can not be restored contemporarily. If the soft tissue defect extends to the basis of the 5th metatarsal bone, one has to keep the raised number of flap apex necroses in mind. Local wound conditioning combined with later mesh graft may be feasible.

Locoregional pediculated flaps like M. abductor digiti minimi or M. abductor hallucis are mentioned in the literature and may also be useful for closing small soft tissue defects [48], [49].

In case of more extended soft tissue defects the pediculated fasciocutaneous suralis flap may be used. Once again in case of soft tissue defects extending to the dorsum of the foot necroses may occur in the distal 1/3 of the graft due to a reduced venous flow. This situation may lead to a venous swelling of the flap with resolving flap necrosis. In case of exposed extensor tendons on the dorsum of the foot, free microvascularized flaps should be discussed.

Free microvascularized flaps are also indicated in case of large soft tissue defects. We use the anterolateral upper leg flap which mostly is anastomosed to the A. tibialis anterior. A. dorsalis pedis we use as an exeption due to its close position to the infection site.

Differential diagnosis

Tumors and tumor like lesions may mimic CO. 3% of all bone tumors are located in the foot. Soft tissue tumors outnumber bone lesions 10 times, malignant tumor benign tumors 5 times [50]. Therefore an analytic approach with prompt usage of the appropriate diagnostic features is a must in order to avoid further complications (Table 1 (Tab. 1)).

Conclusion

CO is a rare entity. The therapy corresponds to the therapeutical approach to bone infections in other locations. It is based on:

Local surgical eradication of the infected bone segment and its surrounding soft tissue

Local and/or systemic application of antibiotics

Usage of further supplementary therapies (f.e. application of trace elements)

Preservation or reconstruction of the bone structure of the heel

Preservation or reconstruction of the soft tissue surrounding the heel

The special anatomical situation at the hind foot with just a thin covering soft tissue layer complicates the situation. Therefore soft tissue preservation or reconstruction as early as possible is of vital relevance.

Ablative therapy should only be proceeded as an ultima ratio.

Notes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Tiemann AH, Hofmann GO. Principles of the therapy of bone infections in adult extremities: Are there any new developments? Strategies Trauma Limb Reconstr. 2009 Oct;4(2):57–64. doi: 10.1007/s11751-009-0059-y. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11751-009-0059-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fukuda T, Reddy V, Ptaszek AJ. The infected calcaneus. Foot Ankle Clin. 2010 Sep;15(3):477–486. doi: 10.1016/j.fcl.2010.04.002. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.fcl.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moore KL. Clinically oriented anatomy. Philadelphia (PA): Williams & Wilkins; 1992. The lower limb. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levin LS, Nunley JA. The management of soft-tissue problems associated with calcaneal fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993 May;(290):151–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Attinger C, Cooper P. Soft tissue reconstruction for calcaneal fractures or osteomyelitis. Orthop Clin North Am. 2001 Jan;32(1):135–170. doi: 10.1016/S0030-5898(05)70199-1. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0030-5898(05)70199-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zwipp H, Rammelt S, Barthel S. Kalkaneusfraktur. [Fracture of the calcaneus]. Unfallchirurg. 2005 Sep;108(9):737–748. doi: 10.1007/s00113-005-1000-6. (Ger). Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00113-005-1000-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liener UC, Suger G, Kinzl L. Knochen- und Gelenkinfekte. In: Wirth CJ, editor. Praxis der Orthopädie. Stuttgart, New York: Georg Thieme Verlag; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang EH, Simpson S, Bennet GC. Osteomyelitis of the calcaneum. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1992 Nov;74(6):906–909. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.74B6.1447256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feigin RD, McAlister WH, Joaquin VH, Middelkamp JN. Osteomyelitis of the calcaneus. Report of eight cases. Am J Dis Child. 1970 Jan;119(1):61–65. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1970.02100050063014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schildhauer TA, Bauer TW, Josten C, Muhr G. Open reduction and augmentation of internal fixation with an injectable skeletal cement for the treatment of complex calcaneal fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2000 Jun-Jul;14(5):309–317. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200006000-00001. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00005131-200006000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zwipp H, Rammelt S, Barthel S. Kalkaneusfraktur: Operative Technik. [Fracture of the calcaneus. Surgical technique]. Unfallchirurg. 2005 Sep;108(9):749–760. doi: 10.1007/s00113-005-1001-5. (Ger). Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00113-005-1001-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schofer M, Schoepp C, Rülander C, Kortmann HR. Operative und konservative Behandlung der Kalkaneusfrakturen. Trauma und Berufskrankh. 2005;7(Suppl 1):156–161. doi: 10.1007/s10039-004-0920-7. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10039-004-0920-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stephenson JR. Treatment of displaced intra-articular fractures of the calcaneus using medial and lateral approaches, internal fixation, and early motion. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1987 Jan;69(1):115–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanders R, Fortin P, DiPasquale T, Walling A. Operative treatment in 120 displaced intraarticular calcaneal fractures. Results using a prognostic computed tomography scan classification. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993 May;(290):87–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benirschke SK, Sangeorzan BJ. Extensive intraarticular fractures of the foot. Surgical management of calcaneal fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993 Jul;(292):128–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benirschke SK, Kramer PA. Wound healing complications in closed and open calcaneal fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2004 Jan;18(1):1–6. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200401000-00001. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00005131-200401000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Folk JW, Starr AJ, Early JS. Early wound complications of operative treatment of calcaneus fractures: analysis of 190 fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 1999 Jun-Jul;13(5):369–372. doi: 10.1097/00005131-199906000-00008. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00005131-199906000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Howard JL, Buckley R, McCormack R, Pate G, Leighton R, Petrie D, Galpin R. Complications following management of displaced intra-articular calcaneal fractures: a prospective randomized trial comparing open reduction internal fixation with nonoperative management. J Orthop Trauma. 2003 Apr;17(4):241–249. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200304000-00001. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00005131-200304000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andermahr J, Helling HJ, Rehm KE, Koebke Z. The vascularization of the os calcaneum and the clinical consequences. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999 Jun;(363):212–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rammelt S, Barthel S, Biewener A, Gavlik JM, Zwipp H. Calkaneusfrakturen – offene Reposition und interne Stabilisierung. [Calcaneus fractures. Open reduction and internal fixation]. Zentralbl Chir. 2003 Jun;128(6):517–528. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-40627. (Ger). Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1055/s-2003-40627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zwipp H. Chirurgie des Fußes. Wien, New York: Springer; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siebert CH, Hansen M, Wolter D. Follow-up evaluation of open intra-articular fractures of the calcaneus. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1998;117(8):442–447. doi: 10.1007/s004020050289. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s004020050289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rammelt S, Gavlik JM, Barthel S, et al. Management offener Calcaneusfrakturen. Hefte Unfallchirurg. 2000;282:29–30. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen K, Balloch R. Management of calcaneal osteomyelitis. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 2010 Jul;27(3):417–429. doi: 10.1016/j.cpm.2010.04.003. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpm.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giske CG, Monnet DL, Cars O, Carmeli Y. ReAct-Action on Antibiotic Resistance. Clinical and economic impact of common multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacilli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008 Mar;52(3):813–821. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01169-07. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AAC.01169-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rice LB. Federal funding for the study of antimicrobial resistance in nosocomial pathogens: no ESKAPE. J Infect Dis. 2008 Apr 15;197(8):1079–1081. doi: 10.1086/533452. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/533452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spellberg B, Guidos R, Gilbert D, Bradley J, Boucher HW, Scheld WM, Bartlett JG, Edwards J., Jr Infectious Diseases Society of America. The epidemic of antibiotic-resistant infections: a call to action for the medical community from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2008 Jan 15;46(2):155–164. doi: 10.1086/524891. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/524891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aragón-Sánchez FJ, Cabrera-Galván JJ, Quintana-Marrero Y, Hernández-Herrero MJ, Lázaro-Martínez JL, García-Morales E, Beneit-Montesinos JV, Armstrong DG. Outcomes of surgical treatment of diabetic foot osteomyelitis: a series of 185 patients with histopathological confirmation of bone involvement. Diabetologia. 2008 Nov;51(11):1962–1970. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-1131-8. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00125-008-1131-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Michelarakis J, Varouhaki C. Osteomyelitis of the calcaneus due to atypical Mycobacterium. Foot Ankle Surg. 2009;15(2):106–108. doi: 10.1016/j.fas.2008.07.003. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.fas.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abdelwahab IF, Klein MJ, Hermann G, Abdul-Quader M. Focal tuberculous osteomyelitis of the calcaneus secondary to direct extension from an infected retrocalcaneal bursa. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2005 May Jun;95(3):285–290. doi: 10.7547/0950285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baktiroglu L, Zeyrek F, Ozturk A, Yazgan P, Sirmatel O, Isikan E. Brucella osteomyelitis of the calcaneus. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2005 Mar-Apr;95(2):216–217. doi: 10.7547/0950216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tiemann AH, Krenn V, Krukemeyer MG, et al. Infektiöse Knochenerkrankungen. Pathologe. 2011 May;32(3):200–209. doi: 10.1007/s00292-011-1417-3. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00292-011-1417-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Braunschweig R, Bergert H, Kluge R, Tiemann AH. Bildgebende Diagnostik bei Osteitis / Osteomyelitis und Gelenkinfekten. Z Orthop Unfall. 2011 doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1270953. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1055/s-0030-1270953 10.1055/s-0030-1270953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hendrich C, Frommelt L, Eulert J. Septische Knochen- und Gelenkchirurgie. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer Verlag; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hofmann GO. Infektionen der Knochen und Gelenke. 1. Aufl. Urban & Fischer in Elsevier; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heier KA, Infante AF, Walling AK, Sanders RW. Open fractures of the calcaneus: soft-tissue injury determines outcome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003 Dec;85-A(12):2276–2282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lehmann S, Murphy RD, Hodor L. Partial calcanectomy in the treatment of chronic heel ulceration. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2001 Jul-Aug;91(7):369–372. doi: 10.7547/87507315-91-7-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bollinger M, Thordarson DB. Partial calcanectomy: an alternative to below knee amputation. Foot Ankle Int. 2002 Oct;23(10):927–932. doi: 10.1177/107110070202301007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baumhauer JF, Fraga CJ, Gould JS, Johnson JE. Total calcanectomy for the treatment of chronic calcaneal osteomyelitis. Foot Ankle Int. 1998 Dec;19(12):849–855. doi: 10.1177/107110079801901210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith DG. Principles of partial foot amputation in the diabetic. Foot Ankle Clin. 1997 Mar;2(1):171–186. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weinfeld SB, Schon LC. Amputation of the perimeters of the foot. Foot Ankle Clin. 1999;4(1):17–37. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zorrilla P, Salido JA, López-Alonso A, Silva A. Serum zinc as a prognostic tool for wound healing in hip hemiarthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004 Mar;(420):304–308. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200403000-00043. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00003086-200403000-00043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Simşek A, Senköylü A, Cila E, Uğurlu M, Bayar A, Oztürk AM, Işikli S, Muşdal Y, Yetkin H. Travma siddeti ile serum eser element duzeyi iliskili mi? [Is there a correlation between severity of trauma and serum trace element levels?]. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2006;40(2):140–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sadighi A, Roshan MM, Moradi A, Ostadrahimi A. The effects of zinc supplementation on serum zinc, alkaline phosphatase activity and fracture healing of bones. Saudi Med J. 2008 Sep;29(9):1276–1279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schmidt AB, Giessler GA. The muscular and the new osteomuscular composite peroneus brevis flap: experiences from 109 cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010 Sep;126(3):924–932. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181e3b74d. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181e3b74d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barbour J, Saunders S, Hartsock L, Schimpf D, O'Neill P. Calcaneal reconstruction with free fibular osteocutaneous flap. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2011 Jul;27(6):343–348. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1278713. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1055/s-0031-1278713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pelzer M, Reichenberger M, Germann G. Osteo-periosteal-cutaneous flaps of the medial femoral condyle: a valuable modification for selected clinical situations. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2010 Jul;26(5):291–294. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1248239. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1055/s-0030-1248239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Möllenhoff VG, Knopp W, Hebebrand D, Büttemeyer R. Die Abductor digiti minimi-Plastik: Ein lokaler Muskellappen zur Behandlung von Fersenbeinbruchen mit begrenztem Weichteilschaden. [Abductor digiti minimi-plasty: a local muscle flap for treatment of calcaneus fractures with limited soft tissue injuries]. Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir. 1995 Jul;27(4):220–222. (Ger). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schwabegger AH, Shafighi M, Gurunluoglu R. Versatility of the abductor hallucis muscle as a conjoined or distally-based flap. J Trauma. 2005 Oct;59(4):1007–1011. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000187967.15840.15. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.ta.0000187967.15840.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kilgore WB, Parrish WM. Calcaneal tumors and tumor-like conditions. Foot Ankle Clin. 2005 Sep;10(3):541–565. doi: 10.1016/j.fcl.2005.05.002. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.fcl.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]