Abstract

Bone remodeling is balanced by bone formation and bone resorption as well as by alterations in the quantities and functions of seed cells, leading to either the maintenance or deterioration of bone status. The existing evidence indicates that microRNAs (miRNAs), known as a family of short non-coding RNAs, are the key post-transcriptional repressors of gene expression, and growing numbers of novel miRNAs have been verified to play vital roles in the regulation of osteogenesis, osteoclastogenesis, and adipogenesis, revealing how they interact with signaling molecules to control these processes. This review summarizes the current knowledge of the roles of miRNAs in regulating bone remodeling as well as novel applications for miRNAs in biomaterials for therapeutic purposes.

Keywords: bone remodeling, microRNAs, osteoclastogenesis, osteogenesis

Introduction

Long-standing clinical observations indicate that numerous patients suffer from bone loss, bone defects, and bone non-union due to trauma, osteoporosis, osteoarthritis (OA), cancer, and other diseases. The leading edge in the prevention and treatment of these diseases is the study of how to promote osteogenesis and accelerate bone formation.1 Studies have revealed that bone tissue is continuously remodeled throughout the lifetime to create new bones and to maintain normal bone homeostasis. Mature bone tissue is maintained through the balancing activities of bone-forming osteoblasts, which originate from mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), and of bone-resorbing osteoclasts, which arise from haematopoietic stem cells (HSCs).2 In recent years, investigators have unraveled several key signaling mechanisms involved in the regulation of these cells at both the genetic and molecular levels, including major signaling pathways, such as the Notch,3 bone morphogenetic protein (BMP),4 canonical WNT,5 and the receptor activator of nuclear factor κB (RANK)-osteoprotegerin (OPG)-and RANK ligand (RANKL) pathways,6 which are critical for bone formation and resorption. In addition to these genetic mechanisms, bone functions are also controlled by epigenetic mechanisms, which include the regulation of genes by DNA methylation, microRNA (miRNA) function, and chromatin architecture modification.7 miRNAs, which are considered the key epigenetic mechanisms for the control of expressed genes, provide a novel dimension to the post-transcriptional control of cells involved in bone remodeling by inhibiting mRNA translation.8,9 However, the current understanding of how miRNAs mediate the regulatory interplay between and among different cells in bone remodeling is minimal, and the role of miRNAs in the differentiation and function of mature cells derived from MSCs or HSCs remains to be elucidated. Herein, we review the role of miRNAs in the regulation of bone remodeling and discuss their implications as promising therapeutic targets.

Bone Remodeling and Its Transcriptional Regulation

Bone remodeling is a dynamic process regulated by numerous biological factors and signals.10 Osteocytes, which act as sensors of chemical signals and mechanical loading, orchestrate bone activity and communicate with osteoblast and osteoclast effectors.11 Osteoblasts are differentiated from MSCs, and they play a critical role in the production and mineralization of extracellular matrix.12 In addition, osteoblasts can regulate the differentiation of osteoclasts. Currently, several transcription factors (TFs) in bone development have been identified, such as runt-related transcription factor 2 (Runx2) and Cbf β, which are key factors both in bone formation and osteoblast differentiation.13

Osteoclasts are essential bone-resorbing cells during bone homeostasis and regeneration. They originate from HSCs or haematopoietic progenitors in the monocyte/macrophage lineage. The TF PU.1 contributes to the early stage of osteoclastogenesis. Microphthalmia-associated transcription factors (MITF) and transcription factor E3, located downstream of macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF)/c-fms and RANKL/RANK, are also important in the differentiation of monocytic osteoclast precursors into multinucleated osteoclasts.14 In addition to these signaling factors, abundant transcriptional factors have been shown to be involved in bone remodeling.11,15

miRNAs: Definition and Biological Functions

miRNAs are short, single-strand, non-coding RNAs approximately 20–25 nucleotides in length that have emerged as a novel mechanism capable of post-transcriptionally regulating the expression of mRNAs and proteins.16 They can silence their cognate target genes by inhibiting mRNA translation or degrading the mRNA molecules by binding to their 3′-untranslated regions (UTR).17 The transcription of miRNAs is mostly modified by RNA polymerase II, and it can also be performed by RNA polymerase III.18 Sequences encoding miRNAs are often found around the genome as separate transcriptional units, located within the introns of coding genes.19 The 5′ ends of mature miRNAs contain the seed region (nucleotide positions 2–7 or 2–8), which has the ability to identify the complementary bases of the 3′-UTR of the target mRNAs and trigger their degradation.20

miRNAs have been found to be involved in multiple biological processes, including cell differentiation, cell proliferation, development timing, apoptosis, transposon silencing, and antiviral defense.21 Hundreds of miRNAs, which are evolutionarily conserved, have been identified in humans.22 So far, more than 3% of the genes in humans have been identified as encoding for miRNAs, and approximately 40% to 90% of the human protein-encoding genes are under miRNA-mediated gene regulation.23 Therefore, numerous miRNAs have been found to be involved in the regulation of bone homeostasis, and they play critical roles in bone remodeling (Table 1).

| Targets | miRNAs | Sample resources | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Osteogenesis inhibited | |||

| Runx2 | miR-34c | ||

| miR-133a | |||

| miR-135a | |||

| miR-137 | |||

| miR-205 | MC3T3-E1 | [33] | |

| miR-217 | |||

| miR-338 | |||

| miR-23a | MC3T3-E1 | [33,34] | |

| miR-30c | MC3T3-E1, hADSCs | [33,35,36] | |

| miR-204/211 | MC3T3-E1, C3H10T1/2, ST2, hMSCs | [33,37,38,70] | |

| miR-103a | hFOB 1.19, C57BL/6J mice | [45] | |

| Cbfβ | miR-125b | BMSCs, C3H10T1/2, ST2 | [39,40,41,42] |

| JMJD3 | miR-146a | hMSCs | [32] |

| Smad1 | miR-30 | MC3T3-E1, BMSCs | [35] |

| SATB2 | miR-23a∼27a∼24-2 | MC3T3-E1 | [50] |

| miR-31 | hMSCs | [55] | |

| miR-34b/c | Mouse osteoblasts, C2C12, miR-34a/b/c−/− mice | [52,53] | |

| Notch1/2, JAG1 | miR-34a/c | hMSCs, miR-34c Tg mice | [53,219] |

| Osx | miR-31 | hMSCs | [62] |

| miR-93 | MC3T3-E1 | [63] | |

| miR-143 | MC3T3-E1 | [64,66] | |

| miR-145 | MC3T3-E1, C2C12 | [65,66] | |

| miR-637 | hMSCs | [67] | |

| miR-214 | hMSCs | [68] | |

| Smad1 | miR-26a/b | hADSCs, USSCs | [75] |

| Smad5 | miR-135b | hMSCs, C2C12, hUSSCs | [76,77,78] |

| BMPR2 | miR-100 | hADSCs | [80] |

| BMP2 | miR-17-5p | hADSCs | [79] |

| miR-106a | |||

| miR-140-5p | hMSCs | [81] | |

| TCF3 | miR-17 | hPDLSCs, NOD/SCID mice | [87] |

| CDC25A | miR-141-3p | hMSCs, ST2 | [91] |

| ATF4 | miR-214 | MC3T3-E1, human osteoporotic bone specimens | [101] |

| COL1A1, Col5A3 | miR-29a/b | Rat osteoblasts, MC3T3-E1 | [140,141] |

| SOCS1 | miR-155 | MC3T3-E1 | [210,211] |

| Fas | miR-23a | MC3T3-E1 | [214] |

| FAK | miR-138 | hMSCs, MC3T3-E1 | [113] |

| Fgfr2 | miR-233 | MC3T3-E1, C3H10T1/2, ST2 | [115] |

| miR-338 | BMSCs, OVX mice | [116] | |

| Cx43 | miR-206 | C2C12, Cx43−/− mice | [119] |

| Dlx5 SVCT2 | miR-141/200a | MC3T3-E1 BMSCs | [120] [121] |

| Dlx5/Msx2 | miR-124a/181a | iPS cells, hMSCs, BMSCs, MC3T3-E1, C2C12 | [122,123] |

| IGF2 | miR-30e | BMSCs, SMCs, ApoE−/− mice | [230] |

| Osteogenesis promoted | |||

| Tob2 | miR-322 | BMSCs, MC3T3-E1, C2C12 | [69] |

| Smurf1 | miR-15 | hMSCs | [159] |

| PPARγ | miR-20a/b | hMSCs | [133,134] |

| miR-548d-5p | hMSCs | [132] | |

| Bambi, Crim1 | miR-20b | hMSCs | [133] |

| DDK1 | miR-335-5p | C3H10T-1/2 | [139] |

| miR-29a/c | hFOB1.19, MC3T3-E1 | [19,141] | |

| Kremen2, SFRP2 | miR-29a/c | hFOB1.19, MC3T3-E1 | [19,141] |

| DDK2, SFRP2, SOST | miR-218 | hADSCs, MC3T3-E1, BMSCs | [137,138] |

| Hoxa2 | miR-3960 | Mouse osteoblasts | [151] |

| Axin2 | miR-let-7 | hMSCs | [142] |

| HMGA2 | hADSCs | [231] | |

| APC | miR-27 | hFOB1.19 | [144] |

| SFRP1 | [143] | ||

| HDAC1 | miR-449a | Human iPS cells | [148] |

| HDAC4 | miR-29b | MC3T3-E1, USSCs | [141,149] |

| HDAC5 | miR-2861 | Mouse osteoblasts, ST2, OVX mice | [150,151] |

| HDAC6 | miR-22 | hADSCs | [153] |

| HDAC9 | miR-188 | BMSCs, 188-Tg mice | [154] |

| TFG-βi/Alk5 | miR-181a | MC3T3-E1, C2C12 | [156] |

| Acvr1b | miR-210 | ST2, NRG cells | [157] |

| Smad2/3 | miR-146a | Fetal femur-derived cells | [158] |

| COUP-TFII | miR-194 | BMSCs | [161] |

| miR-302a | MC3T3, C2C12 | ||

| HB-EGF | miR-96 | BMSCs, MC3T3-E1,OVX mice | [163] |

| miR-1192 | C2C12/Runx2Dox cells | [164] | |

| Spry1 | miR-21 | hMSCs, OVX mice | [213] |

| SOX2 | SS-AF-hMSCs | [232] | |

| SPARC | miR-29a | ABSa15 | [88] |

| STAT1 | miR-194 | BMSCs | [233] |

| Hoxa8 | miR-196a | hADSCs | [234] |

| CHIP/STUB1 | miR-764-5p | MC3T3-E1, mouse osteoblasts | [235] |

| Osteoclastogenesis inhibited | |||

| RANK | miR-503 | PBMCs | [174] |

| TRAF6 | miR-125a | PBMCs | [175] |

| NFATc1 | miR-124 | BMMs | [176] |

| FasL | miR-21 | BMMs, osteoclast precursors, CAG-Z-miR-21-EGFP transgenic mice | [183] |

| CTGF | miR-26a | Murine osteoclasts | [186] |

| NFI-A | miR-233 | RA/OA patients | [168] |

| SOCS1, MITF | miR-155 | FNb−/−/IFNAR1−/− mice, RAW264.7 | [211] |

| Tgif2 | miR-34a | Tie2-cre mice, 34a-KO/Het mice, OVX mice,34a-Tg mice | [220] |

| DC-STAMP | miR-7b | RAW264.7 | [236] |

| Osteoclastogenesis promoted | |||

| PIAS3 | miR-9718 | RAW 264.7 | [172] |

| RhoA | miR-31 | BMMs | [177] |

| PDCD4 | miR-21 | BMMs, c-Fos−/− mice | [181] |

| MAFB | miR-148a | PBMCs | [184] |

| Pten | miR-214 | BMMs, RAW 264.7, OC-214Tg mice | [200] |

hMSC, human mesenchymal stem cell; BMSC, bone marrow stem cell; ADSC, adipose-derived stem cell; PDLSC, periodontal ligament stem cell; USSC, cord blood stem cell; MC3T3-E1, mouse osteoblastic cell line; C2C12, mouse premyogenic cell line; ST2, mouse bone marrow stromal cell line; SMC, aortic smooth muscle cell; hFOB1.19, human osteoblastic cell line; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell; BMM, bone marrow macrophage; RAW264.7, Murine macrophage cell line; OVX mice, ovariectomized mice; PDCD4, programmed cell death 4; MAFB, V-maf musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma oncogene homolog B.

miRNAs in Osteoblast Lineage and Bone Formation

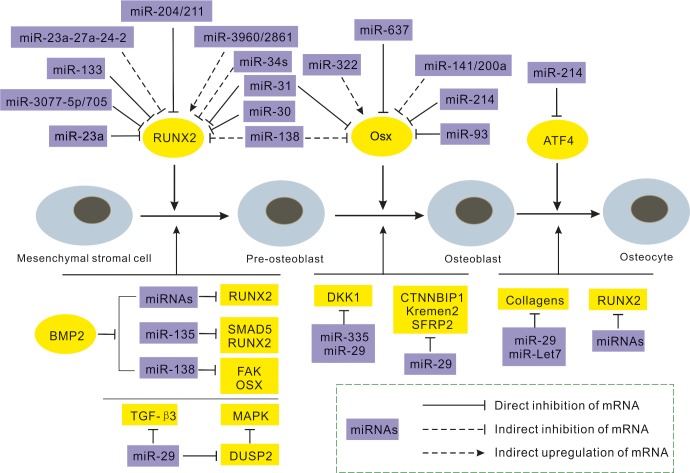

MSCs are the sources of osteoblasts, chondrocytes, and adipocytes. They differentiate into osteoblast lineages, determined by a variety of osteogenic factors and signals, which are regulated by post-transcriptional control, and miRNAs are among the most crucial, validated members (Figure 1). The inactivation of Dicer, which is a prerequisite for the manufacture of canonical miRNAs, leads to bone defects and impaired mineralization during the embryonic stage and a delayed increase in bone mass during the post-natal stage.24 In addition, miRNAs can bind to target sequences in the UTR of mRNAs, leading to translational arrest or causing the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) to degrade messages.25 Therefore, miRNAs can display considerable enhancing or inhibitory functions in osteogenesis by binding to important osteogenic TFs.26

Figure 1.

Schematic summary of miRNAs implicated in osteoblast differentiation. This figure indicates the major activities of miRNAs influencing the continuous maturation of cells from mesenchymal stromal cells to osteocytes. Selected miRNAs (purple) relative to their targets (yellow) and influencing each stage to regulate the progression of differentiation are indicated. BMP, bone morphogenetic protein.

miRNAs that inhibit osteogenesis

Runt-related transcription factor 2

Runt-related transcription factor 2 (Runx2) – also referred to as core-binding factor α1 (Cbfα1), osteoblast-specific factor 2 (Osf2), polyomavirus enhancer binding protein (PEBP2a2), and acute myeloid leukemia gene 3 (AML3) – acts as a core TF in the regulation of osteogenesis.27 Runx2 binds to osteoblast-specific cis-acting element (OSE2), which exists in the promoter region of osteogenic-related genes, such as bone gamma-carboxyglutamic acid-containing protein (BGLAP), secreted phosphoprotein 1 (SPP1), collagen type I alpha 1 (COL1A1), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), and bone sialoprotein (BSP).28,29 It is primarily required for the induction of osteoblast differentiation rather than for adipogenesis or chondrogenesis, while ossification is suppressed when Runx2 is overexpressed during osteoblast maturation.30,31 It has also been found that Runx2 expression can be affected by multiple epigenetic regulatory mechanisms, including a methylation regulatory circuit in which jumonji domain-containing 3 (JMJD3) acts as a histone demethylase to increase Runx2 levels via the negative modulation of histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation (H3K27 me3), and miR-146a targets JMJD3 to reverse osteogenic differentiation.32

miRNA microarray is a common method for the screening of miRNAs because it has been discovered that 10 miRNAs (miR-23a, miR-30c, miR-34c, miR-133a, miR-135a, miR-137, miR-204, miR-205, miR-217, and miR-338) inhibit osteoblast differentiation in MC3T3-E1 premature osteoblasts by directly targeting Runx2, showing either high or medium levels.33 They also target TRPS1 (except for miR-137, miR-204, and miR-338) to redirect MSCs to adipogenic cell fates.34 Moreover, members of the miR-30 family have been shown to target both Runx2 and Smad1, acting as key regulators in bone mineralization in BMP-2-mediated osteogenesis and stimulating adipogenesis in hADSCs.35,36 miR-204 and its homolog miR-211 act as endogenous attenuators of Runx2, inhibiting osteogenesis instead of adipogenesis in C3H10T1/2 and ST2 cell mesenchymal progenitor cells and human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs), as well as contributing to vascular smooth-muscle cell (VSMC) calcification.37,38 miR-125b is also involved in the inhibition of osteoblastogenesis, and ErbB2 has previously been verified as a target gene.39 Recently, another target, Cbf β, has been found, which is a cofactor enhancing Runx2 activity, causing miR-125b to indirectly act on Runx2 during the early stages of osteogenesis.40 In addition, miR-125b is significantly increased in the hMSCs derived from senile osteoporotic patients, and osterix (Osx) levels change,41 establishing the potential role of miR-125b in bone disease therapy, although a contradiction occurred in the ‘gain and loss' experiments of miR-125b in vitro.42 In this case, miRNAs and their targets vary accordingly across different osteogenesis stages, and in vivo research is needed to elucidate the mechanism.

Recent studies have found and affirmed some specific miRNAs functioning in cyclic mechanical stretch-induced osteoblast differentiation,43 especially in human periodontal ligament cells (PDLCs) and alveolar bone cells (ABCs). For example, miR-29b and miR-103a act as mechanosensitive regulators post-transcription, and they can also target Runx2 to suppress osteoblasts activity and bone mineralization.44,45 These new findings will broaden our horizons in considering the triangular relationship between miRNA, mechanics and bone remodeling.

Special AT-rich sequence-binding protein 2

Special AT-rich sequence-binding protein 2 (SATB2) binds to nuclear matrix attachment regions and interacts synergistically with Runx2, promoting osteoblast differentiation and positively regulating the expression of osteoblast-specific genes, such as BSP, osteocalcin (OCN), Osx, and vascular endothelial growth factor A.46,47 Gel shift assays have shown that Osx, as an upstream regulator, binds directly to the SATB2 promoter sequence, while conversely, SATB2 up-regulates Osx dependently or independently of Runx2.47,48 In addition, SATB2 has also been found to be a novel marker of osteoblast differentiation in some mesenchymal tumors.49

Study of the miR-23a∼27a∼24-2 cluster indicates a ‘feed-forward' regulatory circuit in the osteoblast lineage. Each of the components targets SATB2 directly and is suppressed by Runx2 in the mineralization stage, leading to osteoblastogenesis and attenuation by Hoxa10 and Runx2 targeted by miR-27a and miR-23a.50 However, miR-23a has failed to play such a role in animal research,51 which should trigger discussion regarding why discrepancies have occurred in in vitro and in vivo studies. In addition, in vivo research has discovered that the miR-34 family inhibits osteoblast differentiation in the terminal stage by targeting SATB2, while it inhibits osteoblast proliferation by targeting cyclin D1, CDK4, and CDK6, thus suppressing bone formation.52,53 Recently, seeding anti-miR-31-modified bone marrow stem cells (BMSCs) onto poly(glycerol sebacate) (PGS) scaffolds showed significant generation of critical-sized bone defects,54 and miR-31 was shown to suppress osteogenesis by targeting SATB2 in hMSCs.55 At the same time, miR-31 is directly suppressed by Runx2, forming a feedback loop in the regulatory circuit of miR-31, Runx2, and SATB2.56

Osx

Osx, also called Sp7, is a special zinc-finger-containing TF required for bone formation and bone homeostasis. Deletion or deactivation of Osx in mice led to spinal deformities.57 Osx has been found downstream of Runx2, and it is involved in several pathways, such as MAKP signaling.58,59 In addition, the BMP-2-mediated induction of Osx may be inhibited by blocking Runx2.60,61

As mentioned above, miR-31 targets primarily SATB2, but it also directly regulates the Osx 3′-UTR during the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs. At the same time, five miRNAs were found to be modulated during the mineralization process.62 miR-93 has been found to target Osx in osteoblast mineralization and to be negatively regulated by Sp7, forming a feedback loop.63 miR-143 and miR-145 directly target Osx and act as crucial regulators of osteogenic differentiation,64,65 consisting of another feedback loop with Klf4 and Osx in odontoblast differentiation, thus suggesting a complex but relevant application for osteogenesis.66 miR-637 has been indicated as being indispensable for maintaining the balance of osteogenesis and adipogenesis by targeting Osx in hMSCs.67 For C2C12 myoblast cells, miR-214 has been verified as a new regulator of Osx to suppress osteogenic differentiation.68 Researchers have also found that Osx may be positively modulated by miR-322 targeting of Tob2, which binds to Osx and regulates Osx degradation.69 Controlled by Osx, miR-133a and miR-204/211 are down-regulated, with their Runx2 targets up-regulated.37 In addition, miR-133a and miR-204/211 can negatively regulate ALP and Sost, which antagonize Wnt and enhance Runx2, to form an intricate loop.70

Smads

The Smad factor is a crucial intracellular receptor that participates in canonical Transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) and BMP superfamily pathways, and it separately activates RSmad2/3 and Rsmad1/5/8 signals.71 Activated Rsmads form a complex bond with Co-Smad4 and translocate into nuclei to regulate responsive genes.72 Smad acts as a common stimulator of osteogenesis and bone regeneration in a number of mechanisms, such as its interaction with Runx2.73 Smad directly induces Msx2 to increase Osx expression, and it is involved in many other pathways.72 However, a non-Smad pathway exists in BMP-7-induced osteogenesis, which regulates the proliferation and survival of osteoblasts.74

miR-26a, which is involved in BMP pathways, can also target Smad1 to guide osteoblast differentiation.75 MSCs derived from multiple myeloma (MM) patients showed impaired bone formation and higher miR-135b, which targets Smad5 to control bone disease and C2C12 mesenchymal cells and human umbilical cord blood-derived unrestricted somatic stem cell (USSC) differentiation.76,77,78 BMP2 and BMPR2 can also be targeted directly by miR-17-5p, miR-106, miR-100, and miR-140-5p and by decreased osteogenic TAZ, Msx2, and Runx2 through Smad1/5, while inducing adipogenesis.79,80,81 Conversely, miR-17-5p plays a key role in this reaction and was recently proven to target Smad7. It can also increase the Runx2 and COL1A1 levels and promote nuclear translocation of β-catenin, preventing non-traumatic osteonecrosis and maintaining bone remodeling to some extent.82 miR-542-3p can also target BMP-7, inhibiting both Smad-mediated osteoblast differentiation and BMP-7/PI3K-survivin non-Smad-induced proliferation.74 In contrast, inhibition of miR-203 may rescue suppressed PI3K expression and stem cell activity.83

β-catenin

β-catenin is a master downstream multi-functional protein, which is actively involved in the canonical Wnt signaling pathway and displays characteristics essential for determining the differential direction of MSCs,84,85 forming an intricate network in different stages and microenvironments.86,87 In this pathway, miR-29a may induce β-catenin protein levels,88 but conversely, when β-catenin degradation was inhibited, it accumulated and localized in the nuclei of active T-cell factor (TCF)/lymphoid enhancer factor (LEF), which regulates target gene expression.89 TCF3 has been elucidated as an enhancer of osteogenesis both in vivo and in vitro, and miR-17 is a direct modulator of TCF3.87 Additionally, both β-catenin and TCF can be down-regulated if low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 6 (LRP6), a co-receptor of Wnts, is blocked by miR-30e in the early stage of stem cell differentiation.90 Moreover, a major regulator of the cell cycle, called cell division cycle 25A (CDC25A), can be knocked down by miR-141-3p in the initial phase of the osteoblast differentiation of human stromal stem cells.91

Activating transcription factor 4

Mice with activating TF (ATF) 4 deficiency (ATF4−/−) display severely reduced boss mass and bone toughness, as well as decreased COL1A1 synthesis.92,93 As a crucial transcriptional factor in bone formation, ATF4 works with Runx2 and Osx. ATF4 regulates OCN expression positively by binding to osteocalcin-specific element (OSE1), and it interacts cooperatively with Runx2 through SATB2.92,94,95 Factors inhibiting ATF4-mediated transcription (Fiat) have been found to suppress ATF4 activity and, co-expressed in osteoblasts96,97 and modulated by the Sp family, to exclude Osx.98 In the matrix mineralization stage, ATF4 is positively regulated, to a large extent, by c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), affecting the expression of OCN and BSP.99 Moreover, ATF4 can also bind to the promoter of RANKL and can ultimately inhibit bone resorption.100 Recently, high miR-214 levels were found in samples from older individuals with lower BGLAP and ALP levels, verified by their inhibitory roles in bone formation by targeting ATF4 directly, thus providing a vital potential therapy from ameliorating osteoporosis.101

TAZ

Transcription coactivator with binding capacity to PDZ motifs (TAZ) is a 14-3-3-binding transcriptional modulator with WW domains that binds to the motifs in many bone-related transcriptional genes to determine stem cell fate. During osteogenic differentiation, TAZ can be induced by extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), activated by FGFs.102 It can also be facilitated by PP1A-induced Wnt3a,103 and some chemical compounds, such as phorbaketal A and TM-25659, have been shown to modulate TAZ.104,105 In addition, TAZ can coactivate with Runx2-dependent genes (such as OCN) to activate osteogenesis while suppressing PPARγ-dependent gene transcription (such as of adipocyte protein 2) to block adipogenesis.106,107 miR-17-5p has been confirmed to regulate BMP2 and to participate in TAZ-regulated Runx2 and PPARγ modulation.79 Moreover, TNF can activate NF-κB, which induces osteogenesis via subsequent up-regulation of TAZ expression, but miR-146a inhibited all of these processes.108

Another nuclear TF, called Yes-associated protein (YAP), coactivates with TAZ, and YAP/TAZ are key downstream effectors of Hippo signaling, which has been defined as necessary for the Dicer-mediated pre-miRNA process.109,110 YAP/TAZ are key mechanical signals influenced by extracellular matrix rigidity and cell shape, and they have determinable effects on cell fate.111,112

Focal adhesion kinase

Focal adhesion kinase (FAK), which is encoded by the PTK2 gene, facilitates contact between ECM proteins and activation of ERK1/2, namely via the ERK-dependent pathway, which is found to be concentrated on the transcriptional regulation of bone formation. Downstream cascade Runx2 phosphorylation and Osx expression are affected accordingly. Previous studies have indicated that FAK was targeted by miR-138, and it blocked such pathway-inhibited bone formation.113 New research has found that platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) acts as the upstream regulator of miR-138.114

In addition, ERK1/2 phosphorylation and its pathway can also be blocked by fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (Fgfr2), which is a critical regulator of osteogenesis and bone tissue regeneration. Conversely, CCAAT/enhancer binding protein α (C/EBPα) and PPARγ can be activated, with miR-233 and miR-338-3p targeting Fgfr2, resulting in a feedback loop.115,116

Other targets

In addition to these mutual targets preferred by respecle miRNAs, there are still some crucial and special targets mediated by a small number of miRNAs.

Connexin 43(Cx43), belonging to the gap junction proteins family, is mainly expressed in the vasculature, ventricular myocardium, and astrocytes. While Cx43-deficient mice showed decreased bone mass due to osteoblast dysfunction,117 it was surprising to find that miR-206, a muscle-related miRNA,118 inhibited osteoblast differentiation by targeting Cx43 in osteoblasts. Transgenic mice with specifically expressed miR-206 in osteoblasts showed this result as well, resulting in a significant decrease in the bone formation rate.119

Distal-less homeobox 5 (Dlx5), a member of a homeobox TF gene family, is also regarded as one of the osteogenic TFs. miR-141 and miR-200a are members of the miR-200 family and have been identified as targeting Dlx5 to affect the transcriptional expression of Osx indirectly,70,120 as well as targeting sodium-dependent vitamin C transporter 2 (SVCT2) to suppress osteogenic differentiation.121 Furthermore, miR-124a and miR-181a were predicted and verified to regulate the differentiation of iPS cells into osteoblasts by targeting Dlx5 and Msx2, respectively,122 and in vivo ectopic bone formation assay strengthened these findings.123

miRNAs in promoting osteogenesis

PPARs

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs), which belong to the ligand-dependent activated nuclear hormone receptor gene superfamily, include PPARβ, PPARδ, and PPARγ. PPARγ plays a decisive role in adipogenic differentiation and therefore in the regulation of osteogenesis.124,125 Adipogenesis occurs through the activation of C/EBPβ and C/EBPδ, which activate C/EBPα and PPARγ, respectively.126 PPARγ−/− ES cells and PPARγ+/− mice show enhanced osteoblastic differentiation, with high bone mass but normal osteoblast functions.127 In addition, the existence of PPARγ suppresses Runx2 activity and subsequent osteocalcin expression.128 It can also induce β-catenin degradation.129 Recent epigenetic research has found that DNA hypermethylation prevented PPARγ from activating C/EBPα and that histone deacetylase (HDAC) 1 occupied the region of and disequilibrated the balance between osteogenesis and adipogenesis.130 Nevertheless, the stimulatory role of PPARγ has been found not only to promote adipogenic differentiation but also to induce osteogenesis by BMP2 when PPARγ is overexpressed.131 Recently, miR-548d-5p was found to directly target PPARγ when C/EBPα levels were decreased, which may suppress adipogenesis rather than osteogenesis.132 When BMP2 is inhibited by miR-17-5p and miR-106a, Runx2, TAZ, and Msx2 decrease, which decreases their ability to inhibit PPARγ, which leads to adipogenesis.79 miR-20a and miR-20b share the same function in directly repressing PPARγ, with Bambi and Crim1 activating the BMP/Runx2 pathway to enhance osteogenesis.133,134,135

Wnt inhibitors

Wnt inhibitors consist of the Dickkopf family (DKK) and the secreted frizzled-related family (SFRP), which competitively combine with LRP5/6 to inhibit Wnt signaling.135 Numerous intracellular factors, such as APC, Axin, GSK3, NLK, and NKD, are also negative regulating proteins.136 miR-218 has been repeatedly proven to be an up-regulator of osteogenic differentiation in hADSCs and osteoprogenitors, and the direct targets of miR-218 are DKK2, SFRP2, and sclerostin (SOST), while Wnt3a signals up-regulate miR-218, forming a ‘feed-forward' regulatory circuit.137,138 DKK1, which is another important DKK family member, is directly targeted by miR-335-5p.139 Moreover, the miR-29 family plays crucial roles in osteogenesis by suppressing osteonectin expression rather than reducing collagens and extracellular matrix proteins.19,140,141 Furthermore, Axin2 can be decreased by high levels of miR-let-7 in tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1−/− (TIMP1−/−) hMSCs, which is another antagonist of β-catenin and increases osteoblast differentiation.142 Adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) and sFRP1 inhibition by miR-27 share the same mechanism.143,144

HDACs

HDACs are a class of enzymes that modify chromatin structure and transcriptional activity balanced by histone acetyltransferase (HAT). HDACs are Runx2 inhibitors: HDAC1 down-regulates histone acetylation levels, and HDAC4/5 are recruited to interact with Smad3, forming a co-repressor complex to inhibit osteoblast differentiation,145,146,147 while miR-449a was detected to target HDAC1 in human iPS cells,148 and miR-26a/b and miR-29 targeted HDAC4 and CDK6 in USSCs.141,149 Two other enhancers of Runx2 degradation, HDAC5 and Hoxa2, are inhibited by miR-3960 and miR-2861, respectively, and they can be up-regulated by Runx2 to form an amplification loop.150,151 Moreover, deficiency in HDAC6, which is targeted by miR-22, leads to increased mouse trabecular bone density.152,153 HDAC9 also plays a switchable role in deciding the direction of stem cell differentiation, which decreases in age-dependent adipogenesis, and transgenic miR-188 mice targeted for HDAC9 showedincreased bone loss and fat accumulation.154

BMP/TGF-β/activin receptors

The TFG-β/Smads pathway is also involved in osteogenesis. Anti-mir-221-transfected USSCs showed increased expression of SMAD3 and TGF-βR and up-regulation of osteogenesis.155 miR-181 suppressed TGF-β signaling by inhibiting TFG-βi (TFG-β-induced) and TGF-βRI, which are both osteoblastic-negative regulators.156 Activin receptor type-1B (AcvR1b), which belongs to TGF-β superfamily, transmitting signals to activate Rsmad2/3. With miR-210 targeting AcvR1b directs and miR-146a targets Smad2/3,157,158 TGF-β signaling is inhibited, and osteoblastogenesis is promoted. Additionally, Smad-specific E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 1 (Smurf) has been reported to bind with miR-15 and to degrade Runx2.159 The miR-497∼195 cluster, a member of the miR-15 family, has similar functions.160 Interestingly, chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter-transcription factor II (COUP-TFII), targeted by miR-194 and miR-302a, plays critical roles in inhibiting BMP-2-induced osteogenesis.161,162

Other targets

In situations such as osteoblast inhibition, there are some novel target genes and pathways involved in the process of osteogenesis that cannot be ignored. Heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor (HB-EGF), which is a member of the epidermal growth factor (EGF) family, is likely to bind to epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and can activate the downstream factors ERK1, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt, JNK, and c-Jun to proceed to the HBEGF–EGFR signaling pathway, which exerts effects on many physiological processes, including bone formation. miR-96, which has previously been recognized as a crucial mediator in cancer, has also been found to be a positive regulator of osteogenic differentiation by targeting HB-EGF.163 miR-1192, which can be up-regulated by Runx2, showed the same effects.164 Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells (hUMSCs) have also been used to test the osteogenesis ability controlled by miRNA. PI3K/Akt signaling is activated, and the downstream β-catenin cascade is increased obviously after miR-21 treatment.165

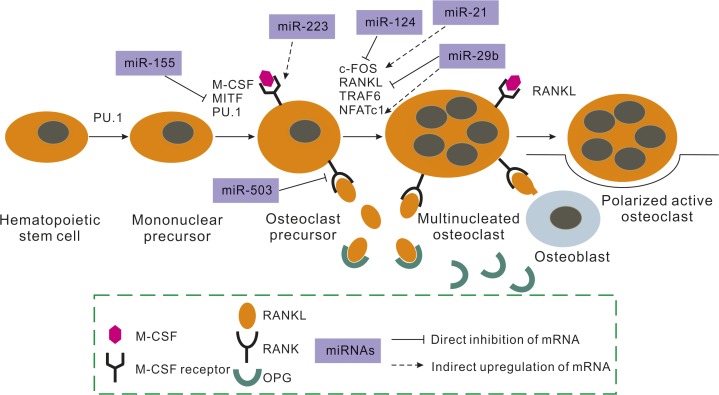

miRNAs in Osteoclast Lineage and Bone Resorption

Osteoclasts, which are derived from immature mononuclear phagocytic cells that originate from HSCs, make a significant contribution to bone resorption in bone remodeling processes. They have been shown to be regulated by numerous cytokines and exogenous hormones.166,167 miRNAs have also been validated as vital regulators of osteoclasts by knocking out the osteoclast-specific Dicer gene.168 In addition, researchers have found that DiGeorge syndrome critical region gene 8 (DGCR8)-dependent miRNAs are indispensable for osteoclastogenesis.169 To date, the mechanism of how miRNAs work in osteoclastogenesis has been thoroughly researched, although to a lesser extent than that in osteogenesis (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Effects of miRNAs on osteoclast differentiation. This figure indicates the major activities of miRNAs influencing osteoclast commitment. miRNAs affect different molecular mechanisms related to this commitment, such as RANK or M-CSF receptor, among others. miRNA expression leads to alterations in osteoclast activity in vitro and changes in bone resorption in vivo. M-CSF, macrophage colony-stimulating factor; OPG, osteoprotegerin; MITF, microphthalmiaassociated transcription factor; RANK, receptor activator for nuclear factor κB; RANKL, RANK ligand; NFATc1, nuclear factor of activated T-cell calcineurin-dependent 1.

RANK

Receptor activator for nuclear factor κB (RANK) is a type I membrane protein expressed on osteoclast precursors to activate osteoclast formation in combination with RANK ligand (RANKL) on the surfaces of osteoblasts, osteocytes, stromal cells, and T-cells by means of intimate cell–cell contact via ligands and receptors.170,171 In the downstream cascade, transduction factor TNF receptor-associated factors (TRAFs), especially TRAF6, can bind to RANK to activate NF-κB and the JNK/AP-1 pathway.166 c-Fos, which is another determinant transcriptional factor in osteoclast functions, is also RANKL-induced and can improve osteoclast differentiation,170 but c-Fos-mediated osteoclast-associated receptor (OSCAR) and nuclear factor of activated T-cell calcineurin-dependent 1 (NFATc1) may be attenuated by protein inhibitor of activated STAT 3 (PIAS3) to suppress osteoclastogenesis.172 In this system, a natural decoy receptor for RANKL, called osteoprotegerin (OPG), can compete with RANK to prevent osteoclast maturation, while M-CSF can up-regulate RANK expression.173

Currently, researchers have reported that peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from post-menopausal osteoporosis patients expressed markedly low levels of miR-503, and RANK has been verified as a direct target of miR-503, the inhibition of which promotes RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption both in vitro and in vivo.174 In the downstream signals, TRAF6 is directly targeted by miR-125a, while NFATc1, which is activated by NF-κB, can bind to the promoter of miR-125a and inhibit the suppressing function of TRAF6.175 miR-124, a specific suppressor of NFATc1, can regulate osteoclast differentiation, proliferation, and migration.176 The expression of RhoA, which controls the formation of actin stress fibers and focal adhesions, is suppressed and stabilized by miR-31, an important up-regulated miRNA in osteoclast formation, to influence osteoclast motility.177,178 NFATc1, a cofactor of activator protein-1 (AP-1), consists of Fos/Jun proteins.179 It can enhance the expression of the osteoclast-specific markers tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) and cathepsin K, and it is therefore an indispensable TF for RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis.180 c-Fos triggers the expression of miR-21, which can down-regulate programmed cell death 4 (PDCD4) protein levels to activate c-Fos, forming a positive ‘feed-forward' loop.181 Furthermore, miR-21 has been verified to play a critical role in particle-induced osteolysis (PIO),182 and estrogen has been found to regulate miR-21 negatively by c-Fos inhibition and Fas ligand (FasL), the target of miR-21, to induce osteoclast apoptosis.183 Further studies have also found that miR-148a can inhibit V-maf musculo-aponeurotic fibrosarcoma oncogene homolog B (MAFB), which can attenuate the transactivation of NFATc1 and the binding ability of c-Fos DNA, to enhance osteoclastogenesis.184 In addition, connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) has the dual ability of promoting endochondral ossification and increasing RANKL-mediated osteoclastogenesis.185,186

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is an autoimmune disease in which osteoclasts make major contributions to bone destruction and in which the cross-talk between RANKL and interferon-γ plays a critical role.187 Evidence has emerged indicating that miRNAs are also involved in the pathogenesis of RA. In two groups of miR-155−/− mice with collagen-induced arthritis (CIA) and K/BxN, serum-transfer arthritis, the mice showed blocked autoreactive B- and T-cell formation and decreased bone impairment, as in RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis.168,188 In addition, miR-223 has been found in high-level RA synovium patients with CIA rather than OA, and overexpression of miR-223 results in reduced osteoclastogenesis.189,190,191 In human PBMCs of CIA, miR-146a is up-regulated, but c-Jun, NFATc1, PU.1, and especially TRAP expression is down-regulated in a dose-dependent manner, indicating the osteoclastic inhibition ability of miR-146a.192,193,194

M-CSFR

M-CSF receptor (M-CSFR)/CSF-1R/c-Fms, which exists in osteoclast precursors and is bound by M-CSF, is another essential secreted cytokine in osteoclast differentiation. M-CSFR is also released by osteoblasts, and it connects to receptors to initiate physiological functions through oligomerization and transphosphorylation.195,196 PU.1, which stimulates osteoclast-specific markers and RANK expression, can positively bind to the promoter of the M-CSFR gene for activation.197 M-CSF then participates in the latter differentiation process by stimulating the Akt, c-Fos, and ERK pathways.198 CSF-1R has been shown to be expressed extensively in human RA, and injection of its monoclonal antibody provided effective protection against RA and inhibited osteoclast formation.199 Moreover, a positive feedback loop of M-SCF/PU.1/miR-233/NFI-A/M-CSFR exists. M-CSF activates PU.1, which then up-regulates miR-233 and gives rise to the reduction of M-CSFR through negative regulation of nuclear factor I-A (NFI-A).168

During osteoclastogenesis, the expression level of miRNAs can be regulated by both RANKL and M-CSF induction. Of these two mechanisms, miR-214 plays a significant role in osteogenesis by targeting ATF, which is also a crucial regulator of osteoclast differentiation.200 However, how miR-214 controls homeostasis and how to target it specifically remain elusive.

miRNAs between Osteoblast and Osteoclast Lineages

Beyond osteogenesis and osteoclastogenesis in bone remodeling, numerous signaling communications that affect each other also exist. Osteoclast-specific Dicer gene deficiency analysis has shown that activity of both osteoclasts and osteoblasts is inhibited, while bone mass is increased, indicating simultaneous and unequal epigenetic regulatory mechanisms.168

TNF-α/cachexin

TNF-α/cachexin is an inflammatory cytokine in bone homeostasis. It can stimulate osteoclastogenesis, but it also dually inhibits or induces osteoblastogenesis. TNF-α binds to TNFR1/2 and then acts via NF-κB, MAPK, and the AP-1 pathway, in association with the pathogeneses of RA and ankylosing spondylitis (AS).201

For osteoblast differentiation, TNF-α plays an inhibitory role via Osx, ALP, and Runx2 by up-regulating Smurf1.202 Its dual function depends on the concentration of TNF-α, with low concentrations leading to osteogenic differentiation of MSCs,203 but a low-dose stimulus may inhibit the development of bone in young mice.204 Additionally, JNK signaling was found to be strongly expressed in the MAPK pathway, both increasing ALP activity and decreasing Runx2 and Smads.205,206 For osteoclast differentiation, TNF-α indirectly stimulates osteoclastic bone resorption;207 additionally, TNF-α can synergize with RANKL and M-SCF or directly target osteoclast precursors for the further activation of NF-κB and AP-1 signaling to induce osteoclastogenesis.201,208 However, pre-osteoclast and osteoclast precursors can induce apoptosis by the interaction of TNF-induced Fas with IFN, thus inhibiting osteoclastogenesis.208,209

Knockdown of miR-155 directly increases target SOCS1 expression, which is a negative regulator of TNF-α and JNK signaling, as well as limiting NF-κB signaling. Down-regulation of JNK led to the inhibition of osteogenesis in MC3T3-E1 cells, as well as the apoptosis of TNF-α-related cells.210 At the same time, by targeting SOCS1 and MITF, miR-155 can suppress the function of IFN-β in osteoclast differentiation, providing new insight into the dimorphic role of one miRNA balanced in both osteogenesis and osteoclastogenesis.211 In addition to miR-155, miR-21, miR-29b, miR-146, and miR-210 have all been found to be involved in the osteoclast differentiation of TNF-α-regulated RAW264.7 cells.212 miR-21 has also been found to be down-regulated in estrogen-deficiency-induced osteoporosis samples, and it has been verified to be suppressed by TNF-α; furthermore, miR-21 can promote hMSC osteogenesis by targeting Spry1.213 The knockdown of miR-23a significantly enhanced the apoptosis of TNF-α-induced osteoblast precursors by reversing the inhibition of target Fas.214

Notch

Notch is a receptor that exists in highly conserved cells and is always triggered by direct contact among neighbor cells that expose the Notch ligands (Delta-like1, 3, 4, Jagged1, Jagged2). After silencing, the NICD/CSL complex forms and then activates Hes/Hey/Herp. In addition to numerous functions in nerve/cardiovascular/endocrine development, Notch has also emerged as an important regulator of multiple stages of skeletogenesis.215 It appears to inhibit the terminal osteoblastic differentiation of mesenchymal precursors and bone formation by diminishing Runx2 activity via Hes/Hey.216,217 However, Notch is also required for proper regulation of osteoclast differentiation. The Delta1 ligand acts as an inhibitor of CSF-1R, and physiologic Notch signaling, enabled by presenilin-1/2, balances osteoblast-dependent osteoclastogenesis via the regulation of OPG.217,218 The Notch signaling-related miRNAs focus on the miR-34 family. miR-34a/b/c has been previously shown to inhibit osteoblast differentiation by targeting multiple components of the Notch signaling pathway, such as Notch1/2, Jagged1, and SATB2.52,53 However, how miR-34 regulates osteoclastogenesis is non-cell-autonomous, involving an osteoblast–osteoclast coupling mechanism, whereby miR-34c transgenic osteoblasts increase the production and proportion of RANKL/OPG and induce osteoclast differentiation.219 Simultaneously, evidence has revealed that miR-34a is a novel and critical blocker of transforming growth factor-B-induced factor 2 (Tgif2), which results in suppressed bone resorption.220 Therefore, different members of the same miRNA family may play distinct roles in osteoporosis and other bone-related diseases.

miRNAs in Biomaterials and Therapeutics

Based on the increasing body of research on miRNAs, the concepts regarding biomaterials for the repair of bone defects and the restoration of bone functions have expanded. Previous research focused on the different materials and constructions that induce different miRNAs in the bone formation process, such as inorganic silicate-based PerioGlas, inorganic bovine bone, and organic collagen materials that act to alter osteoblast activity due to the exposure of different cell-binding domains and miRNA translations.221,222

Conversely, the use of modified materials to deliver a specific miRNA into a body makes precise regulation achievable. Extensively applied in bone formation, a polymeric scaffold has good biocompatibility and controlled biodegradability. Recently, poly(glycerol sebacate) and porous β-TCP scaffolds seeded with anti-miR-31-modified BMSCs showed significant capacity to repair critical-sized defects (8 mm diameter in the cranium and 10 mm diameter in the canine medial orbital wall).54,223 In addition, another microgrooved poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) seeded with osteogenic miRNAs triggered the expression of multiple osteogenic markers.224 To increase the efficiency of miRNA transfection, researchers have used a microporous titanium oxide surface functionalized with miR-29b/anti-miR-138 or 2000-miR-148b/anti-miR-138 lipoplex reverse transfection to enhance osteogenic activity.225,226

In addition to transfection, direct delivery is also convenient. The miR-29b mimic combines with a synthetic cell-penetrating peptide, forming a nanoparticle complex and promoting osteogenesis by directly down-regulating osteogenic inhibitors.227 Another study used silver nanoparticles with localized surface plasmon fields with increased sensory ability, and the miR-148b mimic is linked to such nanoparticles through photocleavable linkers, resulting in PC-miR-148-SNP conjugation in the modulation of osteogenesis in hASCs.228 The miR-148 family is utilized again in a novel delivery system, but eight repeating sequences of aspartate (D-Asp8)-liposome-antagomir-148a have been created to target osteoclasts specifically to attenuate bone resorption. Therefore, it may be regarded as one promising approach for the treatment of osteoclast-dysfunction-induced skeletal diseases.229

Conclusions and Future Prospects

In general, bone remodeling is controlled by the balance between bone formation and bone resorption. However, remodeling is a complicated process involving numerous signals and pathway modifications. This review summarized the current knowledge regarding miRNAs and their biological functions related to some specific regulatory molecules in regulating multiple stages of bone remodeling. Numerous in vitro and in vivo studies have been undertaken to demonstrate the importance and complexity of post-transcriptional regulation by miRNAs, and these studies have provided the foundation for potential therapy. However, further efforts should be undertaken to investigate the transduction and communication pathways between miRNAs and intracellular signal, as well as the communication of different miRNAs in different pathways of both osteogenesis and osteoclastogenesis, the direct and indirect targets of different miRNAs, and even some of the less desirable effects, such as stress loading, oxygen pressure, and microenvironment changes, on miRNA functions in bone remodeling. Therefore, to realize the ultimate goal of maintaining balance in bone remodeling, increased focus should be placed on treatments that cause specific miRNAs to function efficiently in specific locations and during certain stages of bone diseases.

Acknowledgments

We apologize to those researchers whose work was not included in this review due to space limitations. This work was supported by grants from the Science and Technology Fund of Sichuan Province (Grant No. 2011SZ0096) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 31470904).

References

- 1Dimitriou R, Jones E, McGonagle D et al. Bone regeneration: current concepts and future directions. BMC Med 2011; 31(9): 66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2Siddiqui NA, Owen JM. Clinical advances in bone regeneration. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther 2013; 8(3): 192–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3Tezuka K, Yasuda M, Watanabe N et al. Stimulation of osteoblastic cell differentiation by Notch. J Bone Miner Res 2002; 17(2): 231–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4Chen D, Zhao M, Mundy GR. Bone morphogenetic proteins. Growth Factors 2004; 22(4): 233–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5Hu H, Hilton MJ, Tu X et al. Sequential roles of Hedgehog and Wnt signaling in osteoblast development. Development 2005; 132(1): 49–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6Estrada K, Styrkarsdottir U, Evangelou E et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies 56 bone mineral density loci and reveals 14 loci associated with risk of fracture. Nat Genet 2012; 44(5): 491–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7Zaidi SK, Young DW, Montecino M et al. Bookmarking the genome: maintenance of epigenetic information. J Biol Chem 2011; 286(21): 18355–18361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8Ghildiyal M, Zamore PD. Small silencing RNAs: an expanding universe. Nat Rev Genet 2009; 10(2): 94–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9Iorio MV, Piovan C, Croce CM. Interplay between microRNAs and the epigenetic machinery: an intricate network. Biochim Biophys Acta 2010; 1799(10/11/12): 694–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10Sims NA, Gooi JH. Bone remodeling: multiple cellular interactions required for coupling of bone formation and resorption. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2008; 19(5): 444–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11Schaffler MB, Cheung WY, Majeska R et al. Osteocytes: master orchestrators of bone. Calcif Tissue Int 2014; 94(1): 5–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12Kirk MD, Kahn AJ. Extracellular matrix synthesized by clonal osteogenic cells is osteoinductive in vivo and in vitro: role of transforming growth factor-beta 1 in osteoblast cell-matrix interaction. J Bone Miner Res 1995; 10(8): 1203–1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13Lien CY, Lee OK, Su Y. Cbfb enhances the osteogenic differentiation of both human and mouse mesenchymal stem cells induced by Cbfa-1 via reducing its ubiquitination-mediated degradation. Stem Cells 2007; 25(6): 1462–1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14Asagiri M, Takayanagi H. The molecular understanding of osteoclast differentiation. Bone 2007; 40(2): 251–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15Sims NA, Martin TJ. Coupling the activities of bone formation and resorption: a multitude of signals within the basic multicellular unit. Bonekey Rep 2014; 3: 481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16Hobert O. Gene regulation by transcription factors and microRNAs. Science 2008; 319(5871): 1785–1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 2004; 116(2): 281–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18Borchert GM, Lanier W, Davidson BL. RNA polymerase III transcribes human microRNAs. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2006; 13(12): 1097–1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19Kapinas K, Kessler CB, Delany AM. miR-29 suppression of osteonectin in osteoblasts: regulation during differentiation and by canonical Wnt signaling. J Cell Biochem 2009; 108(1): 216–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20Guo H, Ingolia NT, Weissman JS et al. Mammalian microRNAs predominantly act to decrease target mRNA levels. Nature 2010; 466(7308): 835–840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21Ambros V, Chen X. The regulation of genes and genomes by small RNAs. Development 2007; 134(9): 1635–1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22Cullen BR. Transcription and processing of human microRNA precursors. Mol Cell 2004; 16(6): 861–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23Bentwich I, Avniel A, Karov Y et al. Identification of hundreds of conserved and nonconserved human microRNAs. Nat Genet 2005; 37(7): 766–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24Langenberger D, Çakir MV, Hoffmann S et al. Dicer-processed small RNAs: rules and exceptions. J Exp Zool B Mol Dev Evol 2013; 320(1): 35–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25Dalmay T. Mechanism of miRNA-mediated repression of mRNA translation. Essays Biochem 2013; 54(1): 29–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26Titorencu I, Pruna V, Jinga VV et al. Osteoblast ontogeny and implications for bone pathology: an overview. Cell Tissue Res 2014; 355(1): 23–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27Dalle Carbonare L, Innamorati G, Valenti MT. Transcription factor Runx2 and its application to bone tissue engineering. Stem Cell Rev 2012; 8(3): 891–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28Ducy P, Zhang R, Geoffroy V et al. Osf2/Cbfa1: a transcriptional activator of osteoblast differentiation. Cell 1997; 89(5): 747–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29Cohen MM Jr. Perspectives on RUNX genes: an update. Am J Med Genet A 2009; 149A(12): 2629–2646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30He N, Xiao Z, Yin T et al. Inducible expression of Runx2 results in multiorgan abnormalities in mice. J Cell Biochem 2011; 112(2): 653–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31Ylönen R, Kyrönlahti T, Sund M et al. Type XIII collagen strongly affects bone formation in transgenic mice. J Bone Miner Res 2005; 20(8): 1381–1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32Huszar JM, Payne CJ. MIR146A inhibits JMJD3 expression and osteogenic differentiation in human mesenchymal stem cells. FEBS Lett 2014; 588(9): 1850–1856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33Zhang Y, Xie RL, Croce CM et al. A program of microRNAs controls osteogenic lineage progression by targeting transcription factor Runx2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011; 108(24): 9863–9868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34Zhang Y, Xie RL, Gordon J et al. Control of mesenchymal lineage progression by microRNAs targeting skeletal gene regulators Trps1 and Runx2. J Biol Chem 2012; 287(26): 21926–21935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35Wu T, Zhou H, Hong Y et al. miR-30 family members negatively regulate osteoblast differentiation. J Biol Chem 2012; 287(10): 7503–7511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36Zaragosi LE, Wdziekonski B, Brigand KL et al. Small RNA sequencing reveals miR-642a-3p as a novel adipocyte-specific microRNA and miR-30 as a key regulator of human adipogenesis. Genome Biol 2011; 12(7): R64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37Huang J, Zhao L, Xing L et al. MicroRNA-204 regulates Runx2 protein expression and mesenchymal progenitor cell differentiation. Stem Cells 2010; 28(2): 357–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38Cui RR, Li SJ, Liu LJ et al. MicroRNA-204 regulates vascular smooth muscle cell calcification in vitro and in vivo. Cardiovasc Res 2012; 96(2): 320–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39Mizuno Y, Yagi K, Tokuzawa Y et al. miR-125b inhibits osteoblastic differentiation by down-regulation of cell proliferation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2008; 368(2): 267–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40Huang K, Fu J, Zhou W et al. MicroRNA-125b regulates osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells by targeting Cbfβ in vitro. Biochimie 2014; 102: 47–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41Chen S, Yang L, Jie Q et al. MicroRNA-125b suppresses the proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Mol Med Rep 2014; 9(5): 1820–1826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42Pinto MT, Nicolete LD, Rodrigues ES et al. Overexpression of hsa-miR-125b during osteoblastic differentiation does not influence levels of Runx2, osteopontin, and ALPL gene expression. Braz J Med Biol Res 2013; 46(8): 676–680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43Wei FL, Wang JH, Ding G et al. Mechanical force-induced specific MicroRNA expression in human periodontal ligament stem cells. Cells Tissues Organs 2014; 199(5/6): 353–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44Chen Y, Mohammed A, Oubaidin M et al. Cyclic stretch and compression forces alter microRNA-29 expression of human periodontal ligament cells. Gene 2015; 566(1): 13–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45Zuo B, Zhu J, Li J et al. microRNA-103a functions as a mechanosensitive microRNA to inhibit bone formation through targeting Runx2. J Bone Miner Res 2015; 30(2): 330–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46Dobreva G, Chahrour M, Dautzenberg M et al. SATB2 is a multifunctional determinant of craniofacial patterning and osteoblast differentiation. Cell 2006; 125(5): 971–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47Zhang J, Tu Q, Grosschedl R et al. Roles of SATB2 in osteogenic differentiation and bone regeneration. Tissue Eng Part A 2011; 17(13/14): 1767–1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48Tang W, Li Y, Osimiri L et al. Osteoblast-specific transcription factor Osterix (Osx) is an upstream regulator of Satb2 during bone formation. J Biol Chem 2011; 286(38): 32995–33002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49Conner JR, Hornick JL. SATB2 is a novel marker of osteoblastic differentiation in bone and soft tissue tumours. Histopathology 2013; 63(1): 36–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50Hassan MQ, Gordon JA, Beloti MM et al. A network connecting Runx2, SATB2, and the miR-23a∼27a∼24-2 cluster regulates the osteoblast differentiation program. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010; 107(46): 19879–19884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51Park J, Wada S, Ushida T et al. The microRNA-23a has limited roles in bone formation and homeostasis in vivo. Physiol Res 2015. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52Wei J, Shi Y, Zheng L et al. miR-34s inhibit osteoblast proliferation and differentiation in the mouse by targeting SATB2. J Cell Biol 2012; 197(4): 509–521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53Bae Y, Yang T, Zeng HC et al. miRNA-34c regulates Notch signaling during bone development. Hum Mol Genet 2012; 21(13): 2991–3000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54Deng Y, Bi X, Zhou H et al. Repair of critical-sized bone defects with anti-miR-31-expressing bone marrow stromal stem cells and poly(glycerol sebacate) scaffolds. Eur Cell Mater 2014; 27: 13–24; discussion 24–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55Xie Q, Wang Z, Bi X et al. Effects of miR-31 on the osteogenesis of human mesenchymal stem cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2014; 446(1): 98–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56Deng Y, Wu S, Zhou H et al. Effects of a miR-31, Runx2, and Satb2 regulatory loop on the osteogenic differentiation of bone mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells Dev 2013; 22(16): 2278–2286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57Chen S, Feng J, Zhang H et al. Key role for the transcriptional factor, Osterix, in spine development. Spine J 2014; 14(4): 683–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58Nakashima K, Zhou X, Kunkel G et al. The novel zinc finger-containing transcription factor osterix is required for osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. Cell 2002; 108(1): 17–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59Nishio Y, Dong Y, Paris M et al. Runx2-mediated regulation of the zinc finger Osterix/Sp7 gene. Gene 2006; 372: 62–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60Celil AB, Campbell PG. BMP-2 and insulin-like growth factor-I mediate Osterix (Osx) expression in human mesenchymal stem cells via the MAPK and protein kinase D signaling pathways. J Biol Chem 2005; 280(36): 31353–31359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61Matsubara T, Kida K, Yamaguchi A et al. BMP2 regulates Osterix through Msx2 and Runx2 during osteoblast differentiation. J Biol Chem 2008; 283(43): 29119–29125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62Baglìo SR, Devescovi V, Granchi D et al. MicroRNA expression profiling of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells during osteogenic differentiation reveals Osterix regulation by miR-31. Gene 2013; 527(1): 321–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63Yang L, Cheng P, Chen C et al. miR-93/Sp7 function loop mediates osteoblast mineralization. J Bone Miner Res 2012; 27(7): 1598–1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64Li E, Zhang J, Yuan T et al. MiR-143 suppresses osteogenic differentiation by targeting Osterix. Mol Cell Biochem 2014; 390(1/2): 69–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65Jia J, Tian Q, Ling S et al. miR-145 suppresses osteogenic differentiation by targeting Sp7. FEBS Lett 2013; 587(18): 3027–3031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66Liu H, Lin H, Zhang L et al. miR-145 and miR-143 regulate odontoblast differentiation through targeting Klf4 and Osx genes in a feedback loop. J Biol Chem 2013; 288(13): 9261–9271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67Zhang JF, Fu WM, He ML et al. MiR-637 maintains the balance between adipocytes and osteoblasts by directly targeting Osterix. Mol Biol Cell 2011; 22(21): 3955–3961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68Shi K, Lu J, Zhao Y et al. MicroRNA-214 suppresses osteogenic differentiation of C2C12 myoblast cells by targeting Osterix. Bone 2013; 55(2): 487–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69Gámez B, Rodríguez-Carballo E, Bartrons R et al. MicroRNA-322 (miR-322) and its target protein Tob2 modulate Osterix (Osx) mRNA stability. J Biol Chem 2013; 288(20): 14264–14275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70Chen Q, Liu W, Sinha KM et al. Identification and characterization of microRNAs controlled by the osteoblast-specific transcription factor Osterix. PLoS One 2013; 8(3): e58104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71Chen G, Deng C, Li YP. TGF-β and BMP signaling in osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. Int J Biol Sci 2012; 8(2): 272–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72Song B, Estrada KD, Lyons KM. Smad signaling in skeletal development and regeneration. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2009; 20(5/6): 379–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73Afzal F, Pratap J, Ito K et al. Smad function and intranuclear targeting share a Runx2 motif required for osteogenic lineage induction and BMP2 responsive transcription. J Cell Physiol 2005; 204(1): 63–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74Kureel J, Dixit M, Tyagi AM et al. miR-542-3p suppresses osteoblast cell proliferation and differentiation, targets BMP-7 signaling and inhibits bone formation. Cell Death Dis 2014; 5: e1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75Luzi E, Marini F, Sala SC et al. Osteogenic differentiation of human adipose tissue-derived stem cells is modulated by the miR-26a targeting of the SMAD1 transcription factor. J Bone Miner Res 2008; 23(2): 287–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76Xu S, Cecilia Santini G, De Veirman K et al. Upregulation of miR-135b is involved in the impaired osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells derived from multiple myeloma patients. PLoS One 2013; 8(11): e79752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77Li Z, Hassan MQ, Volinia S et al. A microRNA signature for a BMP2-induced osteoblast lineage commitment program. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008; 105(37): 13906–13911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78Schaap-Oziemlak AM, Raymakers RA, Bergevoet SM et al. MicroRNA hsa-miR-135b regulates mineralization in osteogenic differentiation of human unrestricted somatic stem cells. Stem Cells Dev 2010; 19(6): 877–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79Li H, Li T, Wang S et al. miR-17-5p and miR-106a are involved in the balance between osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation of adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cell Res 2013; 10(3): 313–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80Zeng Y, Qu X, Li H et al. MicroRNA-100 regulates osteogenic differentiation of human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells by targeting BMPR2. FEBS Lett 2012; 586(16): 2375–2381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81Hwang S, Park SK, Lee HY et al. miR-140-5p suppresses BMP2-mediated osteogenesis in undifferentiated human mesenchymal stem cells. FEBS Lett 2014; 588(17): 2957–2963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82Jia J, Feng X, Xu W et al. MiR-17-5p modulates osteoblastic differentiation and cell proliferation by targeting SMAD7 in non-traumatic osteonecrosis. Exp Mol Med 2014; 46: e107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83Liu T, Fu NN, Song HL et al. Suppression of MicroRNA-203 improves survival of rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells through enhancing PI3K-induced cellular activation. IUBMB Life 2014; doi:10.1002/iub.1259. [Epub ahead of print.] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 84Day TF, Guo X, Garrett-Beal L et al. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in mesenchymal progenitors controls osteoblast and chondrocyte differentiation during vertebrate skeletogenesis. Dev Cell 2005; 8(5): 739–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85Rossini M, Gatti D, Adami S. Involvement of WNT/β-catenin signaling in the treatment of osteoporosis. Calcif Tissue Int 2013; 93(2): 121–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86Liu G, Vijayakumar S, Grumolato L et al. Canonical Wnts function as potent regulators of osteogenesis by human mesenchymal stem cells. J Cell Biol 2009; 185(1): 67–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87Liu W, Liu Y, Guo T et al. TCF3, a novel positive regulator of osteogenesis, plays a crucial role in miR-17 modulating the diverse effect of canonical Wnt signaling in different microenvironments. Cell Death Dis 2013; 4: e539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88Roberto VP, Tiago DM, Silva IA et al. MiR-29a is an enhancer of mineral deposition in bone-derived systems. Arch Biochem Biophys 2014; 564: 173–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89Gaur T, Lengner CJ, Hovhannisyan H et al. Canonical WNT signaling promotes osteogenesis by directly stimulating Runx2 gene expression. J Biol Chem 2005; 280(39): 33132–33140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90Wang J, Guan X, Guo F et al. miR-30e reciprocally regulates the differentiation of adipocytes and osteoblasts by directly targeting low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 6. Cell Death Dis 2013; 4: e845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91Qiu W, Kassem M. miR-141-3p inhibits human stromal (mesenchymal) stem cell proliferation and differentiation. Biochim Biophys Acta 2014; 1843(9): 2114–2121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92Yang X, Matsuda K, Bialek P et al. ATF4 is a substrate of RSK2 and an essential regulator of osteoblast biology; implication for Coffin-Lowry Syndrome. Cell 2004; 117(3): 387–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93Makowski AJ, Uppuganti S, Wadeer SA et al. The loss of activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4) reduces bone toughness and fracture toughness. Bone 2014; 62: 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94Xiao G, Jiang D, Ge C et al. Cooperative interactions between activating transcription factor 4 and Runx2/Cbfa1 stimulate osteoblast-specific osteocalcin gene expression. J Biol Chem 2005; 280(35): 30689–30696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95Liu TM, Lee EH. Transcriptional regulatory cascades in Runx2-dependent bone development. Tissue Eng Part B Rev 2013; 19(3): 254–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96St-Arnaud R, Mandic V. FIAT control of osteoblast activity. J Cell Biochem 2010; 109(3): 453–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97St-Arnaud R, Hekmatnejad B. Combinatorial control of ATF4-dependent gene transcription in osteoblasts. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2011; 1237: 11–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98Hekmatnejad B, Gauthier C, St-Arnaud R. Control of Fiat (factor inhibiting ATF4-mediated transcription) expression by Sp family transcription factors in osteoblasts. J Cell Biochem 2013; 114(8): 1863–1870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99Matsuguchi T, Chiba N, Bandow K et al. JNK activity is essential for Atf4 expression and late-stage osteoblast differentiation. J Bone Miner Res 2009; 24(3): 398–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100Karsenty G. Transcriptional control of skeletogenesis. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet 2008; 9: 183–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101Wang X, Guo B, Li Q et al. miR-214 targets ATF4 to inhibit bone formation. Nat Med 2013; 19(1): 93–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102Byun MR, Kim AR, Hwang JH et al. FGF2 stimulates osteogenic differentiation through ERK induced TAZ expression. Bone 2014; 58: 72–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103Byun MR, Hwang JH, Kim AR et al. Canonical Wnt signalling activates TAZ through PP1A during osteogenic differentiation. Cell Death Differ 2014; 21(6): 854–863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104Byun MR, Kim AR, Hwang JH et al. Phorbaketal A stimulates osteoblast differentiation through TAZ mediated Runx2 activation. FEBS Lett 2012; 586(8): 1086–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105Jang EJ, Jeong H, Kang JO et al. TM-25659 enhances osteogenic differentiation and suppresses adipogenic differentiation by modulating the transcriptional co-activator TAZ. Br J Pharmacol 2012; 165(5): 1584–1594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106Hong JH, Hwang ES, McManus MT et al. TAZ, a transcriptional modulator of mesenchymal stem cell differentiation. Science 2005; 309(5737): 1074–1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107Hong JH, Yaffe MB. TAZ: a beta-catenin-like molecule that regulates mesenchymal stem cell differentiation. Cell Cycle 2006; 5(2): 176–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108Cho HH, Shin KK, Kim YJ et al. NF-κB activation stimulates osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells derived from human adipose tissue by increasing TAZ expression. J Cell Physiol 2010; 223(1): 168–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109Chaulk SG, Lattanzi VJ, Hiemer SE et al. The Hippo pathway effectors TAZ/YAP regulate dicer expression and microRNA biogenesis through Let-7. J Biol Chem 2014; 289(4): 1886–1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110Hao J, Zhang Y, Jing D et al. Role of Hippo signaling in cancer stem cells. J Cell Physiol 2014; 229(3): 266–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111Dupont S, Morsut L, Aragona M et al. Role of YAP/TAZ in mechanotransduction. Nature 2011; 474(7350): 179–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112Hao J, Zhang Y, Wang Y et al. Role of extracellular matrix and YAP/TAZ in cell fate determination. Cell Signal 2014; 26(2): 186–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113Eskildsen T, Taipaleenmäki H, Stenvang J et al. MicroRNA-138 regulates osteogenic differentiation of human stromal (mesenchymal) stem cells in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011; 108(15): 6139–6144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114Qu B, Xia X, Wu HH et al. PDGF-regulated miRNA-138 inhibits the osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2014; 448(3): 241–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115Guan X, Gao Y, Zhou J et al. miR-223 regulates adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells through a C/EBPs/miR-223/FGFR2 regulatory feedback loop. Stem Cells 2015; 33(5): 1589–1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116Liu H, Sun Q, Wan C et al. MicroRNA-338-3p regulates osteogenic differentiation of mouse bone marrow stromal stem cells by targeting Runx2 and Fgfr2. J Cell Physiol 2014; 229(10): 1494–1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117Lecanda F, Warlow PM, Sheikh S et al. Connexin43 deficiency causes delayed ossification, craniofacial abnormalities, and osteoblast dysfunction. J Cell Biol 2000; 151(4): 931–944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118Kim HK, Lee YS, Sivaprasad U et al. Muscle-specific microRNA miR-206 promotes muscle differentiation. J Cell Biol 2006; 174(5): 677–687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119Inose H, Ochi H, Kimura A et al. A microRNA regulatory mechanism of osteoblast differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009; 106(49): 20794–20799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120Itoh T, Nozawa Y, Akao Y. MicroRNA-141 and -200a are involved in bone morphogenetic protein-2-induced mouse pre-osteoblast differentiation by targeting distal-less homeobox 5. J Biol Chem 2009; 284(29): 19272–19279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121Sangani R, Periyasamy-Thandavan S, Kolhe R et al. MicroRNAs-141 and 200a regulate the SVCT2 transporter in bone marrow stromal cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2015; 410: 19–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122Okamoto H, Matsumi Y, Hoshikawa Y et al. Involvement of microRNAs in regulation of osteoblastic differentiation in mouse induced pluripotent stem cells. PLoS One 2012; 7(8): e43800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123Qadir AS, Um S, Lee H et al. miR-124 negatively regulates osteogenic differentiation and in vivo bone formation of mesenchymal stem cells. J Cell Biochem 2015; 116(5): 730–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124Tyagi S, Gupta P, Saini AS et al. The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor: a family of nuclear receptors role in various diseases. J Adv Pharm Technol Res 2011; 2(4): 236–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125James AW. Review of signaling pathways governing MSC osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation. Scientifica: Cairo 2013; 2013: 684736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126Sethi JK, Vidal-Puig AJ. Thematic review series: adipocyte biology. Adipose tissue function and plasticity orchestrate nutritional adaptation. J Lipid Res 2007; 48(6): 1253–1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127Akune T, Ohba S, Kamekura S et al. PPARgamma insufficiency enhances osteogenesis through osteoblast formation from bone marrow progenitors. J Clin Invest 2004; 113(6): 846–855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128Jeon MJ, Kim JA, Kwon SH et al. Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ inhibits the Runx2-mediated transcription of osteocalcin in osteoblasts. J Biol Chem 2003; 278(26): 23270–23277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129Liu J, Wang H, Zuo Y et al. Functional interaction between peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ and β-catenin. Mol Cell Biol 2006; 26(15): 5827–5837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130Zhao QH, Wang SG, Liu SX et al. PPARγ forms a bridge between DNA methylation and histone acetylation at the C/EBPα gene promoter to regulate the balance between osteogenesis and adipogenesis of bone marrow stromal cells. FEBS J 2013; 280(22): 5801–5814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131Kang Q, Song WX, Luo Q et al. A comprehensive analysis of the dual roles of BMPs in regulating adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal progenitor cells. Stem Cells Dev 2009; 18(4): 545–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132Sun J, Wang Y, Li Y et al. Downregulation of PPARγ by miR-548d-5p suppresses the adipogenic differentiation of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells and enhances their osteogenic potential. J Transl Med 2014; 12: 168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133He J, Zhang JF, Yi C et al. miRNA-mediated functional changes through co-regulating function related genes. PLoS One 2010; 5(10): e13558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134Zhang JF, Fu WM, He ML et al. MiRNA-20a promotes osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells by co-regulating BMP signaling. RNA Biol 2011; 8(5): 829–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135Niehrs C. Function and biological roles of the Dickkopf family of Wnt modulators. Oncogene 2006; 25(57): 7469–7481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136Katoh M, Katoh M. WNT signaling pathway and stem cell signaling network. Clin Cancer Res 2007; 13(14): 4042–4045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137Zhang WB, Zhong WJ, Wang L. A signal-amplification circuit between miR-218 and Wnt/β-catenin signal promotes human adipose tissue-derived stem cells osteogenic differentiation. Bone 2014; 58: 59–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138Hassan MQ, Maeda Y, Taipaleenmaki H et al. miR-218 directs a Wnt signaling circuit to promote differentiation of osteoblasts and osteomimicry of metastatic cancer cells. J Biol Chem 2012; 287(50): 42084–42092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139Zhang J, Tu Q, Bonewald LF et al. Effects of miR-335-5p in modulating osteogenic differentiation by specifically downregulating Wnt antagonist DKK1. J Bone Miner Res 2011; 26(8): 1953–1963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140van Rooij E, Sutherland LB, Thatcher JE et al. Dysregulation of microRNAs after myocardial infarction reveals a role of miR-29 in cardiac fibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008; 105(35): 13027–13032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141Li Z, Hassan MQ, Jafferji M et al. Biological functions of miR-29b contribute to positive regulation of osteoblast differentiation. J Biol Chem 2009; 284(23): 15676–15684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142Egea V, Zahler S, Rieth N et al. Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 (TIMP-1) regulates mesenchymal stem cells through let-7f microRNA and Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012; 109(6): E309–E316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143Wang T, Xu Z. miR-27 promotes osteoblast differentiation by modulating Wnt signaling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2010; 402(2): 186–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144Guo D, Li Q, Lv Q et al. MiR-27a targets sFRP1 in hFOB cells to regulate proliferation, apoptosis and differentiation. PLoS One 2014; 9(3): e91354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145Jensen ED, Nair AK, Westendorf JJ. Histone deacetylase co-repressor complex control of Runx2 and bone formation. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr 2007; 17(3): 187–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]