Abstract

Systemic infrastructure is key to public health achievements. Individual public health program infrastructure feeds into this larger system. Although program infrastructure is rarely defined, it needs to be operationalized for effective implementation and evaluation. The Ecological Model of Infrastructure (EMI) is one approach to defining program infrastructure. The EMI consists of 5 core (Leadership, Partnerships, State Plans, Engaged Data, and Managed Resources) and 2 supporting (Strategic Understanding and Tactical Action) elements that are enveloped in a program’s context. We conducted a literature search across public health programs to determine support for the EMI. Four of the core elements were consistently addressed, and the other EMI elements were intermittently addressed. The EMI provides an initial and partial model for understanding program infrastructure, but additional work is needed to identify evidence-based indicators of infrastructure elements that can be used to measure success and link infrastructure to public health outcomes, capacity, and sustainability.

Keywords: infrastructure, intervention, program evaluation, program sustainability, public health

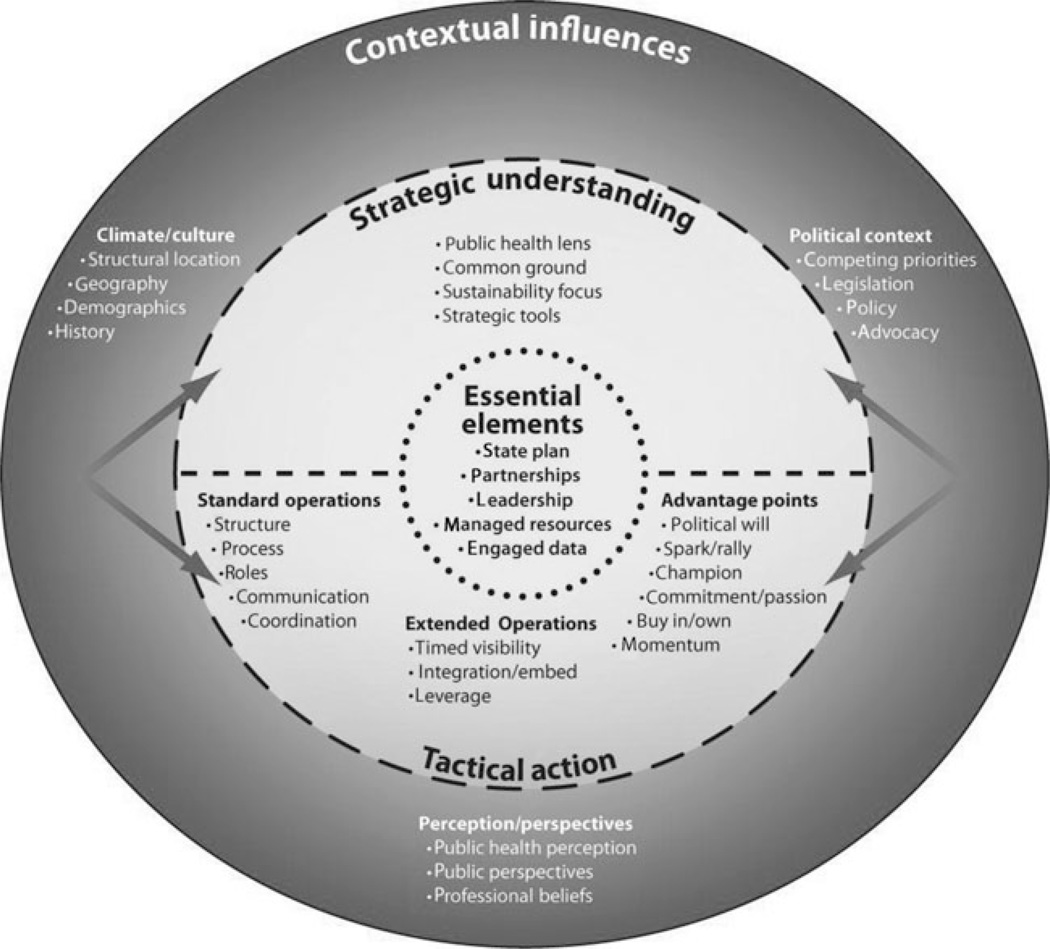

Infrastructure is widely promoted as the key to public health success, but it is a concept that is broadly defined and rarely operationalized in the intervention, public health, and evaluation literatures. It is also often missing on program logic models purporting to link program inputs and outcomes. If infrastructure is truly fundamental to public health program and research goals, then it needs to be reconceptualized and operationally defined so that it can be implemented and evaluated in a practical and actionable manner. In this article, we provide a way to think about that process, using the Ecological Model of Infrastructure (EMI) (Figure 1). The EMI, based on work done within state public oral health programs,1–3 is one way to depict the interactions of multiple elements and layers of program infrastructure. We make a distinction between descriptions of the larger public health system infrastructure and those at the level of program infrastructure. Our objective was to explore the EMI’s applicability to a broader public health program context and discuss the model’s potential and challenges to its utility. We find that the essential elements of the EMI are applicable across public health contexts and that sustainability and outcomes may also be important components of a model of public health program infrastructure.

FIGURE 1.

Ecological Model of Infrastructure: One View of Public Health Program Infrastructure

Is Infrastructure the Sine Qua Non?

For more than 2 decades, public health leaders and organizations have emphasized the importance of infrastructure to public health success. In a 1992 article about improving the public health system, then director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Dr William Roper, and his colleagues4 wrote that to successfully carry out the core public health functions of assessment, policy development, and assurance, the infrastructure of the public health system must be strengthened. Roper and colleagues4 predicted that as America’s health problems become more complex, more comprehensive approaches and thus more [infrastructure] capacity from the public health system will be required. Numerous other authors5–7 and organizations8,9 have provided frameworks and issued reports about the significance of infrastructure or structural capacity and the need to develop models for measuring performance of the public health system. These articles and reports generally refer to the wider public health system infrastructure. For example, Handler and colleagues stated that a “conceptual framework that explicates the relationships among the various components of the public health system is an essential step toward providing a science base for the study of public health system performance.”5(p1235) In 2002, the Institutes of Medicine recommended the US Department of Health and Human Services develop a comprehensive investment plan for a strong national governmental public health infrastructure and that state and local governments should also provide sustainable funding for public health infrastructure.10

Baker and colleagues7 provided a way to assess the public health infrastructure system and detail current deficits and new initiatives. The Healthy People 2020 objectives on infrastructure also declared that “Public health infrastructure is key to all other topic areas in Healthy People 2020.”11 A strong infrastructure provides the capacity to prepare for and respond to both acute (emergency) and chronic (ongoing) threats to the nation’s health. Infrastructure is the foundation for planning, delivering, and evaluating public health.11

What Is Public Health Program Infrastructure?

As public health care practitioners, we believe infrastructure is important to program and service delivery. However, a review of the literature revealed that program infrastructure has not been clearly operationally defined or explicitly evaluated, although there are many models and descriptive frameworks at the larger system level.5–7 A tacit understanding is reflected in the myriad of complex terms and metaphors permeating the literature. Infrastructure is depicted as a foundation, scaffolding, platform, as well as structural or organizational capacity among others. Infrastructure and capacity are used interchangeably12,13 as both synonyms and distinct constructs. For instance, Turnock6 discusses 5 elements of structural capacity—information, organizations, physical, human, and fiscal—that are similar to our later discussion of the EMI elements. An additional complication in the reconceptualization of program infrastructure is the confusion in the literature over the relationship between infrastructure and organizational capacity. Are these terms interchangeable, distinct, or overlapping? Clarifying this relationship is important for understanding how and under what conditions infrastructure can make the maximum contribution to program outcomes.

Literature searches are problematic because words such as “infrastructure,” “capacity,” “sustainability,” and “program achievement” can lead to disparate literatures. The unchallenged assumption that everyone knows what elements constitute infrastructure also hinders progress on operationally defining and using this important construct in programs.

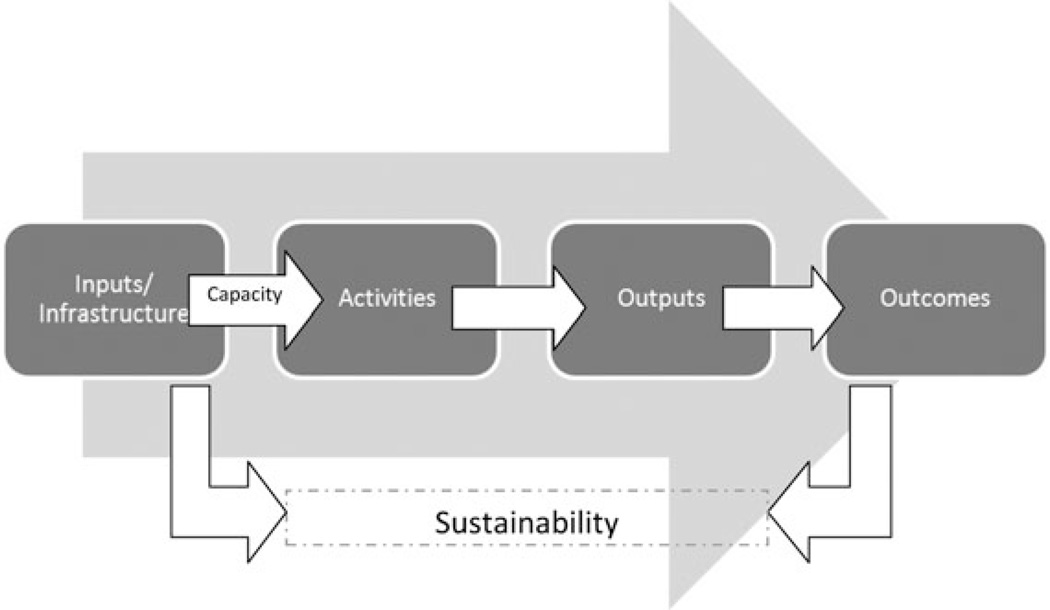

Moreover, in public health program logic models, infrastructure is either left out entirely or assumed to be encompassed by the inputs section or as part of the context of the program. Such logic models imply that the real action of public health programs lies with the activities and outcomes columns. Increasingly, to focus on the link between activities and outcomes, the inputs section may even be eliminated from the logic model, rendering infrastructure invisible. Authors of an oral health case study concluded that building solid infrastructure leads to organizational capacity.1–3,14 Others, including Turnock,6 have concluded that infrastructure has both static (building blocks) and dynamic (capacity or capability) attributes and that both are essential for achieving sustainable outcomes.12,13,15–17 We view program infrastructure as the foundation or platform that supports capacity, implementation, and sustainability of program initiatives. We view capacity as the anticipated energy for action resulting from infrastructure elements. It is as if the infrastructure described in the inputs section of the logic model releases the energy that activates the arrows or connections to the program’s activities and outputs in the logic model. Thus, as depicted in Figure 2, program infrastructure creates capacity, which leads to action, which, in turn, leads to outcomes and sustainability.

FIGURE 2.

Example of Infrastructure Logic Model

Neglect of program infrastructure can be costly. Chapman attributes deemphasized infrastructures in part to the “tendency to rush to tactics.”15(p8) Both Chapman15 and Hannah16 believe that this “productprocess tension,”—the desire to realize immediate results over the need to build capacity—tends to encourage public health program administrators and evaluators to ignore infrastructure development, favoring program elements with demonstrable and direct links to outcomes.15,16 Chapman cautions that overlooking the “organizational platform that creates the capacity to deliver”15(p8) ultimately results in greater funding for output achievements and potentially overstretched staff and partners.18 The strategies required to deliver evidence-based outcomes are available for many disease prevention programs. However, there is no evidence for how to develop public health infrastructure and demonstrate even indirect links to outcomes. Yet, achieving and sustaining outcomes require both an investment in financial resources and adequate infrastructure and capacity.11–13,16

Toward a Preliminary Definition: The EMI Model

In order for a model to be relevant for implementation and evaluation, it should depict the elements of program infrastructure in a concrete, meaningful manner. The EMI is one model that depicts the essential and supporting elements of infrastructure and their interactions.1–3 This model was developed through a case study of 4 state public health oral health programs funded by the CDC. The CDC funding initiative* was aimed explicitly at building infrastructure and strengthening the capacity to provide oral health promotion and disease prevention programs. This initiative was designed on the basis of the 10 Essential Public Health Services19 and intended to be developmental so that learning could occur in real time. The EMI was the first model depiction of what was learned from the 8-year initiative.

The model is “ecological” because of the reciprocal nature of the layers of infrastructure depicted. Infrastructure, as the model shows (Figure 1), is layered like an onion and the layers are permeable and interactive. At its core are a set of Essential Elements (State Plans, Partnerships, Leadership, Managed Resources, Engaged Data). These are the elements that were derived from analytic discussions and based on details that all of the 4 study states indicated were crucial to their program’s existence, as well as to the evolution and sustainability of the programs. These elements are the first step toward concretely defining program infrastructure.

The EMI visualizes the 5 Essential Elements as core to program infrastructure but not sufficient in and of themselves. The Essential Elements of the EMI are informed by Strategic Understanding and Tactical Action within a specific environment of Contextual Influences. It is within these elements that program activities and outcomes are generated to facilitate progress on health achievements and sustainability. Strategic Understanding consists of the ideas, knowledge, and thinking needed to initiate and support program infrastructure. It includes concepts such as finding common ground among partners, planning for sustainability, and using evidence-based guidelines. Tactical Action refers to the “doing” component of Strategic Understanding. Strategic Understanding charts the direction to the operation/ implementation of Tactical Action. Tactical Action includes concepts such as day-to-day operations, roles, commitment, and leveraging advantage points. There is a critical distinction between the expertise needed for operational implementation of a program and the expertise needed for developing a strategic direction for the program.15 A program needs expertise in both Strategic Understanding and Tactical Action to fully develop an effective and sustainable operational platform. The use of open or permeable lines between the levels indicates interactions between and among the levels. The power of the model lies in the depiction of the union of these constructs to support and interact with the Essential Elements as well as the implementation context.

Contextual Influences envelop all of the other constructs in the EMI, and their potential impact on a program is represented by arrows pointing to both Strategic Understanding and Tactical Action. No program functions within a vacuum, and these influences include cultural values, political priorities, and the perceptions of or perspectives on the public health issue being addressed. The specific context is often ignored when considering implementation strategies, scalability, or replicability. Context is a malleable and actionable component of program implementation and infrastructure and can have inhibiting or facilitating effects.14 Mastery of Strategic Understanding, Tactical Action, and the Essential Elements create functioning program infrastructure. Functioning infrastructure allows programs to act successfully in the context they operate.

While the EMI was designed to be considered as a whole, we contend that it is mainly the Essential Elements that depict program infrastructure in a tangible manner, with specific and actionable elements that can be described in logic models. Thus, here we focus on brief descriptions of the Essential Elements while the entire model is fully explained elsewhere.†

Essential Elements include the following:

State Plans

The State Plans refers to the process of collaboratively developing a shared strategic plan dictating the direction and course of the program. It is intended to be a living, dynamic document that is owned by both partners and leadership. It provides direction internally to the program and externally to partners. The plan is characterized by flexibility and responsiveness to the context and to funding directives while maintaining integrity to the vision and mission put forth in the planning process.

Partnerships

The Partnerships element emphasizes that the right relationships make the difference in program capacity. It emphasizes quality, strategic unions over a quantity of acquaintances. These strategic partners define mutual responsibilities and goals to share strengths, reduce risk, and increase the likelihood of successful outcomes. It is equally important to focus on strategic partnerships within a specific context.

Leadership

This element refers to both formal and informal leaders. It is people, their expertise, and a dynamic process. Leadership serves as a catalyst for program achievement and does not always have to be the focus of attention.6,20 Collins20 stated that great leaders are comfortable with the idea that most people will not know that the roots of success lead back to them. Good leadership has been shown to facilitate the development of relationships, communication, funding, and direction—often providing the needed link between program elements.21 Leadership can be characterized by an accessible style that is receptive to prudent innovation and risk taking. Leadership is also able to focus on cultivating the development of new leaders.2,13,14 Goodman and colleagues13 stated that a healthy community needs diverse leadership. Viewing a program as an interactive community, the same would be true for program infrastructure.

Managed Resources

This element refers to both people and funding. Collins20 noted that having the right people is your most important asset. The “right” people are appropriately skilled and continually trained to maintain those skills. In addition, they feel ownership of the program. Managed resources also means an active stance toward leveraging and directly braiding funds from different sources to ensure that no single source of funding could close the program’s doors. The element of “resources” is modified by the term “managed” to highlight that it is more than just seeking funding from any and all sources and being led more by the funding requirements rather than the program’s goals and vision.13 Moreover, the resources are in place and the program is ready to both take advantage of opportunities and defend against threats.

Engaged Data

Data are essential to program achievement and must be used for action and not merely collected, disseminated, or displayed.22 It is not enough to hope that published data will be used but requires the actions and follow-through to ensure data will be used. Data include needs assessment, surveillance, and program evaluation.

Is the EMI Applicable to a Broader Public Health Context?

The relationships depicted in the EMI were derived from oral health programs, but it is not clear whether it applies across other types of health programs. To evaluate the applicability of the EMI to other public health programs, we undertook an exploratory literature review. The literature search was conducted to locate documents and articles (1997–2010) that specifically discussed the importance of infrastructure or capacity in the implementation of public health programs. We searched OVID (including PsycINFO and MEDLINE), PubMed, and Google Scholar. Search terms included “infrastructure,” “capacity,” “public health,” and “programs.” Peer-reviewed publications, gray and fugitive literature, and book chapters were included if they met the criteria of directly reporting on program infrastructure in public health programs. “Capacity” documents were included only if it was clear that capacity was being defined as a public health program infrastructure. An electronic search was supplemented by reviews of state and national reports, consultation with experts, conference and workshop presentations, and references in the authors’ personal files. Documents that did not address public health program implementation infrastructure were excluded.

Twenty-five documents were identified that directly reported infrastructure or capacity related to implementation of public health programs. To determine support for all of the EMI constructs, the following terms were used to develop a code book: Engaged Data, Leadership, Managed Resources, Partnerships, State Plans, Strategic Understanding, Tactical Action, and Contextual Influences. In addition, elements not in the EMI, sustainability and outcomes, were added to the codebook. This was done to explore our assumption that such elements were missing from the EMI and necessary for a full description of public health program infrastructure. All documents were coded independently by 2 authors. Elements coded were classified as strongly supported by the literature if more than 75% of the documents mentioned them. Elements coded were defined as having moderate support if less than 75%, but more than 50%, mentioned them. Elements coded were defined as having weak support if less than 50% of documents mentioned them.

Discussion of Literature Review Findings

The Appendix identifies the sources of this review, and the Table presents the findings. Almost all of the documents discussed the importance of tactical action (n = 25), partnerships (n = 24), managed resources (n = 24), engaged data (n = 24), and leadership/staff (n = 23) to program infrastructure. A little more than two-thirds described the importance of context (n=17) to program infrastructure. Less directly supported, but greater than half, were Strategic Understanding (n = 14) and State Plans (n = 13). Strategic Understanding may not have been found across the documents reviewed because it is less tangible. Programs may be less likely to report on it because it is not typically replicable across sites. It is possible that more support would be found for State Plans if the construct were defined as including the planning process as well as the actual plan. However, for the purposes of this project, the written plan had to be explicitly included in the source to be considered providing “support for the element.” Alternatively, as a popular funding activity, State Plans may be developed as a requirement and not in a manner that is conducive to actual program use. This element warrants further exploration.

TABLE.

Support of Ecological Model of Infrastructure Constructs Across Public Health Topic Areas and Programs in Documents Reviewed

| Topic Area | State Plans | Partnerships | Leadership | Managed Resources |

Engaged Data |

Strategic Un- derstanding |

Tactical Action |

Context | Outcomes | Sustainability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adolescent Reproductive Health23 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Asthma24–26 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Asthma24,27,28 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Asthma29 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Communities, CDC Symposium13 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Community Building30 | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Community Health/Florida31 | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Community/City Health32 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Community Health/New Hampshire33 | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Diabetes34 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Nonprofit Performance35 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Oral Health36 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Physical Activity37 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Prevention Programs38 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Racial Health Disparities39 | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Sexual Violence40 | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| State Health Department Chronic Disease Programs41 | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| State Public Health Departments; Accreditation42 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Substance Abuse Prevention Services43 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Tobacco Control and Prevention44 | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Tobacco Control and Prevention45 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Tobacco Control and Prevention46 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Tobacco Control and Prevention17 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| USAID, Developing Country Health Systems12 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Youth Services47 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

Abbreviations: CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; USAID, United States Agency for International Development.

In summary, the intent of the exploratory literature review was to consider infrastructure as depicted by all the constructs in the EMI, with layers that interact to engage the environmental context and impact outcomes. Across documents from a variety of public health programs, strong support for 4 of the essential elements was found. Support varied from moderate to strong for the enveloping constructs of the EMI. This moderate to strong support suggests that consideration of the concept of program infrastructure as depicted by the EMI merits further exploration.

Potential and Challenges

Both the 2002 IOM report and Healthy People 2020 objectives indicate that system wide infrastructure is vital to public health achievements.10,11 Even as a smaller-scale system, program infrastructure warrants serious consideration in implementation and funding structures. This requires an understanding of the elements of program infrastructure and ultimately a demonstration of its link to public health outcomes and sustainability. As public health seeks to redefine itself in a new era of greater linkages to the larger health care system and policies such as the Affordable Care Act, program infrastructure will have an even stronger role to play against threats to the nation’s health.7,48 One of the first challenges we envision is how the new linkages will fit within the existing program infrastructure model.

The EMI provides a first-step prototype for how programs can conceptualize the various layers of infrastructure and the relationships among them. However, when viewed from an implementation standpoint, we found it lacking 2 vital elements, “outcomes” and “sustainability.” As previously discussed, infrastructure can be perceived as a platform for outcomes and program sustainability. When reviewing the literature, we considered whether documents connected infrastructure to outcomes or sustainability.

Sustainability

Twelve of the documents described a positive connection between infrastructure and sustainability. Sustainability often includes multidimensional and elusive aspects. Goodman and colleagues13 described sustainability as the maintenance of effective, community-based health promotion and disease prevention programs. Brown and Fierro27 described sustainability as the ability to reduce reliance on external assistance and maintain health. Lavinghouze and colleagues14 discussed it as the ability to maintain performance and health achievements while moving the program’s objectives and goals forward. We contend that in the literature as well as in practice, sustainability is all of the above and more. Our working definition of sustainability views it as a dynamic process that includes the ongoing preservation and enhancement of infrastructure elements; the reduction in reliance on a single source of funding; the maintenance of performance and effective programs; and the movement toward health outcomes. As such, we believe that sustainability and its interactive relationship should be further studied and included in the overall depiction of fully functioning program infrastructure.

Outcomes

Twelve documents described a positive connection between infrastructure and outcomes. Infrastructure development is not the “sexy” part of determining public health outcomes. This may be because it is particularly difficult to link to outcomes. For example, who can determine how much reduction in prevalence of a particular disease a program achieved because it developed leadership, provided technical assistance, or developed a state plan? Also, nurturing relationships for infrastructure takes time, energy, and resources, which may conflict with the usual focus on immediate outcomes. Typically, those activities with invisible, indirect links to outcomes are the first to be discarded through funding decisions.17 As described earlier, few programs are allowed the luxury of investing in infrastructure because of the pressure to focus on outcomes. Although not described here, the EMI posits that there are processes and proximal indicators that connect infrastructure elements to outcomes in a positive direction, even if it is not a direct, linear path.1–3 More thought and studies are needed on the connection between infrastructure and outcomes to encourage financial support for developing infrastructure. At the very least, a link to outcomes should be included in graphic depictions of infrastructure.

According to the EMI, the Essential Elements interact, informed by Strategic Understanding and Tactical Action, resulting in the capacity to effectively implement program activities and achieve outcomes that promote progress on health and sustainability.2 From our perspective, the EMI has the potential to guide further development and definition of infrastructure. Utilization, application, and revisions of the EMI over time could provide the information that grant planners, evaluators and researchers, and program implementers need to measure success, to link infrastructure to capacity, and to understand the likelihood of sustainable health achievements. Strengthening the link between infrastructure and outcomes would allow programs to demonstrate progress on milestones while waiting for distal outcomes to be realized. An evidence-based program infrastructure model that depicts the link between infrastructure, capacity, outcomes, and sustainability could serve as a framework for making program decisions and valuing the foundation that supports public health outcomes. According to a recent IOM report, a framework for assessing value can aid decision making, among other things, by promoting transparency.48(p90)

The major overarching constructs and Essential Elements of the EMI are supported in the literature across several different types of public health programs and warrant further in-depth study for ways of applying and refining the model. The central challenge of the EMI is to fully explain how the elements are linked to one another, how this interaction promotes progress on health achievements, and sustainability.

While additional work is required to fully construct an evidence-based model of program infrastructure, the EMI is a strong, first step at depicting the complexities of program infrastructure. The next task is to obtain new data to develop model elements in a manner that demonstrates the power of the interaction of the core elements, the larger layers of influence, and their connection to outcomes and sustainability.

Acknowledgments

Ms Snyder was supported through the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) funding (Pub L 111-5)/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Communities Putting Prevention to Work Cooperative Agreement DP09-901 (supplement) under contract: Monitoring and Evaluation of the ARRA and ACA Communities and States with ICF International.

APPENDIX

Public Health Topic Areas and Citations

| Topic Area | Type of Document | Citation |

|---|---|---|

| Adolescent Reproductive Health | Peer-reviewed journal article | Rolleri et al23 |

| Asthma | Slides from presentation at professional conference | Orians et al,26 Fierro et al,24 Giles25 |

| Asthma | Slides from presentation at professional conference | Brunner et al,28 Fierro et al,24 Brown and Fierro27 |

| Asthma | Peer-reviewed journal article | Parker et al29 |

| Communities, CDC Symposium | Peer-reviewed journal article | Goodman et al13 |

| Community Building | Book | Mattessich and Monsey30 |

| Community Health/Florida | Peer-reviewed journal article | Abarca et al31 |

| Community/City Health | Peer-reviewed journal article | Kegler et al32 |

| Community Health/New Hampshire | Peer-reviewed journal article | Kassler and Goldsberry33 |

| Diabetes | Peer-reviewed journal article | Ottoson et al34 |

| Nonprofit Performance | Book | Connolly and Lukas35 |

| Oral Health | Report | Association of State and Territorial Dental Directors36 |

| Physical Activity | Peer-reviewed journal article | Calise and Martin37 |

| Prevention Programs | Peer-reviewed journal article | Flaspohler et al38 |

| Racial Health Disparities | Peer-reviewed journal article | Griffith et al39 |

| Sexual Violence | Slides from presentation at CDC grantee meeting | Cox40 |

| State Health Department Chronic Disease Programs | Book | Wheeler41 |

| State Public Health Departments; Accreditation | Peer-reviewed journal article | Brewer et al42 |

| Substance Abuse Prevention Services | Peer-reviewed journal article | Livet et al43 |

| Tobacco Control and Prevention | Peer-reviewed journal article | Harris et al44 |

| Tobacco Control and Prevention | Peer-reviewed journal article | Nelson et al45 |

| Tobacco Control and Prevention | Peer-reviewed journal article | Robbins and Krakow46 |

| Tobacco Control and Prevention | Report | Tobacco Control Monograph No. 17. NIH Pub. No. 06-6058 (2006)17 |

| USAID, Developing Country Health Systems | Report | Brown et al12 |

| Youth Services | Book | Bumbarger et al47 |

Abbreviations: CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; USAID, United States Agency for International Development.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

No other authors or persons contributed significant intellectual thought or writing to this article. The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

CDC cooperative agreement nos. 1046 and 3022.

“Oral Health Infrastructure: Navigating the Path to Outcomes” unpublished report, submitted to the Center of Disease Control and Preventions, Division of Oral Health (http://www.cdc.gov/oralhealth/), March 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lavinghouze R. What’s in a story? Giving a voice to multisite programs. Paper presented at: 23rd Annual Meeting of the American Evaluation Association; November 12, 2009; Orlando, FL. [Accessed July 3, 2011]. http://www.eval.org. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lavinghouze S, Ottoson J, Maietta R, et al. Investment in infrastructure. Paper presented at: Annual National Oral Health Conference; April 22, 2009; Portland, OR. [Accessed July 3, 2011]. http://www.nationaloralhealthconference.com/index.php?page=presentations. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ottoson J. Results of an evaluation of oral health capacity building efforts. Paper presented at: Annual American Public Health Association Conference; November 10, 2009; Philadelphia, PA. [Accessed July 3, 2011]. http://www.apha.org/meetings/pastfuture/pastannualmeetings.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roper W, Baker E, Dyal W, Nicola R. Strengthening the public health system. Public Health Rep. 1992;107(6):609–615. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Handler A, Issel M, Turnock B. A conceptual framework to measure performance of the public health system. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(8):1235–1239. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.8.1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turnock BJ. Public Health: What It Is and How It Works. Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baker EL, Potter MA, Jones DL, et al. The public health infrastructure and our Nation’s health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26:303–318. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Public Health’s Infrastructure: Every Health Department Fully Prepared, Every Community Better Protected: A Status Report. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 1999. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Powles J, Comim F World Health Organization. Public Health Infrastructure and Knowledge. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2012. [Accessed December 17, 2012]. http://www.who.int/trade/distance learning/gpgh/gpgh6/en/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 10.The Future of the Public’s Health in the 21st Century. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2002. Board on Health Promotion and Disease Prevention, Institute of Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2020—public health infrastructure objectives. [Accessed July 3, 2011]; http://healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/objectiveslist.aspx?topicid=35. Published 2011.

- 12.Brown L, LaFond A, Macintyre K. Measuring Capacity Building. Chapel Hill, NC: Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; 2001. Report No. HRN-A-00-97-00018-00. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goodman R, Speers M, Mcleroy K, et al. Identifying and defining the dimensions of community capacity to provide a basis for measurement. Health Educ Behav. 1998;25(3):258–278. doi: 10.1177/109019819802500303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lavinghouze S, Price A, Parsons B. The environmental assessment instrument: harnessing the environment for programmatic success. Health Promot Pract. 2009;10(2):176–185. doi: 10.1177/1524839908330811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chapman R. Organization Development in Public Health: A Foundation for Growth. 2010 White Paper. http://www.leadingpublichealth.com/writings&resources.html. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hannah G. Maintaining product-process balance in community antipoverty initiatives. Soc Worker. 2006;51(1):9–17. doi: 10.1093/sw/51.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Cancer Institute. Evaluating ASSIST: A Blueprint for Understanding State-Level Tobacco Control. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2011. Report No. 17. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Senge P. The Fifth Discipline: The Art & Practice of the Learning Organization. Rev ed. New York, NY: Doubleday; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Public Health Service. The Public Health Workforce: An Agenda for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services; [Accessed December 6, 2012.]. http://www.health.gov/phfunctions/pubhlth.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Collins J. Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap … and Others don’t. New York, NY: Harper Collins; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ricketts KG, Ladewig H. A path analysis of community leadership within viable rural communities in Florida. Leadership. 2008;4(2):137–157. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patton M. Essentials of Utilization-Focused Evaluation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rolleri L, Wilson M, Paluzzi P, Sedivy V. Building capacity of state adolescent pregnancy prevention coalitions to implement science-based approaches. Am J Community Psychol. 2008;41(3/4):225–234. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9177-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fierro L. Keep an eye on the basics: The importance of evaluating public health program infrastructure. Paper presented at: 24th Annual Meeting of the American Evaluation Association; November 11, 2010; San Antonio, TX. [Accessed July 3, 2011]. http://www.eval.org. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giles R. The value and utility of evaluating public health partnerships: an example from Utah. Paper presented at 24th Annual Meeting of the American Evaluation Association; November 11, 2010; San Antonio, TX. [Accessed July 3, 2011]. http://www.eval.org. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Orians C, Rose S, Winges L, Gill S, Shrestha-Kuwahara R. Evaluation in support of high-quality asthma partnerships. Paper presented at: 24th Annual Meeting of the American Evaluation Association; November 11, 2010; San Antonio, TX. [Accessed July 3, 2011]. http://www.eval.org. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brown A, Fierro L. Evaluation as a program improvement tool: Evaluation of asthma surveillance. Paper presented at: 24th Annual Meeting of the American Evaluation Association; November 11, 2010; San Antonio, TX. [Accessed July 3, 2011]. http://www.eval.org. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brunner W. The value and utility of evaluating public health surveillance: Asthma mortality rates among seniors in Minnesota. Paper presented at: 24th Annual Meeting of the American Evaluation Association; November 11, 2010; San Antonio, TX. [Accessed July 3, 2011]. http://www.eval.org. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parker E, Chung L, Israel B, Reves A, Wilkins D. Community organizing network for environmental health: using a community health development approach to increase community capacity around reduction of environmental triggers. J Prim Prev. 2010;31:41–58. doi: 10.1007/s10935-010-0207-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mattessich P, Monsey B. Community Building: What Makes it Work a Review of Factors Influencing Successful Community Building. Saint Paul, MN: Wilder Publishing Center; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abarca C, Grigg C, Steele J, Osgood L, Keating H. Building infrastructure and capacity for community health assessment and health improvement planning in Florida. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2009;15(1):54–58. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3181903c42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kegler M, Norton B, Aronson R. Achieving organizational change: findings from case studies of 20 California healthy cities and community coalitions. Health Promot Int. 2008;23(2):109–118. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dan009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kassler W, Goldsberry Y. The New Hampshire public health network: creating local public health infrastructure through community-driven partnerships. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2005;11(2):150–157. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200503000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ottoson J, River M, DeGroff A, Hackley S, Clark C. On the road to national objectives: a case study of diabetes prevention and control programs. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2007;13(3):41–58. doi: 10.1097/01.PHH.0000267687.15906.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Connolly P, Lukas C. Strengthening Nonprofit Performance: A Funder’s Guide to Capacity Building. Saint Paul, MN: Wilder Publishing Center; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Association of State and Territorial Dental Directors. ASTDD Competencies for State Oral Health Programs. Sparks, NV: Association of State and Territorial Dental Directors; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Calise T, Martin S. Assessing the capacity of state physical activity programs—a baseline perspective. J Phys Act Health. 2010;7(1):119–126. doi: 10.1123/jpah.7.1.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Flaspohler P, Duffy J, Wandersman A, Stillman L, Maras M. Unpacking prevention capacity: an intersection of research-to-practice models and community-centered models. Am J Community Psychol. 2008;41:182–196. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9162-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Griffith D, Allen J, DeLoney E, et al. Community-based organizational capacity building as a strategy to reduce racial health disparities. J Prim Prev. 2010;31:31–39. doi: 10.1007/s10935-010-0202-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cox P. An overview of prevention system capacity for intimate partner violence prevention. Paper presented at: DELTA Program Grantee Meeting; March 15, 2007; Atlanta, GA. [Accessed July 3, 2011]. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wheeler F. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Promising Practices in Chronic Disease Prevention and Control: A Public Health Framework for Action. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2003. State programs: leadership, partnerships, and evidence-based interventions; pp. 1.1–1.9. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brewer R, Joly B, Mason M, Tews D, Thielen L. Lessons learned from the multistate learning collaborative. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2007;13(4):388–394. doi: 10.1097/01.PHH.0000278033.64443.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Livet M, Courser M, Wandersan A. The prevention delivery system: organizational context and use of comprehensive programming frameworks. Am J Community Psychol. 2008;41:361–378. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9164-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harris J, Luke D, Burke R, Mueller N. Seeing the forest and the trees: using network analysis to develop an organizational blueprint of state tobacco control systems. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(11):1669–1678. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nelson D, Reynolds J, Luke D, et al. Successfully maintaining program funding during trying times: lessons from tobacco control programs in five states. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2000;13(6):612–620. doi: 10.1097/01.PHH.0000296138.48929.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Robbins H, Krakow M. Evolution of a comprehensive tobacco control programme: building system capacity and strategic partnerships—lessons from Massachusetts. Tobacco Control. 2000;9:423–430. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.4.423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bumbarger B, Perkins D, Greenberg M. Taking effective prevention to scale. In: Doll B, Pfohl W, Yoon J, editors. Handbook of Youth Prevention Science. New York: Taylor & Francis; 2010. pp. 433–444. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Institute of Medicine. An Integrated Framework for Assessing the Value of Community-Based Prevention. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]