Abstract

Public health authorities have adopted entry screening and subsequent restrictions on travelers from Ebola-affected West African countries as a strategy to prevent importation of Ebola virus disease (EVD) cases. We analyzed international, federal, and state policies—principally based on the policy documents themselves and media reports—to evaluate policy variability. We employed means-ends fit analysis to elucidate policy objectives. We found substantial variation in the specific approaches favored by WHO, CDC, and various American states. Several US states impose compulsory quarantine on a broader range of travelers or require more extensive monitoring than recommended by CDC or WHO. Observed differences likely partially resulted from different actors having different policy goals—particularly the federal government having to balance foreign policy objectives less salient to states. Further, some state-level variation appears to be motivated by short-term political goals. We propose recommendations to improve future policies, which include the following: (1) actors should explicitly clarify their objectives, (2) legal authority should be modernized and clarified, and (3) the federal government should consider preempting state approaches that imperil its goals.

Public health authorities have adopted entry screening and other restrictions on travelers from Ebola-affected West African countries as a strategy to prevent importation of Ebola virus disease cases. The authors analyzed international, federal, and state policies to evaluate variations in policies; they found substantial differences among the specific approaches favored by WHO, CDC, and various American states. Several US states impose compulsory quarantine on a broader range of travelers or require more extensive monitoring than recommended by CDC or WHO. Differences in policies likely resulted in part from different policy goals, and some state-level variation appears to be motivated by short-term political goals. The authors propose recommendations to improve future policies.

The West African Ebola epidemic gained both wide public attention and political importance in the United States in early August 2014, spurred principally by 2 events: (1) the infection of 2 US healthcare workers in Liberia and their subsequent repatriation to the United States, and (2) an outbreak in Nigeria that had an American citizen of Liberian origin as its index case.1 This salience deepened when the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the West African Ebola epidemic a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC) under the International Health Regulations on August 8, 2014.2 Public fears increased in the United States in late September when a Liberian man contracted the virus while coming to the aid of a sick neighbor in Monrovia, developed Ebola virus disease (EVD) a week later after traveling to Texas, and subsequently transmitted the infection to American healthcare workers.3

In October 2014, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) initiated enhanced screening and management of individuals entering the United States who had recently traveled in Ebola-affected countries. In broad strokes, this meant working with airlines to restrict US entrants to 5 airports with enhanced screening services and an exposure-based approach to risk assessment.4,5 In late October, CDC revised its guidance to adopt risk tiers with corresponding restrictions.6 CDC guidance recommended that asymptomatic people with no known exposures—including healthcare providers who consistently wore appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) while treating patients—be actively monitored for fever and other Ebola symptoms but that their movement did not need to be restricted. Tiered controls for those with higher-magnitude exposure risks and isolation of symptomatic individuals were also recommended.7 By March 8, 2015, every US state, 2 territories, New York City, and the District of Columbia had monitored at least 1 returned traveler. More than 10,000 travelers were monitored in total.8

Many states, however, diverged from CDC guidance, requiring more frequent or intrusive testing or greater restrictions on movement, such as quarantine of returned health workers.9 (An up-to-date map of state policies can be found at http://www.cdc.gov/phlp/publications/topic/ebola.html.) From a health systems improvement perspective, varying interventions may be appropriate if they reflect different programmatic goals, or when program contexts require unique intervention approaches. (For example, a jurisdiction with very limited surveillance and response capability might be more risk averse about potentially infected entrants.) However, unexplained variability often suggests suboptimal interventions or implementation10-13 and can challenge effective communication of risks to the public and stakeholders.14

Because the epidemiologic context of Ebola was essentially invariant across US states, policy variability might reflect state innovation that attempted to improve on CDC guidance. Alternatively, it might signal that states sought different goals from CDC—whether they be public health or political ones. Additionally, different approaches could reflect public health system capacities and capabilities, including variation in states' public health laws.15 However, one would not expect substantially different public health capacities and capabilities across states because the number of cases—either actual or expected—was insufficient to overtax state public health systems, and because, although Ebola has an unusually high case-fatality rate, basic Ebola control measures (ie, surveillance, contact tracing, and quarantine) are not dissimilar from other infectious disease public health activities.

This analysis aims to explain observed variation in US Ebola entry screening and controls in order to inform recommendations that may improve responses to future public health emergencies. To do so, we analyzed several sources of information. Our analysis began with states' policies themselves—drawing from CDC's recent compilation of Ebola screening and restriction policies9 and supplementing these data with additional official policy documents. We further contextualized policy by examining official government statements and news reports that accompanied or explained policy decisions. Finally, information about certain jurisdictions' approaches—federal, District of Columbia, Florida, and Massachusetts—was obtained by the authors' firsthand interaction during their own screening and monitoring experiences. We sought to understand the variability in approaches by examining their fit with stated policy goals. If the fit was poor, we sought to explain the approach by reference to unstated or alternative goals or contextual differences between jurisdictions.

Variability in Entry Screening and Traveler Controls

This section considers recommendations or requirements made at 3 political levels: global, through WHO; national, principally through CDC; and US states. Others have assessed the potential effectiveness of exit screening, entry screening, and movement restrictions in the context of Ebola and other infectious diseases (though no studies have directly assessed the repeated symptom monitoring and tiered controls approach recommended by CDC),16-25 and our purpose is not to reassess the overall value of the control measures employed by various jurisdictions. Rather, we seek to characterize and explain variability in approaches taken in order to identify challenges that are likely to recur during future public health emergencies.

World Health Organization

Pursuant to the International Health Regulations (IHR), WHO provides guidance to member states regarding appropriate measures in response to PHEICs. Throughout the West African Ebola epidemic, WHO has favored exit screening and travel restrictions by affected countries over entry screening by unaffected countries, and it has recommended that exit restrictions be limited to people with symptoms consistent with Ebola or who have had contact with a case.26 It has not recommended entry screening,27 and it has signaled that “entry screening may have a limited effect in reducing international spread when added to exit screening.”28 At the same time, WHO has called for states that have implemented entry screening to “share their experiences and lessons learned,” and it has provided technical guidance on how to conduct entry screening with minimal collateral harm to trade, travel, or individual liberties.27,28 While specifying that Ebola contacts and cases should not be permitted to travel, WHO does not recommend travel restrictions for healthcare workers who used appropriate PPE and without other exposures.26,29

US Federal Government

Federal policy in the United States has evolved over the course of the West African Ebola outbreak. CDC did not recommend extensive entry screening and controls of asymptomatic people during the epidemic's early stages. Although there was political pressure to limit travel after a man with Ebola symptoms was permitted to board a flight from Monrovia to Lagos in August,30 CDC and the State Department recommended only against nonessential travel to affected countries.31,32 Around the same time, US Ebola policy was principally focused on supporting affected countries' responses—including by providing support to exit screening.33 Active airport screening began in October 2014, at the same time that the US government barred travelers from affected countries from entering except through 5 designated airports.4,34 Passengers with Ebola signs or symptoms or high-risk exposures would not be permitted further travel until assessed and cleared.35 Initially, healthcare workers who used appropriate PPE while treating patients were generally assessed as low risk. However, in late October, after healthcare workers caring for a patient in Dallas were infected and an American physician returned to the United States from Guinea and developed EVD, healthcare workers who used PPE in West Africa—but not in the United States—were reclassified as “some risk.”7,36

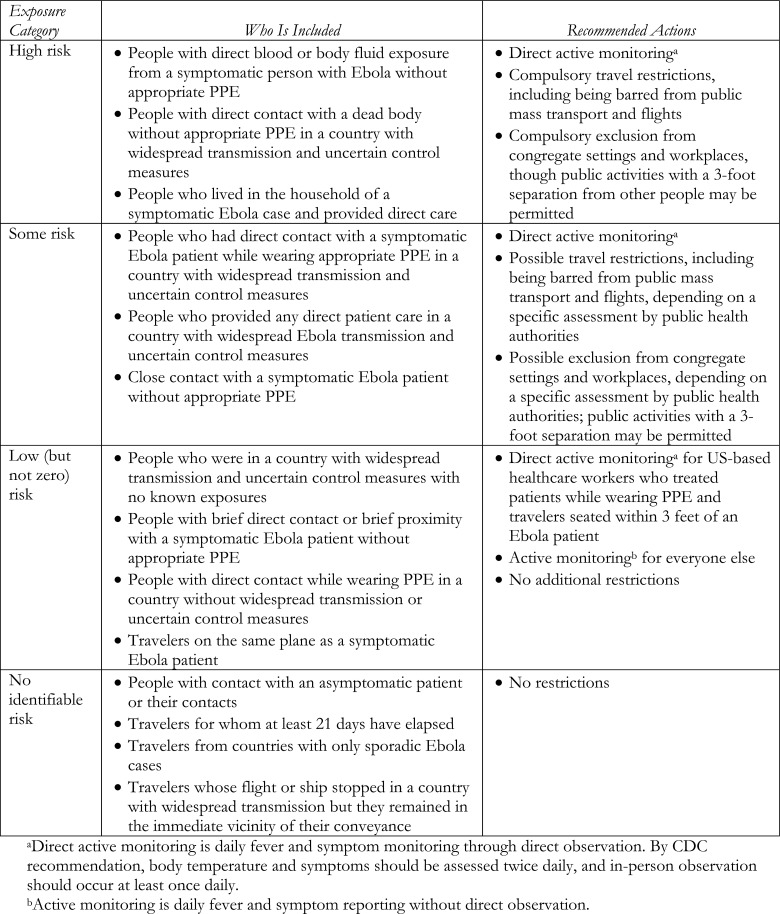

Since late October 2014, CDC has recommended movement restrictions for asymptomatic entrants based on a tiered-risk system. (See Figure 1 for risk tiers and CDC's recommended restrictions. Up-to-date information on current risk tiers can be found at http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/exposure/monitoring-and-movement-of-persons-with-exposure.html.) No restrictions beyond daily active monitoring (required temperature reporting by the entrant) are required for most people in the low-but-not-zero risk category. (US-based healthcare providers who cared for an Ebola patient or people who sat within 3 feet of an Ebola patient on an airplane are to have direct active monitoring, in which a public health official “directly observes the individual at least once daily.” 7) Those in the “some risk” category, which includes healthcare workers who treated patients in West Africa while wearing appropriate PPE, are to have direct active monitoring. CDC also advises state and local health departments to individually assess the entrant and decide the appropriateness of exclusion from congregate settings; travel by bus, aircraft, or subway; public places; or workplaces. CDC is clear, however, that this should not cause home quarantine and that noncongregate activities in public settings (for which CDC's example is jogging in a public park) may be permitted. Further, CDC recommends that asymptomatic entrants in the “some risk” category should be allowed to travel by air from their US port of entry to their final destination before flight restrictions are imposed.7 CDC recommends that asymptomatic high-risk entrants be, at minimum, excluded from public means of transport, public places and congregate gatherings, and workplaces, though they too may be permitted to maintain noncongregate public activities. High-risk asymptomatic entrants are not permitted to travel on commercial flights.7

Figure 1.

CDC's Exposure Categories and Recommended Actions for Asymptomatic Individuals

US States

In the United States, states have broad public health powers37 and can impose restrictions that exceed federal policy, except in certain instances where state policies conflict with federal authority and are preempted by federal law and the Constitution's Supremacy Clause.38 To a large degree, this reflects the historical primacy states have had in controlling public health threats.39-41 As of March 2015, 19 states have stricter Ebola policies than CDC guidance. Several deviations from CDC guidance are particularly notable.

Only 5 states—Georgia, Illinois, New Jersey, New York, and Virginia—have airports through which travelers from affected countries are permitted to enter the United States by air. Consistent with CDC guidance, Georgia, Illinois, and Virginia permit healthcare workers who treated patients in West Africa while wearing PPE to continue to their final destinations.9,42 New Jersey does not permit asymptomatic healthcare workers who treated patients in West Africa—even if they wore appropriate PPE—to continue air travel to their final destination.43,44 For a short period in October, New York appears to have established the same policy,45-47 though it does not appear to have been implemented before being reversed.48-50

Several jurisdictions, including the District of Columbia,51 Florida,52 Iowa,53,54 Maine,55,56 New Jersey,43 New York,48,57 and Ohio,58,59 compel the quarantine of healthcare workers who cared for Ebola patients in West Africa even if they used appropriate PPE and had no known unprotected exposures.9 Kansas requires quarantine of healthcare workers unless they used “tier 1” PPE, which includes a powered air purifying respirator (PAPR)—a device rarely used in West Africa.60 New Hampshire policy also calls for voluntary quarantine. It reserves the right to impose mandatory quarantine, but also states that compulsory quarantine would not normally be used.61 Each of these states permit quarantine in a person's own home instead of confinement in a medical facility, except for travelers detained in New Jersey before reaching their home states.43

Maine's policy also authorizes quarantine of people who “treat[ed] Ebola-positive individuals,” including those who wore appropriate PPE.55 However, a state trial court judge struck down quarantine of a nonsymptomatic, potentially exposed nurse as inconsistent with state law because quarantine was more restrictive than necessary to protect the public's health.62,63 Although it was not at issue in that court case, Maine's communicable disease laws are written ambiguously. While Maine's health department issued regulations that authorize quarantine of exposed individuals,64 it is not clear it has this statutory authority. State code authorizes detention to address a “public health threat,” but it then defines legal terms of art in a way that appears only to authorize the detention of people actually diagnosed with an infection—not those who are merely exposed—unless the state declares a public health emergency (see explanatory web supplement at www.liebertonline.com/hs).65-67 When a public health emergency has been declared, the state has clear statutory quarantine authority, but Maine did not declare a public health emergency.67-69

Louisiana's quarantine policy is also unclear.70 It applies to all people who have been in an affected country within the past 21 days (including, but not limited to, healthcare workers), and, on its face, it calls only for “voluntary quarantine” or “self-quarantine.” However, elsewhere in the policy, the state references its authority to enforce its powers by public health order, and, in at least one instance, travelers from affected countries to a tropical medicine conference were informed “that we see no utility in you traveling to New Orleans to simply be confined to your [hotel] room.”71,72 It is unclear whether the state has or would seek legal enforcement if someone refused voluntary quarantine.

Connecticut's official policy matches CDC's recommendations and risk tiers, but its implementation of that policy appears to have exceeded them.9,73 In early October, Connecticut's governor declared a public health emergency to allow broader Ebola powers.74,75 In the absence of a state emergency declaration, only local health departments—not the state—would have quarantine authority.76-78 In at least one case, a Yale student who returned from Liberia was quarantined after developing a fever and subsequently testing negative for Ebola. Other travelers were quarantined without a history of exposure.79

Multiple states require more intrusive daily monitoring for people in the “low (but not zero)” tier than CDC recommends.9 Florida requires the standard twice-daily temperature and symptom checks to be conducted in the presence of a public health worker.52 Texas's policy is unclear and in one formulation appears to require observed temperature readings,80 but not in another.81 New Mexico initially required low-but-not-zero risk individuals to be available for in-person monitoring but stopped short of requiring in-person monitoring per se;9 its policy was amended to match CDC guidance in February 2015.82 Ohio requires 1 in-person and 1 phone check-in each day.59 Indiana requires video monitoring of temperature twice per day regardless of risk tier.83,84

Goals

One reason for the variability in entry screening and subsequent controls may be that different jurisdictions sought to achieve different goals. Indeed, if public health goals varied, it would be concerning not to see different approaches.10,12,13 Similarly, different actors might choose different approaches to achieving the same objective if they encounter different programmatic contexts or if their public health systems have different capacities and capabilities.85,86 However, in the United States the epidemiologic context was essentially constant across states, and the expected number of cases was insufficient to likely overtax state public health capabilities.18,87 Finally, variability—particularly when there is a poor fit between stated ends and chosen means—may signal that actors have unstated goals at which a policy solution is aimed.88-90

World Health Organization

When WHO recommends disease control measures during a PHEIC, it is explicitly guided by the goals of the IHR. The IHR seek to balance 2 objectives: “to prevent, protect against, control, and provide a public health response to the international spread of disease,” and to “avoid unnecessary interference with international traffic and trade.”91 Not surprisingly, WHO member states would be wary of granting WHO emergency declaration and control measure recommendation authority if WHO did not take reasonable care to avoid harming their economic interests.92-94

WHO's guidance is broadly consistent with these dual objectives and with the significant deference it tends to give member states. Throughout the epidemic, WHO has recommended against international trade and travel restrictions28,29,95,96—even while broadly approving of subnational cordon sanitaire within affected countries (despite a lack of evidence to support them).97,98 More specifically, WHO has unequivocally favored exit screening from affected countries,29 while it has been much more ambivalent about entry screening,28 and it has consistently opposed entry bans or quarantines of asymptomatic travelers without known Ebola exposure, which it condemned for “impeding the recruitment and return of international responders … and … disrupting livelihoods and economies.”96 Though it never expressed it explicitly, WHO may have adopted this policy because it expected fewer unnecessary interruptions would occur by placing primary authority for traveler restrictions in the hands of affected countries and because exit screening can be targeted to fewer flights.18,20,99

US Federal Government

The US government, while primarily focused on domestic health and security, also has to balance international obligations (including under the IHR),91 commitments to allies (including those made to Liberia and other affected countries),100,101 and broader international relations goals. Further, federal public health officials repeatedly stated that, in their estimation, the most effective way to prevent imported cases was to expeditiously end the West African outbreak.102 In line with these goals, prior to the importation of an Ebola case to Dallas, US policy remained principally focused on aiding the affected countries to respond and protecting against cases among entrants by supporting exit screening in West Africa.33

The situation changed dramatically in October after a traveler from Liberia became ill with EVD in Texas and additional cases were diagnosed among nurses who cared for him. Though epidemiologists had expected sporadic imported cases due to Ebola's long incubation period, health officials had emphasized that the United States could rapidly and fully contain subsequent transmission, using language that, while epidemiologically correct, led some to believe that there would be no instances of domestic transmission.103 The Texas cases fundamentally changed the public conversation in 2 ways. First, expectation of imported cases was converted from theoretical to actual. Second, the infection of 2 nurses who provided clinical care for the Dallas index case undermined confidence in CDC's ability to contain further transmission.104 This, along with election-year politics, led to renewed calls to ban travelers arriving in or returning to the United States from affected West African countries.104-107

Against this backdrop, the Obama administration had to balance its multiple Ebola-related goals. The administration believed a travel ban would reduce the ability of responders to deploy to Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea, which it believed would result in an exacerbated West African epidemic and increase the likelihood of imported cases.108,109 Further, it believed an entry ban would make travelers less likely to truthfully disclose whether they had been in an affected country, making surveillance more difficult.107 Thus, the October policy changes to restrict entrants to 5 airports and subsequent production of a tiered screening and monitoring strategy is best interpreted as a way for the administration to balance its foreign policy goals with the risk of congressional action to impose severe restrictions on travel from West Africa.

US States

Unlike the federal government, states do not explicitly create foreign policy and therefore have few political incentives to avoid complicating competing federal foreign policy goals if they perceive a conflict with state-level priorities.110,111 At a macroscopic level, then, one would expect states to be more likely to impose stricter controls than the federal government. Not surprisingly, one-third of US states did, in fact, impose stricter controls than CDC recommended.9

Yet, a different balance between globally and locally oriented public health priorities does not explain several deviations from federal policy. While every state justified its deviation from federal policy by claiming an interest in preventing transmission of Ebola and protecting the public health, at least 2 states, New York and New Jersey, adopted airport quarantine policies without evidence of public health benefit.

When New Jersey and, briefly, New York decided to quarantine asymptomatic healthcare workers at Newark and JFK Airports—many of whom would be traveling elsewhere—protection of their states could not have justifiably been the overriding public policy goal. After all, a currently asymptomatic person could not transmit disease, and the likelihood of a person becoming infectious after entry screening but while still in the airport is vanishingly small. The lack of fit between New Jersey and New York's stated ends and their chosen means suggest there existed a latent objective.88-90

A leading hypothesis proposed for that objective is non–public-health-oriented: electoral politics.112 The policy adopted in New York and New Jersey was announced a few days after a physician who had returned from Guinea was diagnosed with Ebola and 11 days before November gubernatorial elections. Language that accompanied the policy announcement from the office of New York Governor Andrew Cuomo, who was running for reelection, signals the issue's electoral salience: “For four years, I have erred on the side of caution whenever it has come to dealing with a crisis, and that has served the state well.”113 New Jersey Governor Chris Christie, a likely presidential candidate, meanwhile characterized White House policy on Ebola as “seven minute lectures from the South Lawn.”114

Similarly, language sometimes used in policies requiring quarantine of healthcare providers who had worn appropriate PPE signals that damping public fears, more than Ebola transmission risk, was at play. Louisiana policy, for example, includes the statement, “There is a large body of scientific literature confirming that asymptomatic individuals are not infectious. … Therefore there is no scientific rational [sic] for putting an asymptomatic person under quarantine. However this practice is done under the guise of ‘abundance of caution.’”70 While it is unclear whether Louisiana would use compulsory quarantine if a healthcare worker refused voluntary restrictions, its determination of “no scientific rationale” would apply equally to voluntary quarantine. Maine defends its policy as taking “further measures, out of an abundance of caution, to ensure public safety.”55 While such statements may reflect extreme risk aversion, the most natural explanation is that they reflect a desire by state officials to communicate to the public that Ebola was being handled—that is, that they prioritized mitigation of public fear over disease control objectives—which can yield short-term electoral benefit.

Mitigating fear is, of course, a laudable public objective, so long as it does not lead to unacceptable intrusions on individual liberties or confound public health initiatives to control disease spread. By October 2014, when many states were constructing their policies, public fear had reached exceptional levels, with almost one-fourth of Americans reporting being worried about being infected. Simultaneously, more than a third of Americans reported a lack of confidence that the federal government could manage Ebola.115 There are many likely reasons for this fear, including Ebola's exoticness and confusion of high lethality with easy transmissibility.116 However, in some instances, risk communication by federal officials and other experts likely increased public perceptions that federally recommended control measures were inadequate. These included inopportune statements by CDC Director Thomas Frieden that “essentially any hospital in the country can safely take care of Ebola.”103 Similarly, speculation about the possibility of mutations to enable respiratory transmission of Ebola increased public fear117-120 and may have contributed to states imposing greater-than-necessary controls on healthcare workers who wore adequate PPE, such as Kansas's quarantine of healthcare workers whose PPE did not include PAPRs.

Recommendations

Policy Goals Should Be Clear

Observed variability in international, federal, and state policies are at least partially attributable to varying policy goals. With respect to public health objectives, policymakers likely sought both to prevent individuals infected with Ebola from entering the United States and to minimize morbidity and mortality in the United States. For state policymakers, responding to different incentives, both of these goals could be met by stringent controls. Federal policymakers, though, were concerned that stringent controls would exacerbate the West African epidemic, and so, even if stricter controls reduced the proportion of infected travelers who entered the United States, it might increase the absolute number. Additionally, federal policymakers had to balance additional foreign policy goals, such as being perceived as reliable allies.

In some instances, state policymakers' objectives remained obscured, which is problematic for both practical and principled reasons. Because public health measures—particularly coercive measures that intrude on individual liberties—can only be justified to the extent they are able to achieve an important public goal,121 it is important that officials are clear about the objective of a control measure when implementing it. Failing to do so increases the likelihood that policy will impose public burdens without obtaining public benefits.122

Unspecified goals are also problematic as a matter of principle. Democratic theory requires the possibility of public deliberation about both the ends and means of policy.123 This, of course, does not mean that public preferences prevail when in conflict with scientific principles. However, undisclosed objectives make rational public deliberation impossible.124 Without the possibility of public deliberation, the legitimacy that attaches to democratically constructed or reviewed policy is lost.123

Related to this, while public health is inherently political,125 its objectives ought not be mere politics. Coercive public health measures require publicly oriented justifications.37 Electoral political gain is insufficient to sustain political measures that intrude on individual liberties—including compulsory screening and quarantine. As a result, it is incumbent on political actors to base Ebola control measures on valid public health grounds and to state these grounds openly so that they can be publicly debated.

Clarify Legal Authority

In at least 2 instances, unclear alignment between legal authority and Ebola policy increased uncertainty about state policy. In Maine, communicable disease statutes were construed by a trial court judge to preclude quarantine of asymptomatic Ebola contacts as more extensive than necessary.62 Further, as noted above, Maine law seems to limit quarantine only to people who are actually known to be infected—not merely exposed—to an infectious disease,65 unless a public health emergency has been declared.67 This uncertainty is problematic because, on one hand, it increases the likelihood that public health agencies will be unable to exercise appropriate authority. On the other hand, it also increases the likelihood that public health departments will overreach by trying to fit poorly crafted public health laws to what they perceive to be an urgent situation.126,127

Louisiana may have the opposite problem. Its public health laws clearly authorize the quarantine of exposed, asymptomatic individuals.128 However, Louisiana's Ebola policy drafters openly stated that quarantine is not justified with respect to asymptomatic contacts, and they refer to the state's policy as “voluntary quarantine,” although Louisiana also advised travelers to avoid the state lest they be “confined to [their] room.”71 If this is intended to signal a state policy authorizing compulsory quarantine—and other parts of Louisiana's policy do appear to envision the use of public health orders70—the law would likely not survive judicial review. To be constitutional, quarantine must be justified by a compelling government interest,37,129 and Louisiana has itself stated that no such interest exists. If states seek to use coercive powers, they must be able to justify their use—not merely under statutory authority but also under actual necessity.

These issues can be resolved through better use of public health law. For states that have not done so recently, it is important that legal authority for measures to control infectious diseases be reviewed to make sure that the law permits the range of evidence-based, appropriate control measures the state may wish to use, which would resolve Maine's potential problem.126,127 Likewise, it is important that decision makers understand both statutory and constitutional limitations on state authority—which would have prevented the potential constitutional problem with Louisiana's policy—and when a public health emergency declaration is needed for the state to legally exercise authority. Each of these will often require early inclusion of states' legal counsel.

Federal Preemption Can Resolve Conflicting Goals

Public health advocates tend to disfavor federal preemption of state public health laws because states often enact more rigorous health and safety protections.130 In areas ranging from injury prevention131 to drug safety132 and menu labeling,133 preemption has been blamed for undermining state public health policies. However, in narrow circumstances when states' public policy goals conflict with federal objectives, preemption may be appropriate. This is particularly the case when the federal government's approach seeks to balance domestic with global public health goals, while states have no incentive to promote global health and, therefore, take steps that may undermine federal efforts to achieve it.

At least one policy—quarantine of in-transit healthcare workers returning from treating Ebola patients in West Africa—conflicted with expressed federal objectives to balance domestic disease prevention with the need to control the epidemic overseas, which the administration believed necessary to prevent the introduction of cases into the United States. Quarantine significantly increases burdens on returning healthcare workers and, therefore, would be expected to cause fewer to volunteer to serve overseas, impeding disease control in West Africa, a point the Obama administration raised several times.33,108 This was doubly true when states sought to quarantine in-transit passengers who had not yet arrived home, which undermined the federal entry screening and control scheme. Had all 5 states with airports that handled travelers returning from Ebola-affected countries adopted New Jersey's approach, federal policy would have been defeated.

In general, Congress has restricted federal authority to preempt state quarantine policies. However, when the Department of Health and Human Services acts under federal quarantine laws,38 it is authorized by Congress to supersede state policies that conflict. In fact, case law dating back to the 19th century recognizes federal authority to create quarantine rules for people entering the United States or moving between states and to preempt state policies when they conflict.39 During the height of the Ebola epidemic in West Africa, the administration could have considered preempting state airport quarantine rules.

Of course, preempting state airport quarantine rules would have raised significant federalism issues and been politically contentious, and it should be used cautiously. Whereas the federal government has historical control over ports of entry, states have long had primary authority for public health. There exist constitutional presumptions that states not be preempted in the use of their historical powers unless the federal government makes its preemptive intent clear.134,135 Similarly, under the federal Public Health Service Act, preemption would have likely required a formal regulatory determination that federal traveler screening and controls were necessary to prevent the “introduction, transmission, or spread” of Ebola and that state approaches conflicted with those objectives.38

Federal preemption of state public health measures should be undertaken cautiously. While the federal government has broader disease control measures during declared public health emergencies136 and when a state fails to adequately control an outbreak that threatens to spread between states,137 these powers can almost always be exercised cooperatively with state governments.69,138 Preemption should be reserved for situations in which state decisions threaten to render federal policymaking ineffective, such as when state policies complicate federal entry screening and subsequent public health measures.

Conclusion

An analysis of international, federal, and state screening and restriction policies for travelers returning from Ebola-affected West African countries finds substantial variation between and within international, federal, and state policies. Some of the variation appears to result from different actors having different public health goals, especially variation in the balance between global and domestic objectives. Other variation, however, appears to result from non–public health goals, which is concerning when coercive public health measures are employed and doubly so when goals are not made transparent for public debate. In order to strengthen responses to future, similar disease emergencies, health authorities should clarify their goals and confirm their legal authority for control measures before emergencies. Finally, in rare instances when state policies threaten to undermine federal public health objectives, the federal government should be cautiously willing to supersede wayward state policies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments and Disclosures

This manuscript was developed with funding support awarded to Harvard School of Public Health under cooperative agreements with the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention grant 5P01TP000307-01 (Preparedness and Emergency Response Research Center). MJS receives research support from the National Institutes of Health (K23 MH09916).

Two authors were subject to Ebola-related restrictions on returning from Liberia in the following jurisdictions: federal (JDK & MJS), District of Columbia (JDK), Florida (MJS), and Massachusetts (MJS). While it is not clear to us that this strictly meets the criteria for a conflict of interest, we believe it may be relevant to readers and have therefore disclosed it.

References

- 1.Siedner MJ, Kraemer JD. The global response to the Ebola fever epidemic: what took so long? PLoS Medicine blog August 22, 2014. http://blogs.plos.org/speakingofmedicine/2014/08/22/global-response-ebola-fever-epidemic-took-long/ Accessed March, 2015

- 2.Siedner MJ, Gostin LO, Cranmer HH, Kraemer JD. Strengthening the detection of and early response to public health emergencies: lessons from the West African Ebola epidemic. PLoS Med 2015;12(3):e1001804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gostin LO, Hodge JG, Burris S. Is the United States prepared for Ebola? JAMA 2014. December 17;312(23):2497-2498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown CM, Aranas AE, Benenson GA, et al. Airport exit and entry screening for Ebola—August-November 10, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2014. December 12;63(49):1163-1167 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harris RL, Brennan E, Clark N. The latest on Ebola and travel. New York Times October 17, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update: CDC Ebola response and interim guidance. Press briefing transcript. October 27, 2014. http://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2014/t1027-ebola-response-interim-guidance.html Accessed March, 2015

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim U.S. guidance for monitoring and movement of persons with potential Ebola virus exposure. Updated May 13, 2015. http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/pdf/monitoring-and-movement.pdf Accessed August13, 2015

- 8.Stehling-Ariza T, Fisher E, Vagi S, et al. Monitoring of persons with risk for exposure to Ebola virus disease—United States, November 3, 2014-March 8, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015. July 3;64(25):685-689 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim Table of State Ebola Screening and Monitoring Policies for Asymptomatic Individuals. 2015. http://www.cdc.gov/phlp/docs/interim-ebolascreening.pdf Accessed March, 2015

- 10.Klaiman T, Kraemer JD, Stoto MA. Variability in school closure decisions in response to 2009 H1N1: a qualitative systems improvement analysis. BMC Public Health 2011. February 1;11:73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seid M, Lotstein D, Williams VL, et al. Quality improvement in public health emergency preparedness. Annu Rev Public Health 2007;28:19-31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lotstein D, Seid M, Ricci K, et al. Using quality improvement methods to improve public health emergency preparedness: PREPARE for pandemic influenza. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008. Sep-Oct;27(5):w328-339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berwick DM. A primer on leading the improvement of systems. BMJ 1996. March 9;312(7031):619-622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stoto MA. The precautionary principle and emerging biological risks: lessons from swine flu and HIV in blood products. Public Health Rep 2002. Nov-Dec;117(6):546-552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stoto M, Dausey D, Davis L, et al. Learning from Experience: The Public Health Response to West Nile Virus, SARS, Monkeypox, and Hepatitis A Outbreaks in the United States. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corp.; 2005. http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/technical_reports/2005/RAND_TR285.pdf Accessed August13, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mabey D, Flasche S, Edmunds WJ. Airport screening for Ebola. BMJ 2014;349:g6202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Read JM, Diggle PJ, Chirombo J, Solomon T, Baylis M. Effectiveness of screening for Ebola at airports. Lancet 2015. January 3;385(9962):23-24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bogoch II, Creatore MI, Cetron MS, et al. Assessment of the potential for international dissemination of Ebola virus via commercial air travel during the 2014 West African outbreak. Lancet 2015. January 3;385(9962):29-35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Poletto C, Gomes MF, Pastore y Piontti A, et al. Assessing the impact of travel restrictions on international spread of the 2014 West African Ebola epidemic. Euro Surveill 2014. October 23;19(42):20936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gostic KM, Kucharski AJ, Lloyd-Smith JO. Effectiveness of traveller screening for emerging pathogens is shaped by epidemiology and natural history of infection. Elife 2015. February 19;4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cowling BJ, Yu H. Ebola: worldwide dissemination risk and response priorities. Lancet 2015. January 3;385(9962):7-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.St John RK, King A, de Jong D, Bodie-Collins M, Squires SG, Tam TW. Border screening for SARS. Emerg Infect Dis 2005. January;11(1):6-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Selvey LA, Antão C, Hall R. Entry screening for infectious diseases in humans. Emerg Infect Dis 2015. February;21(2):197-201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goubar A, Bitar D, Cao WC, Feng D, Fang LQ, Desenclos JC. An approach to estimate the number of SARS cases imported by international air travel. Epidemiol Infect 2009. July;137(7):1019-1031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hollingsworth TD, Ferguson NM, Anderson RM. Will travel restrictions control the international spread of pandemic influenza? Nat Med 2006. May;12(5):497-499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organization. WHO interim guidance for Ebola virus disease: exit screening at airports, ports and land crossings. 2014. http://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/ebola/exit-screening-guidance/en/ Accessed August13, 2015

- 27.World Health Organization. Technical note for Ebola virus disease preparedness planning for entry screening at airports, ports and land crossings. 2014. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/144819/1/WHO_EVD_Guidance_PoE_14.3_eng.pdf?ua=1 Accessed August13, 2015

- 28.World Health Organization. Statement on the 3rd meeting of the IHR Emergency Committee regarding the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa. 2014. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/statements/2014/ebola-3rd-ihr-meeting/en/ Accessed March30, 2015

- 29.World Health Organization. Statement on the 1st meeting of the IHR Emergency Committee on the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa. 2014. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/statements/2014/ebola-20140808/en/ Accessed March30, 2015

- 30.Izadi E. What Texas can learn from Nigeria when it comes to containing Ebola. Washington Post October 4, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ebola in Liberia. Updated July 2, 2015. http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/notices/warning/ebola-liberia Accessed August13, 2015

- 32.Department of State. Liberia travel warning. 2014. https://www.osac.gov/Pages/ContentReportDetails.aspx?cid=16117 Accessed August31, 2015

- 33.Obama B. Remarks by the President on the Ebola Outbreak. 2014. https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2014/09/16/remarks-president-ebola-outbreak Accessed March, 2015

- 34.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Enhanced Ebola screening to start at five U.S. airports and new tracking program for all people entering U.S. from Ebola-affected countries [press release]. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. October 8, 2014. http://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2014/p1008-ebola-screening.html Accessed August17, 2015

- 35.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Fact Sheet: Screening of travelers at airports. October 8, 2014. http://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2014/images/JointAirportScreeningFactSheet.pdf Accessed August17, 2015

- 36.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC issues revised interim U.S. guidance for monitoring and movement of persons with potential Ebola virus exposure [media statement]. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. October 27, 2014. http://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2014/s1027-revised-guidance-monitoring.html Accessed August17, 2015

- 37.Gostin LO. Public Health Law: Power, Duty, Restraint. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Regulations to control communicable diseases, 42 U.S. Code 264 (2002)

- 39.Morgan's Steamship Co. v Board of Health of the State of Louisiana, 118 U.S. 455 (1886)

- 40.Compagnie Francaise v Louisiana, 118 U.S. 380 (1902)

- 41.Gibbons v Ogden, 22 U.S. 1 (1824)

- 42.Virginia Department of Health. Ebola—basic airport screening and active monitoring protocol. Updated January 27, 2015. http://www.vdh.virginia.gov/epidemiology/ebola/BasicAirportProtocol.htm Accessed August17, 2015

- 43.New Jersey Department of Health. New Jersey mandatory quarantine and screening protocols. October 31, 2014. http://www.state.nj.us/health/news/2014/approved/20141031b.html Accessed August17, 2015

- 44.Bankoff C. A lot of people are unhappy about Christie and Cuomo's Ebola-quarantine policy. Daily Intelligencer October 26, 2014. http://nymag.com/daily/intelligencer/2014/10/people-dont-like-ny-and-njs-ebola-policy.html Accessed August17, 2015

- 45.New York State. New York State releases fact sheet on state screening protocols at JFK International Airport. New York State website. October 26, 2014. http://www.governor.ny.gov/news/new-york-state-releases-fact-sheet-state-screening-protocols-jfk-international-airport Accessed August17, 2015

- 46.Kaplan T, Steinhauer J. Cuomo, shifting his policy on outbreak, opens up public rift with de Blasio. New York Times October 24, 2014:A17 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Berman M, Eilperin J. New quarantine rules considered for aid workers returning to U.S. from Ebola-stricken region. Washington Post October 24, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 48.New York State Department of Health. Order for Summary Action in the Matter of the Prevention and Control of Ebola Virus Disease Statewide and Via John F. Kennedy International Airport. October 27, 2014. http://www.health.ny.gov/diseases/communicable/ebola/docs/commissioner_order_2.pdf Accessed August17, 2015

- 49.Flegenheimer M, Shear MD, Barbaro M. Under pressure, Cuomo says Ebola quarantines can be spent at home. New York Times October 26, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rushe D, Gambino L, Roberts D. White House warns Cuomo and Christie over Ebola quarantine rules. Guardian (London) October 27, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 51.District of Columbia Department of Health. Disclosure of patient contact and voluntary isolation in lieu of forced quarantine agreement. Undated. http://doh.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/doh/page_content/attachments/EBOLA%20-%20PATIENT%20CONTACT%20AGREEMENT%202014%2011-20.pdf Accessed August17, 2015

- 52.Florida Department of Health. Guidance for 21-day county health department monitoring of travelers from countries currently experiencing an outbreak of Ebola virus disease. November 18, 2014. http://www.floridahealth.gov/diseases-and-conditions/ebola/_documents/ebola-guidance-monitoring-travelers-full.pdf Accessed February15, 2015

- 53.Iowa Department of Public Health. Ebola-related health orders: what do they mean? Undated. http://www.idph.state.ia.us/IDPHChannelsService/file.ashx?file=A9B0EBCE-5D19-4EBE-9B79-AEDCE005D67F Accessed August17, 2015

- 54.Iowa Department of Public Health. Partner Briefing: information provided on 12-15-14. http://www.idph.state.ia.us/IDPHChannelsService/file.ashx?file=CA03D283-382F-4C64-8879-04578984DE1B Accessed February20, 2015

- 55.Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Ebola protocol for travelers from Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea. October 27, 2014. http://www.maine.gov/dhhs/mecdc/infectious-disease/epi/zoonotic/ebola/documents/Maine-Ebola-Protocols-October-27.pdf Accessed August17, 2015

- 56.Edwards S. Maine CDC & DHHS clarifies state's Ebola policies. WLBZ October 28, 2014. http://www.wcsh6.com/story/news/health/2014/10/28/maine-cdc-dhhs-ebola-policies/18078435/ Accessed August17, 2015

- 57.New York State Department of Health. Screening operations at JFK International Airport. October 29, 2014. http://www.health.ny.gov/diseases/communicable/ebola/docs/screening_protocol_jfk.pdf Accessed March15, 2015

- 58.Ohio Department of Health. Ohio releases new, stronger health monitoring and quarantine protocols for travelers returning from West Africa [news release]. October 31, 2014. http://www.odh.ohio.gov/∼/media/ODH/ASSETS/Files/ebola/news%202/Strengthened%20Ohio%20Health%20Monitoring-Quarantine%20Protocols.ashx Accessed March15, 2015

- 59.Ohio Department of Health. ODH crosswalk for Ebola exposure and risk intervention. October 31, 2014. http://www.odh.ohio.gov/∼/media/ODH/ASSETS/Files/ebola/Strengthened%20Traveler%20Protocols.ashx Accessed August17, 2015

- 60.Kansas Department of Health and Environment. Ebola virus preparedness and response plan. October 29, 2014. http://www.kdheks.gov/ebola/download/KDHE_Ebola_Preparedness_Plan.pdf Accessed August17, 2015

- 61.New Hampshire Division of Public Health Services. Interim policy summary for isolation of suspect Ebola patients and quarantine of persons potentially-exposed to Ebola virus. November 10, 2014. http://www.dhhs.nh.gov/dphs/cdcs/ebola/documents/isolationquarantine-interim.pdf Accessed August17, 2015

- 62.Maine District Court. Order Pending Hearing in Mayhew v Hickox. CV-2014-36 (2014)

- 63.Maine District Court. Order in Mayhew v Hickox. CV-2014-36 (2014)

- 64.Duties of the Department for Disease Investigation and Intervention. 10-144 Code of Maine Rules Chapter 258, Sec. 9 (2008)

- 65.Control of Communicable Diseases and Conditions: Definitions. 22 Maine Revised Statutes 801 (2008)

- 66.Control of Communicable Diseases and Conditions: Public Health Measures. 22 Maine Revised Statutes 812 (2012)

- 67.Control of Communicable Diseases and Conditions: Authority of Department. 22 Maine Revised Statutes 802 (2012)

- 68.Extreme Public Health Emergency. 22 Maine Revised Statutes 820 (2005)

- 69.Hodge JG. Legal myths of Ebola preparedness and response. Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy 2015;29:355-549 [Google Scholar]

- 70.Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals. Ebola hemorrhagic fever, Ebola virus disease (EVD). December 1, 2014. http://new.dhh.louisiana.gov/assets/oph/Center-PHCH/Center-CH/infectious-epi/EpiManual/EbolaManual.pdf Accessed August17, 2015

- 71.Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals. Communication to ASTMH Annual Meeting Attendees. October 28, 2014. http://sherwood-astmh.informz.net/InformzDataService/OnlineVersion/Public?mailingInstanceId=4362069 Accessed March10, 2015

- 72.Enserink M. Been to an Ebola-affected country? Stay away from tropical medicine meeting, Louisiana says. Science October 29, 2014. http://news.sciencemag.org/health/2014/10/been-ebola-affected-country-stay-away-tropical-medicine-meeting-louisiana-says Accessed March15, 2015

- 73.Office of the Governor of the State of Connecticut. Gov. Malloy outlines state's policies for monitoring travelers from Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone [press release]. October 27, 2014. http://portal.ct.gov/Gov-Malloy-Outlines-State-s-Policies-for-Monitoring-Travelers-from-Guinea-Liberia-and-Sierra-Leone/ Accessed June30, 2015

- 74.Office of the Governor of the State of Connecticut. Declaration of Public Health Emergency. October 7, 2014

- 75.Connecticut governor declares state of emergency over Ebola as a precaution. New England Cable News October 7, 2014. http://www.necn.com/news/new-england/Connecticut-Governor-Declares-State-of-Emergency-Over-Ebola-as-a-Precaution-278380851.html Accessed June20, 2015

- 76.Mueller B. Connecticut tries to find middle path on Ebola. New York Times October 29, 2014:A12 [Google Scholar]

- 77.Orders of Quarantine or Isolation of Certain Persons. Connecticut General Statutes Annotated 19a-221 (2003)

- 78.Orders of Quarantine or Isolation. Connecticut General Statutes Annotated 19a-131b (2003)

- 79.Megan K. Student doubts Ebola policy after return to Yale from Africa, held in isolation quarantine. Hartford Courant October 28, 2014:A3 [Google Scholar]

- 80.Texas Task Force on Infectious Disease Preparedness and Response. Guidelines for the monitoring of health care workers and others returning to Texas from Ebola-endemic areas in West Africa. October 31, 2014. http://gov.texas.gov/files/press-office/2014-10-31-TX-Task_Force_Recommendations.pdf Accessed March15, 2015

- 81.Texas Department of State Health Services. Guidance: monitoring and movement of people with potential exposure to Ebola virus disease. November 7, 2014. http://www.texasebola.org/pdfs/1505-Monitoring-Movement.pdf Accessed March10, 2015

- 82.New Mexico Department of Health. Ebola virus disease response plan. February 27, 2015. http://nmhealth.org/publication/view/plan/953/ Accessed August17, 2015

- 83.Indiana State Department of Health. Outpatient clinic Ebola guidelines. Undated. http://www.in.gov/isdh/files/Outpatient_Ebola_Guidelines_11_20_14.pdf Accessed March10, 2015

- 84.Smith J. Officials monitoring Indiana travelers for Ebola symptoms. WISHTV.com October 30, 2014. http://wishtv.com/2014/10/30/officials-monitoring-indiana-travelers-for-ebola-symptoms/ Accessed March10, 2015

- 85.Stoto M. Measuring and assessing public health emergency preparedness. J Public Health Manag Pract 2013. Sep-Oct;19(Suppl 2):S16-S21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Stoto MA, Nelson C, Higdon MA, Kraemer J, Hites L, Singleton CM. Lessons about the state and local public health system response to the 2009 H1N1 pandemic: a workshop summary. J Public Health Manag Pract 2013. Sep-Oct;19(5):428-435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gomes MF, Pastore Y Piontti A, Rossi L, et al. Assessing the international spreading risk associated with the 2014 West African Ebola outbreak. PLoS Curr 2014. September 2;6:10.1371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ely JH. Democracy and Distrust: A Theory of Judicial Review. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1980 [Google Scholar]

- 89.Boren Craig v, 429 U.S. 190 (1976)

- 90.Cleburne v Cleburne Living Center, Inc., 420 U.S. 432 (1985)

- 91.World Health Organization. International Health Regulations (2005). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 92.Fidler DP. From international sanitary conventions to global health security: the new International Health Regulations. Chinese Journal of International Law 2005. November 01;4(2):325-392 [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hoffman SJ, Rottingen JA. Assessing the expected impact of global health treaties: evidence from 90 quantitative evaluations. Am J Public Health 2015. January;105(1):26-40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wilson K, Brownstein JS, Fidler DP. Strengthening the International Health Regulations: lessons from the H1N1 pandemic. Health Policy Plan 2010;25(6):505-509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.World Health Organization. Statement on the 2nd meeting of the IHR Emergency Committee regarding the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa. September 22, 2014. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/statements/2014/ebola-2nd-ihr-meeting/en/ Accessed March10, 2015

- 96.World Health Organization. Statement on the 4th meeting of the IHR Emergency Committee regarding the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa. January 21, 2015. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/statements/2015/ebola-4th-ihr-meeting/en/ Accessed March10, 2015

- 97.Mano River Union. Joint declaration of heads of state and government of the Mano River Union for the eradication of Ebola in West Africa. August 1, 2014. http://www.manoriverunion.int/JOINT%20DECLARATION%20FINAL%20VERSION.pdf Accessed March10, 2014

- 98.Gladstone R. Liberian leader concedes errors in response to Ebola. New York Times March 11, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 99.Khan K, Eckhardt R, Brownstein JS, et al. Entry and exit screening of airline travellers during the A(H1N1) 2009 pandemic: a retrospective evaluation. Bull World Health Organ 2013. May 1;91(5):368-376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Embassy of the United States in Monrovia, Liberia. The United States increases its assistance for anti-Ebola efforts in West Africa. August 19, 2014. http://monrovia.usembassy.gov/event_dart_91914.html Accessed March10, 2015

- 101.Embassy of the United States in Monrovia, Liberia. U.S.-Liberia relationship [press release]. 2015. http://monrovia.usembassy.gov/pr_uslib_030315.html Accessed March30, 2015

- 102.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Telebriefing: CDC update on first Ebola case diagnosed in the United States, 10-08-2014 [press briefing transcript]. October 8, 2014. http://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2014/t1008-ebola-confirmed-case.html Accessed March15, 2015

- 103.Muskal M. Four Ebola quotes that may come back to haunt CDC's Tom Frieden. Los Angeles Times October 16, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 104.Weisman J. On Ebola response, congressional Republicans put new focus on visa suspensions. New York Times October 20, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 105.Dausey D. Epidemiologist: stop the flights now. Washington Post October 6, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 106.Chertoff M. The case for suspending U.S. visas in Ebola-affected countries. Washington Post October 26, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 107.Boghani P, Molloy T. Representatives push for travel ban at Ebola hearing. Frontline October 16, 2014. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/health-science-technology/ebola-outbreak/congress-holds-ebola-hearing-there-is-no-room-for-error-livestream/ Accessed March10, 2015

- 108.Frieden T. CDC Chief: why I don't support a travel ban to combat Ebola outbreak. FoxNews.com October 9, 2014. http://www.foxnews.com/opinion/2014/10/09/cdc-chief-why-dont-support-travel-ban-to-combat-ebola-outbreak/ Accessed March10, 2015

- 109.Morrison JS. Thomas Frieden and the U.S. Ebola response. Health Affairs Blog October 20, 2014. http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2014/10/20/thomas-frieden-and-the-u-s-ebola-response/ Accessed March10, 2015

- 110.Bilder RB. The role of states and cities in foreign relations. Am J Int Law 1989;83:821-831 [Google Scholar]

- 111.Engel K. State and local climate change initiatives: what is motivating state and local governments to address a global problem and what does this say about federalism and environmental law? Urb Law 2006;38:1015-1030 [Google Scholar]

- 112.Zernike K, Kaplan T. Two governors' shifts on Ebola are criticized as politics, not science. New York Times October 28, 2014:A13 [Google Scholar]

- 113.New York State. Video: Governor Andrew Cuomo and Governor Chris Christie announce additional screening protocols for Ebola at JFK and Newark Liberty International Airports. October 24, 2014. http://www.governor.ny.gov/news/governor-andrew-cuomo-and-governor-chris-christie-announce-additional-screening-protocols-ebola Accessed March10, 2015

- 114.Office of the Governor of the State of New Jersey. Governor Christie: We need leadership, not 7 minute lectures. October 29, 2014. http://nj.gov/governor/news/news/552014/approved/20141029e.html Accessed March10, 2015

- 115.Dugan A. One-fifth of Americans worry about getting Ebola. Gallup website. October 7, 2014. http://www.gallup.com/poll/178097/one-fifth-americans-worry-getting-ebola.aspx Accessed June15, 2015

- 116.Slovic P. Perception of risk. Science 1987. April 17;236(4799):280-285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Osterholm MT. What we're afraid to say about Ebola. New York Times September 11, 2014:A31 [Google Scholar]

- 118.Cohen E. Ebola in the air? A nightmare that could happen. CNN October 6, 2014. http://www.cnn.com/2014/09/12/health/ebola-airborne/ Accessed June15, 2015

- 119.Dwyer D. Should we worry about Ebola becoming airborne? Washington Post October 9, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 120.Larimer S. Will the Ebola virus go airborne? (And is that even the right question?) Washington Post September 15, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 121.Kraemer JD, Cabrera OA, Singh JA, Depp TB, Gostin LO. Public health measures to control tuberculosis in low-income countries: ethics and human rights considerations. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2011. June;15(Suppl 2):S19-S24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Gostin L, Mann JM. Towards the development of a human rights impact assessment for the formulation and evaluation of public health policies. Health Hum Rights 1994. Fall;1(1):58-80 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Richardson HS. Democratic Autonomy: Public Reasoning About the Ends of Policy. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 124.Gutmann A, Thompson D. Why Deliberative Democracy? Princeton: Princeton University Press; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 125.Goldberg DS. Against the very idea of the politicization of public health policy. Am J Public Health 2012;102(1):44-49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Gostin LO. Public health law reform. Am J Public Health 2001;91(9):1365-1368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Hall MA. The scope and limits of public health law. Perspect Biol Med 2003;46(3 Suppl):S199-S209 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Disease Control Measures including Isolation/Quarantine. Louisiana Administrative Code, Title 51, Part II, Section 117 (2009)

- 129.Mariner WK, Annas GJ, Glantz LH. Jacobson v Massachusetts: it's not your great-great-grandfather's public health law. Am J Public Health 2005;95(4):581-590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Pertschuk M, Pomeranz JL, Aoki JR, Larkin MA, Paloma M. Assessing the impact of federal and state preemption in public health: a framework for decision makers. J Public Health Manag Pract 2013;19(3):213-219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Vernick JS. The role of federal preemption in injury prevention litigation. J Law Med Ethics 2011;39(Suppl 1):85-88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Burke T. Colacicco v Apotex Inc. and the federal preemption of state tort remedies for health injuries: implications for public health policy and practice. Public Health Rep 2009;124(1):160-163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Pomeranz JL, Teret SP, Sugarman SD, Rutkow L, Brownell KD. Innovative legal approaches to address obesity. Milbank Q 2009;87(1):185-213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Arizona v Inter Tribal Council of Arizona, 133 S. Ct. 2247 (2013)

- 135.Rice v Santa Fe Elevator Corp, 331 U.S. 218 (1947)

- 136.Public Health Emergencies. 42 U.S. Code 247d (2013)

- 137.Measures in the Event of Inadequate Local Control. 42 Code of Federal Regulations 70.2 (2005)

- 138.Hodge JG, Anderson ED. Principles and practice of legal triage during public health emergencies. NYU Ann Surv Am L 2008;64:249 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.