Abstract

Objective

This article describes Phase 1 of a pilot that aims to develop, implement, and test an intervention to educate and simultaneously engage highly stressed Latino parents in child mental health services. A team of Spanish-speaking academic and community co-investigators developed the intervention using a community-based participatory research approach and qualitative methods.

Method

Through focus groups, the team identified parents' knowledge gaps and their health communication preferences.

Results

Latino parents from urban communities need and welcome child mental health literacy interventions that integrate printed materials with videos, preferably in their native language, combined with guidance from professionals.

Conclusion

A 3-minute video in Spanish that integrates education entertainment strategies and a culturally relevant format was produced as part of the intervention to educate and simultaneously engage highly stressed Latino parents in child mental health care. It is anticipated that the intervention will positively impact service use among this group.

Keywords: Hispanic Latino parents, mental health literacy, highly stressed families, collaborative video production

Introduction

Today about 57 million of the total U.S. population is of Latino origin and, within this group, about 26% live below the poverty level (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010). Poor Latinos are more likely to report language barriers and are more likely to live in linguistically isolated households than Latinos with annual incomes higher than US$20,000 (Falcón, 2010; Pew Hispanic Center, 2013). Language barriers prevent active integration and meaningful participation in community activities and civic life and impact access to information and to services in general (Pew Hispanic Center, 2013). Low English proficiency (LEP) in children is closely linked to family poverty, and Latino children comprise the largest group of children with LEP in the country (Batalova, 2006; Falcón, 2010).

Researchers have already established a link between urban poverty and child mental health issues (McKay & Bannon, 2004; McKay et al., 2010) thus LEP Latino urban poor children and their families living with income insecurity, like other highly stressed urban poor families, are at higher risk of developing mental health problems (Wadsworth & Santiago, 2008). However, Latinos in general and Latino children in particular tend to underutilize mental health services or significantly delay entry into care (Alegria et al., 2004; Cabassa, Molina, & Baron, 2012; Gelman, 2010; Guarnaccia, Martinez, & Acosta, 2005). Linguistic isolation among LEP Latinos may contribute to the disparity between their service use and their needs.

It has been established that poverty is a barrier to entering mental health services overall (National Alliance on Mental Illness, 2006). Three specific types of poverty-related stress have a heightened impact on urban poor Latinos: (1) parenting stress, (2) parents' financial stress, and (3) family conflict (Callejas, Hernandez, Nesman, & Mowery, 2010; Falcón, 2010; Santiago & Wadsworth, 2011). These specific types of poverty-related stress might impact access to care for urban poor Latino families. Financial stress among Latinos may be explained by two factors: one, that Latinos are a relatively young group when compared to other ethnic groups, with less time to establish financial security following immigration to the United States (Enchautegui, 1997; Landale, Oropesa, & Bradatan, 2006) and the other could be the prevalence of female-headed households among this group (Landale et al., 2006; Mason, Salas, & Ebanks, 2013). In recent years, Latinas experienced the largest increase in poverty across ethnic groups (National Women's Law Center, 2011), a trend that may affect income-insecurity among Latino urban poor residents and may explain the overrepresentation of Latino youths among impoverished children (Santiago & Wadsworth, 2011; Snyder, McLaughlin, & Findeis, 2006). Latino urban poor children in income insecure households may be impacted by the family conflicts that prevail among highly stressed families who are at increased risk of developing mental health problems (Santiago & Wadsworth, 2011).

Compounding the impact of poverty-related stress on mental health service use disparities among urban Latino children is the combination of linguistic barriers, lack of knowledge about services, and the lack of culturally and linguistically congruent services in many communities. Even when services are available, the complex delivery systems in which these services are provided exacerbate the difficulties adults and children of Latino origin experience as they contemplate entering into care (Alegria et al., 2004; Alegria et al., 2012; Cabassa, Contreras, Aragon, Molina, & Baron, 2011; Cabassa et al., 2012; Callejas et al., 2010; Guarnaccia et al., 2005; Hamilton, Marshall, Rummens, Fenta, & Simich, 2011; McKay et al., 2010). To address gaps in knowledge about the benefits of entering into care, health and mental health literacy interventions for Latinos have been developed, tested, and documented in the literature (Barrio & Yamada, 2010; Borrayo, 2004; Cabassa et al., 2011, 2012; Valle, Yamada, & Matiella, 2006).

The concept of mental health literacy has emerged in the literature over the last 15 years and is defined as knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders, which aid their recognition, management, or prevention (Jorm et al., 1997; Jorm & Wright, 2008; Lauber, Nordt, Falcato, & Rossler, 2003). Mental health literacy has received attention in terms of reducing stigma, promoting resiliency, and providing education about mental health and mental illness among youth and their families. To maximize uptake of mental health literacy interventions, Bagnell and Santor (2012) recommend an integrated approach, rather than a stand-alone education opportunity, and suggest that programs for families include interaction, self-direction, and reflection.

Collaborating closely with family members, community residents, consumers and service providers as co-investigators in the development, production, and testing of culturally congruent interventions is an established and growing trend within the fields of health education and child mental health services research (Abdou et al., 2010; Alvidrez, Snowden, & Kaiser, 2010; Borrayo, 2004; Cabassa et al., 2012; Chavez et al., 2004; Hohmann & Shear, 2002; McKay & Bannon, 2004; McKay et al., 2004, 2010; Valle et al., 2006), as is the use of health education videos (Gagliano, 1988), and of videos infused with entertainment-education (EE) strategies (Borrayo, 2004; Sood, 2002; Sood & Storey, 2013). Most recently, health education tools, such as videos and printed materials, infused with EE strategies have been used to meet the health education needs of low literacy Latinos in the United States (Borrayo, 2004; Cabassa et al., 2012; Valle et al., 2006).

EE strategies, initially developed, implemented, and tested in public health programs during the late 1970s in Mexico City (Sabido, 2002), have been found to productively impact the delivery of public health messages to wide audiences across cultures in different languages (Rogers & Shefner-Rogers, 1994; Ryerson, 1994; Singhal & Rogers, 1999, 2002). EE strategies have been successfully used to disseminate public health messages within Africa, Asia, and other Latin American countries over several decades (Rogers & Shefner-Rogers, 1994; Ryerson, 1994; Singhal & Rogers, 1999; Sood, 2002; Sood & Storey, 2013). These have been highly effective with low literacy audiences who feel empowered to initiate changes in their own lives through identification with the characters and their situations (Bhana et al., 2013; Sood, 2002; Sood, Boulay, & Storey, 2002; Sood & Storey, 2013). Researchers have used EE strategies in culturally and linguistically sensitive ways to address knowledge gaps regarding health and mental health with U.S. Latinos. For example, to educate and motivate Latinas to engage in breast cancer screenings, Borrayo (2004) created an 8-minute video using an entertainment education soap opera format. Cabassa et al. (2012) created a fotonovela to educate Latinos about depression and Valle et al. (2006) created one to educate Latinos about dementia and mental health issues in aging. However, to date, few programs or interventions have been designed to educate and to simultaneously engage urban poor Latino parents with low levels of education, LEP, and low literacy levels in child mental health services (Callejas et al., 2010; Callejas, Nesman, Mowery, & Hernandez, 2008).

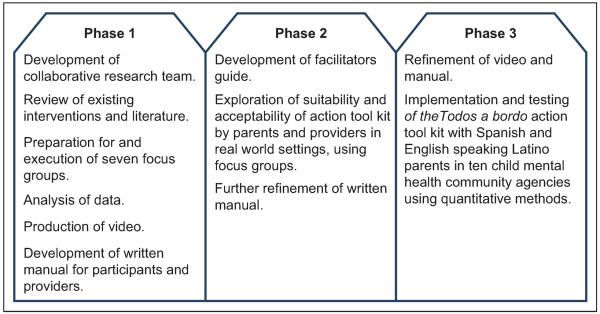

To meet this gap in service, this study used a community-based participatory framework to develop and to explore the feasibility and acceptability of a collaboratively produced child mental health literacy engagement action tool kit. (See Figure 1 regarding the three-phase pilot study.) The action tool kit educates and simultaneously engages Latino parents and/or caregivers from poor urban communities in child mental health services. One part of the tool kit is a child mental health literacy Spanish-language video with English subtitles, tailored to resonate with the experiences of highly stressed Latino families from poverty-impacted communities.

Figure 1.

Todos a bordo/All Aboard. This figure illustrates the three phases of the pilot study.

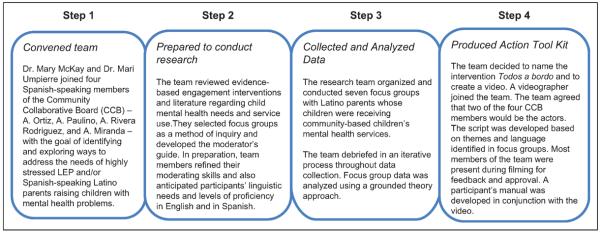

Integrating a Spanish-language video into child mental health service education and engagement is an innovative strategy that we anticipate will positively impact child mental health service utilization among highly stressed Latino parents from urban poor communities. This article focuses on the activities within Phase 1 of the study that led to the collaborative video production (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Phase 1: The collaborative development of the mental health literacy action toolkit for engaging and sustaining Latino parents in service.

Convening a Research Team to Address the Needs of Urban Poor Latino Parents

This research project is grounded in the extensive collaborative work of Dr. Mary M. McKay and the Community Collaborative Board (CCB) (Bannon, Cavaleri, Rodriguez, & McKay, 2008a; Baptiste et al., 2005; McKay & Bannon, 2004; McKay et al., 2014; McKay et al., 2011; McKay et al., 2004, 2010; Paikoff, Traube, & McKay, 2007). The CCB is an active group of parents, youth, school staff, and researchers who have worked together since 1999 in the collaborative design, implementation, and testing of evidence-based intervention research studies and are familiar with conducting all aspects of collaborative research (see McKay et al., 2010; Messam, McKay, Kalonerogiannis, Alicea, & HOPE Committee CHAMP Collaborative Board, 2010, for complete descriptions). This pilot's bilingual/bicultural lead coinvestigator, Dr. Mari Umpierre, joined four Spanish-speaking members of the CCB who wanted to explore how to better serve highly stressed, urban poor, low literacy Latino populations living in their communities.

Collaborative Review of Existing Literature and Interventions

The research team reviewed existing interventions and strategies to engage Latinos in health and mental health literacy efforts (Borrayo, 2004; Cabassa et al., 2012; Valle et al., 2006) and interventions to engage urban parents in mental health services (Kerkorian, McKay, & Bannon, 2006), including the work conducted by the CCB with urban minority families (Bannon, Cavaleri, Rodriguez, & McKay, 2008b; Bannon, McKay, Chacko, Rodriguez, & Cavaleri, 2009; Harrison, McKay, & Bannon, 2004; McBride et al., 2007; McKay et al., 2010; McKay, Harrison, Gonzales, Kim, & Quintana, 2002; Pinto et al., 2007; Sperber et al., 2008).

The literature confirmed that although Latinos are a diverse group, they share common behavior codes and similar values (Borrayo, 2004; Cabassa et al., 2011, 2012; Callejas et al., 2010; Mendez & Westerberg, 2012; Valle et al., 2006) and benefit from informal approaches when addressing serious topics, such as stigma and building trust with mental health providers (Borrayo, 2004). Furthermore, the team reviewed interventions that engage Latino parents in care, specifically “Creating a Front Porch: Strategies for Improving Access to Mental Health Services” (Callejas et al., 2008), which provided detailed information that subsequently informed all steps of the intervention's development.

Preliminary Data

A preliminary, unfunded pilot study was conducted at a large urban academic medical center's outpatient child mental health clinic to examine issues related to highly stressed Latino families' thoughts about referral for child mental health care. A focus group was organized with nine adult caregivers of children presenting with conduct difficulties. Themes identified in this preliminary group in relation to service utilization were (1) school was a source of tension for adult caregivers whose children evidenced conduct problems; (2) school staff were perceived as being blaming of parents—and parents wondered if they were responsible—yo me pregunto si la culpa fue mia; (3) child mental health referrals caused tension for adult caregivers; (4) family privacy was critical—la privacidad familiar es importante—thus dealing with personal issues within a clinic setting could be uncomfortable; and (5) it was shameful to have a problem—es vergonzoso tener un problema. With these themes in mind, the team moved forward in Phase 1 of the pilot.

Method

Focus Groups

In focus groups, participants collectively generate ideas through interaction, exploration, and discussions, a process that uncovers material not accessible through traditional individual interviews or surveys (Carey & Asbury, 2012; Halcomb & Andrew, 2005; Morgan & Krueger, 1993); thus, the research team selected the use of focus groups as the method of inquiry (Halcomb, Gholizadeh, DiGiacomo, Phillips, & Davidson, 2007). The team aimed to explore the lived experiences of poor Latino parents raising children in poverty-impacted environments and what types of health communication methods would be most acceptable to them, specifically the feasibility and acceptability of coproducing a video intervention (Chavez et al., 2004).

The research team established a list of priorities regarding the nature and scope of the information to be collected in order to maximize the utility of the data and used these priorities to guide the development of a moderator's guide in Spanish and English. The moderator's guide was designed to open discussion about the parents' general beliefs and attitudes regarding their children's mental health and their impressions and beliefs about child mental health issues, both in the United States and in their home countries. The focus group questions explored urban Latino parents' (1) “trusted advisors” with child-rearing practices and problems, (2) preferred methods for obtaining information about child health and mental health, and in this way, explore the feasibility and acceptability of a video intervention, (3) methods of seeking information about health and mental health, and whether they accessed the Internet to seek information about health, (4) pathways into care, (5) language used to describe children's mental health issues, and last (6) recommendations to better serve other Latino parents in child mental health service settings. It was anticipated that engaging parents in a focused conversation, in their preferred language or languages, within a safe environment and in an atmosphere of respectful curiosity, would yield rich and detailed information.

In preparation for data collection, the collaborative research team met regularly to carefully craft the moderator's guide and include relevant probes. Moderators were keenly aware of the importance of interactions and discussions in focus groups (Carey & Asbury, 2012; Halcomb et al., 2007; Krueger, 2006) and since linguistic behaviors vary among Latino groups (Callejas et al., 2010), they prepared to be extremely attentive to language issues during the sessions. The team worked together to refine each member's moderating skills and audio recorded mock sessions that were later reviewed for quality control purposes.

The moderators kept several important issues in mind: (1) to repeat questions and probes in English and in Spanish, (2) to make sure that all group participants understood each other as well as the moderators, (3) if in doubt, to translate comments between languages, (4) to listen for linguistic variations between Latinos of different national origins, and (5) to listen for the use of “Spanglish terms” and make sure these were understood by the group. “Spanglish” is defined by the Oxford Dictionary (Spanglish, n.d.), as a hybrid language combining words and idioms from both Spanish and English, especially Spanish speech that uses many English words and expressions. While community members recognize it as the unofficial language of everyday life in urban poor Latino communities, non-English-speaking, recent Latino immigrants are often unfamiliar with its use. In sum, the research team thoroughly prepared to address the linguistic needs of the group participants so as to capture as much variation in language use as possible.

Focus Group Participants

Bilingual and Spanish-speaking Latino parents and adult caregivers with significant responsibility raising a child referred to mental health services due to behavioral difficulties or externalizing disorders were invited to participate in seven focus groups. Six of these groups were conducted at the outpatient child psychiatry clinic of a large urban medical center located on the border of one of the poorest communities in the Northeast, and one focus group was conducted at a community mental health clinic also located in an urban poor community within the same city in a similar neighborhood. Clinical staff with previous training in recruiting adult caregivers into research participation assisted with organizing the focus groups at these settings.

In total, 36 Latino parents and caregivers primarily foreign-born, Spanish speaking and female (see Table 1), and residing in urban poor communities participated. Each participant received US$40.00 to compensate his or her time. Child care was provided during sessions; participants were served lunch, dinner, or refreshments; and their children joined the adults for meals and refreshments.

Table 1.

Focus Group Participant Demographics.

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Total Number of Participants | 36 | 100 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 31 | 86 |

| Male | 6 | 14 |

| Caregiver | ||

| Parent | 32 | 88.9 |

| Grandparent | 3 | 8.3 |

| Foster parent/adoptive parent | 1 | 2.8 |

| Country of origin | ||

| Foreign-born | 23 | 63.9 |

| Puerto Rico | 4 | |

| Dominican Republic | 11 | |

| Mexico | 8 | |

| U.S.-born, Latino descendent | 13 | 36.1 |

| Puerto Rican | 12 | |

| Dominican | 1 | |

| Language preference | ||

| Spanish dominant | 23 | 63.9 |

| English dominant (Spanglish) | 13 | 36.1 |

Source. Focus group participants, 2011.

Data Analysis

Each group met for about 90 minutes, and all sessions were conducted in a combination of English and Spanish, integrating “Spanglish” terms as anticipated. Collaborative team members were involved in all steps of the data collection and analysis. Focus group data were captured through digital audio recordings and extensive field notes. During a debriefing after each focus group, moderators noted the mood, the energy, and the enthusiasm of the members, following Krueger's (2006) recommendations. Between sessions, the collaborative team met regularly to go over the audio recordings, compare field notes, and refine probes as needed. Research partners listened to tapes of themselves conducting the focus groups in order to improve their moderating skills as well as to begin identifying salient themes of the formative research.

A grounded theory approach (Glaser & Strauss, 1967) was used to analyze the focus group data. Data were coded and analyzed using a modification of the system developed by Morgan and Krueger (1993) and guided by the work of Carey and Asbury (2012), Krueger (2006), and Halcomb, Gholizadeh, DiGiacomo, Phillips, and Davidson (2007).

The team members identified themes by reading field notes, listening to tapes, and discussing the relevance of the material to address the research questions. The analytic coding categories were used to organize initial data. A list of themes and concepts from across groups was compiled and used to further refine the focus group questions and the probes used by the focus group moderators, jump-starting conversations within the research partnership and within the focus groups. Similarities, differences, and potential connections between sessions were identified by the research team and informed subsequent data collection and analysis.

Each 1½-hour focus group and its field notes resulted in comprehensive five- to six-page summaries that featured direct quotations of the focus groups (Carey & Asbury, 2012; Halcomb et al., 2007; Krueger, 2006). Sessions were read through and listened to several times both during team meetings and by each member individually. Following a process of repeated listening and note taking (Sealy et al., 2012), team members shared and reviewed their notes. The session notes were recoded with the study aims in mind. Themes and subthemes were developed and carefully discussed among the team until all members agreed. A list of themes and codes was compiled and used as an organizational framework for subsequent analysis. These themes were compared across groups. A descriptive summary or grid was developed to represent the key content of each focus group (Halcomb et al., 2007). Text transcribed verbatim was used to illustrate the themes and codes. Data triangulation was achieved dividing the team into subgroups of two coders each. Within each dyad, only one of the coders was present during the focus groups. Session field notes were read and reviewed by two coders, and all team members met to discuss all recordings and transcripts.

Krueger (2006) and Sealy et al., (2012) emphasize that within focus group research carefully understanding the discussions and noting what was relevant to participants is of great importance. Krueger (2006) reports that though at times the most critical findings in focus groups are mentioned only once, their relevance and importance is noted because of the conversational context. Thus, the research team spent considerable time listening to the audio recordings of the focus groups and comparing field notes.

Results

Focus group data helped to uncover Latino parents' lived experiences, challenges, personal stories, and day-to-day struggles, as well as their knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes regarding child mental health in general and child mental health services' utilization. Parenting stress, financial stress, and family conflicts—three common themes present in the participants' narratives across the seven focus groups—are also documented in the literature as poverty related stressors within highly stressed Latino families (Callejas et al., 2008, 2010; Santiago & Wadsworth, 2011). In the following paragraphs, we report findings and integrate relevant quotes from the focus group transcripts, elucidating several links between poverty-related stressors and Latino parents' involvement in mental health services.

Rearing Children Within Multistressed Families

In one focus group, a mother born and raised in the Dominican Republic described the complexities of raising her children in unsafe neighborhoods under severe economic stress within culturally incongruent contexts. She stated the following:

Yo soy madre soltera, me levanto a las cinco de la mañana y vivo con mucho estrés pero yo prefiero sacrificarme y recoger a mi hijo todos los días en la escuela. Él se distrae, tiene déficit de atención y se podría buscar problemas. Mire, yo he escuchado a otras madres hablar de que hay adolescentes que han sido matados frente a sus amigos. Esto es muy estresante pero yo vivo pendiente de mi hijo. (I am a single mother, I get up at 5:00 AM, and I live with a lot of stress, but I prefer to sacrifice myself, and to pick up my son every day from school. He gets easily distracted, he has attention deficit, and he could get into trouble. Look, I have heard about teens getting killed in front of their friends. It's very stressful but my life revolves around my son.)

Another mother, also from the Dominican Republic, stated that:

A míme criaron diferente, en esta cultura es difícil, los niños son menos respetuosos, se creen que ellos son los que mandan, no siguen las reglas del hogar … Yo no contradecía a mis padres. Aquí es donde viene el conflicto. En la Republica Dominicana todos nos criamos de la misma manera, aquícada cual cría a sus hijos a su propia manera. Los niños ven que hay diferencias y se agarran de eso para contradecir a uno. (I was raised in a different way, in this culture it is difficult, children are less respectful, and they think that they are in charge, they do not follow the rules in the home … I did not contradict my parents. This is a source of conflict. In the Dominican Republic we were all raised the same way, here, each person raises children their way. Children notice these differences and they use this to contradict parents.)

The previous comment generated a strong reaction of agreement among participants. During all focus group meetings, a portion of the session was devoted to the exchange of ideas about the challenges of raising children in the United States, as opposed to what it would have been like to raise their children in their own countries. Across groups, participants perceived parents in the United States as more permissive and more tolerant of arguments, of disrespect, and of disobedience from their children than parents in Latin America. In addition, there was agreement with the impression that children in the United States are expected and allowed to be more argumentative, to disagree, and to contradict authority figures. Furthermore, focus group participants also believed that Latino children growing up in the United States adopt the behaviors of their peers, that is, they become argumentative, disrespectful, and disobedient, and that these behaviors lead to friction and stress within families.

Terms Used to Describe Child Mental Health Issues

Focus group participants across groups replied to questions and probes about the words used to describe children's mental health problems with notable similarities. The words crazy and craziness or loco and locura were mentioned in all groups, and the participants agreed that these terms are pejorative, demeaning, and devaluing. Despite this, these terms are in frequent use. A Puerto Rican father said, “La palabra [loco] se presta a diferentes interpretaciones, alguien que tira piedras, uno sin decisión propia” (The word [crazy] could be interpreted in multiple ways, someone who throws stones, someone with the inability to make sound decisions for himself or herself).

Other terms commonly used by the participants to describe children's mental health conditions indicated the critical importance language plays in helping parents define and identify mental health problems. Although parents used terms such as hiperactividad/hyperactivity, déficit de atención/attention deficit, and autismo/autism, these terms were used colloquially.

Discussions about the terms used to describe child mental health issues led participants into discussions about the differences regarding the way in which these conditions are talked about in the United States and in their countries of origin. A Dominican mother said,

Allá en la Republica Dominicana a los niños con problemas se les llama locos, se piensa que no tienen sentimientos y la gente no los acepta. (In the Dominican Republic children with problems are called crazy, they think that these children do not have feelings and people do not accept them.)

A Mexican mother stated,

Yo le digo a mi niña que no le diga a sus primos que ella viene a esta clínica, porque mi hermano no entiende y la va a juzgar mál. (I tell my daughter not to tell her cousins that she comes to the clinic because my brother does not understand and will judge her.)

Some parents expressed confusion or lack of knowledge regarding the terms used in the United States to describe children's emotional problems, as well as where services to address these are provided.

“Trusted Advisors” About Child-Rearing Practices and Problems

Mothers and sisters were identified as trusted advisors about child-rearing challenges and worries. However, when mothers or sisters were not geographically close, participants reported that they obtained guidance from other mothers and friends. A Mexican mother said, “La gente se llama una a la otra, porque no consigue ayuda ni información” (People call each other because they can't find help or information).

Preferred Health Communication Methods

All participants were receptive to receiving health communication through printed materials, pamphlets, and videos and stressed the importance of disseminating information about mental health to other parents. A Mexican father reported that “Una página de internet, con información clara y videos puede servir, pero sería mejor comerciales acerca de esto en la televisión, mientras están pasando las telenovelas, asíla gente aprendería y vendría más rápido a las clínicas” (A web page with videos and simple information would be good, but it would be even better to have TV commercials about this. They should show them during commercial breaks, when soap operas are broadcasted. Then, people would learn and would come to the clinics more quickly). After probing to obtain more details about their preferences, it was noted that videos, which they find engaging, entertaining, and educational, would be useful formats for health communication. A Puerto Rican grandfather said, “Los videos son buenos, hay gente que no lee bien” (Videos are useful; there are people who do not read well). The parents confirmed that a video format would provide a vehicle to use the concept of “trusted advisors” as mother-to-mother conversations about mistrust, lack of knowledge, and stigma.

Pathways Into Child Mental Health Care

Most participants reported that their children's behavior problems were identified in the school and that the school personnel referred them to a clinic. In general, participants expressed ambivalence regarding next steps when the teachers and school staff identified the need for mental health evaluations. Fear was a barrier to taking action regarding child mental health problems because they often related child mental health issues with severe chronic adult mental illness. The focus group participants referred to negative stories about mental health treatment, heard from older family members, and to their own experiences in childhood seeing a relative or an acquaintance suffering from severe mental illness. A Dominican mother stated,

Cuando escuché la palabra psicológo, me causó un trauma. Pero … la palabra psicquiatra es peor, eso ni mencionarlo. (When I heard the word psychologist, it traumatized me. But the word psychiatrist is worse; don't even mention it).

Participants' Recommendations to Service Providers

Parents who participated in the focus groups unanimously reacted to the groups in a positive manner and requested similar groups on a regular basis. Regarding satisfaction with participation in child mental health services, participants corroborated information previously documented in the literature: that they prefer warm, supportive interactions with providers who speak Spanish, are respectful, and validate their cultural backgrounds (Callejas et al., 2010).

Key Findings

Parents and caregivers indicated that they did not know much about child mental health services until they entered into care. Several aspects were identified as central to the engagement of Latino urban poor parents and caregivers into care: lack of knowledge, stigma, family conflicts, and financial and parenting stress compounded by fear and suspicion regarding the benefits of special education and child mental health services.

Given that child mental health services are provided under the umbrella of psychiatry, parents in the focus groups were under the impression that treatment for children would be similar to the care provided to adults with severe mental illnesses. Therefore, their receptivity to entering this system was very low and marked by fear of stigmatizing connotations and potentially harmful results. Once participants entered care and developed personal relationships with service providers, they reported that their fears diminished.

Findings showed that the poor, LEP, low literacy Latino families who participated in the focus groups generally viewed child mental health services with suspicion and were impacted by a lack of trust in services and misinformation about recognizing and identifying child mental health problems. A key finding was the parents' impression that interactions with the child mental health system could result in the removal of the child from the home by child protective services. This was identified as a common fear among the group participants. Although only one parent had had direct child protective services involvement, the fear of it was expressed in all seven focus groups and generated strong reactions. Therefore, the team noted this as an important issue to be addressed in the child mental health literacy action tool kit. In addition, parents expressed fear and ambivalence about medication and, at times, linked it with punitive action. For example, one parent said, “In public school, if your kid jumps a certain different way, right away they have a problem, and you have to medicate them. If not, they're going to call ACS [Administration for Children and Families].”

Collaborative Development of a Mental Health Literacy Video

The focus group findings confirmed the feasibility and acceptability of videos as a health communication tool. The community co-investigators incorporated the focus group results, their review of existing interventions, and their own experiences as Latino parents and advocates into a thoroughly prepared improvisational exercise that led to the development of the video script, “¿Que le pasa a Carlitos?/What's wrong with Carlitos?” Embedded in EE principles, the video uses a narrative format with characters and themes drawn directly from the words and concepts shared by the participants in the focus groups in order to accurately reflect and speak to the lived experiences of low literacy, LEP, low socioeconomic status (SES) Latino families. The video was produced by the research team, directed by a professional videographer, and featured two of the four Spanish-speaking CCB members. Tables 2–5 are transcripts from the video and this section demonstrates how the script grew from focus group data. (Many cultural nuances are present in the Spanish word selection and phrasings; however, for reasons of space only the English translation is provided in the tables and in the following focus group participant quotations).

Table 2.

¿Que le pasa a Carlitos? Video Transcript: “I Don t Know What to Do.”

| Angela | Hey, you know, I'm having a lot of problems with Carlitos in school. I don't know what to do; the teacher calls me every day |

| Ana | Every day, for the same thing? |

| Angela | Every day the same show. The child doesn't want to sit, he doesn't want to listen, he can't stay still, he never finishes anything, and he can't concentrate |

| Ana | And what does Carlitos say? |

| Angela | Nothing, that he goes and he tries, but then he forgets what he is doing and goes on to something else. So I decided to sit down with him to do homework, and as I am explaining things to him his head is in the clouds. Can you imagine? |

| Ana | He is 7 years old, right? |

| Angela | Yes, so I tell him, come on, Carlitos, let's finish this, and he starts again, playing with something, running around. He's gotten hurt a lot because he climbs everything. In his school, they've told me to come in so that he can see the school psychologist, but I'm not sure about it |

| Ana | So have you gone? |

| Angela | No, I haven't gone |

Note. A mother consults her peer about her son's behavioral problems in school. The content and format of the collaborative video were drawn from the focus group data.

Table 5.

¿Que le pasa a Carlitos? Video Transcript: “I Don't Want My Child to be Medicated.”

| Angela | But they will give him medication, and I don't want that. I don't want my child to be medicated and for him to change |

| Ana | Angela, they are not going to start giving him medication the moment you get there. No, they are going to see and speak with him |

| Angela | Well that's what people say, you know |

| Ana | Yes, people say a lot of things, but Angel was not given medication, they just gave him therapy, and with that he became better. If the child could be medicated, they are of course going to speak with you first, not just give it to him. Angel is in middle school and doing well. It is a long process that takes time, but it has been good |

Note. The peer continues to encourage her friend to seek services.

The video opens with two women, Ana and Angela, sitting together at a kitchen table drinking coffee, and the scene illustrates informal information seeking. The two women discuss one of their child's difficulties in school. (See Table 2, Video Transcript.) The focus group data showed that Latino parents prefer consultation with another parent regarding issues about their children.

Focus group participants indicated that they were generally not the first to identify a problem in their child, as corroborated by studies of Latino parents regarding help seeking for mental health problems (Gerdes, Lawton, Haack, & Schneider, 2013). School is often the location where problematic behavior manifests and is identified, generating a referral to mental health. As a participant said,

I caught it, with a lot of complaints from the school, like, every day I was getting phone calls from the teachers, like “We don't know how to deal with this, we don't know what is going on.”

Parents expressed ambivalence regarding the school's determination that the behaviors were evidence of mental health problems. For example,

In school is where, how do I say? One takes care of their children in the home, but in school there is no control, one does not have control. So there is not one teacher for, for example, five children. Instead there is one teacher for a group of thirty. And so they lose control. The biggest problem is in the school.

In the next part of the video (Table 3), the two women address intergenerational conflict about child-rearing practices. Focus group participants stated that they consulted their own mothers. However, because their mothers often live in home countries where accepted parenting practices may differ from those in the United States, these consultations were inherently problematic. As one mother stated during the focus group, with broad agreement from other participants,

My mother doesn't understand the psychiatry thing, she believes in hitting and slapping. They used to punish me or they hit me, but that is not a way to be effective, I want to do something different.

Table 3.

¿Que le pasa a Carlitos? Video Transcript: “How Do I Help My Child?”

| Ana | And who have you spoken to? |

| Angela | I spoke to my mother first, of course, and she told me just to spank him and the problem will be resolved, but things don't work that way, I've tried so many things |

Note. The mothers refer to intergenerational parenting conflicts.

In the video, Angela pauses and shifts when she references her conversation with her mother in a way that promotes the video audience's identification with her character and with the dilemma of intergenerational parenting conflicts.

In the next excerpt (Table 4), vergüenza/shame and stigma are discussed, and fears about labeling and of child protective services are addressed. A focus group participant stated,

I went to the Board of Education to get help for my son and … he doesn't stay focused, he's always like this [looking around] when the teacher is talking. And they said, you know, to help him we have to define what he has. And so I said, so that means you have to give him a label of what he is? And they said, yes, that is what they do now, otherwise they can't help. I said, well, as long as it doesn't stay on his record for the rest of his life. I don't want him to be labeled like that for the rest of his life.

Table 4.

¿Que le pasa a Carlitos? Video Transcript: “I am Afraid.”

| Ana | I had the same problem with Angel, do you remember him? |

| Angela | Yes |

| Ana | When he was in school, he gave me the same problems. Honestly, I looked for help outside the family and outside the school. You should try something like that, too |

| Angela | Where did you go? |

| Ana | I went to the clinic to see- |

| Angela | To see a psychiatrist? |

| Ana | No, I spoke first to his pediatrician |

| Angela | But at school they have told me they are going to report me, so I am afraid because you know they take children away from their parents |

| Ana | Yes, they take away children who don't get attention from their parents, but you give Carlitos attention. They are only going to help you |

Note. The mothers discuss child protective services.

Social stigma was associated to seeking or embarking on mental health treatment, as detailed by these participant examples.

When they told me that that my girl needed to go to a psychologist … For me to hear that word, psychologist, was horrible, for me it was terrible. I didn't accept it, I said, there's no way my daughter is going to any psychologist. I pushed the idea away many times on various occasions, avoiding the need to make that decision.

Sometimes I think that people believe that it's me that's doing wrong, or something bad. I think that people say, `She's doing something wrong because the child is not behaving himself, she has him badly raised,' and it is as if they are putting all the blame on me, that it is all my fault … and that I am just handing over all my problems to the psychiatrist and not doing anything myself.

Toward the end of the video (Table 5), the mothers addressed ambivalence about medication, which was common among focus group participants. A grandmother stated, “I didn't want her to take medication. Because I didn't want to see my granddaughter in a stupor. ” The video concludes when Ana advises her friend to take action and to seek mental health treatment for her son.

Discussion and Applications to Practice

Todos a bordo is a collaboratively designed intervention to welcome highly stressed Latino parents into child mental health services through a simultaneous process of education and engagement. It is a multicomponent tool kit that features a health education video as an innovative strategy and is, to our knowledge, the only child mental health literacy video in Spanish produced by a Spanish-speaking team of social work academic and community investigators using community-based participatory research methods and EE strategies in combination with consumers' perspectives in its development and design. The video presents the compelling story of a Latina mother who is ambivalent about following up with the school's recommendation to seek mental health services for her son. Her ambivalence unfolds on camera during a conversation with a friend. The mother tells her friend about her fears and concerns. The friend provides clarifying information using familiar words and common terminology. She gently but firmly encourages her to seek services providing details of her own experiences with child treatment. Grounded in information obtained from the consumers themselves, the interactions presented on the video are familiar to highly stressed Latino parents in poverty-impacted communities and help parents identify with the characters in the video.

Latino parents enter child mental health care with suspicions and misinformation regarding what services may entail. The video was designed to help providers open a dialogue with parents early in the treatment process that could identify and clarify each parent's beliefs and expectations in a culturally and linguistically sensitive manner. The child mental health literacy video normalizes the parents' experiences, as well as their emotions and concerns, and introduces a shared vocabulary to the provider and parent for discussing challenging topics that may represent perceptual barriers to engagement in care.

Since the video uses the parents' own words and it raises themes and relevant concerns grounded in focus group data, at a programmatic level, it provides mental health practitioners and administrators an opportunity to further understand and address Latino multistressed families' perceptual barriers to engaging and to staying involved in their children's mental health services. Health educators and other providers within social service agencies, schools, and preventative service programs could use the video as a stand-alone health education tool to address knowledge gaps among community Latino parents not involved in child mental health care. Addressing this group of consumers may indirectly impact service use on a community level, since as Keller and McDade (2000) highlight, peer support networks are catalytic for health activation among parents. Urban poor Latino parents rely on each other as trusted advisors and will likely influence other parents to seek care. This trend was corroborated by focus group participants and demonstrated by the story in the video. The overarching goal of Phase 1 was to better understand the child mental health literacy and engagement needs of highly stressed poor Latino families and to explore the feasibility and acceptability of collaboratively developing an intervention in Spanish to engage and sustain parents in services with their children. In this study, members of the existing CCB brought to the research team over a decade of experience adapting evidence-based practices to urban poor communities. The team conducted a collaborative review of the literature and obtained data through focus groups. These data sources in combination with the team's extensive experience led to the development of the Todos a bordo/All Aboard action tool kit. Latinos with low literacy, low SES, and LEP have responded productively to EE strategies (Borrayo, 2004), the focus group results confirmed the feasibility and acceptability of using video, and the full team approved the format. Thus, a child mental health literacy video, “¿Que le pasa a Carlitos?/What's wrong with Carlitos?” was integrated into the action tool kit.

Although the collaborative production of the video provides a promising method to begin to address the knowledge gaps and the engagement needs of this underserved population, the action tool kit's efficacy needs to be further evaluated. The Todos a bordo/All Aboard action tool kit is currently being implemented and tested in real-world child mental health settings in Phase 3 of the pilot.

Acknowledgments

Funding The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported by grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (grant number P20 MH085983). For a link to the Todos a bordo action toolkit, please contact the corresponding author.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Abdou CM, Schetter CD, Jones F, Roubinov D, Tsai S, Jones L. Community perspectives: Mixed-methods investigation of culture, stress, resilience, and health. Ethnicity & Disease. 2010;20 S2-41-8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alegria M, Canino G, Lai S, Ramirez RR, Chavez L, Rusch D, Shrout PE. Understanding caregivers' help-seeking for Latino children's mental health care use. Med Care. 2004;42:447–455. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000124248.64190.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alegria M, Lin JY, Green JG, Sampson NA, Gruber MJ, Kessler RC. Role of referrals in mental health service disparities for racial and ethnic minority youth. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2012;5:703–711. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.05.005. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvidrez J, Snowden LR, Kaiser DM. Involving consumers in the development of a psychoeducational booklet about stigma for Black mental health clients. Health Promotion Practice. 2010;11:249–258. doi: 10.1177/1524839908318286. doi:10.1177/1524839908318286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagnell AL, Santor DA. Building mental health literacy: Opportunities and resources for clinicians. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2012;21:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2011.09.007. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannon WM, Cavaleri MA, Rodriguez J, McKay MM. Conclusions and directions for future research concerning racial socialization. Social Work in Mental Health. 2008a;6:80–82. doi: 10.1080/15332980802032490. doi:10.1080/15332980802032490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannon WM, Cavaleri MA, Rodriguez J, McKay MM. The effect of racial socialization on urban African-American use of child mental health services. Social Work in Mental Health. 2008b;6:9–29. doi: 10.1080/15332980802032326. doi:10.1080/15332980802032326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannon WM, McKay MM, Chacko A, Rodriguez JA, Cavaleri M. Cultural pride reinforcement as a dimension of racial socialization protective of urban African-American child anxiety. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Human Services. 2009;90:79–86. doi: 10.1606/1044-3894.3848. doi:10.1606/1044-3894.3848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baptiste DR, Paikoff RL, McKay MM, Madison-Boyd S, Coleman D, Bell C. Collaborating with an urban community to develop an HIV and AIDS prevention program for Black youth and families. Behavior Modification. 2005;29:370–416. doi: 10.1177/0145445504272602. doi:10.1177/0145445504272602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrio C, Yamada AM. Culturally based intervention development: The case of Latino families dealing with schizophrenia. Research on Social Work Practice. 2010;20:483–492. doi: 10.1177/1049731510361613. doi:10.1177/1049731510361613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batalova J. Spotlight on limited English proficient students in the United States. Migration Policy Institute. 2006 Retrieved from http://www.migrationinformation.org/usfocus/display.cfm?ID=373#.

- Bhana A, Mellins CA, Petersen I, Alicea S, Myeza N, Holst H, McKay M. The VUKA family program: Piloting a family-based psychosocial intervention to promote health and mental health among HIV infected early adolescents in South Africa. AIDS Care. 2013;26:1–11. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2013.806770. doi:10.1080/09540121.2013.806770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrayo EA. Where's Maria? A video to increase awareness about breast cancer and mammography screening among low-literacy Latinas. Preventive Medicine. 2004;39:99–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.03.024. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabassa LJ, Contreras S, Aragon R, Molina GB, Baron M. Focus group evaluation of “secret feelings”: A depression fotonovela for Latinos with limited English proficiency. Health Promotion Practice. 2011;12:840–847. doi: 10.1177/1524839911399430. doi:10.1177/1524839911399430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabassa LJ, Molina GB, Baron M. Depression fotonovela: Development of a depression literacy tool for Latinos with limited English proficiency. Health Promotion Practice. 2012;13:747–754. doi: 10.1177/1524839910367578. doi:10.1177/1524839910367578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callejas LM, Hernandez M, Nesman T, Mowery D. Creating a front porch in systems of care: Improving access to behavioral health services for diverse children and families. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2010;33:32–35. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2009.05.010. doi:10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2009.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callejas LM, Nesman T, Mowery D, Hernandez M. Creating a front porch: Strategies for improving access to mental health services (Making children's mental health services successful series, FMHI pub. no. 240-3) University of South Florida, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, Research & Training Center for Children's Mental Health; Tampa, FL: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Carey M, Asbury JE. Focus group research. Left Coast Press; Walnut Creek, CA: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chavez V, Israel B, Allen AJ, 3rd, DeCarlo MF, Lichtenstein R, Schulz A. A bridge between communities: Video-making using principles of community-based participatory research. Health Promotion Practice. 2004;5:395–403. doi: 10.1177/1524839903258067. doi:10.1177/1524839903258067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enchautegui ME. Welfare payments and other economic determinants of female migration. Journal of Labor Economics. 1997;15:529–54. doi: 10.1086/209871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falcón A. NiLP Latino datanote. National Institute for Latino Policy; New York, NY: 2010. Latino economic distress: Recent statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Gagliano ME. A literature review on the efficacy of video in patient education. Journal of Medical Education. 1988;63:785–792. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198810000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelman CR. Learning from recruitment challenges: Barriers to diagnosis, treatment, and research participation for Latinos with symptoms of Alzheimer's disease. Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 2010;53:94–113. doi: 10.1080/01634370903361847. doi:10.1080/01634370903361847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdes AC, Lawton KE, Haack LM, Schneider BW. Latino parental help seeking for childhood ADHD. Administration and Policy in Mental Health. 2013;41:503–513. doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0487-3. doi:10.1007/s10488-013-0487-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine; Chicago, IL: 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Guarnaccia PJ, Martinez I, Acosta H. Mental health in the Hispanic community: An overview. Journal of Immigrant and Refugee Services. 2005;3:21–46. doi:10.1300/J191v3n01_02. [Google Scholar]

- Halcomb EJ, Andrew S. Triangulation as a method for contemporary nursing research. Nurse Researcher. 2005;13:71–82. doi: 10.7748/nr.13.2.71.s8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halcomb EJ, Gholizadeh L, DiGiacomo M, Phillips J, Davidson PM. Literature review: Considerations in undertaking focus group research with culturally and linguistically diverse groups. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2007;16:1000–1011. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01760.x. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton HA, Marshall L, Rummens JA, Fenta H, Simich L. Immigrant parents' perceptions of school environment and children's mental health and behavior. The Journal of School Health. 2011;81:313–319. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2011.00596.x. doi:10.1111/j.1746-1561.2011.00596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison ME, McKay MM, Bannon WM., Jr Inner-city child mental health service use: The real question is why youth and families do not use services. Community Mental Health Journal. 2004;40:119–131. doi: 10.1023/b:comh.0000022732.80714.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohmann AA, Shear MK. Community-based intervention research: Coping with the “noise” of real life in study design. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:201–207. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorm AF, Korten AE, Jacomb PA, Christensen H, Rodgers B, Pollitt P. “Mental health literacy”: A survey of the public's ability to recognize mental disorders and their beliefs about the effectiveness of treatment. The Medical Journal of Australia. 1997;166:182–186. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1997.tb140071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorm AF, Wright A. Influences on young people's stigmatizing attitudes towards peers with mental disorders: National survey of young Australians and their parents. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science. 2008;192:144–149. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.039404. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.107.039404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller J, McDade K. Attitudes of low-income parents toward seeking help with parenting: Implications for practice. Child Welfare. 2000;79:285–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerkorian D, McKay M, Bannon WM., Jr Seeking help a second time: Parents'/caregivers' characterizations of previous experiences with mental health services for their children and perceptions of barriers to future use. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2006;76:161–166. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.76.2.161. doi:10.1037/0002-9432.76.2.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RA. Analyzing focus group interviews. Journal of Wound, Ostomy, and Continence Nursing: Official Publication of the Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society/WOCN. 2006;33:478–481. doi: 10.1097/00152192-200609000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landale NS, Oropesa RS, Bradatan C. Hispanic families in the United States: Family structure and process in an era of family change. In: Tienda M, Mitchell F, editors. Hispanics and the future of America. chap. 5. National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2006. pp. 138–178. Retrieved from http://www. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK19902/ [Google Scholar]

- Lauber C, Nordt C, Falcato L, Rossler W. Do people recognize mental illness? Factors influencing mental health literacy. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 2003;253:248–251. doi: 10.1007/s00406-003-0439-0. doi:10.1007/s00406-003-0439-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason CN, Salas D, Ebanks J. Economic security and well-being index for women in New York City. The New York Women's Foundation. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.nywf.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/New-York-Womens-Foundation-Report.pdf.

- McBride CK, Baptiste D, Traube D, Paikoff RL, Madison-Boyd S, Coleman D. Family-based HIV preventive intervention: Child level results from the CHAMP family program. Social Work in Mental Health. 2007;5:203–220. doi: 10.1300/J200v05n01_10. doi:10.1300/J200v05n01_10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay MM, Bannon WM., Jr Engaging families in child mental health services. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2004;13:905–921. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2004.04.001. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay MM, Alicea S, Elwyn L, McClain ZRB, Parker G, Small LA, Mellins CA. The development and implementation of theory-driven programs capable of addressing poverty-impacted children's health, mental health, and prevention needs: CHAMP and CHAMP+, evidence-informed, family-based interventions to address HIV risk and care. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2014;43:428–441. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2014.893519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay MM, Chasse KT, Paikoff R, McKinney LD, Baptiste D, Coleman D. Family-level impact of the CHAMP family program: A community collaborative effort to support urban families and reduce youth HIV risk exposure. Family Process. 2004;43:79–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2004.04301007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay MM, Gopalan G, Franco L, Dean-Assael K, Chacko A, Jackson J, Fuss A. A collaboratively designed child mental health service model: Multiple family groups for urban children with conduct difficulties. Research in Social Work Practice. 2011;21:664–674. doi: 10.1177/1049731511406740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay MM, Gopalan G, Franco LM, Kalogerogiannis K, Umpierre M, Olshtain-Mann O. It takes a village to deliver and test child and family-focused services. Research on Social Work Practice. 2010;20:476–482. doi: 10.1177/1049731509360976. doi:10.1177/10497315 09360976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay MM, Harrison ME, Gonzales J, Kim L, Quintana E. Multiple-family groups for urban children with conduct difficulties and their families. Psychiatric Services. 2002;53:1467–1468. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.11.1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez JL, Westerberg D. Implementation of a culturally adapted treatment to reduce barriers for Latino parents. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2012;18:363–372. doi: 10.1037/a0029436. doi:10.1037/a0029436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messam T, McKay MM, Kalonerogiannis K, Alicea S, HOPE Committee CHAMP Collaborative Board Adapting a family-based HIV prevention program for homeless youth and their families: The HOPE (HIV prevention Outreach for Parents and Early Adolescents) Family Program. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment. 2010;20:303–318. doi: 10.1080/10911350903269898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan DL, Krueger RA. When to use focus groups and why. In: Morgan DL, editor. Successful focus groups: Advancing the state of the art. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1993. pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- National Alliance on Mental Illness Latino community mental health fact sheet. 2006 Retrieved from http://www.nami.org/Content/NavigationMenu/Find_Support/Multicultural_Support/Annual_Minority_Mental_Healthcare_Symposia/Latino_MH06.pdf.

- National Women's Law Center Poverty among women and families, 2000–2010: Extreme poverty reaches record level as Congress faces critical choices. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.nwlc.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/povertyamongwomenand families2010final.pdf.

- Paikoff RL, Traube DE, McKay MM. Overview of community collaborative partnerships and empirical findings: The foundation for youth HIV prevention. Social Work in Mental Health. 2007;5:3–26. doi: 10.1300/J200v05n01_01. doi:10.1300/J200v05n01_01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Hispanic Center Tabulations of 2010 American community survey. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.pewhispanic.org/files/2013/02/Statistical-Portrait-of-Hispanics-in-the-United-States-2011_FINAL.pdf.

- Pinto RM, McKay MM, Baptiste D, Bell CC, Madison-Boyd S, Paikoff R. Motivators and barriers to participation of ethnic minority families in a family-based HIV prevention program. Social Work in Mental Health. 2007;5:187–201. doi: 10.1300/J200v05n01_09. doi:10.1300/J200v05n01_09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers EM, Shefner-Rogers CL. A history of the entertainment-education strategy. Paper presented to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention's Conference on Using Entertainment-Education to Reach a Generation at Risk, Atlanta, GA. 1994 Retrieved from http://utminers.utep.edu/asinghal/technical %20reports/EE%20backwardforward.pdf.

- Ryerson WN. Population communications international: Its role in family planning soap operas. Population and Environment: A Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies. 1994;15:255–264. [Google Scholar]

- Sabido M. The tone: Theoretical vicissitudes, practice adventures, and entertainment with social benefit. National Autonomous University; Mexico City, Mexico: 2002. El tono: Andanzas teóricas, aventuras prácticas, el entretenimiento con beneficio social. [Google Scholar]

- Santiago CD, Wadsworth ME. Family and cultural influences on low-income Latino children's adjustment. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2011;40:332–337. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2011.546038. doi:10.1080/15374416.2011.546038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sealy YM, Zarcadoolas C, Dresser M, Wedemeyer L, Short L, Silver L. Using public health detailing and a family-centered ecological approach to promote patient-provider-parent action for reducing childhood obesity. Childhood Obesity. 2012;8:132–146. doi: 10.1089/chi.2011.0025. doi:10.1089/chi.2011.0025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shobe MA, Coffman MJ, Dmochowski J. Achieving the American dream: Facilitators and barriers to health and mental health for Latino immigrants. Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work. 2009;6:92–110. doi: 10.1080/15433710802633601. doi:10.1080/15433710802633601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singhal A, Rogers EM. Entertainment-education a communication strategy for social change. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Singhal A, Rogers EM. A theoretical agenda for entertainment-education. Communication Theory. 2002;12:117–135. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder AR, McLaughlin DK, Findeis J. Household composition and poverty among female-headed household with children: Differences by race and residence. Rural Sociology. 2006;1:597–624. [Google Scholar]

- Sood S. Audience involvement and entertainment-education. Communication Theory. 2002;12:153–172. [Google Scholar]

- Sood S, Boulay M, Storey JD. Indirect exposure to a family planning mass media campaign in Nepal. Journal of Health Communication. 2002;7:379–399. doi: 10.1080/10810730290001774. doi:10.1080/10810730290001774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sood S, Storey D. Increasing equity, affirming the power of narrative and expanding dialogue: The evolution of entertainment education over two decades. Critical Arts: South-North Cultural and Media Studies. 2013;27:9–35. doi:10.1080/02560046.2013.767015. [Google Scholar]

- Spanglish. Oxford unity press dictionaries online. n.d. Retrieved from http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/us/definition/american_ english/Spanglish.

- Sperber E, McKay MM, Bell CC, Petersen I, Bhana A, Paikoff R. Adapting and disseminating a community-collaborative, evidence-based HIV/AIDS prevention program: Lessons from the history of CHAMP. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies. 2008;3:150–158. doi: 10.1080/17450120701867561. doi:10.1080/17450120701867561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau American factfinder fact sheet: CT. 2010 Retrieved from http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src bkmk.

- Valle R, Yamada AM, Matiella AC. Fotonovelas: A healthy literacy tool for educating Latino older adults about dementia. Clinical Gerontologist. 2006;30:71–88. doi:10.1300/J018v30n01_06. [Google Scholar]

- Wadsworth ME, Santiago CD. Risk and resiliency processes in ethnically diverse families in poverty. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:399–410. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.3.399. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.22.3.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]