Abstract

Objective

Community Engagement and Planning (CEP) could improve dissemination of depression quality improvement in under-resourced communities; but its effects on provider training participation relative to more standard technical assistance or Resources for Services (RS) are unknown. To compare effects of CEP, which trains networks of healthcare and social-community agencies jointly, and RS, which provides technical support to individual programs, on program and staff-level participation in depression quality improvement trainings.

Methods

Matched programs from healthcare and social-community programs in two communities were randomized to RS or CEP. Data were from 1622 eligible staff members from 95 enrolled programs. Measures: Primary outcomes: for programs, any staff trained; and for staff, total hours of training. Secondary outcomes: training in specific depression collaborative care components.

Results

CEP programs relative to RS were more likely to participate in any trainings across sectors (p<.001) and from social-community sectors (p<.001), but not from healthcare. Among staff participating in trainings, CEP relative to RS had greater mean training hours (p<.001) overall and for each depression care component (cognitive behavioral therapy, care management, other trainings, p<.001) except medication management.

Conclusions

Compared with RS, CEP to implement depression quality improvement increased program and staff training participation overall. CEP had a greater effect on any staff training participation within social-community sectors than RS, but not within healthcare. CEP may be an effective strategy to promote staff participation in depression improvement in under-resourced communities.

Depressive disorders are leading causes of disability in the United States with racial disparities in access to, quality and outcomes of care in under-resourced communities.1-7 Primary care, depression quality improvement programs using team-based, chronic disease management can improve quality and care outcomes for depressed adults, including racial and ethnic minorities.8-17 Under healthcare reform, Medicaid behavioral health homes incentivize partnerships among healthcare, mental health, and social-community agencies (e.g. parks, senior centers), by noting “ Services must include prevention and health promotion, healthcare, mental health and substance use, and long-term care services, as well as linkages to community supports and resources.”18 However, few guidelines exist to organize diverse agencies into systems supporting chronic disease management. Also, no studies exist comparing the effects of alternative training approaches for depression quality improvement with diverse providers from healthcare and social-community programs.

This study analyzes data from Community Partners in Care (CPIC), a group-level, randomized, comparative-effectiveness study of two implementation approaches for evidence-based, depression quality improvement toolkits adapted for diverse healthcare and social-community settings. One implementation approach relies on more traditional technical assistance to individual programs (Resources for Services, RS). The other (Community Engagement and Planning, CEP) used community-partnered, participatory research (CPPR) principles to support collaborative planning across programs to implement the same depression care toolkits through a network.19-25 Programs randomized to each approach included healthcare and social-community programs.20-21 Six-month follow-up revealed that relative to RS, CEP improved depressed clients’ mental health-related quality of life, increased physical activity, and reduced homelessness risk factors; while reducing behavioral health hospitalizations and specialty medication visits, and increasing depression services use in primary care/public health, faith-based and park/community center programs with continued effects on mental health-related quality of life at 12-months.20,25 This study focuses on CPIC's main intervention effects for primary program (i.e. program training participation) and staff-level (i.e. total training hours) outcomes, participation in evidence-based, depression quality improvement trainings. We hypothesized that CEP would lead to a broader range of staff training options than RS. To determine what types of organizations would participate in trainings, we compared interventions’ effects by program type (i.e. healthcare versus social-community). Based on prior work, we hypothesized that CEP relative to RS would increase mean hours of training participation, especially for social-community programs where such training is novel.26-28 To inform future depression quality improvement dissemination efforts in safety-net communities, we conducted exploratory analyses of interventions’ effects on staff training participation for each depression quality improvement component and by services sector.

Methods

CPIC was conducted using community partnered participatory research (CPPR), a manualized form of community-based participatory research, with community and academic partners co-leading all aspects of research under equal authority.19-25,28-30 The study was designed and implemented by the CPIC Council, comprised of 3 academic organizations and 22 community agencies. Study design is described elsewhere.19-21,25

Sampling and Randomization

Two communities with high poverty and low insurance rates,31 South Los Angeles and Hollywood-Metro Los Angeles, were selected by convenience based on established partnerships.19,32-36

Programs

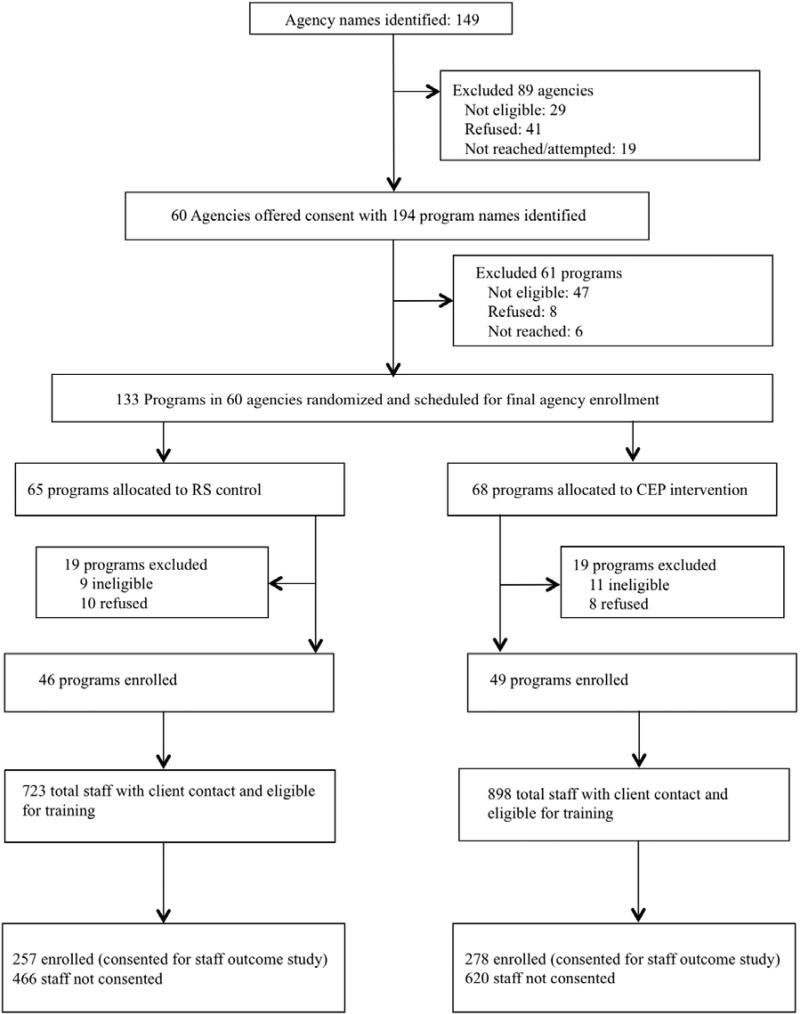

Community nominations supplemented county lists to identify agencies.32 We assessed eligibility and offered consent to 60 potentially eligible agencies having 194 programs, of which 133 were potentially eligible (≥15 clients per week, ≥1 staff, not focused on psychotic disorders or home services) and randomized 133 programs (65 RS, 68 CEP, Appendix Figure 1). Agencies were paired into units or clusters of smaller programs, based on location and program characteristics and randomized to CEP or RS. Site visits were conducted post-randomization to finalize enrollment; 20 programs were ineligible, 18 refused and 95 programs from 50 consenting agencies enrolled (Appendix Figure 1, Table 2). Program administrators were informed of intervention status by letter. Participating and nonparticipating programs were from comparable neighborhoods based on U.S. Census data on age, sex, race, population density, income by zip code level (each p>0.10).37

Table 2.

Number of programs had at least 1 staff participated in any training by intervention status

| Total | RS | CEP | Group effect | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | Test statistic | Df | p | |

| All enrolled programs (N=95) | 70 | 74 | 28 | 61 | 42 | 86 | 7.6 | 1 | .006 |

| Programs from healthcare sectors (primary care, mental health substance abuse treatment (N=55) | 29 | 47 | 19 | 66 | 24 | 92 | 5.8 | 1 | .016 |

| Programs from social-community sectors (homeless, social-community) (N=40) | 23 | 58 | 9 | 53 | 18 | 78 | 2.9 | 1 | ns |

* Chi-square test was used for a comparison between the two intervention arms.

Staff

All staff with direct client contact (paid, volunteer, licensed, non-licensed) were eligible for trainings. The number of eligible staff was enumerated through an item on baseline program administrator surveys (See Appendix A for item.) For nonresponse or outliers with low or high values, we made phone calls to programs to obtain, confirm, or correct information. Ninety-five enrolled programs had 1622 eligible staff. One eligible administrative staff was excluded from analysis due to overseeing both an RS and a CEP assigned program so 1621 was the final analytic sample.

RAND and participating agencies’ Institutional Review Boards’ approved study procedures. Written consent was obtained for administrator surveys while oral consent was obtained to use training event staff attendance data.

Interventions

The interventions were designed to support implementation of depression quality improvement components relevant to each program's scope. Both interventions used the same evidence-based toolkits supporting depression care management (i.e. screening, coordination, patient education), medication management, and depression cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT).16,19,21,25,38-40 Materials were available to eligible programs via printed manuals, a website, and flashdrives.34 Toolkits were introduced pre-randomization at one-day kick-off conferences in each community.19,21,25 After randomization and enrollment, within each intervention condition, training invitations were offered by phone, e-mail, and postcards to staff attending prior study meetings with encouragement to circulate to all eligible staff. Enrolled programs’ eligible staff could choose to participate in any, all, or no trainings offered by intervention for free. The only participation incentives were continuing education credits, access to trainings, and food during trainings.

Resources for Services (RS)

RS's content, structure, and training intensity was developed by the research team, not by participating RS agencies, to reflect a more traditional depression quality improvement implementation approach based on technical assistance under a “train-the-trainer” model to individual programs similar to Partners in Care.19,20,21,25,39 RS trainings (12/2009 -7/2010) were provided by an interdisciplinary team of 3 psychiatrists for medication management, a nurse care manager, a licensed psychologist for CBT, and an experienced community administrator, and research assistants through 21webinars and primary care site visits over 22 hours across South Los Angeles and Hollywood-Metro. Toolkits were modified to fit programs.

Community Engagement and Planning (CEP)

Programs assigned to CEP were invited to identify one or more staff to join South Los Angeles and Hollywood-Metro CEP Councils. Councils met bi-weekly for 2 hours over 5 months to tailor depression care toolkits and implementation plans towards each community's strengths through program collaboration. Councils were given a written manual and on-line materials including community engagement strategies. In South Los Angeles, 12 academic and 13 community participants met from 12/2009-4/2010; and in Hollywood-Metro LA, 19 academic and 11 community participants from 3/2010-7/2010. Each Council met through 1/2011 to oversee implementation. During planning, each CEP council modified the toolkits and trainings (i.e. goals, intensity, duration, format) to fit community and program needs.29,30 CEP trainings were not pre-specified. Each CEP council could have chosen plans ranging from replicating RS to conducting no trainings.

Data Sources

Data sources include services sector and community for 95 enrolled programs obtained from administrators during recruitment; number of eligible staff having direct client contact from an item on administrator baseline surveys and follow-up phone calls to administrators; training event data (date, hours, collaborative care component) and staff program affiliation from attendee registration before training events, training logs and attendee sign-in's at trainings. A data set was created representing staff members in programs and coded by program type, intervention status and community.

Outcomes

At the program level, the primary outcome is program participation in depression quality improvement trainings, defined by the percentage of programs with any staff participation in training. At the staff level, the primary outcome is total hours of staff participation across all programs and stratified by sector. Secondary outcomes for staff include percentage of staff with any participation and hours of participation in each depression care component (medication management, CBT, care management, other).

The main independent variable is program random assignment (CEP, RS). Covariates include program service sector (“healthcare”: primary care, mental health, and substance abuse; “social-community”: homeless and other social / community-based services), and community (South Los Angeles, Hollywood-Metro).

Statistical Methods

At baseline, we compared program and staff characteristics by intervention status using chi-square tests. For main program-level analyses, we examined interventions’ effects on outcomes controlling for program sector and community and report chi-square statistics. For staff-level analyses, we examined the compared interventions’ effects on total hours in training using two-part models because of skewed distributions.41 The first part estimates the probability of any training hours using logistic regression. The second part estimates the total training hours, if positive, as the log of hours, given any, using ordinary least squares controlled for community and sector.42 We used smearing estimates for retransformation, applying separate factors for each intervention group to ensure consistent estimates.43,44 We adjusted models for clustering by programs using SAS macros developed by Bell and McCaffrey using a bias reduction method for standard error estimation.45 We also conducted exploratory stratified analyses within specific sectors, grouped as primary care/public health, mental health specialty, substance abuse, homeless serving, and other community sectors, using logistic regression models for dichotomous measures and log-linear models for counts with intervention condition as the independent variable adjusted for program sector and community as sector cell sizes were not sufficient for two-part models.46 We supplement adjusted models with unadjusted raw data to assess robustness. (See Appendix B and C). Analyses were conducted using SUDAAN Version 11.0 (http://www.rti.org/sudaan/), and accounted for clustering (staff within programs).47

Results

Of 95 enrolled and randomized programs, 46 were in RS and 49 in CEP. Randomized programs showed no statistically significant differences by baseline characteristics (community, program type, total staff) or participation in study activities before randomization (i.e. attended a kick-off conference) (Appendix B). About half were from each community and programs were well distributed across sectors (primary care [18%] mental health [19%], substance abuse [21%], homeless-serving [11%], community-based [32%]).

Of 1,621 eligible staff, 723 were from RS and 898 were from CEP programs; 30% were from primary care/public health, 18% from mental health specialty, 16% from substance abuse, 10% from homeless-serving and 25% from community-based programs, with no significant differences by intervention status on staff characteristics. (Appendix B)

After program randomization, CEP councils in Hollywood-Metro and South Los Angeles developed more intensive trainings (e.g. CBT support for 1-2 cases over 12-16 weeks, 10 week webinar group CBT consultation), more flexible trainings offering the same content (e.g. webinar, conference calls, multiple one-day conferences), and broader trainings (e.g. self-care for providers, active listening) going beyond the kick-off conference and RS trainings. Table 1 summarizes CEP modifications and innovations. Across communities, CEP provided 144 trainings totaling 220.5 hours: 135 hours for CBT, 60 hours for care management, 6 hours for medications, and 17.5 for other skills.

Table 1.

CPIC Intervention and Training Features by Conditiona

| Resources for Services (RS) | Community Engagement and Planning (CEP) | |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Model | 1)Depression care QI toolkit (slides, workbooks, patient education) via print, flash drives, and website. 2)Trainings via 12 webinars / conference calls and site visits to primary care 3)Community engagement specialist for up to 5 outreach calls to encourage participation and fit toolkits to programs 4)Study paid for trainings and materials at $16,333 per community. |

1)Depression care QI toolkit (slides, workbooks, patient education) via print, flash drives, and website. 2)5 months of 2-hour, bi-weekly planning meetings for a CEP councils to tailor materials and develop and implement a written training plan for each community, guided by a manual and community engagement model 3)Co-leadership by study Council following community engagement and social justice principles to encourage collaboration and network building 4)$15,000 per community for consultations and training modifications |

| Implemented | ||

| Overall | 21 Webinars and 1 primary care site visit | Multiple one-day conferences with follow-up trainings at sites; webinar and telephone-based supervision |

| CBT and clinical assessment | Materials and 4 webinars offered for licensed physicians, psychologists, social workers, nurses marriage and family therapists | Tiers of training: For licensed providers plus substance abuse counselors1) intensive CBT support included feedback on audiotaped therapy session with one to two depression cases for 12-16 weeks, 2) 10 week webinar group consultation, and for any staff trainee 3) orientation workshops for concepts/approaches. |

| Care management | 4 webinars and resources for depression screening, assessment of comorbid conditions, client education and referral, tracking visits to providers, medication adherence, and outcomes, and introduction to problem solving therapy and/ behavioral activation; for nurses, case workers, health educators, spiritual advisors, promotoras, lay counselors | 1)In-person conferences, individual agency site visits, and telephone supervision for the same range of providers. 2)Modifications included a focus on self-care for providers, simplification of materials such as fact sheets and tracking with shorter outcome measures. Similar range of providers and staff as RS. 3)Training in active listening in one community; training of volunteers to expand capacity in one community 4)Development of an alternative “resiliency class” approach to support wellness for Village Clinic |

| Medication and clinical assessment | For MD, Nurses, Nurse practitioners, physician's assistants; training in medication management and diagnostic assessment; webinar and in-person site visit to primary care | Two-tiered approach with training for medication management and clinical assessment coupled with information on complementary / alternative therapies and prayer for depression, through training slides; and second tier of orientation to concepts for lay providers. |

| Administrators/Other | Webinar on overview of intervention plan approaches to team building/management and team-building resources | 1)Conference break-outs for administrators on team management and building and team -building resources; support for grant-writing for programs 2)Administrative problem-solving to support “Village Clinic” including option of delegation of outreach to clients from RAND survey group, identification of programs to support case management, resiliency classes, and CBT for depression |

| Training events | 21 webinars and 1 site visit (22 hours) (combined communities) CBT (8 hours) Care management (8 hours) Medication (1 hours) Implementation support for Administrators (5 hours) |

144 training events (220.5 total hours) (combined communities) CBT (135 hours) Care Management (60 hours) Medication (6 hours) Other Skills (19.5 hours) |

Adapted from 25Chung et al. Annals of Internal Medicine 161: S23-34, 2014. Copyright © 2014 American College of Physicians. Used with permission.

After randomization, a greater percentage of CEP programs participated in trainings than RS (CEP 86%, RS 61%, p=.006). Stratified analyses by program sector, showed a greater percentage of CEP programs from healthcare sectors participated in trainings than RS (p=.016). (Table 2) Although not significant, a similar trend within social-community sectors was found.

In two-part models, CEP-assigned program staff as compared to RS were more likely to participate in any training overall (p<.001) and from social-community sectors (p<.001), but intervention differences on any participation was not apparent for healthcare sectors (Table 3). Among staff participating in trainings, CEP staff had more hours of training across sectors (RS=.19, CEP=2.35, p<.001) and within healthcare (RS=.35, CEP=1.88, p=.004) and social-community programs (RS=.1, CEP=2.91, p=.003) than RS. Similarly, among staff participating in trainings, CEP had greater mean hours for all depression quality improvement components (CBT, care management, other training) than RS, except medication trainings where intervention differences were not significant.

Table 3.

Estimation results of two-part model on staff total training hours* by intervention status

| RS | CEP | Part-1 logit | Part-2 among users | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Estimated hours | 95%CI | Estimated hours | 95%CI | t | df | P | t | df | p |

| Primary outcome | ||||||||||

| Total hours in training | .19 | .03-.36 | 2.35 | 1.09-3.62 | 3.90 | 94 | <.001 | 4.67 | 94 | <.001 |

| Healthcare programsa | .35 | .03-.66 | 1.88 | .31-3.46 | 1.39 | 54 | ns | 3.08 | 54 | .004 |

| Social-community programsb | .1 | −.03-.22 | 2.91 | 1.53-4.29 | 4.51 | 39 | <.001 | 3.29 | 39 | .003 |

| Secondary outcomes-collaborative care component | ||||||||||

| Total hours in CBTc training | .12 | .01-.22 | .92 | .24-1.59 | 2.39 | 94 | .019 | 3.90 | 94 | <.001 |

| Total hours in CMd training | .04 | 0-.07 | .79 | .39-1.19 | 4.88 | 94 | <.001 | 4.02 | 94 | <.001 |

| Total hours in mede training | .01 | −.01-.03 | .08 | .03-.12 | 2.47 | 94 | .015 | .32 | 94 | ns |

| Total hours in other typesf of training | .05 | .01-.09 | .58 | .22-.94 | 2.81 | 94 | .006 | 7.06 | 94 | <.001 |

Two-part model, the first part is the probability of any positive hours of training using logistic regression, the second part estimates the total training hours, if positive, is the log of hours given any, using ordinary least squares controlled for community and accounted for the design effect of the cluster randomization; full sample analyses were also controlled for sector.

healthcare programs: primary care, public health, mental health, substance abuse treatment programs.

social-community programs: community-based (social services agencies, faith-based, senior centers, parks and recreation, barber shops) and homeless serving programs. .

CBT= cognitive behavioral therapy.

CM=care management.

med training=antidepressant medication management and education.

Other types of training= administrator training in team building, grant writing for programs, active listening, “resiliency class”

In exploratory stratified analysis by service sector there were no intervention differences in percentage of staff in attending any training within primary care or mental health specialty programs, however CEP staff had greater participation than RS from substance abuse (p=.005), homeless service (p<.001), and community-based programs (p<.001, Table 4). In addition, as compared to RS, CEP significantly increased training hours for staff from all sectors except for primary care.

Table 4.

Staff participation outcomes in training activities by program sector*

| RS | CEP | Group effect | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | 95% CI | Estimate | 95% CI | t | df | p | |

| Any training, % | |||||||

| Primary care | 7 | −1- 14 | 11 | 1-21 | 0.7 | 94 | ns |

| Mental health services | 9 | −2- 20 | 27 | −1-56 | 1.5 | 94 | ns |

| Substance abuse | 8 | −.2 - 16 | 40 | 19-61 | 2.9 | 94 | .005 |

| Homeless services | 6 | −1 - 12 | 61 | 33- 89 | 3.7 | 94 | <.001 |

| Community-based programsa | 4 | −1- 9 | 12 | 5.3-18.5 | 4.2 | 94 | <.001 |

| Total hours in training, mean | |||||||

| Primary care | .18 | −.04-.39 | .65 | −.10-1.40 | 1.5 | 94 | ns |

| Mental health services | .36 | −.13-.85 | 4.31 | −1.33-9.95 | 2.8 | 94 | .005 |

| Substance abuse | .27 | −.06-.60 | 3.93 | 1.81-6.06 | 3.8 | 94 | <.001 |

| Homeless services | .17 | −.08-0.42 | 2.29 | .45-4.12 | 3.1 | 94 | .003 |

| Community-based programsa | .07 | −.02-.16 | 3.09 | 1.66-4.53 | 5.8 | 94 | <.001 |

Logistic regression models for binary variables or log-linear regression models for total hours adjusted for community and accounted for the design effect of the cluster randomization.

community-based programs: social services agencies, faith-based, senior centers, parks and recreation, barber shops.

Discussion

Our main finding is that a community engagement and planning (CEP) approach developed a broader and more flexible range of training experiences with more hours relative to technical assistance (RS), for implementing depression collaborative care across diverse healthcare and social community sectors relative to technical assistance to individual programs (RS). Subsequently, CEP as compared to RS programs had higher training participation rates at program and staff levels overall and across all components of depression quality improvement. This is an important finding that may offer insight into previously reported positive effects of CEP on client health-related quality of life outcomes at 6- and 12-months.20,25 Pre-randomization, there were no significant differences in participation between RS and CEP. However, after randomization, 86% of CEP programs participated in any training versus 61% of RS with significantly greater participation from healthcare programs assigned to CEP (92%) than RS (66%). Given observed differences by intervention condition occurred within a group-randomized trial increases confidence that in the difference being due to intervention approach, i.e. CEP's increased training intensity and greater focus on engaging programs and providers in training as a network, based on a community-driven plan.

On the primary outcomes for program participation, our study showed similar results with CEP assigned program staff being more likely to participate in a training overall and from social-community programs, but CEP did not appear to result in a greater likelihood of any participation in trainings from healthcare sectors. However, of staff with any training participation, CEP had greater hours of training overall as well as from both social-community and healthcare programs. Further exploratory analyses suggest that CEP's effects at the program-level may be greater for programs from healthcare than social-community sectors; but among staff attending any training, CEP had effects on increasing mean training hours for both healthcare and social-community program sector staff as compared to RS.

Few reports in the mental health services literature describe effects of implementation interventions for evidence-based programs on penetration of training on staff and programs. One study found that increased training participation on an evidence-based, child curriculum was associated with increased intervention delivery to patients.48 Another found provider financial incentives promoted depression collaborative care implementation in healthcare systems.49 In contrast, in CPIC, enrolled programs and staff were told they could participate in any, all, or no trainings with continuing education credits, access to trainings and materials, and food during trainings as the only incentives. This suggests that community engagement can activate agencies and providers, particularly from social-community sectors, to participate in quality improvement efforts to enhance quality of and access to depression care.

CEP may have increased staff participation over RS through several mechanisms. Partnering with local programs and staff to adapt training content may have made the materials more consistent with the existing program capacities or interests, particularly for social-community settings. Although programs and staff were offered trainings, none were mandated. CEP may have increased staff participation particularly in programs with engaged leadership. In addition, CEP councils offered more training opportunities in response to community partners’ feedback.29,30 CEP's inclusion of agency staff as co-trainers may have increased ownership and trust in trainings, similar to the benefit of local opinion leaders in practice guideline implementation.50-52 The community planning groups multi-agency training plan may have been appealing to both healthcare and social-community sectors. The CEP group's development of a more intensive training plan with greater training options may have been more consistent with staff's sense of the support needed to implement depression care. More generally, community engagement principles and activities in CEP may have instilled a greater sense of ownership and commitment especially from social-community sectors not traditionally included in depression care trainings.

For both interventions, training exposure estimates may be conservative, as staff may have taken trainings back to their programs to share with staff not in attendance. The CEP Councils’ effort to develop and implement their tailored plan was substantial (5 months of biweekly meetings followed by monthly implementation meetings), but feasible given the large populations (up to 2 million people) in participating communities. Conducting the planning required co-leadership by community and academic partners experienced with applying CPPR to depression. RS also had a preparation period with expert leaders and up to 5 outreach calls or visits to each program. Future research should clarify which features of CEP relative to RS promoted provider engagement, identify potential strategies like financial incentives to enhance participation, and determine whether training participation mediated the intervention's impact on patient outcomes.

The study has several limitations. Eligible staff estimates were based on an administrator survey item and follow-up calls, while staff training participation was based on registration, logs, and attendance sheets. Given that administrator estimates were largely obtained prior to randomization, it is unlikely that there is any differential bias in estimation by intervention condition. Future work may benefit from validating administrator reports with human resource records. Generalizability of our findings may be limited as the study design and data are not designed to separate out the differential effect of community engagement from CEP training plans’ (i.e. increased hours, intensity, flexibility, breadth of training) effect on program and staff training participation. If replicated, CEP groups may offer a different set of training options with different participation effects. The study was not designed to assess whether increased training participation led to improved quality of care or whether improved quality of care led to improved client outcomes.

Conclusions

As healthcare reform implementation expands access to care for millions of Americans including many low-income Latinos and African Americans, a continuing priority will be to build capacity of under-resourced communities (e.g. Medicaid behavioral health homes, accountable care organizations) to implement evidence-based, depression quality improvement programs. 18,53-56 Our findings suggest a community engagement and planning approach to trainings as a network may increase program and staff engagement, particularly for engaging healthcare sectors and for developing staff capacity outside of healthcare (i.e. homeless-serving, social services) in minority communities with historical distrust in services and research.22-24,57-63 Future work is needed to estimate compared interventions’ comparative cost-effectiveness, replicate findings in larger samples, clarify which CEP components improve provider's depression care competencies, and whether training participation mediates intervention effects on client outcomes.

Acknowledgements

Funders: National Institute of Mental Health grant # R01MH078853, P30MH082760; National Library of Medicine grant # G08LM011058, California Community Foundation; UCLA Clinical and Translational Science Institute, National Center for Advancing Translational Science grant # UL1TR000124, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation grant #64244.

Appendix

Appendix Figure 1.

CONSORT Design of recruitment, enrollment of agencies, programs, staff.

Appendix A.

Items on Administrator Baseline Survey asking number of staff with direct client contact

| 1. Approximately how many people—both paid and volunteer—work in your organization? |

| a. Number of Paid employees ____ |

| b. Number of Volunteer workers ____ |

| 2. Approximately how many full-time equivalent (FTE) paid staff does your organization employ in each of the following categories? (If none, please write NONE or 0). |

| Psychiatrists | _____FTE |

| Psychologists (licensed or waivered) | _____FTE |

| Professional Social Workers (licensed or waivered) | _____FTE |

| Marriage and Family Therapists (licensed or waivered) | _____FTE |

| Other Mental Health Staff (e.g. occupational therapist, psychiatric nurses or technicians, etc) | _____FTE |

| (please specify)_______________________________ | |

| Substance Abuse Specialists (licensed or certified) | _____FTE |

| Physicians (excluding Psychiatrists) | _____FTE |

| Other licensed medical staff (e.g., RNs, NPs, Phys Assistants) | _____FTE |

| (please specify)_______________________________ |

Appendix B Characteristics of programs, total staff, and enrolled staff by intervention condition*

| Overall | RS | CEP | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Programs | ||||||

| Number of programs, n | 95 | 46 | 49 | |||

| South Los Angeles (vs. Metro), n, % | 52 | 54.7 | 24 | 52.2 | 28 | 57.1 |

| Service sector, n, % | ||||||

| Healthcare sectors | ||||||

| Primary care | 17 | 17.9 | 8 | 17.4 | 9 | 18.4 |

| Mental health services | 18 | 18.9 | 10 | 21.7 | 8 | 16.3 |

| Substance abuse | 20 | 21.1 | 11 | 23.9 | 9 | 18.4 |

| Social-community sectors | ||||||

| Homeless services | 10 | 10.5 | 5 | 10.9 | 5 | 10.2 |

| Community-based† | 30 | 31.6 | 12 | 26.1 | 18 | 36.7 |

| # programs >1 staff participate in kick-off conference, n, % | 45.7 | 47.4 | 22 | 44.9 | 23 | 46.9 |

| Eligible staff‡ | ||||||

| Number of total staff with client contact,¶ n | 1621 | 723 | 898 | |||

| Attend kick off conference, n, % | 104 | 6.4 | 56 | 7.7 | 48 | 5.3 |

| South Los Angeles (vs. Metro), n,% | 809 | 49.9 | 320 | 44.3 | 489 | 54.5 |

| Service sector, n, % | ||||||

| Healthcare sectors | ||||||

| Primary care | 493 | 30.4 | 201 | 27.8 | 292 | 32.5 |

| Mental health services | 290 | 17.9 | 110 | 15.2 | 180 | 20.0 |

| Substance abuse | 264 | 16.3 | 132 | 18.3 | 132 | 14.7 |

| Social-community sectors | ||||||

| Homeless services | 168 | 10.4 | 94 | 13.0 | 74 | 8.2 |

| Community-based | 406 | 25.0 | 186 | 25.7 | 220 | 24.5 |

Chi-square test was used for a comparison between the two study groups. Analysis of staff data was accounted for the design effect of the cluster randomization. p>0.05 for all comparisons between the two study groups.

Community-based programs: social services, child welfare, faith-based, food banks, parks and recreation, senior centers, barber shops, beauty salons, exercise clubs

Total staff were any administrators or providers at enrolled study programs. Study providers are defined as any individuals – volunteers and employed, professional and non-professionals with direct client contact. Total staff numbers were estimated from administrator surveys.

One provider was across intervention arms and excluded for the count.

Appendix C.

Staff participation outcomes in training activities among the subset of 70 programs that had any participation by intervention status*

| RS | CEP | Group effect | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Estimate | 95% CI | Estimate | 95% CI | t | df | p |

| Primary outcome | |||||||

| Total hours in training, mean | .46 | 0.17-0.75 | 2.47 | 1.1-3.85 | 4.1 | 69 | <.001 |

| Within type of programs | |||||||

| Healthcare programs | .58 | .20-.97 | 2.01 | .25-3.78 | 2.2 | 69 | .031 |

| Primary care | .31 | −.01 to .62 | .71 | −.05-1.47 | 1.4 | 69 | .152 |

| Mental health services | .53 | −.13 to 1.19 | 4.08 | −1.37-9.52 | 2.9 | 69 | .005 |

| Substance abuse | .43 | −.17-1.03 | 4.03 | 1.52-6.53 | 2.6 | 69 | .011 |

| Social-community programs | .27 | .07-.48 | 3.24 | 1.93-4.55 | 5.9 | 69 | <.001 |

| Homeless services | .17 | .00-.35 | 5.06 | −1.12-11.23 | 7.3 | 69 | <.001 |

| Community-based programsa | .26 | .08-.43 | 3.49 | 1.84-5.15 | 6.1 | 69 | <.001 |

| Secondary outcomes-collaborative care component | |||||||

| Any CBT Training,b % | 7.6 | 2.69-12.51 | 12.34 | 4.96-19.71 | 1.1 | 69 | .268 |

| Total hours in CBT training, mean | .19 | .04-.34 | 1.08 | .28-1.89 | 3.1 | 69 | .003 |

| Any CM training,c % | 4.57 | 1.41-7.74 | 19.36 | 9.66-29.07 | 3.5 | 69 | <.001 |

| Total hours in CM training, mean | .11 | .03-.2 | .8 | .41-1.18 | 4.7 | 69 | <.001 |

| Any med training,d % | 2.91 | −.23 to 6.04 | 8.45 | 3.86-13.04 | 2 | 69 | .053 |

| Total hours in MED training, mean | .02 | −.01 to .05 | .08 | .03-.13 | 2 | 69 | .053 |

| Any other types of training,e % | 6.85 | 3.62-10.08 | 11.15 | 4.79-17.51 | 1.4 | 69 | .177 |

| Total hours in other types of training, mean | .11 | .03-.18 | .6 | .23-.96 | 3.6 | 69 | <.001 |

Logistic regression models for binary variables or log-linear regression models for total hours adjusted for community and accounted for the design effect of the cluster randomization; full sample analyses were also controlled for sector.

social services agencies, faith-based, senior centers, parks and recreation, barber shops.

cognitive behavioral therapy.

care management.

antidepressant medication management and education.

administrator training in team building, grant writing for programs, active listening, “resiliency-class”.

Footnotes

Contributors: We thank the 28 participating agencies of the CPIC Council and their representatives: We thank Paul Koegel, PhD; Elizabeth Dixon, RN, PhD; Elizabeth Lizaola, MPH; Susan Stockdale, PhD; Peter Mendel, PhD; Mariana Horta, BA; and Dmitry Khodyakov, PhD for their support. We thank Robert Brook, MD, ScD; David Miklowitz, PhD; Ira Lesser, MD; and Loretta Jones, MA for comments on earlier drafts of the manuscript.

Presentations: The manuscript findings have not been presented.

Conflict of interest: The authors disclose that they do not have any conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R, et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2197–2223. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61689-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2163–2196. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61729-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, et al. Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, 2001: systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet. 2006;367:1747–1757. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68770-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang PS, M. L, Olfson M, Pincus HA, et al. Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:590–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang PS, Berglund P, Olfson M, et al. Failure and delay in initial treatment contact after first onset of mental disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:603–613. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams DR, Gonzalez HM, Neighbors H, et al. Prevalence and distribution of major depressive disorder in African Americans, Caribbean blacks, and non-Hispanic whites: results from the national survey of american life. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:305–315. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gonzalez HM, Vega WA, Williams DR, et al. Depression care in the United States: too little for too few. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67:37–46. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gilbody S, Bower P, Fletcher J, et al. Collaborative care for depression: a cumulative meta-analysis and review of longer-term outcomes. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2006;166:2314–2321. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.21.2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gilbody S, Whitty P, Grimshaw J, et al. Educational and organizational interventions to improve the management of depression in primary care: a systematic review. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289:3145–3151. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katon WJ, Lin EH, Von Korff M, et al. Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illnesses. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;36:2611–2620. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wagner EH. Chronic disease management: what will it take to improve care for chronic illness? Effective Clinical Practice. 1998;1:2–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Von Korff M, Gruman J, Schaefer J, et al. Collaborative Management of Chronic Illness. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1997;127:1097–1102. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-12-199712150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Von Korff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Milbank Quarterly. 1996;74:511–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Unutzer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, et al. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288:2836–2845. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.22.2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wells KB, Sherbourne CD, Schoenbaum M, et al. Five-year impact of quality improvement for depression: results of a group-level randomized controlled trial. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61:378–386. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.4.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wells KB, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, et al. Impact of disseminating quality improvement programs for depression in managed primary care: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;283:212–220. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.2.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katon W, Russo J, Lin EHB, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a multicondition collaborative care intervention: a randomized controlled trial. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2012;69:506. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.SAMSHA-HRSA Center for Integrated Health Solutions Behavioral Health Homes for People with Mental Health and Substance Use Conditions: Core Clinical Features. 2012 May; Available at: http://www.integration.samhsa.gov/integrated-care-models/health-homes.

- 19.Chung B, Jones L, Dixon EL, et al. Using a Community Partnered Participatory Research Approach to Implement a Randomized Controlled Trial: Planning the Design of Community Partners in Care. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2010;21:780. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wells KB, Jones L, Chung B, et al. Community-Partnered, Cluster-Randomized Comparative Effectiveness Trial of Community Engagment and Planning or Technical Assistance to Address Depression Disparities. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2013;28:1268–78. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2484-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miranda J, Ong MK, Jones L, et al. Community-Partnered Evaluation of Depression Services for Clients of Community-Based Agencies in Under-Resourced Communities in Los Angeles. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2013;28:1279–87. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2480-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wells KB, Jones L. Commentary: “Research” in community-partnered, participatory research. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2009;302:320–321, 2009. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones L, Meade B, Forge N. Begin your partnership: the process of engagement. Ethnicity and Disease. 2009;19:S6–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones L, Wells K. Strategies for academic and clinician engagement in community-participatory partnered research. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2007;297:407–410. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.4.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chung B, Ong M, Ettner S, et al. 12-Month Outcomes of Community Engagement Versus Technical Assistance for Depression Quality Improvement: A Partnered, Cluster, Randomized, Comparative Effectiveness Trial. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2014;161:S23–34. doi: 10.7326/M13-3011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Springgate BF, Wennerstrom A, Meyers D, et al. Building community resilience through mental health infrastructure and training in post-Katrina New Orleans. Ethnicity and Disease. 2011;21:S1-20–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wennerstrom A, Vannoy SD, 3rd, Allen CE, et al. Community-based participatory development of a community health worker mental health outreach role to extend collaborative care in post-Katrina New Orleans. Ethnicity and Disease. 2011;21:S1–45-51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bentham W, Vannoy SD, Badger K, et al. Opportunities and challenges of implementing collaborative mental health care in post-Katrina New Orleans. Ethnicity and Disease. 2011;21:S1–30-37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khodyakov D, Mendel P, Dixon E, et al. Community Partners in Care: Leveraging Community Diversity to Improve Depression Care for Underserved Populations. International Journal of Diversity in Organizations Communities Nations. 2009;9:167–182. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khodyakov D, Sharif MZ, Dixon EL, et al. An Implementation Evaluation of the Community Engagement and Planning Intervention in the CPIC Depression Care Improvement Trial. Community Mental Health Journal. 2014;50:312–24. doi: 10.1007/s10597-012-9586-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.California Pan-Ethnic Health Network . Los Angeles County multicultural health fact sheet. California Pan-Ethnic Health Network; Los Angeles: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stockdale SE, Tang L, Pulido E, et al. Sampling and Recruiting Community-based Programs for a Cluster-Randomized, Comparative Effectiveness Trial Using Community-Partnered Participation Research: Challenges, Strategies and Lessons Learned from Community Partners in Care. Health Promotion, Practice. doi: 10.1177/1524839915605059. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mendel P, Ngo VK, Dixon E, et al. Partnered evaluation of a community engagement intervention: use of a kickoff conference in a randomized trial for depression care improvement in underserved communities. Ethnicity and Disease. 2011;21:S1–78-88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bluthenthal RN, Jones L, Fackler-Lowrie N, et al. Witness for Wellness: preliminary findings from a community-academic participatory research mental health initiative. Ethnicity and Disease. 2006;16:S18–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wells KB, Staunton A, Norris KC, et al. Building an academic-community partnered network for clinical services research: the Community Health Improvement Collaborative (CHIC). Ethnicity and Disease. 2006;16:S3–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chung B, Jones LJ, Booker T, et al. Using Community Arts Events to Enhance Collective Efficacy and Community Engagement to address Depression in an African American Community. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99:237–44. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.141408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.United States Census Bureau . Los Angeles County. California: http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/06/06037.html. Accessed June 23, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miranda J, Chung JY, Green BL, et al. Treating depression in predominantly low-income young minority women. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;290:57–65. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rubenstein LV, Jackson-Triche M, Unutzer J, et al. Evidence-based care for depression in managed primary care practices. Health Affairs (Millwood) 1999;18:89–105. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.18.5.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Community Partners in Care Depression Care Toolkit. www.communitypartnersincare.org. Accessed 04/01/2013.

- 41.Afifi A, Kotlerman J, Ettner S, et al. Methods for improving regression analysis for skewed continuous or counted responses. Annual Review of Public Health. 2007;28:95–111. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.082206.094100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Manning WG. The logged dependent variable, heteroscedasticity, and the retransformation problem. Journal of Health Economics. 1998;17:283–295. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(98)00025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Duan N, Manning WG, Morris CN, et al. A comparison of alternative models for the demand of medical care. Journal of Business and Economics Statistics. 1983;1:115–126. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Duan N. Smearing estimate: a nonparametric retransformation method. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1983;78:605–610. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bell RM, McCaffrey DF. Bias reduction in standard errors for linear regression with multi-stage samples. Survey Methodology. 2002;28:169–182. [Google Scholar]

- 46.McCaffrey DF, Bell RM. Improved hypothesis testing for coefficients in generalized estimating equations with small samples of clusters. Statistics in Medicine. 2006;25:4081–4098. doi: 10.1002/sim.2502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Binder DA. On the variances of asymptotically normal estimators from complex surveys. Internataional Statistical Review. 1983:279–292. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seng AC, Prinz RJ, Sanders MR. The role of training variables in effective dissemination of evidence-based parenting interventions. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion. 2006;8:20–28. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Unutzer J, Chan Y-F, Hafer E, et al. Quality improvement with pay-for-performance incentives in integrated behavioral health care. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102 doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Proctor EK, Landsverk J, Aarons G, et al. Implementation research in mental health services: An emerging science with conceptual, methodological, and training challenges. Administration and Policy in Mental Health Services Research. 2009;36:24–34. doi: 10.1007/s10488-008-0197-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schoenwald SK, Hoagwood K. Effectiveness, transportability, and dissemination of interventions: what matters when? Psychiatric Services. 2001;52:1190–1197. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.9.1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rogers EM. Diffusion of Innovations. 5th ed. Free Press; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services The Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act. 2008 http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Health-Insurance-Reform/HealthInsReformforConsume/index.html?redirect=/HealthInsReformforConsume/04_TheMentalHealthParityAct.asp.

- 54.US Department of Health and Human Services Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. http://www.healthcare.gov/law/full/index.html.

- 55.Institute of Medicine . Primary Care and Public Health: Exploring the Integration to Improve Population Health. The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Landon BE, Grumbach K, Wallace PJ. Integrating public health and primary care systems: potential strategies from an IOM report. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2012;308:461–462. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.8227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gamble VN. Under the shadow of Tuskegee: African Americans and health care. American Journal of Public Health. 1997;87:1773–1778. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.11.1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jones JH. Bad blood: The Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment. Free Press; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Institute of Medicine . Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care (full printed version) The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, editors. Methods in Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, et al. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wallerstein N, Duran B. Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: the intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:S40–S46. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.184036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health: From Process to Outcomes. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 2003. [Google Scholar]