Abstract

A feasibility study was performed to evaluate the immunological efficacy and safety of a personalized peptide vaccine (PPV) for cervical cancer patients who have received platinum-based chemotherapy. A total of 24 patients with standard chemotherapy-resistant cervical cancer, including 18 recurrent cases, were enrolled in this study and received a maximum of 4 peptides based on HLA-A types and IgG levels to the vaccine candidate peptides in pre-vaccination plasma. The parental protein expression of most of the vaccine peptides was confirmed in the cervical cancer tissues. No vaccine-related systemic grade 3 or 4 adverse events were observed in any patients. Due to disease progression, 2 patients failed to complete the first cycle of vaccinations (sixth vaccination). Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) or IgG responses specific for the peptides used for vaccination were augmented in half of cases after the first cycle. The median overall survival was 8.3 months. The clinical responses of the evaluable 18 cases consisted of 1 case with a partial response and 17 cases with disease progression; the remaining 6 cases were not evaluable. Performance status, injection site skin reaction and circulating PD-1+CD4+ T-cells were significantly prognostic of overall survival, and multivariate analysis also indicated that the performance status and circulating PD-1+CD4+ T-cells were prognostic. Because of the safety and immunological efficacy of PPV and the possible prolongation of overall survival, further clinical trials of PPV at a larger scale in advanced or recurrent cervical cancer patients who have received prior platinum-based chemotherapy are recommended.

Keywords: Cervical cancer, cytotoxic T-lymphocytes, epitopes, peptide vaccine, personalized medicine

Cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer in women in the world.1 Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is the main cause of cervical cancer and prophylactic vaccines have been developed and are expected to decrease the incidence of this disease. However, the prognosis of patients with advanced or recurrent cervical cancer is still poor, and the mortality rate remains high. The standard treatment for inoperable and irradiated advanced or recurrent cervical cancer is platinum-based chemotherapy.2 Recently, prolongation of survival by chemotherapy plus bevacizumab in patients with advanced or recurrent cervical cancer was reported.3 However, the benefit of this second-line therapy has not been proved. Thus, it is important to develop new therapeutic approaches, including cancer vaccines and molecular targeting therapy.

In previous studies, we reported the development of a personalized peptide vaccine (PPV), in which the vaccine peptides are selected and administered from a panel of 31 candidate peptides based on the HLA types and pre-vaccination IgG levels to each peptide.4,5 Our previous studies suggest that overall survival (OS) is prolonged in PPV-treated patients with various kinds of advanced cancer who fail to respond to standard chemotherapy.4–9 A survival benefit in the PPV group was further confirmed in a randomized controlled trial of PPV in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer.10 We have conducted a clinical study to evaluate the feasibility of PPV in advanced or recurrent cervical cancer patients who have received prior platinum-based chemotherapy.

Materials and Methods

Immunohistochemical analysis

Tumor tissue specimens from 10 patients with cervical cancer who were not being treated with PPV were used for the analysis. Sections (4 μm) of paraffin-embedded tissue specimens were stained using fully automated protocols on a BenchMark XT platform (Ventana Automated Systems, Tucson, AZ, USA) with rabbit polyclonal antibodies (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and an iVIEW DAB Detection Kit (Ventana).

Patients

Patients were eligible for participation in the present study if they were: between 20 and 80 years of age; had received a histological diagnosis of cervical cancer; had received prior platinum-based chemotherapy; showed positive IgG responses to at least 2 of the HLA-class I-matched vaccine candidate peptides; had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0 or 1; had a positive status for HLA-A2, -A3, -A11, -A24, -A26, -A31 or -A33; had a life expectancy of 12 weeks or more; and had adequate hematologic, renal and hepatic functions. Patients with a history of severe allergic reactions, an acute infection, or pulmonary, cardiac or other systemic diseases were excluded. Patients who were pregnant or nursing, or had other conditions the clinicians believed made them inappropriate for enrollment, were excluded from the study.

Clinical protocol

This study (UMIN Clinical Trials Registry ID: 000001847 and 000003082) investigated the feasibility of PPV in patients with advanced or recurrent cervical cancer who had received prior platinum-based chemotherapy. The safety and immunological effects of PPV have been established in previous clinical studies.6–9 The peptides were manufactured in accordance with Good Manufacturing Practice by the PolyPeptide Laboratories (San Diego, CA, USA) or the American Peptide Company (Vista, CA, USA). Up to 4 peptides for vaccination in each patient were selected from a panel of 31 candidate peptides based on the HLA types and pre-vaccination IgG levels against each peptide as described previously.6–9 Each peptide (3 mg) was emulsified with Montanide ISA51VG (Seppic, Paris, France) and injected s.c. once a week for 6 consecutive weeks then once every 2 weeks. Concurrent chemotherapy was permitted during the vaccination for patients who could tolerate it. Complete blood counts and serum biochemistry profiles were examined at every sixth vaccination. The National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 4.0 (CTCAE Ver4) were used for assessment of adverse events. The tumor responses were adjudicated with the use of the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST). The Kurume University Ethical Committee approved the protocol of the study. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Detection of immune responses

A Luminex system (Luminex, Austin, TX, USA) was used for detection of IgG, and the IgG levels were expressed as fluorescence intensity units (FIU) and IgG score.9 The detection limit of the assay was 10 FIU. An IFN-□ ELISPOT assay was used for the detection of CTL as previously described.9,11 If the mean IgG levels or antigen-specific ELISPOT numbers of quadruplicate assay were more than doubled with statistical significance, the response was considered augmented. More precise criteria of an augmented response of IgG or CTL were described in our previous reports.9,11

Flow cytometry

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (1 × 105) were stained with the following antibodies in the presence of 20% heat-inactivated human AB serum: anti-CD4-FITC, anti-CD279 (PD-1)-APC or APC-labeled mouse IgG1 (k; MOPC-21), all from BD Biosciences (Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). The cells were analyzed on a FACS Canto II with FACS Diva software (BD Biosciences).

Statistical analysis

Overall survival time was calculated from the date of the first vaccination until the date of death or the last contact alive, and was plotted using the Kaplan–Meier method. The statistical significance of the survival curves of individual variables was analyzed using the log-rank test. Univariate and multivariate analyses with the Cox proportional hazard model were used for evaluation of predictive factors for OS. Differences were considered significant when P < 0.05. The JMP Pro11 software package (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) was used for the statistical analyses.

Results

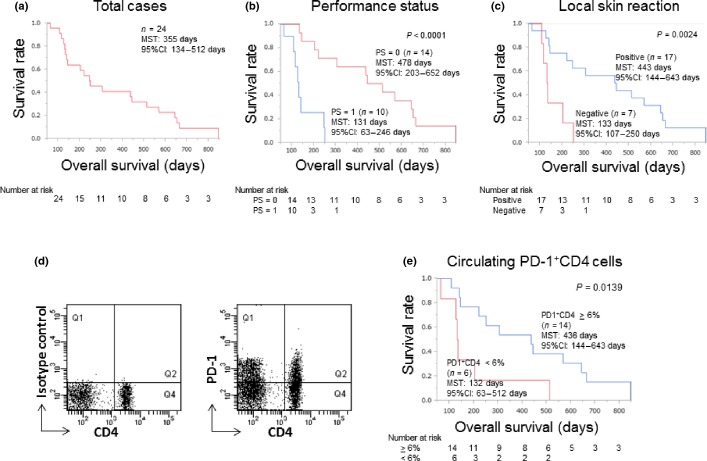

Expression of tumor-associated antigens in cervical cancer tissues

The expression of 15 parental proteins of 31 vaccine candidate peptides in tumor tissue specimens from 10 patients with cervical cancer who were not being treated with PPV was examined by immunohistochemistry. Eleven parental proteins (Cyclophilin-B, ppMAPkkk/WNK2, WHSC2, HNRPL, UBE2V, SART2, SART3, EGF-R, MRP3, EZH2 and PTHrP) were detectable in the cancer cells in the primary tumor tissues (Table1). In contrast, three prostate-related antigens (PSA, PAP and PSMA), and p56lck, which are preferentially expressed in metastatic cancers, were not detectable in any of the primary tumor tissues tested. The expression of p56lck in metastatic tumor cells in the lymph nodes from 7 patients was further examined, but no expression was confirmed. Expression of EZH2, HNRPL, PTHrP, SART2 and SART3 was also observed in the surrounding non-cancerous tissues from the patients, in agreement with previous reports regarding the nature of these antigens (these are ubiquitous antigens expressed in both malignant and normal cells).12 The other antigens were not detected in the normal tissues. Representative staining patterns are shown in Figure1. It should be noted that 5 cases in this clinical trial received 1 or more peptides derived from one or more of the three prostate-related antigens and 17 cases received p56lck-derived peptides, because the clinical study had started before the immunohistochemical results were obtained. Further studies examining the expression of these molecules in cervical cancer cells are now in progress.

Table 1.

Tumor antigen expression in the primary and the metastatic tumor tissues†

| Sample donor | Expression in the primary tumor tissue | Expression in the metastatic lymph node | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p56lck | HNRPL | PSA | Cyclophilin B | MRP3 | PAP | SART2 | WHSC2 | PSMA | PTHrP | ppMAPkkk | SART3 | EGF-R | UBE2V | EZH2 | p56lck | MRP3 | |

| 1 | − | +++ | − | + | − | − | +++ | +++ | − | +++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | − | − |

| 2 | − | +++ | − | − | − | + | +++ | + | − | +++ | + | + | ++ | + | +++ | − | − |

| 3 | − | +++ | − | − | − | − | +++ | +++ | − | +++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | + | +++ | nd | nd |

| 4 | − | +++ | − | − | − | − | +++ | +++ | − | +++ | + | + | ++ | + | +++ | − | − |

| 5 | − | +++ | − | − | − | − | ++ | ++ | − | +++ | ++ | ++ | +++ | + | +++ | nd | nd |

| 6 | − | +++ | − | ++ | + | − | +++ | +++ | − | +++ | ++ | +++ | − | ++ | +++ | − | − |

| 7 | − | +++ | − | − | + | − | +++ | +++ | − | +++ | ++ | +++ | − | + | +++ | nd | nd |

| 8 | − | +++ | − | + | ++ | − | +++ | +++ | − | +++ | ++ | +++ | + | ++ | ++ | − | ++ |

| 9 | − | +++ | − | ++ | − | − | +++ | +++ | − | +++ | + | ++ | − | − | − | − | + |

| 10 | − | +++ | − | ++ | + | − | +++ | +++ | − | +++ | + | +++ | + | ++ | +++ | − | − |

| Number of positive cases (>2 + ) | 0 | 10 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 10 | 9 | 0 | 10 | 6 | 8 | 5 | 4 | 9 | 0 | 1 |

| Positive % | 0 | 100 | 0 | 30 | 10 | 0 | 100 | 90 | 0 | 100 | 60 | 80 | 50 | 40 | 90 | 0 | 14 |

Antigen expression was determined by immunohistochemical analysis. ++ and +++ are considered as positive. nd, not determined.

Figure 1.

Expression profile of parental proteins of vaccine peptides. Tumor specimens from 10 cervical cancer patients were subjected to immunohistochemical analysis. Representative staining patterns of cancerous (a–k) and non-cancerous (l–p) tissues are shown.

Patient characteristics

A total of 24 patients with advanced or recurrent cervical cancer were enrolled in this study from June 2006 through December 2013. Baseline characteristics of the patients are shown in Table2. Squamous cell carcinoma was the most common histology (n = 12), and the other types were as follows: adenocarcinoma (n = 7), adenosquamous carcinoma (n = 3) and small cell carcinoma (n = 2). All patients had previously received platinum-based chemotherapy and underwent standard chemotherapy against cervical cancer before enrollment. The performance status at the time of enrollment was grade 0 (n = 14) or grade 1 (n = 9). Of 24 cases, 12 completed two cycles of vaccinations. The median vaccination dose was 11.5 (95% CI: 3–26).

Table 2.

Patients' characteristics (n = 24)

| Parameters | N |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Median (range) | 55 years (32–68 years) |

| Histology | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 12 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 7 |

| Adenosquamous cell carcinoma | 3 |

| Small cell carcinoma | 2 |

| Performance status | |

| 0 | 14 |

| 1 | 10 |

| Prior radical radiation | |

| Yes | 15 |

| No | 9 |

| Prior chemotherapy | |

| 0–2 regimens | 15 |

| ≥3 regimens | 9 |

| Clinical stage | |

| Advanced | 5 |

| Recurrence | 19 |

Toxicities

All adverse events are shown in Table3, whether or not they were attributed to the vaccine therapy. Treatment-related grade 1 or 2 dermatological reaction was observed at the injection site in 17 cases. The grade 3 or 4 adverse events were anemia (grade 3: n = 3), leukocytopenia (grade 3: n = 2), neutropenia (grade 3: n = 1; grade 4: n = 1), creatinine elevation (grade 3: n = 1) and dyspnea (grade 3: n = 1). All of these grade 3 or 4 adverse events were considered to be attributed to the concurrent chemotherapy, rather than directly associated with the vaccinations, based on the assessment of an independent safety evaluation committee.

Table 3.

Toxicities

| CTCAE v4.0 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | |

| Injection site reaction | 7 | 10 | ||

| Anemia | 1 | 3 (3)† | ||

| Leukocytopenia | 2 (2) | |||

| Neutropenia | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | ||

| Lymphopenia | 2 | |||

| Hypoalbuminemia | 5 | 4 | ||

| AST elevation | 2 | |||

| Creatinine elevation | 1 | 1 | ||

| Dyspnea | 1 | |||

| Bleeding, upper respiratory tract | 1 | |||

| Fatigue | 1 | |||

| Vesicovaginal fistula | 1 | |||

Number in the parentheses indicates chemotherapy related adverse events.

Immune responses to the vaccinated peptides

Vaccine peptide-specific IgG and CTL responses were evaluated in peripheral blood samples of the patients (Table S1). A total of 24 blood samples at pre-vaccination and a total of 22 blood samples at the sixth vaccinations were subjected to the assay because 2 patients failed to complete the first cycle of vaccination (sixth vaccination) due to disease progression.

A total of 12 of 22 (54.5%) patients showed augmentation of the IgG responses for at least one of the vaccinated peptides after the sixth vaccination. The IgG responses to all 31 vaccine candidate peptides were measured in all patients in order to examine how the vaccination spread epitopes. Epitope spreading, that is, an increase in the numbers of peptides reactive to IgG after the sixth vaccination, was observed in 7 patients.

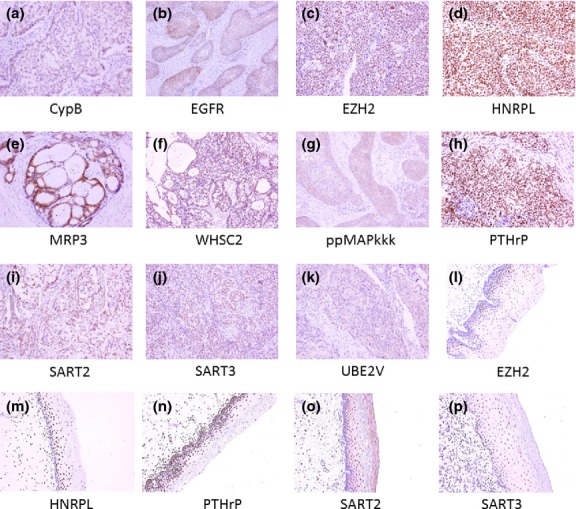

Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses specific for the peptides that were used for the vaccination were evaluated by IFN-□ ELISPOT assay. Detectable levels of CTL responses were observed in only 3 of 24 (12.5%) patients before vaccination. After the sixth vaccination, the CTL responses were augmented in 11 of 22 (50%) patients. Representative well images of ELISPOT assay are shown in Figure2.

Figure 2.

Representative well images of ELISPOT assay. HIV-A2 peptide was used as a negative control. CEF is a cocktail of CMV, EBV and flu peptides and was used as a positive control.

Relationship between clinical and immunological findings and overall survival

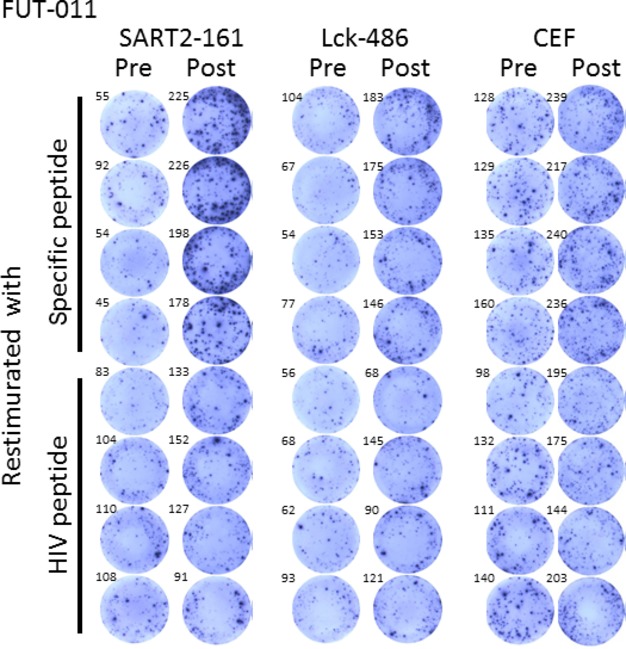

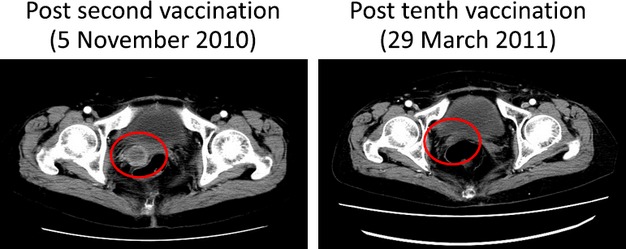

Clinical responses of the 18 patients who had measurable lesions and whose radiological findings were available both before and after the vaccination were as follows: partial response (PR) in 1 case and progressive disease (PD) in 17 cases. CT images of the PR case are shown in Figure3. We further analyzed the correlation between the clinical findings or immunological responses and OS using a Kaplan–Meier plot (Fig.4). The median overall survival time (MST) of the 24 recurrent patients was 250 days (8.3 months; Fig.4a). Better performance status (PS) of patients before vaccination was correlated with OS with high significance (P < 0.0001 by the log-rank test; Fig.4b). Namely, the PS 0 group expressed longer OS than the PS 1 group. The MST of the PS 0 group was 478 days; that of the PS 1 group was 131 days. Similarly, the local skin reaction at the injection site after the first cycle of vaccination was significantly correlated with OS (P = 0.0024 by the log-rank test; Fig.4c). Namely, the skin reaction-positive group expressed longer OS than the negative group. The MST of the positive group was 443 days; that of the negative group was 133 days.

Figure 3.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography computed tomography images of the partial response case (FUT-011) obtained after the second vaccination (8 days from the first vaccination) and tenth vaccination.

Figure 4.

Kaplan–Meier analysis of overall survival (OS). (a) A survival curve for all the patients (n = 24) enrolled in this study is shown. The median survival time (MST) was 355 days. (b) The OS of patients with PS = 0 (red line, MST = 478 days) was significantly longer than that of patients with PS = 1 (blue line, MST = 131 days; P = 0.0001, log-rank test). (c) The OS of the injection-site skin reaction-positive group (blue line, MST = 443 days) was significantly longer than that of the negative group (red line, MST = 133 days; P = 0.0024, log-rank test). (d) A representative staining pattern of PD-1+CD4+ T-cells is shown. (e) The OS of the group with a relatively high content (>6%) of PD-1+CD4+ (blue line, MST = 436 days) was significantly longer than that of the group with low content (<6%; red line, MST = 132 days; P = 0.0139, log-rank test).

We previously reported that circulating PD-1+CD4+ T-cell content before vaccination was correlated with good prognosis in patients with advanced or recurrent non-small cell lung cancer. In the present study, the presence of PD-1+CD4+ T-cells in PBMC was confirmed in cervical cancer patients (Fig.4d). Positive correlation between the relative contents of PD-1+CD4+ T-cells before vaccination and OS was also confirmed in this study (P = 0.0139 by the log-rank test; Fig.4e).

The Cox proportional hazards model was used to determine whether clinical findings or immunological responses could be prognostic factors for OS (Table4). Univariate analysis revealed positive correlations between OS and each of pre-vaccination better PS (PS = 0; P = 0.0006, HR = 0.120, 95% CI: 0.031–0.398), skin reaction at the injection sites (P = 0.0082, HR = 0.192, 95% CI: 0.057–0.637) and relative contents of circulating PD-1+CD4+ T-cells were positively correlated with OS (P = 0.044, HR = 0.803/unit, 95% CI: 0.631–0.995, respectively). Multivariate analysis showed that the pre-vaccination better PS and relative contents of circulating PD-1+CD4+ T-cells were significant factors for longer OS (P = 0.0049 and P = 0.0304, respectively), and the combination of these two factors is a stronger prognostic factor than either factor alone. Neither an increase in CTL nor an increase in IgG responses was significantly correlated with the OS.

Table 4.

Cox's proportional hazard analysis of clinical and immunological data with OS (n = 24)

| Factors | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Age (≥55 years) | 0.649 (0.259–1.579) | 0.338 | ||

| Histology (SCC) | 0.503 (0.199–1.235) | 0.132 | ||

| Prior radical radiotherapy | 0.614 (0.252–1.533) | 0.288 | ||

| Number of prior chemotherapy regimens (≥3) | 1.196 (0.406–3.203) | 0.730 | ||

| Concurrent chemotherapy | 0.694 (0.241–1.773) | 0.457 | ||

| Performance status (0) | 0.120 (0.031–0.398) | 0.0006* | 0.091 (0.014–0.489) | 0.0049* |

| Lymphocyte number (≥1200) | 2.446 (0.972–5.996) | 0.057 | ||

| Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (≥2.8 = median) | 0.425 (0.143–1.141) | 0.090 | ||

| Hypoalbuminemia | 1.339 (0.519–3.273) | 0.531 | ||

| Skin reaction at the injection sites | 0.192 (0.057–0.637) | 0.0082* | 1.008 (0.204–5.042) | 0.991 |

| Increase in CTL responses | 0.462 (0.175–1.256) | 0.126 | ||

| Increase in IgG responses | 0.879 (0.353–2.289) | 0.785 | ||

| Epitope spreading | 1.512 (0.549–3.902) | 0.407 | ||

| PD-1+CD4+ T-cells (%) | 0.803 (0.631–0.995) | 0.044* | 0.764 (0.580–0.976) | 0.0304* |

Statistically significant, P < 0.05. CI, confidence interval; CTL, cytotoxic T lymphocytes; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

Discussion

The prognosis of cervical cancer patients who have received platinum-based chemotherapy remains very poor, with an MST of 3.6–8.2 months.13–17 Therefore, new innovative therapies are needed for the treatment of cervical cancer patients who have received platinum-based chemotherapy. We conducted a phase II study of PPV for cervical cancer patients who had received prior platinum-based chemotherapy. Among the 24 patients enrolled in this study, 8 received concomitant chemotherapy during the vaccination period and the remaining patients, who could not tolerate concomitant chemotherapy, received PPV monotherapy. The MST of the 24 cases of cervical cancer treated with PPV was 8.3 months and the median number of prior chemotherapy regimens was 2 (range 1–8). This MST value was close to the historical control values for cervical cancer patients who have received platinum-based chemotherapy in our institution (the historical MST was 9.2 months). It should be noted that the historical data were for patients who had received only one regimen of platinum-based chemotherapy and did not include the data of patients who had received two or more prior regimens. In this study, the MST of 6 cases treated with PPV who received only one prior regimen was 11.5 months. These results suggest that PPV has the potential to prolong the OS of platinum-based chemotherapy-treated patients with cervical cancer.

Our previously conducted trials of PPV in various types of cancers also confirmed its safety.6–10,18,19 PPV toxicity consisted mainly of skin reactions at the injection sites.

Identification of biomarkers to predict the overall survival is important to improve the clinical efficacy of PPV in patients with cervical cancer.20,21 Immunological responses to the vaccinated peptides have been reported to be good predictors of OS.18,19 Increased IgG and CTL responses were observed in 54.5 and 50% of patients at the sixth vaccination, respectively. These positive response rates after the first cycle of vaccination were similar to the results of previous studies.6–10,18,19 Recently we found that PD-1 expression on the circulating CD4+ T-cells before vaccination was positively correlated with OS in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients treated with PPV,22 and, thus, in this study we examined the PD-1 expression on the circulating CD4+ T-cells before vaccination; Kaplan–Meier analysis confirmed that the same positive correlation existed in our patients with cervical cancer. At the present time it is unclear why circulating PD-1+CD4+ cell content correlates with good prognosis. Our previous study showed that the majority of circulating PD-1+CD4+ T-cells expressed the CD45RA−CCR7− effector-memory phenotype and were not exhausted T-cells.21 A PD-1+ population was also found in CD4− cells (Fig.4d) and the content of the PD-1+CD4− cells was also positively correlated with OS (data not shown). This seemed to contradict our previous finding that the content of PD-1+CD8+ cells was negatively correlated with OS in NSCLC patients.22 The CD4− population contained CD8+ cells as well as B cells and NK cells. In the present study, we could not identify which cells contributed to this issue due to the limitation of blood samples. Further study of this subject is necessary.

Univariate analysis revealed that the pre-vaccination better performance status, skin reaction at the injection sites and pre-vaccination relative contents of circulating PD-1+CD4+ T-cells were correlated with longer OS, and the other factors, including previously reported prognostic factors in PPV, such as lymphocyte number/frequency, albumin, CTL response, IgG response and epitope spreading,9,23,24 were not correlated with the prognosis in this study. Concurrent chemotherapy was also not correlated with OS, although the PR case received concurrent chemotherapy. Multivariate analysis showed that the pre-vaccination better performance status and relative contents of circulating PD-1+ CD4+ T-cells were significant factors for longer OS.

In conclusion, a feasibility study of PPV for patients with advanced or recurrent cervical cancer who had received prior platinum-based chemotherapy was performed. Boosting of the CTL or IgG responses specific for the vaccine peptides was observed in approximately half of patients after the first cycle of vaccination without any vaccine-related systemic adverse events. Because of the safety of PPV and the possible prolongation of OS, a clinical trial of PPV in advanced or recurrent cervical cancer patients who have received prior platinum-based chemotherapy is merited.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by grants from the Private University Strategic Research Foundation Support Program of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (MEXT), and Sendai Kosei Hospital.

Disclosure Statement

Yamada is a board member of the Green Peptide Co. The other authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article:

Table S1. Immunological responses and clinical outcome of each patient.

References

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. Globocan 2012: Estimated cancer incidence, mortality and prevalence worldwide in 2012. [Cited 22 January 2015.] Available from URL: http://globocan.iarc.fr/Pages/fact_sheets_cancer.aspx.

- Leath CA, III, Straughn JM., Jr Chemotherapy for advanced and recurrent cervical carcinoma: results from cooporative group trials. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;129:251–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tewari KS, Sill MW, Long HJ, III, et al. Improved survival with Bevacizumab in advanced cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:734–43. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1309748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh K, Yamada A. Personalized peptide vaccines: a new therapeutic modality for cancer. Cancer Sci. 2006;97:970–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2006.00272.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasada T, Yamada A, Noguchi M, Itoh K. Personalized Peptide vaccine for treatment of advanced cancer. Curr Med Chem. 2014;21:2332–45. doi: 10.2174/0929867321666140205132936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattori T, Mine T, Komatsu N, et al. Immunological evaluation of personalized peptide vaccination in combination with UFT and UZEL for metastatic colorectal carcinoma patients. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2009;58:1843–52. doi: 10.1007/s00262-009-0695-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagimoto H, Shiomi H, Satoi S, et al. A phase II study of personalized peptide vaccination combined with gemcitabine for non-resectable pancreatic cancer patients. Oncol Rep. 2010;24:795–801. doi: 10.3892/or_00000923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terasaki M, Shibui S, Narita Y, et al. Phase I trial of a personalized peptide vaccine for patients positive for human leukocyte antigen-A24 with recurrent or progressive glioblastoma multiforme. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:337–44. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.7499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawano K, Tsuda N, Matsueda S, et al. Feasibility study of personalized peptide vaccination for recurrent ovarian cancer patients. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2014;36:224–36. doi: 10.3109/08923973.2014.913617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi M, Kakuma T, Uemura H, et al. A randomized phase II trial of personalized peptide vaccine plus low dose estramustine phosphate (EMP) versus standard dose EMP in patients with castration resistant prostate cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2010;59:1001–9. doi: 10.1007/s00262-010-0822-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu N, Shichijo S, Maeda Y, et al. Measurement of interferon-gamma by high-throughput fluorometric microvolume assay technology system. J Immunol Methods. 2002;263:169–76. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(02)00037-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi M, Sasada T, Itoh K. Personalized peptide vaccination: a new approach for advanced cancer as therapeutic cancer vaccine. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2013;62:919–29. doi: 10.1007/s00262-012-1379-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose PG, Blessing JA, Arseneau J. Phase II evaluation of altertamine for advanced and recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol. 1996;62:100–2. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1996.0196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bookman MA, Blessing JA, Hanjani P, Herzog TJ, Andersen WA. Topotecan in squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix: a phase II study of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. Gynecol Oncol. 2000;77:446–9. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2000.5807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose PG, Blessing JA, Buller RE, Mannel RS, Webster KD. Prolonged oral etoposide in recurrent or advanced non-squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;89:267–70. doi: 10.1016/s0090-8258(03)00079-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilder RJ, Blessing J, Cohn DE. Evaluation of gemcitabine in previously treated patients with non-squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix: a phase II study of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;96:103–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monk BJ, Sill MW, Burger RA, Gray HJ, Buekers TE, Roman LD. Phase II trial of bevacizumab in the treatment of persistent or recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1069–74. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.9043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mine T, Sato Y, Noguchi M, et al. Humoral responses to peptides correlate with overall survival in advanced cancer patients vaccinated with peptides based on pre-existing, peptide-specific cellular responses. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:929–37. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-1117-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi M, Mine T, Komatsu N, et al. Assessment of immunological biomarkers in patients with advanced cancer treated by personalized peptide vaccination. Cancer Biol Ther. 2011;10:1266–79. doi: 10.4161/cbt.10.12.13448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Disis ML. Immunologic biomarkers as correlates of clinical response to cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2011;60:433–42. doi: 10.1007/s00262-010-0960-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoos A, Eggermont AM, Janetzki S, et al. Improved endpoints for cancer immunotherapy trials. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:1388–97. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waki K, Yamada T, Yoshiyama K, et al. PD-1 expression on peripheral blood T-cell subsets correlates with prognosis in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Sci. 2014;105:1229–35. doi: 10.1111/cas.12502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yutani S, Komatsu N, Matsueda S, et al. Juzentaihoto failed to augment antigen-specific immunity but prevented deterioration of patients' conditions in advanced pancreatic cancer under personalized peptide vaccine. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:981717. doi: 10.1155/2013/981717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kibe S, Yutani S, Motoyama S, et al. Phase II Study of personalized peptide vaccination for previously treated advanced colorectal cancer. Cancer Immunol Res. 2014;2:1154–62. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Immunological responses and clinical outcome of each patient.