Abstract

Background

To evaluate the cardioprotective effects of sevoflurane versus propofol anesthesia in patients undergoing cardiac surgery.

Methods

Studies were retrieved through searching several databases. Study quality was evaluated by Jadad scale. Meta-analysis was performed with RevMan5.0 software. Publication bias was tested by funnel plot.

Results

As a result, 15 studies were included. Compared with propofol, sevoflurane anesthesia significantly improved postoperative (WMD (weighted mean difference) = 0.62, 95% CI: 0.33 to 0.92; P < 0.0001) and postoperative 12 hour cardiac index (WMD = 0.18, 95% CI: 0.03 to 0.33; P = 0.02), postoperative cardiac output (WMD = 1.14, 95% CI: 0.74 to 1.54; P < 0.00001), and reduced postoperative 24 hour cardiac troponin I concentration (WMD = -0.86, 95% CI:-1.49 to -0.22; P = 0.008), postoperative inotropic drug usage (OR (odds ratio) = 0.31, 95% CI: 0.22 to 0.44; P < 0.00001), vasoconstrictor drug usage (OR = 0.30, 95% CI:0.21 to 0.43; P < 0.00001), ICU stay (WMD = -15.53, 95% CI: -24.29 to -6.58; P = 0.0007) and a trial fibrillation incidence (OR = 0.25, 95% CI: 0.07 to 0.85; P = 0.03). However, no significant differences were found in other indexes. Subgroup analysis indicated the similar results.

Discussion

The sevoflurane-induced cTnI reduction is associated with lower incidence of late adverse cardiac events, accounting for its roles in cardiac protection. Several limitations existed such as the small sample size and the lack use of blind design.

Conclusions

Sevoflurane may exhibit a more favorable cardioprotective effect during cardiac surgery than propofol.

Keywords: Sevoflurane, Propofol, Cardiac surgery, Cardioprotective effect, Meta-analysis

Background

Myocardial injury is a common complication in patients undergoing cardiac surgery, which can result in delayed recovery, organ failure, increased hospital length of stay, and mortality [1, 2]. To protect the myocardium from injury related to cardiac surgery, several approaches have been postulated, such as inhalation anesthetic preconditioning [3].

Volatile anesthetics have been suggested to contribute to myocardial protection through a preconditioning effect on the myocardium. The mechanisms involved in the protective effect of volatile anesthetic regimens are opening of mitochondrial KATP channels, activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase, and an increase in mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. All these mechanisms account for decreased cytosolic and mitochondrial calcium loading [4–6]. A meta-analysis showed that volatile anesthetics, including sevoflurane, have beneficial effects on reducing morbidity and mortality, and thus play a cardioprotective effect on patients after cardiac surgery [7]. Intravenous anesthetics, such as propofol, are also reported to have a cardioprotective effect. This includes markedly decreasing the size of myocardial infarcts, lowering troponin release, and decreasing the rate of mortality after cardiac surgery [6, 8, 9]. A more recent study provided evidence that sevoflurane provides slightly better protection of the mitochondrial outer membrane than propofol in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass [10]. However, which anesthetic is more favorable after cardiac surgery is controversial [11–13]. Recently published studies might provide additional information about the clinical outcomes of sevoflurane and propofol. Therefore, the two drugs’ cardioprotective effect on patients should be re-evaluated using powerful statistical analysis tools. Therefore, we performed a meta-analysis to compare the cardioprotective effects of sevoflurane and propofol on patients undergoing cardiac surgery. This information could provide a basis for evidence-based medicine in clinical practice.

Methods

Search strategy

We applied the PRISMA guidelines for the reporting of systematic reviews and meta-analyses to carry out this meta-analysis [14].

We retrieved literature on the effects of sevoflurane or propofol on myocardial protection by searching MEDLINE, the Cochrane Library, and EMBASE databases from their inception to June 2014. We supplemented this work with manual searches and reference backtracking. The keywords that were used for searching were “sevoflurane”, “propofol”, “total intravenous anesthesia”, “cardiac surgery”, “cardioprotection”, and “randomized controlled clinical trials”.

Inclusion criteria

The following inclusion criteria were used for potentially relevant studies: (1) the participants in a study were adult patients undergoing cardiac surgery; (2) the study was a prospective, randomized, controlled clinical trial; (3) for anesthesia treatments in which the experimental group was anesthetized using sevoflurane, no propofol was used throughout the entire anesthesia process (including induction and maintenance phase), while the control group was anesthetized using propofol and no sevoflurane was used during the entire anesthesia process; (4) the study comprised detailed information, such as the number of cases, the number of controls, and the number of completed trials; and (5) the study involved measurement indices, including the postoperative cardiac index (CI), cardiac output (CO), postoperative cardiac troponin I (cTnI), postoperative mechanical ventilation time, intensive care unit (ICU) observation time, hospital stay, postoperative inotropic and vasoconstrictor drugs, postoperative atrial fibrillation, and myocardial infarction.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Based on the predefined standard form, we abstracted the following information: the number of cases, type of anesthetic, dose of anesthetic, anesthetic method, and measurement indices.

The Jadad scale [15] evaluation system was used to assess the quality of the identified literature, based on study design, interventions, and measurement indices. Two researchers performed the evaluation independently. Disagreement was resolved through discussion with a third investigator. Any study with a Jadad score ≥ 3 was regarded as high quality.

Statistical analysis

Review Manager (RevMan) Version 5.0 (Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014) software was used for meta-analysis and forest plots. The weighted mean difference (WMD) with the corresponding 95 % confidence interval (CI) was calculated as the effect size for estimating numerical variables, while odds ratios (ORs) with 95 % CIs were used for dichotomous variables. The chi-square test and I2 statistic were performed to determine heterogeneity among studies. If significant homogeneity existed (P > 0.1 and I2 < 50 %), a fixed effects model was used to calculate the pooled WMD or OR. A random effects model was used if P < 0.1 and I2 > 50 %. Subgroup analysis was performed, stratified either by the type of cardiac surgery (CABG or aortic valve replacement [AVR]) or use of cardiopulmonary blood bypass during CABG (on-pump or off-pump).

Publication bias

Publication bias detection was conducted through symmetry of funnel plots that were generated by RevMan 5.0.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis was performed by calculating the pooled effect size after removing studies one at a time to evaluate whether the result would be influenced by a single study.

Results

Selection of studies

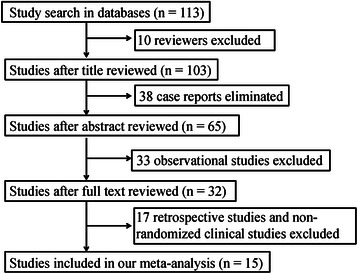

Duplicated publications were removed and studies that did not involve comparison of propofol and sevoflurane were excluded. If a cohort of studies was published based on one data set, the study that had the most comprehensive data was included for the meta-analysis. As a result, a total of 113 studies were obtained through preliminary screening. Ten reviews were then excluded by browsing the title and reading the abstract. Next, 38 case reports and 33 observational studies were eliminated through further selection. From the remaining 32 studies, 17 retrospective studies and non-randomized clinical studies were removed after full text reading. Finally, 15 eligible studies [16–30] were included for the meta-analysis. A flow chart of the literature selection is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of literature selection

Characteristics of the eligible studies and quality assessment

The characteristics of the included studies are shown in Table 1. A total of 1646 participants (1094 in the experimental group and 552 in the control group) were involved in the studies. All of the studies were published in English and they were carried out in 11 countries or regions. An assessment of quality is shown in Table 2. Because of the large proportion of high-quality research (3 studies with a score of 5, 1 study with score of 4, 3 studies with a score of 3, 5 studies with a score of 2, and 3 studies with a score of 1), the overall quality of the included studies was relatively high.

Table 1.

Basic Information of the 15 studies included in the meta-analysis

| Study | Country | Surgery | Number of cases (Sevoflurane/propofol, n) | Anesthesia | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sevoflurane group | Propofol group | ||||||

| Induction | Maintenance | Induction | Maintenance | ||||

| Gravel et al. [10] | Canada | CABG (on-pump and off-pump) | 15/15 | 4 % sevoflurane + 0.5 μg/kg sufentanil | 0.5-2MAC sevoflurane + 0.5 μg/kg/h sufentanil | 1 mg midazolam + 0.5 μg/kg sufentanil | 40-150 μg/kg/min propofol + 0.5 μg/kg/h sufentanil |

| De Hert et al. [11] | Belgium | CABG (on-pump) | 10/10 | 4 % sevoflurane + 0.4 μg/kg/min remifentanil | 0.5–2 % sevoflurane + 0.3–0.6 μg/kg/min remifentanil | 2 mg/ml propofol + 0.4 μg/kg/min remifentanil | 2-4 mg/ml propofol + 0.3-0.6 μg/kg/min remifentanil |

| Conzen et al. [12] | Germany | CABG (off-pump) | 10/10 | 0.3 mg/kg etomidate | 2 % sevoflurane | 2 μg/ml propofol | 2-3 μg/ml propofol |

| De Hert et al. [13] | Belgium | CABG (on-pump) | 15/15 | 2–8 % sevoflurane + 0.4 μg/kg/min remifentanil | 0.5–2%sevoflurane + 0.3–0.6 μg/kg/min remifentanil | 2 μg/ml propofol + 0.4 μg/kg/min remifentanil | 2-4 μg/ml propofol + 0.3-0.6 μg/kg/min remifentanil |

| De Hert et al. [14] | Belgium | CABG (on-pump) | 80/80 | 0.1 mg/kg midazolam + 0.4 μg/kg/min remifentanil | 0.5–2 % sevoflurane + 0.2–0.4 μg/kg/min remifentanil | 2 μg/mlpropofol + 0.4 μg/kg/min remifentanil | 2-4 μg/ml propofol + 0.2-0.4 μg/kg/min remifentanil |

| Parker et al. [15] | Australia | CABG (on-pump) | 118/118 | 10 μg/kg fentanyl + 0.1 mg/kg diazepam + 0.15 mg/kg pancuronium bromide | 1–4 % sevoflurane | 10 μg/kg fentanyl + 0.1 mg/kg diazepam + 0.15 mg/kg pancuronium bromide | 1-8 μg/ml propofol |

| Kawamura et al. [16] | Japan | CABG (on-pump) | 13/10 | 10 μg/kg fentanyl + 2–3 mg midazolam | 0.5 %-1 % sevoflurane + 30 μg/kg fentanyl | 10 μg/kg fentanyl + 2–3 mg midazolam | 2-8 mg/kg/h propofol + 30 μg/kg fentanyl |

| Cromheecke et al. [17] | Belgium | AVR | 15/15 | 0.5–1 % sevoflurane + 0.4 μg/kg/min remifentanil | 0.5–1 % sevoflurane + 0.2–0.4 μg/kg/min remifentanil | 2 μg/ml propofol + 0.4 μg/kg/min remifentanil | 2-4 μg/mlpropofol + 0.2-0.4 μg/kg/min remifentanil |

| Lorsomradee et al.[18] | Belgium | CABG (on-pump) | 160/160 | sevoflurane + 0.2–0.4 μg/kg/min remifentanil | 0.5–2 % sevoflurane + 0.2–0.4 μg/kg/min remifentanil | 2 μg/ml propofol + 0.2-0.4 μg/kg/min remifentanil | 2-4 μg/ml propofol + 0.2-0.4 μg/kg/min remifentanil |

| Law-Koune et al. [19] | France | CABG (off-pump) | 9/9 | 8 % sevoflurane + 2 ng/mL remifentanil | sevoflurane(BIS 40–60) + remifentanil | 2 μg/ml propofol + 2 ng/mL remifentanil | propofol(BIS 40–60) + remifentanil |

| Lucchinetti et al. [20] | Switzerland | CABG (off-pump) | 10/10 | fentanyl + midazolam | sevoflurane + fentanyl + midazolam | fentanyl + midazolam | propofol + fentanyl + midazolam |

| Yildirim et al. [21] | Turkey | CABG (on-pump) | 20/20 | 2–8 % sevoflurane + 0.4 μg/kg/min remifentanil | 0.5–2 % sevoflurane + 0.3–0.6 μg/kg/min remifentanil | 0.2 μg/ml propofol + 0.4 μg/kg/min remifentanil | 2-4 mg/mlpropofol + 0.3-0.6 μg/kg/min remifentanil |

| Ballester et al. [22] | Spain | CABG (off-pump) | 18/20 | 0.1 mg/kg midazolam + 2–4 μg/kg fentanyl + 0.3 mg/kg etomidate | 1.5–2.5 % sevoflurane | 0.1 mg/kg midazolam + 2–4 μg/kg fentanyl + 0.3 mg/kg etomidate | 6-8 mg/kg/h propofol |

| Jovic et al. [23] | Serbian | AVR | 11/11 | 0.3 mg/kg midazolam + 0.7–1 mcg/kg sufentanil | 0.1–0.2 mcg/kg/h sevoflurane | 1–1.5 mg/kg propofol + 0.7–1 mcg/kg sufentanil | 6-10 mg/kg/h propofol + 0.1-0.2 mcg/kg/h sufentanil |

| Suryaprakash et al. [24] | India | CABG (off-pump) | 48/39 | 5–10 μg/ kg fentanyl + 0.02 mg/kg midazolam | 1–2 % sevoflurane + 1 μg/kg/h fentanyl | 5–10 μg/ kg fentanyl + 0.02 mg/kg midazolam | 2-4 mg/kg/h propofol + 1 μg/kg/h fentanyl |

CABG coronary artery bypass graphing, AVR aortic valve replacement

Table 2.

Jadad score of the included studies

| Study | Random method | Blind | Exit in follow-up | Jadad score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gravel et al. [10] | Yes with description | Single | No | 3 |

| De Hert et al. [11] | Yes without description | Not described | No | 2 |

| Conzen et al. [12] | Yes without description | Not described | No | 2 |

| De Hert et al. [13] | Yes without description | Not described | Yes with description | 2 |

| De Hert et al. [14] | Yes with description | Double | No | 5 |

| Parker et al. [15] | Yes without description | Double | Yes with description | 4 |

| Kawamura et al. [16] | Yes without description | Single | Not described | 1 |

| Cromheecke et al. [17] | Yes with description | Not described | No | 3 |

| Lorsomradee et al. [18] | Yes with description | Double | No | 5 |

| Law-Koune et al. [19] | Yes without description | Single | Not described | 1 |

| Lucchinetti et al. [20] | Yes without description | Not described | Not described | 1 |

| Yildirim et al. [21] | Yes with description | Double | No exit | 5 |

| Ballester et al. [22] | Yes with description | Single | Yes with description | 3 |

| Jovic et al. [23] | Yes without description | Not described | No | 2 |

| Suryaprakash [24] | Yes with description | Not described | Not described | 2 |

Outcome of the effect of sevoflurane and propofol on cardioprotection

CI

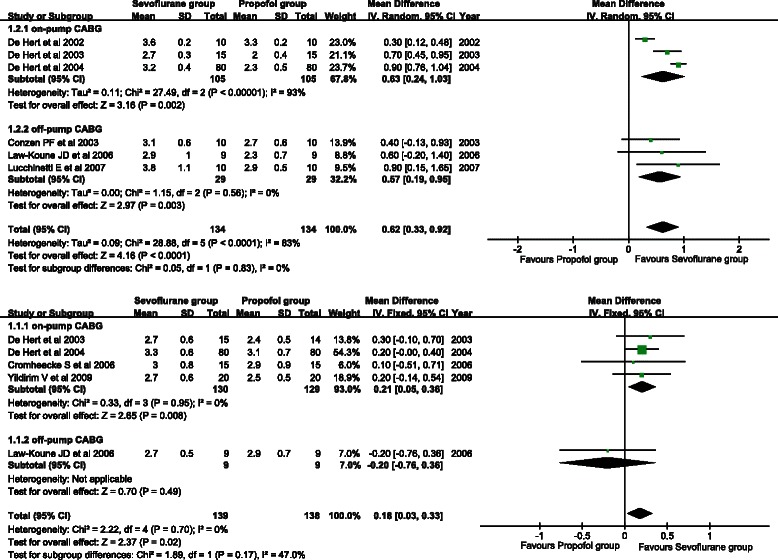

Six studies involved the postoperative CI. A random effects model was adopted because remarkable heterogeneity existed across studies (P < 0.001, I2 = 83 %). The sevoflurane group showed a significantly higher postoperative CI than the propofol group (WMD = 0.62, 95 % CI: 0.33 to 0.92; P < 0.001) (Fig. 2a). Subgroup analysis showed that a higher postoperative CI was observed in the on-pump CABG subgroup (WMD = 0.63, 95 % CI: 0.24 to 1.03; P < 0.001) and off-pump CABG subgroup (WMD = 0.57, 95 % CI: 0.19 to 0.95; P = 0.003).

Fig. 2.

Forest plots of the postoperative cardiac index (a) and postoperative 12-h cardiac index (b). Sevoflurane and propofol groups were compared

Five studies described the postoperative 12-h CI. A fixed effects model was used because there was no between-study heterogeneity (P = 0.70, I2 = 0 %). The postoperative 12-h CI of the sevoflurane group was significantly higher than that of the propofol group (WMD = 0.18, 95 % CI: 0.03 to 0.33; P = 0.02) (Fig. 2b). A similar conclusion was obtained in the on-pump CABG subgroup (WMD = 0.21, 95 % CI: 0.05 to 0.36; P = 0.008), but not in the off-pump CABG subgroup (WMD = −0.20, 95 % CI: −0.76 to 0.36; P = 0.49).

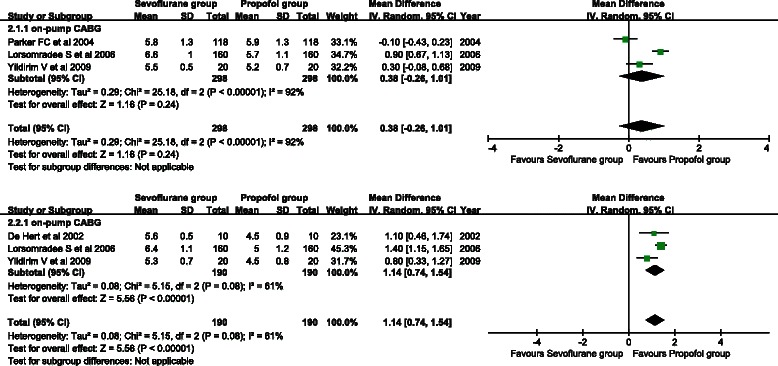

Cardiac output

Three studies provided CO. A random effects model was used for detection of substantial heterogeneity (P = 0.08, I2 = 61 %). As shown in Fig. 3a, CO of the sevoflurane group was significantly higher than that of the propofol group (WMD = 1.14, 95 % CI: 0.74 to 1.54; P < 0.001).

Fig. 3.

Forest plots of postoperative cardiac output (a) and postoperative 12-h cardiac output (b). Sevoflurane and propofol groups were compared

Three studies provided postoperative 12-h CO. A random effects model was used because there was between-study heterogeneity (P < 0.001, I2 = 92 %). No significant difference in postoperative 12-h CO was found between the sevoflurane group and the propofol group (WMD = 0.38, 95 % CI: −0.26 to 1.01; P = 0.24) (Fig. 3b).

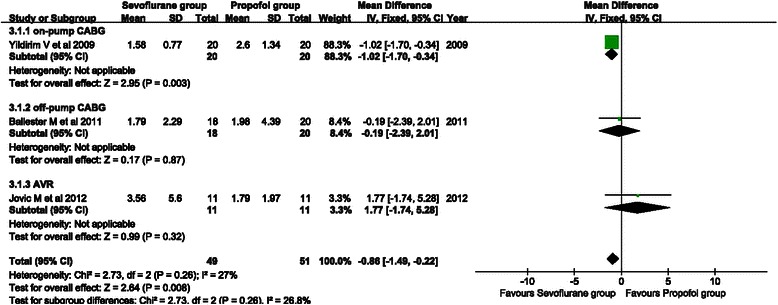

cTnI

cTnI is an indicator of postoperative myocardial injury. Three studies provided postoperative 24-h cTnI data. Three types of surgical procedures that were used were on-pump CABG, off-pump CABG, and AVR. A fixed effects model was applied for the absence of heterogeneity across studies (P = 0.26, I2 = 27 %). As a result, sevoflurane showed significantly lower postoperative 24-h cTnI levels compared with propofol treatment (WMD = −0.86, 95 % CI: −1.49 to −0.22; P = 0.008) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Forest plot showing comparison of postoperative 24-h cTnI between the sevoflurane and propofol groups

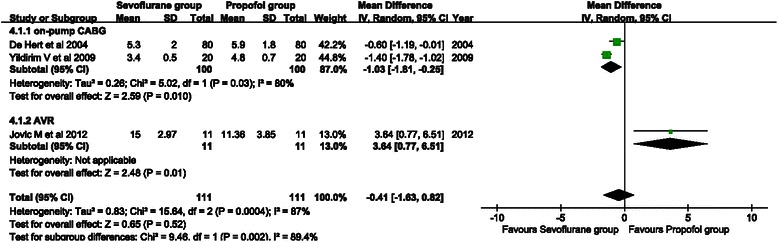

Mechanical ventilation time

Three studies reported postoperative mechanical ventilation time. A random effects model was used because of remarkable heterogeneity (P = 0.01, I2 = 77 %). There was no significant difference between the sevoflurane and propofol groups (WMD = −0.80, 95 % CI: −1.71 to 0.11; P = 0.08) (Fig. 5). Subgroup analysis showed that the mechanical ventilation time of the sevoflurane group was significantly shorter than that of the propofol group in the on-pump CABG subgroup (WMD = −1.03, 95 % CI: −1.81 to −0.25; P = 0.010). However, no significant difference was observed in the AVR subgroup (WMD = 1.64, 95 % CI: −1.23 to 4.51; P = 0.26).

Fig. 5.

Forest plot showing comparison of mechanical ventilation time between the sevoflurane and propofol groups

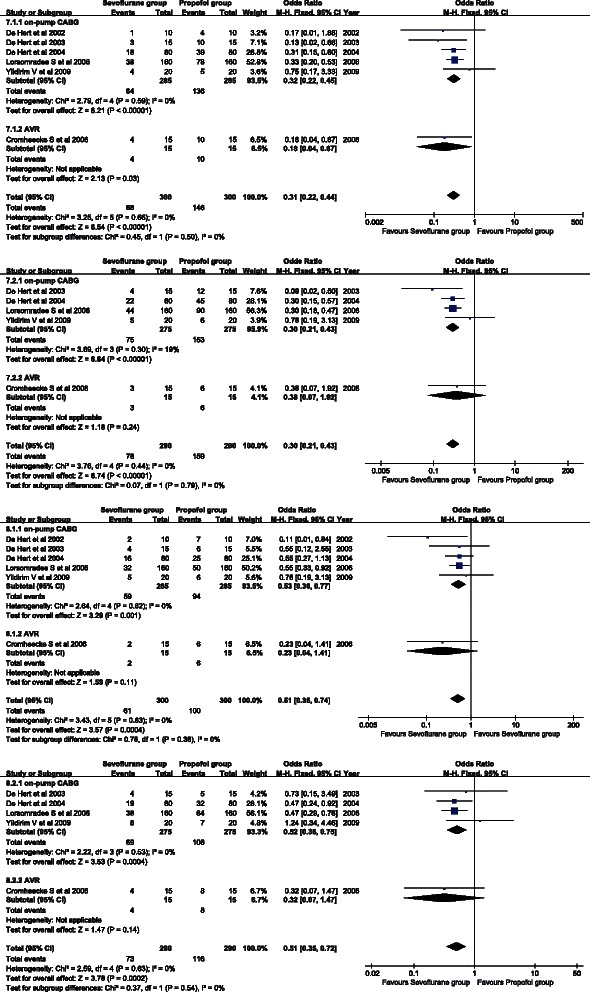

Drug use

Six studies reported postoperative inotropic drug use data. A fixed effects model was adopted there was no heterogeneity between studies (P = 0.66, I2 = 0 %). Inotropic drug use of the sevoflurane group was significantly less than that of the propofol group (OR = 0.31, 95 % CI: 0.22 to 0.44; P <0.001) (Fig. 6a). A similar conclusion was obtained in the on-pump CABG subgroup (OR = 0.32, 95 % CI: 0.22 to 0.45; P < 0.001) and the AVR subgroup (OR = 0.18, 95 % CI: 0.04 to 0.36; P = 0.03).

Fig. 6.

Forest plot of postoperative inotropic drug use (a). Forest plot of inotropic drug use during the ICU stay (b). Forest plot of postoperative vasoconstrictor drug use (c). Forest plot of vasoconstrictor drug use during ICU stay (d). Sevoflurane and propofol groups were compared

Five studies provided inotropic drug use data during the ICU stay. A fixed effects model was used for the homogeneity (P = 0.44, I2 = 0 %). Inotropic drug use during the ICU stay of the sevoflurane group was significantly less than that of the propofol group (OR = 0.30, 95 % CI: 0.21 to 0.43; P < 0.001) (Fig. 6b). A similar conclusion was obtained in the on-pump CABG subgroup (OR = 0.30, 95 % CI: 0.21 to 0.43; P < 0.001), but not in the AVR subgroup (OR = 0.38, 95 % CI: 0.07 to 1.92; P = 0.24).

Six studies contained information about postoperative vasoconstrictor drug use. A fixed effects model was applied for the absence of heterogeneity between studies (P = 0.63, I2 = 0 %). Postoperative vasoconstrictor drug use of the sevoflurane group was significantly lower than that of the propofol group (OR = 0.51, 95 % CI: 0.35 to 0.74; P = 0.0004) (Fig. 6c). A similar conclusion was obtained in the on-pump CABG subgroup (OR = 0.53, 95 % CI: 0.36 to 0.77; P = 0.001), but not in the AVR subgroup (OR = 0.23, 95 % CI: 0.04 to 1.41; P = 0.11).

Five studies reported information about vasoconstrictor drug use during the ICU stay. There was no heterogeneity between studies (P = 0.63, I2 = 0 %); therefore, a fixed effects model was applied. Vasoconstrictor drug use during the ICU stay of the sevoflurane group was significantly less than that of the propofol group (OR = 0.51, 95 % CI: 0.35 to 0.72; P = 0.0002) (Fig. 6d). A similar conclusion was obtained in the on-pump CABG subgroup (OR = 0.52, 95 % CI: 0.36 to 0.75; P = 0.0004), but not in the AVR subgroup (OR = 0.32, 95 % CI: 0.07 to 1.47; P = 0.14).

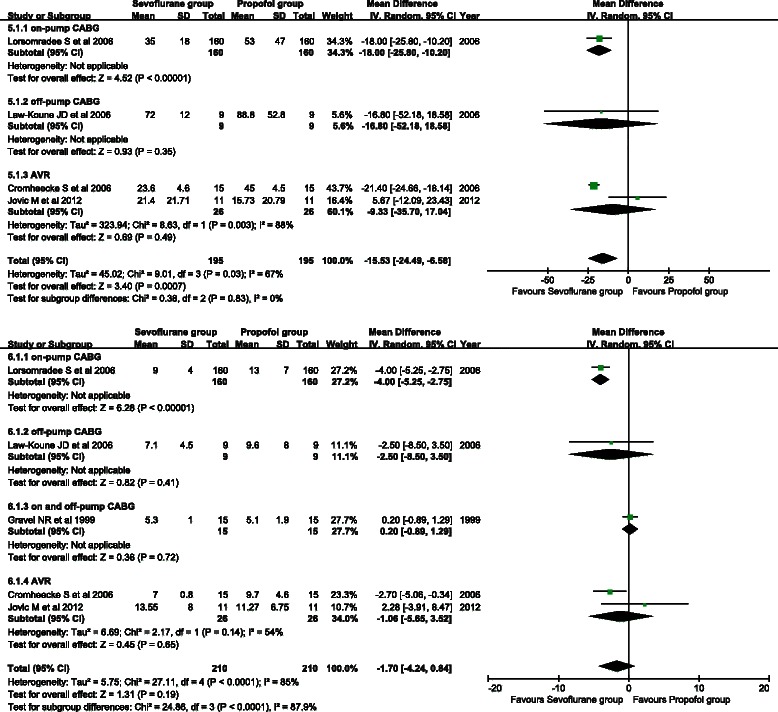

Postoperative ICU length of stay

Four studies involved postoperative length of stay in the ICU. A random effects model was applied because of between-study heterogeneity (P = 0.03, I2 = 67 %). The postoperative ICU length of stay was considerably lower in the sevoflurane group than in the propofol group (WMD = −15.53, 95 % CI: −24.29 to −6.58; P = 0.0007) (Fig. 7a). A similar conclusion was obtained in the on-pump CABG subgroup (WMD = −18.00, 95 % CI: −25.80 to −10.20; P < 0.001), but not in the other subgroups.

Fig. 7.

Forest plots of postoperative ICU length of stay (a) and hospital length of stay (b). Sevoflurane and propofol groups were compared

Five studies reported postoperative hospital stay data. A random effects model was adopted because of between-study heterogeneity (P < 0.001, I2 = 85 %). There was no significant difference in postoperative length of hospital stay between the two groups (WMD = −1.70, 95 % CI: −4.24 to 0.84; P = 0.19) (Fig. 7b). Subgroup analysis of the on-pump CABG subgroup showed that the length of hospital stay of the sevoflurane group was significantly shorter than that of the propofol group (WMD = −4.00, 95 % CI: −5.25 to −2.75; P < 0.001). No significant difference was found in hospital length of stay in the other subgroups.

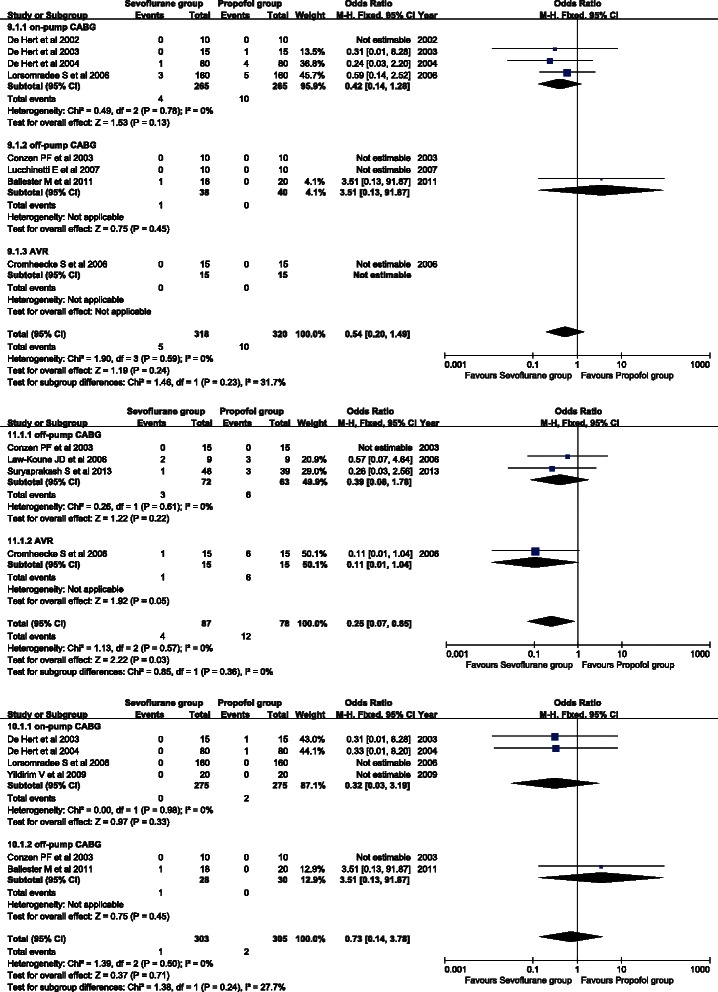

Incidence of postoperative complications and mortality

Eight studies provided information on the incidence of postoperative myocardial infarction. A fixed effects model was used for observation of homogeneity (P = 0.59, I2 = 0 %). There was no significant difference in the incidence of postoperative myocardial infarction between the sevoflurane and propofol groups (OR = 0.54, 95 % CI: 0.20 to 1.49; P = 0.24) (Fig. 8a). There was also no significant difference in any of the subgroups.

Fig. 8.

Forest plots of the incidence of postoperative myocardial infarction (a). Forest plot of atrial fibrillation (b). Forest plot of mortality (c). Sevoflurane and propofol groups were compared

Five studies provided the incidence of postoperative atrial fibrillation. No between-study heterogeneity was detected (P = 0.57, I2 = 0 %) and a fixed effects model was used. The incidence of postoperative atrial fibrillation of the sevoflurane group was significantly lower than that of the propofol group (OR = 0.25, 95 % CI: 0.07 to 0.85; P = 0.03) (Fig. 8b). No significant difference was found in any of the subgroups.

Six studies provided postoperative mortality data. A fixed effects model was used in analysis because there was no heterogeneity between studies (P = 0.50, I2 = 0 %). There was no significant difference in mortality between the sevoflurane and propofol groups (OR = 0.73, 95 % CI: 0.14 to 3.78; P = 0.71) (Fig. 8c). Subgroup analysis showed no significant difference in mortality in any of the subgroups.

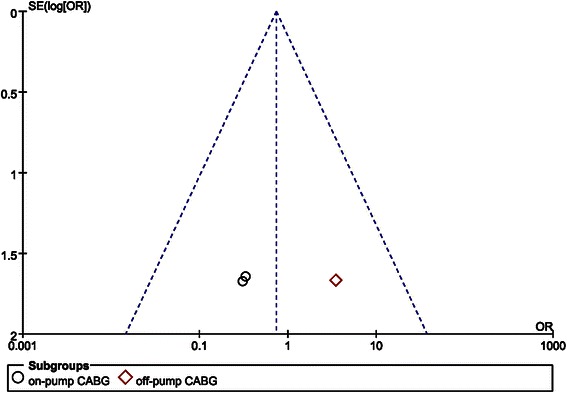

Publication bias and sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis showed that the conclusion was not affected by exclusion of any single included study. No obvious publication bias was found according to the funnel plots (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

Publication bias analysis according to a funnel plot for postoperative mortality

Discussion

In this study, we retrieved 15 randomized, controlled trials to compare the cardioprotective effect of sevoflurane with propofol anesthesia in cardiac surgery. We found that sevoflurane was superior to propofol in the postoperative CI, postoperative 24-h CI, postoperative CO, postoperative 24-h cTnI concentrations, inotropic drug use, vasoconstrictor drug use, ICU length of stay, and incidence of atrial fibrillation. However, no significant difference was found in postoperative 12-h CO, mechanical ventilation time, hospital length of stay, incidence of myocardial infarction, and mortality between sevoflurane and propofol. All of these findings were consistent with a previous meta-analysis, except for inotropic drug use and the incidence of atrial fibrillation, which showed a comparable effect [13]. However, subgroup analysis was not involved in this previous study and the samples were relatively small. By contrast, our study applied a more strict inclusion criterion in case and control experimental design. We focused only on studies in which the experimental group was anesthetized using sevoflurane but not propofol throughout the entire anesthesia process, while the control group was anesthetized by propofol but not sevoflurane. In Yao and Li’s meta-analysis [13], the experimental or control group was anesthetized using both sevoflurane and propofol in some of the included studies. Additionally, we carried out subgroup analysis in our study, which made the results more precise than previous analyses.

The level of cTnI is a sensitive and specific marker of myocardial injury. A sevoflurane-induced reduction in cTnI levels is associated with a lower incidence of late adverse cardiac events [31]. Accordingly, we observed a lower incidence of atrial fibrillation in the sevoflurane group than in the propofol group. ICU and the hospital stay length are two comprehensive indicators that are associated with postoperative complications and medical fees. The current study showed that use of sevoflurane led to a shorter ICU stay length, but not hospital stay length compared with the propofol group. This finding might be explained by different study populations and varying hospital operating standards. Moreover, reduced inotropic drug use in the sevoflurane group is consistent with the study by Yu et al. [8], which showed that volatile anesthetics benefit myocardial energy stores during ischemia and subsequent recovery after reperfusion [8].

Volatile anesthetics have a long-lasting cardioprotective effect that enhances their administration during cardiac surgery [32]. Extensive studies have confirmed that sevoflurane protests against ischemic myocardial damage [32, 33]. However, in our study, no significant difference was detected in the incidence of postoperative myocardial infarction between sevoflurane and propofol, suggesting that propofol might have comparable myocardial protection with sevoflurane.

In our meta-analysis, all of the included 15 studies were prospective, randomized, clinical trials, and their quality was high. Additionally, we conducted subgroup analysis to obtain accurate results. However, several limitations should be mentioned. First, because of language restrictions and database updates, we could not include literature in other languages nor those yet to be published. Including those studies would have affected our results. Second, the sample size was small and no blinding was mentioned in some studies. Third, differences in surgical and medical technology among the studies included also affected the results. Finally, significant heterogeneity was observed in some assessment indices, which might have caused bias in our results. We assert that more high-quality, randomized, controlled trials are warranted.

Conclusions

In conclusion, sevoflurane anesthesia has a better cardioprotective effect on patients undergoing cardiac surgery according to several indicators than propofol anesthesia. However, multicenter, prospective, randomized, controlled trails with large samples, uniform criteria, and surgical procedures are necessary to further confirm the advantage of sevoflurane over propofol.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

This work was not supported by any funding project.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

LF participated in the design of the study and performed the statistical analysis. YY conceived the study, participated in its design and coordination, and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Contributor Information

Feng Li, Email: lifenglifengllff@163.com.

Yuan Yuan, Email: yuanyuanyydd@126.com.

References

- 1.Anselmi A, Abbate A, Girola F, Nasso G, Biondi-Zoccai GG, Possati G, Gaudino M. Myocardial ischemia, stunning, inflammation, and apoptosis during cardiac surgery: a review of evidence. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2004;25(3):304–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weiner M, Reich D, Lin H, Krol M, Fischer G. Influence of increased left ventricular myocardial mass on early and late mortality after cardiac surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2013;110(1):41–6. doi: 10.1093/bja/aes299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stadnicka A, Marinovic J, Ljubkovic M, Bienengraeber MW, Bosnjak ZJ. Volatile anesthetic-induced cardiac preconditioning. J Anesth. 2007;21(2):212–9. doi: 10.1007/s00540-006-0486-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zaugg M, Lucchinetti E, Spahn DR, Pasch T, Schaub MC. Volatile anesthetics mimic cardiac preconditioning by priming the activation of mitochondrial K (ATP) channels via multiple signaling pathways. Anesthesiology. 2002;97(1):4–14. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200207000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Novalija E, Kevin LG, Camara A, Bosnjak ZJ, Kampine JP, Stowe DF. Reactive oxygen species precede the epsilon isoform of protein kinase C in the anesthetic preconditioning signaling cascade. Anesthesiology. 2003;99(2):421–8. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200308000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Symons J, Myles P. Myocardial protection with volatile anaesthetic agents during coronary artery bypass surgery: a meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth. 2006;97(2):127–36. doi: 10.1093/bja/ael149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Landoni G, Biondi-Zoccai GG, Zangrillo A, Bignami E, D’Avolio S, Marchetti C, Calabrò MG, Fochi O, Guarracino F, Tritapepe L. Desflurane and sevoflurane in cardiac surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2007;21(4):502–11. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2007.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu CH, Beattie WS. The effects of volatile anesthetics on cardiac ischemic complications and mortality in CABG: a meta-analysis. Can J Anaesth. 2006;53(9):906–18. doi: 10.1007/BF03022834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Landoni G, Greco T, Biondi-Zoccai G, Neto CN, Febres D, Pintaudi M, Pasin L, Cabrini L, Finco G, Zangrillo A. Anaesthetic drugs and survival: a Bayesian network meta-analysis of randomized trials in cardiac surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2013;111(6):886–96. doi: 10.1093/bja/aet231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sirvinskas E, Kinderyte A, Trumbeckaite S, Lenkutis T, Raliene L, Giedraitis S, et al. Effects of sevoflurane vs. propofol on mitochondrial functional activity after ischemia-reperfusion injury and the influence on clinical parameters in patients undergoing CABG surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass. Perfusion. 2015; 0267659115571174. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Joo HS, Perks WJ. Sevoflurane versus propofol for anesthetic induction: a meta-analysis. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2000;91(1):213–9. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200007000-00040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jakobsen C-J, Berg H, Hindsholm KB, Faddy N, Sloth E. The influence of propofol versus sevoflurane anesthesia on outcome in 10,535 cardiac surgical procedures. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2007;21(5):664–71. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yao Y-T, Li L-H. Sevoflurane Versus Propofol for Myocardial Protection in Patients Undergoing Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting Surgery: a Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Chin Med Sci J. 2009;24(3):133–41. doi: 10.1016/S1001-9294(09)60077-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gravel NR, Searle NR, Taillefer J, Carrier M, Roy M, Gagnon L. Comparison of the hemodynamic effects of sevoflurane anesthesia induction and maintenance vs TIVA in CABG surgery. Can J Anaesth. 1999;46(3):240–6. doi: 10.1007/BF03012603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Hert SG, ten Broecke PW, Mertens E, Van Sommeren EW, De Blier IG, Stockman BA, Rodrigus IE. Sevoflurane but not propofol preserves myocardial function in coronary surgery patients. Anesthesiology. 2002;97(1):42–9. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200207000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Conzen PF, Fischer S, Detter C, Peter K. Sevoflurane provides greater protection of the myocardium than propofol in patients undergoing off-pump coronary artery bypass surgery. Anesthesiology. 2003;99(4):826–33. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200310000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Hert SG, Cromheecke S, ten Broecke PW, Mertens E, De Blier IG, Stockman BA, Rodrigus IE, Van der Linden PJ. Effects of propofol, desflurane, and sevoflurane on recovery of myocardial function after coronary surgery in elderly high-risk patients. Anesthesiology. 2003;99(2):314–23. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200308000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Hert SG, Van der Linden PJ, Cromheecke S, Meeus R, ten Broecke PW, De Blier IG, Stockman BA, Rodrigus IE. Choice of primary anesthetic regimen can influence intensive care unit length of stay after coronary surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass. Anesthesiology. 2004;101(1):9–20. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200407000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parker FC, Story DA, Poustie S, Liu G, McNicol L. Time to tracheal extubation after coronary artery surgery with isoflurane, sevoflurane, or target-controlled propofol anesthesia: a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2004;18(5):613–9. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kawamura T, Kadosaki M, Nara N, Kaise A, Suzuki H, Endo S, Wei J, Inada K. Effects of sevoflurane on cytokine balance in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2006;20(4):503–8. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2006.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cromheecke S, Pepermans V, Hendrickx E, Lorsomradee S, Ten Broecke PW, Stockman BA, Rodrigus IE, De Hert SG. Cardioprotective properties of sevoflurane in patients undergoing aortic valve replacement with cardiopulmonary bypass. Anesth Analg. 2006;103(2):289–96. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000226097.22384.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lorsomradee S, Cromheecke S, De Hert SG. Effects of sevoflurane on biomechanical markers of hepatic and renal dysfunction after coronary artery surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2006;20(5):684–90. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2006.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Law-Koune JD, Raynaud C, Liu N, Dubois C, Romano M, Fischler M. Sevoflurane-remifentanil versus propofol-remifentanil anesthesia at a similar bispectral level for off-pump coronary artery surgery: no evidence of reduced myocardial ischemia. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2006;20(4):484–92. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lucchinetti E, Hofer C, Bestmann L, Hersberger M, Feng J, Zhu M, Furrer L, Schaub MC, Tavakoli R, Genoni M, et al. Gene regulatory control of myocardial energy metabolism predicts postoperative cardiac function in patients undergoing off-pump coronary artery bypass graft surgery: inhalational versus intravenous anesthetics. Anesthesiology. 2007;106(3):444–57. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200703000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yildirim V, Doganci S, Aydin A, Bolcal C, Demirkilic U, Cosar A. Cardioprotective effects of sevoflurane, isoflurane, and propofol in coronary surgery patients: a randomized controlled study. Heart Surg Forum. 2009;12(1):E1–9. doi: 10.1532/HSF98.20081137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ballester M, Llorens J, Garcia-de-la-Asuncion J, Perez-Griera J, Tebar E, Martinez-Leon J, Belda J, Juez M. Myocardial oxidative stress protection by sevoflurane vs. propofol: a randomised controlled study in patients undergoing off-pump coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2011;28(12):874–81. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0b013e32834bea2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jovic M, Stancic A, Nenadic D, Cekic O, Nezic D, Milojevic P, Micovic S, Buzadzic B, Korac A, Otasevic V, et al. Mitochondrial molecular basis of sevoflurane and propofol cardioprotection in patients undergoing aortic valve replacement with cardiopulmonary bypass. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2012;29(1–2):131–42. doi: 10.1159/000337594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suryaprakash S, Chakravarthy M, Muniraju G, Pandey S, Mitra S, Shivalingappa B, Chittiappa S, Krishnamoorthy J. Myocardial protection during off pump coronary artery bypass surgery: a comparison of inhalational anesthesia with sevoflurane or desflurane and total intravenous anesthesia. Ann Card Anaesth. 2013;16(1):4–8. doi: 10.4103/0971-9784.105361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garcia C, Julier K, Bestmann L, Zollinger A, von Segesser LK, Pasch T, Spahn DR, Zaugg M. Preconditioning with sevoflurane decreases PECAM-1 expression and improves one-year cardiovascular outcome in coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2005;94(2):159–65. doi: 10.1093/bja/aei026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Hert SG, Van der Linden PJ, Cromheecke S, Meeus R, Nelis A, Van Reeth V, ten Broecke PW, De Blier IG, Stockman BA, Rodrigus IE. Cardioprotective properties of sevoflurane in patients undergoing coronary surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass are related to the modalities of its administration. Anesthesiology-Philadelphia Then Hagerstown. 2004;101:299–310. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200408000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dai A-l, Fan L-h, Zhang F-j, Yang M-j, Yu J, Wang J-k, Fang T, Chen G, Yu L-n, Yan M. Effects of sevoflurane preconditioning and postconditioning on rat myocardial stunning in ischemic reperfusion injury. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2010;11(4):267–74. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B0900390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]