Abstract

Background

Neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS), such as apathy and depression, commonly accompany cognitive and functional decline in early Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Prior studies have shown associations between affective NPS symptoms and neurodegeneration of medial frontal and inferior temporal regions in mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and AD dementia.

Objective

To investigate the association between functional connectivity in four brain networks and NPS in elderly with MCI.

Methods

NPS were assessed using the Neuropsychiatric Inventory in 42 subjects with MCI. Resting-state functional connectivity in four networks (default mode network, fronto-parietal control network (FPCN), dorsal attention network, and ventral attention network) was assessed using seed-based magnetic resonance imaging. Factor analysis was used to identify two factors of NPS: Affective and Hyperactivity. Linear regression models were utilized with the neuropsychiatric factors as the dependent variable and the four networks as the predictors of interest. Covariates included age, sex, premorbid intelligence, processing speed, memory, head movement, and signal-to-noise ratio. These analyses were repeated with the individual items of the Affective factor, using the same predictors.

Results

There was a significant association between greater Affective factor symptoms and reduced FPCN connectivity (p=0.03). There was no association between the Hyperactivity factor and any of the networks. Secondary analyses revealed an association between greater apathy and reduced FPCN connectivity (p=0.005), but none in other networks.

Conclusions

Decreased connectivity in the FPCN may be associated with greater affective symptoms, particularly apathy, early in AD. These findings extend prior studies, using different functional imaging modalities in individuals with greater disease severity.

Keywords: mild cognitive impairment, neuropsychiatric symptoms, apathy, Alzheimer’s disease, functional magnetic resonance imaging

Introduction

Neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS), such as apathy and depression, commonly accompany cognitive and functional decline in early Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [1–5]. Prior studies have shown associations between these affective symptoms and frontal and temporal atrophy, hypometabolism, and hypoperfusion in mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and AD dementia [6–11]. Therefore, affective symptoms have been shown to be related to specific brain regions and to be intrinsic symptoms of early AD, as are cognitive and functional deficits.

One such affective symptom, apathy, is characterized by a lack of motivation and interest, a loss of goal-oriented behavior and social withdrawal. It is highly prevalent in patients with MCI and across the AD dementia spectrum [12–15], but is also seen in other disorders that may cause cognitive impairment (e.g., Frontotemporal dementia and Parkinson’s disease)[16]. The presence of apathy and other affective NPS, such as anxiety or depression, has been shown to increase the risk of developing MCI [2, 17], while apathy specifically has been associated with executive dysfunction and impairment of activities of daily living [18–20]. Previous imaging studies of different modalities, including structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), positron emission tomography, and single photon emission computed tomography, have shown apathy in AD to be associated primarily with orbitofrontal, anterior cingulate, and inferior temporal areas in the brain [6–9, 21–23]. There has also been evidence of widespread microstructural white matter abnormalities (in the form of increased mean diffusivity with diffusion weighted imaging and white matter changes indicative of demyelination, axonal loss and lacunar infarcts found on computed tomography and MRI scans) in MCI subjects with increased apathy, suggesting an apathy-related disconnection between regions early on in cognitive disorders[24, 25]. Although there is strong evidence that NPS are correlated with these specific brain regions and white matter changes, there is little indication of how these symptoms are associated with functional brain networks.

There are multiple studies which suggest disruption of connectivity in MCI, especially during cognitive tasks [26–28]; however, there are no studies to our knowledge which have studied the relationship between NPS and functional connectivity in MCI. Few studies have assessed the relationship between NPS and functional connectivity in individuals with AD dementia. In one study comparing individuals with mild-moderate AD dementia to those with normal cognition, greater symptoms comprising the hyperactivity NPS subsyndrome, but not the apathy, affective or psychosis subsyndromes, were associated with increased connectivity in the anterior cingulate and insula regions of the ventral attention network (VAN, a.k.a. the salience network)[29]. Analyses of functional connectivity in other studies showed that cognitively intact depressed older individuals were found to have reduced connectivity in the cognitive control network (a.k.a. cingulo-opercular network), as well as apathy-related alterations in salience network connectivity [30, 31].

In the current study, we wished to investigate, in subjects with MCI, the relationship of NPS with resting-state connectivity in four different brain networks (the fronto-parietal control network (FPCN), the default mode network (DMN), the VAN, and the dorsal attention network (DAN)) that have been shown to be affected in AD and other neurodegenerative diseases [32–35].

To evaluate NPS, we utilized the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI)[36], an informant-based questionnaire that quantifies the frequency and severity of 12 distinct NPS. Resting-state functional MRI (fMRI) was used to measure functional connectivity of the four networks. Further knowledge of the relationship between NPS and functional connectivity could help to elucidate the links between behavioral symptoms and AD pathophysiology, providing more diagnostic and treatment opportunities.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Forty-two subjects with MCI recruited consecutively between January, 2010 and September, 2011 to participate in an investigator-initiated imaging study underwent clinical assessment and resting state fMRI at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Alzheimer Research and Treatment. Subjects were ages 53–85 (inclusive), were medically stable, and did not have significant confounding neurological conditions, recent substance or alcohol abuse, or current primary psychiatric diagnoses. Subjects had a Modified Hachinski Ischemic Score [37]≤ 4 and a Geriatric Depression Scale (long form) [38]≤ 10. Subjects had a study partner who provided collateral information about their mood, behavior, and daily functioning.

Subjects met criteria for amnestic MCI, single or multiple domain [39]. These criteria included a memory complaint (reported by the subject or study partner); objective memory impairment assessed with the Logical Memory IIa (delayed story recall) of the Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised [40]; essentially intact activities of daily living; and no evidence of dementia. They also had a Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) [41] score of 23–30 (inclusive) and a Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) [42] global score of 0.5, and a Memory Box score ≥ 0.5. Of note, subjects with non-amnestic MCI were not eligible to participate in this study.

The study was approved by the Partners (local) Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and their study partners before any of the study procedures were carried out.

Clinical Assessments

The Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) [36, 43] was used to assess NPS frequency and severity based on an informant interview. The NPI consists of 12 behavioral items, each rated as 0–3 for severity and 1–4 for frequency. The total score for each item is the product of its frequency and severity scores (range 0–12). Higher scores indicate worse neuropsychiatric symptoms.

The American National Adult Reading Test (AMNART) intelligence quotient (IQ) [44] was used as an estimate of premorbid verbal IQ; The Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised Digit Symbol test [45] was used to assess components of executive function, encompassing processing speed, visual scanning, and working memory; and the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT) total learning score [46] was used to assess memory.

MRI Data

Resting-state fMRI data were acquired using a Siemens Trio 3 Tesla scanner (Siemens Medical Systems, Erlangen Germany). The data were processed using SPM8 (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/; version r4290). Each run was slice-time corrected, realigned to the first volume of each run with INRIAlign (http://www-sop.inria.fr/epidaure/software/INRIAlign/;[47]; [48]), normalized to the MNI 152 EPI template (Montreal Neurological Institute, Montreal, Canada), and smoothed with a 6 mm FWHM Gaussian kernel. Finally, the data for each subject were manually checked to identify registration errors and signal dropout. No subjects included in this investigation had these errors. Following this, the 6 motion parameters were regressed out, as well as first derivatives of motion. Data were then band pass filtered in the 0.01–0.08 Hz range using a second order butter worth filter. Finally, time-courses for ventricle signal, white matter signal, and global signal (plus first derivatives) were regressed out of the data. Subjects were excluded from analysis if any one of the following quality assessment conditions were met: lower than a threshold of 115 for slice-based signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), higher than a threshold of 0.2mm for mean movement, or more than 20 outlier volumes (defined as a change in the global signal >2.5 SD attributable to the volume, a change in position >0.75mm or a change in rotation >1.5° from the previous volume).

Functional connectivity was assessed using seed-based MRI [49] (See Table 1 for seed coordinates). Seed time courses for the 24 left hemisphere seeds (6 per network), were extracted using 10mm spheres around each coordinate, and the network measures were computed by averaging the fisher-Z transformed corrections between all pairs of seeds within a network. The seeds were then reflected into the right hemisphere and the process was repeated. Bilateral connectivity was assessed by averaging the left and right hemisphere values, with higher values indicating increased network connectivity. Four networks of potential relevance to NPS in MCI were examined: the DMN, FPCN, DAN, and VAN.

Table 1.

Locations of seed regions used for analysis, adapted from Yeo, et al. [49]

| Seed Region | Coordinates | Seed Region | Coordinates |

|---|---|---|---|

| DAN A | −22, −8, 54 | FPCN A | −40, 50, 7 |

| DAN B | −34, −38, 44 | FPCN B | −43, −50, 46 |

| DAN C | −18, −69, 51 | FPCN C | −57, −54, −9 |

| DAN D | −51,−64, −2 | FPCN D | −5, 22, 47 |

| DAN E | −8, −63, 57 | FPCN E | −6, 4, 29 |

| DAN F | −49, 3, 34 | FPCN F | −4, −76, 45 |

| VAN A | −31, 39, 30 | DMN A | −27, 23, 48 |

| VAN B | −54, −36, 27 | DMN B | −41, −60, 29 |

| VAN C | −60, −59, 11 | DMN C | −64, −20, −9 |

| VAN D | −5, 15, 32 | DMN D | −7, 49, 18 |

| VAN E | −8, −24, 39 | DMN E | −25, −32, −18 |

| VAN F | −31, 11, 8 | DMN F | −7, −52, 26 |

Coordinates reflect the approximate center location based on the MNI atlas. DAN (Dorsal Attention Network), VAN (Ventral Attention Network), FPCN (Fronto-Parietal Control Network), DMN (Default Mode Network).

The FPCN comprises multiple regions spanning the frontal and parietal cortices, including the precuneus, mid-cingulate, inferior parietal sulcus, inferior parietal lobule, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, and lateral frontal cortex [50]. The FPCN is critical for goal-related behavior and flexible information processing [50]. The DMN also includes the precuneus, but extends to the posterior cingulate, ventromedial prefrontal cortex, ventral anterior cingulate cortex, inferior lateral parietal lobe, and the temporal lobe. This network is noted for showing decreased activity during task performance [30]. The VAN, or salience network, consists of the anterior cingulate, insula, striatum and amygdala, and is implicated in attention, switching, and self-regulation of behavior. Salience network dysfunction is particularly notable in patients with frontotemporal dementia [31, 51]. The DAN is centered on the intraparietal sulcus and encompasses the frontal eye fields. This top-down network is thought to be involved in goal-driven attention orientation[34].

The mean interval between MRI acquisition and clinical assessment was 22 ± 22 days.

Statistical Analyses

All analyses in this study were carried out using SPSS version 22.0 (IBM). Exploratory factor analysis was used to identify two factors of neuropsychiatric symptoms: an Affective factor (comprised of anxiety, apathy, depression, appetite, and sleep) and a Hyperactivity factor (comprised of agitation, irritability, aberrant motor behavior, and disinihibition). Of note, the labels Affective and Hyperactivity were an attempt to use a single word to capture as much of the different symptoms compromising each factor. However, these are data driven results and do not necessarily represent a clinical construct. The Kaiser-Meyer-Okin value of 0.44 and Barlett’s Test of Sphericity (p < 0.001) supported the factorability of the correlation matrix. There was a moderately strong correlation between the two factors (r=0.45, p=0.003). Three of the NPI items (delusions, hallucinations, and euphoria) were not included in the factor analysis because all subjects had scores of 0 for these items.

For our primary analyses, separate linear regression models with backward elimination (p<0.1 retention requirement; p<0.05 considered significant) were utilized with the neuropsychiatric factors as the dependent variable and the 4 networks as the predictors of interest. Covariates included demographic variables (age, sex, and AMNART IQ), processing speed and encoding memory (which have been shown to be associated with NPS[6]). Head movement during the MRI scan and SNR were also included as covariates. Partial regression coefficient estimates (β) and confidence intervals (CI) and significance test results (p values) were reported for each predictor retained after backward elimination. Percent variance accounted for in the dependent variable by the model as a whole (R2) was also reported. The distributions of data points from residuals of the final model were assessed graphically for normality and homoscedasticity to ensure consistency with the model’s assumptions. An additional model was run where all predictors were retained in order to explore for potential collinearity among the predictors, especially the 4 networks.

For our Secondary analyses, we repeated the model employed in the primary analyses with the 5 individual NPI items of the Affective factor using the same predictors. Due to multiple comparisons, p values <0.01 were considered significant in these secondary analyses (employing a Bonferroni correction in which a p-value of 0.05 is divided by 5 due to having comparisons of separate models for each of the 5 individual NPI items, yielding a p-value of 0.01).

Results

Demographics for subjects are found in Table 2. Individual NPI item scores and total NPI score for subjects are found in Table 3.

Table 2.

Baseline demographic and neuropsychological characteristics.

| N | 42 |

| Age (years) | 74.0±8.4 (53–85) |

| Sex (% female)* | 28.6 |

| Education (years) | 17.1±2.4 (12–20) |

| AMNART IQ | 122.3±7.4 (100–131) |

| MMSE | 27.4±2.1 (23–30) |

| CDR-Sum of Boxes | 1.6±0.9 (1.0–4.0) |

| Digit Symbol | 43.8±12.0 (22–69) |

| RAVLT Total Learning | 33.5±9.2 (18–55) |

AMNART IQ (American National Adult Reading Test intelligence quotient), CDR (Clinical Dementia Rating), MMSE (Mini-Mental State Examination), RAVLT (Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test). All values (except n and sex) represent mean ± standard deviation (range).

Table 3.

Individual NPI item scores and total NPI score.

|

Affective Factor |

Depression/Dysphoria | 0.8±1.2 (0–4) 40.5% |

| Anxiety | 1.0±1.6 (0–8) 47.6% |

|

| Apathy | 0.3±1.0 (0–4) 11.9% |

|

| Sleep | 0.9±2.3 (0–12) 21.4% |

|

| Appetite and Eating Disorder | 0.1±0.7 (0–4) 4.8% |

|

|

Hyperactivity Factor |

Agitation/Aggression | 0.2±0.5 (0–2) 14.3% |

| Irritability/Lability | 1.1±1.2 (0–4) 52.4% |

|

| Disinhibition | 0.1±0.3 (0–2) 4.8% |

|

| Aberrant Motor Behavior | 0.1±0.6 (0–4) 2.4% |

|

| Total NPI Score | 4.5±4.6 (0–20) 88.1% |

NPI (Neuropsychiatric Inventory). All subjects had scores of 0 for delusions, hallucinations, and euphoria, which are not shown in the table. All values (except n) represent mean item or total NPI score (product of frequency and severity) ± standard deviation (range) and percent present (scores > 0).

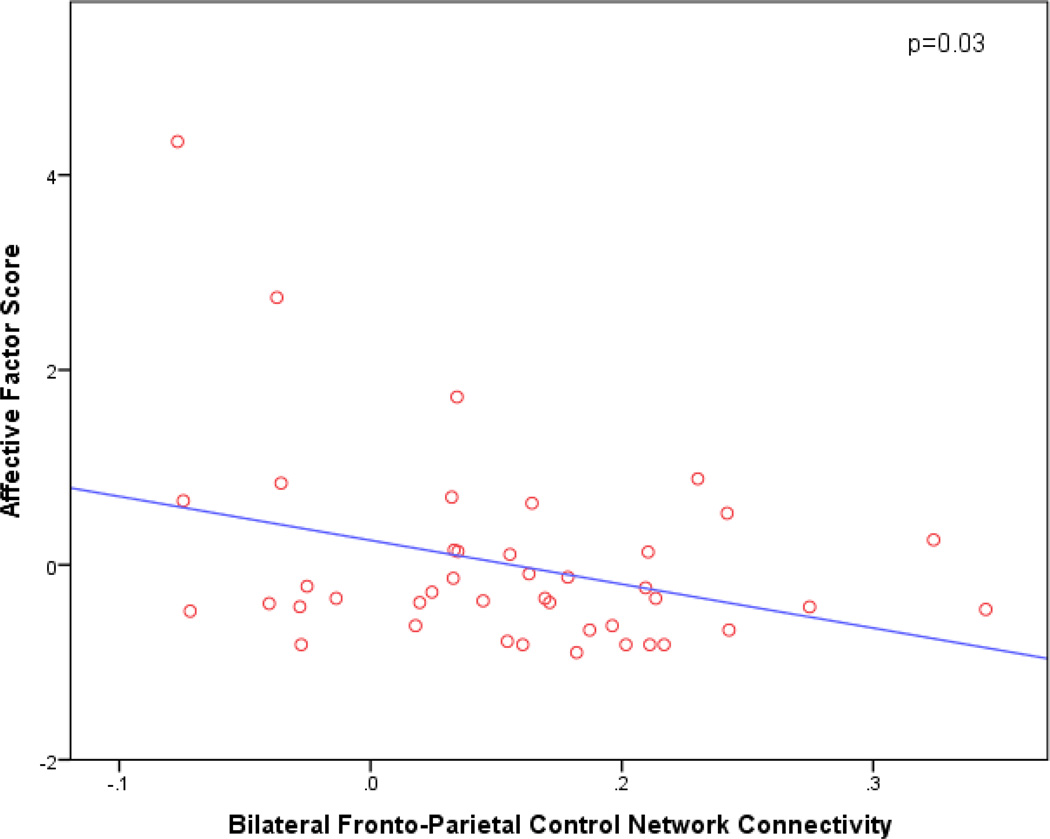

In our primary analyses, greater Affective factor symptoms were significantly associated with reduced FPCN connectivity (p=0.03; β=−4.50; 95% CI [−8.52, −0.49]) (see Figure 1). There was no significant association with any of the other networks or covariates. The overall model was significant (p=0.03), accounting for 11.4% of the variance. Results were similar in the confirmatory model in which all predictors were retained without backward elimination. There was no significant association between the Hyperactivity factor and any of the networks or covariates.

Figure 1.

Scatter plot of bilateral fronto-parietal control network connectivity vs. Affective factor score. Since only fronto-pareital control network was retained in the regression model, the plot presented here is not adjusted for any other predictors. Reduced bilateral fronto-parietal control network connectivity is associated with greater affective symptoms.

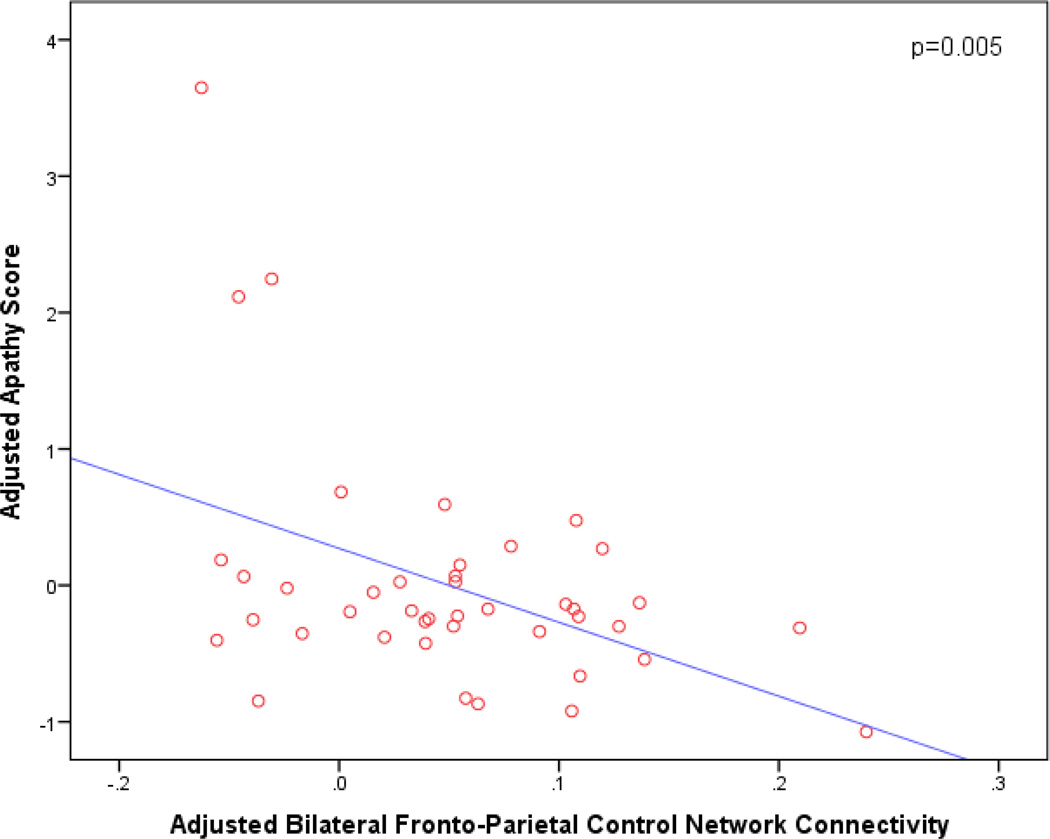

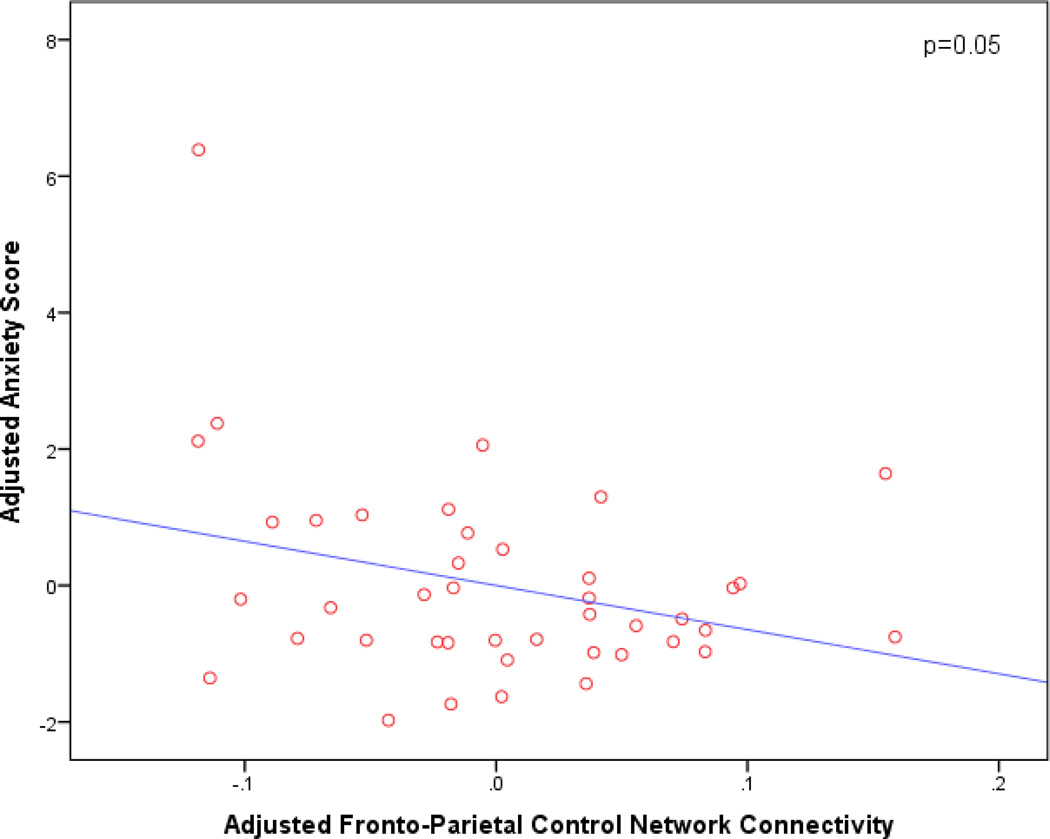

Secondary analyses of each individual Affective symptom revealed associations between greater apathy and reduced FPCN connectivity (p=0.005; β=−5.42; 95% CI [−9.09, −1.75]) (see Figure 2); covariates retained in the model included sex (p=0.01, β=0.84, 95% CI [0.19, 1.49]) and SNR (p=0.02, β=−0.006, 95% CI [−0.01, −0.001]). There was also a marginal association between greater anxiety and reduced FPCN connectivity (p=0.05, β=−6.47, 95% CI [−12.98, 0.04]) (see Figure 3). Age was also retained in this model (p=0.01, β=−0.07, 95% CI [−0.13, −0.02]). Finally, there was a marginal association between greater appetite changes and reduced DMN connectivity (p=0.03; β=−2.50; 95% CI [−4.80, −0.19]). Of note, the results of the model assessing the appetite item should be interpreted with caution since only 2 of the 42 subjects had values greater than 0 for this NPI item.

Figure 2.

Adjusted partial regression plot of bilateral fronto-parietal control network connectivity vs. apathy score. The plot is adjusted for other predictors retained in the model (sex and signal-to-nose ratio). Reduced bilateral fronto-parietal control network connectivity is associated with greater apathy.

Figure 3.

Adjusted partial regression plot of bilateral fronto-parietal control network connectivity vs. anxiety score. The plot is adjusted for other predictors retained in the model (age). Reduced bilateral fronto-parietal control network connectivity is associated with greater anxiety.

Discussion

The results of our study suggest that increased affective symptoms, in particular apathy, are associated with reduced resting-state FPCN connectivity in individuals with MCI. Apathy is regarded as one of the most common symptoms of AD dementia and is highly prevalent in individuals with MCI as well [13, 14]. Previous studies have shown increased apathy to be associated with impaired activities of daily living and with a greater chance of progressing from MCI to AD dementia [5, 18, 20]. Other studies have shown relationships between increased white matter abnormalities and greater apathy in MCI, highlighting apathy-related disconnections between brain regions apparent even in early stages of cognitive disorders [24, 25, 52]. Furthermore, in individuals ranging from CN elderly to AD dementia, there are associations between apathy and cortical atrophy in frontal regions[22, 23, 53], decreased perfusion of frontal, temporal, & parietal regions[54], and reduced metabolism and perfusion of anterior cingulate cortex and orbitofrontal cortex,[8, 11] suggesting that apathy-related brain changes are not limited solely to white matter changes.

Our findings build upon previous work by suggesting greater reduction in network integrity in the FPCN for individuals with MCI who have greater apathy. The FPCN encompasses regions across the frontal and parietal cortices, which overlap with the results of previously mentioned studies. The aforementioned studies demonstrated apathy-related atrophy, decreased activity, and white matter changes in frontal, parietal, and cingulate regions, which partly overlap FPCN regions, and may underlie altered FPCN connectivity observed in our study. Alexopolous et al. found associations in cognitively normal elderly between greater depressive symptoms and decreased connectivity in the cognitive control network, which overlaps with the FPCN [30, 31]. In further analyses, greater apathy was associated with altered resting-state functional connectivity in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, one of the regions encompassed by the FPCN, and the insula [31].

In the current analyses, our exploratory factor analysis yielded two NPS factors in subjects with MCI, an Affective factor and a Hyperactivity factor. Two recent studies reported similar NPS factors using the NPI brief questionnaire form (NPI-Q), which is an abbreviated form of the NPI used in the current study, across clinically normal elderly, subjective cognitive decline, MCI, and mild AD dementia from similar but larger primarily academic center convenience samples, the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative and the Massachusetts Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center longitudinal cohort [1, 2]. On the other hand, in population-based or academic center studies primarily focused on AD dementia, there have been reports of 3 or 4 NPS factors using the NPI, with apathy often being an isolated distinct symptom, not loading on to other factors [55–57]. In our analyses, apathy was part of the Affective factor. Therefore, these differences need to be considered when interpreting the results of the current study.

This study had several limitations. Primarily, the cross-sectional design of the study does not allow for interpretation of causality; therefore, future longitudinal analyses are being planned to investigate the relationship of longitudinal NPS change and functional connectivity. Functional connectivity changes, specifically in the DMN, have shown promise as a potential biomarker for AD progression; therefore it is possible that if changes in the FPCN track well with increased apathy symptoms over time, these changes may also coincide with further progression to AD dementia [58]. Second, some NPS, such as apathy, were endorsed in relatively few subjects, giving the appearance of outliers. However, the prevalence of apathy in this sample was comparable to other MCI cohorts, indicating that these data points are clinically relevant signals rather than outliers within our study sample. Of note, the frequencies of irritability, anxiety, and depression in our study were higher compared to prior studies. Since our sample was small, it is likely that frequencies of NPS in MCI are better represented by larger studies. That said, the most common NPS in our study were similar to those previously reported in larger studies. Third, we did not account for use of antidepressants, anxiolytics, or other psychotropic medications or cognitive enhancing medications such as cholinesterase inhibitors, in these analyses. For instance, antidepressant medication use may have been an undetected influence on the relations of NPS such as depression and connectivity within the DMN, a network that has previously been implicated in both depression and AD progression. As such, in our analyses we did not detect a significant association between DMN connectivity and the Affective factor symptoms or depression in particular. However, our sample size limited the number of covariates we could include in our models and the ability to detect a potential effect modification based on medication usage. That said, due to the partly exploratory nature of the study, a large number of predictors were used in the various models in order to determine the relevant NPS and networks, while accounting for known confounds. Therefore, backward elimination linear regression was employed in order to reduce the bias in final model selection. Moreover, for the secondary analyses looking at individual affective factor symptoms, a stricter cut-off was used for significance (p<0.01) as a correction for multiple comparisons. Fourth, in this particular analysis we must be cautious in over-generalizing our results, as the age range of subjects was wide and there was a lot of clinical overlap between various neuropsychiatric symptoms (e.g., apathy and depression). On the other hand, apathy has been shown to be a distinct clinical construct from depression in AD, and in our secondary analyses apathy (and not depression) appeared to be driving the association with reduced FPCN connectivity [59].

In conclusion, this study showed an association between greater affective symptoms, primarily apathy, and decreased FPCN connectivity in elderly subjects with amnestic MCI suggestive of early AD. This association was independent of age, sex, premorbid IQ, memory, and processing speed. Future cross-sectional and longitudinal studies will help further elucidate the link between FPCN connectivity and apathy and related affective symptoms.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by R01 AG027435, K23 AG033634, K24 AG035007, R03 AG045080, the Rosalinde and Arthur Gilbert Foundation/AFAR New Investigator Awards in Alzheimer’s Disease, the Massachusetts Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (P50 AG005134), and the Harvard Aging Brain Study (P01 AGO36694, R01 AG037497). Authors have also received research salary support from the Harvard Medical School Department of Psychiatry Dupont-Warren Fellowship and Livingston Award and the Harvard Medical School Scholars in Medicine Office.

The authors have received research salary support from Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy (GAM, REA), Wyeth/Pfizer Pharmaceuticals (GAM, REA), Eisai Inc. (GAM), Eli Lilly and Company (GAM), Avid Radiopharmaceuticals (KAJ), and Bristol-Myers-Squibb (GAM, RAS).

References

- 1.Wadsworth L, Lorius N, Donovan N, Locascio J, Rentz D, Johnson K, Sperling R, Marshall G. Neuropsychiatric symptoms and global functional impairment along the Alzheimer's continuum. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2012;34:15. doi: 10.1159/000342119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Donovan NJ, Amariglio RE, Zoller AS, Rudel RK, Gomez-Isla T, Blacker D, Hyman BT, Locascio JJ, Johnson KA, Sperling RA, Marshall GA, Rentz DM. Subjective cognitive concerns and neuropsychiatric predictors of progression to the early clinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2014.02.007. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tschanz J, Corcoran C, Schwartz S, Treiber K, Green R, Norton M, Mielke M, Piercy K, Steinberg M, Rabins P, Leoutsakos J, Welsh-Bohme rK, Breitner J, Lyketsos C. Progression of cognitive, functional, and neuropsychiatric symptom domains in a population cohort with Alzheimer dementia: the cache county dementia progression study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;19:10. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181faec23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Monastero R, Mangialasche F, Camarda C, Ercolani S, Camarda R. A systematic review of neuropsychiatric symptoms in mild cognitive impairment. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;18:19. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Palmer K, Lupo F, Perri R, Salamone G, Fadda L, Caltagirone C, Musicco M, Cravello L. Predicting disease progression in Alzheimer's disease: the role of neuropsychiatric syndromes on functional and cognitive decline. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;24:10. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-101836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Donovan N, Wadsworth L, Lorius N, Locascio J, Rentz D, Johnson K, Sperling R, Marshall G, Initiative ADN. Regional cortical thinning predicts worsening apathy and hallucinations across the Alzheimer’s disease spectrum. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;13:2. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guercio B, Donovan NJ, Ward A, Schultz A, Lorius N, Amariglio RE, Rentz DM, Johnson KA, Sperling RA, Marshall GA. Apathy is associated with lower inferior temporal cortical thickness in mild cognitive impairment and normal elderly. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.13060141. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marshall GA, Monserratt L, Harwood D, Mandelkern M, Cummings JL, Sultzer DL. Positron emission tomography metabolic correlates of apathy in Alzheimer disease. Archives of Neurology. 2007;64:1015–1020. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.7.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robert P, Darcourt G, Koulibaly M, Clairet S, Benoit M, Garcia R, Dechaux O, J D. Lack of initiative and interest in Alzheimer's disease: a single photon emission computed tomography study. Eur J Neurol. 2006;13:6. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosen H, Allison S, Schauer G, Gorno-Tempini M, Weiner M, Miller B. Neuroanatomical correlates of behavioural disorders in dementia. Brain. 2005;128:13. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benoit M, Clairet S, Koulibaly P, Darcourt J, Robert P. Brain perfusion correlates of the apathy inventory dimensions of Alzheimer's disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;19:5. doi: 10.1002/gps.1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lyketsos C, Lopez O, Jones B, Fitzpatrick A, Breitner J, DeKosky S. Prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia and mild cognitive impairment: results from the cardiovascular health study. JAMA. 2002;288:8. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.12.1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mega M, Cummings J, Fiorello T, Gornbein J. The spectrum of behavioral changes in Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1996;46:5. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.1.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Apostolova L, Cummings J. Neuropsychiatric manifestations in mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review of the literature. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2008;25:11. doi: 10.1159/000112509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brodaty H, Heffernan M, Draper B, Reppermund S, Kochan N, Slavin M, Trollor J, Sachdev P. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in older people with and without cognitive impairment. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;31:9. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-120169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aarsland D, Taylor J, Weintraub D. Psychiatric issues in cognitive impairment. Mov Disord. 2014;29:2. doi: 10.1002/mds.25873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geda Y, Roberts R, Mielke M, Knopman D, Christianson T, Pankratz V, Boeve B, Sochor O, Tangalos E, Petersen R, Rocca W. Baseline neuropsychiatric symptoms and the risk of incident mild cognitive impairment: a population-based study. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171:9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13060821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boyle P, Malloy P, Salloway S, Cahn-Weiner D, Cohen R, Cummings J. Executive dysfunction and apathy predict functional impairment in Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;11:7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McPherson S, Fairbanks L, Tiken S, Cummings J, Back-Madruga C. Apathy and executive function in Alzheimer's disease. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2002;8:8. doi: 10.1017/s1355617702813182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marshall GA, Rentz DM, Frey MT, Locascio JJ, Johnson KA, Sperling RA, Initiative AsDN. Executive function and instrumental activities of daily living in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2011;7:300–308. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stella F, Radanovic M, Aprahamian I, Canineu P, de Andrade L, Forlenza O. Neurobiological correlates of apathy in Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment: a critical review. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;39:15. doi: 10.3233/JAD-131385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Apostolova L, Akopyan G, Partiali N, Steiner C, Dutton R, Hayashi K, Dinov I, Toga A, Cummings J, Thompson P. Structural correlates of apathy in Alzheimer's disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2007;24:6. doi: 10.1159/000103914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bruen P, McGeown W, Shanks M, Venneri A. Neuroanatomical correlates of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2008;131:8. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cacciari C, Moraschi M, Di Paola M, Cherubini A, Orfei M, Giove F, Maraviglia B, Caltagirone C, Spalletta G. White matter microstructure and apathy level in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;20:6. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jonsson M, Edman A, Lind K, Rolstad S, Sjögren M, Wallin A. Apathy is a prominent neuropsychiatric feature of radiological white-matter changes in patients with dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;25:7. doi: 10.1002/gps.2379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garcés P, Pineda-Pardo J, Canuet L, Aurtenetxe S, López M, Marcos A, Yus M, Llanero-Luque M, Del-Pozo F, Sancho M, Maestú F. The Default Mode Network is functionally and structurally disrupted in amnestic mild cognitive impairment - A bimodal MEG-DTI study. Neuroimage Clin. 2014;6:7. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gonzalez-Escamilla G, Atienza M, Garcia-Solis D, Cantero J. Cerebral and blood correlates of reduced functional connectivity in mild cognitive impairment. Brain Struct Funct. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00429-014-0930-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ranasinghe K, Hinkley L, Beagle A, Mizuiri D, Dowling A, Honma S, Finucane M, Scherling C, Miller B, Nagarajan S, Vossel K. Regional functional connectivity predicts distinct cognitive impairments in Alzheimer's disease spectrum. Neuroimage Clin. 2014;5:10. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2014.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Balthazar M, Pereira F, Lopes T, da Silva E, Coan A, Campos B, Duncan N, Stella F, Northoff G, Damasceno B, Cendes F. Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Alzheimer’s Disease Are Related to Functional Connectivity Alterations in the Salience Network. Hum Brain Mapp. 2013;35:9. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alexopoulos G, Hoptman M, Kanellopoulos D, Murphy C, Lim K, Gunning F. Functional connectivity in the cognitive control network and the default mode network in late-life depression. J Affect Disord. 2012;139:9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yuen G, Gunning-Dixon F, Hoptman M, Bassem A, McGovern A, Seirup J, Alexopoulos G. The salience network in the apathy of late-life depression. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014:8. doi: 10.1002/gps.4171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhong Y, Huang L, Cai S, Zhang Y, von Deneen K, Ren A, Ren J, Initiative AsDN. Altered effective connectivity patterns of the default mode network in Alzheimer's disease: An fMRI study. Neurosci Lett. 2014;578C:4. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2014.06.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weiler M, Fukuda A, Massabki L, Lopes T, Franco A, Damasceno B, Cendes F, Balthazar M. Default mode, executive function, and language functional connectivity networks are compromised in mild Alzheimer's disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2014;11:8. doi: 10.2174/1567205011666140131114716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li R, Wu X, Fleisher A, Reiman E, Chen K, Yao L. Attention-related networks in Alzheimer's disease: a resting functional MRI study. Hum Brain Mapp. 2012;33:12. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neufang S, Akhrif A, Riedl V, Förstl H, Kurz A, Zimmer C, Sorg C, Wohlschläger A. Disconnection of frontal and parietal areas contributes to impaired attention in very early Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;25:22. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-102154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cummings J, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg-Thompson S, Carusi D, Gornbein J. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994;44:6. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.12.2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosen W, Terry R, Fuld P, Katzman R, Peck A. Pathological verification of ischemic score in differentiation of dementias. Ann Neurol. 1980;7:2. doi: 10.1002/ana.410070516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yesavage J, Brink T, Rose T, Lum O, Huang V, Adey M, Leirer V. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1982;17:13. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Petersen R. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. J Intern Med. 2004;256:11. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wechsler D. Manual for the Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Folstein M, Folstein S, McHugh P. "Mini-mental state". A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:9. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morris J. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43:2. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cummings J. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: assessing psychopathology in dementia patients. Neurology. 1997;48:6. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.5_suppl_6.10s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nelson HE. National Adult Reading Test (NART): Test Manual. Windsor: NFER-Nelson; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wechsler D. WAIS-R Manual: Wechsler adult intelligence scale - revised. The Psychological Corporation; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rey A. L'examen clinique en psychologie. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Freire L, Mangin J. Motion correction algorithms may create spurious brain activations in the absence of subject motion. NeuroImage. 2001;14:13. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Freire L, A R, Mangin J. What is the best similarity measure for motion correction in fMRI time series? IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2002;21:14. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2002.1009383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yeo B, Krienen F, Sepulcre J, Sabuncu M, Lashkari D, Hollinshead M, Roffman J, Smoller J, Zöllei L, Polimeni J, Fischl B, Liu H, Buckner R. The organization of the human cerebral cortex estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity. J Neurophysiol. 2011;106:45. doi: 10.1152/jn.00338.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dosenbach N, Fair D, Miezin F, Cohen A, Wenger K, Dosenbach R, Fox M, Snyder A, Vincent J, Raichle M, Schlaggar B, Petersen S. Distinct brain networks for adaptive and stable task control in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704320104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Day G, Farb N, Tang-Wai D, Masellis M, Black S, Freedman M, Pollock B, Chow T. Salience network resting-state activity: prediction of frontotemporal dementia progression. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70:4. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.3258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim J, Lee D, Choo I, Seo E, Kim S, Park S, Woo J. Microstructural alteration of the anterior cingulum is associated with apathy in Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;19:10. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31820dcc73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tunnard C, Whitehead D, Hurt C, Wahlund L, Mecocci P, Tsolaki M, Vellas B, Spenger C, Kloszewska I, Soininen H, Lovestone S, Simmons A, Consortium A. Apathy and cortical atrophy in Alzheimer's disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;26:7. doi: 10.1002/gps.2603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ott B, Noto R, Fogel B. Apathy and loss of insight in Alzheimer's disease: a SPECT imaging study. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1996;8:5. doi: 10.1176/jnp.8.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Frisoni GB, Rozzini L, Gozzetti A, Binetti G, Zanetti O, Bianchetti A, Trabucchi M, Cummings JL. Behavioral syndromes in Alzheimer's disease: description and correlates. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 1999;10:8. doi: 10.1159/000017113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lyketsos C, Steinberg M, Tschanz J, Norton M, Steffens D, Breitner J. Mental and behavioral disturbances in dementia: findings from the Cache County Study on Memory in Aging. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:6. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.5.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lyketsos C, JC B, PV R. An evidence-based proposal for the classification of neuropsychiatric disturbance in Alzheimer's disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;16:5. doi: 10.1002/gps.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Damoiseaux J. Resting-state fMRI as a biomarker for Alzheimer's disease? Alzheimers Res Ther. 2012;4:1. doi: 10.1186/alzrt106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Levy M, Cummings JL, Fairbanks L, Masterman D, Miller B, Craig A, Paulsen J, Litvan I. Apathy is not depression. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1998;10:5. doi: 10.1176/jnp.10.3.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]