Abstract

The relationship between level of childhood abuse (physical and emotional) and sexual risk behavior of sexually transmitted disease (STD) clinic patients in St. Petersburg, Russia was examined through path analyses. Mediating variables investigated were: Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT), drinking motives (for social interaction, to enhance mood, to facilitate sexual encounters), intimate partner violence (IPV), anxiety, and depression symptoms. Results showed a significant indirect effect of childhood abuse on women’s sexual risk behavior: higher level of childhood abuse was associated with a greater likelihood of IPV, motivations to drink, leading to higher AUDIT scores and correlated to higher likelihood of having multiple, new or casual sexual partner(s). No significant effect was identified in paths to condom use. Among men, childhood abuse had no significant effect on sexual risk behavior. Reduction in alcohol-related sexual risk behavior may be achieved by addressing the effects of childhood abuse among female participants.

Keywords: Physical and emotional childhood abuse history, HIV risk, STD clinic patients, alcohol use, drinking motives

INTRODUCTION

Russia has one of the fastest growing HIV rates in the world [1]. Between 2001 and 2011, the HIV prevalence increased from 0.2% to 0.5% among young women aged 15–25 and from 0.3% to 0.7% among young men aged 15–25 [2]. The number of people living with HIV relative to the general population in Russia is estimated to be between 0.8 and 1.4 percent and this number is steadily increasing [3]. High risk sexual contact is responsible for approximately one third of reported new HIV infections [1]. Thus, understanding the distal factors associated with risky sexual behavior has profound implications for the design of successful intervention programs to reduce the risk factors for sexual HIV transmission.

Significant association exists between sexual risk behavior and a history of child abuse, including physical, sexual and emotional abuse [4]. Child abuse occurs in every country, at every socioeconomic level, and across all ethnic, religious, and cultural lines [5]. In the United States alone, during 2012, an estimated 3.2 million child victims of abuse were screened appropriate for Child Protection Service response [6]. The long-term impact of abuse in childhood can be devastating to the adult survivor, with effects encompassing symptoms of anxiety and depression, and difficulties with emotional regulation and self-efficacy [7–9]. Because childhood abuse histories are common among people living with HIV and there are disproportionate rates of HIV infection among survivors of childhood abuse [10,11], a history of childhood abuse may be a significant predictor of HIV risk behavior.

Studies have demonstrated that a history of abuse in childhood may result in vulnerabilities for sexual risk behavior in adulthood, such as an earlier age for initiating sexual activity, increased number of sexual partners, and sexually transmitted diseases [7,12–14]. The link between childhood abuse and sexual risk behavior can be mediated by the well-established sequelae of childhood abuse, such as depression and anxiety [8]. Abuse history has also been shown to increase the risk for engagement in intimate partner violence (IPV) and to potentiate the risk for the onset and development of substance use disorders in adolescents and young adults [12], which in turn increase the likelihood for sexual risk taking. A study among 827 STD clinic patients in the United States found that men and women with childhood sexual abuse (CSA) histories were more likely to engage in high risk sex in adulthood than those without CSA. The association was mediated by substance use and intimate partner violence (IPV) [15]. Thus, complex and rigorous research designs that explore the mediating and moderating variables in the nature of these relationships are warranted.

Alcohol misuse is a significant risk factor for risky sexual behavior and an important possible outcome of childhood abuse. The Russian Federation has one of the highest prevalence of alcohol consumption in the world. A study conducted in 2005 estimated the volume of pure alcohol (ethanol) consumed per person aged 15 years or older to be 6.13 liters worldwide [16]. In Russia, this number was 15.7 liters [16]. Alcohol use in conjunction with sexual activity is also highly prevalent in certain subgroups of the population. In a study conducted among 307 STD clinic patients in Russia, 82% of participants reported having consumed alcohol at the time of their most recent sexual encounter [17]. Harmful drinking has been shown to contribute to a heavy burden of disease and deaths due to injuries and violence in Russia [18]. Alcohol use is also associated with behavior that place individuals at greater risk for sexual HIV acquisition, such as increased number of sexual partners, having a sex partner who inject drugs, regretful sexual acts, decreased condom use, and STD history [19–21].

Research has shown that people drink for a variety of reasons or “motives”. Understanding why individuals are motivated to drink may be helpful in predicting alcohol use patterns and alcohol-related sexual risk behavior. One European study [22] identified two basic strands of drinking motives: (a) drinking to reduce tension, overcome stress, and regulate negative emotions, and (b) drinking for fun, pleasure, and facilitation of social contacts. The motivation to drink in order to reduce social inhibition and to facilitate sexual activity is believed by some researchers to play a role mostly in the latter category [23]. In Russia, where alcohol use is particularly accepted and even encouraged [24], it may be useful to investigate whether culturally specific drinking motives affect sexual risk and prevention behavior. Additionally, findings from Russian studies supporting the notion that alcohol use is a common facilitator of sexual encounters and a symbol of masculinity for some men [25] suggest that the investigation of gender differences in drinking motives [26,27] among people at risk for HIV may provide useful information for interventions efforts aimed at reducing alcohol use and alcohol related sexual risk behavior.

Previous research in Russia has explored the direct associations between childhood maltreatment history and IPV in the context of drinking and not drinking alcohol [28]. However, to our knowledge no study has investigated the association between childhood abuse history and sexual risk behavior in Russia. This is an initial study with a primary goal of examining the relationship between child abuse history and sexual risk behavior. Specifically, it is hypothesized that:

Level of childhood abuse (physical and emotional) is associated with sexual risk behavior (unprotected sex and multiple, new, or casual sex partners).

Alcohol misuse, drinking motives, depression/anxiety symptoms, and IPV will mediate the association between childhood abuse history and risky sexual behavior.

METHODS

Participants and Measures

The study was approved by the institutional review boards of the Biomedical Center in St. Petersburg, Russia and Yale University in Connecticut, U.S.A. Written informed consent was obtained from individuals who agreed to participate in the study and complete a computer-assisted interviewer-administered questionnaire.

From May 2011 to November 2011, consecutive men and women who sought STD services in a dermatovenereology dispensary (STD clinic) in St. Petersburg, Russia were invited to participate in a cross-sectional study that aimed to examine risk factors associated with HIV sexual risk behavior. Participation eligibility included: (1) age between 18 and 50 years, (2) sexually active during the past 6 months, (3) not trying to get pregnant or not having a sexual partner who is trying to get pregnant, and (4) biologically able to have children.

We used the questionnaire to collect information pertaining to demographic and health characteristics, alcohol consumption, motivations to consume alcohol (drinking motives), sexual behavior, history of childhood abuse and history of IPV. The questionnaire was constructed in English, translated into Russian, and then translated back into English to ensure the integrity of the syntax and meaning. Demographic information included the age at survey, marital status, highest level of education, employment status, and income level.

Outcomes (sexual risk behavior)

Participants were asked the number of sexual partners in the last three months, and whether they had a new or casual sexual partner in the past three months. Considering that some participants had a higher number of sexual partners, and that our previous studies in Russia [29,30] showed that having casual or new sex partners also play a significant role in sexual HIV risk, a variable dichotomized into whether having multiple, casual or new sexual partners or not was used in the analyses.

The measure of unprotected sex was based on the calculation of the proportion of condom use during the past three months. Participants were asked the following: 1) the number of vaginal and anal sexual intercourses with a condom in the past three months, and 2) the number of vaginal and anal sexual intercourses without a condom in the past three months. The proportion of condom use was calculated by dividing the total number of vaginal and anal sexual intercourses with a condom by the total number of vaginal and anal sexual intercourses that they had during that time period.

Main predictor (experience of childhood abuse)

We assessed the experience of childhood abuse from two aspects—emotional abuse and physical abuse—based on two questions, respectively: “During your first 18 years, how often did your parent or caretaker insult, swear at or threaten you?” and “How often did your parent or caretaker push, grab, pinch or beat you?”. Although we asked a question related to childhood sexual abuse, “How often did your parent or caretaker touch you in a sexual way, or had you touch him/her in a sexual way?”, only one woman disclosed having had such an experience. Thus, childhood sexual abuse was not included in the present analysis. These questions were adapted from the Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS), and the response categories were never (0 points), rarely (1 point), frequently (2 points), and way too frequently (3 points). The points from each question were added together to create an overall score for the experience of childhood abuse. The possible total score ranges from a minimum of 0 points to a maximum of 6 points. The Cronbach’s alpha for the childhood abuse score was 0.75 in the current sample and was similar for both men and women. The experience of childhood abuse was measured by an overall score rather than by four dichotomous dummy variables (i.e., experience of childhood emotional abuse only, physical abuse only, both emotional and physical abuse, and neither experience) for two main reasons: 1) only a few participants had an experience of childhood physical abuse only, as the majority of participants who had experienced childhood physical abuse also had experienced emotional abuse, and 2) an overall score for the experience of childhood abuse had more statistical power to detect associations.

Alcohol Use and Drinking Motive Measures

The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) was used to identify the level of alcohol use over the past three months [18]. Participants were asked 10 questions from three domains: quantity and frequency of alcohol use, dependence symptoms, and other alcohol-related problems.

Questions related to drinking motives were selected from existing measures [31,32] based on how colloquial they sounded in Russian language and without a focus on whether they represented drinking motivations or expectancies. Participants were asked: “In the past three months, how often did you drink alcohol for the following reasons?” Responses were grouped into five domains related to: (1) social interactions: “ to be sociable”, “to better enjoy a party”, “to celebrate special occasions with friends”; (2) conformity: “to be liked”, “to fit in with a group”, “ not to feel left out”; (3) enhancement: “to have a lot of fun”, “because it gives a pleasant feeling”, “to get high or drunk (or to pass out)”; (4) coping: “to forget about problems”, “to feel less depressed or nervous”, “to cheer up when in a bad mood”; (5) facilitation of sexual contacts: “to incline or persuade my partner to have sexual intercourse”, “to create a romantic mood for my relationship with my partner”, “to enjoy sex more”, “to feel more attractive or charming (or sexier)”. The response categories were never (0 points), rarely (1 point), sometimes (2 points), often (3 points), and always (4 points). The sum scores of each subset of drinking motives were used to determine internal consistencies using Cronbach’s alpha. Items correlated sufficiently to justify the creation of three subscales, (1) drinking for social interaction (two items = first two questions; α=0.71), (2) drink to enhance mood (6 items combining enhancement and coping motives; α=0.78), (3) drink to facilitate sex (3 items, excluding “drink to enjoy sex more”, α=0.66). Cronbach’s alpha was similar for both men and women. Items regarding motivation for the conformity subscale were excluded from further analyses due to low inter-item reliability.

Other covariates

IPV was defined as having ever been (a) insulted, sworn at, or threatened by a sexual partner; (b) pushed, grabbed, slapped, punched, beaten up, or choked by a sexual partner; or (c) physically forced to have sex or to do something sexually that the participant did not want to do. These partner violence items were adapted from the CTS and have been successfully used in Russia to measure IPV. Participants who answered with “yes” to any of the items were classified as having IPV.

The ten-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D-10) [33] and the seven-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) [34] were used to identify self-reported symptoms associated with depression and anxiety, respectively, in the two weeks prior to the study. The CES-D-10 and the GAD-7 consists of ten and seven statements, respectively with four options each. The options are “not at all or less than 1 day”, “several days”, “more than half of the days”, and “nearly every day” and are given a score of 0, 1, 2 and 3, respectively. We measured both CESD-10 and GAD-7 in the analysis because GAD and depression symptoms have been shown to have independent effects on functional impairment and factor analysis confirms them as distinct dimensions.

Only 1.3% (4/299) had ever injected illicit drugs; thus, drug injection was not included in the analyses.

Statistical methods

The characteristics and outcomes of the cohort were described using means and standard deviations for continuous variables, or frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. T-test or Chi-square test was used for group comparisons. Cronbach’s alpha was used to evaluate the internal reliability of the drinking motives scales and the child abuse score. Pearson’s correlation was used to examine the correlations among outcomes and to create the correlation matrix.

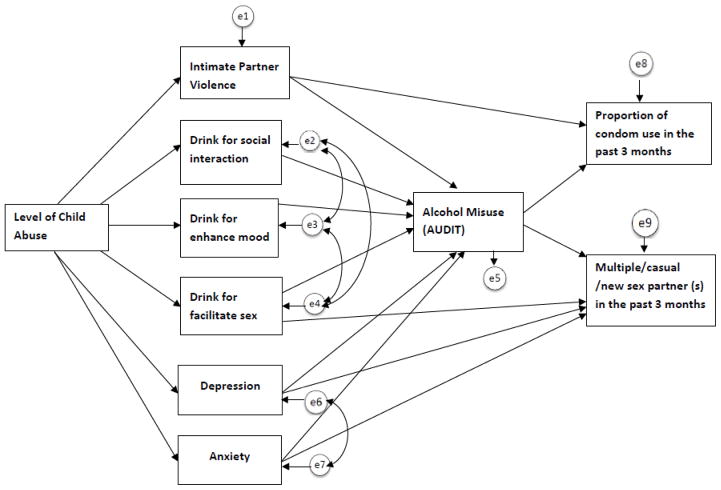

We hypothesized that the level of childhood abuse has a positive impact on HIV risk behavior through the path of increasing IPV, drinking motives, depression and anxiety. A hypothetical model was shown in Figure 1 proposing the mediation effects on the association between childhood abuse and sexual risk behavior. Path analysis was performed to examine whether the proposed model can simultaneously fit the multiple correlations among the targeted variables. The overall fit of the model was determined by the following indices and criteria [35,36]. The goodness-of-fit Chi-square > 0.05, the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) > 0.95, the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) > 0.95, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) < 0.06, and the weighted root mean square residual (WRMR) < 0.9. Further model modification within the framework of the priori model was conducted to improve the model fit based on modification indices. Path analysis was performed using weighted least square measurement means and variance adjusted (WLSMV) estimation with M-Plus 5.0 [37]. The analysis was first done in a multiple-group framework to test for the cross-gender invariance. Two nested models were fitted separately: 1) a baseline model without any constraints in model parameters; and 2) a constrained model in which all the paths were forced to be equal between genders. A robust nested Chi-square difference test was used to determine if the series of path coefficients was statistically significantly different by gender. A significant p value (0.05) means that the restrictive model has worse model fit, which warrants the stratification of the path model by gender. Since the Chi-square difference test of multiple-group analysis resulted in a significant worsening fit (χ2/df =1.84, p=0.036), indicating that the null hypothesis of path effects consistent across gender was rejected, further stratified path analyses were performed among both women and men. All models were run with or without being controlled for age. Because there was little difference between the controlled and uncontrolled models—and for the sake of simplicity—the models not controlled for age were presented. The standardized coefficients were reported. The other analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 (Cary, NC). The significance level was set as p value < 0.05, two-sided.

Figure 1.

Hypothetical path model

RESULTS

A total of 501 participants (299 women and 202 men) were included in the analysis (Table 1). The prevalence of participants reporting a positive HIV status, drug injection, having sex with a person of the same gender in the past three months, or receiving or giving money or valuables in exchange for sex was below 4% each. Therefore these variables were not controlled for in our analysis. The average age of the study sample was 27.2 ± 7.6 years old (mean ± SD). Among the participants, 49% of women completed post-secondary education compared to 37% of men (P = 0.007). There was no significant difference by gender in childhood abuse experience, symptoms of depression and anxiety, and reported condom use in the past 3 months. However, women reported significantly more IPV than men (47.5% vs.33.3%, p=0.005), smaller AUDIT scores (4.6 ± 5.0 vs. 8.5 ± 6.7, p < .0001), and lower drink motives scores including social, mood and sexual motives subscales. Further, women reported a significantly lower number of multiple/new/causal sexual partners in the past 3 months than did men (29% vs. 49%, p < .0001).

Table 1.

Summary of characteristics and outcomes. Data are presented as N (%) for categorical variables and Mean (SD) for continuous variables.

| Variables | Women | Men | All | Test stats* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=299 | N=202 | N=501 | ||

| Age | 27.9 (± 7.8) | 26.2 (± 7.1) | 27.2 (± 7.6) | t(500) = 2.6, 0.01 |

| Completed post-secondary education | 146 (48.8) | 74 (36.6) | 220 (43.9) | X2(1) = 7.1, 0.007 |

| Married | 149 (49.8) | 78 (38.6) | 227 (45.3) | X2(1) = 5.9, 0.01 |

| Childhood abuse | X2(2) = 3.4, 0.19 | |||

| At least physical abuse | 72 (24.1) | 60 (29.9) | 132 (26.4) | |

| Emotional abuse only | 118 (39.5) | 82 (40.8) | 200 (40.0) | |

| None | 109 (36.5) | 59 (29.4) | 168 (33.6) | |

| Level of childhood abuse | 1.1 (± 1.1) | 1.1 (± 1.0) | 1.1 (± 1.1) | t(498) = −0.5, 0.59 |

| IPV | 142 (47.5) | 67 (33.3) | 209 (42) | X2(1) = 9.9, 0.005 |

| CESD-10 (depression scale) | 8.5 (± 3.5) | 8.2 (± 3.1) | 8.4 (± 3.3) | t(498)= 1.0, 0.32 |

| GAD-7 (Anxiety) | 4.9 (± 4.0) | 4.2 (± 3.4) | 4.6 (± 3.8) | t(498)= 2.3, 0.02 |

| AUDIT | 4.6 (± 5.0) | 8.5 (± 6.7) | 6.2 (± 6.0) | t(498)=−7.0, <.0001 |

| Drink for social interaction | 5.9 (± 3.1) | 6.6 (± 3.8) | 2.4 (± 2.3) | t(461)= −2.2, 0.004 |

| Drink to enhance mood | 3.0 (± 2.5) | 3.4 (± 3.0) | 4.7 (± 3.7) | t(461)= −1.6, 0.03 |

| Drink to facilitate sexual encounters | 1.2(± 1.6) | 1.7 (± 1.8) | 1.4 (± 1.7) | t(461)= −3.3, 0.001 |

| Multiple/new/casual partner last 3m | 87 (29.1) | 98 (48.8) | 185 (37.0) | X2(1) = 19.9, <.0001 |

| Proportion of condom use last 3months | 0.5 (± 0.5) | 0.5 (± 0.4) | 0.5 (± 0.4) | t(497)= 0.4, 0.71 |

Test statistics refers to chi-square (df), p-value or t-test (df), p-value

Correlation analyses among women (Table 2A) showed that level of childhood abuse was significantly correlated to IPV, drinking motivation, AUDIT, and having multiple/new/casual partner(s) in the past 3 months, but did not correlate with depression, anxiety, and condom use in the past 3 months. Among men (Table 2B), similar significant correlations were observed between childhood abuse and drinking motivation, and between AUDIT and multiple/new/casual sexual partner(s). However, there were significant correlations between childhood abuse and anxiety or depression among men. Compared to women, the correlation between childhood abuse and IPV became marginally significant (p=0.07) in men, and there was no correlation between IPV and multiple/new/casual partner(s) in the past 3 months (p=0.69).

Table 2.

Correlation matrix showing correlations between outcomes and predictors stratified by gender. Upper panel: correlation coefficients. Lower panel: p values.

| A) Women | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| 1. Level of childhood abuse | 0.21 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.11 | −0.03 |

| 0.0002 | 0.23 | 0.57 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.048 | 0.59 | |

| 2. Intimate Partner Violence (IPV Yes/No) | 0.16 | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.24 | 0.11 | 0.31 | 0.14 | 0.08 | |

| 0.004 | 0.07 | 0.004 | <.0001 | 0.08 | <.0001 | 0.01 | 0.18 | ||

| 3. Anxiety Symptoms (GAD-7) | 0.71 | 0.19 | 0.35 | 0.23 | 0.33 | 0.19 | −0.01 | ||

| <.0001 | 0.002 | <.0001 | 0.0001 | <.0001 | 0.001 | 0.85 | |||

| 4. Depression Symptoms (CESD-10) | 0.11 | 0.26 | 0.18 | 0.26 | 0.08 | −0.06 | |||

| 0.06 | <.0001 | 0.003 | <.0001 | 0.17 | 0.30 | ||||

| 5. Drink for social interaction | 0.62 | 0.54 | 0.41 | 0.23 | −0.06 | ||||

| <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.28 | |||||

| 6. Drink to enhance mood | 0.45 | 0.43 | 0.23 | −0.07 | |||||

| <.0001 | <.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.27 | ||||||

| 7. Drink to facilitate sexual encounters | 0.29 | 0.23 | −0.08 | ||||||

| <.0001 | <.0001 | 0.21 | |||||||

| 8. Alcohol misuse (AUDIT) | 0.30 | −0.01 | |||||||

| <.0001 | 0.80 | ||||||||

| 9. Multiple/casual/new sexual partner(s) last 3 months | 0.11 | ||||||||

| 0.049 | |||||||||

| 10. Proportion of condom use last 3 months | - | ||||||||

| - | |||||||||

| B) Men | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| 1. Level of childhood abuse | 0.13 | 0.26 | 0.31 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.05 |

| 0.07 | 0.0002 | <.0001 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.48 | |

| 2. Intimate Partner Violence (IPV Yes/No) | 0.20 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.19 | 0.03 | −0.01 | |

| 0.004 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.38 | 0.28 | 0.01 | 0.69 | 0.86 | ||

| 3. Anxiety Symptoms (GAD-7) | 0.58 | 0.29 | 0.46 | 0.19 | 0.23 | 0.09 | 0.05 | ||

| <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | 0.01 | 0.001 | 0.23 | 0.52 | |||

| 4. Depression Symptoms (CESD-10) | 0.30 | 0.33 | 0.34 | 0.17 | 0.10 | 0.16 | |||

| <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | 0.02 | 0.17 | 0.02 | ||||

| 5. Drink for social interaction | 0.54 | 0.47 | 0.26 | 0.11 | 0.02 | ||||

| <.0001 | <.0001 | 0.0003 | 0.12 | 0.75 | |||||

| 6. Drink to enhance mood | 0.43 | 0.53 | 0.11 | −0.07 | |||||

| <.0001 | <.0001 | 0.15 | 0.36 | ||||||

| 7. Drink to facilitate sexual encounters | 0.25 | 0.07 | 0.02 | ||||||

| 0.001 | 0.34 | 0.75 | |||||||

| 8. Alcohol misuse (AUDIT) | 0.27 | −0.05 | |||||||

| 0.0001 | 0.46 | ||||||||

| 9. Multiple/casual/new sexual partner(s) last 3 months | 0.18 | ||||||||

| 0.01 | |||||||||

| 10. Proportion of condom use last 3 months | - | ||||||||

Since the hypothetical model (Figure 1) did not achieve acceptable fit on data, an improved model was developed within the theoretical frame of the original model based on modification indices. An excellent fit was achieved in women (Figure 2A), with Chi-square p value = 0.13 (χ2/df =1.48), CFI = 0.99, TFI = 0.98, RMSEA = 0.04 and WRMR = 0.65 with a model showing significant indirect effect of childhood abuse on multiple/new/casual partner(s) mediated through IPV, all three drinking motives, and then through alcohol misuse. A higher level of childhood abuse was associated with an increased likelihood of IPV, greater motivation to drink for social interaction, to enhance mood and to facilitate sexual encounters, which led to a higher alcohol misuse score, and correlated to a higher likelihood of having multiple/new/casual sexual partner(s). Anxiety had a similar indirect effect on multiple/new/casual sexual partner(s) mediated by IPV, all three drinking motives and then alcohol misuse. Paths to condom use were evaluated as well, but no significant effect was identified. When controlling for age, all path coefficients remained similar. The only effect of age was observed in the path from level of child abuse, to drink to facilitate sex (Standardized coefficient = 0.13. p=0.04), indicating that older age was associated with greater motivation to facilitate sexual encounters among women.

Figure 2.

Final path models showing the mediation path of the impact of level of child abuse on HIV sexual risk in women and men.

The same model among men showed a Chi-square p value of 0.002, indicating a significant discrepancy between the model and observed data. The other fit indices included CFI = 0.92, TLI = 0.86, RMSWA = 0.09 and WRMR = 0.87, suggesting that the path model for women did not reach a good fit on the data of men. For the sake of clarity, an improved model with only significant coefficients is shown in Figure 2B [Chi-square p value = 0.17 (p > 0.05); CFI = 0.98 and TLI = 0.97; RMSEA = 0.05 and WRMR = 0.67]. Among men, the level of childhood abuse was not significantly associated with any of the investigated variables. The model showed significant indirect effect of anxiety on multiple/new/casual partner(s) mediated through IPV and/or drinking to enhance mood, and then through alcohol misuse. Depression symptoms had no significant effect on multiple/new/casual sexual partner(s) or alcohol misuse. Paths to condom use were evaluated as well, but no significant effect was identified. Among men, the analysis controlled for age showed no statistically significant effect of age in any of the paths.

DISCUSSION

Our results provide support for the hypothesis that the level of childhood abuse contributes to current HIV sexual risk behavior among women. This is consistent with previous findings showing that the cumulative number of lifetime victimizations was highly predictive of symptoms of current distress among a national sample of 1,467 children aged 2–17 living in the United States [38]. Most participants who experienced physical abuse also experienced emotional abuse, confirming evidence that the various forms of maltreatment often co-occur. A study of a nationally representative sample of 4053 children aged 2–17 years conducted in 2008 in the United States, revealed that almost 66 percent of the sample experienced 2 or more types of violence over the course of their lifetimes [39]. This co-occurrence can be explained by their shared etiology, since risk factors for one type of abuse (e.g., parental mental illness, parental lack of impulse control, poor parenting skills, life stressors) are also risk factors for other types of abuse [40]. Our results also support a second hypothesis that physical and/or emotional childhood abuse has a significant indirect effect on the sexual risk behavior of adult women. Although this is consistent with previous observations [9], it is a relevant finding given that the literature on this relation is much less extensive than the literature on the relation between childhood sexual abuse and adult sexual risk behavior [41]. These findings indicate that interventions that prevent childhood abuse (physical and/or emotional) or that reduce its consequences might also reduce HIV risk among female women at risk for HIV in Russia. For example, HIV prevention programs that focus on developing condom use, self-efficacy and negotiation skills to people who experienced abuse in childhood may benefit from addressing related issues that are commonly observed among this population, such as a reduced sense of entitlement and difficulty setting boundaries [42]. To date, HIV risk reduction programs that address issues related to the sequelae of childhood abuse, such as coping with stress, problem solving, and transmission risk behavior, have been designed for individuals and families affected by HIV [43,44]. Similar programs are needed for populations at risk for HIV acquisition.

Significant gender differences were observed in the path models of abuse history to sexual risk behavior, despite a lack of difference in the prevalence of childhood abuse history between men and women study participants. That the associations between sexual risk and childhood abuse might be moderated by gender is consistent with evidence in the literature that sexual risk behavior [29,30], IPV [45], and drinking patterns and motivations [46,47] may vary by gender. For example, a study investigating the association between depression symptoms and alcohol use found that this relationship observed a non-linear U-shaped relationship among men and a linear trend among women [48]. The findings suggest that interventions to reduce alcohol related sexual risk behavior in Russia may benefit from being tailored according to gender.

In the path model of women, drinking motives, regardless of the type of motive, were related to child abuse history and to sexual risk through alcohol misuse, suggesting that interventions that address the effects of childhood abuse and drinking motives among women might also reduce alcohol misuse and alcohol related sexual risk behavior. In the path model of men, there was only a marginal association between drinking to facilitate sexual encounter and childhood abuse, but this motive was not associated with alcohol misuse and subsequent sexual risk. The lack of association could be due to various reasons, such as a high prevalence of alcohol misuse among this population (regardless of drinking motives and abuse history), culturally acceptable drinking patterns exerting a confounding effect in drinking motives among men, differences in coping styles of men leading to men engaging in other types of risk behavior rather than sexual risk, or additional mitigating factors not analyzed in this study that could play a significant role in men’s rather than in women’s behavior [49–52]. Despite the different association between drinking motivations, childhood abuse, and sexual risk behavior among men and women, the findings suggest that self-reported motivations may serve as a marker to identify and target individuals which are at risk and in need of prevention efforts. Future studies to characterize drinking motivation profiles more broadly and to identify salient motivations associated with changes in sexual behavior are warranted among this population.

Contrary to our expectations, GAD and depression symptoms were not associated with child abuse history. GAD was significantly associated with drinking motives, alcohol use, and sexual risk behavior among men and women, whereas depression had no such effect among men or among women. This is consistent with observations that despite a high correlation, GAD and depression symptoms may have differing and independent effects on outcomes [34]. The results suggest that engagement in risk behavior may have been driven by a desire to cope with negative affect (anxiety) among men as well as among women. The result showing that drinking to enhance mood is associated with sexual risk behavior among men and women supports this possibility. Thus, interventions to reduce alcohol related sexual risk behavior among this population may benefit from focusing on teaching participants to manage mood in more healthy ways.

The paths to unprotected sex and having multiple, new or casual sexual partners were distinct and had no overlapping mediators, confirming other researchers’ suggestions that the path to unprotected sex may reflect multiple underlying processes that are predominantly non-causal rather than causal in nature [53]. Studies have shown that the relationship between alcohol and condom use may appear to be inconsistent (significant in some studies, not significant in other studies) because it depends on context and sexual experience of the partners [54,55]. That is, alcohol may be associated with lower rates of condom use only under circumscribed conditions: at first intercourse but not on subsequent intercourse occasions, in younger but not older individuals, and in the investigation of earlier rather than recent condom use. These results emphasize findings showing that efforts aimed at reducing alcohol related sexual risk behavior may decrease some forms of risky sex and are less likely to affect protective behavior directly.

IPV was a significant mediator of alcohol related sexual risk behavior among men and women but was only associated with childhood abuse history among women. The role of IPV in mediating sexual risk behavior and childhood abuse has been shown previously [28,56] and confirms the need to address violence and relationship difficulties, whether during childhood or among intimate partners, among this population.

Several limitations of the study should be noted. This study did not seek to understand the role of different forms of childhood abuse (e.g., sexual, physical, and emotional) in sexual risk. Sexual abuse was not included in our analysis because only one woman reportedly experienced sexual abuse in childhood. Similarly, this study did not seek to understand the additive effects of physical and emotional childhood abuse in sexual risk because adequate sample sizes of individuals experiencing only physical or only emotional abuse were not available. Future studies will need to conduct such an investigation. Moreover, results might have been different had this investigation included additional types of childhood maltreatment, such as sexual abuse, neglect, and witnessing family violence. The study is cross-sectional and while our data can show correlations and possible causations among multiple variables, our data cannot prove causation. The self-reported data are likely vulnerable to recall and social desirability biases. Especially exposure to abuse in childhood or IPV that occurred several years ago may not be accurately recalled and be underreported. The misclassification resulting from these biases would likely attenuate the observed associations. This study investigated participants who did not intend to become pregnant in the near future. Results might have been different among women and partners of women with expectations of becoming pregnant. The non-random sample used in the present study and the fact that our data was collected from a single STD clinic limit the ability to generalize our results. Results might have been different among a study population with a different prevalence of individuals reporting a positive HIV status, drug injection, and engagement in homosexual or commercial sex. The cross-sectional design makes it impossible to examine bidirectional effects. Our findings may be particular to the measures used in this study. Measurement limitations include a lack of potential important covariates such as socioeconomic status indicators, relationship with parents, and desire for peer approval. In addition, situational predictors of motivations for alcohol use, sexual behavior, and their co-occurrences were not assessed. However, the current study advances the literature by including childhood abuse history, drinking motivations and sexual behavior in the same study. The strengths of the study, including its innovative questions and analytic methods, a culturally diverse sample of individuals at risk for HIV, and the high response rates help to mitigate these limitations.

CONCLUSION

This finding indicates that interventions to reduce or address the effects of childhood physical and emotional abuse may potentially reduce HIV risk among women.

Drinking motivation profiles play a significant role in the path from child abuse to sexual risk behavior among women and may be a useful tool to identify a subset of men and women at risk for HIV and alcohol misuse. A broader characterization of drinking motives is warranted among this population sample.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by Grant Number R01AA017389 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (PI: N. Abdala). Additional support was provided by the Center for Interdisciplinary Research on AIDS (NIMH P30MH062294) and the Yale AIDS International Training and Research Program “Training and Research in HIV Prevention in Russia” (5 D43 TW001028).

Footnotes

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.UNAIDS. Country progress report of the russian federation on the implementation of the declaration of commitment on hiv/aids. Moscow: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.UNAIDS. Regional fact sheet on hiv/aids. Geneva: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.UNAIDS. Global report: Unaids report on the global aids epidemic 2012. Geneva: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oshri A, Tubman JG, Burnette ML. Childhood maltreatment histories, alcohol and other drug use symptoms, and sexual risk behavior in a treatment sample of adolescents. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:S250–257. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300628. doi:210.2105/AJPH.2011.300628. Epub 302012 Mar 300628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Butchart A, Harvey AP, Mian M, Furniss T. WHO & International Society for Preventoin of Child Abuse and Neglect, editor. Preventing child maltreatment: A guide to taking action and generating evidence. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Child Welfare Information Gateway. Child maltreatment 2012: Summary of key findings. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services, Children’s Bureau; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Norman RE, Byambaa M, De R, Butchart A, Scott J, Vos T. The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2012;9:e1001349. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001349. doi:1001310.1001371/journal.pmed.1001349. Epub 1002012 Nov 1001327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Briere J, Jordan CE. Childhood maltreatment, intervening variables, and adult psychological difficulties in women: An overview. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2009;10:375–388. doi: 10.1177/1524838009339757. doi:310.1177/1524838009339757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Noll JG, Haralson KJ, Butler EM, Shenk CE. Childhood maltreatment, psychological dysregulation, and risky sexual behaviors in female adolescents. J Pediatr Psychol. 2011;36:743–752. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsr003. doi:710.1093/jpepsy/jsr1003. Epub 2011 Feb 1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mimiaga MJ, Noonan E, Donnell D, et al. Childhood sexual abuse is highly associated with hiv risk-taking behavior and infection among msm in the explore study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;51:340–348. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181a24b38. doi:310.1097/QAI.1090b1013e3181a1024b1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The NIMH Multisite HIV/STD Prevention Trial for African American Couples Group. Prevalence of child and adult sexual abuse and risk taking practices among hiv serodiscordant african-american couples. AIDS Behav. 2010;14:1032–1044. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9700-5. doi:1010.1007/s10461-10010-19700-10465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Richter L, Komarek A, Desmond C, et al. Reported physical and sexual abuse in childhood and adult hiv risk behaviour in three african countries: Findings from project accept (hptn-043) AIDS Behav. 2014;18:381–389. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0439-7. doi:310.1007/s10461-10013-10439-10467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilson HW, Widom CS. Pathways from childhood abuse and neglect to hiv-risk sexual behavior in middle adulthood. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2011;79:236–246. doi: 10.1037/a0022915. doi:210.1037/a0022915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson HW, Widom CS. An examination of risky sexual behavior and hiv in victims of child abuse and neglect: A 30-year follow-up. Health Psychol. 2008;27:149–158. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.2.149. doi:110.1037/0278-6133.1027.1032.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Senn TE, Carey MP, Vanable PA, Coury-Doniger P, Urban MA. Childhood sexual abuse and sexual risk behavior among men and women attending a sexually transmitted disease clinic. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74:720–731. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.4.720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.WHO/Europe. Global status report on alcohol and health. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abdala N, Zhan W, Shaboltas AV, Skochilov RV, Kozlov AP, Krasnoselskikh TV. Efficacy of a brief hiv prevention counseling intervention among sti clinic patients in russia: A randomized controlled trial. AIDS and Behavior. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0311-1. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leon DA, Saburova L, Tomkins S, et al. Hazardous alcohol drinking and premature mortality in russia: A population based case-control study. Lancet. 2007;369:2001–2009. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60941-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Toussova O, Shcherbakova I, Volkova G, Niccolai L, Heimer R, Kozlov A. Potential bridges of heterosexual hiv transmission from drug users to the general population in st. Petersburg, russia: Is it easy to be a young female? J Urban Health. 2009;86 (Suppl 1):121–130. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9364-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abdala N, White E, Toussova OV, et al. Comparing sexual risks and patterns of alcohol and drug use between injection drug users (idus) and non-idus who report sexual partnerships with idus in st. Petersburg, russia BMC Public Health. 2010;10:676. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abdala N, Zhan W, Shaboltas AV, Skochilov RV, Kozlov AP, Krasnoselskikh TV. Correlates of abortions and condom use among high risk women attending an std clinic in st petersburg, russia. Reprod Health. 2011;8:28. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-8-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuntsche E, Rehm J, Gmel G. Characteristics of binge drinkers in europe. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59:113–127. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stolle M, Sack PM, Thomasius R. Binge drinking in childhood and adolescence: Epidemiology, consequences, and interventions. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2009;106:323–328. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2009.0323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pomerleau J, McKee M, Rose R, Haerpfer CW, Rotman D, Tumanov S. Drinking in the commonwealth of independent states--evidence from eight countries. Addiction. 2005;100:1647–1668. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.WHO. Alcohol use and sexual risk behaviour: A cross-cultural study in eight countries. Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse; Geneva: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dermen KH, Cooper ML, Agocha VB. Sex-related alcohol expectancies as moderators of the relationship between alcohol use and risky sex in adolescents. J Stud Alcohol. 1998;59:71–77. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hendershot CS, Stoner SA, George WH, Norris J. Alcohol use, expectancies, and sexual sensation seeking as correlates of hiv risk behavior in heterosexual young adults. Psychol Addict Behav. 2007;21:365–372. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.3.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhan W, Shaboltas AV, Skochilov RV, Krasnoselskikh TV, Abdala N. History of childhood abuse, sensation seeking, and intimate partner violence under/not under the influence of a substance: A cross-sectional study in russia. PLoS One. 2013;8:e68027. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068027. doi:68010.61371/journal.pone.0068027. Print 0062013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhan W, Krasnoselskikh TV, Golovanov S, Kozlov AP, Abdala N. Gap between consecutive sexual partnerships and sexually transmitted infections among sti clinic patients in st petersburg, russia. AIDS Behav. 2012;16:334–339. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9932-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhan W, Krasnoselskikh TV, Niccolai LM, Golovanov S, Kozlov AP, Abdala N. Concurrent sexual partnerships and sexually transmitted diseases in russia. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38:543–547. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318205e449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.George WH, Frone MR, Cooper ML, Russell M, Skinner JB, Windle M. A revised alcohol expectancy questionnaire: Factor structure confirmation, and invariance in a general population sample. J Stud Alcohol. 1995;56:177–185. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1995.56.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grant VV, Stewart SH, O’Connor RM, Blackwell E, Conrod PJ. Psychometric evaluation of the five-factor modified drinking motives questionnaire--revised in undergraduates. Addict Behav. 2007;32:2611–2632. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL. Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the ces-d (center for epidemiologic studies depression scale) Am J Prev Med. 1994;10:77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Lowe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The gad-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hu L-T, Bentler P. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods. 1998;3:424–453. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu CY. Evaluation of model fit indices for latent variable models with categorical and continuous outcomes: Unpublished dissertation. Los Angeles, CA: University of California Los Angeles; 2002. p. 168. http://www.statmodel.com/download/Yudisseatation.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus user’s guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Finkelhor D, Ormrod RK, Turner HA. Lifetime assessment of poly-victimization in a national sample of children and youth. Child Abuse Negl. 2009;33:403–411. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.09.012. doi:410.1016/j.chiabu.2008.1009.1012. Epub 2009 Jul 1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Turner HA, Finkelhor D, Ormrod R. Poly-victimization in a national sample of children and youth. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38:323–330. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.11.012. doi:310.1016/j.amepre.2009.1011.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dong M, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, et al. The interrelatedness of multiple forms of childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction. Child Abuse Negl. 2004;28:771–784. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Senn TE, Carey MP, Vanable PA. Childhood and adolescent sexual abuse and subsequent sexual risk behavior: Evidence from controlled studies, methodological critique, and suggestions for research. Clin Psychol Rev. 2008;28:711–735. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.10.002. Epub 2007 Nov 2028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Briere J. Treating adult survivors of severe childhood abuse and neglect: Further development of an integrative model. 2. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gore-Felton C, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Weinhardt LS, et al. The healthy living project: An individually tailored, multidimensional intervention for hiv-infected persons. AIDS Educ Prev. 2005;17:21–39. doi: 10.1521/aeap.17.2.21.58691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rotheram-Borus MJ, Swendeman D, Lee SJ, Li L, Amani B, Nartey M. Interventions for families affected by hiv. Transl Behav Med. 2011;1:313–326. doi: 10.1007/s13142-011-0043-1. doi:310.1007/s13142-13011-10043-13141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhan W, Hansen NB, Shaboltas AV, et al. Partner violence perpetration and victimization and hiv risk behaviors in st. Petersburg, russia Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2012;25:1–8. doi: 10.1002/jts.21658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bobrova N, West R, Malyutina D, Malyutina S, Bobak M. Gender differences in drinking practices in middle aged and older russians. Alcohol Alcohol. 2010;45:573–580. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agq069. doi:510.1093/alcalc/agq1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Minagawa Y. Gender differences in alcohol choice among russians: Evidence from a quantitative study. Eur Addict Res. 2013;19:82–88. doi: 10.1159/000342313. Epub 000342012 Nov 000342311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhan W, Shaboltas AV, Skochilov RV, Kozlov AP, Krasnoselskikh TV, Abdala N. Gender differences in the relationship between alcohol use and depressive symptoms in st. Petersburg, russia. J Addiction Research and Therapy. 2012;3 doi: 10.4172/2155-6105.1000124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bobak M, Room R, Pikhart H, et al. Contribution of drinking patterns to differences in rates of alcohol related problems between three urban populations. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004;58:238–242. doi: 10.1136/jech.2003.011825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grogan L. Alcoholism, tobacco, and drug use in the countries of central and eastern europe and the former soviet union. Subst Use Misuse. 2006;41:567–571. doi: 10.1080/10826080500521664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jukkala T, Makinen IH, Kislitsyna O, Ferlander S, Vagero D. Economic strain, social relations, gender, and binge drinking in moscow. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66:663–674. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Saburova L, Keenan K, Bobrova N, Leon DA, Elbourne D. Alcohol and fatal life trajectories in russia: Understanding narrative accounts of premature male death in the family. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:481. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Abdala N, Hansen NB, Toussova OV, Krasnoselskikh TV, Kozlov AP, Heimer R. Age at first alcoholic drink as predictor of current hiv sexual risk behaviors among a sample of injection drug users (idus) and non-idus who are sexual partners of idus, in st. Petersburg, russia AIDS Behav. 2012;16:1597–1604. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0013-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Leigh BC. Alcohol and condom use: A meta-analysis of event-level studies. Sex Transm Dis. 2002;29:476–482. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200208000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cooper ML. Alcohol use and risky sexual behavior among college students and youth: Evaluating the evidence. J Stud Alcohol Suppl. 2002:101–117. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Daigneault I, Hebert M, McDuff P. Men’s and women’s childhood sexual abuse and victimization in adult partner relationships: A study of risk factors. Child Abuse Negl. 2009;33:638–647. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.04.003. doi:610.1016/j.chiabu.2009.1004.1003. Epub 2009 Oct 1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]