Abstract

Juvenile onset amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a very rare form of motor neuron disease, with the first symptoms of motor neuron degeneration manifested before 25 years of age. Juvenile ALS is more frequently familial in nature than the adult-onset forms. Mutations in the alsin (ALS2), senataxin (SETX), and Spatacsin (SPG11) have been associated with familial ALS with juvenile onset and slowly progression. Here we reported two apparently sporadic ALS with juvenile onset and aggressive progression caused by mutations in the SOD1 and FUS gene. We also reviewed juvenile-onset ALS in publications. Our findings, together with other researches, confirms that both SOD1 and FUS mutations can lead to juvenile-onset malignant form of ALS and should be screened in ALS patients with an earlier age of onset, aggressive progression, even if there is no apparent family history.

Keywords

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS); juvenile onset; SOD1; FUS

Introduction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a syndrome characterized by progressive degeneration of neurons in the motor cortex, motor nuclei in the brainstem, and anterior horn cells of the spinal cord. Peak age at onset is 47-52 years for familial patients and 58-63 years for sporadic patients (1). About 50% of patients die within 30 months of symptom onset and about 20% of patients survive between 5 and 10 years after symptom onset (1). However, the clinical presentation, age of onset and progression of ALS varies considerably. Juvenile onset ALS is a very rare form of motor neuron disease, with the first symptoms of upper and lower motor neuron degeneration manifested before 25 years of age. Juvenile ALS is more frequently familial in nature than the adult-onset forms. Mutations in the ALS2, SETX, or SPG11 gene are known to cause familial ALS with juvenile onset and slow disease progression (2). A few sporadic cases of juvenile ALS with unusual and unexpected rapid progression have been reported (3-7). Here we reported two apparently sporadic ALS with juvenile onset and aggressive progression caused by mutations in the SOD1 and FUS gene.

Case reports

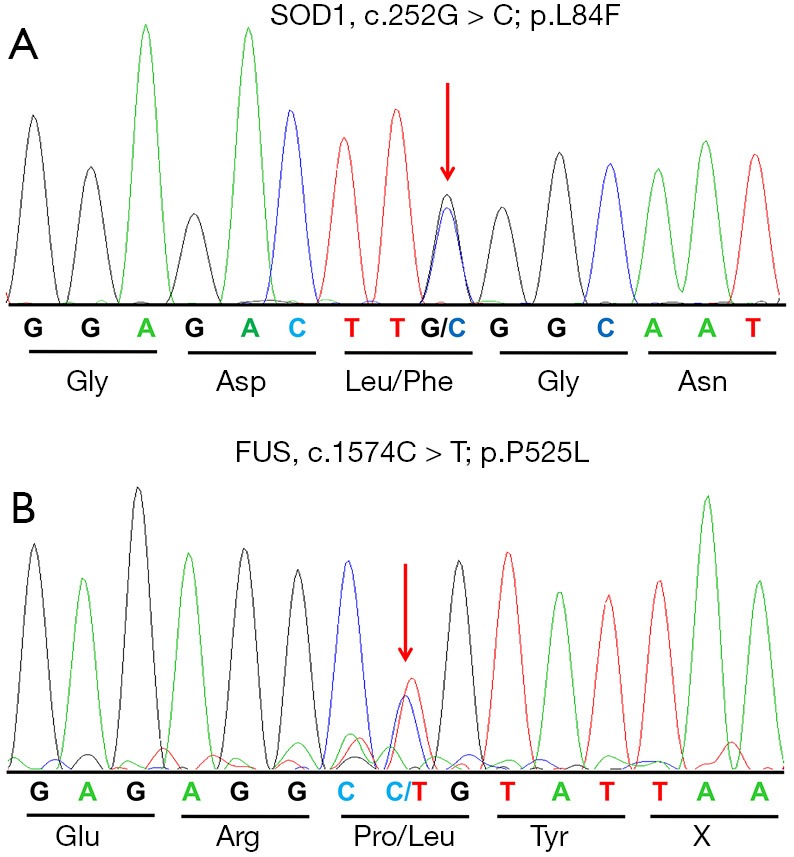

Patient 1 was a female manifested with weakness in her right foot at the age of 22. Over the subsequent 10 months, his weakness progressed quickly to involve proximal muscles of right lower limb, and then left leg. She required a walking stick, and could not walk more than 300 m. On examination, cranial nerves were intact. There was global muscle weakness and atrophy of the right leg, and mild muscle atrophy in the left leg. Deep tendon reflexes were brisk in upper limbs and decreased in lower limbs. The Babinski sign was present in the right side. Neurophysiological examination demonstrated chronic and active denervation in the lower limbs, as well as denervation potentials in the thoracic muscles. His parents did not present any symptoms at their 50s. An extensive inquiry showed no family history for any neuromuscular disorders. Genetic examination for the patient revealed the heterozygous c.252G > C (a p.L84F) mutation in exon 4 of the SOD1 gene (Figure 1A). The patient died 34 months after onset.

Figure 1.

Sequencing chromatograms of the p.L84F and p.P525L mutation. (A) Sequencing chromatograms of the p.L84F mutation in the SOD1 gene. The arrow shows the position of a G-to-C transversion at nucleotide 252 (c.252G > C) that leads to the replacement of leucine (Leu) by phenylalanine (Phe) at codon 84. (B) Sequencing chromatograms of the p.P525L mutation in the FUS gene. The arrow shows the position of a C-to-T transition at nucleotide 1574 (c.1574C > T) that leads to the replacement of proline (Pro) by leucine (Leu) at codon 525.

Patient 2 was a 13-year-old boy who presented with 4 months of weakness of right leg. One month after onset, weakness progressed to right arm. Weakness of his right limbs progressed so rapidly that he could hardly walk independently for 50 m, or left his arm. Physical examination revealed obvious atrophy of muscles of right arm and leg. Muscle strength of right limbs were grade 4. The deep-tendon reflexes were hyperactive in all limbs, with bilateral positive Babinski sign. Electromyography demonstrated widespread denervation in the lumbar, thoracic, cervical, and sternocleidomastoid muscles. Both his parents were healthy at their 50s. There was no history of neurologic diseases in her family. Gene test for the patient revealed the heterozygous c.1574C > T (p.P525L) mutation in the FUS gene (Figure 1B). The patient died 23 months after onset.

Discussion

Juvenile ALS are often familial ALS and caused by mutations in the ALS2, SETX, and SPG11 gene, which showed a very slowly progressive, nonfatal pattern (2). However, both juvenile ALS patients in this report had an aggressive progression, with no obvious familial history. Extensive literature review revealed 17 juvenile sporadic ALS patients of both Caucasian and Asian origin with known mutations, 1 had SETX mutation (8), 3 carried SOD1 mutations (3-5) and 13 had FUS mutations (6,7,9-14) (Table 1). Almost all these juvenile cases experienced aggressive progression, with a short disease duration ranging from 6 to 22 months except the SETX mutation carrier (Table 1). The FUS mutations harbored by juvenile sporadic ALS patients were frameshift mutations, nonsense mutations, and p.P525L mutation. P525L mutation, which have been consistently associated with a phenotype of earlier onset and severe course, was identified in 7 juvenile-onset sporadic ALS patients (Table 1) and 5 juvenile familial ALS patients (7). Truncating mutations in FUS has also been shown to cause a more aggressive ALS phenotype (15). Interesting, two deceased affected members in two p.L84F mutated pedigrees also presented with juvenile onset, rapid progression and short duration (16). These findings suggested that mutations in the SOD1 and FUS gene, particularly the p.P525L mutation, are associated with juvenile-onset ALS with rapid progression and short survival.

Table 1. Summary of juvenile-onset sporadic ALS patients with known mutations.

| Gene | Amino acid mutation | Gender | Ethnicity | Age of onset, years | Site of onset | Phenotype | Dementia | Disease duration (m) | De novo mutation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SETX | p.G16S | Male | USA | <6 | Lower limbs | UMN + LMN | NA | >123 (still walk) | NT | Hirano et al. 2011 (8) |

| SOD1 | p.G16S | Male | Japanese | 18 | Upper limbs | UMN + LMN | NA | 12* | NT | Kawamata et al. 1997 (3) |

| p.P66S | Male | Serbian | 21 | Upper limbs | UMN + LMN | NA | 22 (19*) | NT | Keckarević et al. 2012 (5) | |

| p.H80A | Male | Ireland | 24 | Lower limbs | LMN + bulbar | NA | 18 (9*) | De novo | Alexander et al. 2002 (4) | |

| p.L84F | Female | Chinese | 22 | Lower limbs | UMN + LMN | No | 34 | NT | This report | |

| FUS | p.G466VfsX14 | Female | USA | 16 | Bulbar | LMN + bulbar | No | 22 (15*) | De novo | DeJesus-Hernandez et al. 2010 (9) |

| p.G492EfsX527 | Male | Japanese | 17 | Upper limbs + bulbar | UMN + LMN + bulbar | Mental retardation | NA | NT | Yamashita et al. 2012 (10) | |

| p.R495X | Male | Chinese | 22 | Lower limbs | UMN + LMN | No | NA, rapid progression in 5 months after onset | NT | Zou et al. 2013 (7) | |

| p.G504Wfs*12 | Female | Chinese | 18 | Upper limbs | UMN + LMN + bulbar | Learning difficulties | NA, rapid progression in 7 months after onset | De novo | Zou et al. 2013 (7) | |

| p.R514S | Female | Japanese | 23 | Upper limbs | UMN + LMN | No | NA | NT | Yamashita et al. 2012 (10) | |

| p.Q519Ifs*9 | Male | UK | 18 | Upper limbs | UMN + LMN + bulbar | Learning difficulties | 6 | NT | Bäumer et al. 2010 (6) | |

| p.Q519X | Male | French-Canadian | 20 | Upper limbs | Not reported | NA | 12 | NT | Belzil et al. 2011 (11) | |

| p.P525L | Female | UK | 22 | Lower limbs | LMN | No | 10 | De novo | Bäumer et al. 2010 (6) | |

| Female | UK | 18 | Upper limbs | UMN + LMN | No | 11 | NT | Bäumer et al. 2010 (6) | ||

| NA | USA | 15 | NA | Not reported | NA | NA | NT | Brown et al. 2012 (12) | ||

| Female | Italian | 11 | Upper limbs | UMN + LMN | No | 14* | De novo | Conte et al. 2012 (13) | ||

| Female | USA | 12 | Upper limbs | LMN | Learning difficulties | 20 | De novo | Huang et al. 2010 (14) | ||

| Female | Chinese | 19 | Upper limbs | UMN + LMN + bulbar | No | NA, rapid progression in 7 months after onset | De novo | Zou et al. 2013 (7) | ||

| M | Chinese | 13 | Lower limbs | UMN + LMN | No | 23 | NT | This report |

Disease duration was defined as the time from onset of the disease to death/ tracheotomy. *, the time from onset to starting tracheotomy. FALS, familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; SALS, sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; UMN, upper motor neuron; LMN, lower motor neuron; NA, no data available; NT, not tested.

Low or incomplete penetrance has been reported in SOD1 and FUS mutations, making it difficult to distinguish between familial patients with reduced penetrance and true sporadic patients (17). However, among the reported juvenile ALS cases, 7 patients have been proved to carry the de novo mutations (Table 1), supporting that de novo mutations are responsible for at least a proportion of sporadic ALS patients. Although we could not perform genetic tests for the parents of both patients because of the paucity of DNA sample, they were still in good health at their 50s and had no family history of neurologic disease, suggesting that both patients were sporadic ALS.

Our findings, together with other researches, confirm that both SOD1 and FUS mutations can lead to juvenile-onset malignant form of ALS and should be screened in ALS patients with an earlier age of onset, aggressive progression, even if there is no apparent family history.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Kiernan MC, Vucic S, Cheah BC, et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet 2011;377:942-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Orban P, Devon RS, Hayden MR, et al. Chapter 15 Juvenile amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Handb Clin Neurol 2007;82:301-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kawamata J, Shimohama S, Takano S, et al. Novel G16S (GGC-AGC) mutation in the SOD-1 gene in a patient with apparently sporadic young-onset amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Hum Mutat 1997;9:356-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alexander MD, Traynor BJ, Miller N, et al. "True" sporadic ALS associated with a novel SOD-1 mutation. Ann Neurol 2002;52:680-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keckarević D, Stević Z, Keckarević-Marković M, et al. A novel P66S mutation in exon 3 of the SOD1 gene with early onset and rapid progression. Amyotroph Lateral Scler 2012;13:237-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bäumer D, Hilton D, Paine SM, et al. Juvenile ALS with basophilic inclusions is a FUS proteinopathy with FUS mutations. Neurology 2010;75:611-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zou ZY, Cui LY, Sun Q, et al. De novo FUS gene mutations are associated with juvenile-onset sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in China. Neurobiol Aging 2013;34:1312.e1-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Hirano M, Quinzii CM, Mitsumoto H, et al. Senataxin mutations and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler 2011;12:223-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeJesus-Hernandez M, Kocerha J, Finch N, et al. De novo truncating FUS gene mutation as a cause of sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Hum Mutat 2010;31:E1377-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamashita S, Mori A, Sakaguchi H, et al. Sporadic juvenile amyotrophic lateral sclerosis caused by mutant FUS/TLS: possible association of mental retardation with this mutation. J Neurol 2012;259:1039-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Belzil VV, Daoud H, St-Onge J, et al. Identification of novel FUS mutations in sporadic cases of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler 2011;12:113-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown JA, Min J, Staropoli JF, et al. SOD1, ANG, TARDBP and FUS mutations in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a United States clinical testing lab experience. Amyotroph Lateral Scler 2012;13:217-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Conte A, Lattante S, Zollino M, et al. P525L FUS mutation is consistently associated with a severe form of juvenile amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neuromuscul Disord 2012;22:73-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang EJ, Zhang J, Geser F, et al. Extensive FUS-immunoreactive pathology in juvenile amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with basophilic inclusions. Brain Pathol 2010;20:1069-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Waibel S, Neumann M, Rosenbohm A, et al. Truncating mutations in FUS/TLS give rise to a more aggressive ALS-phenotype than missense mutations: a clinico-genetic study in Germany. Eur J Neurol 2013;20:540-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ceroni M, Malaspina A, Poloni TE, et al. Clustering of ALS patients in central Italy due to the occurrence of the L84F SOD1 gene mutation. Neurology 1999;53:1064-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mackenzie IR, Rademakers R, Neumann M. TDP-43 and FUS in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia. Lancet Neurol 2010;9:995-1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]