Abstract

Epigenetic modification as an intrinsic fine-tune program cooperates with key transcription factors to regulate the cell fate determination. The histone acetylation participating in neural differentiation of pluripotent stem cells is expected but not well studied. Here, using acetylated histone H3 ChIP-sequencing (ChIP-seq), we demonstrate that the histone H3 acetylation level is gradually increased on the neural gene loci while decreased on the neural-inhibitory gene loci during mouse embryonic stem cell (mESC) neural differentiation. We further show that histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) is essential for neural commitment by targeting Nodal signaling. Thus, our study reveals a mechanism by which the epigenetic modification of histone acetylation/deacetylation interacts with extracellular signaling in mESC neural fate determination. Data were deposited in Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) datasets under reference number GSE66025.

Keywords: ChIP-sequence, Mouse embryonic stem cell, Histone H3 acetylation, Histone deacetylase 1, Neural fate commitment

| Specifications | |

|---|---|

| Organism/cell line/tissue | Time-course differentiated mESCs |

| Sex | Male |

| Sequencer or array type | Illumina Hiseq 2000 for acetylated histone H3 ChIP-seq, Illumina Genome Analyzer IIx for histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) ChIP-seq |

| Data format | Raw and analyzed |

| Experimental factors | Differentiated cells without treatment |

| Experimental features | ChIP-seq analysis of acetylated histone H3 and HDAC1 |

| Consent | N/A |

| Sample source location | Shanghai, China |

1. Direct link to deposited data

2. Experimental design, materials and methods

Cell culture and differentiation

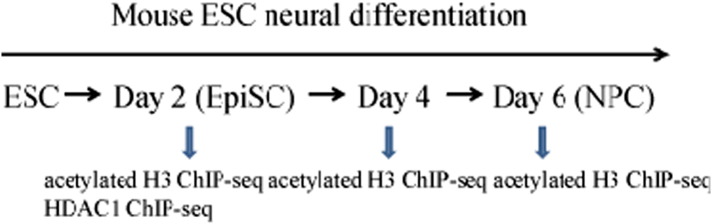

mESC line 46C, in which the expression of GFP was driven by the endogenous Sox1 gene (Sox1-GFP), was kindly provided by Dr. Austin Smith' lab. The cell line was maintained in feeder-free medium [1]. The monolayer neural differentiation was performed as previously described [2], [3]. Briefly, dissociated single mESCs were plated onto 0.1% gelatin coated dishes and cultured in N2B27 medium at the density of 0.5–1 × 104/cm2. N2B27 medium comprises 50% DMEM/F12 and 50% neurobasal medium (both from GIBCO) supplemented with 1 × N2, 1 × B27 (GIBCO), 0.1% bovine serum albumin fraction V (Roche), 1 mM glutamine (GIBCO), and 0.1 mM β-mercaptoethanol (GIBCO). On days 2, 4 and 6, cells were collected for H3 acetylation ChIP and HDAC1 ChIP-seq was performed on day 2 samples (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The histone acetylation ChIP-seq analysis during mouse ESC neural differentiation.

mESCs were differentiated into neural progenitors during 6 days. Cell samples were collected from day 2 to day 6. EpiSC: Epiblast stem cell; NPC: neural progenitor cell.

2.1. ChIP-seq

ChIP assays were performed as described previously [4]. Briefly, differentiated cells were cross-linked, lysed and sonicated to generate DNA fragments with an average size of 200 bp. Cell lysate was subjected to immunoprecipitation with antibodies against acetylated H3 or HDAC1 or directly used as ChIP input. 10–15 ng IP DNA and input DNA measured by Qubit Fluorometer (Invitrogen) were used to construct sequencing library by ChIP-Seq Sample Prep Kit (Illumina). Enriched DNA sequencing was performed on Hiseq 2000 or Genome Analyzer IIx (Illumina).

2.2. Data analysis

Reads were mapped to mm10 using bowtie (version 0.12.8). Only reads with less than two mismatches that uniquely mapped to the genome were used in subsequent analyses. Peaks were called using MACS (macs14 1.4.2) with default parameter [5]. Signal of merged peaks was calculated by reads from ChIP-seq located in that region subtracting that from Input, and then normalized by peak length and sequencing depth per 10 million. We defined genes bound by HDAC1 if peaks were identified by MACS at gene promoter region (upstream 2.5 kb and downstream 7.5 kb of TSS). For acetylated histone H3 ChIP-seq, read peaks from three neural differentiation time-points (days 2, 4 and 6) were further merged requiring adjacent distance less than 500 bp.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the “Strategic Priority Research Program” of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Grant No. XDA01010201, National Key Basic Research and Development Program of China (2014CB964804, 2015CB964500), and National Natural Science Foundation of China (91219303, 31430058).

References

- 1.Li F. Hepatoblast-like progenitor cells derived from embryonic stem cells can repopulate livers of mice. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:2158–2169. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.08.042. (e2158) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ying Q.L., Stavridis M., Griffiths D., Li M., Smith A. Conversion of embryonic stem cells into neuroectodermal precursors in adherent monoculture. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003;21:183–186. doi: 10.1038/nbt780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ying Q.L., Smith A.G. Defined conditions for neural commitment and differentiation. Methods Enzymol. 2003;365:327–341. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(03)65023-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jin Z. Different transcription factors regulate nestin gene expression during P19 cell neural differentiation and central nervous system development. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:8160–8173. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805632200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang Y. Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS) Genome Biol. 2008;9:R137. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-9-r137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]