Abstract

Introduction:

Spontaneous pneumocephalus without any pathological condition is very rare. We described a patient with spontaneous pneumocephalus probably arising from the relatively enlarged air-filling sphenoid sinus.

Case Presentation:

A 51-year-old woman admitted Imam Reza Hospital, Mashhad, Iran with a sudden onset of severe headache and nausea without any neurological deficit. Brain computed tomography (CT) scan was performed to role out any pathology in the brain. Brain CT revealed large ethmoidal and sphenoid sinuses and disseminated intracranial pneumocephalus. A Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) examination was performed to rule out meningitis. Further evaluation confirmed a small defect in the sphenoid sinus. She has no recurrent headache or other symptoms after about six-month follow-up.

Conclusions:

An extremely rare condition, a spontaneous intracranial pneumocephalus with skull base defect origin could be considered as a possible diagnosis in patients with sudden and severe headache. We can safely conclude that medical treatment and close follow-up is an effective mode of therapy in this patient.

Keywords: Pneumocephalus, Sphenoid Sinus, Spontaneous, Traumatic

1. Introduction

Pneumocephalus is defined as intracranial air. The majority of pneumocephalus cases are due to trauma. Non-traumatic spontaneous pneumocephalus is an uncommon condition, with common causes including barotraumas, valsalva maneuvers (1), adjacent air sinus infections, post-radiation necrosis (2) and neoplasm (3).

Pneumosinus dilatans (PSD) refers to an abnormally enlarged, air-filled paranasal sinus without radiologic evidence of localized bone destruction, hyperostosis, or mucous membrane thickening (4). We report a case of spontaneous pneumocephalus associated with PSD.

2. Case Presentation

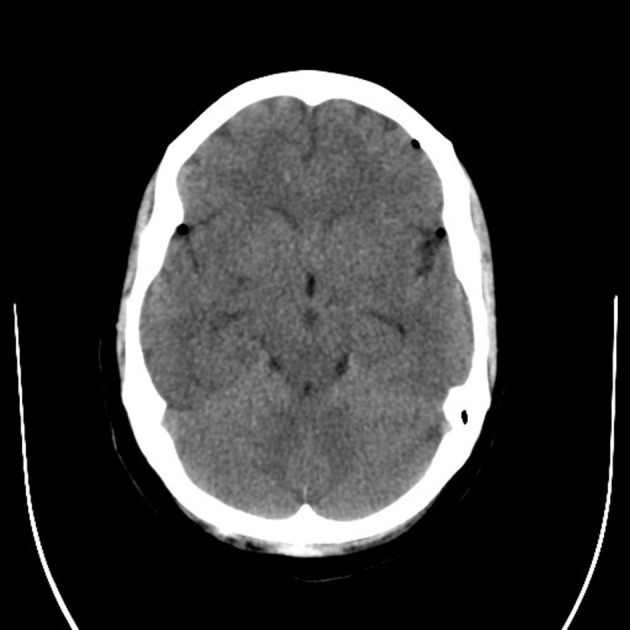

A 51 year-old Caucasian housewife was admitted Imam Reza Hospital, in Mashhad, northeast of Iran, in February 6th, 2014, complaining of severe headache and nausea. She started to develop sudden and severe headache following a spell of cough secondary to food sticking in her throat. She had no history of trauma, sinusitis or significant past medical history. Neurological and general examination revealed no deficit. To rule out intracranial pathology, a computed tomography (CT) was obtained and showed multiple small lesions with air density (-1000 Hounsfield units) in in sellar region, sylvian fissure and bifrontal of brain. Partial pneumatization could be seen in both mastoid and paranasal sinuses, which was indicative of pneumasinus dilatants (Figure 1). She was febrile; so, a lumbar puncture was performed, and the result of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis was shown to be within the normal range.

Figure 1. Computed Coronal Tomography.

Following admission, laxatives (magnesium hydroxide, 10 cc, three times daily) and oxygen (3 L/min) were given while she was bed-rested and advised against valsalva maneuvers. No antibiotic was given. Initial laboratory tests revealed no abnormality.

High resolution axial and coronal CT using a bone window showed the possible site of air leak and no pathologic lesion such as sinusitis or neoplasm (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2. Bony Window Skull Base Reformed Computed Tomography Scan.

Figure 3. Axial Computed Tomography Scan.

She was discharged ten days after the development of pneumocephalus. An additional CT scan of brain showed no air in the cranial cavity before discharge.

After six months of follow-up, she did not complain of any symptoms, and repeated CT scan revealed the absence of pneumocephalus.

3. Discussion

Pneumocephalus was described as intracranial air. The term “spontaneous” is applied to the condition where air accumulates intracranially, irrespective of any underlying condition namely tumors, infection, inflammation, surgery and trauma (5-9).

Pnematocele require two basic conditions to be formed. There should either exist an extracranial positive pressure source, or a persistent negative intracranial pressure gradient preceding the condition (8). The latter described as “inverted Soda bottle” or “Siphon effect” often occurs when shunt placement or dural leak results in diminished intracranial pressure, with CSF giving way to air (6, 8, 10, 11). The former though resembles a 'ball valve' in mechanism, whereby air is trapped inside the skull (6-10). By way of illustration, air can find its way all through the sphenoid sinus into the subperiostic space owing to a bone defect. As it accumulates due to the valve mechanism, any trauma, even a minor one such as valsalva maneuver, will be growingly likely to result in pneumatocele rupture into the intradural space.

This can occur even years following bone microfractures, steadily growing sinus walls defect (s) as well as dura mater lacerations. Sphenoid sinus inflammation supposedly plays a major role in this respect. Pneumocephalus chiefly presents with headache (11), along with other possible signs and symptoms such as CSF rhinorrhea, cranial nerve (1) palsies, hemiparesis, papiledema, CSF rhinorrhea, meningeal signs. Nevertheless, diagnosis is still elusive as there is no specific presentation in this respect (12). Table 1 shows the summary of cases with spontaneous pneumocephalus

Table 1. Summary of Cases With Spontaneous Pneumocephalus a.

| Author | Age | Sex | Precipitating Factor | Symptom | HP | Complications | Associated Condition | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Babl et al. (1) | 10 | F | Forceful Sneezing | Headache | None | CSF Rhinorrhea | Non | Surgery |

| Añorbe et al. (13) | 27 | M | Valsalva’s Maneuver | Auricular mass | Yes | None | None | Surgery |

| Schrijver et al (11) | 30 | F | Valsalva’s Maneuver | Asymptomatic | Yes | None | Bronchial asthma | Conservative |

| Richards et al. (14) | 17 | M | Nose Blowing | Auricular mass | Yes | Otalgia, Bloody Discharge | None | Surgery |

| 50 | F | Cough, Sneeze | Facial pain, Paresthesia | Yes | None | Allergic rhinitis, Nasal polyps | Surgery | |

| Scholsem et al. (4) | 74 | M | None | Headache | Yes | None | Meningioma | Surgery |

| Tucker et al. (8) | 19 | M | Nose Blowing | Headache | Yes | None | None | Surgery |

| Lee et al. (15) | 31 | M | None | Headache, nausea | Yes | None | None | Conservative |

| Kim et al. (16) | 62 | F | None | Headache | No | No | Meningitis | Conservative |

| Our Case | 51 | F | Cough | Headache, nausea | No | No | No | Conservative |

a Abbreviations: HP, Hyperpneumatization; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid.

Whether to opt for surgery or conservative therapy depends on etiology as well as severity (11). The former seems prior as long as there is recurrent CSF rhinorrhea and/or otorrhea owing to incomplete healing of the defect, or high ICP as a result of air accumulation, neoplasm with air ingress, gas-producing infection, intracerebral aerocele indicating brain adhesion to a fistulous tract.

We failed to identify the etiology in this very particular case, yet given the already existing PSD, dehiscence of the sphenoid wall sounds plausible. We considered the “ball valve” mechanism as the culprit since the patient had pneumosinus dilatans, having led to the condition following valsalva effect because of food sticking. Our choice was conservative therapy since there was no sign of infection.

There is paucity of cases in literature, reporting pneumocephalus owing to nontraumatic or spontaneous etiology. This case re-emphasized the importance of consideration of the diagnosis in a patient with unexplained sudden onset headache without any neurological deficit. We opt for a “wait and watch” policy through serial imaging if neither infection nor dural defect could be detected. Surgery should be taken into account in order to relieve intracranial pressure and fistulotomy in recurrent or infected cases. A clinical trial for diagnosis is needed and case reports or series like ours are not sufficient to establish the treatment protocol.

Footnotes

Authors’ Contributions:Elham Pishbin developed the original idea, revised the manuscript, and supervised the treatment. Babak Ganjeifar prepared the manuscript, collected the data, and finally revised the manuscript. Neda Azarfardian and Mohsen Salarian helped in follow-up of the patient and acquisition of data and abstracted the findings.

Financial Disclosure:This report has local institutional review board approval and the authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Babl FE, Arnett AM, Barnett E, Brancato JC, Kharasch SJ, Janecka IP. Atraumatic pneumocephalus: a case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1999;15(2):106–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ajalloveyan M, Doust B, Atlas MD, Fagan PA. Pneumocephalus after acoustic neuroma surgery. Otol Neurotol. 1998;19(6):824–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wakefield BT, Brophy BP. Spontaneous pneumocephalus. J Clin Neurosci. 1999;6(2):174–5. doi: 10.1016/s0967-5868(99)90091-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scholsem M, Collignon F, Deprez M, Martin D. Spontaneous pneumocephalus caused by the association of pneumosinus dilatans and meningioma: Case illustration. J Neurosurg. 2006;105(6):934. doi: 10.3171/jns.2006.105.6.934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krayenbuhl N, Alkadhi H, Jung HH, Yonekawa Y. Spontaneous otogenic intracerebral pneumocephalus: case report and review of the literature. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;262(2):135–8. doi: 10.1007/s00405-004-0754-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dowd GC, Molony TB, Voorhies RM. Spontaneous otogenic pneumocephalus: Case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 1998;89(6):1036–9. doi: 10.3171/jns.1998.89.6.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pennings RJ, Liauw L, Cremers CW. A spontaneous otogenic extradural pneumocephalus. Otol Neurotol. 2009;30(6):864. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e31818de597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tucker A, Miyake H, Tsuji M, Ukita T, Nishihara K, Ito S, et al. Spontaneous Epidural Pneumocephalus. Neurologia Medico-Chirurgica. 2008;48(10):474–8. doi: 10.2176/nmc.48.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao N, Wang DD, Huang X, Karri SK, Wu H, Zheng M. Spontaneous otogenic pneumocephalus presenting with occipital subcutaneous emphysema as primary symptom: could tension gas cause the destruction of cranial bones? Case report. J Neurosurg. 2011;115(4):679–83. doi: 10.3171/2011.6.JNS11104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mohammed el R, Profant M. Spontaneous otogenic pneumocephalus. Acta Otolaryngol. 2011;131(6):670–4. doi: 10.3109/00016489.2010.541941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schrijver HM, Berendse HW. Pneumocephalus by Valsalva's maneuver. Neurology. 2003;60(2):345–6. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000033802.04869.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abbati SG, Torino RR. Spontaneous intraparenchymal otogenic pneumocephalus: A case report and review of literature. Surg Neurol Int. 2012;3:32. doi: 10.4103/2152-7806.93861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Añorbe E, Aisa P, de Ormijana JS. Spontaneous pneumatocele and pneumocephalus associated with mastoid hyperpneumatization. European Radiol. 2000;36(3):158–60. doi: 10.1016/s0720-048x(00)00177-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richards SD, Saeed SR, Laitt R, Ramsden RT. Hypercellularity of the mastoid as a cause of spontaneous pneumocephalus. J Laryngol Otol. 2004;118(6):474–6. doi: 10.1258/002221504323219653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee JS, Park YS, Kwon JT, Suk JS. Spontaneous pneumocephalus associated with pneumosinus dilatans. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2010;47(5):395–8. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2010.47.5.395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim HS, Kim SW, Kim SH. Spontaneous Pneumocephalus Caused by Pneumococcal Meningitis. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2013;53(4):249–51. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2013.53.4.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]