Summary

The multifunctional-autoprocessing repeats-in-toxin (MARTXVv) toxin that harbors a varied repertoire of effector domains is the primary virulence factor of Vibrio vulnificus. Although ubiquitously present among Biotype I toxin variants, the Makes Caterpillars Floppy-like effector domain (MCFVv) is previously unstudied. Using transient expression and protein delivery, MCFVv and MCFAh from the Aeromonas hydrophila MARTXAh toxin are shown for the first time to induce cell rounding. Alanine mutagenesis across the C-terminal subdomain of MCFVv identified an RCD tripeptide motif shown to comprise a cysteine protease catalytic site essential for autoprocessing of MCFVv. The autoprocessing could be recapitulated in vitro by addition of host cell lysate to recombinant MCFVv, indicating induced autoprocessing by cellular factors. The RCD motif is also essential for cytopathicity, suggesting autoprocessing is essential first to activate the toxin and then to process a cellular target protein resulting in cell rounding. Sequence homology places MCFVv within the C58 cysteine protease family that includes the type III secretion effectors YopT from Yersinia spp. and AvrPphB from Pseudomonas syringae. However, the catalytic site RCD motif is unique compared to other C58 peptidases and is here proposed to represent a new subgroup of autopeptidase found within a number of putative large bacterial toxins.

Keywords: Vibrio vulnificus, MARTX, MCF, site-directed mutagenesis, autoprocessing

Introduction

Vibrio vulnificus, a Gram-negative halophillic bacterial pathogen, is the causative agent of fatal septicemia from food-borne infection and skin and soft tissue wound infections. The pathogenesis of the organism is attributed to a collection of virulence factors, including capsular polysaccharides, metalloproteases, hemolysin, and siderophores (Jones et al., 2009). In addition to these factors, the V. vulnificus multifunctional autoprocessing repeats-in-toxins (MARTXVv) toxin (also known as RtxA1) has been demonstrated to play a key role in pathogenesis. Infection studies in mice have demonstrated that disruption of the rtxA1 gene exerts a 2 to 3-log unit increase in LD50 both for intestinal and wound infection models, making MARTXVv toxin the most significant known virulence factor of V. vulnificus (Lee et al., 2007, Liu et al., 2007, Kim et al., 2008, Chung et al., 2010, Kwak et al., 2011, Lo et al., 2011, Jeong et al., 2012).

The MARTXVv toxin is a large single polypeptide toxin that is organized as a composite of structural and functional domains (Kwak et al., 2011, Roig et al., 2011, Satchell, 2011). The N-terminal and C-terminal regions are comprised predominantly of glycine rich repeats that form a pore in the eukaryotic plasma membrane and this pore has been shown to cause cellular necrosis (Kim et al. 2015). Between the repeat regions are found the effector domains and the autoprocessing cysteine protease domain (CPD) that are translocated into the target cells through the pore generated by the repeat regions (Kim et al. 2015). Based on studies of the V. cholerae MARTXVc toxin, these effector domains are thought to be released from the holotoxin by an autoprocessing event catalyzed by the inositol hexakisphosphate inducible CPD (Sheahan et al., 2007a, Prochazkova et al., 2008, Prochazkova et al., 2009, Shen et al., 2009, Egerer et al., 2010). These effector domains are then thought to cause the other toxic effects induced prior to the onset of cell lysis and including apoptosis, induction of reactive oxygen species, and actin depolymerization (Kim et al., 2008, Lee et al., 2008, Chung et al., 2010).

Recent comparative sequence analyses have revealed that different isolates of V. vulnificus all have similar repeat regions and the CPD, but carry distinct collections of effector domains and that these can be exchanged by homologous recombination (Kwak et al., 2011, Roig et al., 2011, Ziolo et al., 2014). Since the effector domains carry the cytopathic functions of this toxin (Kim et al. 2015) and these can vary among different isolates, it is important to discern the biological phenotypes induced by each of the effector domains individually to understand the function of each holotoxin variant.

Among the annotated MARTXVv variants encoded by the rtxA1 gene of various Biotype 1 V. vulnificus clinical isolates (Kwak et al., 2011, Roig et al., 2011), the only effector domain shared in all isolates is the effector domain designated as “Makes Caterpillars Floppy-like (MCFVv)”. It displays amino acid sequence similarity to a portion of the large secreted Mcf1 and Mcf2 toxins from the insect pathogen Photorhabdus luminescens (Daborn et al., 2002). The unusual name is derived from the observation that the injection of Mcf1 from Ph. luminescens or Photorhabdus temperata induces rapid loss of body turgor conferring a floppy phenotype in the Manduca sexta larvae (Daborn et al., 2002, Waterfield et al., 2003, Ullah et al., 2014).

In the present study, we sought to initiate studies on the MCFVv effector domain of the MARTXVv toxin. We herein provide the first report demonstrating that MCFVv is cytopathic to cells resulting in rounding of a variety of mammalian cell types. Using a combination of deletion analyses and alanine scanning mutagenesis, the MCFVv effector domain is proposed to have two functional regions; an essential N-terminal helix (NTH) harboring an autoprocessing site and a C-terminal peptidase with a unique Arg-Cys-Asp triad that is responsible for both autoprocessing of the effector domain and for cytopathicity. This tripeptide motif is found within other conserved putative cysteine proteases within large secreted bacterial proteins suggesting MCFVv is representative member of a new subfamily of the C58 peptidases.

Results

Ectopic expression of MCFVv-EGFP induces rounding of HeLa cells

For this study, the deduced primary amino acid sequence of the MARTXVv toxin from the clinical isolate CMCP6 was examined. This 5206 aa toxin carries five effector domains with MCFVv mapped to the fourth position (Fig. 1A). Since the processing sites between the effector domains of MARTXVv have not been mapped experimentally, boundaries of the MCFVv effector domain in strain CMCP6 were first predicted based on amino acid alignment with other MARTX toxins having an Mcf-like domain flanked by domains distinct from the arrangement in CMCP6 and by visual inspection of the CMCP6 protein sequence flanking the MCFVv aligned domains for consensus CPD-dependent cleavage sites (Shen et al., 2009). This analysis predicts that MCFVv in CMCP6 is 376 amino acids (aa 3204–3579) encoded by nucleotides 9610–10737 of the rtxA1 gene VV2_0479 (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1. Mcf homology domains in MARTX and other putative toxins.

A. Schematic representation of MARTX toxins from V. vulnificus and A. hydrophila detailing cysteine protease domain (CPD) and distinct arrangement of effector domains in these two toxins (DUF1, domain of unknown function in first position; RID, Rho Inactivation Domain; ABH, alpha-beta hyrdrolase; DUF5; domain of unknown function in the 5th position; ACD, actin crosslinking domain). Enlarged top diagram of the MCFVv effector domain shows the locations of features revealed in this study including the autoprocesing site, the N-terminal helix (NTH), and the C58 peptidase homology (striped boxes).

B. A C58 peptidase with conservation in the Photorhabdus Mcf toxins is found also in many other putative bacterial toxins of variable features as indicated, including the common toxin motif known as Mcf1-SHE, regions with homology to type III secretion effector HrmA (also known as HopA1), a membrane localization domain (MLD), glycosyl transferase (GTase) effector domain, and NCBI annotated conserved domain DUF3491. Many of these toxins also have a pore-forming domain similar to clostridial glucosylating toxins TcdA and TcdB (light striped boxes).

C. Alignment of all amino acid sequences of proteins in panels A and B revealed only two short regions (I and II) of strong sequence conservation, indicated in panels A and B by white boxes inside the C58 peptidase grey striped boxes. These regions were aligned using the ClustalW algorithm with sequence identity (dark grey) and similarity (light grey) indicated. Asterisks indicates point mutations generated in MCFVv that did not affect cell rounding, black daggars indicate essential residues, and grey daggar is partially required. Sequences used were all from National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) with accession numbers and references as follows: V. vulnificus CMCP6 MARTX toxin (Kim et al., 2011) (NP_762440.1); A. hydrophila 7966 MARTX toxin (Seshadri et al., 2006) (YP_855898), Ph. luminescens Mcf1 (Daborn et al., 2002) (AAM88787.1), Ph. luminescens Mcf2 (Waterfield et al., 2003) (AAR21118), Pseudomanas protegens FitD (Pechy-Tarr et al., 2008) (ABY91230), Providencia rettgeri YopT-type (WP_004260437, direct submission) Escherichia coli Toxin B (Hazen et al., 2013) (WP_024231151), Grimontia hollisae Toxin B (WP_005504930, Direct submission), Pseudomonas chlororaphis FitD (WP_009049649, direct submission), Yersina pestis YopT (Parkhill et al., 2001) (NP_395155), Pseudomonas syringae AvrPphB (Jenner et al., 1991) (also known as AvrPph3, AAA25727).

To investigate whether MCFVv is cytopathic to the cells, the DNA corresponding to MCFVv was cloned into pEGFP-N3 in fusion with egfp under the control of the CMV promoter. Eighteen hours after transfection, HeLa cells expressing MCFVv-EGFP, which migrated at an appropriate size of ~64 kDa on SDS-PAGE, were rounded as evidenced by loss of actin cytoskeleton structure. This was as opposed to the distinct and continuous actin stress fibers observed in cells expressing only EGFP (Fig. 2A and B). This cell rounding did not result in cell lysis since lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release during transfection was not significantly different between the cells expressing MCFVv-EGFP and EGFP (Fig. 2C). This experiment shows that MCFVv is a bona fide effector that induces a cytopathic effect in epithelial cells.

Fig. 2. Ectopic expression of MCFVv induces cell rounding.

A. Transient transfection of HeLa cells for 18 h with plasmids for expression of EGFP and MCFVv-EGFP (green) as indicated were stained with rhodamine phalloidin for F-actin (red) and DAPI for nucleus (blue). Percent cell rounding from 100 transfected cells from each of three independent transfections is noted in the inset.

B. Western blot using anti-EGFP or anti-actin antibody on transfected cell lysates.

C. Percent LDH release from transfected HeLa cells.

D. Bright field or cells stained as above (inset) intoxicated with either 72 nM of LFN or LFN-MCFVv in combination with 168 nM of PA for 24 h.

E. Coomassie-stained 12% SDS-PAGE gel showing the integrity of the LFN-MCFVv used for intoxication at two different concentrations as indicated.

F. Percent LDH release from the intoxicated HeLa cells showing that there is no appreciable lysis when cells when MCFVv is delivered directly.

Delivery of MCFVv to HeLa cells as a fusion to Bacillus anthracis LFN is also cytopathic

Previous studies with other toxin effectors have shown that they can function efficiently when fused with the N-terminus of B. anthracis lethal factor (LFN) and delivered to the cells by protective antigen (PA) (Wesche et al., 1998, Spyres et al., 2001, Sheahan et al., 2007b). To substantiate the cytopathic effect of MCFVv in a system that does not depend on protein overexpression in cells, the rtxA1 DNA corresponding to MCFVv was cloned in fusion with a portion of the B. anthracis lef gene to generate LFN fused to MCFVv. The LFN-MCFVv protein purified by Ni2+-affinity chromatography migrated at 70 kDa on an SDS-polyacrylamide gel as expected (Fig. 2E). When the LFN-MCFVv fusion protein was delivered into HeLa cells using PA, cells showed distinct morphological changes including cytosolic shrinkage and loss of a structured actin cytoskeleton. By comparison, the cells intoxicated with LFN alone in combination with PA appeared normal (Fig. 2D). Similar to the transfection system, the cell rounding induced by LFN-MCFVv was not accompanied by cell lysis (Fig. 2F). These data corroborated the transfection data and confirmed that MCFVv is a cytopathic effector domain, even when the domain is not ectopically overexpressed.

Cell rounding by MCFVv is dependent on a novel arginine-cysteine-aspartate triad

Sequence homology and structural alignments identified that the C-terminal portion of MCFVv is a putative C58 peptidase (Fig. 1B), a cysteine protease family that includes the type III secretion effectors YopT from Yersinia spp. and AvrPphB from Pseudomonas syringae (Puri et al., 1997, Shao et al., 2002, Tampakaki et al., 2002, Shao et al., 2003, Lu et al., 2013). Members of the peptidase C58 family have an active site comprised of Cys-His-Asp (Rawlings et al., 2014). Based on the extensive sequence alignment of MCFVv, we identified two specific regions (region I and region II) within the peptidase that showed prominent conservation of amino acids (Fig. 1C). Based on these amino acid alignments, Cys-3351, Asp-3482 and His-3463 in regions I and II were predicted to be essential active site residues. Indeed, substitution of Cys-3351 to Ala completely abrogated the cell rounding phenotype (Fig. 3A). However, mutation of Asp-3482 and His-3463 to Ala did not abrogate cell rounding with 83–93% cells still rounded (Fig. 3A and C) indicating that these are unlikely catalytic residues as predicted.

Fig. 3. MCFVv mediated cell rounding is dependent on an RCD triad.

A and B. Percent cell rounding from 100 transfected (A) or intoxicated (B) HeLa cells from each of three independent reactions was plotted. Data shown are mean ± standard deviation with mean labeled above the bar.

C. Western blot using anti-EGFP antibody on indicated cell lysates.

D. Migration of LFN-tagged mutant proteins used for intoxication on a Coomassie-stained 12% SDS-PAGE gel.

Therefore, to find additional residues that could impact the cell rounding activity of this putative peptidase, alanine mutagenesis was conducted for 14 other most conserved residues throughout regions I and II, including two glutamate, one glutamine, four aspartate, one phenylalanine, one histidine, two tyrosine, one arginine, one cysteine and one asparagine (Fig. 1C). Out of these, Ala replacement of Arg-3350 and Asp-3352 completely abrogated cell rounding (Fig. 3A). The EGFP fusion proteins were expressed as full-length proteins, indicating that the lack of cell rounding was not due to protein degradation (Fig. 3C).

Further, upon examining the amino acid alignment of the entire MCFVv sequence with MCFs from different Vibrio spp., A. hydrophila and Xenorhabdus nematophila, other conserved amino acid patches were identified apart from regions I and II (Fig. S1). Thus, alanine mutagenesis was conducted on another 25 conserved residues throughout the full-length MCFVv (Fig. S1). This screen revealed an intermediate phenotype when His-3258 and Asp-3345 were mutated to Ala, wherein the cells were not completely round and shrunken but retained some cytoskeletal stress fibers with ~30–60% cells rounded (Fig. 3A and C).

To verify the above results, each of the five mutations that affected cell rounding completely or partially were generated as LFN-tagged proteins to test for protein function in a system where the proteins are not overexpressed. The modified fusion proteins were purified (Fig. 3D) and found to be structurally intact by CD spectroscopy (data not shown). Similar to the transfection results, the proteins modified to have mutations in Arg-3350, Cys-3351, or Asp-3352 were unable to confer cell rounding (Fig. 3B), while those with mutations in His-3258 and Asp-3345 showed a partial defect.

Asp-3352 can be exchanged also to tyrosine

The above results confirmed that the cell rounding mediated by MCFVv is dependent on a tandemly organized triad composed of an Arg-Cys-Asp. The aa alignment indicates that this triad is strongly conserved for Arg-3350 and Cys-3351 (Fig. 1C). To further determine the essentiality of these residues, Arg-3350 and Asp-3352 were exchanged for Lys or Glu and Cys-3351 was exchanged for a Ser. The plasmids expressing either EGFP alone, MCFVv-EGFP and other fusion proteins were transfected in HeLa cells and the cell rounding was scored. The substitution of Arg-3350 to Lys or Glu completely abolished cell rounding (Fig. 4A and B). However, cells expressing MCFVv-EGFP with Cys-3351 replaced with Ser did result in cell rounding in 60% of the cells indicating that there is flexibility in this key residue to be exchanged for Ser (Fig. 4A and B), although the alignment shows only a Cys at this position suggesting strong selection for Cys over Ser.

Fig. 4. Asp-3352 can tolerate a tyrosine residue while other residues in the tripeptide motif are strictly conserved.

A. Percent cell rounding from 100 transfected cells from each of three independent transfections was plotted. Data shown are mean ± standard deviation with mean labeled above the bar.

B. Western blot using anti-EGFP and anti-actin antibodies on indicated cell lysates to demonstrate protein expression. Arrows on left blot indicate bands in same order as labeled on right blot.

Further mutagenesis indicated that the substitution of Asp-3352 to either Glu or Lys abrogated cell rounding suggesting Asp at this position is absolutely required (Fig. 4A and B). However, the alignment of proteins with Mcf-like domains suggested that a Tyr substitution at this position could be tolerated (Fig. 1C). Indeed, cells transfected with a plasmid expressing MCFVv-EGFP with Asp-3352 replaced with Tyr was still able to induce cell rounding in ~70% of cells (Fig. 4A and B) Thus, proteins in this family have an RCD/Y motif that is important for induction of cytopathicity.

MCFVv confers similar cell rounding phenotype in different eukaryotic cells

To expand beyond HeLa cells, the effect of MCFVv expression in different cell lines and different eukaryotic hosts was also examined. A similar cell rounding phenotype was observed upon MCFVv-EGFP expression in CHO-K1 Chinese hamster ovary cells, COS-7 African Green monkey fibroblast, HEK293 kidney cells, and HEp-2 laryngeal carcinoma epithelial cells (Table 1). In all cases, it was found that alanine substitution for Cys-3351 abrogated the host cell rounding. However, when MCFVv was expressed in S. cerevisiae, it did not inhibit its growth (Table 1). Thus, MCFVv is capable of inducing cytopathicity in a broad range of mammalian cells, but its effect does not extend to lower eukaryotic cells.

Table 1.

Cytotoxicity of MCFVv in different cell lines

| Cytotoxicitya,b | ||

|---|---|---|

| MCFVv | MCFC3351A | |

| HeLa Human cervical carcinomaa | + | − |

| COS7 African green monkey fibroblasta | + | − |

| HEp-2 Human laryngeal epitheliala | + | − |

| CHO-K1Chinese hamster ovarian epitheliala | + | − |

| HEK293 Human embryonic kidney cells | + | − |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiaeb | − | − |

Cells were transfected to express either MCFVv-EGFP or MCFC3351A-EGFP. The morphology of EGFP positive cells was monitored 18 h post-transfection for round (+) vs. normal (−). The expression of EGFP fusion protein was confirmed by western blotting using anti-EGFP monoclonal antibody.

S. cerevisiae was transformed to express either MCFVv or MCFC3351A and the growth was assessed on SC-Ura agar plates supplemented with raffinose and galactose. The expression of recombinant proteins in the heterologous host was also confirmed using anti-His6 monoclonal and anti-MCFVv polyclonal antibodies, which revealed absence of autoprocessing of MCFVv in yeast.

Ectopic expression of MCFAh from Aeromonas hydrophila induces cell rounding dependent on the conserved cysteine

The sequence alignment shows several MARTX toxins also carry domains with homology to MCFVv. Among these, the MCFAh effector domain from A. hydrophila is quite divergent with only 57% amino acid similarity (Fig. S1). Nonetheless, HeLa cells expressing MCFAh-EGFP showed rounding (Fig. 5A–C). The MCFAh also harbors an RCD peptide triad that maps to residues aa 2842–2844 of the deduced protein of the holotoxin. Similar to the results with MCFVv, modification of Cys-2843 to Ala in MCFAh abrogated cell rounding (Fig. 5A–C), confirming the cytopathicity may be generally shared among MARTX toxins harboring this domain.

Fig. 5. MCF from A. hydrophila and from P. luminescens and P. asymbiotica show contrasting phenotypes.

A and D. Confocal fluorescence microscopy of HeLa (A) or HEK293T (D) cells post-transfection of the plasmids as indicated. Bar=10 µm.

B and E. Western blot detection of EGFP and EGFP-fusion proteins. For Western blot, actin was used as loading control.

C and F. Percent cell rounding from 100 transfected cells from each of three independent transfections was plotted. Data shown are mean ± standard deviation.

Aligned domains from Photorhabdus spp. MCF toxins are not cytopathic

The designation of the MARTX toxin effector domain as MCFVv is derived from the sequence conservation with an internal domain of the Photorhabdus spp. Mcf1 and Mcf2 toxins (Fig. 1C), although the Mcf1 aligned domains to MCFVv from Ph. luminescens and Photorhabdus asymbiotica are only 26 and 25% similar, respectively. The sequences of the aligned domains from Ph. luminescens Mcf1 when fused to egfp did not express when transfected in HeLa or HEK293T cells and no EGFP-positive cells were observed. Analysis of the sequences of the aligned portions of Mcf1 from Ph. luminescens and Ph. asymbiotica for codon adaptability index (CAI: http://bioinformatics.biologicscorp.com/RareCodonAnalyzer) revealed a CAI of 0.7 for MCFVv in contrast to a CAI=0 for Mcf1Pl and Mcf1Pas. To circumvent this problem, eukaryotic codon optimized sequences corresponding to the aligned regions of Mcf1Pl and Mcf1Pas were synthesized commercially and transfected in HEK293T cells as egfp fusion proteins. Although Mcf1Pl-EGFP and Mcf1Pas-EGFP now showed fairly good expression, neither was able to cause cell rounding (Fig. 5D–F). Thus, while MCFVv initially derived its name from its limited homology to the Mcf toxins, they may not share similar function in vivo. However, it is notable that these domains have been taken out of context from very different large protein toxins, and thus we cannot exclude that the aligned domains of Mcf1Pl and Mcf1Pas have similar function but require additional portions of the holotoxin to be functionally active.

MCFVv displays an auto-processing activity dependent on its active site residues

To study in detail the function of MCFVv by ectopic expression excluding the bulky EGFP, we cloned MCFVv and its catalytic mutants to express a 3×-FLAG tag at the N-terminus and HA tag at the C-terminus (Fig. 6A). Surprisingly, the FLAG-MCFVv-HA wild-type protein when expressed in HEK293T cells was found to migrate at 37 kDa, which is ≈10 kDa faster than its expected size (49 kDa). However, the mutants migrated at the anticipated molecular weight (Fig. 6A). This result suggested an in vivo cleavage event that was abolished when the active site residues, Arg-3350, Cys-3351 and Asp-3352 were replaced with Ala, pointing towards autoproteolysis. This cleavage apparently occurred at the N-terminus, since no signal was obtained for the FLAG epitope in wild-type MCFVv (Fig. 6A). By contrast, similar cleavage of MCFVv expressed in S. cerevisiae with an N-terminal 6×–His tag was not observed, perhaps accounting the lack of cytopathicity of this effector for yeast (Table 1).

Fig. 6. MCFVv autoprocesses both in vivo and in vitro.

A. Schematic representation of the FLAG and HA-tagged protein generated by transient expression in HEK293T cells. HEK293T cell lysates from cells transfected to express indicated protein were probed with anti-HA and anti-FLAG antibodies with actin as a loading control.

B. Schematic representation of 6×-His tagged recombinant MCFVv with an HA tag (rMCFVv-HA). 20 µg purified protein was incubated in the presence or absence of 30 µg HEK293T cell lysate (CL) and both unprocessed and cleaved protein (cMCFVv-HA) were detected by Western blotting using anti-HA antibody.

C. Schematic representation of the 6×-His tagged recombinant MCFVv (rMCFVv) used in panels C-G. Purified protein was incubated in the presence or absence of HEK293T cell lysate (CL) and reactions were resolved on 18% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and proteins visualized with coomassue blue. Cleaved protein is marked with small arrow and letter c. When indicated, rMCFVv was heat-treated prior to addition of CL (hkMCFVv)

D–G. In vitro processing as in panel C except using (D) rMCFVv protien with amino acid changes as indicated, (E) rMCFVv protien pre-treated for 30 min with 1 mM NEM when indicated, (F) rMCFVv protein mixed with heat-treated (hk) CL when indicated, and (G) rMCFVv protein mixed with CL pre-treated with trypsin (ty) or proteinase K (pk) followed by boiling when indicated.

To substantiate these data in vitro, recombinant 6×-His tagged MCFVv (rMCFVv) was purified from E. coli both with and without a C-terminal HA tag (Fig. 6B,C). These purified proteins migrated at the expected molecular weight indicating that the proteins purified from E. coli were not processed. However, when either rMCFVv-HA or rMCFVv was incubated with HEK293T cytosolic lysate (CL), the proteins were processed (Fig. 6B and C). An E. coli lysate did not induce processing of rMCFVv accounting for successful purification of the full-length protein from E. coli (Fig. S2).

N-terminal processing was not induced by CL when rMCFVv was modified to carry mutations in the RCD triad (Fig. 6D) and these mutations had no detrimental effect on the structure or stability as rMCFVv mutant proteins showed a similar half-maximal melting temperature of ≈47–49°C as wild-type rMCFVv. This result indicates that the lysate stimulates autoprocessing rather than providing a cellular protease. Further evidence of autoprocessing is that rMCFVv pre-treated with cysteine protease inhibitor N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) did not undergo CL-induced cleavage (Fig. 6E). The inducing component in the lysate is likely to be a heat-stable protein as boiling the CL did not inhibit its ability to induce MCFVv processing (Fig. 6F) although treatment with proteinase K and trypsin did inhibit the activity (Fig. 6G).

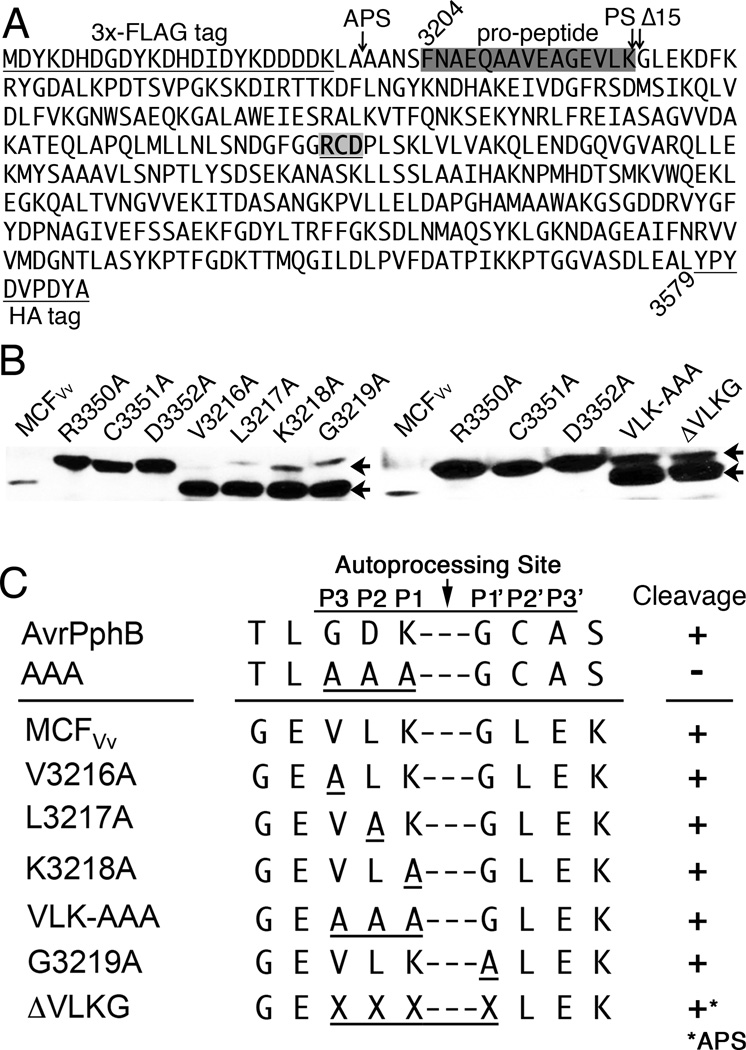

MCFVv autoprocesses between the conserved lysine-glycine pair

To identify the proteolytic cleavage site (PS), the band corresponding to the cleaved rMCFVv (cMCFVv) was excised and subjected to N-terminal sequencing. The amino acid sequence obtained from the Edman reaction cycles generated the sequence GLEKD, indicating that the cleavage occurs between the Lys-3218 and Gly-3219 (3218K-G3219) (Fig. 7A). It is noteworthy that this Lys-Gly processing site is strongly conserved amongst all the aligned MCF domains from other MARTX toxins (Fig. S1). Despite the sequence conservation at this site, single or multiple amino acid substitutions of residues in the P1, P2, P3, or P1’ positions had no impact on the autoprocessing of the FLAG-MCFVv-HA protein when expressed in HEK293T cells (Fig. 7B). Further when these four residues were deleted, MCFVv was still processed, albeit with lesser efficiency and at an alternative processing site (APS) present in the linker region between the FLAG-tag and the protein (Fig. 7B). Thus, the recognition of the cleavage site is not defined by sequence, but is likely structurally based and dictated by residues throughout the core structure of the protease.

Fig. 7. MCFVv processing of N-terminus is not sequence-specific.

A. Protein sequence of MCFVv (aa 3204–3579) is shown with 3×FLAG and HA tags underlined. The pro-domain (boxed dark gray), the processing site (PS) between Lys-3218 and Gly-3219, the alternate processing site (APS) for ΔVLKG mutation, and position of Δ15 deletion for Fig. 8 are indicated with arrows. The RCD catalytic motif is bold and underlined.

B. HEK293T cell lysates from cells transfected as in Fig. 6A to express indicated protein were probed with anti-HA antibody to detect both full-length (upper arrow) and cleaved MCFVv protein (lower arrow).

C. Details of sequence of the various mutants in panel B with (+) indicating processing and (−) indicating failure to process. Data for AvrPphB is taken from Dowen et. al, 2009.

The processed form of the MCFVv is sufficient for cytopathicity

Next, we sought to delineate the minimal active region within the MCFVv required for cell rounding. Cells expressing EGFP from the vector appeared normal with distinct stress fibers while cells expressing the full-length MCFVv-EGFP, but not MCFVv–EGFP with a C3351A mutation, lost their cytoskeletal structure, were rounded as expected (Fig. 8). By contrast, neither a Δ188 deletion that extended past the RCD active site nor a Δ138 deletion that eliminates the N-terminal subdomain of the protein rounded cells (Fig. 8A and B), despite detectable expression of the EGFP fusion proteins at the expected electrophoretic mobility (Fig. 8C). These results indicate that the cysteine protease subdomain is not sufficient for cytopathicity.

Fig. 8. Ectopic expression of cleaved variant of MCFVv induces cell rounding.

A. Schematic representation of the deletion variants of MCFVv and its catalytic mutants generated in fusion with EGFP; the small grey inverted triangle represents the processing site. Dashed lines indicate sequences deleted. Percent cell rounding for 100 transfected cells as done in panel B is represented as mean ± standard deviation.

B. Confocal fluorescence microscopy images of HeLa cells transfected as indicated with inset for last panel magnified to highlight the punctae like structures indicative of subcellular localization. Figure is a composite of representative images from multiple experiments conducted over time as new deletions were tested, but all experiments were conducted with appropriate positive and negative controls. Bars = 10 µm.

C. Western blot detection of EGFP and EGFP-fusion proteins in transiently transfected HeLa cells as indicated. Actin was used as loading control in Western blot.

To better define the contribution of the N-terminal 138 aa of MCFVv, a deletion to remove the first 15 aa to mimic the natural cleavage event exposing Gly-3219 was generated (Fig. 7A and 8A). This Δ15 deletion was cytopathic similar to the full-length MCFVv-EGFP, with detectable expression of the fusion proteins at the expected sizes (Fig. 8). This indicates that the first 15 aa of MCFVv are dispensable for cytopathicity.

The processing site is found within a putative N-terminal helix (NTH) that extends 17 aa past the processing site. Deleting the entire NTH (Δ32) eliminated cell rounding despite good expression of the protein. To further dissect a possible role of this portion of the NTH in cell rounding, the mcfVv-egfp transfection plasmid was systematically modified by site-directed mutagenesis to substitute a codon for alanine in place of 14 codons in the NTH downstream from the processing site (Fig. S1). However, none of the mutations abrogated or even partially attenuated the rounding phenotype in HeLa cells, despite all the modified fusion proteins being expressed well (data not shown). These data indicate that the first 17 aa of the processed protein are essential for toxicity, but none of the specific residues are independently required, suggesting a structural role in the processed protein. Overall, the deletion analysis shows that the naturally autoprocessed form of MCFVv is the minimal portion essential for cell rounding, suggesting autoprocessing and cytopathicity are linked processes.

Cys-3351 is important in cytopathicity independent of autoprocessing

The association of autoprocessing and cytopathicity raised the question of whether the RCD catalytic triad also participates in subsequent downstream processes such as processing a cellular target. To answer this question, Cys-3351 was modified to Ala in the mcfVvΔ15 that mimics the autoprocessed protein (Fig. 8A). In contrast to cell rounding evident in cells expressing MCFVvΔ15-EGFP, cells expressing this protein with a substitution of Cys-3351 to Ala failed to induce cell rounding despite efficient expression (Fig. 8C and 8D). Further, cells expressing the mutant form of the EGFP fusion protein now appear to localize as distinct punctae distributed throughout the cytosol of HeLa cells, suggesting the protein now binds an intracellular vacuolar target but does not induce cytopathicity. This relocalization to punctae depended upon removal of the N-terminus as the C3351A mutation in the full-length protein, which does not autoprocess, was distributed throughout the cytoplasm (Fig. 8B). Overall, these results indicate that Cys-3351 not only facilitates autocleavage of the MCFVv effector domain, but also is crucial for downstream induction of cytopathicity and possibly appropriate cellular localization.

Discussion

MARTX toxins are composite toxins consisting of conserved regions thought to be necessary for transfer and delivery of an assemblage of effector domains that mediate cellular cytotoxic and cytopathic effects. Among the six annotated effector domains found in MARTX toxins of the clinically important V. vulnificus Biotype 1 clade C (Jones et al., 2009), only one effector domain is universally present: MCFVv. This domain is likely extremely important also for Biotype 2 strains that infect fish and eels, where it is nearly precisely duplicated with only 2 amino differences between two effector domains in the same protein (Kwak et al., 2011, Roig et al., 2011).

Bioinformatic annotation of MARTX toxins revealed this domain is notable for its conservation within a small region of large Mcf1 and Mcf2 insecticidal toxins of Photorhabdus spp. (Waterfield et al., 2003). The Mcf1 toxin from Ph. luminescens is known to mediate its cytotoxicity through two domains: an N-terminal BH3-like motif and a translocation domain similar to those found in the clostridial glucosylating toxins TcdA and TcdB (Fig. 1B) (Dowling et al., 2004, Dowling et al., 2007). Large-scale genomic analyses have also recognized a common toxin motif known as MCF1-SHE present in Mcf1 (Zhang et al., 2012). However, none of these previously identified domains informed about the region that aligned with V. vulnificus effector domain (Waterfield et al., 2003) and thus we initiated a de novo study of a protein of unknown function.

MCFVv was here shown for the first time to induce a cytopathic effect both when ectopically expressed and when delivered to cells in fusion with LFN, resulting in a pronounced loss of cytoskeletal structure of epithelial and other cell types. However, intoxication with MCFVv displayed a much weaker and less pronounced visual phenotype compared to the robust cell rounding observed when toxin was in vivo expressed in transfection system (Fig. 2). This could possibly be attributed to the differences in the in situ protein amounts expressed or delivered by two different systems. Other possibilities may include a compromised stability of the delivered LFN-MCFVv protein leading to a shorter half-life or masking of a portion of MCFVv required for subcellular localization due to the N-terminal LFN tag. The MCFAh domain from the A. hydrophila MARTX toxin was similarly shown to induce cell rounding demonstrating this function is conserved across MARTX toxins of different species.

A targeted site-directed mutagenesis strategy identified an unprecedented peptide triad composed of Arg-3350, Cys-3351, and Asp-3352 as essential for cytopathicity. Although compromised, the partial cell rounding observed when Cys-3351 was substituted for Ser in the active site could be due to the lower strength and effectiveness of oxygen compared to sulfur to function as a nucleophile. However, 100% conservation of this residue among different aligned protein homologues indicates that Cys is the preferred catalytic nucleophile at this position (Fig. 1C). The neighboring Asp substitution to Tyr was also well tolerated. This RCD/Y motif is not present in the representative C58 peptidase subgroup A enzyme YopT or the subgroup B protein AvrPphB (Rawlings et al., 2014) Attempts to utilize structural modeling against the crystal structure of AvrPphB (Zhu et al., 2004) to identify additional putative catalytic residues failed as the Asp and His residues conserved with known catalytic residues from AvrPphB and YopT could be modified to Ala in MCFVv (His-3463 and Asp-3482), with no adverse effect on in vivo function. Indeed, an Asp and His located to the N-terminal side of the RCD/Y motif only partially impacted rounding (of which the His is not conserved in AvrPphB). These two residues may simply contribute to formation or stability of the putative peptidase via a tertiary fold unique to MCFVv that places them in proximity to a catalytic site formed by the RCD/Y motif. This analysis suggests that MCFVv may be a novel protein within the C58 peptidase family, potentially a representative member of a new subgroup. Enzymes in this new subgroup would have the RCD/Y motif and include MCF-like domains from MARTX toxins, Mcf1 and Mcf2 insecticidal toxins, and, as shown in Fig. 1B, the central regions of other putative large secreted bacterial toxins.

The function of this RCD/Y peptidase domain was not initially recognized as the first strategy to express MCFVv fused to EGFP with no N-terminal extension resulted in a large protein with no apparent mobility shift in western blots conducted to detect EGFP-fusion proteins. However, when a different expression construct was generated with a longer N-terminal extension and highly charged 3×FLAG-tag and only a short HA tag in place of EGFP, a mobility shift of ~10 kDa was readily evident for the wild-type protein compared to those with mutations in the RCD motif. This identified the function of this portion of the MCFVv domain as a cysteine autopeptidase. The cleavage could be recapitulated in vitro facilitating identification of the site of cleavage as between Lys-3218 and Gly-3219. Interestingly, induction of autoprocessing in vitro required the RCD tripeptide motif and addition of a cell cytoplasm protein fraction sensitive to protease but not heat. These data point to autoproteolysis induced by a small heat stable protein. It is possible that this protein is not conserved in yeast, accounting for both lack of processing of MCFVv and cytopathicity when expressed in yeast. Overall, these data indicate that in the context of the MARTXVv holotoxin, MCFVv is processed twice. First, by inositol-hexakisphosphate induced processing by CPD and then by a second induced autoprocessing event to remove its own N-terminus.

Strikingly, the conserved RCD/Y peptidase region from Ph. luminescens or Ph. asymbiotica Mcf1 was not able to round the HeLa cells. In fact, the N-terminal region from aa 1–1280 of Mcf1 previously linked to cytotoxicity excluded entirely the RCD/Y peptidase domain found at aa 1301–1519 (Dowling et al., 2004). These data point to additional requirements for toxicity beyond the RCD/Y peptidase domain in Mcf1. Similarly, a small deletion removing just 32 aa from full-length MCFVv, an equivalent to trimming the processed protein by only 15 aa, was sufficient to abrogate cell rounding activity of MCFVv indicating that here too, the C-terminal RCD/Y peptidase subdomain is not sufficient for cytopathicity.

One model that we postulated was that the two-step autoprocessing of MCFVv from the MARTXVv holotoxin is intended to generate just the short peptide between the CPD and MCFVv autoprocessing sites consisting of amino acids 3204–3218. This model is not supported since the first 15 residues of the MCFVv domain are poorly conserved between MCFVv and MCFAh, although both showed similar cytopathicity. Moreover, the induction of cell rounding by MCFVvΔ15-EGFP similar to MCFVv−EΓΦΠ (Fig. 8) strongly argues against such a model.

More plausible models are that autoprocessing is necessary either to activate MCFVv or to release autoinhibition by the first 15 aa of the MCFVv domain. These models are supported by the observation that removal of 15 aa from the N-terminus of MCFVv did not inhibit MCFVv-mediated cell rounding and removal of the first 15 aa facilitates relocalization of the catalytically inactive MCFVv from the cytosol to an intracellular organelle appearing as punctae. We favor a simple allosteric activation in which MCFVv undergoes a structural re-orientation after it binds to the unknown inducer that then allows the scissile bond to position itself in the cleft where the Cys-3351 mediates autoprocessing event. This now active protein would then be in the proper conformation to bind and cleave cellular protein(s) resulting in cytopathicity. In the absence of the conserved processing site residues, cleavage can apparently occur at other residues upstream. Such a model is similar to that of CPD where binding of the activator InsP6 in coordination with insertion of a Leu residue into the active site leads to substrate activation of the nucleophile and autoprocessing, although no other sequence is essential to processing-site recognition. The CPD is then activated to process Xxx-Leu bonds at other sites on the MARTX toxin to release the effector domains (Prochazkova et al., 2008, Shen et al., 2009, Egerer and Satchell, 2010).

Another critical role of autoprocessing may be to generate a residue other than a Leu left by CPD and this residue could be a site for post-translational modification. In support of this idea, we were unable to determine the autoprocessing cleavage site by obtaining the N-terminal sequence of the cleaved band generated during an in vivo cleavage reaction as the N-terminus was blocked against Edman degradation. AvrPphB likewise is an autoproteolytic peptidase that undergoes autoprocessing, but then the newly exposed Gly residue is myristoylated and the neighboring proximal Cys residue palmitoylated (Puri et al., 1997, Shao et al., 2002, Tampakaki et al., 2002, Dowen et al., 2009). These modifications are known to enhance and stabilize the membrane association of the lipidated proteins (Resh, 1999). For MCFVv, a similar model would suggest that autocleavage and post-translational modification of Gly-3219 would facilitate membrane targeting. This modification may not however be myristolation since unlike AvrPphB, MCFVv does not have the same active site residues and the consensus motif for myristoylation [GX2X3X4X5(S/T/A/G/C/N)] (Yamauchi et al., 2010) is not conserved, between these two proteins. Moreover, autocleavage of AvrPphB (and its similar homologs like ORF4, RipT, NopT) depends on residues at the P1, P2 and P3 positions (Gly-Asp-Lys, GDK), while the autoprocessing of MCFVv shows no sequence specificity. Thus, the N-terminal modification that results in blocking Edman degradation cannot be predicted based on analogy to AvrPphB.

Overall, the present study is a major step forward in our understanding of the MCF effector domain of MARTX toxins. Despite many remaining questions, this structure-function analysis of the protein has provided extensive valuable new information detailing the protein requirements for cytopathicity by an effector domain for which there was previously no information. Further, we have found that the C-terminal portion of this effector domain is likely a representative member of a new category of in vivo inducible cysteine peptidase that will in the future impact our understanding of other bacterial toxins, including the Mcf insecticidal toxins and other putative bacterial toxins that have not as yet been investigated in detail.

Experimental procedures

Reagents, media, cell lines, bacterial strains

HeLa, COS-7, HEp-2, HEK293 and HEK293T were cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2 in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM, Life Technologies) containing 10% fetal calf serum (Gemini Bio-Products, West Sacramento, CA), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 1 µg/ml streptomycin. CHO-K1 was cultured in F-12K Medium (Invitrogen) containing 2 mM L-glutamine and 1500 mg/L sodium bicarbonate. The E. coli strains DH5α, TOP10 (Life Technologies), BL21(λDE3) and XL-10 Gold (Agilent technologies) were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) liquid or agar medium containing either 100 µg/ml ampicillin or 50 µg/ml kanamycin.

Restriction enzymes and custom oligonucleotides used for cloning were purchased from New England Biolabs (Beverly, MA) and Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA), respectively. All novel plasmid inserts were confirmed by DNA sequencing carried out at the Northwestern University Genomics Core Facility. Primers and plasmids used are documented in Tables S1 and S2, respectively.

Construction of egfp fusion plasmids

The MCFVv effector domain in the MARTXVv holotoxin from V. vulnificus CMCP6 was defined for this study as 376 amino acids (aa3204–3579) encoded by 9610–10737 bp of the rtxA1 gene VV2_0479. However, for some plasmids, the mcf was extended at the 5′ end to 3159–3579 aa (rtxA1 nt 9475–10737 bp), as this was found to enhance stability of the recombinant proteins.

For V. vulnificus, rtxA1 mcf coding sequence (nt 9610–10737 bp/376 aa) or the same coding sequence with 5′ deletions of 45, 96, 474, and 564 bp were amplified from CMCP6 genomic DNA using Pfx50 DNA polymerase (Life Technologies) and appropriate primers. The PCR amplicons were digested with NheI and KpnI and ligated into similarly digested pEGFP-N3 (Clontech) to generate in-frame fusions with egfp. The ligated mixtures were transformed into TOP10 cells to generate plasmids pSA1 (mcf-egfp), pSA8 (mcfΔ32-egfp), pSA9 (mcfΔ138-egfp), pSA2 (mcfΔ188-egfp) and pSA87 (mcfΔ15-egfp). Single amino acid codon substitutions were generated on pSA1 using Pfu Turbo DNA polymerase (Life Technologies) and oligonucleotides listed in Supplementary table S1. The amplified products were treated with DpnI and were transformed in TOP10 or XL-10 Gold electrocompetent cells. Isolated plasmids were sequenced to confirm the gain of the desired mutation and to check for the absence of unintended mutations during DNA amplification.

For A. hydrophila, DNA corresponding to the mcf coding sequence (rtxA nt 1487730–1488992 bp or aa 2648–3068) was amplified from genomic DNA of ATCC 7966 strain (Supplementary table S1) and the 1263 bp product was digested with NheI and KpnI and ligated with the similarly digested pEGFP-N3 (Clontech). The ligated mixture was transformed into TOP10 cells to generate pSA5 plasmid.

For Ph. luminescens and Ph, asymbiotica, DNA sequences corresponding to mcf1Pl and mcf1Pas were amplified from the genomic DNA of non-sequenced isolates ATCC29999 and ATCC43949, respectively and were captured in the pCR®-Blunt II-TOPO® plasmid (Invitrogen). The DNA sequence of the insert was determined and then codon-optimized G-block® fragments with ends corresponding to the NheI-BamHI restricted pEGFP-N3 were custom synthesized (Integrated DNA Technologies). These G-block® fragments were ligated into pEGFP-N3 (Clontech) using 2× Gibson assembly master mix (New England Biolabs), to generate plasmids, pSA6 and pSA7.

Transient transfection

Prior to transfection, cells were seeded overnight onto 18-mm circular coverslips to achieve ~60% confluency. The cells were then transfected with egfp fusion plasmids using FuGENE® HD (Roche Applied Sciences) according to the manufacturer's protocol. After 18 h, the cells were fixed in 0.5 M PIPES buffer, pH 6.8 containing formaldehyde (3.7%) followed by staining with 1 unit of rhodamine-phalloidin (Life Technologies) and 0.35 µM 4,6-diamino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) dihydrochloride (Life Technologies). EGFP-positive cells were imaged using the Zeiss LSM510 META-UV confocal microscope and images were acquired and overlaid using Zeiss LSM Image Browser V4.2 software. For quantification, at least 50 visually rounded cells were counted per coverslip from at least 3 independent transfection experiments.

For transfection of FLAG-mcf-HA plasmids, HEK293T cells were seeded overnight in 6-well dishes followed by transfection with plasmids as described above.

Western blotting

To verify expression of EGFP-fusion proteins or FLAG-HA-tagged fusion proteins, the cells transfected as described above were lysed in the well using 2× Laemmli SDS-PAGE sample buffer and collected. The lysates were boiled for 5 min and proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, followed by transfer to GE Healthcare Hybond-C nitrocellulose using the BioRad Mini Trans-Blot® system. Western blots were conducted as previously described (Geissler et al., 2010). The blots were incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated monoclonal anti-GFP antibody (1:1000, Miltenyi Biotec Inc., Auburn, CA), rabbit anti-FLAG antibody (1:10,000, F7425, Sigma), rabbit anti-HA antibody (1:10,000, H6908, Sigma) or polyclonal rabbit anti-actin antibody (1:5000, clone Ac-40, A3853, Sigma) followed by the secondary HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:5000, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA). SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent substrate and autoradiography was used for signal detection on X-ray film.

Purification of LFN fusion proteins and Protective antigen (PA) for intoxication assay and circular dichroism

To generate plasmids for purification of recombinant proteins fused to the N-terminus of Bacillus anthracis lethal factor (LFN), an extended mcf (rtxA1 nt 9475–10737 bp) coding sequence was amplified from the genomic DNA of CMCP6 and the 1263 bp product was inserted by ligation-independent cloning (Stols et al., 2002) into pRT24 (Antic et al., 2014) to generate LFN-MCFVv expressing plasmid (pSA3). Site-directed mutations in pSA3 were generated as described above. BL21(λDE3) cells containing pSA3 and mutagenized pSA3 plasmids were grown at 37°C to OD600 ~0.6 and protein expression was induced with 1 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG, Denville Scientific, Metuchen, NJ) for 20 h at 18°C. The protein purification was carried out as previously described(Antic et al., 2014). Protein concentration was determined using the NanoDrop ND1000, and the purity was estimated using SDS-PAGE. All the proteins were stored at −80°C until further use. Protective antigen (PA) and the N-terminus of lethal factor (LFN) were purified using HisTrap and size exclusion chromatography as described previously (Antic et al., 2014).

Twenty-five micrograms of the purified LFN-MCFVv or mutant proteins were analyzed for secondary structure content using a Jasco J-815 circular dichroism (CD) spectrophotometer and Spectra Manager software as described previously (Ahrens et al., 2013). The secondary structure content was deconvoluted using the CDPro software with the CONTIN analysis method (Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, USA).

For intoxication, HeLa cells were grown in 12-well culture dishes to 50% confluency. The cells were treated with either 72 nM LFN or LFN-MCFVv fusion proteins in combination with 168 nM PA followed by incubation for 24 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. For microscopy, the cells were seeded onto coverslips prior to intoxication and processed for confocal microscopy as described above. For DIC images, the cells were imaged at 100 × using a Nikon CoolPix 995 digital camera affixed to a Nikon TS Eclipse 100 microscope. For quantification, rounded cells were manually counted representing at least three independent experiments.

Assay for cell lysis

HeLa cells (5 × 105) were seeded in 12 well dishes overnight and then the medium was exchanged for phenol-red free DMEM containing 10% fetal calf serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 1 µg/ml streptomycin. After transfection or intoxication as described above, cytotoxicity was determined by measuring the release of LDH in 50 µl of the media/supernatant using a CytoTox 96 Non-Radioactive Cytotoxicity Assay Kit (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Purification of MCFVv-His6 tagged for proteins for fluorescence thermal shift assay

To generate plasmids for purification of recombinant 6×His-tagged-MCFVv proteins, an extended mcf (rtxA1 nt 9475–10737 bp) DNA was amplified and the 1263 bp product was inserted by ligation-independent cloning into pMCSG7 (Stols et al., 2002) to create plasmid pSA79 for protein expression. Site-directed mutagenesis on plasmid pSA79 was conducted as described above.

BL21(λDE3) with plasmids were grown to OD600 ~0.6 at 37°C in BD Difco™ Terrific Broth. Protein expression was induced with 1 mM IPTG for overnight at 18°C. Pelleted bacteria were resuspended in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris (pH 8.3), 500 mM NaCl, 0.1 % Triton X-100, and 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol and lysed by sonication. The cell lysate was centrifuged at 30,000×g for 30 min and was loaded by batching onto 0.5 mL Ni+2-NTA (Qiagen) resin, washed in 50 mM Tris, 500 mM NaCl, 50 mM imidazole pH 8.3 and then eluted with 500 mM imidazole. Purified proteins were dialyzed against 50 mM Tris-HCl, 500 mM NaCl, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, pH 8.3 and were stored at −80°C until further use.

Fluorescence thermal shift experiment was performed in a 96-well thin-wall PCR plate (Axigen) with 0.5 µM proteins in Tris-HCl buffer as described previously (Antic et al., 2014). The Tm values were extrapolated using Protein Thermal Shift™ Assay software (Life Technologies).

Construction of pCMV-FLAG-HA expression plasmids

To generate mcf coding sequence (rtxA1 nt 9610–10737 bp/376 aa) containing HA tag at the C-terminus (YPYDVPDYA) and 3×-FLAG tag at the N-terminus (DYKDDDDK) under the control of CMV promoter, 1128 bp DNA was amplified from the V. vulnificus CMCP6 genomic DNA using Pfx50 DNA polymerase (Life Technologies) and appropriate forward and reverse primer carrying the sequence encoding HA tag: 5' TACCCATACGATGTTCCAGATTACGCT 3' (Supplementary table S1). The PCR amplicon was digested with EcoRI and KpnI and ligated into similarly digested p3×FLAG-CMV-7.1 (Sigma). The ligated mixtures were transformed into TOP10 cells to generate plasmids pSA83 (FLAG-mcf-HA). Single amino acid codon substitutions were generated on pSA83 using Pfu Turbo DNA polymerase (Life Technologies) and oligonucleotides (Supplementary table S1). The amplified products were treated with DpnI and were transformed in TOP10 electrocompetent cells. Isolated plasmids were sequenced to confirm the gain of the desired mutation and to check for the absence of unintended mutations during DNA amplification.

In vitro cleavage assay and identification of the proteolytic cleavage site by Edman degradation

The HEK293T CL was prepared according to the protocol of Waterhouse et al (2004). Briefly, HEK293T cells were washed once with PBS, re-suspended in 0.2 ml of ice-cold plasma membrane permeabilization buffer (200 µg/ml digitonin and 80 mM KCl) followed by incubation in ice for 5 min. The lysates were centrifuged at 1500×g for 5 min at 4°C, the supernatant was stored at −80°C and protein concentration was determined using NanoDrop Spectrophotometer ND1000. Thirty micrograms of the cytosolic lysate was incubated with 20 µg of the MCF-His6 or the catalytic inactive mutants in a 40 µl reaction volume for 12 h at 37°C. As control, the proteins with no cell lysate were incubated with the cell permeabilization buffer for the same time period under same conditions to detect any spontaneous time-dependent cleavage. For some assays, 1 mM NEM was added to 10 µg rMCFVv for 30 min at 37°C followed by dialysis at 4°C to remove the excess inhibitor prior to addition of the CL. In other assays, the CL was either boiled for 10 min or treated with 1 µg trypsin at 37°C or proteinase K at 65°C for 2 h. The protease treated CL were inactivated by boiling before addition of rMCFVv to prevent its digestion. Following incubation, 6× SDS-Laemmli sample buffer was added to the samples; they were boiled, and subjected to SDS–PAGE and Coomassie staining.

For the determination of the amino acid sequences in order to identify the cleavage site, an in vitro cleavage assay was performed as described above. The proteins were transferred on to the 0.45 µm PVDF membrane (Millipore), the membrane was stained with Coomassie brilliant blue until the bands were visible. The membrane was then destained with 50% methanol and was air-dried. The band of interest was excised from the PVDF membrane and was subjected to Edman degradation (Edman, 1949) at the Tufts University Core Facility, Boston MA.

Statistical analyses

All the data were graphed as histograms and analyzed using GraphPad Prism 6 for MacIntosh Software (San Diego, CA). Statistical significance was determined in pairwise comparisons using a Student’s t-test.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Kevin Ziolo, Jazel Dolores, and Jennifer Wong are thanked for technical assistance. Heidi Goodrich-Blair (University of Wisconsin-Madison) is thanked for Photorhabdus strains ATCC29999 and ATCC43949, the Northwestern Genomics Core for DNA sequencing services, the Keck Biophysics Facility for use of the Circular Dichroism Spectophotometer, and the Northwestern Center for Advanced Microscopy for microscopy instrumentation. Edman degradation was conducted by Michael Berne at the Tufts University Core Facility. This work was supported by an Investigators in the Pathogenesis of Infectious Disease award from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund and by National Institutes of Health grants R01 AI092825 and R01 AI098369 (to K.J.F.S).

References

- Ahrens S, Geissler B, Satchell KJ. Identification of a His-Asp-Cys catalytic triad essential for function of the Rho inactivation domain (RID) of Vibrio cholerae MARTX toxin. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:1397–1408. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.396309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antic I, Biancucci M, Satchell KJ. Cytotoxicity of the Vibrio vulnificus MARTX toxin Effector DUF5 is linked to the C2A Subdomain. Proteins. 2014;82:2643–2656. doi: 10.1002/prot.24628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung KJ, Cho EJ, Kim MK, Kim YR, Kim SH, Yang HY, et al. RtxA1-induced expression of the small GTPase Rac2 plays a key role in the pathogenicity of Vibrio vulnificus. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:97–105. doi: 10.1086/648612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daborn PJ, Waterfield N, Silva CP, Au CP, Sharma S, Ffrench-Constant RH. A single Photorhabdus gene, makes caterpillars floppy (mcf), allows Escherichia coli to persist within and kill insects. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:10742–10747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.102068099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowen RH, Engel JL, Shao F, Ecker JR, Dixon JE. A family of bacterial cysteine protease type III effectors utilizes acylation-dependent and -independent strategies to localize to plasma membranes. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:15867–15879. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M900519200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling AJ, Daborn PJ, Waterfield NR, Wang P, Streuli CH, ffrench-Constant RH. The insecticidal toxin Makes caterpillars floppy (Mcf) promotes apoptosis in mammalian cells. Cell Microbiol. 2004;6:345–353. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2003.00357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling AJ, Waterfield NR, Hares MC, Le Goff G, Streuli CH, ffrench-Constant RH. The Mcf1 toxin induces apoptosis via the mitochondrial pathway and apoptosis is attenuated by mutation of the BH3-like domain. Cell Microbiol. 2007;9:2470–2484. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.00974.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edman P. A method for the determination of amino acid sequence in peptides. Arch Biochem. 1949;22:475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egerer M, Satchell KJ. Inositol hexakisphosphate-induced autoprocessing of large bacterial protein toxins. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000942. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geissler B, Tungekar R, Satchell KJ. Identification of a conserved membrane localization domain within numerous large bacterial protein toxins. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:5581–5586. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908700107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazen TH, Sahl JW, Fraser CM, Donnenberg MS, Scheutz F, Rasko DA. Refining the pathovar paradigm via phylogenomics of the attaching and effacing Escherichia coli. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:12810–12815. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1306836110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenner C, Hitchin E, Mansfield J, Walters K, Betteridge P, Teverson D, Taylor J. Gene-for-gene interactions between Pseudomonas syringae pv. phaseolicola and phaseolus. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 1991;4:553–562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong HG, Satchell KJ. Additive function of Vibrio vulnificus MARTXVv and VvhA cytolysins promotes rapid growth and epithelial tissue necrosis during intestinal infection. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002581. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones MK, Oliver JD. Vibrio vulnificus: disease and pathogenesis. Infect Immun. 2009;77:1723–1733. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01046-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim BS, Gavin HE, Satchell KJ. Distinct roles of the repeat-containing regions and effector domains of the Vibrio vulnificus multifunctional-autoprocessing repeats-in-toxin (MARTX) toxin. mBio. 2015;6:e00324–e00315. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00324-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HU, Kim SY, Jeong H, Kim TY, Kim JJ, Choy HE, et al. Integrative genome-scale metabolic analysis of Vibrio vulnificus for drug targeting and discovery. Mol Syst Biol. 2011;7:460. doi: 10.1038/msb.2010.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YR, Lee SE, Kook H, Yeom JA, Na HS, Kim SY, et al. Vibrio vulnificus RTX toxin kills host cells only after contact of the bacteria with host cells. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:848–862. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.01088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak JS, Jeong HG, Satchell KJ. Vibrio vulnificus rtxA1 gene recombination generates toxin variants with altered potency during intestinal infection. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:1645–1650. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014339108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee BC, Choi SH, Kim TS. Vibrio vulnificus RTX toxin plays an important role in the apoptotic death of human intestinal epithelial cells exposed to Vibrio vulnificus. Microbes Infect. 2008;10:1504–1513. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Kim MW, Kim BS, Kim SM, Lee BC, Kim TS, Choi SH. Identification and characterization of the Vibrio vulnificus rtxA essential for cytotoxicity in vitro and virulence in mice. J Microbiol. 2007;45:146–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M, Alice AF, Naka H, Crosa JH. The HlyU protein is a positive regulator of rtxA1, a gene responsible for cytotoxicity and virulence in the human pathogen Vibrio vulnificus. Infect Immun. 2007;75:3282–3289. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00045-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo HR, Lin JH, Chen YH, Chen CL, Shao CP, Lai YC, Hor LI. RTX toxin enhances the survival of Vibrio vulnificus during infection by protecting the organism from phagocytosis. J Infect Dis. 2011;203:1866–1874. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H, Wang Z, Shabab M, Oeljeklaus J, Verhelst SH, Kaschani F, et al. A substrate-inspired probe monitors translocation, activation, and subcellular targeting of bacterial type III effector protease AvrPphB. Chem Biol. 2013;20:168–176. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkhill J, Wren BW, Thomson NR, Titball RW, Holden MT, Prentice MB, et al. Genome sequence of Yersinia pestis, the causative agent of plague. Nature. 2001;413:523–527. doi: 10.1038/35097083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pechy-Tarr M, Bruck DJ, Maurhofer M, Fischer E, Vogne C, Henkels MD, et al. Molecular analysis of a novel gene cluster encoding an insect toxin in plant-associated strains of Pseudomonas fluorescens. Environ Microbiol. 2008;10:2368–2386. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochazkova K, Satchell KJ. Structure-function analysis of inositol hexakisphosphate-induced autoprocessing of the Vibrio cholerae multifunctional autoprocessing RTX toxin. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:23656–23664. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803334200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochazkova K, Shuvalova LA, Minasov G, Voburka Z, Anderson WF, Satchell KJ. Structural and molecular mechanism for autoprocessing of MARTX toxin of Vibrio cholerae at multiple sites. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:26557–26568. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.025510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puri N, Jenner C, Bennett M, Stewart R, Mansfield J, Lyons N, Taylor J. Expression of avrPphB, an avirulence gene from Pseudomonas syringae pv. phaseolicola, and the delivery of signals causing the hypersensitive reaction in bean. Mol Plant Microbe In. 1997;10:247–256. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.1997.10.2.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawlings ND, Waller M, Barrett AJ, Bateman A. MEROPS: the database of proteolytic enzymes, their substrates and inhibitors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D503–D509. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resh MD. Fatty acylation of proteins: new insights into membrane targeting of myristoylated and palmitoylated proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1451:1–16. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(99)00075-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roig FJ, Gonzalez-Candelas F, Amaro C. Domain organization and evolution of multifunctional autoprocessing repeats-in-toxin (MARTX) toxin in Vibrio vulnificus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:657–668. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01806-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satchell KJ. Structure and function of MARTX toxins and other large repetitive RTX proteins. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2011;65:71–90. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-090110-102943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seshadri R, Joseph SW, Chopra AK, Sha J, Shaw J, Graf J, et al. Genome sequence of Aeromonas hydrophila ATCC 7966T: jack of all trades. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:8272–8282. doi: 10.1128/JB.00621-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao F, Merritt PM, Bao Z, Innes RW, Dixon JE. A Yersinia effector and a Pseudomonas avirulence protein define a family of cysteine proteases functioning in bacterial pathogenesis. Cell. 2002;109:575–588. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00766-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao F, Vacratsis PO, Bao Z, Bowers KE, Fierke CA, Dixon JE. Biochemical characterization of the Yersinia YopT protease: cleavage site and recognition elements in Rho GTPases. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:904–909. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252770599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheahan KL, Cordero CL, Satchell KJ. Autoprocessing of the Vibrio cholerae RTX toxin by the cysteine protease domain. EMBO J. 2007a;26:2552–2561. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheahan KL, Satchell KJ. Inactivation of small Rho GTPases by the multifunctional RTX toxin from Vibrio cholerae. Cell Microbiol. 2007b;9:1324–1335. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00876.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen A, Lupardus PJ, Albrow VE, Guzzetta A, Powers JC, Garcia KC, Bogyo M. Mechanistic and structural insights into the proteolytic activation of Vibrio cholerae MARTX toxin. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:469–478. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spyres LM, Qa'Dan M, Meader A, Tomasek JJ, Howard EW, Ballard JD. Cytosolic delivery and characterization of the TcdB glucosylating domain by using a heterologous protein fusion. Infect Immun. 2001;69:599–601. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.1.599-601.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stols L, Gu M, Dieckman L, Raffen R, Collart FR, Donnelly MI. A new vector for high-throughput, ligation-independent cloning encoding a tobacco etch virus protease cleavage site. Protein Express Purif. 2002;25:8–15. doi: 10.1006/prep.2001.1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tampakaki AP, Bastaki M, Mansfield JW, Panopoulos NJ. Molecular determinants required for the avirulence function of AvrPphB in bean and other plants. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2002;15:292–300. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2002.15.3.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullah I, Jang EK, Kim MS, Shin JH, Park GS, Khan AR, et al. Identification and Characterization of the Insecticidal Toxin 'Makes Caterpillars Floppy' in Photorhabdus temperata M1021 Using a Cosmid Library. Toxins. 2014;6:2024–2040. doi: 10.3390/toxins6072024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterfield NR, Daborn PJ, Dowling AJ, Yang G, Hares M, ffrench-Constant RH. The insecticidal toxin makes caterpillars floppy 2 (Mcf2) shows similarity to HrmA, an avirulence protein from a plant pathogen. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2003;229:265–270. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00846-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterhouse NJ, Steel R, Kluck R, Trapani JA. Assaying cytochrome C translocation during apoptosis. Methods Mol Biol. 2004;284:307–313. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-816-1:307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wesche J, Elliott JL, Falnes PO, Olsnes S, Collier RJ. Characterization of membrane translocation by anthrax protective antigen. Biochemistry. 1998;37:15737–15746. doi: 10.1021/bi981436i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi S, Fusada N, Hayashi H, Utsumi T, Uozumi N, Endo Y, Tozawa Y. The consensus motif for N-myristoylation of plant proteins in a wheat germ cell-free translation system. FEBS J. 2010;277:3596–3607. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D, de Souza RF, Anantharaman V, Iyer LM, Aravind L. Polymorphic toxin systems: Comprehensive characterization of trafficking modes, processing, mechanisms of action, immunity and ecology using comparative genomics. Biol Direct. 2012;7:18. doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-7-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu M, Shao F, Innes RW, Dixon JE, Xu Z. The crystal structure of Pseudomonas avirulence protein AvrPphB: a papain-like fold with a distinct substrate-binding site. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:302–307. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2036536100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziolo KJ, Jeong HG, Kwak JS, Yang S, Lavker RM, Satchell KJ. Vibrio vulnificus biotype 3 multifunctional autoprocessing RTX toxin is an adenylate cyclase toxin essential for virulence in mice. Infect Immun. 2014;82:2148–2157. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00017-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.