Abstract

Importance

Problem Adaptation Therapy (PATH) is a treatment for older adults with major depression, cognitive impairment (from mild cognitive deficits to moderate dementia) and disability. Antidepressants have limited efficacy in this population and psychosocial interventions are inadequately investigated.

Objective

To test the efficacy of 12-week PATH vs. Supportive Therapy for Cognitively Impaired patients (ST-CI) in reducing depression and disability in 74 older adults with major depression, cognitive impairment and disability.

Design

Randomized Controlled Trial from April 1, 2006 until September 31, 2011.

Setting

Weill-Cornell Institute of Geriatric Psychiatry; interventions were administered at participants’ homes.

Participants

Seventy-four older participants (age≥65 years) with major depression and cognitive impairment up to the level of moderate dementia were recruited through collaborating community agencies of Weill-Cornell Institute of Geriatric Psychiatry and were randomly assigned to 12 weekly sessions of PATH or ST-CI (14.8% attrition rate).

Interventions

Home-delivered PATH vs. home-delivered ST-CI. PATH integrates a problem solving approach with compensatory strategies, environmental adaptations, and caregiver participation to improve patients’ emotion regulation. ST-CI focuses on expression of affect, understanding and empathy.

Main Outcome Measures

Mixed-effects models for longitudinal data compared the efficacy of PATH to that of ST-CI in reducing depression (MADRS) and disability (WHODAS-II) over 12 weeks of treatment.

Results

PATH participants had significantly greater reduction in depression (treatment X time: F[1,179]=8.03, p=0.0051; Cohen’s D at 12 weeks: 0.60) and disability (treatment X time: F[1,169]=14.86, p=0.0002; Cohen’s D at 12 weeks: 0.67) than ST-CI participants over the 12-week period (primary outcomes). Further, PATH participants had significantly greater depression remission rates than ST-CI participants (37.84% vs. 13.51%; Chi-square: 5.74, df=1, p=0.0174; Number Needed to Treat (NNT)=4.11) (secondary outcome). Exploratory analysis showed that PATH led to greater reduction in depression than ST-CI even in the subgroup of participants with drug treatment resistant depression (F[1,72.7]=6.01, p=0.0166; Cohen’s d: week 12: 0.95).

Conclusions and Relevance

PATH was more efficacious than ST-CI in reducing depression and disability. PATH may provide relief to a large group of depressed, cognitively impaired older adults with few treatment options.

INTRODUCTION

Late-life major depression frequently occurs in patients with cognitive impairment with prevalence rates up to 40% [1,2]. Late-life major depression, cognitive impairment and disability contribute to impaired social and interpersonal functioning and increase the risk for poor medical outcomes, nursing home placement, and all-cause-mortality [3–10]. Reducing depression and disability may delay or prevent these adverse outcomes[11].

Available antidepressants have limited efficacy in depressed older adults, and their efficacy is further compromised in those with executive dysfunction[12–14] or dementia[2,15–18], bringing to remission less than 40% of these patients. Moreover, psychosocial interventions for community living older adults with MDD and cognitive impairment have been tested mainly in “young-old” (60–70 years), mildly cognitively impaired, ambulatory patients who can attend outpatient treatment[19, 20]. An exception is a behavioral intervention for depression in dementia [21] that taught caregivers how to problem solve and schedule pleasant events to reduce care-recipients’ depression[21]. However, most participants in that study had moderate to severe dementia and one fourth of them had minor depression [21]. Therefore, existing psychosocial interventions have not adequately investigated older adults with major depression, cognitive impairment up to moderate dementia and disability.

Problem Adaptation Therapy (PATH) is a novel home-delivered psychotherapy designed to decrease depression and disability [22] in older adults with major depression, cognitive deficits up to moderate dementia and disability. PATH aims to improve emotion regulation and reduce the negative impact of behavioral and functional limitations. PATH’s strategies are consistent with the process model of emotion regulation [25,26] (Table 1), which highlights five ways to regulate emotions: situation selection, situation modification, attentional deployment, cognitive change, and response modulation. To achieve emotion regulation, PATH integrates a problem solving approach with compensatory strategies, environmental adaptations and caregiver participation. The home-delivery aspect of PATH, its systematic use of compensatory strategies and environmental adaptations, and its focus on emotion regulation distinguish PATH from other interventions for late-life depression with cognitive impairment[21,23,24].

Table 1.

PATH and the Five Stages of the Process Model of Emotion Regulation.

| Process of Emotion Regulation | Goal | How PATH works |

|---|---|---|

| Situation Selection | Select the situations a person is exposed to | 1. Patient, caregiver (if necessary) and therapist identify situations, problems, concerns that are upsetting to patient and trigger negative emotions associated with depression (e.g. helplessness, hopelessness, worthlessness). A plan is devised to avoid these situations. |

| 2. Patient, caregiver (if necessary) and therapist identifies situations and activities that trigger positive emotions; A plan is devised to promote these situations. | ||

| Situation Modification | Change the situation a person is exposed to | 1. Patient, caregiver (if necessary) and therapist identify compensatory strategies or environmental adaptation tools (e.g. calendar, signs, notes, step-by-step plan) to bypass functional limitations that trigger a strong negative emotional response to patient. |

| 2. The involvement of caregiver is evaluated to modify these emotionally charged situations. | ||

| Attentional Deployment | Shift one’s attention within a situation | Attention, planning, visual and accoustic tools (e.g. notes, shaping procedure to sustain attention, step-by-step plan, timers) are used to bypass functional limitations and redirect patient’s attention to positive aspects of life. |

| Cognitive Change | Change how one thinks about the situation | Therapist helps the patient and caregiver (if necessary) to develop a realistically hopeful approach to functional and cognitive limitations (e.g. cognitive impairment doesn’t necessarily prevent patient from enjoying life; patient may focus on cognitive strengths; environmental adaptation tools may reduce functional limitations) |

| Response Modulation | Direct efforts to alter one’s emotional responses | Therapist helps the patient and caregiver (if necessary) to utilize tools during emotionally charged situations (e.g. using techniques to reduce escalation of tension between patient and caregiver). |

In a pilot study based on a different sample, we reported data on PATH’s feasibility and acceptability [27]. The present study examines the efficacy of 12-week home-delivered PATH vs. Supportive Therapy for Cognitively Impaired patients (ST-CI) in reducing depression and disability in 74 elders with major depression, cognitive impairment up to the level of moderate dementia, and disability. We hypothesized that PATH participants would have greater reduction in depression and disability (primary outcomes) than ST-CI participants over the 12-week treatment. We also compared remission rates, time to remission, as well as patient and caregiver treatment satisfaction between PATH and ST-CI (secondary outcomes). Finally, we explored the treatment effects in older adults with pharmacotherapy resistant depression, and examined whether baseline cognitive impairment moderated treatment outcomes (exploratory analyses).

METHODS

Participants

Seventy four participants (Mean age=80.90; SD=7.48; Range=66–95 yo); 74.32% females) were recruited through collaborating community agencies of Weill-Cornell Institute of Geriatric Psychiatry.

Eligible participants had (1) non-psychotic, unipolar MDD DSM-IV diagnosis (SCID-R)[28]; (2) Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) score≥17 [29] ; (3) at least mild cognitive deficits (age and education-adjusted scaled score of ≤7 on the DRS subscale of Memory or Initiation Perseveration[30]); (4) disability (at least 1 impairment in instrumental activities of daily living [31]); and (5) limited mobility to attend weekly outpatient treatment, based on participant, caregiver or physician’s report. Eligible participants were either: a) not taking antidepressants, cholinesterase inhibitors, or memantine, or b) on a stable dosage for at least 6 weeks prior to study entry without any medical recommendation for medication change in the next 3 months. Pharmacotherapy was uncontrolled and provided by community physicians.

Exclusion criteria included (1) other Axis I psychiatric disorder (except comorbid anxiety disorders); (2) acute or severe medical illness (e.g., metastatic cancer, liver failure); (3) drugs known to cause depression; (4) current involvement in psychotherapy; (5) advanced dementia, i.e. a Mini Mental State Examination score[32] <17; and (6) aphasia or inability to speak English. The participants provided signed informed consent. Involvement of a caregiver was encouraged but not required (Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of 74 Older Adults with Major Depression and Advanced Cognitive Impairment

| PATH (N=37) | ST (N=37) | Fisher’s Exact (p) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Perc (%) | N | Perc (%) | ||

|

|

|

|

|||

| Gender | 0.60 | ||||

| Female | 26 | 70.27 | 25 | 78.38 | |

| Race and Ethnicity | 1.00 | ||||

| Caucasian | 30 | 81.08 | 31 | 83.78 | |

| African-American | 7 | 18.92 | 6 | 16.22 | |

| Hispanic (all Caucasian) | 3 | 8.11 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.24 |

| Probable or Definite | 0.64 | ||||

| Dementia | 21 | 56.76 | 18 | 48.65 | |

| Mild | 12 | 32.43 | 12 | 32.43 | |

| Moderate | 9 | 24.32 | 6 | 16.22 | |

| On Antidepressants | 24 | 64.86 | 23 | 62.16 | 1.00 |

| Drug Treatment Resistant | 15 | 40.54 | 16 | 43.24 | 1.00 |

| Number of Depression Episodes (>=3) | 18 | 54.55 | 17 | 51.52 | 1.00 |

| Any Anxiety Disorders | 12 | 32.43 | 11 | 29.73 | 1.00 |

| On Cognitive Enhancers | 4 | 10.81 | 6 | 16.22 | 0.74 |

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mann-Whitney Wilcoxon | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| z | p | |||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| Age | 80.78 | 7.23 | 81.03 | 7.61 | 0.31 | 0.76 |

| Age at Onset of Depression | 54.92 | 27.53 | 63.06 | 24.08 | 1.09 | 0.28 |

| Education (years) | 12.86 | 3.37 | 13.35 | 2.72 | 0.29 | 0.77 |

| Attended Therapy Sessions# | 10.62 | 3.05 | 10.95 | 2.73 | −0.81 | 0.42 |

| MADRS Total1 | 21.08 | 3.74 | 21.41 | 3.26 | 0.56 | 0.58 |

| WHODAS-12 Total2 | 33.19 | 8.10 | 32.35 | 4.75 | −0.99 | 0.32 |

| MAI IADL Total3 | 18.36 | 3.65 | 19.26 | 4.19 | −0.85 | 0.40 |

| DRS Total4 | 115.80 | 13.88 | 121.14 | 8.97 | −1.37 | 0.17 |

| Executive Dysfunction | ||||||

| DRS IP5 | 27.84 | 5.64 | 28.73 | 4.86 | 0.54 | 0.59 |

| Stroop CW6 | 19.07 | 11.50 | 19.28 | 6.62 | −0.16 | 0.87 |

| Memory | ||||||

| DRS Memory7 | 19.43 | 4.94 | 21.08 | 3.00 | −0.70 | 0.49 |

| HVLT8 | ||||||

| Immediate Recall | 3.31 | 2.06 | 4.11 | 1.31 | −1.75 | 0.08 |

| Delayed Recall | 4.31 | 3.24 | 5.19 | 2.84 | −1.54 | 0.12 |

| Charlson Total9 | 2.79 | 2.20 | 3.32 | 2.78 | 0.58 | 0.57 |

| Intensity of Antidepressant Medication Treatment10 | 1.77 | 1.44 | 1.94 | 1.63 | 0.52 | 0.61 |

90.5% of sub jects who completed the study had 12 therapy sessions, 6.3% had 11 sessions, and 3.2% had 10 session.

Mild Dementia as defined by DRS Total Scaled Score >3 and <=5 after adjusting for age and education (DRS 2 Manual); Moderate Dementia as defined by DRSTotal Scaled Score <=3 after adjusting for age and education (Mild Dementia: Mean DRS Total=118.79, Range=111–126; Moderate Dementia: Mean DRS Total=104.10; Range=78–115).

Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS);

World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule – II -12 items;

Philadelphis Multiphasic Assessment Instrument – Instrumental Activities of Daily Living – Total;

Mattis Dementia Rating Scale – Total;

Mattis Dementia Rating Scale – Initiation / Perseveration Subscale;

Stroop Color -Word Score;

Dementia Rating Scale – Memory Subscale;

Hopkins Verbal Learning Test – Revised;

Charlson Commorbity Index;

Composite Antidepressant Score (CAD) – Revised.

Capacity To Consent

Evaluation with the Cornell Capacity to Consent Scale (available from authors) confirmed comprehension of voluntary participation in research, study risks and benefits, and privacy and confidentiality. A clinician, not affiliated with the study, reviewed the scale and excluded potential subjects with questionable capacity.

Randomization and Masking

Randomization was designed in SAS[33] in blocks of four participants and allocation ratio 1:1. The study coordinator sequentially allocated participants to either PATH or ST-CI. Raters were independent evaluators unaware of randomization status and study hypotheses. Participants were unaware of study hypotheses and were instructed not to reveal their randomization status to raters.

Therapists Training and Treatment Fidelity

Therapists were three clinical psychologists, four clinical social workers, and one clinical doctoral candidate. Each therapist administered both treatments. To control for potential bias, therapists were thoroughly trained and closely supervised, and sessions were evaluated for treatment fidelity. Training consisted of a 2-day workshop and supervision of two training cases per treatment. Treatment fidelity scores were very good to excellent (mean; PATH=4.6 and ST-CI=4.5 out of 5) based on a random review of 20% of first, week 6 and 12 audiotaped sessions. Therapists had weekly group supervision and additional individual supervision as needed.

Assessments and Instruments

Two clinician investigators agreed on the diagnosis after reviewing SCID-R and other ratings, and certified raters performed in-home assessments at study entry (baseline), 4, 8 and 12 weeks. MADRS and the 12-item interviewer-administered World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule II (WHODAS II) [34] were the primary measures for depression and disability respectively. WHODAS-II assesses participant’s difficulty in six domains of functioning: understanding and communicating, moving and getting around, caring for self, interacting with other people, engaging in work and household activities, and participating in the community[34]. Each domain includes two items, scored 1–5, 1=None; 5=Extreme/Cannot Do. The “day to day work activities” item was skipped as most participants did not work. WHODAS-II may predict adverse outcomes in older adults with severe medical burden, i.e. a one-point change in baseline WHODAS-II score was associated with 12% increased risk for severe disability or death in COPD, heart failure, and stroke patients[35]. The Performance Assessment of Self-Care Skills (PASS) was listed in the protocol but omitted early in the trial.

Overall cognitive impairment was assessed with the DRS total score[30], executive dysfunction with the DRS IP and the Stroop Color Word test [36], memory with the DRS Memory Subscale and Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised[37], and medical burden with the Charlson Comorbidity scale[38]. Participants were classified as having probable or definite dementia based on DSM-IV criteria including progressive cognitive decline in the past 6 months and significant impairment in two DRS areas (scaled score ≤5) [30].

Full and partial remission was defined as a MADRS total score ≤7 or ≤10 for two consecutive weeks, respectively. Response was defined as ≥50% reduction in MADRS scores from baseline to week 12. Intensity of pharmacotherapy in the past 4 weeks was measured with the Composite Antidepressant Score – Revised for older adults (CAD) [39, Revised 2013] (eTable 1) based on reports from patients, caregivers and family physicians (0=absence of pharmacotherapy; 1 or 2= inadequate antidepressant treatment; 3 or 4=adequate antidepressant treatment). Pharmacotherapy resistant depression during the index episode was defined as inadequate response (i.e. meeting criteria for MDD and MADRS≥17) despite an adequate antidepressant trial of at least 4 weeks, i.e. CAD score of 3 or 4 [40]. Patient and caregiver’s treatment satisfaction was assessed with the 3-item Client Satisfaction Questionnaire[41] at 4, 8, and 12 weeks (eTable 2).

Interventions

Problem Adaptation Therapy (PATH)

PATH is a home-delivered psychosocial intervention, administered in 12 weekly sessions. It utilizes personalized strategies to regulate emotions (reduce negative and promote positive emotions) and lessen the negative impact of emotions. During the initial two sessions, situations or problems that trigger negative emotions or inhibit positive emotions (e.g. lack of pleasurable activities) are identified. Then the PATH therapist and patient devise a plan to regulate emotions and reduce negative impact by using a hands-on problem-solving approach[42] and integrating PATH tools (environmental adaptations and compensatory strategies, e.g. calendar, checklists, strategies to sustain or shift attention[43], step-by-step division of a task)[44]. When necessary, the caregiver participates in treatment, e.g. facilitates the problem-solving process, promotes pleasurable activities, and helps the patient avoid negatively charged situations[45](Table 1). The most common problems reported were memory and organizational deficits, behavioral/functional limitations, interpersonal tension, social isolation and anhedonia.

Supportive Therapy for Cognitive Impaired Older Adults (ST-CI)

ST-CI was used as an attention control condition. ST-CI is a home-delivered psychotherapy administered in 12 weekly sessions [46] that focus on non-specific therapeutic factors such as facilitating expression of affect, conveying empathy, highlighting successful experiences, and imparting optimism. To parallel the delivery of PATH, willing caregivers were invited to participate in ST-CI sessions.

Statistical Analysis

Data analyses include all eligible participants with baseline assessments following the intent-to-treat principle. We conducted univariate analyses between PATH (N=37) and ST-CI (N=37) on clinical and demographic variables using the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney (continuous) and the Fisher’s exact test (categorical).

Primary Outcomes

We performed mixed-effects models for longitudinal data to compare the efficacy of PATH and ST on depression (MADRS total score) and disability (WHODAS-II total score) over 12 weeks of treatment. The models include time-trend parameters (time and time squared), treatment group, and time by treatment interaction.

Secondary Outcomes

Chi-square tests and Cox Proportional Hazards Models were used to compare full and partial remission and response rates as well as time to full and partial remission. Mixed-effects models analysis was used to compare patient and caregiver’s treatment satisfaction between treatments.

Exploratory analyses

Mixed effect models were also used to: a) compare the course of depression between treatments in patients with pharmacotherapy resistant depression and b) to test moderators on treatment outcomes (depression and disability). The models for testing the moderator included a potential moderator (dementia diagnosis or DRS total at baseline), moderator by treatment interaction, and moderator by treatment by time interaction. A two-tailed alpha level of 0.05 was used for each statistical test. All analyses were performed with SAS 9.2[33].

Sample Size Determination

Based on a between treatment effect size of 0.70 for depression and disability, we predicted that with at least 36 participants per group and 13% attrition rate, we would have at least 0.80 power at 0.05 two-tailed significance level with ICC=.40.

RESULTS

Seventy-four participants were randomized to PATH (N=37) vs. ST-CI (N=37). They suffered from mild to moderate major depression, had significant cognitive impairment (52% met diagnostic criteria for probable or definite dementia), and pronounced disability (Table 1).

Preliminary Analyses

There were no significant differences in demographic or baseline clinical variables between two treatments. Seventy patients had a primary caregiver (PATH=36; ST-CI=34), i.e. children or children-in-law (65.71%), spouse (14.29%), siblings or siblings-in-law (4.29%), other family member (2.86%), and other (including home-aides) (12.86%). Approximately 80% of caregivers had at least one session with the therapist (PATH=30; ST=27). There were no significant differences between treatments on caregiver relationship and gender, or the average number of sessions attended by caregivers (PATH=3.91 vs. ST-CI=3.81). Adverse events were unrelated to the study and comparable between treatments.

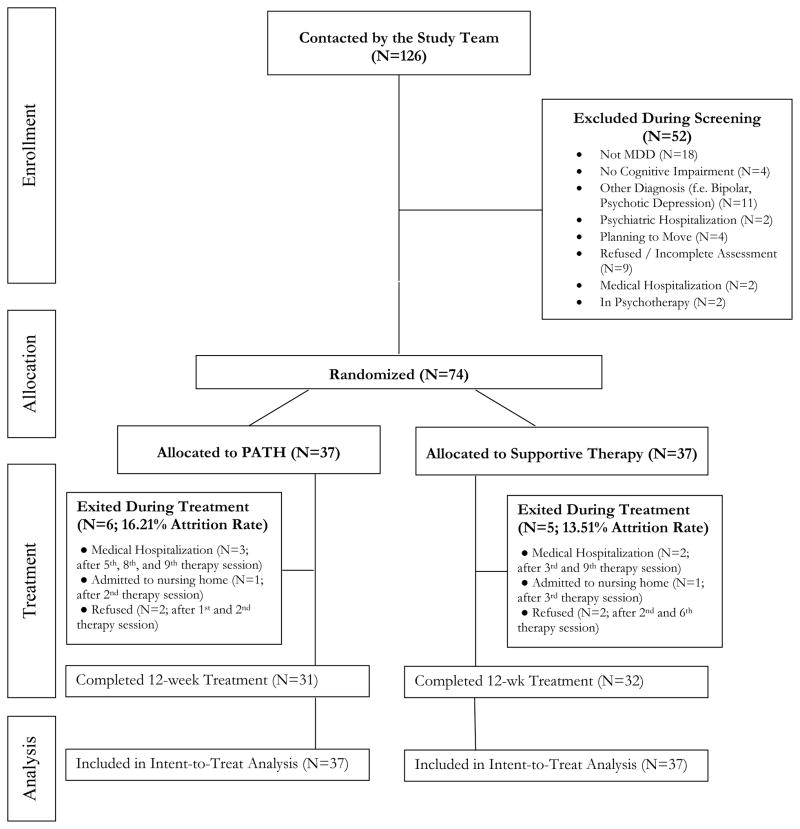

Of the 74 participants randomized, 85.1% completed the assessments (PATH=83.8% vs. ST=86.5%; Fisher’s exact=ns) (Figure 1). There were no significant differences in demographic and baseline characteristics between those who dropped out and those who completed the study.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of participant progress through the phases of the randomized trial.

Primary Outcomes

Depression

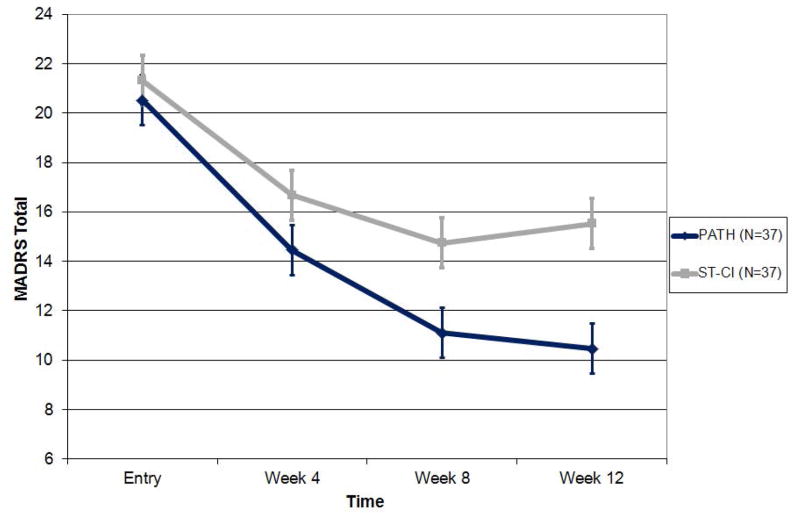

In a mixed-effects model consisting of treatment group, time, time squared, and treatment group by time interaction, PATH participants had significantly greater reduction in depression than ST-CI participants over the 12-week period (treatment group by time interaction: F[1,179]=8.03, p=0.0051; Cohen’s d (95% CI): week 4: 0.38 (−0.07,0.84); week 8: 0.79 (0.31,1.26); week 12: 0.60 (0.13,1.06) (Figure 2). PATH participants had greater reduction by approximately 0.36 (95% CI: 0.60–0.11) MADRS points per week (or 43% greater decline at week 12) than ST-CI participants. PATH participants also had significantly lower depression scores at 8 (t[83.4]=−2.91, p=0.0047) and 12 weeks (t[136]=−3.47, p=0.0007).

Figure 2.

Efficacy of PATH vs. ST-CI in Reducing Depression in 74 Older Adults with Major Depression, Advanced Cognitive Impairment and Disability.

Depression scores over 12 weeks of PATH versus ST in 74 elders with major depression, advanced cognitive impairment, and disability based on the least squares means and standard error of the mixed effects model: time + time squared + treatment + treatment x time.

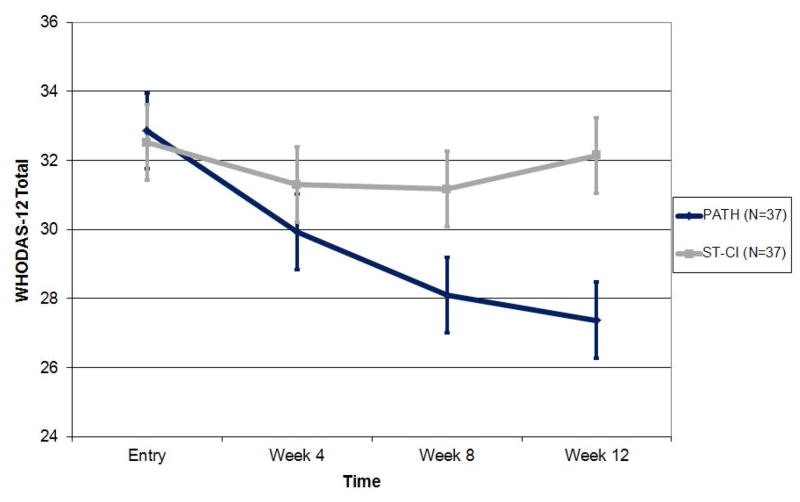

Disability

In a mixed-effects model consisting of treatment group, time, time squared and treatment group by time interaction, PATH participants had significantly greater reduction in disability (WHODAS II total score) than ST-CI participants over the 12-weeek period (treatment group by time interaction: F[1,169]=14.86, p=0.0002; Cohen’s d (95% CI): week 4: 0.44 (−0.02,0.90); week 8: 0.36 (0.20,0.82); week 12: 0.67 (0.20,1.14) (Figure 3). PATH participants had greater reduction by approximately 0.43 (95% CI: 0.64–0.21) WHODAS-II points per week (or 93% greater decline at week 12) than ST-CI participants. Finally, PATH participants had significantly lower disability scores at 8 (t[74.8]=2.13, p=0.0369) and 12 weeks (t[106]=3.00, p=0.0034).

Figure 3.

Efficacy of PATH vs. ST-CI in Reducing Disability in 74 Older Adults with Major Depression, Advanced Cognitive Impairment and Disability.

Disability scores over 12 weeks of PATH versus ST in 74 elders with major depression, advanced cognitive impairment, and disability based on the least squares means and standard error of the mixed effects model: time + time squared + treatment+ treatment x time.

Secondary Outcomes

Full Remission (MADRS ≤7)

PATH participants had significantly greater remission rates at week 12 than ST-CI participants (37.84% vs. 13.51%; Chi-square[1]=5.74, p=0.0174; Number Needed to Treat (NNT)=4.11). Cox proportional hazards model revealed that PATH participants were almost 3.6 times more likely to remit at any point during the 12-week treatment than ST-CI participants (Chi square[1]=5.16, p=0.0232; Hazard Ratio=3.67; 95%CI=1.20–11.26).

Partial Remission (MADRS ≤10)

PATH participants had significantly greater partial remission rates at week 12 than ST-CI participants (62.16% vs. 29.73%; Chi-square[1]=7.84, p=0.0051; NNT=3.08). Cox proportional hazards model revealed that PATH participants were almost 2.9 times more likely to partially remit at any point during the 12-week treatment than ST-CI participants (Chi square[1]=4.02, p=0.0449; Hazard Ratio=2.85; 95%CI=1.03–7.91).

Response

PATH participants had significantly greater response rates (>=50%) than ST-CI participants (66.67% vs. 32.26%; Chi-square[1]=7.22, p=0.0072).

Treatment Satisfaction

Mixed effects models analysis revealed no significant differences on Client Satisfaction Questionnaire scores at week 4, 8 and 12 between PATH vs. ST-CI in participants or caregivers (eTable 2).

Exploratory Analyses

In patients with pharmacotherapy resistant depression (PATH=15 vs. ST-CI=16), PATH participants had significantly greater reduction in depression than ST-CI participants (treatment group by time interaction: F[1,72.7]=6.01, p=0.0166; Cohen’s d (week 12)=0.95. Thirty-four and 67% of PATH participants achieved full and partial remission, respectively. Finally, dementia diagnosis and DRS total at baseline were not significant moderators of depression or disability outcomes.

DISCUSSION

The principal findings of this study are that PATH reduces depression and disability more than ST-CI in older adults with major depression, cognitive impairment and disability. This population is at high risk for morbidity and mortality, pharmacotherapy has limited efficacy and psychotherapies are sparse. Reductions in depression and disability were both statistically and clinically significant. Compared to ST-CI, PATH participants had greater decline in depression (43%) and disability (93%) respectively at week 12.

This is the first randomized trial, to our knowledge, of a psychosocial intervention for community living older adults with major depression and cognitive impairment, of which more than half had dementia. Our findings are consistent with findings in samples with different degrees of depression and cognitive deficits[47]. PST led to greater reduction in depression[23] and disability[24] than ST in elders with major depression and mild executive dysfunction. PST also reduced depression in medically ill home care patients without an MDD diagnosis[48]. Finally, a behavioral treatment, which influenced PATH’s caregiver component, produced similar results in adults with moderate to severe dementia and minor or major depression [21].

Both interventions were well accepted, as evidenced by high treatment satisfaction scores, highlighting that the treatment effects on depression and disability were not a byproduct of patient enjoyment or treatment satisfaction. High satisfaction scores, even in non-remitted patients, may reflect the need for home-delivered treatment in this population[49] who has limited resources. Caregivers’ treatment satisfaction with PATH is consistent with findings that most caregivers find treatment involvement helpful and constructive[50, 51].

Almost 40% of our participants had at least one adequate antidepressant trial for their index episode and still met criteria for MDD. Even among those patients, PATH had significantly greater reduction in depression than ST-CI (Cohen D at week 12: 0.95). These results need to be replicated in an adequately-powered trial yet are promising for a large number of patients with limited treatment options.

PATH’s main innovation is its personalized, structured problem-solving approach, use of compensatory strategies and environmental adaptations, and caregiver participation to improve emotion regulation. The presumed mechanism of action is that PATH reduces depression by improving emotion regulation through situation selection, situation modification, attentional deployment, cognitive change, and response modulation[25, 26]. Future studies are needed to test this mechanism of action and identify aspects of emotion regulation that are more effective in improving outcomes.

Limitations of the study include lack of information on the stability of PATH after 12 weeks, therapists’ allegiance, and low remission rates. Future investigations may evaluate the long-term sustainability of treatment effects and the need for maintenance treatment. As therapists administered both treatments, therapists’ allegiance may have created bias. Future studies may assess the effects of allegiance on treatment outcomes. Nevertheless, therapists were thoroughly trained, closely supervised and achieved high fidelity ratings. Even though PATH full remission rates (MADRS≤7) were low (38%), an additional 25% of PATH participants were partially remitted (MADRS between 8 and 10). Future investigations are needed to examine ways to strengthen PATH’s efficacy and help partially remitted patients achieve full remission, e.g. conducting additional booster sessions for those patients.

Despite its efficacy, PATH faces dissemination challenges[52]. In this study, PATH was delivered at the patient’s home by trained clinicians who may not be available in agencies with limited resources. However, half of our therapists were social workers and were able to administer PATH with high fidelity. Social workers are employed by home health care organizations and their services are reimbursed by Medicare. Treatment fidelity studies of community-based social workers and studies of organizational interventions in home health care services may offer a view on PATH’s dissemination potential. Despite the cost of PATH resources, comparable home-delivered interventions for demented patients are cost-effective[53, 54].

In summary, this study demonstrates the efficacy of PATH vs. ST-CI in reducing depression and disability in community living older adults with depression, cognitive impairment and disability. In this population at risk of adverse outcomes, antidepressants have limited efficacy and psychosocial interventions are inadequately investigated. PATH was efficacious in reducing depression even in a group of older adults with pharmacotherapy resistant depression, but this observation need to be confirmed in an adequately-powered study. Overall, PATH may provide significant relief to this underserved population and their families.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIMH grant K23 MH074659 (PI: D.N. Kiosses) and P30 MH085943 (PI: G.S. Alexopoulos). The funding organization (NIMH) oversaw the design and conduct of the study, as well as collection of data through annual progress reports but did not participate in the analysis, interpretation of the data and the preparation, review or approval of the manuscript.

Dr. Kiosses had full access to all of the data in the study, conducted the data analysis and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Dr. Kiosses has received grant support from Alzheimer’s Association, National Alliance for Research on Depression and Schizophrenia (NARSAD) and the Mental Health Initiative Foundation.

Dr. Alexopoulos has served as a consultant for Pfizer and Otsuka, has received grants from Forest Laboratories, and has received payment for lectures, including service on speakers bureaus, from AstraZeneca, Avanir Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, and Sunovion.

Footnotes

Clinical Trials Registration

Official Title: A Treatment for Depressed, Cognitively Impaired Elders

Identifier: NCT00368940

The rest of the authors do not have any conflicts of interest or financial relationships with commercial interests.

Contributor Information

Dimitris N. Kiosses, Associate Professor of Psychology in Clinical Psychiatry, Weill-Cornell Institute of Geriatric Psychiatry, Weill Cornell Medical College

Lisa D. Ravdin, Associate Professor of Neurology, Weill Cornell Medical College

James J Gross, Professor of Psychology, Stanford University

Patrick Raue, Associate Professor of Psychology, Weill-Cornell Institute of Geriatric Psychiatry, Weill Cornell Medical College

Nabil Kotbi, Assistant Professor of Psychiatry, Weill-Cornell Institute of Geriatric Psychiatry, Weill Cornell Medical College

George S. Alexopoulos, Professor of Psychiatry, Weill-Cornell Institute of Geriatric Psychiatry, Weill Cornell Medical College

References

- 1.Lyketsos CG, Lopez O, Jones B, Fitzpatrick AL, Breitner J, DeKosky S. Prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia and mild cognitive impairment: results from the cardiovascular health study. JAMA. 2002;288(12):1475–83. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.12.1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nelson JC, Devanand DP. A systematic review and meta-analysis of placebo-controlled antidepressant studies in people with depression and dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(4):577–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jayadevappa R1, Malkowicz SB, Chhatre S, Johnson JC, Gallo JJ. The burden of depression in prostate cancer. Psychooncology. 2012;21(12):1338–45. doi: 10.1002/pon.2032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alexopoulos GS, Kiosses DN, Sirey JA, Kanellopoulos D, Novitch RS, Ghosh S, Seirup JK, Raue PJ. Personalised intervention for people with depression and severe COPD. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202(3):235–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.120139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lichtman JH, Froelicher ES, Blumenthal JA, Carney RM, Doering LV, Frasure-Smith N, Freedland KE, Jaffe AS, Leifheit-Limson EC, Sheps DS, Vaccarino V, Wulsin L American Heart Association Statistics Committee of the Council on Epidemiology and Prevention and the Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing. Depression as a risk factor for poor prognosis among patients with acute coronary syndrome: systematic review and recommendations: a scientific statement from the american heart association. Circulation. 2014;129(12):1350–69. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gallo JJ, Morales KH, Bogner HR, Raue PJ, Zee J, Bruce ML, Reynolds CF., 3rd Long term effect of depression care management on mortality in older adults: follow-up of cluster randomized clinical trial in primary care. BMJ. 2013;346:f2570. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f2570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ganguli M, Dodge HH, Mulsant BH. Rates and predictors of mortality in an aging, rural, community-based cohort: the role of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(11):1046–52. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.11.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reynolds CF, 3rd, Alexopoulos GS, Katz IR, Lebowitz BD. Chronic depression in the elderly: approaches for prevention. Drugs Aging. 2001;18(7):507–14. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200118070-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roberts RO, Knopman DS, Geda YE, Cha RH, Roger VL, Petersen RC. Coronary heart disease is associated with non-amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Neurobiol Aging. 2010;31(11):1894–1902. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kales HC, Chen P, Blow FC, Welsh DE, Mellow AM. Rates of clinical depression diagnosis, functional impairment, and nursing home placement in coexisting dementia and depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13(6):441–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.6.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kastenschmidt EK, Kennedy GJ. Depression and anxiety in late life: diagnostic insights and therapeutic options. Mt Sinai J Med. 2011;78(4):527–45. doi: 10.1002/msj.20266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alexopoulos GS, Kiosses DN, Heo M, Murphy CF, Shanmugham B, Gunning-Dixon F. Executive dysfunction and the course of geriatric depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58(3):204–10. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Potter GG, Kittinger JD, Wagner HR, Steffens DC, Krishnan KR. Prefrontal neuropsychological predictors of treatment remission in late-life depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29(12):2266–71. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sneed JR, Roose SP, Keilp JG, Krishnan KR, Alexopoulos GS, Sackeim HA. Response inhibition predicts poor antidepressant treatment response in very old depressed patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15(7):553–63. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3180302513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Vasconcelos Cunha UG, Lopes Rocha F, Avila de Melo R, et al. A placebo-controlled double-blind randomized study of venlafaxine in the treatment of depression in dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2007;24(1):36–41. doi: 10.1159/000102570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenberg PB, Drye LT, Martin BK, et al. DIADS-2 Research Group. Sertraline for the treatment of depression in Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(2):136–45. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181c796eb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Banerjee S, Hellier J, Dewey M, Romeo R, Ballard C, Baldwin R, Bentham P, Fox C, Holmes C, Katona C, Knapp M, Lawton C, Lindesay J, Livingston G, McCrae N, Moniz-Cook E, Murray J, Nurock S, Orrell M, O’Brien J, Poppe M, Thomas A, Walwyn R, Wilson K, Burns A. Sertraline or mirtazapine for depression in dementia (HTA-SADD): a randomised, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;378(9789):403–11. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60830-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reynolds CF, 3rd, Butters MA, Lopez O, Pollock BG, Dew MA, Mulsant BH, Lenze EJ, Holm M, Rogers JC, Mazumdar S, Houck PR, Begley A, Anderson S, Karp JF, Miller MD, Whyte EM, Stack J, Gildengers A, Szanto K, Bensasi S, Kaufer DI, Kamboh MI, DeKosky ST. Maintenance treatment of depression in old age: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled evaluation of the efficacy and safety of donepezil combined with antidepressant pharmacotherapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(1):51–60. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kiosses DN, Leon AC, Areán PA. Psychosocial interventions for late-life major depression: evidence-based treatments, predictors of treatment outcomes, and moderators of treatment effects. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2011;34(2):377–401. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pinquart M, Duberstein PR, Lyness JM. Effects of psychotherapy and other behavioral interventions on clinically depressed older adults: a meta-analysis. Aging Ment Health. 2007;11(6):645–57. doi: 10.1080/13607860701529635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Teri L, Logsdon RG, Uomoto J, McCurry SM. Behavioral treatment of depression in dementia patients: a controlled clinical trial. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1997;52(4):159–66. doi: 10.1093/geronb/52b.4.p159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kiosses DN, Teri L, Velligan DI, Alexopoulos GS. A home-delivered intervention for depressed, cognitively impaired, disabled elders. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;26(3):256–62. doi: 10.1002/gps.2521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Areán PA, Raue P, Mackin RS, Kanellopoulos D, McCulloch C, Alexopoulos GS. Problem-solving therapy and supportive therapy in older adults with major depression and executive dysfunction. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(11):1391–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09091327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alexopoulos GS, Raue PJ, Kiosses DN, et al. Problem-solving therapy and supportive therapy in older adults with major depression and executive dysfunction: effect on disability. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2011;68(1):33–41. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gross JJ. The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Rev Gen Psychol. 1998;2(3):271–299. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gross JJ. Emotion Regulation: Conceptual and Empirical Foundations. In: Gross JJ, editor. Handbook of Emotion Regulation. 2. New York, NY: Guilford; 2014. pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kiosses DN, Arean PA, Teri L, Alexopoulos GS. Home-delivered Problem Adaptation Therapy (PATH) for depressed, cognitively impaired, disabled elders: A preliminary study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(11):988–98. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181d6947d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.First Michael B, Spitzer Robert L, Miriam Gibbon, Williams Janet BW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition. (SCID-I/P) New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; Nov, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134:382–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jurica PJ, Leitten CL, Mattis S. DRS-2. Dementia Rating Scale - 2. Professional Manual. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lawton MP, Moss M, Fulcomer M, Kleban MH. A research and service oriented multilevel assessment instrument. J Gerontol. 1982;37(1):91–9. doi: 10.1093/geronj/37.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-Mental State”: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.SAS version 9.1. SAS Institute; Cary NC: [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ustun B. WHODAS-II Disability Assessment Schedule. NIMH Mental Health Research Conference; 2000; Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Pedro-Cuesta J, García-Sagredo P, Alcalde-Cabero E, Alberquilla A, Damián J, Bosca G, López-Rodríguez F, Carmona M, de Tena-Dávila MJ, García-Olmos L, Salvador CH. Disability transitions after 30 months in three community-dwelling diagnostic groups in Spain. PLoS One. 2013 Oct 31;8(10):e77482. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Golden CJ. The Stroop Color and Word Test (Manual) Chicago: Stoetling; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brandt J, Benedict R. Hopkins Verbal Learning Test - Revised. Psychological Assessment Resources; Lutz, FL: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–83. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alexopoulos GS, Meyers BS, Young RC, et al. Recovery in geriatric depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53(4):305–312. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830040039008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tew JD, Jr, Mulsant BH, Houck PR, et al. Impact of prior treatment exposure on response to antidepressant treatment in late life. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(11):957–65. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000222311.70424.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Larsen DL, Attkisson CC, Hargreaves WA, Nguyen TD. Assessment of client/patient satisfaction: development of a general scale. Eval Program Plann. 1979;2(3):197–207. doi: 10.1016/0149-7189(79)90094-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.D’Zurilla TJ, Nezu AM. Problem-solving therapy: a social competence approach to clinical intervention. New York: Singer; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Silverstein SM, Spaulding WD, Menditto AA, et al. Attention shaping: a reward-based learning method to enhance skills training outcomes in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35(1):222–32. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Velligan DI, Bow-Thomas CC, Huntzinger C, et al. Randomized controlled trial of the use of compensatory strategies to enhance adaptive functioning in outpatients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(8):1317–23. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.8.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kiosses DN, Alexopoulos GS. Problem Adaptation Therapy (PATH) for Older Adults with Major Depression and Cognitive Impairment. 2013 doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1305. (unpublished manual) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sacks MH. Manual for Supportive Therapy (ST) for Depressed, Cognitively Impaired Elders. 2010 (unpublished manual) [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wetherell JL. Psychotherapy for depression with executive dysfunction. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(11):1297–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10081161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gellis ZD, McGinty J, Horowitz A, Bruce ML, Misener E. Problem-solving therapy for late-life depression in home care: a randomized field trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15(11):968–78. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3180cc2bd7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gum AM, Iser L, Petkus A. Behavioral health service utilization and preferences of older adults receiving home-based aging services. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(6):491–501. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181c29495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gitlin LN, Corcoran M, Winter L, Boyce A, Hauck WW. A randomized, controlled trial of a home environmental intervention: effect on efficacy and upset in caregivers and on daily function of persons with dementia. Gerontologist. 2001;41(1):4–14. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rabinowitz YG, Mausbach BT, Gallagher-Thompson D. Self-efficacy as a moderator of the relationship between care recipient memory and behavioral problems and caregiver depression in female dementia caregivers. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23(4):389–94. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181b6f74d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Depp C, Lebowitz BD. Clinical trials: bridging the gap between efficacy and effectiveness. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2007;19(5):531–9. doi: 10.1080/09540260701563320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gitlin LN, Hodgson N, Jutkowitz E, Pizzi L. The cost-effectiveness of a nonpharmacologic intervention for individuals with dementia and family caregivers: the tailored activity program. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(6):510–9. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181c37d13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Graff MJ, Adang EM, Vernooij-Dassen MJ, et al. Community occupational therapy for older patients with dementia and their care givers: cost effectiveness study. BMJ. 2008;336(7636):134–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39408.481898.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.