Abstract

This cross-sectional study examined whether spirituality moderates the association between depression symptom severity and meaning in life among treatment-seeking adults. Participants were 55 adults (≥ 60 years of age) newly seeking outpatient mental health treatment for mood, anxiety, or adjustment disorders. Self-report questionnaires measured depression symptom severity (Patient Health Questionnaire-9), spirituality (Spirituality Transcendence Index), and meaning in life (Geriatric Suicide Ideation Scale-Meaning in Life subscale). Results indicated a significant interaction between spirituality and depression symptom severity on meaning in life scores (β = .26, p = .02). A significant negative association between depression symptom severity and meaning in life was observed at lower but not the highest levels of spirituality. In the presence of elevated depressive symptomatology, those participants who reported high levels of spirituality reported comparable levels of meaning in life to those without elevated depressive symptomatology. Assessment of older adult patients’ spirituality can reveal ways that spiritual beliefs and practices can be can be incorporated into therapy to enhance meaning in life.

Sustaining meaning or purpose in life is an indicator of overall well-being in older adulthood (Crowther, Parker, Achenbaum, Larimore, & Koenig, 2002; Fry, 2000, 2001; Krause, 2004, 2009; Reker, Peacock, & Wong, 1987; Steger, Oishi, & Kashdan, 2009) and is associated with lower levels of depressive symptoms (Heisel & Flett, 2006; Steger, Mann, Michels, & Cooper, 2009; Van Orden, Bamonti, King, & Duberstein, 2012). Older adults with clinically significant depressive symptoms may be particularly vulnerable to thinking life is meaningless (Reker, 1997). Depression is associated with reduced positive affect (Fiske, Wetherell, & Gatz, 2009; Gallo & Rabins, 1999), and disengagement from positively reinforcing events (Dimidjian, Barrera, Martell, Munoz, & Lewinsohn, 2011; Lewinsohn, Hoberman, Teri, & Hautziner, 1985) that serve to create or sustain meaning. Greater levels of depressive symptoms have been shown to be associated with lower meaning in life cross-sectionally (Heisel & Flett, 2006) and prospectively (Van Orden et al., 2012). However, not all older adults with depression report lower meaning in life (Heisel & Flett, 2006).

Identifying factors that are associated with meaning in life among older adults in specialty mental health treatment may provide insight into intervention strategies that can help sustain and protect against the loss of meaning in life. Spirituality is one such factor, given meta-analytic findings demonstrating positive associations between spirituality and well-being (Smith, McCullough, & Poll, 2003). Religion and spirituality represent closely related, but distinct constructs (Hill & Pargament, 2003). Spirituality refers to an individual’s experience of the sacred, while religion commonly refers to organized religious activities (Hill & Pargament, 2003). Greater spirituality is associated with lower depressive symptoms (Mofidi et al., 2006; Nelson, Rosenfeld, Breitbart, & Galietta, 2002; Yoon & Lee, 2004), greater psychological well-being (Bush et al., 2012; Fry, 2001), and greater levels of positive affect (Kim, Seidlitz, Ro, Evinger, & Duberstein, 2004). One study found that spirituality attenuated the negative association between frailty and psychological well-being in older adults (Kirby, Coleman, & Daley, 2004), but we are aware of no studies that have examined whether spirituality attenuates the association between depression symptom severity and meaning in life.

There is good reason to predict that spirituality attenuates the relationship between depression symptoms severity and feelings of meaninglessness. First, highly spiritual individuals may more readily engage in meditation or prayer and may more readily access and benefit from social support (Hill & Pargament, 2003). As such, some of the behaviors associated with spirituality may function to mitigate the negative effect of depressive symptoms on meaning in life. Second, highly spiritual individuals may appraise their depressive symptoms in different ways (Wittink, Joo, Lewis, & Barg, 2009). For example, highly spiritual individuals may view depression more as a challenge to overcome and less as a helpless, uncontrollable state.

The purpose of the current study was to examine whether spirituality attenuates the association between depression symptom severity and meaning in life in older adults seeking mental health treatment. It was hypothesized that spirituality would moderate the association between depression symptom severity and meaning in life, such that the negative association between depression symptom severity and meaning in life would be stronger at lower levels of spirituality. Prior research has shown that social support and cognitive status are associated with meaning in life (Krause, 2007; Wilson et al., 2013), thus we planned to control for these variables.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 55 adults who completed a larger study examining depression and decision-making in late-life. English-speaking patients recently presenting for treatment for mood, anxiety, or adjustment disorder (i.e., < 1 month after intake session) at a university-affiliated outpatient clinic serving adults 60 years of age and older were eligible for inclusion. Patients who were unable to provide informed consent and those with dementia, schizoaffective disorder, or schizophrenia were not eligible given that the main focus of the study was to examine outcomes for mood and anxiety disorders among older adult outpatients.

Prior to the research interview, chart diagnoses were made by an intake social worker. Of the 55 enrolled participants, one was dropped because of ineligible diagnosis and four were dropped because of missing data on a covariate (social support), leaving 50 participants. Participants had a mean age of 69 years (SD = 9.0 years, range = 60–97 years) and n = 31 were female. Most were White (n = 39); nine were Black; two were other or mixed race. For most participants, the primary diagnosis was a mood disorder (n=40); five had an anxiety disorder and five had an adjustment disorder (9.3%). Twenty-two participants were diagnosed with two or more Axis I disorders (4th ed., test rev.; DSM-IV-TR; American Psychiatric Association, 2002)..

Measures

Depression symptom severity was measured with the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9; Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, 2001), a 9-item measure of depression severity corresponding to the nine criteria upon which the diagnosis of DSM-IV depressive disorders is based. Scores can range from 0 to 27. The PHQ-9 has been validated in older adult samples (Williams et al., 2005). Internal consistency in the present sample (Cronbach’s α = .79) was adequate (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994)..

Spirituality was measured with the Spiritual Transcendence Index (STI; Seidlitz et al., 2002), an 8-item measure of an individual’s “subjective experience of the sacred” (Seidlitz et al., 2002, p. 441). Items are scored from “1” (strongly disagree) to “6” (strongly agree). Scores can range from 8 to 48. Higher scores reflect greater levels of spirituality. Sample items include “My spirituality gives me a sense of fulfillment” and “I maintain an inner awareness of God’s presence in my life.” Construct validity and reliability of scores derived from the STI have been demonstrated in older adult samples (Seidlitz et al., 2002). Internal consistency in the current study (α = .97) was good (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994).

Meaning in Life was measured with the 8-item “meaning in life” subscale from the Geriatric Suicide Ideation Scale (GSIS; Heisel & Flett, 2006) assessing one’s perception of meaning or purpose in life. Items are scored on a Likert scale from “1” (strongly disagree) to “5” (strongly agree). Scores can range from 8 to 40. Higher scores reflect greater meaning in life. Research has supported the construct validity and reliability of scores derived from the GSIS (Heisel & Flett, 2006). Sample items include, “I feel that my life is meaningful”, “I am certain that I have something to live for”, and “I have come to accept life with all its ups and downs.” Internal consistency in the current study (α = .89) was adequate (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994)

Cognitive Status was measured using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) a brief, 30-item screening tool for mild cognitive impairment (Nasreddine et al., 2005) with lower scores indicating more cognitive impairment. Scores can range from 0 to 30. The MoCA has demonstrated good test-retest reliability (Nasreddine et al., 2005), and convergent validity with a full neuropsychological battery (Gill, Freshman, Blender, & Ravina, 2008). The MoCA was administered to characterize the sample regarding overall cognitive functioning. It was not intended to exclude individuals from participation in the study.

Social Support was measured with the Perceived Social Support-Family Subscale (PSS-Family; Procidano & Heller, 1983), a 20-item self-report measure of the extent to which an individual perceives receiving support, information, and feedback from their family. Items include declarative statements to which individuals are given the response choices of “Yes,” “No,” or “Don’t know.” Affirmative responses receive 1 point, with all other responses receiving 0 points, with a minimum possible total score of 0 and maximum possible score of 20. Higher scores are indicative of higher levels of perceived social support. An example item includes, “My family gives me the moral support I need.” Scores on PSS-family subscale have demonstrated construct validity in adult samples with correlations in the expected direction and magnitude with measures of tangible and intangible social support and symptoms of distress and psychopathology (Procidano & Heller, 1983). Internal consistency in the current study (α = .93) was good (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994). Seven participants completed 15 to 19 PSS-family items. Missing data were imputed.

Procedures

From April 2008 to April 2010, clerical staff members distributed letters of invitation to new patients immediately preceding their initial clinic appointment. Interested participants who met eligibility criteria were then contacted by a member of the research team. Two participants had particularly low MoCA scores (11 and 12, respectively) but retained capacity to consent to the study. In addition, their scores on study variables were not outliers, nor suggestive of unreliable responding. Therefore, they were included in the current analyses.

Study entry interviews took place at the clinic or at participants’ residence, according to preferences. Within one month following initial presentation to the clinic, data were collected in an in-person interview and by mail. Depression symptom severity and cognitive status were assessed in-person. Participants returned meaning in life, spirituality, and social support assessments by mail after completing these questionnaires at home.

Data Analytic Strategy

SPSS (Version 21) was used for data analyses. Missing data were handled by mean imputation. Following preliminary analyses (e.g., descriptives, correlations), we conducted a linear regression. The outcome variable was Meaning in Life, as assessed by the GSIS. Independent variables were depression symptom severity (PHQ-9) and spirituality (STI). In addition to exploring main effects, we tested the hypothesized moderator effect (PHQ-9 x STI). Given the small sample size only covariates that were significantly associated with meaning in life were included in the regression model (Weisberg, 1979); thus, social support (PSS-Family) was included as a covariate. Predictors were centered prior to creation of the interaction term. Simple slopes of depression symptom severity on meaning in life scores across the range of spirituality scores were examined. Given the small sample size, standard errors were computed using robust bootstrapping estimates (1000 samples and 95% CI) for the regression model, as well as simple slope analyses.

Results

Descriptive statistics and Pearson’s correlations are presented in Table 1. Meaning in life was significantly positively associated with greater spirituality and greater family social support and significantly negatively associated with depressive symptom severity. MoCA was not significantly associated with MIL and subsequently not included in the regression model. Spirituality and depressive symptom severity were not significantly correlated.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Pearson’s Correlations (n = 50)

| Measure | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PHQ-9 | ----- | ||||

| 2 | STI | −.02 | ----- | |||

| 3 | MIL | −.39** | .30* | ----- | ||

| 4 | MoCA | .10 | −.25 | .02 | ----- | |

| 5 | PSS-Family | −.33* | −.14 | .30* | .04 | ----- |

| Mean | 9.0 | 35.7 | 30.4 | 23.3 | 10.5 | |

| SD | 6.0 | 10.6 | 6.1 | 4.2 | 4.9 | |

| Range | 0–24 | 8–48 | 16–40 | 11–29 | 2–18 | |

| N | 50 | 50 | 50 | 49 | 50 |

Note. STI, Spiritual Transcendence Index; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; MIL, Geriatric Suicide Ideation, Meaning In Life Subscale; MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; PSS-Family, Perceived Social Support-Family Subscale.

p < .05.

p < .01

The full regression model was significant, (R2 = .35, Adjusted R2 = .29, F(4, 45) = 6.06, p < 001). Spirituality was positively associated with meaning in life (β = .27 p = .04), but PSS-family was not significantly associated with MIL (β = .20, p = .13). Depressive symptoms severity was negatively associated with meaning in life (β = −.37, p = .01). However, the main effects of spirituality and depression symptom severity were qualified, as hypothesized, by a significant two-way interaction between depression symptom severity and spirituality (β = .26, p = .02; Table 2).

Table 2.

Linear Regression Analysis Predicting Meaning in Life (n = 50)

| Predictor | f2 | B | SE | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| .54 | ||||

| PSS-family | .26 | .16 | .121 | |

| PHQ-9 | −.38 | .13 | .009 | |

| STI | .16 | .08 | .047 | |

| PHQ-9 x STI | .03 | .01 | .021 |

Note. Perceived Social Support-Family Subscale; STI, Spiritual Transcendence Index; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; STI, Spiritual Transcendence Index.

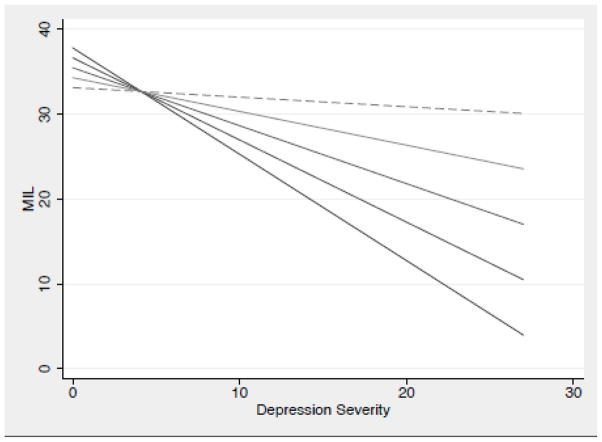

Figure 1 depicts the results of simple slopes analyses (Table 3) across the range of spirituality scores (8–48) in this sample. At lower levels of spirituality (STI = 8–38), there was a significant, inverse association between PHQ-9 and MIL. However, at the highest level of spirituality (STI = 48), there was a non-significant, inverse association between PHQ-9 and MIL. Participants who reported elevated depressive symptom severity and lower spirituality reported the lowest meaning in life. Participants who reported elevated depressive symptom severity, but also endorsed greater spirituality, reported relatively greater meaning in life compared to participants who reported lower spirituality.

Figure 1.

Simple slope analyses depicting the interaction of depressive symptom severity and spirituality on meaning in life

Note. Lines represent spirituality, with the top line representing the highest level of spirituality (STI = 48) and subsequent lines representing lower levels of spirituality in 10 point intervals (48, 38, …). Solid lines indicate statistically significant simple slopes, while dashed lines indicate non-significant simple slopes.

Table 3.

Simple slopes of depressive symptom severity on meaning in life across the range of spirituality scores

| Spirituality score | Slope | Std error | z | p | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | −1.253 | 0.452 | −2.770 | 0.006 | −2.139, −0.368 |

| 18 | −.968 | 0.315 | −3.070 | 0.002 | −1.585, −0.351 |

| 28 | −.683 | 0.190 | −3.600 | 0.000 | −1.055, −0.311 |

| 38 | −.398 | 0.120 | −3.310 | 0.001 | −0.633, −0.162 |

| 48 | −.112 | 0.186 | −0.600 | 0.546 | −0.477, 0.252 |

Discussion

The current study supported the hypothesis that spirituality moderates the association between depression symptom severity and meaning in life among older adults in outpatient mental health treatment. At lower levels of spirituality, there was a robust association between depression symptom severity and feeling that life is meaningless. At high levels of spirituality, the relationship between depressive symptoms and feelings of meaninglessness is attenuated and non-significant. At lower levels of depression, meaning in life was high for most participants. However, at elevated levels of depression, levels of meaning in life varied, with those who reported high levels of spirituality reporting comparable levels of meaning in life to those without elevated depression. Although previous studies have reliably found a negative association between depression symptoms and meaning in life, little attention has been given to factors that moderate this association. The present cross-sectional findings provide an empirical basis for hypotheses about the protective function of spirituality against loss of meaning in life in the presence of elevated depressive symptomatology. Prospective designs are needed to test whether spirituality protects against loss of meaning in life over time.

How might spirituality attenuate the relationship between depression symptom severity and meaning in life? First, social behaviors associated with spirituality may explain the moderation effect. For example, highly spiritual individuals report greater quality of perceived social support and greater social support seeking (Koenig & Larson, 2001). Social support is associated with greater meaning in life (Harris, Allen, Dunn, & Parmelee, 2013). Additionally, emotional support has been found to protect against loss of meaning in life in the context of stress in highly valued roles among older adults (Krause, 2004). Second, spirituality is associated with certain contemplative behaviors that relate to overall well-being, such as prayer, meditation, and worship that are inherently meaningful to many (Hill & Pargament, 2003).

Third, spirituality may influence cognitive appraisals that older adults with depression symptoms make about their experiences with depression, as well as other life events. For example, highly spiritual older adults may be less likely to attribute the cause of their depression to personal failure, but rather use their experiences of emotional suffering to create meaning and purpose in life (Park, 2010; Wittink et al., 2008).

These findings need to be considered in the context of the study’s limitations. First, the study was cross-sectional; therefore, we were unable to determine the directionality of the findings. Second, the current sample was small. Future research with a larger sample of older adults seeking mental health treatment is required to elucidate the influence of spirituality on meaning in life in more diverse samples of older adults. Third, the current study did not measure particular spiritual behaviors, such as prayer or meditation. Such behaviors may differentially relate to meaning in life, or serve as the behavioral mechanism whereby spirituality is associated with greater meaning in life. Fourth, the assessment of cognitive functioning was limited to a brief screening instrument. Cognitive decline as measured by a neuropsychological battery is associated with decrements in well-being over time, particularly in purpose in life (Wilson et al., 2014). While the current study did not find a significant association between cognitive functioning, as measured by a screening instrument, and meaning in life, comprehensive assessment of cognitive functioning may be more likely to demonstrate a significant association. Fifth, information regarding the type of psychological and/or pharmacological treatment received by patients in the sample was not collected, therefore it is unknown whether type of treatment affected findings. Rate of change in depression symptomatology may differ based on treatment type, potentially influencing the association between depression symptom severity and meaning in life. In addition, psychological treatment is apt to incorporate personal values, such as spirituality into the intervention, which could theoretically lead to changes in the association between variables, as well as subjective levels of spirituality across treatment. Lastly, data on religiosity were unavailable. Assessment of religiosity, as well as spirituality would aid in distinguishing similar or different functions each value system serves in relation to meaning in life.

Prospective research with a larger sample size is needed to test whether spirituality can protect against the erosion of meaning in life among distressed older adults. In addition, future studies could identify clinically meaningful mechanisms linking spirituality and meaning in life, such as social support and cognitive appraisals of stressful life events. Given the growing literature on the cognitive underpinnings of meaning or purpose in life (Wilson et al., 2013), future studies should include more sophisticated cognitive assessments such as measures of executive function. Prospective studies could also explore other outcomes of meaning erosion, such as suicide risk (Heisel & Flett, 2008) and impaired quality of life. Meaning in life is one of the few identified protective factors against suicide ideation in older adults (Heisel & Flett, 2008). The present results encourage the inclusion of religion and spiritual components into late life suicide prevention efforts.

Regarding clinical implications, spirituality, for many older adults, may be viewed as more of a “way of being” than a specific coping strategy. Nonetheless, our findings suggest that reinforcing behaviors, such as prayer and meditation, may be important treatment goals. Among mental health treatment-seeking older adults, a majority reported a preference for incorporating spirituality into mental health treatment (Stanley et al., 2011). Not all mental health treatments can readily incorporate religion and spirituality, however. One particularly promising intervention in this regard is life review, which has been shown to reduce depression symptoms by enhancing meaning in life (Westerhof, Bohlmeijer, van Beljouw, & Pot, 2010). Life review specifically targets meaning in life through recollection of memories and reappraisal of positive and negative past events (Westerhof et al., 2010). Within the context of life review, spirituality can be incorporated, as appropriate, as a framework for creating meaning and purpose in life. As such, spirituality can serve in to foster identify development and death preparation depending on the individual case. As religion and spirituality has gained greater attention in recent years in the mental health field, clinicians must consider their level of competency in incorporating religious and spiritual issues into psychotherapy and explore their own personal biases (Gonsiorek, Richards, Pargament, & McMinn, 2009). The American Psychological Association’s (APA) Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct (originally adopted 2002, with amendments adopted 2010; APA, 2010) under Principle E: Respect for People’s Rights and Dignity states that psychologists should be aware of and consider religion and spirituality as an individual diversity factor. However, little guidance has been provided as to when and how to incorporate spirituality into evidenced-based treatments (Plante, 2007). Future studies examining evidenced-based psychosocial treatments for depression in older adults could consider integrating spiritual components to existing treatment modules. Given that depression is marked by behavioral deactivation, for some older adults this deactivation could manifest as a reduction in spiritual activity. In the service of fostering meaning in life, an early psychotherapeutic focus on re-engaging in spiritual activities could be beneficial for those older adults for whom spirituality is a primary value.

In conclusion, the aim of this current study was to examine whether spirituality moderated the association between depression symptoms severity and meaning in life among treatment-seeking older adults. Depressive symptom severity was not significantly related to meaning in life among more highly spiritual older adults: in the presence of elevated depressive symptomatology, those participants who reported high levels of spirituality reported comparable levels of meaning in life to those without elevated depressive symptomatology. These findings generate important questions for future research, including examining possible behavioral and cognitive mediators of the spirituality effect observed such as social support, prayer, meditation, and cognitive appraisal of life events and the meaning of depression. Clinically, the findings suggest that when working with older adults with depressive symptoms, assessment of an individual’s spiritual beliefs could be part of a comprehensive psychosocial history. On a case-by-case basis, an individual’s spiritual beliefs can be discussed and incorporated into treatment strategies to target depressed mood and foster meaning in life.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by KL2RR024136, K23MH096936, and K24MH072712

Contributor Information

Patricia Bamonti, West Virginia University.

Sarah Lombardi, University of Rochester.

Paul R. Duberstein, University of Rochester

Deborah A. King, University of Rochester

Kimberly A. Van Orden, University of Rochester

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: Author; 2000. text rev. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct. American Psychologist. 2002;57:1060–1073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baetz M, Toews J. Clinical implications of research on religion, spirituality, and mental health. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;54:292–301. doi: 10.1177/070674370905400503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera TL, Zeno D, Bush AL, Barber CR, Stanley MA. Integrating religion and spirituality into treatment for late-life anxiety: Three case studies. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2012;19:346–358. [Google Scholar]

- Bush AL, Jameson JP, Barrera T, Phillips LL, Lachner N, Evans G, Stanley MA. An evaluation of the brief multidimensional measure of religiousness/spirituality in older patients with prior depression or anxiety. Mental Health, Religion & Culture. 2012;15:191–203. [Google Scholar]

- Crowther MR, Parker MW, Achenbaum WA, Larimore WL, Koenig HG. Rowe and Kahn’s Model of Successful Aging Revisited Positive Spirituality—The Forgotten Factor. The Gerontologist. 2002;42:613–620. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.5.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimidjian S, Barrera M, Jr, Martell C, Muñoz RF, Lewinsohn PM. The origins and current status of behavioral activation treatments for depression. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2011;7:1–38. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032210-104535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiske A, Wetherell JL, Gatz M. Depression in older adults. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2008;5:363–389. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.032408.153621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry PS. Religious involvement, spirituality and personal meaning for life: Existential predictors of psychological wellbeing in community-residing and institutional care elders. Aging & Mental Health. 2000;4:375–387. [Google Scholar]

- Fry PS. The unique contribution of key existential factors to the prediction of psychological well-being of older adults following spousal loss. The Gerontologist. 2001;41:69–81. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo JJ, Rabins PV. Depression without sadness: alternative presentations of depression in late life. American Family Physician. 1999;60:820–826. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George LK, Larson DB, Koenig HG, McCullough ME. Spirituality and health: What we know, what we need to know. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2000;19:102–116. [Google Scholar]

- Gill DJ, Freshman A, Blender JA, Ravina B. The Montreal cognitive assessment as a screening tool for cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders. 2008;23:1043–1046. doi: 10.1002/mds.22017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonsiorek JC, Richards PS, Pargament KI, McMinn MR. Ethical challenges and opportunities at the edge: Incorporating spirituality and religion into psychotherapy. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2009;40:385a. [Google Scholar]

- Harris GM, Allen RS, Dunn L, Parmelee P. ‘Trouble won’t last always’: Religious coping and meaning in the stress process. Qualitative Health Research. 2013;23:773–781. doi: 10.1177/1049732313482590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heisel MJ, Flett GL. The development and initial validation of the Geriatric Suicide Ideation Scale. American Journal of Geriatric Psychology. 2006;14:742–751. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000218699.27899.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heisel MJ, Flett GL. Psychological resilience to suicide ideation among older adults. Clinical Gerontologist. 2008;31:51–70. [Google Scholar]

- Hill PC, Pargament KI. Advances in the conceptualization and measurement of religion and spirituality: Implications for physical and mental health research. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. 2003;S1:3–17. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.58.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Macintosh, Version 21.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp; Released 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Seidlitz L, Ro Y, Evinger JS, Duberstein PR. Spirituality and affect: a function of changes in religious affiliation. Personality and Individual Differences. 2004;37:861–870. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby SE, Coleman PG, Daley D. Spirituality and well-being in frail and nonfrail older adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2004;59:123–129. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.3.p123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG, Larson DB. Religion and mental health: Evidence for an association. International Review of Psychiatry. 2001;13:67–78. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Stressors arising in highly valued roles, meaning in life, and the physical health status of older adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2004;59:S287–S297. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.5.s287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Longitudinal study of social support and meaning in life. Psychology and Aging. 2007;22:456–469. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.22.3.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Meaning in life and mortality. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2009;64:517–527. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM. A behavioral approach to depression. In: Friedman RM, Katz MM, editors. The psychology of depression: Contemporary theory and research. New York: Wiley; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Hoberman H, Teri L, Hautzinger M. An integrative theory of depression. In: Reiss S, Bootzin RR, editors. Theoretical issues in behavior therapy. New York Academic Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Miller S, Segal DL, Coolidge FL. A comparison of suicidal thinking and reasons for living among younger and older adults. Death Studies. 2001;25:357–365. doi: 10.1080/07481180126250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mofidi M, DeVellis RF, Blazer DG, DeVellis BM, Panter AT, Jordan JM. Spirituality and depressive symptoms in a racially diverse US sample of community-dwelling adults. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2006;194:975–977. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000243825.14449.de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bedirian V, Charbonneau S, Whitehead V, Collin I, Chertkow H. The montreal cognitive assessment, MoCA: A brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2005;53:695–699. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson CJ, Rosenfeld B, Breitbart W, Galietta M. Spirituality, religion, and depression in the terminally ill. Psychosomatics. 2002;43:213–220. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.43.3.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH. Psychometric theory. 3. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Park CL. Making sense of meaning literature: an integrative review of meaning making and its effects on adjustment to stressful life events. Psychological Bulletin. 2010;136:257–301. doi: 10.1037/a0018301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker M, Lee Roff L, Klemmack DL, Koenig HG, Baker P, Allman RM. Religiosity and mental health in southern, community-dwelling older adults. Aging & Mental Health. 2003;7:390–397. doi: 10.1080/1360786031000150667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plante TG. Integrating spirituality and psychotherapy: Ethical issues and principles to consider. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2007;63:891–902. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Procidano ME, Heller K. Measures of perceived social support from friends and from family: Three validation studies. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1983;11:1–24. doi: 10.1007/BF00898416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravindran AV, Matheson K, Griffiths J, Merali Z, Anisman H. Stress, coping, uplifts, and quality of life in subtypes of depression: a conceptual frame and emerging data. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2002;71:121–130. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(01)00389-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reker GT. Personal meaning, optimism, and choice: Existential predictors of depression in community and institutional elderly. The Gerontologist. 1997;37:709–716. doi: 10.1093/geront/37.6.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidlitz L, Abernethy AD, Duberstein PR, Evinger JS, Chang TH, Lewis BBL. Development of the spiritual transcendence index. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2002;41:439–453. [Google Scholar]

- Seybold KS, Hill PC. The role of religion and spirituality in mental and physical health. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2001;10:21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha S, Armento ME, Bush AL, Huddleston C, Zeno D, Jameson JP, Stanley MA. Pilot findings from a community-based treatment program for late-life anxiety. International Journal of Person Centered Medicine. 2012;2:400–409. [Google Scholar]

- Smith TB, McCullough ME, Poll J. Religiousness and depression: evidence for a main effect and the moderating influence of stressful life events. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:614. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.4.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley MA, Bush AL, Camp ME, Jameson JP, Phillips LL, Barber CR, Cully JA. Older adults’ preferences for religion/spirituality in treatment for anxiety and depression. Aging & Mental Health. 2011;15:334–343. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2010.519326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steger MF, Mann JR, Michels P, Cooper TC. Meaning in life, anxiety, depression, and general health among smoking cessation patients. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2009;67:353–358. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steger MF, Oishi S, Kashdan TB. Meaning in life across the life span: Levels and correlates of meaning in life from emerging adulthood to older adulthood. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2009;4:43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Bamonti PM, King DA, Duberstein PR. Does perceived burdensomeness erode meaning in life among older adults? Aging & Mental Health. 2012;16:855–860. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2012.657156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisberg HI. Statistical adjustments and uncontrolled studies. Psychological Bulletin. 1979;86:1149–1164. [Google Scholar]

- Westerhof GJ, Bohlmeijer ET, van Beljouw IJ, Pot A. Improvement in personal meaning mediates the effects of a life review intervention on depressive symptoms in a randomized controlled trial. The Gerontologist. 2010;50:541–549. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams LS, Brizendine EJ, Plue L, Bakas T, Tu W, Hendrie H, Kroenke K. Performance of the PHQ-9 as a screening tool for depression after stroke. Stroke. 2005;36:635–638. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000155688.18207.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RS, Boyle PA, Segawa E, Yu L, Begeny CT, Anagnos SE, Bennett DA. The influence of cognitive decline on well-being in old age. Psychology and Aging. 2013;28:304. doi: 10.1037/a0031196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wink P, Dillon M, Prettyman A. Religion as moderator of the sense of control-health connection: Gender differences. Journal Of Religion, Spirituality & Aging. 2007;19:21–41. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RS, Boyle PA, Segawa E, Yu L, Begeny CT, Anagnos SE, Bennett DA. The influence of cognitive decline on well-being in old age. Psychology and Aging. 2013;28:304–313. doi: 10.1037/a0031196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittink MN, Joo JH, Lewis LM, Barg FK. Losing faith and using faith: older African Americans discuss spirituality, religious activities, and depression. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2009;24:402–407. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0897-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon D, Lee E. Religiousness/Spirituality and subjective well-being among rural elderly Whites, African Americans, and Native Americans. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment. 2004;10:191–211. [Google Scholar]