SUMMARY

The role of inflammation in obesity-related pathologies is well established. We investigated the therapeutic potential of LipoxinA4 (LXA4:5(S),6(R),15(S)-trihydroxy-7E,9E,11Z,13E,-eicosatetraenoic acid) and a synthetic 15(R)-Benzo-LXA4-analogue, as interventions in a 3-month high-fat-diet [HFD; 60%fat]-induced obesity model. Obesity caused distinct pathologies, including impaired glucose-tolerance, adipose inflammation, fatty liver and chronic-kidney-disease (CKD). Lipoxins (LXs) attenuated obesity- induced CKD; reducing glomerular expansion, mesangial matrix and urinary H2O2. Furthermore, LXA4 reduced liver weight, serum alanine-aminotransferase and hepatic triglycerides. LXA4 decreased obesity-induced adipose inflammation, attenuating TNF-α and CD11c+ M1-macrophages (MΦs), while restoring CD206+ M2-MΦs and increasing Annexin-1. LXs did not affect renal or hepatic MΦs, suggesting protection occurred via attenuation of adipose inflammation. LXs restored adipose expression of autophagy markers LC3-II and p62. LX-mediated protection was demonstrable in adiponectin−/− mice, suggesting that the mechanism was adiponectin independent. In conclusion, LXs protect against obesity- induced systemic disease and these data support a novel therapeutic paradigm for treating obesity and associated pathologies.

Graphical abstract

INTRODUCTION

Obesity and the metabolic syndrome represent a global health problem, particularly due to associated co-morbidities. Obesity is an independent risk factor for systemic diseases, including diabetes, liver cirrhosis, and chronic kidney disease (CKD) (Borgeson and Sharma, 2013; Ix and Sharma, 2010). Metabolism is closely linked to the immune system and chronic, non-resolving inflammation is considered a driving force of obesity-related pathologies. Prolonged and excessive nutrient overload results in chronic activation of the immune system and associated inflammation (Donath et al., 2013).

In addition to the low-grade systemic inflammation, obesity is associated with significant adipose inflammation (Donath et al., 2013; Wen et al., 2011). The initiating processes for adipose inflammation are not entirely understood, but hypoxia due to adipose hypertrophy and a shift of macrophage (MΦ) phenotype from anti-inflammatory M2 to pro-inflammatory M1 likely play critical roles (Masoodi et al., 2014; McNelis and Olefsky, 2014). M1 MΦ produce significant amounts of pro- inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, as do adipocytes due to FFA ligation or as a result of adipocyte apoptosis. There is a growing recognition that adipose inflammation culminates in systemic disease, as it exaggerates systemic inflammation and reduces the production of the protective adipokine adiponectin (Borgeson and Sharma, 2013). Reduced adiponectin has been found to be associated with organ dysfunction in mice and humans and contributes directly to liver (Finelli and Tarantino, 2013) and kidney diseases (Sharma, 2009; Sharma et al., 2008).

Results of recent studies highlight the possibility that failed resolution of inflammation may underlie the pathogenesis of chronic inflammatory disorders, such as in metabolic syndrome and diabetes (for recent review see (Spite et al., 2014)). Immunomodulation and specifically immunoresolvents are suggested as a therapeutic strategy to overcome chronic inflammation and disease (Borgeson and Godson, 2012; Donath, 2014; Donath et al., 2013; Serhan, 2007; Serhan and Savill, 2005; Tabas and Glass, 2013). Acute inflammation is orchestrated in part by chemical autacoids in the form of peptides (cytokines, chemokines) and lipid mediators (i.e. prostaglandins and leukotrienes), which induce edema and polymorphonuclear leukocyte (PMN) recruitment to inflammatory loci. In a physiologic state, this initial phase is followed by resolution, characterized by the cessation of PMN infiltration, MΦ-mediated efferocytosis and the return to tissue homeostasis (Maderna and Godson, 2009). The resolution of inflammation is regulated by specialized pro-resolving mediators (SPMs). These include the ω3-derived protectins, resolvins and maresins as well as the ω6-derived Lipoxin A4 (LXA4; 5(S),6(R),15(S)-trihydroxy-7E,9E,11Z,13E-eicosatetraenoic acid) and Lipoxin B4 (LXB4: 5(S),14(R),15(S)- trihydroxy-6E,8Z,10E,12E- eicosatetraenoic acid). SPMs attenuate PMN recruitment and induce a pro-resolving M2 phenotype. These M2 MΦs produce more SPMs compared to M1 MΦ (Dalli and Serhan, 2012), thus further sustaining resolution, and ω3-derived SPMs also facilitate production of ω6–derived SPMs (Fredman et al., 2014). LXA4 potently attenuate acute inflammation (Maderna and Godson, 2009) and age-associated adipose inflammation ex vivo (Borgeson et al., 2012). Of note SPM have been identified in a number of human tissues and fluids including spleen, lymph nodes (Colas et al., 2014), urine (Sasaki et al., 2015) and WAT (Claria et al., 2013). Importantly, whether LXA4 actively attenuates chronic inflammation remains to be addressed.

Here, we explored the therapeutic potential of LXA4 in experimental obesity-induced systemic disease. Because native LXs are chemically labile and undergo inactivation in vivo via either dehydrogenation and/or omega-oxidation (depending on the local environment), we also evaluated the actions of a stable benzo-fused (15R)-stereoisomer analogue, referred to as benzo-LXA4 (Borgeson et al., 2011). We report that LXA4 and benzo-LXA4 attenuate obesity-induced adipose inflammation and alter the adipose M1/M2 ratio, while modulating adipose autophagy, a driver of adipose inflammation (Martinez et al., 2013; Stienstra et al., 2014). These actions resulted in adiponectin-independent protection against obesity-induced liver and kidney disease, demonstrating the therapeutic potential of LXs in obesity-induced complications.

RESULTS

LXs attenuate obesity-induced adipose inflammation and alter the M1/M2 ratio

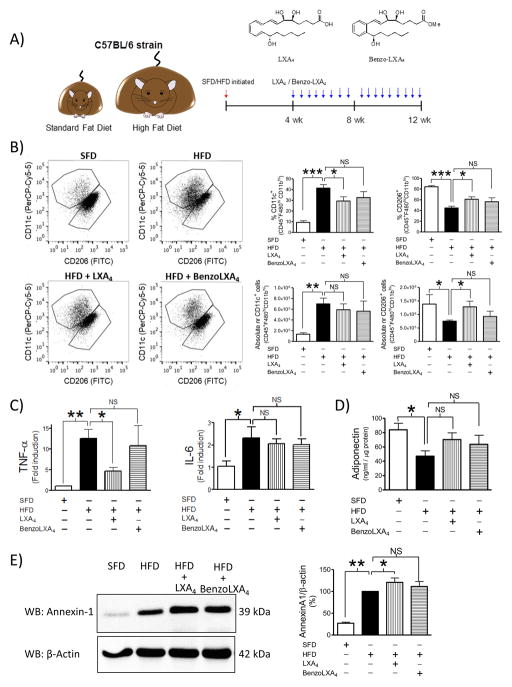

Mice were subjected to a 3 month dietary regime to induce obesity and associated liver and kidney disease (Figure 1A). Lipoxins (LXs) were provided as interventional therapeutics, introduced from weeks 5–12. Animals tolerated all treatments well. LXs did not affect HFD-induced weight gain, WAT hypertrophy or adipocyte size (Figure S1A–C). HFD was not associated with an increase in total WAT F4/80+ MΦs, as analysed both by flow cytometry and immunohistochemistry (IHC) (Figure S3). It is noteworthy that this is in contrast to other studies (Oh et al., 2012) and may possibly be due to the control diets. Rather than using vivarium chow, this study is conducted using a SFD control diet containing equal protein content and matched sucrose content compared to the HFD, which may incur important differences in MΦs infiltration. Importantly, HFD-induced obesity did cause a significant increase in M1/M2 ratio in visceral adipose tissue, as previously reported (Lumeng et al., 2007). LXs shifted the MΦs towards a resolution phenotype. Specifically, LXA4 attenuated the HFD-induced increase of the percent pro-inflammatory CD11c+ M1 MΦs (p<0.05) and LXA4 partially restored the percent anti-inflammatory CD206+ MΦs population (p<0.05) (Figure 1B). In addition, we calculated the absolute cell numbers, as the obesity-induced expansion of WAT and increase in overall leukocyte infiltration may mask percentage shifts of cellular populations. Interestingly, the effect of LXA4 on CD206+ M2 MΦs is amplified when comparing the absolute cell numbers, whereas the attenuation of CD11c+ M1 is not apparent (Figure 1B.) In addition to switching MΦ phenotype, LXA4 attenuated obesity-induced expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α (Figure 1C). WAT expression of IL-10 remained unaltered (data not shown) and IL-6 was elevated with HFD but was not reduced with treatment (Figure 1C). No significant changes were found in the CD8+ and CD4+ T-cell populations, nor in CD19+ B-cells infiltration (data not shown). However, it is important to note that we were unable to include intracellular markers in this flow cytometry panel, which prevented T-cell subset characterization, e.g. T-regs, TH1 and TH2 ratio. Visceral adipose tissue adiponectin levels were measured by ELISA and in accordance with previous reports (Neuhofer et al., 2013), the HFD led to reduced secretion of adiponectin (p<0.001). Treatment with LXs partially restored adiponectin in comparison with the control groups (SFD: 84 ± 9, HFD: 47 ± 7, HFD+LXA4: 70 ± 9, HFD+BenzoLXA4: 64 ± 12 pg/ml) (Figure 1D). However, there was no effect of LXs on the degree of WAT hypertrophy (Figure S1B–C). Annexin-A1 (AnxA1) is a glucocorticoid effector (Perretti and D'Acquisto, 2009) and AnxA1 deficiency promotes HFD- induced adiposity and insulin resistance (Akasheh et al., 2013). Our study confirms that WAT AnxA1 expression is increased in obese mice (Akasheh et al., 2013), and LXA4 treatment significantly increased AnxA1 expression (Figure 1E).

Figure 1. Lipoxins attenuated adipose inflammation and shift adipose macrophage phenotype towards resolution in vivo.

A) Schematic illustration of the protocol: C57BL/6 mice fed a Standard-Fat-Diet (SFD; 10% fat) or a High- Fat-Diet (HFD; 60% fat) for 12 wks, were treated with vehicle, LXA4 (5ng/g) or benzo-LXA4 (1.7ng/g) 3 times/wk, between wks 5–12. B) White Adipose Tissue (WAT) macrophage (MΦ) phenotype was analysed by flow cytometry. Single, live cells, pan-leukocytes were identified as inflammatory M1 MΦs (CD11c+ of CD45+F480hiCD11bhi cells) vs. anti-inflammatory M2 MΦs (CD206+ of CD45+F480hiCD11bhi cells). Representative dotplots are shown as well as quantification of both % positive cells and absolute cell numbers, n=4. C) WAT TNF-α and IL-6 expression was analysed by qPCR, n=4. D) WAT adiponectin was analysed by ELISA, n=4. E) WAT Annexin-A1 protein was determined by western blot; a representative blot is shown and densitometry quantification of n=3 experiments. Data is presented as mean ± SEM. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001; ANOVA with Bonferroni correction.

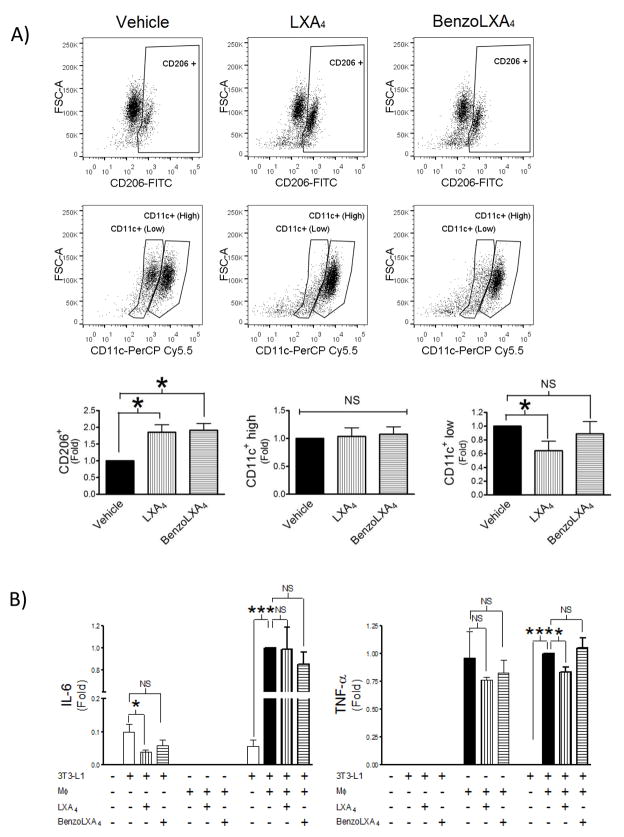

Adipose tissue is heterogeneous and comprised of numerous cell-types, where adipocytes and MΦ are the major mediators of inflammation and disease (McNelis and Olefsky, 2014). Both cell-types express the LXA4 receptor (ALX/FPR2) and are susceptible to the anti-inflammatory actions of LXA4 (Borgeson et al., 2012). To clarify the cellular targets affected by LXs in this model, we designed a similar in vitro system comprised of inflammatory MΦs and hypertrophic adipocytes, where the latter resemble the adipocyte biology seen in obesity (Yoshizaki et al., 2012). The aim was to investigate whether LXs exert their protective effects via altering of MΦ phenotype and/or adipocyte cellular function. First, we characterized the ability of LXs to shift MΦ phenotype in vitro, using the constitutively M1 activated J774 cell-line, which presents with high CD11c+ and low CD206+ expression (Figure 2). Both LXA4 and benzo-LXA4 significantly increased CD206+ expression in vitro (p<0.05) (Figure 2A). Interestingly, J774 expressed two distinct CD11c+ populations; CD11clow and CD11chigh. Similarly to the in vivo scenario, LXA4 attenuated CD11c+ expression, specifically targeting the CD11clow population (p<0.05) (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. Lipoxins attenuated adipose inflammation and shift adipose macrophage phenotype towards resolution in vitro.

J774 macrophages (MΦs), constitutively expressing an M1 phenotype, were incubated with vehicle, 1 nM LXA4 or 10 pM benzo-LXA4 for 16h. MΦ phenotype was analysed by flow cytometry and supernatants were collected. Serum-starved hypertrophic 3T3-L1 adipocytes were treated with vehicle, 1 nM LXA4 or 10 pM benzo-LXA4, or alternatively with MΦ-conditioned supernatants, as indicated. Following 24h incubation, adipocyte supernatants were collected and analysed by ELISA. A) J774 MΦ phenotype was analysed by flow cytometry and representative dotplots are shown of anti-inflammatory M2 (CD206+) MΦ and pro-inflammatory M1 (CD11c+9 ) MΦ, with respective quantification below, n=3. B) Adipocyte cytokine production was analysed by ELISA, n=3. Data are presented as mean ± SEM; n=3. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001; ANOVA with Bonferroni correction.

We subsequently stimulated hypertrophic adipocytes either directly with vehicle, LXA4 or benzo- LXA4, or alternatively with MΦ-conditioned media from J774 cells treated with either vehicle or LXs, as illustrated in Figure 2B. In accordance with previous research (Borgeson et al., 2012), LXA4 significantly attenuated adipocyte IL-6 secretion (Figure 2B). Of note, the hypertrophic adipocytes did not produce detectable levels of TNF-α or IL-10 (data not shown). In contrast, the J774 MΦs secreted high levels of TNF-α (Figure 2B), but not IL-6 nor IL-10 (data not shown). When co-culturing adipocytes with MΦ-conditioned media, LXA4 treatment attenuated MΦ-induced TNF-α production (p<0.05), although IL-6 remained unaltered (Figure 2B), similar to findings in our in vivo study (Figure 1C). Importantly, the MΦs-conditioned media appeared to increase adipose IL-6 production, which appears to have masked the basal LXA4-mediated attenuation of IL-6 secretion (Figure 2B).

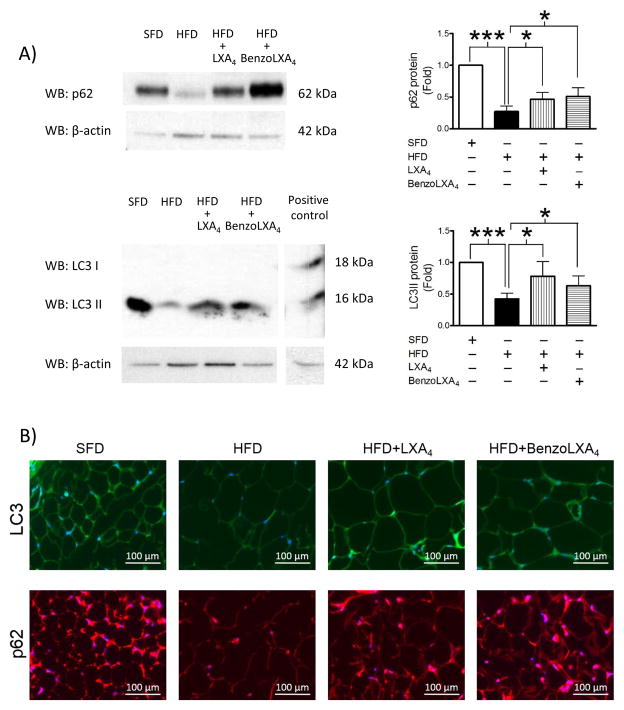

LXs modulate obesity-induced adipose autophagy

Obesity causes excessive up-regulation of WAT autophagy, which is linked to adipose stress and inflammation (Stienstra et al., 2014). We analysed two of the main markers of autophagy and autophagic flux; LC3 and p62. LC3 is an ubiquitin-like protein involved in the biogenesis of autophagosome. It is cleaved from the microtubular network to form LC3-I, which is lipidated by the Atg12-Atg5-Atg16L complex to generate LC3-II. Lipidated LC3-II is incorporated into the phagophore during its formation and guides the autophagosome. Conversion of LC3-I to LC3-II is a hallmark of autophagy induction and the LC3-II:LC3-I ratio is used to assess autophagy. We observed a reduction in the WAT LC3-II levels in obese mice, indicating reduced expression or enhanced degradation of LC3-II (Figure 3A). In agreement with previous reports of obesity-induced enhancement of autophagy in WAT, we envisage that the reduced levels of LC3-II is a consequence of enhanced lysosomal degradation due to higher autophagic flux. Similarly we observed reduced WAT p62 levels in HFD mice (Figure 3A). p62/sequestosome1 (SQSTM1) is a ubiquitin-binding scaffold protein serving as an adaptor for the recruitment of ubiquitinated protein aggregates to the autophagosome. Similar to LC3-II, p62 accumulates as autophagy is inhibited and decreases when autophagy is induced. Interestingly, LXs restored the obesity-induced reduction in the levels of LC3-II (p<0.05) and p62 (p<0.05) (Figure 3A). These findings are confirmed by immunofluorescence staining of autophagy markers p62 and LC3-II (Figure 3B), indicating that LXs down-regulated obesity-induced autophagy. To gain mechanistic insights into the mechanism for LXs’ regulation of autophagy, we performed WB analysis to determine mTOR and AMPK activity and expression. AMPK promotes autophagy by promoting Ulk1 phosphorylation at Ser317 and Ser777 and conversely mTOR inhibits autophagy by inhibiting Ulk1 by phosphorylation at Ser 757. Surprisingly, LXA4 or BenzoLXA4 did not affect mTOR and AMPK significantly (data not shown) suggesting that LX regulate autophagy independent of mTOR and AMPK. It is noteworthy that p62/SQSTM1 has been identified as a key protein promoting lipid metabolism and limiting inflammation in the recently identified “metabolically activated” MΦ (Kratz et al., 2014). Thus, LX-mediated restoration of p62 may correlate with a restoration not only of M1/M2 phenotype, but also the metabolically activated MΦ population.

Figure 3. Lipoxins modulate obesity-induced adipose autophagy.

C57BL/6 mice, fed a Standard-Fat-Diet (SFD; 10% fat) or a High-Fat-Diet (HFD; 60% fat) for 12 wks, were treated with vehicle, LXA4 (5ng/g) and benzo-LXA4 analogue (1.7ng/g) 3 times/wk, between wks 5–12. A) Representative western blots are shown of adipose autophagy markers (p62 and LC3-II protein, normalized to β-Actin). Quantification are expressed as a fold ratio to control (right panels, n=4). B) Representative immunofluorescence staining of WAT LC3-II (green) and p62 (red) is shown (n=3). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001; ANOVA with Bonferroni correction.

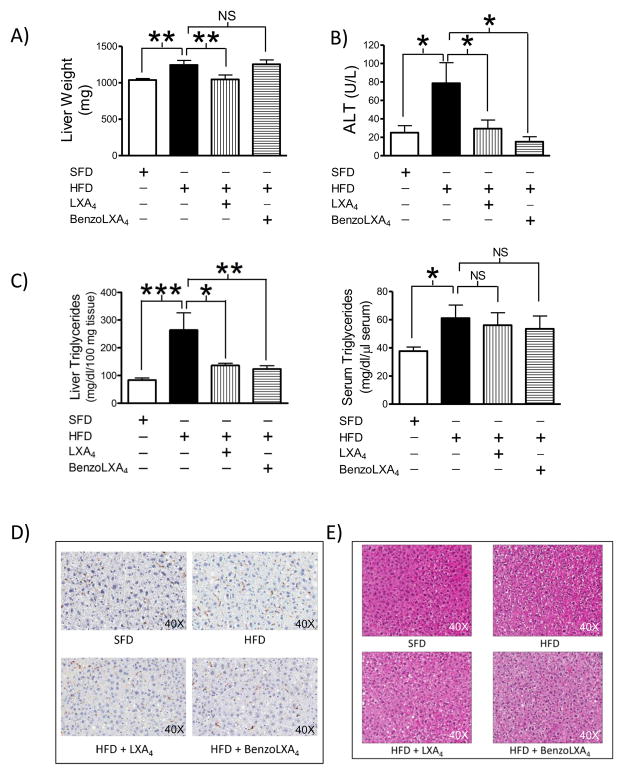

LXs attenuate obesity-induced liver disease

Obese mice presented with increased absolute liver weight (p<0.05) compared to SFD mice. Interestingly, liver expansion was attenuated by LXA4 (p<0.01) (Figure 4A), even though the total body weight remained unaltered with the LX-treatment (Figure S1A). In light of this finding, we further investigated serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels, a cardinal sign of liver injury. Obesity increased ALT by 3.15 fold (p<0.05), which was attenuated by both LXA4 and benzo-LXA4 to basal levels (p<0.05) (Figure 4B). Circulating and hepatic triglyceride (TG) levels were significantly increased during obesity. Interestingly, LXA4 (p<0.05) and benzo-LXA4 (p<0.01) attenuated liver TG deposition, although serum TGs remained unaltered (Figure 4C). HFD increased serum Cholesterol E, but no significant effects were seen with LXA4 (data not shown). Obesity did not increase hepatic MΦ infiltration, assessed through F4/80+ staining, and no obvious changes were observed with LX-treatment (Figure 4D). Furthermore, hepatic gene expression of inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-6 and anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 was assessed, but no significant differences were observed with HFD (data not shown). Finally, we assessed liver morphology using Ki67 and H&E staining; no differences in proliferation were detected (data not shown), but obesity induced some mild vacuolization, which appeared attenuated by LX-treatment (Figure 4E).

Figure 4. Lipoxins attenuate obesity-induced liver injury.

C57BL/6 mice, fed a Standard-Fat-Diet (SFD; 10% fat) or a High-Fat-Diet (HFD; 60% fat) for 12 wks, were treated with vehicle, LXA4 (5ng/g) or benzo-LXA4 (1.7ng/g) 3 times/wk, between wks 5–12. A) Liver weight was analysed at harvest, n=10. To further assess liver injury we analysed B) serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and C) hepatic and serum triglyceride content; n=4. D–E) Representative images of hepatic F4/80+ macrophages and H&E staining is shown; n=3. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001; ANOVA with Bonferroni correction.

LXs attenuate obesity-induced chronic kidney disease

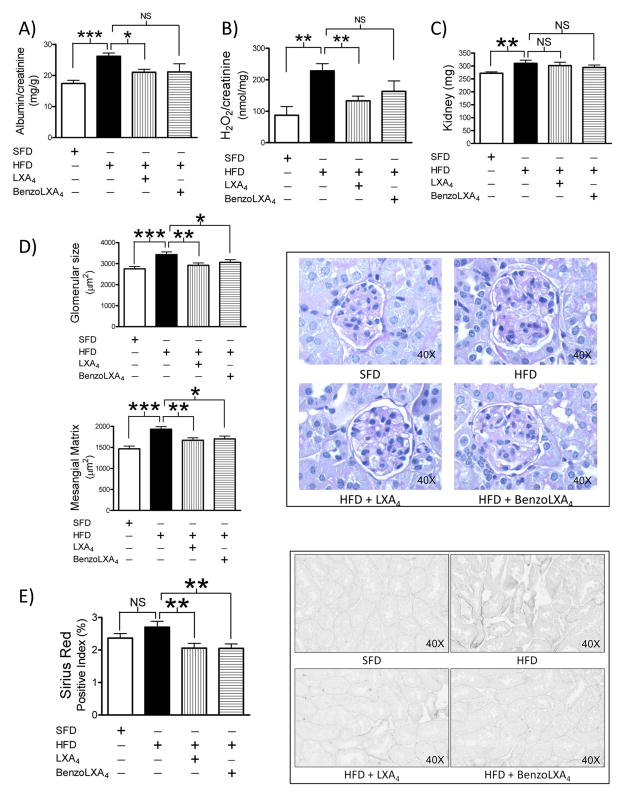

Obese mice presented with CKD, as evidenced by increased albuminuria, confirming that the model reflects obesity-induced CKD (Figure 5A). LXA4 and benzo-LXA4 significantly attenuated obesity-induced albuminuria, demonstrating protection against disease (Figure 5A). LXA4 and benzo-LXA4 attenuated obesity-induced urinary H2O2, demonstrating protection against renal injury, possibly by attenuation of free radical production (Figure 5B). HFD-induced glomerular expansion and mesangial matrix expansion were significantly attenuated by LXA4 and benzo-LXA4 (Figure 5D). To further analyse tubulointerstitial injury and fibrosis, collagen deposition was assessed using Sirius Red staining, specifically detecting newly deposited collagen. Interestingly, HFD-induced tubulointerstitial collagen deposition was significantly attenuated by LXA4 and benzo-LXA4 (Figure 5E). Renal MΦ infiltration was investigated by flow cytometry. HFD increased the ratio of CD11c+ M1 MΦ, but CD206+ M2 MΦs were only detected at minimal levels. In addition, LXs did not affect HFD-induced renal MΦ infiltration in this model, as assessed by flow cytometry analysis (data not shown).

Figure 5. Lipoxins attenuate obesity-induced chronic kidney disease.

C57BL/6 mice, fed a Standard-Fat-Diet (SFD; 10% fat) or a High-Fat-Diet (HFD; 60% fat) for 12 wks, were treated with vehicle, LXA4 (5ng/g) or benzo-LXA4 (1.7ng/g) 3 times/wk, between wks 5–12. One wk prior to harvest, 24 h urine samples were collected. Parameters of renal injury, including A) albuminuria and B) urine hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)/creatinine and C) renal hypertrophy were assessed, n=10. D) Glomerular expansion and matrix deposition were assessed by Periodic acid-Schiff and E) tubulointerstitial collagen by Sirius Red, n=5. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001; ANOVA with Bonferroni correction.

LX-mediated protection is independent of adiponectin

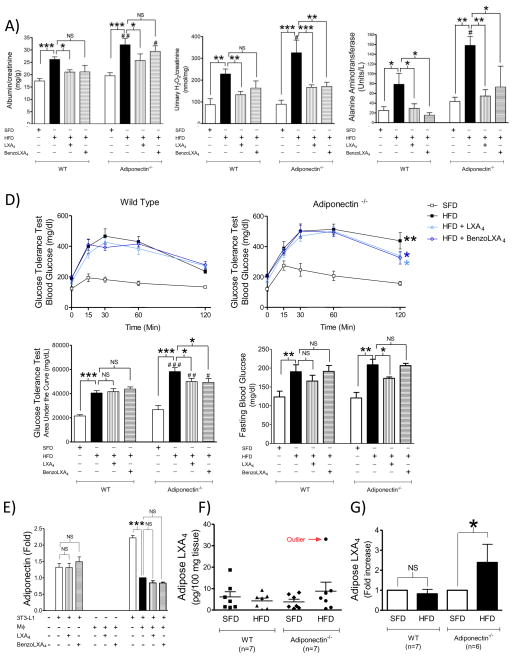

Obesity-induced impairment of the adiponectin/AMPK pathway causes both liver and kidney disease (Polyzos et al., 2010; Sharma, 2009; Sharma et al., 2008). We noted a trend towards increased WAT adiponectin levels in LX-treated mice (Figure 1D), and thus we evaluated whether the LX-mediated hepatic and reno-protective effects were mediated via the adiponectin axis, by comparing the HFD-induced pathology observed in the C57BL/6J wild type (WT) (Figure 5) versus adiponectin−/− knock out (KO) mice (Figure 6). The adiponectin−/− mice were more susceptible to obesity-induced kidney and liver disease, as indicated by increased albuminuria (p<0.01: ##), urine H2O2 (p<0.05: #) and serum ALT (p<0.05: #) (Figure 6 A–C). LXs also displayed reno-protective actions in adiponectin−/− mice, as demonstrated by a reduction in albuminuria (p<0.05:*), and both LXA4 (p<0.001:***) and benzo-LXA4 (p<0.01:**) attenuated HFD-induced urine H2O2 in the mice lacking the adiponectin gene (Figure 6 A–B). Similarly, LXs significantly reversed the obesity-induced increase of serum ALT in the adiponectin−/− mice (Figure 6C). These finding demonstrate unique properties of LXA4 compared to other ω3-derived SPMs, which regulate obesity via direct action on adiponectin (Claria et al., 2012; Rius et al., 2014).

Figure 6. Lipoxin-mediated protection of obesity-induced pathology is independent of adiponectin.

C57BL/6 or adiponectin−/− mice, fed a Standard-Fat-Diet (SFD; 10% fat) or a High-Fat-Diet (HFD; 60% fat) for 12 wks, were treated with vehicle, LXA4 (5ng/g) or benzo-LXA4 (1.7ng/g) 3 times/wk, between wks 5– 12. Parameters of renal injury, including A) albuminuria and B) urine hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)/creatinine were analysed, n=10. In figure C) serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) was analysed, n=4. In figure D) glucose tolerance was assessed over 120 min one wk prior to harvest. The area under curve (AUC) was calculated for respective group and used for statistical analysis, as well as basal fasting glucose, n=10. E) Hypertrophic adipocytes were incubated with vehicle, LXA4 (1nM) or benzo-LXA4 (10 pM) for 24h. Alternatively, adipocytes were incubated for 24h with supernatants from MΦ pretreated with vehicle, LXA4 (1nM) or benzo-LXA4 (10 pM). Following respective treatment, the adipocyte supernatants were collected and cytokine production was analysed by ELISA, n=3. In Figure F) the endogenous adipose LXA4 production was assessed by LC-MS-MS in vehicle-treated SFD and HFD Wild Type (WT) and adiponectin−/− mice (n=7). In Figure G), the HFD-induced fold increase of endogenous LXA4 production was calculated, excluding the outlier identified in Figure F. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P< 0.001. Statistically significant differences between respective condition in the WT versus Adiponectin−/− strain is indicated as # P<0.05, ##P<0.01, ### P<0.001; ANOVA with Bonferroni correction.

As anticipated, obese animals displayed decreased sensitivity to insulin-stimulated glucose uptake. LXA4 and benzo-LXA4 did not rescue obesity-induced impairment of glucose-tolerance in C57BL/6J mice, suggesting that protection against liver disease and CKD occurs independent of rescued insulin-sensitivity (Figure 6D, WT data). Adiponectin−/− mice displayed exaggerated impairment of glucose tolerance compared to respective WT control (p<0.001:###) (Figure 6D). LXs restored HFD-induced impairment of glucose uptake and LXA4 attenuated fasting blood glucose in the KO strain (Figure 6D). To investigate our findings further in vitro, hypertrophic adipocytes were used as an experimental model of obesity (Yoshizaki et al., 2012). As described, adipocytes were incubated with vehicle, LXA4, benzo-LXA4, or alternatively with MΦ-conditioned media from J774 cells treated with either vehicle or LXs. The LXs did not attenuate basal adiponectin production in hypertrophic adipocytes (Figure 6E), although LXA4 attenuates other cellular responses in this in vitro system, e.g. basal IL-6 production (Figure 2B). LXA4 did not rescue MΦ-induced attenuation of adipose adiponectin production (Figure 6E), although LXA4 did attenuated MΦ-induced TNF-α in this experimental setup (Figure 2B).

Finally, we investigated endogenous LXA4 production in SFD and HFD treated WT and adiponectin−/− mice (Figure 6F). Using LM-metabololipidomics (Figure S4), endogenous LXA4 was identified and quantified at biologically relevant amounts (5.7 ± 1.1 pg/100mg tissue) (Krishnamoorthy et al., 2010), which is comparable to levels of eicosanoids reported by others e.g. LTB4 (0.7 pg/100 mg tissue) (Li et al., 2015). We also identified mediators from the DHA, EPA and AA bioactive metabolomes including resolvin (Rv) D1 (4.2 ± 1.0 pg/100mg tissues), RvD5 (1.6 ± 0.4 pg/100mg tissues) and Maresin 1 (1.9 ± 0.3 pg/100mg tissues). These were not significantly altered in either condition, although a trend towards reduced LXB4 levels were observed in obese animals, which will be interesting to investigate further in future studies. Of note, HFD administration reduced LXA4 levels in adipose tissue (WT: SFD 6.1 ± 2.4 vs HFD 4.3 ± 1.3 pg/100mg tissue) (Figure 6F). We also found a reduction in LXA4 levels between lean WT and adiponectin−/− mice, although in both cases the difference did not reach statistical significance. However, the adiponectin−/− mice displayed a trend of increased endogenous LXA4 production following HFD treatment (KO: SFD 3.8 ± 1.2 vs HFD 8.8 ± 4.2 pg/100mg tissue) (Figure 6F). When comparing the fold changes between lean and obese animals in respective mouse strain, it became apparent that obesity significantly increased endogenous LXA4 production in the adiponectin−/− group (Figure 6G, p<0.05).

DISCUSSION

Obesity is an independent risk factor for serious pathological conditions, including diabetes, liver disease and CKD. Adipose inflammation appears to be the common denominator of obesity-related pathologies (Donath and Shoelson, 2011; McNelis and Olefsky, 2014). Promoting the resolution of adipose inflammation is therefore a potential therapeutic approach that could alleviate obesity-associated organ dysfunction (Borgeson and Godson, 2012; Claria et al., 2012; Donath, 2014; Donath et al., 2013; Spite et al., 2014; Tabas and Glass, 2013). The results presented here demonstrate that LXA4 attenuates obesity8 associated adipose inflammation and thereby alleviates liver and kidney diseases associated with obesity.

LXs rescued HFD-induced kidney and liver disease, and the key mechanism of action appeared to be the attenuation of visceral WAT inflammation. In contrast to other studies (Oh et al., 2012) we do not report an increase in total WAT F4/80+ MΦs in HFD versus SFD. Importantly we observed an obesity-induced shift of the MΦ phenotype from M1 (CD11c+) to M2 (CD206+13 ). The LXA4-induced shift in WAT MΦ phenotype correlated with other attributes of resolution, such as attenuation of the inflammatory cytokine TNF-α. These data may be compared with other in vivo models, where LXA4 promotes an M1- to-M2 MΦ polarization in a mouse air-pouch model of inflammation (Vasconcelos et al., 2015). Indeed, LXA4 may attenuate the pro-inflammatory M1 MΦ phenotype by modulating IκBα degradation, NF-κB translocation and IKK expression, resulting in supressed NF-κB activation (Huang et al., 2014; Kure et al., 2010). In contrast, LXA4 may promote an M2a and M2c MΦ phenotype by modulating STAT3 (Li et al., 2011) and prolonging the MΦ life-span by inhibiting LPS-induced apoptosis via PI3K/Akt and ERK/Nrf-2 pathways, (Prieto et al., 2010). Furthermore, our finding that LXA4 promotes an WAT M1-to-M2 MΦ polarization correlates with earlier reports that depletion of CD11c+ cells results in rapid normalization of obesity-induced insulin sensitivity, paralleled by a decrease in adipose and systemic inflammation (Patsouris et al., 2008). Similarly, ω3-derived SPMs (e.g. resolvins, protectins and maresins) reduce insulin resistance, increase adiponectin secretion and modulate adipose MΦ functions towards a ‘pro-resolution phenotype’ in genetic models of obesity (Gonzalez-Periz and Claria, 2010; Gonzalez-Periz et al., 2009; Hellmann et al., 2011; Neuhofer et al., 2013; Ost et al., 2010).

It is important to recognize that in addition to their well-established actions on leukocytes (Serhan, 2007), LXs affect numerous cell types, including adipocytes (Borgeson et al., 2012). It is therefore reasonable to ask whether LXA4–mediated attenuation of WAT inflammation occurred through modulation of the MΦ phenotype and/or via direct manipulation of the adipocyte cell function. LXA4 restores TNF-α induced impairment of insulin-signalling in normal 3T3-L1 adipocytes (Borgeson et al., 2012). In this study, we used a similar experimental setup, composed of murine MΦ and hypertrophic adipocytes, the latter in order to better mimic obesity (Yoshizaki et al., 2012). The results confirmed that LXA4 may reduce inflammation by affecting both MΦs and adipocytes. We confirmed in vitro that LXA4 shifts the MΦ phenotype from M1 to M2, and that this translates to an attenuation of MΦ TNF-α production. LXA4 has a direct effect on hypertrophic adipocyte IL-6 secretion; although this effect may be overwhelmed by the strong inflammatory stimuli from M1 MΦs. Interestingly, this in vitro system correlated with our in vivo data, where the LXA4 primarily affected TNF-α gene expression in adipocytes.

The LXA4 receptor is expressed in the adipose ‘target tissue’. The murine homologues of ALX/FPR2 are Fpr2/Fpr-rs1 and Fpr3/Fpr-rs2, and we have previously demonstrated that Fpr-rs2/FPR3 is expressed in both the murine adipocytes and macrophages (Borgeson et al., 2012). Furthermore, Claria et al report that expression of the LXA4 receptor is present in mouse WAT and that this expression is sustained in obese mice (Claria et al., 2012). Interestingly, they also show that the human LXA4 receptors ALX/FPR2 and GPR32 are identified in human adipose tissue (Claria et al., 2012).

In addition to attenuating WAT inflammation, LXs modulated HFD-induced adipose autophagy. The general consensus is that chronic obesity causes excessive activation of autophagy in the adipose tissue, which correlates with increased cell-death and adipose inflammation (Martinez et al., 2013; Stienstra et al., 2014). In accordance with previous studies (Cummins et al., 2014; Stienstra et al., 2014), our data show that HFD is associated with enhanced levels of autophagy in WAT, as evident from decreased detectable p62 and LC3-II, suggesting high autophagy flux and enhanced degradation of the proteins. Interestingly, LXs restored the HFD-induced decrease in p62 and LC3-II protein to the levels observed in lean mice. Importantly, the LX-mediated attenuation of autophagy was independent of mTOR and AMPK activity and we hypothesize that LXs may regulate autophagy by modulating the autophagic flux via regulation of autophagosome maturation (fusion of autophagosomes with lysosome). However, future studies are needed to investigate the detailed molecular mechanisms involved in LX-mediated regulation of autophagy and its significance in LX-mediated attenuation of adipose inflammation. Interestingly, p62/SQSTM1 has been identified as one of the key proteins that promote lipid metabolism and limit inflammation in the recently identified “metabolically activated” MΦ (mMe-MΦ) (Kratz et al., 2014). Activation of p62 results in inhibition of NF-κB and thus limits inflammation. It is therefore particularly noteworthy that LXs restore obesity-induced attenuation of p62, as it may correlate with a restoration not only of M1/M2 phenotype, but also an anti-inflammatory mMe-MΦ population. This will be the focus of future work.

Obesity is an independent risk factor for kidney disease, even when excluding variables such as diabetes and hypertension (Borgeson and Sharma, 2013). Additionally, obesity accelerates the progression of pre-existing kidney disease (Mathew et al., 2011). We have previously shown that LXA4 and benzo-LXA4 attenuate experimental tubulointerstitial fibrosis induced by unilateral ureteric obstruction (Borgeson et al., 2011; Brennan et al., 2013). LXs have also been shown to be protective in acute renal injury, attenuating the inflammatory response to ischaemia reperfusion injury (Borgeson and Godson, 2012; Leonard et al., 2002). However, the potential of using LXA4 in models of obesity- induced CKD has not previously been investigated. The present study showed that both LXA4 and benzo- LXA4 attenuated obesity-induced CKD, as evidenced by reduced glomerular expansion and mesangial matrix deposition. The LXs also attenuated the mild tubulointerstitial fibrosis observed in this experimental system. LXA4 rescued albuminuria, a cardinal sign of kidney disease, and significantly lowered HFD-induced urine H2O2 levels, which was used as a marker of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and renal injury. Interestingly, renal leukocyte infiltration was not significantly affected by LXs in this disease model, suggesting that the protection was not due to a direct effect on the renal inflammatory milieu.

Obesity-induced non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is also becoming a major health problem. NAFLD ranges from steatosis (accumulation of hepatic triglycerides) to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH or steatohepatitis, steatosis with an inflammatory component). Hepatic steatosis is associated with enhanced hepatic susceptibility to progress into irreversible forms of liver disease (Spite et al., 2014). Other SPMs (ResolvinE1, ProtectinD1 and D-series resolvins) attenuate obesity-induced liver disease (Claria et al., 2012; Gonzalez-Periz et al., 2009). LXA4 enhances organ function in murine liver transplantation, attenuating serum ALT and inducing a pro-resolving shift in cytokine production, decreasing IFN-γ while increasing IL-10 (Levy et al., 2011; Liao et al., 2013). Recent data highlight a protective effect of LXs and other arachidonate-derived mediators in cardiovascular disease associated with increased reverse cholesterol transfer and lower plasma LDL (Demetz et al., 2014). In our model, obesity caused mild liver injury, as apparent by increased serum ALT, liver weight and triglyceride accumulation. Interestingly, LXs attenuated HFD-induced liver injury, as both LXA4 and benzo-LXA4 attenuated serum ALT and hepatic triglyceride deposition to baseline levels. LXA4 significantly attenuated liver weight, which is a particularly noteworthy finding because the total body weight was not affected. The attenuation of hepatic triglyceride deposition may correlate with the restoration of hepatic expansion. However, this may not be the sole explanation, as benzoLXA4–induced attenuation of hepatic triglycerides did not translate to altered organ weight. LXA4-induced reduction of hepatic edema may be an additional explanation for the significant effect mediated by LXA4 on attenuation of liver weight. Collectively, our findings suggest that LX-mediated reduction of hepatic steatosis may make the liver more resistant against additional insults. Previous research demonstrates that an accumulation of WAT MΦ and resulting adipose inflammation correlates with liver pathology (Cancello et al., 2006; Ix and Sharma, 2010; Tordjman et al., 2009). We thus propose that the LX10 mediated restoration of the WAT M1/M2 ratio is a key mechanism of action in the reduction of liver pathology. In line with this argument, our data reveals that LXA4 increases WAT levels of the pro-resolving AnxA1, which is protective of NASH in mice (Locatelli et al., 2014). Specifically, this interesting study demonstrates that WAT MΦ-derived AnxA1 plays a functional role in modulating hepatic inflammation and fibrogenesis during NASH progression. The LXA4-mediated increase in AnxA1 is thus likely a key mechanism of action in the observed attenuation of liver injury.

In addition to LXA4, we evaluated the therapeutic potential of a (1R)-stereoisomer analogue (referred to as benzo-LXA4) in these experiments. This analog differs structurally from the benzo-analog o-(9,12)-benzo-ω6-epi-LXA4 described by Sun et al (Sun et al., 2009) and is protective in acute inflammation and tubulointerstial fibrosis (Borgeson et al., 2011; O'Sullivan et al., 2007). It should be noted that the benzo-LXA4 analogue exerted similar actions as LXA4, although the native compound proved more effective in the present study. Thus, the analogue provides us with valuable insights into the effect on biological activity of modifying the triene unit of native LXA4 to a metabolically more stable benzene ring as well as the importance of (R)-stereochemistry at the benzylic carbinol centre, which will aid future analogue design.

The adiponectin/AMPK axis is implicated in obesity-induced liver and kidney pathology (Mathew et al., 2011; Sharma et al., 2008). Previous work demonstrates that LXA4 increases adiponectin in adipose explants (Claria et al., 2012), is present in human adipose tissue (Claria et al., 2013) and urine (Sasaki et al., 2015) and herein we observed a trend towards increased WAT adiponectin production in LX-treated mice (Figure 1D). Therefore, we hypothesized that LXs may mediate protection in our obesity model via induction of adiponectin in WAT. To explore this possible mechanism of action, we carried out the experimental design in both WT and adiponectin−/− mice. The assumption was that if our hypothesis was correct, the LX-mediated protection would not be observed in the KO strain. The LX-mediated restoration of albuminuria was evident in both WT and adiponectin−/− mice, although LXs displayed increased ability to attenuate HFD-induced urine H2O2 production in the KO strain. Furthermore, the in vitro data show that neither LXA4 nor benzo-LXA4 induced adiponectin production in hypertrophic 3T3- L1 adipocytes. In addition, the LXs did not rescue MΦ-induced attenuation of adiponectin production in the adipocytes. Collectively, the data thus shows that LX-mediated attenuation of obesity-induced disease is adiponectin independent in this model of HFD-induced renal and liver injury. In relation to our initial observation that LXs caused a trend towards increased WAT adiponectin production, this may simply be due to an improved general health of these mice, rather than being a direct mediator of LX’s beneficial effects.

LXs did not mediate protection via enhancing glucose tolerance in the WT animals, indicating that the mechanism of action did not involve improved pancreatic insulin function. However, both LXA4 and benzo-LXA4 reduced GTT 120 min post-injection (p<0.05) in the KO mice, although the animals still remained significantly more insulin resistant compared to lean mice. LXA4 also reduced fasting glucose in adiponectin−/− strain, suggesting that LXA4 may exert some modulation of insulin resistance.

As the LXA4-mediated protection appeared enhanced in the KO strain, we measured endogenous LXA4 production in the adipose tissue of the SFD and HFD treated groups. Obese adiponectin−/− mice expressed significantly more endogenous LXA4, when challenged with HFD. Thus, it is plausible that in conditions of adiponectin deficiency there is a compensatory response to further increase LX production due to enhanced inflammation and the other arachidonic acid (AA)-derived products. Further exogenous administration of LXs may be necessary to restore insulin sensitivity. The regulation of LXs by adiponectin is worthy of future studies. Whether LXs may have an effect to improve insulin sensitivity and lower blood glucose in other models of diabetes remains to be tested.

In conclusion, these results indicate that LXs have therapeutic potential in obesity-induced pathologies, such as liver disease and CKD. LXA4 likely mediates protection via reducing adipose inflammation and modulation of WAT MΦ phenotype. Interestingly, LXs reversed HFD-induced adipose autophagy, which has been linked to obesity-induced disease. LX-mediated protection was independent of systemic adiposity and glucose tolerance. Moreover, the LX-mediated actions were adiponectin independent in this system. Collectively, these results demonstrate the potential of using SPMs, such as LXA4 and LX-stable analogues, to protect from obesity-induced pathologies.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Detailed protocols are described in Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

In vivo obesity study

C57BL/6J (n=10) and C57BL/6J adiponectin−/− mice (n=7) (Jackson), were fed a Standard-Fat-Diet (SFD; 10% fat) or a High-Fat-Diet (HFD; 60% fat) for 12 wks. Vehicle (1% ethanol), LXA4 (5ng/g) or benzo-LXA4 (1.7ng/g) were given as 100 μl intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections 3 times/wk, between wks 5–12. Vehicle does not increase baseline WAT inflammation (Qin et al., 2014). LXA4 (5(S)-6(R)-15(S)-trihydroxy-7,9,13- trans-11-cis-eicosatetraenoic acid) was bought from EMD Millipore and (1R)-benzo-LXA4 synthesized by Prof Guiry (O'Sullivan et al., 2007). Insulin-stimulated glucose tolerance, micro-albuminuria and urinary H2O2 were assessed one wk prior to sacrifice and organs were harvested under isoflurane sedation.

Flow cytometry analyses

Leukocytes isolated from homogenized WAT and kidneys were stained and characterized by flow cytometry as pan-MΦ (F4/80PEhiCD11bAPChi ), M1 MΦs (CD11c+PerCPcy5.5 of CD45+F480hiCD11bhi cells) or M2 MΦs (CD206+FITC of CD45+F480hiCD11bhi cells) (Figure S2). B-cells (CD19+) and T-cells (CD4+ vs. CD8a+15 ) were also identified.

Lipid mediator lipidomics

Endogenous LXA4 production was determined in snap frozen WAT from SFD and HFD animals (n=7), using targeted LC-MS-MS based lipidomics (Colas et al., 2014). One outlier was identified by the ROUT method in the adiponectin−/− HFD group (Figure 6F) and excluded in the paired ‘Fold increase’ analyses (Figure 6G).

Immunohistochemistry

Renal glomerular expansion and matrix deposition were assessed by Periodic Acid-Schiff and tubulointerstitial fibrosis by Sirius Red staining. Livers and WAT were stained for H&E, ki67 and F4/80+ MΦs. WAT p62 and LC3-II proteins were detected by immunofluorescence. Staining was quantified by color deconvolution algorithms (Aperio Software).

Protein analyses

WAT protein (40 μg) was immunoblotted on a 16% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred onto 0.2 μm PVDF membranes. Proteins identified as LC3, p62, pmTOR, mTOR, pAMPK, AMPK, Annexin-1 and β-Actin were quantified using Adobe Photoshop.

Adipose and liver mRNA expression

RNA was isolated from tissues homogenized in TRIzol. Relative TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-10 mRNA expression was analysed by the ΔΔCT method using TaqMan primer/probe (Life Technologies) and normalized to 18S.

Liver function analysis

Liver tissue (100 mg) suspended in 3M KOH (in 65% EtOH) was incubated at 70 °C for 1 h, to activate digestion, and diluted 1:3 with 2M Tris-HCl pH 7.5. Subsequently, ALT, Triglycerides and Cholesterol E was analysed in both liver extracts and serum.

In vitro experiments

J774 MΦs were incubated with vehicle (0.1 % ethanol), LXA4 (1 nM) or benzo-LXA4 (10 pM) for 16h. Supernatants were collected and MΦ phenotype determined by flow cytometry as M1 (CD11+19 ) vs M2 (CD206+20 ). Serum-starved hypertrophic 3T3-L1 adipocytes were treated with vehicle, LXA4 (1 nM) or benzo-LXA4 (10 pM) for 24h. Alternatively, adipocytes were treated with the MΦ-conditioned supernatants for 24 h. Adipocyte supernatant TNF-α, IL-6 and adiponectin levels were assessed by ELISA.

Statistical analyses

The in vivo study was calculated to an Experimental Power of 80%. Assuming Gaussian distribution, analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni correction was used to assess statistical significance (p<0.05). Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Lipoxins attenuated high-fat-diet induced liver and kidney disease.

LXA4 attenuated adipose inflammation; promoting a macrophage M1-to-M2 switch.

LXA4 restored obesity-induced attenuation of autophagy markers LC3II and p62.

LXA4-mediated protection was adiponectin-independent, but restored Annexin-A1.

Acknowledgments

Scientific input is acknowledged from Ida Bergstrom (Linkoping University), Ville Wallenius (University of Gothenburg), Bjorn Scheffler and Sabine Normann (University of Bonn), Dina Sirypangno (Flow Core, VA), Andrew Gaffney (DCRC, UCD) and Lexi Gautier, Samantha Chavez, Madison Clark, Carl Scherif (Volunteers, UCSD). AT is supported by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research, Germany (BMBF, VIP initiative, FKZ 03V0785). PG is supported by the Higher Education Authority’s Programme for Research in Third-Level Institutions (PRTLI Cycle 4) and by Science Foundation Ireland (11/PI/1206). RAC, JD, CNS and LC-MS-MS profiling were supported by National Institutes of Health Grant P01 GM095467 (CNS). CG is supported by Science Foundation Ireland (06/IN.1/B114) and a pilot grant from The NIH Diabetes Complications Consortium. KS is supported by VA Merit Grant (5I01 BX000277) and an NIH DP3 award (DK094352-01). EB is a supported by a Marie Curie International Outgoing Fellowship.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

EB, KS and CG designed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. EB executed all experiments presented, except the LC-MS-MS based lipidomics. AJ and YSL assisted in optimization of flow cytometry analysis. AT and GS assisted in optimization of autophagy analysis. SA and PG designed and synthesized the benzo-LXA4 analogue. RAC, JD and CNS carried out LC-MS-MS profiling. All authors actively reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Akasheh RT, Pini M, Pang J, Fantuzzi G. Increased adiposity in annexin A1-deficient mice. PloS one. 2013;8:e82608. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgeson E, Docherty NG, Murphy M, Rodgers K, Ryan A, O'Sullivan TP, Guiry PJ, Goldschmeding R, Higgins DF, Godson C. Lipoxin A(4) and benzo-lipoxin A(4) attenuate experimental renal fibrosis. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2011;25:2967–2979. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-185017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgeson E, Godson C. Resolution of inflammation: therapeutic potential of pro-resolving lipids in type 2 diabetes mellitus and associated renal complications. Frontiers in immunology. 2012;3:318. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgeson E, McGillicuddy FC, Harford KA, Corrigan N, Higgins DF, Maderna P, Roche HM, Godson C. Lipoxin A4 attenuates adipose inflammation. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2012;26:4287–4294. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-208249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgeson E, Sharma K. Obesity, immunomodulation and chronic kidney disease. Current opinion in pharmacology. 2013;13:618–624. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2013.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan EP, Nolan KA, Borgeson E, Gough OS, McEvoy CM, Docherty NG, Higgins DF, Murphy M, Sadlier DM, Ali-Shah ST, Guiry PJ, Savage DA, Maxwell AP, Martin F, Godson C. Lipoxins attenuate renal fibrosis by inducing let-7c and suppressing TGFbetaR1. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2013;24:627–637. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012060550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancello R, Tordjman J, Poitou C, Guilhem G, Bouillot JL, Hugol D, Coussieu C, Basdevant A, Bar Hen A, Bedossa P, Guerre-Millo M, Clement K. Increased infiltration of macrophages in omental adipose tissue is associated with marked hepatic lesions in morbid human obesity. Diabetes. 2006;55:1554–1561. doi: 10.2337/db06-0133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claria J, Dalli J, Yacoubian S, Gao F, Serhan CN. Resolvin D1 and resolvin D2 govern local inflammatory tone in obese fat. J Immunol. 2012;189:2597–2605. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claria J, Nguyen BT, Madenci AL, Ozaki CK, Serhan CN. Diversity of lipid mediators in human adipose tissue depots. American journal of physiology. Cell physiology. 2013;304:C1141–1149. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00351.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colas RA, Shinohara M, Dalli J, Chiang N, Serhan CN. Identification and signature profiles for pro-resolving and inflammatory lipid mediators in human tissue. American journal of physiology. Cell physiology. 2014;307:C39–54. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00024.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins TD, Holden CR, Sansbury BE, Gibb AA, Shah J, Zafar N, Tang Y, Hellmann J, Rai SN, Spite M, Bhatnagar A, Hill BG. Metabolic remodeling of white adipose tissue in obesity. American journal of physiology. Endocrinology and metabolism. 2014;307:E262–277. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00271.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalli J, Serhan CN. Specific lipid mediator signatures of human phagocytes: microparticles stimulate macrophage efferocytosis and pro-resolving mediators. Blood. 2012;120:e60–72. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-04-423525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demetz E, Schroll A, Auer K, Heim C, Patsch Josef R, Eller P, Theurl M, Theurl I, Theurl M, Seifert M, Lener D, Stanzl U, Haschka D, Asshoff M, Dichtl S, Nairz M, Huber E, Stadlinger M, Moschen Alexander R, Li X, Pallweber P, Scharnagl H, Stojakovic T, Marz W, Kleber Marcus E, Garlaschelli K, Uboldi P, Catapano Alberico L, Stellaard F, Rudling M, Kuba K, Imai Y, Arita M, Schuetz John D, Pramstaller Peter P, Tietge Uwe JF, Trauner M, Norata Giuseppe D, Claudel T, Hicks Andrew A, Weiss G, Tancevski I. The Arachidonic Acid Metabolome Serves as a Conserved Regulator of Cholesterol Metabolism. Cell metabolism. 2014;20:787–798. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donath MY. Targeting inflammation in the treatment of type 2 diabetes: time to start. Nature reviews Drug discovery. 2014;13:465–476. doi: 10.1038/nrd4275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donath MY, Dalmas E, Sauter NS, Boni-Schnetzler M. Inflammation in obesity and diabetes: islet dysfunction and therapeutic opportunity. Cell metabolism. 2013;17:860–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donath MY, Shoelson SE. Type 2 diabetes as an inflammatory disease. Nature reviews. 2011;11:98–107. doi: 10.1038/nri2925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finelli C, Tarantino G. What is the role of adiponectin in obesity related non-alcoholic fatty liver disease? World journal of gastroenterology : WJG. 2013;19:802–812. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i6.802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredman G, Ozcan L, Spolitu S, Hellmann J, Spite M, Backs J, Tabas I. Resolvin D1 limits 5-lipoxygenase nuclear localization and leukotriene B4 synthesis by inhibiting a calcium-activated kinase pathway. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111:14530–14535. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1410851111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Periz A, Claria J. Resolution of adipose tissue inflammation. TheScientificWorldJournal. 2010;10:832–856. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2010.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Periz A, Horrillo R, Ferre N, Gronert K, Dong B, Moran-Salvador E, Titos E, Martinez-Clemente M, Lopez-Parra M, Arroyo V, Claria J. Obesity-induced insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis are alleviated by omega-3 fatty acids: a role for resolvins and protectins. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2009;23:1946–1957. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-125674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellmann J, Tang Y, Kosuri M, Bhatnagar A, Spite M. Resolvin D1 decreases adipose tissue macrophage accumulation and improves insulin sensitivity in obese-diabetic mice. Faseb J. 2011 doi: 10.1096/fj.10-178657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YH, Wang HM, Cai ZY, Xu FY, Zhou XY. Lipoxin A4 inhibits NF-kappaB activation and cell cycle progression in RAW264.7 cells. Inflammation. 2014;37:1084–1090. doi: 10.1007/s10753-014-9832-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ix JH, Sharma K. Mechanisms linking obesity, chronic kidney disease, and fatty liver disease: the roles of fetuin-A, adiponectin, and AMPK. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2010;21:406–412. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009080820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kratz M, Coats BR, Hisert KB, Hagman D, Mutskov V, Peris E, Schoenfelt KQ, Kuzma JN, Larson I, Billing PS, Landerholm RW, Crouthamel M, Gozal D, Hwang S, Singh PK, Becker L. Metabolic dysfunction drives a mechanistically distinct proinflammatory phenotype in adipose tissue macrophages. Cell metabolism. 2014;20:614–625. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamoorthy S, Recchiuti A, Chiang N, Yacoubian S, Lee CH, Yang R, Petasis NA, Serhan CN. Resolvin D1 binds human phagocytes with evidence for proresolving receptors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:1660–1665. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907342107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kure I, Nishiumi S, Nishitani Y, Tanoue T, Ishida T, Mizuno M, Fujita T, Kutsumi H, Arita M, Azuma T, Yoshida M. Lipoxin A(4) reduces lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation in macrophages and intestinal epithelial cells through inhibition of nuclear factor-kappaB activation. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 2010;332:541–548. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.159046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard MO, Hannan K, Burne MJ, Lappin DW, Doran P, Coleman P, Stenson C, Taylor CT, Daniels F, Godson C, Petasis NA, Rabb H, Brady HR. 15-Epi-16-(para-fluorophenoxy)- lipoxin A(4)-methyl ester, a synthetic analogue of 15-epi-lipoxin A(4), is protective in experimental ischemic acute renal failure. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2002;13:1657–1662. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000015795.74094.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy BD, Zhang QY, Bonnans C, Primo V, Reilly JJ, Perkins DL, Liang Y, Amin Arnaout M, Nikolic B, Serhan CN. The endogenous pro-resolving mediators lipoxin A4 and resolvin E1 preserve organ function in allograft rejection. Prostaglandins, leukotrienes, and essential fatty acids. 2011;84:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P, Oh da Y, Bandyopadhyay G, Lagakos WS, Talukdar S, Osborn O, Johnson A, Chung H, Mayoral R, Maris M, Ofrecio JM, Taguchi S, Lu M, Olefsky JM. LTB4 promotes insulin resistance in obese mice by acting on macrophages, hepatocytes and myocytes. Nature medicine. 2015;21:239–247. doi: 10.1038/nm.3800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Cai L, Wang H, Wu P, Gu W, Chen Y, Hao H, Tang K, Yi P, Liu M, Miao S, Ye D. Pleiotropic regulation of macrophage polarization and tumorigenesis by formyl peptide receptor-2. Oncogene. 2011;30:3887–3899. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao W, Zeng F, Kang K, Qi Y, Yao L, Yang H, Ling L, Wu N, Wu D. Lipoxin a4 attenuates acute rejection via shifting TH1/TH2 cytokine balance in rat liver transplantation. Transplantation proceedings. 2013;45:2451–2454. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2013.01.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locatelli I, Sutti S, Jindal A, Vacchiano M, Bozzola C, Reutelingsperger C, Kusters D, Bena S, Parola M, Paternostro C, Bugianesi E, McArthur S, Albano E, Perretti M. Endogenous annexin A1 is a novel protective determinant in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in mice. Hepatology. 2014;60:531–544. doi: 10.1002/hep.27141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumeng CN, Bodzin JL, Saltiel AR. Obesity induces a phenotypic switch in adipose tissue macrophage polarization. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2007;117:175–184. doi: 10.1172/JCI29881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maderna P, Godson C. Lipoxins: resolutionary road. British journal of pharmacology. 2009;158:947–959. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00386.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez J, Verbist K, Wang R, Green DR. The relationship between metabolism and the autophagy machinery during the innate immune response. Cell metabolism. 2013;17:895–900. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masoodi M, Kuda O, Rossmeisl M, Flachs P, Kopecky J. Lipid signaling in adipose tissue: Connecting inflammation & metabolism. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2014.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew AV, Okada S, Sharma K. Obesity related kidney disease. Current diabetes reviews. 2011;7:41–49. doi: 10.2174/157339911794273928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNelis JC, Olefsky JM. Macrophages, immunity, and metabolic disease. Immunity. 2014;41:36–48. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuhofer A, Zeyda M, Mascher D, Itariu BK, Murano I, Leitner L, Hochbrugger EE, Fraisl P, Cinti S, Serhan CN, Stulnig TM. Impaired local production of proresolving lipid mediators in obesity and 17-HDHA as a potential treatment for obesity-associated inflammation. Diabetes. 2013;62:1945–1956. doi: 10.2337/db12-0828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Sullivan TP, Vallin KS, Shah ST, Fakhry J, Maderna P, Scannell M, Sampaio AL, Perretti M, Godson C, Guiry PJ. Aromatic lipoxin A4 and lipoxin B4 analogues display potent biological activities. Journal of medicinal chemistry. 2007;50:5894–5902. doi: 10.1021/jm060270d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh DY, Morinaga H, Talukdar S, Bae EJ, Olefsky JM. Increased macrophage migration into adipose tissue in obese mice. Diabetes. 2012;61:346–354. doi: 10.2337/db11-0860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ost A, Svensson K, Ruishalme I, Brannmark C, Franck N, Krook H, Sandstrom P, Kjolhede P, Stralfors P. Attenuated mTOR signaling and enhanced autophagy in adipocytes from obese patients with type 2 diabetes. Mol Med. 2010;16:235–246. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2010.00023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perretti M, D'Acquisto F. Annexin A1 and glucocorticoids as effectors of the resolution of inflammation. Nature reviews Immunology. 2009;9:62–70. doi: 10.1038/nri2470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polyzos SA, Kountouras J, Zavos C, Tsiaousi E. The role of adiponectin in the pathogenesis and treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Diabetes, obesity & metabolism. 2010;12:365–383. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2009.01176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prieto P, Cuenca J, Traves PG, Fernandez-Velasco M, Martin-Sanz P, Bosca L. Lipoxin A4 impairment of apoptotic signaling in macrophages: implication of the PI3K/Akt and the ERK/Nrf-2 defense pathways. Cell death and differentiation. 2010;17:1179–1188. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Y, Hamilton JL, Bird MD, Chen MM, Ramirez L, Zahs A, Kovacs EJ, Makowski L. Adipose inflammation and macrophage infiltration after binge ethanol and burn injury. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 2014;38:204–213. doi: 10.1111/acer.12210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rius B, Titos E, Moran-Salvador E, Lopez-Vicario C, Garcia-Alonso V, Gonzalez-Periz A, Arroyo V, Claria J. Resolvin D1 primes the resolution process initiated by calorie restriction in obesity-induced steatohepatitis. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2014;28:836–848. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-235614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki A, Fukuda H, Shiida N, Tanaka N, Furugen A, Ogura J, Shuto S, Mano N, Yamaguchi H. Determination of omega-6 and omega-3 PUFA metabolites in human urine samples using UPLC/MS/MS. Analytical and bioanalytical chemistry. 2015;407:1625–1639. doi: 10.1007/s00216-014-8412-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serhan CN. Resolution phase of inflammation: novel endogenous anti-inflammatory and pro-resolving lipid mediators and pathways. Annual review of immunology. 2007;25:101–137. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serhan CN, Savill J. Resolution of inflammation: the beginning programs the end. Nature immunology. 2005;6:1191–1197. doi: 10.1038/ni1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma K. The link between obesity and albuminuria: adiponectin and podocyte dysfunction. Kidney international. 2009;76:145–148. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma K, Ramachandrarao S, Qiu G, Usui HK, Zhu Y, Dunn SR, Ouedraogo R, Hough K, McCue P, Chan L, Falkner B, Goldstein BJ. Adiponectin regulates albuminuria and podocyte function in mice. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2008;118:1645–1656. doi: 10.1172/JCI32691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spite M, Claria J, Serhan CN. Resolvins, specialized proresolving lipid mediators, and their potential roles in metabolic diseases. Cell metabolism. 2014;19:21–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stienstra R, Haim Y, Riahi Y, Netea M, Rudich A, Leibowitz G. Autophagy in adipose tissue and the beta cell: implications for obesity and diabetes. Diabetologia. 2014;57:1505–1516. doi: 10.1007/s00125-014-3255-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun YP, Tjonahen E, Keledjian R, Zhu M, Yang R, Recchiuti A, Pillai PS, Petasis NA, Serhan CN. Anti-inflammatory and pro-resolving properties of benzo-lipoxin A(4) analogs. Prostaglandins, leukotrienes, and essential fatty acids. 2009;81:357–366. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabas I, Glass CK. Anti-inflammatory therapy in chronic disease: challenges and opportunities. Science. 2013;339:166–172. doi: 10.1126/science.1230720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tordjman J, Poitou C, Hugol D, Bouillot JL, Basdevant A, Bedossa P, Guerre-Millo M, Clement K. Association between omental adipose tissue macrophages and liver histopathology in morbid obesity: influence of glycemic status. Journal of hepatology. 2009;51:354–362. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasconcelos DP, Costa M, Amaral IF, Barbosa MA, Aguas AP, Barbosa JN. Modulation of the inflammatory response to chitosan through M2 macrophage polarization using pro22 resolution mediators. Biomaterials. 2015;37:116–123. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen H, Gris D, Lei Y, Jha S, Zhang L, Huang MT, Brickey WJ, Ting JP. Fatty acid-induced NLRP3-ASC inflammasome activation interferes with insulin signaling. Nature immunology. 2011;12:408–415. doi: 10.1038/ni.2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshizaki T, Kusunoki C, Kondo M, Yasuda M, Kume S, Morino K, Sekine O, Ugi S, Uzu T, Nishio Y, Kashiwagi A, Maegawa H. Autophagy regulates inflammation in adipocytes. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2012;417:352–357. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.11.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.