Abstract

Black sexual minority women are triply marginalized due to their race, gender, and sexual orientation. We compared three dimensions of discrimination—frequency (regularity of occurrences), scope (number of types of discriminatory acts experienced), and number of bases (number of social statuses to which discrimination was attributed)—and self-reported mental health (depressive symptoms, psychological well-being, and social well-being) between 64 Black sexual minority women and each of two groups sharing two of three marginalized statuses: (a) 67 White sexual minority women and (b) 67 Black sexual minority men. Black sexual minority women reported greater discrimination frequency, scope, and number of bases and poorer psychological and social well-being than White sexual minority women and more discrimination bases, a higher level of depressive symptoms, and poorer social well-being than Black sexual minority men. We then tested and contrasted dimensions of discrimination as mediators between social status (race or gender) and mental health outcomes. Discrimination frequency and scope mediated the association between race and mental health, with a stronger effect via frequency among sexual minority women. Number of discrimination bases mediated the association between gender and mental health among Black sexual minorities. Future research and clinical practice would benefit from considering Black sexual minority women's mental health in a multidimensional minority stress context.

Keywords: sexual orientation, human sex differences, racial and ethnic differences, sex discrimination, racial and ethnic discrimination, mental health, minority stress, intersectionality

Black sexual minority women have been described as experiencing “triple jeopardy” on account of their multiply marginalized social status (Bowleg, Huang, Brooks, Black, & Burkholder, 2003; Greene, 1994). Beyond their oppression within the dominant culture due to their race, gender, and sexual orientation, Black sexual minority women experience stigma and discrimination within the Black community based on their sexual orientation (Battle & Crum, 2007; Bowleg et al., 2003; Greene, 1994) and within the sexual minority community based on their race (Battle & Crum, 2007; Loiacano, 1989). Further, as women, they face social penalties based on their gender in both the Black community (hooks, 1981) and the sexual minority community (Frye, 1983; Johnson & Samdahl, 2005). Minority stress theory posits that people of disadvantaged social status (e.g., due to their race, gender, and/or sexual orientation) are exposed to social stress (e.g., discriminatory events) and resources (e.g., social support) related to that status, and these social factors determine the impact of social status on mental health outcomes (Meyer, 2003). In particular, social stress is considered to mediate the relationship between social status and mental health (Meyer, 2003; Schwartz & Meyer, 2010).

The layered forms of oppression that Black sexual minority women face could increase their risk for negative mental health outcomes. From the perspective of intersectionality, social identities and as sociated inequalities depend upon and construct one another (Bowleg, 2008; Cole, 2009). A given combination of marginalized social statuses creates a subjective experience that is unique from that which is created by the combination of any fewer of those statuses, including unique discrimination experiences. Therefore, the discrimination and mental health disparities that Black sexual minority women face cannot be inferred from the discrimination and mental health experiences reported by Blacks, sexual minorities, and/or women considered as unitary groups (Bowleg, 2008, 2012). Instead, direct investigation of these subjective experiences with Black sexual minority women themselves is required. In addition, testing the minority stress hypothesis that Black sexual minority women are at greater risk for negative mental health outcomes than socially disadvantaged groups who do not face the same combination of racism, sexism, and heterosexism that they do requires direct comparison of Black sexual minority women to these other groups (Schwartz & Meyer, 2010).

In the current study, we assessed experiences of discrimination and mental health among Black sexual minority women as compared to two other multiply marginalized groups: White sexual minority women (who share gender and sexual orientation but not race) and Black sexual minority men (who share race and sexual orientation but not gender). Using this approach, we elucidated disparities that Black sexual minority women face by race and gender within the sexual minority community. Additionally, we assessed and contrasted three dimensions of discrimination (frequency, scope, and number of bases) as mediators of the relationship between social status and mental health.

Mental Health Disparities and Black Sexual Minority Women

Studies on mental health disparities between socially advantaged and disadvantaged groups have provided mixed support for minority stress theory (Schwartz & Meyer, 2010). Consistent with minority stress hypotheses, research has shown that sexual minority adults experience a higher prevalence of mental disorders than their heterosexual counterparts (King et al., 2008; Meyer, 2003). However, gender- and race-based comparisons do not show the same pattern: In the general population (including people of all sexual orientations), women report a higher lifetime prevalence of anxiety and mood disorders but a lower prevalence of substance use and impulse-control disorders compared to men (Kessler et al., 2005). Also in contrast to the premise that greater social disadvantage contributes to poorer mental health, comparisons by race within the general population have indicated that Blacks show lower lifetime risk and prevalence for anxiety, mood, and substance use disorders as compared to Whites (Breslau et al., 2006; Kessler et al., 2005).

Notably and consistent with criticisms of the public health literature broadly (Bowleg, 2012), extant research on mental health disparities often makes comparisons by focusing solely on differences based on one social status (e.g., sexual orientation, gender, or race), yielding limited insight about the mental health risks that are associated with the combinations of sexual orientation-, gender-, and race-based oppressions experienced by multiply marginalized groups such as Black sexual minority women. To understand the mental health risks experienced by Black sexual minority women, a more nuanced examination of mental health disparities by gender and race within the sexual minority community is warranted.

A limited number of studies have documented mental health characteristics of Black sexual minority women alone or in comparison to other sexual minority groups. Those studies reporting prevalence data have suggested a high level of depression among Black sexual minority women. For example, 32% (Dibble, Eliason, & Crawford, 2012) and 38% (Mays, Cochran, & Roeder, 2003) of two national samples of Black sexual minority women reported recent symptoms consistent with at least mild depression, and 47% of a community sample of Black sexual minority women met diagnostic criteria for depression at some point during their lifetime (Bostwick, Hughes, & Johnson, 2005). When considered relative to White sexual minority women, Black sexual minority women have indicated poorer mental health in some domains but not others. For instance, Black sexual minority women have reported higher psychiatric distress on average (based on Brief Symptom Inventory mean scores; Morris, Waldo, & Rothblum, 2001) and been more likely to endorse symptoms of alcohol dependence in the past year (35% of Black sexual minority women vs. 22% of White sexual minority women) but reported similar levels of depression in the past year (22% of Black sexual minority women vs. 19% of White sexual minority women) and lower lifetime depression (47% of Black sexual minority women vs. 61% of White sexual minority women; Bostwick et al., 2005). Findings have been similarly mixed in mental health comparisons between Black sexual minority women and Black sexual minority men; for example, compared to HIV-negative and serostatus-unknown Black sexual minority men, Black sexual minority women have reported greater overall depressive distress and more somatic complaints but a comparable level of interpersonal problems and frequency of suicidal thoughts (Cochran & Mays, 1994).

In the context of research on sexual minority mental health, Kertzner, Meyer, Frost, and Stirratt (2009) advocate for studying both negative and positive dimensions of mental health, that is, well-being in addition to distress. From their perspective, distress and well-being are not at opposite ends of a single spectrum but rather should be conceptualized as separate constructs measured along distinct continua. Furthermore, when considering sexual minority individuals in a minority stress context, both psychological and social dimensions of well-being ought to be considered (Kertzner, Meyer, Frost, & Stirratt, 2009). Psychological well-being emphasizes positive functioning, including self-acceptance, perceived personal growth, a sense of meaning/purpose in life, positive relations with others, the ability to manage oneself and one's environment, and self-determination (Ryff & Keyes, 1995). In contrast to psychological well-being, which encompasses dimensions of private life, social well-being involves “the appraisal of one's circumstances and functioning in society” (Keyes, 1998, p. 122), including integration within society, acceptance of others, perceived contribution to society, optimism about society's future, and perceived coherence of society (Keyes, 1998). Supporting the assertion that psychological and social well-being are conceptually distinct from psychological distress and from one another, Kertzner et al. (2009) reported disparate patterns of social disparities across the domains of depression, psychological well-being, and social well-being within a sample of sexual minority adults. Thus, all three domains are important to consider when examining mental health disparities faced by sexual minorities in general and Black sexual minority women in particular.

Discrimination and Mental Health

According to minority stress theory, discrimination is one of the social stressors through which marginalized social status negatively impacts mental health (Meyer, 2003). Discrimination refers to “behavior that creates, maintains, or reinforces advantage for some groups and their members over other groups and their members” (Dovidio, Hewstone, Glick, & Esses, 2010, p. 10). A recent community-based study indicated that discrimination based on race (85% lifetime prevalence), gender (52%), and sexual orientation (47%) were all commonly experienced by Black sexual minority women (Wilson, Okwu, & Mills, 2011). Among sexual minorities, reported discrimination prevalence has varied by participant gender and race (Krieger & Sidney, 1997).

Unlike the mixed evidence regarding the relationship between social status and mental health, evidence regarding the relationship between perceived discrimination and mental health has generally supported minority stress theory, which predicts that experiences of discrimination adversely impact mental health across a variety of mental health outcomes (Pascoe & Smart Richman, 2009; Schmitt, Branscombe, Postmes, & Garcia, 2014). There have been some indications that this relationship may be stronger or more consistent for negative mental health outcomes such as depression, anxiety, and psychological distress (defined broadly) as compared to positive mental health outcomes such as positive mood and well-being, although significant associations have been found relative to both (Paradies, 2006; Schmitt et al., 2014). When considered separately in a recent meta-analysis of studies encompassing a broad range of marginalized groups, racism, sexism, and heterosexism were each found to be negatively associated with mental health, with heterosexism showing the strongest association (Schmitt et al., 2014).

A limited number of quantitative studies have examined the link between self-reported experiences of discrimination and mental health among sexual minority women of color (DeBlaere & Bertsch, 2013; DeBlaere et al., 2014; Selvidge, Matthews, & Bridges, 2008; Szymanski & Meyer, 2008; Wilson et al., 2011), even fewer of which have focused on Black sexual minority women in particular (Szymanski & Meyer, 2008; Wilson et al., 2011). Generally, discrimination has been measured separately by race, gender, and/or sexual orientation, and often these different forms of discrimination have been examined simultaneously in an additive model. Of the identified studies with sexual minority women of color that have reported results of bivariate analyses, all forms of discrimination examined have been significantly related to psychological distress (i.e., racism and heterosexism, Szymanski & Meyer, 2008; sexism, DeBlaere & Bertsch, 2013; racism, sexism, and heterosexism, DeBlaere et al., 2014). However, when multiple forms of discrimination have been considered simultaneously along with other variables relative to mental health outcomes in sexual minority women of color, typically only one form, if any, has been found to account for unique variance (e.g., racism, when considered with heterosexism, Szymanski & Meyer, 2008; heterosexism, when considered with racism and sexism, DeBlaere et al., 2014; neither sexism nor heterosexism when considered together, Selvidge et al., 2008). Thus, to date, evidence is lacking for an additive impact of discrimination on different bases relative to mental health among sexual minority women of color, although such an additive effect has been documented among other minority samples (Chae et al., 2010; Szymanski & Owens, 2009).

Conceptualizing and measuring “discrimination”

Inquiring about discrimination experienced on one or more pre-specified basis(es) fails to capture the overall amount of discrimination an individual may be experiencing. A two-stage approach to measuring discrimination frequency, in which an individual first reports discrimination experienced and subsequently makes attributions about the basis or bases for that discrimination, is an alternative one that yields a measurement of overall frequency of discrimination, irrespective of basis(es) and allows for multiple bases to be acknowledged (Shariff-Marco et al., 2011). Past studies that have explored the association between discrimination and mental health in sexual minority women of color (DeBlaere & Bertsch, 2013; DeBlaere et al., 2014; Selvidge et al., 2008) have often limited operationalization of discrimination to the frequency of 1–3 pre-specified forms of discrimination (e.g., frequency of race-based discrimination, frequency of gender-based discrimination). However, Black sexual minority women have reported experiencing discrimination based on multiple other characteristics, such as body weight, age, and income (Wilson et al., 2011). Pre-specifying the basis or bases of discrimination in measures of discrimination frequency— even if intersectional bases (e.g., “gendered racism”; Carr, Szymanski, Taha, West, & Kaslow, 2014; Thomas, Witherspoon, & Speight, 2008) are included—ignores discrimination based on other, unspecified characteristics or combinations thereof and renders the overall frequency of discrimination experienced indiscernible.

An alternative approach to considering both discrimination frequency and bases of discrimination simultaneously, which circumvents this problem, is to consider frequency and bases as separate dimensions of discrimination and therefore as separate variables. In this study, we measured discrimination frequency in terms of how often participants reported experiencing discriminatory events in their daily life (irrespective of the marginalized status(es) to which they attributed the events), and then quantified the number of different marginalized statuses (race, gender, and/or sexual orientation) that were perceived as bases for discrimination. Previous research operationalizing discrimination in terms of the number of bases among sexual minority adults has indicated that, on average, those experiencing discrimination on a single basis—such as sexual orientation only— were no more likely to have had a mental health disorder in the past year as compared to sexual minority participants experiencing no discrimination, whereas those experiencing discrimination on two and three bases were 2.49 and 3.24 times more likely to have had a disorder, respectively (Bostwick, Boyd, Hughes, West, & McCabe, 2014). Thus, experiencing discrimination on more bases may confer a greater risk to one's mental health.

In addition to considering frequency and number of bases of discrimination, we considered the scope of discrimination, which we defined as the number of types of discriminatory acts (e.g., denial of services, name-calling, distrust) experienced. Previous literature has suggested that perceiving discrimination to be pervasive or systemic, and therefore present across multiple contexts (as opposed to only in isolated circumstances), may be especially psychologically detrimental (Schmitt & Branscombe, 2002; Schmitt, Branscombe, & Postmes, 2003; Schmitt et al., 2014). Thus, irrespective of the frequency of discrimination or basis(es) for discrimination, we expected that experiencing many different types of everyday discriminatory acts would take a greater psychological toll than experiencing fewer.

Examining discrimination as a mediator

Minority stress theory posits that social stressors such as discrimination mediate the relationship between social status and mental health (Meyer, 2003). In their critique of existing literature pertaining to social stress models of health disparities, Schwartz and Meyer (2010) noted that, of the many studies conceptualizing discrimination as a mediating mechanism (M) of the relationship between social status (X) and mental health (Y), very few have actually tested for mediation. Often a within-group design has been employed, whereby discrimination and mental health are examined within a single marginalized group. Such a design essentially examines the relationship between the mediator (M) and outcome (Y) but does not vary the social status (X) and therefore limits the inferences that can be made about the causal effect of marginalized social status on mental health. Although some scholars have criticized the use of racial categories as independent variables, particularly when they are treated as explanatory constructs in lieu of measuring associated conditions or processes (e.g., discrimination) driving a given outcome (Helms, Jernigan, & Mascher, 2005), Schwartz and Meyer (2010) highlight the need to measure both the process and the disadvantaged status (e.g., race), analyzing the former as a mediator in testing social stress theories.

In addition, among the studies that have tested for mediation, to our knowledge, none has formally contrasted the mediating effects of multiple dimensions of discrimination in a single model. Multiple mediation analysis presents an objective analytic method of comparing the magnitude of indirect effects through different pathways and determining the significance of any differences that emerge (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). In practical terms, this technique helps to elucidate variables among the set of those examined that are likely to be contributing most to identified disparities in mental health. Therefore, in the current study, we sought to contrast dimensions of discrimination as mediators of the social status→mental health relationship.

The Present Study

In sum, the discrimination experiences and mental health disparities faced by Black sexual minority women relative to sexual minority groups who do not face the same trifold oppression, as well as the potential mediating impact of discrimination (as indicated by minority stress theory), are poorly understood. Thus, we had three specific objectives and hypotheses for the present study. First, we sought to describe and identify differences in negative and positive mental health outcomes by race among sexual minority women and by gender among Black sexual minority adults. We hypothesized that Black sexual minority women would experience poorer mental health (i.e., greater depressive symptoms, poorer psychological well-being, and poorer social well-being) relative to both White sexual minority women and Black sexual minority men (Hypothesis 1).

Second, we sought to describe and identify differences in everyday discrimination along three dimensions (frequency, scope, and number of bases) by race among sexual minority women and by gender among Black sexual minority adults. We hypothesized that Black sexual minority women would report experiencing discrimination on more bases than the other two comparison groups (Hypothesis 2). Because we considered between-group comparisons of discrimination frequency and scope to be exploratory, we did not develop specific hypotheses for these dimensions of discrimination.

Third, we sought to assess whether discrimination mediated the relationship between race and mental health among sexual minority women and between gender and mental health among Black sexual minorities and to explore the relative strengths of the mediational pathways. We hypothesized that discrimination would mediate the relationship between social status (race or gender) and mental health for both (Hypothesis 3), but we did not hypothesize about the relative magnitude of the mediational pathways.

Our research advances the literature (a) by identifying disparities in negative and positive facets of mental health experienced by Black sexual minority women relative to both White sexual minority women and Black sexual minority men; (b) by enhancing understandings of Black sexual minority women's experiences of everyday discrimination and how these experiences differ from the other two groups; (c) by testing the minority stress hypothesis that Black sexual minority women's triply oppressed status is associated with greater social stress (discrimination) and, in turn, poorer mental health; and (d) by clarifying the dimension(s) of discrimination—frequency, scope, and/or number of bases—most relevant to this process.

Method

Participants

Our sample included 64 Black sexual minority women, 67 White sexual minority women, and 67 Black sexual minority men. Participants ranged in age from 18 to 58 years (M = 31.86, SD = 8.95; Mdn = 30.00). Additional characteristics sociodemo-graphic are provided in Table 1 stratified by race and gender. Relative to White sexual minority women, a smaller proportion of Black sexual minority women was educated beyond high school (χ2 = 13.60, p < .001) and employed (χ2 = 6.46, p = .011) negative and a larger proportion had net financial worth (χ2 = 7.67, p = .006). There were no other sociodemographic differences relative to White sexual minority women or Black sexual minority men.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Black Sexual Minority Women, White Sexual Minority Women, and Black Sexual Minority Men.

| Black Sexual Minority Women (n = 64) |

White Sexual Minority Women (n = 67) |

Black Sexual Minority Men (n = 67) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) |

| Age | |||

| ≤ 29 years | 46.9% (30) | 47.8% (32) | 46.3% (31) |

| 30–39 years | 32.8% (21) | 31.3% (21) | 34.3% (23) |

| 40–49 years | 14.1% (9) | 11.9% (8) | 17.9% (12) |

| ≥ 50 years | 6.3% (4) | 9.0% (6) | 1.5% (1) |

| Sexual orientation | |||

| Bisexual | 28.1% (18) | 14.9% (10) | 17.9% (12) |

| Gay | 7.8% (5) | 16.4% (11) | 73.1% (49) |

| Lesbian | 54.7% (35) | 56.7% (38) | 0.0% (0) |

| Other non-heterosexual | 9.4% (6) | 11.9% (8) | 9.0% (6) |

| Education | |||

| ≤ 12 years (high school diploma) | 28.1% (18) | 4.5% (3) | 25.4% (17) |

| >12 years | 71.9% (46) | 95.5% (64) | 74.6% (50) |

| Unemployment | |||

| Unemployed | 23.4% (15) | 7.5% (5) | 16.4% (11) |

| Other (e.g., employed, student) | 76.6% (49) | 92.5% (62) | 83.6% (56) |

| Net financial wortha | |||

| <US$0.00 (negative) | 72.6% (45) | 48.4% (31) | 56.1% (37) |

| ≥ US$0.00 (zero or positive) | 27.4% (17) | 51.6% (33) | 43.9% (29) |

For net financial worth only, there were 62 Black sexual minority women, 64 White sexual minority women, and 66 Black sexual minority men.

Participants were recruited as part of a larger, longitudinal study on identity, social stress, and mental health (“Project STRIDE”; N = 524; additional details available at http://www.columbia.edu/~im15/). Participants in the larger study were English-speaking, diverse (White, Black, and Latino), 18- to 59-year-old men and women who reported that they had resided in New York City for 2 or more years and that their gender identity matched their biological sex. These eligibility criteria were established, given the focus of the larger study on social stress related to race, gender, and sexual orientation as discrete sociological categories.

Procedures

Targeted and snowball sampling techniques were used such that participants were recruited in person from 274 diverse venues (e.g., book stores, coffee shops, festivals, parks, gay bars) in the New York City area or by referral from other participants. Venues that were likely to disproportionally represent people with mental health problems, such as housing support groups or addiction recovery programs, were purposely avoided, given the project's goal to understand social stress and mental health within the general (non-clinical) population (Meyer & Wilson, 2009). Outreach workers included 25 men and women who were diverse in terms of race, age, and sexual orientation. These individuals were generally familiar with the targeted recruitment venues, and many had previous experience with study recruitment and/ or other forms of outreach. They personally approached potential participants, described the study, and requested that each potential participant fill out a brief paper-and-pencil screening form to establish eligibility; brochures and informational cards were provided to potential participants who preferred to call the study staff for screening at an alternative time.

A representative case quota sampling method (Shontz, 1965) was used to ensure approximately equivalent numbers of participants of similar age across race and gender groups, selecting from among eligible screened individuals. A group of interviewers with higher degrees in psychology, social work, public health, and similar fields was responsible for contacting the selected individuals, attempting contact up to 10 times per individual before selecting an alternate. Participants provided written consent and attended a baseline interview lasting approximately 4 hours, during which they completed a combination of measures that were administered orally by one of the interviewers and measures that were self-administered using computer-assisted and paper-and-pencil methods. Participants were compensated for their participation with US$80.00. All study procedures were approved by a university-affiliated institutional review board.

Measures

The measures used in the current study included sociodemo-graphic items, a single measure of lifetime everyday discrimination (which assessed each of the three dimensions of discrimination: frequency, scope, and number of bases), and three separate measures of mental health (depressive symptoms, psychological well-being, and social well-being), presented in that order with other measures interspersed.

Sociodemographic characteristics

Participants reported their sociodemographic characteristics, which were coded as race (Black/African American [1] or White [0]); gender (woman [1] or man [0]); and sexual orientation (bisexual [1] vs. other sexual minority [gay, lesbian, queer, homosexual, or other non-heterosexual] [0]). They also reported their age (years), education (>12 years/high school diploma [1] vs. ≤ 12 years/high school diploma [0]), and employment (currently employed [1] vs. unemployed [0]). Net financial worth (zero or positive [1] vs. negative [0]) was determined by asking participants to calculate the amount of money they would have or owe after converting all assets to cash and paying all debts (Meyer, Schwartz, & Frost, 2008).

Lifetime everyday discrimination

Three dimensions of discrimination (frequency, scope, and number of bases) were assessed with an 8-item version of the Everyday Discrimination Scale (Williams, Yan, Jackson, & Anderson, 1997), a measure of experiences of unfair treatment developed for use with Black Americans. A two-stage approach to administration was used (Shariff-Marco et al., 2011), according to which participants were first asked about their experiences of unfair treatment and subsequently asked to make attributions about the basis(es) of such treatment. Sample items include “How often over your lifetime have you been treated with less courtesy than others?” and “How often over your lifetime have you received poorer services than others in restaurants or stores?” Participants indicated how often they experienced each discriminatory act in their dayto-day life on a scale ranging from 1 (often) to 4 (never), with responses recoded so that higher scores reflected more everyday discrimination. A single item inquiring about lifetime experiences of being threatened or harassed was omitted from the original scale due to conceptual divergence. A mean score was calculated to represent overall frequency of discrimination. Cronbach's α in our study was .85.

We also used data collected via the Everyday Discrimination Scale (Williams et al., 1997) to measure the other two dimensions of discrimination. Scope of discrimination was determined for each participant by totaling the number of different types of discrimination experienced, which could range from 0 (no types) to 8 (all types). For example, if a participant reported having been treated with less courtesy than others and having received poorer services than others in restaurants and stores, but denied experiencing any of the other six discriminatory acts, then their scope of discrimination score would be 2.

For each discriminatory act that participants reported experiencing, they were subsequently asked to indicate whether they attributed that experience to their gender, race, sexual orientation, and/or another characteristic. The number of social statuses from three (race, gender, and sexual orientation) that they endorsed as bases of discrimination was totaled for each participant, resulting in a number of bases of discrimination score ranging from 0 (no discrimination experienced based on gender, race, or sexual orientation) to 3 (discrimination experienced based on all three characteristics). This additive approach has been utilized in past research (Bostwick et al., 2014). Other characteristics were not counted as additional bases of discrimination, given our primary interest in gender, race, and sexual orientation as marginalized social statuses.

Previous research supports the psychometric soundness of the Everyday Discrimination Scale (Bastos, Celeste, Faerstein, & Barros, 2010; Clark, Coleman, & Novak, 2004; Williams et al., 1997). Strong internal consistency has been established: α = .88 among a multiethnic adult community sample (Williams et al., 1997) and α = .87 among a Black student sample (Clark et al., 2004). Validity of the scale is supported by significantly higher scores among Black versus White participants and significant positive associations with self-reported ill health, psychological distress, and physical incapacitation as well as a significant negative association with well-being (Williams et al., 1997). The scale's psychometric strength among minority participants is further supported by a study among Black participants reporting item-total correlations ranging from .50 to .70, split-half reliability of .83, a principal components analysis identifying a single component accounting for 49.34% of standardized variance, and criterion-related validity based on strong positive correlations with internalizing and externalizing symptoms (Clark et al., 2004).

Depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms were measured with the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977), a 20-item measure of depressive symptoms experienced over the past week that has been used with diverse populations, including racial and sexual minority samples (Cochran & Mays, 1994; Dibble et al., 2012; Hightow-Weidman et al., 2011; Mimiaga et al., 2010). Sample items include “During the past week you felt depressed” and “During the past week you were bothered by things that don't usually bother you.” Participants responded according to a 4-point scale ranging from 0 (rarely or none of the time [<1 day]) to 3 (most or all of the time [5–7 days]). Items were reverse-scored as needed and a mean scale score was calculated, with higher scores reflecting a higher level of depressive symptoms.

Cronbach's αs of .84–.85 in community samples and .90 in a psychiatric inpatient sample indicate strong internal reliability of the CES-D (Radloff, 1977); in our study, α = .92. Validity of the CES-D has been indicated via score correlations with patient self-report measures and clinician ratings as well as the measure's differentiation of psychiatric inpatient and general population samples (Radloff, 1977). Its validity for use with racial and sexual minority samples is further supported by its strong negative correlation with measures of mental health and other dimensions of well-being among Black lesbians (Dibble et al., 2012).

Psychological well-being

Psychological well-being was assessed with an 18-item measure (Ryff & Keyes, 1995) developed as an abbreviated form of a longer, 120-item measure (Ryff, 1989). Items spanned six domains (with 3 items per domain): self-acceptance, positive relations with others, autonomy, environmental mastery, purpose in life, and personal growth. Sample items include “When I look at the story of my life, I am pleased with how things have turned out” and “For me, life has been a continuous process of learning, changing and growth.” Participants rated their agreement on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). For each item, we asked participants to rate their agreement in a single step rather than using the two-step “unfolding” technique originally used (Ryff & Keyes, 1995), according to which participants first indicated whether they agreed or disagreed, and then indicated the extent of their (dis)agreement. We also included a “don't know” center point in the response scale that was not included in the original instrument.

In establishing the psychometric soundness of the 18-item measure, confirmatory factor analysis suggested a six-factor solution (corresponding to domains listed above) to be stronger than a single-factor solution (Ryff & Keyes, 1995). The validity of the six subscales was supported via their significant positive correlations with self-reported happiness and satisfaction as well as significant negative correlations with depression (Ryff & Keyes, 1995). However, concerns about the psychometric properties of the individual 3-item subscales have subsequently been raised (Ryff, 2014), as has controversy over the measure's capacity to capture six distinct dimensions of psychological well-being (Springer & Hauser, 2006; Springer, Hauser, & Freese, 2006). Therefore, consistent with assertions that the scale would be better treated as a unitary measure of global psychological well-being (Springer et al., 2006) and given low internal consistency across subscales in the present study (αs = .25–.55), a mean score of all 18 items (reverse-scored as needed) was calculated as an indicator of global psychological well-being (α = .75) such that higher scores indicated greater well-being.

Social well-being

Social well-being was assessed with a 15-item measure of participants’ relationship with their social environments (Keyes, 1998), which covered five domains (with 3 items per domain): social acceptance, social actualization, social contribution, social coherence, and social integration. Sample items include “Society has stopped making progress” and “I have nothing important to contribute to society.” Participants rated their agreement using a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). For each item, we asked participants to rate their agreement in a single step rather than using the two-step “unfolding” technique originally used (Keyes, 1998) and included a “don't know” center point in the response scale.

In establishing the psychometric soundness of the 15-item measure, confirmatory factor analysis suggested a five-factor solution (corresponding to domains listed earlier) to be stronger than a single-factor solution (Keyes, 1998). The validity of the five subscales was supported via their significant positive correlations with generativity and perceived neighborhood health as well as their significant negative correlation with perceived constraints (Keyes, 1998). Given low-to-moderate internal consistencies across subscales in this study (αs = .36–.74) and consistent with past approaches (Kertzner et al., 2009), a mean score was calculated across all 15 items (reverse-scored as needed) as an indicator of global social well-being (α = .78) such that higher scores reflected greater well-being.

Analyses

All descriptive and inferential statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 19 software. Inferential analyses included adjustments for age, sexual orientation (bisexual or other sexual minority), education, unemployment, and net financial worth in order to isolate unique variance in discrimination and mental health explained by the social characteristics of interest: race and gender. Univariate analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs) were conducted to assess between-group differences in mental health (depressive symptoms, psychological well-being, and social well-being) and discrimination (frequency, scope, and number of bases). Logistic regressions were performed to examine group differences in the proportion of participants who had ever experienced each type of discrimination (treated with less courtesy, treated with less respect, etc.) and discrimination on each basis (race, gender, and sexual orientation).

Bootstrapping was conducted to test each dimension of discrimination as a mediator (M) of the social status (X)→mental health (Y) relationship and to contrast multiple dimensions of discrimination as mediators. This resampling methodology, which has received increasing recognition as the optimal approach for testing indirect effects, requires no assumptions about the normality of the sampling distribution of the indirect effect, is appropriate for use with small samples, and minimizes Type 1 error (Hayes, 2009; Shrout & Bolger, 2002). Hayes’ (2013) PROCESS macro was used to generate 5,000 bootstrapped samples, from which bias-corrected and accelerated confidence intervals (CIs) were established to estimate indirect effects for all mediation models. Current recommendations for testing indirect effects, which do not require a significant bivariate relationship between X and Y (Hayes, 2009; Shrout & Bolger, 2002), were applied.

In approaching the mediational analyses, we first sought to establish whether each dimension of discrimination (frequency, scope, and number of bases) that significantly differed between the two comparison groups (as established in the preceding ANCOVAs) mediated the relationship between social status and mental health. We chose to analyze mental health variables as separate outcomes rather than assuming them to be indicators of a single latent construct and potentially missing differential patterns of effects. Separate single-mediator models were tested using bootstrapping for each of the three mental health outcomes: (a) depressive symptoms, (b) psychological well-being, and (c) social well-being, adjusting for other sociodemographic characteristics. Significance of indirect effects was established by bias-corrected and accelerated CIs that did not straddle zero.

Second, we sought to directly contrast the magnitude of the indirect paths identified by constructing parallel multiple mediator models and testing them using bootstrapping. Of note, multiple mediation analyses were not intended to re-establish whether a hypothesized mediator in fact mediated the effect of social status on mental health (as established in analysis of single mediator models) but rather to establish and contrast the specific indirect effect of each hypothesized mediator adjusting for all other mediators and sociodemo-graphic characteristics other than gender or race (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). Thus, the purpose of these follow-up analyses was to identify the unique ability of any one dimension of discrimination to mediate the relationship between social status and mental health above and beyond the other(s) and to compare the magnitude of this unique ability for one dimension to the unique ability of any others (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). For any given mental health outcome, each dimension of discrimination through which a significant indirect effect was found in the single-mediator model was subsequently included in the multiple mediator model predicting that outcome. Collinearity diagnostics (variance inflation factor [VIF] and tolerance) were calculated for dimensions of discrimination considered as parallel mediators to ensure that they were within acceptable limits for simultaneous inclusion within a single model. Significance of indirect and contrast effects was established by bias-corrected and accelerated CIs that did not straddle zero. A significant contrast effect for any two mediating variables indicated that the specific indirect effect through one variable was significantly larger than the specific indirect effect through the other, given the same sign of the specific indirect effects being compared (Hayes, 2013).

Missing data were rare among the 198 participants in this study, with a 100% completion rate for all sociodemographic characteristics except net financial worth (97% completion rate) and a 99–100% completion rate for each of the primary measures of interest. Missing values were excluded pairwise for correlation analyses and listwise for all other inferential analyses.

Results

Table 2 shows descriptive statistics (mean, SD, and range of scores) as well as bivariate correlations for discrimination and mental health variables of interest for the full sample. Frequency and scope of discrimination were positively correlated with depressive symptoms and negatively correlated with psychological well-being; number of bases of discrimination was also negatively correlated with psychological well-being. No significant bivariate correlations between any dimension of discrimination and social well-being were found.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations for Discrimination and Mental Health Variables Among Sexual Minority Adults.

| Measure | n | M | SD | Possible Range of Scores | Actual Range of Scores | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Frequency of discrimination | 198 | 2.41 | 0.57 | 1–4 | 1.00–3.63 | — | ||||

| 2 Scope of discrimination | 198 | 6.72 | 1.92 | 0–8 | 0.00–8.00 | .80** | — | |||

| 3 Bases of discrimination | 198 | 2.09 | 0.82 | 0–3 | 0.00–3.00 | .50** | .50** | — | ||

| 4 Depressive symptoms | 197 | 0.64 | 0.54 | 0–3 | 0.00–2.70 | .35** | .22** | .09 | — | |

| 5 Psychological well-being | 198 | 5.48 | 0.70 | 1–7 | 3.24–6.82 | –.29** | –.18* | –.22** | –.55** | — |

| 6 Social well-being | 196 | 4.81 | 0.84 | 1–7 | 2.47–6.87 | –.11 | –.04 | .00 | –.37** | .53** |

p < .05.

p < .01.

Between-Group Comparisons

Black sexual minority women were separately compared to (a) White sexual minority women to examine race-based differences among sexual minority women and (b) Black sexual minority men to examine gender-based differences among Black sexual minority adults, adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics. Table 3 displays between-group mean comparisons for depressive symptoms, psychological well-being, and social well-being. Relative to White sexual minority women, Black sexual minority women reported poorer psychological and social well-being. Relative to Black sexual minority men, Black sexual minority women reported a higher level of depressive symptoms and poorer social well-being. Thus, Hypothesis 1 was supported for some but not all mental health outcomes.

Table 3.

Differences in Mental Health by Race and Gender Among Sexual Minority Adults.

| Race |

Gender |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black Women |

White Women |

Black Women |

Black Men |

|||||

| Mental health | M (SE)a | M (SE)a | F | p | M (SE)b | M (SE)b | F | p |

| Depressive symptoms | 0.72 (0.08) | 0.69 (0.08) | 0.07 | .791 | 0.72 (0.07) | 0.53 (0.06) | 4.24 | .038 |

| Psychological well-being | 5.25 (0.10) | 5.61 (0.09) | 6.29 | .014 | 5.29 (0.09) | 5.54 (0.09) | 3.88 | .051 |

| Social well-being | 4.59 (0.11) | 4.93 (0.11) | 3.93 | .050 | 4.57 (0.11) | 4.89 (0.10) | 4.78 | .031 |

Note. SE = standard error. All between-group analyses were adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics (i.e., age, sexual orientation, education, unemployment, and net financial worth).

Estimated marginal means and standard errors based on female participants only, adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics.

Estimated marginal means and standard errors based on Black participants only, adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics.

Turning to frequency of discrimination, the frequency of everyday discrimination ([1] never to [4] often) experienced by Black sexual minority women (estimated marginal mean [EMM] = 2.59, standard error [SE] = 0.08) was greater than that experienced by White sexual minority women (EMM = 2.20, SE = 0.07), F(1, 119) = 12.48, p = .001. There was no difference in the frequency of everyday discrimination reported by Black sexual minority women and Black sexual minority men.

Turning to scope of discrimination, the total number of types of discriminatory acts of eight listed (e.g., less courteous treatment, name-calling) that were experienced by Black sexual minority women (EMM = 7.04, SE = 0.25) was greater than the total number experienced by White sexual minority women (EMM = 6.28, SE = 0.25), F(1, 119) = 4.06, p = .046. There was no difference in the scope of discrimination reported by Black sexual minority women and Black sexual minority men.

Table 4 shows the proportion of participants who experienced each of the eight different types of everyday discriminatory acts as well as comparisons per act by race among sexual minority women and by gender among Black sexual minority adults. Each of the eight acts was reportedly experienced by the majority of all groups, with the only between-group difference emerging with regard to having been feared: Relative to Black sexual minority men, a smaller proportion of Black sexual minority women reported experiencing this discriminatory act.

Table 4.

Differences in Lifetime Experiences of Discrimination by Race and Gender Among Sexual Minority Adults.

| Race |

Gender |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black Women (n = 64) % (n) | White Women (n = 67) %(n) | AOR [95% CI] | p | Black Men (n = 67) % (n) | AOR [95% CI] | p | |

| Scope of discrimination | |||||||

| 1 Been treated with less courtesy than others | 90.6% (58) | 91.0% (61) | 0.17 [0.02, 1.24] | .081 | 91.0% (61) | 0.79 [0.21, 2.97] | .739 |

| 2 Been treated with less respect than others | 85.9% (55) | 91.0% (61) | 0.49 [0.10, 2.43] | .382 | 91.0% (61) | 1.30 [0.37, 4.65] | .682 |

| 3 Received poorer services than others in restaurants or stores | 84.4% (54) | 82.1% (55) | 0.25 [0.06, 1.04] | .056 | 85.1% (57) | 0.77 [0.25, 2.40] | .658 |

| 4 Experienced people treating you as if you're not smart | 81.3% (52) | 83.6% (56) | 0.89 [0.29, 2.76] | .840 | 85.1% (57) | 1.21 [0.44, 3.33] | .714 |

| 5 Experienced people acting as if they are better than you are | 90.6% (58) | 89.6% (60) | 0.25 [0.05, 1.36] | .108 | 95.5% (64) | 1.99 [0.38, 10.46] | .417 |

| 6 Experienced people acting as if they are afraid of you | 73.4% (47) | 67.2% (45) | 0.43 [0.16, 1.14] | .088 | 86.6% (58) | 2.87 [1.01, 8.13] | .047 |

| 7 Experienced people acting as if they think you are dishonest | 73.4% (47) | 62.7% (42) | 0.40 [0.15, 1.06] | .066 | 70.1% (47) | 0.73 [0.33, 1.64] | .451 |

| 8 Been called names or insulted | 85.9% (55) | 89.6% (60) | 0.49 [0.12, 2.00] | .315 | 89.6% (60) | 1.10 [0.35, 3.51] | .867 |

|

Bases of discrimination | |||||||

| 1 Race-based discrimination | 89.1% (57) | 29.9% (20) | 0.02 [0.00, 0.09] | <.001 | 94.0% (63) | 1.97 [0.48, 8.11] | .346 |

| 2 Gender-based discrimination | 78.1% (50) | 80.6% (54) | 1.07 [0.34, 3.32] | .913 | 32.8% (22) | 0.10 [0.04, 0.25] | <.001 |

| 3 Sexual orientation-based discrimination | 68.8% (44) | 77.6% (52) | 1.45 [0.57, 3.72] | .436 | 76.1% (51) | 1.53 [0.67, 3.51] | .314 |

Note. AOR = adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval. Odds ratios were adjusted for age, sexual orientation, education, unemployment, and net financial worth. For analyses of group differences per discrimination act, unadjusted odds ratios did not indicate any significant between-group differences (α = .05). For analyses of group differences per discrimination basis, unadjusted odds ratios showed the same pattern ofbetween-group differences as the adjusted odds ratios.

Finally, looking at bases of discrimination, the total number of bases of discrimination of the three listed (race, gender, and sexual orientation) that was experienced by Black sexual minority women (EMM = 2.44, SE = 0.11) was greater than the number experienced by White sexual minority women (EMM = 1.86, SE = 0.11), F(1, 119) = 12.51, p = .001. Black sexual minority women also reported experiencing discrimination on more bases (EMM = 2.37, SE = 0.10)1 than Black sexual minority men (EMM = 2.02, SE = 0.10), F(1, 121) = 6.21, p = .014. Thus, Hypothesis 2 was supported.

Table 4 also displays the proportion of each group who reported experiencing discrimination on each basis. Relative to White sexual minority women, a larger proportion of Black sexual minority women experienced race-based discrimination, but similar proportions of Black sexual minority women and White sexual minority women experienced discrimination based on gender and sexual orientation. Relative to Black sexual minority men, a larger proportion of Black sexual minority women experienced gender-based discrimination, but similar proportions of Black sexual minority women and Black sexual minority men experienced discrimination based on race and sexual orientation.

Mediation Analyses

The indirect effects of race

Our first set of mediation analyses tested the indirect effect of race on mental health through discrimination among sexual minority women. Between-group comparisons revealed significant differences in discrimination frequency, scope, and number of bases by race; therefore, we examined all three forms of discrimination as potential mediators of the relationship between race and mental health.

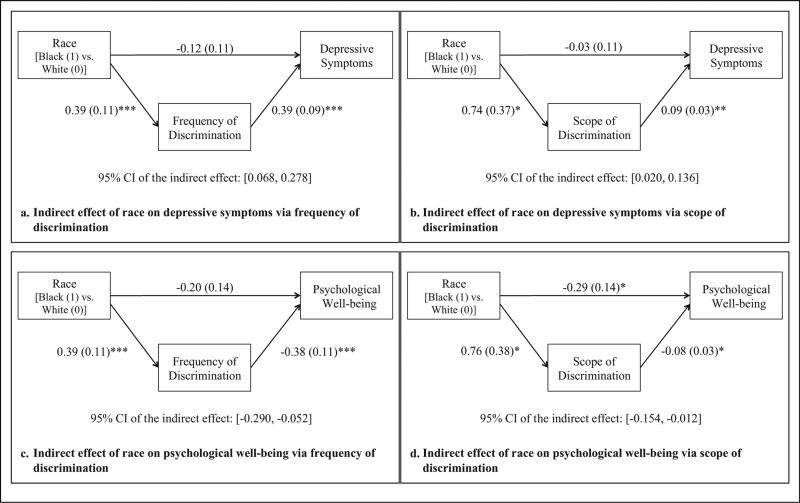

Bootstrapping analyses of single-mediator models revealed significant indirect effects of race on depressive symptoms via frequency of discrimination (95% CI [0.068, 0.278]; see Figure 1a) and scope of discrimination (95% CI [0.020, 0.136]; see Figure 1b) but not number of bases of discrimination (95% CI [−0.078, 0.104]). Mirroring this pattern, significant indirect effects of race on psychological well-being emerged for frequency of discrimination (95% CI [−0.290, −0.052]; see Figure 1c) and scope of discrimination (95% CI [−0.154, −0.012]; see Figure 1d) but not for number of bases of discrimination (95% CI [−0.175, 0.027]). In contrast, there was no significant indirect effect of race on social well-being via any of the three forms of discrimination—frequency: 95% CI [−0.209, 0.031], scope: 95% CI [−0.115, 0.033], and number of bases: 95% CI [−0.039, 0.188]. Thus, among sexual minority women, being Black was associated with experiencing more frequent discrimination and a broader scope of discrimination, both of which, in turn, were associated with a higher level of depressive symptoms and poorer psychological well-being in single-mediator models.

Figure 1.

Single-mediator models of the indirect effects of race on mental health via discrimination. Sociodemographic characteristics (i.e., age, sexual orientation, education, unemployment, and net financial worth) were statistically adjusted for in all analyses. For each model, the unstandardized coefficients and standard errors, b(standard error), of all paths and bias-corrected and accelerated confidence interval of the indirect effect are included. Only models with a significant indirect effect (i.e., confidence interval that does not straddle zero) are shown. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Based on results from single-mediator models, multiple-mediator models including discrimination frequency and scope as parallel mediators were tested for two outcomes: depressive symptoms and psychological well-being. Collinearity diagnostics confirmed that VIF and tolerance values of the two forms of discrimination were within acceptable limits (VIF = 3.02, Tolerance = 0.33).

For the first multiple mediator model, in which race was the independent variable (X), discrimination frequency and discrimination scope were parallel mediators (Ms), and depressive symptoms was the outcome variable (Y), bootstrapping analyses indicated a significant specific indirect effect of race on depressive symptoms via frequency (95% CI [0.042, 0.408]), with a significant contrast effect relative to scope (95% CI [0.007, 0.520]). The specific indirect effect of race on depressive symptoms via scope was not significant in this model (95% CI [−0.120, 0.042]). Thus, among sexual minority women, discrimination frequency uniquely mediated the relationship between race and depressive symptoms above and beyond the mediating effect of discrimination scope.

For the second multiple mediator model, in which race was the independent variable (X), discrimination frequency and discrimination scope were parallel mediators (Ms), and psychological well-being was the outcome variable (Y), bootstrapping analyses indicated a significant specific indirect effect of race on psychological well-being via frequency (95% CI [−0.469, 0.042]), with a significant contrast effect relative to scope (95% CI [−0.624, −0.008]). The specific indirect effect of race on psychological well-being via scope was not significant in this model (95% CI [−0.044, 0.169]). Thus, among sexual minority women, discrimination frequency uniquely mediated the relationship between race and psychological well-being above and beyond the mediating effect of discrimination scope.

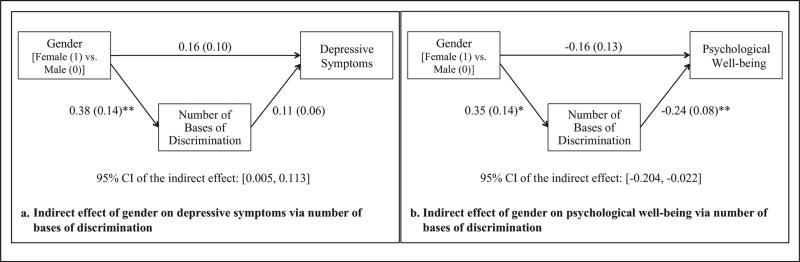

The indirect effects of gender

Our second set of mediation analyses explored the indirect effect of gender on mental health through discrimination among Black sexual minority adults. Between-group comparisons revealed a significant difference by gender in number of bases of discrimination but not discrimination frequency or scope; thus, only number of bases of discrimination was examined as a potential mediator of the relationship between gender and mental health. Bootstrapping analyses revealed a significant indirect effect of gender on depressive symptoms (95% CI [0.005, 0.113]; see Figure 2a) and psychological well-being (95% CI [−0.204, −0.022]; see Figure 2b) via number of bases of discrimination but no significant indirect effect of gender on social well-being via number of bases of discrimination (95% CI [−0.037, 0.134]). Thus, among Black sexual minority participants, being a woman was associated with experiencing more bases of discrimination, which, in turn, was associated with a higher level of depressive symptoms and poorer psychological well-being. Considering these results with the other mediational analyses, Hypothesis 3 (that discrimination would mediate the relationship between social status and mental health) was supported for two of three mental health outcomes, though the mediating dimension(s) of discrimination differed depending on social status (race or gender).

Figure 2.

Single-mediator models of the indirect effects of gender on mental health via discrimination. Sociodemographic characteristics (i.e., age, sexual orientation, education, unemployment, and net financial worth) were statistically adjusted for in all analyses. For both models, the unstandardized coefficients and standard errors, b(standard error), of all paths and bias-corrected and accelerated confidence interval of the indirect effect are included. Only models with a significant indirect effect (i.e., confidence interval that does not straddle zero) are shown. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Discussion

Our results indicated that Black sexual minority women, whose social status is triply marginalized based on their race, gender, and sexual orientation, experienced poorer mental health relative to two multiply marginalized sexual minority groups who do not face the same combination of oppressions. Between-group comparisons for each of the three mental health outcomes revealed that relative to White sexual minority women, Black sexual minority women reported poorer psychological and social well-being. Relative to Black sexual minority men, Black sexual minority women reported a higher level of depressive symptoms and poorer social well-being. Thus, mental health disparities based on both race and gender emerged among subgroups in our sample of sexual minority adults.

Black sexual minority women also experienced greater discrimination than the two comparison groups. Between-group comparisons for each of the three dimensions of discrimination revealed that relative to White sexual minority women, Black sexual minority women reported greater discrimination on all three dimensions assessed—frequency, scope, and number of bases. Relative to Black sexual minority men, Black sexual minority women experienced discrimination on more bases, which is likely attributable to gender-based discrimination; however, they reported experiencing similar frequency and scope of discrimination.

Additionally, discrimination mediated the relationship between social status and mental health for two of three mental health outcomes, and the mediating dimension(s) of discrimination varied according to social status. Among sexual minority women, race indirectly affected depressive symptoms and psychological well-being through discrimination frequency and scope; the indirect effect through frequency was greater in magnitude for both outcomes. Among Black sexual minority adults, gender indirectly affected depressive symptoms and psychological well-being through number of bases of discrimination but not frequency or scope of discrimination.

Interpretation in the Context of Minority Stress Theory

Taken together, results of our study are consistent with the basic premises of minority stress theory. According to several indicators, Black sexual minority women experienced poorer mental health and greater discrimination than groups that did not share their triply disadvantaged status based on race, gender, and sexual orientation. In addition, greater social disadvantage (based on this particular combination of statuses) was associated with more social stress in the form of discrimination, which, in turn, was associated with poorer mental health in terms of depression and reduced psychological well-being.

Although social well-being was poorer among Black sexual minority women relative to both comparison groups (as predicted by minority stress theory), discrimination did not mediate the relationship between social status and social well-being, and none of the bivariate correlations between the three dimensions of discrimination and social well-being were significant. This pattern was surprising, given that discrimination is fundamentally a social process; thus, we would expect everyday experiences of unfair treatment to negatively impact an individual's views of society, perceptions of his or her relationship to society, and other elements of social well-being. It is possible that different mechanisms, such as institutionalized prejudice and other macro-level aggressions, better account for the disparities observed.

For a few analyses, the indirect effects of social status on mental health through discrimination occurred in the absence of a statistically significant total effect of social status on mental health. Interpretation of this result relative to minority stress theory may vary according to the standards applied. Using a sociological perspective, Schwartz and Meyer (2010) outlined four forms of evidence necessary to establish support for this theory: (a) evidence for a main effect of disadvantaged social status on mental health, (b) evidence for an association between social status and social stress (e.g., discrimination), (c) evidence for an association between social stress and mental health, and (d) evidence for a reduced main effect when social stress is controlled. Statistically, these criteria parallel Baron and Kenny's (1986) causal steps approach to establishing statistical mediation, which has come under scrutiny in recent years (Hayes, 2009; Zhao, Lynch, & Chen, 2010).

The absence of a total effect (“main effect”) at the p < .05 level for race relative to depressive symptoms among female participants, or for gender relative to psychological well-being among Black participants, suggests that there are no racial or gender disparities, respectively, to explain and thus would fail to satisfy the first of Schwartz and Meyer's (2010) stipulations for evidence of minority stress theory. However, the statistical literature offers multiple explanations for the occurrence of mediation (or an “indirect effect”) in the absence of a significant total effect, including a lack of statistical power related to sample size2 (Hayes, 2009; MacKinnon & Fairchild, 2009; Shrout & Bolger, 2002) and/or offsetting by mediational paths operating in the opposite direction that were not considered in the tested model (Hayes, 2009; Zhao et al., 2010). Thus, further study using larger group sizes and considering protective factors (e.g., coping and social support) that may offset the established mediational pathways would be valuable for understanding the pattern of results that we observed.

Also, it is important to note that, unlike Schwartz and Meyer's (2010) exposition of between-group health disparities, in the current study the between-group comparisons were performed within a socially marginalized group, rather than between socially marginalized and non-marginalized groups. That differences were found between Black sexual minority women relative to the other subgroups within the already marginalized sexual minority community is congruent with the notion of “triple jeopardy” and highlights the importance of more nuanced consideration of multiply marginalized risk groups in future research.

Intersectionality and Measurement Revisited

Our results support intersectional assertions that the experiences of Black sexual minority women cannot be extrapolated from research documenting disparities among “Blacks,” “sexual minorities,” or “women” as singular groups (Bowleg, 2012). As demonstrated in our study, important differences in exposure to discrimination and associated mental health risks exist within unidimensional groupings such as these. Categorization based on one marginalized status alone fails to account for the intersecting oppressions encountered by multiply marginalized individuals (Collins, 2000).

The intersectionality perspective raises numerous methodological challenges in quantitative research (Bowleg, 2008). Many popular measures of discrimination inquire about a single marginalized status to the exclusion of others (e.g., Index of Race-Related Stress; Utsey & Ponterotto, 1996; Schedule of Sexist Events; Klonoff & Landrine, 1995), and these measures are commonly considered additively (exploring main effects of each form of discrimination concomitantly, e.g., racism and sexism) and sometimes multiplicatively (exploring interactional effects between forms of discrimination, e.g., racism × sexism) among multiply marginalized groups. However, such a measurement approach has been criticized for its underlying assumption that social identities and associated experiences of unfair treatment can be disaggregated; social categories are “confounded” within an individual (Cole, 2009) and a single act of discrimination can be perpetrated on multiple bases (e.g., sexual harrassment based on race-specific stereotypes; Buchanan & Ormerod, 2002; Cole, 2009). A two-stage approach to measuring discrimination (Shariff-Marco et al., 2011), with the first asking about the occurrence of a discriminatory act with no attribution to a specific social status, and the second allowing for attribution to multiple statuses simultaneously, circumvents some problems in this regard. Less commonly, combinations of marginalized statuses have been directly queried in survey items (e.g., asking participants to rate the frequency with which they have been called insulting names that referred to their gender and race, e.g., “Black bitch”; Buchanan, 2005, as cited in Carr et al., 2014) in an attempt to elucidate “intersectional” forms of discrimination (e.g., gendered racism).

In this study, we operationalized discrimination in three ways, with one measure (number of bases) being additive in nature and the others (frequency and scope) sensitive to multiple and potentially intersectional bases of discrimination. Ultimately, multiple quantitative approaches can enhance understanding of the relationship between discrimination and mental health among multiply marginalized groups, including methods that are additive, multiplicative, and intersectional, and these methods can be complemented by qualitative methods of inquiry (Bowleg, 2008; Moradi & Subich, 2003; Shields, 2008; Szymanski & Stewart, 2010).

Research Implications

Findings from our study draw attention to the complex and multifaceted nature of discrimination and the need for a multidimensional approach to its measurement. Whereas Black sexual minority women reported experiencing more discrimination on all three dimensions measured (frequency, scope, and number of bases) relative to White sexual minority women, they only differed from their Black male counterparts on one dimension not typically captured in standard measures of discrimination: number of bases. Incorporating multiple measures of discrimination into research and directly contrasting their strengths as mediating mechanisms allows researchers to pinpoint the element of social experience that may be most detrimental and use this knowledge to inform social change and psychological supports. Future research should not only consider frequency, scope, and number of bases as in the current study but also explore specific combinations of bases as predictors of mental health. Indeed, recent work has suggested that certain constellations of discrimination experiences (e.g., experiencing both gender-based and race-based discrimination) may be especially potent risk factors for mental health problems (Bostwick et al., 2014). In addition, further research not only on the “everyday” forms of discrimination experienced by Black sexual minority women, but also on more severe incidences of victimization (e.g., violence, abuse), would provide a fuller picture of the social challenges faced by this group.

In consideration of the heterogeneity found within the Black female sexual minority community, exploring other distinctions in discrimination experiences and mental health consequences among members of this group is an important direction for future work. Only three social statuses were considered in the classification scheme for our study: sexual orientation, race, and gender. However, multiple other socially devalued characteristics could influence discrimination and/or mental health, including body weight, socioeconomic status (Bucchianeri, Eisenberg, & Neumark-Sztainer, 2013), geographic setting (e.g., urban vs. small town; Swank, Fahs, & Frost, 2013), and conformity to traditional gender roles (Reed & Valenti, 2012). These characteristics could intersect uniquely with sexual orientation, race, and gender.

Greater understanding of the impact of discrimination on Black sexual minority women's mental health is critical to the development of effective evidence-based mental health interventions. Future research should assess mediators and moderators of the pathway between discrimination and mental health to identify potential targets for individual-level intervention. For instance, Jones, Cross, and DeFour (2007) suggest racial identity attitudes may have protective potential against discrimination-related stress among Black women, and they recommend further investigation among Black sexual minority women in particular. Other minority identity attitudes and their intersections would also be important to consider. Mechanisms such as internalized stigma (e.g., internalized homophobia) and rejection sensitivity may also be of particular relevance, not only to mental health outcomes but also to perceived social/psychological resources (Feinstein, Goldfried, & Davila, 2012; Lehavot & Simoni, 2011; Meyer, 2003). Hatzenbuehler (2009), Moradi (2013), and others have offered frameworks for understanding the range of emotional, social, cognitive, and/or physiological processes that may become activated by social stressors such as discrimination and thereby mediate the relationship between social stress and mental health, providing targets for further study and potential intervention.

Practice Implications

Structural interventions (e.g., legalization of same-sex marriage, affirmative action) and community consciousness-raising efforts may help to improve the social conditions faced by Black sexual minority women, but they are unlikely to fully eliminate the intersecting oppressions that these women experience. Thus, although structural interventions are always desirable, other levels of intervention suggested by the minority stress model—including individual-level mental health services—warrant consideration as well (Meyer & Frost, 2013).

Our results highlight the frequency and pervasiveness of everyday discrimination experienced by Black sexual minority women and other multiply marginalized sexual minority groups as well as its potentially deleterious mental health consequences. In the context of mental health services, cultivating providers’ awareness and clinical skills around intersecting marginalized social statuses and encouraging inquiry about clients’ experiences of discrimination will aid in the accuracy of case formulations and provision of more appropriately nuanced care (Carr et al., 2014; DeBlaere & Bertsch, 2013; Szymanski, 2005). Providers ought to contextualize a client's presenting problems within broader sociohistorical injustices and can draw on feminist and womanist perspectives in approaching therapy (Carr et al., 2014; DeBlaere & Bertsch, 2013). Supporting a client's identification and deconstruction of stigmatizing cultural messages around race, gender, and/or sexual orientation may help to interrupt or counteract the internalization of such stigma. Additionally, facilitating a client's development of social networks composed of similar other multiply marginalized individuals through organized groups and promoting collective action is encouraged (Carr et al., 2014; DeBlaere et al., 2014).

Study Limitations

Findings of the current study should be interpreted in light of multiple limitations. First, the sample was recruited via targeted methods and thus may not be representative of a broader population of sexual minority adults, especially individuals who are not open about their sexual orientation and unlikely to participate in a study explicitly recruiting sexual minorities. Second, as with all survey research, self-selection bias may influence the generalizability of findings. In particular, people who did not have the interest, attention, time, and/or mobility needed to engage in a lengthy in-person interview would not have been captured. Third, a Black female heterosexual comparison group was not included in the study from which these data were drawn; therefore, differences by sexual orientation among Black women could not be assessed, and we were only able to provide partial support for the “triple jeopardy” hypothesis.

Fourth, the Everyday Discrimination Scale (Williams et al., 1997), from which all three discrimination scores (frequency, scope, and number of bases) were derived, was originally developed for use with Black Americans and was not explicitly designed to capture acts of sexism and heterosexism. Although the discriminatory acts encompassed by the scale (e.g., being treated with less courtesy than others, receiving poorer services than others in restaurants or stores) can be perpetrated on diverse bases—not just race—the range of discrimination experiences described may not be as comprehensive in its coverage relative to other bases. Fifth, some of the measures included in our study have not been explicitly validated with Black and/or sexual minority samples.

Lastly, the cross-sectional design of the study prohibits inferences about causality to be made. It is possible, for instance, that an individual experiencing depressive symptomatology may be more sensitive to discrimination or prone to recalling such negative experiences. However, previous longitudinal research with Black women has established a causal effect of everyday discrimination on depressive symptoms that is consistent in directionality with minority stress theory (Schulz et al., 2006).

Conclusions

The results of the current study highlight Black sexual minority women's heightened exposure to discrimination, even relative to other multiply disadvantaged sexual minority groups, as well as the mental health risks posed by such discrimination. In addition to prompting further research aimed at understanding mental health disparities more fully, these findings present a call to action for social activists and mental health professionals to combat the social injustice and associated mental health consequences faced by this triply jeopardized group.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr. Trace Kershaw for his consultation on statistical analyses and to participants for their generous contribution to the study.

Funding The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported by Award Numbers R01MH066058, K01MH103080, T32MH020031, and P30MH062294 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Footnotes

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Estimated marginal mean values for Black sexual minority women (a) in the context of comparison to White sexual minority women and (b) in the context of comparison to Black sexual minority men are different from one another because estimated marginal means represent mean values when adjusting for covariates (age, sexual orientation, education, unemployment, and net financial worth) between the two groups involved in each comparison, and White sexual minority women and Black sexual minority men differed on these covariates.

A post hoc sensitivity analysis using G*Power 3.1 indicated that our adjusted ANCOVA model had 80% power to detect a medium (.25) or higher effect with a sample of 128 participants (α = .05); thus, a slightly larger sample size may have enabled detection of a smaller effect (e.g., of gender on psychological well-being among Blacks).

References

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastos JL, Celeste RK, Faerstein E, Barros AJ. Racial discrimination and health: A systematic review of scales with a focus on their psychometric properties. Social Science and Medicine. 2010;70:1091–1099. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battle J, Crum M. Black LGB health and well-being. In: Meyer I, Northridge ME, editors. The health of sexual minorities: Public health perspectives on lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender populations. Springer Science + Business Media; New York, NY: 2007. pp. 320–352. [Google Scholar]

- Bostwick WB, Boyd CJ, Hughes TL, West BT, McCabe SE. Discrimination and mental health among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2014;84:35–45. doi: 10.1037/h0098851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostwick WB, Hughes TL, Johnson T. The co-occurrence of depression and alcohol dependence symptoms in a community sample of lesbians. Journal of Lesbian Studies. 2005;9:7–18. doi: 10.1300/J155v09n03_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L. When Black + lesbian + woman Black lesbian woman: The methodological challenges of qualitative and quantitative intersectionality research. Sex Roles. 2008;59:312–325. [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L. The problem with the phrase women and minorities: Intersectionality—An important theoretical framework for public health. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102:1267–1273. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]