Abstract

Background

Chronic constipation is common and exerts a considerable burden on health-related quality of life and healthcare resource utilization. Anorectal manometry (ARM) and colonic transit testing have allowed classification of subtypes of constipation, raising promise of targeted treatments. There has been limited study of the correlation between physiological parameters and healthcare utilization.

Methods

All patients undergoing ARM and colonic transit testing for chronic constipation at two tertiary care centers from 2000 to 2014 were included in this retrospective study. Our primary outcomes included number of constipation-related and gastroenterology visits per year. Multivariate linear regression adjusting for confounders defined independent effect of measures of colonic and anorectal function on healthcare utilization.

Key Results

Our study included 612 patients with chronic constipation. More than 50% (n=333) of patients had outlet obstruction by means of balloon expulsion testing and 43.5% (n=266) had slow colonic transit. On unadjusted analysis, outlet obstruction (1.98 vs. 1.68), slow transit (2.40 vs 2.07) and high resting anal pressure (2.16 vs. 1.76) were all associated with greater constipation-related visits/year compared to patients without each of those parameters (P<0.05 for all). Outlet obstruction and high resting anal pressure were also associated with greater number of gastroenterology visits/year. After multivariate adjustment, high resting anal pressure was the only independent predictor of increased constipation-related visits/year (P=0.02) and gastroenterology visits/year (P=0.04).

Conclusions and Inferences

Among patients with chronic constipation, high resting anal pressure, rather than outlet obstruction or slow transit, predicts healthcare resource utilization.

Keywords: chronic constipation, resting anal pressure, anorectal manometry, utilization

With a worldwide median prevalence of 16% and an annual direct medical cost in excess of $230 million in the U.S. alone, constipation represents a substantial financial burden to the healthcare system and takes an equally significant toll on health-related quality of life. Constipation-related concerns accounted for almost 8 million ambulatory visits per year in the U.S. in the early 2000s, with more than 1 million patients seeking care for constipation from a gastroenterologist per year during that time period (1). Despite this, little is known about the predictors of healthcare resource utilization among constipated patients. Prior studies evaluating predictors of healthcare seeking in constipation have largely been confined to cross-sectional, observational studies using billing records and survey data to examine the influence of demographics and comorbid disease. Female gender has consistently emerged as the strongest predictor of healthcare utilization in constipation (2, 3). Additionally, comorbid depression(2), higher educational level (3), and severity of constipation symptoms (4) influence likelihood of seeking care.

Physiologically, constipation is often multifactorial and may be governed by slow colonic transit, pelvic floor outlet obstruction, visceral hypersensitivity, or indeed a combination of these parameters. Identification of disordered defecation using anorectal manometry (ARM) has emerged as an important subtype of constipation (5) with good treatment response to biofeedback therapy (6-8). Similarly, the treatment options for slow colonic transit has expanded with the introduction of the clinically-efficacious secretagogues, lubiprostone (9) and linaclotide (10), as well as the 5-HT4 receptor agonist prucalopride (11). Traditional laxatives such as polyethylene glycol remain effective options for some patients as well (12, 13). Despite these advances in the understanding and treatment of chronic constipation, treatment failure is a common and costly aspect of the care of this patient population, accounting for significant healthcare utilization (14). Furthermore, as more therapeutic options with different mechanisms of effect become available, it is increasingly important to identify the physiologic parameters that may be the most significant determinants of healthcare utilization and costs in patients with constipation in order to develop appropriate sequential treatment algorithms for these patients. To our knowledge, there is limited data connecting physiologic measurements in constipation with healthcare seeking.

Therefore, we sought to delineate the relationship between physiology and healthcare resource utilization in a large cohort of patients with chronic constipation evaluated at two large, tertiary treatment centers using established measures of colonic and anorectal function. We hypothesized that physiologic parameters including colonic transit and outlet dysfunction would be predictors of increased clinical visits among the patients with chronic constipation. Evidence linking physiologic measures with healthcare seeking in chronic constipation could provide a better understanding of which patients have the greatest unmet need with the current standard of care and serve as the impetus for new, targeted treatments in the future.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and patient population

We assembled a retrospective cohort population consisting of all adult (≥ 18 years old) patients undergoing both anorectal manometry and colonic transit testing (radiopaque marker study) for chronic constipation at two tertiary referral hospitals serving the greater Boston metropolitan area (Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and Brigham and Women's Hospital (BWH)). Patients were identified using the Research Patient Data Registry (RPDR). This is an electronic database of all patients seeking care within the Partners Healthcare system and is automatically populated with data from multiple sources including clinical encounters, radiology, procedures, laboratory tests, medications, inpatient stays, operative reports, and billing records (15). Patients were excluded if they did not undergo balloon expulsion testing as part of anorectal manometry (n=124), did not undergo colonic transit testing (n=429), or had less than 6 months of follow up in our system (n=153). All data were collected by detailed review of electronic medical records by two authors (K.S. and K.B.). Information was collected regarding anorectal manometry, radiography, medical and psychiatric comorbidities, and current and past prescription medication use for the treatment of chronic constipation and chronic pain. We also extracted information on visit frequency and reasons for visits using primary billing diagnoses.

Primary variables of interest

The primary predictors of interest for this study were physiologic parameters obtained from high-resolution anorectal manometry and colonic transit testing. High-resolution anorectal manometry was performed using the standard methods described in detail by Rao et al (16). Manometry measurements were performed in the left lateral position with a run-in time followed by squeeze testing, attempted defecation, rectoanal inhibitory reflex testing, and rectal sensory testing. Balloon expulsion testing was subsequently performed with insertion of a water-filled (50 mL) balloon in the left lateral position and timed expulsion while the patient sits on a commode. We included the following values obtained from anorectal manometry: mean resting anal sphincter pressure (defined in reference to the rectal pressure), anorectal gradient/defecation index (the difference (for gradient) or ratio (for index) between the intrarectal pressure and residual anal pressure during attempted defecation (5)), and rectal sensation thresholds (intermittent balloon distention for measurement of first sensation, desire to defecate, and maximum tolerable volume). We determined outlet obstruction by means of timed balloon expulsion testing of a 50 mL water-filled balloon inserted in the rectum while the patient is on the commode (16). We dichotomized this variable into normal (≤2 minutes) or prolonged (>2 minutes) as per established standards (17). Because of substantial overlap between the findings of anorectal manometry and balloon expulsion testing, we used balloon expulsion testing alone as the primary indicator of pelvic floor dysfunction. Moreover, Chiarioni et al suggested that balloon expulsion testing has a high level of agreement with both anorectal manometry and pelvic floor surface electromyography in chronic constipation with reproducibility over time (17). During the study period, there was a switch at MGH from water-perfusion manometry to high-resolution manometry which occurred in November 2009. The balloon expulsion testing protocol did not change. All BWH patients underwent high-resolution anorectal manometry. The high-resolution testing protocol was similar between the two centers, but MGH uses the ManoScan AR high resolution manometry system (Given Imaging/Covidien, Dublin, Ireland) while BWH uses the InSIGHT high resolution anorectal manometry system (Sandhill Scientific, Highlands Ranch, CO, USA).

Colonic transit was assessed by means of the Hinton method (18), where a KUB was obtained five days after ingestion of a 24 radiopaque markers in a gelatin capsule. Retention of five or more markers on imaging was defined as slow colonic transit.

Characterization of patient population

We collected demographics (age of first constipation visit, sex, race), medical comorbidities to calculate the Charlson comorbidity index (19), and diagnosis of hypertension, which has shown utility in predicting resource consumption in addition to the variables forming the Charlson index (20). We also collected data on additional comorbidities that may affect constipation-related healthcare utilization including irritable bowel syndrome, depression (21), anxiety, and fibromyalgia. There is no standard constipation treatment policy at these institutions, though biofeedback is often used for the treatment of pelvic floor dyssynergia—which we were unable to capture completely as it is frequently performed outside of our system. We did obtain information on prescription medication use for management of chronic constipation, including the secretagogue laxatives (lubiprostone and linaclotide), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), gabapentin or pregabalin, and opioids. There were no active drug trials for agents used in the management of chronic constipation during this time period at either institution.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was healthcare resource utilization, which was assessed by calculating total number of constipation-related visits (any type of visit with a billing diagnosis of constipation) and gastroenterology visits since the first billed constipation diagnosis in our system. These figures were adjusted for duration of follow-up from the first billed diagnosis of constipation to the most recent clinical contact, creating our outcome variable of number of visits or studies per year. To ensure accurate calculation of longitudinal healthcare burden, patients with less than 6 months of clinical follow up in our system were excluded.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were summarized using means and standard deviations for normally-distributed data and medians and inter-quartile ranges for non-normal data, while categorical variable were expressed as proportions. We compared characteristics of patients with outlet obstruction to those with no outlet obstruction, slow transit compared to normal transit, and high mean resting anal pressure compared to normal or low mean resting anal pressure. For the discrete outcomes, univariate comparisons were made using the Fisher's exact test and continuous outcomes were compared using a T-test or ANOVA for normally-distributed data and a rank-sum test for non-parametric data. As there are no accepted normal values for mean resting anal pressure in the literature (22-24), we used the overall mean pressure to categorize our cohort into ‘low’ and ‘high’ groups with separate cut-off values for water-perfusion and high-resolution studies.

Since healthcare resource utilization is right-skewed with most observations at lower values and a long tail to the right, we used non-parametric statistical techniques (rank-sum test) to compare unadjusted number of visits or studies per year between various patient subpopulations. We used multivariate linear regression to estimate the association between physiologic parameters and the number of annual constipation-related visits and gastroenterology since the first billed constipation diagnosis in our system. Because of the right-skew in our outcomes, they were log-transformed before regression. Due to this, the antilog of the parameters of the linear regression model can be interpreted as the fold increase in utilization between the two groups being compared. Covariates were selected for the multivariate model based on significance on univariate analysis at P <0.05 or clinical experience and consistent prior data supporting their association.

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS Version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Statistical significance was defined by a two-sided p-value of 0.05. All authors had access to the study data and reviewed and approved the final manuscript. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Massachusetts General Hospital and Brigham and Women's Hospital (Protocol# 2014P001465).

RESULTS

We identified a total of 1,025 patients who underwent anorectal manometry at Massachusetts General Hospital or Brigham and Women's Hospital for chronic idiopathic constipation between February 2000 and August 2014. Of these, 612 patients underwent both balloon expulsion testing and colonic transit testing and were included in our analysis (Figure 1). Patients who underwent both types of testing were less likely to be prescribed secretagogue laxatives (3.2% vs. 7.8%; P=0.04) but were otherwise similar in all clinical parameters assessed to those who underwent ARM alone with no transit study. Our cohort included 95 (15.5%) who underwent water-perfusion anorectal manometry and 517 (84.5%) who underwent high-resolution anorectal manometry.

Figure 1.

Study flow chart showing excluded patient groups

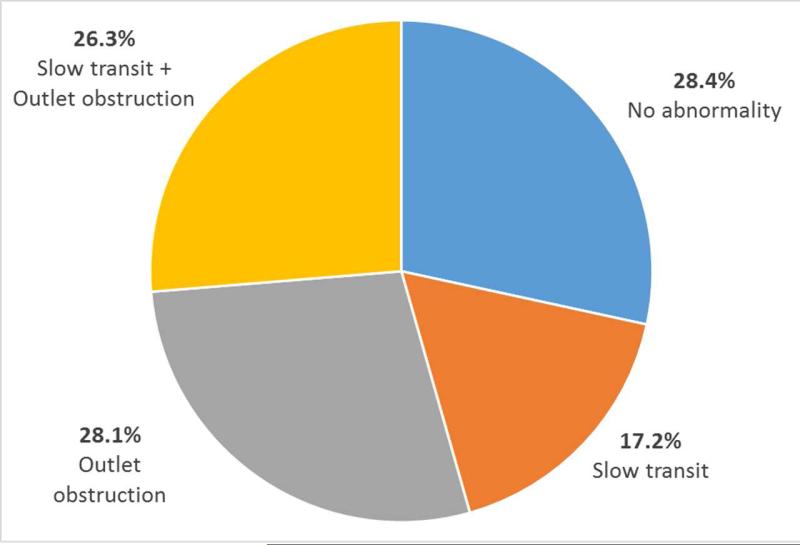

Our cohort was predominantly white (n=504, 82.5%) and female (n=524, 85.6%). Only 72 patients (11.8%) carried a concomitant diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome. Figure 2 describes the spectrum of abnormalities by balloon expulsion testing and colonic transit studies in our cohort. The most common abnormality was outlet obstruction by balloon expulsion testing which was seen in 54.4% of patients (n=333). Among these, slightly less than half had concomitant slow transit (n=161, 48.4%). A total of 105 patients (17.2%) had isolated slow transit. One-third (174 patients) of our sample had no physiologic abnormality detected by balloon expulsion testing or colonic transit assessment. Of the 100 anorectal manometry procedures performed at BWH, 27 were paired with transit studies and were included in the analysis.

Figure 2.

Spectrum of physiologic abnormalities in chronic constipation cohort by high-resolution anorectal manometry and colonic transit testing.

Table 1 compares the characteristics of patients with outlet obstruction against those without. There was no significant difference in sex, age of presentation, or medical comorbidities between the groups. Patients with outlet obstruction had similar likelihood of being prescribed SSRIs (13.5% vs. 11.8%, P=0.55), TCAs (1.2% vs. 1.8%, P=0.74), or prescription secretagogue laxatives (9.6% vs. 9.3%, P=1.00) and were more likely to have been prescribed opioids (18.6% vs. 12.5%, P=0.05) than those without outlet obstruction. They were also more likely to have slow colonic transit (48.4% vs. 37.6%, P=0.009). Although mean resting anal pressure was similar between both groups, patients with outlet obstruction had a significantly greater negative rectoanal gradient (−42.3 ± 59.1 mmHg vs. −22.4 ± 41.9 mmHg; P=0.003) and lower defecatory index (0.57 ± 0.77 vs. 0.86 ± 0.70; P=0.003) compared to those without outlet obstruction. Sensory thresholds for first sensation, urge to defecate, and maximum tolerated volume were also significantly greater in patients with outlet obstruction compared to those without.

Table 1.

Characteristics of chronic constipation subjects with outlet obstruction compared to those with no outlet obstruction

| Characteristic | Outlet obstruction | No outlet obstruction | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 333 (54.4) | 279 (45.6) | ------- |

| Female sex (%) | 284 (85.3) | 240 (86.0) | 0.81 |

| Race | 0.02 b | ||

| White (%) | 263 (79.2) | 241 (86.4) | ------- |

| Black (%) | 32 (9.6) | 11 (3.9) | ------- |

| Other (%) | 37 (11.1) | 27 (9.7) | ------- |

| Mean age of presentation (SD) | 42.9 (16.0) | 45.1 (17.3) | 0.09 |

| Mean Charlson score (SD) | 0.47 (1.04) | 0.53 (1.01) | 0.43 |

| Irritable bowel syndrome (%) | 35 (10.5) | 37 (13.3) | 0.32 |

| Fibromyalgia (%) | 16 (4.8) | 16 (5.7) | 0.72 |

| Anxiety (%) | 51 (15.3) | 42 (15.1) | 1.00 |

| Depression (%) | 74 (22.2) | 69 (24.7) | 0.50 |

| Substance Abuse (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.00 |

| SSRI use (%) | 45 (13.5) | 33 (11.8) | 0.55 |

| Tricyclic antidepressant use (%) | 4 (1.2) | 5 (1.8) | 0.74 |

| Gabapentin use (%) | 20 (6.0) | 18 (6.5%) | 0.87 |

| Opiate use (%) | 62 (18.6) | 35 (12.5) | 0.05 |

| Prescription secretagogue use (SD) | 32 (9.6) | 26 (9.3) | 1.00 |

| ------- | |||

| Slow colonic transit (%) | 161 (48.4) | 105 (37.6) | 0.009 |

| ------- | |||

| Mean resting anal pressure (SD) | 77.8 (45.5) mmHg | 78.1 (41.9) mmHg | 0.93 |

| Mean rectoanal gradient (SD) | −42.3 (59.1) | −22.4 (57.6) | 0.003 |

| Mean defecatory index (SD) | 0.57 (0.77) | 0.86 (0.70) | 0.003 |

| Absent rectoanal inhibitory reflex (%) | 12 (3.8) | 6 (2.2) | 0.34 |

| ------- | |||

| Sensory: mean volume of first sensation (SD) | 61.8 (38.3) mL | 46.7 (34.5) mL | <0.001 |

| Sensory: mean volume of urge to defecate (SD) | 118.4 (58.9) mL | 86.5 (37.9) mL | <0.001 |

| Sensory: maximum tolerated volume (SD) | 203.0 (88.1) mL | 170.2 (73.8) mL | <0.001 |

a. For continuous variables normally-distributed values are presented with standard deviations (SD).

P-value is for analysis of variance (ANOVA) comparing racial breakdown between the two groups

Table 2 compares the characteristics of patients with slow transit against those without. Patients with slow-transit constipation were more likely to be female, white and have co-morbid depression. They were more likely to have a prescription for secretagogue laxatives (14.3% vs. 5.8%, P<0.001) or opioids (20.3% vs. 12.4%, P=0.01). Patients with slow colonic transit were more likely to have a prolonged balloon expulsion time/outlet obstruction (60.5% vs. 49.7%, P=0.009). The mean resting anal pressure was 13.8 mm Hg lower among patients with slow-transit constipation compared to those with constipation and normal transit (P<0.001), but other anorectal pressure and sensory parameters were not statistically significant between normal and slow colonic transit groups.

Table 2.

Characteristics of chronic constipation subjects with slow colonic transit compared to those with normal colonic transit

| Characteristic | Slow transit | Normal transit | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 266 (43.5) | 346 (46.5) | ------- |

| Female sex (%) | 239 (89.9) | 285 (82.4) | 0.01 |

| Race | 0.007 b. | ||

| White (%) | 228 (86.8) | 276 (79.8) | ------- |

| Black (%) | 21 (7.9) | 22 (6.4) | ------- |

| Other (%) | 16 (6.0) | 48 (13.9) | ------- |

| Mean age of presentation (SD) | 44.6 (16.4) | 43.3 (16.9) | 0.35 |

| Mean Charlson score (SD) | 0.57 (1.13) | 0.44 (0.94) | 0.12 |

| Irritable bowel syndrome (%) | 27 (10.2) | 45 (13.0) | 0.31 |

| Fibromyalgia (%) | 15 (5.6) | 17 (4.9) | 0.72 |

| Anxiety (%) | 42 (15.8) | 51 (14.7) | 0.73 |

| Depression (%) | 74 (27.8) | 69 (19.9) | 0.03 |

| Substance Abuse (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.00 |

| SSRI use (%) | 41 (15.4) | 37 (10.7) | 0.09 |

| Tricyclic antidepressant use (%) | 3 (1.1) | 6 (1.7) | 0.74 |

| Gabapentin use (%) | 20 (7.5) | 18 (5.2) | 0.24 |

| Opioid use (%) | 54 (20.3) | 43 (12.4) | 0.01 |

| Prescription secretagogue use (%) | 38 (14.3) | 20 (5.8) | <0.001 |

| ---------- | |||

| Prolonged balloon expulsion time (%) | 161 (60.5) | 172 (49.7) | 0.009 |

| ---------- | |||

| Mean resting anal pressure (SD) | 70.1 (43.9) mmHg | 83.9 (42.8) mmHg | <0.001 |

| Mean rectoanal gradient (SD) | −34.9 (61.4) | −33.4 (58.3) | 0.85 |

| Mean defecatory index (SD) | 0.69 (0.78) | 0.72 (0.73) | 0.74 |

| Absent rectoanal inhibitory reflex (%) | 8 (3.2) | 10 (3.0) | 1.00 |

| ---------- | |||

| Sensory: mean volume of first sensation (SD) | 56.9 (39.6) mL | 53.4 (35.5) mL | 0.25 |

| Sensory: mean volume of urge to defecate (SD) | 105.1 (60.6) mL | 100.9 (45.7) mL | 0.54 |

| Sensory: maximum tolerated volume (SD) | 186.0 (85.6) mL | 188.3 (88.4) mL | 0.74 |

a. For continuous variables normally-distributed values are presented with standard deviations (SD).

P-value is for analysis of variance (ANOVA) comparing racial breakdown between the two groups

Table 3 compares characteristics of patients with a high mean resting anal pressure (greater than 62.4 mmHg for water-perfusion manometry and 78.6 mmHg for high-resolution manometry) to patients with a low mean resting anal pressure. Patients with high resting pressures were more likely to be younger with a similar distribution of comorbidities. They were also less likely to be prescribed opioids (11.5% vs. 18.4%, P=0.02) or have slow colonic transit (32.1% vs. 49.4%, P<0.001). The rectoanal gradient was 39.7 mmHg more negative (P<0.001) and the defecatory index lower (P=0.001) in patients with high resting anal pressures compared to those with normal pressures. Sensory thresholds were unchanged.

Table 3.

Characteristics of chronic constipation subjects with high mean resting anal pressure compared to low mean resting anal pressure

| Characteristic | High mean resting anal pressureb. | Low mean resting anal pressureb. | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 227 (37.0) | 385 (62.9) | ------- |

| Female sex (%) | 188 (82.8) | 336 (87.3) | 0.15 |

| Race | 0.08c. | ||

| White (%) | 178 (78.4) | 326 (84.7) | ------- |

| Black (%) | 22 (9.7) | 21 (5.5) | ------- |

| Other (%) | 27 (11.9) | 37 (9.6) | ------- |

| Mean age of presentation (SD) | 38.6 (16.3) | 47.0 (16.1) | <0.001 |

| Mean Charlson score (SD) | 0.3 (0.8) | 0.6 (1.1) | 0.003 |

| Irritable bowel syndrome (%) | 30 (13.2) | 42 (10.9) | 0.44 |

| Fibromyalgia (%) | 11 (9.3) | 21 (5.5) | 0.85 |

| Anxiety (%) | 31 (13.7) | 62 (16.1) | 0.48 |

| Depression (%) | 44 (19.4) | 99 (25.7) | 0.08 |

| Substance Abuse (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.00 |

| SSRI use (%) | 32 (14.1) | 49 (11.9) | 0.45 |

| Tricyclic antidepressant use (%) | 3 (1.3) | 6 (1.6) | 1.00 |

| Gabapentin use (%) | 13 (5.7) | 25 (6.5) | 0.73 |

| Opioid use (%) | 26 (11.5) | 71 (18.4) | 0.02 |

| Prescription secretagogue use (SD) | 19 (8.4) | 39 (10.1) | 0.57 |

| -------- | |||

| Slow colonic transit (%) | 73 (32.1) | 190 (49.4) | <0.001 |

| -------- | |||

| Prolonged balloon expulsion time (%) | 122 (53.7) | 210 (54.5) | 0.87 |

| -------- | |||

| Mean rectoanal gradient (SD) | −49.5 (62.4) | −9.8 (44.8) | <0.001 |

| Mean defecatory index (SD) | 0.59 (0.70) | 0.90 (0.77) | 0.001 |

| Absent rectoanal inhibitory reflex (%) | 9 (4.0) | 9 (2.3) | 0.33 |

| -------- | |||

| Sensory: mean volume of first sensation (SD) | 54.4 (39.2) mL | 55.2 (36.2) mL | 0.81 |

| Sensory: mean volume of urge to defecate (SD) | 103.3 (49.1) mL | 102.1 (53.9) mL | 0.86 |

| Sensory: maximum tolerated volume (SD) | 185.0 (80.8) mL | 188.9 (84.9) mL | 0.58 |

a. For continuous variables normally-distributed values are presented with standard deviations (SD).

Sample divided into ‘High’ and ‘Low’ by sample mean resting anal pressure (62.4 mmHg for water-perfusion manometry and 78.6 mmHg for high-resolution manometry)

P-value is for analysis of variance (ANOVA) comparing racial breakdown between the two groups

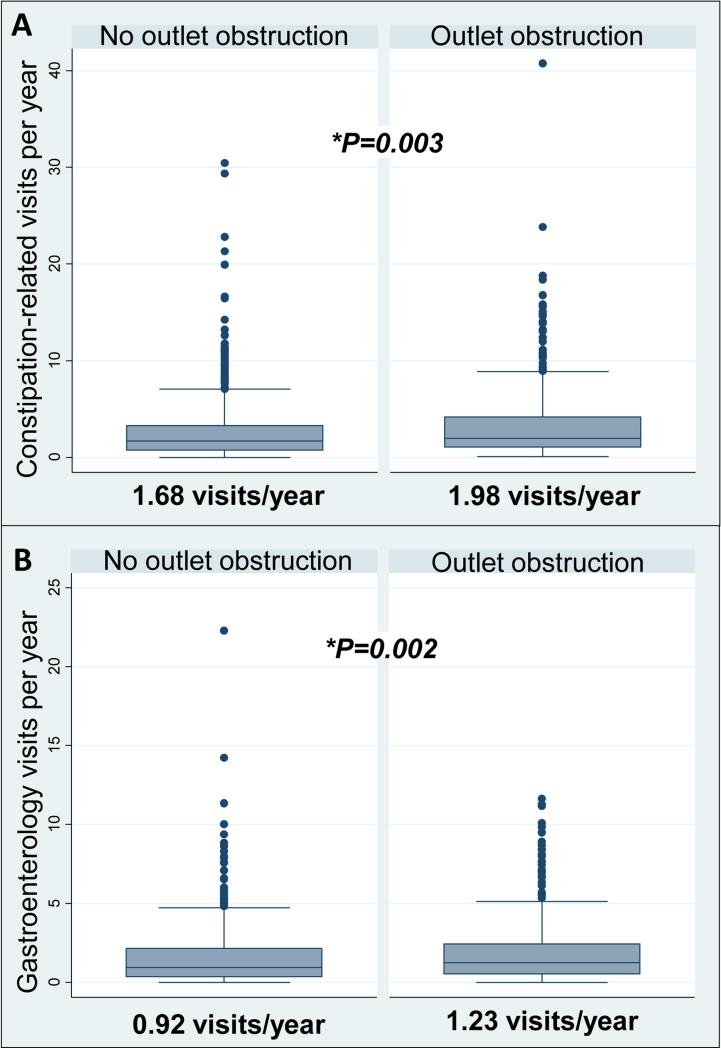

Healthcare resource utilization

In our primary analysis, patients with outlet obstruction had significantly-greater constipation-related visits per year and gastroenterology visits per year (Figure 3) compared to those without outlet obstruction. Patients with slow-transit constipation presented more frequently to healthcare providers with constipation-related complaints than those without slow transit, but there was no statistically significant difference between the number of gastroenterology visits per year (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Median constipation-related visits/year and gastroenterology visits/year stratified by presence of outlet obstruction on balloon expulsion testing. A. Constipation-related visits. B. Gastroenterology visits.

Figure 4.

Median constipation-related visits/year and gastroenterology visits/year stratified by presence of slow transit on radiopaque marker testing (≥ 5 markers 5 days after ingestion of 24 markers). A. Constipation-related visits. B. Gastroenterology visits.

Patients with a resting anal pressure greater than the mean for our sample (greater than 62.4 mmHg for water-perfusion manometry and 78.6 mmHg for high-resolution manometry) had significantly more constipation-related and gastroenterology visits/year than those with values below the mean (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Median constipation-related visits/year and gastroenterology visits/year stratified by high mean resting anal pressure (>64.4 mmHg on water-perfusion study or >78.6 mmHg on high-resolution anorectal manometry). A. Constipation-related visits. B. Gastroenterology visits.

Multivariate analysis – Predictors of high health care utilization

After adjustment for other clinically-relevant covariates on multiple linear regression analysis, high mean resting anal pressure was associated with yearly constipation-related visits (P=0.02) and gastroenterology visits (P=0.04) (Table 4). Slow colonic transit was associated with a significant decrease in constipation-related visits (P<0.01), but was not associated with gastroenterology visits. Both age of presentation (P=0.20 for constipation-related visits, P=0.47 for gastroenterology visits) and sex (P=0.65 for constipation-related visits, P=0.43 for gastroenterology visits) were not significantly-associated with healthcare utilization in our cohort.

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis for relationship between physiologic parameters on anorectal manometry and healthcare utilization measures in patient with chronic constipation

| Constipation-related visits | Gastroenterology visits | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Factor (fold increase) | 95% CI | P-value | Factor (fold increase) | 95% CI | P-value |

| High resting anal pressureb. | 1.23 | (1.04 - 1.45) | 0.02 | 1.20 | (1.00 - 1.43) | 0.04 |

| Outlet obstruction | 1.09 | (0.95 - 1.26) | 0.21 | 1.07 | (0.93 - 1.24) | 0.34 |

| Slow transit | 0.75 | (0.68 – 0.83) | <0.01 | 0.96 | (0.87 - 1.08) | 0.56 |

| Maximum tolerated volume on ARMc. | 1.00 | (1.00 - 1.00) | 0.32 | 1.00 | (1.00 - 1.00) | 0.94 |

a. Factors reflect multivariate linear regression analysis with adjustment for mean resting anal pressure, outlet obstruction, slow colonic transit, sex, age of presentation, race, Charlson comorbidity index score, diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome, fibromyalgia, depression, anxiety, or hypertension; selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use, tricyclic antidepressant use, opioid use, and use of prescription secretagogue laxatives

Factors represent fold increase in geometric mean of visits/year if mean resting anal pressure is > 62.4 mmHg on water-perfusion anorectal manometry or > 78.6 mmHg on high-resolution manometry

Represents maximum tolerated volume (causing discomfort) during anorectal manometry (ARM) with incremental rectal balloon inflation

Adjusting the results for center (MGH vs. BWH) or excluding patients with procedures performed at BWH had no effect on the aforementioned results.

A post-hoc analysis of predictors of high mean resting anal pressure using multivariate logistic regression demonstrated that lower age (P<0.01) and slow colonic transit (P<0.01) were associated with high mean resting anal pressure. There was no significant association between resting anal pressure and outlet obstruction on balloon expulsion testing (P=0.08). No other demographic, comorbidity, or medication was associated with high resting anal pressure. Additionally, the effect of mean resting anal pressure on healthcare utilization remained robust on adjusting for the above parameters.

DISCUSSION

In this retrospective analysis of a large cohort of 612 patients undergoing evaluation for chronic constipation at two tertiary academic centers, we found high mean resting anal pressure by anorectal manometry to be the single strongest physiologic predictor of healthcare resource utilization as measured by increased constipation-related visits and gastroenterology visits. We found no effect of anorectal outlet obstruction on resource utilization by these same metrics after adjusting for other determinants of healthcare-seeking behavior and slow colonic transit was associated with a decrease in constipation-related, but not gastroenterology visits. Interestingly, we also identified a significant overlap between the various physiologic parameters contributing to chronic constipation, namely slow transit, resting anal pressure, and outlet obstruction by balloon expulsion.

Our data identifying high resting anal pressure as an important predictor of health resource utilization is unique in connecting a physiologic parameter with a consumption metric rather than a clinical endpoint in chronic constipation and is, to our knowledge, the largest cohort of patients undergoing anorectal manometry for chronic constipation. Although clinicians may tend to focus on the results of balloon expulsion testing and colonic transit testing in their treatment decisions, our results suggesting a more complex interpretation of testing in constipation fit with the work of Ratuapli et al (25), who used principal components logistic modeling to identify manometric phenotypes in constipation. In their analysis, they found that high resting anal pressure (in combination with high pressures during evacuation) was likely a distinct pathophysiologic defect contributing to disordered defecation—a finding in line with the identification of Type 1 dyssynergia in earlier work by Rao et al (26).

Both of these studies suggested impaired anal relaxation as a pathophysiologic basis for anorectal dysfunction; however, our data showed no increased prevalence of impaired balloon expulsion testing in patients with higher resting anal pressures, suggesting an alternative mechanism for increased use of resources. Rather than a marker of disordered defecation alone, we would argue that elevated resting anal pressures may reflect heightened body vigilance, as has been noted in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and chronic pain (27, 28). Thus, patients with higher resting anal pressures may have increased awareness of visceral sensations and maladaptive responses to those sensations. Indeed, patients with bloating and abdominal distention are more likely to have an elevated resting anal pressure than those without distention (29). It is also possible that high resting anal pressure is a marker of patients complaining of constipation without a clear physiologic abnormality and their high resource utilization is reflective of a search for an adequate diagnosis and treatment in the absence of one.

These connections could suggest that our findings were influenced by the presence of patients with concomitant irritable bowel syndrome. However, only 11.8% of our cohort carried a diagnosis of IBS. Moreover, we did not see a relationship between lowered sensation thresholds on anorectal manometry which has been described with visceral hypersensitivity associated with IBS (30) and healthcare utilization, suggesting that other explanations may explain the association with resting anal pressure. However, we acknowledge that since a clinical diagnosis of IBS was not made using the widely accepted Rome criteria, there is potential for misclassification. Abdominal pain or discomfort is common in patients with chronic constipation not meeting criteria for IBS-C (31), and the distinctions between the two entities are increasingly blurred (32-34). Thus, it is plausible that patients with higher resting anal pressures may benefit from a multidisciplinary approach incorporating neuromodulatory and psychological therapies in addition to laxative agents and pelvic floor biofeedback, as has been shown to be efficacious in irritable bowel syndrome (35).

As our study used frequency of healthcare visits rather than clinical improvement as endpoints, the clinical consequences of high resting anal pressure should be interpreted with caution. Normal values for resting anal pressure and other anorectal manometry measurements have yet to be firmly established (36), with several analyses reporting variable results in healthy populations (22-24). The recent literature has primarily been focused on high-resolution values, and our high-resolution mean of 78.6 mmHg fits in line with the normal resting anal values from Noelting et al (88 mmHg for women >50 years and 63 for women ≤ 50 years)(24), is slightly higher than the values from Carrington et al (65 mmHg for women)(23), and substantially higher than the Korean data from Lee et al (32 mm Hg for women)(22). It should be noted that age, gender, and catheter diameter can all have effects on derived pressures (23), and we did not use normative values for age and gender in our resting pressure measurements, but did adjust for both age and sex in our multivariable analysis. Age and certainly sex can affect healthcare-seeking behavior (2, 3), but these factors were not significant in our cohort after adjusting for other confounders. Like other groups (37), we found significant overlap between those with outlet obstruction by balloon expulsion testing and slow transit, with slow transit perhaps a sequela of disordered defecation. Notably, patients in our cohort with high resting anal pressure were less likely to have concomitant slow transit and no more or less likely to have a prolonged balloon expulsion time. This suggests that patients with high resting anal pressures may be a distinct subset of patients with chronic constipation; however, we would not suggest that direct treatment of a hypertensive anal sphincter would be curative in this population. Interventional approaches to the treatment of anismus, including surgical division of the anal sphincter and botulinum injections have yielded inconsistent or negative results (38-41). Thus, a more multidisciplinary approach rather than a targeted intervention may be indicated. Additional studies on other measures of constipation severity including impact on health-related quality of life and patient-reported outcomes are essential to supplement our findings.

Among patients with impaired balloon expulsion, we found rectal hyposensitivity to be common, suggesting a possible role for hyposensitivity rather than hypersensitivity in the genesis of pelvic floor dysfunction (42). These heightened sensation thresholds were not seen in patients with slow transit or high resting anal pressures. Although a negative rectoanal pressure gradient (and corresponding defecatory index <1) is thought to be a marker of outlet dysfunction, our data fits with others in that the magnitude of the negative rectoanal differential more so than whether it is negative or positive corresponds to impaired balloon expulsion (24).

We acknowledge several limitations. Our study is observational and therefore we cannot exclude the effect of potential unmeasured confounders. That said, multivariate adjustment for known and putative risk factors of increased clinical utilization did not significantly alter our effect estimates. As all patients who were included had both colonic transit testing and ARM at two tertiary care centers, our findings may represent more severe cases of constipation that are less generalizable to the population at large. Nevertheless, our findings could be informative for patients who are undergoing a physiologic workup for constipation. Additionally, including patients with comprehensive testing reduced likelihood of misclassification when compared to studies using colonic transit time or outlet dysfunction alone as predictors. Our findings of a significant overlap between the various subgroups of chronic constipation suggest such comprehensive evaluation is important to truly identify the main determinant of patient outcomes. With multiple observers over two institutions, there may be inter-individual variation in the interpretation of anorectal manometry and thus differences in resting anal pressure measurements. However, the multicenter cohort lends itself to be more generalizable findings that are less likely to be biased due to a single reader. Extrapolating the results of anorectal manometry and balloon expulsion testing in isolation should be done with caution, as no single test is sufficiently specific (5), and the individual measured parameters of anorectal manometry are highly-correlated (25). That said, ballon expulsion testing has been shown to be highly correlated with the findings of anorectal manometry and rectal electromyography (17). Additionally, our measures of treatment (SSRI use, TCA use, secretagogue laxative use) are not time-dependent, we could not account for the use of biofeedback for pelvic floor physical therapy, and we had no information on anatomic defects of the anorectum.

The current study has several notable strengths. Most significantly, it benefited from a large sample size comprised of patients undergoing both anorectal function and colonic transit testing at two institutions. The incorporation of known and putative predictors of both constipation and resource utilization into our multivariate model shows that the relationship between resting anal pressure and healthcare seeking is not subtle. Our finding that high mean resting anal pressure directly correlates with increased healthcare utilization as measured by frequency of constipation-related visits and gastroenterology visits in patients evaluated for chronic constipation adds a unique perspective to the interpretation of anorectal manometry in clinical practice. We found high resting anal pressures to be more influential on healthcare-seeking behavior than either outlet obstruction as measured by balloon expulsion testing and slow colonic transit by radiopaque marker study.

By identifying those with higher resting anal pressures on anorectal manometry, we suggest that clinicians may be able to target these patients for more intensive, multidisciplinary treatments that account for psychological as well as transit and defecatory dysfunction. A well-designed, prospective study evaluating the connection between resting anal pressure and disease severity, quality of life, and patient-reported outcomes would be useful in determining the true role of resting anal pressure in the physiology of chronic constipation.

KEY MESSAGES.

There is little data on physiologic parameters of healthcare utilization among patients with chronic constipation.

We analyzed the relationship between physiologic parameters obtained via anorectal manometry and colonic transit testing and healthcare utilization.

We found that only high resting anal pressure was associated with increased healthcare utilization after multivariable adjustment.

Among patients with chronic constipation, high resting anal pressure, rather than outlet obstruction or slow transit, is the best predictor of healthcare resource utilization suggesting these patients represent a distinct subset of constipated patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

FUNDING A. Ananthakrishnan is supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (K23 DK097142).

Footnotes

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT

Guarantor of article: K Staller

Specific author contributions:

Kyle Staller and Ashwin Ananthakrishnan planned and designed the study and analyzed the data; Kyle Staller and Kenneth Barshop collected the data; Kyle Staller drafted the manuscript; all authors interpreted the results and contributed to critical review of the manuscript; Kyle Staller had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Kyle Staller had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

All authors approved the final version of the article, including the authorship list.

DISCLOSURES

B Kuo and has received research funding from Vibrant. A Ananthakrishnan, K Barshop, and K Staller report no disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bharucha AE, Pemberton JH, Locke GR., 3rd. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on constipation. Gastroenterology. 2013;144(1):218–38. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pare P, Ferrazzi S, Thompson WG, Irvine EJ, Rance L. An epidemiological survey of constipation in canada: definitions, rates, demographics, and predictors of health care seeking. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(11):3130–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.05259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galvez C, Garrigues V, Ortiz V, Ponce M, Nos P, Ponce J. Healthcare seeking for constipation: a population-based survey in the Mediterranean area of Spain. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics. 2006;24(2):421–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neri L, Basilisco G, Corazziari E, Stanghellini V, Bassotti G, Bellini M, et al. Constipation severity is associated with productivity losses and healthcare utilization in patients with chronic constipation. United European gastroenterology journal. 2014;2(2):138–47. doi: 10.1177/2050640614528175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wald A, Bharucha AE, Cosman BC, Whitehead WE. ACG clinical guideline: management of benign anorectal disorders. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2014;109(8):1141–57. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.190. (Quiz) 058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rao SS, Valestin J, Brown CK, Zimmerman B, Schulze K. Long-term efficacy of biofeedback therapy for dyssynergic defecation: randomized controlled trial. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2010;105(4):890–6. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiarioni G, Whitehead WE, Pezza V, Morelli A, Bassotti G. Biofeedback is superior to laxatives for normal transit constipation due to pelvic floor dyssynergia. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(3):657–64. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heymen S, Scarlett Y, Jones K, Ringel Y, Drossman D, Whitehead WE. Randomized, controlled trial shows biofeedback to be superior to alternative treatments for patients with pelvic floor dyssynergia-type constipation. Diseases of the colon and rectum. 2007;50(4):428–41. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0814-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schey R, Rao SS. Lubiprostone for the treatment of adults with constipation and irritable bowel syndrome. Digestive diseases and sciences. 2011;56(6):1619–25. doi: 10.1007/s10620-011-1702-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lembo AJ, Schneier HA, Shiff SJ, Kurtz CB, MacDougall JE, Jia XD, et al. Two randomized trials of linaclotide for chronic constipation. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;365(6):527–36. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1010863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bouras EP, Camilleri M, Burton DD, Thomforde G, McKinzie S, Zinsmeister AR. Prucalopride accelerates gastrointestinal and colonic transit in patients with constipation without a rectal evacuation disorder. Gastroenterology. 2001;120(2):354–60. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cinca R, Chera D, Gruss HJ, Halphen M. Randomised clinical trial: macrogol/PEG 3350+electrolytes versus prucalopride in the treatment of chronic constipation -- a comparison in a controlled environment. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics. 2013;37(9):876–86. doi: 10.1111/apt.12278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dipalma JA, Cleveland MV, McGowan J, Herrera JL. A randomized, multicenter, placebo-controlled trial of polyethylene glycol laxative for chronic treatment of chronic constipation. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2007;102(7):1436–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guerin A, Carson RT, Lewis B, Yin D, Kaminsky M, Wu E. The economic burden of treatment failure amongst patients with irritable bowel syndrome with constipation or chronic constipation: a retrospective analysis of a Medicaid population. Journal of medical economics. 2014:1–10. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2014.919926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nalichowski R, Keogh D, Chueh HC, Murphy SN. Calculating the benefits of a Research Patient Data Repository. AMIA Annual Symposium proceedings / AMIA Symposium AMIA Symposium. 2006:1044. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rao SS, Azpiroz F, Diamant N, Enck P, Tougas G, Wald A. Minimum standards of anorectal manometry. Neurogastroenterology and motility : the official journal of the European Gastrointestinal Motility Society. 2002;14(5):553–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2982.2002.00352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chiarioni G, Kim SM, Vantini I, Whitehead WE. Validation of the Balloon Evacuation Test: Reproducibility and Agreement With Findings From Anorectal Manometry and Electromyography. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hinton JM, Lennard-Jones JE, Young AC. A new method for studying gut transit times using radioopaque markers. Gut. 1969;10(10):842–7. doi: 10.1136/gut.10.10.842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. Journal of chronic diseases. 1987;40(5):373–83. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Charlson ME, Charlson RE, Peterson JC, Marinopoulos SS, Briggs WM, Hollenberg JP. The Charlson comorbidity index is adapted to predict costs of chronic disease in primary care patients. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2008;61(12):1234–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bouchoucha M, Hejnar M, Devroede G, Boubaya M, Bon C, Benamouzig R. Patients with irritable bowel syndrome and constipation are more depressed than patients with functional constipation. Digestive and liver disease : official journal of the Italian Society of Gastroenterology and the Italian Association for the Study of the Liver. 2014;46(3):213–8. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2013.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee HJ, Jung KW, Han S, Kim JW, Park SK, Yoon IJ, et al. Normal values for high-resolution anorectal manometry/topography in a healthy Korean population and the effects of gender and body mass index. Neurogastroenterology and motility : the official journal of the European Gastrointestinal Motility Society. 2014;26(4):529–37. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carrington EV, Brokjaer A, Craven H, Zarate N, Horrocks EJ, Palit S, et al. Traditional measures of normal anal sphincter function using high-resolution anorectal manometry (HRAM) in 115 healthy volunteers. Neurogastroenterology and motility : the official journal of the European Gastrointestinal Motility Society. 2014;26(5):625–35. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Noelting J, Ratuapli SK, Bharucha AE, Harvey DM, Ravi K, Zinsmeister AR. Normal values for high-resolution anorectal manometry in healthy women: effects of age and significance of rectoanal gradient. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2012;107(10):1530–6. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ratuapli SK, Bharucha AE, Noelting J, Harvey DM, Zinsmeister AR. Phenotypic identification and classification of functional defecatory disorders using high-resolution anorectal manometry. Gastroenterology. 2013;144(2):314–22 e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.10.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rao SS, Mudipalli RS, Stessman M, Zimmerman B. Investigation of the utility of colorectal function tests and Rome II criteria in dyssynergic defecation (Anismus). Neurogastroenterology and motility : the official journal of the European Gastrointestinal Motility Society. 2004;16(5):589–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2004.00526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keough ME, Timpano KR, Zawilinski LL, Schmidt NB. The association between irritable bowel syndrome and the anxiety vulnerability factors: body vigilance and discomfort intolerance. Journal of health psychology. 2011;16(1):91–8. doi: 10.1177/1359105310367689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCracken LM. A contextual analysis of attention to chronic pain: what the patient does with their pain might be more important than their awareness or vigilance alone. The journal of pain : official journal of the American Pain Society. 2007;8(3):230–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shim L, Prott G, Hansen RD, Simmons LE, Kellow JE, Malcolm A. Prolonged balloon expulsion is predictive of abdominal distension in bloating. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2010;105(4):883–7. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Piche M, Arsenault M, Poitras P, Rainville P, Bouin M. Widespread hypersensitivity is related to altered pain inhibition processes in irritable bowel syndrome. Pain. 2010;148(1):49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ford AC, Bercik P, Morgan DG, Bolino C, Pintos-Sanchez MI, Moayyedi P. Characteristics of functional bowel disorder patients: a cross-sectional survey using the Rome III criteria. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39(3):312–21. doi: 10.1111/apt.12573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rey E, Balboa A, Mearin F. Chronic constipation, irritable bowel syndrome with constipation and constipation with pain/discomfort: similarities and differences. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2014;109(6):876–84. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shekhar C, Monaghan PJ, Morris J, Issa B, Whorwell PJ, Keevil B, et al. Rome III functional constipation and irritable bowel syndrome with constipation are similar disorders within a spectrum of sensitization, regulated by serotonin. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(4):749–57. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.07.014. quiz e13-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cremonini F, Lembo A. IBS with constipation, functional constipation, painful and non-painful constipation: e Pluribus...Plures? The American journal of gastroenterology. 2014;109(6):885–6. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ford AC, Quigley EM, Lacy BE, Lembo AJ, Saito YA, Schiller LR, et al. Effect of antidepressants and psychological therapies, including hypnotherapy, in irritable bowel syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(9):1350–65. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.148. quiz 66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carrington EV, Grossi U, Knowles CH, Scott SM. Normal values for high- resolution anorectal manometry: a time for consensus and collaboration. Neurogastroenterology and motility : the official journal of the European Gastrointestinal Motility Society. 2014;26(9):1356–7. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chiarioni G, Salandini L, Whitehead WE. Biofeedback benefits only patients with outlet dysfunction, not patients with isolated slow transit constipation. Gastroenterology. 2005;129(1):86–97. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maria G, Cadeddu F, Brandara F, Marniga G, Brisinda G. Experience with type A botulinum toxin for treatment of outlet-type constipation. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2006;101(11):2570–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pfeifer J, Agachan F, Wexner SD. Surgery for constipation: a review. Diseases of the colon and rectum. 1996;39(4):444–60. doi: 10.1007/BF02054062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roe AM, Bartolo DC, Mortensen NJ. Diagnosis and surgical management of intractable constipation. The British journal of surgery. 1986;73(10):854–61. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800731031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wald A. Outlet Dysfunction Constipation. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2001;4(4):293–7. doi: 10.1007/s11938-001-0054-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gladman MA, Scott SM, Chan CL, Williams NS, Lunniss PJ. Rectal hyposensitivity: prevalence and clinical impact in patients with intractable constipation and fecal incontinence. Diseases of the colon and rectum. 2003;46(2):238–46. doi: 10.1097/01.DCR.0000044711.76085.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]