Abstract

Tissue engineering strategies have emerged in response to the growing prevalence of chronic musculoskeletal conditions, and many of these regenerative methods are currently being evaluated in translational animal models. Engineered replacements for fibrous tissues such as the meniscus, annulus fibrosus, tendons, and ligaments are subjected to challenging physiologic loads, and are difficult to track in vivo using standard techniques. The diagnosis and treatment of musculoskeletal conditions depends heavily on radiographic assessment, and a number of currently available implants utilize radiopaque markers to facilitate in vivo imaging. In this study, we developed a nanofibrous scaffold in which individual fibers included radiopaque nanoparticles. Inclusion of radiopaque particles increased the tensile modulus of the scaffold and imparted radiation attenuation within the range of cortical bone. When scaffolds were seeded with bovine mesenchymal stem cells in vitro, there was no change in cell proliferation and no evidence of promiscuous conversion to an osteogenic phenotype. Scaffolds were implanted ex vivo in a model of a meniscal tear in a bovine joint and in vivo in a model of total disc replacement in the rat coccygeal spine (tail), and were visualized via fluoroscopy and microcomputed tomography. In the disc replacement model, histological analysis at 4 weeks showed that the scaffold was biocompatible and supported the deposition of fibrous tissue in vivo. Thus, nanofibrous scaffolds including radiopaque nanoparticles provide a biocompatible template with sufficient radiopacity for in vivo visualization in both small and large animal models. This radiopacity may facilitate image-guided implantation and non-invasive long-term evaluation of scaffold location and performance.

Keywords: Tissue Engineering, Electrospinning, Intervertebral Disc, Imaging, Radiography

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

The healing capacity of musculoskeletal tissues like the intervertebral disc, meniscus, tendon, and ligament is limited, and injury or degeneration of these tissues compromises the standard of living of millions in the US [1]. While there are a number of surgical approaches for repairing diseased or damaged fibrous musculoskeletal tissues, each of these are associated with significant limitations. For example, partial meniscectomy may be indicated for tears in the avascular region of the meniscus. While in many cases this procedure provides relief of pain and mechanical symptoms, it accelerates osteoarthritis due to altered load transmission in the knee [2] and its long-term efficacy is uncertain [3]. Spinal fusion is often performed for segmental instability resulting in stenosis or radiculopathy in the presence of a collapsed or bulging intervertebral disc. While many patients have positive outcomes following fusion, alterations in spinal kinematics after fusion are associated with accelerated degeneration of adjacent discs [4]. Rotator cuff repair is commonly performed for pain and weakness resulting in compromised upper extremity function. However, the poor healing capacity of degenerated rotator cuff tendons and high tensile loads due to tendon retraction impair healing at the bone-tendon interface [5]. For these reasons, engineering fibrous musculoskeletal tissues from cells and various natural and artificial materials has emerged as a strategy to improve the outcomes of the above procedures. In particular, tissue engineering repair strategies for disc, meniscus, tendon and ligament have transitioned over the past decade from in vitro [6–9] to in vivo [10–13] evaluation using a variety of animal models, and the clinical application of these emerging technologies is imminent.

Engineered fibrous tissues must meet specific design criteria related to their physical characteristics in order to effectively resist, dissipate, and transfer mechanical loads during normal daily activities. Fibrous musculoskeletal structures resist multidirectional loading by dissipating energy through collagen fibers and inter-fibrillar matrix, and, in order to ensure proper functional performance, engineered tissues must not only withstand physiologic loading and motion, but also must integrate into adjacent native tissues. In vivo visualization of engineered tissues would be a powerful method to track and confirm the performance in situ, however, the composition of most scaffold materials does not allow for visualization by methods available to clinicians (e.g., radiography).

Visualization by fluoroscopy and radiography is routinely performed for the diagnosis of musculoskeletal conditions, surgical planning, intraoperative guidance, and postoperative assessment. Total joint replacement prostheses and fracture fixation implants have characteristic radiographic profiles due to their radiopaque components; radiopaque markers in interbody prosthetic devices for spinal fusion allow for image-guided placement and long-term confirmation of position; radiopaque bone cements derived from methyl methacrylates and heavy metal/ceramic radiopacifiers are currently used for the fixation of prostheses and in the augmentation of vertebral compression fractures. Enabling similar visualization of engineered fibrous musculoskeletal tissues is very important for repairing tissues that are subject to physiological loads and resultant deformations, as it would improve intraoperative positioning and allows post-operative tracking of scaffold location, integration and remodeling.

Electrospun scaffolds are currently being evaluated for a number of fibrous tissue engineering applications, including repair of the annulus fibrosus of the intervertebral disc [14, 15], the knee meniscus [16, 17], tendons [18–20], and ligaments [21, 22]. As these scaffolds are typically radiolucent, we developed a radiopaque nanofibrous scaffold by electrospinning a polymer/ceramic nanopowder solution [11]. Scaffolds were produced with aligned fibers to provide a template for cell attachment and to orient newly formed collagenous matrix [23, 24].

To impart radiopacity, we included radiodense nanoparticles within each fiber. In this study, we characterized the structure, radiation attenuation, and mechanical behavior of these scaffolds as a function of nanoparticle density, as well as the behavior of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) seeded on the scaffolds. We further evaluated these materials in situ in the bovine knee for applications in meniscus repair and in vivo in a rat model of total intervertebral disc replacement.

2. Methods

2.1. Scaffold Fabrication

Radiopaque scaffolds were generated from a solution of poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL, Shenzhen BrightChina Industrial Co., Hong Kong, China) mixed with radiodense zirconium(IV) oxide nanoparticles (Zirconia, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Zirconia particles have a characteristic dimension of <100 nm, allowing for their complete encapsulation within PCL fibers that typically have a diameter greater than 300 nm [25]. PCL and zirconia were dissolved in a 1:1 mixture of tetrahydrofuran (THF) and N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) (Fisher Chemical, Fairlawn, NJ) and the slurry was extruded at a rate of 2.5 mL/hour through a 15–20 kV-charged 18G needle while continuously mixed with a magnetic stirrer. Fibers were drawn across a 15 cm air gap onto a grounded mandrel rotating with a surface velocity of 10 m/s to create aligned nanofibrous sheets (thickness = 200μm). Four scaffold-types with varying zirconia concentration were fabricated with PCL/zirconia mass ratios of either 50%/50%, 75%/25%, 90%/10%, or 100%/0% [Table 1, Fig. 1]. In each case, the solution concentration was 14.3 g of PCL/zirconia in 100 mL of THF/DMF (14.3% w/v [26]).

Table 1.

Composition of solutions used to produce electrospun scaffolds

| Scaffold | % PCL by mass | % Zirconia by mass | PCL mass (g) | Zirconia mass (g) | THF volume (mL) | DMF volume (mL) | % w/v |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 100 | 0 | 14.3 | 0 | 50 | 50 | 14.3 |

| 2 | 90 | 10 | 12.9 | 1.4 | 50 | 50 | 14.3 |

| 3 | 75 | 25 | 10.7 | 3.6 | 50 | 50 | 14.3 |

| 4 | 50 | 50 | 7.15 | 7.15 | 50 | 50 | 14.3 |

Figure 1. Electrospun radiopaque scaffold.

Radiopaque scaffolds were generated by electrospinning a mixture of PCL, a biocompatible polymer with long term in vivo stability, and zirconia, a ceramic nanopowder. The slurry was continuously mixed with a magnetic stirrer and collected onto a rotating mandrel to produce aligned nanofibrous sheets. Four different scaffold formulations were produced: 100% PCL scaffold, 90% PCL/10% zirconia scaffold, 75% PCL/25% zirconia scaffold, and 50% PCL/50% zirconia scaffold.

2.2. Scaffold Characterization

Each scaffold was assayed for structural continuity, radiodensity and mechanical properties. To assess scaffold nanostructure, samples were cut from freshly spun mats, sputter coated, and imaged at 2,000X and 10,000X magnification on a scanning electron microscope (SEM; 6400, JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) with an accelerating voltage of 10 kV. To measure radiodensity, 8 mm diameter samples were punched from each scaffold and scanned by microcomputed tomography (μCT; vivaCT 75, SCANCO Medical AG, Bruttisellen, Switzerland) at 20.5 μm resolution (n=5/group). The linear attenuation coefficient (volumetric average radiation attenuation) of each sample was calculated from volumetric reconstructions of the punched samples and then converted to Hounsfield Units (HU) by normalizing values to the attenuation of water. Scaffold radiation attenuation was directly compared to that of cortical bone in order to assess the potential for in situ visualization. To measure scaffold mechanical properties, scaffold strips (5 mm × 40 mm) were tested in uniaxial tension parallel to the fiber orientation using an electromechanical testing system (5542, Instron, Norwood, MA) (n=5/group). The testing protocol consisted of a 0.05 N preload followed by extension to failure at a rate of 0.1% strain/sec. The linear region tensile modulus was calculated as described previously [26].

2.3. In Situ Evaluation in the Bovine Meniscus

To determine whether scaffolds had radiation attenuation suitable for visualization in joints with dimensions similar in scale to human joints, a radiopaque scaffold was implanted ex vivo into the medial meniscus of a juvenile bovine stifle joint and imaged with a fluoroscope (HD, Orthoscan Inc., Scottsdale, AZ). To do so, a medial parapatellar incision was made through the joint capsule, the anterior cruciate ligament was transected, and a circumferential incision was made in the medial meniscus, mimicking the location and shape of a bucket handle tear similar to those we and others have used in animal models [27]. The radiopaque scaffold was prepared from 50% zirconia/50% PCL solution at a thickness of 500 μm. Strips of dimensions 3 mm by 30 mm were layered into a stack of 8 and welded together with a soldering pencil. The layered scaffold was inserted into the bucket handle tear and tethered to the meniscus with 4–0 suture. The synovium and fascia were then closed with suture and anterior-posterior and medial-lateral fluoroscopic images were acquired. After this preliminary imaging, the meniscus was removed en bloc, soaked for 72 hours in Lugol’s solution (Sigma-Aldrich) to enhance the radiocontrast of the meniscal tissue, and imaged via μCT at 20.5 μm resolution for visualization of both the contrast-enhanced meniscus and the radiopaque scaffold.

2.4. In Vitro Assessment of Cytocompatibility and Osteogenic Potential

To determine whether radiopaque scaffolds were cytocompatible, scaffolds were seeded with juvenile bovine bone marrow-derived MSCs and assayed for cell metabolic activity. MSCs were isolated from the proximal femur of 3–6 month old calves and expanded to passage 2 in a basal medium (BM) containing Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Gibco, Invitrogen Life Sciences, Carlsbad, CA), 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin-Fungizone (Gibco). Sections were cut from each scaffold with an 8 mm biopsy punch, sterilized in ethanol, rehydrated, and then seeded with 2×105 cells/scaffold (n=4/group). Metabolic activity was measured using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) colorimetric assay at 3, 7, and 14 days after seeding. Cells were also seeded onto tissue culture plastic (TCP) and cultured in BM (n=4/group).

Previous studies have shown that nanofibrous scaffolds intended for bone tissue engineering can be optimized for osteogenic differentiation by including ceramic particles like hydroxyapatite [29, 30]. To test this potential undesirable side effect of zirconia inclusion, two additional groups, MSCs seeded on either on 100% PCL scaffold or MSCs seeded on 50% PCL/50% zirconia scaffold, were cultured for 28 days in basal media and alkaline phosphatase activity was measured. To do so, the dephosphorylation of p-nitrophenyl (pNP) phosphate by alkaline phosphatase was quantified using a colorimetric assay kit (Alkaline Phosphatase Assay Kit (ab83369); Abcam PLC, Cambridge, UK) (n=5/group). Additionally, each scaffold type (100% PCL, 90% PCL/10% zirconia, 75% PCL, 25% zirconia, and 50% PCL/50% zirconia) was seeded with MSCs, cultured for 28 days in basal media, fixed in formalin and stained with von Kossa to determine whether overt mineralization had occurred (n=1/group).

2.5. In Vivo Evaluation in a Rat Model of Total Disc Replacement

To examine in vivo function, disc-like angle ply structures [11] fabricated from radiopaque scaffold (rDAPS) were implanted into the coccygeal spines (tails) of Sprague Dawley rats with institutional IACUC approval (male, 440–485 g, n = 5). To fabricate rDAPS, strips were cut from aligned radiopaque scaffold 30° to the fiber direction and two strips with alternating ±30° alignment were wrapped concentrically to form the annulus fibrosus region. Implantation of rDAPS into the rat coccygeal spine involved passing two surgical wires (0.8 mm) laterally through the mid-height of both the Co8 and Co9 vertebrae, and then fastening a radiolucent external fixator to the wires [Fig 2a–b]. A dorsal incision was made, the native disc was removed, rDAPS were inserted into the disc space, and the incision was closed. Rats were then returned to cage activity and euthanized 28 days post-surgery. Two implants of varying radiodensities were evaluated: a high radiodensity implant composed of two layers of 50% PCL/50% zirconia (50/50 rDAPS, n=2), and a low radiodensity implant composed of one layer of 75% PCL/25% zirconia, 1 layer of 100% PCL and one layer of degradable 75:25 poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) (multilayer rDAPS, n=3) [Fig. 2c]. We have previously shown that degradable layers included in DAPS provide additional routes for cell infiltration following implantation [11]. In each case, the layer thickness was 125 μm.

Figure 2. Radiopaque engineered discs in a rat model of total disc replacement.

(a) Rat tails were externally fixed with a custom device to provide a stable site for implantation [11]. (b) This device was radiolucent by design to allow for visualization of the disc space by fluoroscopy for longitudinal analysis. (c) rDAPS of two formulations were implanted: 50/50 rDAPS composed entirely of 50% PCL/50% zirconia layers, and multilayer rDAPS composed of three layers, a radiopaque layer of 75% PCL/25% zirconia, a radiolucent layer of 100% PCL, and a layer of 100% PLGA (designed to degrade when implanted in order to provide pathways for endogenous cell infiltration).

Implants were assessed for positioning between vertebrae, maintenance of microstructure, and integration with native tissues. To monitor implant position and structure in vivo, rat tails were imaged via fluoroscopy post-operatively and then at 3, 7, 14, 21, and 28 days through the radiolucent external fixator. Following euthanasia, the external fixator was removed and bone-rDAPS-bone motion segments were separated from the tails by sharp dissection. Motion segments were imaged via μCT (resolution: 20.5 μm for 50/50 rDAPS, 10 μm multilayer rDAPS) and reconstructed in 3D to confirm implant position and visualize implant microstructure. Following imaging, motion segments were fixed in formalin, decalcified in formic acid, and sectioned at 30 μm thickness on a cryostat microtome (Microm HM 500, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). To assess implant structure and integration with native tissue, sections were double-stained with alcian blue (for glycosaminoglycans) and picrosirius red (for collagen), and were visualized via brightfield microscopy (Eclipse 90i, Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Radiation attenuation and tensile modulus were compared between groups using one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with zirconia concentration as the independent variable. MTT results were analyzed by two-way ANOVA with time and zirconia concentration as the independent variables. In each case, Bonferroni’s post-hoc tests were used to make pairwise comparisons between groups (p<0.05). Finally, alkaline phosphatase activity was compared by t-test (p<0.05). Data are reported as mean ± standard deviation.

3. Results

3.1. Scaffold structure, radiation attenuation, mechanical function, and cytocompatibility

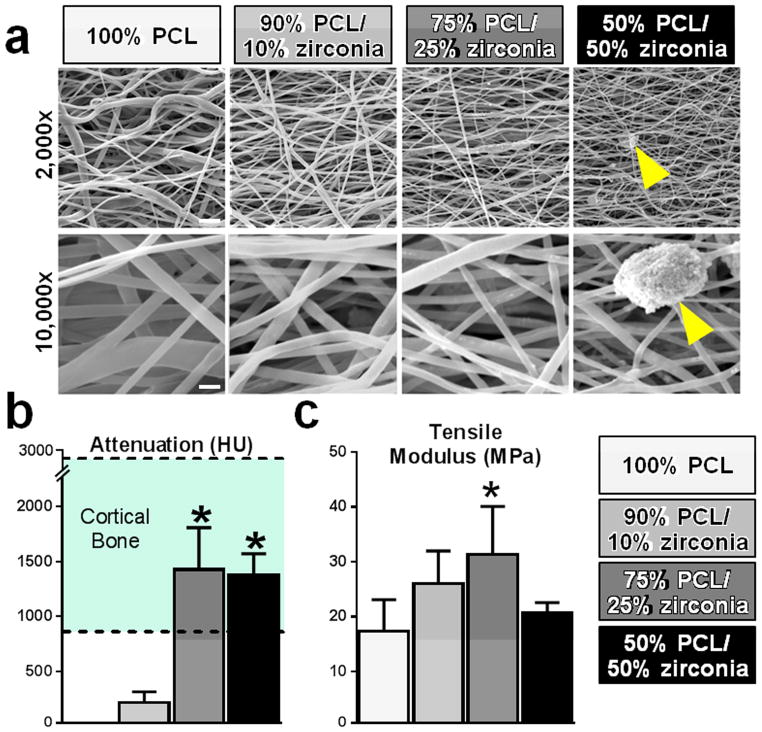

SEM analysis revealed that all formulations of the radiopaque scaffold had continuous and aligned nanofibers [Fig 3a]. Zirconia particles were embedded within the electrospun fibers and fiber morphology was not changed at lower concentrations, while at higher concentrations (25% and 50% zirconia scaffolds) zirconia aggregated as pellets exterior to the fibers. Radiation attenuation increased with zirconia content, plateauing at 25% zirconia inclusion [Fig 3b]. The measured attenuation of 50% and 25% zirconia scaffolds was within the attenuation range of cortical bone [31]. PCL alone had no signal and thus 3D reconstruction of 100% PCL scaffolds was not possible. The linear region tensile modulus of the radiopaque scaffold increased with increasing zirconia content, reaching a maximum at 25% zirconia. At higher levels (50%), the tensile modulus dropped sharply to the level of 100% PCL [Fig 3c]. When seeded with cells, there were no differences between scaffold variants in terms of cell proliferation which was slower on all scaffold formulations in comparison to cells seeded on TCP [Fig 4a]. Additionally, there was significantly less alkaline phosphatase activity on 50% PCL/50% zirconia scaffolds when compared to 100% PCL scaffolds [Fig 4b] and there was no evidence of positive von Kossa staining for any of the zirconia scaffolds. [Fig 4c].

Figure 3. Structure, linear attenuation coefficient, and tensile modulus of radiopaque scaffolds.

(a) All scaffold types were aligned and nanofibrous. Structure was largely unaltered with low zirconia inclusion levels, though zirconia clusters (arrows) appeared on the fiber surfaces at the highest concentration and to a lesser extent on 75% PCL/25% zirconia scaffold. Scales – top row: 5 μm, bottom row: 1 μm. (b) The linear attenuation coefficients of scaffolds with high zirconia content was similar to that of cortical bone (*p<0.05 vs. 90% PCL/10% zirconia). (c) Tensile modulus was greater with increasing zirconia concentration, except for the highest concentration (*p<0.05 vs. 100% PCL).

Figure 4. MSC viability and osteogenic potential on radiopaque scaffolds.

(a) The MTT assay for total cell metabolic activity over 14 days demonstrated no significant differences between groups and (b) quantification of alkaline phosphatase revealed diminished activity on radiopaque scaffolds (*, p<0.05). (c) Futhermore, von Kossa staining revealed no evidence of calcium on any of the radiopaque scaffolds. Scale, 4mm. These data indicate that scaffolds were not cytotoxic and did not cause osteogenesis.

3.2. Appearance of radiopaque scaffold in situ and with long term in vivo implantation

Radiopaque scaffolds were readily visualized within the bovine meniscus in situ in both anterior-posterior and medial-lateral fluoroscopic images of the knee [Fig 5a–b]. μCT reconstructions with Lugol’s solution used to enhance the contrast of the native meniscus provided anatomical information of the meniscus (the boundaries of the soft tissue were readily visualized) and positioning of the scaffold within the bucket handle tear [Fig 5c–e, Video S1]. The bucket handle tear was located near the boundary between the red-red and red-white meniscal regions and the layered scaffold was positioned within the tear, conforming to the curvature of the meniscus, with scaffold layers distinctly visible.

Figure 5. Visualization of radiopaque scaffold implanted into the bovine meniscus.

A layered radiopaque scaffold (arrows) was visible in an artificial tear created in the bovine medial meniscus on (a) medial-lateral and (b) anterior-posterior fluoroscopic images. Ex situ μCT analysis, with contrast enhancement to visualize the meniscus, is shown in (c) cross section, with (d) anterior and (e) cranial views after 3D reconstruction.

Both formulations of rDAPS were visualized intra- and post-operatively by μCT and fluoroscopy. 50/50 rDAPS had a distinct signal that allowed for segmentation of μCT images for 3D reconstructions [Fig 6a]. Fluoroscopy revealed that the radiopaque signal of 50/50 rDAPS was more intense than that of the native bone and that there was minimal change in implant position over time [Fig 6b]. Histologically, 50/50 rDAPS were located directly between vertebrae and were structurally intact, with little infiltration of local tissue [Fig 6c]. Multilayer rDAPS were segmented for 3D μCT reconstructions based on their appearance, and were located directly between vertebrae [Fig 7a]. The alternating radiopaque and non-radiopaque layers allowed for the visualization of the lamellar structure in transverse [Fig 7b] and axial [Fig 7c] cross-sections. Fluoroscopically, multilayer rDAPS were not distinguishable from adjacent vertebrae, and did not appear to migrate over time [Fig 7d]. Images of histological sections confirmed that the implant lamellar structure was maintained, new collagen was deposited on PCL/zirconia layers, and that PLGA had not fully degraded by day 28 [Fig 7e–f]. In addition, H&E stained sections revealed there was no endogenous response to the implanted biomaterial (not shown).

Figure 6. High radiopacity rDAPS in vivo.

(a) rDAPS (gold) were located directly between vertebrae (gray) at day 28 as visualized by μCT. Scale, 1 mm. (b) rDAPS (arrows) attenuation was distinct from adjacent vertebrae and position did not change over time as visualized by fluoroscopy. (c) Histologically, rDAPS maintained their lamellar structure, though no tissue infiltration was apparent (as expected for DAPS without sacrificial layers). Scale, 1mm.

Figure 7. Multilayer rDAPS in vivo.

rDAPS were fabricated to include a radiopaque PCL/zirconia layer, a non-radiopaque semi-permanent PCL layer, and a non-radiopaque degradable PLGA layer. (a) rDAPS (gold) were located directly between vertebrae (gray) with a distinct layered structure as visualized by μCT. Scale, 1mm. Individual layers were apparent in (b) transverse (scale, 1mm) and (a) axial (scale, 1mm) cross-sections. (d) Fluoroscopy demonstrated that low radiopacity rDAPS (arrows) were not distinct from adjacent vertebrate and that there was no change in position over time. (e) Histologically, rDAPS structure appeared intact and new tissue was deposited between layers. Scale, 1 mm. (f) Zirconia was sequestered within PCL/zirconia layers (star), while PCL-only layers (white arrow) and PLGA layers (striped white arrow) remained intact. New collagen deposits (black arrows) appeared on PCL/zirconia layers suggesting the radiopaque scaffold provides a template for fibrous tissue formation in vivo.

4. Discussion

In this study, we developed and characterized a radiopaque electrospun scaffolding system to enable visualization of engineered implants using clinically relevant and readily accessible imaging modalities (i.e., x-ray attenuation). Nanofibrous scaffolds were produced from PCL, a standard biodegradable polymer widely used in tissue engineering applications, coupled with nanoparticles composed of zirconia, a ceramic nanopowder. While many scaffolds for bone tissue engineering are intrinsically radiopaque, this is the first scaffold of its kind for fibrous tissue engineering applications. In developing this system, we demonstrated that scaffold radiopacity and mechanical properties could be tuned by altering the concentration of zirconia included in each fiber, that the scaffolds were visible radiographically when implanted into large joints of human dimensions, that inclusion of the radiopacifier did not influence cell viability or proliferation, and that it did not instigate osteogenic differentiation by MSCs seeded onto these scaffolds or when placed into the disc space. Radiopaque implants designed for total disc replacement were visible over 4 weeks using both fluoroscopy and μCT. In addition, these scaffolds were compatible with the formation of collagenous tissue in vivo, establishing their utility for both animal model development and fibrous tissue engineering applications.

The linear attenuation coefficient of scaffolds was assessed in vitro and the total radiation attenuation was assessed in vivo. The linear attenuation coefficient of electrospun scaffolds changed as a result of inclusion of the zirconia nanoparticles. Specifically, the linear attenuation coefficient increased with zirconia content, reaching a plateau at 25% zirconia. This may suggest that the maximum packing density of zirconia in the nanofibers is in the range of 25%. Thus, while scaffolds were nominally 50%, 25%, 10% or 0% zirconia, at the highest concentration phase separation may have occurred during the electrospinning procedure as evidenced by the extrafibrillar accumulation of zirconia in SEM images. The linear attenuation coefficient reported here is a property intrinsic to the scaffold material. It represents the volumetric average of radiation attenuation and consequently is not a function of scaffold geometry. As it is a material property it allows for direct comparisons between samples independent of scaffold geometry. Fluoroscopic images however are a visualization of total radiation attenuation, which is a function of scaffold geometry. For our in vivo studies, the 50/50 rDAPS were composed of 100% radiopaque layers, while the multilayer (75/25) rDAPS consisted of only 33% radiopaque layers. This resulted in a difference in the total radiation attenuation of the two implant types, despite 75/25 and 50/50 layers have a similar linear attenuation coefficient. For future studies, by controlling the zirconia content, scaffold radiopacity could be tuned for a specific application. For example, if an electrospun scaffold is used to repair a deeper tissue, such as a tissue inside a synovial joint [32], the abdomen [33], or within the lumbar spine [11], a high radiodensity scaffold may be required for adequate visualization. However, in a subcutaneous model, a less radiodense scaffold may be useful, since the superficial nature of a subcutaneous model lends itself to less obstructed visualization.

Scaffold mechanical properties were also affected by increasing the concentration of zirconia nanoparticles. Tensile modulus initially increased with increasing zirconia content but declined at the highest concentration. This phenomenon has also been observed in electrospun scaffolds containing hydroxyapatite inclusions that have been investigated for bone tissue engineering [34], and may be related to a loss of fiber continuity at high filler concentrations. The aggregation of zirconia on the surface of the 50% zirconia scaffolds may also have an effect on the mechanical response (by altering fiber-to-fiber interactions), and further suggests that zirconia concentration within PCL had reached a saturation point at this high percent weight.

To assess in vivo potential, radiopaque implants formed with high and low concentrations of zirconia were visualized in the rat coccygeal spine. Previous work with this model demonstrated that the retention of engineered discs can be improved by stabilizing the implant site with an external fixation device [11]. Visualization by fluoroscopy in this context was useful for intraoperative positioning of the implant and to confirm that there was no migration of scaffolds over time. Likewise, imaging of the scaffold in situ in the bovine knee demonstrated the potential utility of these radiopaque scaffolds in large animal and human applications. Subsequent μCT analyses on explanted tissues offered high resolution scaffold imaging and dimensioning that could be coupled with other outcome measures (such as histology) to better monitor scaffold localization, integration, and degradation with time after implantation. These features may enable the conservation of animals in future studies by eliminating the number of iterations required for improving surgical techniques during model development.

The inclusion of zirconia into the PCL fibers did not alter cell viability and appeared to not be a factor in promoting osteogenesis. While other polymer/ceramic composite scaffolds have been used to promote an osteogenic phenotype, we did not observe additional alkaline phosphatase activity or calcium deposition on scaffolds containing zirconia cultured in vitro. Furthermore, when these scaffolds were implanted into the rat coccygeal spine after discectomy (a location that is prone to fusion), we did not find any evidence of increased mineral density in adjacent to the intervertebral space (by μCT) after 4 weeks. Other osteogenic scaffolds are composed of minerals like hydroxyapatite or calcium phosphate [35, 36] which are naturally present in bone and provide raw materials that cells can utilize to form mineral deposits; in contrast, zirconia is foreign to the body and should not play a role in this process. Future work is required to fully characterize MSCs and other cell types after seeding onto these scaffolds, including measurements of extracellular matrix production and the expression of genes relevant to the osteogenic and fibrochondrogenic phenotype. Over a one month implantation time, multilayer rDAPS were compatible with the formation of new collagenous tissue by endogenous rat cells in the coccygeal spine. Taken together these data suggest that PCL/zirconia scaffolds may be useful for both developing engineered fibrous tissues and evaluating these tissues in in vivo models.

As PCL will degrade in vivo, implanted scaffolds fabricated from PCL and zirconia will release zirconia once the slowly degrading PCL begins to break down, thus introducing a potential contaminant into the local microenvironment. A previous report demonstrated that the zirconia nanoparticles have the physical properties of a biologically inert material, and when zirconia nanoparticles were directly included in the culture media of 3T3 fibroblasts in monolayer, there was no effect on cell morphology or viability [37]. Our study confirmed there was no effect of zirconia at any concentration on cell viability in vitro. In addition, H&E stained sections from rDAPS implanted in vivo showed no aberrant cellular response to two implant types with high or low concentrations of zirconia. This provides strong evidence that zirconia within the PCL fibers are not cytotoxic at the implant site. However, these studies are limited in that the timepoints evaluated are too early for the PCL degradation process to have occurred, thus little release of zirconia into the media or into the disc space would be expected. An additional limitation of this scaffold system may be that the radiopacity could change after the release of zirconia through the normal degradation of PCL, which could limit ability to radiographically visualize and track scaffolds after long-term implantation. Scaffold displacement usually occurs relatively soon after implantation, and at these longer time points, one would expect that the scaffold would be fully integrated in the surrounding native tissue. Future studies will focus on these potential changes in scaffold radiopacity, as well as the potential for systemic and local inflammatory responses to zirconia, after long-term degradation of the PCL fibers (on the order of months to years). These studies will identify whether the scaffold is best used for shorter term optimization of scaffold placement and surgical methods, or whether it may be considered for long term applications as well.

5. Conclusions

Taken together, these data show that zirconia-embedded polymer scaffolds can be visualized radiographically in both small and large animal models and can serve as a framework for the development of an engineered fibrous tissue. The material was cytocompatible and did not promote osteogenesis as demonstrated both in vitro, using a cell source with a pliable phenotype, and in vivo, where collagenous tissue was deposited into the scaffold. A scaffold with these characteristics will allow for the image-guided implantation and non-invasive assessment of engineered fibrous tissues.

Supplementary Material

3D Visualization of radiopaque scaffold in the bovine meniscus. (0–7s) Proximal and distal surfaces of the medial meniscus and the location of the scaffold are shown through a 3D rotation. (7–11s) Consecutive slices through the meniscus from the anterior to posterior regions are shown, highlighting the positioning and cross-sectional area of the scaffold within the meniscus defect.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Department of Defense (OR090090), the National Institutes of Health (R01 EB02425), the Penn Center for Musculoskeletal Disorders (P30 AR050950), and the Department of Veterans’ Affairs (IK2 RX001476, H.E.S.).

Footnotes

6. Disclosures

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

John T. Martin, Email: johnma@mail.med.upenn.edu.

Andrew H. Milby, Email: andrew.milby@uphs.upenn.edu.

Kensuke Ikuta, Email: ken.ikuta.hto@gmail.com.

Subash Poudel, Email: spoudel@seas.upenn.edu.

Christian G. Pfeifer, Email: dr.christianpfeifer@gmail.com.

Dawn M. Elliott, Email: delliott@udel.edu.

Harvey E. Smith, Email: harvey.smith@uphs.upenn.edu.

Robert L. Mauck, Email: lemauck@mail.med.upenn.edu.

References

- 1.Parenteau N, Hardin-Young J, Shannon W, Cantini P, Russell A. Meeting the need for regenerative therapies I: target-based incidence and its relationship to U.S. spending, productivity, and innovation. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2012;18:139–54. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2011.0454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abrams GD, Frank RM, Gupta AK, Harris JD, McCormick FM, Cole BJ. Trends in meniscus repair and meniscectomy in the United States, 2005–2011. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41:2333–9. doi: 10.1177/0363546513495641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jarvinen TL, Sihvonen R, Malmivaara A. Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy for degenerative meniscal tear. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1260–1. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1401128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Helgeson MD, Bevevino AJ, Hilibrand AS. Update on the evidence for adjacent segment degeneration and disease. Spine J. 2013;13:342–51. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2012.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Angeline ME, Rodeo SA. Biologics in the management of rotator cuff surgery. Clin Sports Med. 2012;31:645–63. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2012.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mizuno H, Roy AK, Vacanti CA, Kojima K, Ueda M, Bonassar LJ. Tissue-engineered composites of anulus fibrosus and nucleus pulposus for intervertebral disc replacement. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2004;29:1290–7. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000128264.46510.27. discussion 7–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nerurkar NL, Sen S, Huang AH, Elliott DM, Mauck RL. Engineered disc-like angle-ply structures for intervertebral disc replacement. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2010;35:867–73. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181d74414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu HH, Cooper JA, Jr, Manuel S, Freeman JW, Attawia MA, Ko FK, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament regeneration using braided biodegradable scaffolds: in vitro optimization studies. Biomaterials. 2005;26:4805–16. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brophy RH, Cottrell J, Rodeo SA, Wright TM, Warren RF, Maher SA. Implantation of a synthetic meniscal scaffold improves joint contact mechanics in a partial meniscectomy cadaver model. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2010;92:1154–61. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bowles RD, Gebhard HH, Hartl R, Bonassar LJ. Tissue-engineered intervertebral discs produce new matrix, maintain disc height, and restore biomechanical function to the rodent spine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:13106–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107094108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martin JT, Milby AH, Chiaro JA, Kim DH, Hebela NM, Smith LJ, et al. Translation of an engineered nanofibrous disc-like angle-ply structure for intervertebral disc replacement in a small animal model. Acta Biomater. 2014;10:2473–81. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xinzhi Zhang J-MC, Easly Jeremiah T, Hackett Eileen, Doty Stephen, Levine William M, Edward Guo X, Lu Helen H. In vivo Evaluation of a Biomimetic Biphasic Scaffold in Sheep. Transaction of the Orthopaedic Research Society, 60th Annual Meeting; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maher SA, Rodeo SA, Doty SB, Brophy R, Potter H, Foo LF, et al. Evaluation of a porous polyurethane scaffold in a partial meniscal defect ovine model. Arthroscopy. 2010;26:1510–9. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2010.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iu J, Santerre JP, Kandel RA. Inner and outer annulus fibrosus cells exhibit differentiated phenotypes and yield changes in extracellular matrix protein composition in vitro on a polycarbonate urethane scaffold. Tissue Eng Part A. 2014;20:3261–9. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2013.0777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nerurkar NL, Elliott DM, Mauck RL. Mechanics of oriented electrospun nanofibrous scaffolds for annulus fibrosus tissue engineering. J Orthop Res. 2007;25:1018–28. doi: 10.1002/jor.20384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fisher MB, Henning EA, Soegaard N, Esterhai JL, Mauck RL. Organized nanofibrous scaffolds that mimic the macroscopic and microscopic architecture of the knee meniscus. Acta Biomater. 2013;9:4496–504. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2012.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baker BM, Nathan AS, Huffman GR, Mauck RL. Tissue engineering with meniscus cells derived from surgical debris. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2009;17:336–45. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chainani A, Hippensteel KJ, Kishan A, Garrigues NW, Ruch DS, Guilak F, et al. Multilayered electrospun scaffolds for tendon tissue engineering. Tissue Eng Part A. 2013;19:2594–604. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2013.0165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kolluru PV, Lipner J, Liu W, Xia Y, Thomopoulos S, Genin GM, et al. Strong and tough mineralized PLGA nanofibers for tendon-to-bone scaffolds. Acta Biomater. 2013;9:9442–50. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.07.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beason DP, Connizzo BK, Dourte LM, Mauck RL, Soslowsky LJ, Steinberg DR, et al. Fiber-aligned polymer scaffolds for rotator cuff repair in a rat model. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21:245–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2011.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee CH, Shin HJ, Cho IH, Kang YM, Kim IA, Park KD, et al. Nanofiber alignment and direction of mechanical strain affect the ECM production of human ACL fibroblast. Biomaterials. 2005;26:1261–70. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Samavedi S, Olsen Horton C, Guelcher SA, Goldstein AS, Whittington AR. Fabrication of a model continuously graded co-electrospun mesh for regeneration of the ligament-bone interface. Acta Biomater. 2011;7:4131–8. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nathan AS, Baker BM, Nerurkar NL, Mauck RL. Mechano-topographic modulation of stem cell nuclear shape on nanofibrous scaffolds. Acta Biomater. 2011;7:57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li WJ, Mauck RL, Cooper JA, Yuan X, Tuan RS. Engineering controllable anisotropy in electrospun biodegradable nanofibrous scaffolds for musculoskeletal tissue engineering. J Biomech. 2007;40:1686–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li WJ, Cooper JA, Jr, Mauck RL, Tuan RS. Fabrication and characterization of six electrospun poly(alpha-hydroxy ester)-based fibrous scaffolds for tissue engineering applications. Acta Biomater. 2006;2:377–85. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baker BM, Nerurkar NL, Burdick JA, Elliott DM, Mauck RL. Fabrication and modeling of dynamic multipolymer nanofibrous scaffolds. J Biomech Eng. 2009;131:101012. doi: 10.1115/1.3192140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qu F, Pintauro MP, Haughan JE, Henning EA, Esterhai JL, Schaer TP, et al. Repair of dense connective tissues via biomaterial-mediated matrix reprogramming of the wound interface. Biomaterials. 2015;39:85–94. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.10.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnstone B, Hering TM, Caplan AI, Goldberg VM, Yoo JU. In vitro chondrogenesis of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal progenitor cells. Exp Cell Res. 1998;238:265–72. doi: 10.1006/excr.1997.3858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lao L, Wang Y, Zhu Y, Zhang Y, Gao C. Poly(lactide-co-glycolide)/hydroxyapatite nanofibrous scaffolds fabricated by electrospinning for bone tissue engineering. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2011;22:1873–84. doi: 10.1007/s10856-011-4374-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang Y, Venugopal JR, El-Turki A, Ramakrishna S, Su B, Lim CT. Electrospun biomimetic nanocomposite nanofibers of hydroxyapatite/chitosan for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2008;29:4314–22. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hubbell JH, Seltzer SM. Tables of X-Ray Mass Attenuation Coefficients and Mass Energy-Absorption Coefficients from 1 keV to 20 MeV for Elements Z = 1 to 92 and 28 Additional Substances of Dosimetric Interest. National Institute of Standards and Technology. Reference Database 126–1996 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chainani A, Hippensteel KJ, Kishan A, Garrigues NW, Ruch DS, Guilak F, et al. Multilayered Electrospun Scaffolds for Tendon Tissue Engineering. Tissue Eng Part A. 2013 doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2013.0165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hong Y, Takanari K, Amoroso NJ, Hashizume R, Brennan-Pierce EP, Freund JM, et al. An elastomeric patch electrospun from a blended solution of dermal extracellular matrix and biodegradable polyurethane for rat abdominal wall repair. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2012;18:122–32. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2011.0295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Venugopal J, Low S, Choon AT, Kumar AB, Ramakrishna S. Electrospun-modified nanofibrous scaffolds for the mineralization of osteoblast cells. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2008;85:408–17. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gandhimathi C, Venugopal J, Ravichandran R, Sundarrajan S, Suganya S, Ramakrishna S. Mimicking nanofibrous hybrid bone substitute for mesenchymal stem cells differentiation into osteogenesis. Macromol Biosci. 2013;13:696–706. doi: 10.1002/mabi.201200435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.He C, Xiao G, Jin X, Sun C, Ma PX. Electrodeposition on nanofibrous polymer scaffolds: Rapid mineralization, tunable calcium phosphate composition and topography. Adv Funct Mater. 2010;20:3568–76. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201000993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Karunakaran G, Suriyaprabha R, Manivasakan P, Yuvakkumar R, Rajendran V, Kannan N. Screening of in vitro cytotoxicity, antioxidant potential and bioactivity of nano- and micro-ZrO2 and -TiO2 particles. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2013;93:191–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

3D Visualization of radiopaque scaffold in the bovine meniscus. (0–7s) Proximal and distal surfaces of the medial meniscus and the location of the scaffold are shown through a 3D rotation. (7–11s) Consecutive slices through the meniscus from the anterior to posterior regions are shown, highlighting the positioning and cross-sectional area of the scaffold within the meniscus defect.