Abstract

Large granular lymphocytes (LGLs) have only been anecdotally reported in HIV infection. We previously reported an LGL lymphocytosis in FIV-infected cats associated with a rise in FIV proviral loads and a marked neutropenia that persisted during chronic infection. Extensive immunophenotyping of peripheral blood mononuclear cells in cats chronically infected with FIV were identified LGLs as CD8lo+FAS+; this cell population expanded commensurate with viral load. CD8lo+FAS+ cells expressed similar levels of interferon-γ compared to CD8lo+FAS+ cells from FIV-naive control animals, yet CD3ε expression, which was increased on total CD8+ T cells in FIV-infected cats, was decreased on CD8lo+FAS+ cells. Down-modulation of CD3 expression was reversed after culturing PBMC for 3 days in culture with ConA/IL-2. We identified CD8lo+FAS+ LGLs to be polyclonal T cells lacking CD56 expression. Blood smears from HIV-infected individuals and SIVmac239-infected rhesus macaques revealed increased LGLs compared to HIV/SIV negative counterparts. In humans, there was no correlation with viral load or treatment and in macaques the LGLs arose in acute SIV infection with increases in viremia. This is the first report describing and partially characterizing LGL lymphocytosis in association with lentiviral infections in three different species.

Keywords: CD8+FAS+ cell, FIV, HIV, SIV, large granular lymphocytes

Introduction

The importance of CD8+ T cells in control of lentiviral infection of humans, macaques and cats has been apparent for decades (Flynn et al., 1999; Jeng et al., 1996; Kannagi et al., 1988; Walker et al., 1986). Studies of different CD8+ subset function in innate and adaptive immune responses has indicated that central memory CD8+ T cells are the CD8+ cell subset with the most in vitro viral suppressive activity (Buckheit et al., 2012; Lopez et al., 2011; Mendoza et al., 2012; Ndhlovu et al., 2012)

Historically, large granular lymphocytes (LGLs) have been considered either NK cells or CD3+ cells that participate in antibody-dependent cytotoxicity (Chan et al., 1986). LGLs represent 10–15% of the peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) population in healthy individuals (Loughran, 1993). This low percentage of LGLs has made detailed analysis difficult and thus, most information about LGLs is derived from studies on patients with LGL leukemia (Alekshun and Sokol, 2007). LGLs have only been anecdotally reported during HIV infection, and have usually been associated with neoplasia (Boveri et al., 2009; Pulik et al., 1997). However, a study of HIV-infected patients reported that LGLs persisted between 6 and 30 months and had a consensus phenotype in PBMC of activated CD8+ T cells expressing CD57. LGLs in these patients represented polyclonal T cells (Smith et al., 2000).

We have previously reported that FIV-infected cats had a LGL lymphocytosis that was temporally associated with neutropenia, increased PBMC-associated FasL mRNA and decreased in PBMC FIV proviral loads (Sprague et al., 2010). We report here that these LGLs correlated with cells that expressed low surface CD8 and FAS, that were polyclonal T cells and that expressed similar intracellular interferon-γ in FIV-infected animals compared to FIV-naive control animals. These cells also expressed decreased surface CD3epsilon (CD3ε) levels in FIV-infected animals compared to FIV-naive controls and this decreased expression was upregulated via cytokine rescue. Most interestingly, we found that LGLs arise during acute SIV infection in macaques and are detectable and elevated during HIV infection in humans, documenting the importance and presence of these cells during lentiviral infections in three different species.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Blood of cats from two different studies were included in the overall study design. Two chronically infected cats were originally infected at 6 months of age with an IV inoculation of 1 ml of a previously characterized FIV-C-PG (Terwee et al., 2008). Blood from these cats was collected in EDTA by venipuncture and was used for the CD8lo+FAS+ cell phenotypic characterization; flow sorting studies and CD8lo+FAS+ cell PCR for TCR receptor and immunoglobulin rearrangement studies. Additionally, six cats were infected with an IV inoculation of 1ml of FIV-C-PG. These cats were 6 months of age at time of infection and blood samples were collected in EDTA by venipuncture on the day of FIV-C-PG infection and during acute infection at 1, 2 and 4 weeks PI. The blood of these cats was used for the CD8lo+FAS+ cell and LGL correlation studies and for the cell culture studies to evaluate CD3ε up-regulation. In addition, blood from four age matched FIV-naïve cats were used for the flow cytometric studies of CD8lo+FAS+ cells. All cats were specific-pathogen-free (SPF) and the chronically infected cats were 3-4 years of age at the time of study. None of the cats were given any other vaccinations and all cats were maintained in an AAALAC International approved animal facility at Colorado State University (CSU). All procedures were approved by the CSU Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee prior to initiation. Eight macaques, maintained at the Tulane National Primate Research Center, were infected intravenously with SIVmac239 according to standard procedures as part of another study performed in 2007 (Stump, 2008). EDTA blood was collected by venipuncture every 10 days to 2 weeks for approximately 3 months and blood smears were made and stored for later examination of LGLs.

Human Blood Smears

Blood was collected by venipuncture from eight individuals with HIV infection to evaluate blood smears for the presence of LGLs. All individuals provided written consent prior to participating in this study, and all studies were approved by the Poudre Valley Health System Institutional Review Board. HIV status was determined by screening tests using an ADVIA Centaur HIV 1/O/2 Enhanced immunoassay (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Tarrytown, NY). Blood smears were examined for the presence of LGLs. Blood smears from nine HIV-negative controls were also evaluated. The pathologist (Sprague) was blinded to the infection status when reading the slides. White blood cell (WBC) counts, CD4 T cell counts, viral loads and treatment regimens were also provided.

Large granular lymphocyte enumeration

Absolute LGLs counts of all species were determined by multiplying the blood smear differential counts by total WBC counts. Total white blood cell counts were measured using a Coulter Z1 (Coulter, Miami, FL). Differential cell counts were performed manually and LGL counts were recorded as a percentage of the nucleated cells after 100 nucleated cells were counted.

Flow Cytometry

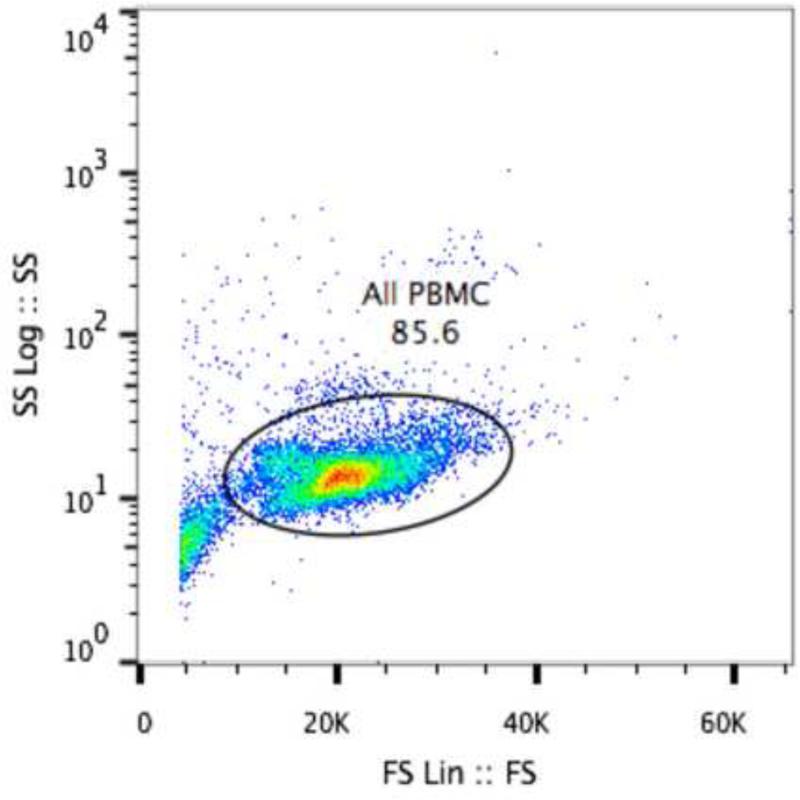

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated over a Histopaque 1.077 gradient (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) according to manufacturer's instructions. Percentages of cells positive for CD8lo+FAS+ and CD8+CD57+ expression were determined by flow cytometry using a directly conjugated monoclonal antibody (Ab) to feline CD8α (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL), a polyclonal Ab to feline FAS (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN), and a cross-reactive directly conjugated monoclonal Ab to human CD57 (Beckman-Coulter, Brea, CA). CD3ε expression on CD8lo+FAS+ cells was examined using a FITC-conjugated monoclonal anti-feline CD3ε Ab recognizing the CD3 surface receptor (gift of T. Miyazawa; 1:100 dilution). Intracellular interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) expression was examined in CD8lo+FAS+ cells using a polyclonal anti-feline IFN-γ Ab R&D systems). For multicolor flow cytometry using IFN-γ, surface Abs were incubated with cells followed by fixation and permeabilization and staining with IFN-γ according to manufacturer's instructions (BD Perm/Wash, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). For the FAS polyclonal antibody, labeling with fluorochrome prior to staining cells was accomplished using a Zenon antibody labeling kit (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). A directly conjugated anti-human CD56 (NCAM; Biolegend, San Diego, CA; 1:20 dilution) that has been shown to cross-react with feline CD56 Ab was used to determine if the CD8+FAS+ cells expressed this NK marker (Simoes et al., 2012). Two × 105 to 1 × 106 PBMC were used per reaction and cell Fc receptors were blocked using goat serum (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH) at a 1:10 dilution and incubated for 30 minutes at 4°C. After washing cells, cells were incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature in triplicate with the CD8α Ab at a 1:100 dilution, the Fas Ab at 1:200 dilution and the CD57 Ab at 1:5 dilution in flow buffer (PBS containing 5% FBS and 0.2% sodium azide). The CD56 Ab was added to the mixture of antibodies in some experiments. Cells were then washed three times in flow buffer and re-suspended in 200 μL of buffer with 1% paraformaldehyde for fixation. Samples were then analyzed on a DAKO Cyan ADP (Beckton-Dickinson, Brea, CA). Gates were set to eliminate small particles, neutrophils and eosinophils using forward and side scatter (Fig. 1). A total of between 5,000 – 20,000 gated cells were analyzed, depending on the starting volume of cells. Isotype-matched mouse immunoglobulins (Igs) were used as controls for monoclonal Abs or goat Igs were used as controls for polyclonal Abs. Fluorescence of the primary Abs was set based on 1% positive fluorescence of the isotype controls. Data was analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star Inc., San Carlos, CA). Absolute CD8+FAS+ counts were determined by multiplying the percent of gated cells expressing CD8+FAS+ by the total white blood cell count minus the absolute neutrophil, eosinophil and basophil counts that were determined by blood smear differential counts.

Fig 1.

Scatterplot of PBMC isolated with FIcoll-Hypaque showing gating strategy for detecting large granular lymphocytes. The plot is from 1 cat and is representative of 6 cats.

Cell culture to test CD3ε expression upregulation on CD8lo+FAS+ cells from FIV infected cats

PBMC were isolated from the blood of cats infected with FIV as described above. Flow cytometric analysis of CD8lo+FAS+ cells and CD3ε expression on these cells was performed on freshly isolated cells and on cells after 3 days in the presence of Con A (5μg/ml) and hIL-2 (1μg/ml) in complete media ((RPMI 1640; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) with 15% FBS (Hyclone, Thermo Scientific, Logan, UT), 2mM Glutamine (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and 0.5% beta-mercaptoethanol solution (1:150 dilution in media, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO)).

Flow sorting of CD8lo+FAS+ cells

In order to characterize the phenotype of the feline LGLs, we sorted CD8lo+FAS+ and CD8+CD57+ expressing cells using a MoFlo Legacy (Beckman-Coulter, Brea, CA). PBMC were isolated and stained as described above. The cells were sorted into cold complete media. The cells were centrifuged in refrigeration at 1200 × g for 10 minutes, counted and aliquoted for further experimentation. Twenty thousand cells were placed onto glass slides using a cytocentrifuge at 300 rpm for 3 min. (Shandon Cytospin 4, Thermo Scientific, Asheville, NC) and then stained with a Wright-Giemsa stain according to manufacturer's instructions (Harleco, EMD Chemicals, Rockland, MA). Cytocentrifuged preparations of CD8lo+FAS+ cells were examined. Flow cytometry was performed on sorted cells by re-staining the cells with CD8 and FAS Abs.

PCR for Antigen Receptor Rearrangements

DNA from sorted CD8lo+FAS+ cells was isolated with a commercially available kit (Qiagen DNA blood mini kit, Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Between 100 and 500 ng of DNA was amplified using a Qiagen Multiplex Master Mix Kit. Amplification of immunoglobulin (Ig) and T-cell receptor gamma sequences was performed using the following previously described primers: 1) For immunoglobulin genes: VIC-ccgaggacacggccacatatt (forward), ctctgaggacaccgtcaccag and ctctgaggacactgtgactat (reverse); 2) For T cell receptor genes: PET-aagagcgaygagggmgtgt (forward), ctgagcagtgtgccagsacc (reverse); 3) Positive control feline rhodopsin: FAM-accacccagaaggctgaga (forward), ccgggagtgtcatgaagatg (reverse) (Moore et al., 2012). The primers were used at a concentration of 200nM in 3 individual 25μl reactions. The cycling conditions were as follows: 94 °C for 8s, 60 °C for 10 s, 72 °C for 15s for 40 cycles in an ABI 9600 Thermocycler. PCR products were denatured using Hi-Di Formamide (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) and then analyzed by capillary electrophoresis using the ABI 3130XL (Life Technologies). A sample was determined to be clonal if there were one to four discrete PCR products greater than 3 × the height of polyclonal products in the same sample. The sample was interpreted as polyclonal (negative for clonality) if there were heterogeneously sized PCR products present, with no individual product greater than 3 × the height of the next highest peak. Hi-di formamide

Real-time DNA PCR for FIV Proviral Loads

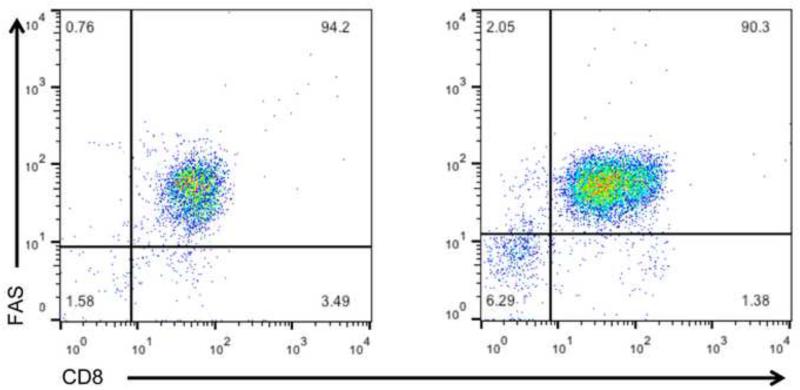

One million sorted CD8lo+FAS+ cells were isolated from two cats chronically infected with FIV-C-PG with a purity of 91 - 94% (Fig. 2). DNA was extracted from the cell pellets using the Qiamp blood mini DNA kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). DNA was eluted with 50-200 μl of buffer. Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) was performed using previously published FIV CPGammar primer and probes sequences (Pedersen et al., 2001) and an iCycler IQ™ (Bio-Rad). qPCR was performed using the 2X TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosciences, Foster City, CA) consisting of 10mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 50mM KCl, 5mM MgCl2, 300μM each of dATP, dCTP, and dGTP, 600μM dUTP, 0.625U of AmpliTaq Gold DNA polymerase, and 0.25U uracil N-glycosylase (UNG) per reaction. Reactions were in a total of 25μl and consisted of 12.5μl Mastermix, 5μl of sample or standard, 400nmM of each primer and 80nM of probe. Themal cycling conditions were 2 min. at 50°C to induce enzymatic activity of UNG, 10 min. at 95°C to reduce UNG activity and to activate AmpliTaq Gold DNA, followed by 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min. A standard curve was generated with 10-fold serial dilutions of FIV C gag plasmid DNA with 1X TE and 40ng/ml salmon testes DNA (Sigma-Aldrich) as a DNA carrier for each run and calculation of FIV C DNA viral copies was calculated from these curves. The sensitivity of detection is a minimum of 5 copies. Copy number was normalized to the cellular reference gene, Glyceraldehyde-3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase (GAPDH), to calculate copy number per extracted cell.

Fig 2.

Scatterplots of CD8lo+FAS+ cells after sorting and re-staining with CD8 and FAS Abs. The majority of the CD8lo+FAS+ cells collected during sorting express both CD8 and FAS. The scatterplots are from the blood of two different cats chronically infected with FIV.

Statistical Analysis

Correlation coefficient with linear regression analysis was assessed between CD8lo+FAS+ and LGL in FIV-infected cats at week 4 PI when both cells began to increase. Six cats were used for the LGL enumeration and 4 of the same 6 cats were used for the CD8lo+FAS+ cell enumeration. HIV-infected vs. the HIV-naïve peripheral blood LGL counts were compared using the Student's T-tests after log transformation to normalize the data. Statistical significance was considered to have occurred when a p value was < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using Prism version 4.0b software for Macintosh, copyright 2004 (GraphPad, Inc. San Diego, CA).

Results

LGLs are CD8lo+FAS+ cells and are not CD8+CD57+ cells in cats with chronic FIV infection

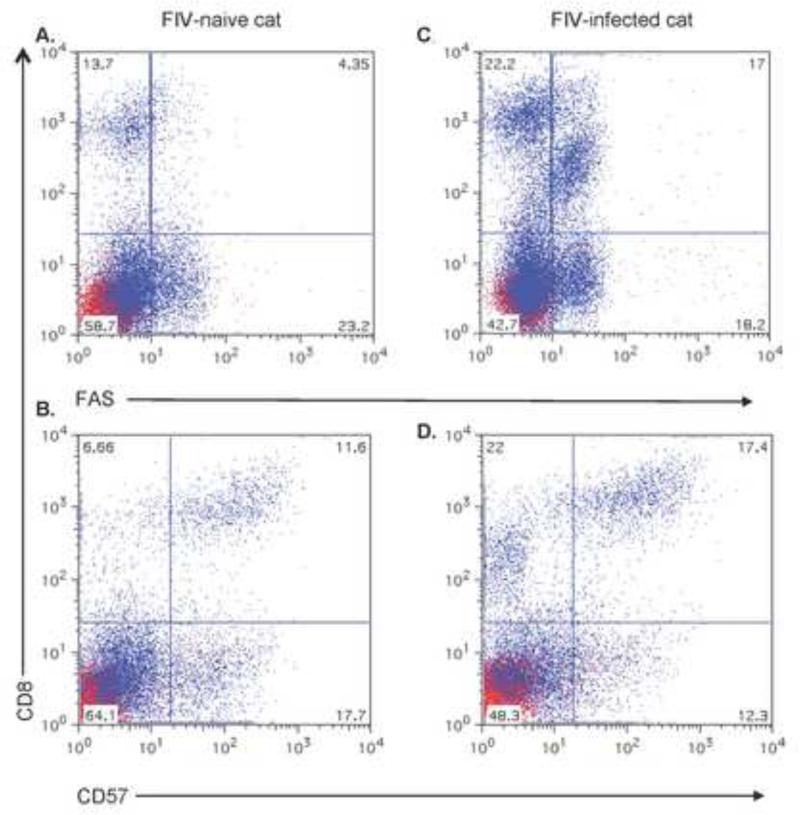

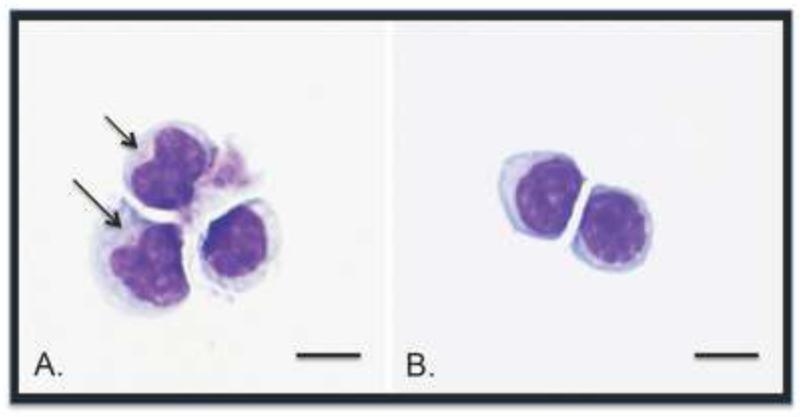

To identify the phenotype of FIV-associated LGLs, we evaluated a variety of subsets of CD8+ cells that we found to be increased during chronic FIV infection, including CD8+FAS+ cells and CD8+CD57+ cells (Fig. 3). We anticipated that LGLs would be CD8+CD57+, since this phenotype most frequently seen with LGL leukemias and common variable immunodeficiencies (Baumert et al., 1992; Holm et al., 2006; Loughran and Starkebaum, 1987). However, after sorting cells and evaluating morphologies, we determined that LGLs were CD8+FAS+ and not CD8+CD57+ (Fig. 4). LGLs represented 91% of the cytocentrifuged CD8lo+FAS+ cells of 100 cells counted. This correlated with the flow cytometric analysis of the sorted CD8+FAS+ cells, which represented about 91% - 94% of the cells (see Fig. 2). Down-modulation of CD8 expression was also documented on the CD8+FAS+ cells, that we have designated as CD8lo+FAS+ cells (see Fig 3).

Fig 3.

Scatterplots of CD8+FAS+and CD8+CD57+ cell surface expression in PBMC of cats chronically infected with FIVC36 versus PBMC of FIV-naïve cats. FIV-naïve cat PBMC plots in (A) and (B) and FIV-infected cat PBMC plots in (C) and (D). CD8+FAS+ cells in plots (A) and (C) and CD8+CD57+ cells in plots (B) and (D). Scatterplots are derived from one cat in each group and represents three cats examined in the FIV-infected group and four cats in the FIV-naïve group.

Fig. 4.

Photomicrographs from cytospun CD8+FAS+ cells (A) and CD8+CD57+ cells (B) after flow cytometric sorting. CD8+FAS+ cells are larger, have more abundant cytoplasm and often have fine azurophilic granules (arrows) compared to the CD8+CD57+ cells. Bars indicate 10μm in length. Results are from one cat representing three FIV-infected cats examined.

CD8lo+FAS+ cells have decreased CD3 expression from cats with chronic FIV infection vs. FIV-naïve cats

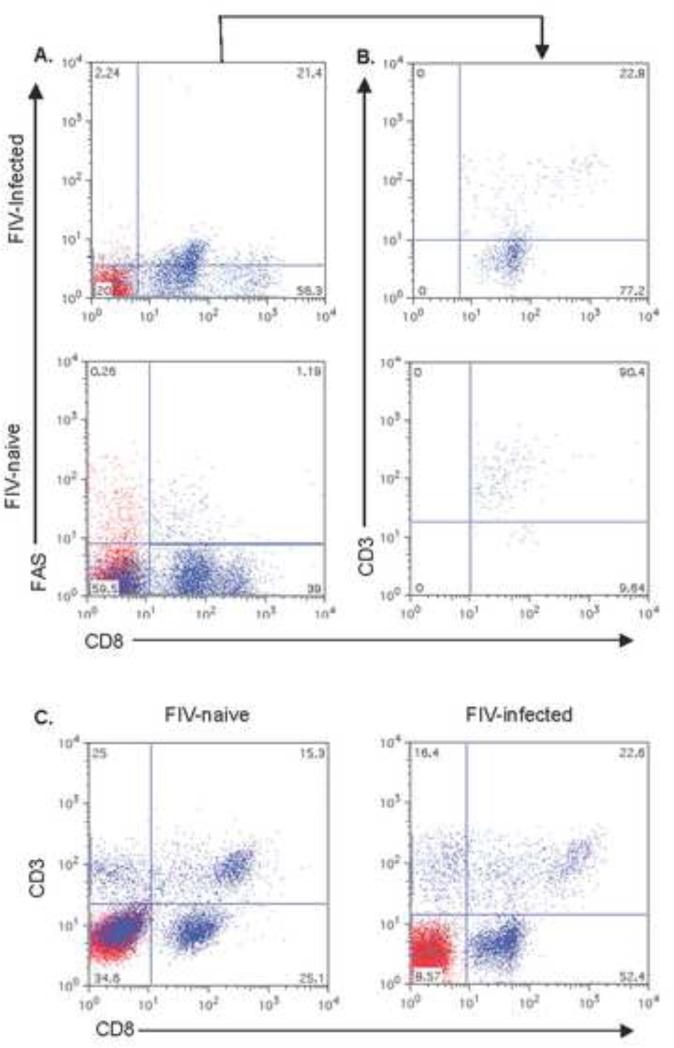

In addition to having lower CD8 expression, surface CD3ε expression was markedly decreased on CD8lo+FAS+ cells compared to the CD8lo+FAS+ cells of the FIV-naïve control cats. In comparison, an increase in CD3ε expression was seen on global CD8+ T cells from the FIV-infected cats compared to the FIV-naïve control cats (Fig. 5).

Fig.5.

Scatterplots of surface CD3ε expression in CD8+FAS+ cells in the PBMC of cats chronically infected with FIVC36 versus PBMC of FIV-naïve cats. The percent CD8+FAS+ cells in PBMC are shown in (A) and the percent of CD8+FAS+ cells expressing CD3ε shown in histogram (B). Panel (C) displays global CD8+ T cells versus CD3ε from the PBMC of a FIV-naive cat (left panel) versus CD3ε from the PBMC of a FIV-infected cat (right panel). The histograms are from one cat and are representative of four cats examined for the FIV-naïve group and two cats examined for the FIV-infected group.

CD8lo+FAS+ cells to do not express CD56 in cats with chronic FIV infection

CD56 is expressed on human NK, iNKT cells, and NKT-like T cells (Khvedelidze et al., 2008; Peralbo et al., 2007; Zamai et al., 2012). CD56 expression was not found to be present on feline CD8lo+FAS+ cells (data not shown).

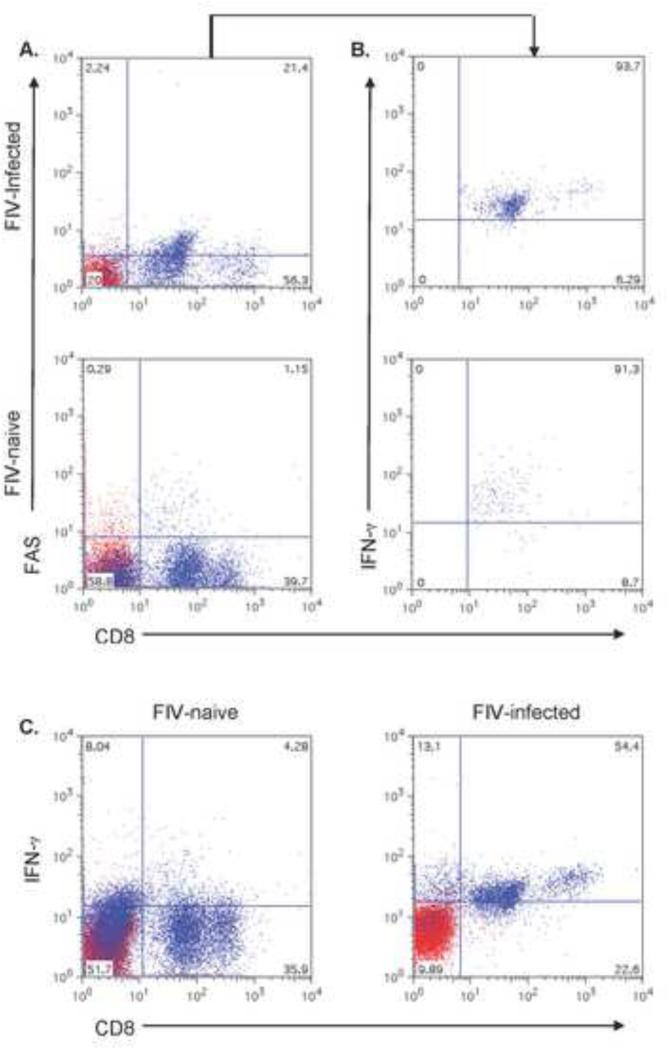

IFN-γ expression is similar in CD8+FAS+ cells from FIV-infected cats with chronic infection vs. FIV-naïve cats

IFN-γ production by CD8+ T cells in HIV–infected patients is variable depending on the stage of infection, methods used to assess IFN-γ production and molecules or cells used to stimulate the CD8+ T cells or the HIV-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) (Caruso et al., 1990; Cauda et al., 1987; Kostense et al., 2002; Shankar et al., 1999). We found that almost all the CD8lo+FAS+ cells from cats chronically infected with FIV expressed IFN-γ (~93%), and that the expression was similar to the CD8lo+FAS+ cells of FIV-naïve cats (91%). However, if one looked at the global CD8+ T cells, IFN-γ expression was increased in FIV-infected cats compared to FIV-naïve cats (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Scatterplots of intracellular IFN-γ expression in CD8+FAS+ cells in the PBMC of cats chronically infected with FIVC36 versus PBMC of FIV-naïve cats. The percent CD8+FAS+ cells in PBMC are shown in (A) and the percent of CD8+FAS+ cells expressing IFN-γ are shown in histogram (B). A representative scatterplot from a FIV-infected cat is shown in the top panel and one from an FIV-naïve cat is shown in the bottom panel. Panel (C) displays global CD8+ T cells versus IFN-γ from the PBMC of a FIV-naive cat (left panel) versus IFN-γ from the PBMC of a FIV-infected cat (right panel). The histograms are from one cat and are representative of four cats examined for the FIV-naïve group and two cats examined for the FIV-infected group.

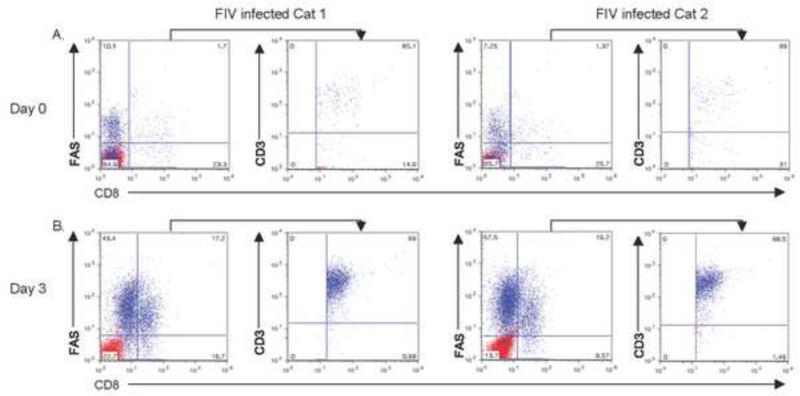

The percentage of CD8lo+FAS+ cells increased and CD3ε expression was restored on these cells after culture with Con A and IL-2

CD3ζ expression was shown to be down-regulated on CD8+ T cells from HIV-infected individuals early in infection, but expression was restored when exogenous IL-2 was added to cultured PBMCs from these individuals (Trimble and Lieberman, 1998). In this study, flow cytometric analysis of freshly isolated PBMCs showed that CD3ε expression on CD8lo+FAS+ cells from the cats acutely infected with FIV was decreased to a lesser extent than in those chronically infected with FIV. However, after PBMC were cultured with Con A and IL-2 for 3 days, expression of CD3ε on the CD8lo+FAS+ cells was rescued. Moreover, not only was CD3ε expression increased on the CD8lo+FAS+ cells, but CD8lo+FAS+ cells were also increased (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

PBMC from two FIV-infected cats of six examined with sub-acute infection were cultured in complete media with ConA and hIL-2 for 3 days. CD3ε expression of double positive CD8+Fas+ cells at day 0 (A), and 3 days post culture (B). Note increases of CD8+Fas+ cells with up-modulation with CD3ε expression in those cells compared to Day 0 cells.

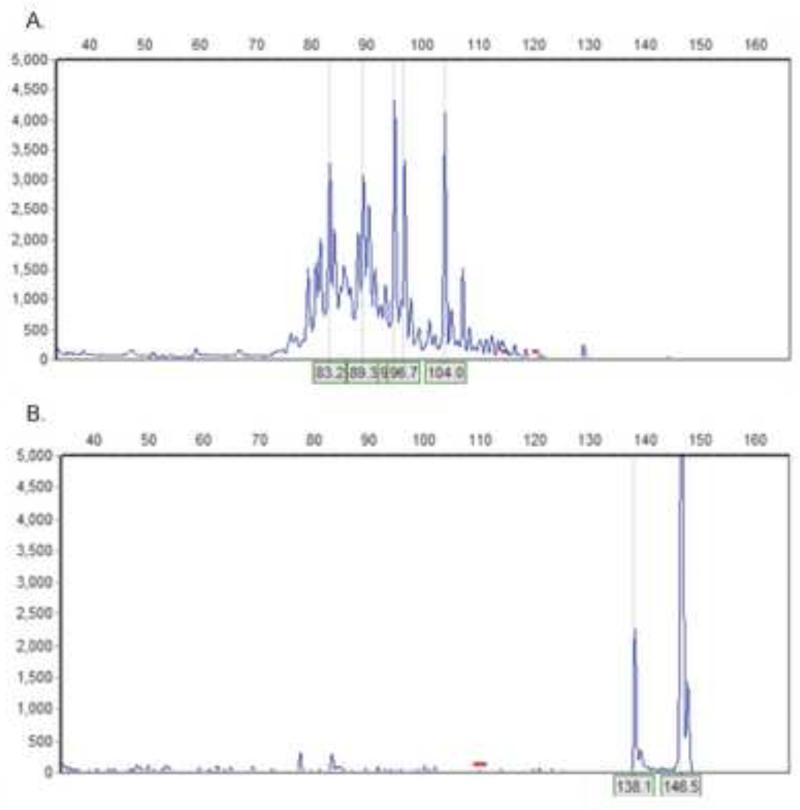

CD8lo+FAS+ cells from cats with chronic FIV infection are polyclonal T cells

Polyclonal proliferations of CD8+ cells have been documented in macaques with SIV infection and in humans with HIV infection (Chen et al., 1996; Zambello et al., 1993). To determine the clonality of the CD8lo+FAS+ cells, we looked for T-cell receptor (TCR) and immunoglobulin (Ig) gene rearrangements in the DNA from these cells. The results demonstrated that the cells were polyclonal T cells and that there were no contaminating B cells among the sorted cells (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Histograms demonstrating T-cell receptor (A) and immunoglobulin (B) gene rearrangements of CD8+FAS+ cells from a cat chronically infected with FIVC36. The plots are from one cat and represent two cats examined. In plot B, the positive control (rhodopsin) is represented by two sharp peaks. The lower peak (138.1) is an artifact of the capillary gel electrophoresis analysis.

CD8lo+FAS+ cells and LGLs arise similarly at about 4 weeks post FIV infection in cats

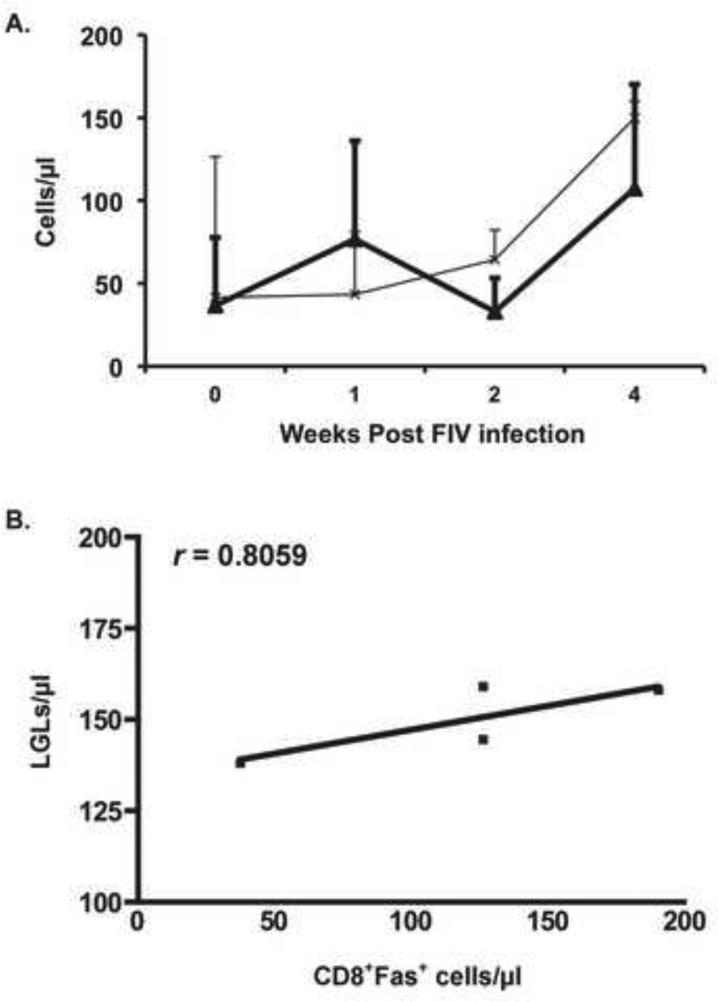

We next investigated whether or not the rise in LGLs and in CD8lo+FAS+ cells were correlated during acute FIV infection. We found that the rise in LGL and CD8lo+FAS+ cells correlated at 4 weeks PI, in agreement with our previous publication showing the rise of LGL at that time (r = 0.8059) (Sprague et al., 2010) (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

LGLs (Bold line) and CD8+Fas+ cells (thin line) arise similarly at 4 weeks PI in the blood of cats infected with FIVC-36. We also show good correlation (r = 0.8059) between the rise of LGLs and CD8+Fas+ cells at 4 weeks post infection (B). LGLs were analyzed from the blood smears of 6 cats, CD8+Fas+ cells from the PBMC of 4 of those cats.

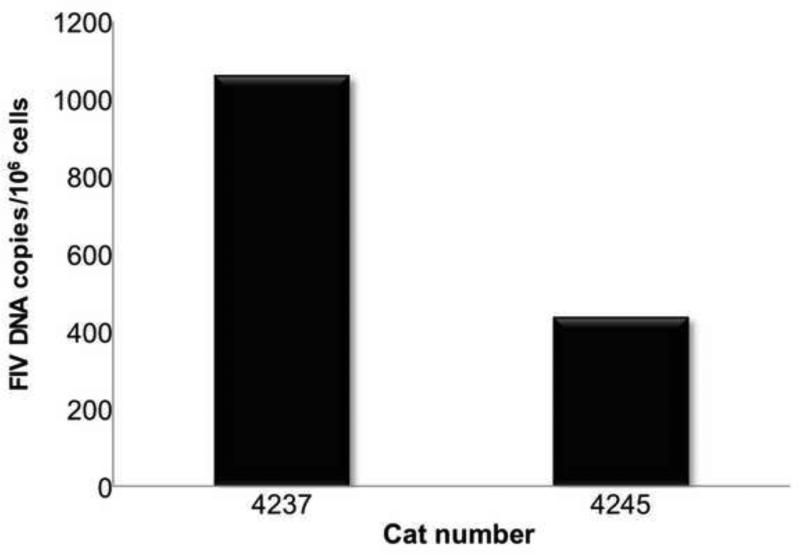

CD8lo+FAS+ cells from cats with chronic FIV infection are not considered infected with FIV

Infection of CD8+ T cells was demonstrated in vivo during SIV infection of macaques and during HIV infection of humans. Infection was also demonstrated during in vitro infection of PBMC with HIV (De Maria et al., 1991; Dean et al., 1996; Gulzar et al., 2008; Imlach et al., 2001). CD8lo+FAS+ T cells sorted to 91% - 94% purity (see Fig. 2) had proviral loads of 437 and 1,060 copies per 106 cells (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10.

FIV proviral loads are minimal in sorted CD8lo+FAS+ cells from two cats with chronic FIV infection.

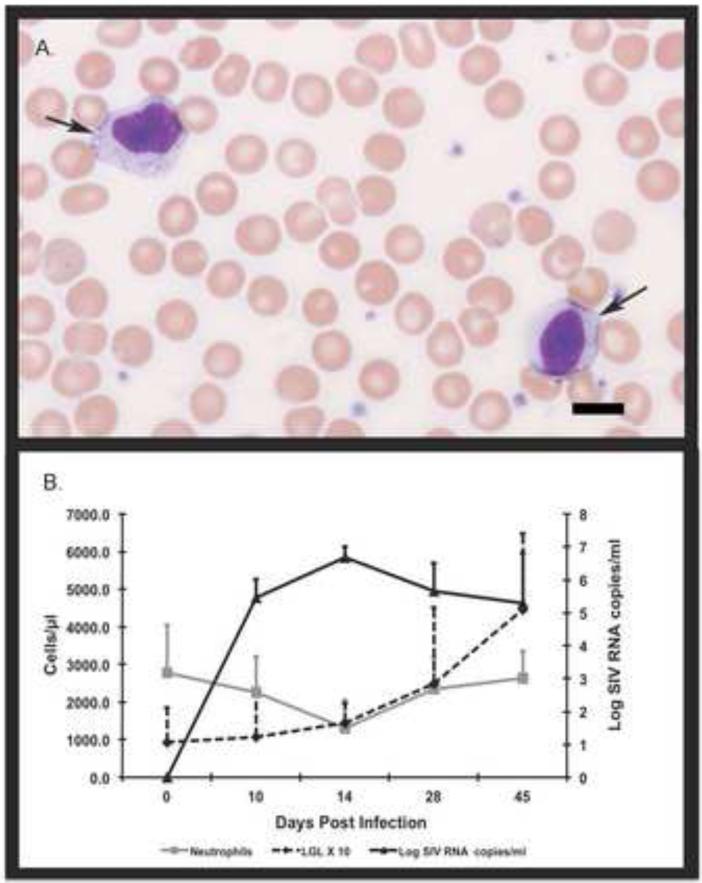

LGLs arise 2 weeks PI in macaques infected with virulent SIVmac

To demonstrate that LGLs are not specific only to FIV-infected cats but are a general feature of lentiviral infection, we examined blood smears from macaques with SIVmac239. We noted a similar rise in LGLs beginning 2 weeks PI associated with the peak of plasma viral loads and decrease in peripheral neutrophil counts (Fig. 11). The viral loads in the SIV-infected macaques were higher and peaked by two weeks PI compared to FIV-infected cats examined in this study and compared to HIV infection of humans, both of which typically have peak viral loads 3-4 weeks PI (McMichael et al., 2010; Sprague et al., 2010).

Fig. 11.

LGLs from macaques infected with virulent SIVmac237. The top panel (A) shows two LGLs (arrows) from the peripheral blood of one macaque. The bottom panel (B) shows the rise of LGL (dotted black line) versus the dip in neutrophil counts (gray line) by day 14 post infection versus the rise in SIV viral titers (solid black line) beginning approximately 10 days post infection. Bar indicates 10μm in length. The graph represents results from 6 SIV-infected macaques.

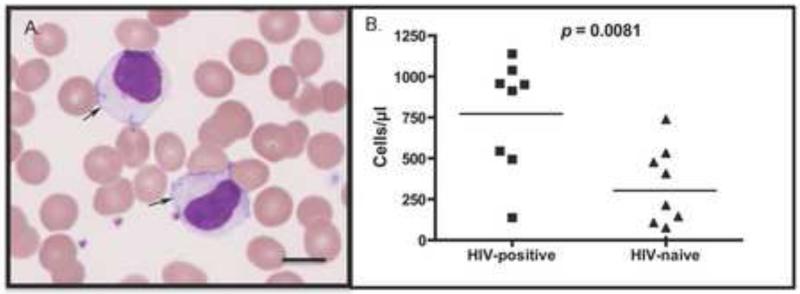

LGLs are increased in the blood of HIV-infected individuals

We evaluated blood smears from HIV-infected individuals to see if LGLs were present in higher numbers compared to HIV-naïve individuals (n=9/group). LGLs lymphocytosis was readily detected in HIV-infected individuals compared to the uninfected individuals (p = 0.0081), and the cells were morphologically similar to those of cats and macaques (Figure 12). We were unable to document a correlation with viral loads, CD4 counts or antiviral treatment in this analysis.

Fig. 12.

LGLs in the blood of HIV-positive individuals vs. HIV-naïve individuals. A photomicrograph of LGLs in the blood of one HIV-infected individual (A) and graphing of LGLs/μl in the blood of HIV-positive vs. HIV-naïve individuals showing a statistical difference between the groups (B). Bar indicates 10μm in length. A total of 8 HIV-positive and 9 HIV-naïve blood smears were examined.

Discussion

We identified the phenotype of LGLs that arise during acute FIV infection and persist in chronic infection as CD8lo+FAS+ T cells. CD8lo+FAS+ T cells from chronically infected cats had decreased CD3ε and similar expression of IFN-γ compared to the same cells from the FIV-naïve counterparts. These cells did not express CD56, were found to be polyclonal T cells, and did not represent a significant source of virus in FIV–infected cats. In addition, we identified LGLs in blood smears of macaques with SIV infection and in humans with HIV infection, demonstrating this cell phenotype is not unique to FIV.

Though CD8+CD57+ phenotype is consistent with the cell surface expression of LGL lymphocytosis typically associated with leukemia and common variable immunodeficiencies, in this study we associate the LGL phenotype as CD8lo+FAS+. In fact, when examining the cytocentrifuged preparation of the sorted CD8lo+FAS+ cells approximately 91% of the were LGLs, whereas none of cytocentrifuged preparation of sorted CD8+CD57+ cells were LGLs. A report of benign LGL lymphocytosis in HIV-infected individuals found approximately 25% of the CD8+ cells expressed CD57 and made an assumption that the LGLs were CD8+CD57+; however, this study did not utilize cell sorting technology or examine FAS expression as performed in this analysis (Burks and Loughran, 2005; Holm et al., 2006; Smith et al., 2000). CD8+FAS+ cells have been infrequently described in the HIV literature. CD8+ T cells from HIV infected individuals are highly sensitive to spontaneous and FAS-induced apoptosis in vitro (Estaquier et al., 1995; Katsikis et al., 1995). In addition, more recently it was shown that most of the antigen-specific CD8+ T cells in children and infants with HIV infection were FAS+ and that the phenotype of viral suppressive cells in HIV-infected individuals expressed both CD8 and FAS (Killian et al., 2011; Slyker et al., 2011). We, therefore, believe that the LGL/CD8lo+FAS+ phenotype we identified in FIV-infected cats may represent a viral suppressive phenotype. In addition, our finding that CD8+FAS+ cells are polyclonal in FIV-infected cats suggests that these cells are primed to target a diverse MHC repertoire necessary to combat viral infections (Sircar et al., 2010; Zambello et al., 1993).

CD8lo+FAS+ cells from both FIV-infected cats and FIV-naïve cats express IFN-γ suggesting that this population of cells is primed with antiviral functions. CD8+ T cells from FIV infected cats had markedly increased intracellular IFN-γ expression compared to FIV-naive cats; this activity was localized to the expanded CD8lo+FAS+ population. Bahri et al. reported that CD8+ T cell IFN-γ secretion and cell-cell contact were at play during suppression of CD4+ T cell proliferation in naïve mice, in vitro and in vivo, and in HIV-naïve humans, in vitro. These CD8+ T cells had high CD38 expression, an activation marker (Bahri et al., 2012; Patton et al., 2011). Interestingly, CD8+FAS+ cells were identified in HIV infection as expressing CD38, an activation marker (Jiang et al., 1997). Together, this information suggests that these CD8 cells expressing FAS are involved in suppression of the immune system, likely during homeostasis and during lentiviral infections.

Decreased expression of CD8, as seen in the CD8lo+FAS+ cells of our cats, was recently reported as increased in FIV-infected cats. This study did not evaluate FAS expression, but demonstrated a CD4/CD8lo ratio was a more sensitive indicator of FIV infection than CD4/CD8 ratio (Litster et al., 2014). In mice, a CD8lo phenotype defined a peripheral regulatory CD8+ T cell population that arose after repeated antigen encounter (Maile et al., 2006). It is possible that CD8lo+FAS+ cells in cats infected with FIV arise to suppress CD4+ T cells and in doing so, suppress virally infected cells.

Few studies have evaluated IFN-γ expression in PBMC from HIV-individuals via intracellular cytokine analysis. One study demonstrated an increase in IFN-γ expression in the global CD8+ T cells of HIV-infected individuals that did not correlate with clinical status or plasma viral load (Westby et al., 1998). Several studies have evaluated IFN-γ production following anti-CD3, CD4 or HIV peptide stimulation. In one study, less than 25% of the tetramer-specific CTL expressed IFN-γ in chronically infected HIV+ individuals (Shankar et al., 1999) Sorted HIV-1–specific CD8+ T cells that secreted only IFN-γ TNF-α after stimulation with viral antigens weakly correlated with cytotoxic activity, but CD8+ T cells that secreted both IFN-γ and TNF-α were more strongly associated with cytotoxicity—i.e., only a subset of IFN-γ expressing CD8+ T cells was shown to mediate HIV-specific cytotoxicity (Lichterfeld et al., 2004). Evaluation of TNF-α expression in FIV associated LGLs would thus be relevant for future study.

We noted increased CD3 expression on CD8+ T cells from FIV-positive versus FIV-naïve cats in the global CD8+ T cell population. However, CD3 expression was markedly down-modulated on the CD8lo+FAS+ subset of CD8+ T cells from FIV-positive vs. FIV-naive cats. CD3ε expression was shown to be decreased on a subset of CD8α+β− cells of cats infected with FIV, and CD3zeta (CD3ζ another transmembrane protein of the CD3 subunit, was decreased on CD8+ T cells during early HIV, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and cytomegalovirus (CMV) infections in humans (Nishimura et al., 2004; Ono et al., 1995; Trimble et al., 2000; Trimble and Lieberman, 1998). In a study by Trimble et al., CD3 down-modulation was accompanied by down-modulation of the principal co-stimulatory molecule, CD28, during CMV and EBV infections. This finding suggested that CD3 down-modulation was associated with immune response damping to prevent excess immune activation. In these infections, and in HIV-1 infection, CD8+ T cells up-modulated CD3 after a brief culture with IL-2, and this CD3 up-modulation was associated with the restoration of cytotoxicity (Trimble et al., 2000; Trimble and Lieberman, 1998). We demonstrated here that: (1) CD3 is up-modulated on CD8lo+FAS+ cells when PBMCs were cultured with Con A and IL-2, and (2) CD8lo+FAS+ cell percentages were increased following culture with Con A and IL-2. It is therefore feasible that cell phenotype restoration following immunostimulation might be translatable to methodologies that restore CD8+ T cell function in vivo. We should also note that not all CD8+ T cells were positive for CD3 in the global CD8 T cells from the FIV-naïve cats, which may indicate that the surface CD3ε Ab we used did not detect lower expressing CD3 on some CD8+ cells or it could indicate a subset of NK cells. These CD3−CD8+ are usually CD56+ cells in humans (Korosec et al., 2007; Wajchman et al., 2004), however, we did not appreciate significant expression of CD56 on CD8+ cells or our CD8lo+FAS+ cells in the cats of this study. Further studies evaluating additional NK cell markers and intracellular CD3 are needed to evaluate these hypotheses.

The overall results from this study indicate the importance of visual examination of cell subsets to correlate traditional microscopic morphology with flow cytometric characterization. Further, this work points to the role of a non-specific effector cell with viral suppressive qualities that expresses CD8 and bridges innate and adaptive immunity during lentivirus infection. As it only represents a small fraction of the total CD8+ T cell population, subtle changes detected here, such a CD3ε down-regulation on this minor subset of CD8 cells would not be easily detected via evaluations of the global CD8 T cell population. It is likely that CD3 expression is lost upon repeated antigen exposure and that the activated viral-specific cells in pathogenic lentiviral infections, cannot be re-activated due to the diminution of IL-2 expressing helper CD4+ T cells which arises during lentivirus infection, thus leading to immune compromise in latter stages of infection (Trimble et al., 2000).

Given that we were able to identify LGL lymphocytosis in a relatively small cohort of HIV-infected individuals, it is surprising that LGLs have only rarely been described in HIV disease. We speculate that machine-based hematology instrumentation reduces microscopy of blood smears, which may have contributed to a lack of recognition of this phenomenon, which may also be the case for the lack of identity of LGL lymphocytoses during SIV infection of macaques. Our important and exciting finding suggests new avenues for investigations of CD8+ T cell function during HIV infection that has so far proved elusive. Our studies further suggest that FIV is a very useful model to study this phenomenon, and this system may be used to explore potential methodologies to rescue immune function related to LGL/CD8lo+FAS+ cell activation.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Kathy Kioussopoulos and Tim Ferguson at Poudre Valley Hospital for the acquisition of human blood smears. This work was funded by grant HL092791 from the National Institutes of Health. The author's have no conflicting financial interests.

List of abbreviations

- LGLs

- ConA

- IL-2

- FIV

- HIV

- SIV

- EDTA

- NK

- PBMC

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alekshun TJ, Sokol L. Diseases of large granular lymphocytes. Cancer control : journal of the Moffitt Cancer Center. 2007;14:141–150. doi: 10.1177/107327480701400207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahri R, Bollinger A, Bollinger T, Orinska Z, Bulfone-Paus S. Ectonucleotidase CD38 demarcates regulatory, memory-like CD8+ T cells with IFN-gamma-mediated suppressor activities. PloS one. 2012;7:e45234. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumert E, Wolff-Vorbeck G, Schlesier M, Peter HH. Immunophenotypical alterations in a subset of patients with common variable immunodeficiency (CVID). Clinical and experimental immunology. 1992;90:25–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1992.tb05826.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boveri E, Riboni R, Antico P, Malacrida A, Pastorini A. CD3+ T large granular lymphocyte leukaemia in a HIV+, HCV+, HBV+ patient. Virchows Archiv : an international journal of pathology. 2009;454:349–351. doi: 10.1007/s00428-008-0716-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckheit RW, 3rd, Salgado M, Silciano RF, Blankson JN. Inhibitory potential of subpopulations of CD8+ T cells in HIV-1-infected elite suppressors. Journal of virology. 2012;86:13679–13688. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02439-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burks EJ, Loughran TP., Jr. Perspectives in the treatment of LGL leukemia. Leukemia research. 2005;29:123–125. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caruso A, Gonzales R, Stellini R, Scalzini A, Peroni L, Turano A. Interferon-gamma marks activated T lymphocytes in AIDS patients. AIDS research and human retroviruses. 1990;6:899–904. doi: 10.1089/aid.1990.6.899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauda R, Tyring SK, Tamburrini E, Ventura G, Tambarello M, Ortona L. Diminished interferon gamma production may be the earliest indicator of infection with the human immunodeficiency virus. Viral immunology. 1987;1:247–258. doi: 10.1089/vim.1987.1.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan WC, Link S, Mawle A, Check I, Brynes RK, Winton EF. Heterogeneity of large granular lymphocyte proliferations: delineation of two major subtypes. Blood. 1986;68:1142–1153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ZW, Shen L, Regan JD, Kou Z, Ghim SH, Letvin NL. The T cell receptor gene usage by simian immunodeficiency virus gag-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes in rhesus monkeys. J Immunol. 1996;156:1469–1475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Maria A, Pantaleo G, Schnittman SM, Greenhouse JJ, Baseler M, Orenstein JM, Fauci AS. Infection of CD8+ T lymphocytes with HIV. Requirement for interaction with infected CD4+ cells and induction of infectious virus from chronically infected CD8+ cells. J Immunol. 1991;146:2220–2226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean GA, Reubel GH, Pedersen NC. Simian immunodeficiency virus infection of CD8+ lymphocytes in vivo. Journal of virology. 1996;70:5646–5650. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.8.5646-5650.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estaquier J, Idziorek T, Zou W, Emilie D, Farber CM, Bourez JM, Ameisen JC. T helper type 1/T helper type 2 cytokines and T cell death: preventive effect of interleukin 12 on activation-induced and CD95 (FAS/APO-1)-mediated apoptosis of CD4+ T cells from human immunodeficiency virus-infected persons. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1995;182:1759–1767. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.6.1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn JN, Cannon CA, Sloan D, Neil JC, Jarrett O. Suppression of feline immunodeficiency virus replication in vitro by a soluble factor secreted by CD8+ T lymphocytes. Immunology. 1999;96:220–229. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1999.00690.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulzar N, Balasubramanian S, Harris G, Sanchez-Dardon J, Copeland KF. Infection of CD8+CD45RO+ memory T-cells by HIV-1 and their proliferative response. The open AIDS journal. 2008;2:43–57. doi: 10.2174/1874613600802010043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm AM, Tjonnfjord G, Yndestad A, Beiske K, Muller F, Aukrust P, Froland SS. Polyclonal expansion of large granular lymphocytes in common variable immunodeficiency - association with neutropenia. Clinical and experimental immunology. 2006;144:418–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03086.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imlach S, McBreen S, Shirafuji T, Leen C, Bell JE, Simmonds P. Activated peripheral CD8 lymphocytes express CD4 in vivo and are targets for infection by human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Journal of virology. 2001;75:11555–11564. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.23.11555-11564.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeng CR, English RV, Childers T, Tompkins MB, Tompkins WA. Evidence for CD8+ antiviral activity in cats infected with feline immunodeficiency virus. Journal of virology. 1996;70:2474–2480. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.4.2474-2480.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang JD, Schlesinger M, Sacks H, Mildvan D, Roboz JP, Bekesi JG. Concentrations of soluble CD95 and CD8 antigens in the plasma and levels of CD8+CD95+, CD8+CD38+, and CD4+CD95+ T cells are markers for HIV-1 infection and clinical status. Journal of clinical immunology. 1997;17:185–192. doi: 10.1023/a:1027386701052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannagi M, Chalifoux LV, Lord CI, Letvin NL. Suppression of simian immunodeficiency virus replication in vitro by CD8+ lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1988;140:2237–2242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsikis PD, Wunderlich ES, Smith CA, Herzenberg LA. Fas antigen stimulation induces marked apoptosis of T lymphocytes in human immunodeficiency virus-infected individuals. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1995;181:2029–2036. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.6.2029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khvedelidze M, Chkhartishvili N, Abashidze L, Dzigua L, Tsertsvadze T. Expansion of CD3/CD16/CD56 positive NKT cells in HIV/AIDS: the pilot study. Georgian medical news. 2008:78–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killian MS, Johnson C, Teque F, Fujimura S, Levy JA. Natural suppression of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication is mediated by transitional memory CD8+ T cells. Journal of virology. 2011;85:1696–1705. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01120-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korosec P, Osolnik K, Kern I, Silar M, Mohorcic K, Kosnik M. Expansion of pulmonary CD8+CD56+ natural killer T-cells in hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Chest. 2007;132:1291–1297. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-0128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostense S, Vandenberghe K, Joling J, Van Baarle D, Nanlohy N, Manting E, Miedema F. Persistent numbers of tetramer+ CD8(+) T cells, but loss of interferon-gamma+ HIV-specific T cells during progression to AIDS. Blood. 2002;99:2505–2511. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.7.2505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichterfeld M, Yu XG, Waring MT, Mui SK, Johnston MN, Cohen D, Addo MM, Zaunders J, Alter G, Pae E, Strick D, Allen TM, Rosenberg ES, Walker BD, Altfeld M. HIV-1-specific cytotoxicity is preferentially mediated by a subset of CD8(+) T cells producing both interferon-gamma and tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Blood. 2004;104:487–494. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litster A, Lin JM, Nichols J, Weng HY. Diagnostic utility of CD4%:CD8 low% T-lymphocyte ratio to differentiate feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV)-infected from FIV-vaccinated cats. Veterinary microbiology. 2014;170:197–205. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2014.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez M, Soriano V, Peris-Pertusa A, Rallon N, Restrepo C, Benito JM. Elite controllers display higher activation on central memory CD8 T cells than HIV patients successfully on HAART. AIDS research and human retroviruses. 2011;27:157–165. doi: 10.1089/aid.2010.0107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loughran TP., Jr. Clonal diseases of large granular lymphocytes. Blood. 1993;82:1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loughran TP, Jr., Starkebaum G. Large granular lymphocyte leukemia. Report of 38 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 1987;66:397–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maile R, Pop SM, Tisch R, Collins EJ, Cairns BA, Frelinger JA. Low-avidity CD8lo T cells induced by incomplete antigen stimulation in vivo regulate naive higher avidity CD8hi T cell responses to the same antigen. European journal of immunology. 2006;36:397–410. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMichael AJ, Borrow P, Tomaras GD, Goonetilleke N, Haynes BF. The immune response during acute HIV-1 infection: clues for vaccine development. Nature reviews. Immunology. 2010;10:11–23. doi: 10.1038/nri2674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza D, Johnson SA, Peterson BA, Natarajan V, Salgado M, Dewar RL, Burbelo PD, Doria-Rose NA, Graf EH, Greenwald JH, Hodge JN, Thompson WL, Cogliano NA, Chairez CL, Rehm CA, Jones S, Hallahan CW, Kovacs JA, Sereti I, Sued O, Peel SA, O'Connell RJ, O'Doherty U, Chun TW, Connors M, Migueles SA. Comprehensive analysis of unique cases with extraordinary control over HIV replication. Blood. 2012;119:4645–4655. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-10-381996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore PF, Rodriguez-Bertos A, Kass PH. Feline gastrointestinal lymphoma: mucosal architecture, immunophenotype, and molecular clonality. Veterinary pathology. 2012;49:658–668. doi: 10.1177/0300985811404712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ndhlovu ZM, Proudfoot J, Cesa K, Alvino DM, McMullen A, Vine S, Stampouloglou E, Piechocka-Trocha A, Walker BD, Pereyra F. Elite controllers with low to absent effector CD8+ T cell responses maintain highly functional, broadly directed central memory responses. Journal of virology. 2012;86:6959–6969. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00531-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura Y, Shimojima M, Sato E, Izumiya Y, Tohya Y, Mikami T, Miyazawa T. Downmodulation of CD3epsilon expression in CD8alpha+beta− T cells of feline immunodeficiency virus-infected cats. The Journal of general virology. 2004;85:2585–2589. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80102-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono S, Ohno H, Saito T. Rapid turnover of the CD3 zeta chain independent of the TCR-CD3 complex in normal T cells. Immunity. 1995;2:639–644. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90008-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton DT, Wilson MD, Rowan WC, Soond DR, Okkenhaug K. The PI3K p110delta regulates expression of CD38 on regulatory T cells. PloS one. 2011;6:e17359. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen NC, Leutenegger CM, Woo J, Higgins J. Virulence differences between two field isolates of feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV-APetaluma and FIV-CPGammar) in young adult specific pathogen free cats. Veterinary immunology and immunopathology. 2001;79:53–67. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2427(01)00252-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peralbo E, Alonso C, Solana R. Invariant NKT and NKT-like lymphocytes: two different T cell subsets that are differentially affected by ageing. Experimental gerontology. 2007;42:703–708. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulik M, Lionnet F, Genet P, Petitdidier C, Jary L, Fourcade C. CD3+ CD8+ CD56− clonal large granular lymphocyte leukaemia and HIV infection. British journal of haematology. 1997;98:444–445. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1997.1913009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankar P, Xu Z, Lieberman J. Viral-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes lyse human immunodeficiency virus-infected primary T lymphocytes by the granule exocytosis pathway. Blood. 1999;94:3084–3093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoes RD, Howard KE, Dean GA. In vivo assessment of natural killer cell responses during chronic feline immunodeficiency virus infection. PloS one. 2012;7:e37606. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sircar P, Furr KL, Dorosh LA, Letvin NL. Clonal repertoires of virus-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes are shared in mucosal and systemic compartments during chronic simian immunodeficiency virus infection in rhesus monkeys. J Immunol. 2010;185:2191–2199. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slyker JA, John-Stewart GC, Dong T, Lohman-Payne B, Reilly M, Atzberger A, Taylor S, Maleche-Obimbo E, Mbori-Ngacha D, Rowland-Jones SL. Phenotypic characterization of HIV-specific CD8+ T cells during early and chronic infant HIV-1 infection. PloS one. 2011;6:e20375. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PR, Cavenagh JD, Milne T, Howe D, Wilkes SJ, Sinnott P, Forster GE, Helbert M. Benign monoclonal expansion of CD8+ lymphocytes in HIV infection. Journal of clinical pathology. 2000;53:177–181. doi: 10.1136/jcp.53.3.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprague WS, TerWee JA, VandeWoude S. Temporal association of large granular lymphocytosis, neutropenia, proviral load, and FasL mRNA in cats with acute feline immunodeficiency virus infection. Veterinary immunology and immunopathology. 2010;134:115–121. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2009.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stump DS. Host Cell Antigen and T-lymphocytes Subset Contribution to Simian Immunodeficiency Virus Pathogenicity. Colorado State University; Fort Collins, CO: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Terwee JA, Carlson JK, Sprague WS, Sondgeroth KS, Shropshire SB, Troyer JL, VandeWoude S. Prevention of immunodeficiency virus induced CD4+ T-cell depletion by prior infection with a non-pathogenic virus. Virology. 2008;377:63–70. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.03.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trimble LA, Kam LW, Friedman RS, Xu Z, Lieberman J. CD3zeta and CD28 down-modulation on CD8 T cells during viral infection. Blood. 2000;96:1021–1029. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trimble LA, Lieberman J. Circulating CD8 T lymphocytes in human immunodeficiency virus-infected individuals have impaired function and downmodulate CD3 zeta, the signaling chain of the T-cell receptor complex. Blood. 1998;91:585–594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wajchman HJ, Pierce CW, Varma VA, Issa MM, Petros J, Dombrowski KE. Ex vivo expansion of CD8+CD56+ and CD8+CD56− natural killer T cells specific for MUC1 mucin. Cancer research. 2004;64:1171–1180. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-3254-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker CM, Moody DJ, Stites DP, Levy JA. CD8+ lymphocytes can control HIV infection in vitro by suppressing virus replication. Science. 1986;234:1563–1566. doi: 10.1126/science.2431484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westby M, Marriott JB, Guckian M, Cookson S, Hay P, Dalgleish AG. Abnormal intracellular IL-2 and interferon-gamma (IFN-gamma) production as HIV-1-assocated markers of immune dysfunction. Clinical and experimental immunology. 1998;111:257–263. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00505.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamai L, Del Zotto G, Buccella F, Galeotti L, Canonico B, Luchetti F, Papa S. Cytotoxic functions and susceptibility to apoptosis of human CD56(bright) NK cells differentiated in vitro from CD34(+) hematopoietic progenitors. Cytometry. Part A : the journal of the International Society for Analytical Cytology. 2012;81:294–302. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.22025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zambello R, Trentin L, Agostini C, Francia di Celle P, Francavilla E, Barelli A, Cerutti A, Siviero F, Foa R, Semenzato G. Persistent polyclonal lymphocytosis in human immunodeficiency virus-1-infected patients. Blood. 1993;81:3015–3021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]